States of Matter Interparticle Forces Intramolecular Forces Within

- Slides: 71

States of Matter Inter-particle Forces

Intramolecular Forces • “Within” the molecule. • Molecules are formed by sharing electrons between the atoms. • Hold the atoms of a molecule together.

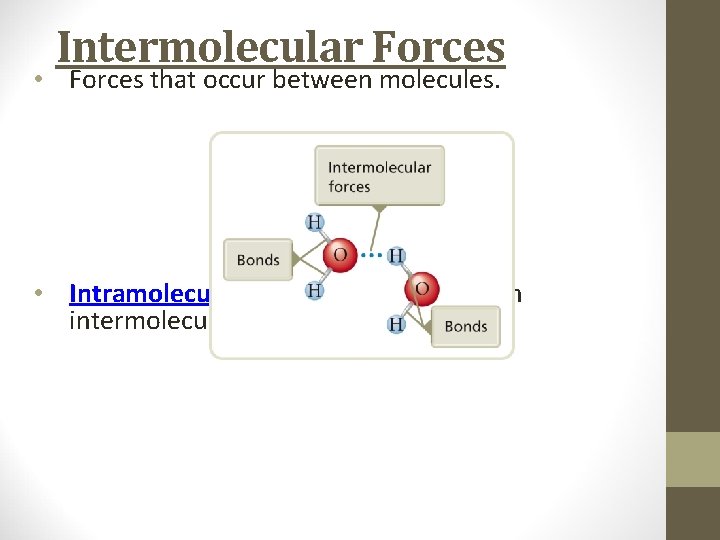

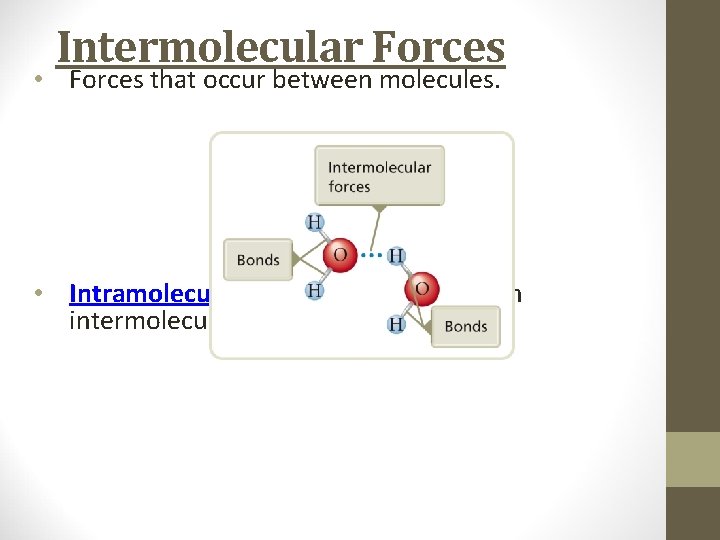

Intermolecular Forces • Forces that occur between molecules. • Intramolecular bonds are stronger than intermolecular forces.

Intermolecular Forces • Forces that occur between molecules. § Dipole–dipole forces Ø Hydrogen bonding § London dispersion forces

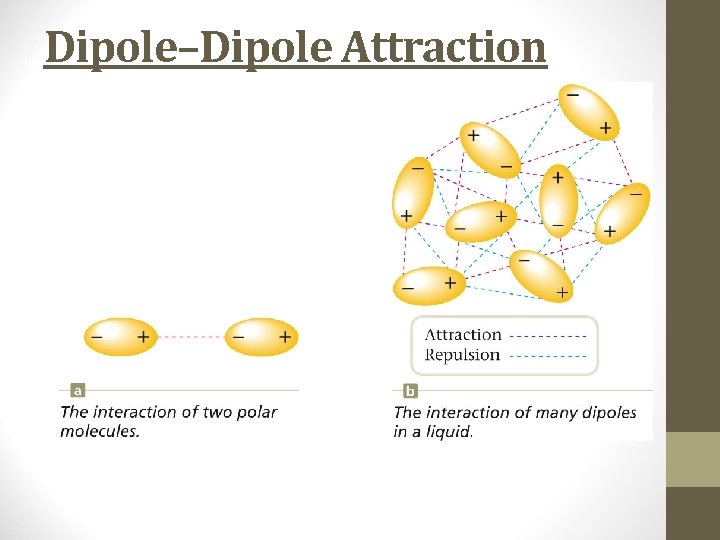

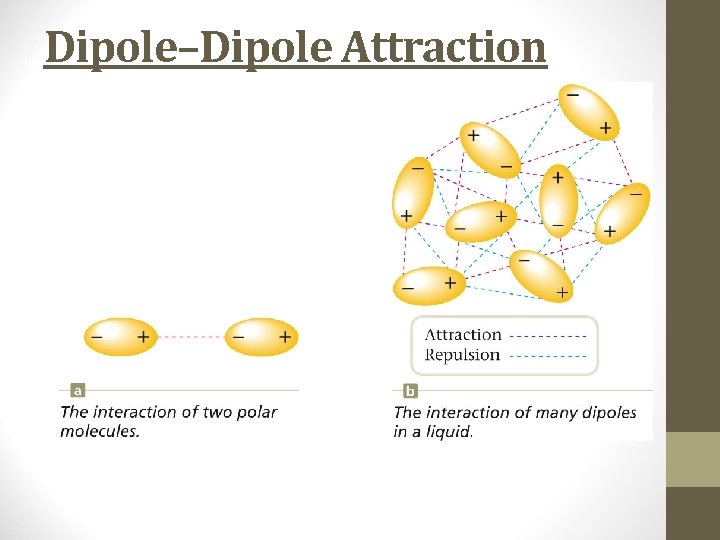

Dipole–Dipole Attraction

Dipole-Dipole Forces • Dipole moment – molecules with polar bonds often behave in an electric field as if they had a center of positive charge and a center of negative charge. • Molecules with dipole moments can attract each other electrostatically. They line up so that the positive and negative ends are close to each other. • Only about 1% as strong as covalent or ionic bonds.

Hydrogen Bonding • Strong dipole-dipole forces. • Hydrogen is bound to a highly electronegative atom – nitrogen, oxygen, or fluorine.

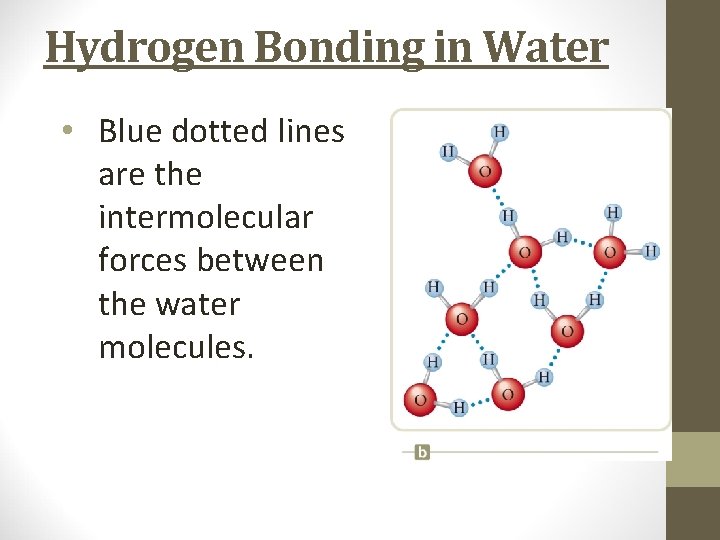

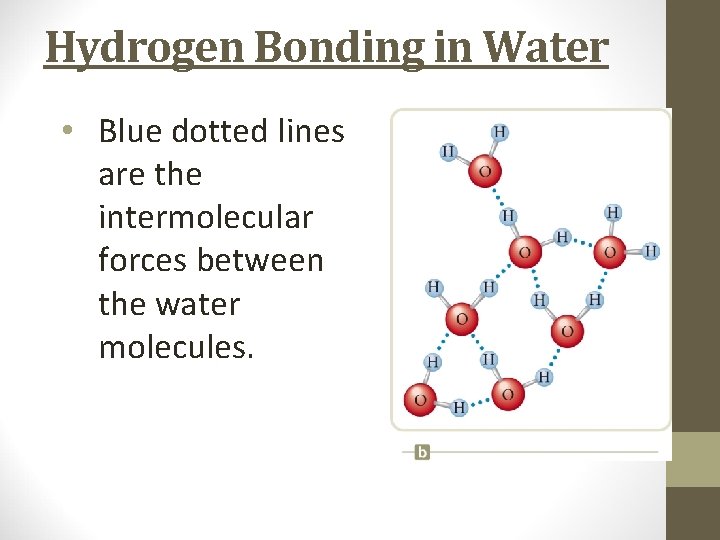

Hydrogen Bonding in Water • Blue dotted lines are the intermolecular forces between the water molecules.

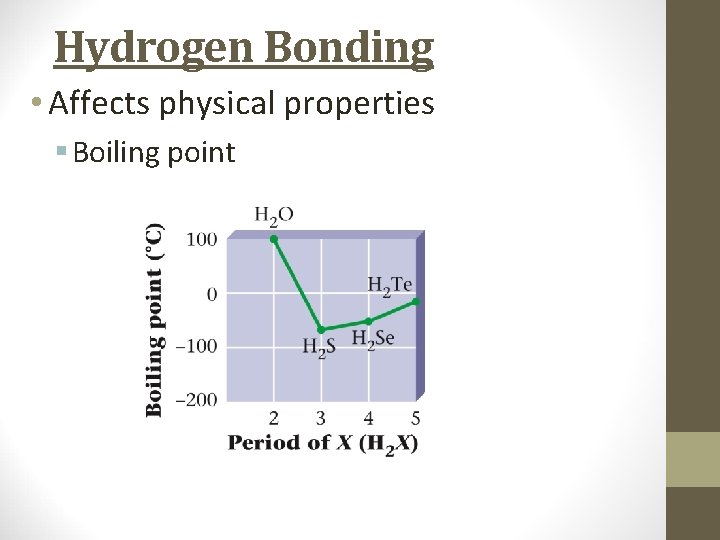

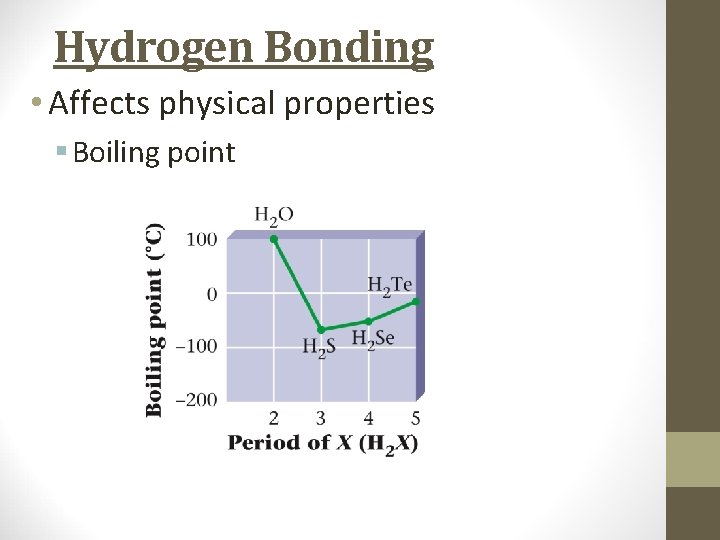

Hydrogen Bonding • Affects physical properties § Boiling point

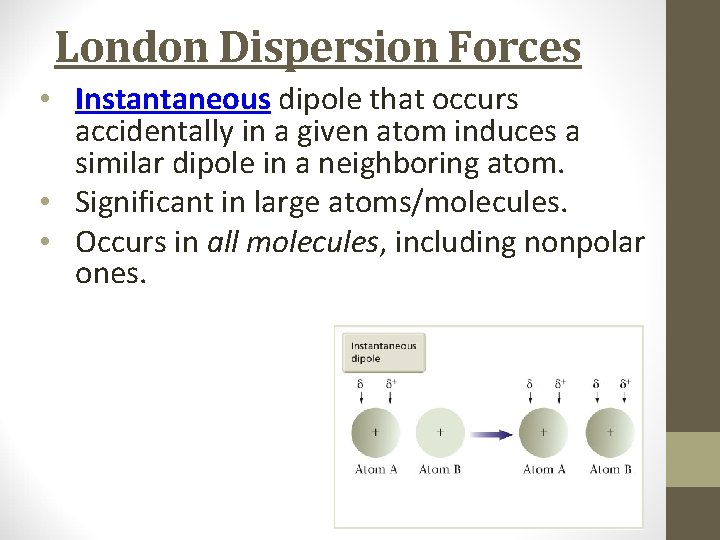

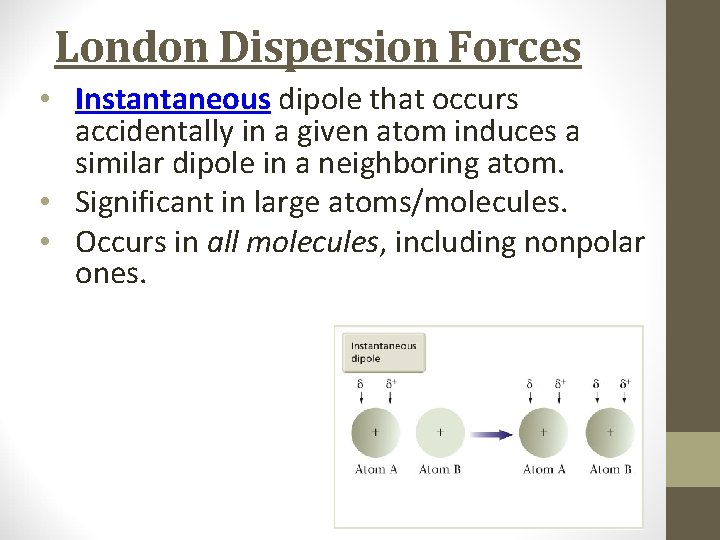

London Dispersion Forces • Instantaneous dipole that occurs accidentally in a given atom induces a similar dipole in a neighboring atom. • Significant in large atoms/molecules. • Occurs in all molecules, including nonpolar ones.

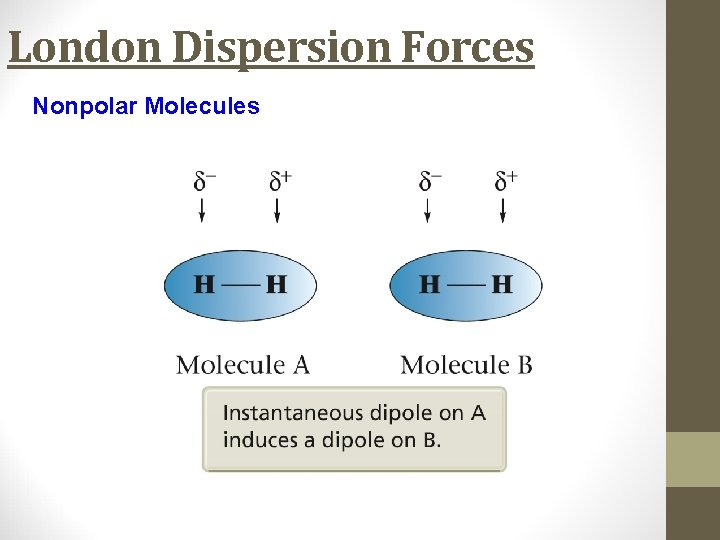

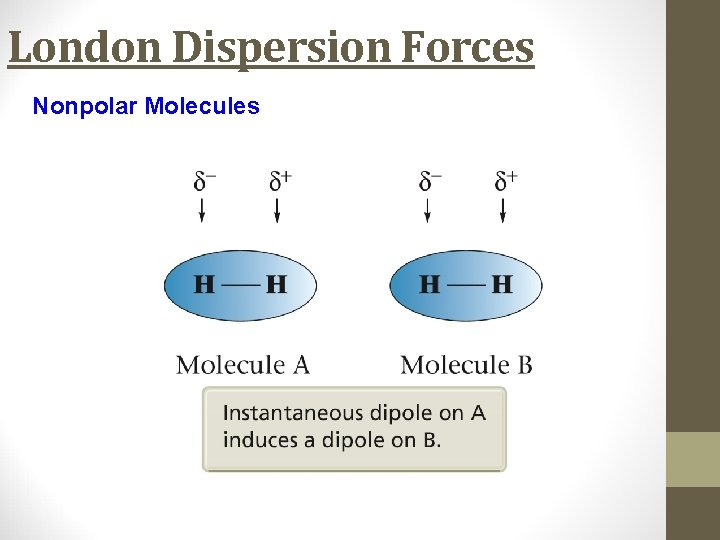

London Dispersion Forces Nonpolar Molecules

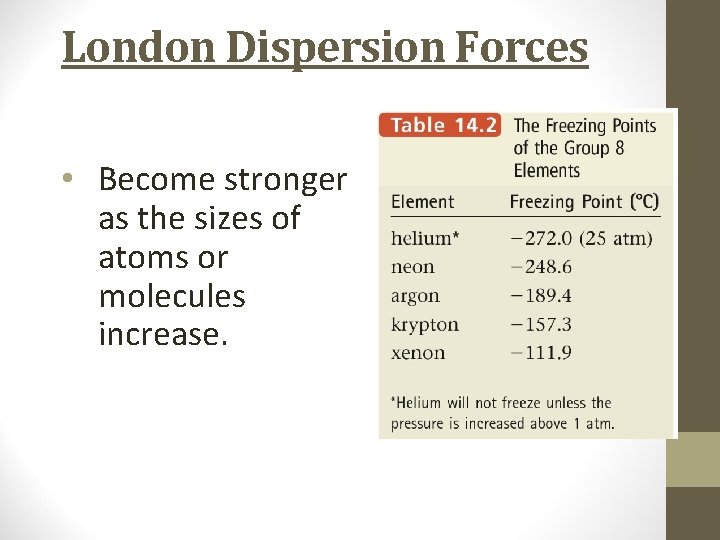

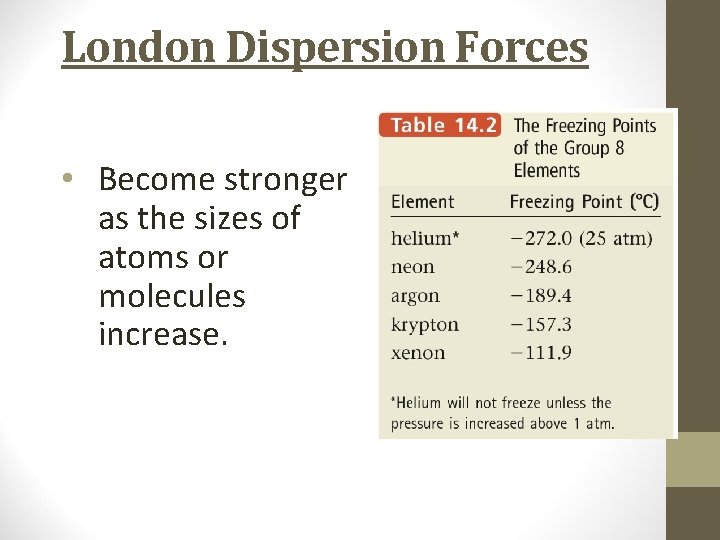

London Dispersion Forces • Become stronger as the sizes of atoms or molecules increase.

