Statistical Learning Phenomena and Processes Erik D Thiessen

- Slides: 63

Statistical Learning: Phenomena and Processes Erik D. Thiessen Department of Psychology Carnegie Mellon University

How do we get from here…

To here?

Complex systems • Language – It is unlikely/improbable that Tim will be home • Multiple aspects: acoustics, phonology, semantics, syntax • How can infants learn all of these aspects? – Acquisition is very rapid; unlike adults, infants are master communicators with 4 years

Learning • If language is learned, infants must have access to a powerful learning mechanism • One possible mechanism: statistical learning – Discovering which events predict other events in the input (Canfield and Haith, 1991) • To what extent is this useful? – Characterizing language statistics – Identifying individual differences based on SL – Understanding the mechanism of SL

Word Segmentation • Infants must find words in fluent speech • Fluent speech is smooshed togethether

“In the winter, Wisconsin is very cold” Inthewinterwis con sinis very cold

Word Segmentation • Infants must find words in fluent speech • Fluent speech is smooshed togethether • Assess infants word segmentation – Play them fluent speech – Ask if they can detect the difference between words and syllable sequences that aren’t words

Statistical Learning and Words 92% Pretty Baby 5%

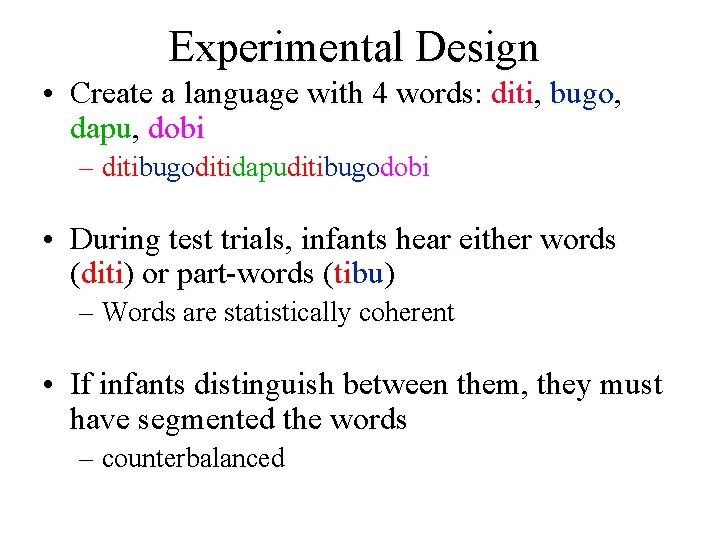

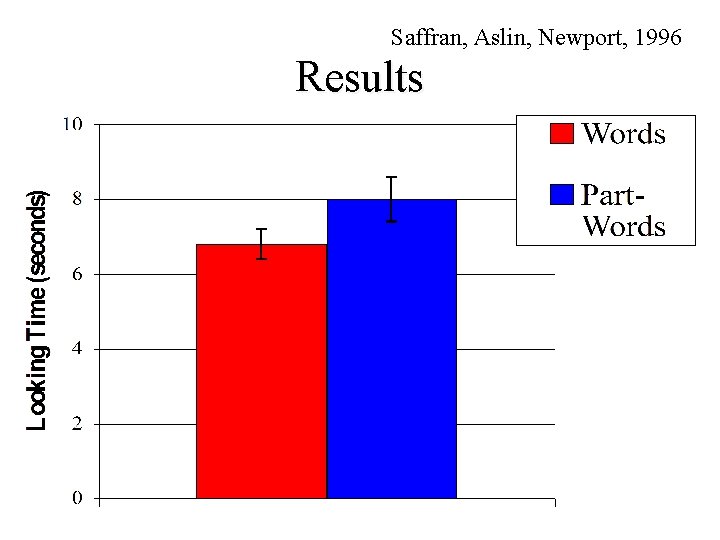

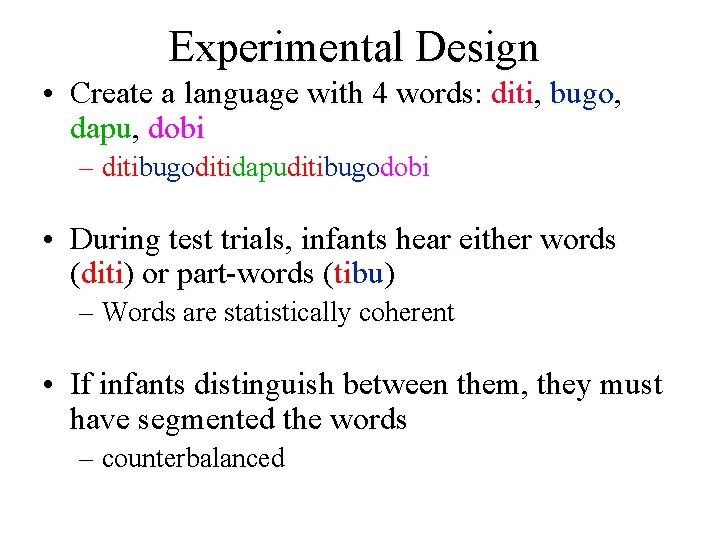

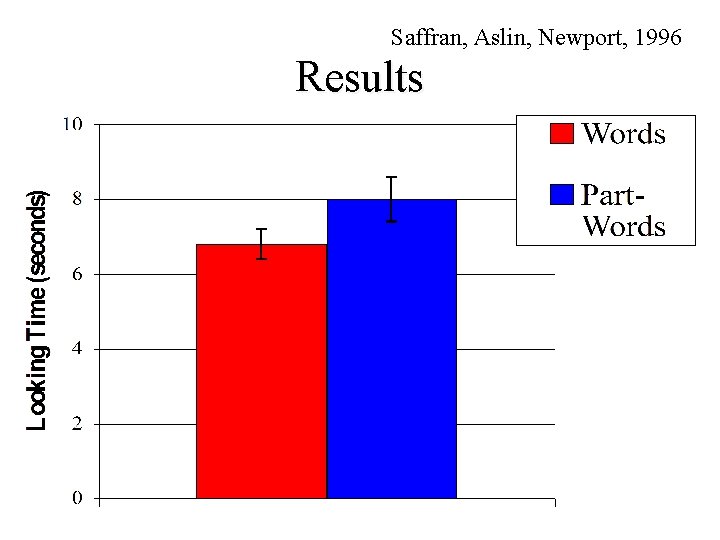

Experimental Design • Create a language with 4 words: diti, bugo, dapu, dobi – ditibugoditidapuditibugodobi • During test trials, infants hear either words (diti) or part-words (tibu) – Words are statistically coherent • If infants distinguish between them, they must have segmented the words – counterbalanced

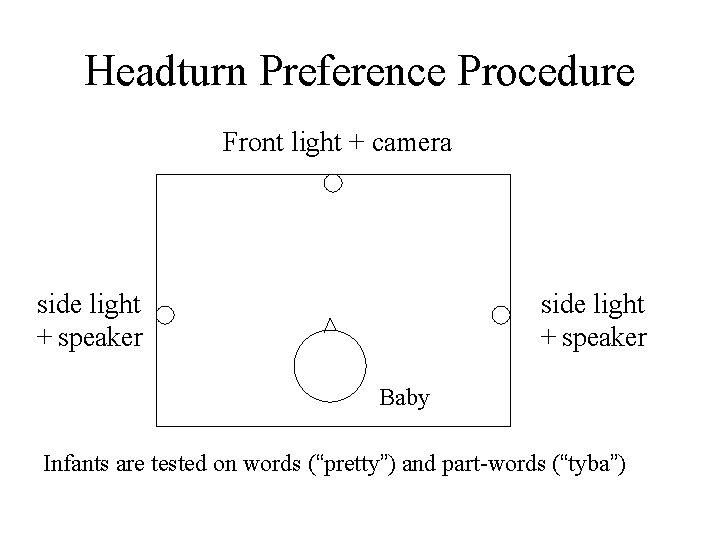

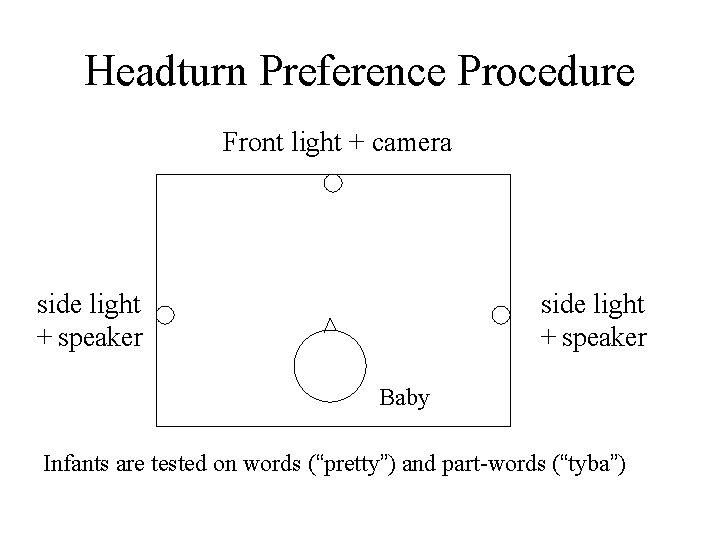

Headturn Preference Procedure Front light + camera side light + speaker Baby Infants are tested on words (“pretty”) and part-words (“tyba”)

