Storage and File Structure Course outlines Physical Storage

- Slides: 40

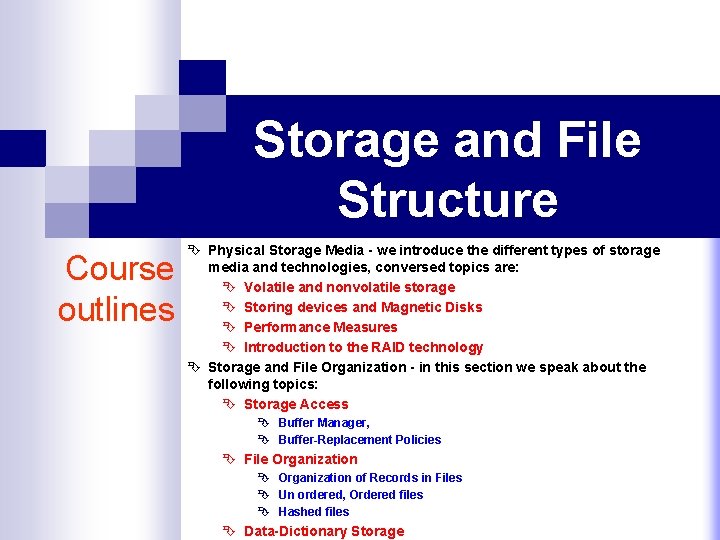

Storage and File Structure Course outlines Ê Physical Storage Media - we introduce the different types of storage media and technologies, conversed topics are: Ê Volatile and nonvolatile storage Ê Storing devices and Magnetic Disks Ê Performance Measures Ê Introduction to the RAID technology Ê Storage and File Organization - in this section we speak about the following topics: Ê Storage Access Ê Buffer Manager, Ê Buffer-Replacement Policies Ê File Organization Ê Organization of Records in Files Ê Un ordered, Ordered files Ê Hashed files Ê Data-Dictionary Storage

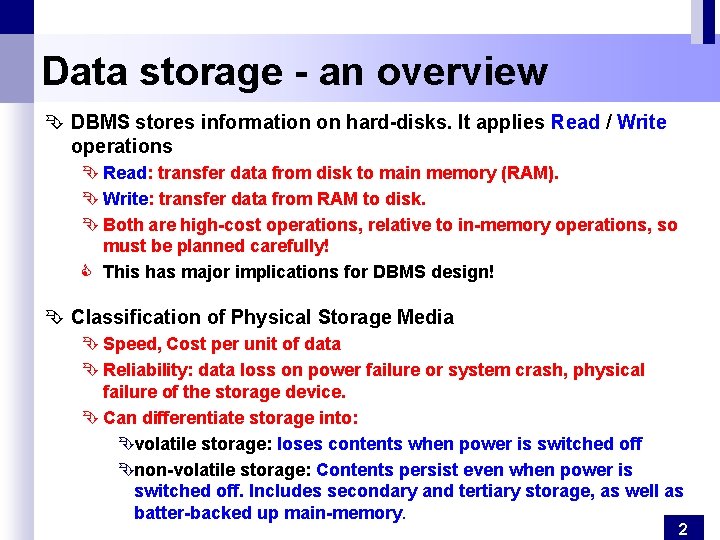

Data storage - an overview Ê DBMS stores information on hard-disks. It applies Read / Write operations Ê Read: transfer data from disk to main memory (RAM). Ê Write: transfer data from RAM to disk. Ê Both are high-cost operations, relative to in-memory operations, so must be planned carefully! C This has major implications for DBMS design! Ê Classification of Physical Storage Media Ê Speed, Cost per unit of data Ê Reliability: data loss on power failure or system crash, physical failure of the storage device. Ê Can differentiate storage into: Êvolatile storage: loses contents when power is switched off Ênon-volatile storage: Contents persist even when power is switched off. Includes secondary and tertiary storage, as well as batter-backed up main-memory. 2

Physical Storage Media- basic assumptions Why Not Store Everything in Main Memory? Ê Costs too much. $1000 will buy you either 128 MB of RAM or 7. 5 GB of disk today. Ê Main memory is volatile. We want data to be saved between runs. (Obviously!) Typical Storage Hierarchy Ê primary storage: Fastest media but volatile (cache, main memory RAM for currently used data). Ê secondary storage: non-volatile, moderately fast access time, also called on-line storage (e. g. flash memory, magnetic disks for the main database Ê tertiary storage: lowest level in hierarchy, non-volatile, slow access time. Also called off-line storage (e. g. magnetic tape for archiving data, optical storage 3

Physical Storage Media - overview Ê Cache, volatile: fastest and most costly form of storage. Ê Main memory, volatile, fast access: , generally too small (or too expensive) to store the entire database. Ê Flash memory, data survives power failure: also known as EEPROM (Electrically Erasable Programmable Read-Only Memory). Data can be written at a location only once, but location can be erased and written to again. Ê Magnetic disk, survives power failures and system crashes: data is stored on spinning disk, primary medium for the long-term storage of data, data must be moved from disk to main memory for access, and written back for storage Ê Optical storage, non-volatile, data is read optically from a spinning disk Ê CD-ROM (640 MB) and DVD (4. 7 to 17 GB) most popular forms Ê Reads and writes are slower than with magnetic disk 4

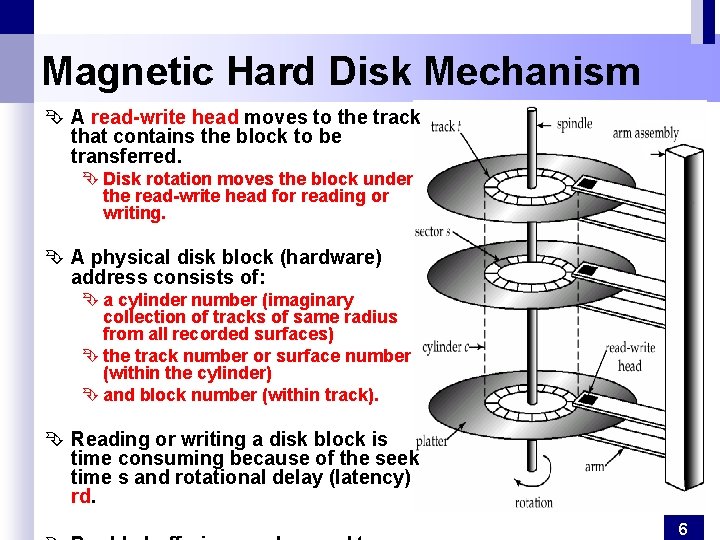

Disk Storage Devices Ê Preferred secondary storage device for high storage capacity and low cost. Ê Data stored as magnetized areas on magnetic disk surfaces. Ê A disk pack contains several magnetic disks connected to a rotating spindle. Ê Disks are divided into concentric circular tracks on each disk surface. Ê Track capacities vary typically from 4 to 50 Kbytes or more Ê A track is divided into smaller blocks or sectors Ê The division of a track into sectors is hard-coded on the disk surface and cannot be changed. Ê A track is divided into blocks. Ê The block size B is fixed for each system. Typical block sizes range from B=512 bytes to B=4096 bytes = 4 K bytes. Ê Whole blocks are transferred between disk and main memory for processing. Ê Main advantage of Disk over tapes: random access vs. sequential. Ê Data is stored and retrieved in units called disk blocks or pages. 5

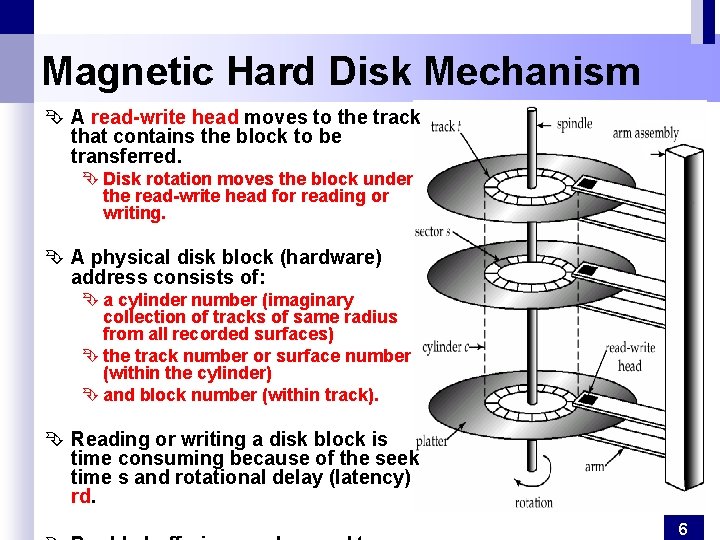

Magnetic Hard Disk Mechanism Ê A read-write head moves to the track that contains the block to be transferred. Ê Disk rotation moves the block under the read-write head for reading or writing. Ê A physical disk block (hardware) address consists of: Ê a cylinder number (imaginary collection of tracks of same radius from all recorded surfaces) Ê the track number or surface number (within the cylinder) Ê and block number (within track). Ê Reading or writing a disk block is time consuming because of the seek time s and rotational delay (latency) rd. 6

Other Disks Ê Optical Disks Compact disk-read only memory (CD-ROM) Ê Portable, high storage capacity (640 MB per disk) Ê High seek times or about 100 msec (optical read head is heavier and slower) Ê Higher latency and lower data-transfer rates compared to magnetic disks Digital Video Disk (DVD) rather than capacities, similar to CD-ROM Record once versions (CD-R and DVD-R) are becoming popular Ê data can only be written once, and cannot be erased. Ê high capacity and long lifetime; used for archival storage Ê Multi-write versions (CD-RW, DVD-RW and DVD-RAM) also available Ê Magnetic Tapes Ê Hold large volumes of data and provide high transfer rates Ê Currently the cheapest storage medium Ê Very slow access time in comparison to magnetic disks and optical disks limited to sequential access. Ê Used mainly for backup, for storage of infrequently used information, and as an off-line medium for transferring information from one system to another. Ê Tape jukeboxes used for very large capacity storage 7