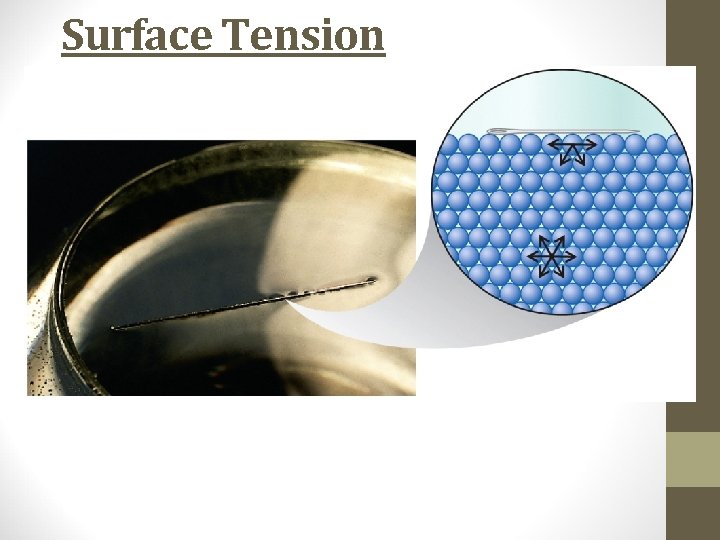

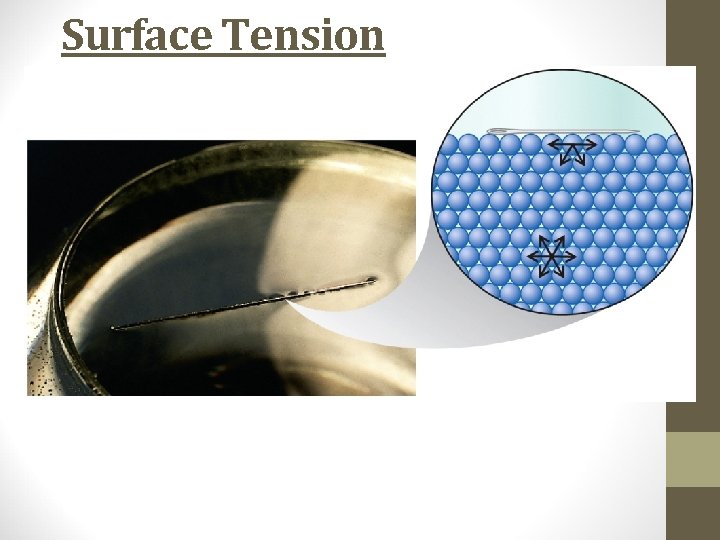

Surface Tension

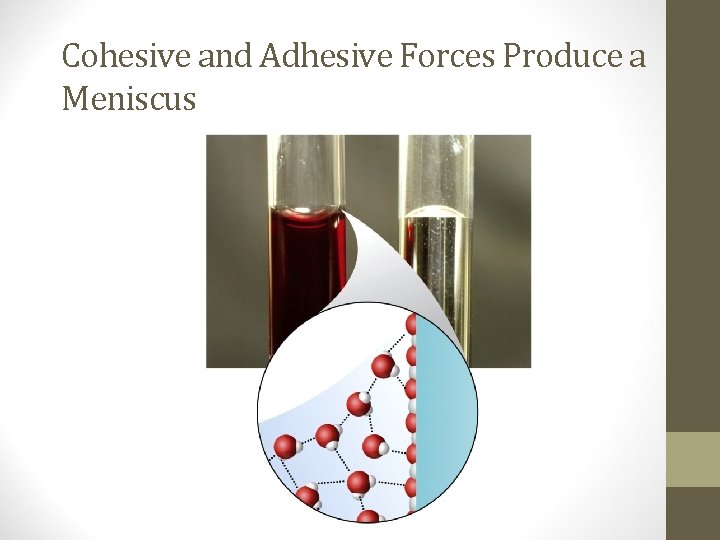

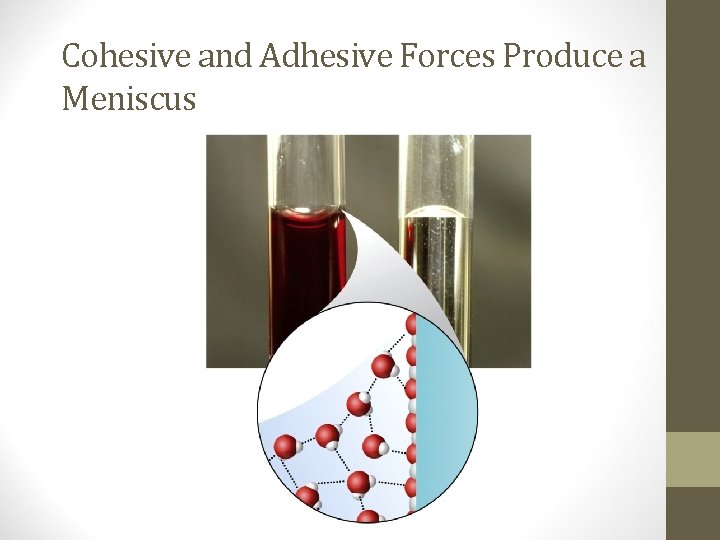

Cohesive and Adhesive Forces Produce a Meniscus

Melting and Boiling Points • In general, the stronger the intermolecular forces, the higher the melting and boiling points.

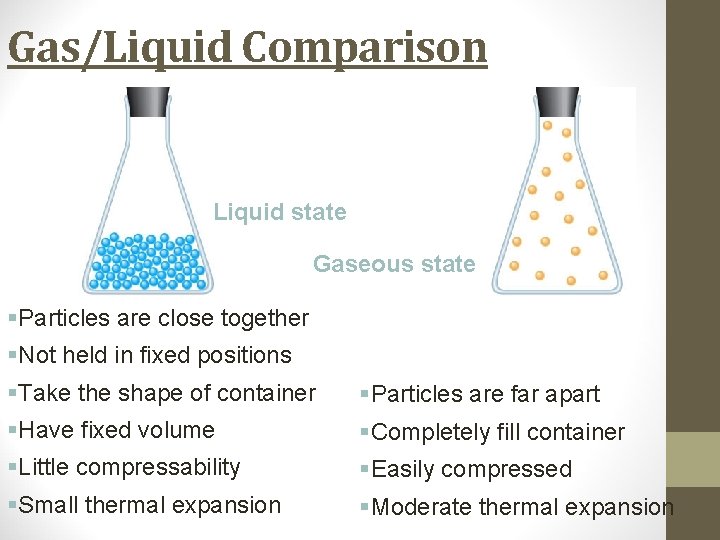

The Liquid State In the liquid state the particles are randomly arranged (like in a gas). The particles are closer to each other than in gases so the density of liquids is greater than that of gases, thus attractive forces between liquid particles is stronger than in gases. Liquids adopt the shape of the container into which they are placed. Unlike gases liquids have a fixed volume and density. This is because they have greater attractive forces between particles holding them close together.

The Liquid State As the particles in liquids are very close to one another they have small compressibility. When particles of a liquid are heated the particles will move around more rapidly. As they have many close neighbors they may only travel a short distant before undergoing a collision and bouncing back in the opposite direction. For this reason liquids have little thermal expansion.

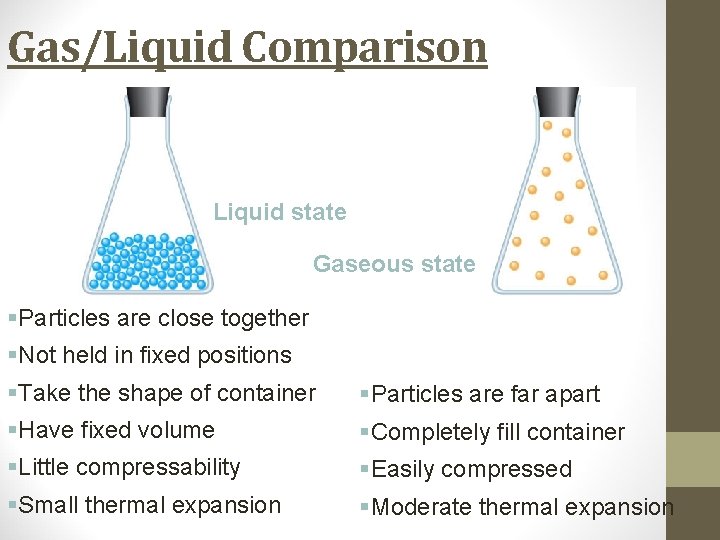

Gas/Liquid Comparison Liquid state Gaseous state §Particles are close together §Not held in fixed positions §Take the shape of container §Particles are far apart §Have fixed volume §Completely fill container §Little compressability §Easily compressed §Small thermal expansion §Moderate thermal expansion

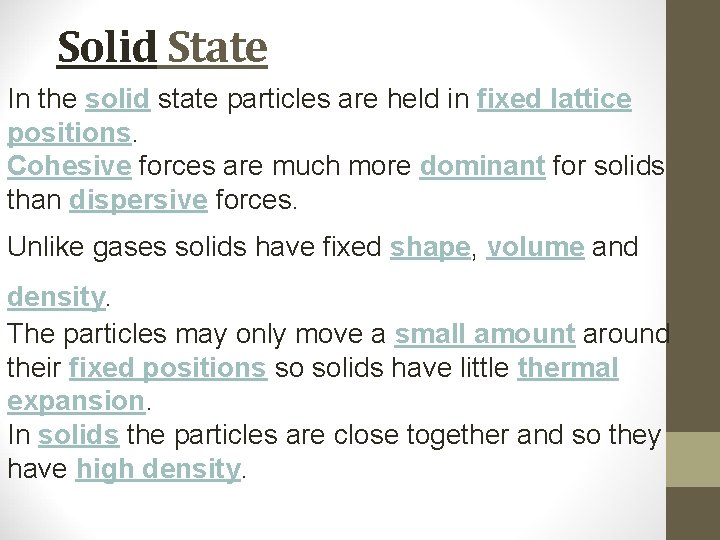

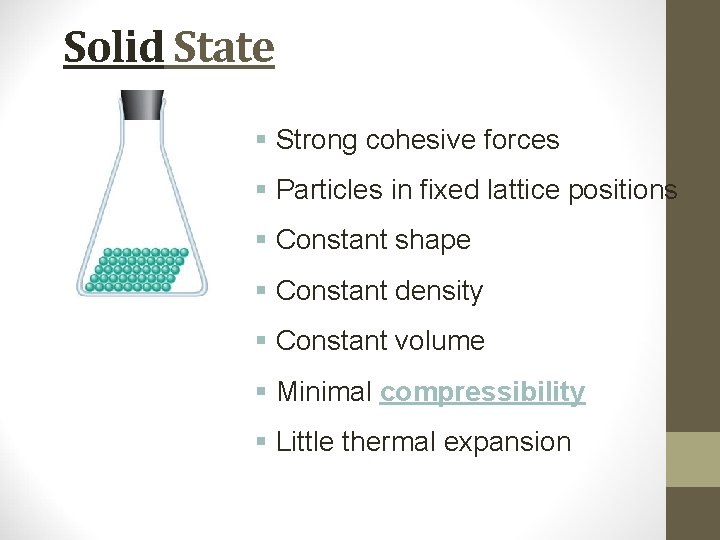

Solid State In the solid state particles are held in fixed lattice positions. Cohesive forces are much more dominant for solids than dispersive forces. Unlike gases solids have fixed shape, volume and density. The particles may only move a small amount around their fixed positions so solids have little thermal expansion. In solids the particles are close together and so they have high density.

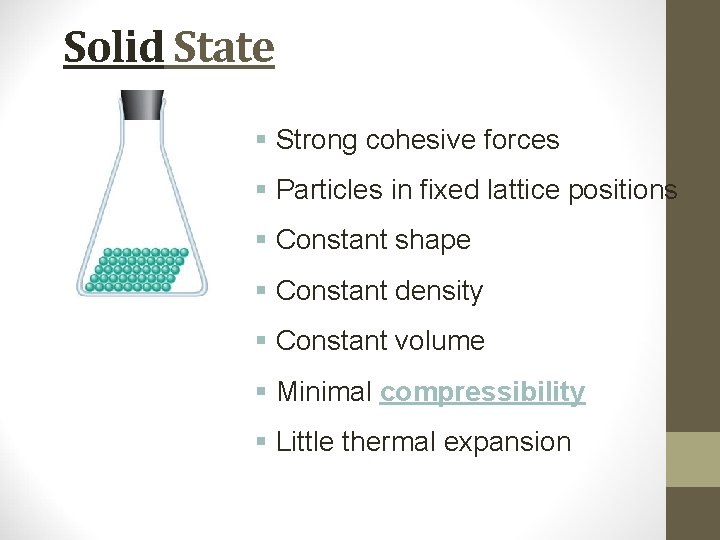

Solid State § Strong cohesive forces § Particles in fixed lattice positions § Constant shape § Constant density § Constant volume § Minimal compressibility § Little thermal expansion

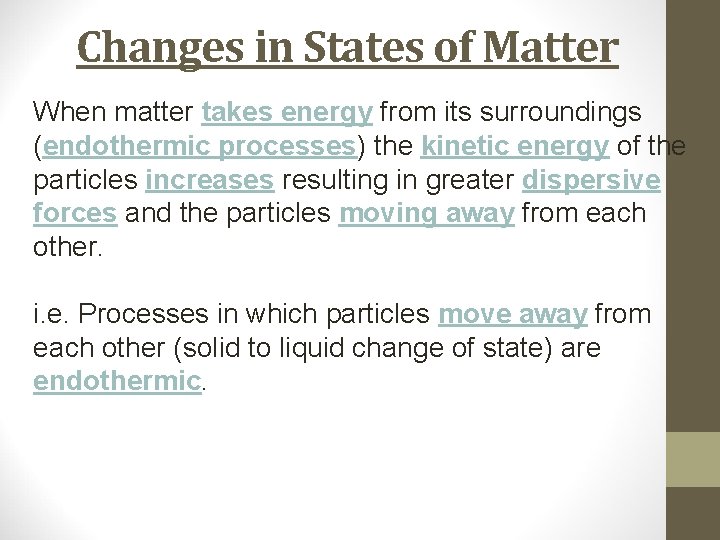

Changes in States of Matter When matter takes energy from its surroundings (endothermic processes) the kinetic energy of the particles increases resulting in greater dispersive forces and the particles moving away from each other. i. e. Processes in which particles move away from each other (solid to liquid change of state) are endothermic.