Saffran, Aslin, Newport, 1996 Results

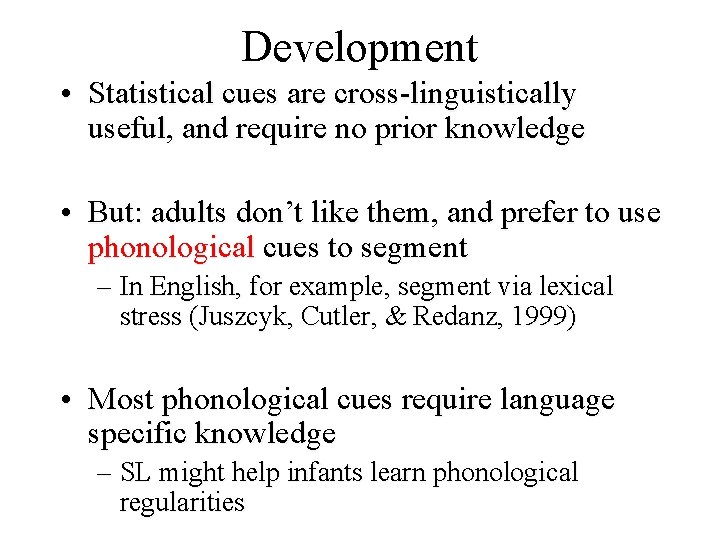

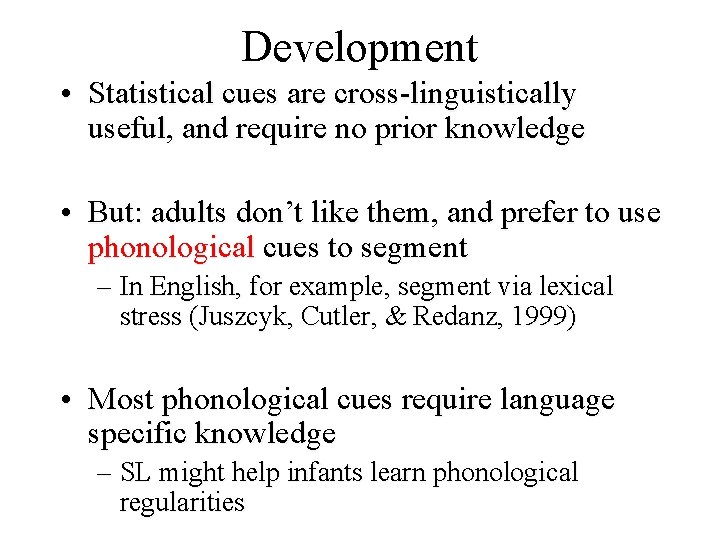

Development • Statistical cues are cross-linguistically useful, and require no prior knowledge • But: adults don’t like them, and prefer to use phonological cues to segment – In English, for example, segment via lexical stress (Juszcyk, Cutler, & Redanz, 1999) • Most phonological cues require language specific knowledge – SL might help infants learn phonological regularities

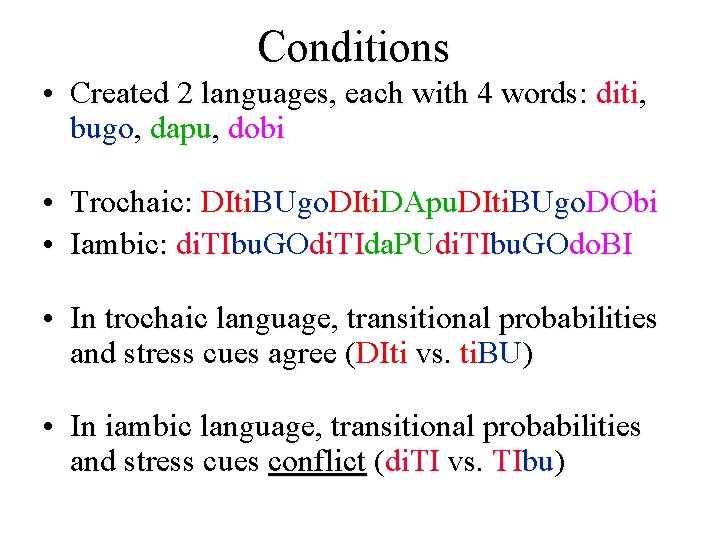

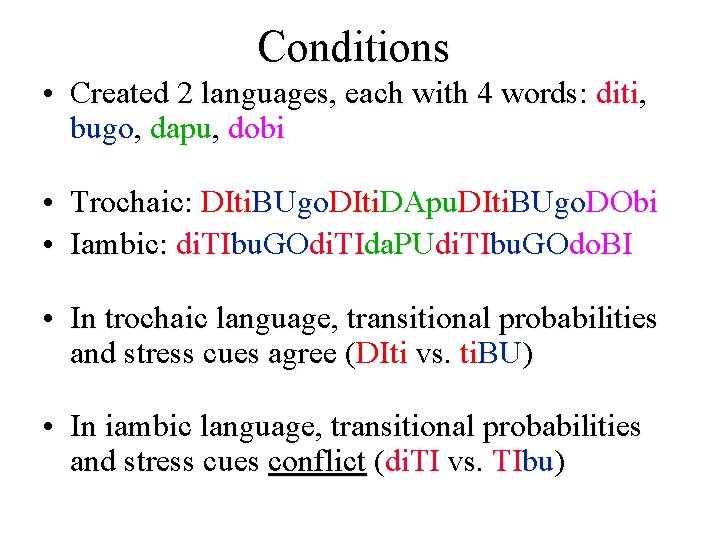

Conditions • Created 2 languages, each with 4 words: diti, bugo, dapu, dobi • Trochaic: DIti. BUgo. DIti. DApu. DIti. BUgo. DObi • Iambic: di. TIbu. GOdi. TIda. PUdi. TIbu. GOdo. BI • In trochaic language, transitional probabilities and stress cues agree (DIti vs. ti. BU) • In iambic language, transitional probabilities and stress cues conflict (di. TI vs. TIbu)

Predictions • Infants are presented with words (diti) and partwords (tibu) during test trials • If infants favor transitional probabilities – Segment the same items from both languages – Show the same pattern of preference • If infants favor stress cues – Segment trochaic and iambic speech differently – Show the opposite pattern of preference

