Specific features of Slavic space conceptualisation and interpretation

![Universiteit van Amsterdam IN-CATEGORIES (Podgaevskaja 2008): - [buildings with their functions] [compartments in buildings] Universiteit van Amsterdam IN-CATEGORIES (Podgaevskaja 2008): - [buildings with their functions] [compartments in buildings]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/04e117a9fb1bf0e74dadd914515f69a2/image-14.jpg)

![Universiteit van Amsterdam ON-CATEGORIES: - elevations of the earth’s surface, enclosed by water] (island, Universiteit van Amsterdam ON-CATEGORIES: - elevations of the earth’s surface, enclosed by water] (island,](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/04e117a9fb1bf0e74dadd914515f69a2/image-15.jpg)

- Slides: 24

Specific features of Slavic space: conceptualisation and interpretation Research project proposal Alla Peeters-Podgaevskaja Second Language Acquisition department, Department of Slavic Languages and Cultures, Uv. A May 15, 2009

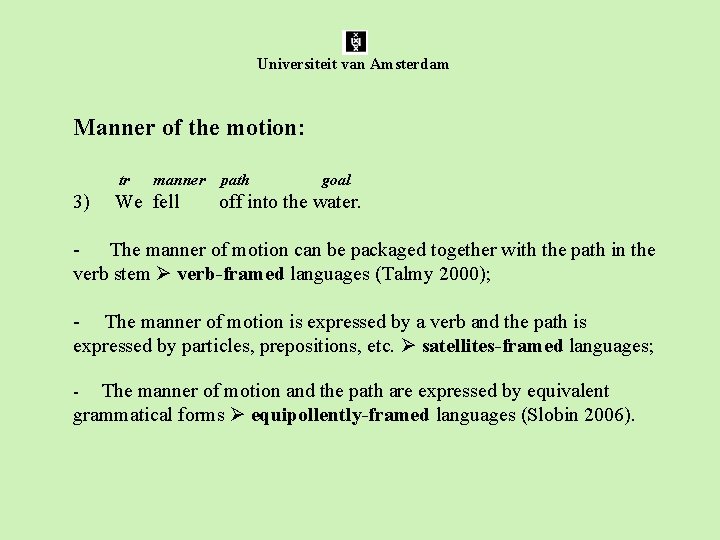

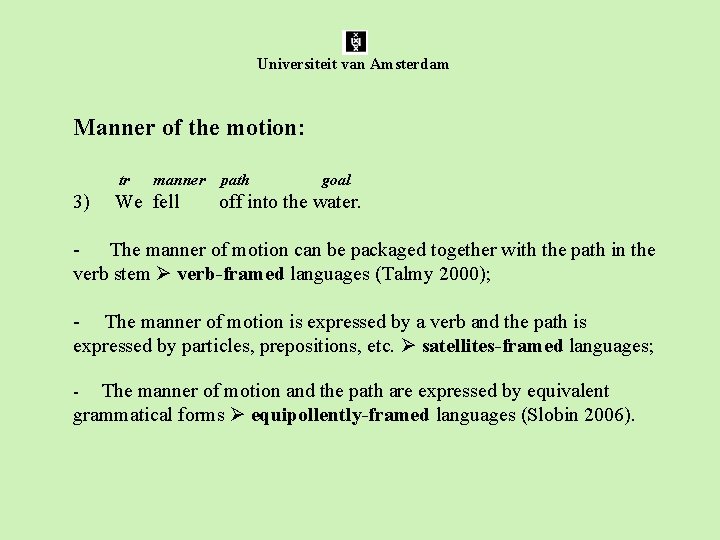

Universiteit van Amsterdam 1 In space we deal with - dynamic events, motions events (Motion domain); static scenes/situations (Topology/Geometry domain); an observer who orientates himself, objects and locations with respect to himself and to each other (Frame-of-reference domain). 2 - A spatial relationship consists of objects which have to be placed somewhere; locations with different shapes and configurations which serve as places, sources and goals/destinations; movement and trajectories of objects which are moving from one place to another along a certain path. 3 General terms for: - “moving objects” vs. “stationary places” – trajector and landmark, proposed by Langacker (1991). - “location / place” vs. “located object” – ground and figure / relatum and theme. We propose locum and localised.

