Stable Isotope Geochemistry III Lecture 34 Quaternary Ureys

Stable Isotope Geochemistry III Lecture 34

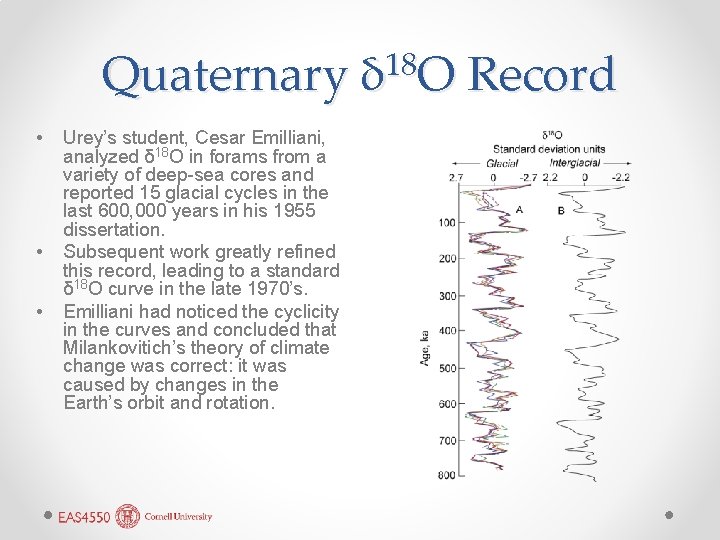

Quaternary • • • Urey’s student, Cesar Emilliani, analyzed δ 18 O in forams from a variety of deep-sea cores and reported 15 glacial cycles in the last 600, 000 years in his 1955 dissertation. Subsequent work greatly refined this record, leading to a standard δ 18 O curve in the late 1970’s. Emilliani had noticed the cyclicity in the curves and concluded that Milankovitich’s theory of climate change was correct: it was caused by changes in the Earth’s orbit and rotation. 18 δ O Record

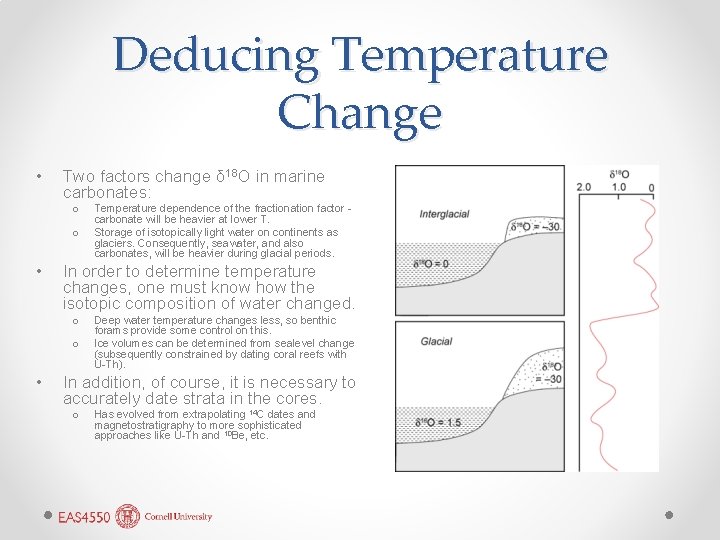

Deducing Temperature Change • Two factors change δ 18 O in marine carbonates: o o • In order to determine temperature changes, one must know how the isotopic composition of water changed. o o • Temperature dependence of the fractionation factor carbonate will be heavier at lower T. Storage of isotopically light water on continents as glaciers. Consequently, seawater, and also carbonates, will be heavier during glacial periods. Deep water temperature changes less, so benthic forams provide some control on this. Ice volumes can be determined from sealevel change (subsequently constrained by dating coral reefs with U-Th). In addition, of course, it is necessary to accurately date strata in the cores. o Has evolved from extrapolating 14 C dates and magnetostratigraphy to more sophisticated approaches like U-Th and 10 Be, etc.

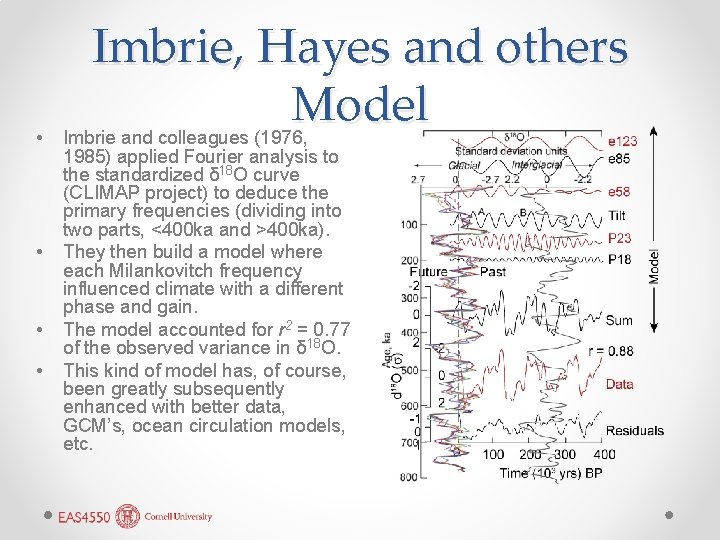

• • Imbrie, Hayes and others Model Imbrie and colleagues (1976, 1985) applied Fourier analysis to the standardized δ 18 O curve (CLIMAP project) to deduce the primary frequencies (dividing into two parts, <400 ka and >400 ka). They then build a model where each Milankovitch frequency influenced climate with a different phase and gain. The model accounted for r 2 = 0. 77 of the observed variance in δ 18 O. This kind of model has, of course, been greatly subsequently enhanced with better data, GCM’s, ocean circulation models, etc.