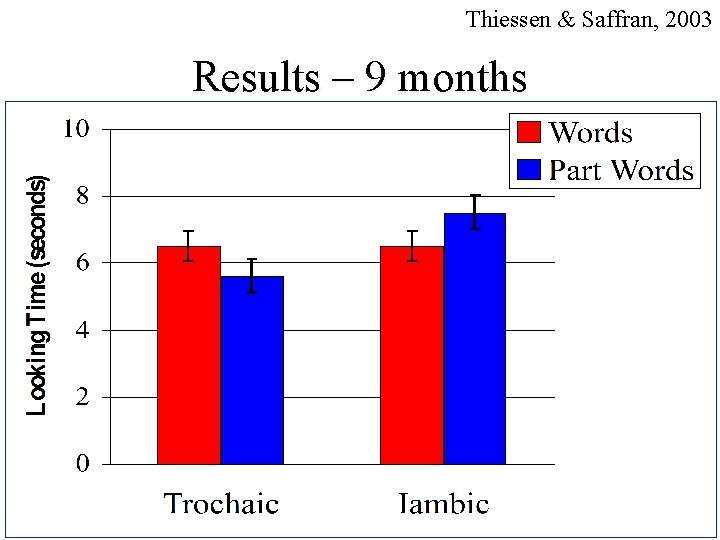

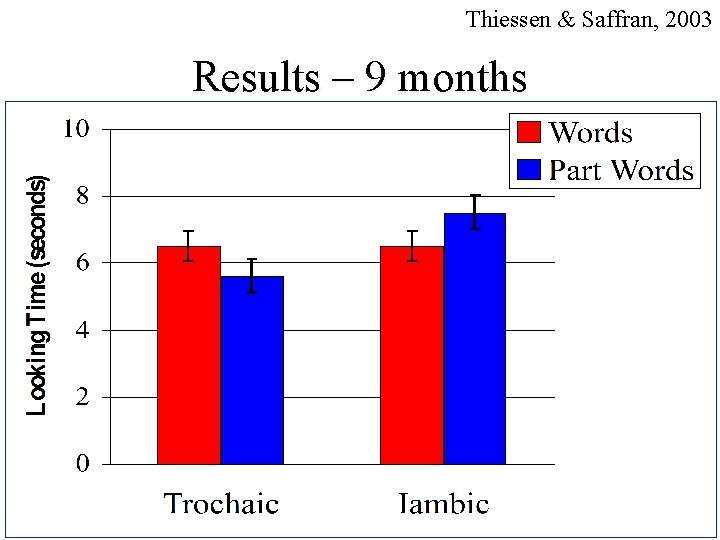

Thiessen & Saffran, 2003 Results – 9 months

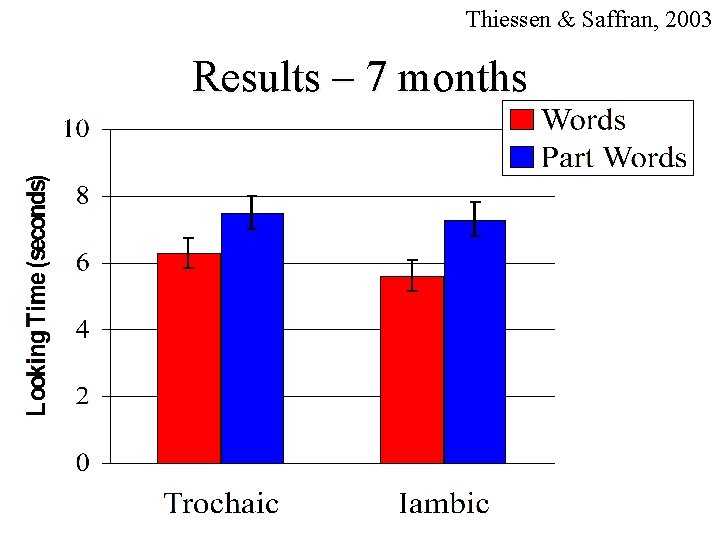

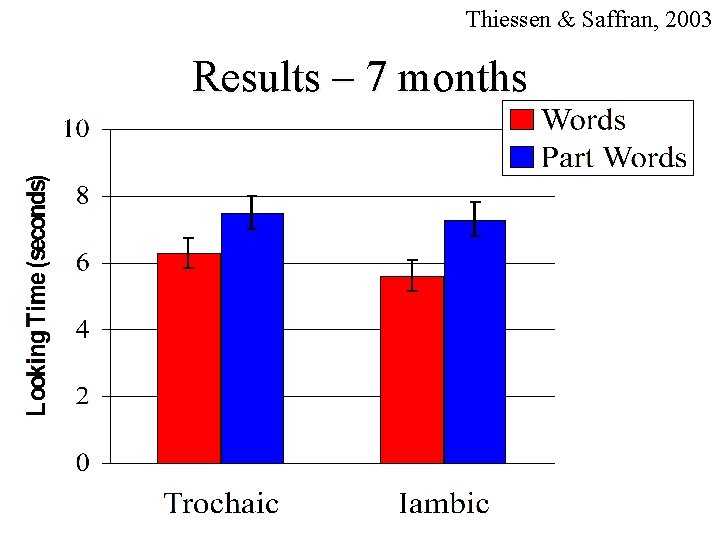

Thiessen & Saffran, 2003 Results – 7 months

Statistics at multiple levels • Transitional probabilities �words �stress • Suggests that SL is an early (first? ) cue to word segmentation and language structure • If this is right, the phonological pattern (lexical stress) should be learned from the output of SL – That is, familiar word forms should teach stress – In principle, could give an iambic bias

Pattern Induction • Expose infants to a list of iambic words – Called the “pattern-induction phase” – ko. GA (pause) tee. LA (pause) tu. ROW… • Then ask them to segment iambic speech – Contains 4 words NOT in pattern-induction phase • If infants learn, they should segment correctly

Conditions • 9 -month-old infants • Trochaic condition – Trochaic pattern induction – Trochaic fluent speech – Infants should segment this language correctly • Iambic condition – Iambic pattern induction – Iambic fluent speech – If infants learn, they should segment correctly

Thiessen & Saffran, 2007 Results

Learning from distributions • Basic result easily replicated – Young infants (T&S 07; Thiessen & Erickson 2013) – Different phonological patterns (Saffran & Thiessen 03; Saffran and Lew-Williams 2012) • Infants learn from the DISTRIBUTION of stress across familiar word forms • Also a PROBABILISTIC type of learning – Infants learn when most words follow pattern – Not entirely clear what “most” means (c. f. Gomez & Gerken 2002; Thiessen & Saffran 2007)

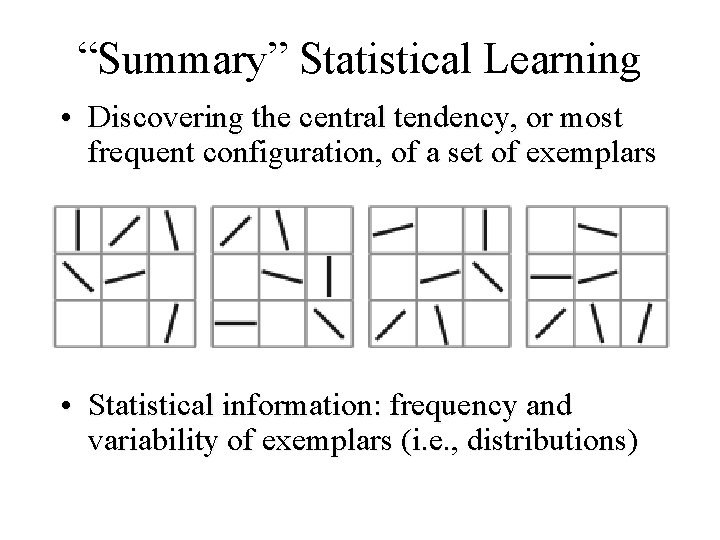

“Summary” Statistical Learning • Discovering the central tendency, or most frequent configuration, of a set of exemplars • Statistical information: frequency and variability of exemplars (i. e. , distributions)

Just how many statistics are there? • “Transitional Probabilities” vs. “Distributions” – Sequential vs. Simultaneous? – Conditional vs. Distributional? – Modality specific processes? • Before answering that question, we need to talk more about “distributional” SL • And the value of modeling (aka, the value of Phil Pavlik)

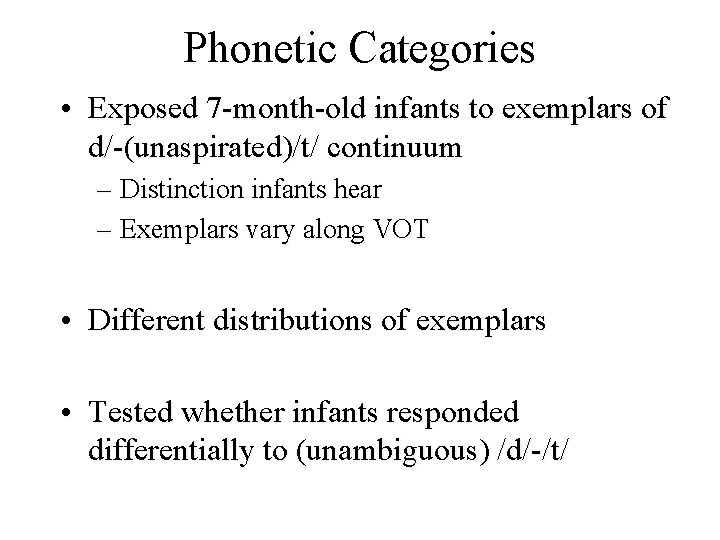

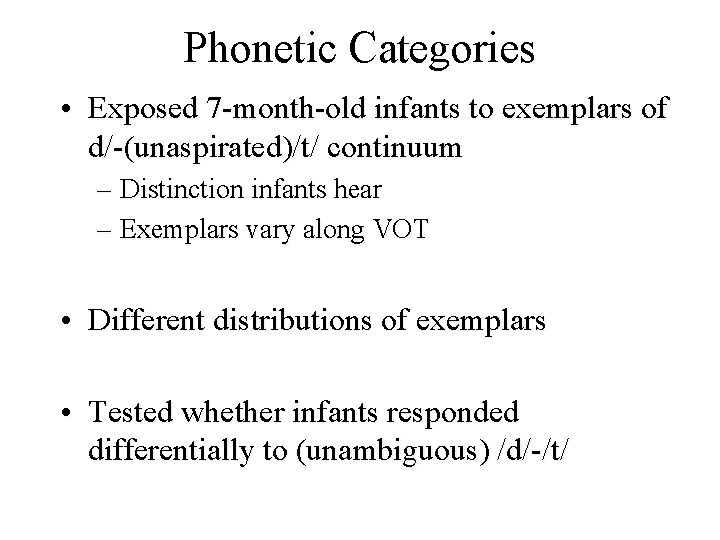

Phonetic Categories • Exposed 7 -month-old infants to exemplars of d/-(unaspirated)/t/ continuum – Distinction infants hear – Exemplars vary along VOT • Different distributions of exemplars • Tested whether infants responded differentially to (unambiguous) /d/-/t/

