SQL Unit 2 Simple SQL Queries with Selection

- Slides: 155

SQL Unit 2 Simple SQL Queries with Selection and Projection Kirk Scott 1

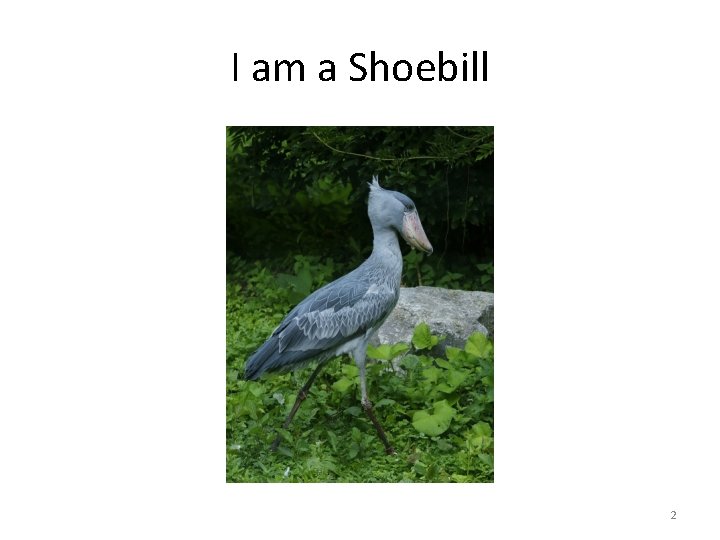

I am a Shoebill 2

3

4

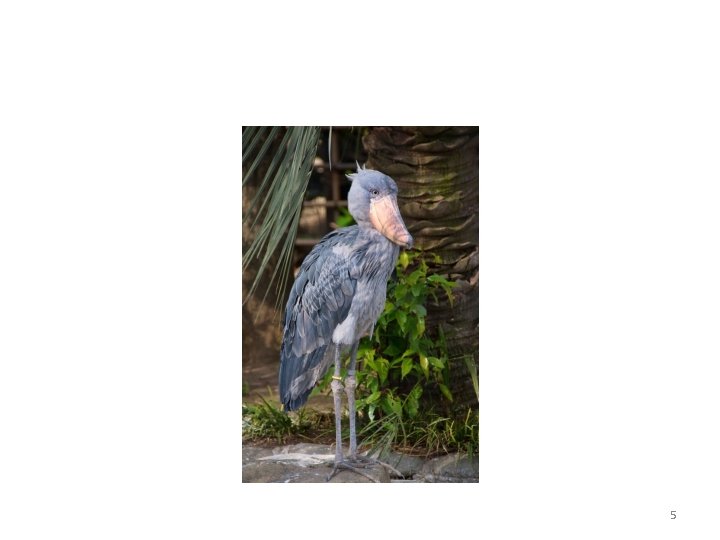

5

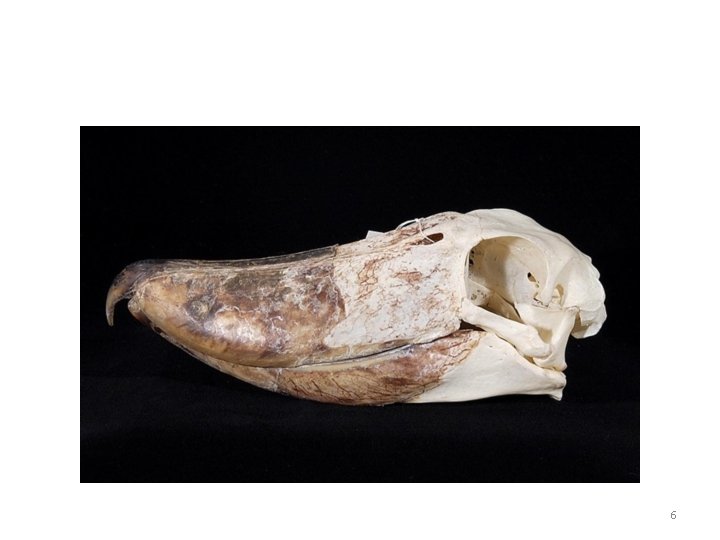

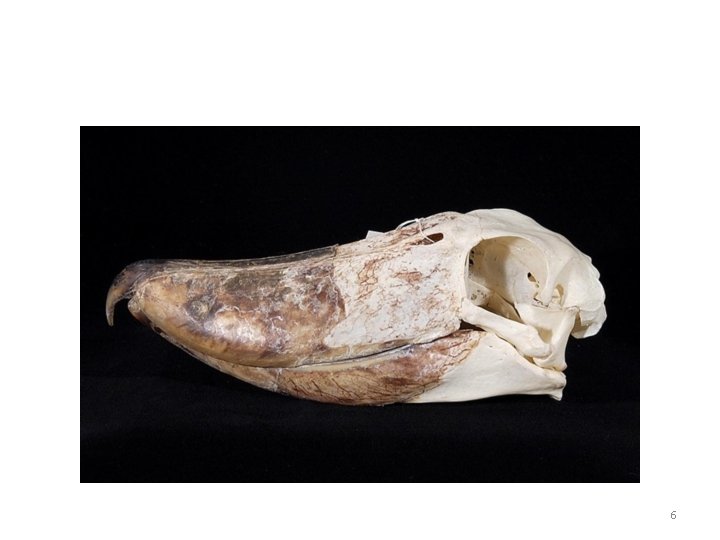

6

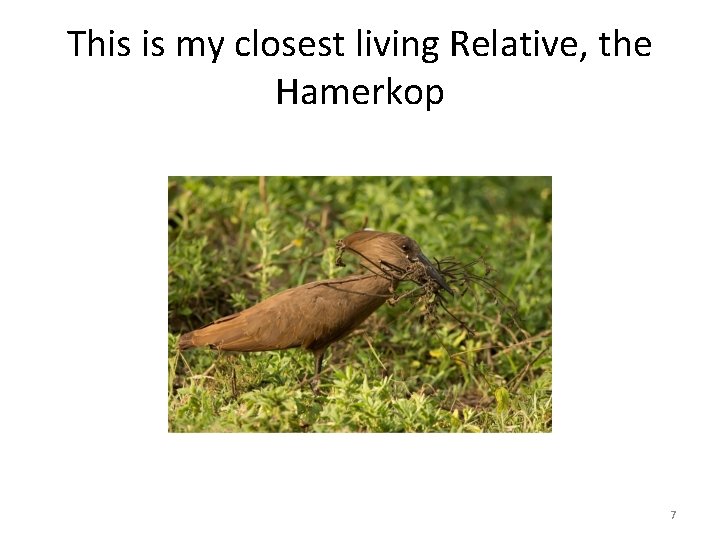

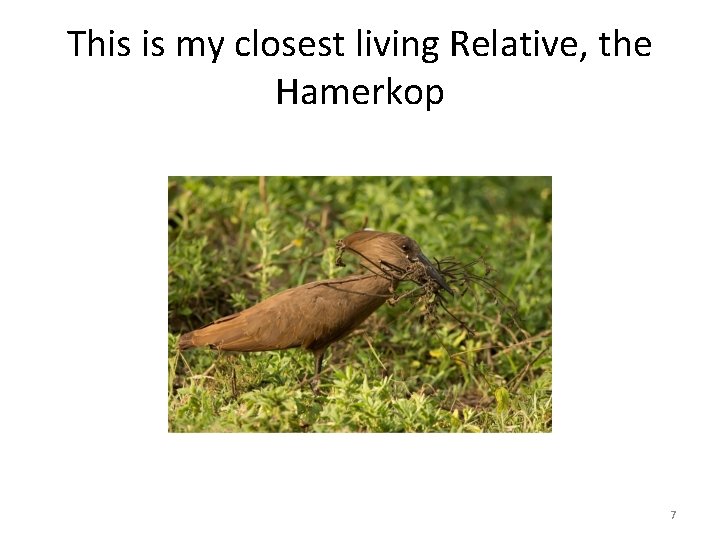

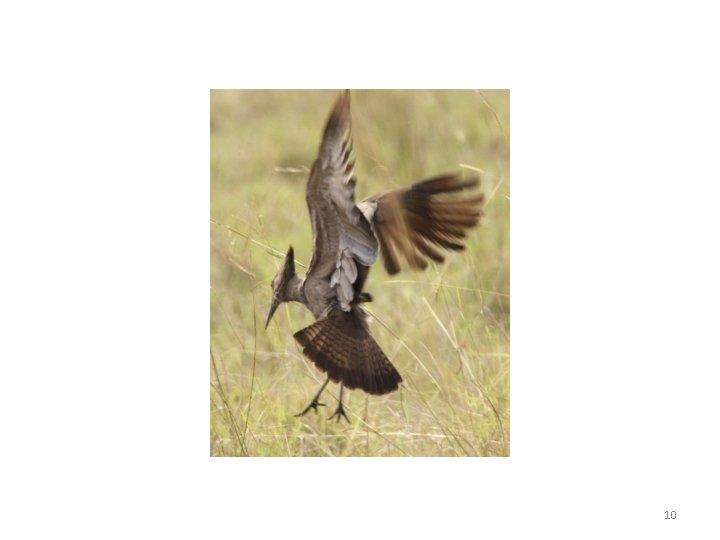

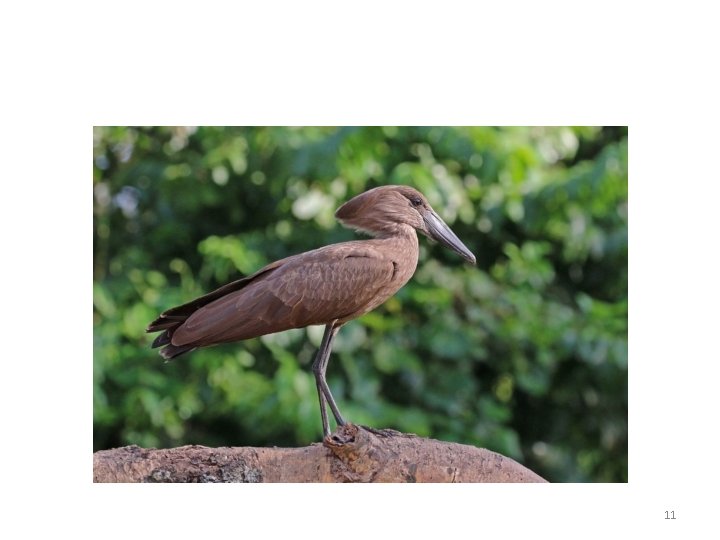

This is my closest living Relative, the Hamerkop 7

8

9

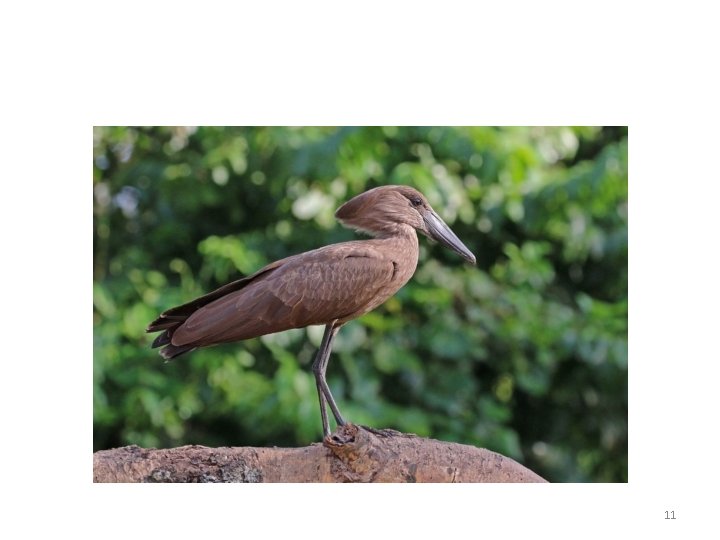

10

11

12

• 2. 0 The Sample Database and MS Access SQL • 2. 1 Description of the Sample Database • 2. 2 The Keywords SELECT and FROM; Queries with Projection • 2. 3 The Keywords WHERE, AND, OR, NOT, and NULL; Queries with Selection • Outline continued on next overhead 13

• 2. 4 The Keyword LIKE • 2. 5 The Keywords ORDER BY, ASC, and DESC; Ordering the Results of Queries • 2. 6 The Keyword DISTINCT • 2. 7 The Keyword COUNT; Counting the Number of Rows in a Result • 2. 8 The Keyword AS; Aliases 14

2. 0 The Sample Database and MS Access SQL 15

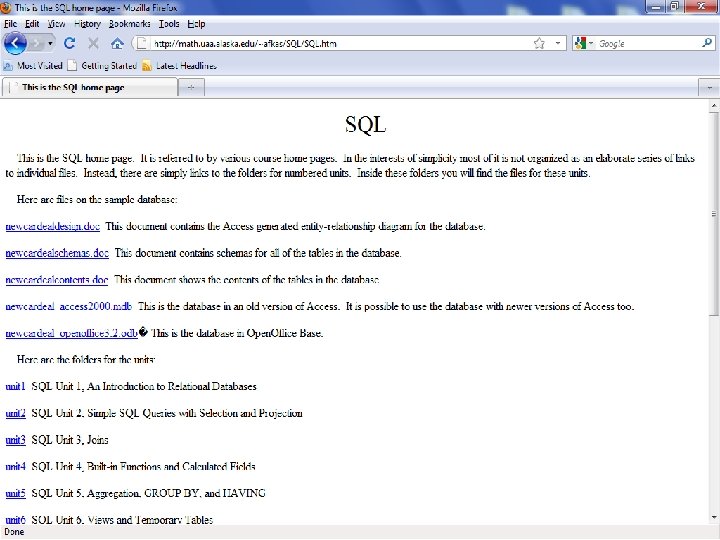

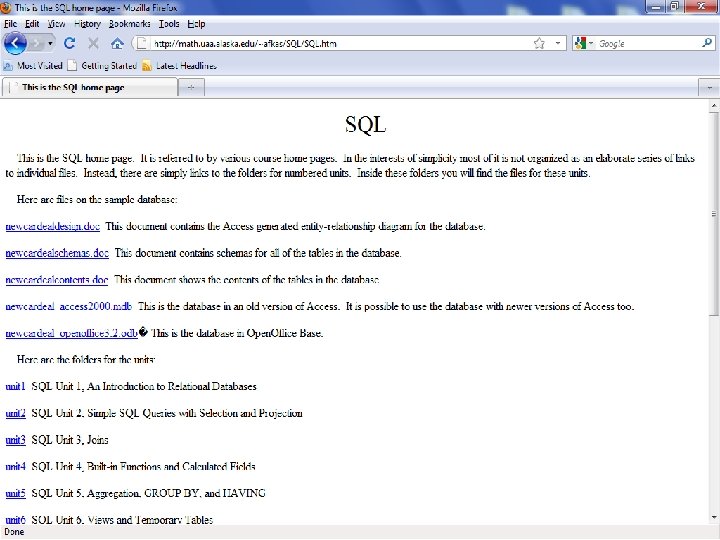

2. 0. 1 Downloading and Opening the Example Database • • • Go to this Web address: http: //math. uaa. alaska. edu/~afkas. Follow the CSCE 360 link This will lead you to the link SQL. htm. Follow it. This is where you’ll find the newcardeal_access 2000. mdb 16

17

• Download and save the db • Feel free to save it in an updated version • It’s given in a very old version in case anyone is using old MS software • The design and implementation are still valid and should save into a new version without any problems 18

