Staphylococcus aureus literally Golden Cluster Seed and also

![Means of Transmission § The transmission of Y. pestis by fleas is well characterized[19]. Means of Transmission § The transmission of Y. pestis by fleas is well characterized[19].](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/75211ee00f4a1bf75bf32348769a927c/image-48.jpg)

- Slides: 56

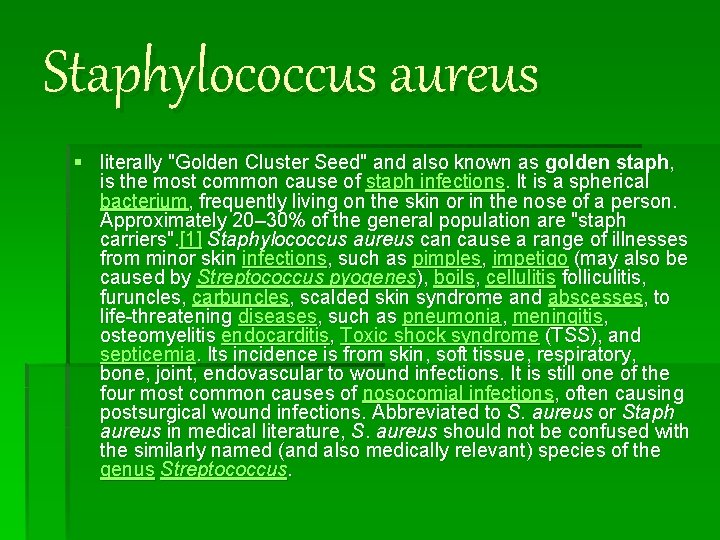

Staphylococcus aureus § literally "Golden Cluster Seed" and also known as golden staph, is the most common cause of staph infections. It is a spherical bacterium, frequently living on the skin or in the nose of a person. Approximately 20– 30% of the general population are "staph carriers". [1] Staphylococcus aureus can cause a range of illnesses from minor skin infections, such as pimples, impetigo (may also be caused by Streptococcus pyogenes), boils, cellulitis folliculitis, furuncles, carbuncles, scalded skin syndrome and abscesses, to life-threatening diseases, such as pneumonia, meningitis, osteomyelitis endocarditis, Toxic shock syndrome (TSS), and septicemia. Its incidence is from skin, soft tissue, respiratory, bone, joint, endovascular to wound infections. It is still one of the four most common causes of nosocomial infections, often causing postsurgical wound infections. Abbreviated to S. aureus or Staph aureus in medical literature, S. aureus should not be confused with the similarly named (and also medically relevant) species of the genus Streptococcus.