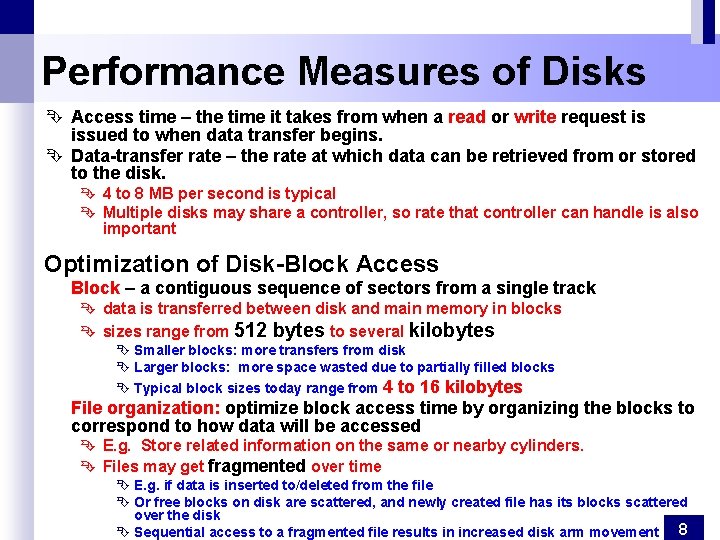

Performance Measures of Disks Ê Access time – the time it takes from when a read or write request is issued to when data transfer begins. Ê Data-transfer rate – the rate at which data can be retrieved from or stored to the disk. Ê 4 to 8 MB per second is typical Ê Multiple disks may share a controller, so rate that controller can handle is also important Optimization of Disk-Block Access Block – a contiguous sequence of sectors from a single track Ê data is transferred between disk and main memory in blocks Ê sizes range from 512 bytes to several kilobytes Ê Smaller blocks: more transfers from disk Ê Larger blocks: more space wasted due to partially filled blocks Ê Typical block sizes today range from 4 to 16 kilobytes File organization: optimize block access time by organizing the blocks to correspond to how data will be accessed Ê E. g. Store related information on the same or nearby cylinders. Ê Files may get fragmented over time Ê E. g. if data is inserted to/deleted from the file Ê Or free blocks on disk are scattered, and newly created file has its blocks scattered over the disk Ê Sequential access to a fragmented file results in increased disk arm movement 8

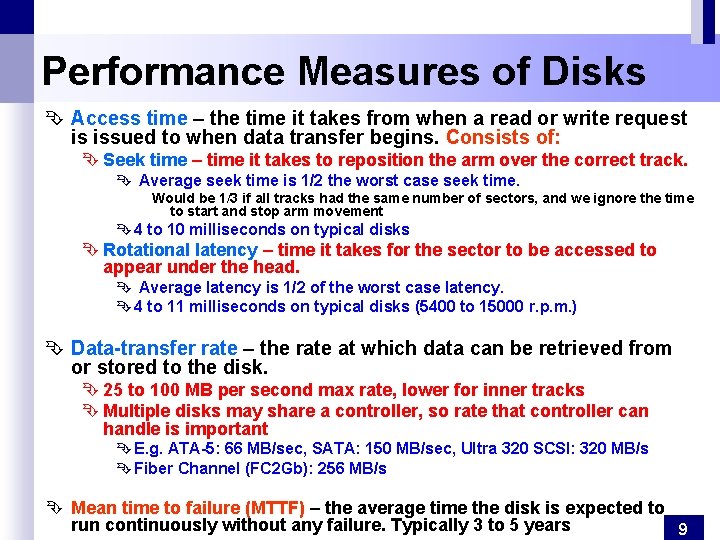

Performance Measures of Disks Ê Access time – the time it takes from when a read or write request is issued to when data transfer begins. Consists of: Ê Seek time – time it takes to reposition the arm over the correct track. Ê Average seek time is 1/2 the worst case seek time. Would be 1/3 if all tracks had the same number of sectors, and we ignore the time to start and stop arm movement Ê 4 to 10 milliseconds on typical disks Ê Rotational latency – time it takes for the sector to be accessed to appear under the head. Ê Average latency is 1/2 of the worst case latency. Ê 4 to 11 milliseconds on typical disks (5400 to 15000 r. p. m. ) Ê Data-transfer rate – the rate at which data can be retrieved from or stored to the disk. Ê 25 to 100 MB per second max rate, lower for inner tracks Ê Multiple disks may share a controller, so rate that controller can handle is important Ê E. g. ATA-5: 66 MB/sec, SATA: 150 MB/sec, Ultra 320 SCSI: 320 MB/s Ê Fiber Channel (FC 2 Gb): 256 MB/s Ê Mean time to failure (MTTF) – the average time the disk is expected to run continuously without any failure. Typically 3 to 5 years 9

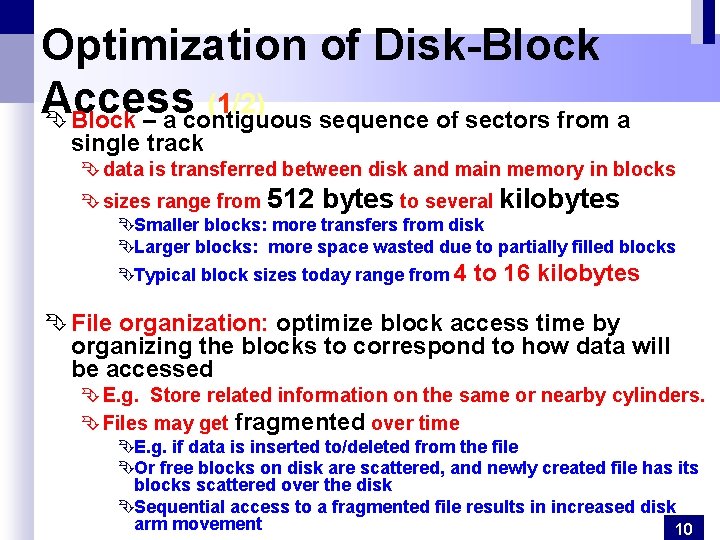

Optimization of Disk-Block Access (1/2) Ê Block – a contiguous sequence of sectors from a single track Ê data is transferred between disk and main memory in blocks Ê sizes range from 512 bytes to several kilobytes ÊSmaller blocks: more transfers from disk ÊLarger blocks: more space wasted due to partially filled blocks ÊTypical block sizes today range from 4 to 16 kilobytes Ê File organization: optimize block access time by organizing the blocks to correspond to how data will be accessed Ê E. g. Store related information on the same or nearby cylinders. Ê Files may get fragmented over time ÊE. g. if data is inserted to/deleted from the file ÊOr free blocks on disk are scattered, and newly created file has its blocks scattered over the disk ÊSequential access to a fragmented file results in increased disk arm movement 10

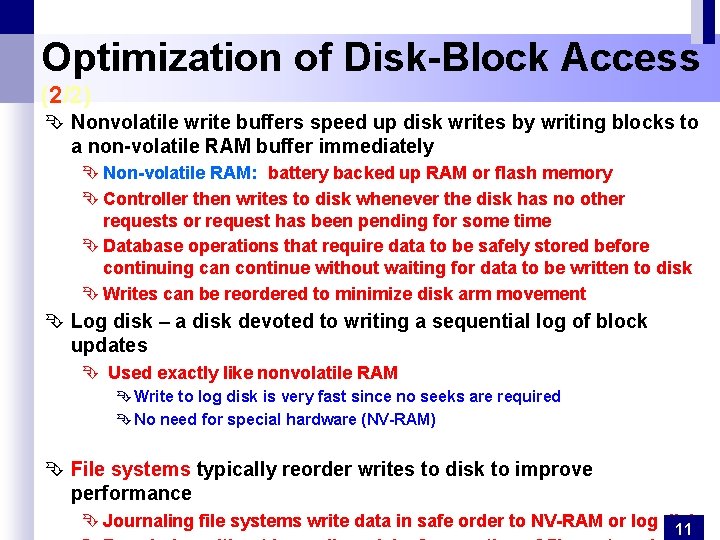

Optimization of Disk-Block Access (2/2) Ê Nonvolatile write buffers speed up disk writes by writing blocks to a non-volatile RAM buffer immediately Ê Non-volatile RAM: battery backed up RAM or flash memory Ê Controller then writes to disk whenever the disk has no other requests or request has been pending for some time Ê Database operations that require data to be safely stored before continuing can continue without waiting for data to be written to disk Ê Writes can be reordered to minimize disk arm movement Ê Log disk – a disk devoted to writing a sequential log of block updates Ê Used exactly like nonvolatile RAM Ê Write to log disk is very fast since no seeks are required Ê No need for special hardware (NV-RAM) Ê File systems typically reorder writes to disk to improve performance Ê Journaling file systems write data in safe order to NV-RAM or log disk 11

Using RAID Technology. Disk Access Ê A major advance in secondary storage technology is represented by the development of RAID, which originally stood for Redundant Arrays of Inexpensive/Independent Disks. Ê RAID (Redundant Arrays of Independent Disks) : A large array of small independent disks acting as a single higher-performance logical disk and providing Ê high capacity and high speed by using multiple disks in parallel, Ê high reliability by storing data redundantly, so that data can be recovered even if a disk fails 12

