STEMI treatment Role of fibrinolysis Content Importance of

STEMI treatment Role of fibrinolysis

Content Importance of time Treatment strategies & guidelines STEMI networks Fibrinolytic agents Clinical studies Registries Take home points Metalyse® prescribing information

Importance of time Treatment strategies & guidelines STEMI networks Fibrinolytic agents Clinical studies Registries Take home points Metalyse® prescribing information

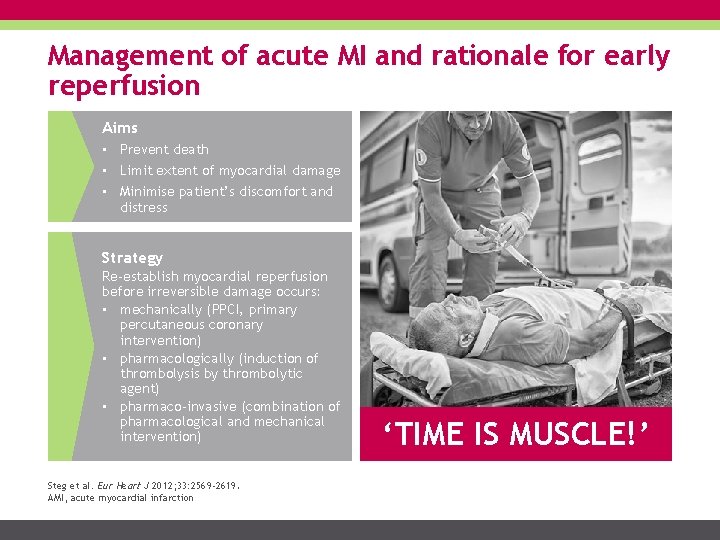

Management of acute MI and rationale for early reperfusion Aims • Prevent death • Limit extent of myocardial damage • Minimise patient’s discomfort and distress Strategy Re-establish myocardial reperfusion before irreversible damage occurs: • mechanically (PPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention) • pharmacologically (induction of thrombolysis by thrombolytic agent) • pharmaco-invasive (combination of pharmacological and mechanical intervention) Steg et al. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 2569 -2619. AMI, acute myocardial infarction ‘TIME IS MUSCLE!’

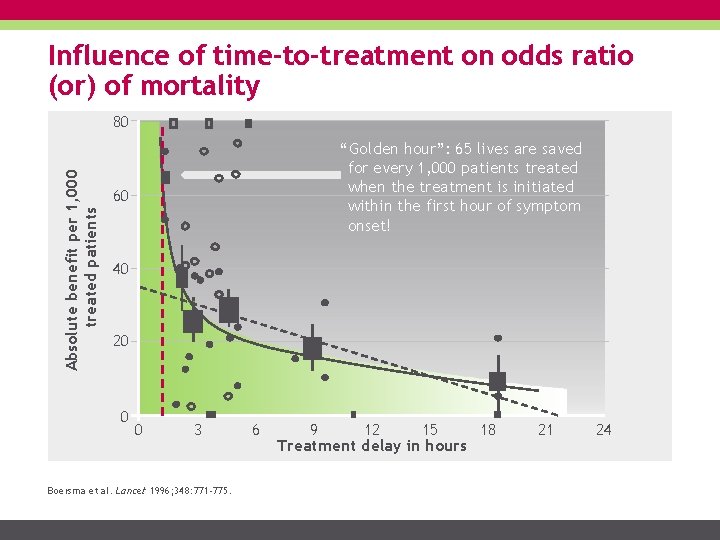

Influence of time-to-treatment on odds ratio (or) of mortality Absolute benefit per 1, 000 treated patients 80 “Golden hour”: 65 lives are saved for every 1, 000 patients treated when the treatment is initiated within the first hour of symptom onset! 60 40 20 0 0 3 Boersma et al. Lancet 1996; 348: 771 -775. 6 9 12 15 18 Treatment delay in hours 21 24

Time delay elements in thrombolysis Call to on scene On scene Transfer Door-to-needle-time Rural patients receiving thrombolysis in hospital Thrombolysis Urban patients receiving thrombolysis in hospital Thrombolysis Rural patients receiving pre-hospital thrombolysis Thrombolysis 0 50 100 MEDIAN TIMES IN MINUTES Adapted from Pedley et al. BMJ 2003; 327: 22 -26. 150

Improving time to treatment Public education & AMI awareness reduce symptom onset-to-call times Medical professionals reduce first medical contact (FMC)-to-treatment times STEMI networks Foster strong communication among medical professionals involved in the treatment of AMI Facilitate pre-hospital diagnosis and thrombolysis or referral to a PCIcapable facility within guideline-specific timeframes

Treatment strategies & guidelines Importance of time Treatment strategies & guidelines STEMI networks Fibrinolytic agents Clinical studies Registries Take home points Metalyse® prescribing information

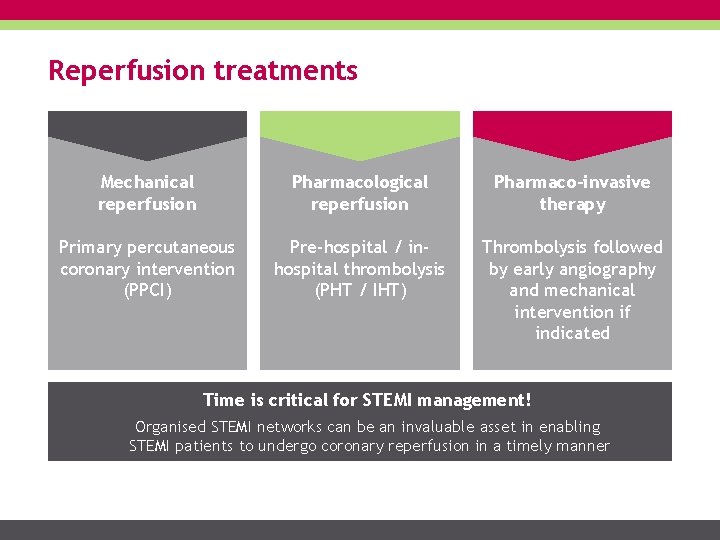

Reperfusion treatments Mechanical reperfusion Pharmacological reperfusion Pharmaco-invasive therapy Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) Pre-hospital / inhospital thrombolysis (PHT / IHT) Thrombolysis followed by early angiography and mechanical intervention if indicated Time is critical for STEMI management! Organised STEMI networks can be an invaluable asset in enabling STEMI patients to undergo coronary reperfusion in a timely manner

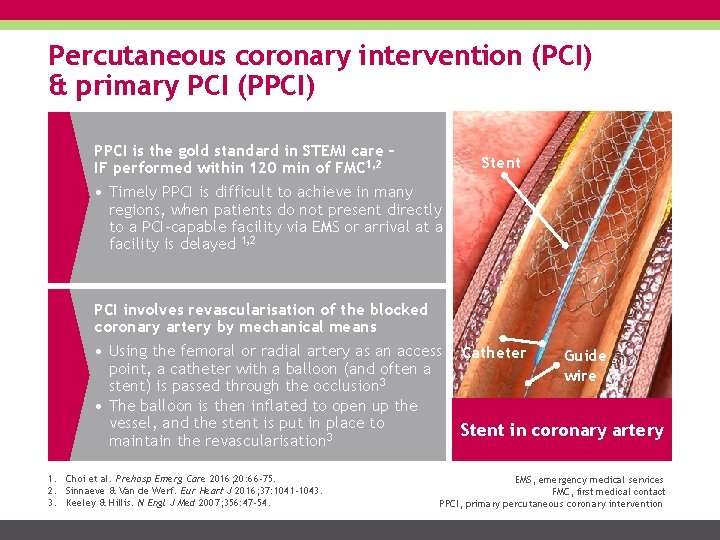

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) & primary PCI (PPCI) PPCI is the gold standard in STEMI care – IF performed within 120 min of FMC 1, 2 Stent • Timely PPCI is difficult to achieve in many regions, when patients do not present directly to a PCI-capable facility via EMS or arrival at a facility is delayed 1, 2 PCI involves revascularisation of the blocked coronary artery by mechanical means • Using the femoral or radial artery as an access point, a catheter with a balloon (and often a stent) is passed through the occlusion 3 • The balloon is then inflated to open up the vessel, and the stent is put in place to maintain the revascularisation 3 1. Choi et al. Prehosp Emerg Care 2016; 20: 66 -75. 2. Sinnaeve & Van de Werf. Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 1041 -1043. 3. Keeley & Hillis. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 47 -54. Catheter Guide wire Stent in coronary artery EMS, emergency medical services FMC, first medical contact PPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention

STEMI treatment guidelines STEMI guidelines state that acute myocardial ischaemia (<12 h) should be treated with reperfusion therapy 1, 2 Guidelines from the ACC/AHA 1 and ESC 2 agree that: 1. Primary PCI (PPCI) is the gold-standard of reperfusion treatment for STEMI if delivered ≤ 120 minutes of diagnosis 2. Where this is not possible, fibrinolysis should be performed with a fibrin-specific agent (tenecteplase, alteplase or reteplase) as soon as possible within 10 min from STEMI diagnosis, preferably pre-hospital, alongside adjunctive antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies, and patients should be transferred to a PCI-capable centre for subsequent therapy 1. O’Gara et al. Circulation 2013; 127: e 362 -e 425. 2. ESC Task Force. Eur Heart J 2018; 39(2): 119– 177. ACC/AHA, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association ESC, European Society of Cardiology PPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention

ESC STEMI guidelines 2017: reperfusion strategies Symptom onset Early phase of STEMI 0 hours 3 hours Evolved STEMI 12 hours Recent STEMI 48 hours Primary PCI I A (if symptoms, haemodynamic instability, or arrhythmias) Fibrinolysis (if PCI cannot be performed within 120 min from STEMI diagnosis) I A Adapted from ESC Task Force. Eur Heart J 2018; 39(2): 119– 177. I C Primary PCI Routine PCI (asymptomatic stable patients) IIa B III A

ESC STEMI guidelines 2017: reperfusion strategies Time from diagnosis Time to PCI centre STEMI diagnosis (ECG) ≤ 2 h 0 Alert & immediate transfer to PCI centre max. 10 min delay to administration Pharmacoinvasive strategy* Bolus fibrinolytic 10 min Primary PCI Rescue PCI No Reperfusion successful? Yes ≥ 120 min Transfer to PCI centre 60 -90 min >2 h 2 h Routine PCI 24 h Adapted from ESC Task Force. Eur Heart J 2018; 39(2): 119– 177. *If fibrinolysis is contraindicated, transfer to PCI centre regardless of time to PCI

STEMI networks Importance of time Treatment strategies & guidelines STEMI networks Fibrinolytic agents Clinical studies Registries Take home points Metalyse® prescribing information

STEMI networks aims and guidelines The aim of a STEMI network is to ensure early recognition of STEMI, shorten time delays to treatment, and optimise outcomes 1 Network organisation recommendations from the ACC/AHA 2 and ESC 3 1. Single emergency telephone number 2. Protocols for standardised care (diagnosis, therapy, transfer) 3. Optimal pre-hospital care (ambulances equipped with ECGs and defibrillators, correct/prompt diagnosis, pre-activation of the cath lab, early initiation of thrombolysis if timely PPCI is not possible) 4. Bypass non-PPCI capable hospitals to increase proportion of patients receiving timely PPCI 5. Cardiology/intensive care specialist as network leader 6. Involve healthcare authorities 7. Continual quality improvement with prospective registries & regular meetings of involved parties 1. Huber et al. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 1526 -1532. 2. O’Gara et al. Circulation 2013; 127: e 362 -e 425. 3. ESC Task Force. Eur Heart J 2018; 39(2): 119– 177. PPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention

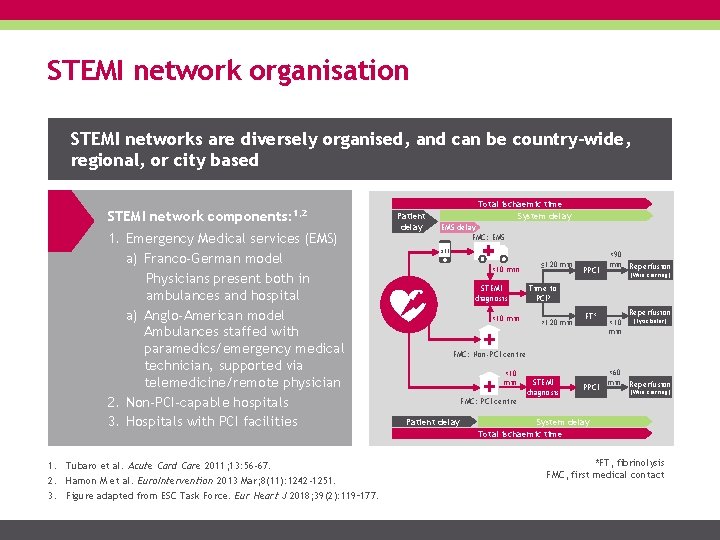

STEMI network organisation STEMI networks are diversely organised, and can be country-wide, regional, or city based STEMI network components: 1, 2 1. Emergency Medical services (EMS) a) Franco-German model Physicians present both in ambulances and hospital a) Anglo-American model Ambulances staffed with paramedics/emergency medical technician, supported via telemedicine/remote physician 2. Non-PCI-capable hospitals 3. Hospitals with PCI facilities 1. Tubaro et al. Acute Card Care 2011; 13: 56 -67. 2. Hamon M et al. Euro. Intervention 2013 Mar; 8(11): 1242 -1251. 3. Figure adapted from ESC Task Force. Eur Heart J 2018; 39(2): 119– 177. Patient delay Total ischaemic time System delay EMS delay FMC: EMS 911 <10 min STEMI diagnosis <10 min ≤ 120 min PPCI <90 min Reperfusion (Wire crossing) Time to PCI? >120 min FT* Reperfusion <10 min (Lytic bolus) FMC: Non-PCI centre <10 min STEMI diagnosis PPCI <60 min Reperfusion (Wire crossing) FMC: PCI centre Patient delay System delay Total ischaemic time *FT, fibrinolysis FMC, first medical contact

