Special Topics in Distributed Computing Shared Memory Algorithms

Special Topics in Distributed Computing: Shared Memory Algorithms Seth Gilbert http: //lpd. epfl. ch Professor: Rachid Guerraoui Assistants: M. Kapalka and A. Dragojevic Distributed Programming Laboratory © R. Guerraoui 1

This course introduces a theory of robust and concurrent computing… 2

Major chip manufacturers have recently announced a major paradigm shift: New York Times, 8 May 2004: Intel … [has] decided to focus its development efforts on «dual core» processors … with two engines instead of one, allowing for greater efficiency because the processor workload is essentially shared. Multi-processors and Multicores vs faster processors (Thanks for the quote, Maurice Herlihy. ) 3

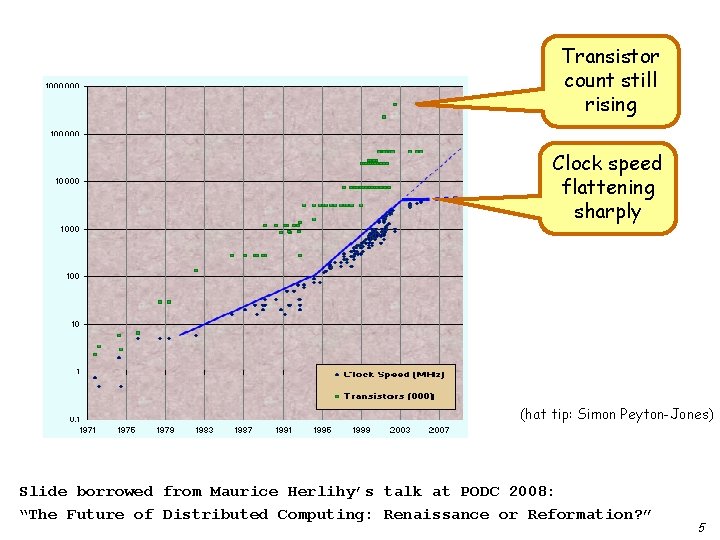

The clock speed of a processor cannot be increased without overheating. But More and more processors can fit in the same space. 4

Transistor count still rising Clock speed flattening sharply (hat tip: Simon Peyton-Jones) Slide borrowed from Maurice Herlihy’s talk at PODC 2008: “The Future of Distributed Computing: Renaissance or Reformation? ” 5

Speed will be achieved by having several processors work on independent parts of a task. But The processors would occasionally need to pause and synchronize. But If the task is shared, then pure parallelism is usually impossible and, at best, inefficient. 6

Concurrent computing for the masses Forking processes might be more frequent But… Concurrent accesses to shared objects might become more problematic and harder. 7

How do devices synchronize? Concurrent processes Shared object 8

How do devices synchronize? Locking (mutual exclusion) 9

How do devices synchronize? One process at a time Locked object 10

How do devices synchronize? Locking (mutual exclusion) Difficult: 50% of the bugs reported in Java come from the use of « synchronized » Fragile: a process holding a lock prevents all others from progressing Other: deadlock, livelock, priority inversion, etc. 11

Why is locking hard? Processes are asynchronous Page faults Pre-emptions Failures Cache misses, … A process can be delayed by millions of instructions … 12

Alternative to locking? 13

Wait-free atomic objects Wait-freedom: every process that invokes an operation eventually returns from the invocation o Robust … unlike locking. Atomicity: every operation appears to execute instantaneously. o As if the object were locked. 14

In short This course shows how to wait-free implement high-level atomic objects out of more primitive base objects. 15

Concurrent processes Shared object 16

Administrative Issues Timing: • Class: Monday 9: 15 -11: 00 • Exercise sessions: Monday 11: 15 -12: 00 – Room: BC 03 – First session: Week 3 Text book: • None. Handouts on the webpage. Final Exam: Written, closed-book, date/time/room TBA. 17

Administrative Issues What about the other class? « Distributed Computing » Monday, 15: 15 -17: 00, ELA 01 • The courses are complementary. – This course: shared memory. – Other course: message passing. • Consider taking both! (Recommended…) 18

Today’s Lecture: 1. Introduction: • What is the goal of this course? 2. Model: • Processes and objects • Atomicity • Wait-freedom 3. Examples 19

Processes We assume a finite set of processes: – Processes have unique identifiers. – Processes are denoted as or « p, q, r » « p 1, …, p. N » – Processes know each other. – Processes can coordinate via shared objects. 20

Processes We assume a finite set of processes: – Each process models a sequential program. – Each clock tick each process takes a step. – In each step, a process: a) Performs some computation. (LOCAL) b) Initiates an operation on a shared object. (GLOBAL) c) Receives a response from an operation. (GLOBAL) – We make no assumptions on process (relative) speeds. (Asynchronous) 21

Processes p 1 p 2 p 3 22

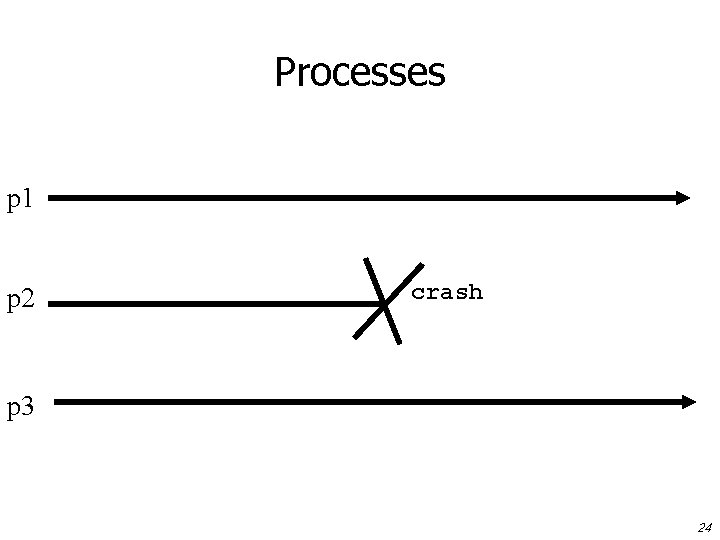

Processes Crash Failures: A process either executes the algorithm assigned to it or crashes. A process that crashes does not recover. A process that does not crash in a given execution (computation or run) is called correct (in that execution). 23