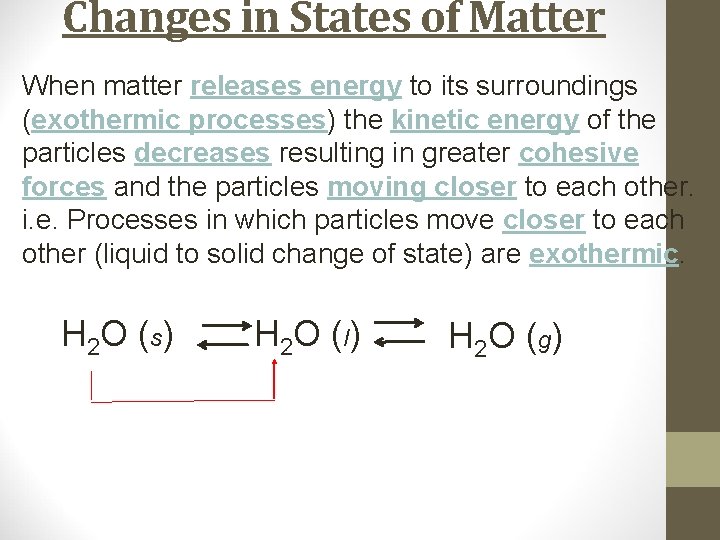

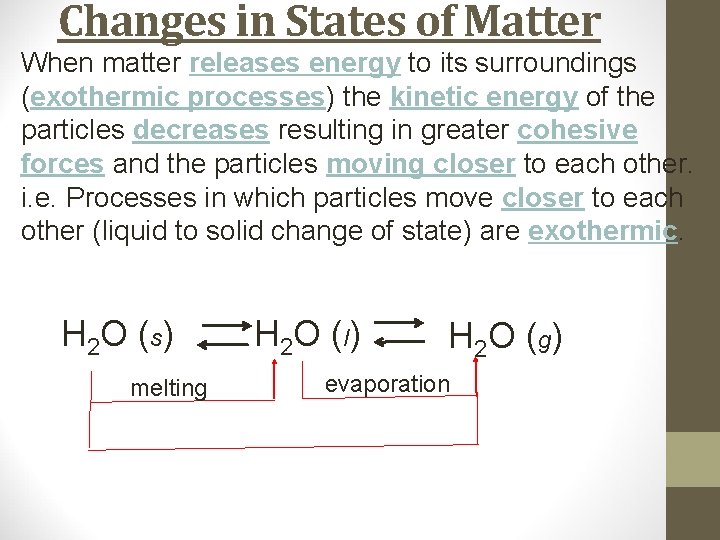

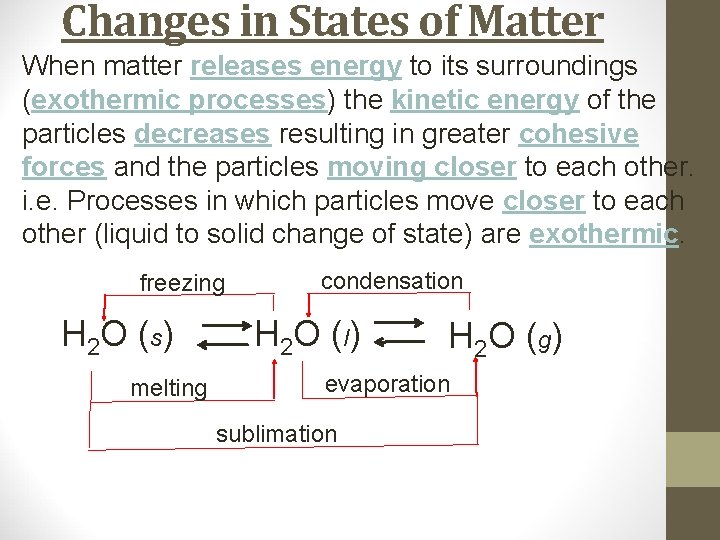

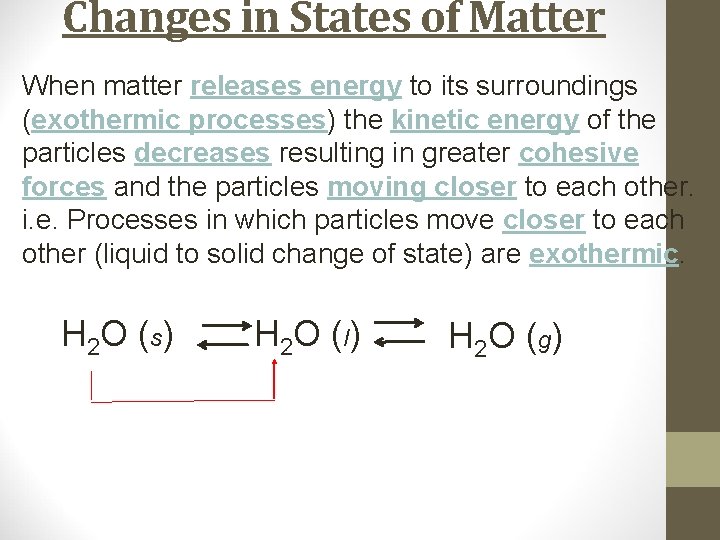

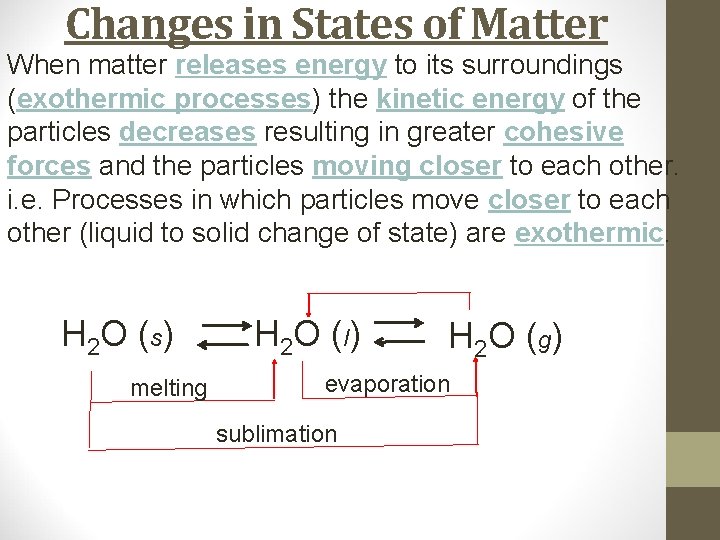

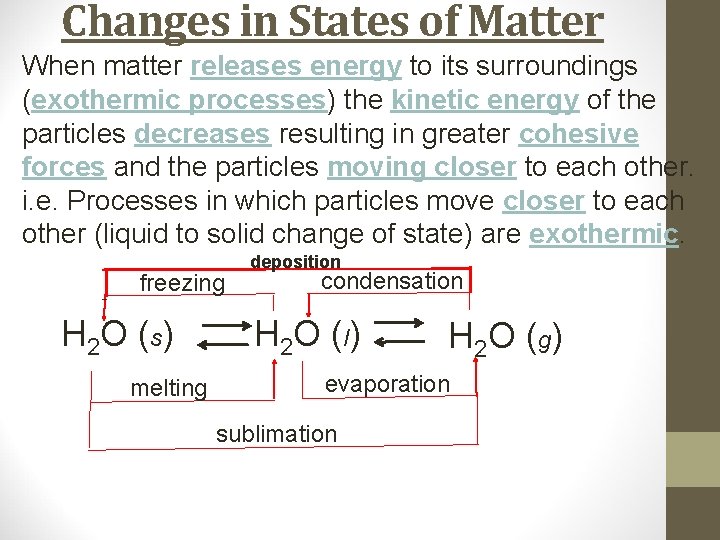

Changes in States of Matter When matter releases energy to its surroundings (exothermic processes) the kinetic energy of the particles decreases resulting in greater cohesive forces and the particles moving closer to each other. i. e. Processes in which particles move closer to each other (liquid to solid change of state) are exothermic. H 2 O (s) H 2 O ( l) H 2 O ( g)

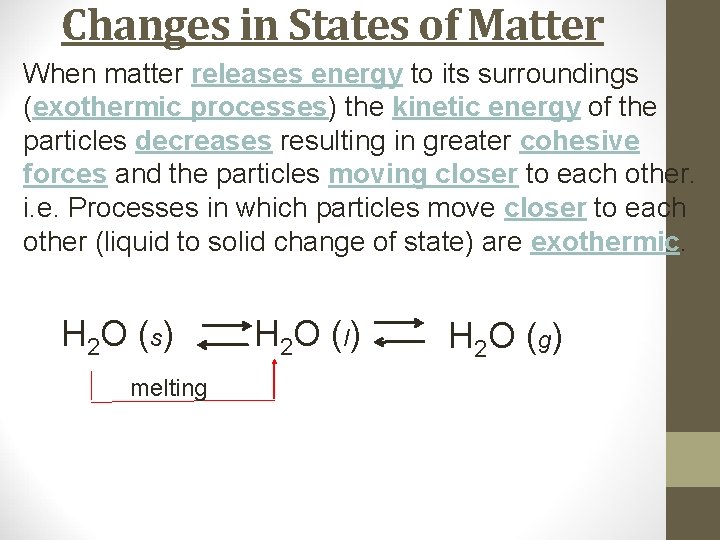

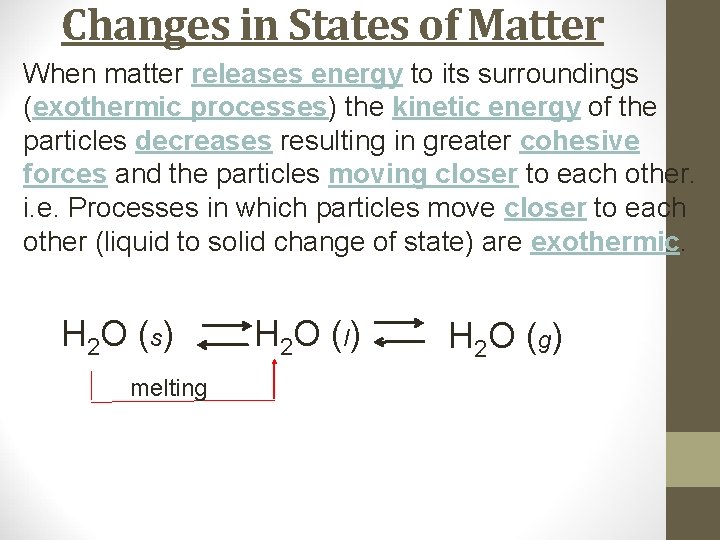

Changes in States of Matter When matter releases energy to its surroundings (exothermic processes) the kinetic energy of the particles decreases resulting in greater cohesive forces and the particles moving closer to each other. i. e. Processes in which particles move closer to each other (liquid to solid change of state) are exothermic. H 2 O (s) melting H 2 O ( l) H 2 O ( g)

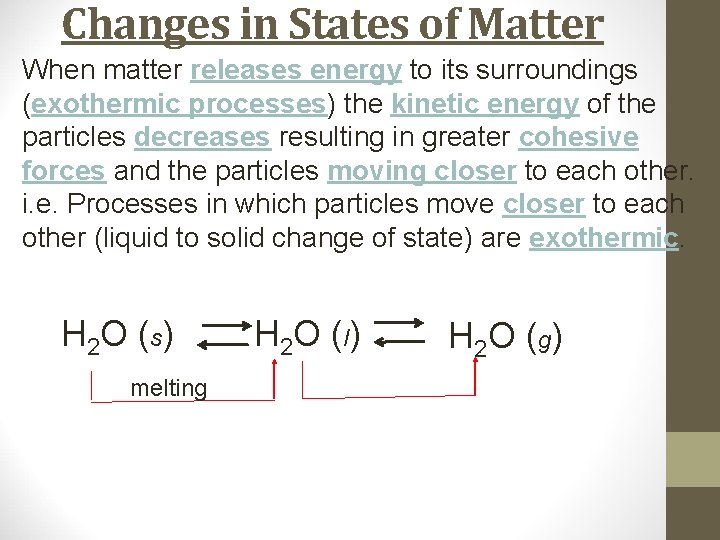

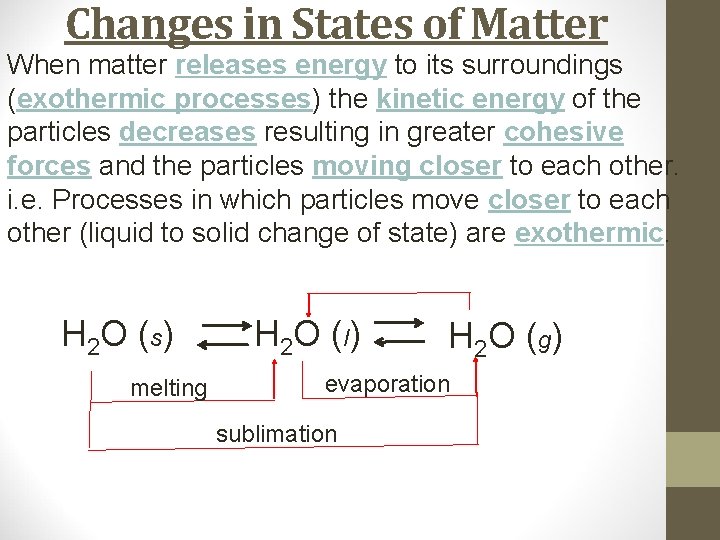

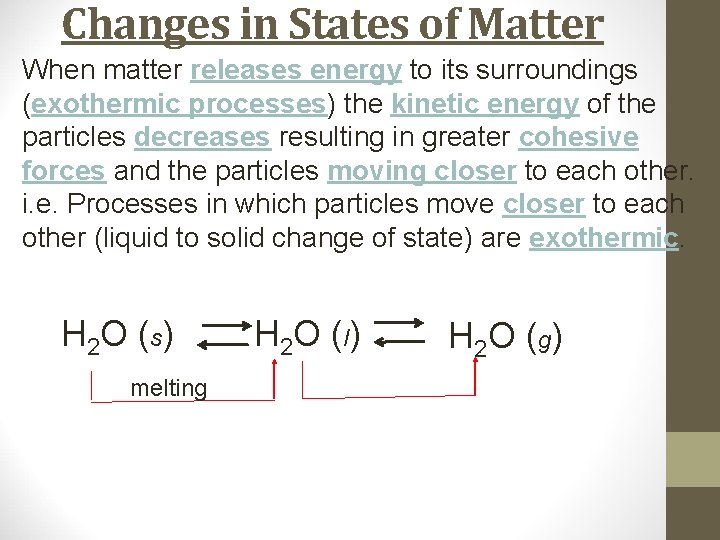

Changes in States of Matter When matter releases energy to its surroundings (exothermic processes) the kinetic energy of the particles decreases resulting in greater cohesive forces and the particles moving closer to each other. i. e. Processes in which particles move closer to each other (liquid to solid change of state) are exothermic. H 2 O (s) melting H 2 O ( l) H 2 O ( g)

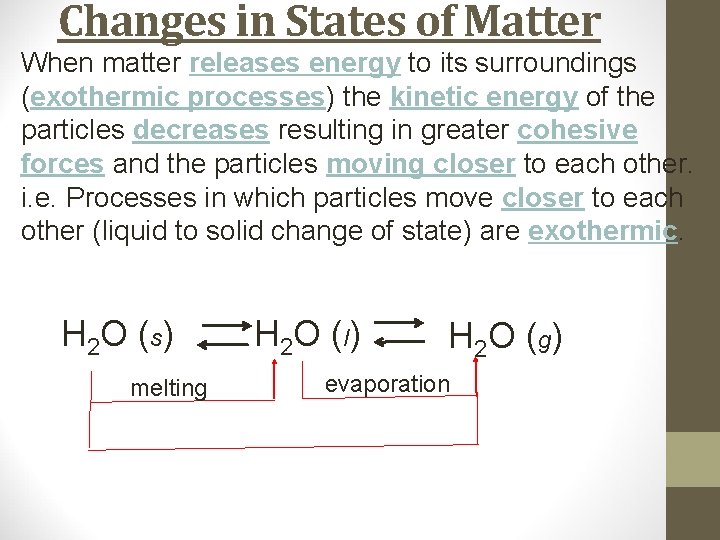

Changes in States of Matter When matter releases energy to its surroundings (exothermic processes) the kinetic energy of the particles decreases resulting in greater cohesive forces and the particles moving closer to each other. i. e. Processes in which particles move closer to each other (liquid to solid change of state) are exothermic. H 2 O (s) melting H 2 O ( l) H 2 O ( g) evaporation

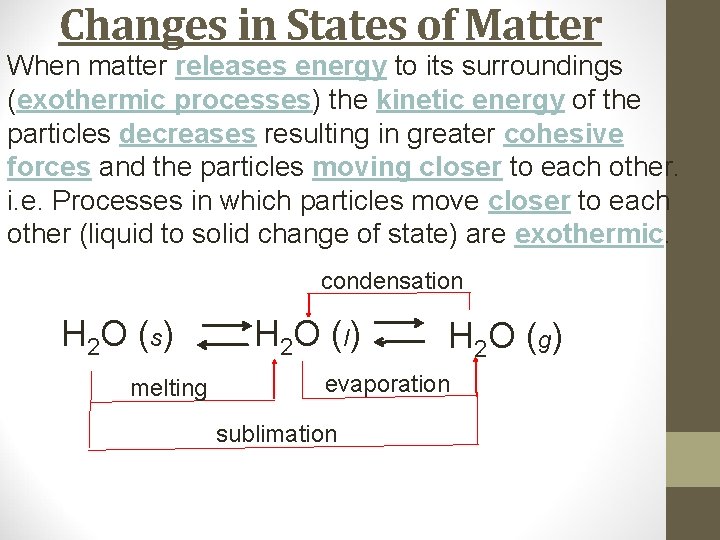

Changes in States of Matter When matter releases energy to its surroundings (exothermic processes) the kinetic energy of the particles decreases resulting in greater cohesive forces and the particles moving closer to each other. i. e. Processes in which particles move closer to each other (liquid to solid change of state) are exothermic. H 2 O (s) melting H 2 O ( l) H 2 O ( g) evaporation sublimation

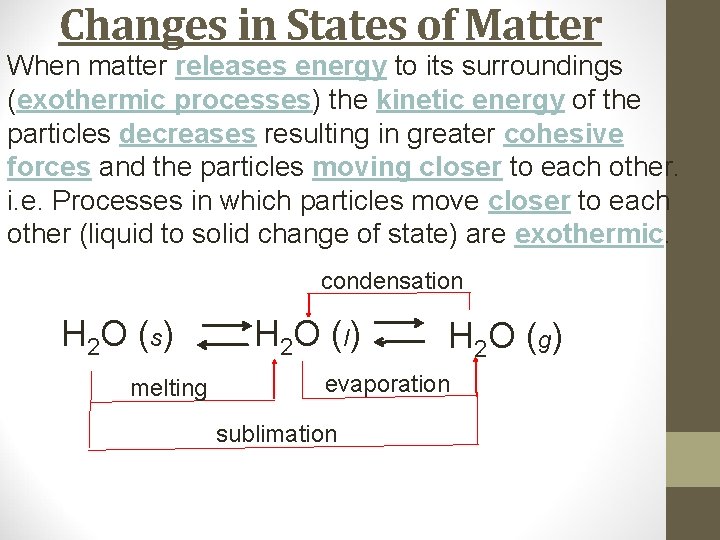

Changes in States of Matter When matter releases energy to its surroundings (exothermic processes) the kinetic energy of the particles decreases resulting in greater cohesive forces and the particles moving closer to each other. i. e. Processes in which particles move closer to each other (liquid to solid change of state) are exothermic. condensation H 2 O (s) melting H 2 O ( l) H 2 O ( g) evaporation sublimation

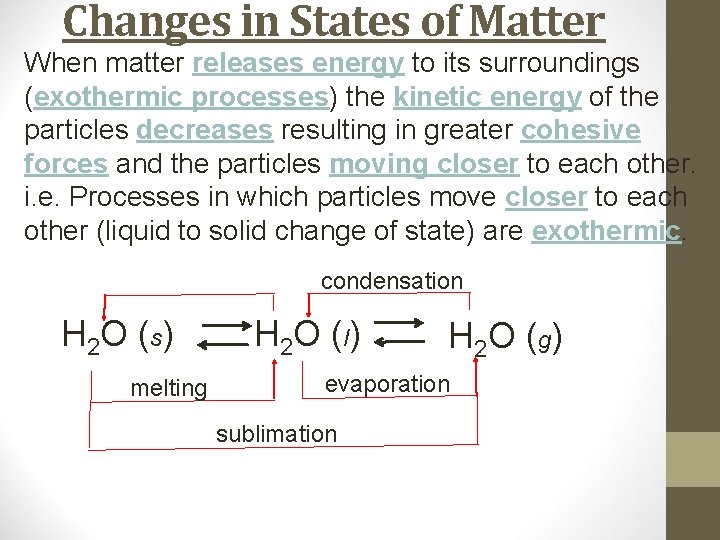

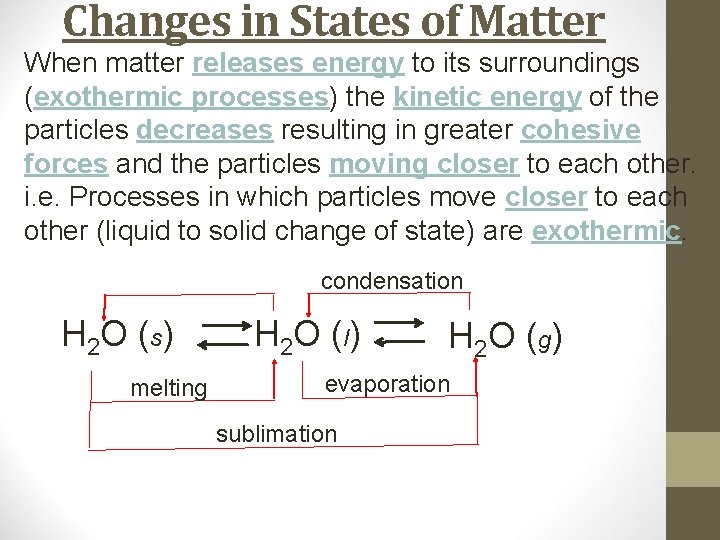

Changes in States of Matter When matter releases energy to its surroundings (exothermic processes) the kinetic energy of the particles decreases resulting in greater cohesive forces and the particles moving closer to each other. i. e. Processes in which particles move closer to each other (liquid to solid change of state) are exothermic. condensation H 2 O (s) melting H 2 O ( l) H 2 O ( g) evaporation sublimation