European STEMI networks: two models Vienna STEMI network 1, 2 • French Service d’Aide Médicale Urgente (SAMU) system 2 Central triage system started in 2003, organised by Vienna Ambulance System • • 24/7 access to cath lab facilities with experienced interventionalists • • Guaranteed through rotational system between tertiary centres: all centres available during the day & only two centres at night • Fibrinolysis is a part of reperfusion strategy when patient transfer is delayed >90 mins • • Since initiation, the number of patients receiving timely PPCI has increased and the numbers receiving fibrinolysis have decreased (now only ∼ 3% of patients); marked decline in numbers receiving no reperfusion therapy • 1. Huber et al. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 1526 -1532. 2. Danchin. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 2009; 2: 901 -908. • Nationwide system implemented in 1995, & monitored by FAST-MI STEMI registry One SAMU medical response centre for each region, responsible for mobile intensive care unit (MICU) dispatch (1 physician, 1 nurse, & a driver (trained emergency medical technician) provide basic/advanced life support on-site &/or during transfer) MICU alerts medical centre ahead of arrival about medical status of the patient to allow direct admission & avoid treatment delay Implementation has improved outcomes, and increased reperfusion, mainly due to increased PPCI When PPCI is not possible, a pharmacoinvasive strategy is implemented

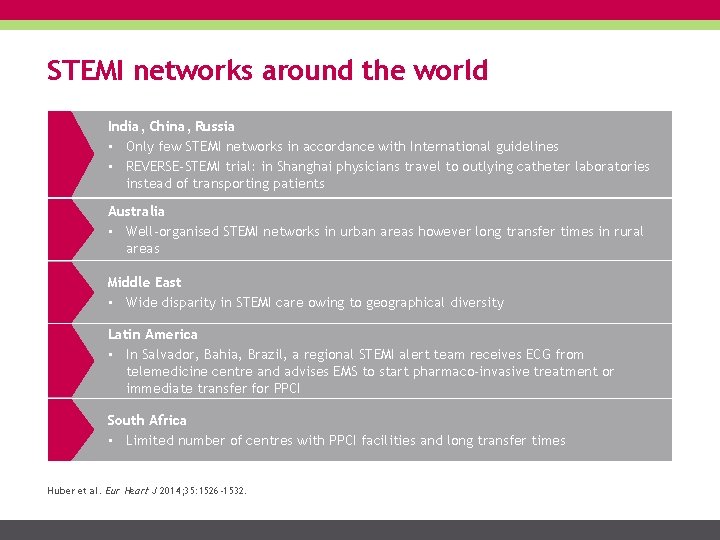

STEMI networks around the world India, China, Russia • Only few STEMI networks in accordance with International guidelines • REVERSE-STEMI trial: in Shanghai physicians travel to outlying catheter laboratories instead of transporting patients Australia • Well-organised STEMI networks in urban areas however long transfer times in rural areas Middle East • Wide disparity in STEMI care owing to geographical diversity Latin America • In Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, a regional STEMI alert team receives ECG from telemedicine centre and advises EMS to start pharmaco-invasive treatment or immediate transfer for PPCI South Africa • Limited number of centres with PPCI facilities and long transfer times Huber et al. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 1526 -1532.

Future directions to improve STEMI management • • • Education campaign 1 Community organisation 1 Unique European-wide emergency telephone number 1, 2 Automated external defibrillators (AEDs) in public places 1 Standardised written STEMI management protocols 1* Ambulances (vehicles, helicopters, planes) equipped with defibrillators, 17 -lead ECG, trained professionals capable of basic and advanced life support or initiation of FT in case of delays 1, 2 ECG transmission/teleconsultation 1 -3 Single number to activate catheterisation laboratory 1, 3 Experienced cardiologist or intensive care specialist to lead the network 1 24/7 accessible tertiary care centres 1, 2 Increased use of radial access in STEMI patients referred for PPCI to reduce bleeding complications 1, 2 1. Huber et al. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 1526 -1532. 2. ESC Task Force. Eur Heart J 2018; 39(2): 119– 177 3. Danchin. JACC Cardiovasc Interven 2009; 2: 901 -908. *Procedures and treatment should be agreed between network members and put in writing

Fibrinolytic agents Importance of time Treatment strategies & guidelines STEMI networks Fibrinolytic agents Clinical studies Registries Take home points Metalyse® prescribing information

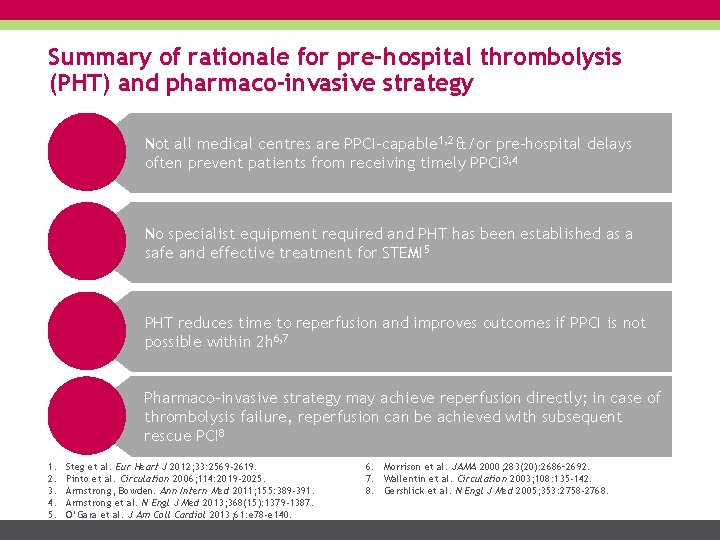

Summary of rationale for pre-hospital thrombolysis (PHT) and pharmaco-invasive strategy Not all medical centres are PPCI-capable 1, 2 &/or pre-hospital delays often prevent patients from receiving timely PPCI 3, 4 No specialist equipment required and PHT has been established as a safe and effective treatment for STEMI 5 PHT reduces time to reperfusion and improves outcomes if PPCI is not possible within 2 h 6, 7 Pharmaco-invasive strategy may achieve reperfusion directly; in case of thrombolysis failure, reperfusion can be achieved with subsequent rescue PCI 8 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Steg et al. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 2569 -2619. Pinto et al. Circulation 2006; 114: 2019 -2025. Armstrong, Bowden. Ann Intern Med 2011; 155: 389 -391. Armstrong et al. N Engl J Med 2013; 368(15): 1379 -1387. O’Gara et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61: e 78 -e 140. 6. Morrison et al. JAMA 2000; 283(20): 2686– 2692. 7. Wallentin et al. Circulation 2003; 108: 135 -142. 8. Gershlick et al. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 2758 -2768.

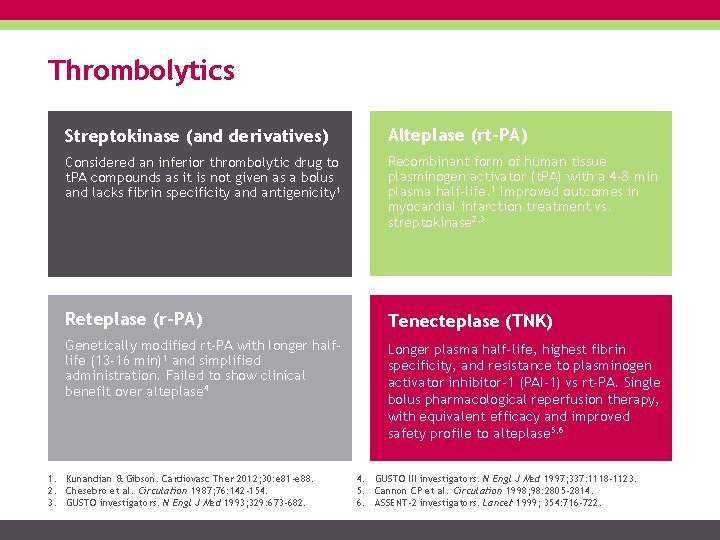

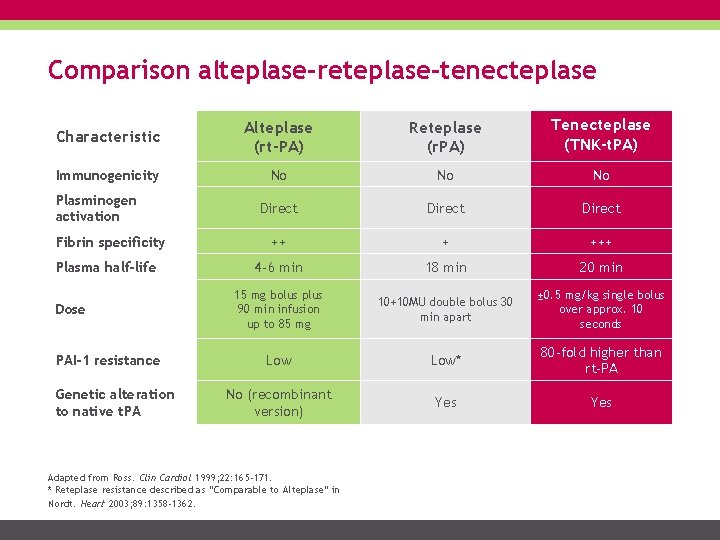

Thrombolytics Streptokinase (and derivatives) Alteplase (rt-PA) Considered an inferior thrombolytic drug to t. PA compounds as it is not given as a bolus and lacks fibrin specificity and antigenicity 1 Recombinant form of human tissue plasminogen activator (t. PA) with a 4 -8 min plasma half-life. 1 Improved outcomes in myocardial infarction treatment vs. streptokinase 2, 3 Reteplase (r-PA) Tenecteplase (TNK) Genetically modified rt-PA with longer halflife (13 -16 min)1 and simplified administration. Failed to show clinical benefit over alteplase 4 Longer plasma half-life, highest fibrin specificity, and resistance to plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) vs rt-PA. Single bolus pharmacological reperfusion therapy, with equivalent efficacy and improved safety profile to alteplase 5, 6 1. Kunandian & Gibson. Cardiovasc Ther 2012; 30: e 81 -e 88. 2. Chesebro et al. Circulation 1987; 76: 142 -154. 3. GUSTO investigators. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 673 -682. 4. GUSTO III investigators. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 1118 -1123. 5. Cannon CP et al. Circulation 1998; 98: 2805 -2814. 6. ASSENT-2 investigators. Lancet 1999; 354: 716 -722.

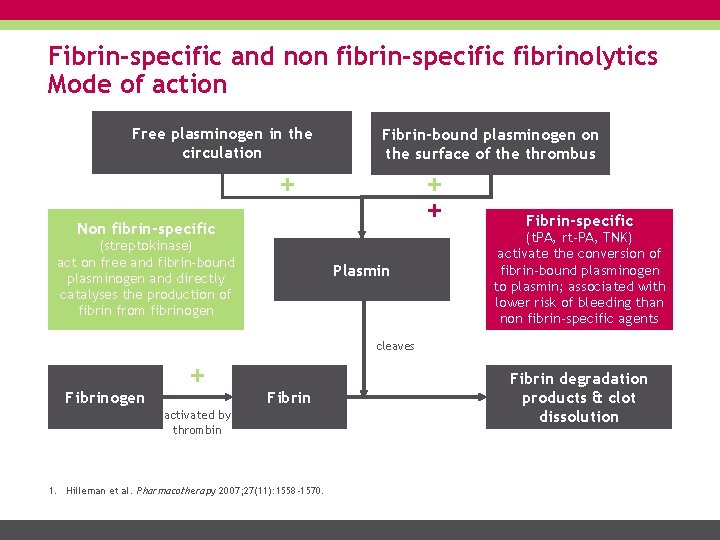

Fibrin-specific and non fibrin-specific fibrinolytics Mode of action Free plasminogen in the circulation Fibrin-bound plasminogen on the surface of the thrombus + + + Non fibrin-specific (streptokinase) act on free and fibrin-bound plasminogen and directly catalyses the production of fibrin from fibrinogen Plasmin Fibrin-specific (t. PA, rt-PA, TNK) activate the conversion of fibrin-bound plasminogen to plasmin; associated with lower risk of bleeding than non fibrin-specific agents cleaves Fibrinogen + Fibrin activated by thrombin 1. Hilleman et al. Pharmacotherapy 2007; 27(11): 1558 -1570. Fibrin degradation products & clot dissolution

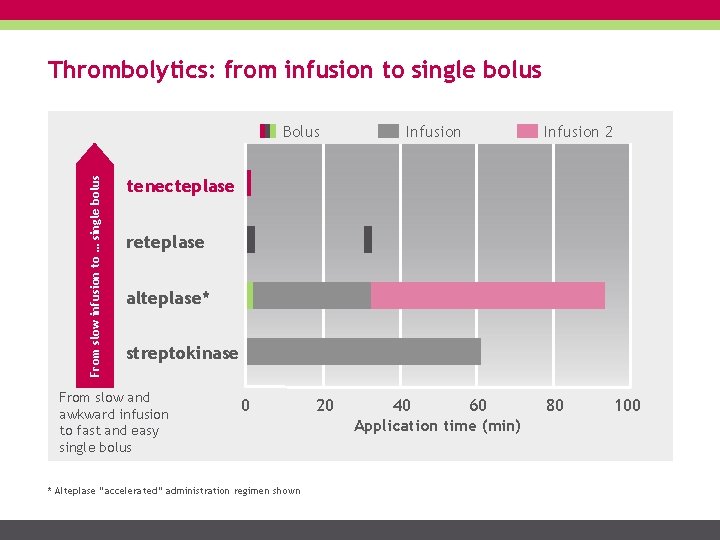

Thrombolytics: from infusion to single bolus From slow infusion to … single bolus Bolus Infusion 2 tenecteplase reteplase alteplase* streptokinase From slow and awkward infusion to fast and easy single bolus 0 * Alteplase “accelerated” administration regimen shown 20 40 60 Application time (min) 80 100

Comparison alteplase-reteplase-tenecteplase Characteristic Alteplase (rt-PA) Reteplase (r. PA) Tenecteplase (TNK-t. PA) Immunogenicity No No No Direct ++ + +++ 4 -6 min 18 min 20 min 15 mg bolus plus 90 min infusion up to 85 mg 10+10 MU double bolus 30 min apart ± 0. 5 mg/kg single bolus over approx. 10 seconds Low* 80 -fold higher than rt-PA No (recombinant version) Yes Plasminogen activation Fibrin specificity Plasma half-life Dose PAI-1 resistance Genetic alteration to native t. PA Adapted from Ross. Clin Cardiol 1999; 22: 165 -171. * Reteplase resistance described as “Comparable to Alteplase” in Nordt. Heart 2003; 89: 1358 -1362.

