Special Considerations in the Female Athlete Carrie A

- Slides: 47

Special Considerations in the Female Athlete Carrie A Jaworski, MD, FACSM, FAAFP Director, Division of Primary Care Sports Medicine North. Shore University Health. System Assistant Clinical Professor University of Chicago

Objectives Review several commonly encountered issues related to the female athlete Gain insight into research gaps in caring for female athletes’ medical concerns Learn tools in diagnosis and treatment of medical issues related to the female athlete

Scenario #1 A sophomore XC runner presents with her second case of B tibial stress fractures. You had seen her as a freshman, when she was new to running. You addressed her biomechanical issues with PT and a home exercise program at that time. Why would she be injured again? ? What do you want to know? ?

Scenario #1 Exam: Healthy appearing female Height = 66 inches, Weight = 155 lbs BMI = 25 Pulse = 68, BP = 110/60 (no orthostatic changes) Normal skin, HEENT CV, Lungs, abdomen normal + ttp along anterior aspect of distal tibia bilaterally Remainder of exam normal

Scenario #1 Normal menses Denies hx of eating disorder Food recall for prior day Breakfast Protein Bar Water Lunch Salad Water Dinner Salad Water

Energy Availability and Disordered Eating • Majority of athletes do not meet diagnostic criteria for Anorexia or Bulimia • Many feel disordered eating practices are harmless • Still at significant risk for associated medical and psychological sequelae Do exhibit issues with energy availability

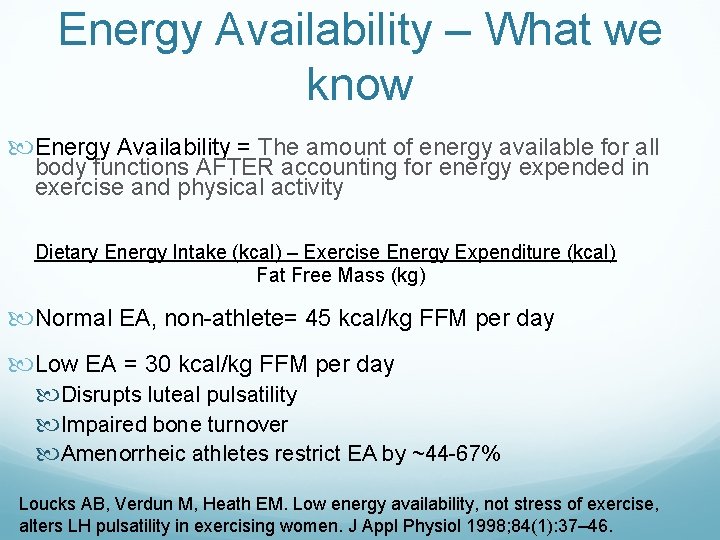

Energy Availability – What we know Energy Availability = The amount of energy available for all body functions AFTER accounting for energy expended in exercise and physical activity Dietary Energy Intake (kcal) – Exercise Energy Expenditure (kcal) Fat Free Mass (kg) Normal EA, non-athlete= 45 kcal/kg FFM per day Low EA = 30 kcal/kg FFM per day Disrupts luteal pulsatility Impaired bone turnover Amenorrheic athletes restrict EA by ~44 -67% Loucks AB, Verdun M, Heath EM. Low energy availability, not stress of exercise, alters LH pulsatility in exercising women. J Appl Physiol 1998; 84(1): 37– 46.

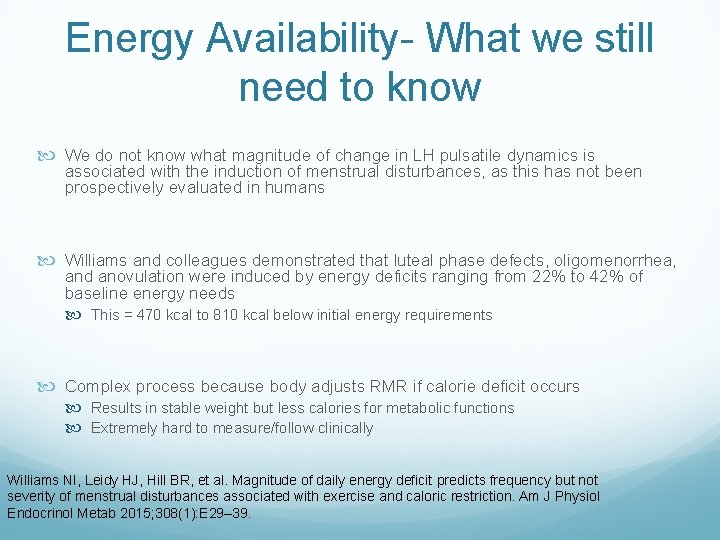

Energy Availability- What we still need to know We do not know what magnitude of change in LH pulsatile dynamics is associated with the induction of menstrual disturbances, as this has not been prospectively evaluated in humans Williams and colleagues demonstrated that luteal phase defects, oligomenorrhea, and anovulation were induced by energy deficits ranging from 22% to 42% of baseline energy needs This = 470 kcal to 810 kcal below initial energy requirements Complex process because body adjusts RMR if calorie deficit occurs Results in stable weight but less calories for metabolic functions Extremely hard to measure/follow clinically Williams NI, Leidy HJ, Hill BR, et al. Magnitude of daily energy deficit predicts frequency but not severity of menstrual disturbances associated with exercise and caloric restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2015; 308(1): E 29– 39.

