Soviet film criticism and the Cinema of moral

- Slides: 23

Soviet film criticism and the «Cinema of moral anxiety» : ideas, discourses, contexts СОВЕТСКАЯ КИНОКРИТИКА И «КИНО МОРАЛЬНОГО БЕСПОКОЙСТВА» (KINO MORALNEGO NIEPOKOJU): ИДЕИ, ДИСКУРСЫ, КОНТЕКСТЫ Svetlana Makagon

Object and parts The concepts of the term Kino moralnego niepokoju The main features of the Soviet-Polish film process Analysis of the pieces from Soviet film magazines 1975 -1989’s

The term "Kino moralnego niepokoju“ was first used in 1979 at the national film festival in Gdansk The author of the term was the critic and director Janusz Kijowski The stable expression KMB appeared in Soviet criticism only in 1989 The term unites films of the Polish cinema of 1975 -1981, the main marker of which is the bringing to the fore of the narrative actual social problems Kinopolonists contrast KMB films with official art, in contains symbols of dissatisfaction with what is happening in the country The KMB film is characterized by moral clashes between regime employees with young characters, who reveals his denying the socialist ideology Among the proposed alternatives the designation of cinema of this period, we can reveal "cinema of social anxiety", "cinema of authentic spirit", "cinema of distrust“ (‘moral’ seemed excessively metaphorically)

The context of Polish cinema industry 7080’s In the 1970 s one of the leaders of Poland first Secretary of the Polish United workers‘ was E. Gierek. Researchers of this period associate his personality with the ‘propaganda of success’. However, by the second half of the 70 s, the situation had worsened again. Stagnation also affects cultural life, and the government is gradually abandoning propaganda and arguments in support of the official socialist ideology Creative professions are moving to underground ones, and cinema is becoming the vanguard of political protest and occupies the place of the most important link of social communication As one of the sources of cultural transfer of the late socialism era, we can single out the ‘Kvant film club’ created by students of the Warsaw Polytechnic University, where world famous directors were invited (from M. Antonioni to N. Mikhalkov). In the autumn of 1976, Kvant hosted a seminar on ‘Modern Soviet cinema in the light of Lenin's concept of culture’ The meetings of the Warsaw film club were joined by the most iconic directors, actors, scriptwriters and critics from the USSR. It was also a common practice for future Directors to choose KMB among other figures of the creative intelligentsia of Soviet universities (mainly Moscow and Leningrad) for higher education, after which they absorbed Soviet ideas and implemented them at home. One such example was the film Director E. Goffman, who graduated from VGIK in 1955, and Zanussi holds the title of doctor at the same universities Festivals, non-commercial film screenings, and film clubs, including student ones, played an important role in socialist culture. For example, Soviet films and actors often received awards at the national film festival in Gdansk, and Polish films-at the Moscow international

The context of Polish cinema industry 7080’s by 1981, the state's attitude towards Polish cinematographers had undergone significant changes. In a document dated January 12, 1981 ‘about the stay in the USSR of the Secretary of the Polish Union of cinematographers Andrzej Wajda and his hostile views’, it was reported about illegal actions during the stay of A. Wajda: ‘it is established that A. During his stay in the USSR, Vajda attempted to collect information about people from among the creative intelligentsia of our country who share to some extent the positions of the ‘free trade unions’ Judgments about the need to abolish censorship in Poland, about the desire to distinguish between party politics and creativity: ‘. . . we want art and culture to have nothing to do with the party. And we will achieve this and calls for the Soviet intelligentsia to ‘strive for democratic freedoms’ Chairman of the state Committee of the USSR at a meeting with the Polish director, stated that ‘the tendency to weaken the role of the state in cinema can have a detrimental effect on the fate of Polish cinema’, and ‘Polish cinematographers could more actively help the party and the state to get out of the current political crisis faster’ The crisis situation in the Soviet film industry and ideological control, which sought to standardize the film repertoire, provoked genre searches and a focus on socio-cultural problems. Compounded by the decline in film attendance and falling profits, the turn of the socialist film industry towards ‘mass commercial’ films, with all its continued

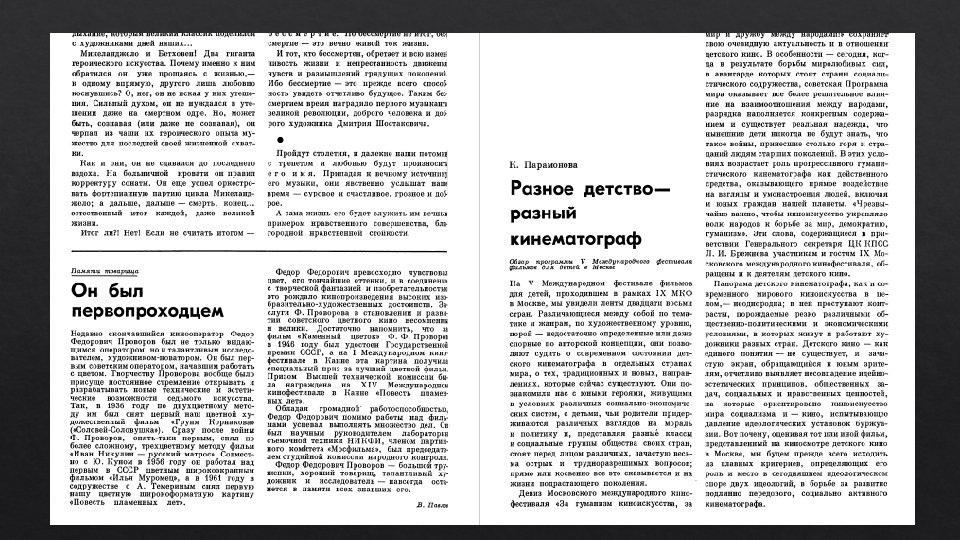

Critic. 1976 Pieces on KMB in Soviet periodicals are divided into three main genres: notes in the digest of new foreign films released per paragraph, interviews and materials with KMB Directors, and reports from festivals. In the 1976 article ‘The script as a model of social reality’ (Art of Cinema) in the section of theory of cinema, it is said that modern society needs sharp, exciting films about the reality of socialism. In March of the same year, in the section ‘abroad’, part of a rather politically neutral thematic article about foreign films of education was devoted to the film ‘The end of the holidays’ (1974), approving the way Polish filmmakers solve the ‘problems of civic education of teenagers’.