Milankovitch Variations • There are regular small variations in the Earth’s orbit and rotation known as Milankovitch Variations, or Milankovitch parameters. • They affect climate in each hemisphere, and the severity of seasonal variations. • They do not change the total annual solar radiation energy (insolation) that the Earth receives, only its distribution in space and time.

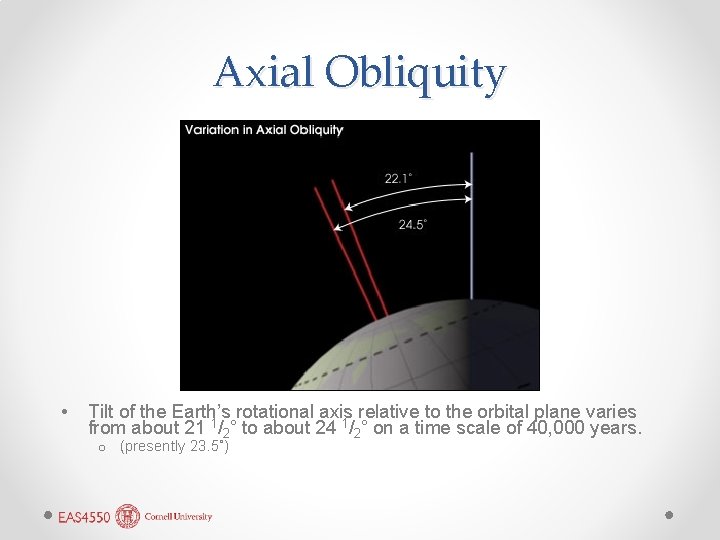

Axial Obliquity • Tilt of the Earth’s rotational axis relative to the orbital plane varies from about 21 1/2˚ to about 24 1/2˚ on a time scale of 40, 000 years. o (presently 23. 5˚)

Orbital Eccentricity • Earth’s orbit varies from more circular to less circular on a time scale of about 100, 000 years.

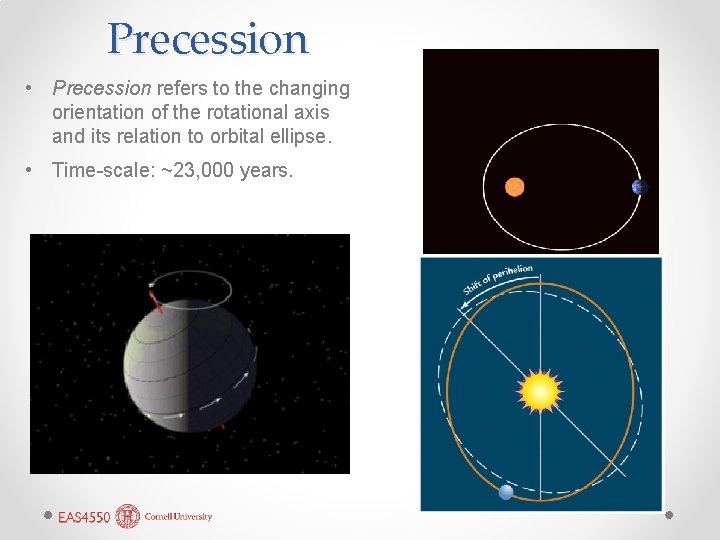

Precession • Precession refers to the changing orientation of the rotational axis and its relation to orbital ellipse. • Time-scale: ~23, 000 years.

Milankovitch Cycles • The timing of the warm and cold cycles determined with isotopes matched variations in the Earth’s orbit and rotation that change the distribution of solar energy on the Earth. • This confirmed a prediction by Serbian astronomy Milutin Milankovitch in 1915.

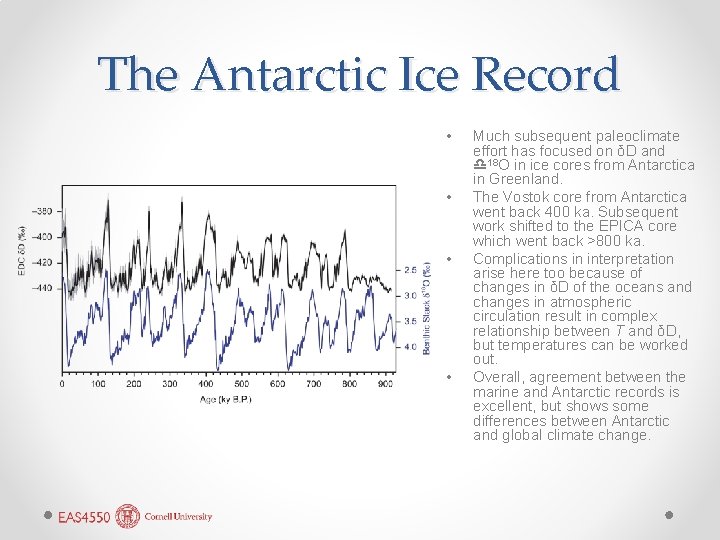

The Antarctic Ice Record • • Much subsequent paleoclimate effort has focused on δD and d 18 O in ice cores from Antarctica in Greenland. The Vostok core from Antarctica went back 400 ka. Subsequent work shifted to the EPICA core which went back >800 ka. Complications in interpretation arise here too because of changes in δD of the oceans and changes in atmospheric circulation result in complex relationship between T and δD, but temperatures can be worked out. Overall, agreement between the marine and Antarctic records is excellent, but shows some differences between Antarctic and global climate change.