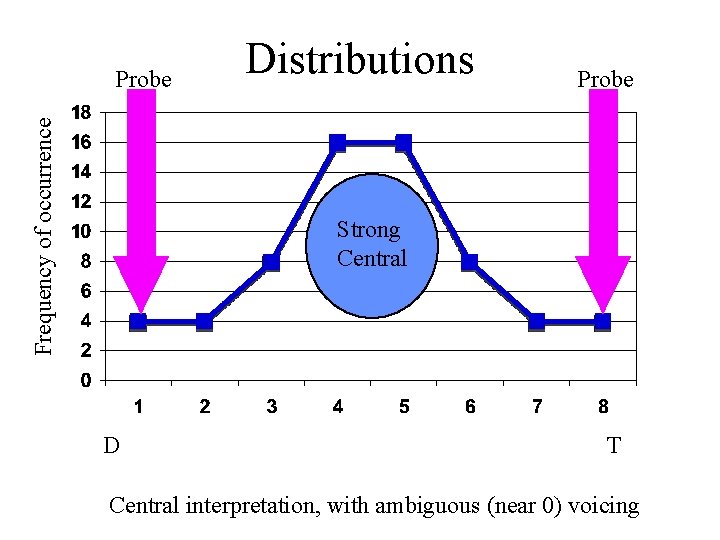

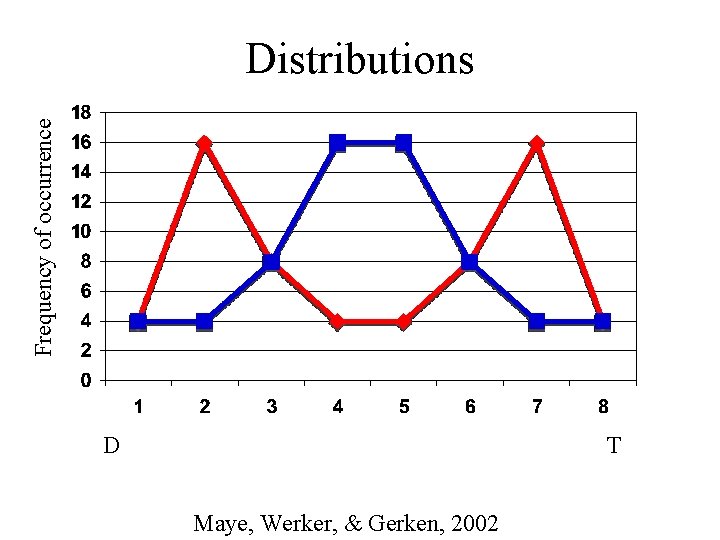

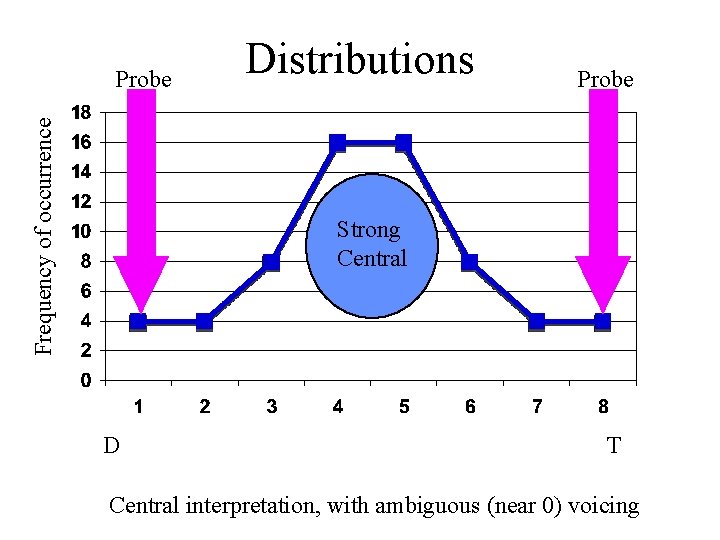

Frequency of occurrence Distributions D T Maye, Werker, & Gerken, 2002

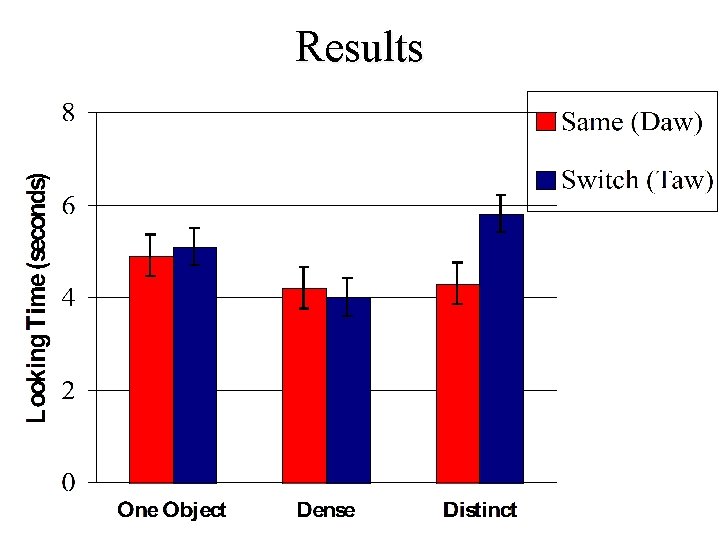

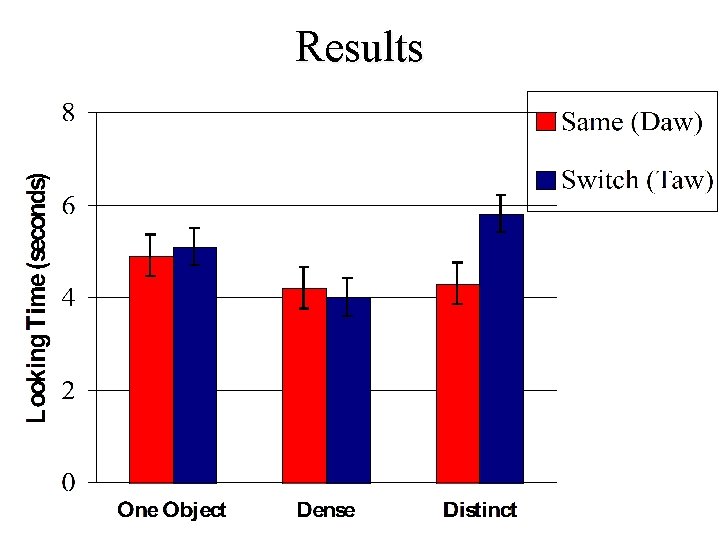

14 -month-old experiment Habituation “Daw” Same “Daw” Switch “Taw”

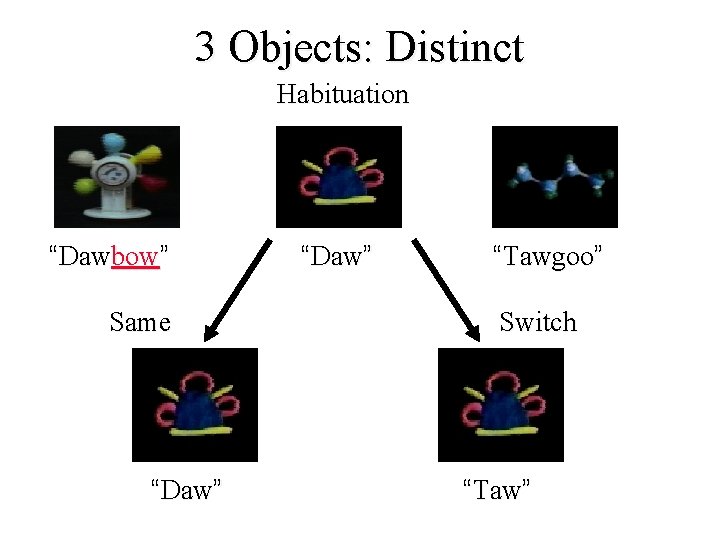

3 Objects: Dense Habituation “Dawgoo” Same “Daw” “Tawgoo” Switch “Taw”

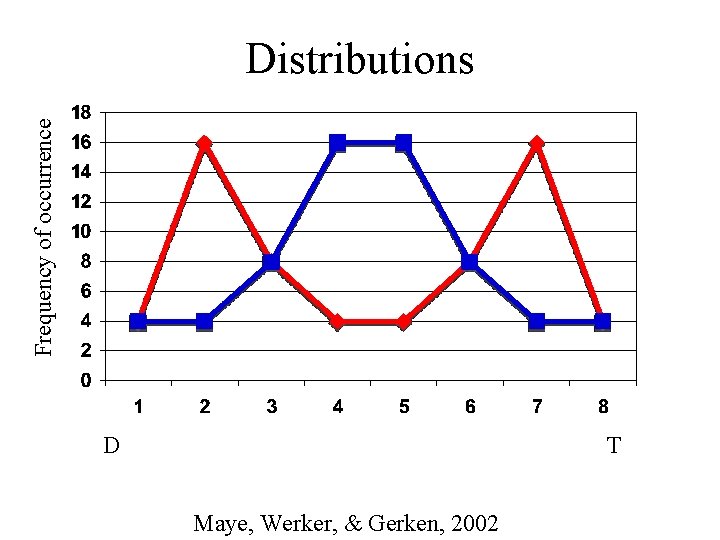

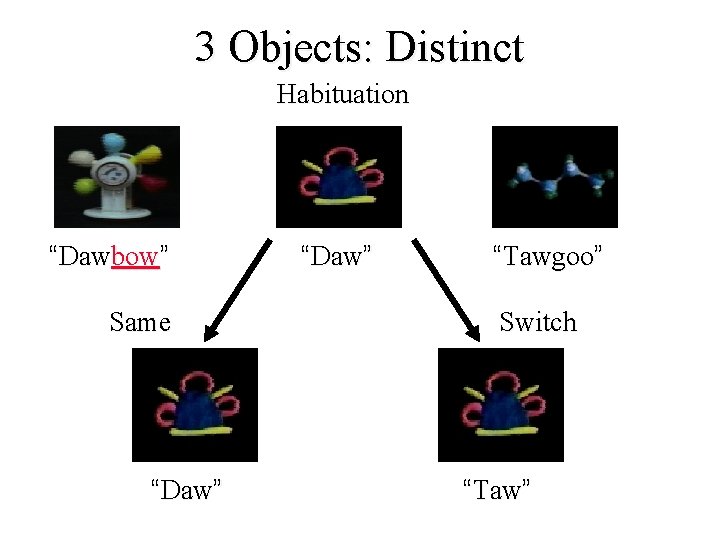

3 Objects: Distinct Habituation “Dawbow” Same “Daw” “Tawgoo” Switch “Taw”

Results

Just how many processes are there? DISTRIBUTIONAL STATISTICAL LEARNING Phonetic Category Learning Acquired Distinctiveness ATTENTIONAL WEIGHTING

