Song development and its importance in male and

- Slides: 31

Song development and its importance in male and female zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata). Jodie Miller Phuoc Ho

u Two distinct sub-species of zebra finch • Taeniopygia guttata • Taeniopygia gutatta castanotis u medium sized finch • 10 -11 cm long • weighing about 12 grams

u male and female • head and back are grey • the tail has black and white bars social creatures u live year round in flocks of 50 and up to 100 or more birds u produce as many as 5 to 7 eggs u

u The young • undergo a rapid development • reaching nutritional independence at about 35 days • sexually mature at 3 months u Monogamous and sexually dimorphic

v Song system of zebra finches and other song birds v two pathways v. Efferent pathway v. Anterior forebrain pathway

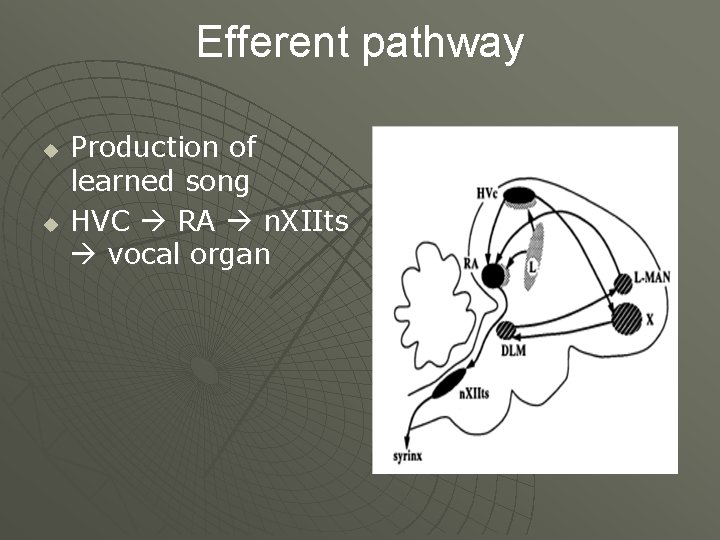

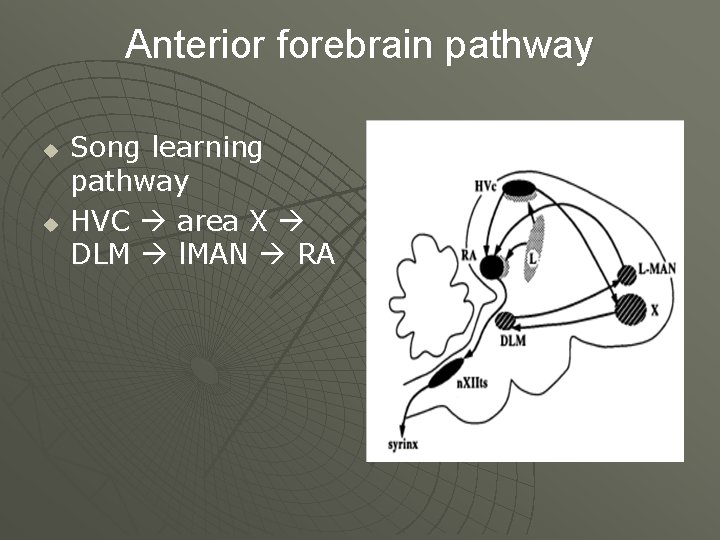

Song learning and production regions u u u HVC- caudal nucleus of the ventral hyperstriatum RA- robust nucleus of the archistriatum. DLM- medial nucleus of the dorsolateral thalamus l. MAN- lateral magnocellualr nucleus of the anterior neostriatum. Area X- lobus parolfactorius n. XIIts- tracheosyringeal portion of the hypoglossal nucleus

