Solar energy conversion mimicking natural photosynthesis Modeling the

![Conclusions for (i) [proton pumps] and (ii) [e- pumps] • Our study models the Conclusions for (i) [proton pumps] and (ii) [e- pumps] • Our study models the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/5eb13bb94f04af5874650fdf3814f897/image-4.jpg)

![A mimicry of natural photosynthesis l Moore’s group [Nature 385, 239 (1997)] extensively developed A mimicry of natural photosynthesis l Moore’s group [Nature 385, 239 (1997)] extensively developed](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/5eb13bb94f04af5874650fdf3814f897/image-12.jpg)

![Mimicking natural photosynthesis • Nishitani et al. [J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105, 7771 (1983)], Mimicking natural photosynthesis • Nishitani et al. [J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105, 7771 (1983)],](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/5eb13bb94f04af5874650fdf3814f897/image-58.jpg)

- Slides: 72

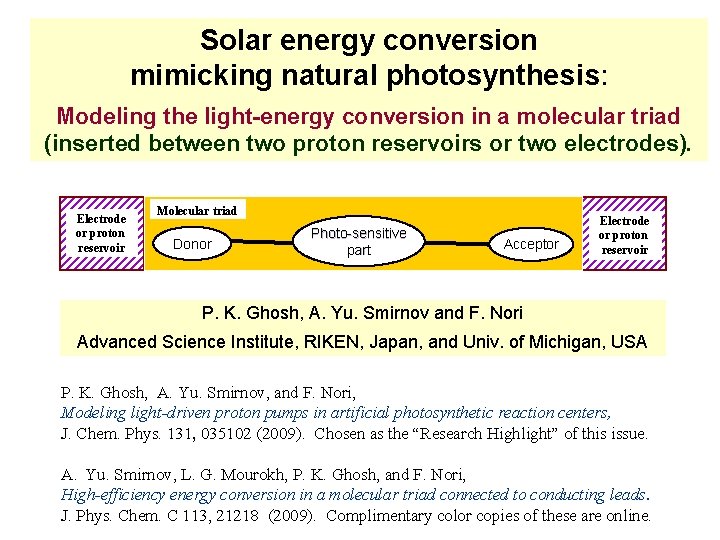

Solar energy conversion mimicking natural photosynthesis: Modeling the light-energy conversion in a molecular triad (inserted between two proton reservoirs or two electrodes). Electrode or proton reservoir Molecular triad Donor Photo-sensitive part Acceptor Electrode or proton reservoir P. K. Ghosh, A. Yu. Smirnov and F. Nori Advanced Science Institute, RIKEN, Japan, and Univ. of Michigan, USA P. K. Ghosh, A. Yu. Smirnov, and F. Nori, Modeling light-driven proton pumps in artificial photosynthetic reaction centers, J. Chem. Phys. 131, 035102 (2009). Chosen as the “Research Highlight” of this issue. A. Yu. Smirnov, L. G. Mourokh, P. K. Ghosh, and F. Nori, High-efficiency energy conversion in a molecular triad connected to conducting leads. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 21218 (2009). Complimentary color copies of these are online.

We looked into some published experiments, and we wrote the first models for these. Some differences regarding models: Molecular Dynamics (MD) can model dynamics ~ ps (up to ~ ms), while kinetic equations (which we use) can cover a far wider range: from ps to seconds. More importantly, MD solves classical equations, not quantum, and we are studying quantum transport of protons and electrons.

Summary of light-driven proton pumps l Our study is the only theoretical model for the quantitative study of light-driven protons pumps in a molecular triad. l Our results explain previous experimental findings on light-to -proton energy conversion in a molecular triad. l We compute several quantities and how they vary with various parameters (e. g. , light intensity, temperature, chemical potentials). l We have shown that, under resonant tunneling conditions, the power conversion efficiency increases drastically. This prediction could be useful for further experiments. 3

![Conclusions for i proton pumps and ii e pumps Our study models the Conclusions for (i) [proton pumps] and (ii) [e- pumps] • Our study models the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/5eb13bb94f04af5874650fdf3814f897/image-4.jpg)