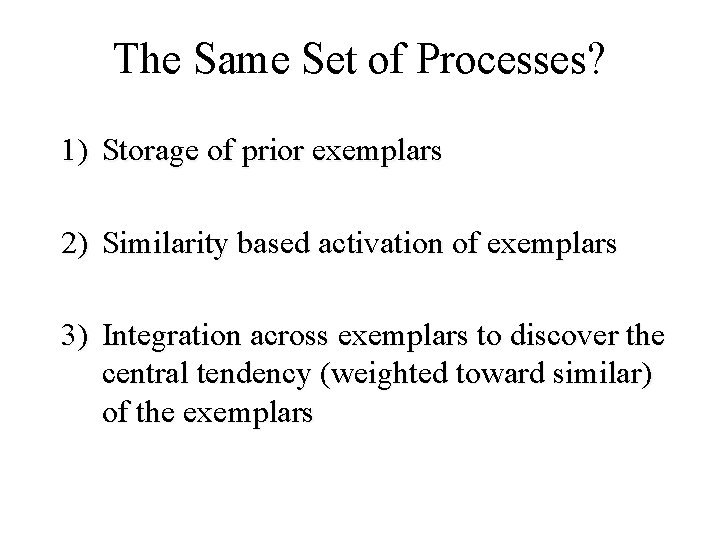

The Same Set of Processes? 1) Storage of prior exemplars 2) Similarity based activation of exemplars 3) Integration across exemplars to discover the central tendency (weighted toward similar) of the exemplars

i. Minerva Voicing

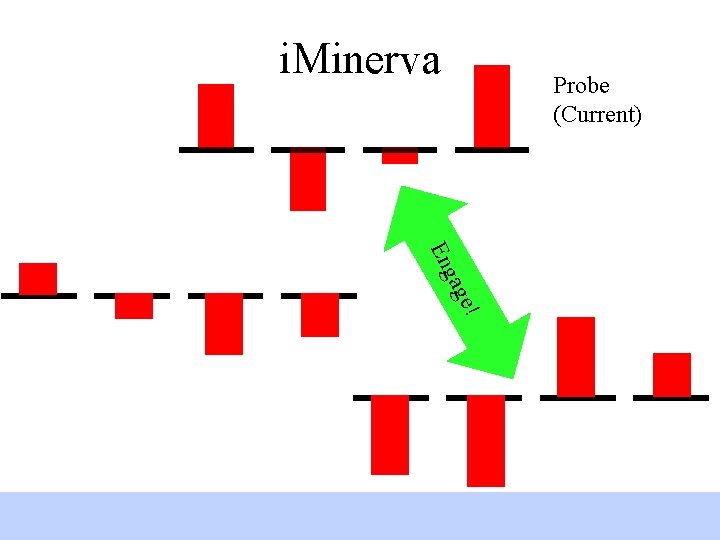

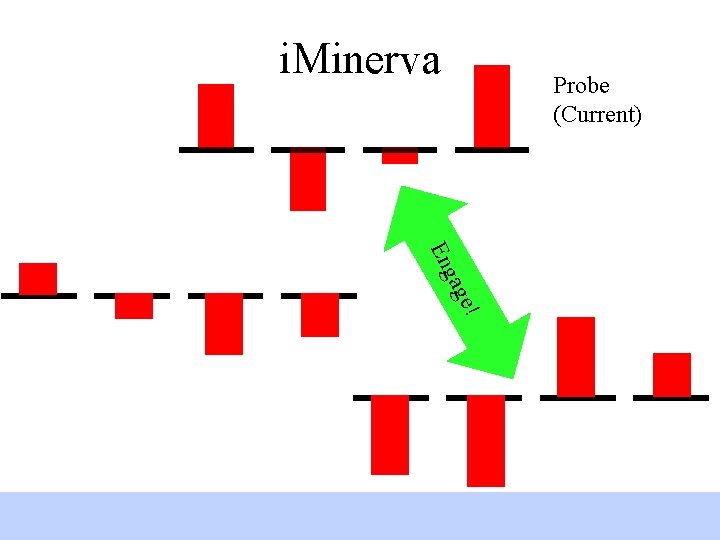

i. Minerva Probe (Current)

i. Minerva Probe (Current) Similarity Threshold

Eng age ! i. Minerva Probe (Current)

i. Minerva Probe (Current) e! gag En

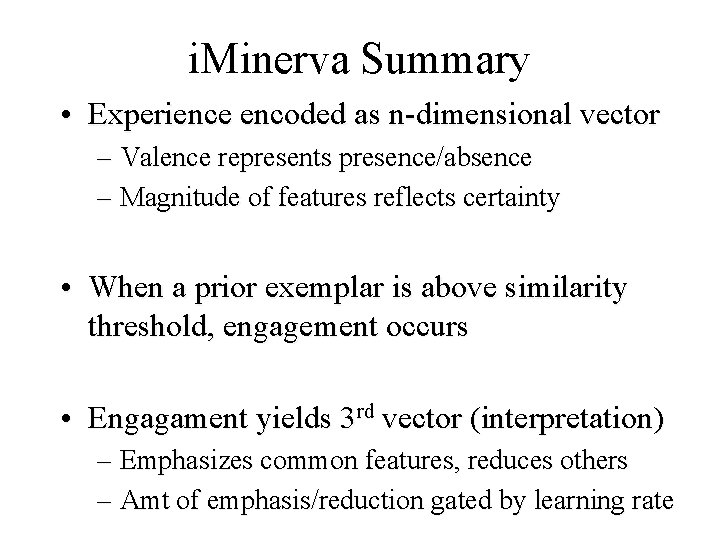

i. Minerva Summary • Experience encoded as n-dimensional vector – Valence represents presence/absence – Magnitude of features reflects certainty • When a prior exemplar is above similarity threshold, engagement occurs • Engagament yields 3 rd vector (interpretation) – Emphasizes common features, reduces others – Amt of emphasis/reduction gated by learning rate

Frequency of occurrence Probe Distributions Probe Strong Central D T Central interpretation, with ambiguous (near 0) voicing

Distributions Frequency of occurrence Probe Intrp 1 D Probe Intrp 2 T Two more extreme interpretations, with distinct voicing values

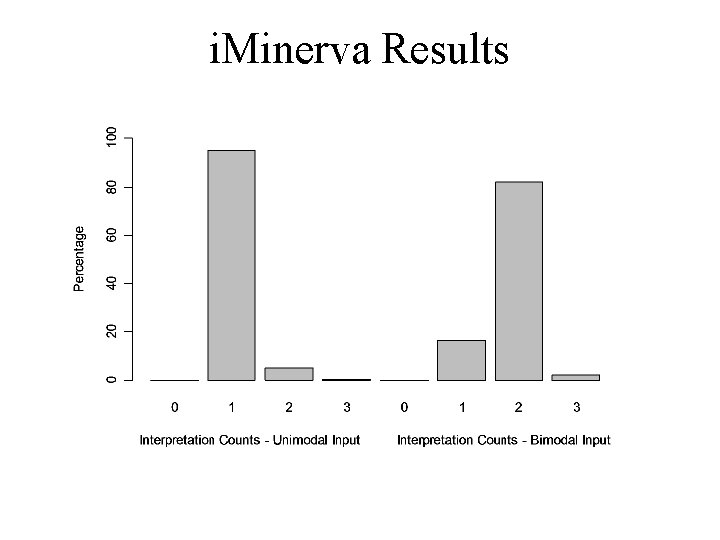

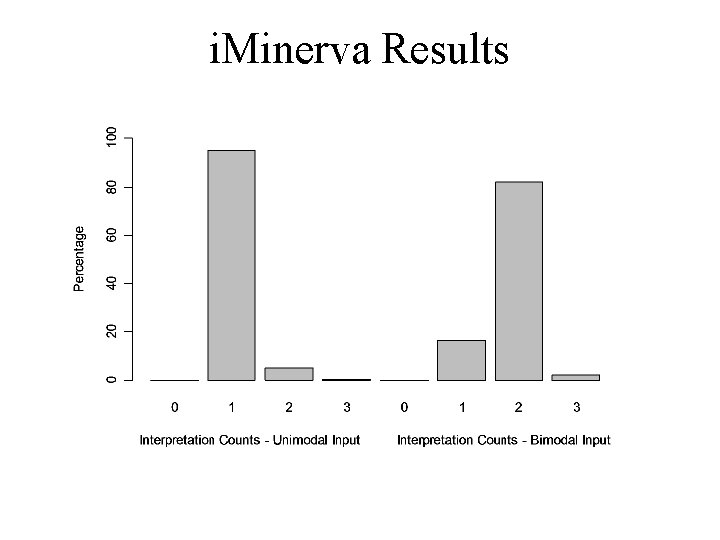

i. Minerva Results

Acquired Distinctiveness Habituation “Daw” Same “Daw” Switch “Taw”