Universiteit van Amsterdam Motion domain A motion event consists of - a trajector (tr), - a landmark (lm) and - a trajectory/path. tr motion source goal path 1) He sailed from Canada to Europe along the shortest route. tr motion source path 2) She came back from the market through the park.

Universiteit van Amsterdam Manner of the motion: tr manner path goal 3) We fell off into the water. - The manner of motion can be packaged together with the path in the verb stem verb-framed languages (Talmy 2000); - The manner of motion is expressed by a verb and the path is expressed by particles, prepositions, etc. satellites-framed languages; - The manner of motion and the path are expressed by equivalent grammatical forms equipollently-framed languages (Slobin 2006).

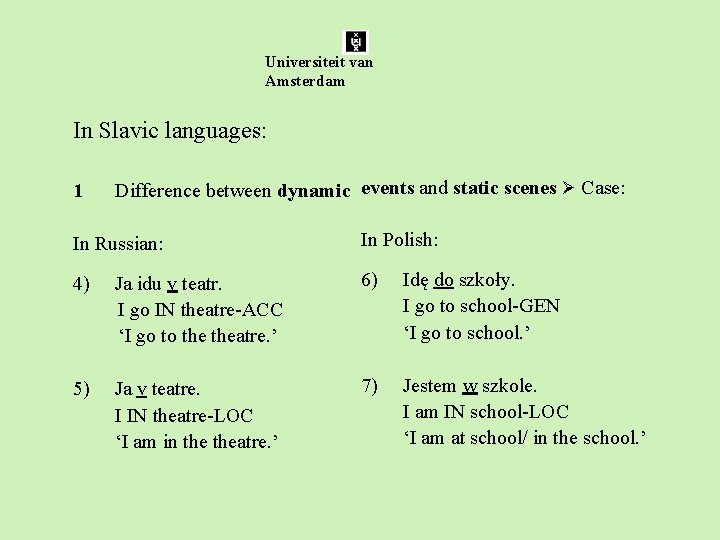

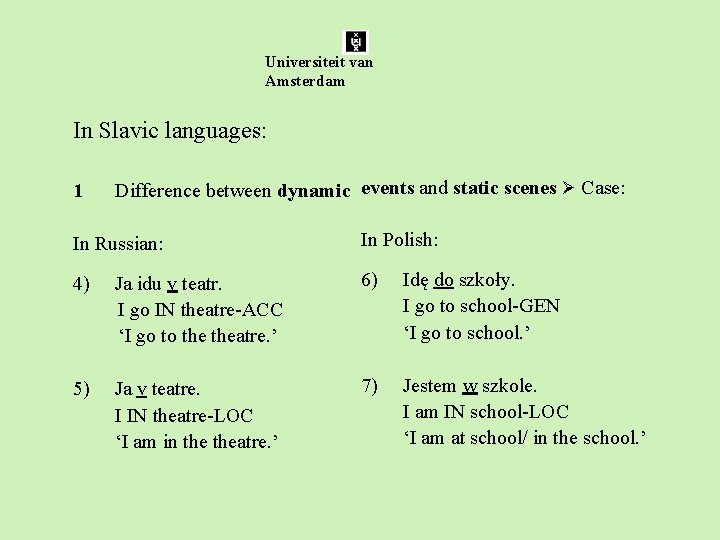

Universiteit van Amsterdam In Slavic languages: 1 Difference between dynamic events and static scenes Case: In Russian: In Polish: 4) Ja idu v teatr. I go IN theatre-ACC ‘I go to theatre. ’ 6) Idę do szkoły. I go to school-GEN ‘I go to school. ’ 5) 7) Jestem w szkole. I am IN school-LOC ‘I am at school/ in the school. ’ Ja v teatre. I IN theatre-LOC ‘I am in theatre. ’