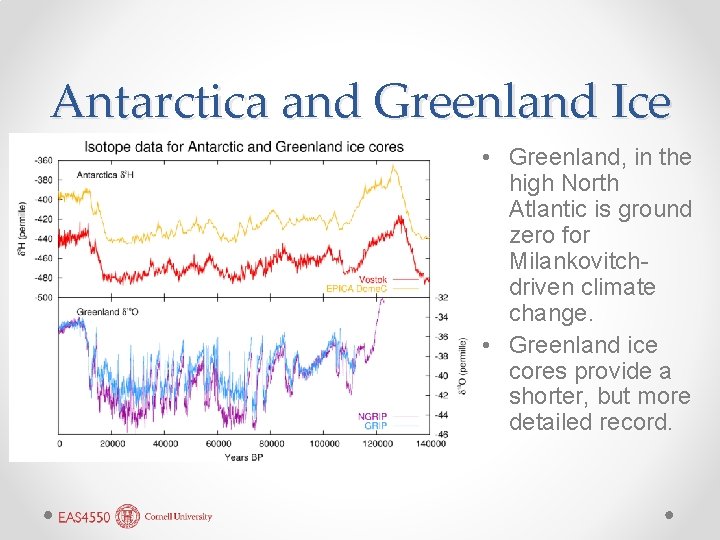

Antarctica and Greenland Ice • Greenland, in the high North Atlantic is ground zero for Milankovitchdriven climate change. • Greenland ice cores provide a shorter, but more detailed record.

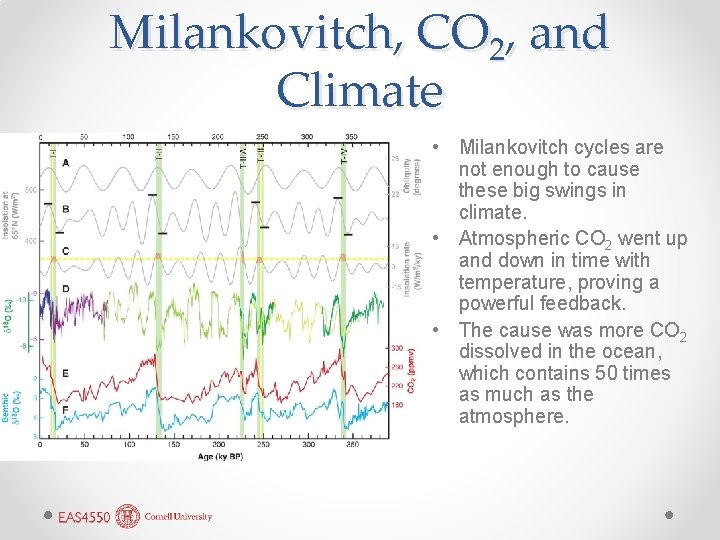

Milankovitch, CO 2, and Climate • Milankovitch cycles are not enough to cause these big swings in climate. • Atmospheric CO 2 went up and down in time with temperature, proving a powerful feedback. • The cause was more CO 2 dissolved in the ocean, which contains 50 times as much as the atmosphere.

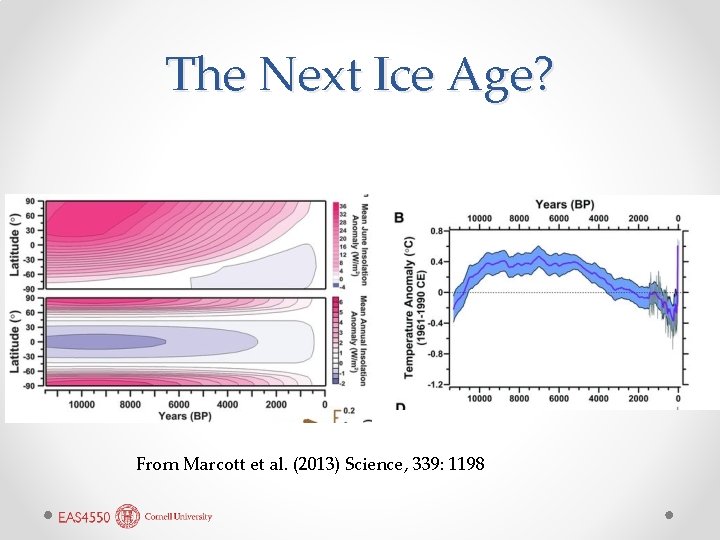

The Next Ice Age? From Marcott et al. (2013) Science, 339: 1198

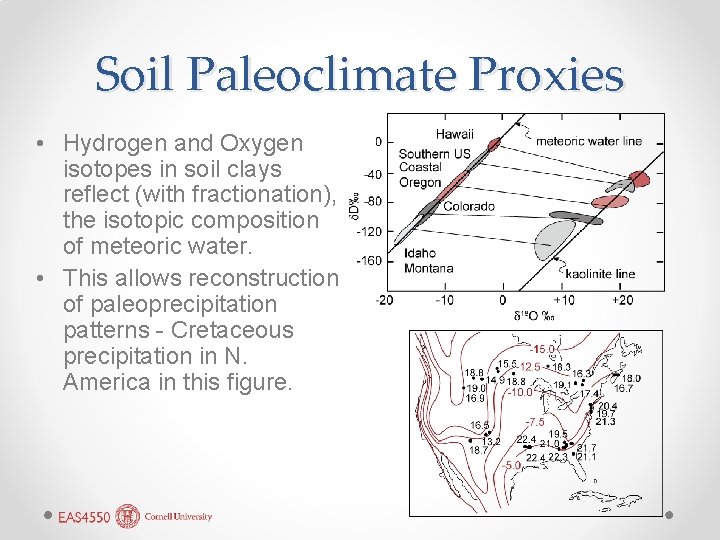

Soil Paleoclimate Proxies • Hydrogen and Oxygen isotopes in soil clays reflect (with fractionation), the isotopic composition of meteoric water. • This allows reconstruction of paleoprecipitation patterns - Cretaceous precipitation in N. America in this figure.