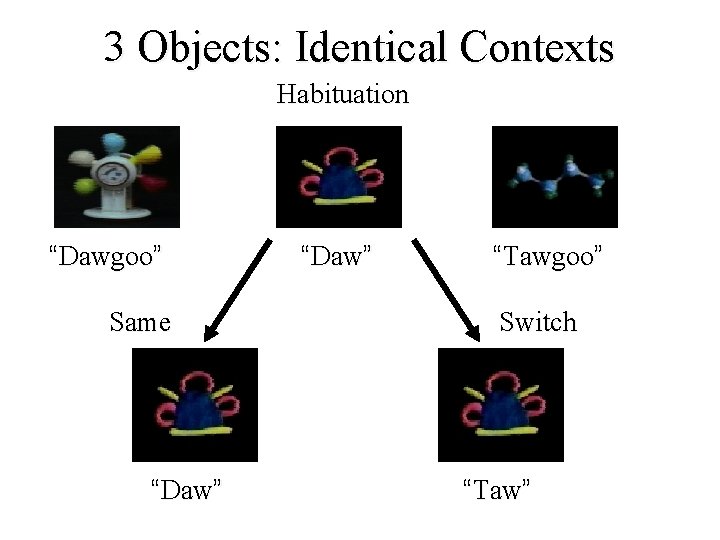

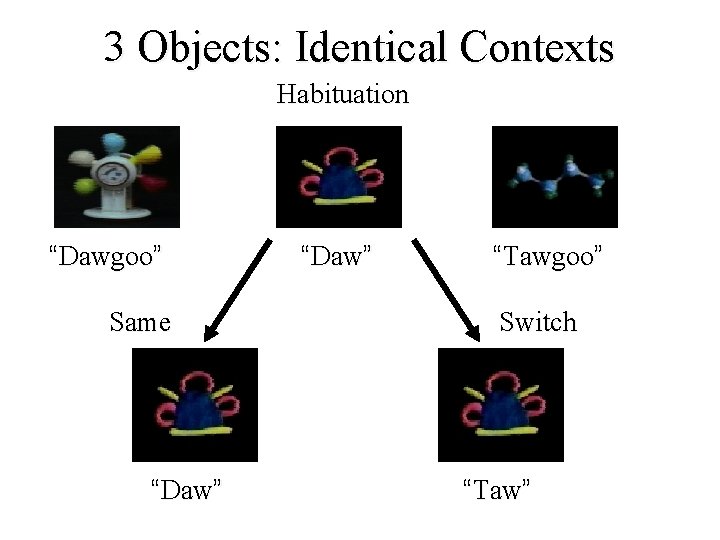

3 Objects: Identical Contexts Habituation “Dawgoo” Same “Daw” “Tawgoo” Switch “Taw”

3 Objects: Distinct Contexts Habituation “Dawbow” Same “Daw” “Tawgoo” Switch “Taw”

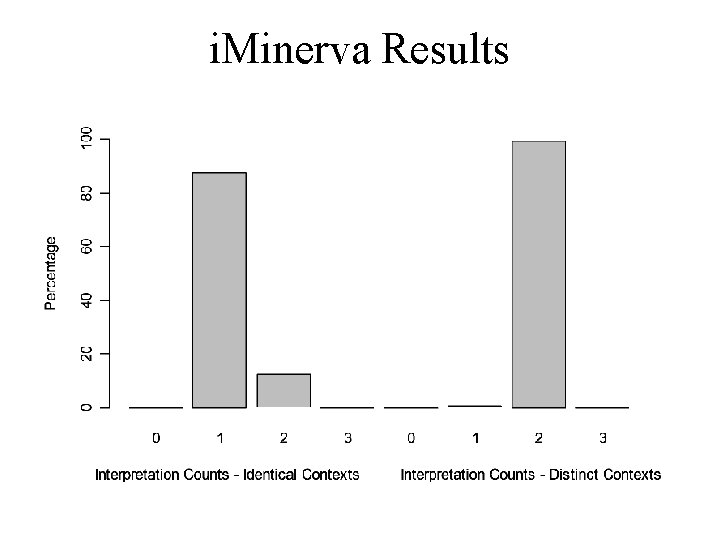

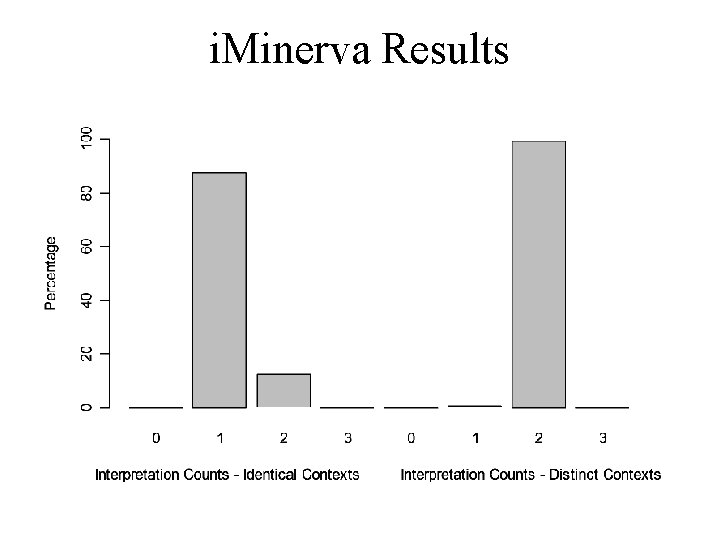

i. Minerva Results

Single Interpretation (Daw or Taw) Biased for voicing Consistent second syllable information

Daw Probe Two Interpretations 1 st feature voiced 1 st feature voiceless

The story so far… • i. Minerva can account for both “distributional learning” and “acquired distinctiveness” – An existence proof – Possibly for many more (all? ) summary statistics? • Just reinvent (or redescribe) the wheel? – Does it make novel predictions? – Different from other accounts?

Developing Phonemic Contrasts • At 14 months, infants respond equivalently to minimal pair labels in Switch tasks – Succeed by 18 months – Only tested on word-initial stop consonants • Werker et al. explanation for this is “capacity” – Related to ‘attention’ as cause of learning from acquired distinctiveness – Typically used to argue/assume that change at 18 months is stage-like

i. Minerva and Development • Learning is driven by experience with phonemes in lexical contexts • Suggests that use of phonemes should be predictable from the child’s lexicon • To get more specific predictions, fed the items from the Mac. Arthur CDI to i. Minerva – Only mono and bisyllabic words – Two ‘versions’ of the lexicon

Lexical Information • Exposure to lexical items makes phonemic interpretations more distinct – Interps differ on more features – Because children know few minimal pairs • Degree of differentiation depends on both: – How frequently a phoneme occurs – How many words it occurs in • Phonemes in Switch task high on both counts

The effect of lexical context Baby Bottle Balloon Byebye …. . Sleep Sock Stroller Swing …. . Similarity metric B S Pretty Pants pillow please …. . P Z S-Z pair yields more similar interpretations Zoo Zipper ? ? ?