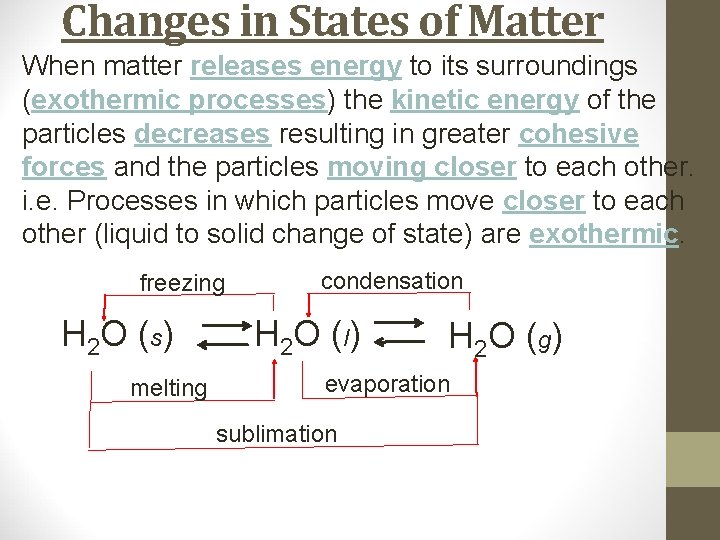

Changes in States of Matter When matter releases energy to its surroundings (exothermic processes) the kinetic energy of the particles decreases resulting in greater cohesive forces and the particles moving closer to each other. i. e. Processes in which particles move closer to each other (liquid to solid change of state) are exothermic. freezing H 2 O (s) melting condensation H 2 O ( l) H 2 O ( g) evaporation sublimation

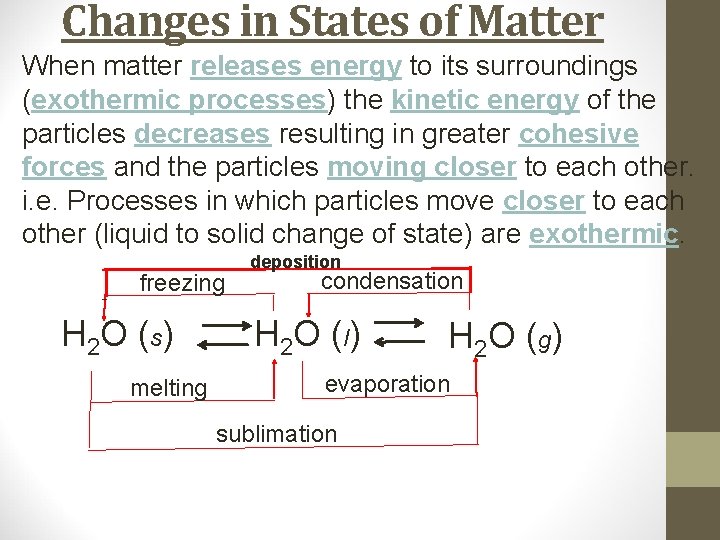

Changes in States of Matter When matter releases energy to its surroundings (exothermic processes) the kinetic energy of the particles decreases resulting in greater cohesive forces and the particles moving closer to each other. i. e. Processes in which particles move closer to each other (liquid to solid change of state) are exothermic. freezing H 2 O (s) melting deposition condensation H 2 O ( l) H 2 O ( g) evaporation sublimation

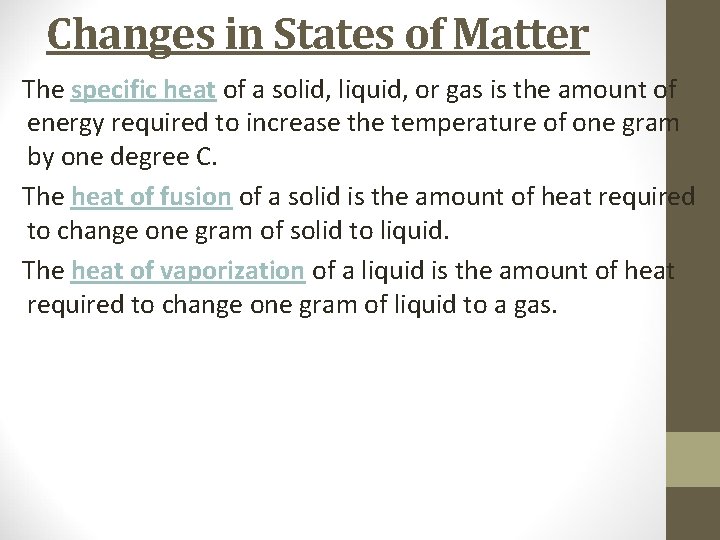

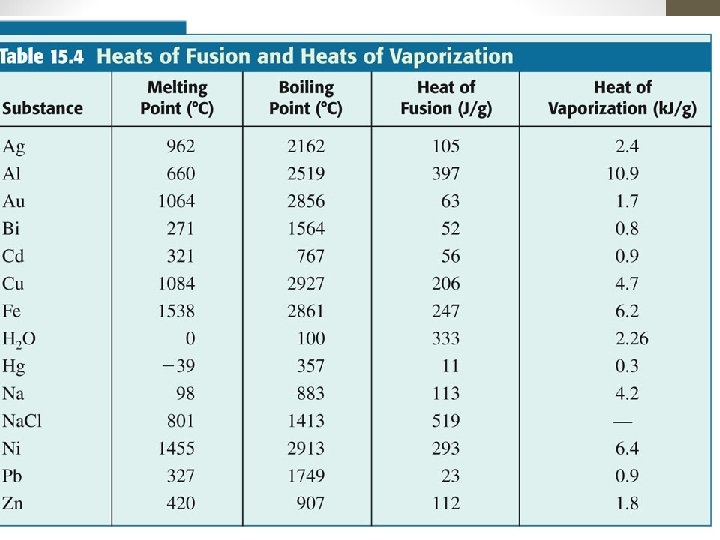

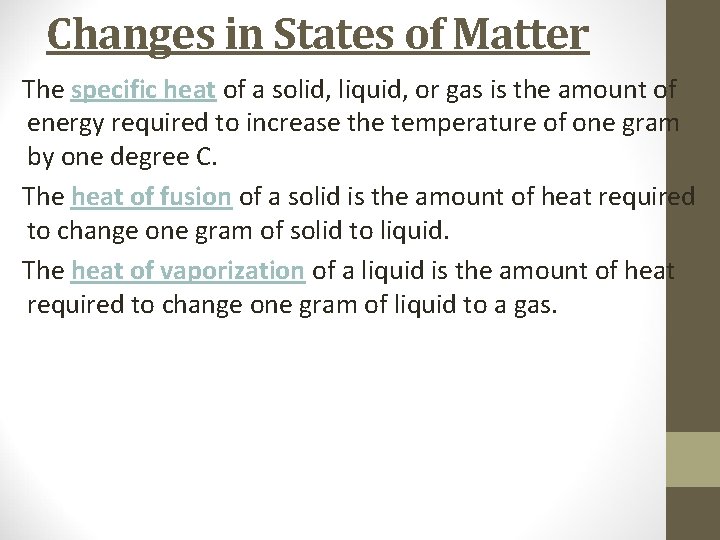

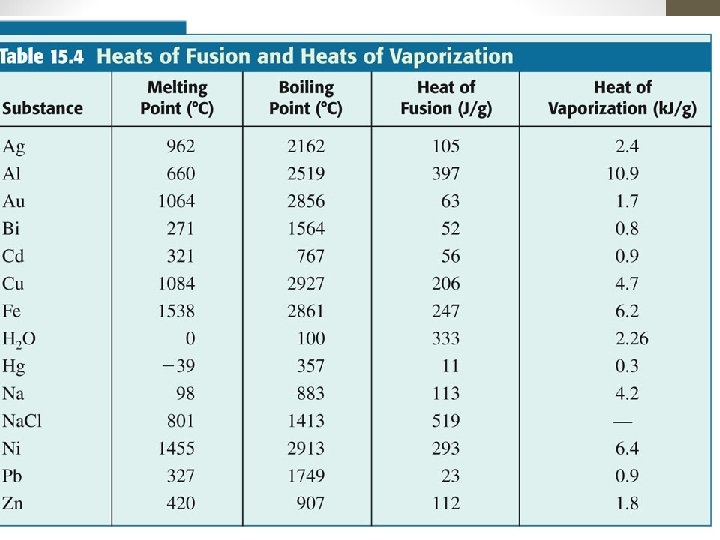

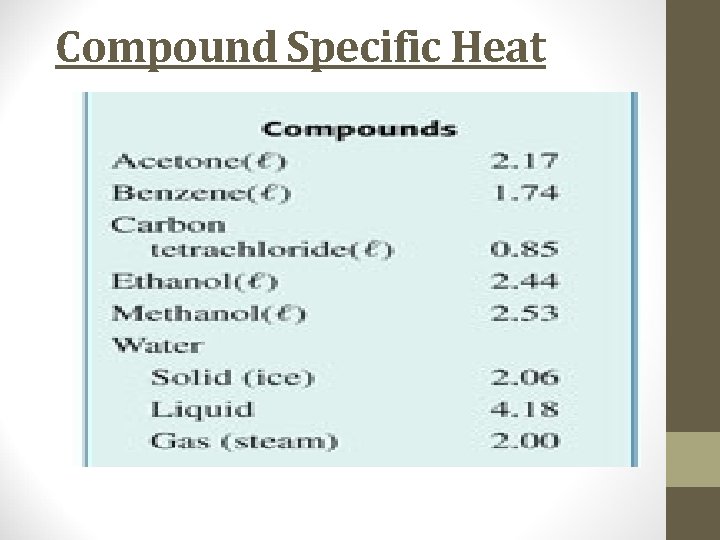

Changes in States of Matter The specific heat of a solid, liquid, or gas is the amount of energy required to increase the temperature of one gram by one degree C. The heat of fusion of a solid is the amount of heat required to change one gram of solid to liquid. The heat of vaporization of a liquid is the amount of heat required to change one gram of liquid to a gas.

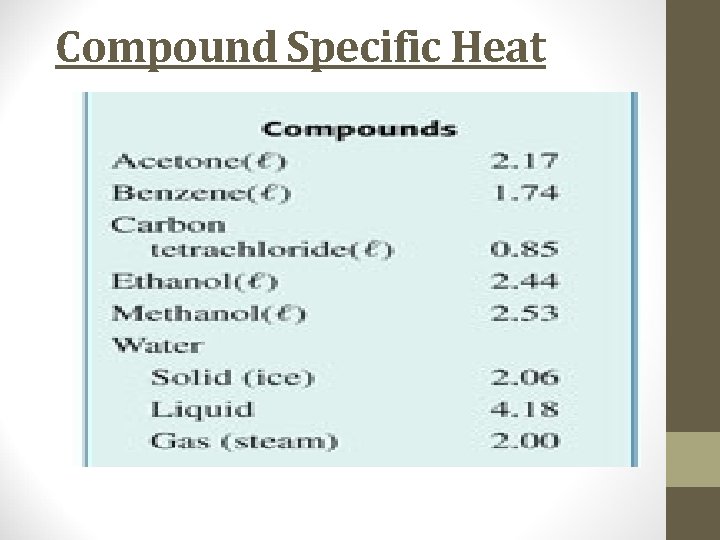

Compound Specific Heat

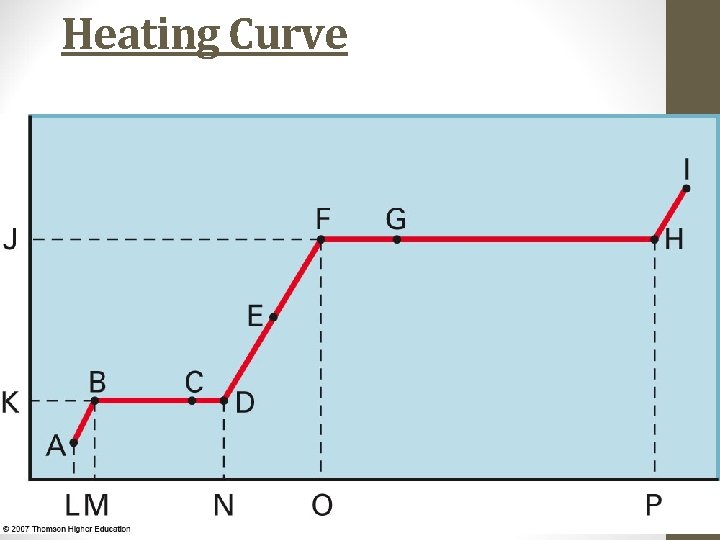

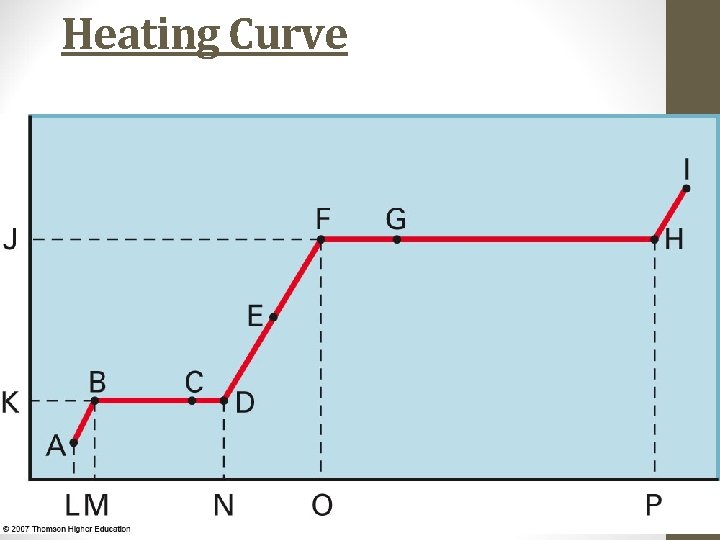

Heating Curve

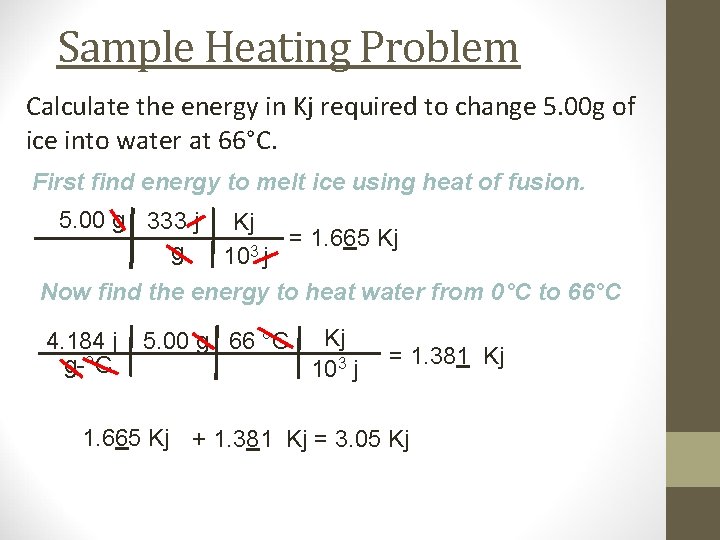

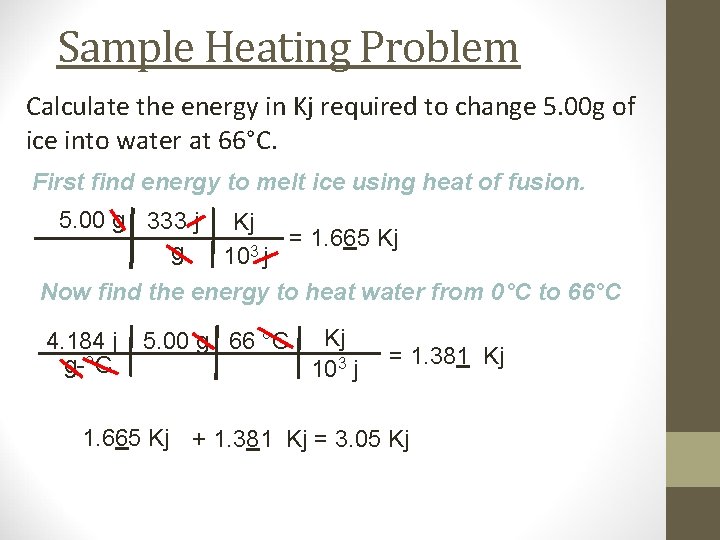

Sample Heating Problem Calculate the energy in Kj required to change 5. 00 g of ice into water at 66°C. First find energy to melt ice using heat of fusion. 5. 00 g 333 j g Kj = 1. 665 Kj 3 10 j Now find the energy to heat water from 0°C to 66°C 4. 184 j g-°C 5. 00 g 66 °C Kj 103 j = 1. 381 Kj 1. 665 Kj + 1. 381 Kj = 3. 05 Kj

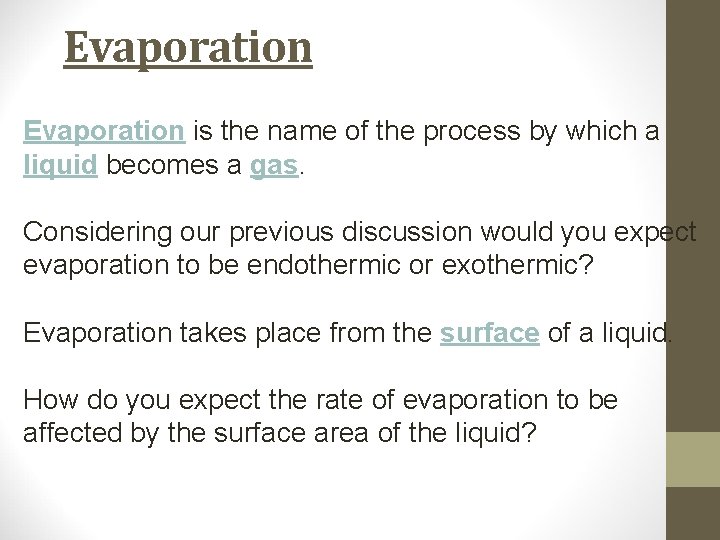

Evaporation is the name of the process by which a liquid becomes a gas. Considering our previous discussion would you expect evaporation to be endothermic or exothermic? Evaporation takes place from the surface of a liquid. How do you expect the rate of evaporation to be affected by the surface area of the liquid?