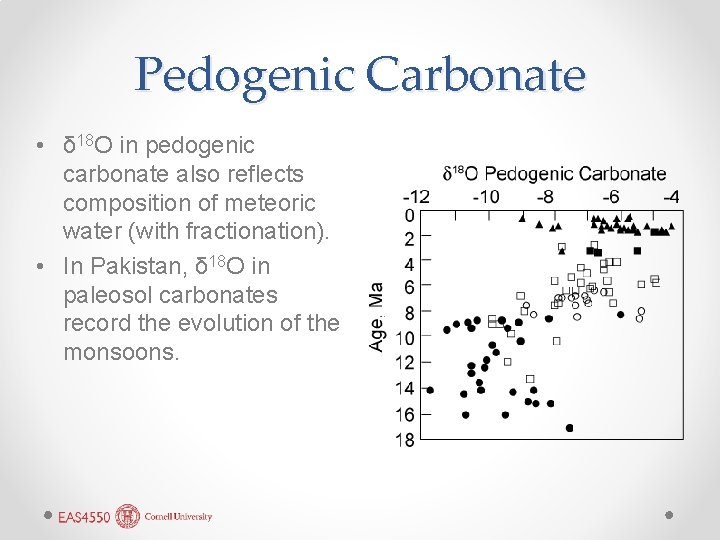

Pedogenic Carbonate • δ 18 O in pedogenic carbonate also reflects composition of meteoric water (with fractionation). • In Pakistan, δ 18 O in paleosol carbonates record the evolution of the monsoons.

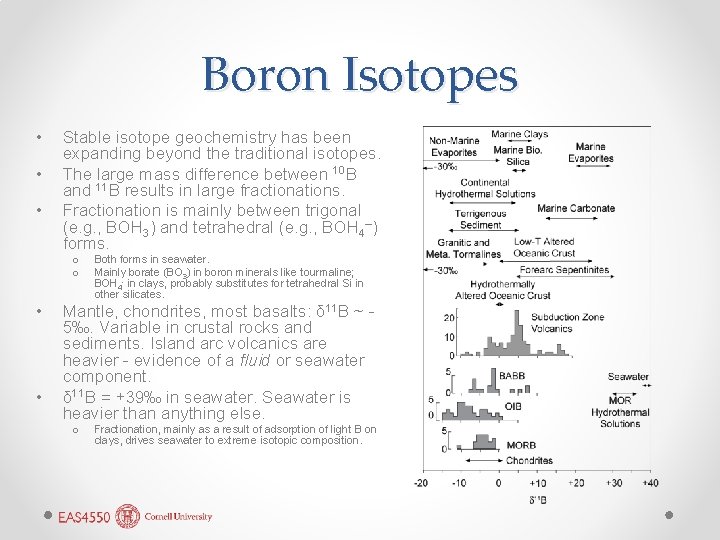

Boron Isotopes • • • Stable isotope geochemistry has been expanding beyond the traditional isotopes. The large mass difference between 10 B and 11 B results in large fractionations. Fractionation is mainly between trigonal (e. g. , BOH 3) and tetrahedral (e. g. , BOH 4–) forms. Both forms in seawater. Mainly borate (BO 3) in boron minerals like tourmaline; BOH 4 - in clays, probably substitutes for tetrahedral Si in other silicates. Mantle, chondrites, most basalts: δ 11 B ~ o o • • 5‰. Variable in crustal rocks and sediments. Island arc volcanics are heavier - evidence of a fluid or seawater component. δ 11 B = +39‰ in seawater. Seawater is heavier than anything else. o - Fractionation, mainly as a result of adsorption of light B on clays, drives seawater to extreme isotopic composition.