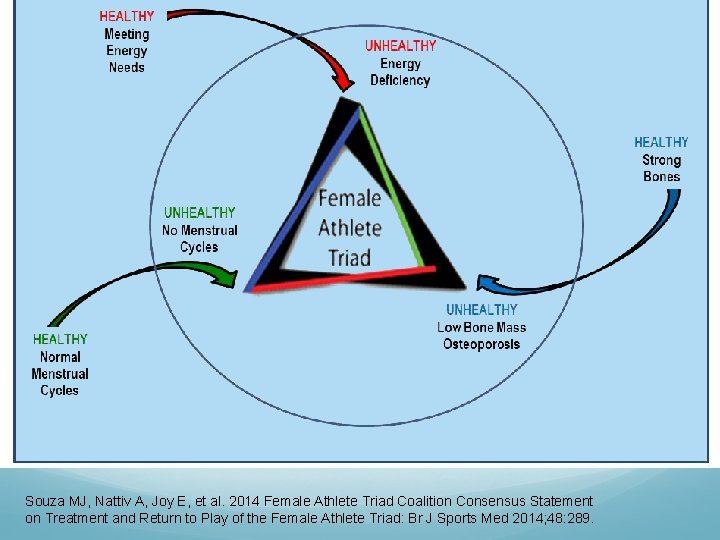

Low energy availability – What to remember Low EA can occur due to: Disordered eating Clinical Eating Disorder Intentional weight loss without disordered eating Inadvertent undereating Regardless of cause, results in cascade of physiologic and neuroendocrine adaptations Approach should target cause Souza MJ, Nattiv A, Joy E, et al. 2014 Female Athlete Triad Coalition Consensus Statement on Treatment and Return to Play of the Female Athlete Triad: Br J Sports Med 2014; 48: 289.

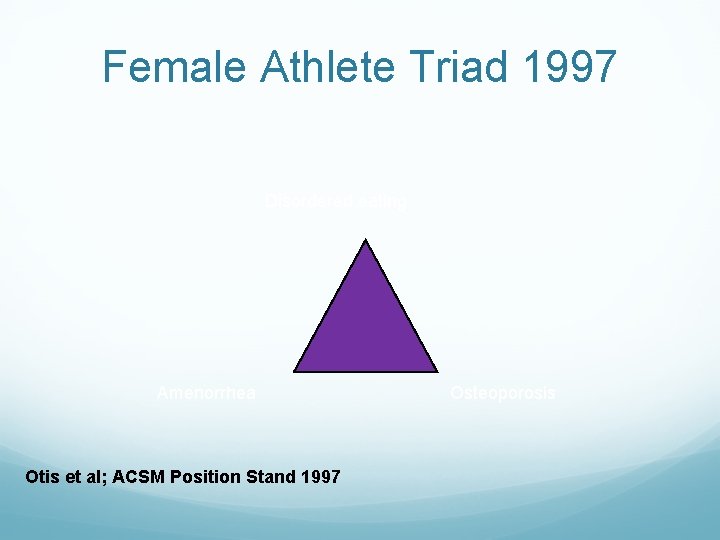

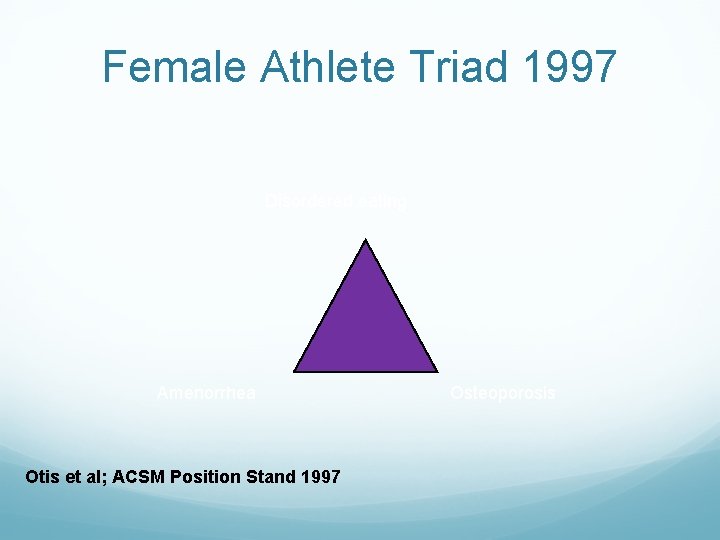

Female Athlete Triad 1997 Disordered eating Amenorrhea Otis et al; ACSM Position Stand 1997 Osteoporosis