Universiteit van Amsterdam 2 The final stage of the motion, type of contact between the trajector and the landmark/goal, is highlighted Case and prepositions - being in neighbouring space to the landmark/goal: In Russian: 8) Ja idu k škole. I go TOWARDS school-DAT ‘I go to school. ’ - reaching the landmark/goal: 9) Ja idu do školy. I go TO school-GEN ‘I go to school. ’

Universiteit van Amsterdam - being in contact with the landmark/goal: 10) Ja idu v školu. I go IN school-ACC ‘I go to school. ’ In Polish: 11) Idę do szkoły. I go to school-GEN ‘I go to school. ’

Universiteit van Amsterdam 3 Prefix-preposition harmony the repetition of the spatial notion expressed by a verbal prefix in the prepositional noun phrase (Genis 2008): In Polish: 12) Ania przeszła przez ulicę. Ania THROUGH‑walked THROUGH/ACROSS street-ACC ‘Ania crossed the street. ’ In Russian: 13) Ania vošla v školu. Ania IN-came IN school-ACC ‘Ania entered the school. ’

Universiteit van Amsterdam 4 Verbal aspect In Polish: 14) Ania przeszła przez ulicę. – Perf. verb Ania THROUGH‑walked THROUGH/ACROSS street-ACC ‘Ania crossed the street. ’ 15) Ania przeszła ulicę. – Perf. verb Ania THROUGH‑walked street-ACC ‘Ania crossed the street. ’/ ‘Ania walked past the street (she was looking for). ’ 16) Ania szła przez ulicę. – Imperf. verb Ania walked THROUGH/ACROSS street-ACC ‘Ania crossed the street. ’

Universiteit van Amsterdam Geometry/Topology Domain 1 2 Being in neighbouring space of the location. Being in contact with the location. - ‘single contact with the locum’ vs. ‘dispersal contact with the locum’: 17) 18) There is a speck of paint on the rug. There are specks of paint all over the rug. ‘being in contact with the vertical locum’ vs. ‘being in contact with the horizontal locum’; ‘adjacency’ vs. ‘support’: In Dutch: 19) 20) Een schilderij hangt aan de muur. ‘A painting hangs on the wall. ’ Zijn huis ligt aan het strand. ‘His house stands on the beach. ’

Universiteit van Amsterdam - ‘being in contact with container’ vs. ‘being in contact with surface’. 21) 22) There is a fly in the room. The book is on the table. 23) She stays with her friend at Cambridge. (= in the city) Dimensionality: - an ideal 3 -D location is a container, closed from all sides; an ideal 2 -D location is an open area or surface; an ideal 1 -D location is a boundary, line or a point.

Universiteit van Amsterdam 1 Dimensionality, based on ‘real’ characteristics of locations, determines the usage of spatial prepositions. (e. g. buildings, rooms, etc. are closed places; interpreted as containers and used with IN. Squares, beaches, etc. are open areas and thus are used with ON. ) 2 A location can be viewed as a point, when ignoring configurations. 3 Spatial features are not distinctive enough ambiguity in interpretation and conceptualisation of locations: IN is used with enclosures (e. g. in the circle, in the desert, in America or in - Moscow); Dutch OP ‘on’ is used with containers (e. g. op zijn kamer ‘in his room’, op zolder ‘in the garret’).

Universiteit van Amsterdam Cuyckens (1993; 27 -71) formulates a number of categories for IN-locations: - 3 -D, bounded, porous (car, airport, street, villa, embrace); 3 -D, bounded, non-porous (finger, fire, stone); 3 -D, unbounded, porous (mist/fog, clouds, air, universe); 3 -D, unbounded, non-porous (water, dust); 2 -D, bounded (face, village, city, England, field); 2 -D, unbounded (world).