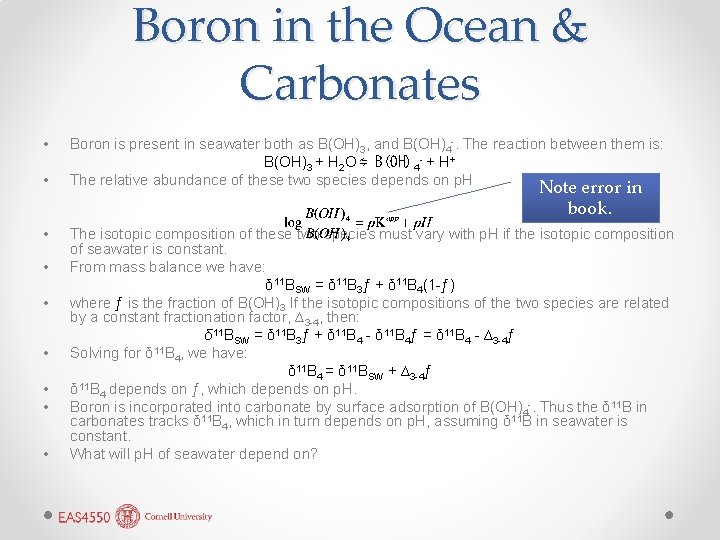

Boron in the Ocean & Carbonates • • Boron is present in seawater both as B(OH)3, and B(OH)4 -. The reaction between them is: B(OH)3 + H 2 O ⇋ B(OH) 4 - + H+ The relative abundance of these two species depends on p. H Note error in book. • • The isotopic composition of these two species must vary with p. H if the isotopic composition of seawater is constant. From mass balance we have: δ 11 BSW = δ 11 B 3ƒ + δ 11 B 4(1 -ƒ) where ƒ is the fraction of B(OH)3 If the isotopic compositions of the two species are related by a constant fractionation factor, ∆3 -4, then: δ 11 BSW = δ 11 B 3ƒ + δ 11 B 4 - δ 11 B 4ƒ = δ 11 B 4 - ∆3 -4ƒ Solving for δ 11 B 4, we have: δ 11 B 4 = δ 11 BSW + ∆3 -4ƒ δ 11 B 4 depends on ƒ, which depends on p. H. Boron is incorporated into carbonate by surface adsorption of B(OH)4 -. Thus the δ 11 B in carbonates tracks δ 11 B 4, which in turn depends on p. H, assuming δ 11 B in seawater is constant. What will p. H of seawater depend on?

Borate & Boric Acid as a function of p. H

Seawater p. H and 11 Atmospheric CO 2 from δ B • • • Pearson and Palmer (2000) measured δ 11 B in foraminifera from (ODP) cores and were able to reconstruct atmospheric CO 2 through much of the Cenozoic. Surprisingly, atmospheric CO 2 has been < 400 ppm through the Neogene, a time of significant global cooling. Much higher CO 2 levels were found in the Paleogene. This has largely been confirmed by another paleo-CO 2 proxy, δ 13 C in 37 C diunsaturated alkenones (Section 12. 8. 2; Figure 12. 43). Atmospheric CO 2 conc (397 ppm) is now higher than it has been for 35 million years.

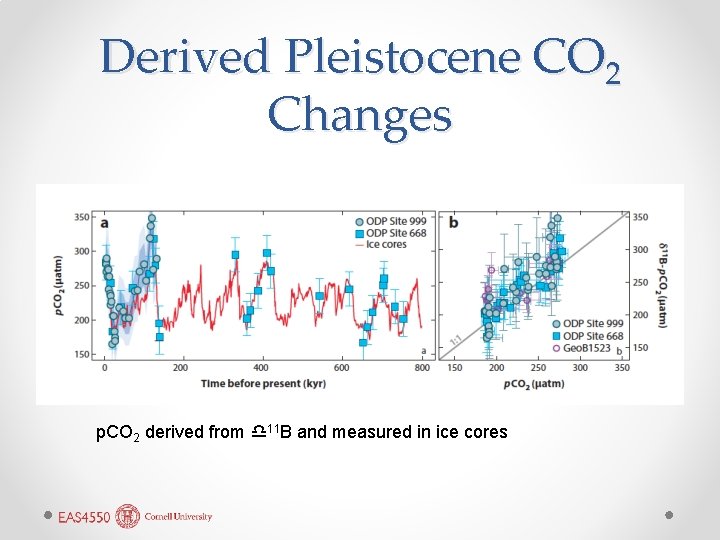

Derived Pleistocene CO 2 Changes p. CO 2 derived from d 11 B and measured in ice cores

Stable Isotopes in High Temperature Geochemistry

Where does hydrothermal water come from?

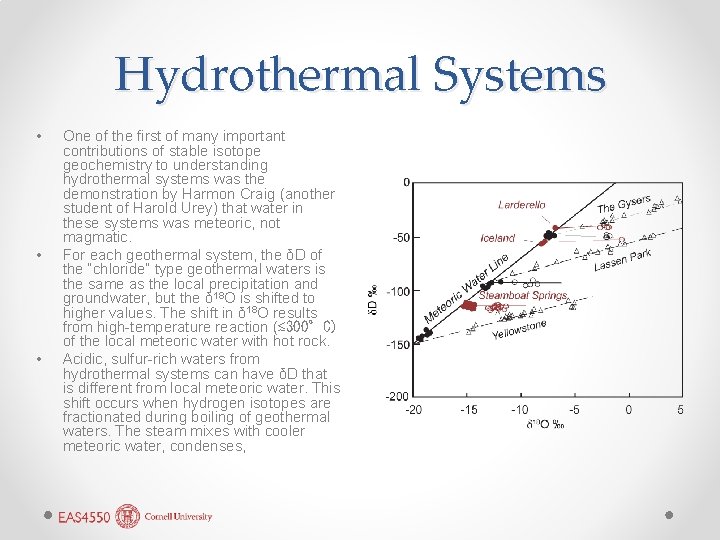

Hydrothermal Systems • • • One of the first of many important contributions of stable isotope geochemistry to understanding hydrothermal systems was the demonstration by Harmon Craig (another student of Harold Urey) that water in these systems was meteoric, not magmatic. For each geothermal system, the δD of the “chloride” type geothermal waters is the same as the local precipitation and groundwater, but the δ 18 O is shifted to higher values. The shift in δ 18 O results from high-temperature reaction (≲ 300°C) of the local meteoric water with hot rock. Acidic, sulfur-rich waters from hydrothermal systems can have δD that is different from local meteoric water. This shift occurs when hydrogen isotopes are fractionated during boiling of geothermal waters. The steam mixes with cooler meteoric water, condenses,