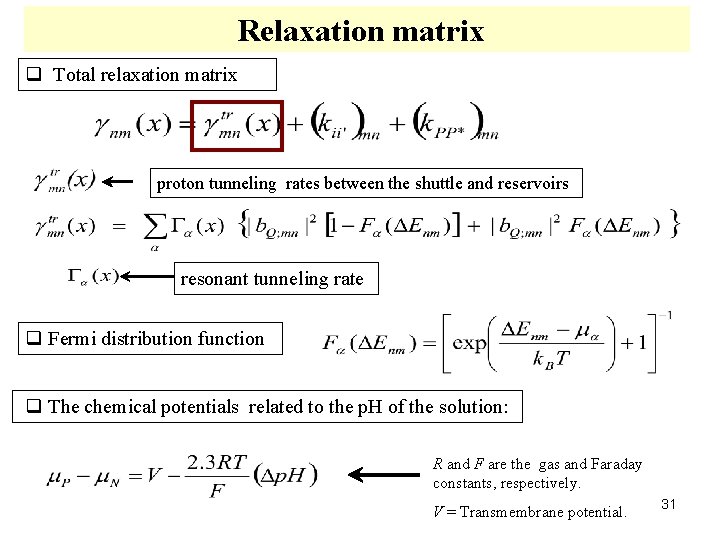

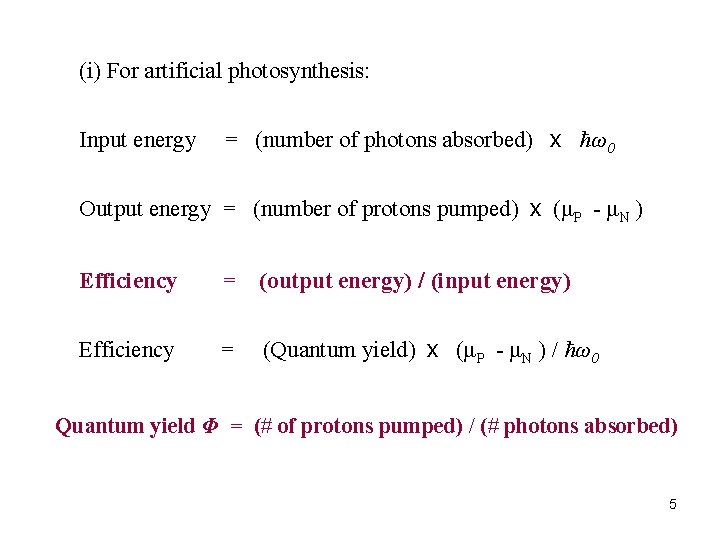

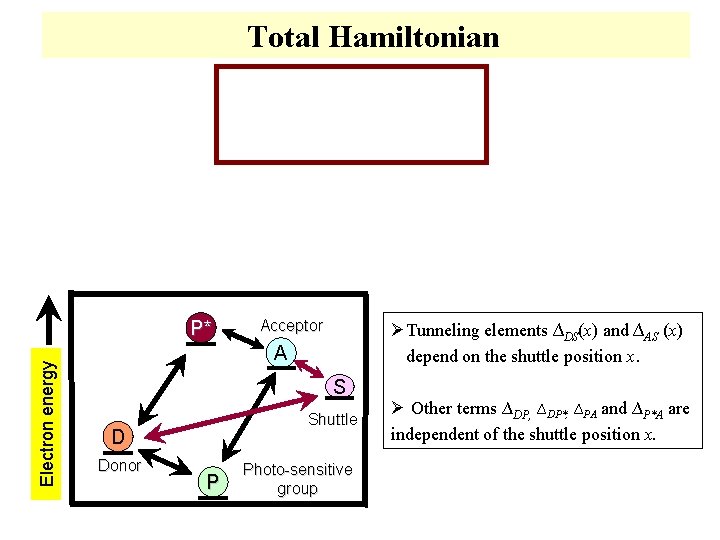

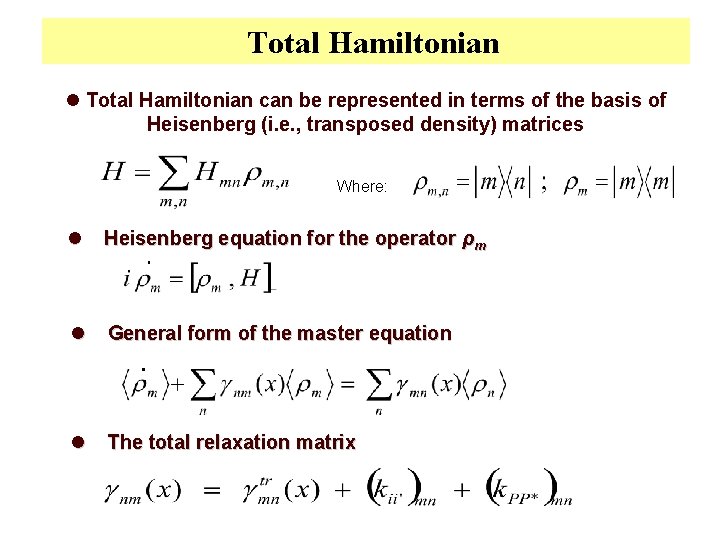

Conclusions for (i) [proton pumps] and (ii) [e- pumps] • Our study models the physics in artificial photosynthesis. • (i) The numerical solutions of the coupled master equations and Langevin equation allows predictions for the quantum yield and its dependence on the surrounding medium, intrinsic properties of the donor, acceptor, photo-sensitive group, etc. • (ii) We have also shown that, under resonant tunneling conditions and strong coupling of molecular triads with the electrodes, the (light-to-electricity) power conversion efficiency increases drastically. Thus, we have found optimal-efficiency conditions. • Our results could be useful for future experiments, e. g. , for choosing donors, acceptors and conducting electrodes or leads (on the basis of reorganization energies and reduction potentials) to achieve higher energy-conversion efficiency. 4

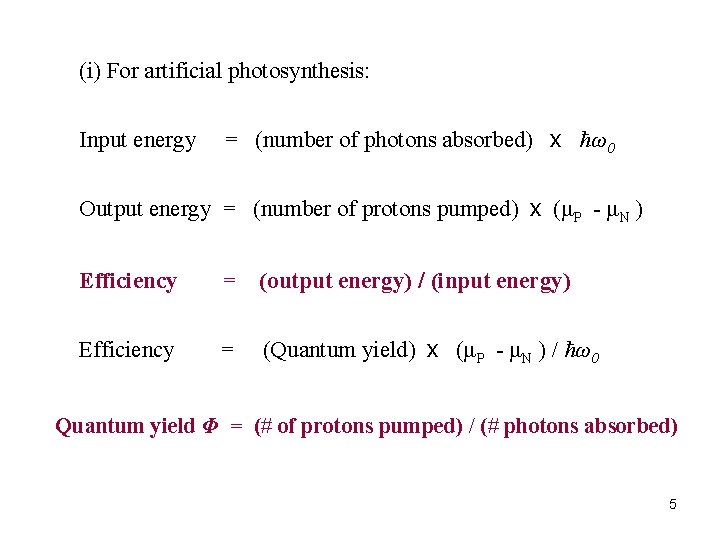

(i) For artificial photosynthesis: Input energy = (number of photons absorbed) x ћω0 Output energy = (number of protons pumped) x (μP - μN ) Efficiency = (output energy) / (input energy) Efficiency = (Quantum yield) x (μP - μN ) / ћω0 Quantum yield Φ = (# of protons pumped) / (# photons absorbed) 5

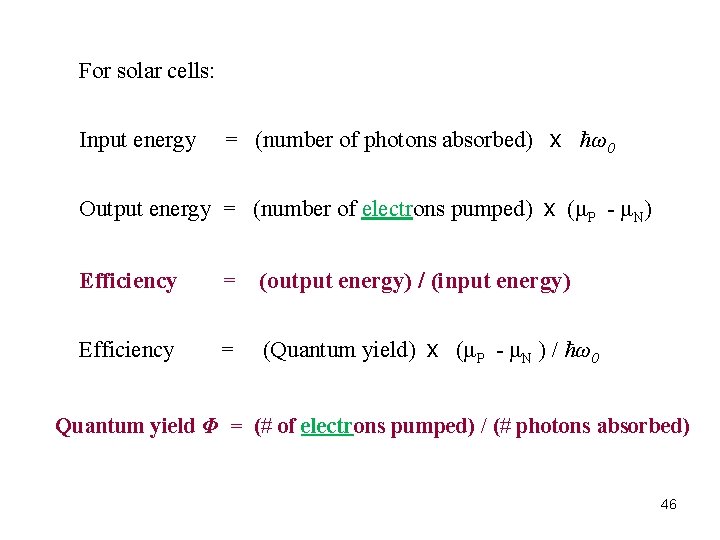

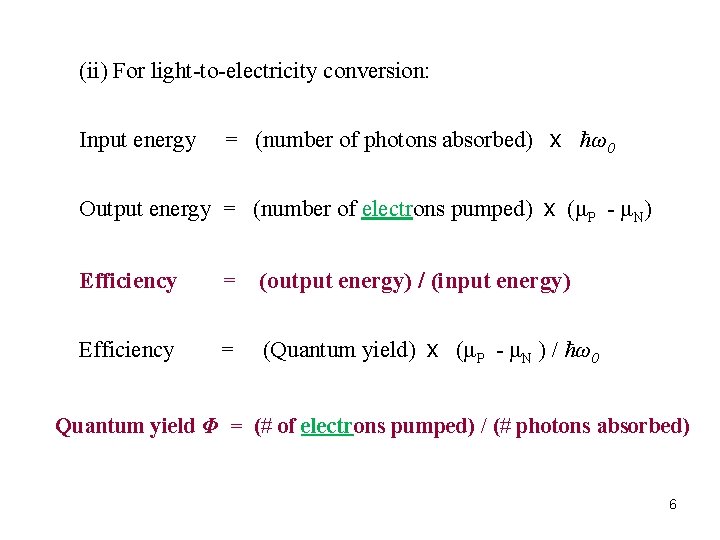

(ii) For light-to-electricity conversion: Input energy = (number of photons absorbed) x ћω0 Output energy = (number of electrons pumped) x (μP - μN) Efficiency = (output energy) / (input energy) Efficiency = (Quantum yield) x (μP - μN ) / ћω0 Quantum yield Φ = (# of electrons pumped) / (# photons absorbed) 6

