Specifying and Proving Object Oriented Programs Arthur C

Specifying and Proving Object. Oriented Programs Arthur C. Fleck Computer Science Department University of Iowa 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 1

A specification should allow for many implementations. An implementation may be based on a variety of data structures and algorithms. Nonetheless, a specification precisely describes the “essential behavior” of each implementation. 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 2

An object is a collection of functions that share a state. — Peter Wegner 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 3

An object is a collection of functions that share a state. — Peter Wegner BUT the function concept is a “stateless” idea — every time a function is called with the same arguments, it returns the same value. 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 4

The Abstract Data Type (ADT) methodology is a wellestablished means of describing a collection of functions and the domains on which they operate. The ADT methodology avoids all representation details of the functions and their domains, and expresses only the “essential properties”. 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 5

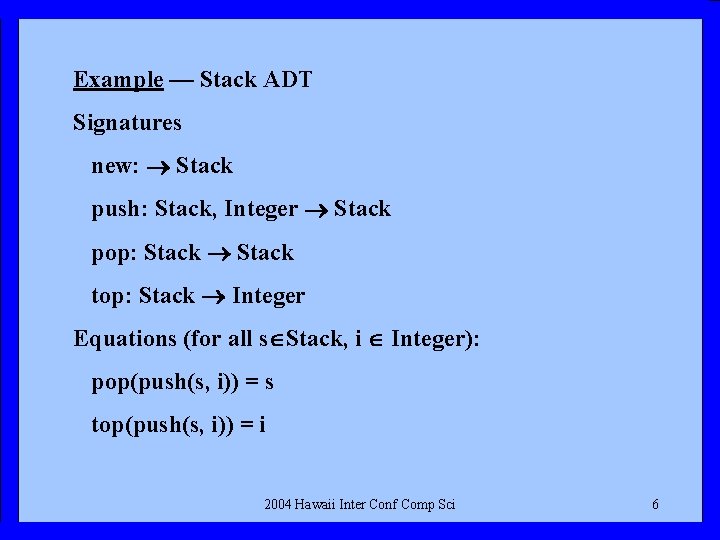

Example — Stack ADT Signatures new: Stack push: Stack, Integer Stack pop: Stack top: Stack Integer Equations (for all s Stack, i Integer): pop(push(s, i)) = s top(push(s, i)) = i 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 6

Notice that in the Stack ADT example, the domain of Stack values remains completely abstract — no implementation details are presumed. Also, no algorithms are provided for the operations, but their essential properties (LIFO) are effectively indicated. 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 7

This conventional ADT methodology is our starting point and we seek to formalize the incorporation of a shared state in this context. A primary goal is to retain the abstractness inherent in the ADT methodology so that the state component also avoids presuming any representation details. 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 8

To avoid all state representation details, we adopt a history perspective. That is, since an object has local memory, it may respond differently each time an identical message is sent. These behavioral differences are ascribed to the history of prior messages received by the object. 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 9

The methods of a class are characterized according to their dependence on local storage. The options are: state-independent — its results depend only on its arguments; state-dependent — a result may depend on the state of the receiving object. 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 10

Methods are also characterized according to their effect on local state. The options are: side-effect free — execution never changes the state, only a functional result is produced; side-effect inducing — execution may change the state as well as yielding a result. 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 11

The two characteristics we have just identified divide the methods of a class into up to four categories. An Abstract Object Class (AOC) incorporates a finite collection of abstract data domains including a state set, a finite collection of message identifiers together with their signatures and state related categories, and a finite collection of semantic equations. 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 12

From this perspective, an ADT is just an AOC each of whose operations is state-independent and sideeffect free. As already required for ADTs, we find it necessary to admit “hidden methods” in AOCs. We also allow methods to incorporate “hidden arguments” — this is the role played by an object’s states. 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 13

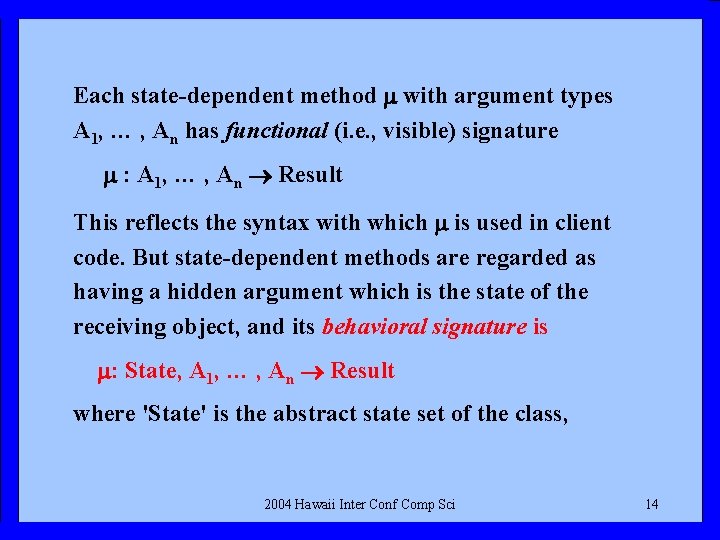

Each state-dependent method with argument types A 1, … , An has functional (i. e. , visible) signature : A 1, … , An Result This reflects the syntax with which is used in client code. But state-dependent methods are regarded as having a hidden argument which is the state of the receiving object, and its behavioral signature is : State, A 1, … , An Result where 'State' is the abstract state set of the class, 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 14