Vapor Pressure We can define the vapor pressure of a liquid as: “the pressure exerted by a vapor that is in equilibrium with its liquid. ” This is a little confusing so lets take sometime to explain.

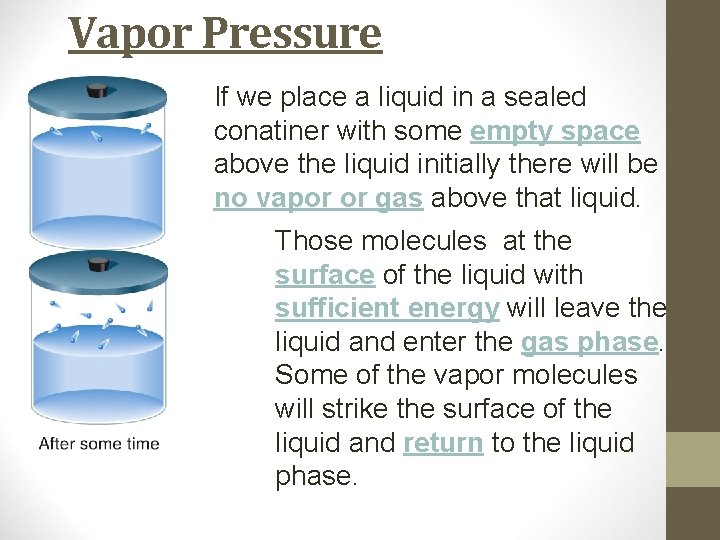

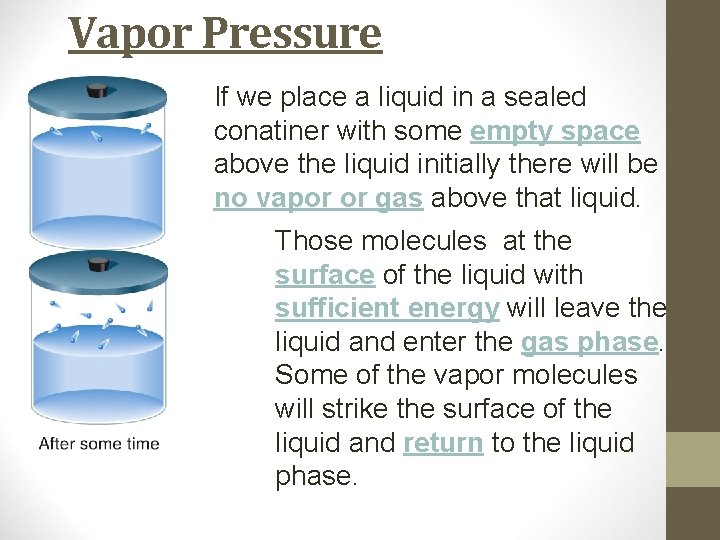

Vapor Pressure If we place a liquid in a sealed conatiner with some empty space above the liquid initially there will be no vapor or gas above that liquid. Those molecules at the surface of the liquid with sufficient energy will leave the liquid and enter the gas phase. Some of the vapor molecules will strike the surface of the liquid and return to the liquid phase.

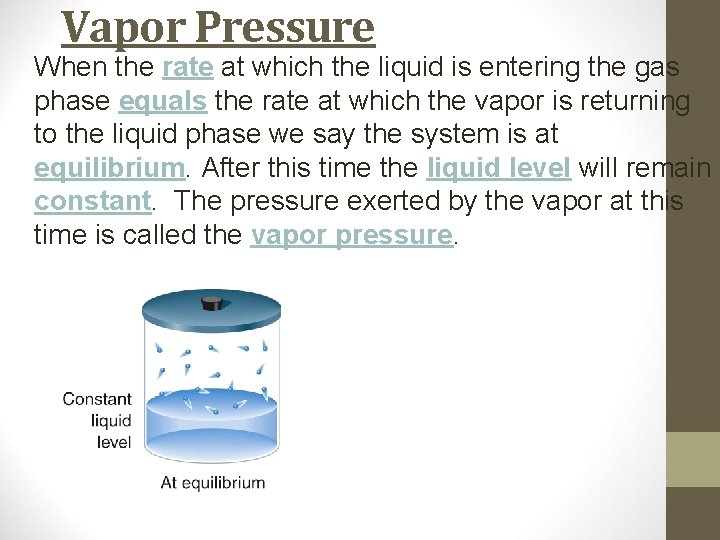

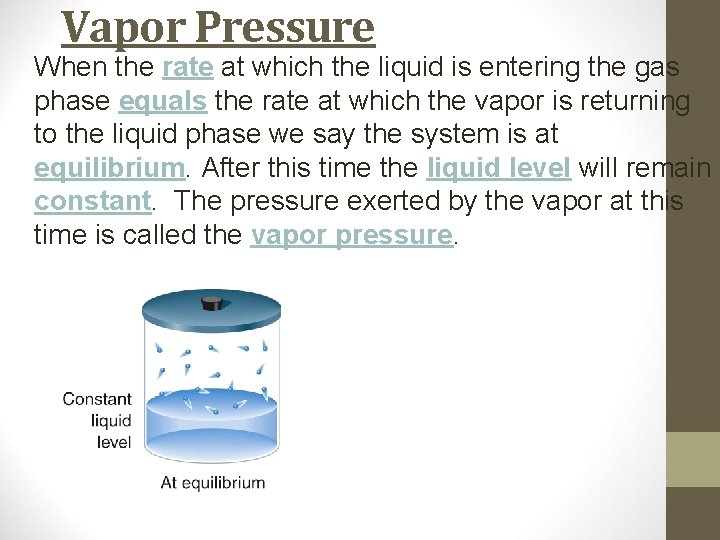

Vapor Pressure When the rate at which the liquid is entering the gas phase equals the rate at which the vapor is returning to the liquid phase we say the system is at equilibrium. After this time the liquid level will remain constant. The pressure exerted by the vapor at this time is called the vapor pressure.

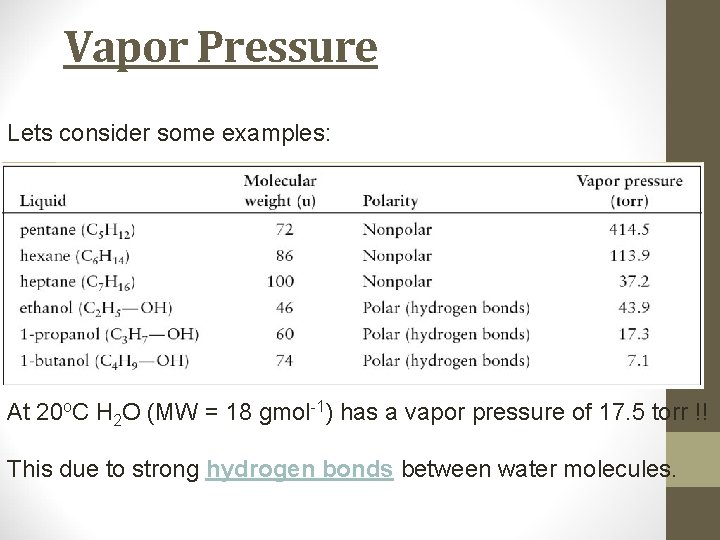

Vapor Pressure The vapor pressure of a liquid decreases with molecular mass. The vapor pressure of a increases with temperature. The vapor pressure of a liquid depends upon the chemical nature of the liquid. Those molecules that have strong intermolecular attractive forces have lower vapor pressures than expected for their molecular mass.

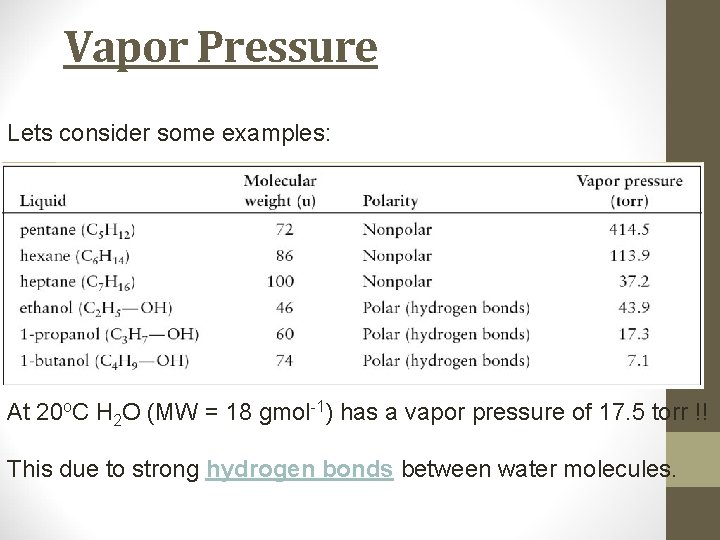

Vapor Pressure Lets consider some examples: At 20 o. C H 2 O (MW = 18 gmol-1) has a vapor pressure of 17. 5 torr !! This due to strong hydrogen bonds between water molecules.

Vapor Pressure As we increase the temperature the vapor pressure of a liquid increases. The temperature at which the vapor pressure equals the external pressure (atmospheric pressure) is called the boiling point. Bubbles of vapor with atmospheric pressure may form anywhere in the liquid and rise to the surface at the boiling point of a liquid. What is the effect of lowering the atmospheric pressure on the boiling point?

Vapor Pressure As we increase the temperature the vapor pressure of a liquid increases. The temperature at which the vapor pressure equals the external pressure (atmospheric pressure) is called the boiling point. Bubbles of vapor with atmospheric pressure may form anywhere in the liquid and rise to the surface at the boiling point of a liquid. What is the effect of lowering the atmospheric pressure on the boiling point? Lowering of the boiling point, thus food takes longer to cook at higher elevations.

Boyles and Charles Law

F. STP Standard Temperature & Pressure 0°C 1 atm -OR- 273 K 101. 325 k. Pa

CHARLE GAYLUSSAC Ch. 12 - Gases

A. Boyle’s Law PV = k P V

A. Boyle’s Law • The pressure and volume of a gas are inversely related • at constant mass & temp PV = k P V

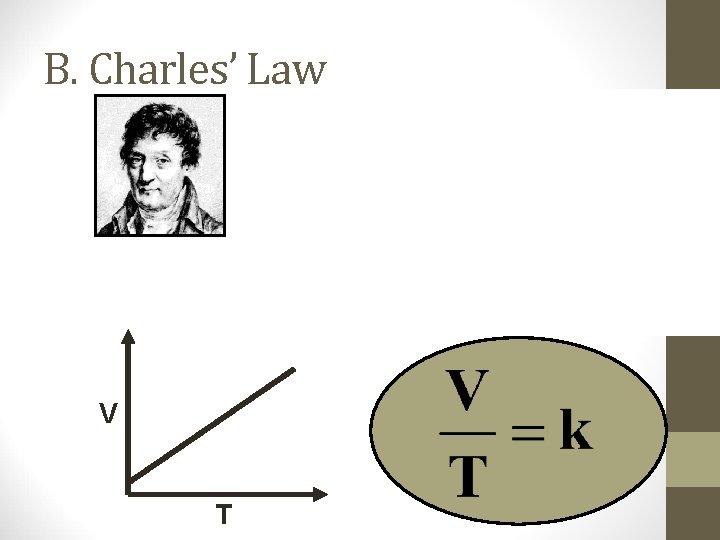

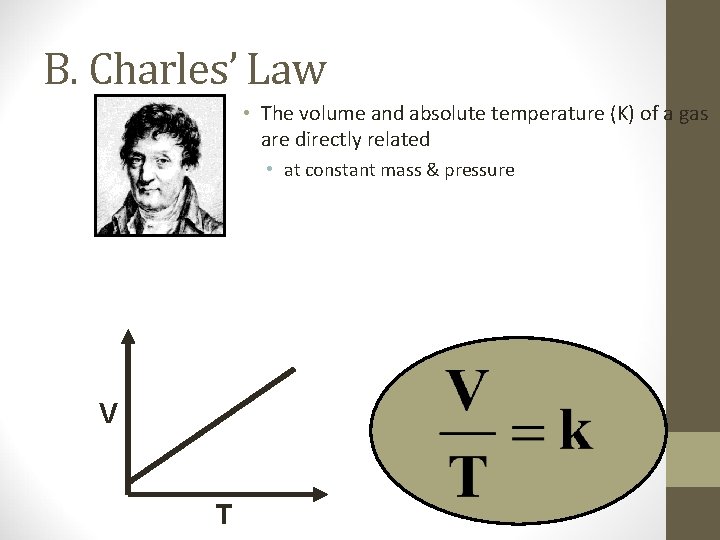

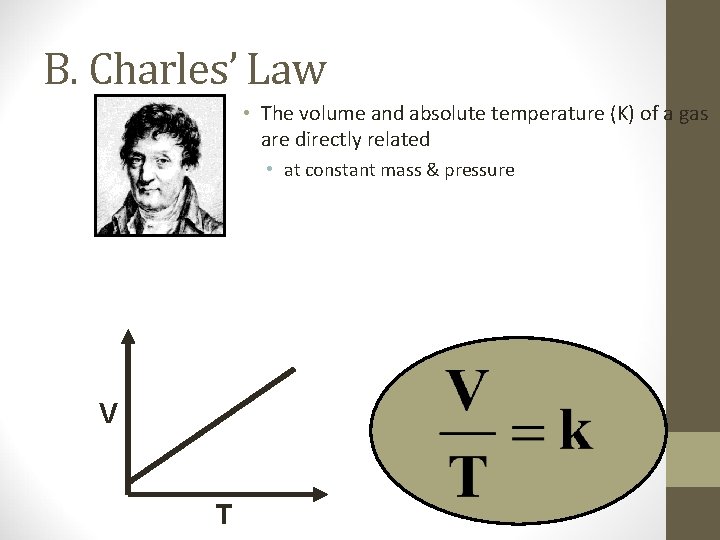

B. Charles’ Law V T

B. Charles’ Law • The volume and absolute temperature (K) of a gas are directly related • at constant mass & pressure V T

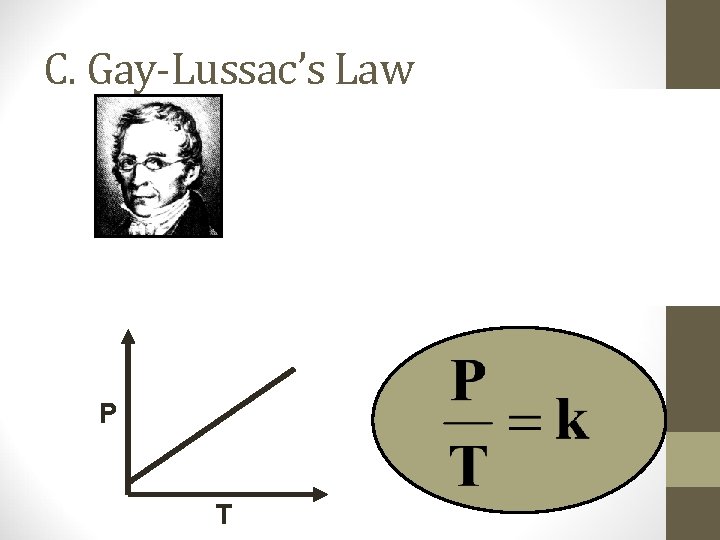

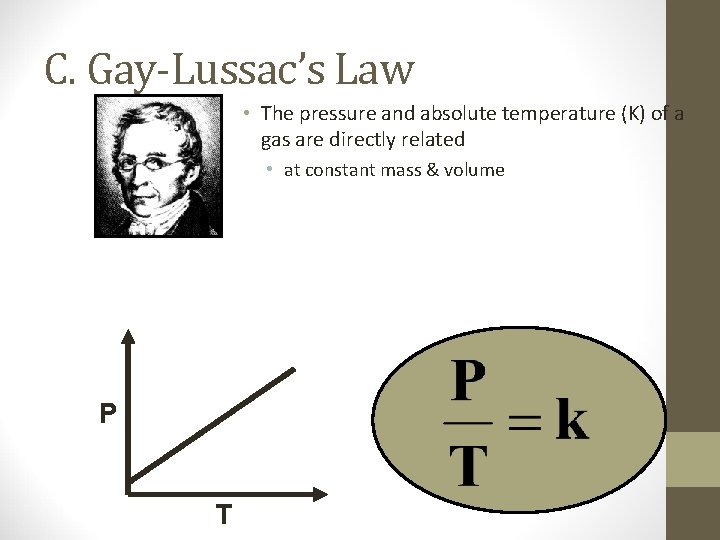

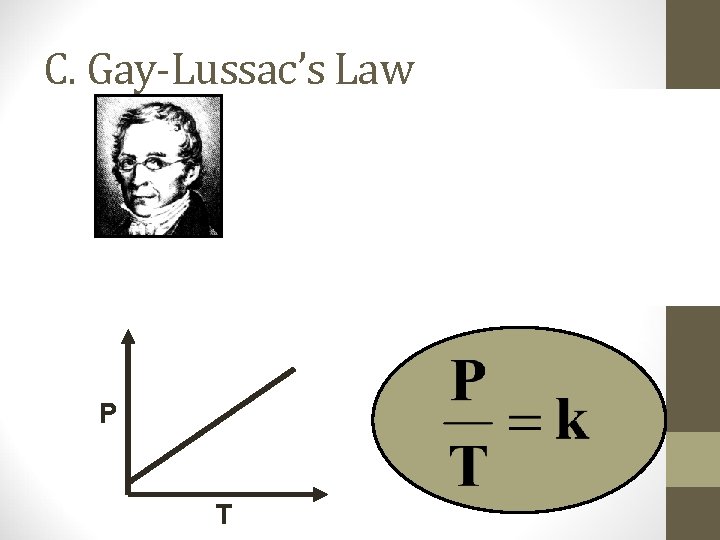

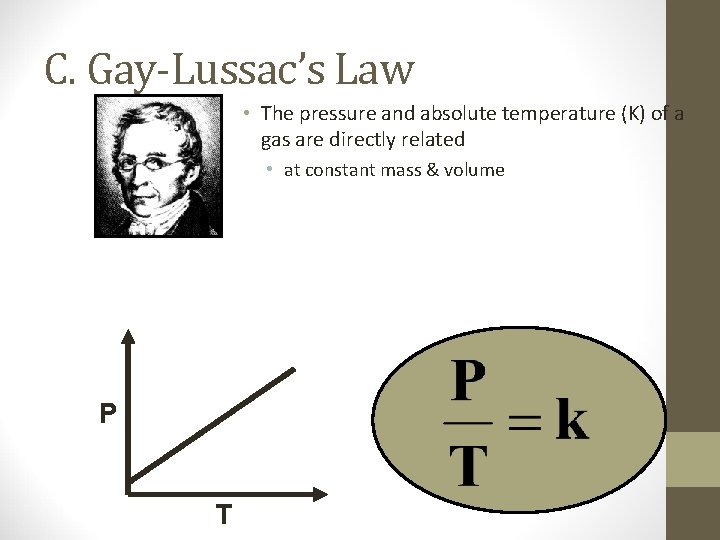

C. Gay-Lussac’s Law P T

C. Gay-Lussac’s Law • The pressure and absolute temperature (K) of a gas are directly related • at constant mass & volume P T