Processes p 1 p 2 crash p 3 24

On objects and processes Processes interact via shared objects: A process can initiate an operation on a particular object. Every operation is expected to return a reply. Each process can initiate only one operation at a time. 25

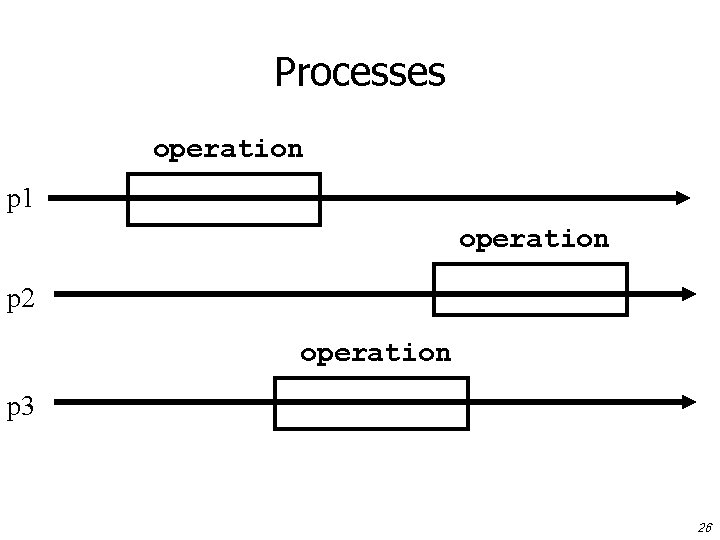

Processes operation p 1 operation p 2 operation p 3 26

On objects and processes Sequentiality: – After invoking an operation op 1 on some object O 1… – A process does not invoke a new operation on the same or on some other object… – Until it receives the reply for op 1. Remark. Sometimes we talk about operations when we should be talking about operation invocations 27