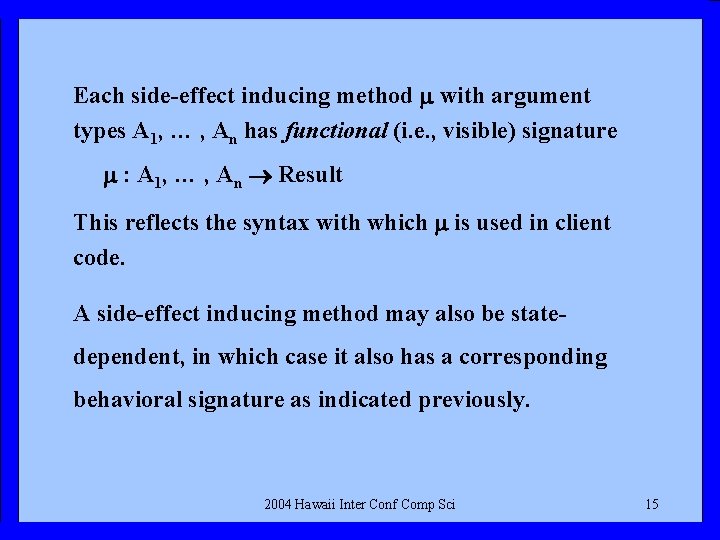

Each side-effect inducing method with argument types A 1, … , An has functional (i. e. , visible) signature : A 1, … , An Result This reflects the syntax with which is used in client code. A side-effect inducing method may also be statedependent, in which case it also has a corresponding behavioral signature as indicated previously. 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 15

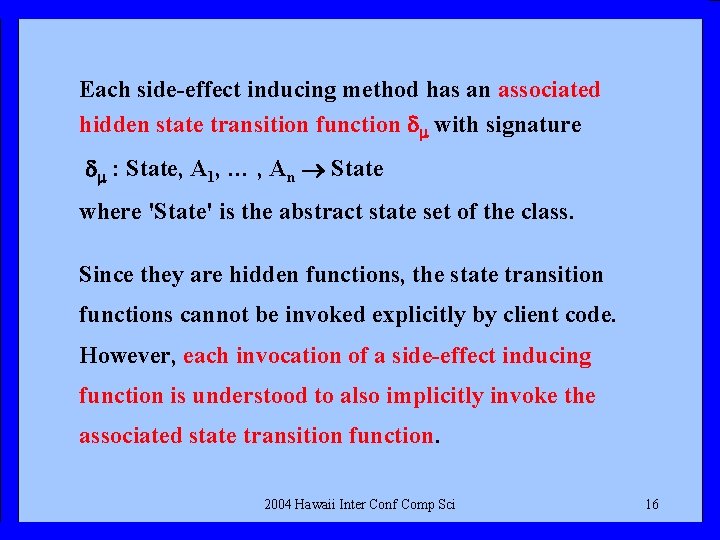

Each side-effect inducing method has an associated hidden state transition function with signature : State, A 1, … , An State where 'State' is the abstract state set of the class. Since they are hidden functions, the state transition functions cannot be invoked explicitly by client code. However, each invocation of a side-effect inducing function is understood to also implicitly invoke the associated state transition function. 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 16

With these conventions, we have identified a collection of functions, all with abstract domains, and including a shared abstract state set. We can now proceed to specify these functions using methodology similar to that for ADTs! 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 17

The abstract state of an object is expressed as the sequence of all messages received by the object. The history perspective is applied by specifying the behavior of sequences of messages rather than individual messages. 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 18