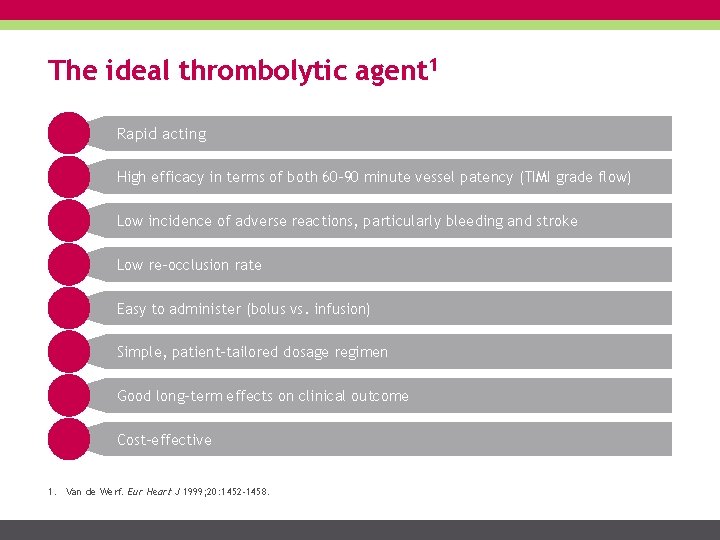

The ideal thrombolytic agent 1 Rapid acting High efficacy in terms of both 60 -90 minute vessel patency (TIMI grade flow) Low incidence of adverse reactions, particularly bleeding and stroke Low re-occlusion rate Easy to administer (bolus vs. infusion) Simple, patient-tailored dosage regimen Good long-term effects on clinical outcome Cost-effective 1. Van de Werf. Eur Heart J 1999; 20: 1452 -1458.

Tenecteplase: structure 1 ‘Finger’ 2 Growth Factor 3 ‘Kringle 1’ 4 ‘Kringle 2’ 5 Protease • Greater fibrin specificity than alteplase • Longer plasma half-life than alteplase (20 minutes vs 4 -6 minutes) • Higher resistance to PAI-1 than alteplase Metalyse®. Summary of Product Characteristics, 2014.

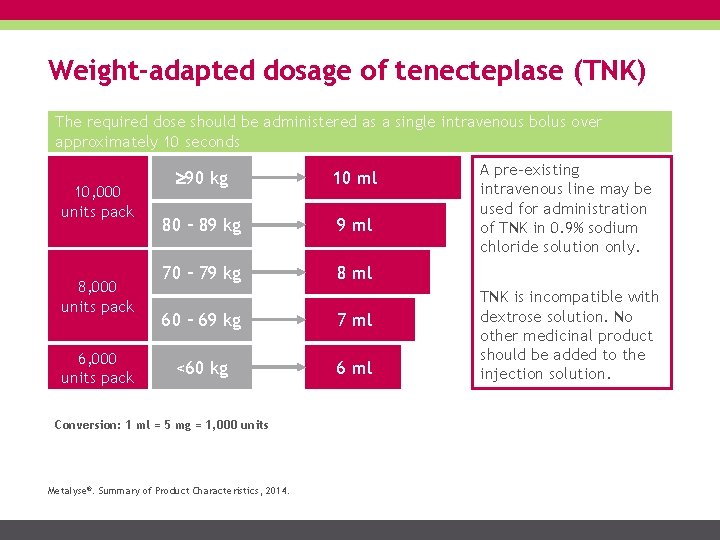

Weight-adapted dosage of tenecteplase (TNK) The required dose should be administered as a single intravenous bolus over approximately 10 seconds 10, 000 units pack 8, 000 units pack 6, 000 units pack 90 kg 10 ml 80 – 89 kg 9 ml 70 – 79 kg 8 ml 60 – 69 kg 7 ml <60 kg 6 ml Conversion: 1 ml = 5 mg = 1, 000 units Metalyse®. Summary of Product Characteristics, 2014. A pre-existing intravenous line may be used for administration of TNK in 0. 9% sodium chloride solution only. TNK is incompatible with dextrose solution. No other medicinal product should be added to the injection solution.

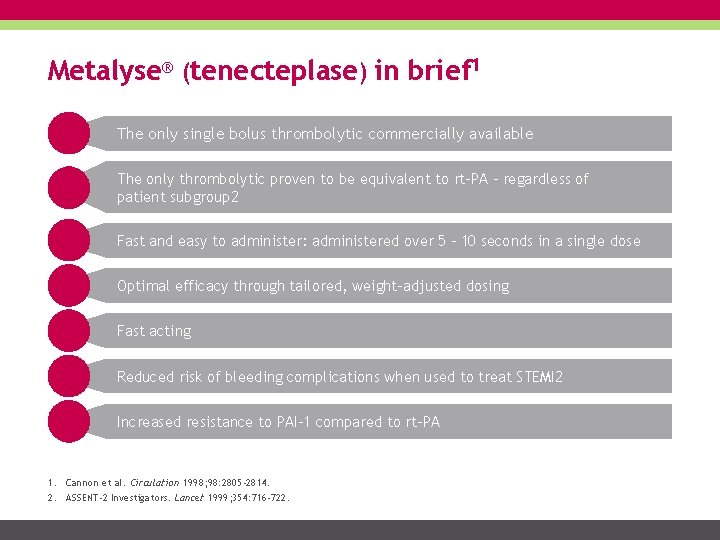

Metalyse® (tenecteplase) in brief 1 The only single bolus thrombolytic commercially available The only thrombolytic proven to be equivalent to rt-PA – regardless of patient subgroup 2 Fast and easy to administer: administered over 5 – 10 seconds in a single dose Optimal efficacy through tailored, weight-adjusted dosing Fast acting Reduced risk of bleeding complications when used to treat STEMI 2 Increased resistance to PAI-1 compared to rt-PA 1. Cannon et al. Circulation 1998; 98: 2805 -2814. 2. ASSENT-2 Investigators. Lancet 1999; 354: 716 -722.

Clinical studies Importance of time Treatment strategies & guidelines STEMI networks Fibrinolytic agents Clinical studies Registries Take home points Metalyse® prescribing information

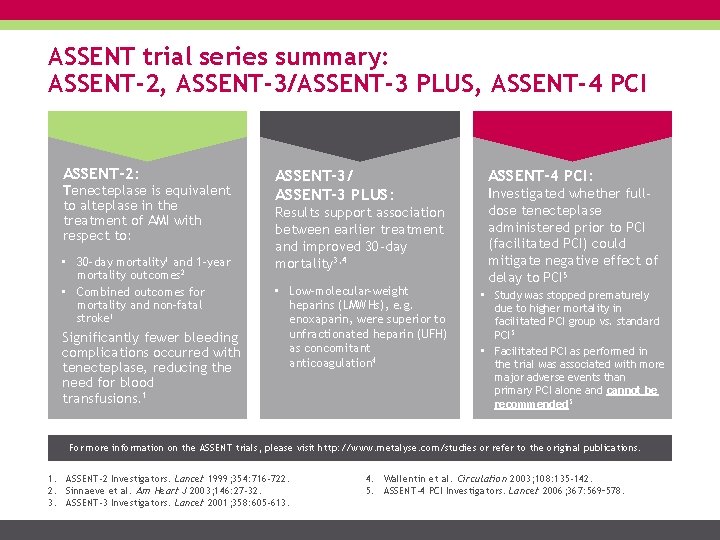

ASSENT trial series summary: ASSENT-2, ASSENT-3/ASSENT-3 PLUS, ASSENT-4 PCI ASSENT-2: Tenecteplase is equivalent to alteplase in the treatment of AMI with respect to: • 30 -day mortality 1 and 1 -year mortality outcomes 2 • Combined outcomes for mortality and non-fatal stroke 1 Significantly fewer bleeding complications occurred with tenecteplase, reducing the need for blood transfusions. 1 ASSENT-3/ ASSENT-3 PLUS: Results support association between earlier treatment and improved 30 -day mortality 3, 4 • Low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs), e. g. enoxaparin, were superior to unfractionated heparin (UFH) as concomitant anticoagulation 4 ASSENT-4 PCI: Investigated whether fulldose tenecteplase administered prior to PCI (facilitated PCI) could mitigate negative effect of delay to PCI 5 • Study was stopped prematurely due to higher mortality in facilitated PCI group vs. standard PCI 5 • Facilitated PCI as performed in the trial was associated with more major adverse events than primary PCI alone and cannot be recommended 5 For more information on the ASSENT trials, please visit http: //www. metalyse. com/studies or refer to the original publications. 1. ASSENT-2 Investigators. Lancet 1999; 354: 716 -722. 2. Sinnaeve et al. Am Heart J 2003; 146: 27 -32. 3. ASSENT-3 Investigators. Lancet 2001; 358: 605 -613. 4. Wallentin et al. Circulation 2003; 108: 135 -142. 5. ASSENT-4 PCI Investigators. Lancet 2006; 367: 569– 578.

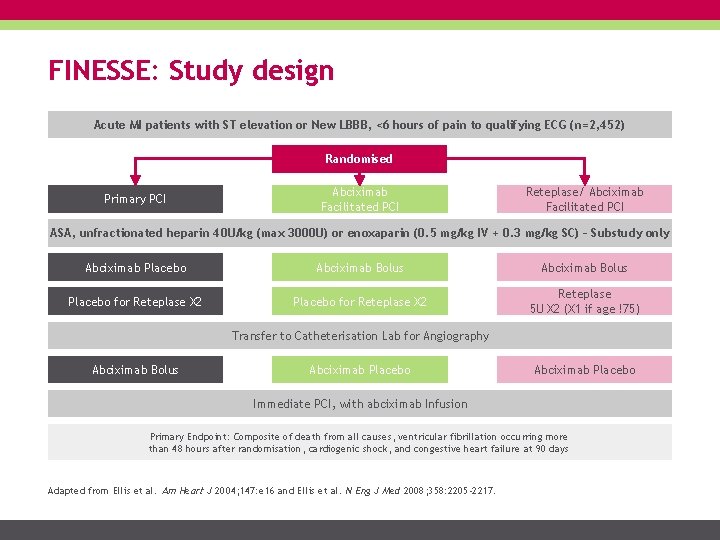

FINESSE: Study design Acute MI patients with ST elevation or New LBBB, <6 hours of pain to qualifying ECG (n=2, 452) Randomised Primary PCI Abciximab Facilitated PCI Reteplase/ Abciximab Facilitated PCI ASA, unfractionated heparin 40 U/kg (max 3000 U) or enoxaparin (0. 5 mg/kg IV + 0. 3 mg/kg SC) – Substudy only Abciximab Placebo Abciximab Bolus Placebo for Reteplase X 2 Reteplase 5 U X 2 (X 1 if age !75) Transfer to Catheterisation Lab for Angiography Abciximab Bolus Abciximab Placebo Immediate PCI, with abciximab Infusion Primary Endpoint: Composite of death from all causes, ventricular fibrillation occurring more than 48 hours after randomisation, cardiogenic shock, and congestive heart failure at 90 days Adapted from Ellis et al. Am Heart J 2004; 147: e 16 and Ellis et al. N Eng J Med 2008; 358: 2205 -2217.