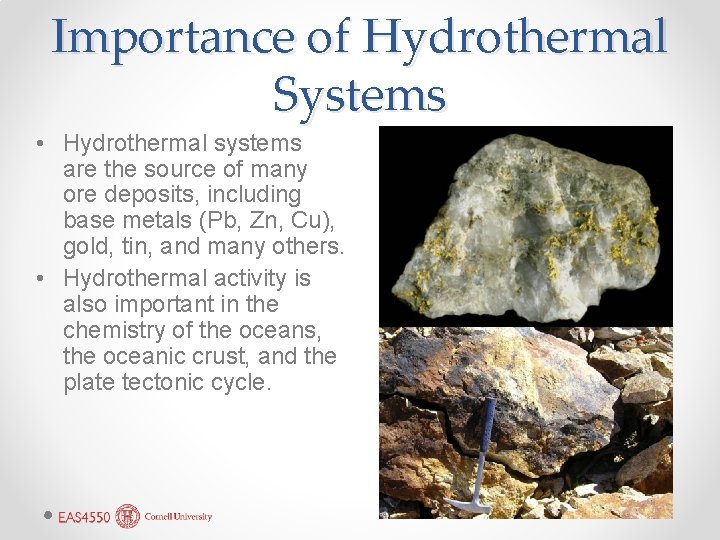

Importance of Hydrothermal Systems • Hydrothermal systems are the source of many ore deposits, including base metals (Pb, Zn, Cu), gold, tin, and many others. • Hydrothermal activity is also important in the chemistry of the oceans, the oceanic crust, and the plate tectonic cycle.

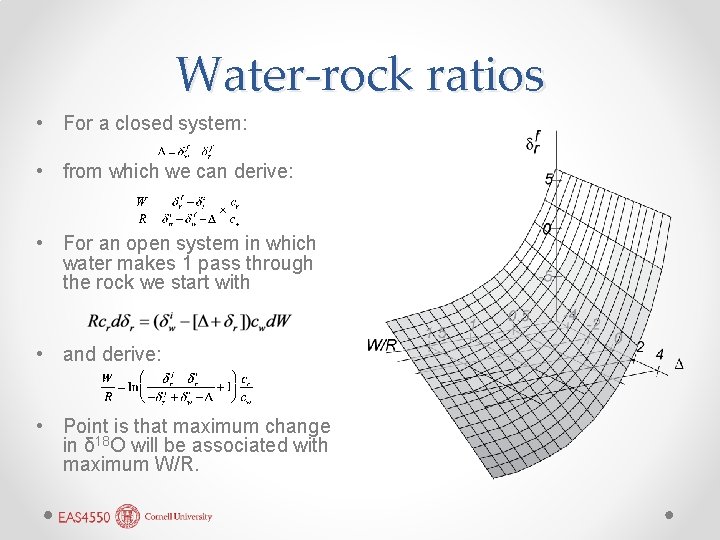

Water-rock ratios • For a closed system: • from which we can derive: • For an open system in which water makes 1 pass through the rock we start with • and derive: • Point is that maximum change in δ 18 O will be associated with maximum W/R.

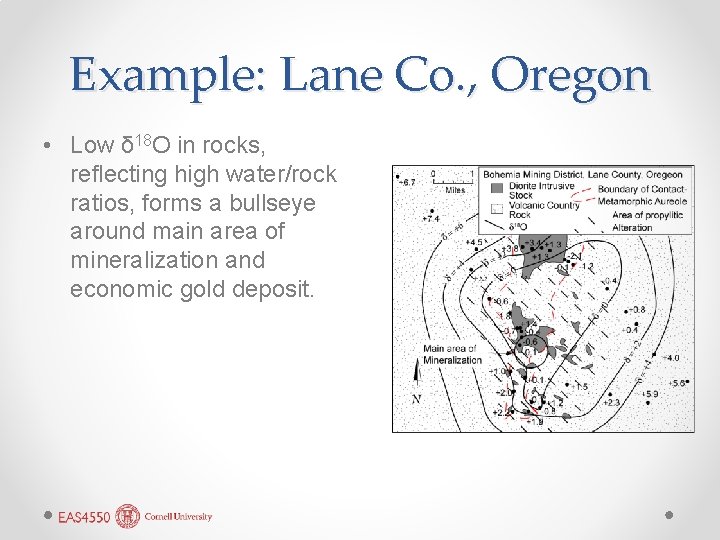

Example: Lane Co. , Oregon • Low δ 18 O in rocks, reflecting high water/rock ratios, forms a bullseye around main area of mineralization and economic gold deposit.