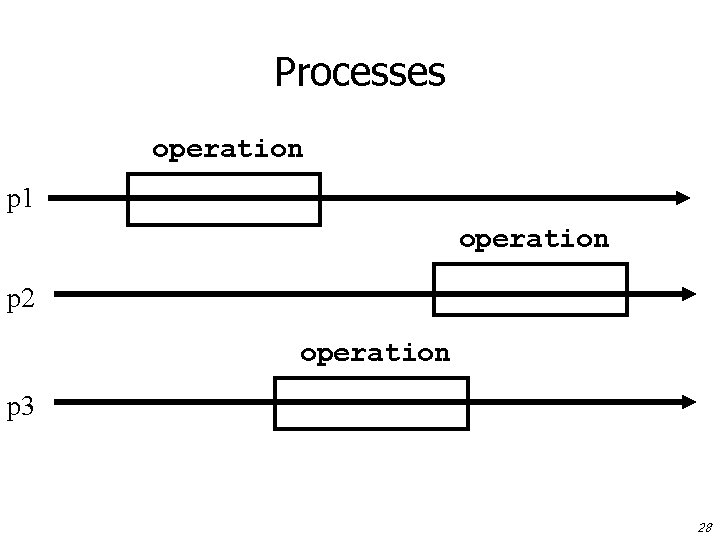

Processes operation p 1 operation p 2 operation p 3 28

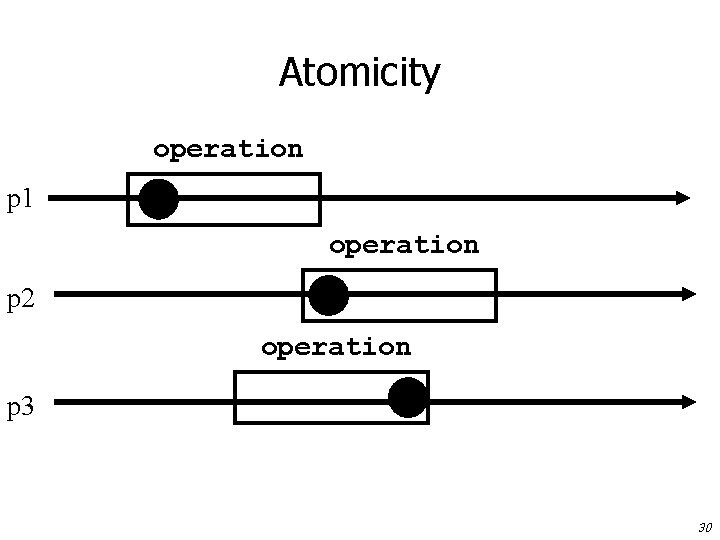

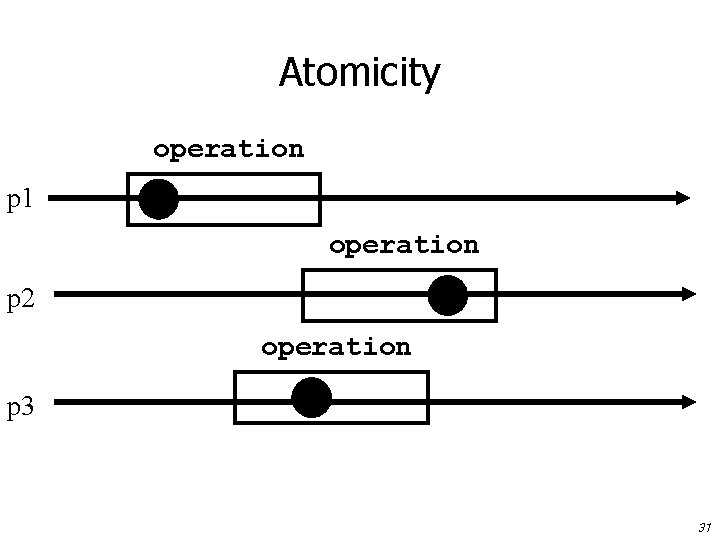

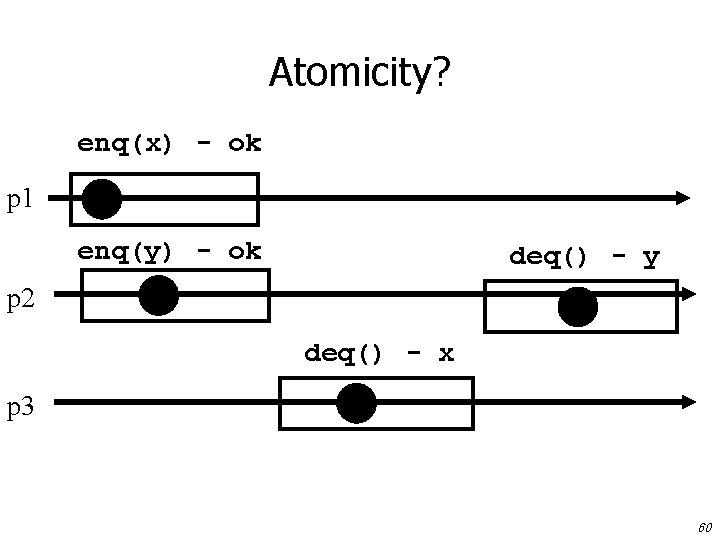

Atomicity We mainly focus in this course on how to implement atomic objects. Atomicity (or linearizability): – Every operation appears to execute at some indivisible point in time. – This is called the linearization point. – This point is between the invocation and the reply. 29