![Universiteit van Amsterdam INCATEGORIES Podgaevskaja 2008 buildings with their functions compartments in buildings Universiteit van Amsterdam IN-CATEGORIES (Podgaevskaja 2008): - [buildings with their functions] [compartments in buildings]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/04e117a9fb1bf0e74dadd914515f69a2/image-14.jpg)

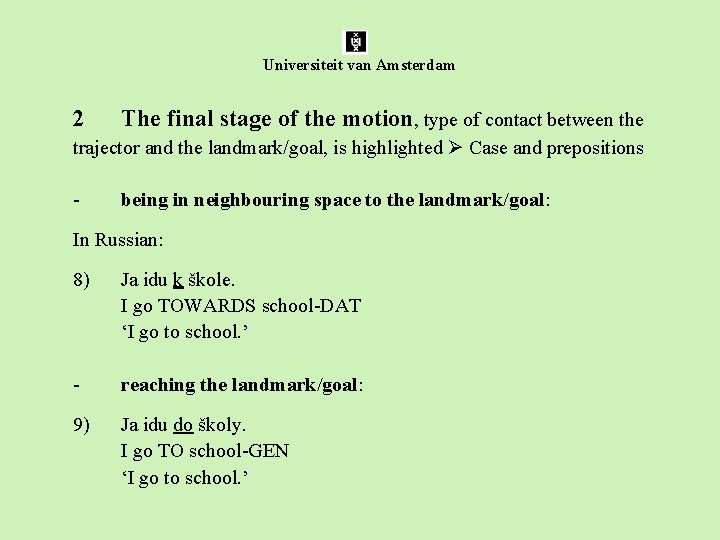

Universiteit van Amsterdam IN-CATEGORIES (Podgaevskaja 2008): - [buildings with their functions] [compartments in buildings] [administrative/political units] [bounded enclosed areas] (park, garden, monastery, fortress) - [enclosed extensive homogenous areas with(out) vegetation] (tundra, forest, desert, jungle, prairie) - [enclosed extensive water areas] (strait, gulf, bay, harbour)

![Universiteit van Amsterdam ONCATEGORIES elevations of the earths surface enclosed by water island Universiteit van Amsterdam ON-CATEGORIES: - elevations of the earth’s surface, enclosed by water] (island,](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/04e117a9fb1bf0e74dadd914515f69a2/image-15.jpg)

Universiteit van Amsterdam ON-CATEGORIES: - elevations of the earth’s surface, enclosed by water] (island, peninsula, continent, hill, mountain) - [small field-like areas] (field, meadow, plot) - [small pieces of land, cultivated by people] (plantation, vineyard, market, square, bus stop, playground, court) - [strips of land] (street, road, beach, shore, coast) - [upper part of vertical entities] (garret, attic, tree) - [water basins surrounded by land] (ocean, sea, river, pool, canal, waterfall) - [buildings with functions, surrounded by a piece of land] (factory, station, farm, mill)

Universiteit van Amsterdam IN- and ON-categories the opposition of cognitive features: - IN ON ‘three‑dimensionality’ ↔ ‘two‑dimensionality’; ‘completely enclosed’ ↔ ‘partially enclosed’; ‘profiled boundaries’ ↔ ‘profiled two-dimensional interior’; ‘clear boundaries’ ↔ ‘fuzzy boundaries’; ‘verticality’ ↔ ‘supporting surface’; ‘large extendedness’ ↔ ‘small extendedness’; ‘homogeneity’ ↔ ‘heterogeneity’; ‘down’ ↔ ‘up’; ‘absorption into the space’ ↔ ‘control over the space’; ‘unfamiliar/strange’ ↔ ‘familiar’.