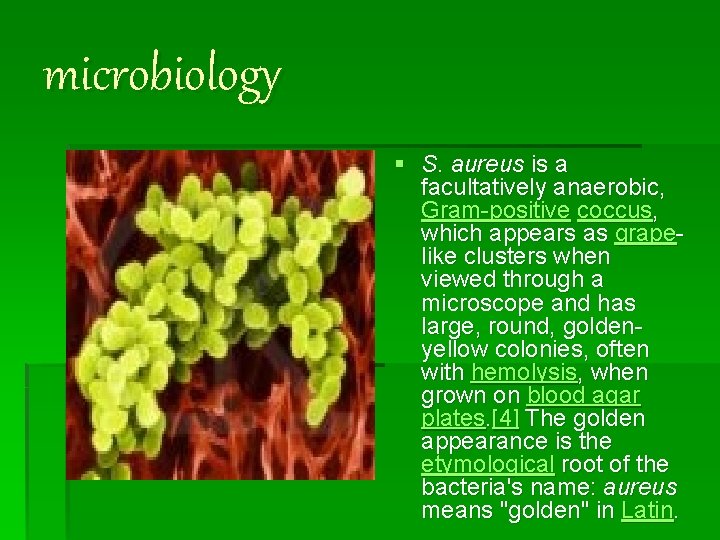

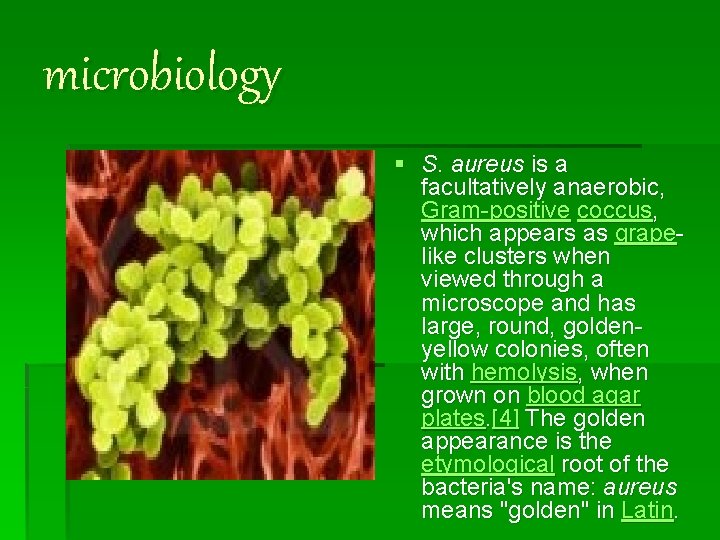

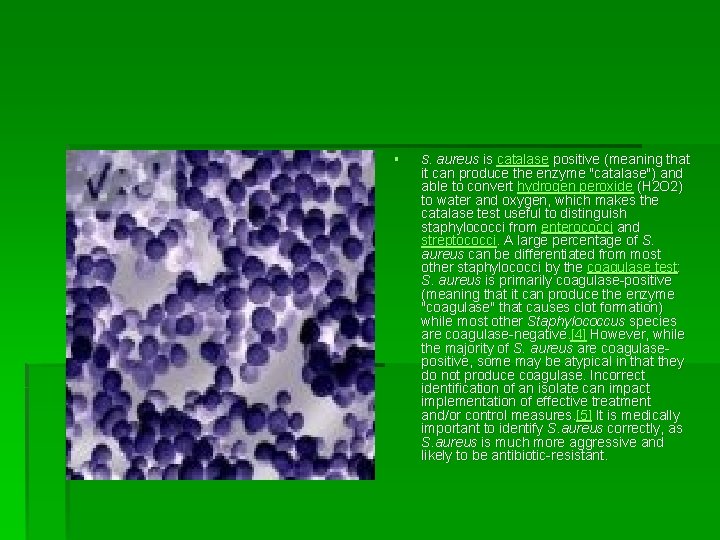

microbiology § S. aureus is a facultatively anaerobic, Gram-positive coccus, which appears as grapelike clusters when viewed through a microscope and has large, round, goldenyellow colonies, often with hemolysis, when grown on blood agar plates. [4] The golden appearance is the etymological root of the bacteria's name: aureus means "golden" in Latin.

§ S. aureus is catalase positive (meaning that it can produce the enzyme "catalase") and able to convert hydrogen peroxide (H 2 O 2) to water and oxygen, which makes the catalase test useful to distinguish staphylococci from enterococci and streptococci. A large percentage of S. aureus can be differentiated from most other staphylococci by the coagulase test: S. aureus is primarily coagulase-positive (meaning that it can produce the enzyme "coagulase" that causes clot formation) while most other Staphylococcus species are coagulase-negative. [4] However, while the majority of S. aureus are coagulasepositive, some may be atypical in that they do not produce coagulase. Incorrect identification of an isolate can impact implementation of effective treatment and/or control measures. [5] It is medically important to identify S. aureus correctly, as S. aureus is much more aggressive and likely to be antibiotic-resistant.

Role in disease § S. aureus may occur as a commensal on human skin; it also occurs in the nose frequently (in about a third of the population)[6] and throat less commonly. The occurrence of S. aureus under these circumstances does not always indicate infection and therefore does not always require treatment (indeed, treatment may be ineffective and re-colonisation may occur). It can survive on domesticated animals such as dogs, cats and horses, and can cause bumblefoot in chickens. It can survive for some hours on dry environmental surfaces, but the importance of the environment in spread of S. aureus is currently debated. It can host phages, such as the Panton-Valentine leukocidin, that increase its virulence.

§ S. aureus can infect other tissues when normal barriers have been breached (e. g. , skin or mucosal lining). This leads to furuncles (boils) and carbuncles (a collection of furuncles). In infants S. aureus infection cause a severe disease Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS). [7]

§ S. aureus infections can be spread through contact with pus from an infected wound, skin-to-skin contact with an infected person by producing hyaluronidase that destroy tissues, and contact with objects such as towels, sheets, clothing, or athletic equipment used by an infected person.

Rickettsia rickettsii

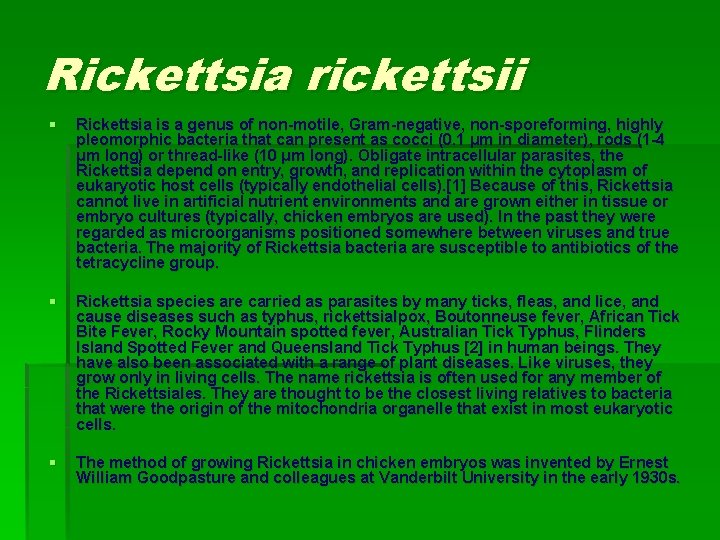

Rickettsia rickettsii § Rickettsia is a genus of non-motile, Gram-negative, non-sporeforming, highly pleomorphic bacteria that can present as cocci (0. 1 μm in diameter), rods (1 -4 μm long) or thread-like (10 μm long). Obligate intracellular parasites, the Rickettsia depend on entry, growth, and replication within the cytoplasm of eukaryotic host cells (typically endothelial cells). [1] Because of this, Rickettsia cannot live in artificial nutrient environments and are grown either in tissue or embryo cultures (typically, chicken embryos are used). In the past they were regarded as microorganisms positioned somewhere between viruses and true bacteria. The majority of Rickettsia bacteria are susceptible to antibiotics of the tetracycline group. § Rickettsia species are carried as parasites by many ticks, fleas, and lice, and cause diseases such as typhus, rickettsialpox, Boutonneuse fever, African Tick Bite Fever, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Australian Tick Typhus, Flinders Island Spotted Fever and Queensland Tick Typhus [2] in human beings. They have also been associated with a range of plant diseases. Like viruses, they grow only in living cells. The name rickettsia is often used for any member of the Rickettsiales. They are thought to be the closest living relatives to bacteria that were the origin of the mitochondria organelle that exist in most eukaryotic cells. § The method of growing Rickettsia in chicken embryos was invented by Ernest William Goodpasture and colleagues at Vanderbilt University in the early 1930 s.