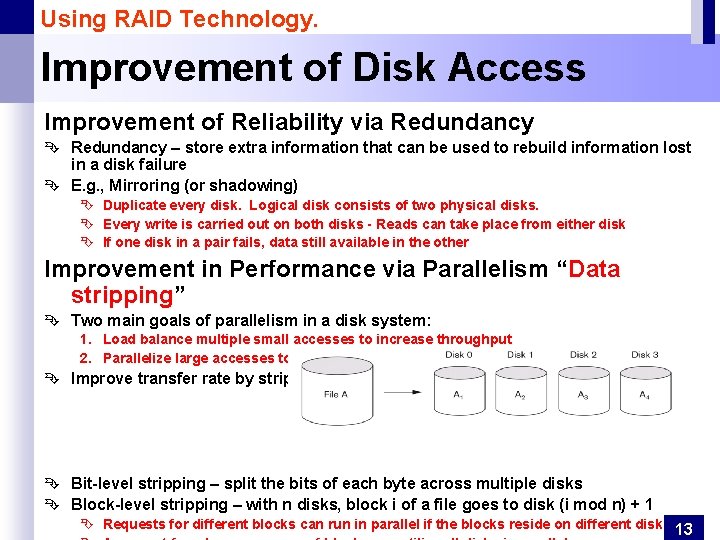

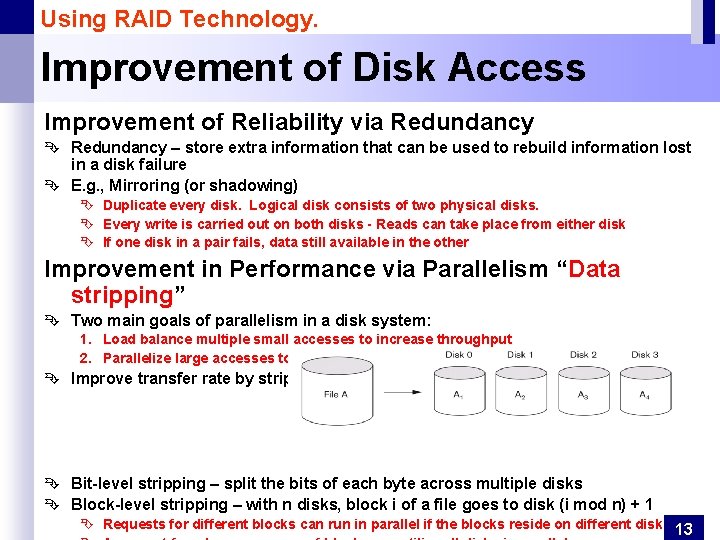

Using RAID Technology. Improvement of Disk Access Improvement of Reliability via Redundancy Ê Redundancy – store extra information that can be used to rebuild information lost in a disk failure Ê E. g. , Mirroring (or shadowing) Ê Duplicate every disk. Logical disk consists of two physical disks. Ê Every write is carried out on both disks - Reads can take place from either disk Ê If one disk in a pair fails, data still available in the other Improvement in Performance via Parallelism “Data stripping” Ê Two main goals of parallelism in a disk system: 1. Load balance multiple small accesses to increase throughput 2. Parallelize large accesses to reduce response time. Ê Improve transfer rate by striping data across multiple disks. Ê Bit-level stripping – split the bits of each byte across multiple disks Ê Block-level stripping – with n disks, block i of a file goes to disk (i mod n) + 1 Ê Requests for different blocks can run in parallel if the blocks reside on different disks 13

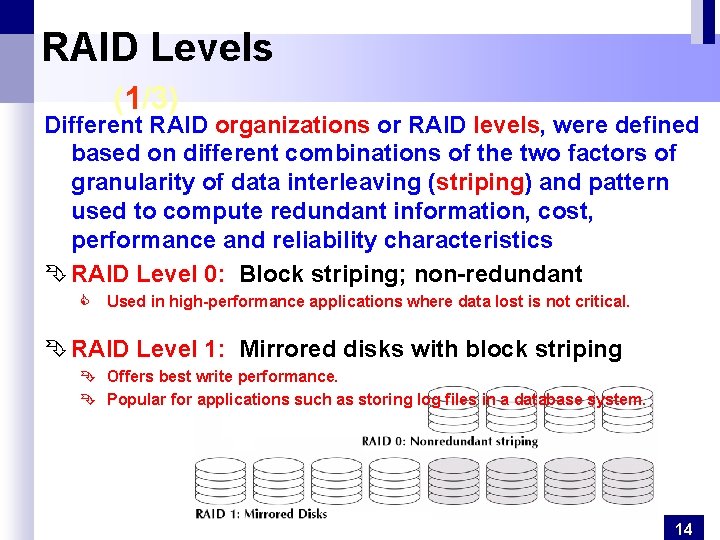

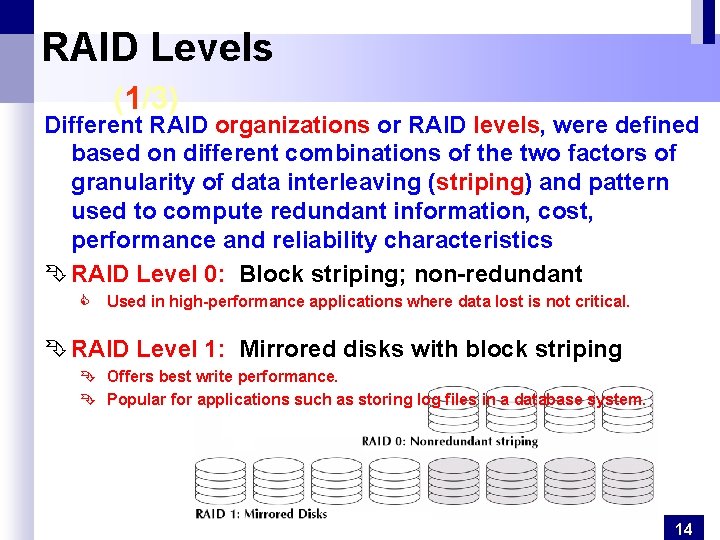

RAID Levels (1/3) Different RAID organizations or RAID levels, were defined based on different combinations of the two factors of granularity of data interleaving (striping) and pattern used to compute redundant information, cost, performance and reliability characteristics Ê RAID Level 0: Block striping; non-redundant C Used in high-performance applications where data lost is not critical. Ê RAID Level 1: Mirrored disks with block striping Ê Offers best write performance. Ê Popular for applications such as storing log files in a database system. 14

RAID Levels (2/3) Ê RAID Level 2: Memory-Style Error-Correcting-Codes (ECC) with bit striping. Ê RAID Level 3: Bit-Interleaved Parity - a single parity disk relying on the disk controller to figure out which disk has failed. 15

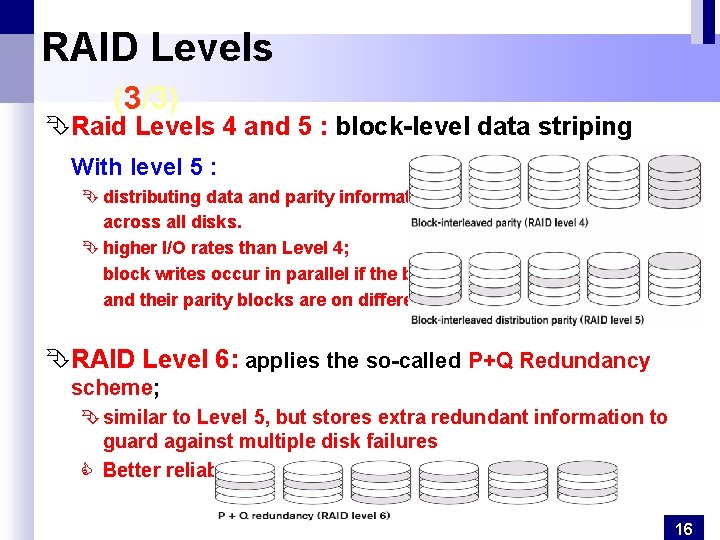

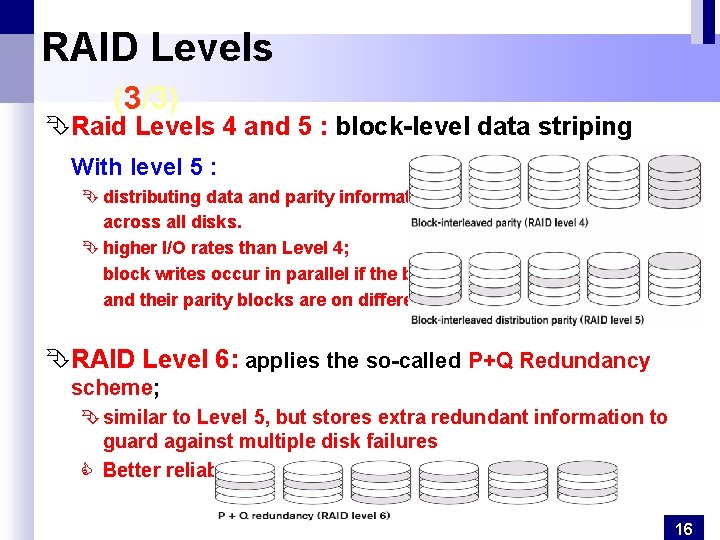

RAID Levels (3/3) ÊRaid Levels 4 and 5 : block-level data striping With level 5 : Ê distributing data and parity information across all disks. Ê higher I/O rates than Level 4; block writes occur in parallel if the blocks and their parity blocks are on different disks. ÊRAID Level 6: applies the so-called P+Q Redundancy scheme; Ê similar to Level 5, but stores extra redundant information to guard against multiple disk failures C Better reliability than Level 5 at a higher cost. 16

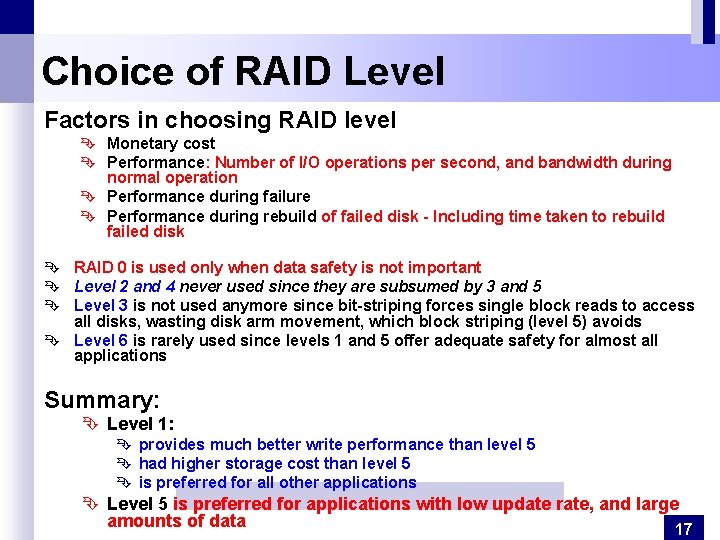

Choice of RAID Level Factors in choosing RAID level Ê Monetary cost Ê Performance: Number of I/O operations per second, and bandwidth during normal operation Ê Performance during failure Ê Performance during rebuild of failed disk - Including time taken to rebuild failed disk Ê RAID 0 is used only when data safety is not important Ê Level 2 and 4 never used since they are subsumed by 3 and 5 Ê Level 3 is not used anymore since bit-striping forces single block reads to access all disks, wasting disk arm movement, which block striping (level 5) avoids Ê Level 6 is rarely used since levels 1 and 5 offer adequate safety for almost all applications Summary: Ê Level 1: Ê provides much better write performance than level 5 Ê had higher storage cost than level 5 Ê is preferred for all other applications Ê Level 5 is preferred for applications with low update rate, and large amounts of data 17