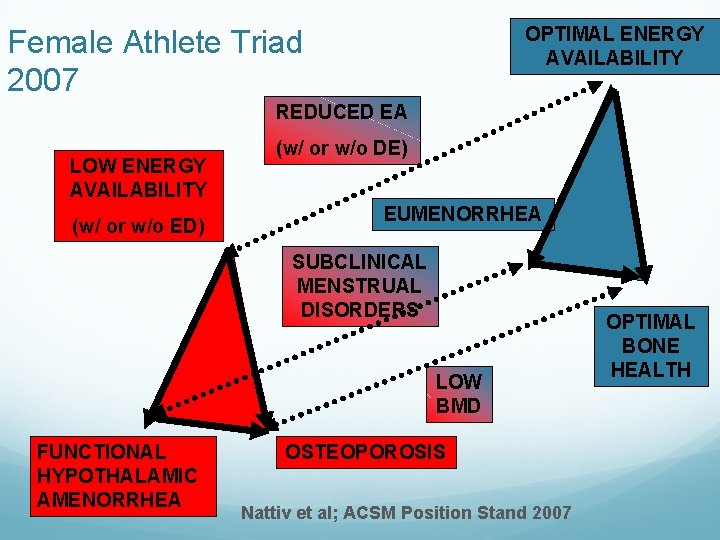

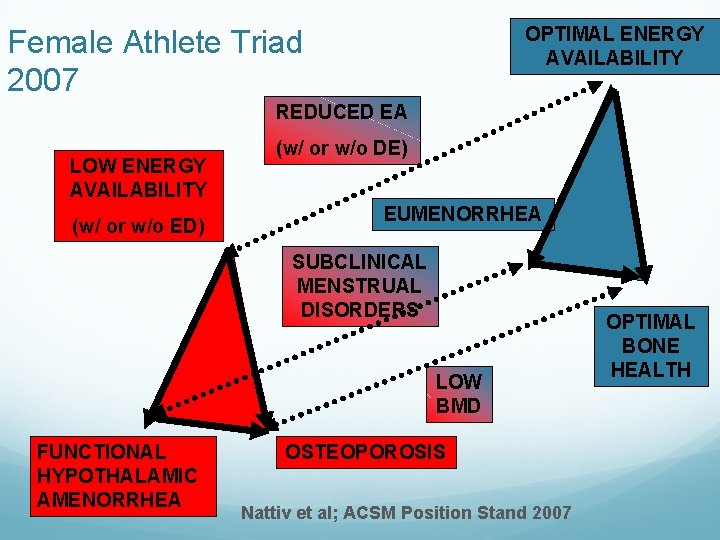

OPTIMAL ENERGY AVAILABILITY Female Athlete Triad 2007 REDUCED EA LOW ENERGY AVAILABILITY (w/ or w/o ED) (w/ or w/o DE) EUMENORRHEA SUBCLINICAL MENSTRUAL DISORDERS LOW BMD FUNCTIONAL HYPOTHALAMIC AMENORRHEA OSTEOPOROSIS Nattiv et al; ACSM Position Stand 2007 OPTIMAL BONE HEALTH

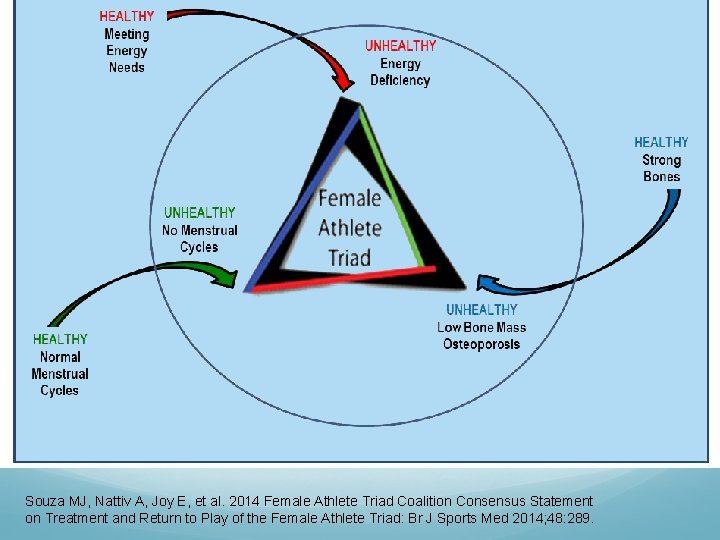

Souza MJ, Nattiv A, Joy E, et al. 2014 Female Athlete Triad Coalition Consensus Statement on Treatment and Return to Play of the Female Athlete Triad: Br J Sports Med 2014; 48: 289.