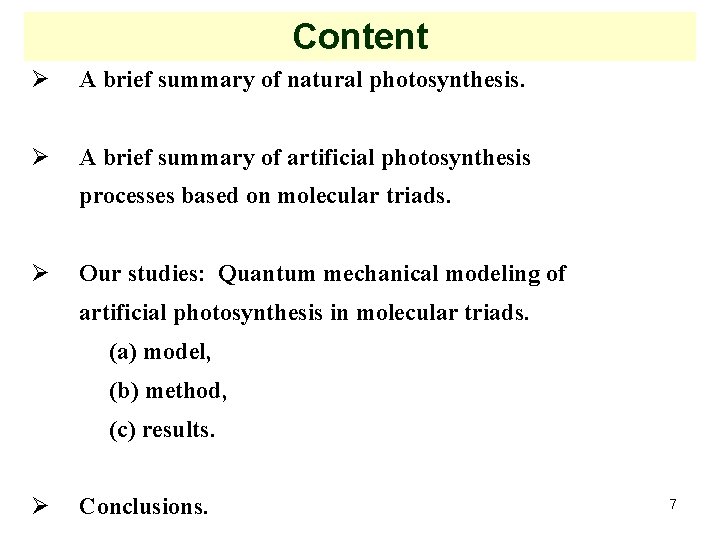

Content Ø A brief summary of natural photosynthesis. Ø A brief summary of artificial photosynthesis processes based on molecular triads. Ø Our studies: Quantum mechanical modeling of artificial photosynthesis in molecular triads. (a) model, (b) method, (c) results. Ø Conclusions. 7

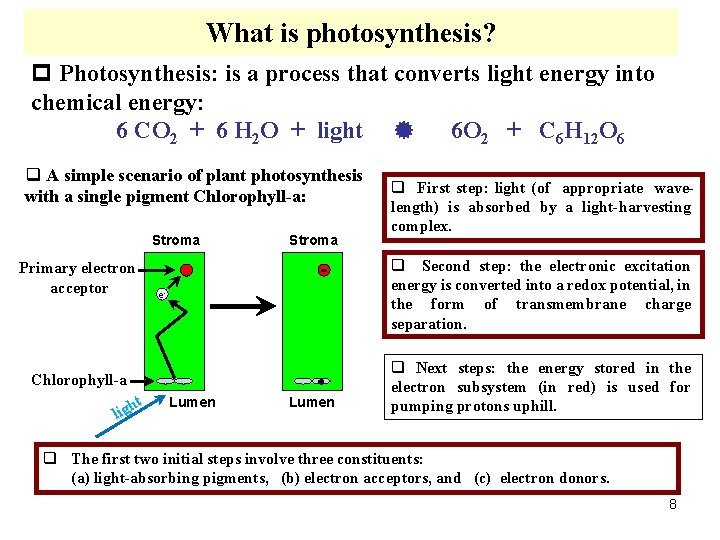

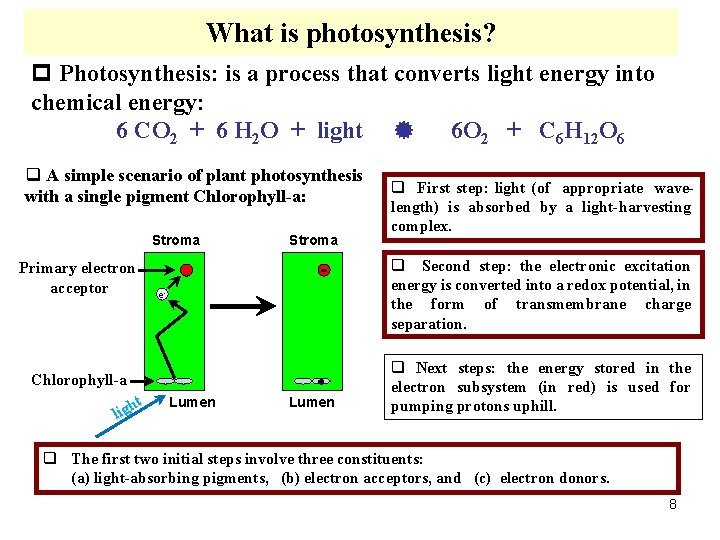

What is photosynthesis? p Photosynthesis: is a process that converts light energy into chemical energy: 6 CO 2 + 6 H 2 O + light 6 O 2 + C 6 H 12 O 6 q A simple scenario of plant photosynthesis with a single pigment Chlorophyll-a: Stroma Primary electron acceptor Stroma q Second step: the electronic excitation energy is converted into a redox potential, in the form of transmembrane charge separation. e- Chlorophyll-a ht lig q First step: light (of appropriate wavelength) is absorbed by a light-harvesting complex. Lumen q Next steps: the energy stored in the electron subsystem (in red) is used for pumping protons uphill. q The first two initial steps involve three constituents: (a) light-absorbing pigments, (b) electron acceptors, and (c) electron donors. 8

Some important characteristics of natural photosynthesis Ø The formation of a charge-separated state (using the energy of light) is a key strategy in natural photosynthetic reaction centers. Ø The charge-separated states are stable (with long lifetime, increasing quantum yield). Ø The (distant) charge-separated states are produced via multi-step electron transfer processes. 9

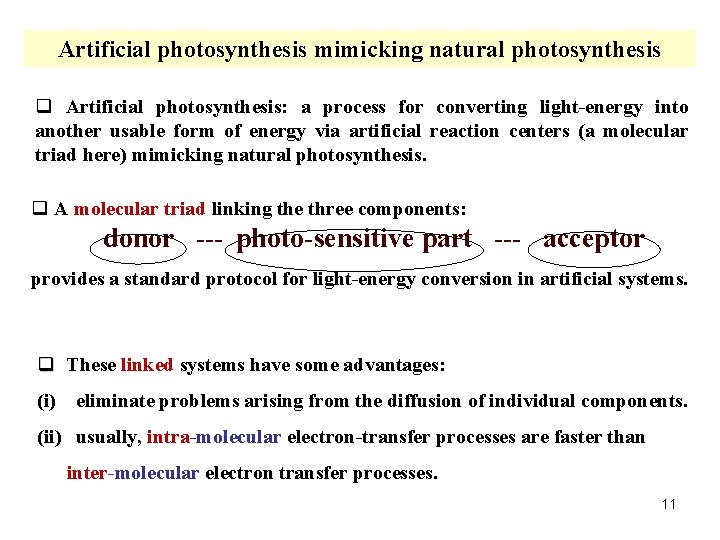

Some important characteristics of natural photosynthesis v In natural photosynthesis, a distant charge-separated state is produced via a multi-step electron transfer. q Why a distant charge-separated state ? A large separation of the ions (in an ion pair) suppresses energywasting charge-recombination processes. q Why the multi-step electron transfer processes? With increasing distance between the donor and the acceptor, the electron-transfer rate decreases, so multiple steps are needed for a distant charge-separation with a long lifetime (and a high quantum yield). 10