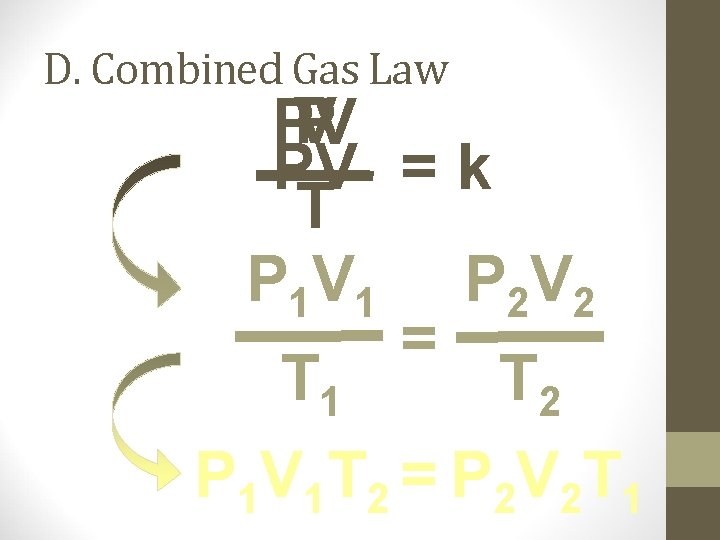

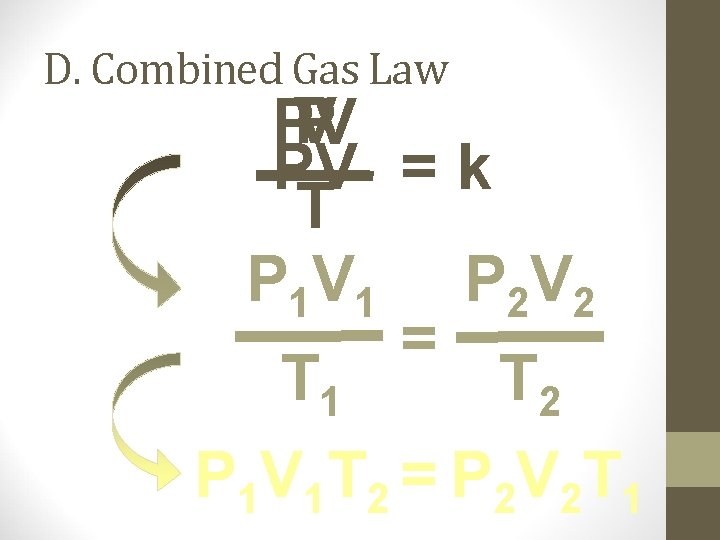

D. Combined Gas Law P V PV PV = k T P 1 V 1 P 2 V 2 = T 1 T 2 P 1 V 1 T 2 = P 2 V 2 T 1

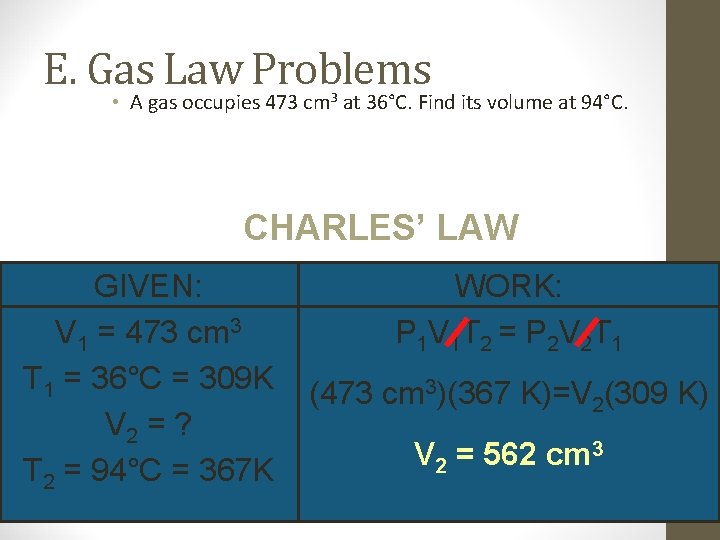

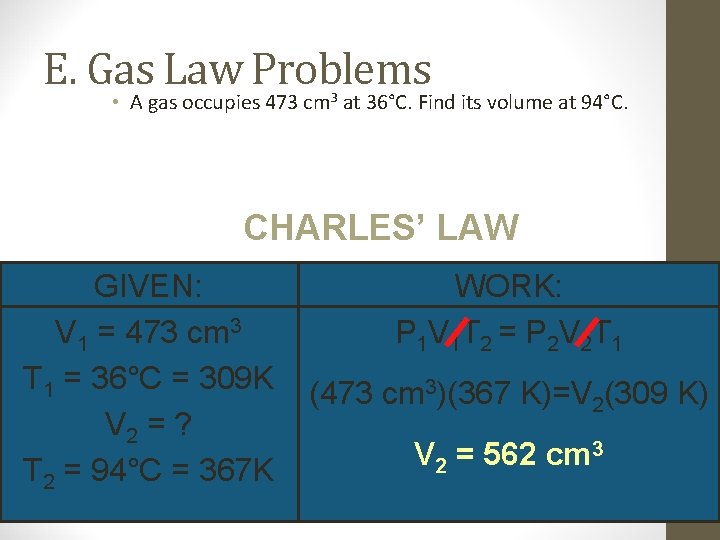

E. Gas Law Problems • A gas occupies 473 cm 3 at 36°C. Find its volume at 94°C. CHARLES’ LAW GIVEN: V 1 = 473 cm 3 T 1 = 36°C = 309 K V 2 = ? T 2 = 94°C = 367 K WORK: P 1 V 1 T 2 = P 2 V 2 T 1 (473 cm 3)(367 K)=V 2(309 K) V 2 = 562 cm 3

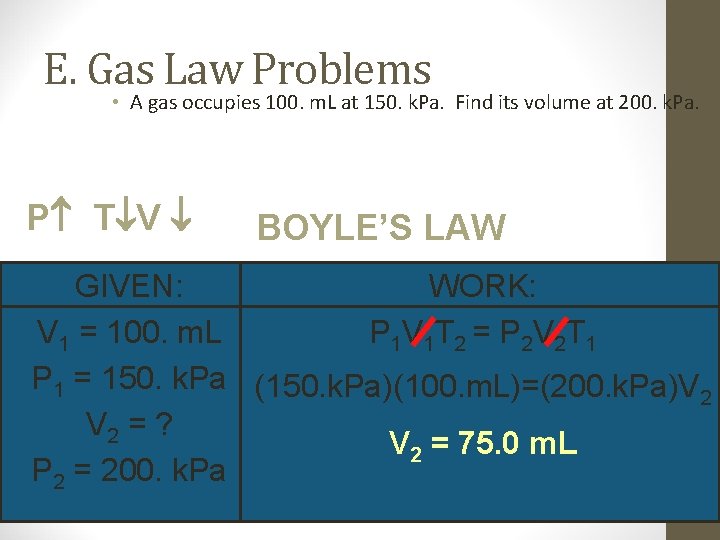

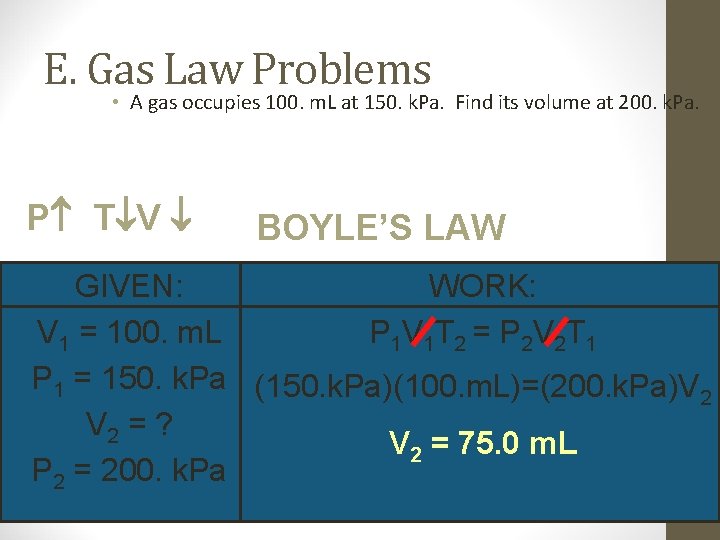

E. Gas Law Problems • A gas occupies 100. m. L at 150. k. Pa. Find its volume at 200. k. Pa. P T V BOYLE’S LAW GIVEN: WORK: V 1 = 100. m. L P 1 V 1 T 2 = P 2 V 2 T 1 P 1 = 150. k. Pa (150. k. Pa)(100. m. L)=(200. k. Pa)V 2 = ? V 2 = 75. 0 m. L P 2 = 200. k. Pa

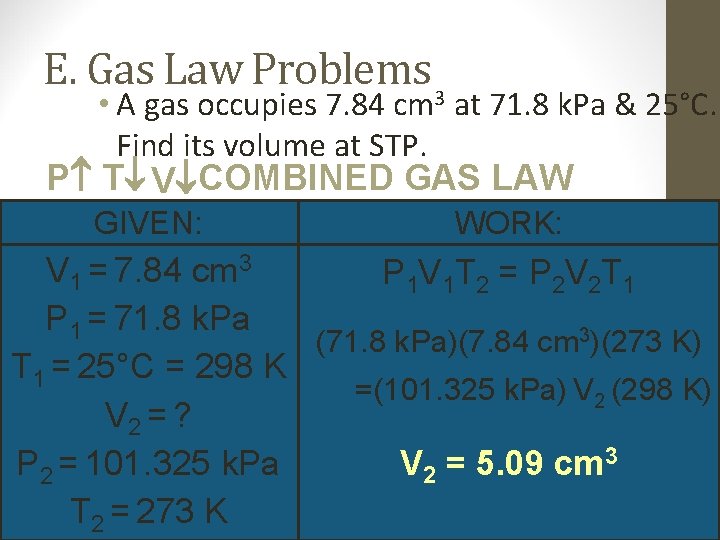

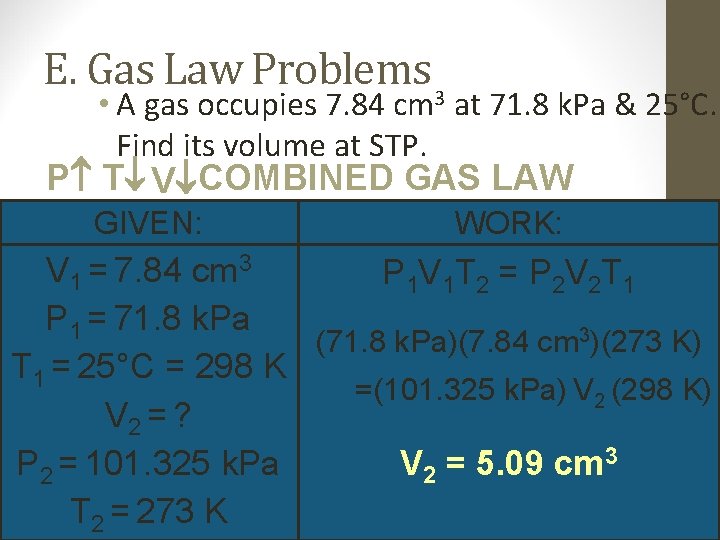

E. Gas Law Problems 3 • A gas occupies 7. 84 cm at 71. 8 k. Pa & 25°C. Find its volume at STP. P T V COMBINED GAS LAW GIVEN: WORK: V 1 = 7. 84 cm 3 P 1 V 1 T 2 = P 2 V 2 T 1 P 1 = 71. 8 k. Pa (71. 8 k. Pa)(7. 84 cm 3)(273 K) T 1 = 25°C = 298 K =(101. 325 k. Pa) V 2 (298 K) V 2 = ? V 2 = 5. 09 cm 3 P 2 = 101. 325 k. Pa T 2 = 273 K

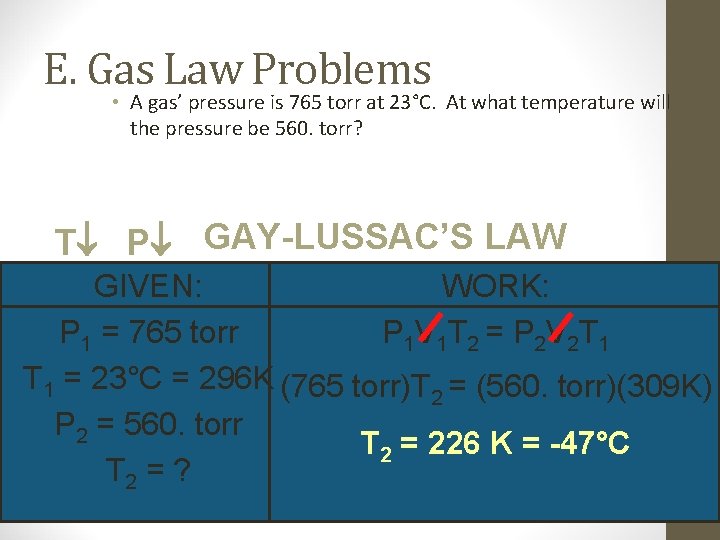

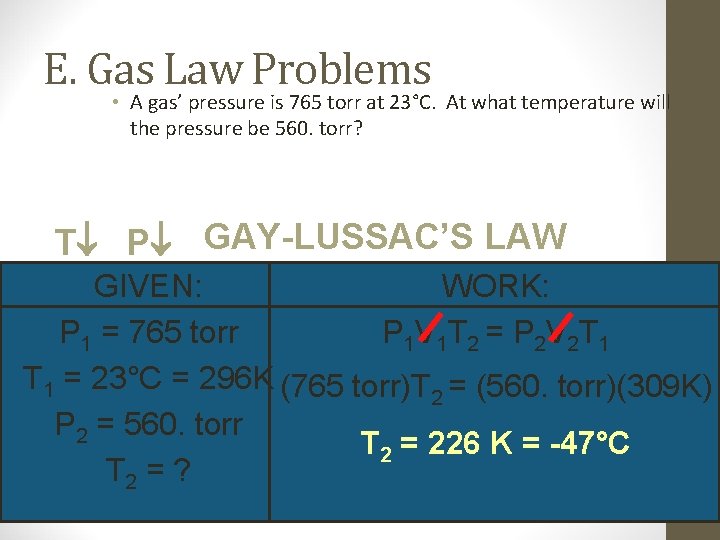

E. Gas Law Problems • A gas’ pressure is 765 torr at 23°C. At what temperature will the pressure be 560. torr? T P GAY-LUSSAC’S LAW GIVEN: WORK: P 1 = 765 torr P 1 V 1 T 2 = P 2 V 2 T 1 = 23°C = 296 K (765 torr)T 2 = (560. torr)(309 K) P 2 = 560. torr T 2 = 226 K = -47°C T 2 = ?

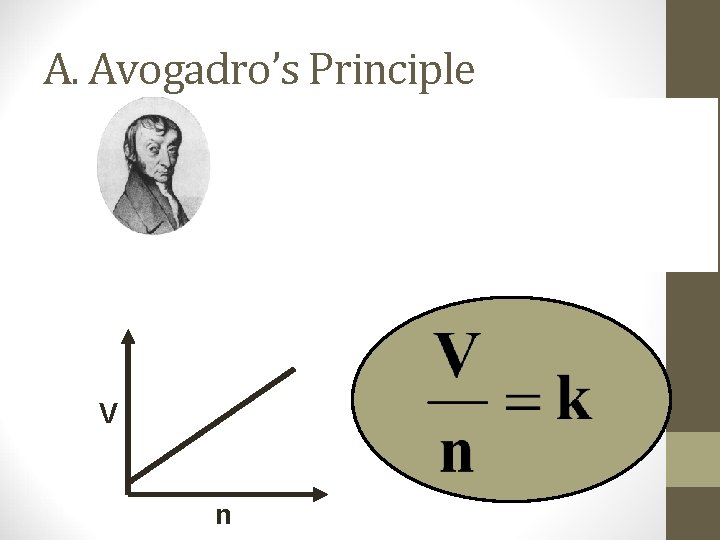

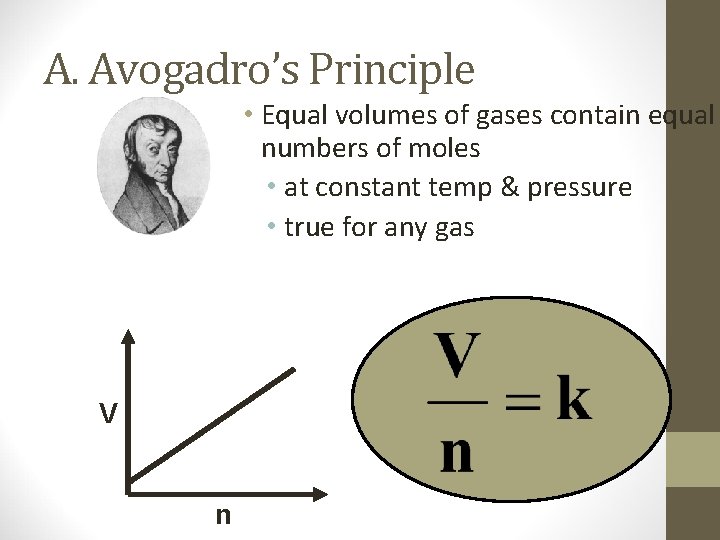

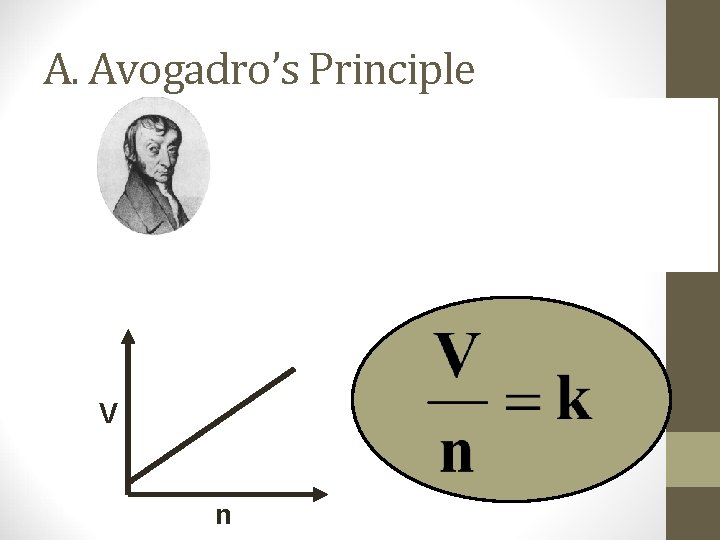

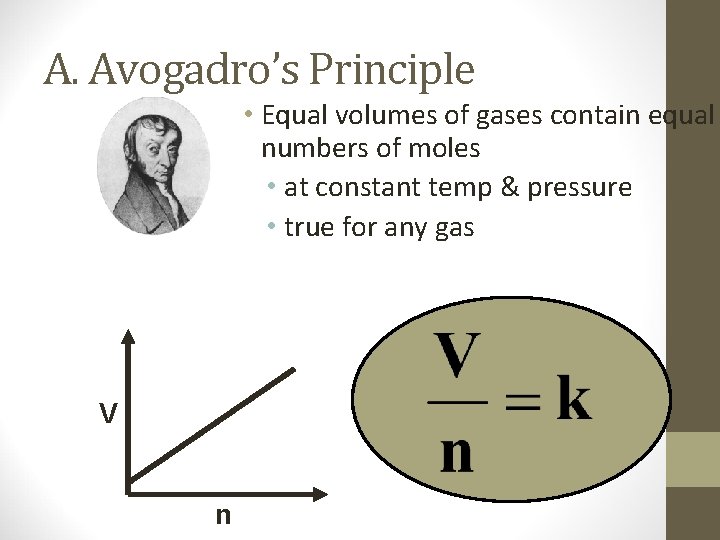

A. Avogadro’s Principle V n

A. Avogadro’s Principle • Equal volumes of gases contain equal numbers of moles • at constant temp & pressure • true for any gas V n