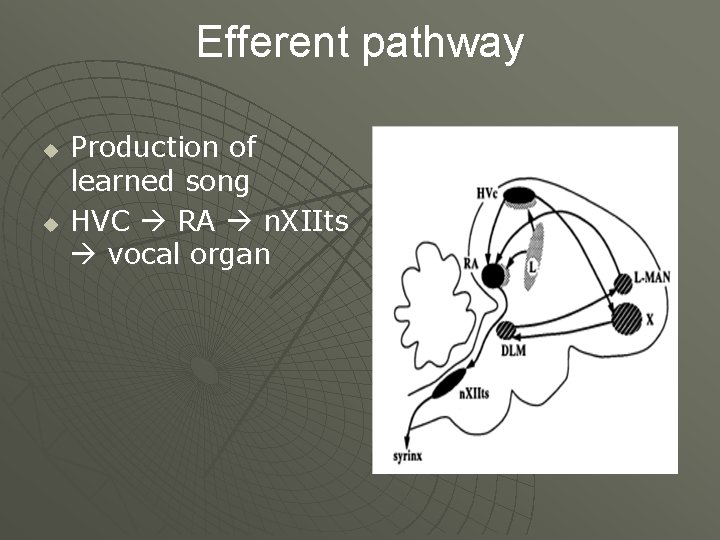

Efferent pathway u u Production of learned song HVC RA n. XIIts vocal organ

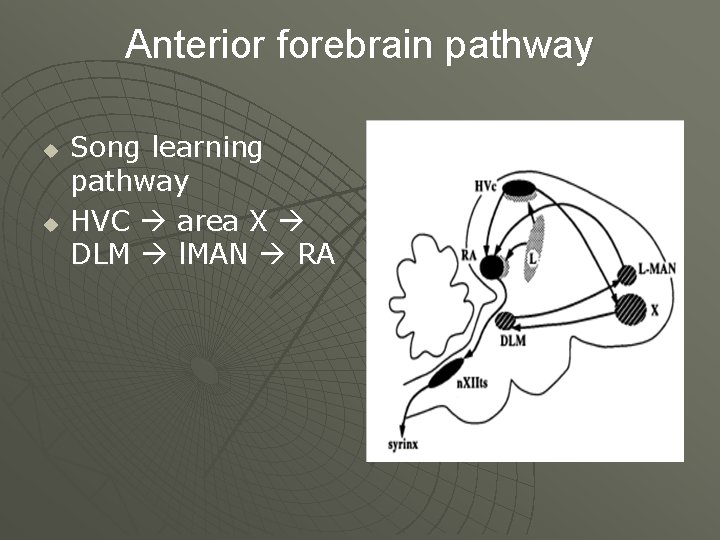

Anterior forebrain pathway u u Song learning pathway HVC area X DLM l. MAN RA

Volume sizes u l. MAN, HVC, RA, area X

l. MAN u u initiation and early development of song learning males • 10 -20 days - increased ~72% • 20 -40 days – decrease ~ 48% • > 40 days – no change

u Females • Exhibit same patterns • Males l. MAN volume twice that of females at 10 days • 30 days - = l. MAN volume of males • > 30 days – decrease until adulthood

HVC u Males • Development until adulthood • 10 -30 days – increased ~ 71% • 30 – 40 days – further increased of 47% • 40 - 50 days – growth stop • 50 – 60 days – increased 39% • > 60 days – constant

u Females • 10 days – adulthood – no volume growth detected

RA volume similar during the first 20 days for males and females u Males u • 20 - 30 days – increase ~48% • Every 10 days – increase ~ 22% until normal value is reached

u Females • 20 – 30 days – decrease 23% • Continue to decrease until normal value is reached in adulthood

Area X Visible in males u Missing in females u Occurred at two period u • 20 days – increased ~ 84% • 40 days – further increased ~ 76%