Artificial photosynthesis mimicking natural photosynthesis q Artificial photosynthesis: a process for converting light-energy into another usable form of energy via artificial reaction centers (a molecular triad here) mimicking natural photosynthesis. q A molecular triad linking the three components: donor --- photo-sensitive part --- acceptor provides a standard protocol for light-energy conversion in artificial systems. q These linked systems have some advantages: (i) eliminate problems arising from the diffusion of individual components. (ii) usually, intra-molecular electron-transfer processes are faster than inter-molecular electron transfer processes. 11

![A mimicry of natural photosynthesis l Moores group Nature 385 239 1997 extensively developed A mimicry of natural photosynthesis l Moore’s group [Nature 385, 239 (1997)] extensively developed](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/5eb13bb94f04af5874650fdf3814f897/image-12.jpg)

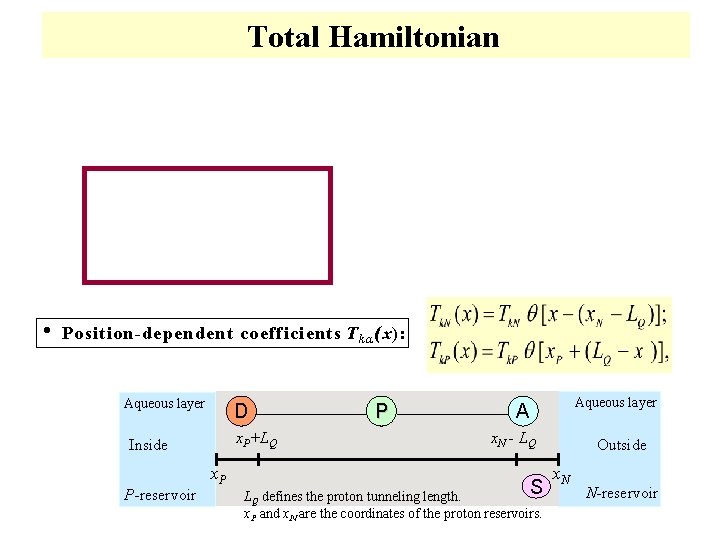

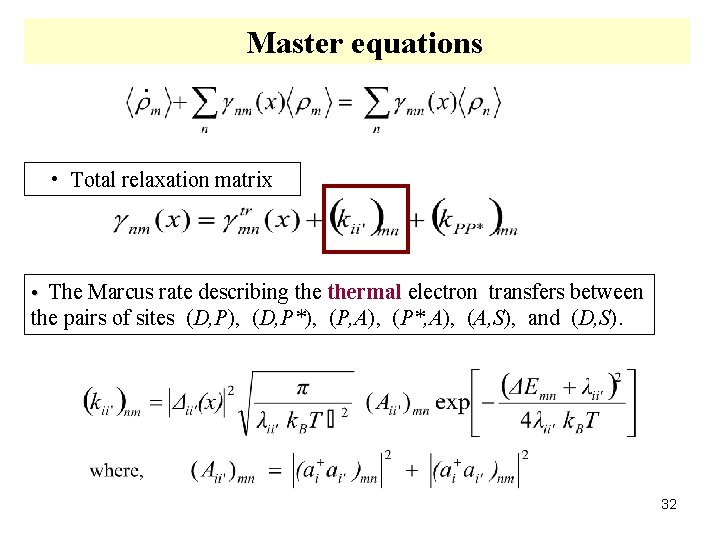

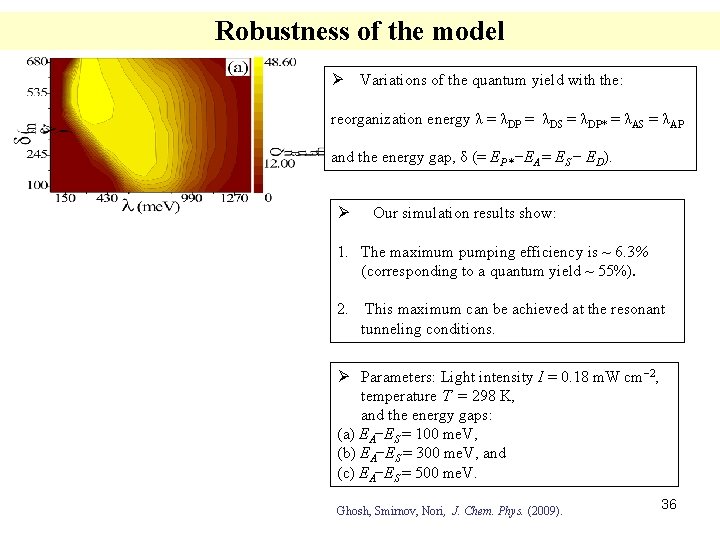

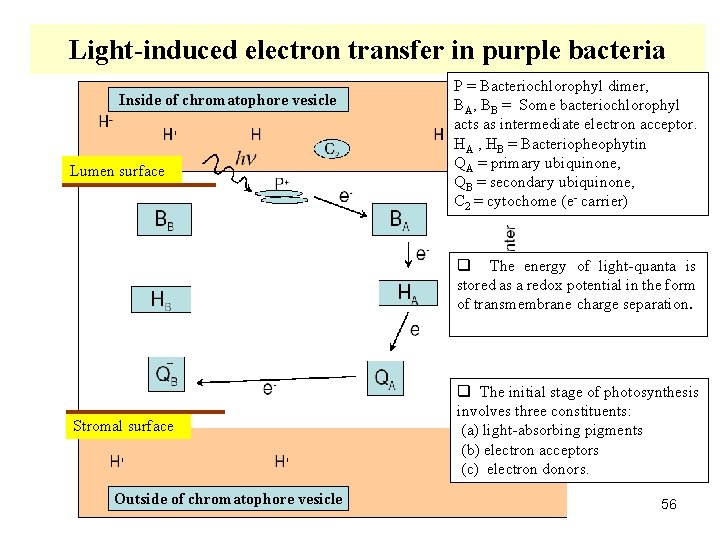

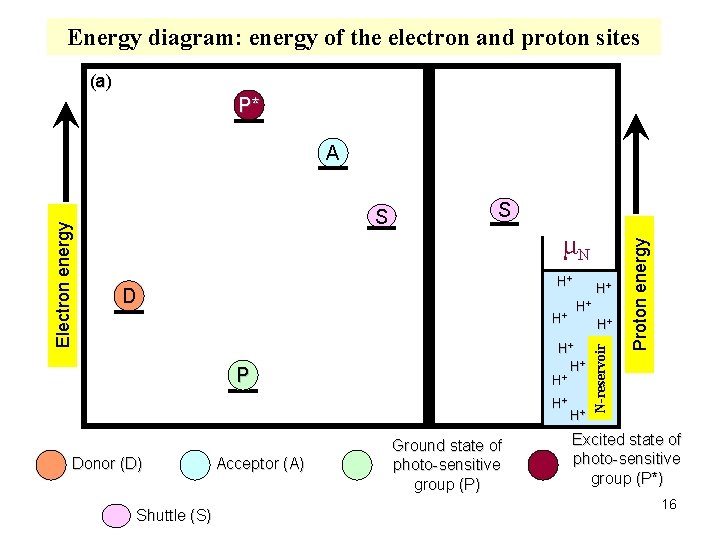

A mimicry of natural photosynthesis l Moore’s group [Nature 385, 239 (1997)] extensively developed donor-photosensitizer-acceptor type systems to study light-driven proton pumps in an a r t i f i c i a l p h o t o s y n t h e t i c s y s t e m. • Molecular triad QS = diphenylbenzoquinone Naphthoquion Carotenoid moiety (C) moiety (Q) Porphyrin moiety (P) Inside of liposome light-induced excitation of triad molecules generates charge-separated states. l The P* Q C l C P+ Q- C+ P Q- This triad molecule is incorporated into the bilayer of a liposome. freely diffusing quinone molecule alternates between oxidized and reduced form to ferry protons across the membrane. l The e ran b m me • Liposome: is a small artificially created sphere surrounded by a phospholipid bilayer membrane. 12

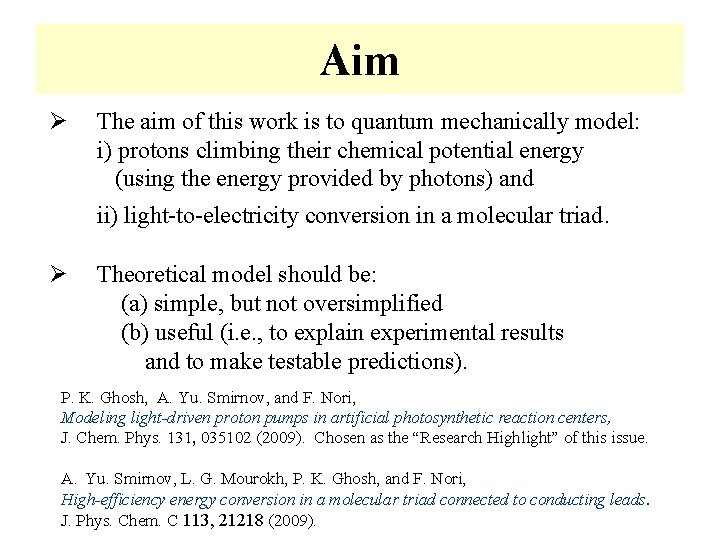

Aim Ø The aim of this work is to quantum mechanically model: i) protons climbing their chemical potential energy (using the energy provided by photons) and ii) light-to-electricity conversion in a molecular triad. Ø Theoretical model should be: (a) simple, but not oversimplified (b) useful (i. e. , to explain experimental results and to make testable predictions). P. K. Ghosh, A. Yu. Smirnov, and F. Nori, Modeling light-driven proton pumps in artificial photosynthetic reaction centers, J. Chem. Phys. 131, 035102 (2009). Chosen as the “Research Highlight” of this issue. A. Yu. Smirnov, L. G. Mourokh, P. K. Ghosh, and F. Nori, High-efficiency energy conversion in a molecular triad connected to conducting leads. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 21218 (2009).