Atomicity operation p 1 operation p 2 operation p 3 30

Atomicity operation p 1 operation p 2 operation p 3 31

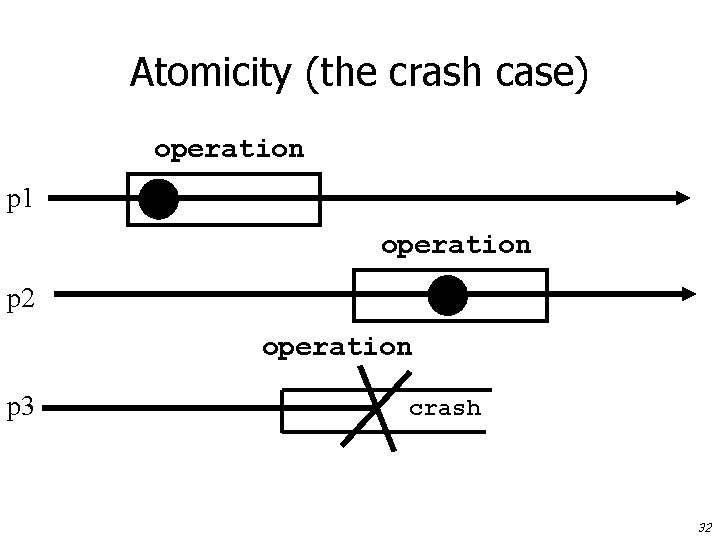

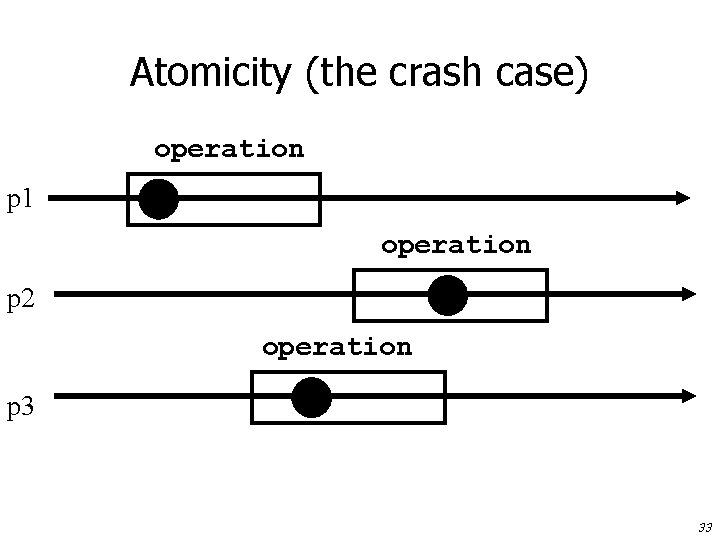

Atomicity (the crash case) operation p 1 operation p 2 operation p 3 crash 32

Atomicity (the crash case) operation p 1 operation p 2 operation p 3 33

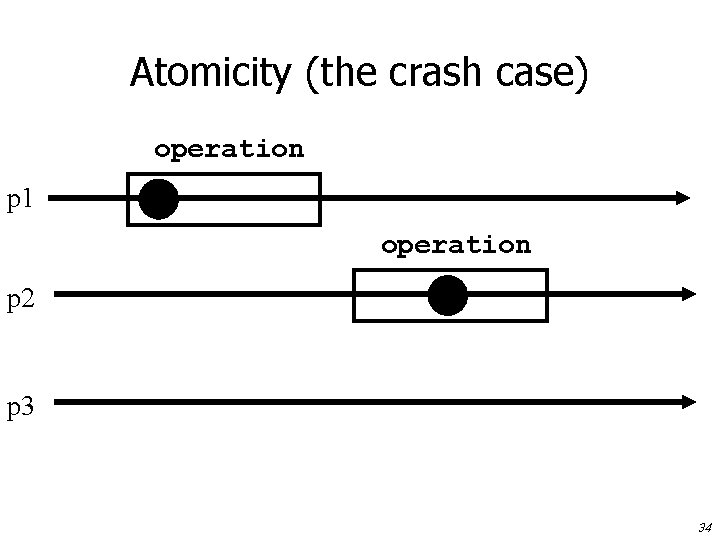

Atomicity (the crash case) operation p 1 operation p 2 p 3 34

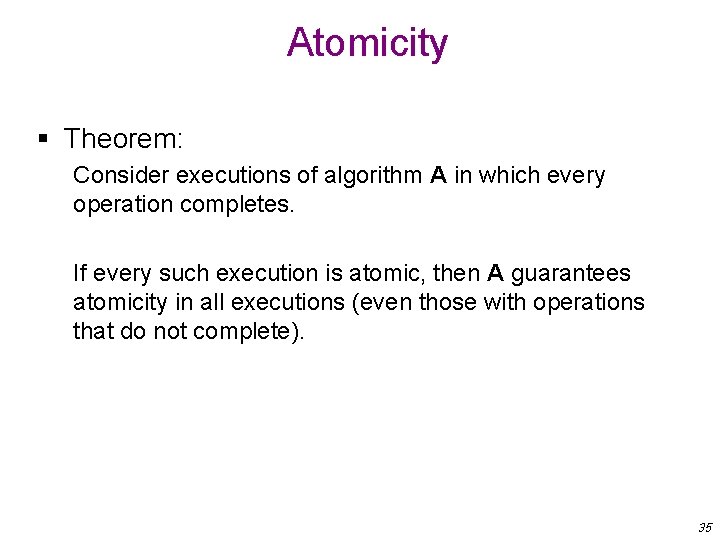

Atomicity § Theorem: Consider executions of algorithm A in which every operation completes. If every such execution is atomic, then A guarantees atomicity in all executions (even those with operations that do not complete). 35

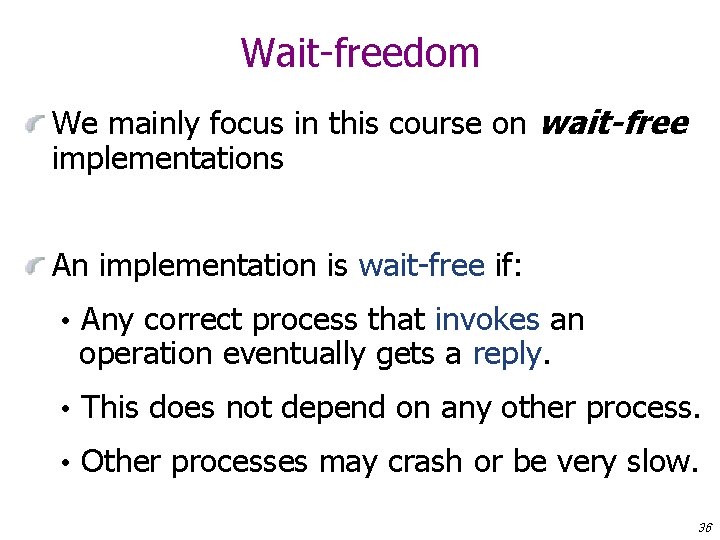

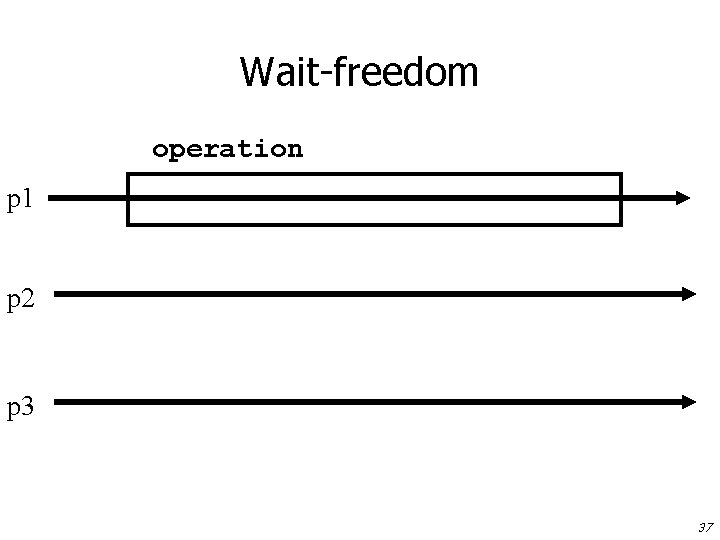

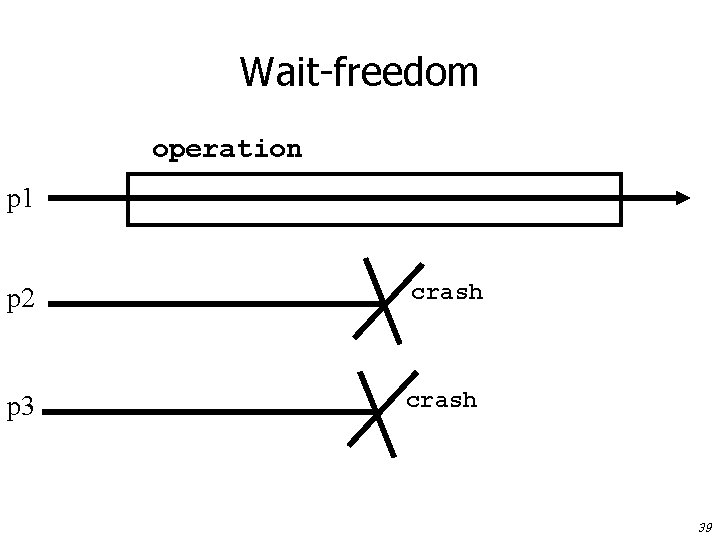

Wait-freedom We mainly focus in this course on wait-free implementations An implementation is wait-free if: • Any correct process that invokes an operation eventually gets a reply. • This does not depend on any other process. • Other processes may crash or be very slow. 36

Wait-freedom operation p 1 p 2 p 3 37

Wait-freedom conveys the robustness of the implementation With a wait-free implementation, a process gets replies despite the crash of the n-1 other processes Note that this precludes implementations based on locks (i. e. , mutual exclusion). 38

Wait-freedom operation p 1 p 2 crash p 3 crash 39

Today’s Lecture: 1. Introduction: • What is the goal of this course? 2. Model: • Processes and objects • Atomicity • Wait-freedom 3. Examples 40