Universiteit van Amsterdam Egofocality Slavic native speakers focus on either one of two matters: - the contained space within the boundaries of a locum: - the area of contact between localised and locum:

Universiteit van Amsterdam In Russian: 24) V kuxne potolok šël skošeno. in kitchen-LOC ceiling-NOM went oblique ‘In the kitchen the ceiling was oblique. ’ 25) Ona na kuxne pozvjakivala kastr’ul’ami. she ON kitchen-LOC was tinkling with pans-INSTR ‘She was tinkling with the pans in the kitchen. ’ In Polish: 26) Nikt w/na zamku nie mieszka. nobody IN/ON castle-LOC not lives ‘Nobody lives at/in the castle. ’

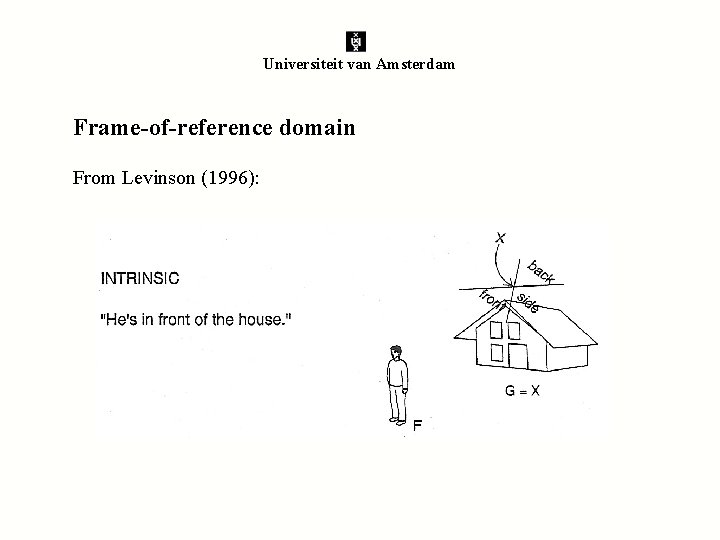

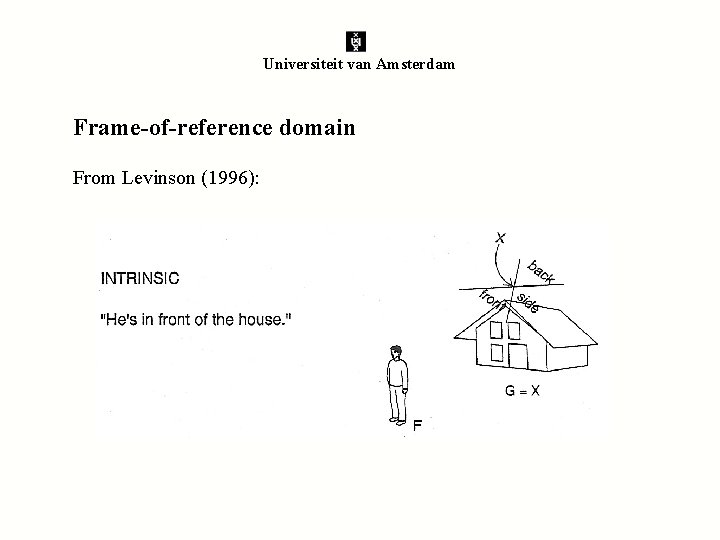

Universiteit van Amsterdam Frame-of-reference domain From Levinson (1996):