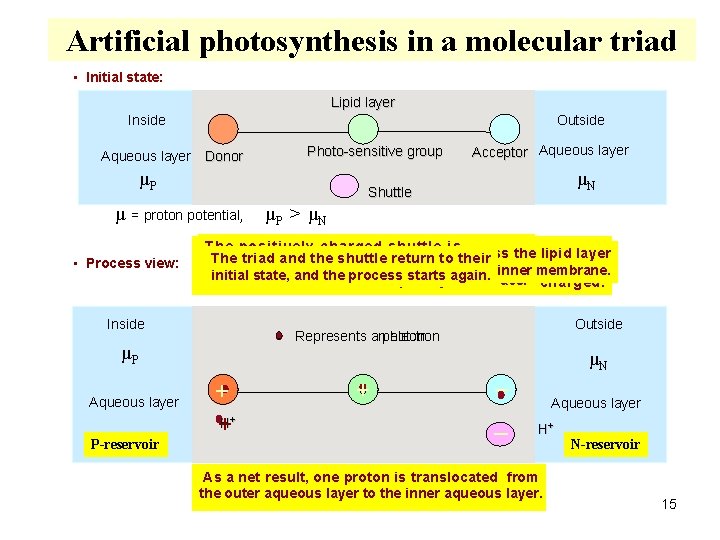

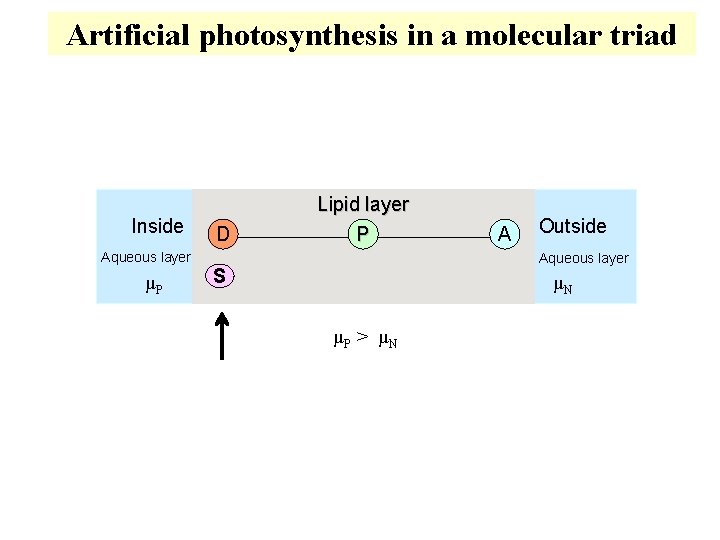

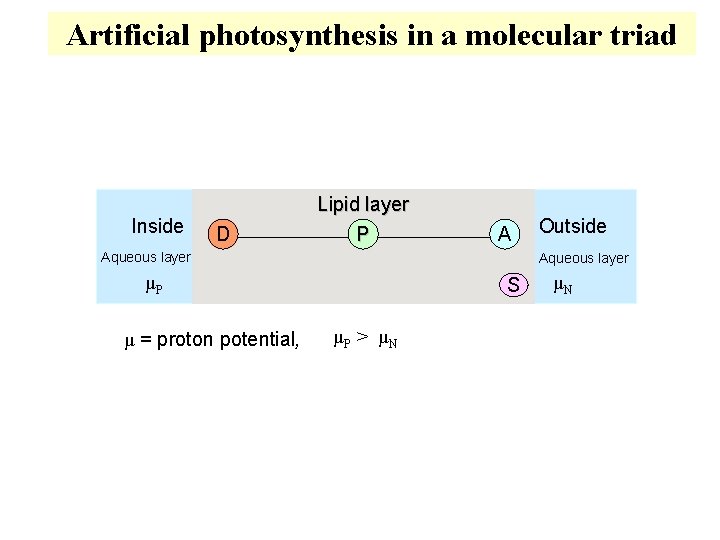

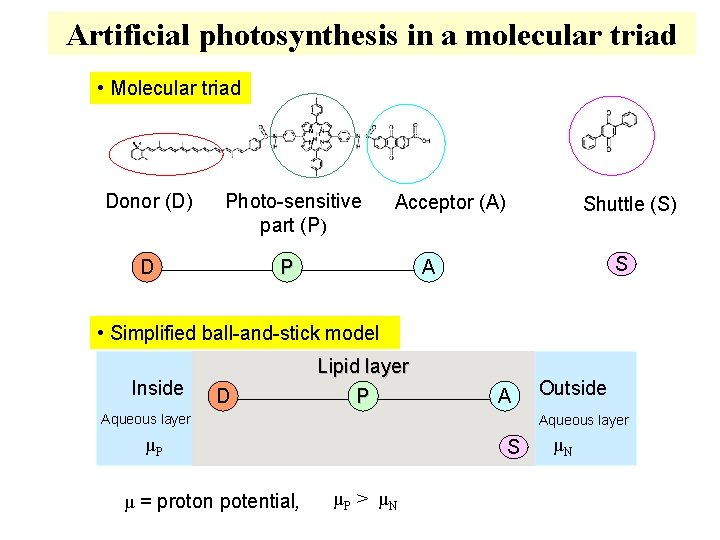

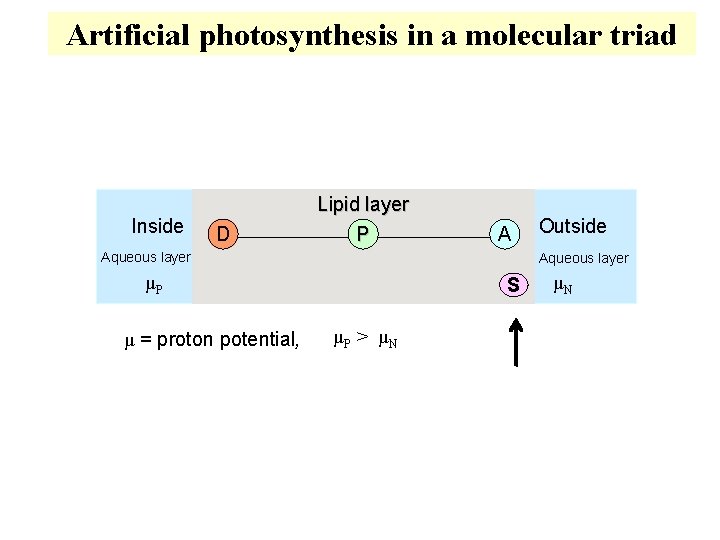

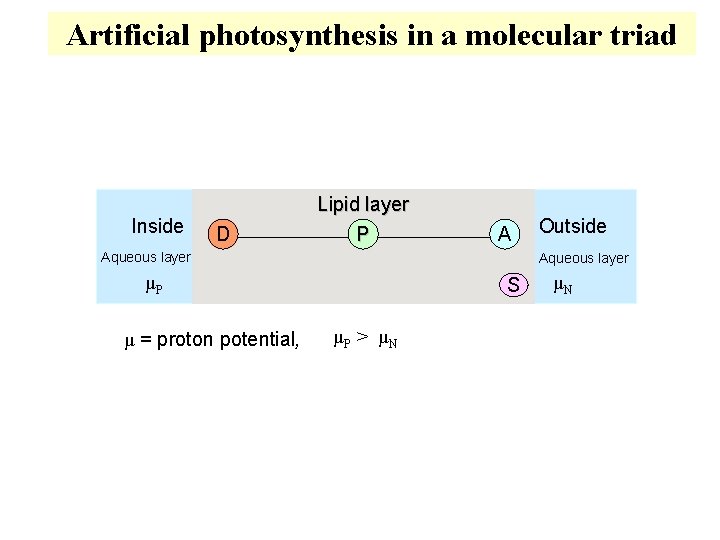

Artificial photosynthesis in a molecular triad • Molecular triad Donor (D) Photo-sensitive part (P) D P Acceptor (A) Shuttle (S) S A • Simplified ball-and-stick model Inside D Lipid layer P A Aqueous layer μP μ = proton potential, Outside S μP > μN μN

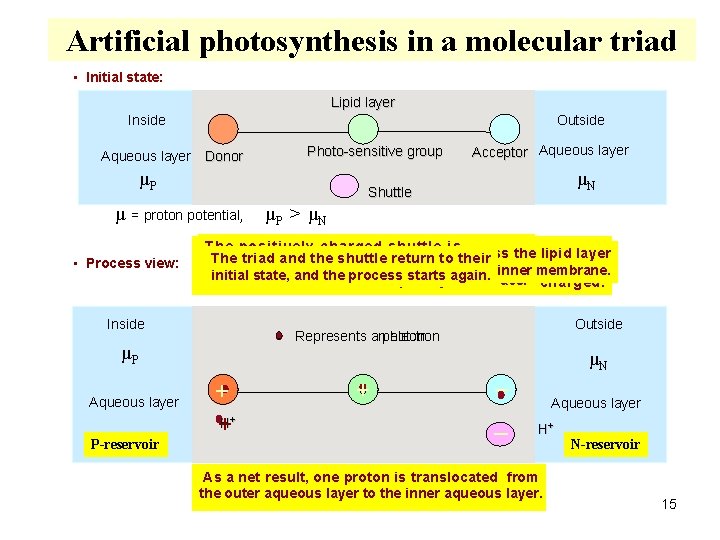

Artificial photosynthesis in a molecular triad • Initial state: Lipid layer Outside Inside Aqueous layer Donor Photo-sensitive group μP Outside Represents a anphoton electron μP + +H + P-reservoir μP > μN The positively charged shuttle charged cannot shuttle diffuse is the across The photo-sensitive part that just lost an electron tolayer the The shuttle receives aan proton from The neutral shuttle slowly diffuses across the lipid The A The quantum The shuttle higher-energy triad shuttle and is gives of deprotonated light accepts the away shuttle electron (a photon) an electron return is by is transferred donating absorbed to from their the to by Blinking: The photo-sensitive group is trapped theaqueous non-polar thelayer interface lipid layer. because Hence, itit remains acceptor isatnow positively charged. This attracts an electron near and becomes neutral. and carries the electron and proton to the inner membrane. a the initial proton acceptor, photosensitive state, and the and making inner becomes the process part it aqueous negatively of starts the phase. molecule. charged. again. charged. excited to a higher electron-energy state. to the positively charged donor. cannot almost static across near thethe lipid-aqueous lipid layer. positively interface. charged. from thediffuse donor, making the donor Inside Aqueous layer μN Shuttle μ = proton potential, • Process view: Acceptor Aqueous layer + μN _ _ Aqueous layer H+ As a net result, one proton is translocated from the outer aqueous layer to the inner aqueous layer. N-reservoir 15