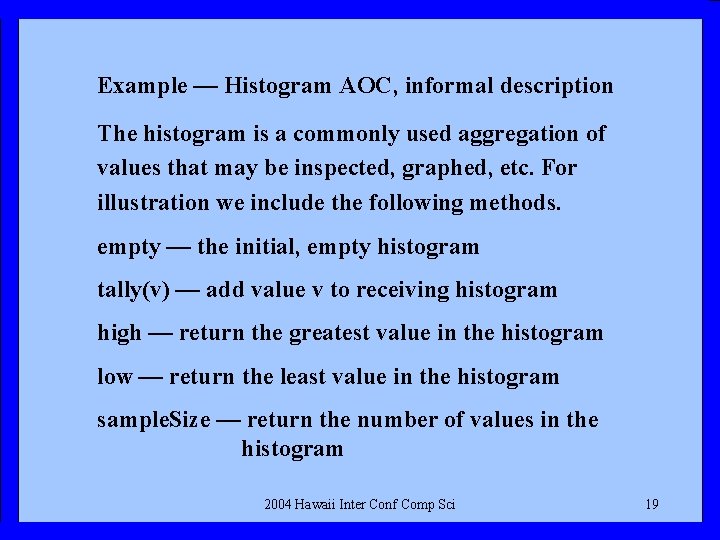

Example — Histogram AOC, informal description The histogram is a commonly used aggregation of values that may be inspected, graphed, etc. For illustration we include the following methods. empty — the initial, empty histogram tally(v) — add value v to receiving histogram high — return the greatest value in the histogram low — return the least value in the histogram sample. Size — return the number of values in the histogram 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 19

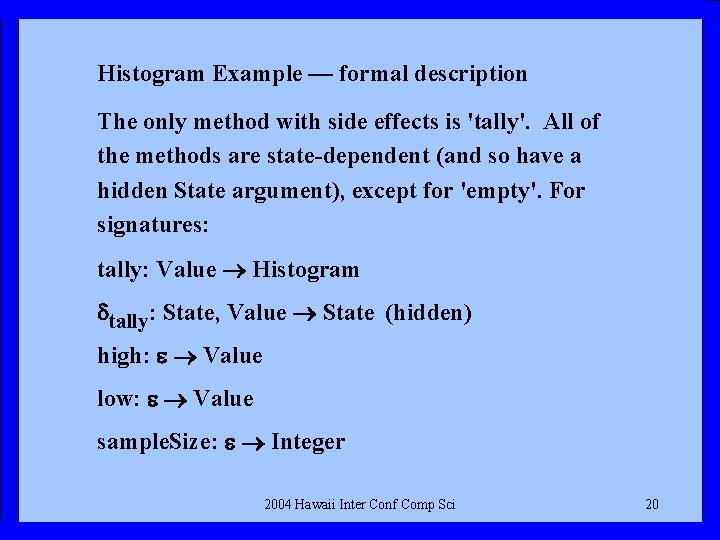

Histogram Example — formal description The only method with side effects is 'tally'. All of the methods are state-dependent (and so have a hidden State argument), except for 'empty'. For signatures: tally: Value Histogram tally: State, Value State (hidden) high: Value low: Value sample. Size: Integer 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 20

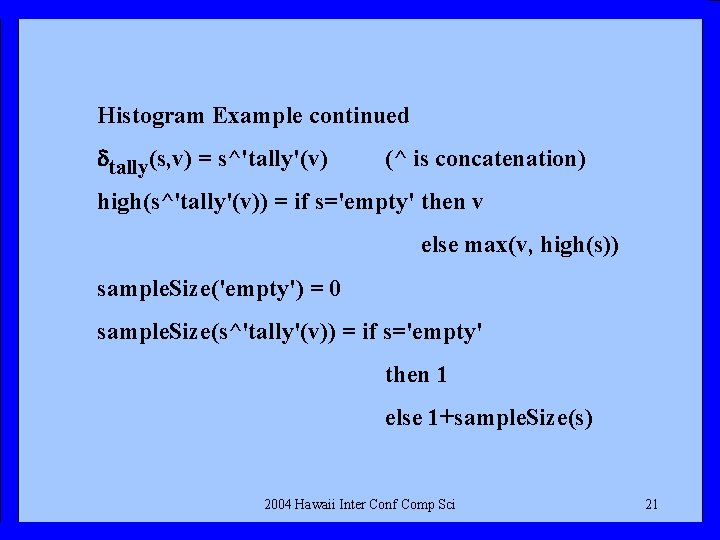

Histogram Example continued tally(s, v) = s^'tally'(v) (^ is concatenation) high(s^'tally'(v)) = if s='empty' then v else max(v, high(s)) sample. Size('empty') = 0 sample. Size(s^'tally'(v)) = if s='empty' then 1 else 1+sample. Size(s) 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 21

With this specification, the instance variable structure of an implementation is not dictated. Whether instance variables are used to hold e. g. high and low values or not remains the option of the implementor while the essential behavior is still clearly indicated. 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 22

Notice that the transition function definition for the tally method is especially simple — on the righthand side, the new invocation is just concatenated on the end. While they can be defined equationally, transition function definitions are so trivial that we would normally leave them implicit in the understanding of an abstract state as the sequence of all messages received by an object. 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 23

Since what remains is a collection of functions, conventional ADT-like methodology suffices to formalize their description. The extensions we require are hidden arguments, plus the coupling of each transition function invocation with the invocation of its side-effect inducing method. This accomplishes the formalization of Peter Wegner’s intuition of an object as a collection of functions that share a state. 2004 Hawaii Inter Conf Comp Sci 24

- Slides: 24