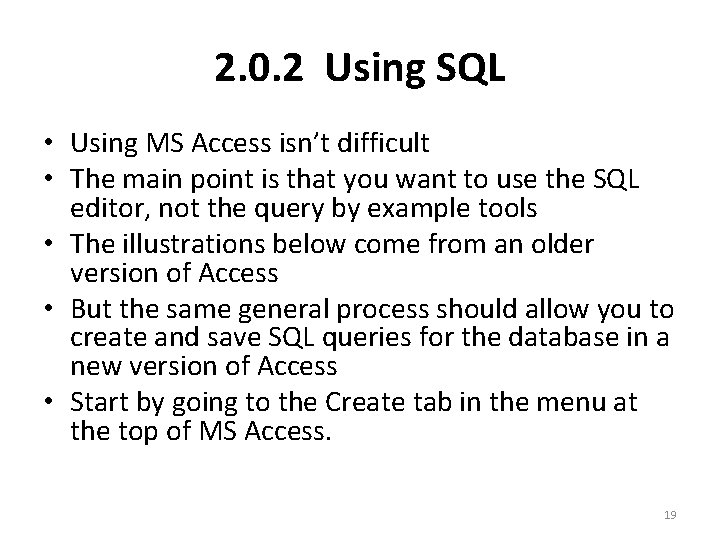

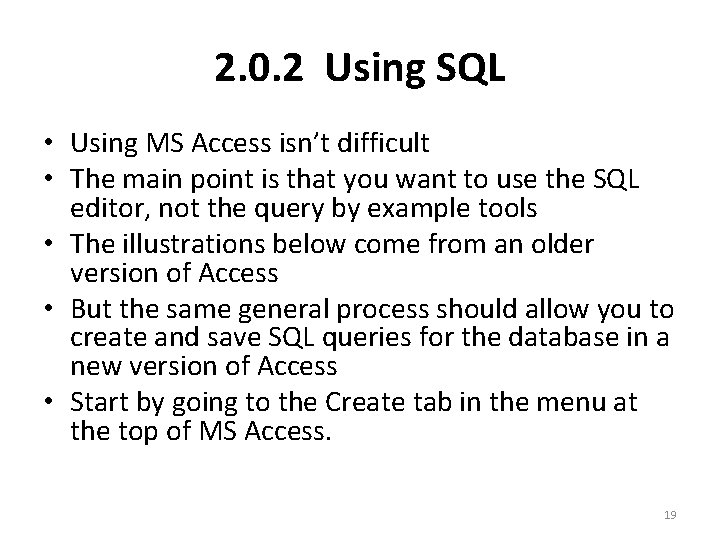

2. 0. 2 Using SQL • Using MS Access isn’t difficult • The main point is that you want to use the SQL editor, not the query by example tools • The illustrations below come from an older version of Access • But the same general process should allow you to create and save SQL queries for the database in a new version of Access • Start by going to the Create tab in the menu at the top of MS Access. 19

20

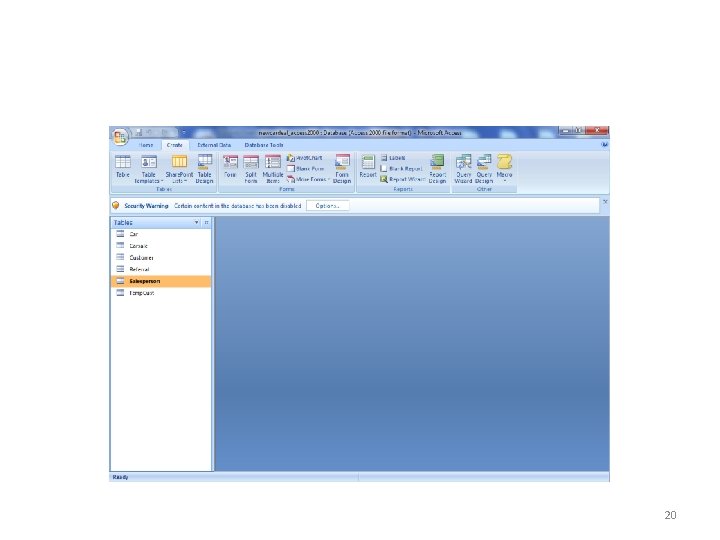

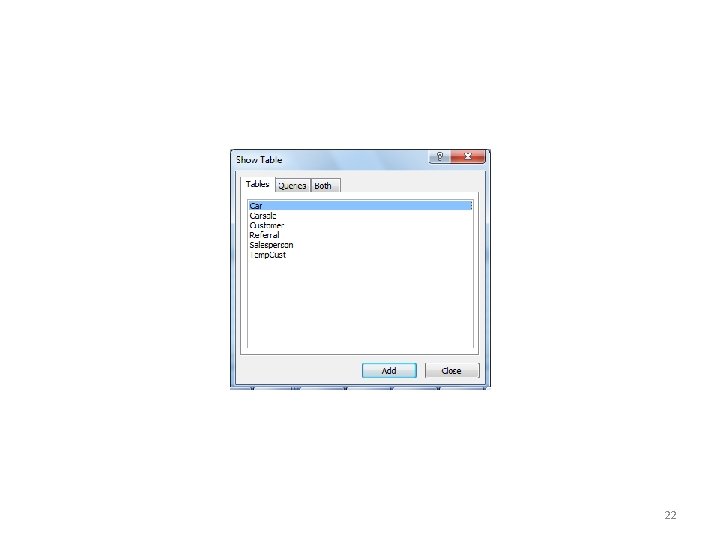

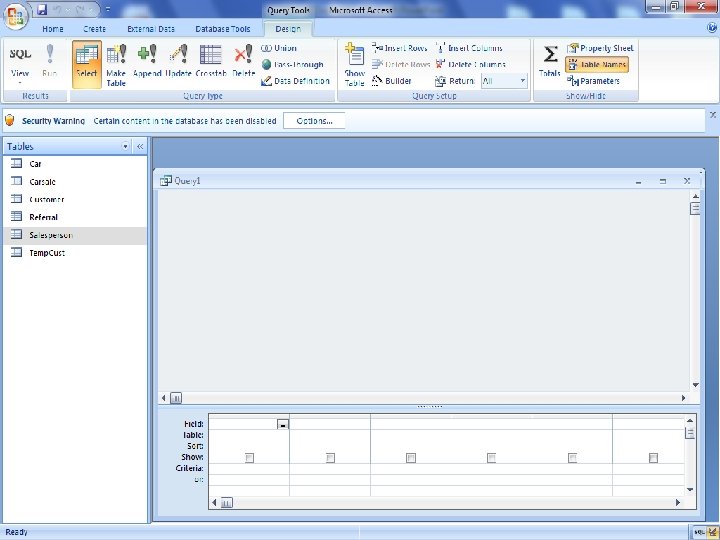

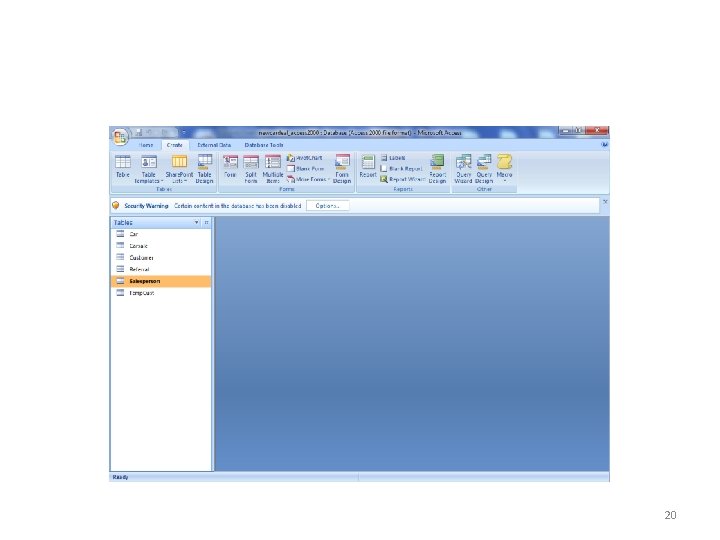

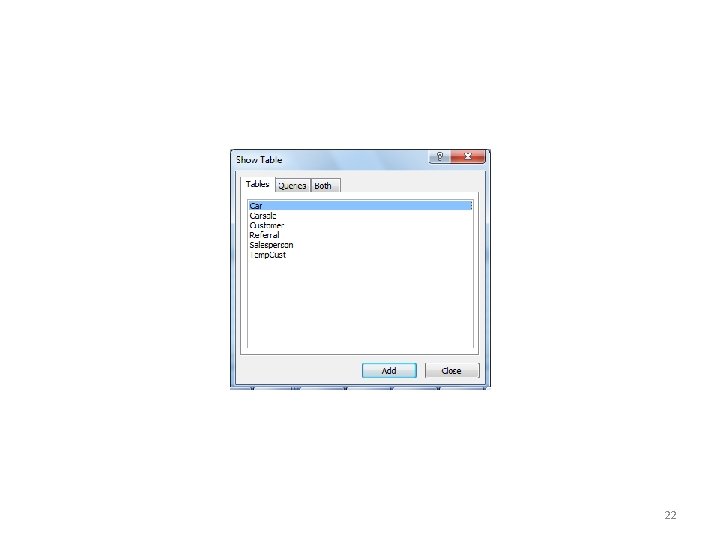

• Click on the Query Design option on the right. • A Show Table window should pop up. 21