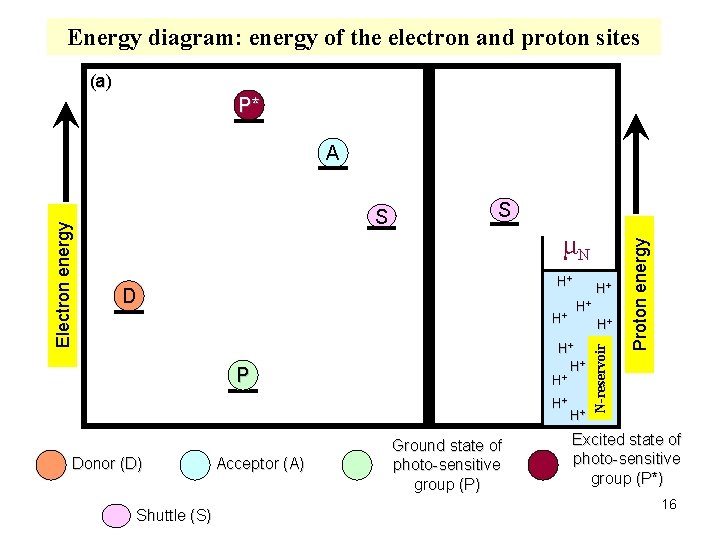

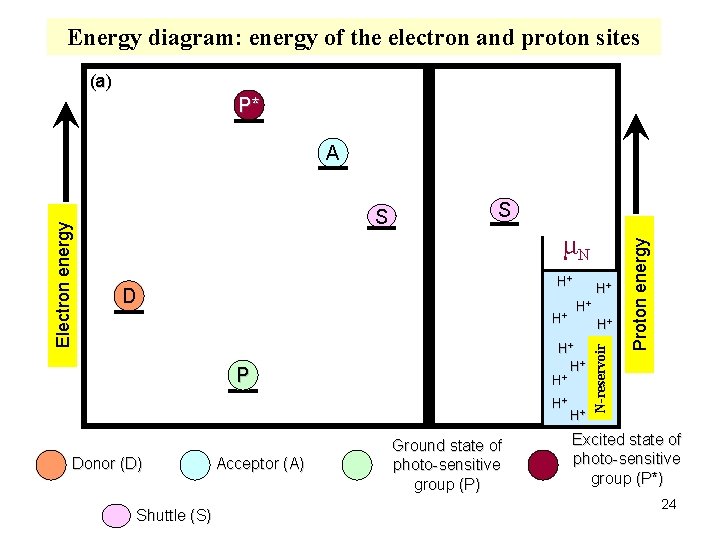

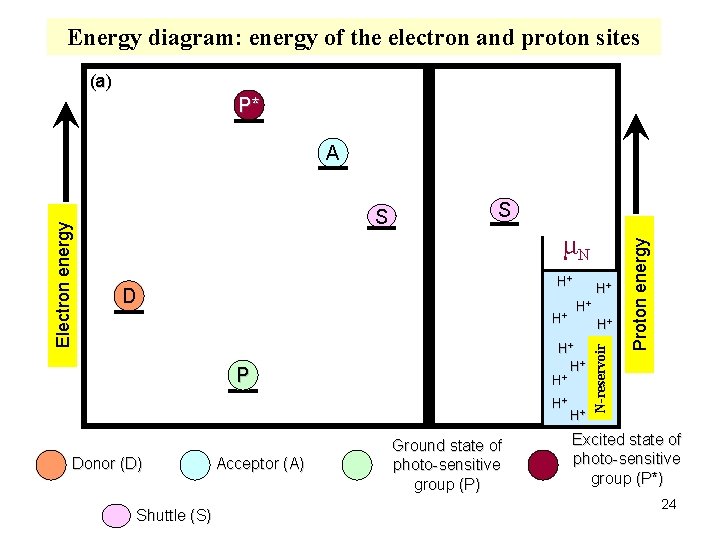

Energy diagram: energy of the electron and proton sites (a) P* S μN H+ D H+ H+ Shuttle (S) Acceptor (A) H+ H+ H+ P Donor (D) H+ Ground state of photo-sensitive group (P) H+ Proton energy S N-reservoir Electron energy A H+ Excited state of photo-sensitive group (P*) 16

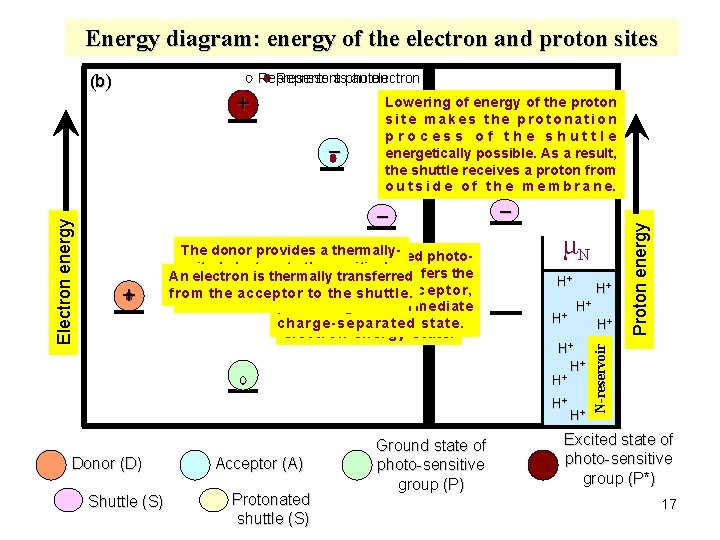

Energy diagram: energy of the electron and proton sites Represents a photon an electron _ Lowering of energy of the proton site makes the protonation p r o c e. The s scharging o f t h eof the shu ttle shuttle energetically a result, by an possible. electron As lowers the shuttle receives a proton from energy of the proton site. o u t s i d e o f t h e m b r a n e. Electron energy _ + The donor provides a thermally. The unstable excited photoexited electronsensitive to the positivelygroup transfers the An electron is thermally T h e p htransferred o tpart o-se nsitive charged photosensitive electron toshuttle. theofacceptor, from the acceptor to the a. photon t h e m o l e c producing ugroup l e. absorbs an intermediate and is excited to a higher charge-separated state. electron-energy state. _ μN H+ H+ Donor (D) Shuttle (S) Acceptor (A) Protonated shuttle (S) H+ H+ Ground state of photo-sensitive group (P) H+ Proton energy + H+ N-reservoir (b) H+ Excited state of photo-sensitive group (P*) 17