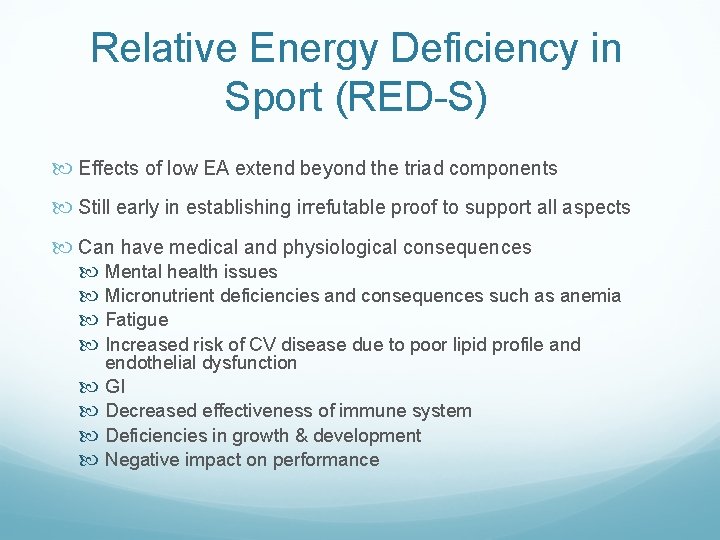

Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) Effects of low EA extend beyond the triad components Still early in establishing irrefutable proof to support all aspects Can have medical and physiological consequences Mental health issues Micronutrient deficiencies and consequences such as anemia Fatigue Increased risk of CV disease due to poor lipid profile and endothelial dysfunction GI Decreased effectiveness of immune system Deficiencies in growth & development Negative impact on performance

Amenorrhea in Athletes Presumed to be a functional hypothalamic amenorrhea Bone mineral density decreases with increasing # of missed cycles Risk of stress fracture increases 2 -4 x Identify early for best chance of reducing fracture risk – bone loss greatest in the first year

Amenorrhea in Athletes Exercise in and of itself does not induce functional hypothalmic amenorrhea Rather, exercise may contribute to sustained low energy availability in the presence of inadequate nutritional intake Newest research suggests possible genetic component Heterozygous mutations associated with hypothalamic hypogonadism Mutations to the following genes were found: fibroblast growth factor receptor-1, the Kallmann syndrome 1 sequence, prokineticin receptor 2, and the Gn. RH receptor. Caronia LM, Martin C, Welt CK, et al. A genetic basis for functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(3): 215– 25.

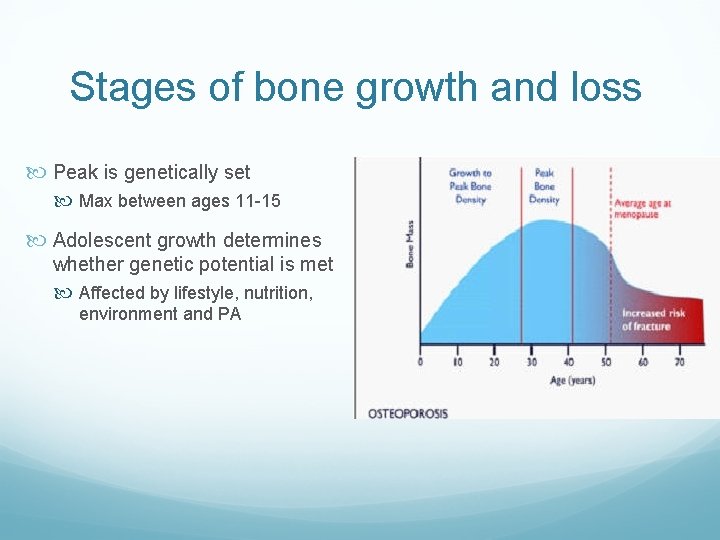

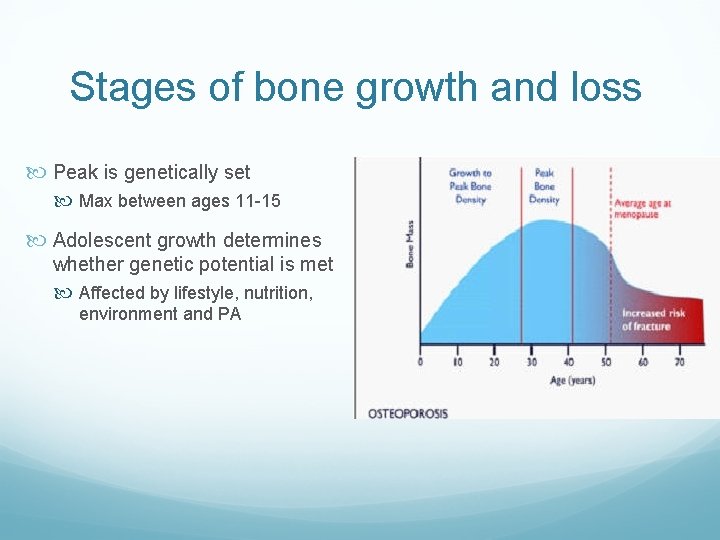

Stages of bone growth and loss Peak is genetically set Max between ages 11 -15 Adolescent growth determines whether genetic potential is met Affected by lifestyle, nutrition, environment and PA