22

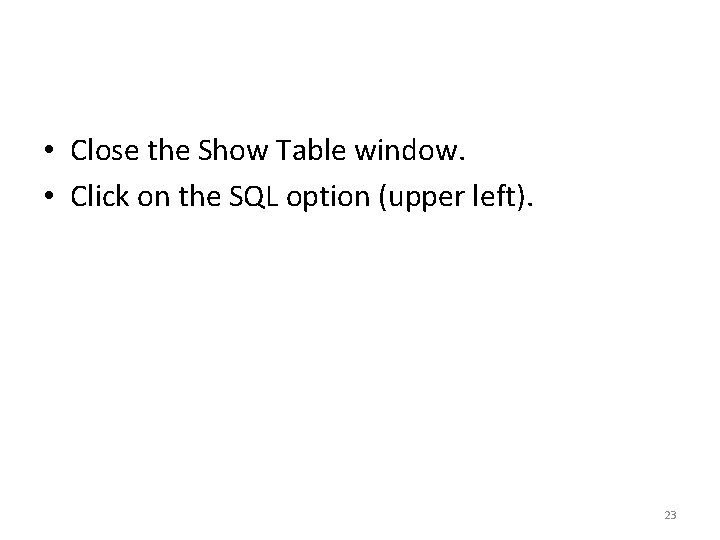

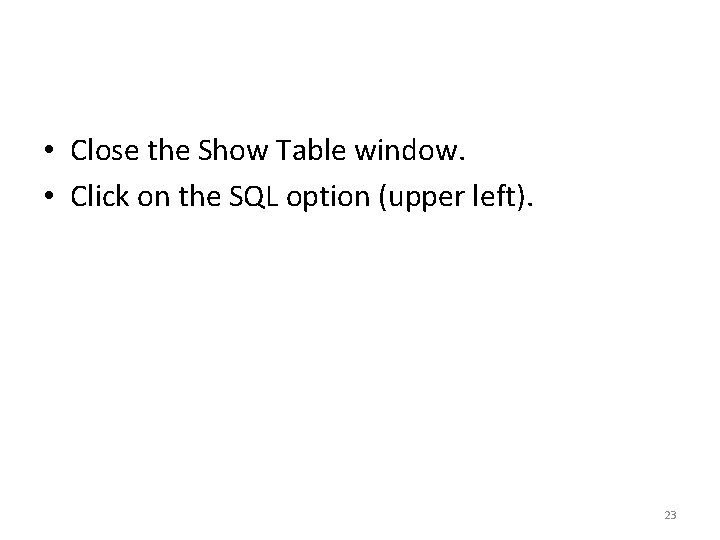

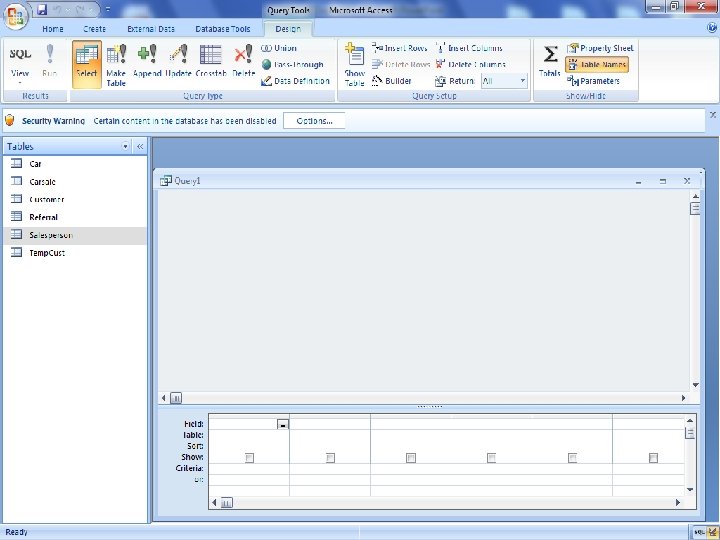

• Close the Show Table window. • Click on the SQL option (upper left). 23

24

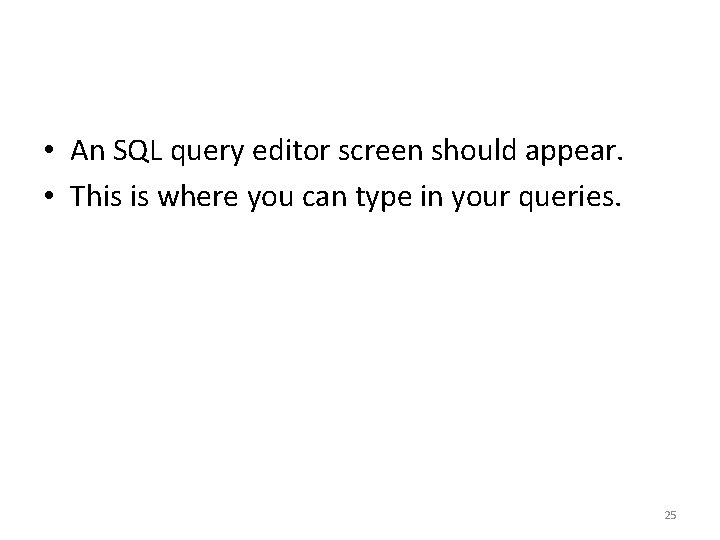

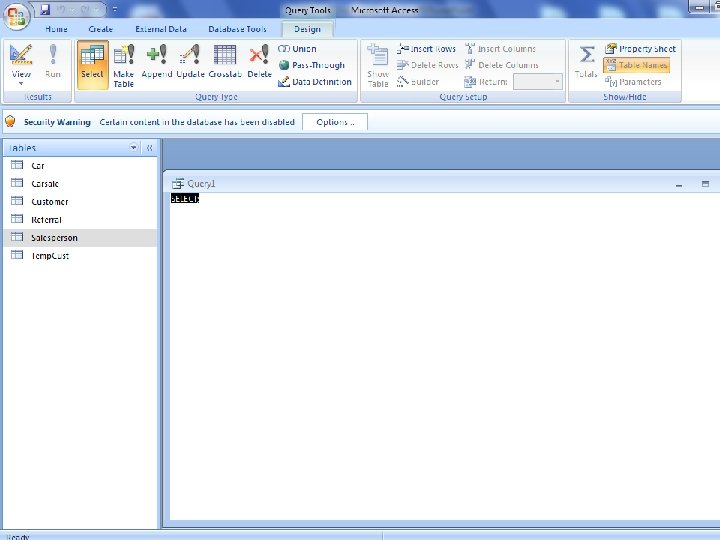

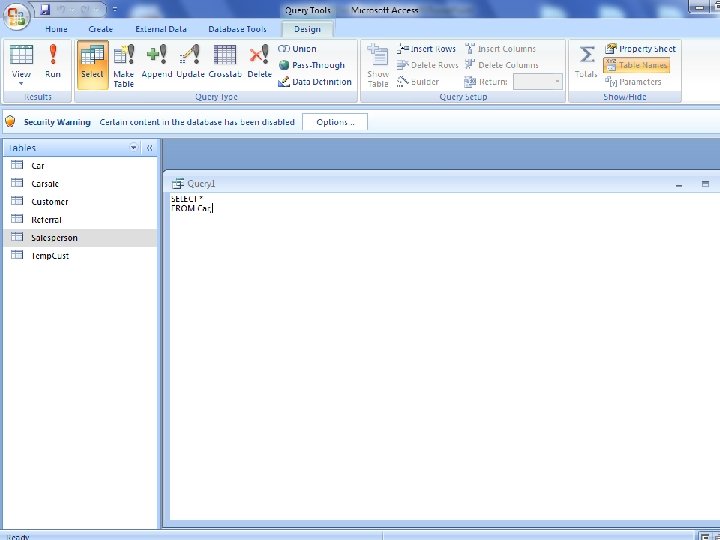

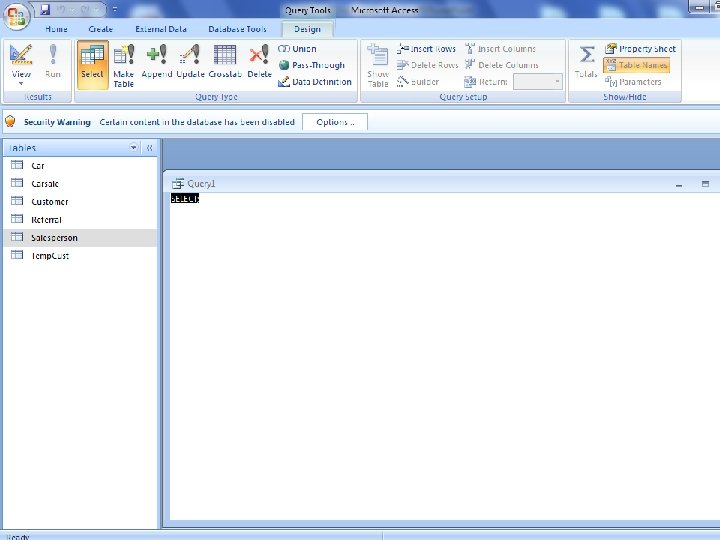

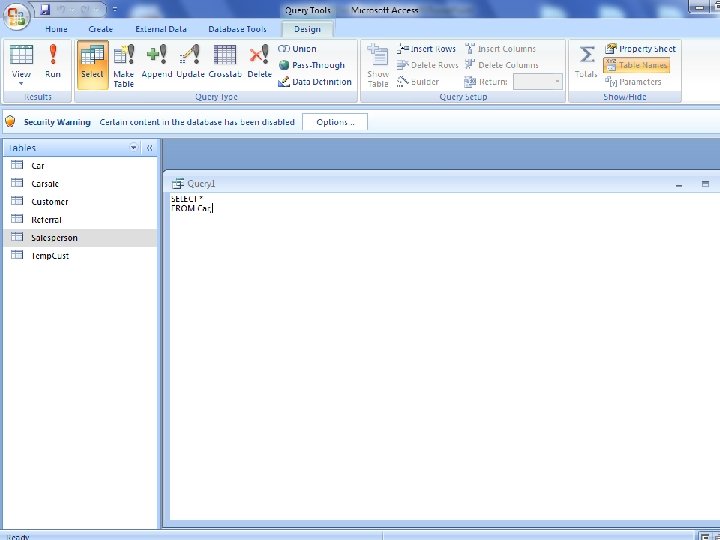

• An SQL query editor screen should appear. • This is where you can type in your queries. 25

26

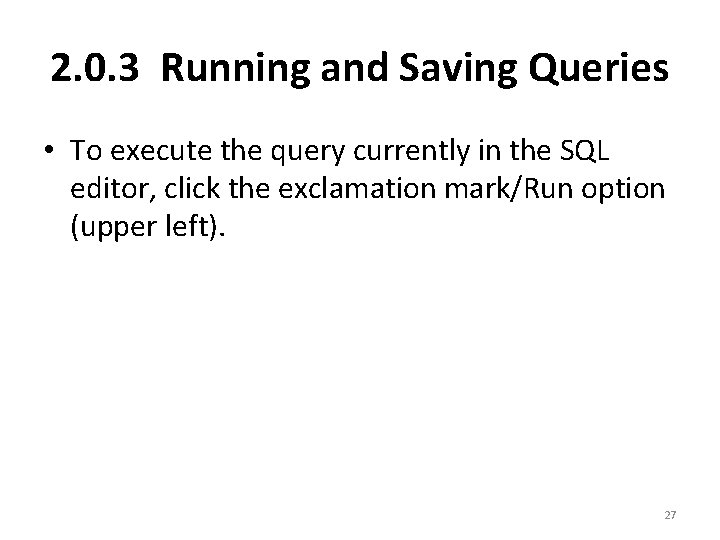

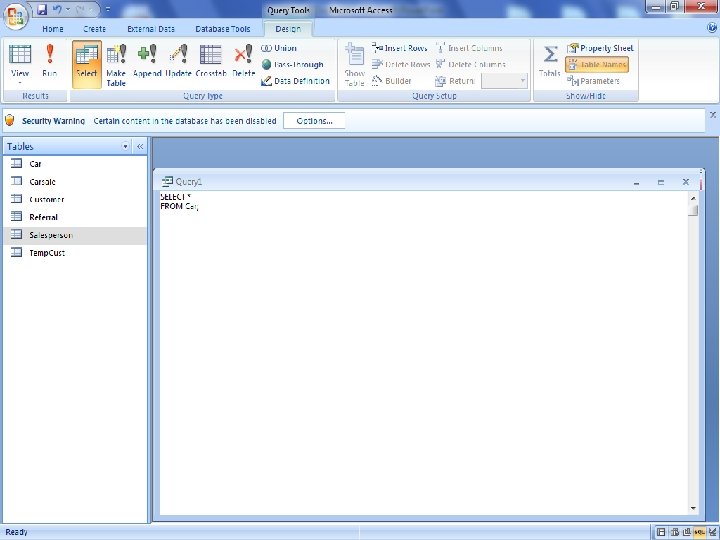

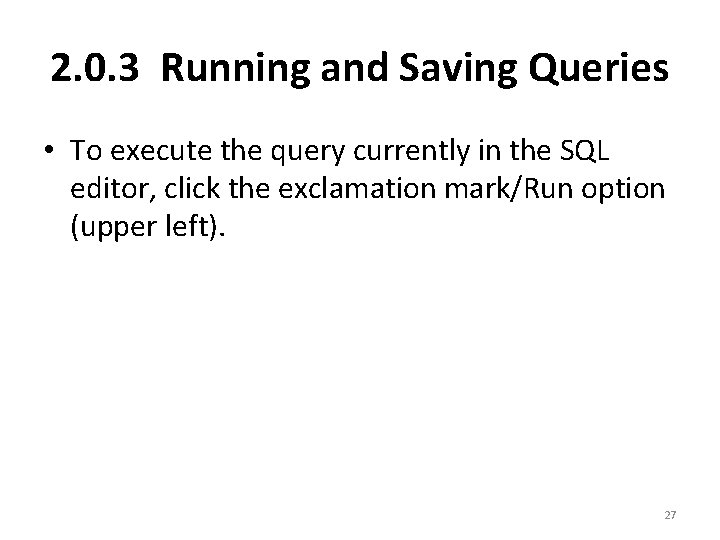

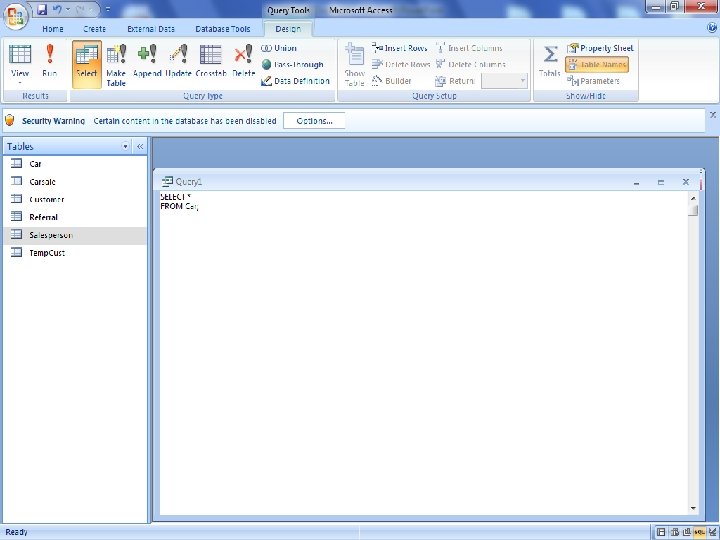

2. 0. 3 Running and Saving Queries • To execute the query currently in the SQL editor, click the exclamation mark/Run option (upper left). 27

28

29

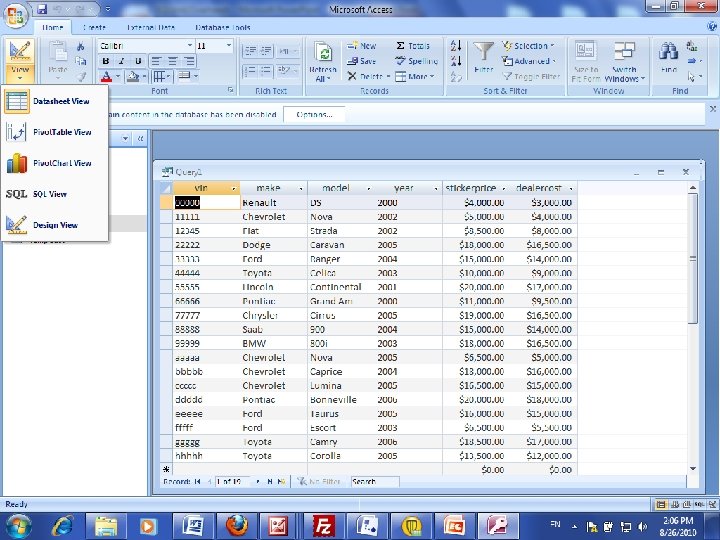

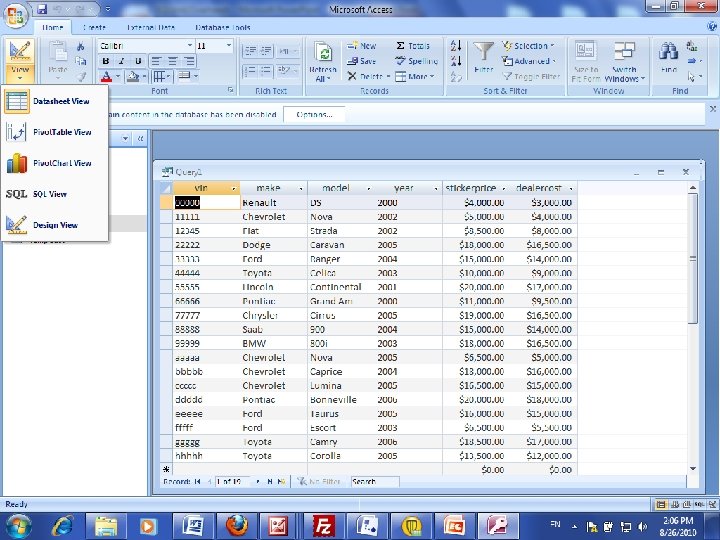

• Return from the results of the query back to the design by clicking on the architect’s triangle (upper left). • Restore the SQL view by clicking on the View option and then clicking on SQL. 30