Motivation Most synchronization primitives (problems) can be precisely expressed as atomic objects (implementations) Studying how to ensure robust synchronization boils down to studying wait-free atomic object implementations 41

Example 1 The reader/writer synchronization problem corresponds to the register object Basically, the processes need to read or write a shared data structure such that the value read by a process at a time t, is the last value written before t 42

Register A register has two operations: – read() – write() Assume (for simplicity) that: – a register contains an integer – the register is denoted by x – the register is initially 0 43

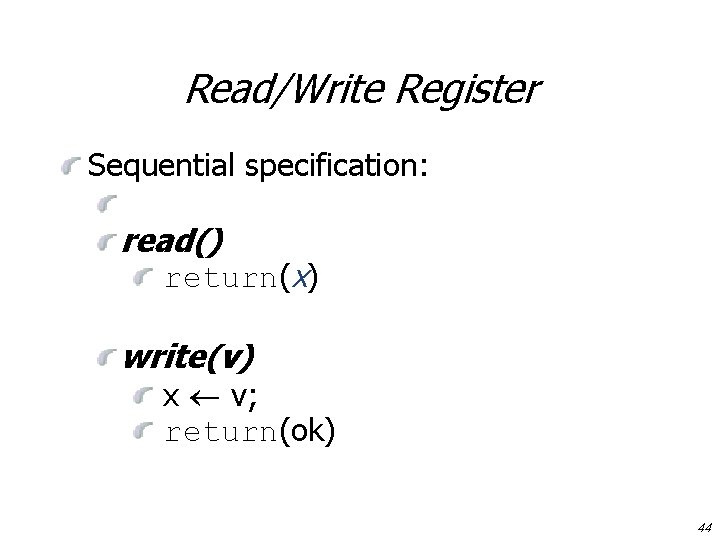

Read/Write Register Sequential specification: read() return(x) write(v) x v; return(ok) 44