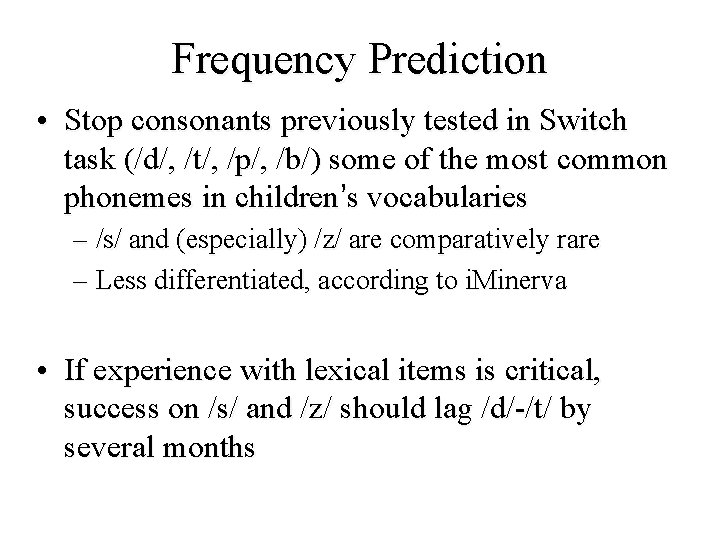

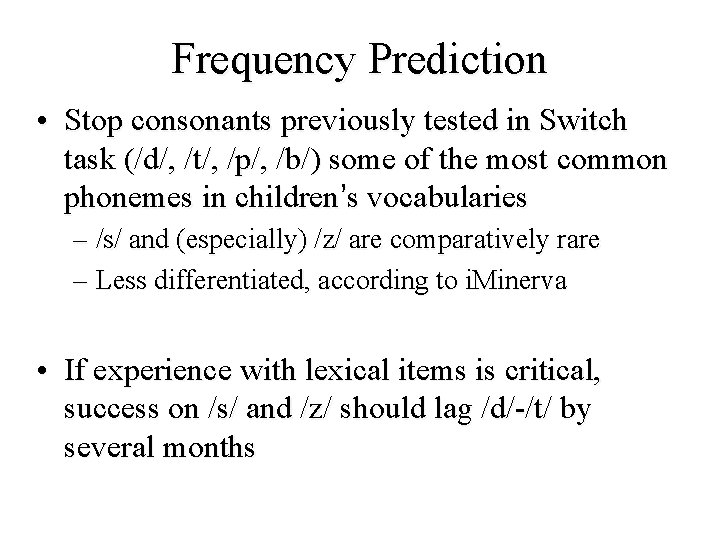

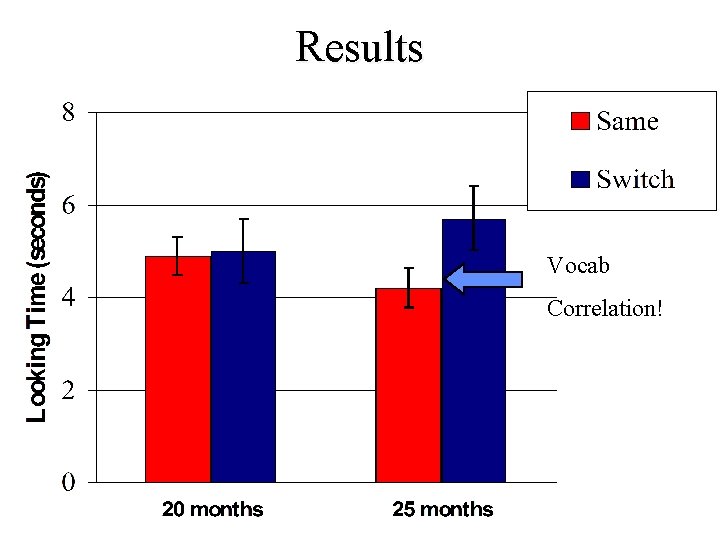

Frequency Prediction • Stop consonants previously tested in Switch task (/d/, /t/, /p/, /b/) some of the most common phonemes in children’s vocabularies – /s/ and (especially) /z/ are comparatively rare – Less differentiated, according to i. Minerva • If experience with lexical items is critical, success on /s/ and /z/ should lag /d/-/t/ by several months

Single Object: /s/ and /z/ Habituation “Seer” Same “Seer” Switch “Zeer”

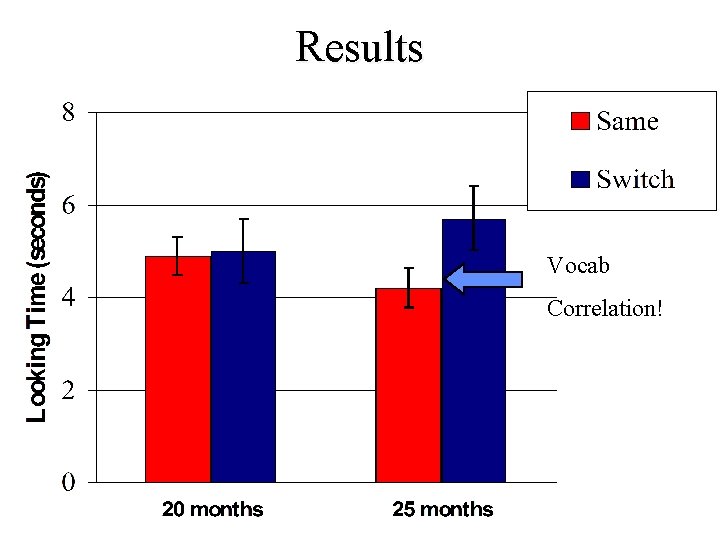

Results Vocab Correlation!

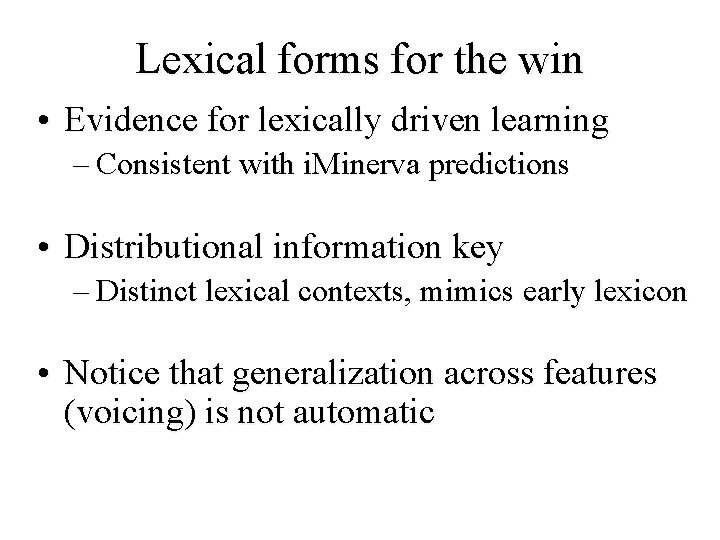

Lexical forms for the win • Evidence for lexically driven learning – Consistent with i. Minerva predictions • Distributional information key – Distinct lexical contexts, mimics early lexicon • Notice that generalization across features (voicing) is not automatic

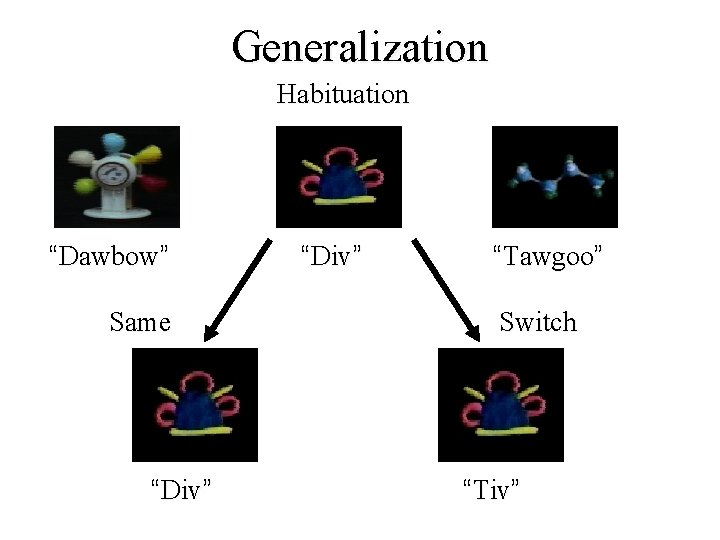

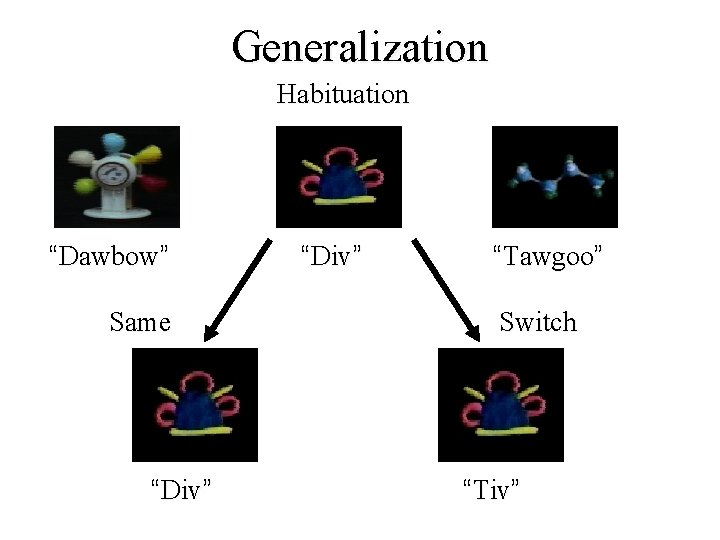

Generalization Habituation “Dawbow” Same “Div” “Tawgoo” Switch “Tiv”