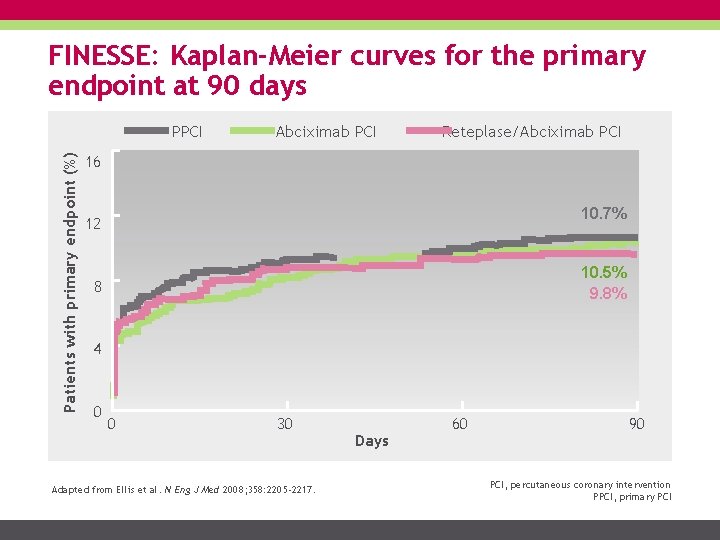

FINESSE: Kaplan-Meier curves for the primary endpoint at 90 days Patients with primary endpoint (%) PPCI Abciximab PCI Reteplase/Abciximab PCI 16 10. 7% 12 10. 5% 9. 8% 8 4 0 0 30 Adapted from Ellis et al. N Eng J Med 2008; 358: 2205 -2217. Days 60 90 PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention PPCI, primary PCI

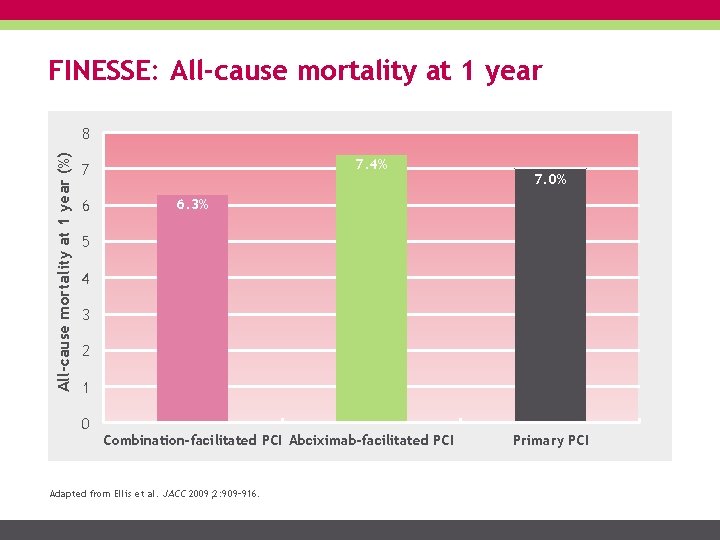

FINESSE: All-cause mortality at 1 year (%) 8 7. 4% 7 6 7. 0% 6. 3% 5 4 3 2 1 0 Combination-facilitated PCI Abciximab-facilitated PCI Adapted from Ellis et al. JACC 2009; 2: 909– 916. Primary PCI

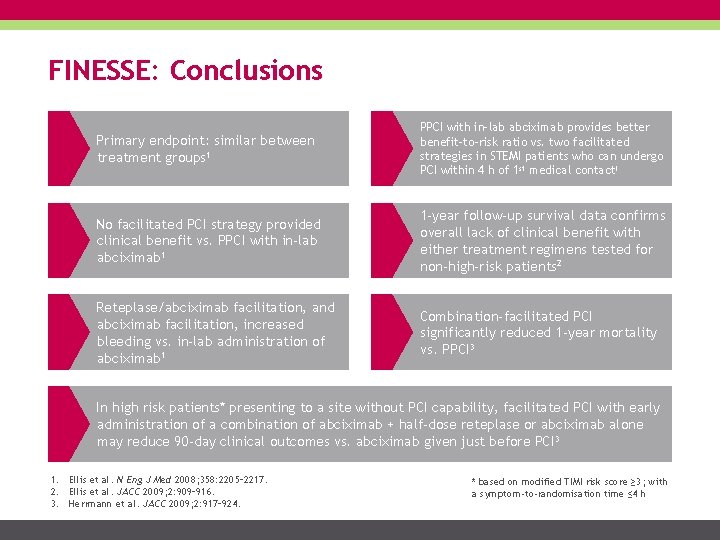

FINESSE: Conclusions Primary endpoint: similar between treatment groups 1 PPCI with in-lab abciximab provides better benefit-to-risk ratio vs. two facilitated strategies in STEMI patients who can undergo PCI within 4 h of 1 st medical contact 1 No facilitated PCI strategy provided clinical benefit vs. PPCI with in-lab abciximab 1 1 -year follow-up survival data confirms overall lack of clinical benefit with either treatment regimens tested for non-high-risk patients 2 Reteplase/abciximab facilitation, and abciximab facilitation, increased bleeding vs. in-lab administration of abciximab 1 Combination-facilitated PCI significantly reduced 1 -year mortality vs. PPCI 3 In high risk patients* presenting to a site without PCI capability, facilitated PCI with early administration of a combination of abciximab + half-dose reteplase or abciximab alone may reduce 90 -day clinical outcomes vs. abciximab given just before PCI 3 1. Ellis et al. N Eng J Med 2008; 358: 2205– 2217. 2. Ellis et al. JACC 2009; 2: 909– 916. 3. Herrmann et al. JACC 2009; 2: 917– 924. * based on modified TIMI risk score ≥ 3; with a symptom-to-randomisation time ≤ 4 h

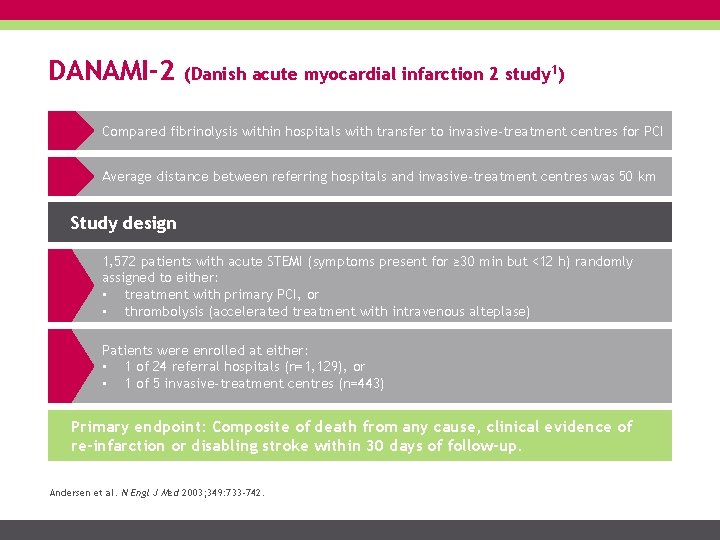

DANAMI-2 (Danish acute myocardial infarction 2 study 1) Compared fibrinolysis within hospitals with transfer to invasive-treatment centres for PCI Average distance between referring hospitals and invasive-treatment centres was 50 km Study design 1, 572 patients with acute STEMI (symptoms present for ≥ 30 min but <12 h) randomly assigned to either: • treatment with primary PCI, or • thrombolysis (accelerated treatment with intravenous alteplase) Patients were enrolled at either: • 1 of 24 referral hospitals (n=1, 129), or • 1 of 5 invasive-treatment centres (n=443) Primary endpoint: Composite of death from any cause, clinical evidence of re-infarction or disabling stroke within 30 days of follow-up. Andersen et al. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 733 -742.

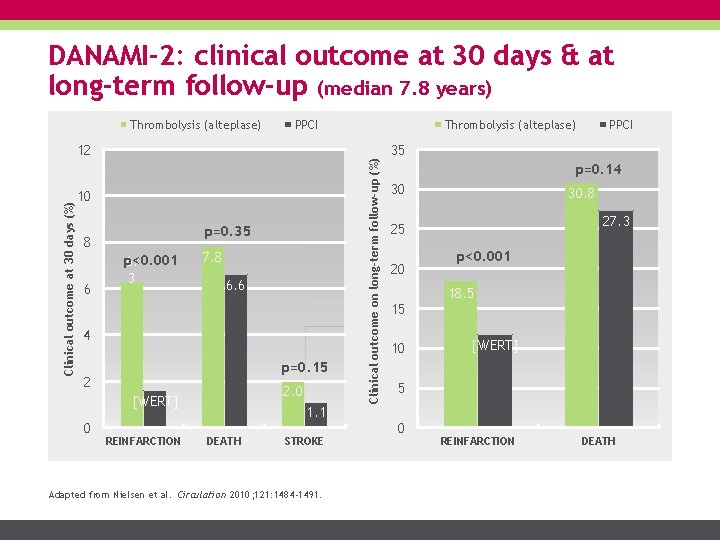

DANAMI-2: clinical outcome at 30 days & at long-term follow-up (median 7. 8 years) PPCI Clinical outcome at 30 days (%) 12 10 p=0. 35 8 6 p<0. 001 6. 3 7. 8 6. 6 4 p=0. 15 2 2. 0 [WERT] 0 REINFARCTION 1. 1 DEATH STROKE Adapted from Nielsen et al. Circulation 2010; 121: 1484 -1491. Thrombolysis (alteplase) Clinical outcome on long-term follow-up (%) Thrombolysis (alteplase) PPCI 35 p=0. 14 30 30. 8 27. 3 25 20 15 10 p<0. 001 18. 5 [WERT] 5 0 REINFARCTION DEATH

DANAMI-2: Conclusions Clinical benefit of PPCI over fibrinolysis was seen at 30 days and at long-term follow-up, largely due to a reduction in the risk of re-infarction If transfer of patient to an invasive-treatment centre can be completed within 2 h, PPCI is superior to on-site fibrinolysis Nielsen et al. Circulation 2010; 121: 1484 -1491.

Registries Importance of time Treatment strategies & guidelines STEMI networks Fibrinolytic agents Clinical studies Registries Take home points Metalyse® prescribing information

The importance of registries Prospective registries are a vital component of a STEMI network, and facilitate monitoring of outcomes and subsequent improvements 1 Data from prospective registries has led to changes in STEMI practice, for example: • Registry and post-hoc analyses suggested benefit of adding glycoprotein IIb/IIIa-inhibitors (GPIs) pre-hospital en route to the cath. lab, which is now utilised by some networks 2 -4 Here, the registries for the Vienna, Minneapolis, and French (SAMU) STEMI networks are presented 1. 2. 3. 4. Huber et al. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 1526 -153. Huber et al. Eur Heart J 2010; 31: 1708– 171. Rakowski et al. Am Heart J 2007; 153: 360– 365. Rakowski et al. Am Heart J 2009; 158: 569– 575.

Vienna STEMI registry In 2002, Vienna had one catheterisation laboratory which offered a 24 -hour PPCI service on a routine basis (on-call) for patients with acute STEMI This situation was profoundly reorganised by the implementation of: 1. Central triage for STEMI patients by the Viennese Ambulance System (VAS) 2. A second catheterisation laboratory open at night (Monday to Friday) by use of a rotation principle between 4 non-academic hospitals (on weekends [Friday afternoon to Monday morning], only 1 catheterisation centre was active during this preliminary network) 3. Pre-hospital or in-hospital TT if acute PPCI was unlikely to be offered within the recommended time intervals Kalla et al. Circulation 2006; 113: 2398– 2405.

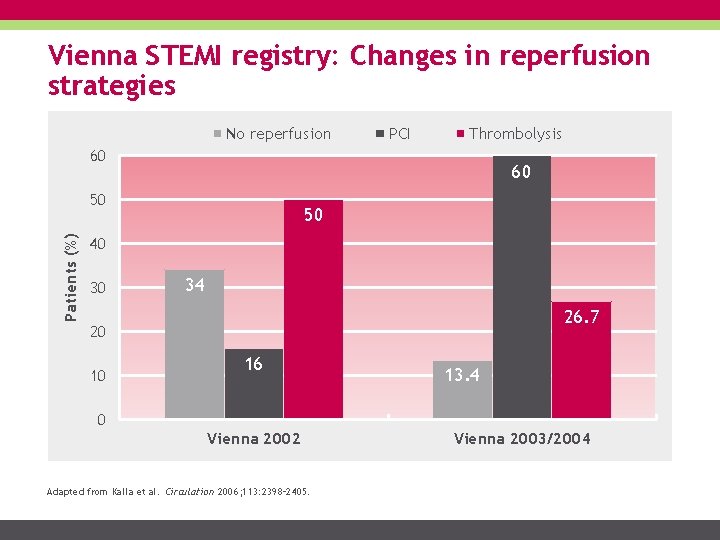

Vienna STEMI registry: Changes in reperfusion strategies No reperfusion PCI Thrombolysis 60 60 Patients (%) 50 50 40 30 34 26. 7 20 10 16 13. 4 0 Vienna 2002 Adapted from Kalla et al. Circulation 2006; 113: 2398– 2405. Vienna 2003/2004

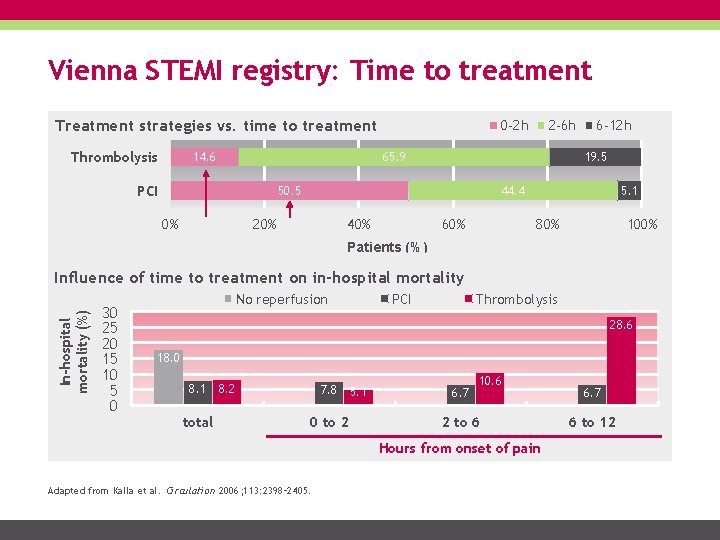

Vienna STEMI registry: Time to treatment Treatment strategies vs. time to treatment Thrombolysis 14. 6 0 -2 h 2 -6 h 65. 9 PCI 19. 5 50. 5 0% 6 -12 h 44. 4 20% 40% 60% 5. 1 80% 100% Patients (%) In-hospital mortality (%) Influence of time to treatment on in-hospital mortality 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 No reperfusion PCI Thrombolysis 28. 6 18. 0 8. 1 total 8. 2 7. 8 0 to 2 5. 1 6. 7 10. 6 2 to 6 Hours from onset of pain Adapted from Kalla et al. Circulation 2006; 113: 2398– 2405. 6. 7 6 to 12

Vienna STEMI registry: Conclusions Implementation of guideline-recommended STEMI treatment improved clinical outcomes PPCI and TT showed comparable mortality rates when initiated within 2 -3 h of onset; PPCI showed improved mortality when initiated >3 and <12 h of acute STEMI Adapted from Kalla et al. Circulation 2006; 113: 2398– 2405.