Ê Storage Access Ê Buffer Manager, Ê Buffer-Replacement Policies Ê File Organization Ê Organization of Records in Files Ê Un ordered, Ordered files Ê Hashed files Ê Data-Dictionary Storage

Storage Access Ê A database file is partitioned into fixed-length storage units called blocks. Blocks are units of both storage allocation and data transfer. Ê Database system seeks to minimize the number of block transfers between the disk and memory. We can reduce the number of disk accesses by keeping as many blocks as possible in main memory. Ê Buffer – portion of main memory available to store copies of disk blocks. Ê Buffer manager – subsystem responsible for allocating buffer space in main memory. 19

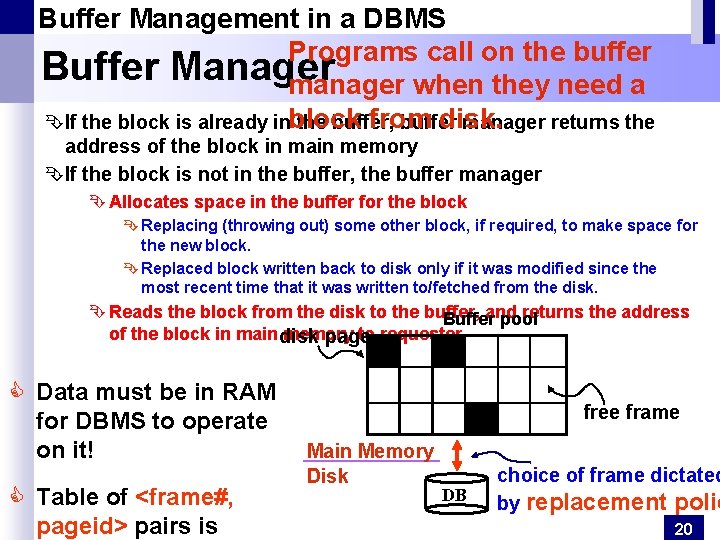

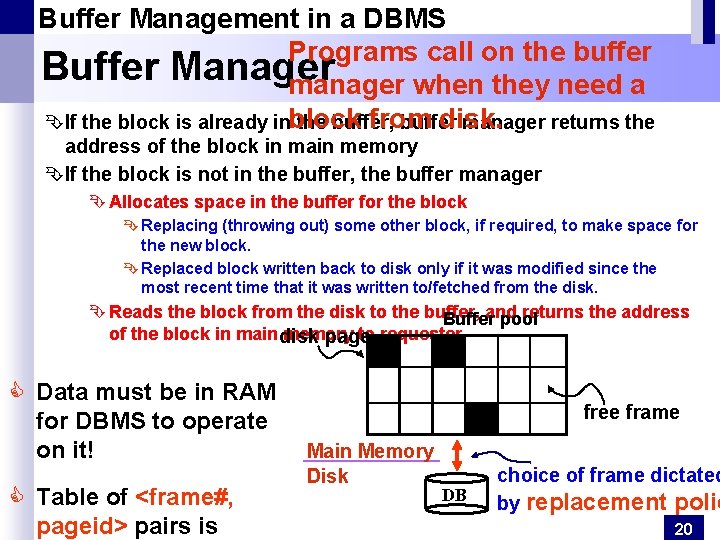

Buffer Management in a DBMS Programs call on the buffer Buffer Manager manager when they need a from disk. ÊIf the block is already inblock the buffer, buffer manager returns the address of the block in main memory ÊIf the block is not in the buffer, the buffer manager Ê Allocates space in the buffer for the block Ê Replacing (throwing out) some other block, if required, to make space for the new block. Ê Replaced block written back to disk only if it was modified since the most recent time that it was written to/fetched from the disk. Ê Reads the block from the disk to the buffer, and returns the address Buffer pool of the block in main disk memory to requester. page C Data must be in RAM for DBMS to operate on it! C Table of <frame#, pageid> pairs is free frame Main Memory Disk DB choice of frame dictated by replacement polic 20

Buffer Management in a DBMS When a Page is Requested. . . Ê If requested page is not in pool: ÊChoose a frame for replacement ÊIf frame is dirty, write it to disk ÊRead requested page into chosen frame Ê Pin the page and return its address. Ê Requestor of page must unpin it, and indicate whether page has been modified: dirty bit is used for this. Ê Page in pool may be requested many times, a pin count is used. A page is a candidate for replacement if pin count = 0. 21

Buffer Management in a DBMS Policy can have Buffer-Replacement Policies big impact on number of I/O’s; Ê Frame/Block is chosen for replacement by a replacement policy: Least-recently-used (LRU), Clock, MRU, etc. Ê Sequential flooding: Nasty situation caused by LRU + repeated sequential scans. Ê # buffer blocks < # pages in file means each page request causes an I/O. Ê MRU much better in this situation Ê Pinned block – memory block that is not allowed to be written back to disk. Ê Toss-immediate strategy – frees the space occupied by a block as soon as the final tuple of that block has been processed Ê Most recently used (MRU) strategy – system must pin the block currently being processed. After the final tuple of that block has been processed, the block is unpinned, and it becomes the most recently used block. Ê Buffer manager Ê can use statistical (in memory) information regarding the probability that a request will reference a particular relation. 22

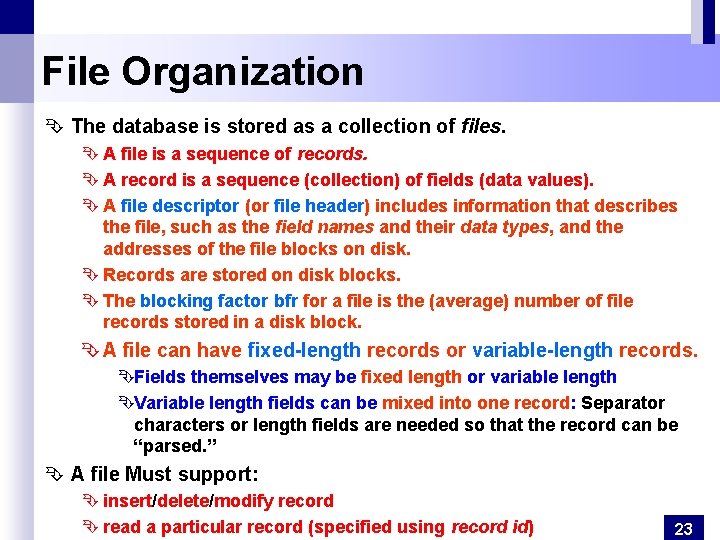

File Organization Ê The database is stored as a collection of files. Ê A file is a sequence of records. Ê A record is a sequence (collection) of fields (data values). Ê A file descriptor (or file header) includes information that describes the file, such as the field names and their data types, and the addresses of the file blocks on disk. Ê Records are stored on disk blocks. Ê The blocking factor bfr for a file is the (average) number of file records stored in a disk block. Ê A file can have fixed-length records or variable-length records. ÊFields themselves may be fixed length or variable length ÊVariable length fields can be mixed into one record: Separator characters or length fields are needed so that the record can be “parsed. ” Ê A file Must support: Ê insert/delete/modify record Ê read a particular record (specified using record id) 23

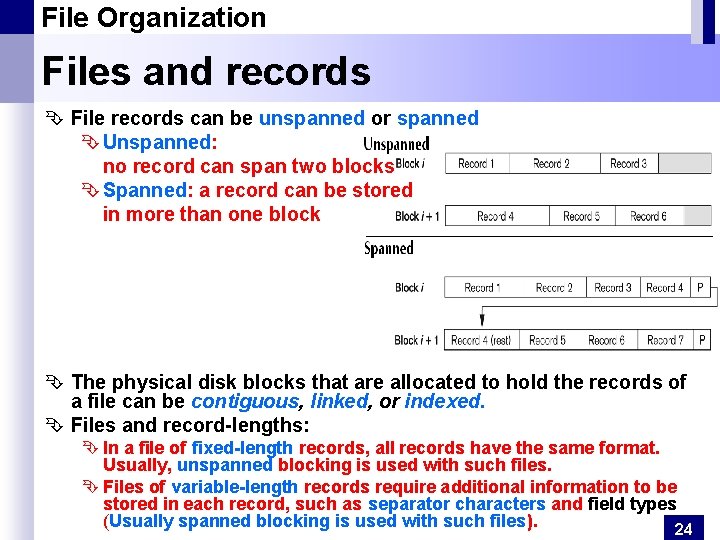

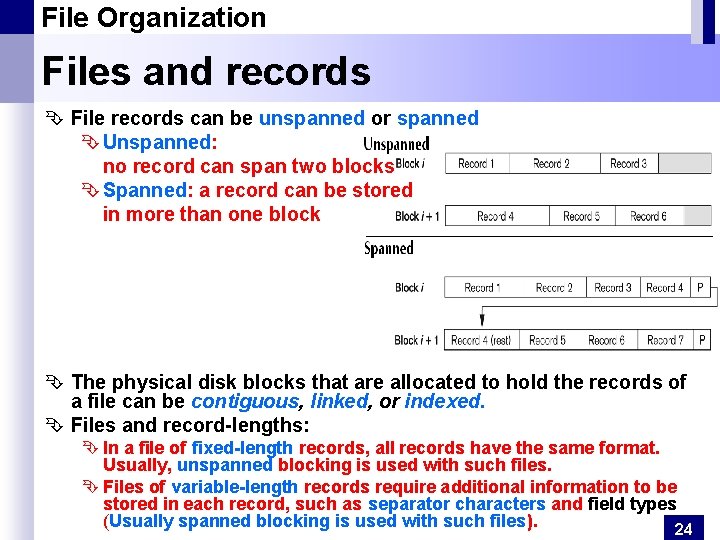

File Organization Files and records Ê File records can be unspanned or spanned Ê Unspanned: no record can span two blocks Ê Spanned: a record can be stored in more than one block Ê The physical disk blocks that are allocated to hold the records of a file can be contiguous, linked, or indexed. Ê Files and record-lengths: Ê In a file of fixed-length records, all records have the same format. Usually, unspanned blocking is used with such files. Ê Files of variable-length records require additional information to be stored in each record, such as separator characters and field types (Usually spanned blocking is used with such files). 24