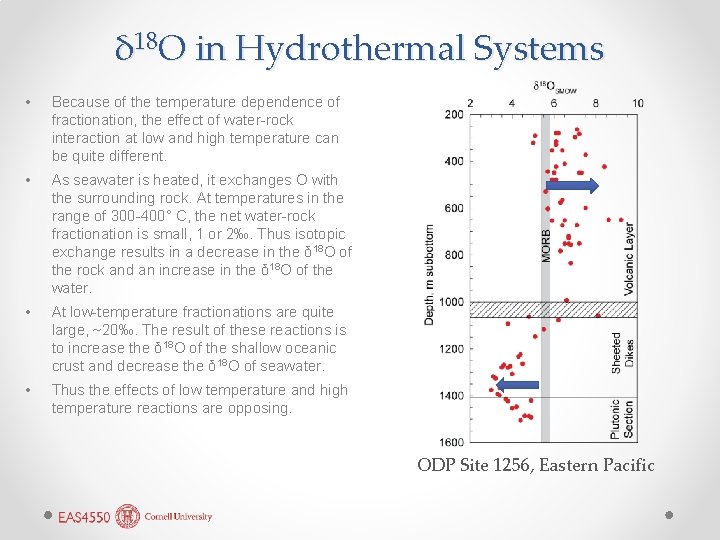

δ 18 O in Hydrothermal Systems • Because of the temperature dependence of fractionation, the effect of water-rock interaction at low and high temperature can be quite different. • As seawater is heated, it exchanges O with the surrounding rock. At temperatures in the range of 300 -400° C, the net water-rock fractionation is small, 1 or 2‰. Thus isotopic exchange results in a decrease in the δ 18 O of the rock and an increase in the δ 18 O of the water. • At low-temperature fractionations are quite large, ~20‰. The result of these reactions is to increase the δ 18 O of the shallow oceanic crust and decrease the δ 18 O of seawater. • Thus the effects of low temperature and high temperature reactions are opposing. ODP Site 1256, Eastern Pacific

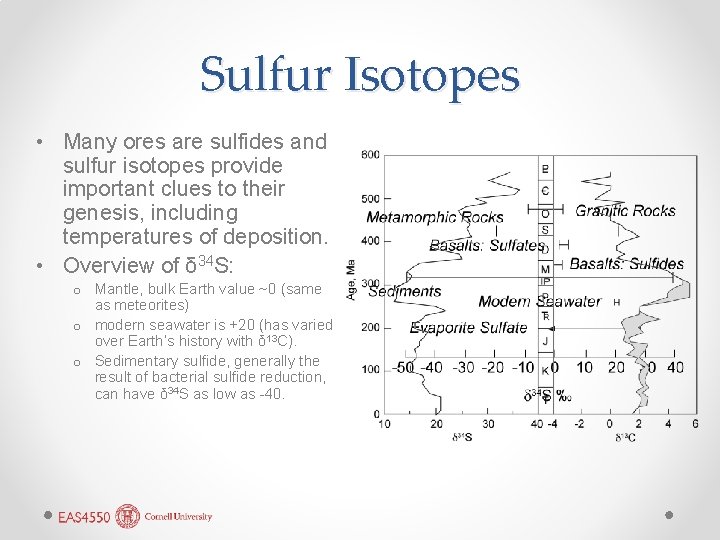

Sulfur Isotopes • Many ores are sulfides and sulfur isotopes provide important clues to their genesis, including temperatures of deposition. • Overview of δ 34 S: o Mantle, bulk Earth value ~0 (same as meteorites) o modern seawater is +20 (has varied over Earth’s history with δ 13 C). o Sedimentary sulfide, generally the result of bacterial sulfide reduction, can have δ 34 S as low as -40.

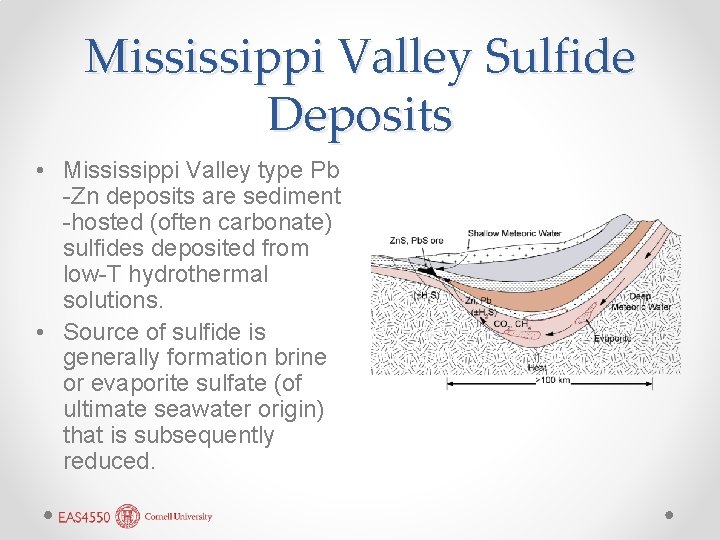

Mississippi Valley Sulfide Deposits • Mississippi Valley type Pb -Zn deposits are sediment -hosted (often carbonate) sulfides deposited from low-T hydrothermal solutions. • Source of sulfide is generally formation brine or evaporite sulfate (of ultimate seawater origin) that is subsequently reduced.