Scientific classification Phylum: Proteobacteria Class: Alpha Proteobacteria Order: Rickettsiales Family: Rickettsiaceae Genus: Rickettsia

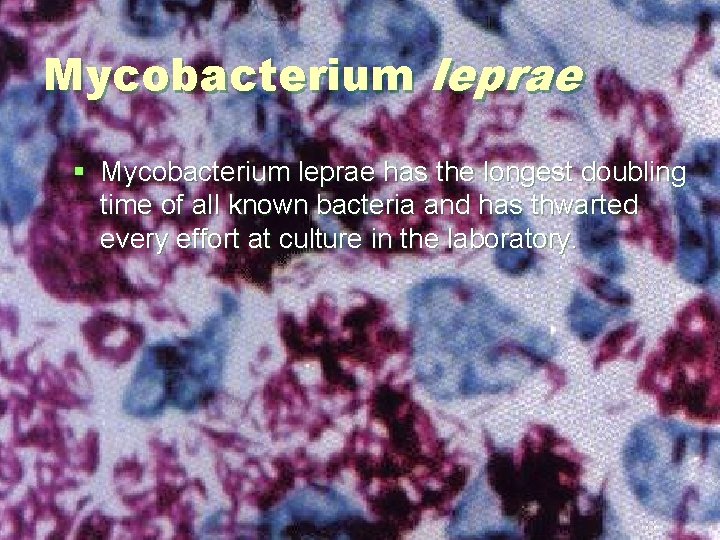

Mycobacterium leprae

Mycobacterium leprae § Also known as Hansen’s bacillus, mostly found in warm tropical countries, is the bacterium that causes leprosy. It is an intracellular, pleomorphic, acid fast bacterium. Mycobacterium leprae is a gram-positive, aerobic rod-shaped or bacillus surrounded by the characteristic waxy coating unique to mycobacteria. In size and shape, it closely resembles Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The culture takes several weeks to mature.

Mycobacterium leprae § The organism has never been successfully grown on a an artificial cell culture media. Instead it has been grown in mouse foot pads and more recently in ninebanded armadillos because they, like humans are susceptible to leprosy. The difficulty in culturing the organism appears to be because the organism is an obligate intracellular parasite that lacks many necessary genes for independent survival. The complex and unique cell wall that makes member of the Mycobacterium genus difficult to destroy is apparently also the reason for the extremely slow replication or doubling rate.

Mycobacterium leprae § Mycobacterium leprae has the longest doubling time of all known bacteria and has thwarted every effort at culture in the laboratory.

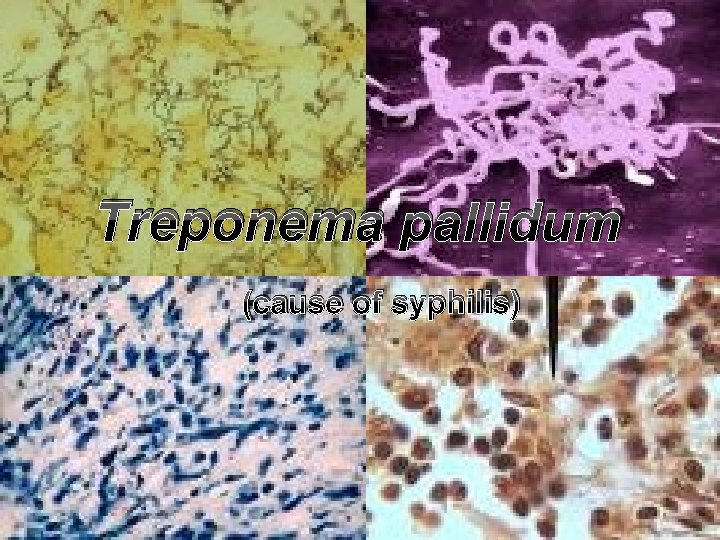

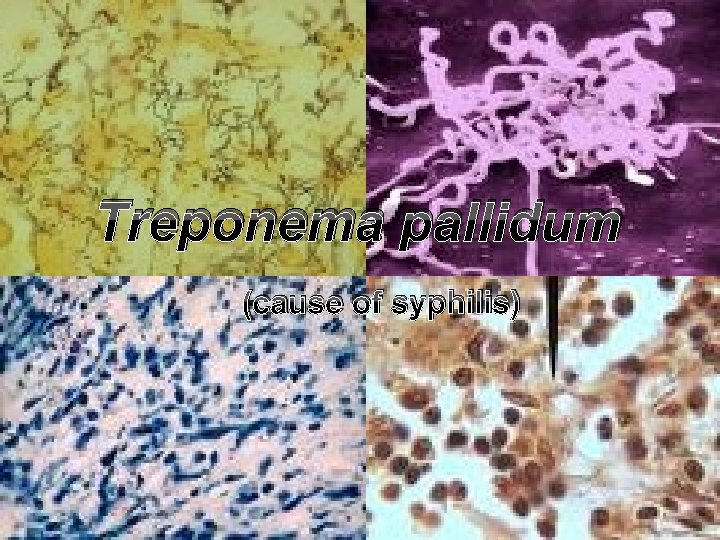

Treponema pallidum (cause of syphilis)

Treponema pallidum Background: v. Scientific classification: v. Kingdom: Eubacteria v. Phylum: Spirochaetes v. Class: Spirochaetes v. Order: Spirochaetales v. Family: Treponemataceae v. Genus: Treponema v. Species: T. pallidum v. Binomial name: Treponema pallidum

v. Treponema pallidum subsp pallidum is a fastidious organism that exhibits narrow optimal ranges of p. H (7. 2 to 7. 4), Eh (230 to 240 m. V), and temperature (30 to 37°C). v. It is rapidly inactivated by mild heat, cold, desiccation, and most disinfectants.

v Traditionally this organism has been considered a strict anaerobe, but it is now known to be microaerophilic. v Viable organisms can be maintained for 18 to 21 days in complex media, while limited replication has been obtained by cocultivation with tissue culture cells. The other three pathogenic treponemes also have not been successfully grown in vitro.

v. The cytoplasmic membrane covers the protoplasmic cylinder; this membrane contains the majority of the bacterium's integral membrane proteins and is particularly abundant in lipid-modified polypeptides (lipoproteins). v. The presence of peptidoglycan in the cell wall, originally surmised on the basis of the bacterium's exquisite sensitivity to penicillin, has been confirmed by biochemical analysis.