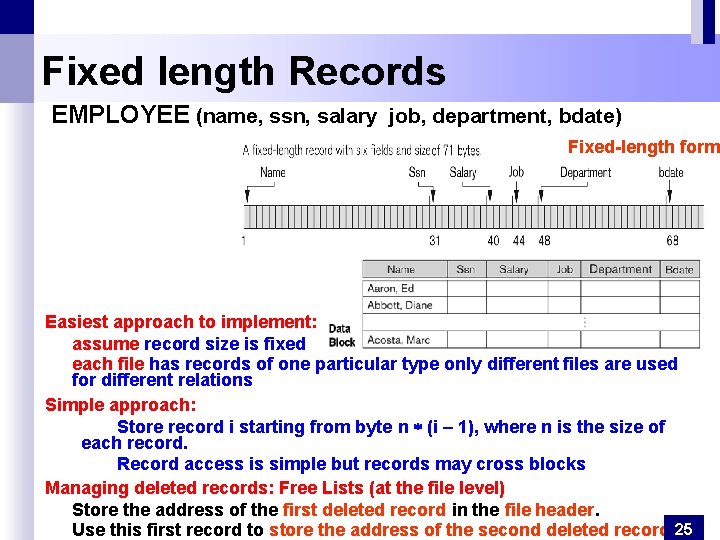

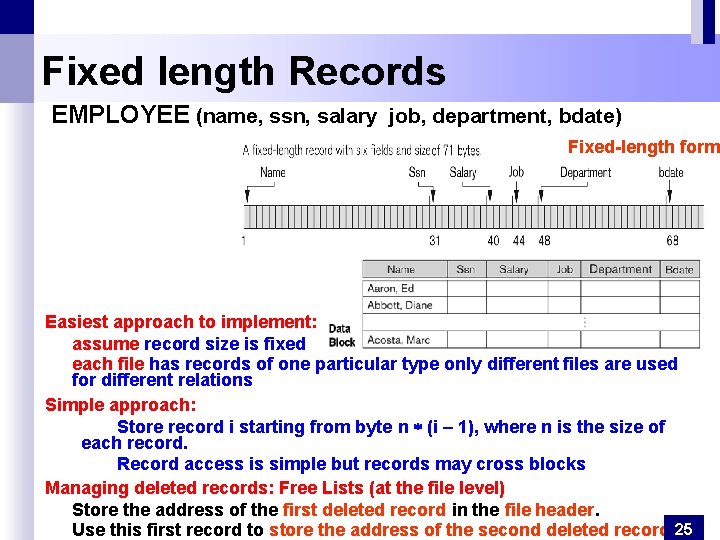

Fixed length Records EMPLOYEE (name, ssn, salary job, department, bdate) Fixed-length form Easiest approach to implement: assume record size is fixed each file has records of one particular type only different files are used for different relations Simple approach: Store record i starting from byte n (i – 1), where n is the size of each record. Record access is simple but records may cross blocks Managing deleted records: Free Lists (at the file level) Store the address of the first deleted record in the file header. Use this first record to store the address of the second deleted record, 25

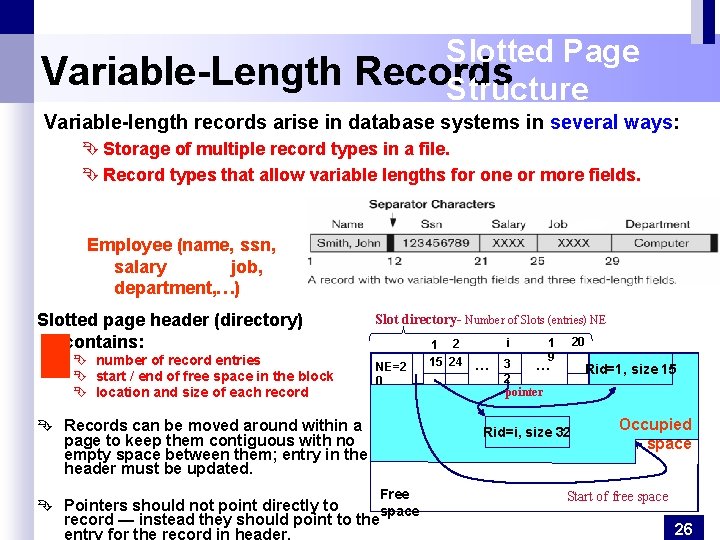

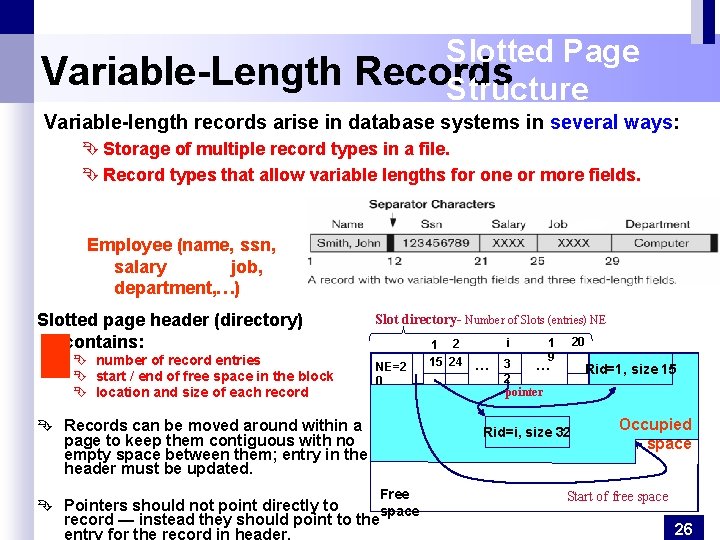

Variable-Length Slotted Page Records Structure Variable-length records arise in database systems in several ways: Ê Storage of multiple record types in a file. Ê Record types that allow variable lengths for one or more fields. Employee (name, ssn, salary job, department, …) Slotted page header (directory) contains: Ê number of record entries Ê start / end of free space in the block Ê location and size of each record Slot directory- Number of Slots (entries) NE NE=2 0 Ê Records can be moved around within a page to keep them contiguous with no empty space between them; entry in the header must be updated. 1 2 15 24 i … 20 1 9 16 3 … 2 pointer Rid=1, size 15 Rid=i, size 32 Free Ê Pointers should not point directly to space record — instead they should point to the entry for the record in header. Occupied space Start of free space 26

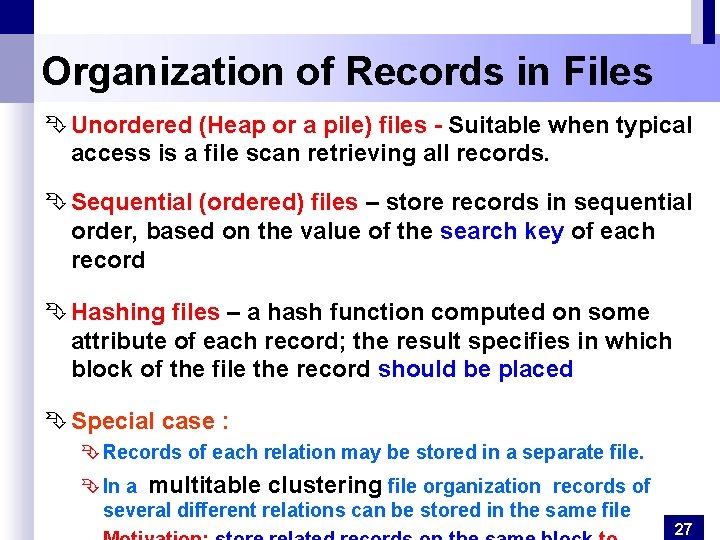

Organization of Records in Files Ê Unordered (Heap or a pile) files - Suitable when typical access is a file scan retrieving all records. Ê Sequential (ordered) files – store records in sequential order, based on the value of the search key of each record Ê Hashing files – a hash function computed on some attribute of each record; the result specifies in which block of the file the record should be placed Ê Special case : Ê Records of each relation may be stored in a separate file. Ê In a multitable clustering file organization records of several different relations can be stored in the same file 27

Organization of Records in Files Unordered (Heap) Files Ê Also called Heap or a pile files - Simplest file structure contains records in no particular order. Ê Basically, new records are inserted at the end of the file, but a record can be placed anywhere in the file where there is space Ê Record insertion is quite efficient. Ê A linear search through the file records is necessary to search for a record. Ê Reading the records in order of a particular field requires sorting the file records. Ê As file grows and shrinks, disk pages are allocated and deallocated. Ê To support record level operations, we must: Ê keep track of the pages in a file Ê keep track of free space on pages 28