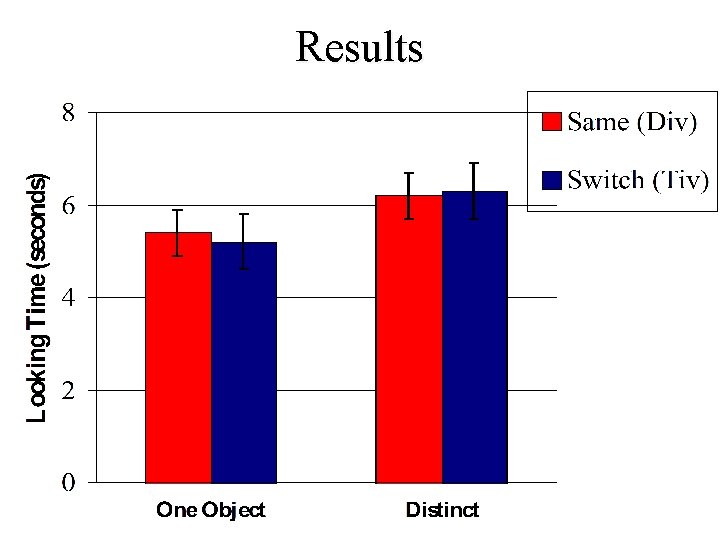

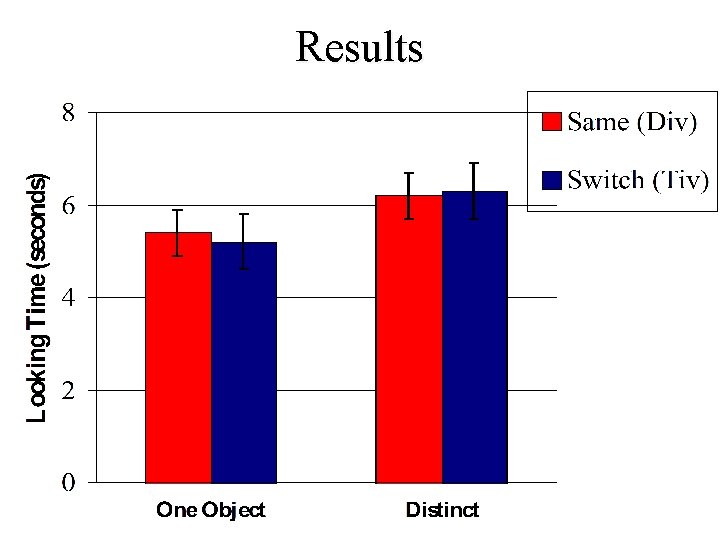

Results

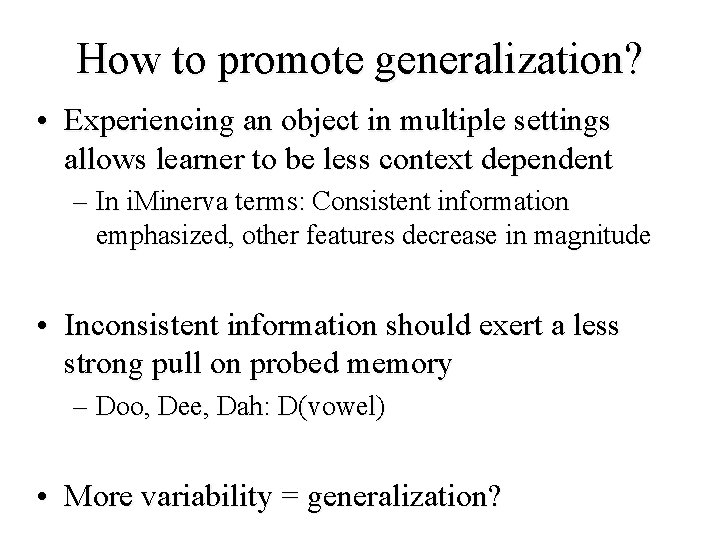

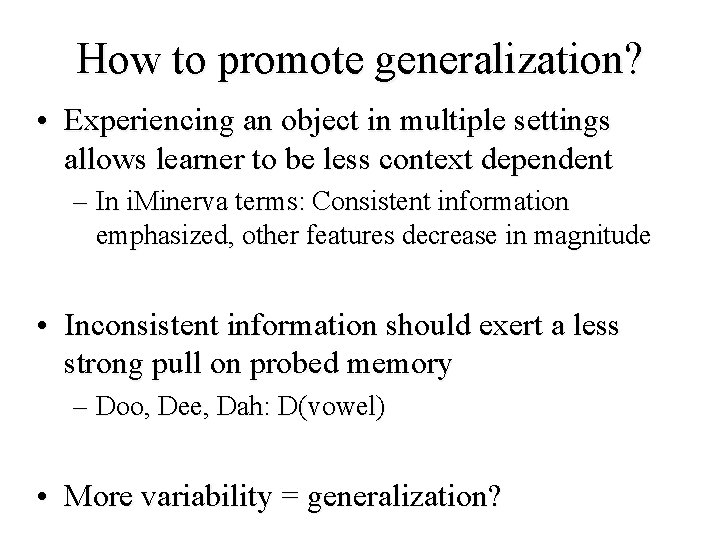

How to promote generalization? • Experiencing an object in multiple settings allows learner to be less context dependent – In i. Minerva terms: Consistent information emphasized, other features decrease in magnitude • Inconsistent information should exert a less strong pull on probed memory – Doo, Dee, Dah: D(vowel) • More variability = generalization?

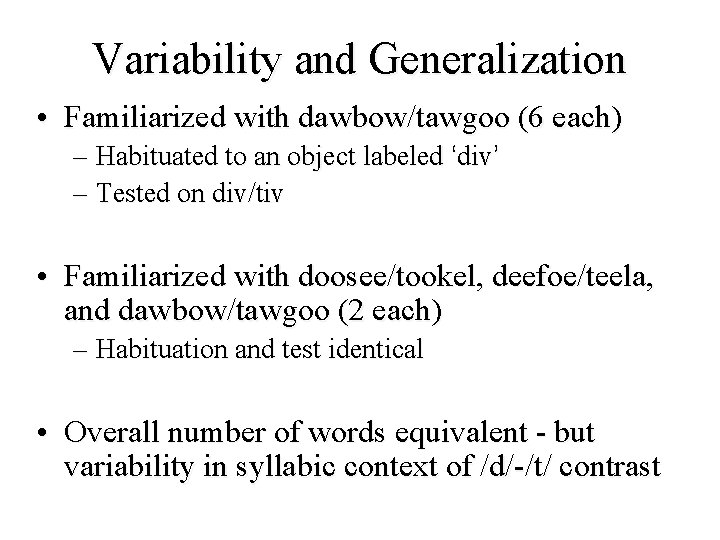

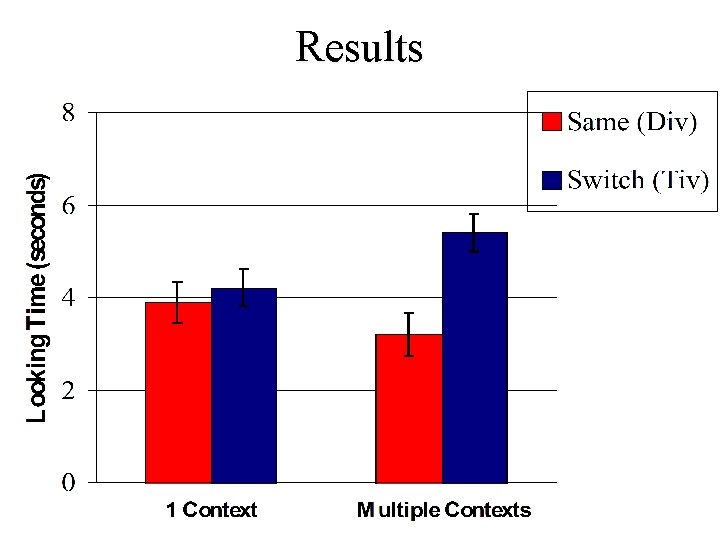

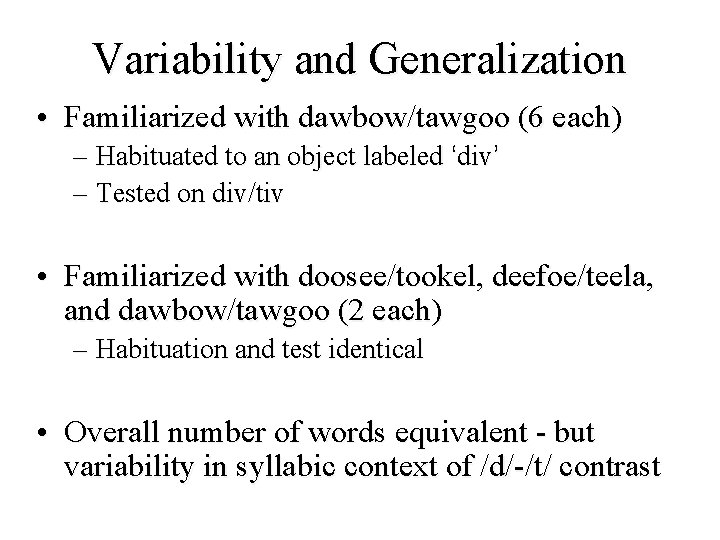

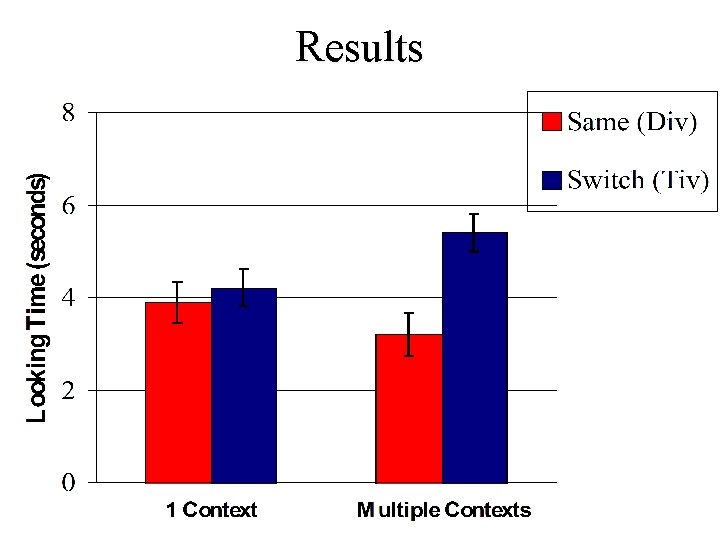

Variability and Generalization • Familiarized with dawbow/tawgoo (6 each) – Habituated to an object labeled ‘div’ – Tested on div/tiv • Familiarized with doosee/tookel, deefoe/teela, and dawbow/tawgoo (2 each) – Habituation and test identical • Overall number of words equivalent - but variability in syllabic context of /d/-/t/ contrast

Results

Conclusions • i. Minerva provides a simple, unified account of many distributional learning tasks – Also: phonological learning, non-adjacent relations • Consistent with domain-general accounts of language acquisition – Which is another set of predictions to examine • One thing it doesn’t (yet) do: segmentation – So i. Minerva doesn’t capture how learning phonology influences subsequent segmentation