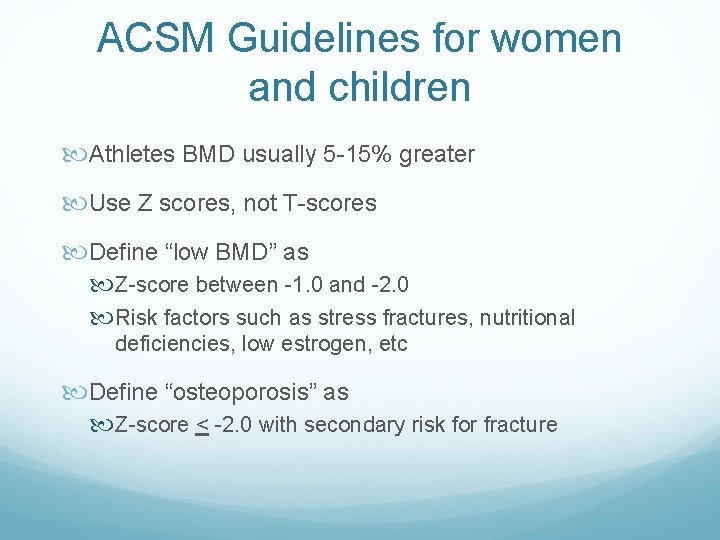

ACSM Guidelines for women and children Athletes BMD usually 5 -15% greater Use Z scores, not T-scores Define “low BMD” as Z-score between -1. 0 and -2. 0 Risk factors such as stress fractures, nutritional deficiencies, low estrogen, etc Define “osteoporosis” as Z-score < -2. 0 with secondary risk for fracture

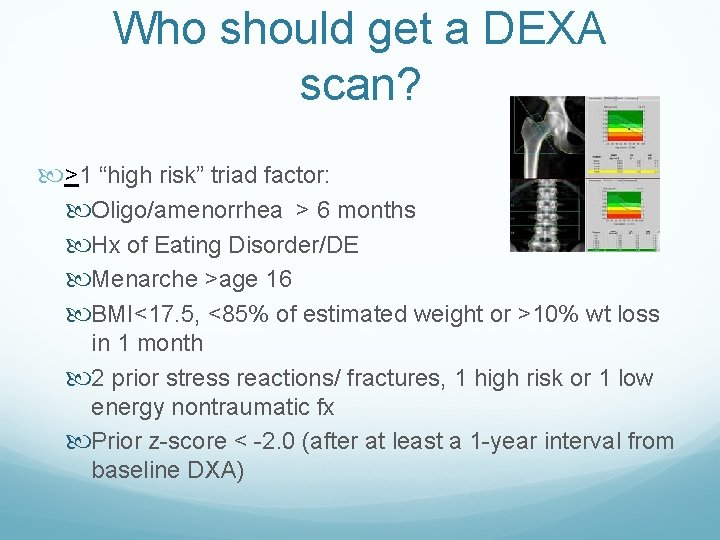

Who should get a DEXA scan? >1 “high risk” triad factor: Oligo/amenorrhea > 6 months Hx of Eating Disorder/DE Menarche >age 16 BMI<17. 5, <85% of estimated weight or >10% wt loss in 1 month 2 prior stress reactions/ fractures, 1 high risk or 1 low energy nontraumatic fx Prior z-score < -2. 0 (after at least a 1 -year interval from baseline DXA)

Who should get a DEXA? >2 “moderate” risk factors Currently experiencing or history of DE for 6 months or longer BMI between 17. 5 and 18. 5, 85 -90% estimated weight, or recent weight loss of 5% to 10% in 1 month Menarche between 15 and 16 years of age Currently experiencing or history of six to eight menses over 12 months One prior stress reaction/fracture Prior z-score between 1. 0 and 2. 0 (after at least a 1 -year interval from baseline DXA)

Screening and Diagnosis 2014 Triad Coalition Consensus statement provides algorithm for screening Screen during PPE, annual exam, injury visits or recurrent illness visits Recognize risk even if only one component exists Screen for all components Screen for high risk behaviors/warning signs Other brief evaluation tools: Brief ED in Athletes Questionnaire (BEDA-Q) LEAF-Q (Low Energy Availability in Females Questionnaire), which has been shown to predict overall Triad risk independent of whether DE is present

Treatment Goals Increase EA Increase intake/decrease activity Restore menstrual cycles Average time is 11 months Need EA > 30 kcal/kg FFM per day Increase BMD Weight gain essential, EA > 45 kcal/day Maximize bone nutrients (Ca, Vit D) Some irreversible loss