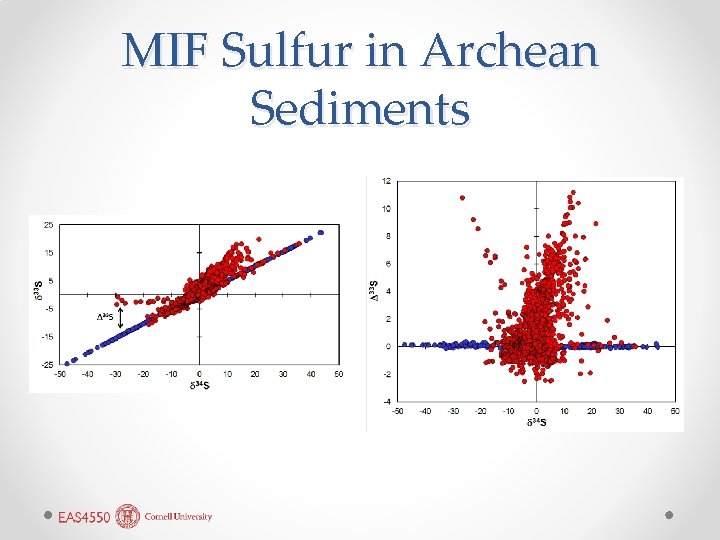

MIF Sulfur in Archean Sediments

• • • Archean MIF Sulfide and the GOE Most studies report only 34 S/32 S as δ 34 S, but sulfur has two other isotopes 33 S and 36 S. We expect δ 33 S, δ 34 S, and δ 36 S to all correlate strongly, and they almost always do (hence few bother to measure 33 S or 36 S). When Farquhar measured δ 33 S and δ 34 S in Archean sulfides, he found mass independent fractionations. Experiments show that SO 2 photodissociated by UV light can be massindependently fractionated. Interpretation: prior to 2. 3 Ga, UV light was able to penetrate into the lower atmosphere and dissociate SO 2. In the modern Earth, stratospheric ozone restricts UV penetration into the troposphere(sulfur rarely reaches the stratosphere, so little MIF fractionation). This provides strong supporting evidence for the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) at 2. 3 Ga.

Stable Isotopes in the Mantle and Magmas

Oxygen in the Mantle • δ 18 O in olivine in peridotites is fairly uniform at +5. 2‰. • Clinopyroxenes slightly heaver, ~+5. 6‰. • Fresh MORB are typically +5. 7‰ • Some OIB and IAV show deviations from this. • Bottom line: no more than tenths of per mil fractionations at high T. o Igneous rocks with δ 18 O very different from ~5. 6‰ show evidence of low-T surface processing. o At high-T, δ 18 O isotopes can effectively be used as tracers like radiogenic isotopes.

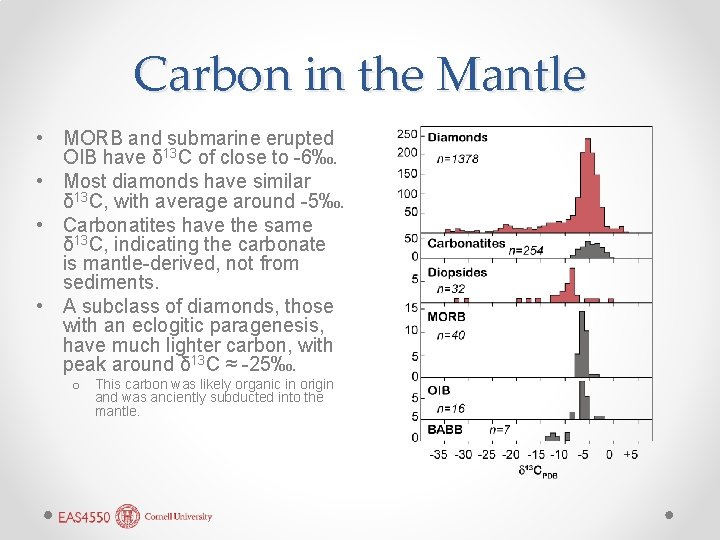

Carbon in the Mantle • MORB and submarine erupted OIB have δ 13 C of close to -6‰. • Most diamonds have similar δ 13 C, with average around -5‰. • Carbonatites have the same δ 13 C, indicating the carbonate is mantle-derived, not from sediments. • A subclass of diamonds, those with an eclogitic paragenesis, have much lighter carbon, with peak around δ 13 C ≈ -25‰. o This carbon was likely organic in origin and was anciently subducted into the mantle.

18 δ O in Crystallizing Magmas • Fractionations between silicates and silicate magmas are small, but they can be a bit larger when oxides like magnetite and rutile crystalize. • We imagine two paths: equilibrium and fractional, the latter more likely. • For fractional crystallization: • In both theory and observation, there will be not much more than 1 or 2‰ change in δ 18 O.

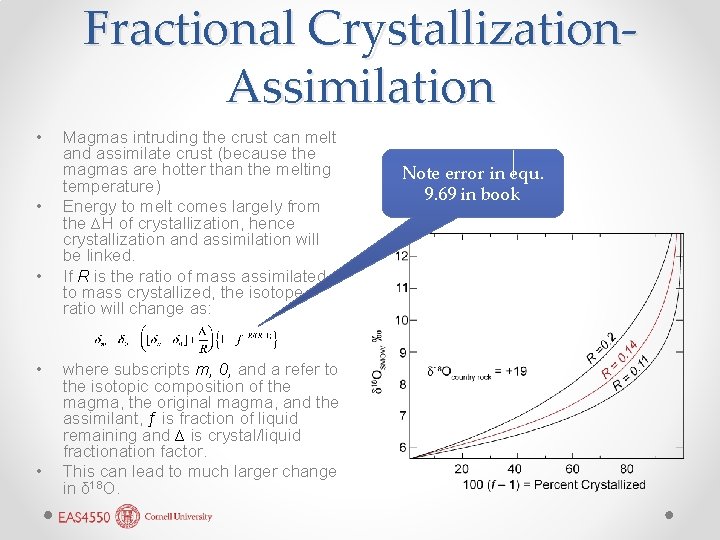

Fractional Crystallization. Assimilation • • • Magmas intruding the crust can melt and assimilate crust (because the magmas are hotter than the melting temperature) Energy to melt comes largely from the ∆H of crystallization, hence crystallization and assimilation will be linked. If R is the ratio of mass assimilated to mass crystallized, the isotope ratio will change as: where subscripts m, 0, and a refer to the isotopic composition of the magma, the original magma, and the assimilant, ƒ is fraction of liquid remaining and ∆ is crystal/liquid fractionation factor. This can lead to much larger change in δ 18 O. Note error in equ. 9. 69 in book

- Slides: 36