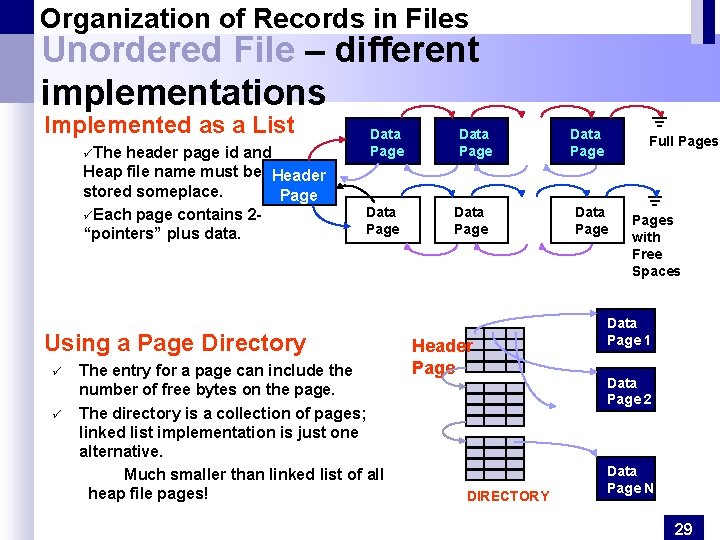

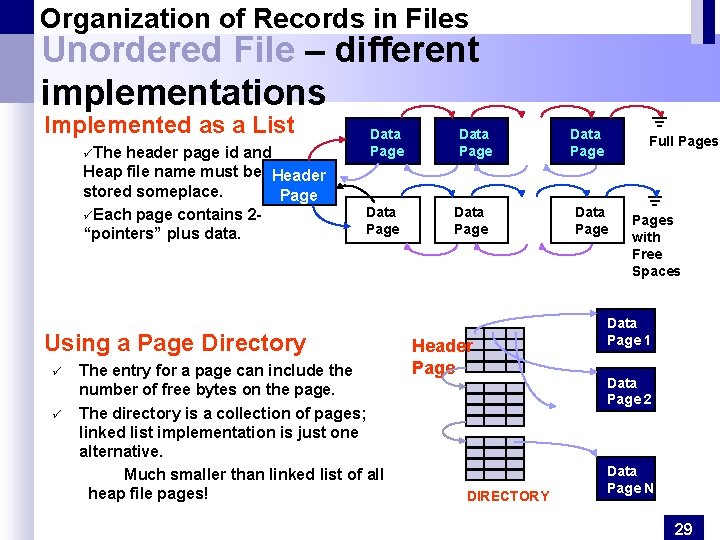

Organization of Records in Files Unordered File – different implementations Implemented as a List üThe header page id and Heap file name must be Header stored someplace. Page üEach page contains 2“pointers” plus data. Data Page Using a Page Directory ü ü The entry for a page can include the number of free bytes on the page. The directory is a collection of pages; linked list implementation is just one alternative. Much smaller than linked list of all heap file pages! Data Page Header Page DIRECTORY Data Page Full Pages Data Pages with Free Spaces Data Page 1 Data Page 2 Data Page N 29

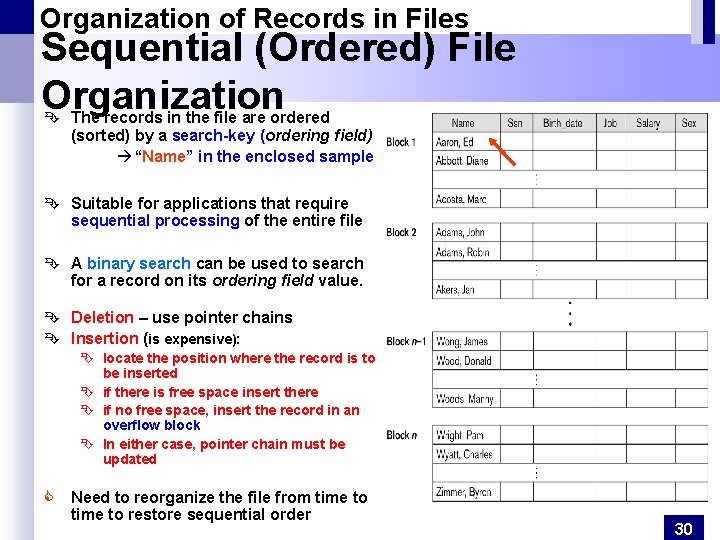

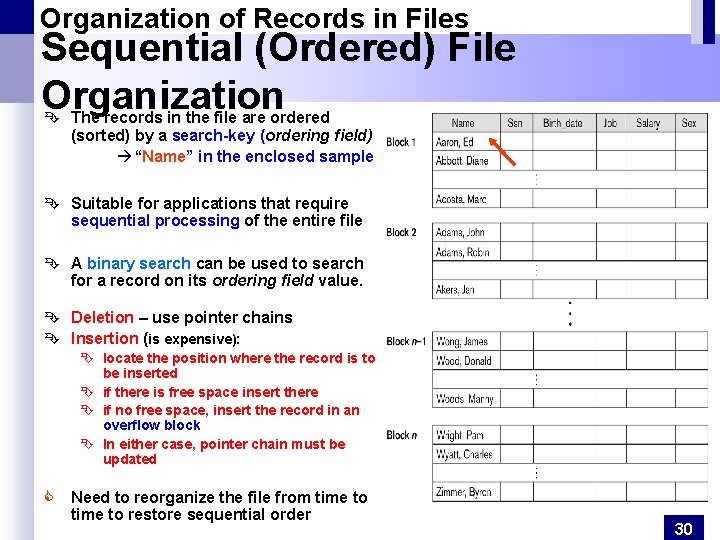

Organization of Records in Files Sequential (Ordered) File Organization Ê The records in the file are ordered (sorted) by a search-key (ordering field) à “Name” in the enclosed sample Ê Suitable for applications that require sequential processing of the entire file Ê A binary search can be used to search for a record on its ordering field value. Ê Deletion – use pointer chains Ê Insertion (is expensive): Ê locate the position where the record is to be inserted Ê if there is free space insert there Ê if no free space, insert the record in an overflow block Ê In either case, pointer chain must be updated C Need to reorganize the file from time to restore sequential order 30

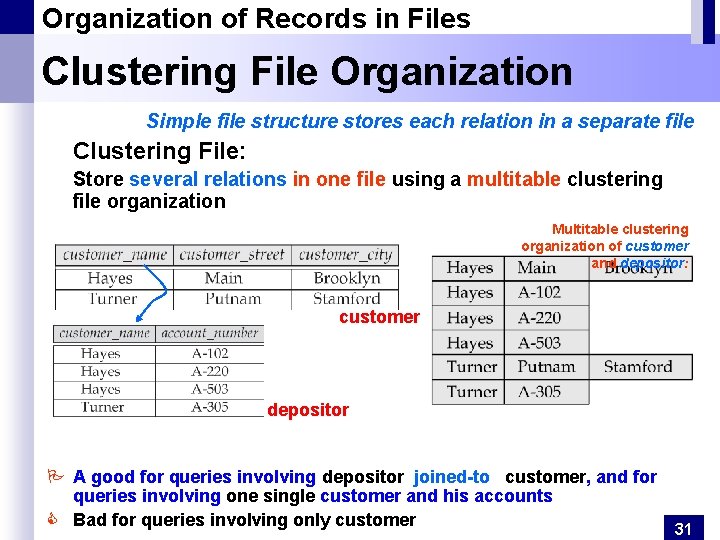

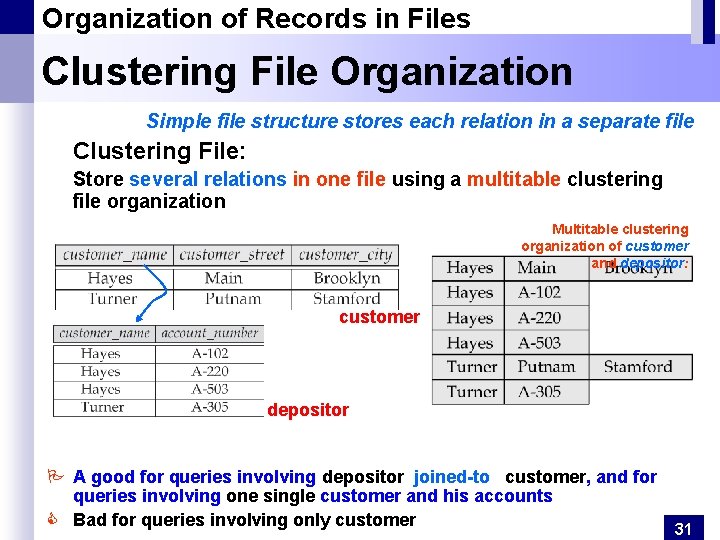

Organization of Records in Files Clustering File Organization Simple file structure stores each relation in a separate file Clustering File: Store several relations in one file using a multitable clustering file organization Multitable clustering organization of customer and depositor: customer depositor P A good for queries involving depositor joined-to customer, and for queries involving one single customer and his accounts C Bad for queries involving only customer 31