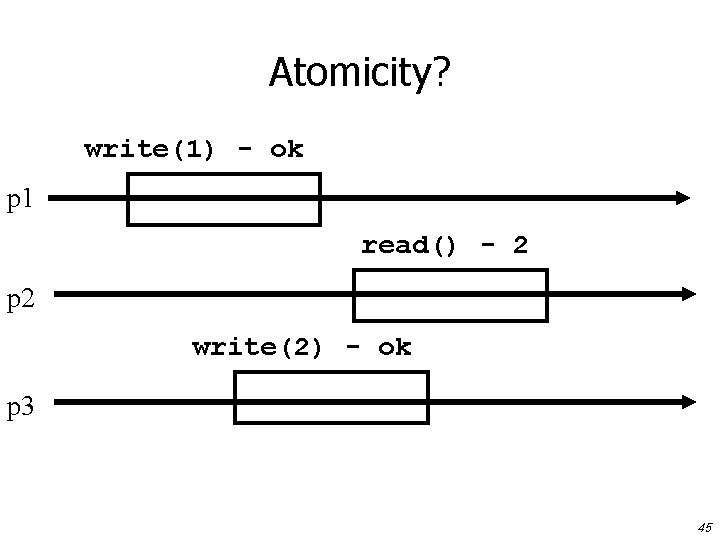

Atomicity? write(1) - ok p 1 read() - 2 p 2 write(2) - ok p 3 45

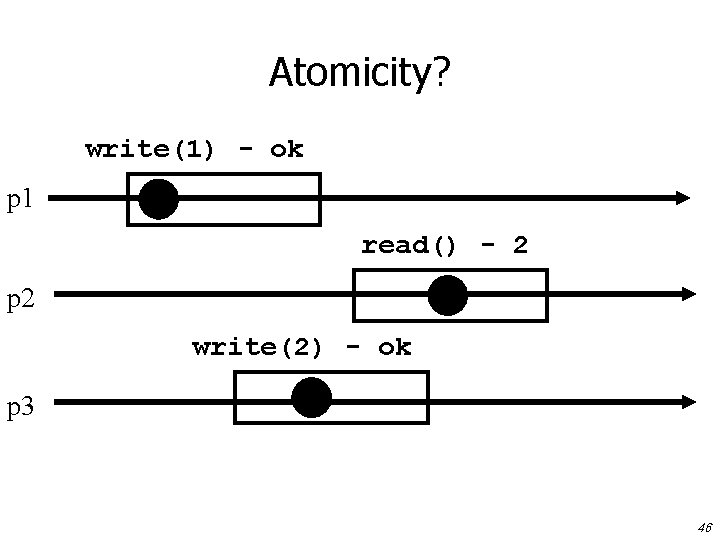

Atomicity? write(1) - ok p 1 read() - 2 p 2 write(2) - ok p 3 46

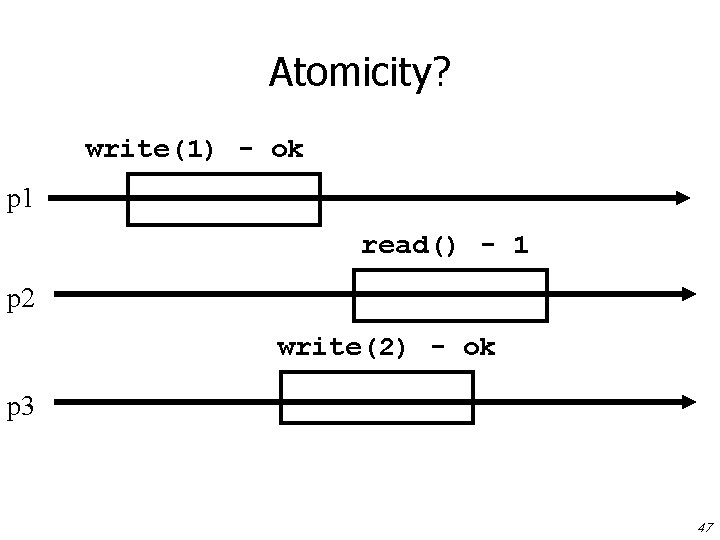

Atomicity? write(1) - ok p 1 read() - 1 p 2 write(2) - ok p 3 47

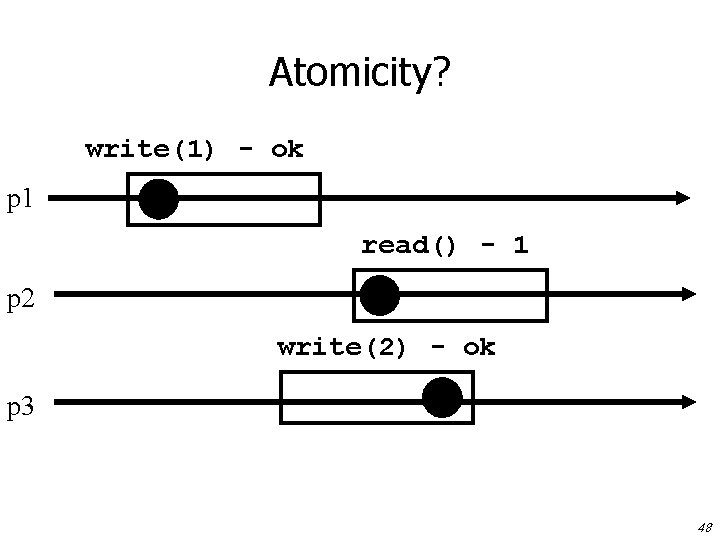

Atomicity? write(1) - ok p 1 read() - 1 p 2 write(2) - ok p 3 48

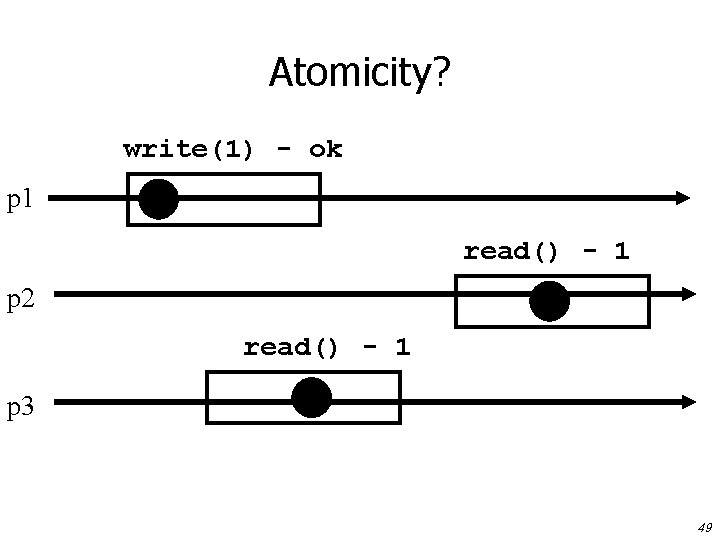

Atomicity? write(1) - ok p 1 read() - 1 p 2 read() - 1 p 3 49

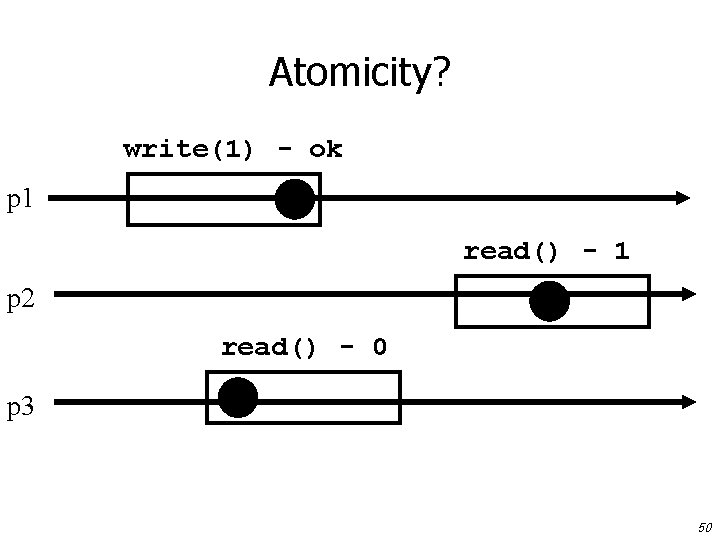

Atomicity? write(1) - ok p 1 read() - 1 p 2 read() - 0 p 3 50

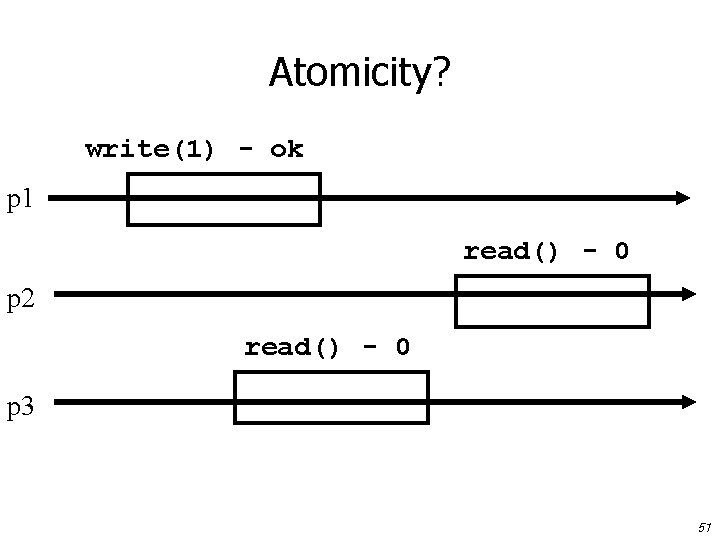

Atomicity? write(1) - ok p 1 read() - 0 p 2 read() - 0 p 3 51

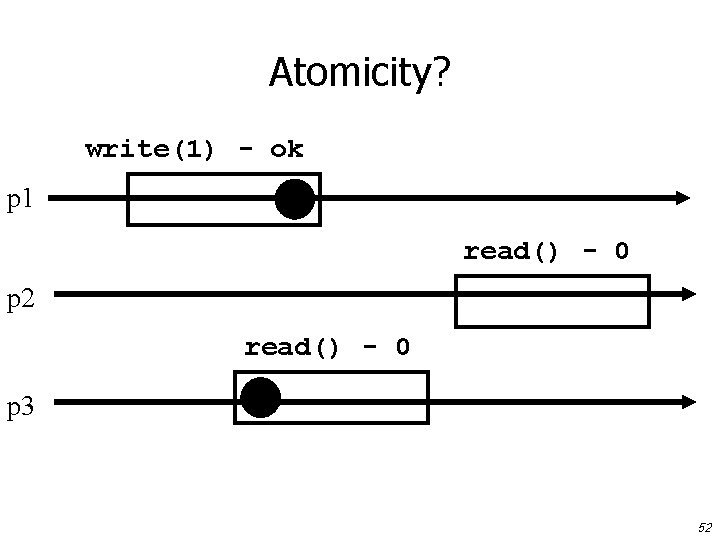

Atomicity? write(1) - ok p 1 read() - 0 p 2 read() - 0 p 3 52

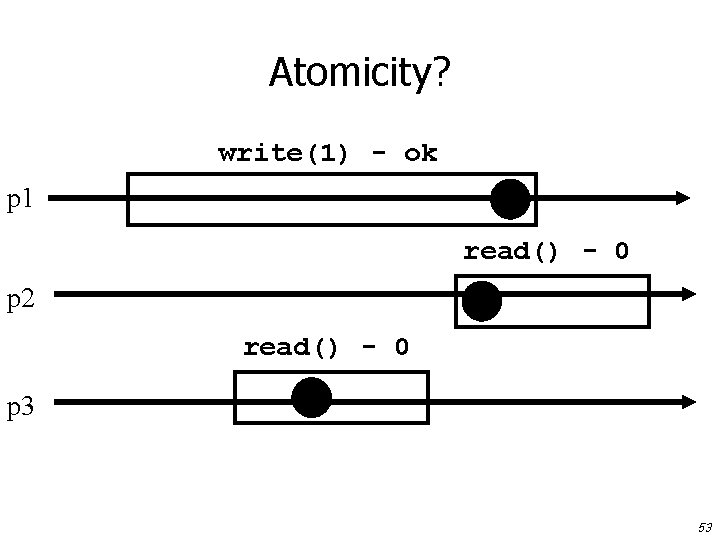