31

• Close the query by clicking on the X in its upper right hand corner. 32

33

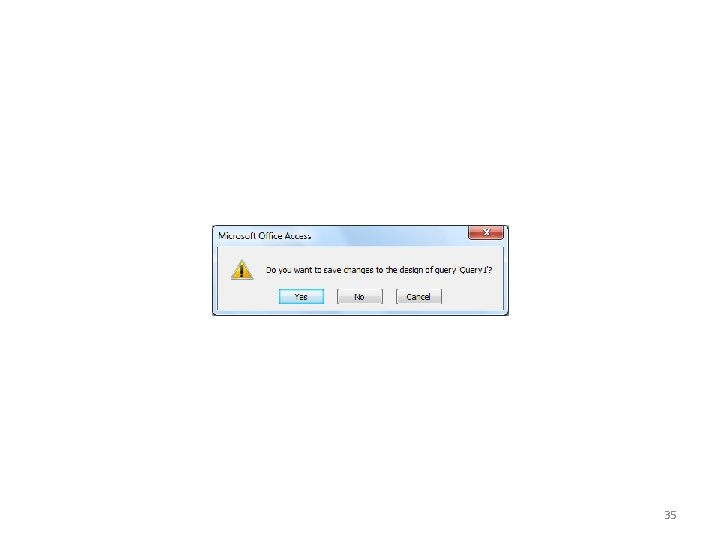

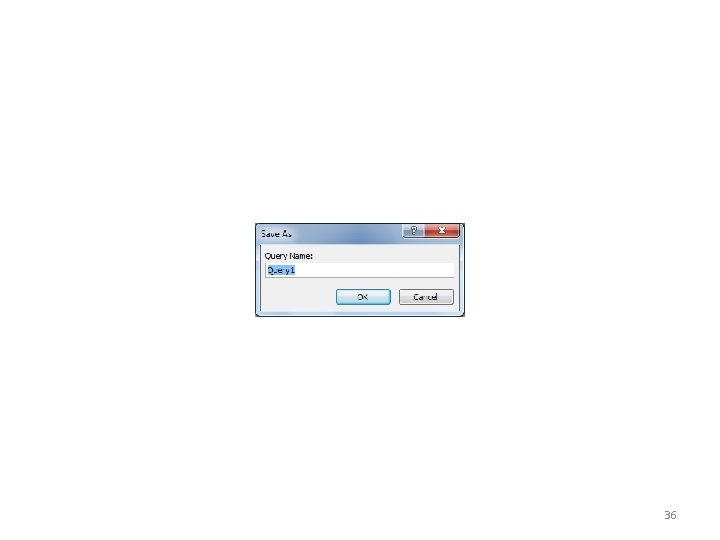

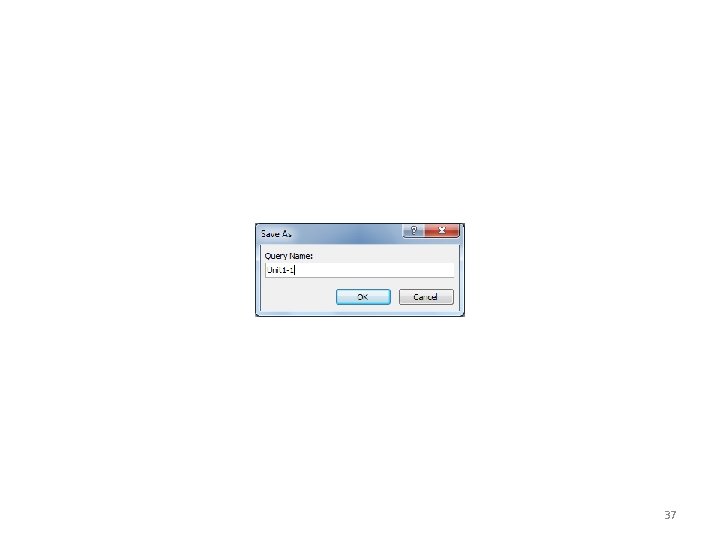

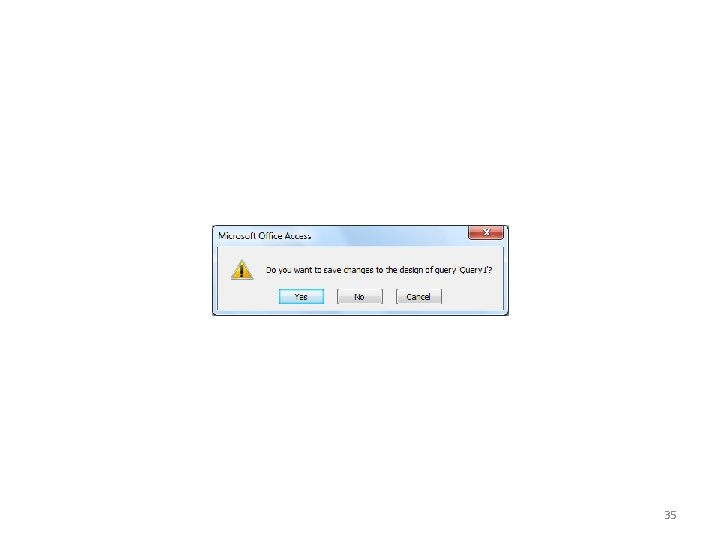

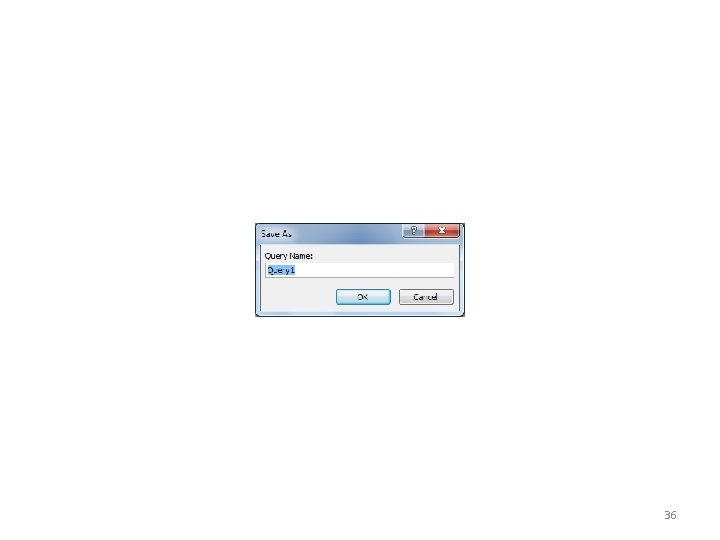

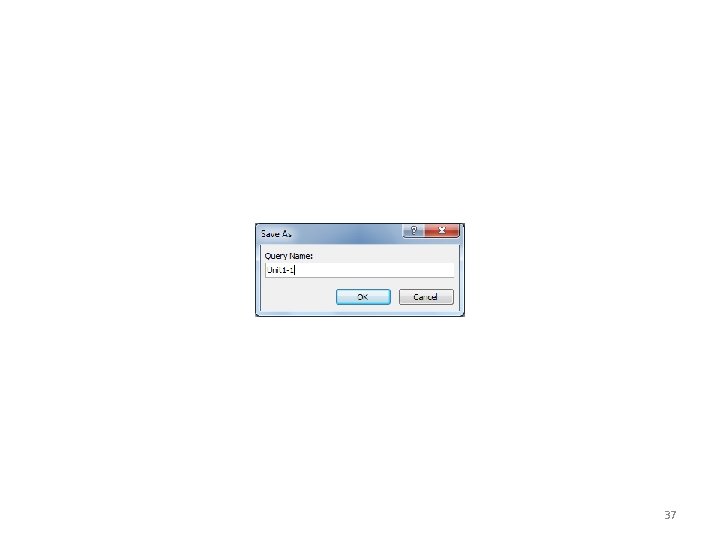

• You will be prompted whether you want to save it. • Click the Yes button. • Give the query a name. 34

35

36

37

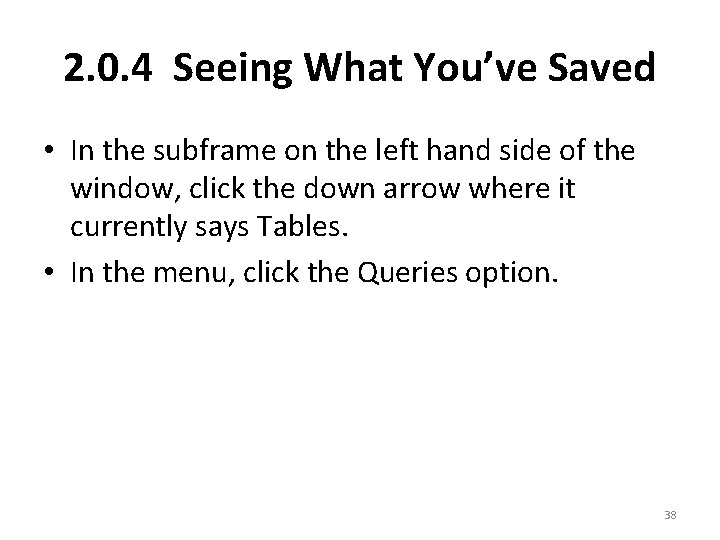

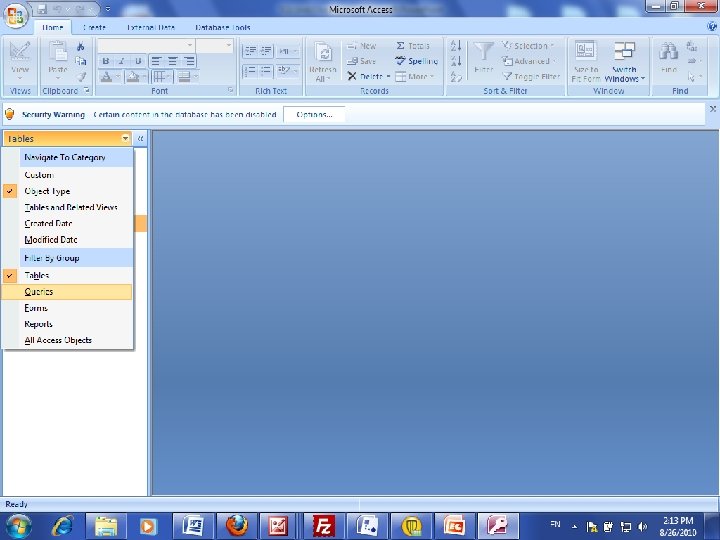

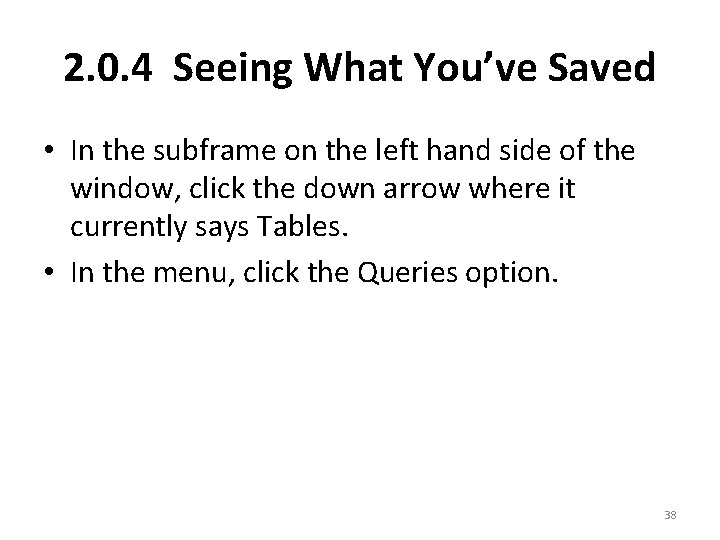

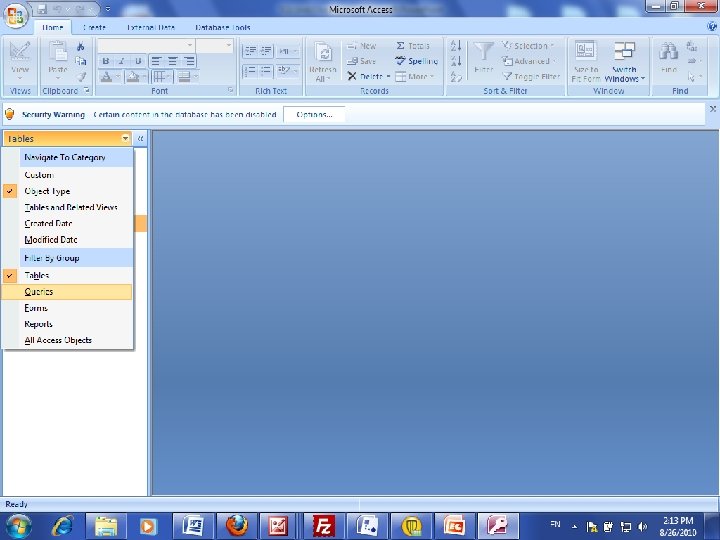

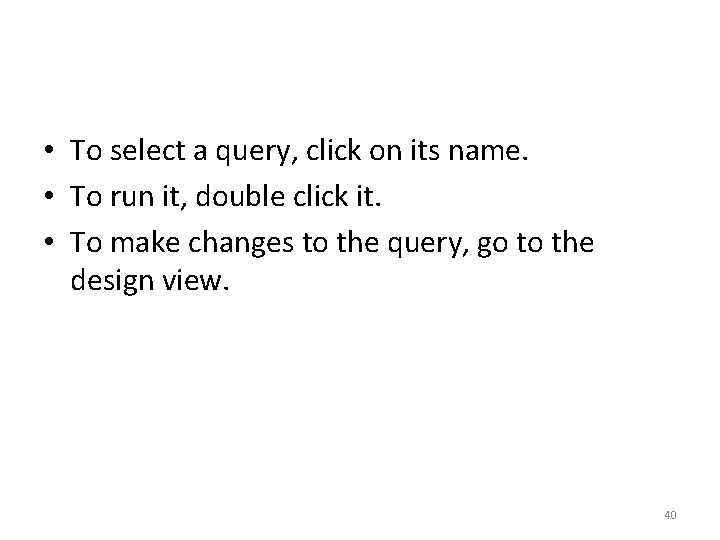

2. 0. 4 Seeing What You’ve Saved • In the subframe on the left hand side of the window, click the down arrow where it currently says Tables. • In the menu, click the Queries option. 38

39

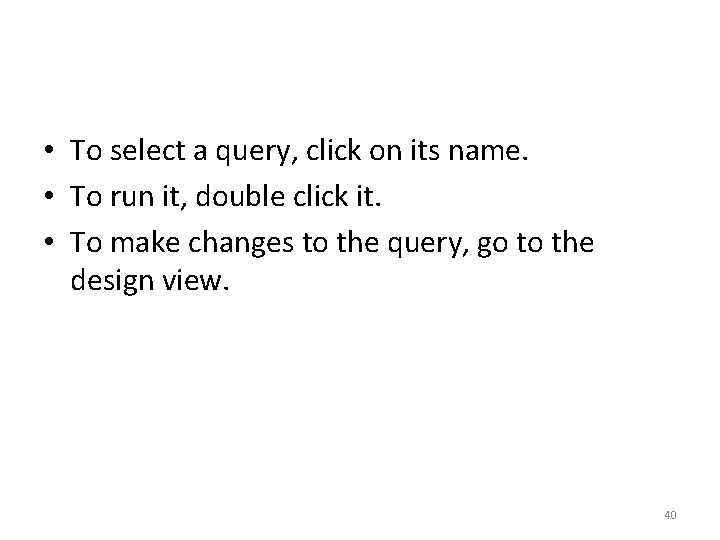

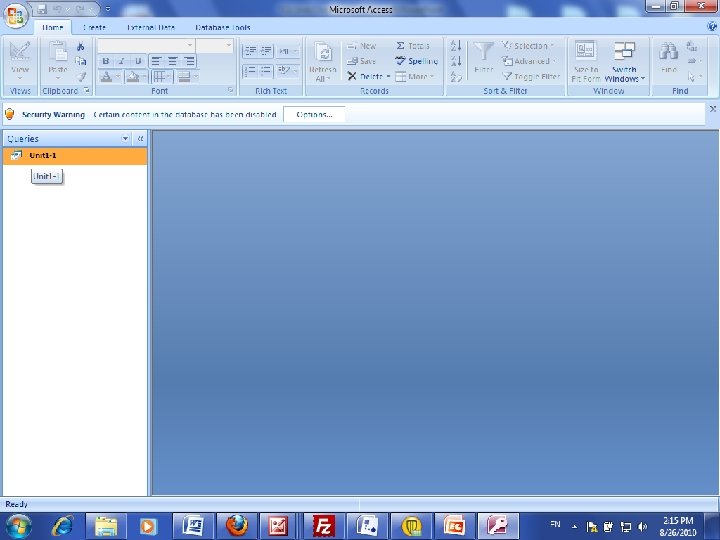

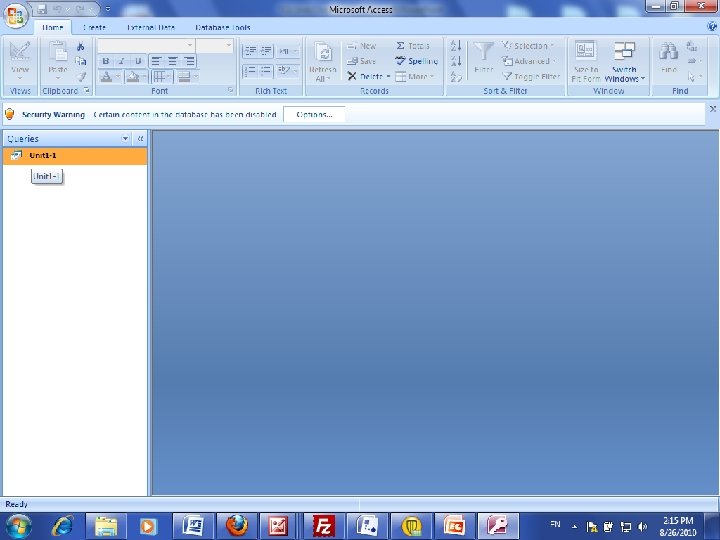

• To select a query, click on its name. • To run it, double click it. • To make changes to the query, go to the design view. 40

41

2. 0. 5 Saving the Database with Changes • Go to the Office button. • Click the Save or Save As option. 42