Minneapolis STEMI registry In rural settings, direct transfer of patients STEMI patients for PCI is often subject to prolonged delays This prospective study, conducted in Minneapolis, assessed the safety and efficacy of a pharmaco-invasive reperfusion strategy with half-dose fibrinolytic and direct transfer for immediate PCI compared with PPCI Larson et al. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 1232 -1240.

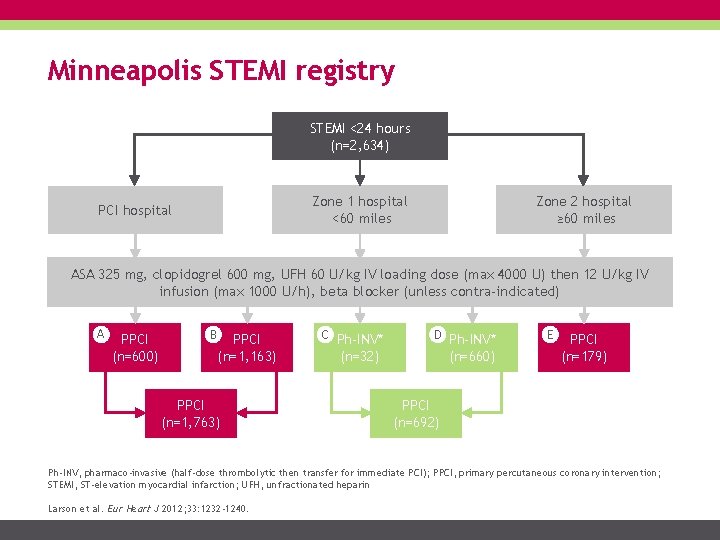

Minneapolis STEMI registry STEMI <24 hours (n=2, 634) Zone 2 hospital ≥ 60 miles Zone 1 hospital <60 miles PCI hospital ASA 325 mg, clopidogrel 600 mg, UFH 60 U/kg IV loading dose (max 4000 U) then 12 U/kg IV infusion (max 1000 U/h), beta blocker (unless contra-indicated) A PPCI (n=600) B PPCI (n=1, 163) PPCI (n=1, 763) C Ph-INV* D Ph-INV* (n=32) (n=660) E PPCI (n=179) PPCI (n=692) Ph-INV, pharmaco-invasive (half-dose thrombolytic then transfer for immediate PCI); PPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; UFH, unfractionated heparin Larson et al. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 1232 -1240.

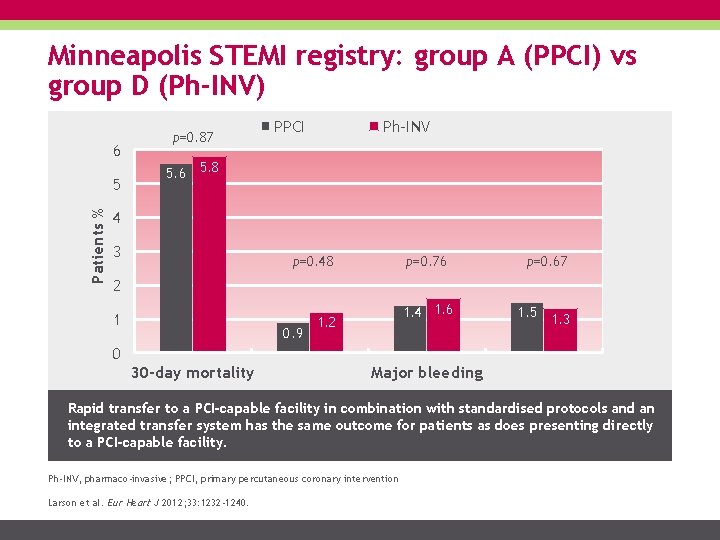

Minneapolis STEMI registry: group A (PPCI) vs group D (Ph-INV) 6 Patients % 5 p=0. 87 PPCI Ph-INV 5. 6 5. 8 4 3 p=0. 48 p=0. 76 p=0. 67 1. 4 1. 6 1. 5 1. 3 2 1 0. 9 1. 2 0 30 -day mortality Major bleeding Rapid transfer to a PCI-capable facility in combination with standardised protocols and an integrated transfer system has the same outcome for patients as does presenting directly to a PCI-capable facility. Ph-INV, pharmaco-invasive; PPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention Larson et al. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 1232 -1240.

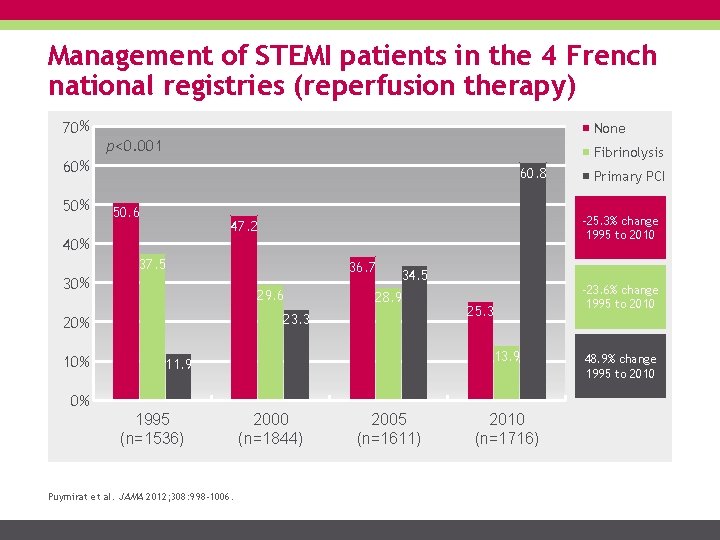

French registries of acute STEMI & NSTEMI (FAST-MI) FAST-MI 2005 and 2010 and their earlier counterparts, USIK 1995 and USIC 2000, included data from a total of 6, 707 STEMI patients These 4 registries were one-month, nationwide surveys Aim: to provide cardiologists and health authorities with national and regional data on acute MI management and outcomes every 5 years Puymirat et al. JAMA 2012; 308: 998 -1006.

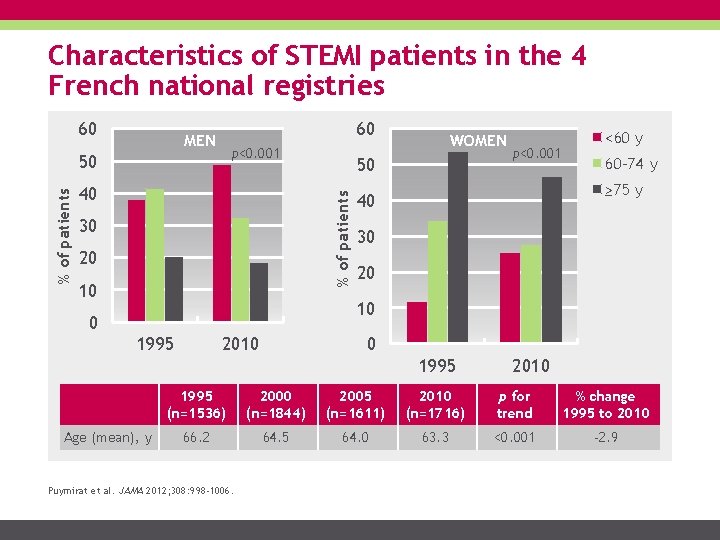

Characteristics of STEMI patients in the 4 French national registries 60 60 MEN p<0. 001 40 50 % of patients 50 30 20 10 WOMEN p<0. 001 <60 y 60 -74 y ≥ 75 y 40 30 20 10 0 1995 2010 0 1995 Age (mean), y 2010 1995 (n=1536) 2000 (n=1844) 2005 (n=1611) 2010 (n=1716) p for trend % change 1995 to 2010 66. 2 64. 5 64. 0 63. 3 <0. 001 -2. 9 Puymirat et al. JAMA 2012; 308: 998 -1006.

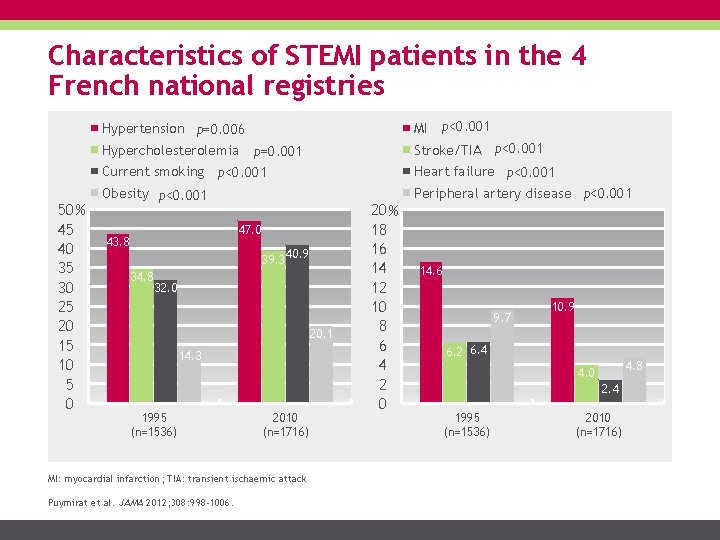

Characteristics of STEMI patients in the 4 French national registries MI p<0. 001 Hypertension p=0. 006 Hypercholesterolemia 50 % 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Stroke/TIA p<0. 001 p=0. 001 Current smoking p<0. 001 Obesity p<0. 001 47. 0 43. 8 39. 3 34. 8 40. 9 32. 0 20. 1 14. 3 1995 (n=1536) 2010 (n=1716) MI: myocardial infarction; TIA: transient ischaemic attack Puymirat et al. JAMA 2012; 308: 998 -1006. 20 % 18 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 Heart failure p<0. 001 Peripheral artery disease p<0. 001 14. 6 9. 7 10. 9 6. 2 6. 4 4. 8 4. 0 2. 4 1995 (n=1536) 2010 (n=1716)

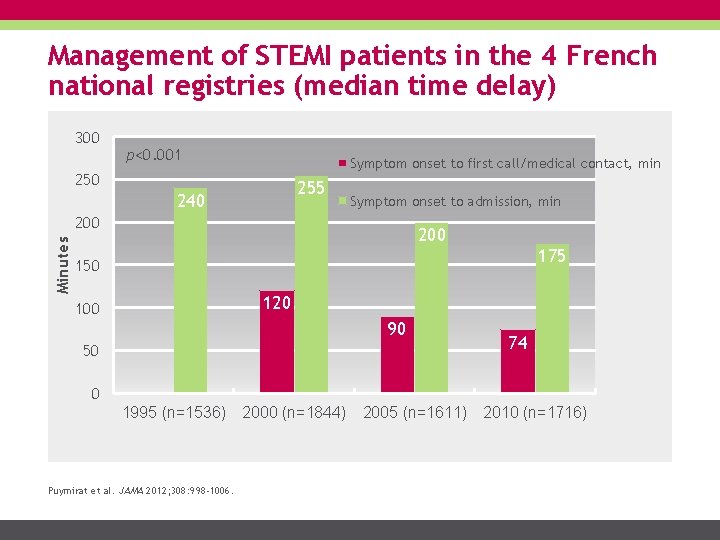

Management of STEMI patients in the 4 French national registries (median time delay) 300 p<0. 001 Symptom onset to first call/medical contact, min 250 255 240 Symptom onset to admission, min Minutes 200 175 150 120 100 90 50 74 0 1995 (n=1536) Puymirat et al. JAMA 2012; 308: 998 -1006. 2000 (n=1844) 2005 (n=1611) 2010 (n=1716)

Management of STEMI patients in the 4 French national registries (reperfusion therapy) 70 % None p<0. 001 Fibrinolysis 60 % 50 % 60. 8 50. 6 -25. 3% change 1995 to 2010 47. 2 40 % 37. 5 30 % 10 % 36. 7 29. 6 34. 5 28. 9 23. 3 20 % 25. 3 13. 9 11. 9 0% 1995 (n=1536) Puymirat et al. JAMA 2012; 308: 998 -1006. Primary PCI 2000 (n=1844) 2005 (n=1611) 2010 (n=1716) -23. 6% change 1995 to 2010 48. 9% change 1995 to 2010

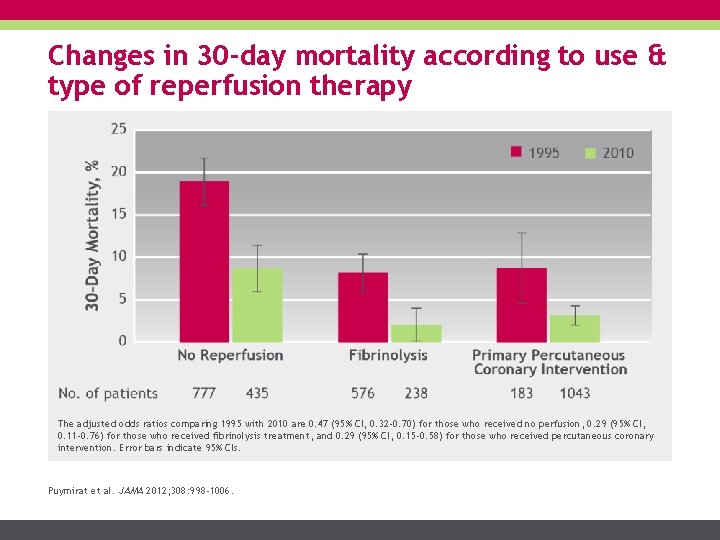

Changes in 30 -day mortality according to use & type of reperfusion therapy The adjusted odds ratios comparing 1995 with 2010 are 0. 47 (95% CI, 0. 32 -0. 70) for those who received no perfusion, 0. 29 (95% CI, 0. 11 -0. 76) for those who received fibrinolysis treatment, and 0. 29 (95% CI, 0. 15 -0. 58) for those who received percutaneous coronary intervention. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. Puymirat et al. JAMA 2012; 308: 998 -1006.