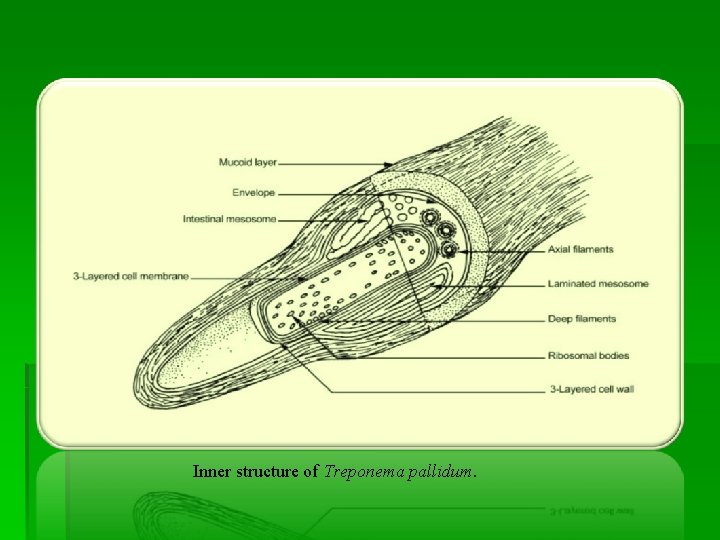

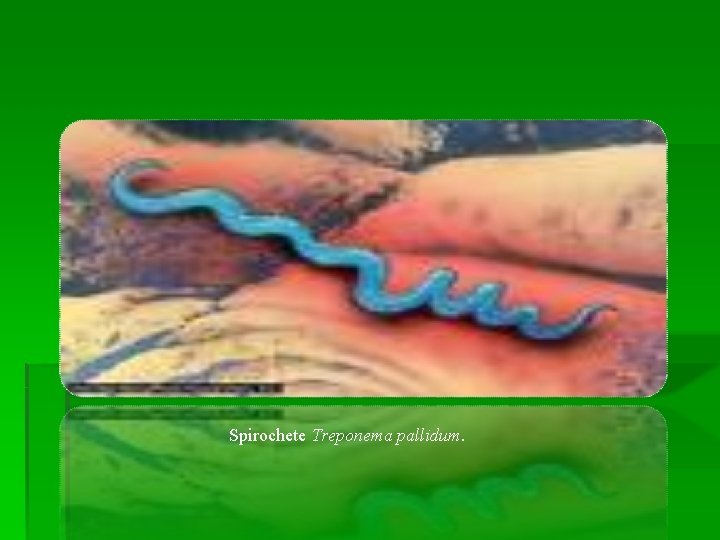

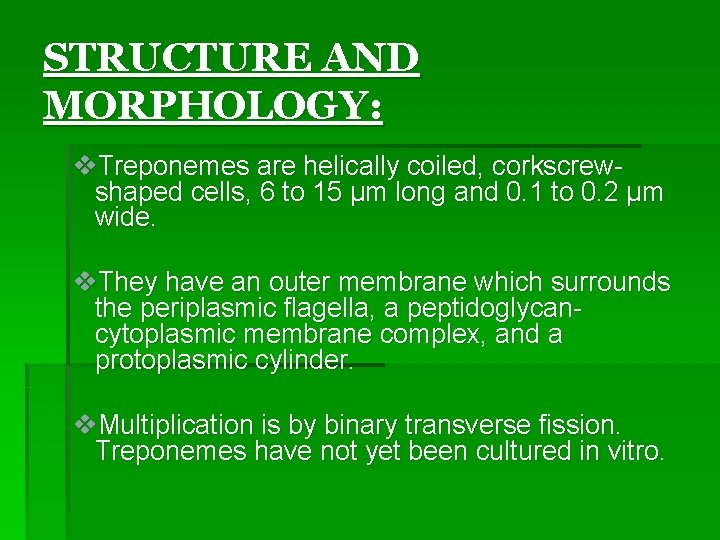

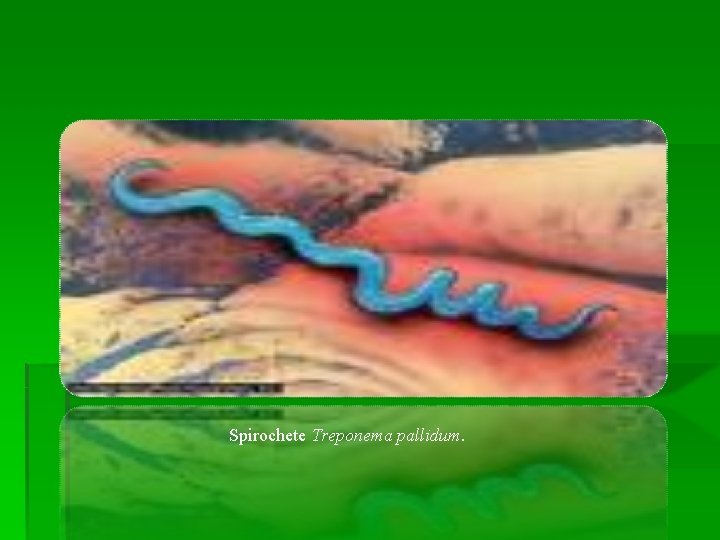

STRUCTURE AND MORPHOLOGY: v. Treponemes are helically coiled, corkscrewshaped cells, 6 to 15 µm long and 0. 1 to 0. 2 µm wide. v. They have an outer membrane which surrounds the periplasmic flagella, a peptidoglycancytoplasmic membrane complex, and a protoplasmic cylinder. v. Multiplication is by binary transverse fission. Treponemes have not yet been cultured in vitro.