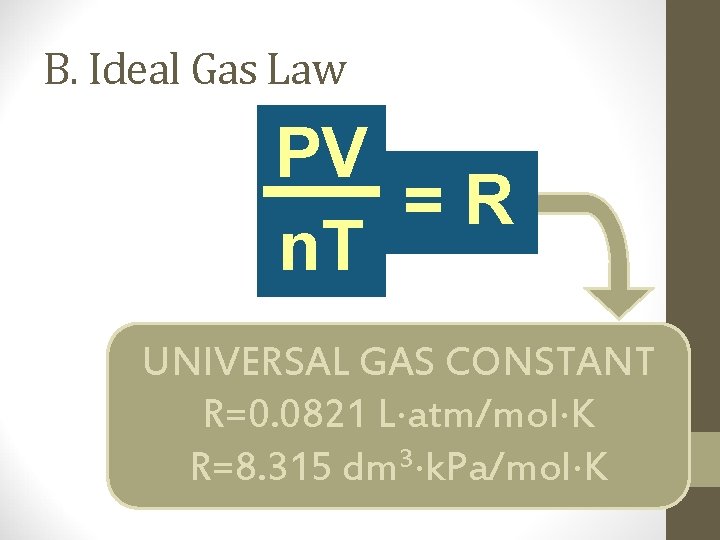

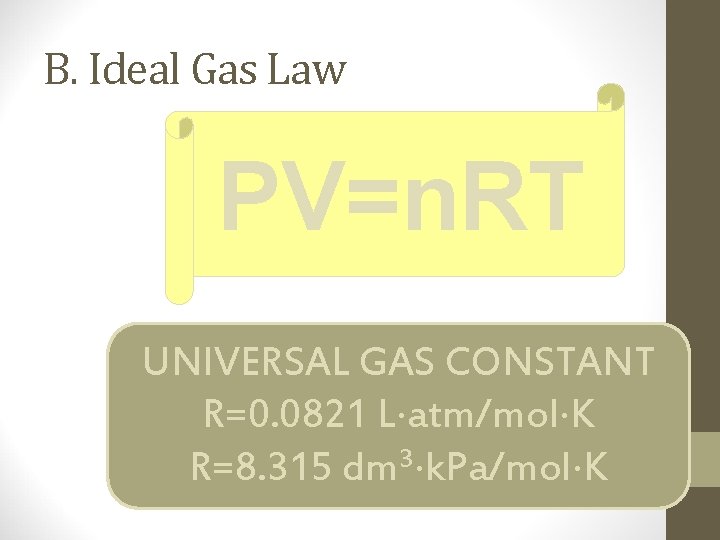

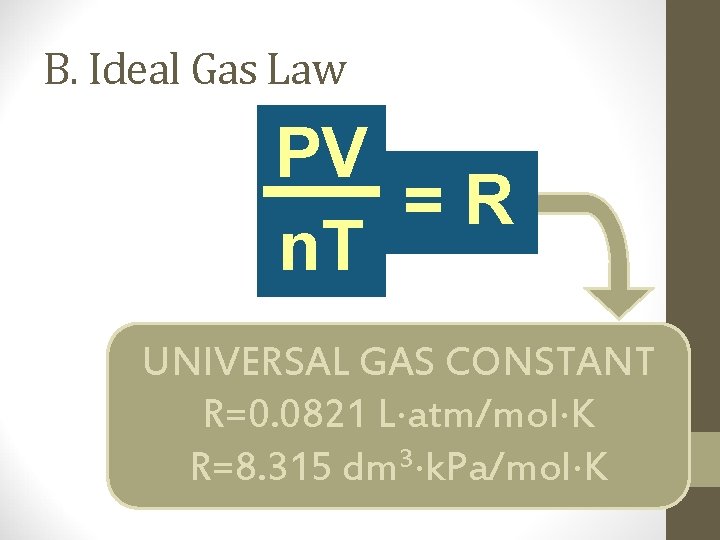

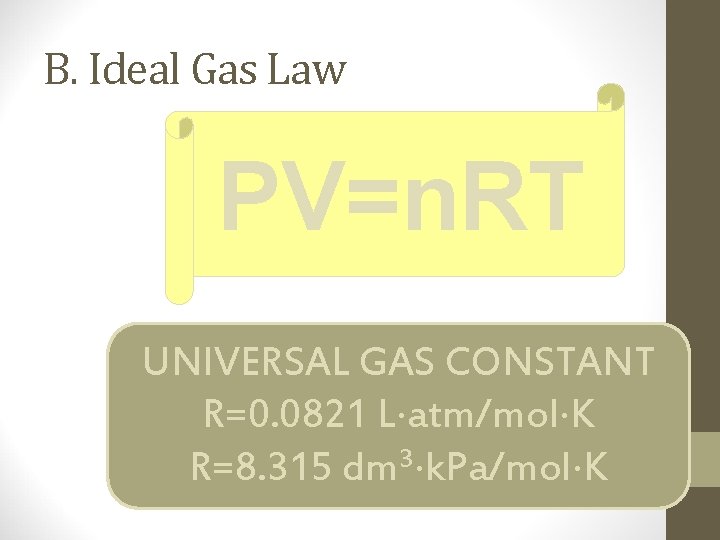

B. Ideal Gas Law V PV k =R n n. T T UNIVERSAL GAS CONSTANT R=0. 0821 L atm/mol K 3 R=8. 315 dm k. Pa/mol K

B. Ideal Gas Law PV=n. RT UNIVERSAL GAS CONSTANT R=0. 0821 L atm/mol K 3 R=8. 315 dm k. Pa/mol K

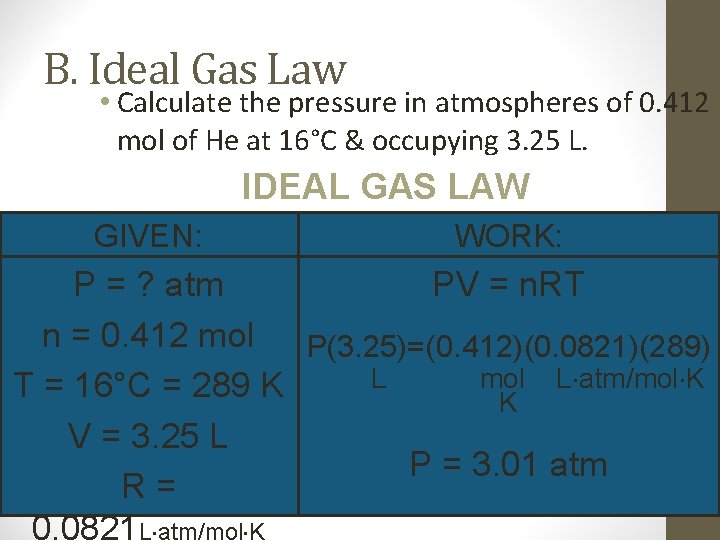

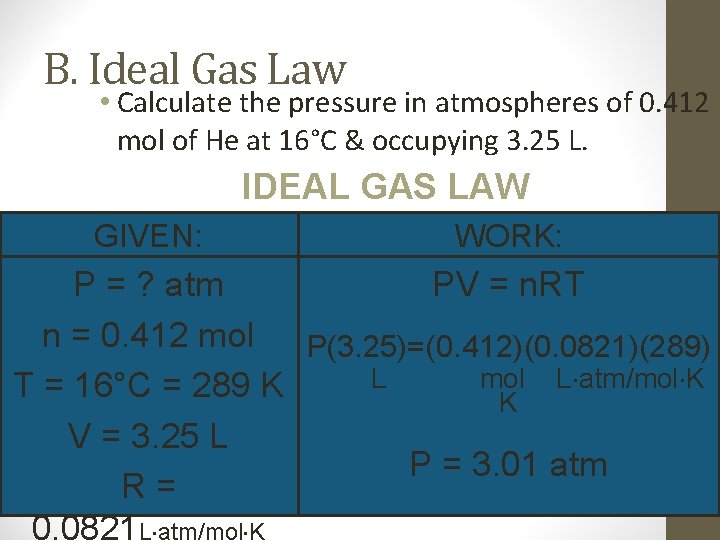

B. Ideal Gas Law • Calculate the pressure in atmospheres of 0. 412 mol of He at 16°C & occupying 3. 25 L. IDEAL GAS LAW GIVEN: WORK: P = ? atm PV = n. RT n = 0. 412 mol P(3. 25)=(0. 412)(0. 0821)(289) L mol L atm/mol K T = 16°C = 289 K K V = 3. 25 L P = 3. 01 atm R= 0. 0821 L atm/mol K

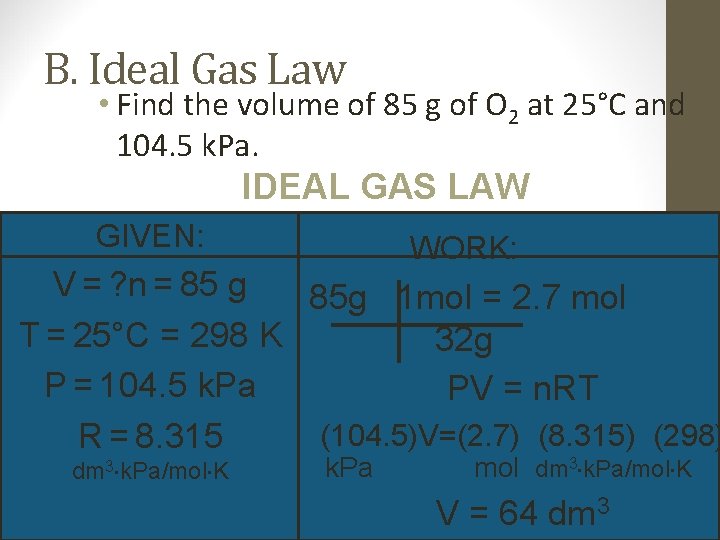

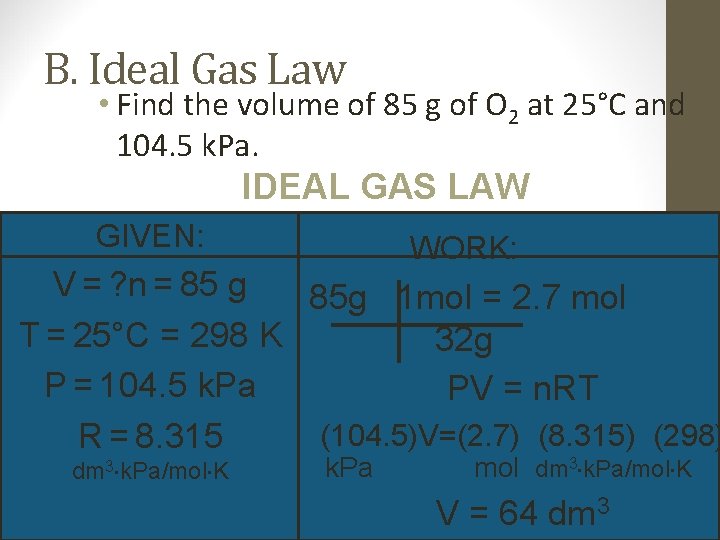

B. Ideal Gas Law • Find the volume of 85 g of O 2 at 25°C and 104. 5 k. Pa. IDEAL GAS LAW GIVEN: WORK: V = ? n = 85 g 85 g 1 mol = 2. 7 mol T = 25°C = 298 K 32 g P = 104. 5 k. Pa PV = n. RT (104. 5)V=(2. 7) (8. 315) (298) R = 8. 315 dm 3 k. Pa/mol K k. Pa mol dm 3 k. Pa/mol K V = 64 dm 3

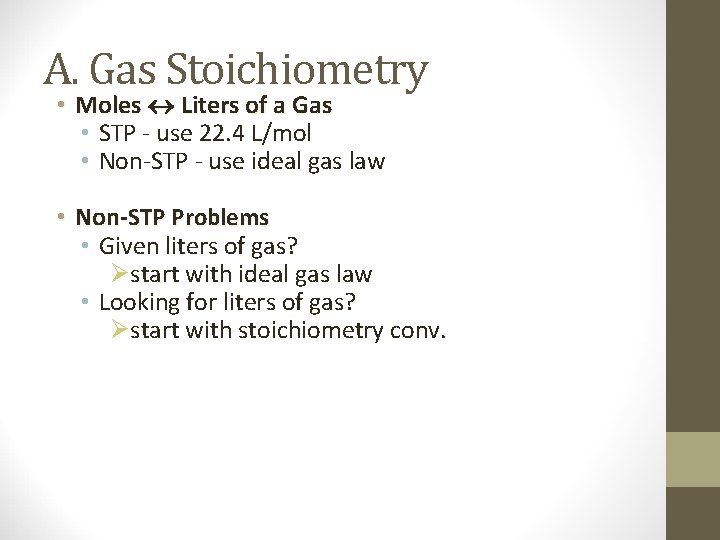

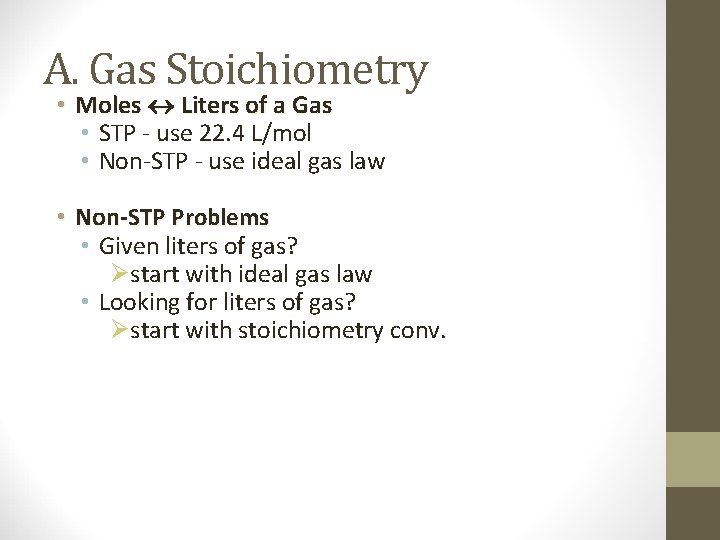

A. Gas Stoichiometry • Moles Liters of a Gas • STP - use 22. 4 L/mol • Non-STP - use ideal gas law • Non-STP Problems • Given liters of gas? Østart with ideal gas law • Looking for liters of gas? Østart with stoichiometry conv.

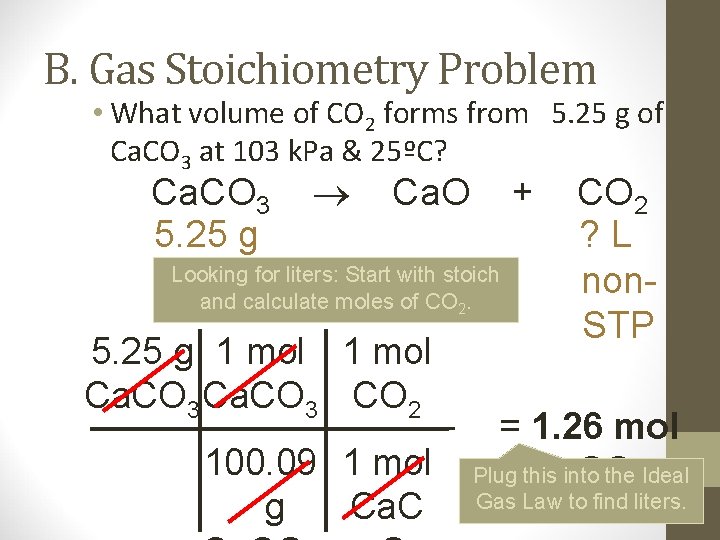

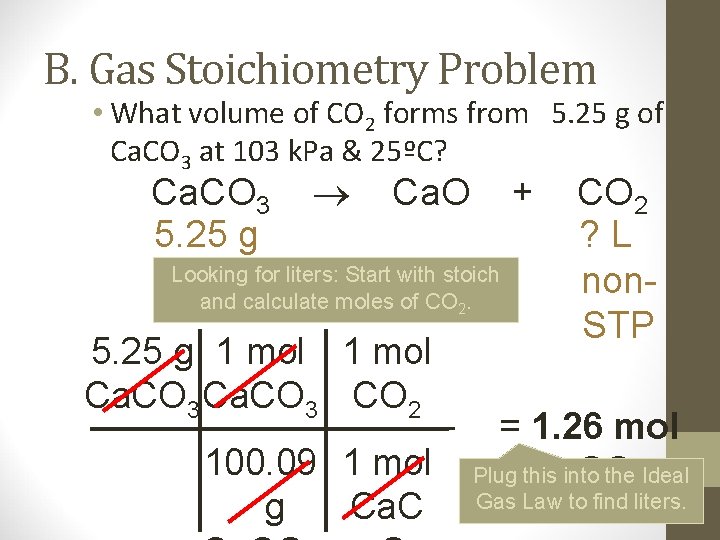

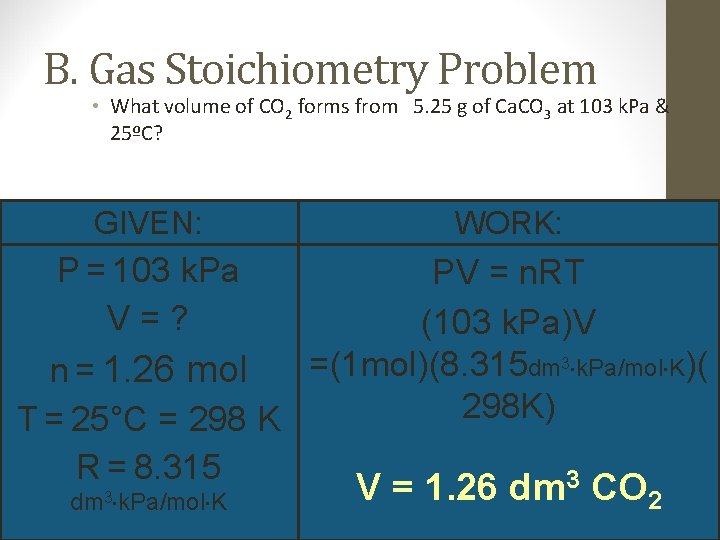

B. Gas Stoichiometry Problem • What volume of CO 2 forms from 5. 25 g of Ca. CO 3 at 103 k. Pa & 25ºC? Ca. CO 3 5. 25 g Ca. O + Looking for liters: Start with stoich and calculate moles of CO 2. 5. 25 g 1 mol Ca. CO 3 CO 2 100. 09 1 mol g Ca. C CO 2 ? L non. STP = 1. 26 mol Plug this into the 2 Ideal CO Gas Law to find liters.