2. 1 Description of the Sample Database 43

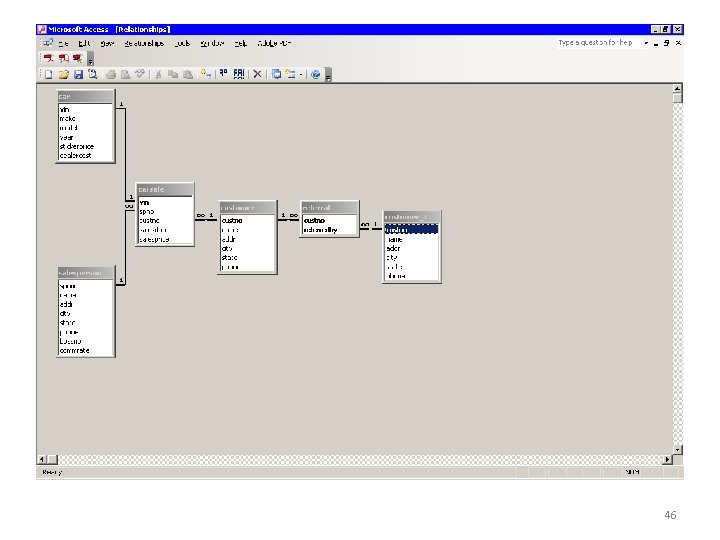

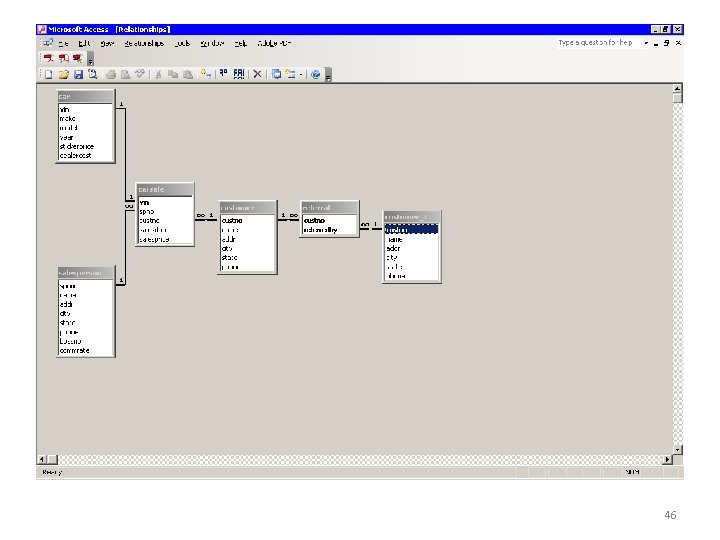

2. 1. 1 Design • All of the example queries used to explain SQL in the remainder of these notes will be based on the car dealership database. • What follows is the kind of entity relationship diagram that Microsoft Access will generate for a database. 44

• In this diagram, infinity signs are used in place of crows' feet. • The Salesperson table is in a relationship with itself, but that doesn't show in the diagram. • The Customer table is in a many-to-many relationship with itself, through the Referral table, and this is shown by means of two copies of the Customer table. 45

46

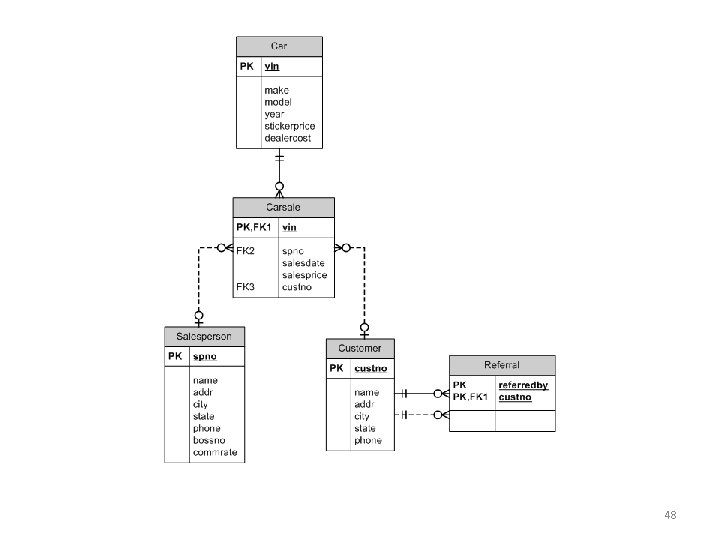

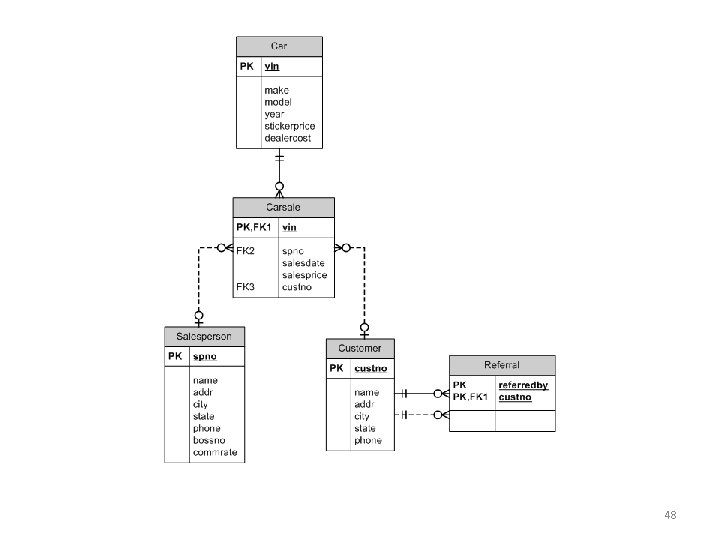

• What follows is an entity relationship diagram drawn with Microsoft Visio. • Visio uses slightly more complicated symbols than simple crows’ feet. • However, overall, the diagram may be somewhat easier to read than the one generated by Access. 47

48

2. 1. 2 Schemas • Following is a listing of the schemas for the tables in the car dealership database. • The types and sizes of fields are shown, along with the primary and foreign keys. 49

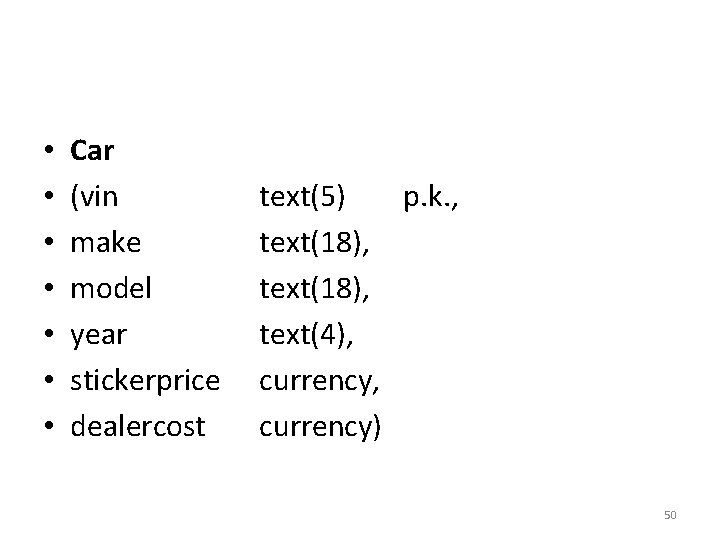

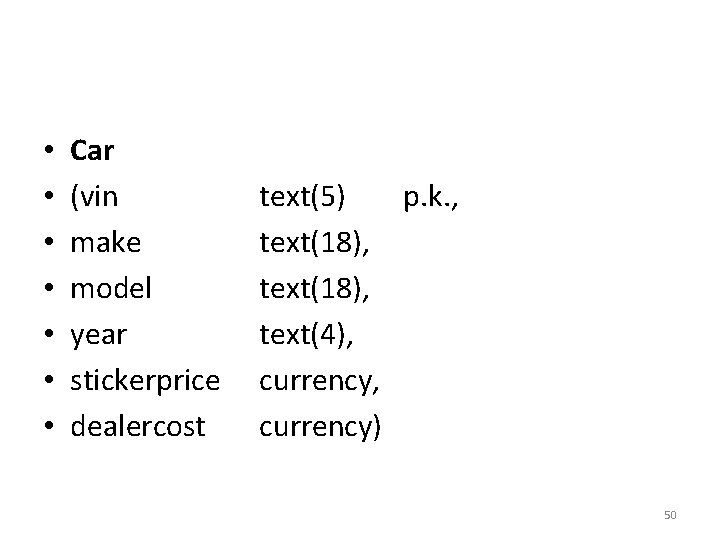

• • Car (vin make model year stickerprice dealercost text(5) p. k. , text(18), text(4), currency) 50

• • • Carsale (vin spno custno salesdate salesprice text(5) p. k. , f. k. text(5) f. k. , date/time, currency) 51

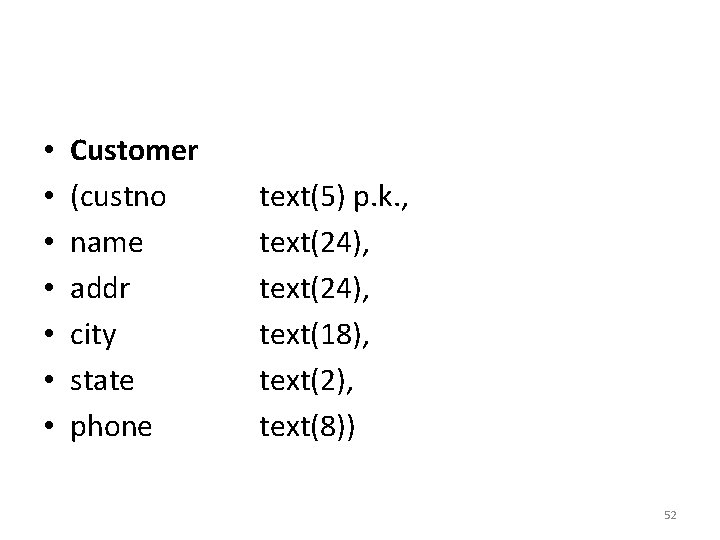

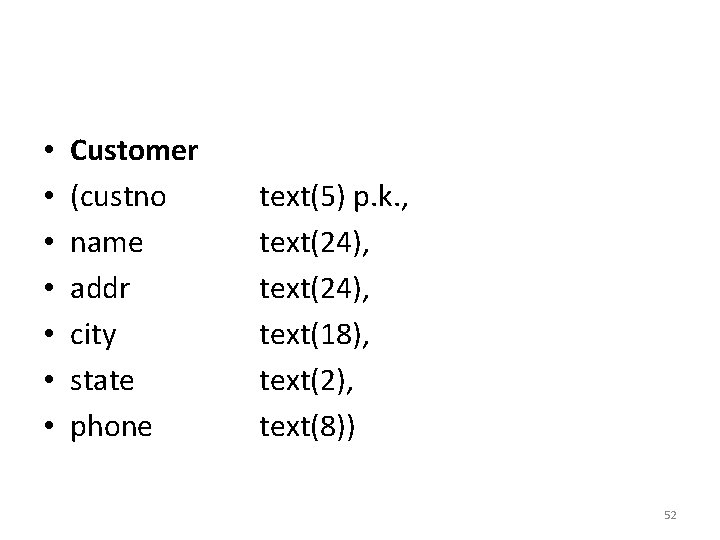

• • Customer (custno name addr city state phone text(5) p. k. , text(24), text(18), text(2), text(8)) 52

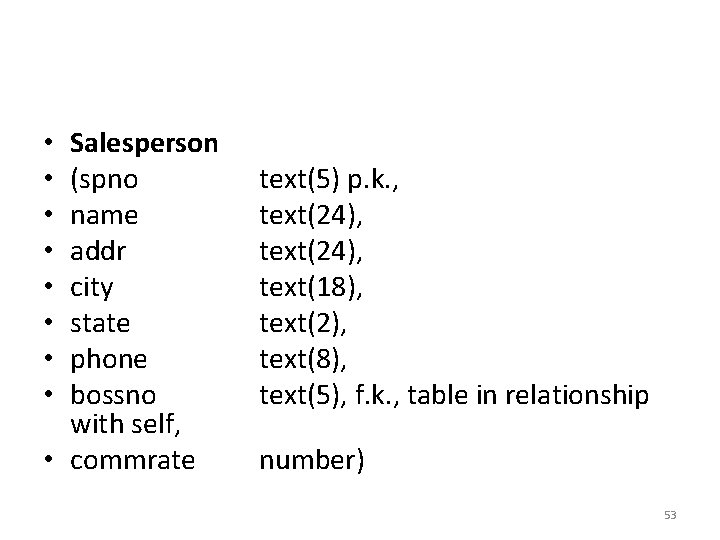

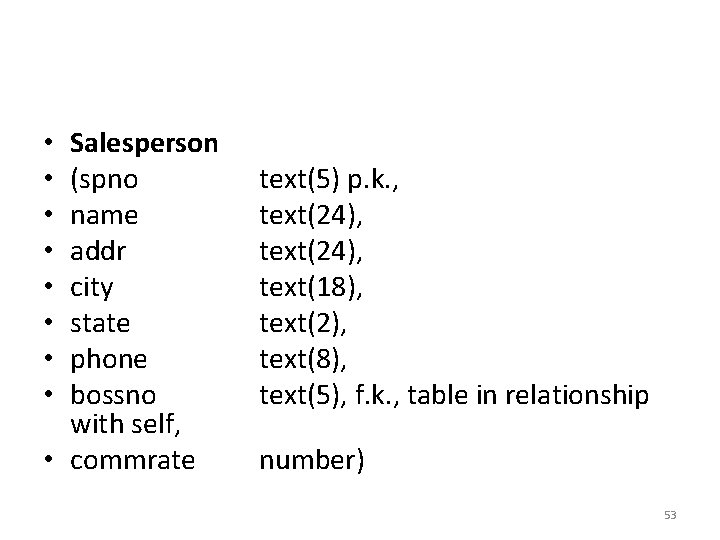

Salesperson (spno name addr city state phone bossno with self, • commrate • • text(5) p. k. , text(24), text(18), text(2), text(8), text(5), f. k. , table in relationship number) 53

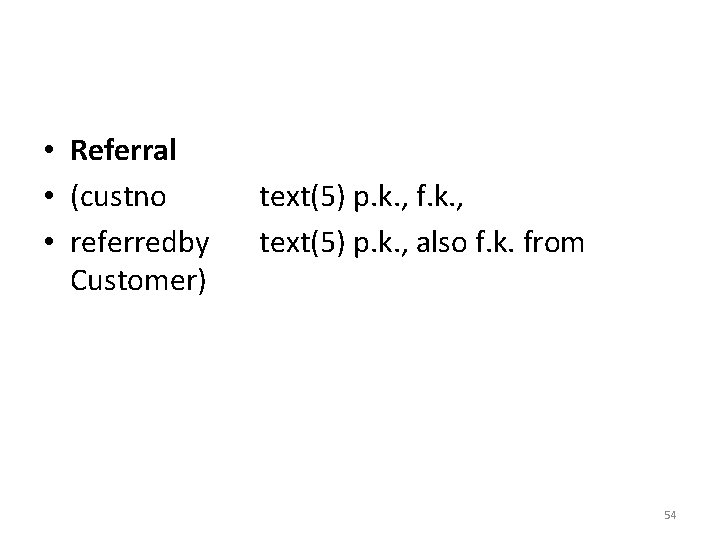

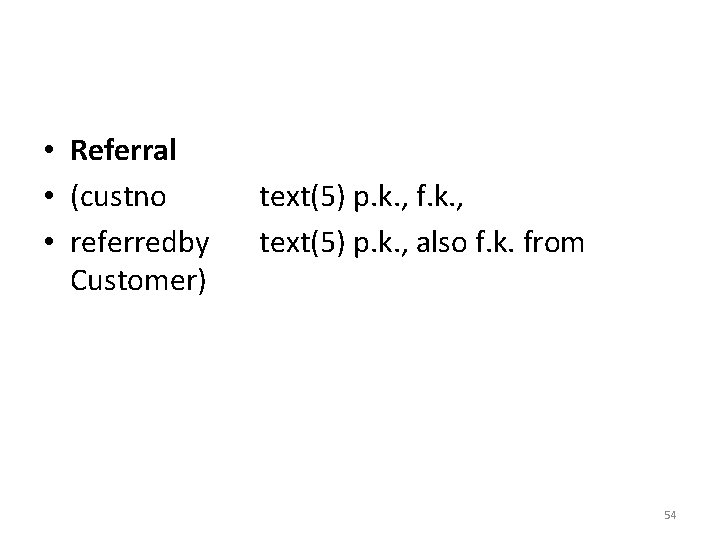

• Referral • (custno • referredby Customer) text(5) p. k. , f. k. , text(5) p. k. , also f. k. from 54