Atomicity? write(1) - ok p 1 read() - 0 p 2 read() - 0 p 3 53

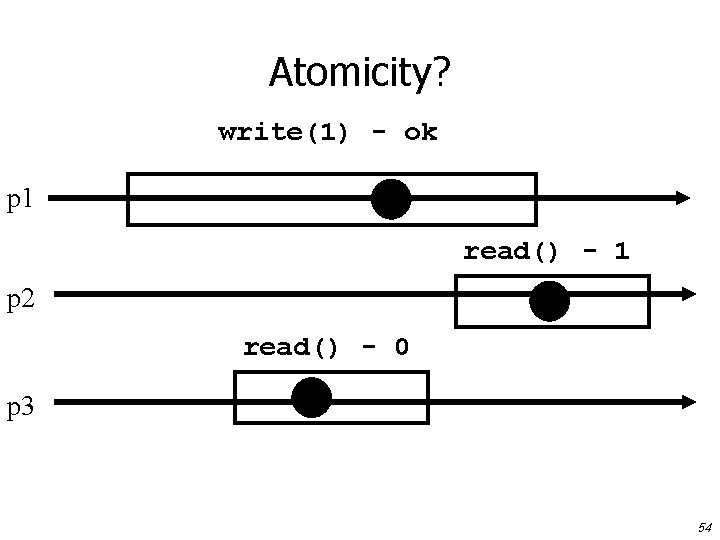

Atomicity? write(1) - ok p 1 read() - 1 p 2 read() - 0 p 3 54

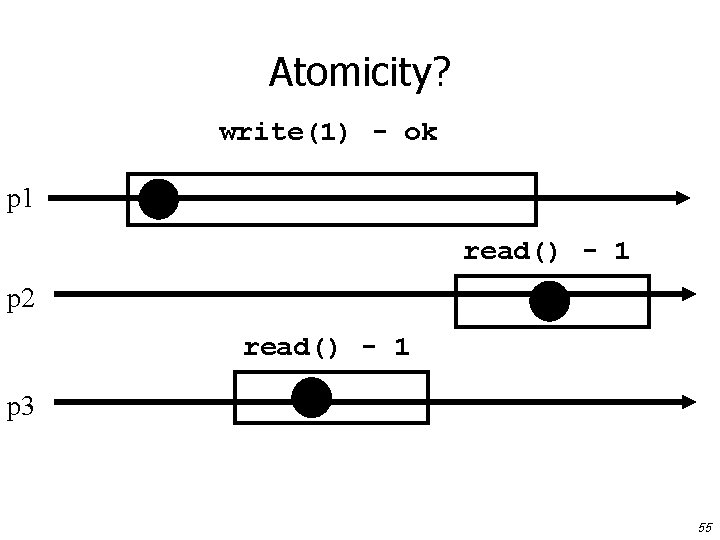

Atomicity? write(1) - ok p 1 read() - 1 p 2 read() - 1 p 3 55

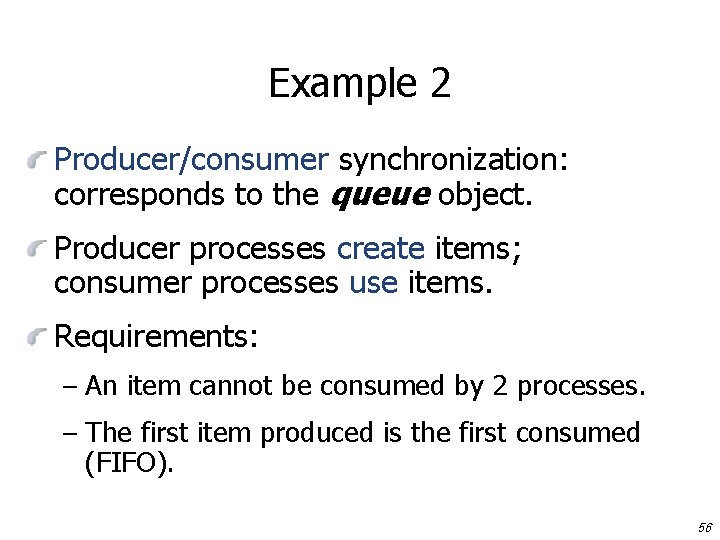

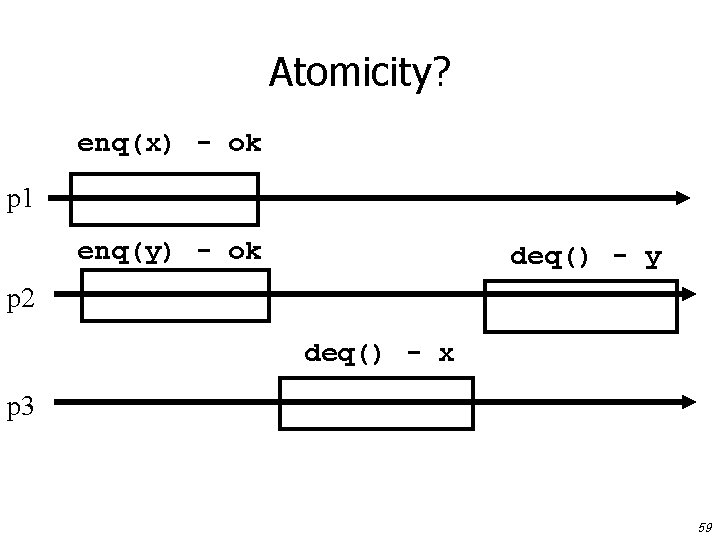

Example 2 Producer/consumer synchronization: corresponds to the queue object. Producer processes create items; consumer processes use items. Requirements: – An item cannot be consumed by 2 processes. – The first item produced is the first consumed (FIFO). 56

Queue A queue has two operations: enqueue() and dequeue() We assume that a queue internally maintains a list x which supports: – append(): put an item at the end of the list; – remove(): remove an element from the head of the list. 57