What does it indicate? u Song learning consists of two phases • Memorizing song (sensory acquisition phase) • Reproducing song (sensorimotor learning phase) • Memorizing phase started first u Lasted up to 40 days • Reproducing phase started later u Lasted up to 60 days • phases partly overlapping

l. MAN u There is 10 days delay for females • Related to only memorizing song u u Important to differentiate songs Males early development related to both the memorizing and reproducing song

HVC & RA u Males • HVC increase in two time periods & increase continually in RA May related to memorizing phase started first u May related to reproducing phase started later u

u Females • Declined of HVC & RA Occurred before reproducing phase has started u Only memorizing phase occurred u

Song learning process Males -process takes place between 25 -90 days of age -plays a crucial role in mate selection, developing the species or population specific vocalization. -exposure of songs can be acquired through social learning between non-relatives but is usually done by the father -must learn before sexual maturation for repertories to be stable

Learning process con’t u Females • Learn preferences for males by the male’s songs. Trait is passed on to the nestlings. • vocalization developed independently from social learning because they do not sing. • Provides a natural control group where perception learning is not influenced by song production learning • Preferred songs like their father’s over an unfamiliar one.

Distance Call structure u u Male call • tonal component- made up of pure, sustained harmonic tones • Noise component- harsh, rapidly-modulated quality Female Call • Only tonal component- longer and lower pitched • Males, not females learn distance calls from father during first 40 days of life

Female Song preferences u u u Songs heard early in life influence which song advertised by males they will choose to mate with in adulthood Need adult song exposure in early development to develop normal song preference Reared with adult males=preferred normal quality songs Reared without adult males=preferred abnormal quality song Prefer fathers’ song over unfamiliar ones Experiments conducted

Stress effects on song structure Stress of song structure affects the attractiveness of the song. u Stressed males exhibited shorter, simpler songs u Nutrition stress effects u • brief period of under-nutrition affects the repertoire size (quantity of what is learned) and also the ability to copy local song material (the quality of what is learned).

Stress effects Con’t u Study conducted on stress effects. • The stressed males exhibited lower numbers of syllables and fewer different syllables in a phrase. Rate and frequency did not differ between two song types • Females showed a significant preference for non-stressed songs • Non-stressed males conducted a complex song. Complexity of a song may indicate that a male is older and therefore having a better territory.

Other effects on song quality u u The number of male siblings cause social inhibition of song imitation among each other Study conducted by Tchernichovski • Found that incomplete imitations are more common among early-hatched than among late -hatched siblings. • Young siblings were more likely to develop song first and imitate entirely their fathers song than the older siblings.

White noise effect u u Used chronic exposure to loud white noise Long-term exposure to continuous wn resulted in disruption of songs similar to that observed after deafening Recovery of pre-WN song patterns were limited after restoration of hearing. Suggested that an adult form of learning existed