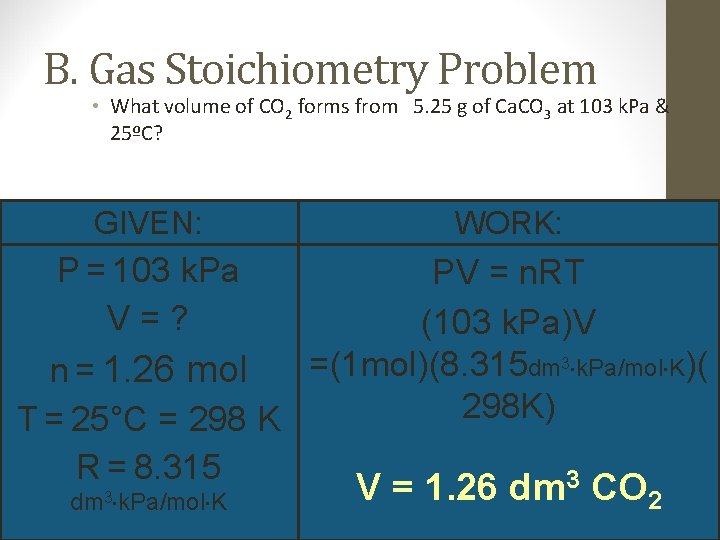

B. Gas Stoichiometry Problem • What volume of CO 2 forms from 5. 25 g of Ca. CO 3 at 103 k. Pa & 25ºC? GIVEN: WORK: P = 103 k. Pa PV = n. RT V=? (103 k. Pa)V =(1 mol)(8. 315 dm 3 k. Pa/mol K)( n = 1. 26 mol 298 K) T = 25°C = 298 K R = 8. 315 3 dm 3 k. Pa/mol K V = 1. 26 dm CO 2

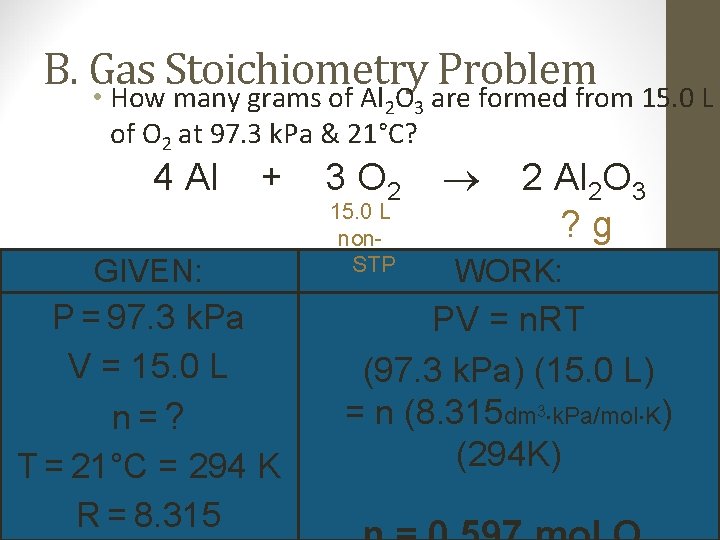

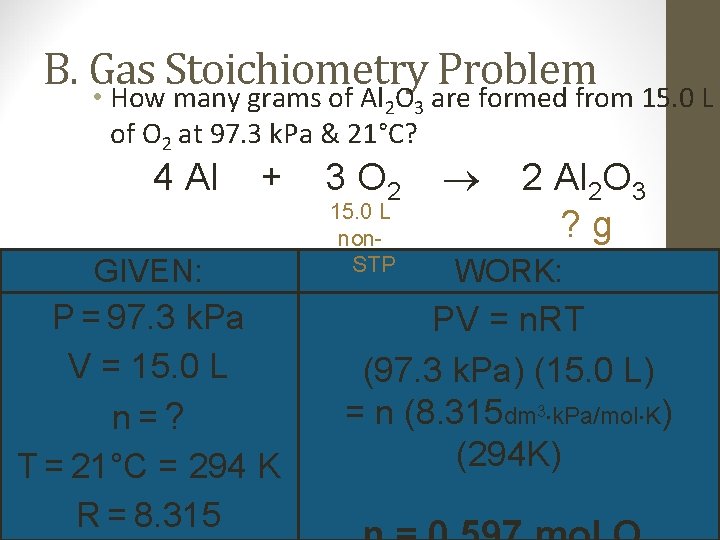

B. Gas Stoichiometry Problem • How many grams of Al O are formed from 15. 0 L 2 3 of O 2 at 97. 3 k. Pa & 21°C? 4 Al + GIVEN: P = 97. 3 k. Pa V = 15. 0 L n=? T = 21°C = 294 K R = 8. 315 3 O 2 15. 0 L non. STP 2 Al 2 O 3 ? g WORK: PV = n. RT (97. 3 k. Pa) (15. 0 L) = n (8. 315 dm 3 k. Pa/mol K) (294 K)

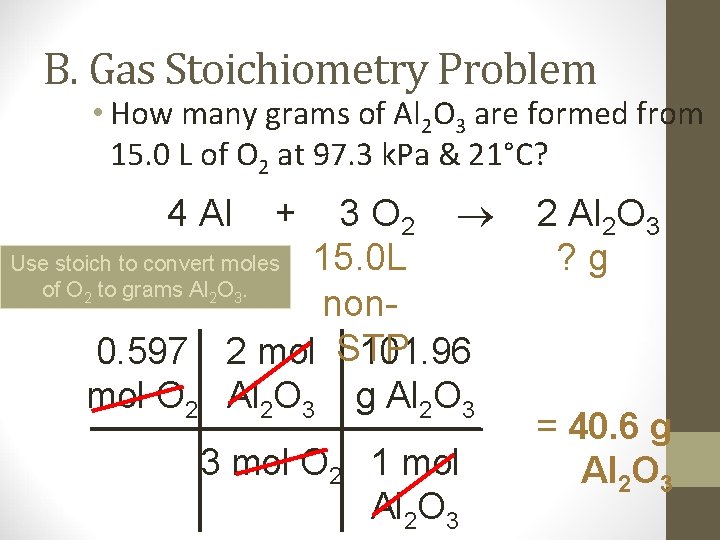

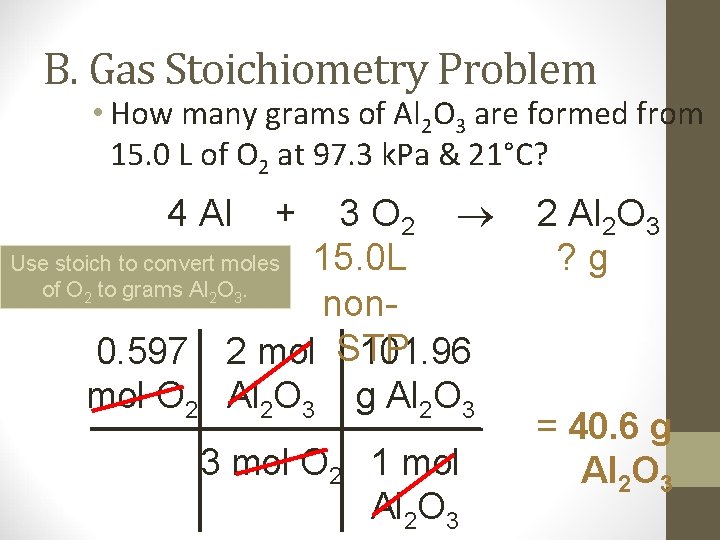

B. Gas Stoichiometry Problem • How many grams of Al 2 O 3 are formed from 15. 0 L of O 2 at 97. 3 k. Pa & 21°C? 3 O 2 Use stoich to convert moles 15. 0 L of O to grams Al O. non 0. 597 2 mol STP 101. 96 mol O 2 Al 2 O 3 g Al 2 O 3 4 Al 2 2 + 2 Al 2 O 3 ? g 3 3 mol O 2 1 mol Al 2 O 3 = 40. 6 g Al 2 O 3

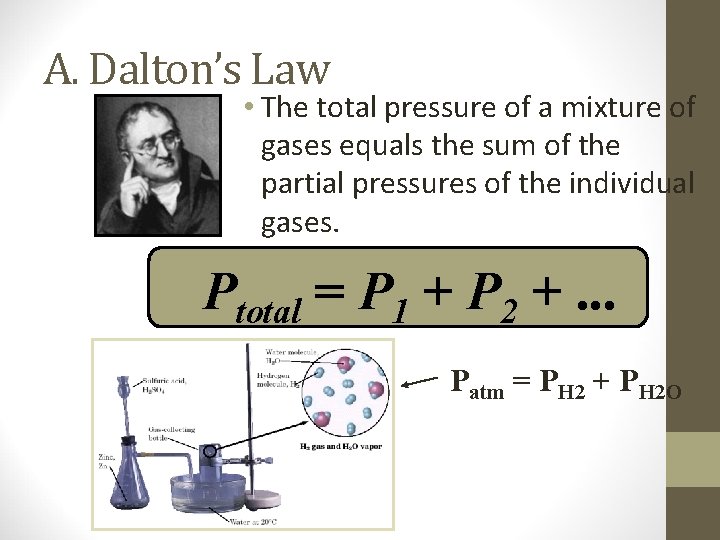

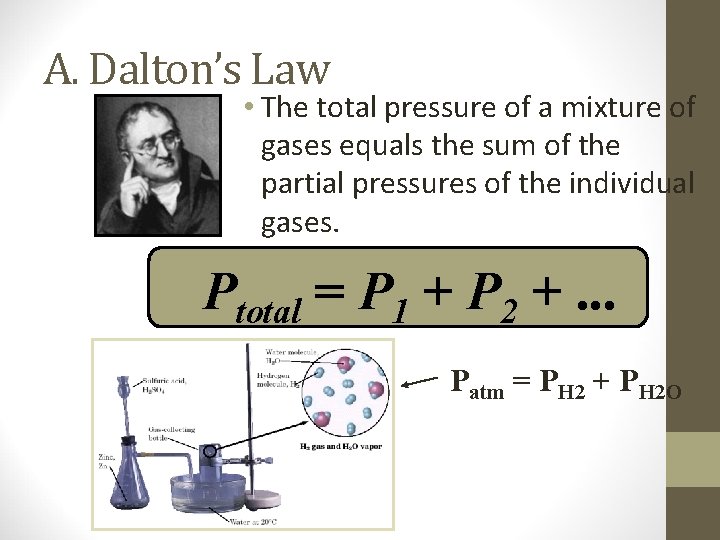

A. Dalton’s Law • The total pressure of a mixture of gases equals the sum of the partial pressures of the individual gases. Ptotal = P 1 + P 2 +. . . Patm = PH 2 + PH 2 O

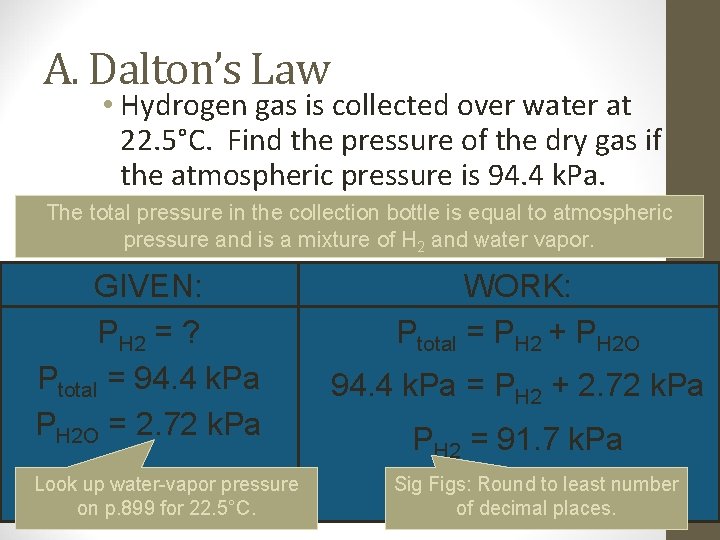

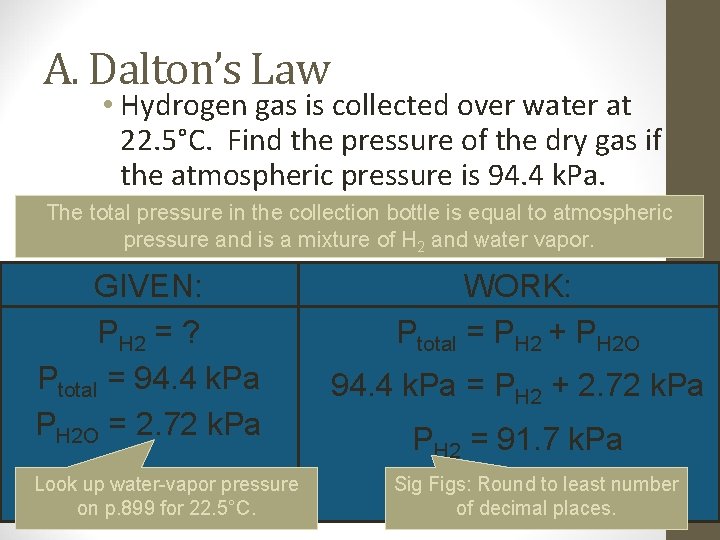

A. Dalton’s Law • Hydrogen gas is collected over water at 22. 5°C. Find the pressure of the dry gas if the atmospheric pressure is 94. 4 k. Pa. The total pressure in the collection bottle is equal to atmospheric pressure and is a mixture of H 2 and water vapor. GIVEN: PH 2 = ? Ptotal = 94. 4 k. Pa PH 2 O = 2. 72 k. Pa Look up water-vapor pressure on p. 899 for 22. 5°C. WORK: Ptotal = PH 2 + PH 2 O 94. 4 k. Pa = PH 2 + 2. 72 k. Pa PH 2 = 91. 7 k. Pa Sig Figs: Round to least number of decimal places.

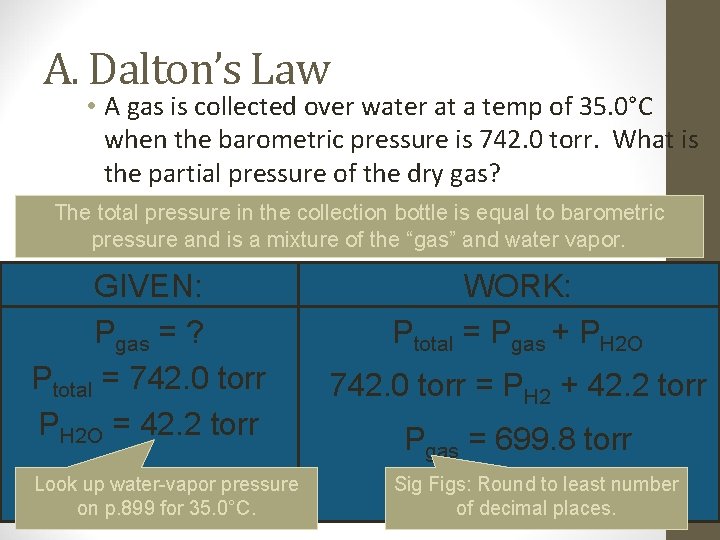

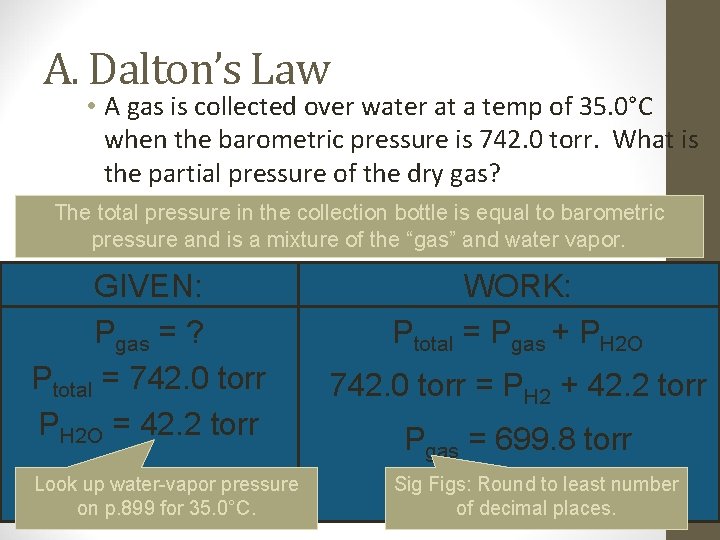

A. Dalton’s Law • A gas is collected over water at a temp of 35. 0°C when the barometric pressure is 742. 0 torr. What is the partial pressure of the dry gas? The total pressure in the collection bottle is equal to barometric pressure and is a mixture of the “gas” and water vapor. DALTON’S LAW GIVEN: Pgas = ? Ptotal = 742. 0 torr PH 2 O = 42. 2 torr Look up water-vapor pressure on p. 899 for 35. 0°C. WORK: Ptotal = Pgas + PH 2 O 742. 0 torr = PH 2 + 42. 2 torr Pgas = 699. 8 torr Sig Figs: Round to least number of decimal places.