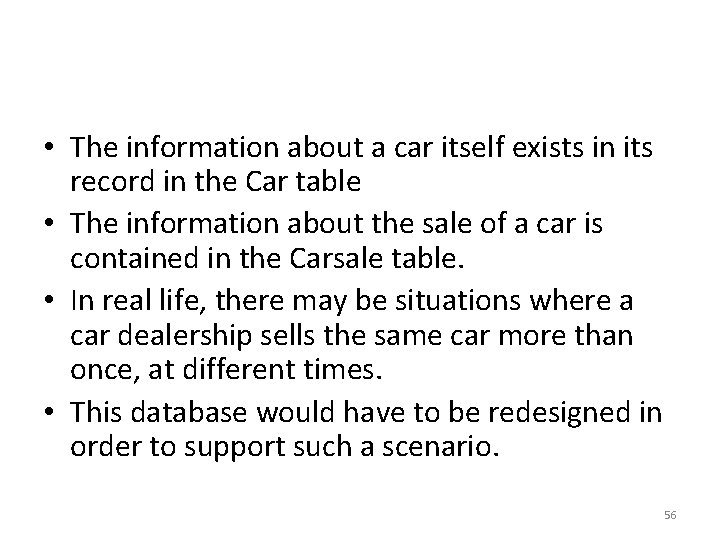

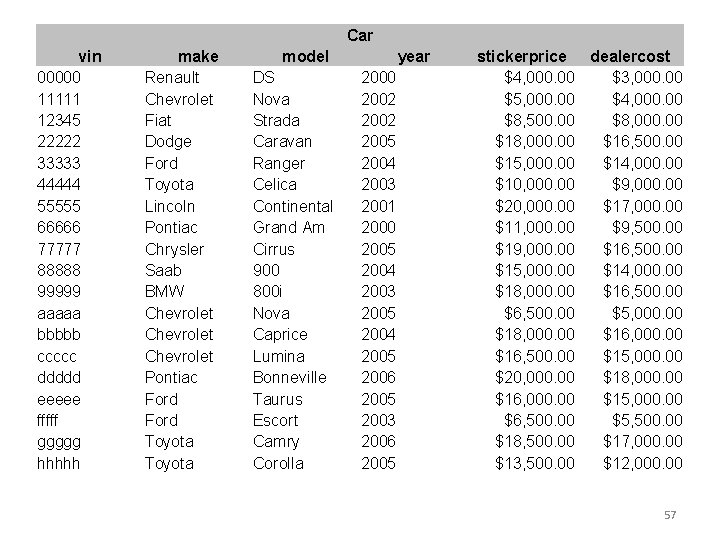

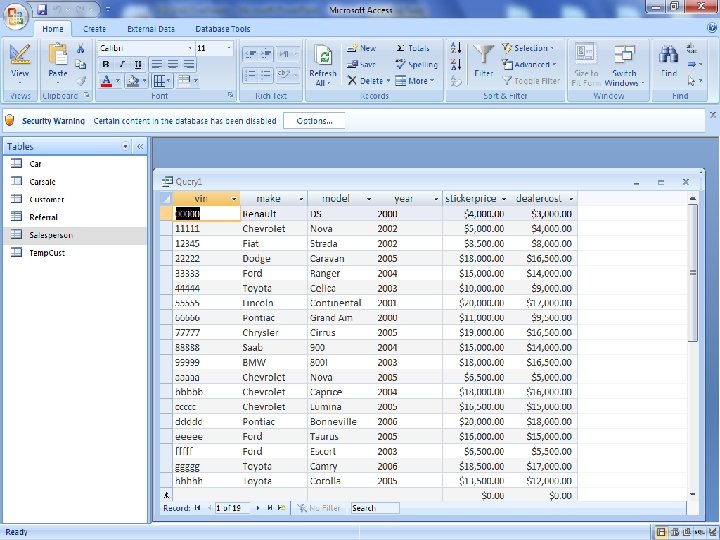

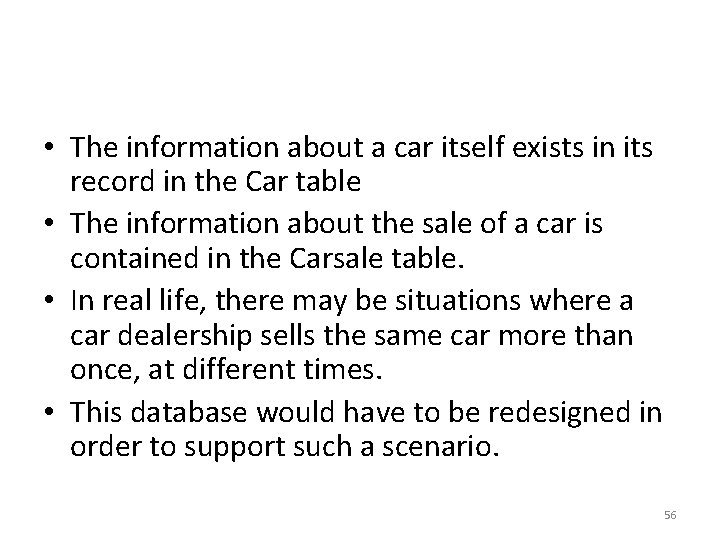

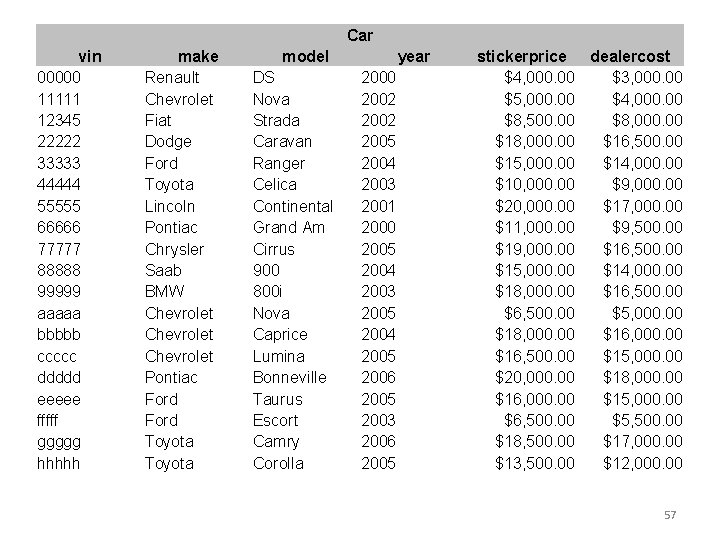

2. 1. 3 Contents • These are the contents of the car dealership database. • The vin is the primary key of both the Car and Carsale tables. • It is also a foreign key in the Carsale table. • The Car table is the fundamental table containing information about cars. • The vin can be the primary key of the Carsale table because the assumption is that cars can only be sold one time. 55

• The information about a car itself exists in its record in the Car table • The information about the sale of a car is contained in the Carsale table. • In real life, there may be situations where a car dealership sells the same car more than once, at different times. • This database would have to be redesigned in order to support such a scenario. 56

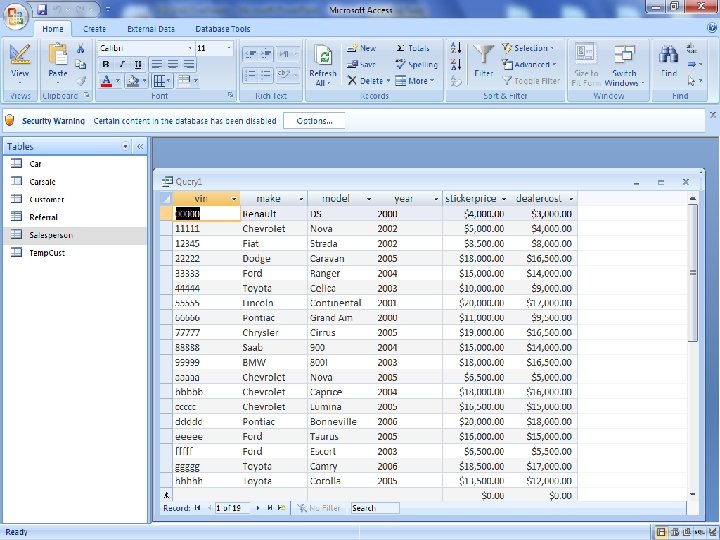

Car vin 00000 11111 12345 22222 33333 44444 55555 66666 77777 88888 99999 aaaaa bbbbb ccccc ddddd eeeee fffff ggggg hhhhh make Renault Chevrolet Fiat Dodge Ford Toyota Lincoln Pontiac Chrysler Saab BMW Chevrolet Pontiac Ford Toyota model DS Nova Strada Caravan Ranger Celica Continental Grand Am Cirrus 900 800 i Nova Caprice Lumina Bonneville Taurus Escort Camry Corolla year 2000 2002 2005 2004 2003 2001 2000 2005 2004 2003 2005 2004 2005 2006 2005 2003 2006 2005 stickerprice dealercost $4, 000. 00 $3, 000. 00 $5, 000. 00 $4, 000. 00 $8, 500. 00 $8, 000. 00 $16, 500. 00 $15, 000. 00 $14, 000. 00 $10, 000. 00 $9, 000. 00 $20, 000. 00 $17, 000. 00 $11, 000. 00 $9, 500. 00 $19, 000. 00 $16, 500. 00 $15, 000. 00 $14, 000. 00 $18, 000. 00 $16, 500. 00 $5, 000. 00 $18, 000. 00 $16, 500. 00 $15, 000. 00 $20, 000. 00 $18, 000. 00 $16, 000. 00 $15, 000. 00 $6, 500. 00 $5, 500. 00 $18, 500. 00 $17, 000. 00 $13, 500. 00 $12, 000. 00 57

Carsale vin spno custno salesdate salesprice 11111 2 9/9/2005 $4, 500. 00 12345 333 6 9/29/2005 $7, 500. 00 22222 1 9/15/2005 $18, 000. 00 44444 111 5 10/1/2005 $9, 250. 00 55555 222 4 8/31/2006 $18, 000. 00 88888 222 5 10/1/2006 $15, 000. 00 99999 333 3 9/29/2006 $16, 500. 00 ggggg 444 3 11/10/2006 $18, 000. 00 58

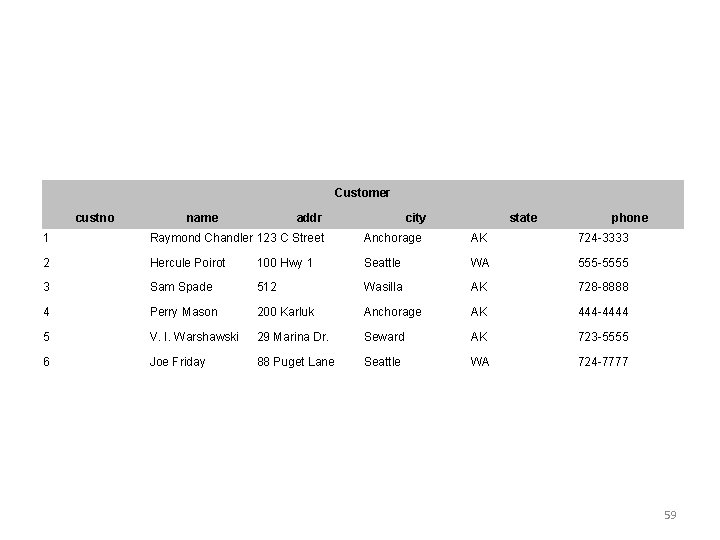

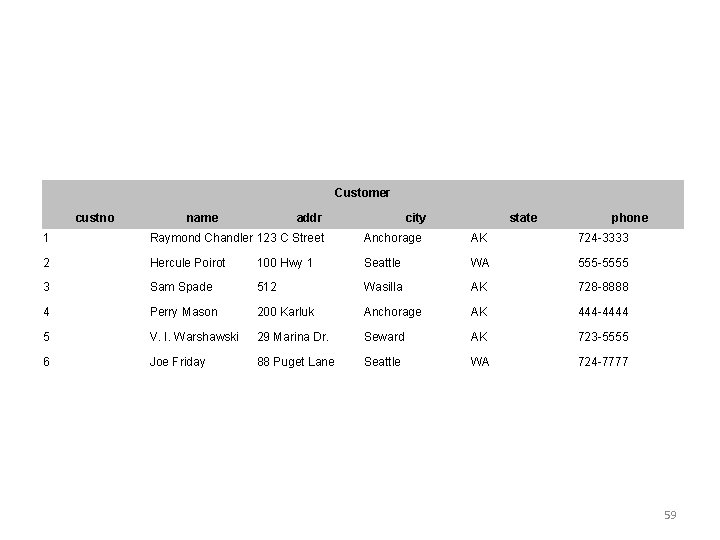

Customer custno name addr city state phone 1 Raymond Chandler 123 C Street Anchorage AK 724 -3333 2 Hercule Poirot 100 Hwy 1 Seattle WA 555 -5555 3 Sam Spade 512 Wasilla AK 728 -8888 4 Perry Mason 200 Karluk Anchorage AK 444 -4444 5 V. I. Warshawski 29 Marina Dr. Seward AK 723 -5555 6 Joe Friday 88 Puget Lane Seattle WA 724 -7777 59

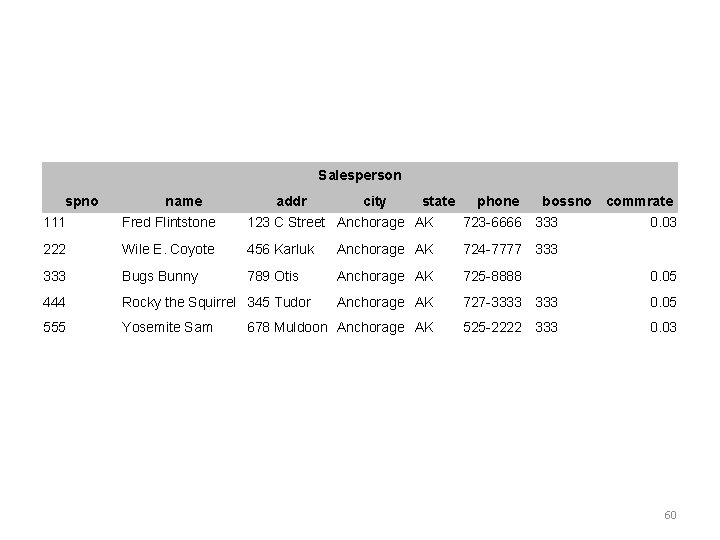

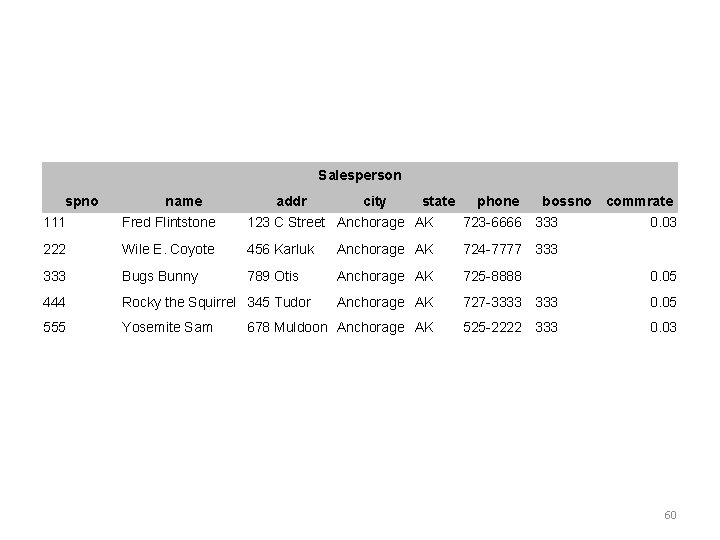

Salesperson spno name addr city state phone bossno commrate 111 Fred Flintstone 123 C Street Anchorage AK 723 -6666 333 0. 03 222 Wile E. Coyote 456 Karluk Anchorage AK 724 -7777 333 Bugs Bunny 789 Otis Anchorage AK 725 -8888 0. 05 444 Rocky the Squirrel 345 Tudor Anchorage AK 727 -3333 0. 05 555 Yosemite Sam 678 Muldoon Anchorage AK 525 -2222 333 0. 03 60