Inner structure of Treponema pallidum.

Spirochete Treponema pallidum.

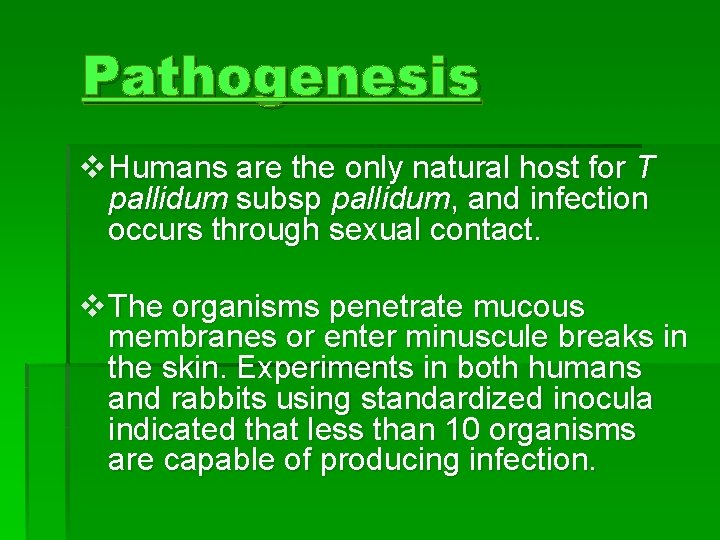

Pathogenesis v Humans are the only natural host for T pallidum subsp pallidum, and infection occurs through sexual contact. v The organisms penetrate mucous membranes or enter minuscule breaks in the skin. Experiments in both humans and rabbits using standardized inocula indicated that less than 10 organisms are capable of producing infection.

EPIDEMIOLOGY: v. Humans are the only source of treponemal infection; there are no known nonhuman reservoirs. v Infectivity rates correspond to the most sexually active age groups, being highest in the 20 -to 24 -year age group, slightly lower in the 15 - to 19 - year age group, and lower still in the 25 - to 29 year age group.

Leptospira

§ Leptospira (from the Greek leptos, meaning fine or thin, and the Latin spira, meaning coil)[1] is a genus of spirochaete bacteria, including a small number of pathogenic and saprophytic species. [2] Leptospira was first observed in 1907 in kidney tissue slices of a leptospirosis victim who was described as having died of "yellow fever. "[3]

Pathogenesis of leptospira § Leptospira enters the host through mucosa and broken skin, resulting in bacteremia. The spirochetes multiply in organs, most commonly the central nervous system, kidneys, and liver. They are cleared by the immune response from the blood and most tissues but persist and multiply for some time in the kidney tubules. Infective bacteria are shed in the urine. The mechanism of tissue damage is not known.

§ Epidemiology § Leptospirosis is a worldwide zoonosis affecting many wild and domestic animals. Humans acquire the infection by contact with the urine of infected animals. Human-to-human transmission is extremely rare.

§ Leptospirosis (also known as Weil's disease, canicola fever, canefield fever, nanukayami fever, 7 -day fever and many more[1]) is a bacterial zoonotic disease caused by spirochaetes of the genus Leptospira that affects humans and a wide range of animals, including mammals, birds, amphibians, and reptiles. It was first described by Adolf Weil in 1886 when he reported an "acute infectious disease with enlargement of spleen, jaundice and nephritis". Leptospira was first observed in 1907 from a post mortem renal tissue slice. [2] § Though being recognised among the world's most common zoonoses, leptospirosis is a relatively rare bacterial infection in humans. The infection is commonly transmitted to humans by allowing fresh water that has been contaminated by animal urine to come in contact with unhealed breaks in the skin, eyes or with the mucous membranes. Outside of tropical areas, leptospirosis cases have a relatively distinct seasonality with most of them occurring August-September/February-March.

§ Treatment § Leptospirosis treatment is a relatively complicated process comprising two main components suppressing the causative agent and fighting possible complications. Aetiotropic drugs are antibiotics, such as doxycycline, penicillin, ampicillin, and amoxicillin (doxycycline can also be used as a prophylaxis). There are no human vaccines; animal vaccines are only for a few strains, and are only effective for a few months. Human therapeutic dosage of drugs is as follows: doxycycline 100 mg orally every 12 hours for 1 week or penicillin 1 -1. 5 MU every 4 hours for 1 week. Doxycycline 200 -250 mg once a week is administered as a prophylaxis. In dogs, penicillin is most commonly used to end the leptospiremic phase (infection of the blood), and doxycycline is used to eliminate the carrier state.

§ Supportive therapy measures (esp. in severe cases) include detoxication and normalization of the hydroelectrolytic balance. Glucose and salt solution infusions may be administered; dialysis is used in serious cases. Elevations of serum potassium are common and if the potassium level gets too high special measures must be taken. Serum phosphorus levels may likewise increase to unacceptable levels due to renal failure. Treatment for hyperphosphatemia consists of treating the underlying disease, dialysis where appropriate, or oral administration of calcium carbonate, but not without first checking the serum calcium levels (these two levels are related). Corticosteroids administration in gradually reduced doses (e. g. , prednisolone starting from 30 -60 mg) during 7 -10 days is recommended by some specialists in cases of severe haemorrhagic effects.