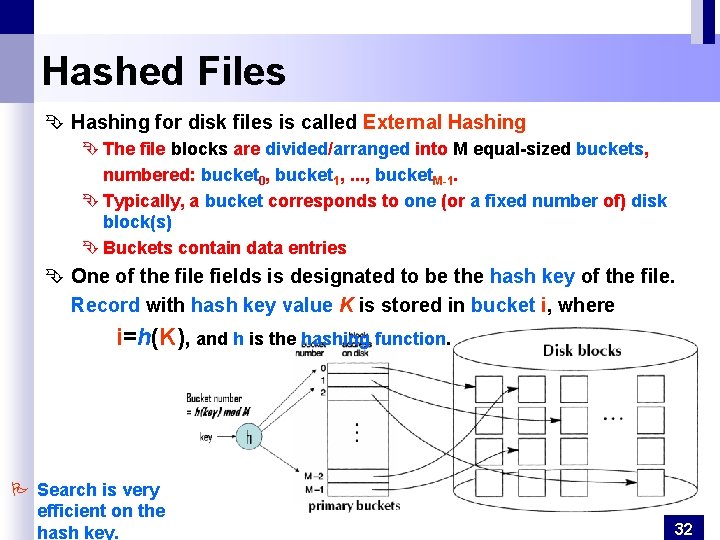

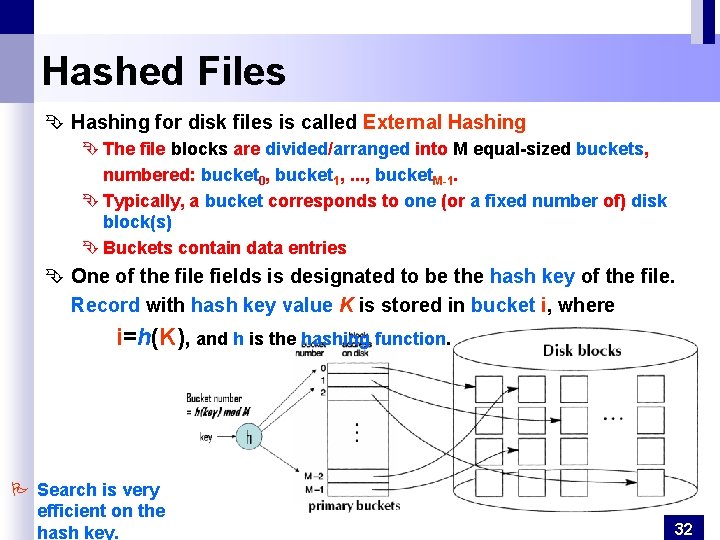

Hashed Files Ê Hashing for disk files is called External Hashing Ê The file blocks are divided/arranged into M equal-sized buckets, numbered: bucket 0, bucket 1, . . . , bucket. M-1. Ê Typically, a bucket corresponds to one (or a fixed number of) disk block(s) Ê Buckets contain data entries Ê One of the file fields is designated to be the hash key of the file. Record with hash key value K is stored in bucket i, where i=h(K), and h is the hashing function. P Search is very efficient on the hash key. 32

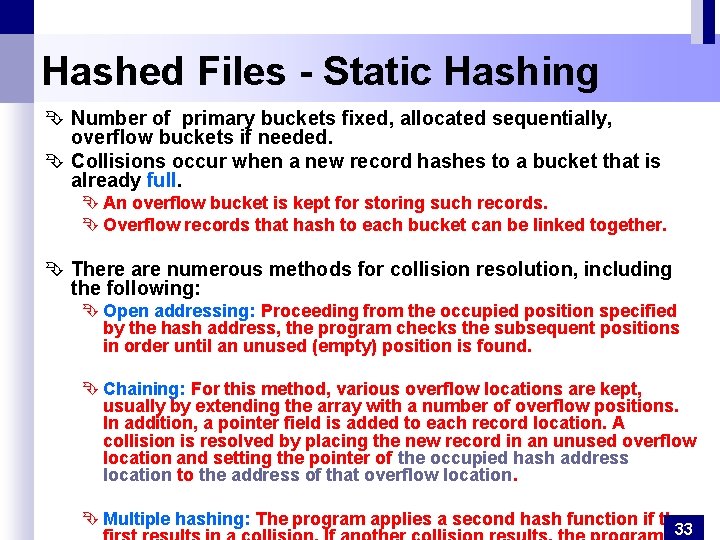

Hashed Files - Static Hashing Ê Number of primary buckets fixed, allocated sequentially, overflow buckets if needed. Ê Collisions occur when a new record hashes to a bucket that is already full. Ê An overflow bucket is kept for storing such records. Ê Overflow records that hash to each bucket can be linked together. Ê There are numerous methods for collision resolution, including the following: Ê Open addressing: Proceeding from the occupied position specified by the hash address, the program checks the subsequent positions in order until an unused (empty) position is found. Ê Chaining: For this method, various overflow locations are kept, usually by extending the array with a number of overflow positions. In addition, a pointer field is added to each record location. A collision is resolved by placing the new record in an unused overflow location and setting the pointer of the occupied hash address location to the address of that overflow location. Ê Multiple hashing: The program applies a second hash function if the 33

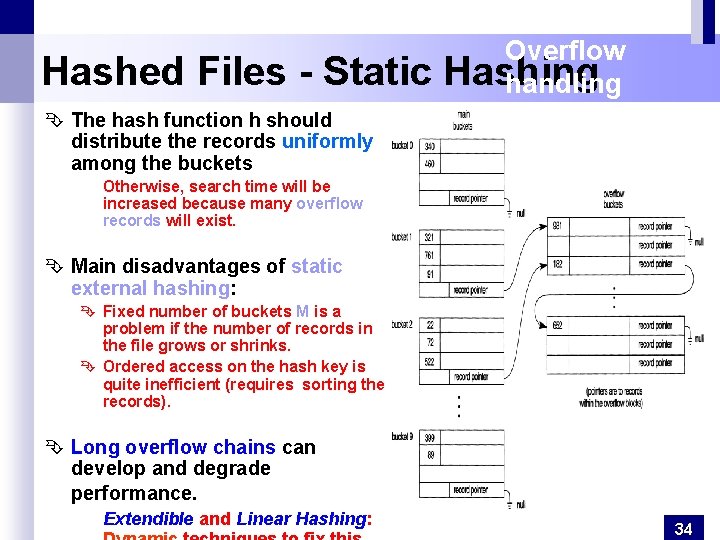

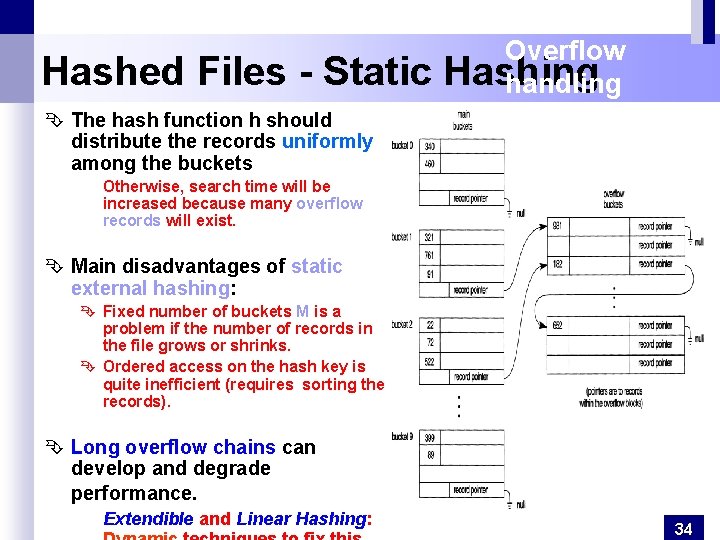

Hashed Files - Static Overflow Hashing handling Ê The hash function h should distribute the records uniformly among the buckets Otherwise, search time will be increased because many overflow records will exist. Ê Main disadvantages of static external hashing: Ê Fixed number of buckets M is a problem if the number of records in the file grows or shrinks. Ê Ordered access on the hash key is quite inefficient (requires sorting the records). Ê Long overflow chains can develop and degrade performance. Extendible and Linear Hashing: 34

Hashed Files Dynamic And Extendible Hashed Files Ê Dynamic Hashing Techniques Ê Hashing techniques are adapted to allow the dynamic growth and shrinking of the number of file records. Ê These techniques include the following: extendible hashing, and linear hashing. Ê Both dynamic and extendible hashing use the binary representation of the hash value h(K) in order to access a directory. Ê In dynamic hashing the directory is a binary tree. Ê In extendible hashing the directory is an array of size 2 d where d is called the global depth. Ê The directories can be stored on disk, and they expand or shrink dynamically. Ê Directory entries point to the disk blocks that contain the stored records. Ê An insertion in a disk block that is full causes the block to split into two blocks and the records are redistributed among the two blocks. Ê The directory is updated appropriately. Ê Dynamic and extendible hashing do not require an overflow area. Ê Linear hashing does require an overflow area but does not use a 35

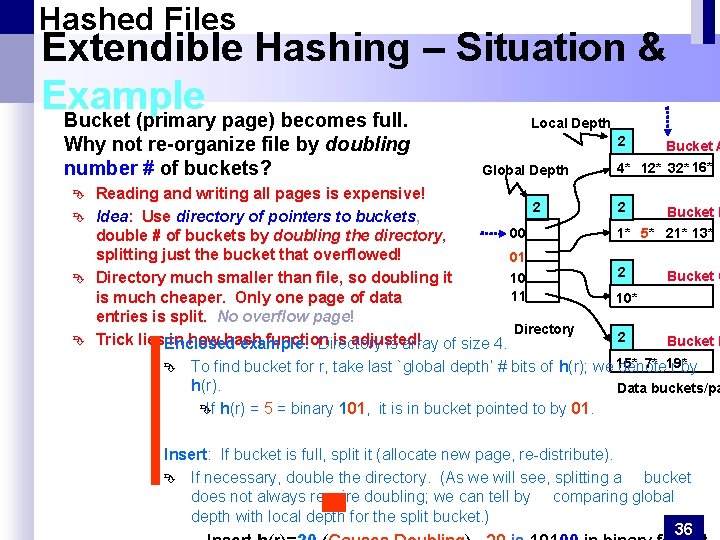

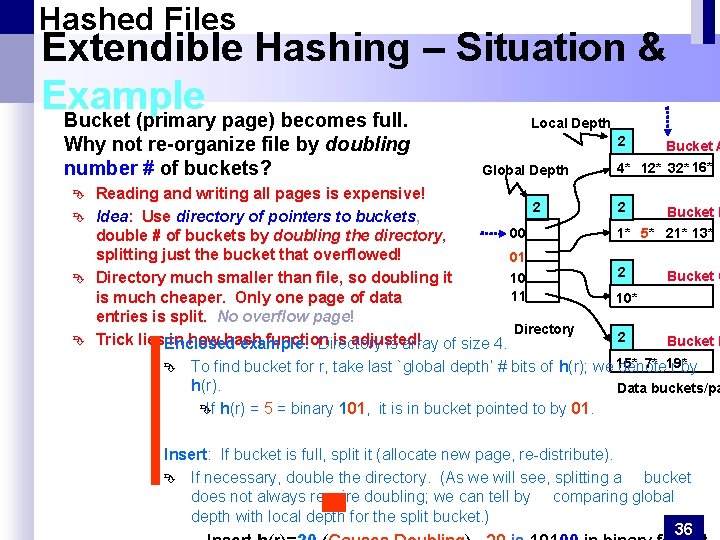

Hashed Files Extendible Hashing – Situation & Example Bucket (primary page) becomes full. Local Depth Why not re-organize file by doubling number # of buckets? Ê Ê 2 Global Depth Reading and writing all pages is expensive! 2 Idea: Use directory of pointers to buckets, 00 double # of buckets by doubling the directory, splitting just the bucket that overflowed! 01 10 Directory much smaller than file, so doubling it 11 is much cheaper. Only one page of data entries is split. No overflow page! Directory Trick lies. Enclosed in how hash function is adjusted! example: Directory is array of size 4. Ê Bucket A 4* 12* 32* 16* 2 Bucket B 1* 5* 21* 13* 2 Bucket C 10* 2 Bucket D 7* 19* To find bucket for r, take last `global depth’ # bits of h(r); we 15* denote r by h(r). Data buckets/pa Ê If h(r) = 5 = binary 101, it is in bucket pointed to by 01. Insert: If bucket is full, split it (allocate new page, re-distribute). Ê If necessary, double the directory. (As we will see, splitting a bucket does not always require doubling; we can tell by comparing global depth with local depth for the split bucket. ) 36