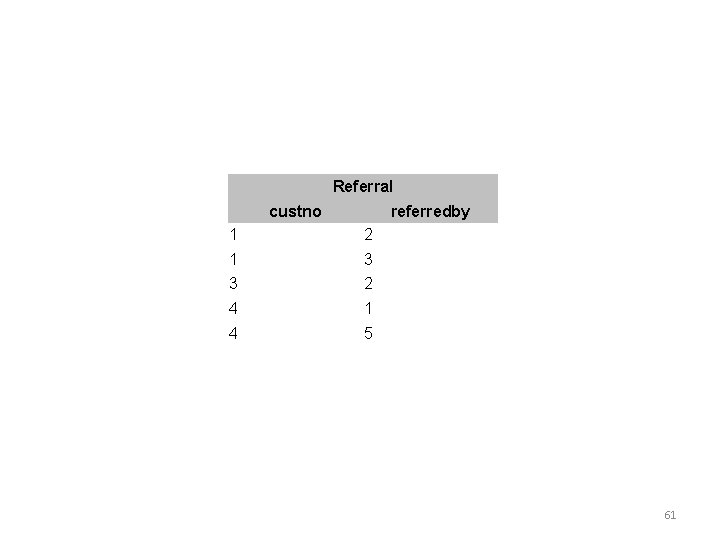

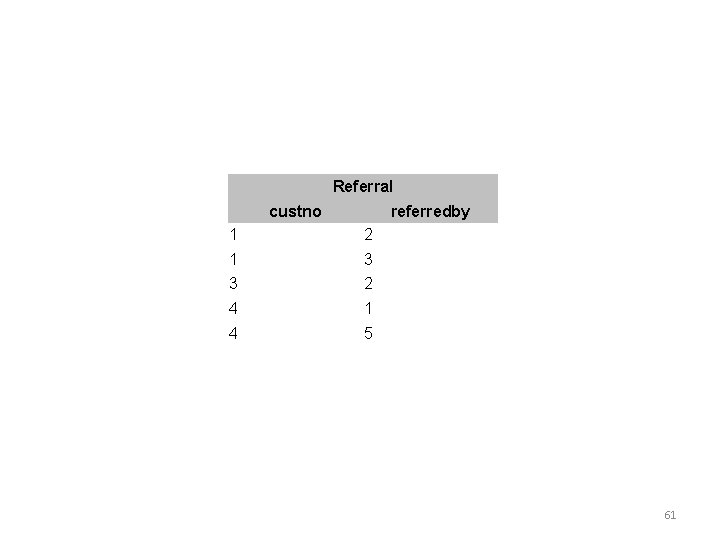

Referral custno referredby 1 2 1 3 3 2 4 1 4 5 61

2. 2 The Keywords SELECT and FROM; Queries with Projection 62

What is SQL? • SQL stands for structured query language. • A query extracts information of interest from a table or tables in a database. • SQL is a non-procedural language. • It does not contain ifs, loops, etc. • This is what makes it different from other computer languages 63

2. 2. 2 A Query Specifies Rows and Columns of Interest • An SQL query written by a user statically identifies rows and columns of interest in a table. • It does not specify how to retrieve these rows and columns. • The database management system translates the static query into procedural code internally, and retrieves and displays the information specified by the query. 64

2. 2. 3 The Keywords SELECT, FROM, and * Make a Simple Query • The keywords SELECT and FROM are the most basic keywords of SQL. • Note that from here on out, keywords will be given in all capital letters. • Table names will have their first letter capitalized. 65

• Field names will not be capitalized. • SQL is not case-sensitive, so any mixture of capital and non-capital letters could be used. • However, the examples are easier to read using these conventions. 66

* Stands for All Columns • The * is also used in SQL. • It is a wildcard, and it can be used to stand for the names of all of the fields in a table. • Here is a query which would retrieve all of the contents of the Car table. 67

Example • Without any additional conditions in the query, it will retrieve all rows, and the use of the * indicates that all columns for all rows should be retrieved: • • SELECT * • FROM Car 68

2. 2. 4 Formally, SQL Queries End with Semicolons • Formally, SQL queries are terminated by semicolons. • A single query only consists of one statement, so there would simply be a single semicolon at the end. • Many systems, including Microsoft Access SQL, will automatically provide a semicolon at the end of a query which doesn't have one, so in practice, writing the semicolon is optional. • The examples in these notes will be shown without semicolons. 69

2. 2. 5 Query Results Are Tabular in Form • The results of queries are always tabular in form. • Results may be as small as a single value, which would be regarded as one row and one column • Results can range up to complete tables, as in the example query given above. 70

Query Results May Contain Non. Unique Rows • Depending on the query, not all rows of the results may be unique. • As you will see later, duplicate rows can be eliminated from query results. • Results may be in no particular order, or you may observe cases where results seem to be in order according to the value of some field. • As you will see later, if a particular order is desired, it can be specified. 71

Query Results Are Temporary • Although results are tabular in form, the results are temporary. • They are displayed on the screen and not saved. • This is one reason why query results are allowed to have duplicate rows. • Syntax will also be introduced later on to save the results of queries as new tables. • If query results are saved as tables, then it becomes advisable to eliminate the duplicate rows from them. 72

• What is described here are known as ad hoc queries. • Someone has a particular question that they would like answered; • they write a query to find the answer; • they then move on. 73

• In advanced settings it is also possible to do things like embed queries in transaction processing programs, but that is beyond the scope of these notes. 74

2. 2. 6 Projection Specifies Columns to Include in Query Results • Projection is the technical term for picking only certain columns to show in the results of a query. • The syntax for projection is straightforward. • The SELECT statement should be followed by a list of the names of the fields desired from the table. 75

Example • Here is a simple example where only one field is specified: • • SELECT make • FROM Car 76

This Is an Example That Can Produce Non-Unique Rows • It should be noted that there are makes where there is more than one car of that make. • Each make will appear in the results the same number of times it actually appears in the Car table. 77

• More than one field can be specified in the SELECT statement. • The list of field names in the query does not have to be in the order that the fields appear in the table. • The order of the names in the query determines the order in which those columns would appear in the results. 78

Example • For example, you could do this: • • SELECT make, model • FROM Car 79

Example • You could also do this: • • SELECT model, make • FROM Car 80

2. 3 The Keywords WHERE, AND, OR, NOT, and NULL; Queries with Selection 81

2. 3. 1 Selection Specifies Rows to Include in Query Results • It is also possible to write queries which specify that only certain rows should be selected from a table and shown in the results. • Picking rows is technically known as selection. 82

• Some authors don't care for this terminology because of the possibility for confusion with the keyword SELECT. • They refer to this as restriction, for example, or use some other term. • Selection is accomplished by stating that you are interested in rows where given fields take on values that you specify in the query. 83

2. 3. 2 The Keyword WHERE with Fields and Values—Example • Selection queries are written by using the keyword WHERE. • Here is a simple example of its use: • • SELECT * • FROM Car • WHERE make = 'Chevrolet' 84

• WHERE and the = sign are used to specify the value of interest in the make field, 'Chevrolet'. • Since make is a text field, it's necessary to enclose the value in quotes. • The effect of the WHERE clause in the query is to cause only those records to be retrieved for cars which have Chevrolet as their make. • As before, the * specifies that all fields of those records should be shown in the results. 85

• If the WHERE clause does a comparison based on a numeric field, then the value specified should not be in quotes. • Recall that monetary fields are numeric in nature. • In output they are formatted with currency symbols and commas, but when values are specified, only digits and a single decimal point are allowed. 86

Example • Here is an example query with a numeric value in it: • • SELECT * • FROM Car • WHERE dealercost = 10000 87

A Select-Project Example • It is a simple matter to combine selection and projection. • Here is another example query: • • SELECT make, model • FROM Car • WHERE make = 'Chevrolet' 88

• The way the query works can be illustrated with a plaid pattern. • The SELECT picks columns of interest. • The WHERE picks rows of interest. • The values where these cross are the values that will be shown in the results. 89

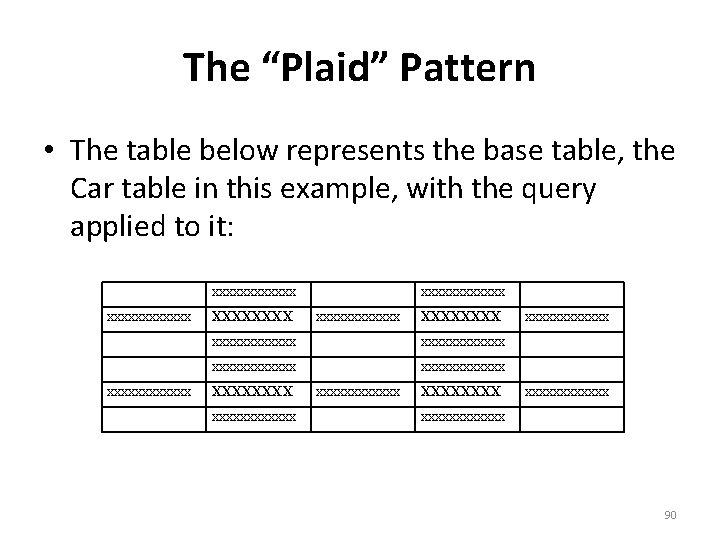

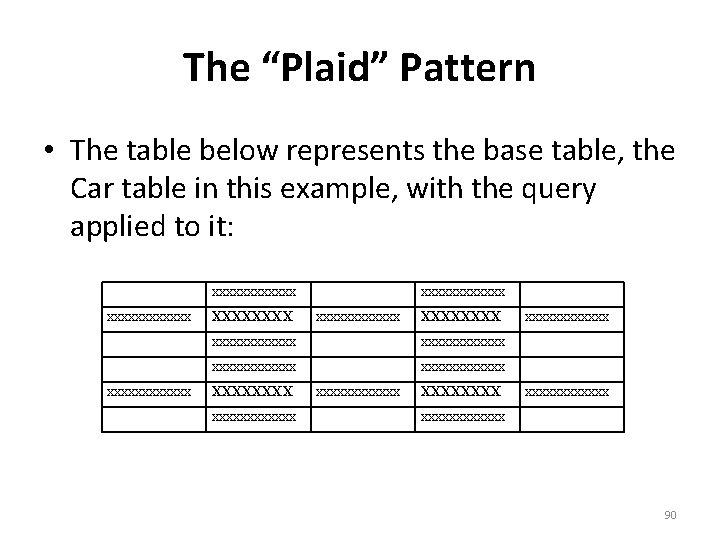

The “Plaid” Pattern • The table below represents the base table, the Car table in this example, with the query applied to it: xxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxx XXXXXXXX xxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxx 90

• The results of the query are represented by the following table: XXXXXXXX 91

2. 3. 3 SQL is Not Case Sensitive • It was mentioned earlier that SQL was not case sensitive. • When writing a query, it doesn't matter whether keywords, table names, or field names include capital letters or not. • SQL is also not case sensitive when it comes to field values. 92

• When you enter a value like 'Chevrolet' into a table, the system faithfully records the capitalization that you used. • It also faithfully reproduces that capitalization when the data is retrieved. • However, the following queries, for example, accomplish exactly the same thing as the previous example: 93

Examples • • SELECT make, model FROM Car WHERE make = 'CHEVROLET' SELECT make, model FROM Car WHERE make = 'Ch. Ev. Ro. Le. T' 94

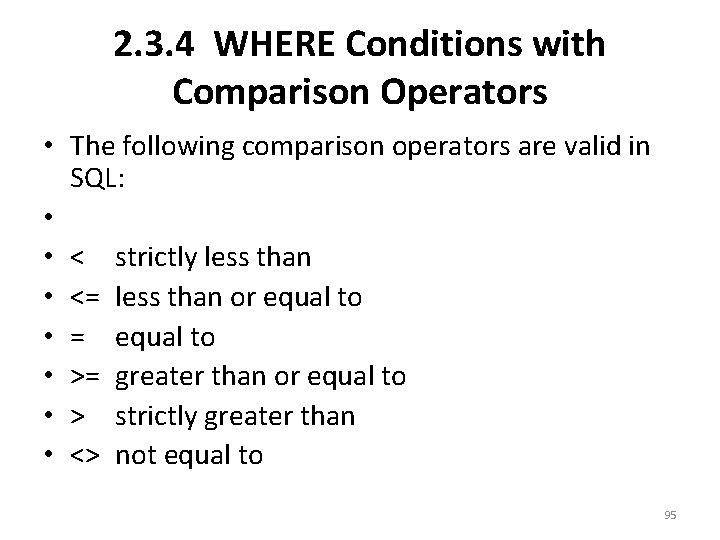

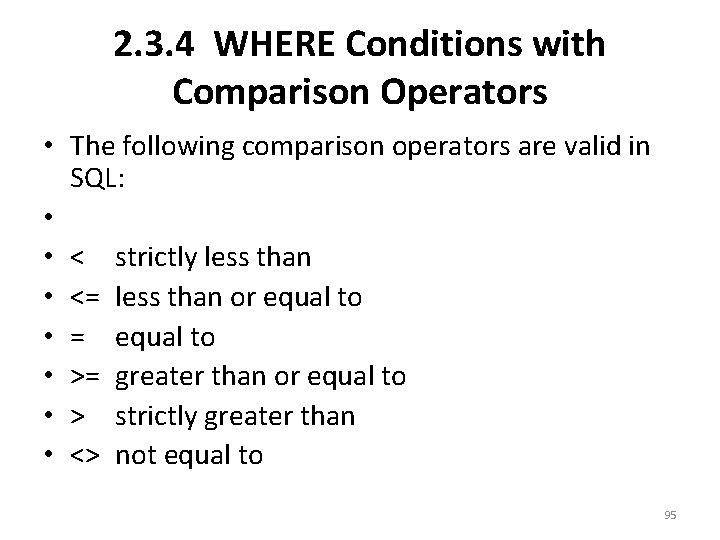

2. 3. 4 WHERE Conditions with Comparison Operators • The following comparison operators are valid in SQL: • • < strictly less than • <= less than or equal to • = equal to • >= greater than or equal to • > strictly greater than • <> not equal to 95