Improving treatments and STEMI care has a huge impact on mortality over the years Cumulative 6 -month mortality in patients with STEMI by year of FAST-MI survey 1 20 STEMI 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 % death 15 10 5 Permission granted by Copyright Clearance Centre’s Copyright © 2018 Puymirat et al. Circulation 2017; 136(20): 1908 -1919. 0 0 30 60 90 120 150 180 Days FAST-MI data indicated that in patients with STEMI, 6 -month mortality after acute myocardial infarction decreased considerably over the past 20 years. 1 Puymirat et al. Circulation 2017; 136(20): 1908 -1919.

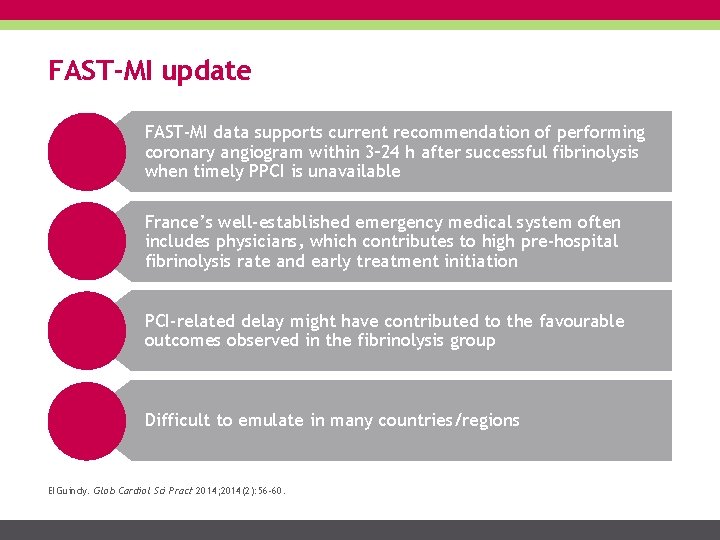

FAST-MI update FAST-MI data supports current recommendation of performing coronary angiogram within 3– 24 h after successful fibrinolysis when timely PPCI is unavailable France’s well-established emergency medical system often includes physicians, which contributes to high pre-hospital fibrinolysis rate and early treatment initiation PCI-related delay might have contributed to the favourable outcomes observed in the fibrinolysis group Difficult to emulate in many countries/regions El. Guindy. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract 2014; 2014(2): 56 -60.

Take home points Importance of time Treatment strategies & guidelines STEMI networks Fibrinolytic agents Clinical studies Registries Take home points Metalyse® prescribing information

Take home points STEMI is a time-critical medical emergency: clinical outcomes improve with reduced time to reperfusion. Every effort should be made to reduce ischaemic time. Implementation of STEMI networks is guideline-recommended and has been shown in studies and registries to reduce delays in reperfusion strategies and improve clinical outcomes. A pharmaco-invasive strategy is recommended whenever PPCI cannot be performed within recommended timelines (<120 min), and may be followed by transfer for angiography and mechanical intervention if indicated. PPCI is considered the gold-standard of care if performed ≤ 2 h of FMC (first medical contact).

Metalyse® prescribing information Importance of time Treatment strategies & guidelines STEMI networks Fibrinolytic agents Clinical studies Registries Take home points Metalyse® prescribing information

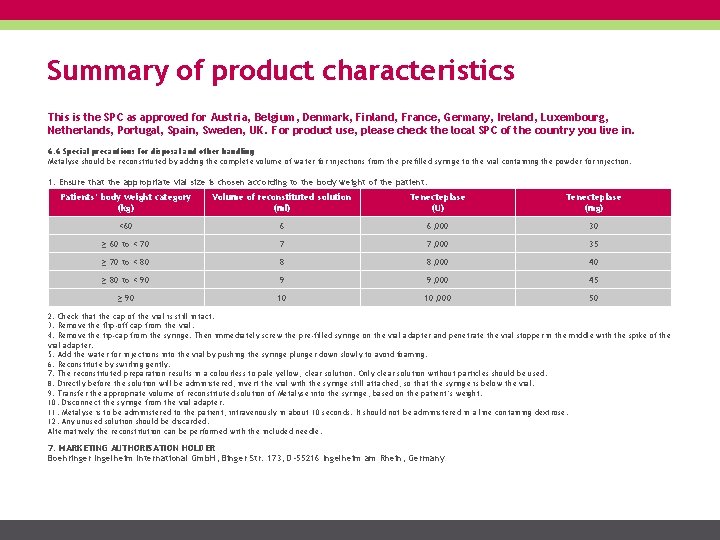

Summary of product characteristics This is the SPC as approved for Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, UK. For product use, please check the local SPC of the country you live in. 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Metalyse® Powder and solvent for solution for injection 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION 1 vial contains: 6, 000 units (30 mg) tenecteplase or 8, 000 units (40 mg) tenecteplase or 10, 000 units (50 mg) tenecteplase, respectively. 1 prefilled syringe contains: 6 ml water for injections or 8 ml water for injections or 10 ml water for injections, respectively. The reconstituted solution contains 1, 000 units (5 mg) tenecteplase per ml. Potency of tenecteplase is expressed in units (U) by using a reference standard which is specific for tenecteplase and is not comparable with units used for other thrombolytic agents. Tenecteplase is a fibrin-specific plasminogen activator produced in a Chinese hamster ovary cell line by recombinant DNA technology. For a full list of excipients, see section 6. 1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Powder and solvent for solution for injection. The powder is white to off-white. The reconstituted preparation is a clear and colourless to slightly yellow solution. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4. 1 Therapeutic indications: Metalyse is indicated in adults for the thrombolytic treatment of suspected myocardial infarction with persistent ST elevation or recent left Bundle Branch Block within 6 hours after the onset of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) symptoms.

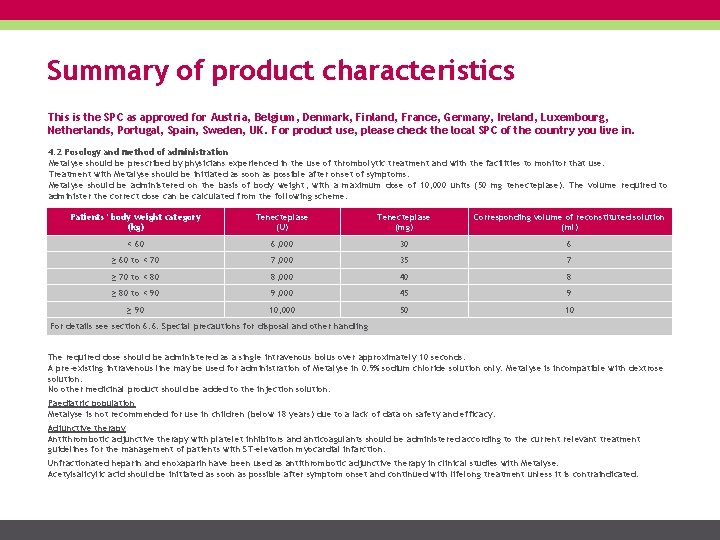

Summary of product characteristics This is the SPC as approved for Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, UK. For product use, please check the local SPC of the country you live in. 4. 2 Posology and method of administration Metalyse should be prescribed by physicians experienced in the use of thrombolytic treatment and with the facilities to monitor that use. Treatment with Metalyse should be initiated as soon as possible after onset of symptoms. Metalyse should be administered on the basis of body weight, with a maximum dose of 10, 000 units (50 mg tenecteplase). The volume required to administer the correct dose can be calculated from the following scheme: Patients’ body weight category (kg) Tenecteplase (U) Tenecteplase (mg) Corresponding volume of reconstituted solution (ml) < 60 6, 000 30 6 ≥ 60 to < 70 7, 000 35 7 ≥ 70 to < 80 8, 000 40 8 ≥ 80 to < 90 9, 000 45 9 ≥ 90 10, 000 50 10 For details see section 6. 6: Special precautions for disposal and other handling The required dose should be administered as a single intravenous bolus over approximately 10 seconds. A pre-existing intravenous line may be used for administration of Metalyse in 0. 9% sodium chloride solution only. Metalyse is incompatible with dextrose solution. No other medicinal product should be added to the injection solution. Paediatric population Metalyse is not recommended for use in children (below 18 years) due to a lack of data on safety and efficacy. Adjunctive therapy Antithrombotic adjunctive therapy with platelet inhibitors and anticoagulants should be administered according to the current relevant treatment guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Unfractionated heparin and enoxaparin have been used as antithrombotic adjunctive therapy in clinical studies with Metalyse. Acetylsalicylic acid should be initiated as soon as possible after symptom onset and continued with lifelong treatment unless it is contraindicated.

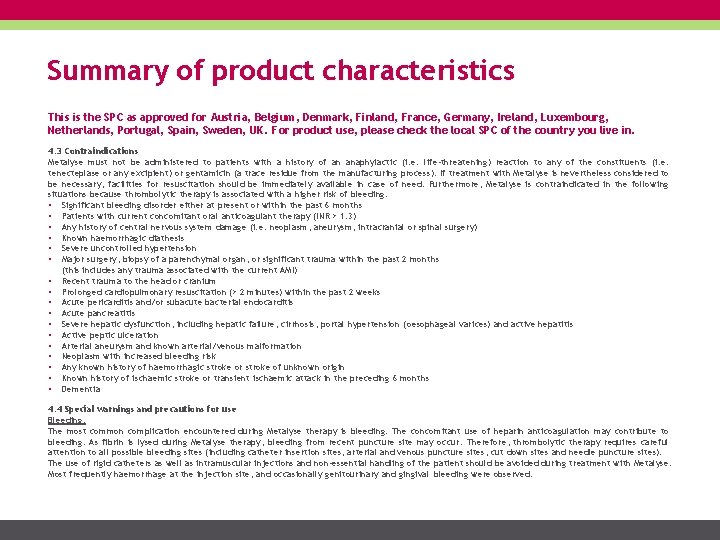

Summary of product characteristics This is the SPC as approved for Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, UK. For product use, please check the local SPC of the country you live in. 4. 3 Contraindications Metalyse must not be administered to patients with a history of an anaphylactic (i. e. life-threatening) reaction to any of the constituents (i. e. tenecteplase or any excipient) or gentamicin (a trace residue from the manufacturing process). If treatment with Metalyse is nevertheless considered to be necessary, facilities for resuscitation should be immediately available in case of need. Furthermore, Metalyse is contraindicated in the following situations because thrombolytic therapy is associated with a higher risk of bleeding: • Significant bleeding disorder either at present or within the past 6 months • Patients with current concomitant oral anticoagulant therapy (INR > 1. 3) • Any history of central nervous system damage (i. e. neoplasm, aneurysm, intracranial or spinal surgery) • Known haemorrhagic diathesis • Severe uncontrolled hypertension • Major surgery, biopsy of a parenchymal organ, or significant trauma within the past 2 months (this includes any trauma associated with the current AMI) • Recent trauma to the head or cranium • Prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation (> 2 minutes) within the past 2 weeks • Acute pericarditis and/or subacute bacterial endocarditis • Acute pancreatitis • Severe hepatic dysfunction, including hepatic failure, cirrhosis, portal hypertension ( oesophageal varices) and active hepatitis • Active peptic ulceration • Arterial aneurysm and known arterial/venous malformation • Neoplasm with increased bleeding risk • Any known history of haemorrhagic stroke or stroke of unknown origin • Known history of ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in the preceding 6 months • Dementia 4. 4 Special warnings and precautions for use Bleeding: The most common complication encountered during Metalyse therapy is bleeding. The concomitant use of heparin anticoagulation may contribute to bleeding. As fibrin is lysed during Metalyse therapy, bleeding from recent puncture site may occur. Therefore, thrombolytic therapy requires careful attention to all possible bleeding sites (including catheter insertion sites, arterial and venous puncture sites, cut down sites and needle puncture sites). The use of rigid catheters as well as intramuscular injections and non-essential handling of the patient should be avoided during treatment with Metalyse. Most frequently haemorrhage at the injection site, and occasionally genitourinary and gingival bleeding were observed.