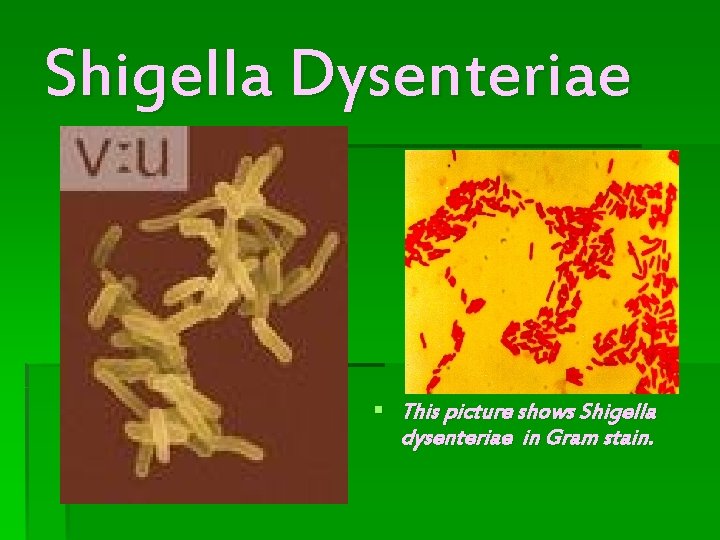

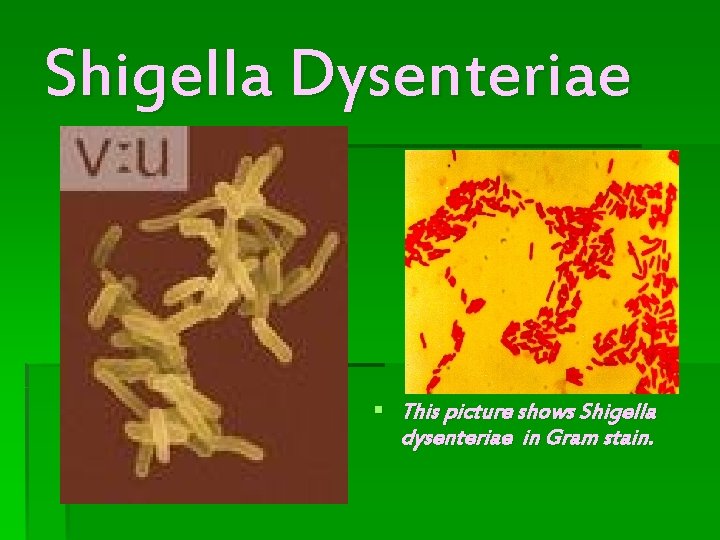

Shigella Dysenteriae § This picture shows Shigella dysenteriae in Gram stain.

Shigella Dysenteriae § Scientific classification Kingdom: Bacteria Phylum: Proteobacteria Class: Gamma Proteobacteria Order: Enterobacteriales Family: Enterobacteriaceae Genus: Shigella Species: S. dysenteriae § Binomial name Shigella dysenteriae (Shiga 1897) § Definition : Shigellosis is an infection with shigella (a rod-shaped bacteria) that normally occurs in the digestive tract.

Description of Shigella : § Shigella dysentery is a common disease, often self-limited and mild but occasionally serious, particularly in the first 3 years of life. Poor sanitary conditions promote the spread of shigella. § Shigella sonnei is the leading cause of this illness in the U. S. , followed by shigella flexneri. Shigella dysenteriae causes the most serious form of this illness. Recently, there has been a rise in strains resistant to multiple antibiotics.

PATHOGENESIS: § Shigella differs from other members of the family of Enterobacteriaceae in that it has genes that code for epithelial cell invasion and for the production of a potent shiga toxin. The disease is highly communicable. According to some estimates, as few as 10 cells can cause an infection, whereas it can take tens of millions of cholera vibrios to induce disease. § The bacterium is spread by fecal-contaminated food or water. Once ingested, the organisms colonize the intestines, then invade the colonic epithelial cells, causing disease. Cell death, tissue destruction, acute inflammation, and ulceration of the mucosa ensues. § The Shiga toxin is a potent A-B type toxin with 1 -A and 5 -B subunits bind to the cell and inject the A-subunit. By cleaving a specific adenine residue from the 28 S ribosomal RNA in the 60 S ribosome, the toxin inhibits protein synthesis, causing cell death.

Symptoms § The usual symptoms are diarrhea associated with cramping, abdominal pain, chills, and malaise, headache, and fever. The diarrhea often contains blood and mucus. The patient may become progressively weaker and more dehydrated.

Causes and Risk Factors § Shigella is transmitted primarily from person-to-person by the fecal-oral route. Outbreaks can occur in day-care centers. Occasionally, outbreaks can be caused by contamination of food by infected food handlers.

Diagnosis § A stool sample will be analyzed for blood and white blood cells (mucus), and a culture may be done. Examination by sigmoidoscope (a tube inserted into the rectum to visualize the surface) reveals an inflamed, engorged mucosa (lining) with areas of ulceration.

Treatment § Antimicrobial treatment may include Bactrim (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) or Cipro (ciprofloxacin), usually for 7 to 10 days. Treatment of dehydration and hypotension (low blood pressure) is lifesaving in severe cases. Antispasmodics are helpful when cramps are severe. § Appropriate precautions should be taken both in the hospital and in the home to limit the spread of infection.

Prevention § Shigella infection can be prevented by assuring that adequate hand washing technique is used by all involved in the preparation of food. If in doubt about the quality of food purchased in restaurants, delis or while traveling, stick to processed foods and bottled drinks.