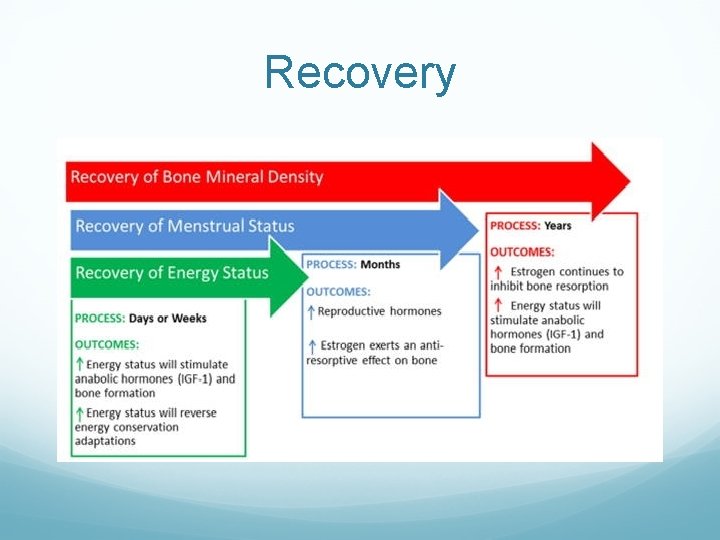

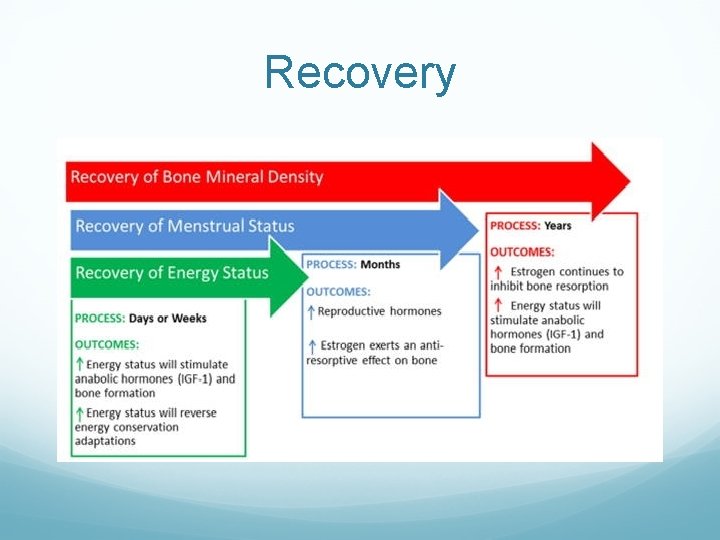

Recovery

Pharmacologic Considerations Calcium (1000 -1500 mg) Vit D (400 -800 IU) OCPs – Restoration of menses by OCP does not restore metabolic bone function. Consider use in those > 16 yr olds with decreasing BMD despite adequate diet/weight Anti-depressants NO bisphonates!

Treatment Pearls • • Multidisciplinary approach Increase calories by ~300 kcal/day Decrease training by one day/week Determine minimum criteria to compete/practice • Contracts?

Scenario #2 33 y/o female patient of yours comes to you with concerns regarding increasing issues with urinary incontinence with her workouts. She is otherwise healthy What do you want to know?

Scenario #2 Additional history: Former collegiate gymnast Took time off of exercise with birth of her 2 children Now runs ~20 miles a week and strength trains Having issues while running, sometimes with laughing/coughing/sneezing Had some similar sx in college only with gymnastics 2 vaginal deliveries No complications or significant tears Children are 5 & 2 years old – each ~7 lbs at birth

Urinary Incontinence Stress incontinence Urge incontinence Mixed incontinence Stress is the most common type Described as the involuntary loss of urine on effort or physical exertion

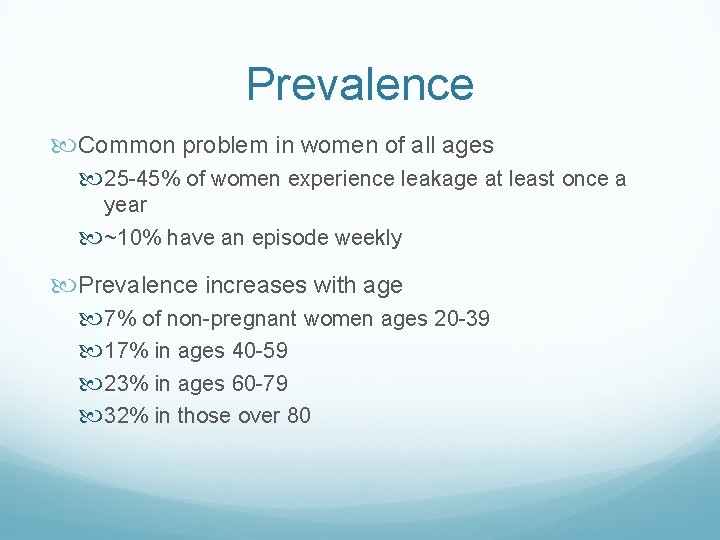

Prevalence Common problem in women of all ages 25 -45% of women experience leakage at least once a year ~10% have an episode weekly Prevalence increases with age 7% of non-pregnant women ages 20 -39 17% in ages 40 -59 23% in ages 60 -79 32% in those over 80