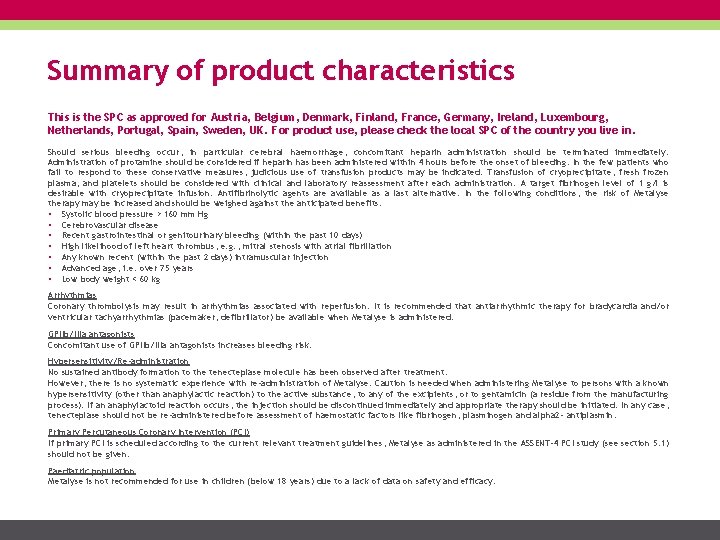

Summary of product characteristics This is the SPC as approved for Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, UK. For product use, please check the local SPC of the country you live in. Should serious bleeding occur, in particular cerebral haemorrhage, concomitant heparin administration should be terminated immediately. Administration of protamine should be considered if heparin has been administered within 4 hours before the onset of bleeding. In the few patients who fail to respond to these conservative measures, judicious use of transfusion products may be indicated. Transfusion of cryoprecipitate, fresh frozen plasma, and platelets should be considered with clinical and laboratory reassessment after each administration. A target fibrinogen level of 1 g/l is desirable with cryoprecipitate infusion. Antifibrinolytic agents are available as a last alternative. In the following conditions, the risk of Metalyse therapy may be increased and should be weighed against the anticipated benefits: • Systolic blood pressure > 160 mm Hg • Cerebrovascular disease • Recent gastrointestinal or genitourinary bleeding (within the past 10 days) • High likelihood of left heart thrombus, e. g. , mitral stenosis with atrial fibrillation • Any known recent (within the past 2 days) intramuscular injection • Advanced age, i. e. over 75 years • Low body weight < 60 kg Arrhythmias Coronary thrombolysis may result in arrhythmias associated with reperfusion. It is recommended that antiarrhythmic therapy for bradycardia and/or ventricular tachyarrhythmias (pacemaker, defibrillator) be available when Metalyse is administered. GPIIb/IIIa antagonists Concomitant use of GPIIb/IIIa antagonists increases bleeding risk. Hypersensitivity/Re-administration No sustained antibody formation to the tenecteplase molecule has been observed after treatment. However, there is no systematic experience with re-administration of Metalyse. Caution is needed when administering Metalyse to persons with a known hypersensitivity (other than anaphylactic reaction) to the active substance, to any of the excipients, or to gentamicin (a residue from the manufacturing process). If an anaphylactoid reaction occurs, the injection should be discontinued immediately and appropriate therapy should be initiated. In any case, tenecteplase should not be re-administered before assessment of haemostatic factors like fibrinogen, plasminogen and alpha 2 - antiplasmin. Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) If primary PCI is scheduled according to the current relevant treatment guidelines, Metalyse as administered in the ASSENT-4 PCI study (see section 5. 1) should not be given. Paediatric population Metalyse is not recommended for use in children (below 18 years) due to a lack of data on safety and efficacy.

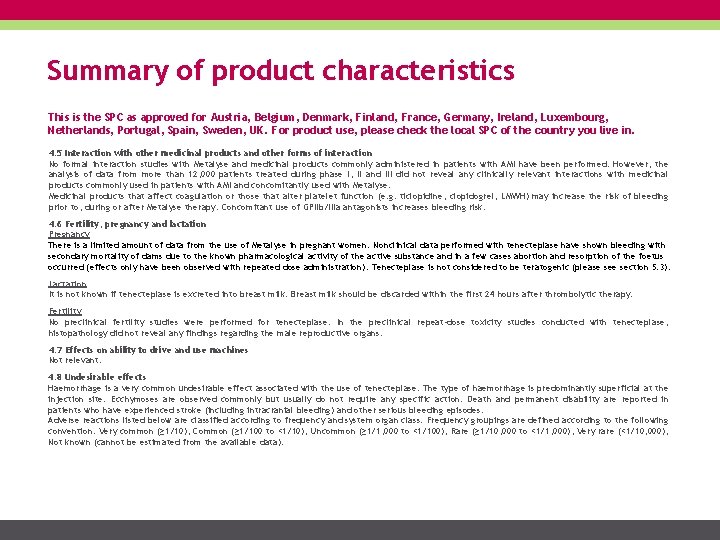

Summary of product characteristics This is the SPC as approved for Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, UK. For product use, please check the local SPC of the country you live in. 4. 5 Interaction with other medicinal products and other forms of interaction No formal interaction studies with Metalyse and medicinal products commonly administered in patients with AMI have been performed. However, the analysis of data from more than 12, 000 patients treated during phase I, II and III did not reveal any clinically relevant interactions with medicinal products commonly used in patients with AMI and concomitantly used with Metalyse. Medicinal products that affect coagulation or those that alter platelet function (e. g. ticlopidine, clopidogrel, LMWH) may increase the risk of bleeding prior to, during or after Metalyse therapy. Concomitant use of GPIIb/IIIa antagonists increases bleeding risk. 4. 6 Fertility, pregnancy and lactation Pregnancy There is a limited amount of data from the use of Metalyse in pregnant women. Nonclinical data performed with tenecteplase have shown bleeding with secondary mortality of dams due to the known pharmacological activity of the active substance and in a few cases abortion and resorption of the foetus occurred (effects only have been observed with repeated dose administration). Tenecteplase is not considered to be teratogenic (please section 5. 3). Lactation It is not known if tenecteplase is excreted into breast milk. Breast milk should be discarded within the first 24 hours after thrombolytic therapy. Fertility No preclinical fertility studies were performed for tenecteplase. In the preclinical repeat-dose toxicity studies conducted with tenecteplase, histopathology did not reveal any findings regarding the male reproductive organs. 4. 7 Effects on ability to drive and use machines Not relevant. 4. 8 Undesirable effects Haemorrhage is a very common undesirable effect associated with the use of tenecteplase. The type of haemorrhage is predominantly superficial at the injection site. Ecchymoses are observed commonly but usually do not require any specific action. Death and permanent disability are reported in patients who have experienced stroke (including intracranial bleeding) and other serious bleeding episodes. Adverse reactions listed below are classified according to frequency and system organ class. Frequency groupings are defined according to the following convention: Very common (≥ 1/10), Common (≥ 1/100 to <1/10), Uncommon (≥ 1/1, 000 to <1/100), Rare (≥ 1/10, 000 to <1/1, 000), Very rare (<1/10, 000), Not known (cannot be estimated from the available data).

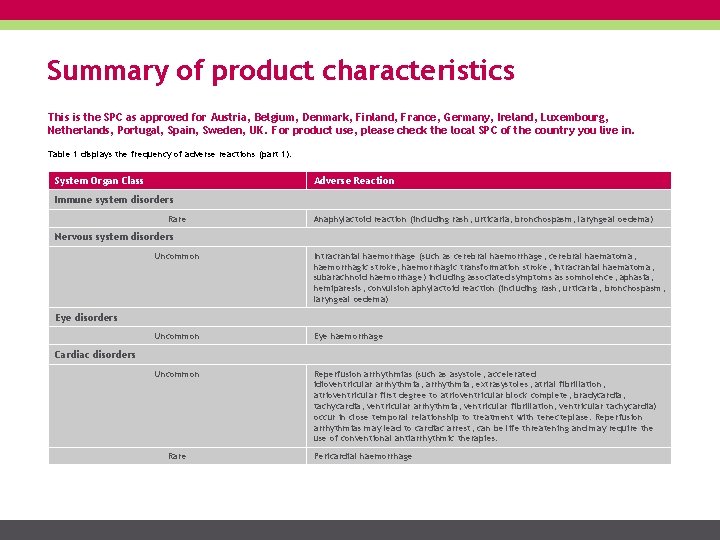

Summary of product characteristics This is the SPC as approved for Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, UK. For product use, please check the local SPC of the country you live in. Table 1 displays the frequency of adverse reactions (part 1). System Organ Class Adverse Reaction Immune system disorders Rare Anaphylactoid reaction (including rash, urticaria, bronchospasm, laryngeal oedema) Nervous system disorders Uncommon Intracranial haemorrhage (such as cerebral haemorrhage, cerebral haematoma, haemorrhagic stroke, haemorrhagic transformation stroke, intracranial haematoma, subarachnoid haemorrhage) including associated symptoms as somnolence, aphasia, hemiparesis, convulsion aphylactoid reaction (including rash, urticaria, bronchospasm, laryngeal oedema) Uncommon Eye haemorrhage Uncommon Reperfusion arrhythmias (such as asystole, accelerated idioventricular arrhythmia, extrasystoles, atrial fibrillation, atrioventricular first degree to atrioventricular block complete, bradycardia, tachycardia, ventricular arrhythmia, ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia) occur in close temporal relationship to treatment with tenecteplase. Reperfusion arrhythmias may lead to cardiac arrest, can be life threatening and may require the use of conventional antiarrhythmic therapies. Eye disorders Cardiac disorders Rare Pericardial haemorrhage

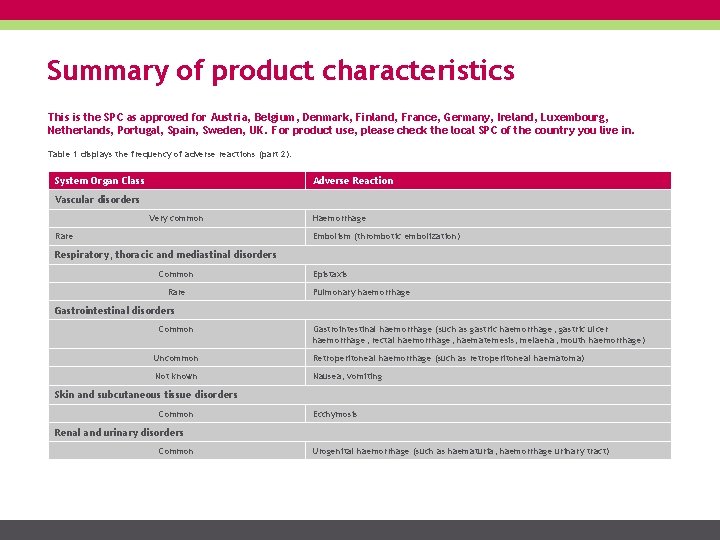

Summary of product characteristics This is the SPC as approved for Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, UK. For product use, please check the local SPC of the country you live in. Table 1 displays the frequency of adverse reactions (part 2). System Organ Class Adverse Reaction Vascular disorders Very common Rare Haemorrhage Embolism (thrombotic embolization) Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders Common Rare Epistaxis Pulmonary haemorrhage Gastrointestinal disorders Common Gastrointestinal haemorrhage (such as gastric haemorrhage, gastric ulcer haemorrhage, rectal haemorrhage, haematemesis, melaena, mouth haemorrhage) Uncommon Retroperitoneal haemorrhage (such as retroperitoneal haematoma) Not known Nausea, vomiting Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders Common Ecchymosis Renal and urinary disorders Common Urogenital haemorrhage (such as haematuria, haemorrhage urinary tract)

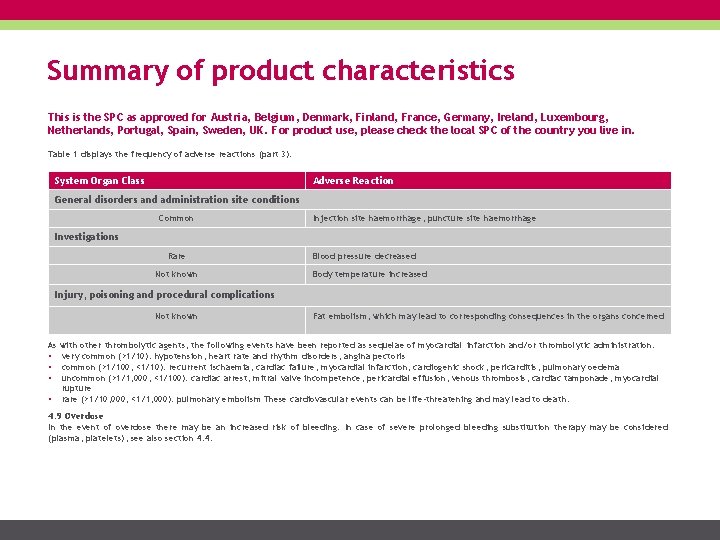

Summary of product characteristics This is the SPC as approved for Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, UK. For product use, please check the local SPC of the country you live in. Table 1 displays the frequency of adverse reactions (part 3). System Organ Class Adverse Reaction General disorders and administration site conditions Common Injection site haemorrhage, puncture site haemorrhage Investigations Rare Not known Blood pressure decreased Body temperature increased Injury, poisoning and procedural complications Not known Fat embolism, which may lead to corresponding consequences in the organs concerned As with other thrombolytic agents, the following events have been reported as sequelae of myocardial infarction and/or thrombolytic administration: • very common (>1/10): hypotension, heart rate and rhythm disorders, angina pectoris • common (>1/100, <1/10): recurrent ischaemia, cardiac failure, myocardial infarction, cardiogenic shock, pericarditis, pulmonary oedema • uncommon (>1/1, 000, <1/100): cardiac arrest, mitral valve incompetence, pericardial effusion, venous thrombosis, cardiac tamponade, myocardial rupture • rare (>1/10, 000, <1/1, 000): pulmonary embolism These cardiovascular events can be life-threatening and may lead to death. 4. 9 Overdose In the event of overdose there may be an increased risk of bleeding. In case of severe prolonged bleeding substitution therapy may be considered (plasma, platelets), see also section 4. 4.