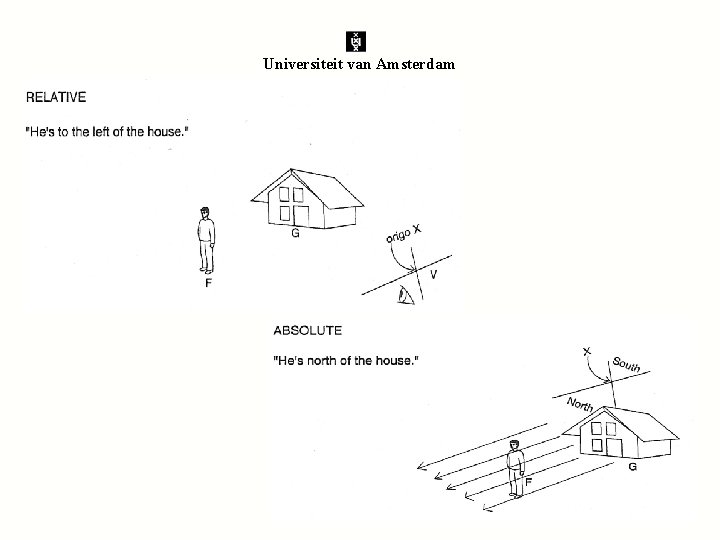

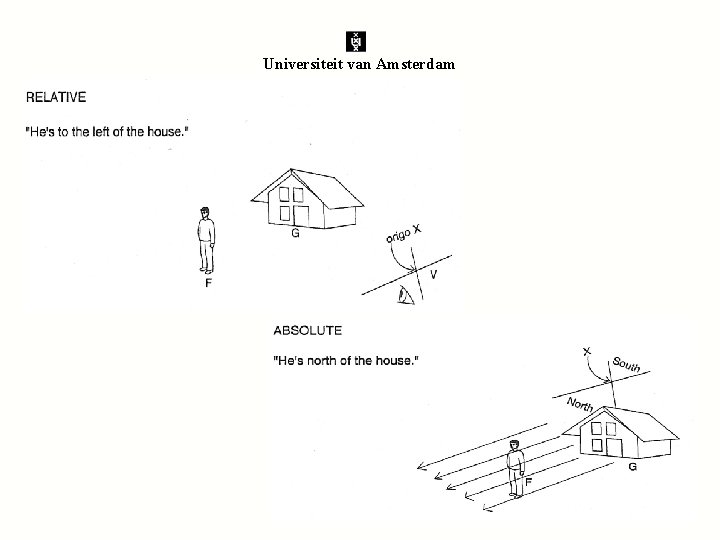

Universiteit van Amsterdam

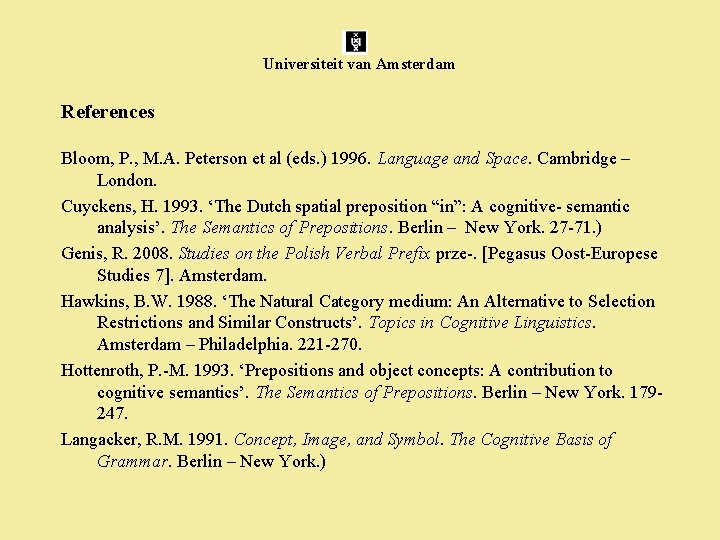

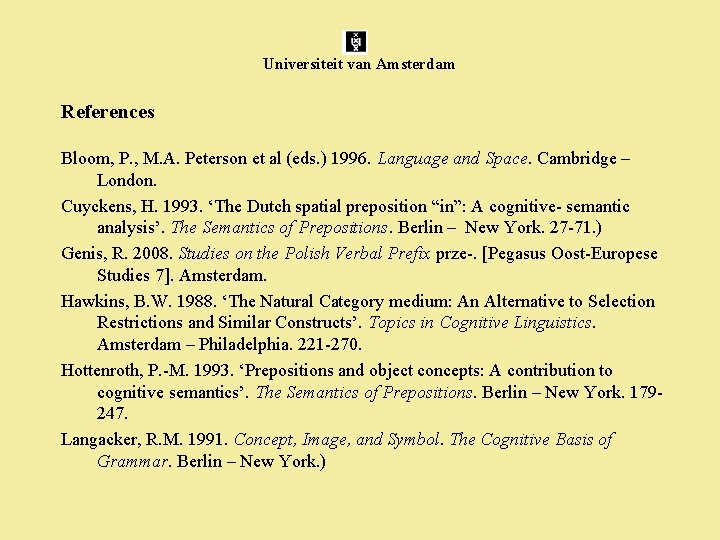

Universiteit van Amsterdam In Polish: 1. 2. 3. 27) Ruszyli ostro zaraz sprzed domu. tore away FROM OUT IN FRONT OF house-GEN ‘They tore away from in front of the house. ’ 4. In Russian: 5. 6. 7. 28) Oni vyšli iz-za doma. they out-went FROM OUT BEHIND house-GEN ‘They came from behind the house. ’

Universiteit van Amsterdam In short, - highlighting of geometrical configurations of LM in static and dynamic events; - presupposed knowledge of the whole motion scene and focus on the final stage of the motion; - prefix-preposition harmony; - egofocality; - mapping of motion events onto given static locative situations; division of space around a location into segments which could be interpreted as bounded entities; - relevance of verbal aspect when reaching the goal.

Universiteit van Amsterdam References Bloom, P. , M. A. Peterson et al (eds. ) 1996. Language and Space. Cambridge – London. Сuyckens, H. 1993. ‘The Dutch spatial preposition “in”: A cognitive- semantic analysis’. The Semantics of Prepositions. Berlin – New York. 27 -71. ) Genis, R. 2008. Studies on the Polish Verbal Prefix prze-. [Pegasus Oost-Europese Studies 7]. Amsterdam. Hawkins, B. W. 1988. ‘The Natural Category medium: An Alternative to Selection Restrictions and Similar Constructs’. Topics in Cognitive Linguistics. Amsterdam – Philadelphia. 