Prevalence Increased rates with pregnancy – 30 -60% Postpartum period range = 6 -35% High-impact sport athletes have highest rates Both feet off the ground at same time Repeated abrupt increases in intra-abdominal pressure Jumping is most likely to provoke Grossly underreported Estimated that only 5 -50% of cases are reported and/or addressed

Risk factors Age Functional impairment Parity High-impact activities Obesity Estrogen deficiency Diabetes Prior genitourinary surgery Stroke Medications: Smoking Depression Chronic constipation Psychotropics ACE inhibitors Diuretics

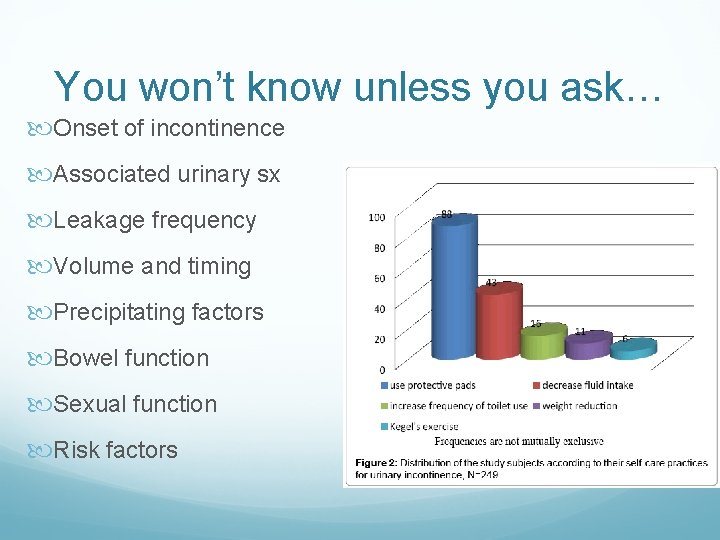

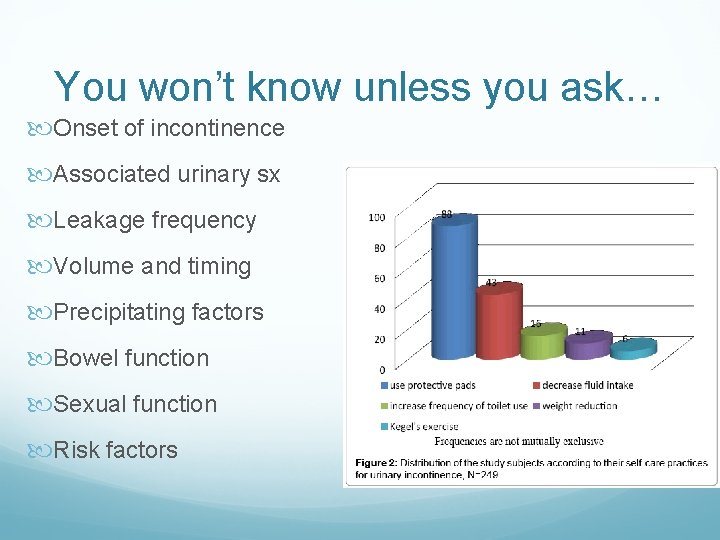

You won’t know unless you ask… Onset of incontinence Associated urinary sx Leakage frequency Volume and timing Precipitating factors Bowel function Sexual function Risk factors

Exam findings CV exam for signs of volume overload Neurological exam Genital exam Atrophy Inflammation Pelvic mass Pelvic floor weakness (cystocele, rectocele and enterocele) Urethral hypermobiilty Sphincter tone Pelvic floor muscle function

Incontinence and exercise Active females may only leak with exercise Can lead to avoidance of exercise Physical and psychological morbidity ensues ~30% of exercising women will experience urine leak Higher rates in our elite female athletes 28 -80% in gymnasts and dancers More often in training than competition (95. 2 % vs 51. 2%) Possibly due to higher catecholamine levels in competition acting on urethral α-receptors Thyssen HH, Clevin L, Olesen S, et al. Urinary incontinence in elite female athletes and dancers. Int Urogynecol J 2002; 13: 15– 17.