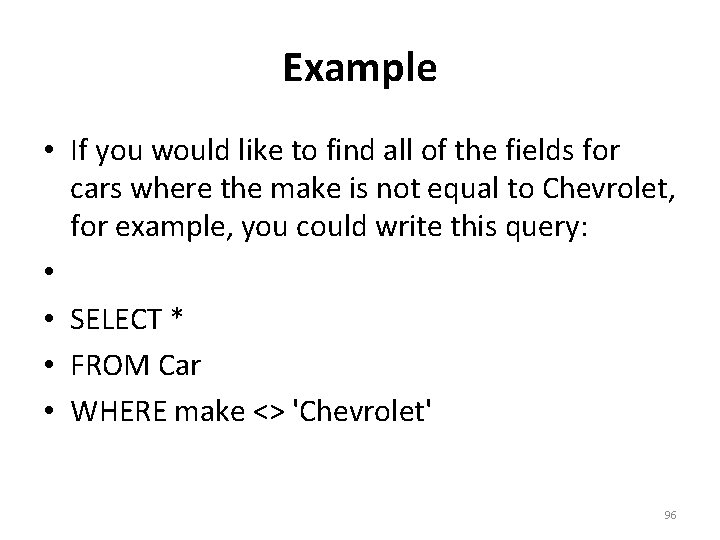

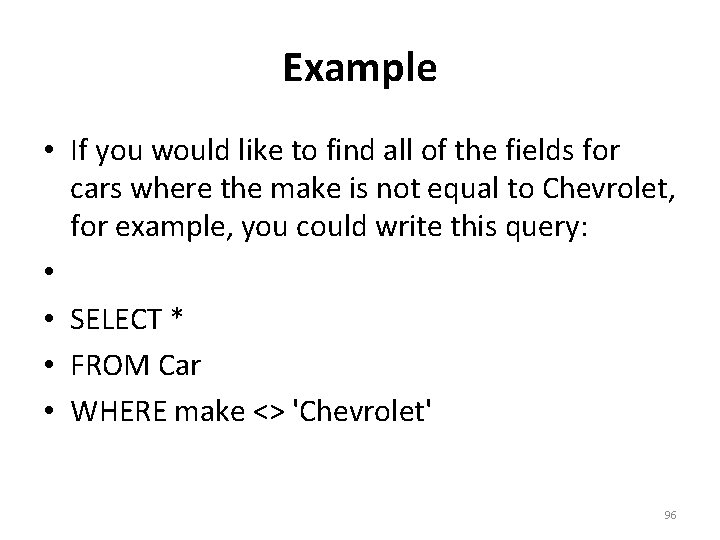

Example • If you would like to find all of the fields for cars where the make is not equal to Chevrolet, for example, you could write this query: • • SELECT * • FROM Car • WHERE make <> 'Chevrolet' 96

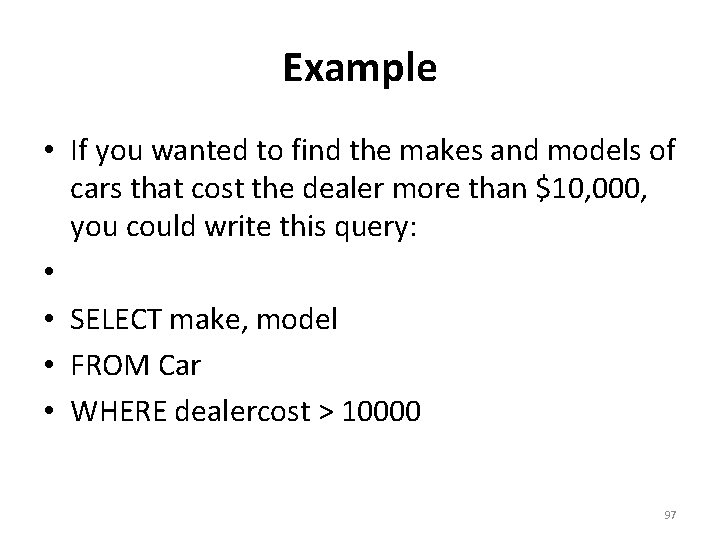

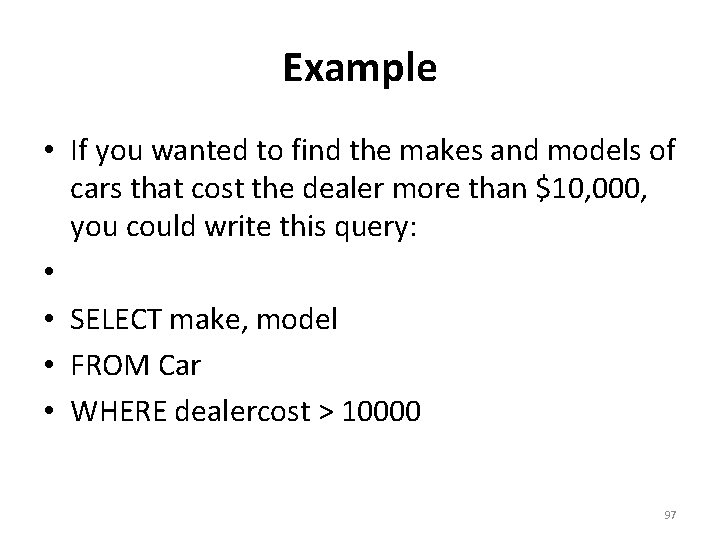

Example • If you wanted to find the makes and models of cars that cost the dealer more than $10, 000, you could write this query: • • SELECT make, model • FROM Car • WHERE dealercost > 10000 97

2. 3. 5 The Logical Operators AND and OR • Compound WHERE conditions can be formed using the logical operators AND and OR. • These are binary operators. • Simple examples of their use are given below along with brief verbal explanations of what they mean: 98

Logical Conditions • (make = 'Chevrolet') AND (year = '2005') • The logical operator AND means that both conditions have to hold true at the same time. • In a query, this compound condition would mean that you only wanted to see records for 2005 Chevrolets. 99

• (dealercost > 10000) AND (dealercost < 15000) • In a query, this would mean that you were interested in records where the value of the dealercost was between 10000 and 15000. 100

• (make = 'Chevrolet') OR (year = '2005') • In a query, this would signify that you were interested in records where the make field contained the value Chevrolet or the year field contained the value 2005. • It is important to note that records where both of these conditions held true would also qualify. • In other words, OR means one or the other or both conditions hold true. 101

• (dealercost > 10000) OR (dealercost < 15000) • This example illustrates how it is possible to devise conditions that have no effect. • All numeric values are either greater than 10000 or less than 15000. 102

2. 3. 6 The Logical Operator NOT and Complex Conditions • The logical operator NOT makes it possible to negate conditions. • If the conditions are simple enough, there are usually alternatives to using NOT. • For example, these two conditions are equivalent: • • (make = 'Chevrolet') AND NOT (year = '2005') • (make = 'Chevrolet') AND (year <> '2005') 103

• Using AND, OR, and NOT, it is also possible to make arbitrarily complex conditions. • You might have noticed, for example, that logical OR is what is known as an inclusive OR. • If either one, or the other, or both conditions connected by OR hold true, then the overall expression is true. 104

• An alternative kind of "or", known as exclusive or, holds true if one or the other, but not both conditions hold true. • This is abbreviated XOR. • It is possible to devise a logical expression that has this meaning. 105

How to Construct XOR • Let p and q represent individual conditions. • Then this expression defines exclusive OR: • • p OR q AND NOT (p AND q) 106

• For example, if you wanted to find Chevrolets and cars from 2005, but wanted to exclude 2005 Chevrolets from the results, you could write the following: • • (make = 'Chevrolet') OR (year = '2005') AND NOT ((make = 'Chevrolet') AND (year = '2005')) 107

Operators Added to SQL • Incidentally, recent versions of Access SQL support the operator XOR • Recent versions also support the operator EQV, which can be defined in this way: • (p AND q) OR (NOT p AND NOT q) 108

2. 3. 7 Queries with NULL and IS • Just as it can be useful to write queries that check for the presence of certain values, it can be useful to write queries that check for the absence of values in fields. • For example, not all salespeople have commrates recorded for them. • Keep in mind that the keyword NULL signifies a field that contains no value at all. 109

Use the Keyword IS with NULL • NULL does not signify a field that contains blank spaces. • NULL is not a value and should not be enclosed in quotes ('NULL'). • Likewise, when testing to see whether a field is NULL, you don't do a comparison with the = sign. • Instead, you use the keyword IS. 110

IS NULL Example • The following query will find the salespeople without commrates: • • SELECT * • FROM Salesperson • WHERE commrate IS NULL 111

Example with IS NOT NULL • NOT can also be used with NULL. • Some salespeople do not have a boss (bossno) recorded for them. • If you wanted to find all of the salespeople who did have a boss, you could write this query: • • SELECT * • FROM Salesperson • WHERE bossno IS NOT NULL 112

2. 4 The Keyword LIKE 113

• Of all of the things that can be done with text fields, the most useful is probably writing queries using the keyword LIKE. • It is possible to specify a special kind of string and use this in place of a concrete value in a WHERE clause. 114

Wildcards with LIKE • The special string can include these symbols: – * The asterisk stands for any valid sequence of characters. – ? The question mark stands for any one valid character, letter or digit. – # The number sign stands for any one valid digit. 115

Example with LIKE • If you wanted to find all of the models of cars that started with the letter 'C', you could write this query: • • SELECT model • FROM Car • WHERE model LIKE 'C*' 116

• I had a student once who happened to have a Polish last name. • She told me that she had received junk mail from her bank, encouraging her to apply for the "Polish Heritage Credit Card". 117

• • • Could this be how they identified her? SELECT name, addr, city FROM Customer WHERE name LIKE '*ski' 118

• Here is an example of the use of the ? . • This would select only those cars which had years falling in the first decade of the 21 st century: • • SELECT vin, make, model, year • FROM Car • WHERE year LIKE '200? ' 119

• If the field contained mistaken values like 200 A, the previous query would retrieve them. • The following query would not: • • SELECT vin, make, model, year • FROM Car • WHERE year LIKE '200#' 120

• There are techniques for creating highly detailed patterns to match on. • They may be of interest to advanced users, but the same thing can be accomplished by combining separate conditions with AND and OR. 121

2. 5 The Keywords ORDER BY, ASC, and DESC; Ordering the Results of Queries 122

2. 5. 1 The Keywords ORDER BY and Default Ordering on a Single Field • The keywords ORDER BY can be used to specify a field that you'd like query results ordered by. • The default ordering is ascending by value in that field. • Here is an example: • • SELECT * • FROM Car • ORDER BY year 123

NULL is the “Smallest” Value of All • It is worth remembering that when ordering, the value NULL is considered less than any other value. • If there were any records in the Car table with the year field NULL, those records would be displayed before any other records in the results. 124

2. 5. 2 The Keywords ASC and DESC for Specifying Ascending and Descending Order • It is also possible to specify ascending or descending order with the keywords ASC and DESC, respectively. • If you didn't want to rely on the default, you could write a query like this: • • SELECT * • FROM Car • ORDER BY year ASC 125

Example • If you wanted the rows of the result to be arranged according to the year from the highest to lowest, then you could write this: • • SELECT * • FROM Car • ORDER BY year DESC 126

2. 5. 3 Ordering by More Than One Field • When ordering by more than one field, it's important which field comes first and which comes second. • The classic example of this is ordering by city and state. Typically what you want is for the results to be ordered by state, and within state by city. 127

Example—by City, within State • • • Here is an example: SELECT spno, name, city, state FROM Salesperson ORDER BY state, city 128

• In the SELECT, city comes before state, and in the results, the city column will come before the state column. • However, in the ORDER BY, the state comes first and the city comes second. • The results will be ordered first by states in ascending order, and for each state the results will be ordered by city in ascending order. 129

Example • Just to illustrate the various possibilities, here is another example: • • SELECT spno, name, city, state • FROM Salesperson • ORDER BY state DESC, name 130

2. 6 The Keyword DISTINCT 131

DISTINCT Removes Duplicates • Although formally a table is not allowed to have duplicate records, this restriction doesn't apply to query results. • The keyword DISTINCT in a query has the effect of removing duplicates. 132

Example • Here is a simple illustration of its use: • • SELECT DISTINCT year • FROM Car 133

Parentheses Are Not Needed with DISTINCT • If multiple fields are selected in a query, the keyword DISTINCT applies to whole rows at a time of the results. • It is not necessary to use parentheses to enclose the list of fields, and it is not necessary to use the keyword DISTINCT with each field name. 134

Example—DISTINCT Applies to make and model Together as the Result Row • For example: • • SELECT DISTINCT make, model • FROM Car 135

NULL is a Valid DISTINCT Value • The keyword DISTINCT doesn't remove nulls. • In the first example, if at least one of the cars had a null year, the first row of the results of this query would be blank. • In the second example, if there were a case where both the make and model were null, the first record in the results would be all null. 136

DISTINCT Is Typically Implemented by Sorting— But Don’t Rely on This for Sorting • When running queries with the keyword DISTINCT, you may observe that the results come up in sorted order by the selected fields. • This is a side effect of the algorithm used to find and eliminate duplicates. 137

• This is the approach: • Sort on the field(s) of interest; • this will put the duplicates next to each other where they're easy to detect and then eliminate. 138

• Informally, the algorithm can be said to "squeeze out" the duplicates. • It is possible to use ORDER BY in a query with DISTINCT to specify whatever order might be desired in the results. 139

2. 7 The Keyword COUNT; Counting the Number of Rows in a Result 140

2. 7. 1 Counting All Records in a Table —COUNT Is a Function() • The keyword COUNT is really a function, a topic that will be covered in more detail later. • You know it's a function because it is always followed by a pair of parentheses: COUNT(). • COUNT counts the number of occurrences of values which are not null. 141

Initial Example • You know what this query means: • • SELECT * • FROM Salesperson 142

Example—Count All Rows in the Result • The corresponding COUNT query would look like this: • • SELECT COUNT(*) • FROM Salesperson 143

COUNT Does Not Count NULLs (Not an Issue in this Example) • The * still represents all of the fields in the table. • This query includes in the count all records where the set of all fields for the record is not null. • At the very least, the primary key field of every record is non-null, so there is no record where all of the fields are null. 144

The Result of COUNT is a Single Number— Regarded as a One-Row, One-Column Result Table • This means that this query will count all of the records in a table. • Notice that the result of the query is a single number. • This result is regarded as a table consisting of one row and one column. 145

2. 7. 2 Counting Records Based on Specific Field Values in a Table • You can use the COUNT function to count on specific fields. • As noted earlier, some of the records in the Salesperson table have null fields. • If you did a count on those fields, you would get a result different from the previous query. 146

Example—commrate is NULL for some Salespeople—Which Will Affect the Count • For example: • • SELECT COUNT(commrate) • FROM Salesperson 147

2. 7. 3 You Can't Use COUNT with DISTINCT • It is not possible to use COUNT and DISTINCT together in (at least some versions of) Microsoft Access. • Based on the information given so far, the intent of the query shown below should be clear. • Unfortunately, this syntax isn't supported. • Other techniques for achieving the desired results will be given later: • • SELECT COUNT(DISTINCT year) • FROM Car 148

2. 8 The Keyword AS; Aliases 149

2. 8. 1 Column Aliases • The term column alias refers to the idea that you can include in a query alternative headings for columns in the results. • Consider this query: • • SELECT name • FROM Salesperson 150

• The column heading will be the name of the selected field, name. • Suppose you'd like the column heading to consist of two words, salesperson name. • There are three ways of accomplishing this. • In all three cases, you can use the keyword AS. 151

Example: A Column Heading Different from the Field Name • The first option is to connect the two desired words with an underscore, for example: • • SELECT name AS salesperson_name • FROM Salesperson 152

Example—Another Way of Getting a Different Column Heading—Quotation Marks Show • If you want the column heading to be the two words without an underscore, you can enclose them in quotes. • The shortcoming of this approach is that the quotes will also be displayed as part of the column heading: • • SELECT name AS 'salesperson name' • FROM Salesperson 153

Example—The Most Flexible Way • The third, and best alternative is to enclose the desired alias in square brackets. • These serve like quotation marks, but they are not displayed in the output: • • SELECT name AS [salesperson name] • FROM Salesperson 154

The End 155