221 -270. Hottenroth, P. -M. 1993. ‘Prepositions and object concepts: A contribution to cognitive semantics’. The Semantics of Prepositions. Berlin – New York. 179247. Langacker, R. M. 1991. Concept, Image, and Symbol. The Cognitive Basis of Grammar. Berlin – New York. )

Universiteit van Amsterdam Levinson S. C. , 1996. ‘Frames of Reference and Molyneux’s Question: Crosslinguistic Evidence’. Language and space. Cambridge – London. Levinson, S. C. 2003. Space in Language and Cognition: Explorations in Cognitive Diversity. Cambridge. Levinson, S. C. , Wilkins, D. (eds. ) 2006. Grammars of Space. Cambridge. Podgaevskaja, A. 2008. Konceptualizacija prostranstva i jejo otraženie v russkom jazyke /Ruimtelijke conceptualisering in het Russisch. [Pegasus Oost-Europese Studies 10]. Amsterdam. Shay, E. , Seibert, U. (eds. ) 2003. Motion, Destination and Location in Languages. Amsterdam – Philadelphia. Slobin, D. I. 2006, ‘What makes manner of motion salient? Explorations in linguistic typology, discourse, and cognition’. Space in Languages: Linguistic Systems ans Cognitive Categories. Amsterdam – Philadelphia. ) Zee, E. van der, J. Slack (eds. ) 2003. Representing Direction in Language and Space. Oxford. Talmy, L. 2000. Cognitive semantics. Cambridge. Ungerer, F. , H. J. Schmid 1997. An Introduction to Cognitive Linguistics. London – New York.