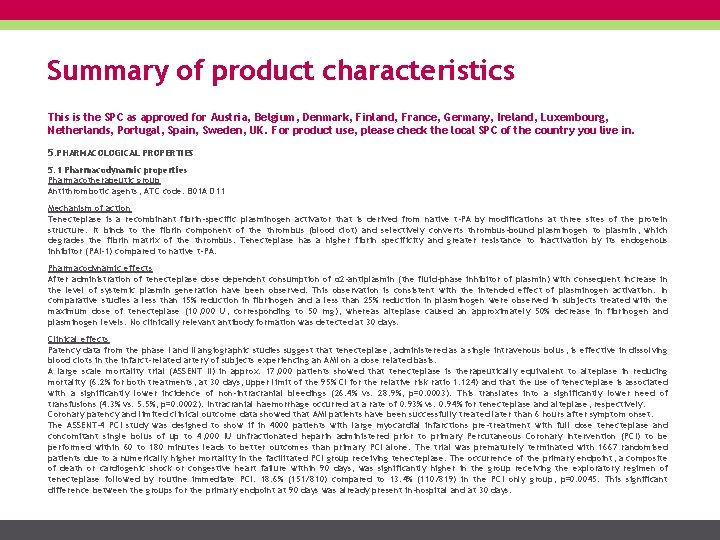

Summary of product characteristics This is the SPC as approved for Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, UK. For product use, please check the local SPC of the country you live in. 5. PHARMACOLOGICAL PROPERTIES 5. 1 Pharmacodynamic properties Pharmacotherapeutic group Antithrombotic agents, ATC code: B 01 A D 11 Mechanism of action Tenecteplase is a recombinant fibrin-specific plasminogen activator that is derived from native t-PA by modifications at three sites of the protein structure. It binds to the fibrin component of the thrombus (blood clot) and selectively converts thrombus-bound plasminogen to plasmin, which degrades the fibrin matrix of the thrombus. Tenecteplase has a higher fibrin specificity and greater resistance to inactivation by its endogenous inhibitor (PAI-1) compared to native t-PA. Pharmacodynamic effects After administration of tenecteplase dose dependent consumption of α 2 -antiplasmin (the fluid-phase inhibitor of plasmin) with consequent increase in the level of systemic plasmin generation have been observed. This observation is consistent with the intended effect of plasminogen activation. In comparative studies a less than 15% reduction in fibrinogen and a less than 25% reduction in plasminogen were observed in subjects treated with the maximum dose of tenecteplase (10, 000 U, corresponding to 50 mg), whereas alteplase caused an approximately 50% decrease in fibrinogen and plasminogen levels. No clinically relevant antibody formation was detected at 30 days. Clinical effects Patency data from the phase I and II angiographic studies suggest that tenecteplase, administered as a single intravenous bolus, is effective in dissolving blood clots in the infarct-related artery of subjects experiencing an AMI on a dose related basis. A large scale mortality trial (ASSENT II) in approx. 17, 000 patients showed that tenecteplase is therapeutically equivalent to alteplase in reducing mortality (6. 2% for both treatments, at 30 days, upper limit of the 95% CI for the relative risk ratio 1. 124) and that the use of tenecteplase is associated with a significantly lower incidence of non-intracranial bleedings (26. 4% vs. 28. 9%, p=0. 0003). This translates into a significantly lower need of transfusions (4. 3% vs. 5. 5%, p=0. 0002). Intracranial haemorrhage occurred at a rate of 0. 93% vs. 0. 94% for tenecteplase and alteplase, respectively. Coronary patency and limited clinical outcome data showed that AMI patients have been successfully treated later than 6 hours after symptom onset. The ASSENT-4 PCI study was designed to show if in 4000 patients with large myocardial infarctions pre-treatment with full dose tenecteplase and concomitant single bolus of up to 4, 000 IU unfractionated heparin administered prior to primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) to be performed within 60 to 180 minutes leads to better outcomes than primary PCI alone. The trial was prematurely terminated with 1667 randomised patients due to a numerically higher mortality in the facilitated PCI group receiving tenecteplase. The occurrence of the primary endpoint, a composite of death or cardiogenic shock or congestive heart failure within 90 days, was significantly higher in the group receiving the exploratory regimen of tenecteplase followed by routine immediate PCI: 18. 6% (151/810) compared to 13. 4% (110/819) in the PCI only group, p=0. 0045. This significant difference between the groups for the primary endpoint at 90 days was already present in-hospital and at 30 days.

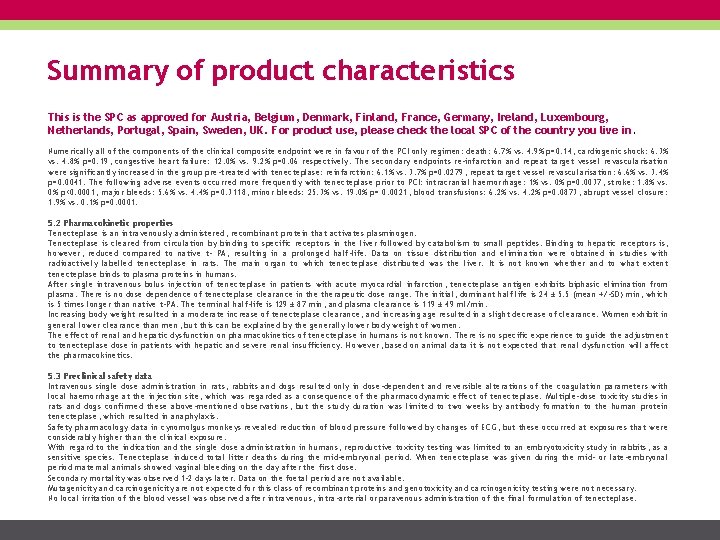

Summary of product characteristics This is the SPC as approved for Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, UK. For product use, please check the local SPC of the country you live in. Numerically all of the components of the clinical composite endpoint were in favour of the PCI only regimen: death: 6. 7% vs. 4. 9% p=0. 14; cardiogenic shock: 6. 3% vs. 4. 8% p=0. 19; congestive heart failure: 12. 0% vs. 9. 2% p=0. 06 respectively. The secondary endpoints re-infarction and repeat target vessel revascularisation were significantly increased in the group pre-treated with tenecteplase: reinfarction: 6. 1% vs. 3. 7% p=0. 0279; repeat target vessel revascularisation: 6. 6% vs. 3. 4% p=0. 0041. The following adverse events occurred more frequently with tenecteplase prior to PCI: intracranial haemorrhage: 1% vs. 0% p=0. 0037; stroke: 1. 8% vs. 0% p<0. 0001; major bleeds: 5. 6% vs. 4. 4% p=0. 3118; minor bleeds: 25. 3% vs. 19. 0% p= 0. 0021; blood transfusions: 6. 2% vs. 4. 2% p=0. 0873; abrupt vessel closure: 1. 9% vs. 0. 1% p=0. 0001. 5. 2 Pharmacokinetic properties Tenecteplase is an intravenously administered, recombinant protein that activates plasminogen. Tenecteplase is cleared from circulation by binding to specific receptors in the liver followed by catabolism to small peptides. Binding to hepatic receptors is, however, reduced compared to native t- PA, resulting in a prolonged half-life. Data on tissue distribution and elimination were obtained in studies with radioactively labelled tenecteplase in rats. The main organ to which tenecteplase distributed was the liver. It is not known whether and to what extent tenecteplase binds to plasma proteins in humans. After single intravenous bolus injection of tenecteplase in patients with acute myocardial infarction, tenecteplase antigen exhibits biphasic elimination from plasma. There is no dose dependence of tenecteplase clearance in therapeutic dose range. The initial, dominant half life is 24 ± 5. 5 (mean +/-SD) min, which is 5 times longer than native t-PA. The terminal half-life is 129 ± 87 min, and plasma clearance is 119 ± 49 ml/min. Increasing body weight resulted in a moderate increase of tenecteplase clearance, and increasing age resulted in a slight decrease of clearance. Women exhibit in general lower clearance than men, but this can be explained by the generally lower body weight of women. The effect of renal and hepatic dysfunction on pharmacokinetics of tenecteplase in humans is not known. There is no specific experience to guide the adjustment to tenecteplase dose in patients with hepatic and severe renal insufficiency. However, based on animal data it is not expected that renal dysfunction will affect the pharmacokinetics. 5. 3 Preclinical safety data Intravenous single dose administration in rats, rabbits and dogs resulted only in dose-dependent and reversible alterations of the coagulation parameters with local haemorrhage at the injection site, which was regarded as a consequence of the pharmacodynamic effect of tenecteplase. Multiple-dose toxicity studies in rats and dogs confirmed these above-mentioned observations, but the study duration was limited to two weeks by antibody formation to the human protein tenecteplase, which resulted in anaphylaxis. Safety pharmacology data in cynomolgus monkeys revealed reduction of blood pressure followed by changes of ECG, but these occurred at exposures that were considerably higher than the clinical exposure. With regard to the indication and the single dose administration in humans, reproductive toxicity testing was limited to an embryotoxicity study in rabbits, as a sensitive species. Tenecteplase induced total litter deaths during the mid-embryonal period. When tenecteplase was given during the mid- or late-embryonal period maternal animals showed vaginal bleeding on the day after the first dose. Secondary mortality was observed 1 -2 days later. Data on the foetal period are not available. Mutagenicity and carcinogenicity are not expected for this class of recombinant proteins and genotoxicity and carcinogenicity testing were not necessary. No local irritation of the blood vessel was observed after intravenous, intra-arterial or paravenous administration of the final formulation of tenecteplase.

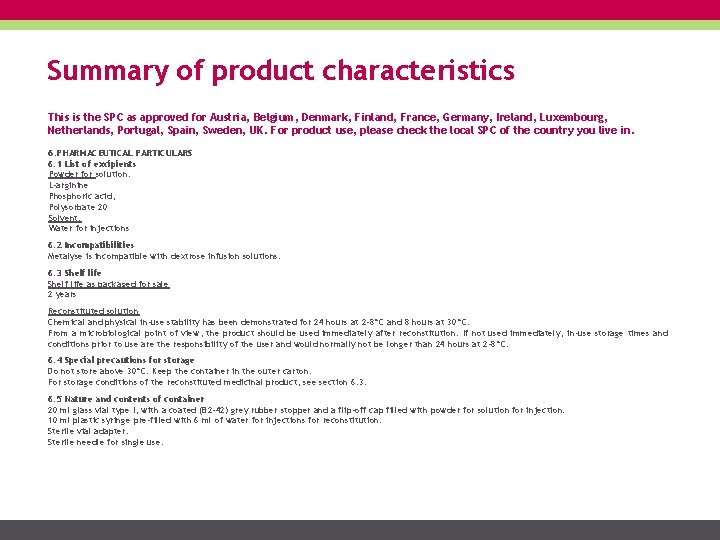

Summary of product characteristics This is the SPC as approved for Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, UK. For product use, please check the local SPC of the country you live in. 6. PHARMACEUTICAL PARTICULARS 6. 1 List of excipients Powder for solution: L-arginine Phosphoric acid, Polysorbate 20 Solvent: Water for injections 6. 2 Incompatibilities Metalyse is incompatible with dextrose infusion solutions. 6. 3 Shelf life as packaged for sale 2 years Reconstituted solution Chemical and physical in-use stability has been demonstrated for 24 hours at 2 -8°C and 8 hours at 30°C. From a microbiological point of view, the product should be used immediately after reconstitution. If not used immediately, in-use storage times and conditions prior to use are the responsibility of the user and would normally not be longer than 24 hours at 2 -8°C. 6. 4 Special precautions for storage Do not store above 30°C. Keep the container in the outer carton. For storage conditions of the reconstituted medicinal product, see section 6. 3. 6. 5 Nature and contents of container 20 ml glass vial type I, with a coated (B 2 -42) grey rubber stopper and a flip-off cap filled with powder for solution for injection. 10 ml plastic syringe pre-filled with 6 ml of water for injections for reconstitution. Sterile vial adapter. Sterile needle for single use.

Summary of product characteristics This is the SPC as approved for Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, UK. For product use, please check the local SPC of the country you live in. 6. 6 Special precautions for disposal and other handling Metalyse should be reconstituted by adding the complete volume of water for injections from the prefilled syringe to the vial containing the powder for injection. 1. Ensure that the appropriate vial size is chosen according to the body weight of the patient. Patients‘ body weight category (kg) Volume of reconstituted solution (ml) Tenecteplase (U) Tenecteplase (mg) <60 6 6, 000 30 ≥ 60 to < 70 7 7, 000 35 ≥ 70 to < 80 8 8, 000 40 ≥ 80 to < 90 9 9, 000 45 ≥ 90 10 10, 000 50 2. Check that the cap of the vial is still intact. 3. Remove the flip-off cap from the vial. 4. Remove the tip-cap from the syringe. Then immediately screw the pre-filled syringe on the vial adapter and penetrate the vial stopper in the middle with the spike of the vial adapter. 5. Add the water for injections into the vial by pushing the syringe plunger down slowly to avoid foaming. 6. Reconstitute by swirling gently. 7. The reconstituted preparation results in a colourless to pale yellow, clear solution. Only clear solution without particles should be used. 8. Directly before the solution will be administered, invert the vial with the syringe still attached, so that the syringe is below the vial. 9. Transfer the appropriate volume of reconstituted solution of Metalyse into the syringe, based on the patient’s weight. 10. Disconnect the syringe from the vial adapter. 11. Metalyse is to be administered to the patient, intravenously in about 10 seconds. It should not be administered in a line containing dextrose. 12. Any unused solution should be discarded. Alternatively the reconstitution can be performed with the included needle. 7. MARKETING AUTHORISATION HOLDER Boehringer Ingelheim International Gmb. H, Binger Str. 173, D-55216 Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany

Imprint Published by Boehringer Ingelheim International Gmb. H www. metalyse. com Realisation infill healthcare communication www. infill. com

- Slides: 71