Sequential specification dequeue() if (x = 0) then return(nil); else return(x. remove()) enqueue(v) x. append(v); return(ok) 58

Atomicity? enq(x) - ok p 1 enq(y) - ok deq() - y p 2 deq() - x p 3 59

Atomicity? enq(x) - ok p 1 enq(y) - ok deq() - y p 2 deq() - x p 3 60

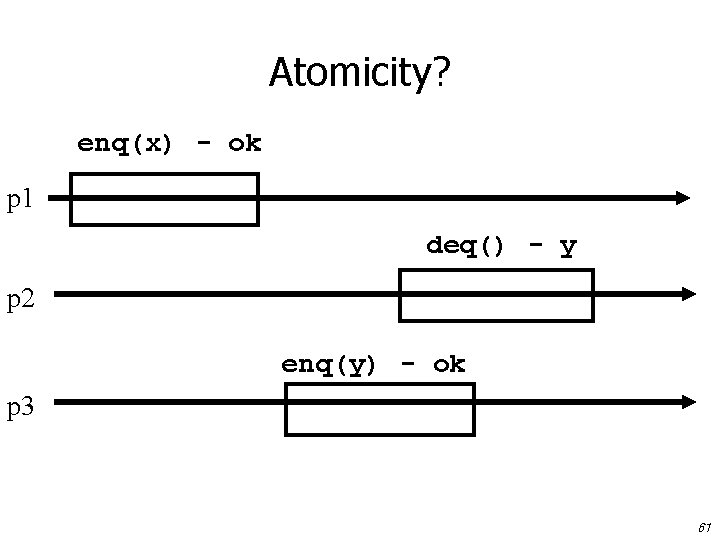

Atomicity? enq(x) - ok p 1 deq() - y p 2 enq(y) - ok p 3 61

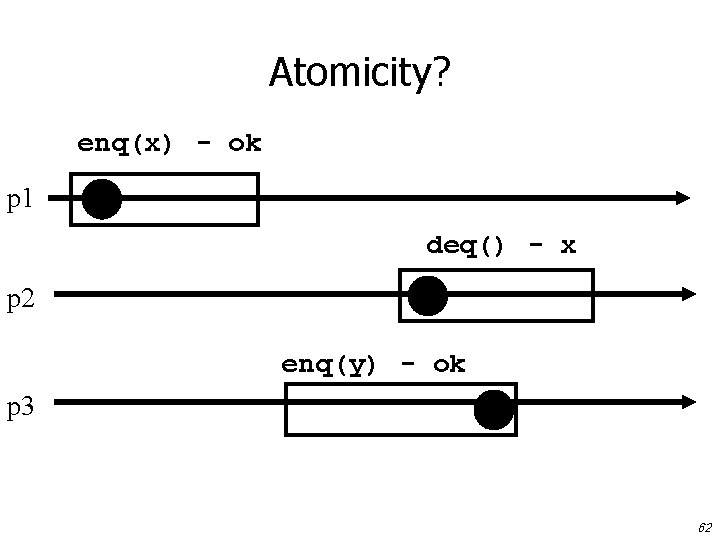

Atomicity? enq(x) - ok p 1 deq() - x p 2 enq(y) - ok p 3 62

Content (1) Implementing registers (2) The power & limitation of registers (3) Universal objects & synchronization number (4) The power of time & failure detection (5) Tolerating failure prone objects (6) Anonymous implementations (7) Transaction memory 63

In short This course shows how to wait-free implement high-level atomic objects out of basic objects Remark: unless explicitely stated otherwise: objects mean atomic objects and implementations are wait-free. 64

- Slides: 64