References: u u u u u Akutagawa, A. & Koniski, M. 1994. Two separate areas of the brain differentially guide the development of a song control nucleus in the zebra finch. Proc. Nalt. Acad. Sci. USA, 91: 12413 -12417. Bottjer, S. W. , Glaessner, S. L. & Arnold, A. P. 1985. Ontogeny of brain nuclei controlling song learning and behavior in zebra finches. The Journal of Neuroscience , 5: 1556 -1562. Clayton, N. S. 1990. Assortative mating in zebra finch subspecies, Taeniopygia guttata and Taeniopygia guttata casranotis. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B, 330: 351 -370. Collins, S. A. 1999. Is female preference for male repertoires due to sensory bias? Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. , 266: 2309 -2314. Cynx, J. & Nottebohm, F. 1992. Role of gender, season, and familiarity in discrimination of conspecific song by zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 89: 1368 -1371. Lauay, C. , Gerlach, N. M. , Regan, E. A. & Devoogd, T. J. 2004. Female zebra finches reguire early song exposure to prefer highquality song as adults. Animals Behaviour, 267: 2553– 2558. Lundmark, C. 2003. Sexual selection of complex songs. Bio. Science, 53. Murray, N. D. , Runciman, D. & Zann, R. A. 2005. Geographic and temporal variation of the males zebra finch distance call. Journal of Ethology, 111: 367 -379. Nixdorf-Bergweiler, , B. E. 1996. Divergent and parallel development in volume sizes of Telencephalic song nuclei in male and female zebra finches. The Journal of Comparative Neurology , 375: 445 -456. Nowicki, S. , Searcy, W. A. , Peters, A. 2003. Brain development, song learning and mate choice in birds: a review and experimental test of the "nutritional stress hypothesis”. J. Comp. Physiol. 188: 1003 -1014. Riebel, K. 2000. Early exposure leads to repeatable preferences for male song in female zebra finches. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B, B, 267: 2553 -2558. Riebel, K. 2003. Developmental influences on auditory perception in female zebra finches-is there a sensitive phase for song preference learning? Animal Biology, 53: 73 -87. Riebel, K. , Smallegange, I. M. , Terpstra, N. J. & Bolhuis, J. J. 2002. Sexual equality in zebra finch song preference: evidence for dissociation between song recognition and production learning. The Royal Society, 269: 729 -733. Runciman, D. , Zann, R. A. & Murray, N. D. 2005. Geographic and temporal variation of the male zebra finch distance call. Ethology, 111: 367 -379. Spencer, K. A. , Buchanan, K. L. , Goldsmith, A. R. , & Catchpole, K. L. 2003. Songs as an honest signal of developmental stress in the zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata). Hormones and Behavior, 44: 132 -139. Spencer, K. A. , Wimpenny, J. H. , Buchanan, K. L. , Lovell, P. G. , Goldsmith, A. R. & Catchpole, K. L. 2005. Developmental stress affects the attractiveness of male song and female choice in the zebra finch ( Taeniopygia guttata). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. , 58: 423428. Tchernichovski, O. & Nottebohm, F. 1998. Social inhibition of song imitation among sibling male zebra finches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 95: 8951 -8956. Vleck, C. M. & Priedkalns, J. 1985. Reproduction in zebra finches: hormone levels and effect of dehydration. The Condor, 87: 37 -46. Zann, R. A. , Morton, S. R. , Jones, K. R. & Burley, N. T. 1995. The Timing of Breeding by Zebra Finches in Relation to Rainfall in Central Australia. Emu Austral Ornitholog, 95: 208 -222.

Bibliography: u u u u u Collins, S. A. 1999. Is female preference for male repertoires due to sensory bias? Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. , 266: 2309 -2314. Cynx, J. 2001. Effects of humidity on reproductive behavior in male and female zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata). Journal of Comparative Psycholog, 115: 196200. Cynx. J. 1993. Conspecific song perception in zebra finches ( Taeniopygia guttata). Journal of Comparative Psychology, 107: 395 -402. Houx, B. B. , Cate, C. T. , & Feuth, E. 2000. Variation in zebra finch song copying: an examination of the relationship with tutor song quality and pupil behavior. Behaviour, 137: 1377 -1389. Liu, W. , Gardner, T. J. & Nottebohm, F. 2004. Juvenile zebra finches can use multiple strategies to learn the same song. PNAS, 52: 18177 -18182 Riebel, K. & Smallegange, I. M. 2003. Does zebra finch ( Taeniopygia guttata) preference for the (familiar) father’s songs generalize to the songs of unfamiliar brothers? Journal of Comparative Psychology, 117: 61 -66. Slabbekoorn, H. & Smith, T. B. 2002. Bird song, ecology and speciation. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B, 357: 493 -503. Solis, M. M. , Brainard, M. S. , Hessler, N. A. , & Doupe, A. J. 2000. Song selectivity and sensorimotor signals in vocal learning and production. PNAS, 97: 11836 -11842. Williams, H. 2001. Choreography of song, dance and beak movement in the zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata). The Journal of Experimental Biology, 204: 3497 -3506.