Critic. 1977 The anti-fascist theme in Polish cinema was very positively evaluated – in the September issue, reviewers write about the ‘huge interest’ in Flerkovsky's film ‘The Threat’, and the first issue of next year, an entire article on several pages will be devoted to this problem in the cinema of the people's Republic of Poland Reviews of Polish-Soviet events, such as the Days of Soviet cinema and educational meetings of Soviet Directors with participants of the Polish film club ‘Kvant’ or the conference of film critics ‘Screen of the world of socialism’, have also appeared on the pages of Soviet film magazines Figures that indicate the popularity of Soviet films in Poland with reference to journalists of the Polish publication ‘Film’, recognizing the success of ‘the result of measures to promote Soviet cinema in Poland’.

Kinofestival in Gdansk (1977) Special attention is paid to the Gdansk film festival and the number of films released in previous years – as many as 29 in 1974, and it is particularly important that 19 of them addressed ‘modern social issues and morality, and human morality’, and in the 77 th there is a joyful growth in the release plan of film productions and the success of the new principle of thematic planning The article ends with a declaration about the leading role of the movie in the dissemination of ideas and values among the masses, but also about hope in a brighter future and work together ‘to enrich the experience and development of the socialist cinema’ and ‘new General-socialist multinational audience’ In relation to the recently released film ‘Protective colors’ of Zanussi, Soviet observers focus on the location where the shooting took place, and allow themselves a small controversy with the Polish critic Tadeusz Sobolewski, who called the film ‘a comedy about a riot’. Soviet film critics on the basis of this film call to think about the ‘moral aspects of scientific activity’,

Critic. 1979 October 1979, the article ‘Zigzags of the festival marathon’, among other pictures of socialist countries that won awards at ‘Belgrade-79’, mentions the film ‘Man of marble’ by A. Vaida, which explores ‘serious and ambiguous phenomena of the initial stage of building socialism in Poland’. But the mention of this work in the press itself is surprising – in the Soviet Union, Vida not only did not get into the rolling repertoire, but was banned for a long time – it was again ‘allowed’ only in the late 1980 s.

Critic. 1980 -1981 I. Rubanova in May published her own article about the anti-fascist theme in Polish cinema, which assesses the types of heroism of film characters, and their background. The critic explains the interest in Polish cinema in the world art world by referring to anti-fascist themes in the 40 s and 50 s (Vajda is also mentioned in this context, being already banned, but only with reference to his early works) In August of the same year, ‘Art of Cinema’ published a large interview with the Polish Director Jerzy Kavalerovich about the old problem – art on television wins in mass, but loses in quality, about the professionalism of Vajda, about the Italian and French ‘new wave’. The specialized press is still silent about KMB cinema In the September publication following the last Krakow-81 festival, we observe notes from a conversation between the Soviet critic I. Itskov and an unnamed guest of the festival about the role of that in Solidarity, who ‘in secret’ told the film critic that this is not really an Association of industrial workers, but a movement against the party and socialism, and also reveals the future plans and strategy of Solidarity. The interlocutor informs that Solidarity is closely connected with the world of cinematography and Vajda himself Already in the next issue, there was a reaction to Vajda's anti-socialist work and its success in Cannes in the article ‘Andrzej Vajda: what's next? ’, which begins with a quote from the French newspaper ‘Figaro’: ‘Iron man is the sharpest accusation of Soviet imperialism that has ever been thrown, and its further ideas resemble an investigation to prove the guilt of a cultural criminal’.

Critic. 1989 In the works of K. Zanussi, late Soviet cultural figures clearly did not see as much danger as in the films of A. Vajda, but the word on the pages of ‘Art of Cinema’, however, was given to him only in February 1989. Film columnist T. N. Eliseeva notes That for K. Zanussi ‘the modern world is a territory of moral conflicts and ethical dilemmas’ In February one of the main Soviet film polonists, I. Rubanova, explains the situation with negative criticism of Vajda: ‘the name of Andrzej Vajda, excommunicated from the screen and forbidden to print, has existed for us in the position of a myth for the last ten years. Two versions of the legend were most widely used: the popular positive version and the fearsome official version. According to the first, the Creator of ‘Ashes and diamonds’ is a historical tragedian, a poet of a generation that took on the burden of war and was crushed by this unaffordable burden. Version two: demagogue, instigator, opportunist, who exchanged his poetic talent for flat politicking’.

Conclusion Soviet film magazines are also becoming a platform for Polish critics and directors, cultural figures – guests of the USSR, but only in relation to issues that are beneficial for the image of the socialist community. The tools for representing the KMB to the Soviet audience were silencing and articles in an accusatory tone, which is not just an accident, but editorial policy, evidence of which we see in the articles of 89 and the recently published memoirs of film polonists. The influence of Soviet-Polish relations on the content of journalistic materials, a systematic approach to covering news from the film process of socialist countries, and the control of the party's bodies of published materials. On the example of the materials considered, the following functions of Soviet film criticism were identified: normative, propaganda, mobilization, consolidating, while for specific publications and the representation of the USSR in the international arena, it was an inculturation and reputational history.