Pathophysiology Two hypotheses exist on how strenuous exercise affects the pelvic floor Physical activity may strengthen the pelvic floor muscles Physical activity may overload and weaken the pelvic floor Athletes report more sx at end of training sessions suggesting perhaps a muscle endurance issue Conversely, studies have verified increased pelvic floor muscle strength and diameter in athletes Mixed pictures also exist between the two

Treatment Address contributing factors Atrophy Modifiable risks – smoking, caffeine, alcohol, bowels Limit excessive fluid intake prior to exercise Void shortly before exercise Tampon use has been shown to decrease sx in stress incontinence Bladder training better for urge incontinence

Treatment Medications α-Adrenergic agonists, imiprimine, clebuterol, duloxetine, estrogen Haven’t been studied in exercise-induced incontinence Use caution with collegiate and olympic athletes due to banned substance list and α-Adrenergic agonists Anti-cholinergics are also dangerous in athletes due to increased risk of heat stroke

Treatment Pelvic floor muscle training for prevention and treatment ~30% of women can’t accurately contract the pelvic floor muscles correctly even after instruction Use caution as some women are actually hypertonic at baseline Biofeedback helps 56 -70% subjective improvement in sx reported Surgery for anatomical issues – not usually indicated in cases isolated to exercise Hay-Smith E, Bø K, Berghmans L, et al. Pelvic floor muscle training fur urinary incontinence in women. Available in The Cochrane Library [database on disk and CD ROM]. Updated quarterly. The Cochrane Collaboration; issue 3. Oxford: Update Software, 2001

Long term prognosis Conflicting data Studies on former Norwegian Olympic athletes did not find a higher prevalence of urinary incontinence later in life If the athlete had a h/o an eating disorder, their risk was significantly higher than for healthy athletes Stress (49. 5%) and urge (20%) vs 38. 8 and 15% Urinary incontinence early in life however was a strong predictor of later urinary incontinence in other studies

Scenario #3 A 26 year old elite level olympic distance triathlete presents to you for advice on maintaining her training now that she has become pregnant. What literature exists in regards to elite level exercise during pregnancy?

Elite exercise in pregnancy Limited data Definition of “elite” varies The ACOG guidelines for exercise in pregnancy state that “it is safe and reasonable for pregnant women who are already participating in vigorous-intensity aerobic activity to continue to be highly active during pregnancy, in conjunction with advice from their care providers. ” ACOG committee opinion No. 650: physical activity and exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol 2015; 126(6): e 135– 42.

The elite pregnant athlete A reasonable definition is an athlete who trains year round at a high level. Training is likely to be at least 5 days per week, averaging close to 2 hours per day and meet or exceed 6 metabolic equivalents level used to describe vigorous physical activity Pivarnik JM, Szymanski LM, Conway MR. The elite athlete and strenuous exercise in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2016; 59(3): 613– 9.

Preconception counseling Fertile period overlaps with peak performance for many Need to address any energy availability issues early Timing is a challenge Elite athletes with uncomplicated pregnancies should be reassured that they can continue exercising Some adjustments in intensity and activity may be required. If athletes are able to continue exercising at a moderate level throughout gestation they can expect their maximal aerobic capacity (VO 2 max) after childbirth to be similar to their pre-pregnancy levels Goal is to maintain, not improve, performance Bø K , Artal R , Barakat R , et al. Exercise and pregnancy in recreational and elite athletes: 2016 evidence summary from the IOC expert group meeting, Lausanne. Part 1 -exercise in women planning pregnancy and those who are pregnant. Br J Sports Med 2016; 50: 571– 89

Exercise in the elite athlete No documented increased risk of injury Need to monitor for appropriate weight gain/nutrition Avoid sports with a high probability of blunt trauma after 16– 20 wk of gestation Full contact Olympic sports such as wrestling, boxing, judo, taekwondo, rugby and ice hockey should be avoided throughout gestation, although non-contact training may be continued.

Effect on the fetus Six Olympic-level pregnant women were studied at 23 -29 weeks of gestation on a treadmill exercise activity Exercised at approximately 60% to 90% of maximal oxygen consumption. Fetal heart rate was within the normal range as long as the mother exercised less than 90% of maximal maternal heart rate. In some instances when maternal heart rate exceeded 90% of maximal, there was a simultaneous reduction in uterine volume blood flow to less than 50% of the initial value and fetal heart rate decelerations. All fetuses still did well. It was concluded that exercise at less than 90% of maximal maternal heart rate may be regarded as a safety zone for elite athletes. Salvesen KA, Hem E, Sundgot-Borgen J. Fetal wellbeing may be compromised during strenuous exercise among pregnant elite athletes. Br J Sports Med 2012; 46(4): 279– 83.

Return to exercise postpartum Individualize Return to participation Return to sport Return to performance Ardern CL , Glasgow P , Schneiders A , et al. 2016 Consensus statement on return to sport from the First World Congress in Sports Physical Therapy, Bern. Br J Sports Med 2016; 50: 853– 64

Take home points… Energy availability deficits need to be recognized to help prevent female athlete triad issues Exercise associated incontinence is common and needs to be addressed Elite athletes can maintain training while pregnant More research is needed