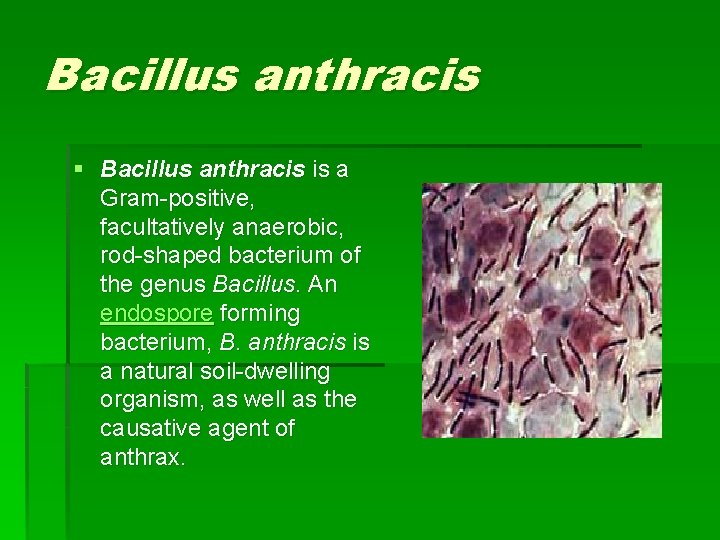

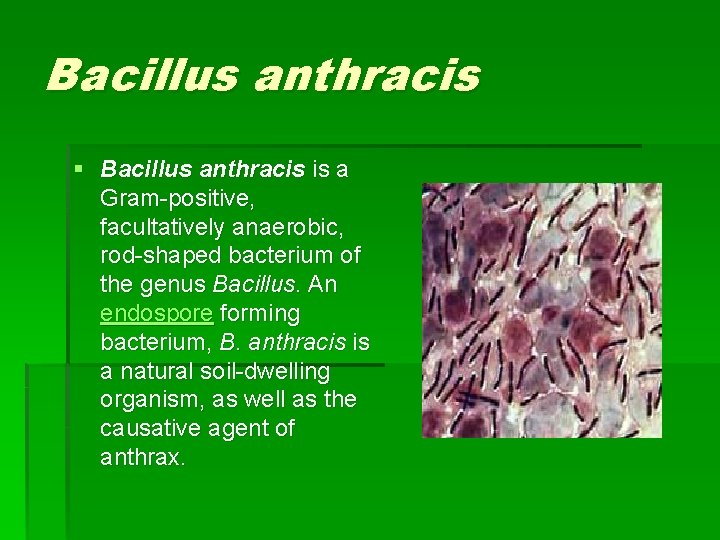

Bacillus anthracis § Bacillus anthracis is a Gram-positive, facultatively anaerobic, rod-shaped bacterium of the genus Bacillus. An endospore forming bacterium, B. anthracis is a natural soil-dwelling organism, as well as the causative agent of anthrax.

Scientific Classification § Kingdom: Bacteria Phylum: Firmicutes Class: Bacilli Order: Bacillales Family: Bacillaceae Genus: Bacillus Species: B. anthracis

§ When cutaneous anthrax affects a patient a painless, raised nodule forms at the site. As the B. anthracis continues to grow, the cells surrounding the nodule die and the nodule spreads. Eschar, the name given to the enlarged blackened (from the dead cells) lesion comes from a Greek word meaning "charcoal. "

Treatment § Infections with B. anthracis can be treated with β-lactam antibiotics such as penicillin, and others which are active against Gram-positive bacteria.

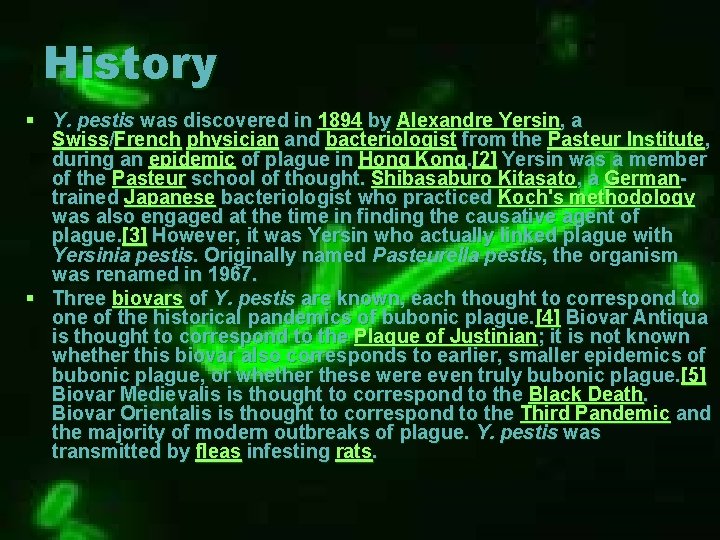

History § Y. pestis was discovered in 1894 by Alexandre Yersin, a Swiss/French physician and bacteriologist from the Pasteur Institute, during an epidemic of plague in Hong Kong. [2] Yersin was a member of the Pasteur school of thought. Shibasaburo Kitasato, a Germantrained Japanese bacteriologist who practiced Koch's methodology was also engaged at the time in finding the causative agent of plague. [3] However, it was Yersin who actually linked plague with Yersinia pestis. Originally named Pasteurella pestis, the organism was renamed in 1967. § Three biovars of Y. pestis are known, each thought to correspond to one of the historical pandemics of bubonic plague. [4] Biovar Antiqua is thought to correspond to the Plague of Justinian; it is not known whether this biovar also corresponds to earlier, smaller epidemics of bubonic plague, or whether these were even truly bubonic plague. [5] Biovar Medievalis is thought to correspond to the Black Death. Biovar Orientalis is thought to correspond to the Third Pandemic and the majority of modern outbreaks of plague. Y. pestis was transmitted by fleas infesting rats.

Morphology § Y. pestis is a rod-shaped facultative anaerobe with bipolar staining (giving it a safety pin appearance). [8] Similar to other Yersinia members, it tests negative for urease, lactose fermentation, and indole. [9] The closest relative is the gastrointestinal pathogen Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, and more distantly Yersinia enterocolitica.