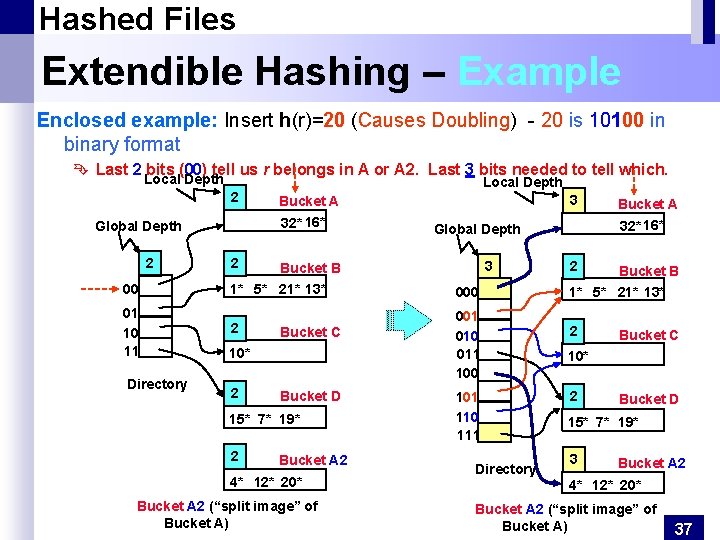

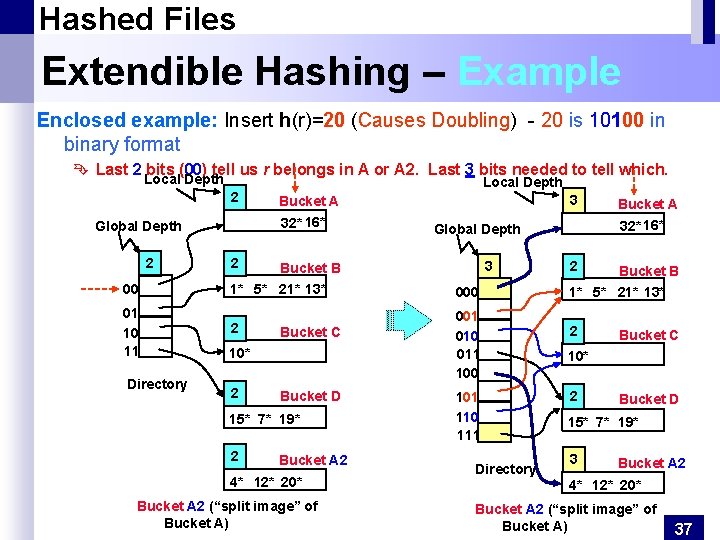

Hashed Files Extendible Hashing – Example Enclosed example: Insert h(r)=20 (Causes Doubling) - 20 is 10100 in binary format Ê Last 2 bits (00) tell us r belongs in A or A 2. Last 3 bits needed to tell which. Local Depth 2 2 1* 5* 21* 13* 01 10 11 2 Bucket C 10* 2 Bucket D 15* 7* 19* 2 3 Bucket A 2 4* 12* 20* Bucket A 2 (“split image” of Bucket A) 000 001 010 011 100 101 110 111 Directory Bucket A 32* 16* Global Depth Bucket B 00 Directory 3 Bucket A 32* 16* Global Depth 2 Local Depth 2 Bucket B 1* 5* 21* 13* 2 Bucket C 10* 2 Bucket D 15* 7* 19* 3 Bucket A 2 4* 12* 20* Bucket A 2 (“split image” of Bucket A) 37

Hashed Files- Extendible Hashing Points to Note & Comments on Extendible Hashing Ê Global depth of directory: Max # of bits needed to tell which bucket an entry belongs to. Ê Local depth of a bucket: # of bits used to determine if an entry belongs to this bucket. Ê When does bucket split cause directory doubling? Before insert, local depth of bucket = global depth. Ê Ê Insert causes local depth to become > global depth; directory is doubled by copying it over and `fixing’ pointer to split image page. (Use of least significant bits enables efficient doubling via copying of directory!) Ê If directory fits in memory, equality search answered with one disk access; else two. Ê Ê Ê 100 MB file, 100 bytes/rec, 4 K pages contains 1, 000 records (as data entries) and 25, 000 directory elements; chances are high that directory will fit in memory. Directory grows in spurts, and, if the distribution of hash values is skewed, directory can grow large. Multiple entries with same hash value cause problems! Delete: 38

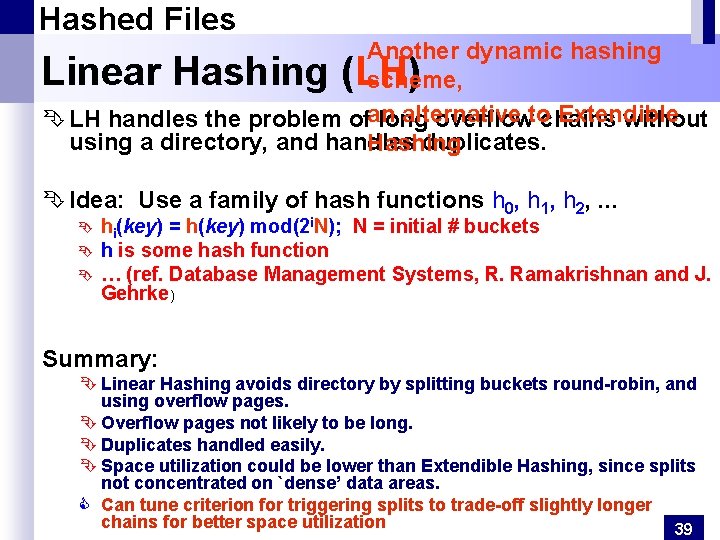

Hashed Files Another dynamic hashing scheme, alternative Extendible Ê LH handles the problem ofan long overflowtochains without using a directory, and handles duplicates. Hashing Linear Hashing (LH) Ê Idea: Use a family of hash functions h 0, h 1, h 2, . . . Ê Ê Ê hi(key) = h(key) mod(2 i. N); N = initial # buckets h is some hash function … (ref. Database Management Systems, R. Ramakrishnan and J. Gehrke) Summary: Ê Linear Hashing avoids directory by splitting buckets round-robin, and using overflow pages. Ê Overflow pages not likely to be long. Ê Duplicates handled easily. Ê Space utilization could be lower than Extendible Hashing, since splits not concentrated on `dense’ data areas. C Can tune criterion for triggering splits to trade-off slightly longer chains for better space utilization 39

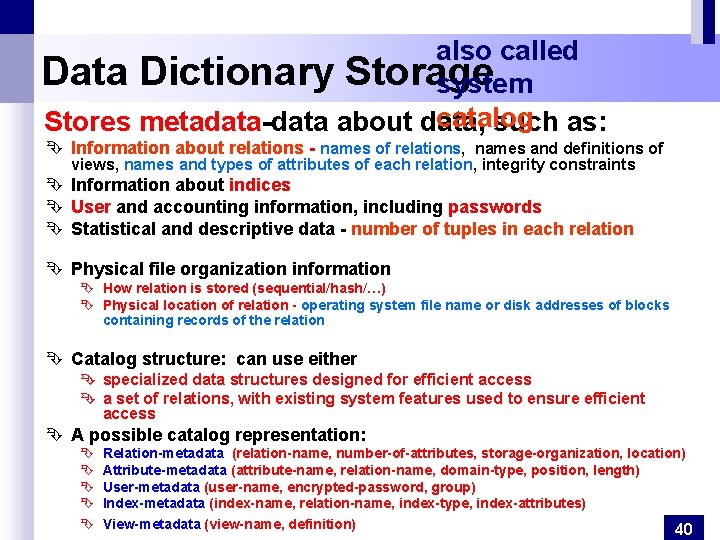

also called Data Dictionary Storage system catalog Stores metadata-data about data, such as: Ê Information about relations - names of relations, names and definitions of views, names and types of attributes of each relation, integrity constraints Ê Information about indices Ê User and accounting information, including passwords Ê Statistical and descriptive data - number of tuples in each relation Ê Physical file organization information Ê How relation is stored (sequential/hash/…) Ê Physical location of relation - operating system file name or disk addresses of blocks containing records of the relation Ê Catalog structure: can use either Ê specialized data structures designed for efficient access Ê a set of relations, with existing system features used to ensure efficient access Ê A possible catalog representation: Ê Ê Ê Relation-metadata (relation-name, number-of-attributes, storage-organization, location) Attribute-metadata (attribute-name, relation-name, domain-type, position, length) User-metadata (user-name, encrypted-password, group) Index-metadata (index-name, relation-name, index-type, index-attributes) View-metadata (view-name, definition) 40