Pathogenics and Immunity § The reservoir commonly associated with Y. pestis are several species of rodents. In the steppes, the reservoir species is principally believed to be the marmot. In the United States, several species of rodents are thought maintain Y. pestis. However, the case is not very clear because the expected disease dynamics have not been found in any rodent species. It is known that some individuals in a rodent population will have a different resistance, which could lead to a carrier status. There is some evidence that fleas from other mammals have a role in human plague outbreaks. This lack of knowledge of the dynamics of plague in mammal species is also true among susceptible rodents such as the black-tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus), in which plague can cause colony collapse resulting in a massive effect on prairie food webs. However, the transmission dynamics within prairie dogs does not follow the dynamics of blocked fleas; carcasses, unblocked fleas, or another vector could possibly be important instead. [In other regions of the world the reservoir of the infection is not clearly identified, which complicates prevention and early warning programs. One

![Means of Transmission The transmission of Y pestis by fleas is well characterized19 Means of Transmission § The transmission of Y. pestis by fleas is well characterized[19].](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/75211ee00f4a1bf75bf32348769a927c/image-48.jpg)

Means of Transmission § The transmission of Y. pestis by fleas is well characterized[19]. Initial acquisition of Y. pestis by the vector occurs during feeding on an infected animal. Several proteins then contribute to the maintenance of the bacteria in the flea digestive tract, among them the hemin storage (Hms) system and Yersinia murine toxin (Ymt). § Although Ymt is highly toxic to rodents and was once thought to be produced to insure reinfection of new hosts, it has been demonstrated that murine toxin is important for the survival of Y. pestis in fleas. [20] § The Hms system plays an important role in the transmission of Y. pestis back to a mammalian host[21]. The proteins encoded by Hms genetic loci aggregate in the esophagus and proventriculus of the flea, which is a structure that ruptures blood cells. Aggregation of Hms proteins inhibits feeding and causes the flea to feel hungry. Transmission of Y. pestis occurs during the futile attempts of the flea to feed. Ingested blood is pumped into the esophagus, where it dislodges bacteria growing there and is regurgitated back into the host circulatory system.

Symptoms § Bubonic plague § Incubation period of 2 -6 days, when the bacteria is actively replicating in lymph nodes § Universally a general lack of energy § Fever § Headache and chills occur suddenly at the end of the incubation period. From this point the infection is resolved or lethal. § Swelling of lymph nodes resulting of buboes, this is the classic sign of bubonic plague

Symptoms § Septicemic plague § § § § Hypotension Hepatosplenomegaly Delirium Seizures in children Shock Universally a general lack of energy Fever Symptoms of Bubonic or Pneumonic Plague, not always present

Symptoms § Pneumonic plague § § § § § Fever Chills Cough Chest pain Dyspnea Hemoptysis Lethargy Hypotension Shock Symptoms of bubonic or septicemic plague, not always present [27]

Streptococcus mutans

Streptococcus mutans § is a Gram-positive, facultative anaerobic bacteria commonly found in the human oral cavity and is a significant contributor to tooth decay. The microbe was first described by Clarke in 1924.

Role in tooth decay § § Along with S. sobrinus, S. mutans plays a major role in tooth decay, metabolizing sucrose to lactic acid. The acidic environment created in the mouth by this process is what causes the highly mineralized tooth enamel to be vulnerable to decay. S. mutans is one of a few specialized organisms equipped with receptors that help for better adhesion to the surface of teeth. Sucrose is utilized by S. mutans to produce a sticky, extracellular, dextran-based polysaccharide that allows them to cohere to each other forming plaque. S. mutans produces dextran via the enzyme dextransucrase (a hexosyltransferase) using sucrose as a substrate in the following reaction: n sucrose → (glucose)n + n fructose Sucrose is the only sugar that S. mutans can use to form this sticky polysaccharide. [1] Conversely, many other sugars—glucose, fructose, lactose—can be digested by S. mutans, but they produce lactic acid as an end product. It is the combination of plaque and acid that leads to dental decay. Due to the role the S. mutans plays in tooth decay, there have been many attempts to make a vaccine for the organism. So far, such vaccines have not been successful in humans. Recently, proteins involved in the colonization of teeth by S. mutans have been shown to produce antibodies that inhibit the cariogenic process.

Cell Division and Cell Wall Synthesis § Several clusters of genes involved in cell division were found in the UA 159 genome, including those conserved in most bacteria. Additionally, there are more than 60 proteins responsible for cell envelope biogenesis, including 5 penicillin-binding proteins, 3 ABC transporters, 10 glycosyltransferases, and 6 autolysins. Autolysins are responsible for the selective removal of cell wall peptidoglycan and can be classified in different groups according to the type of peptidoglycan bond they hydrolyze. S. mutans shows enormous variability in chain length, which suggests that it has autolysins and that they are regulated. In fact, Clark named this organism ‘‘mutans’’ because of the observed changes in cell shape (probably due to wall remodeling) depending on growth conditions. . Four types of predicted autolysins were found in UA 159 including muramidase (amidase 4; SMU. 76), amidase 2 (SMU. 704) that is similar to the autolysins from Listeria monocytogenes, Listeria innocua, and Staphylococcus caprae, an endolysin (SMU. 707) homologous to one associated with a bacteriophage from S. pyogenes, and the Lrg. B family protein (SMU. 574) similar to the putative autolysin of S. aureus. Two more ORFs that encode a potential lytic transglycosylase (SMU. 2147) and an additional Lrg. B family protein (SMU. 1700) were also identified. However, autolysins that belong to the Lyt. C, Lyt. D, endopeptidase II, and lysostaphin families characteristic of bacillus and staphylococcus species were not present in UA 159

Virulence Factors § Virulence factors in S. mutans help protect the bacterium against possible host defenses and maintain its ecological niche in the oral cavity, while contributing to its ability to cause host damage. Probable virulence factors include adhesins, glucan-producing and binding exoenzymes, proteases and cytokinestimulating molecules. In addition to the factors described below, several other gene products were found in UA 159 that may also contribute to the virulence of S. mutans, such are hemolysins, the myosin cross-reactive streptococcal antigen and its paralog, a coiled-coil myosin-like protein, and the genes for transport and assimilation of iron and phosphate.