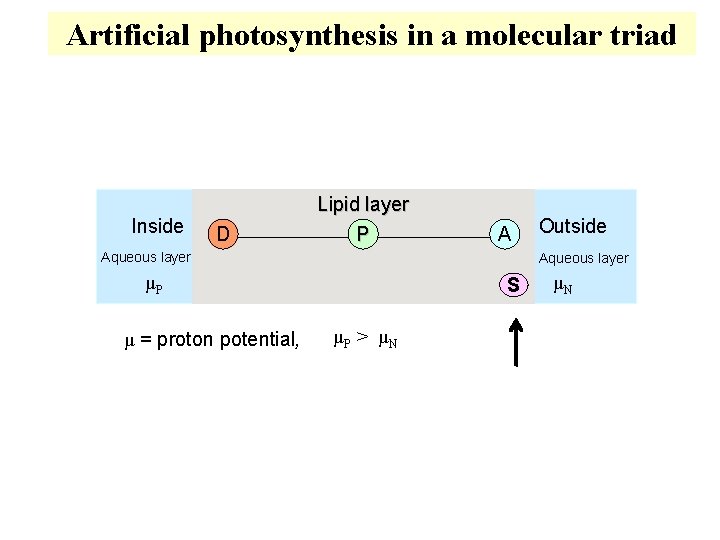

Artificial photosynthesis in a molecular triad Inside D Lipid layer P A Aqueous layer μP μ = proton potential, Outside S μP > μN μN

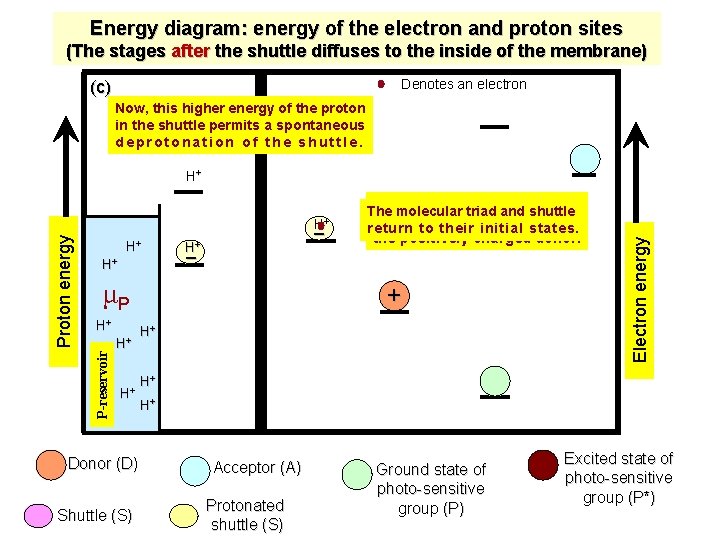

• Stages after the shuttle diffuses to the inner side of the membrane 19

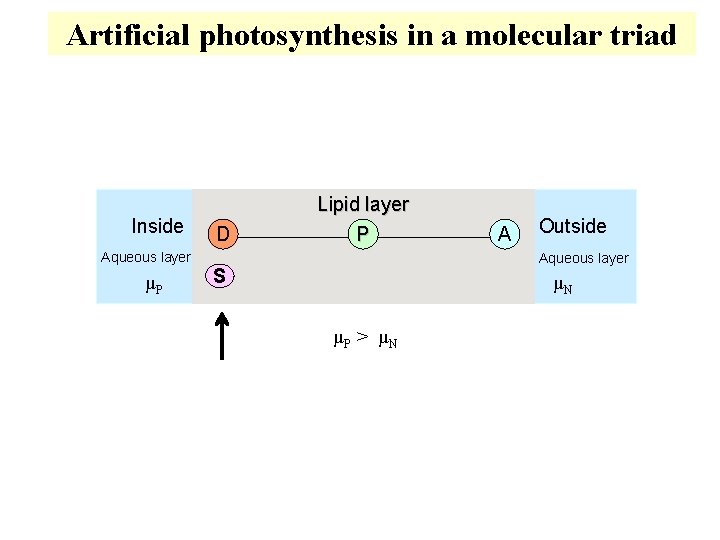

Artificial photosynthesis in a molecular triad Inside D Lipid layer P Aqueous layer μP A Outside Aqueous layer S μN μP > μN

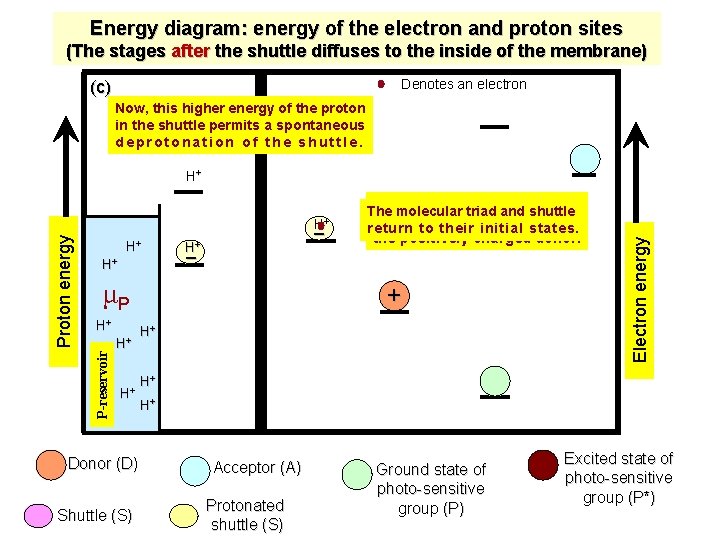

Energy diagram: energy of the electron and proton sites (The stages after the shuttle diffuses to the inside of the membrane) Denotes an electron (c) Now, this When thehigher protonated energy of shuttle the proton loses in the shuttle an electron, permitsthe a spontaneous proton energy d e p r o tin o nthe a t ishuttle o n o f increases. the shuttle. H+ H+ H _+ μP H+ H+ H+ Donor (D) Shuttle (S) An electron thermally transfers The molecular triad and shuttle from the protonated shuttle to return to their initial states. the positively charged donor. + H+ Electron energy H _+ P-reservoir Proton energy H+ H+ H+ Acceptor (A) Protonated shuttle (S) Ground state of photo-sensitive group (P) Excited state of photo-sensitive group (P*)

Artificial photosynthesis in a molecular triad Inside D Lipid layer P A Aqueous layer μP μ = proton potential, Outside S μP > μN μN

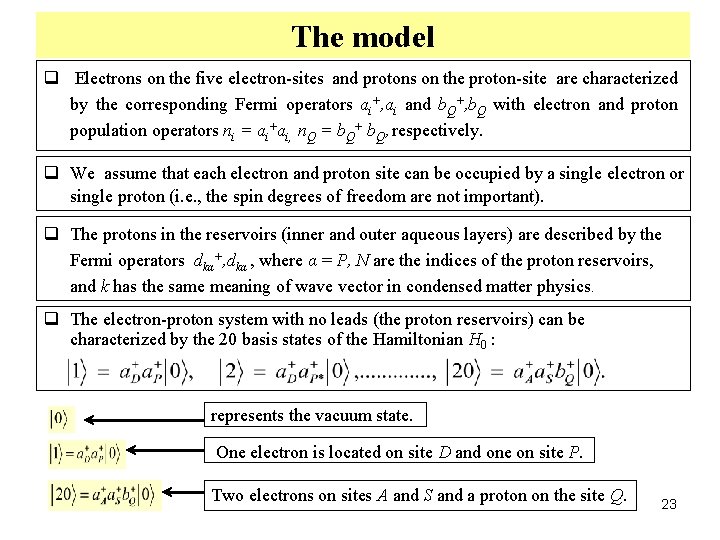

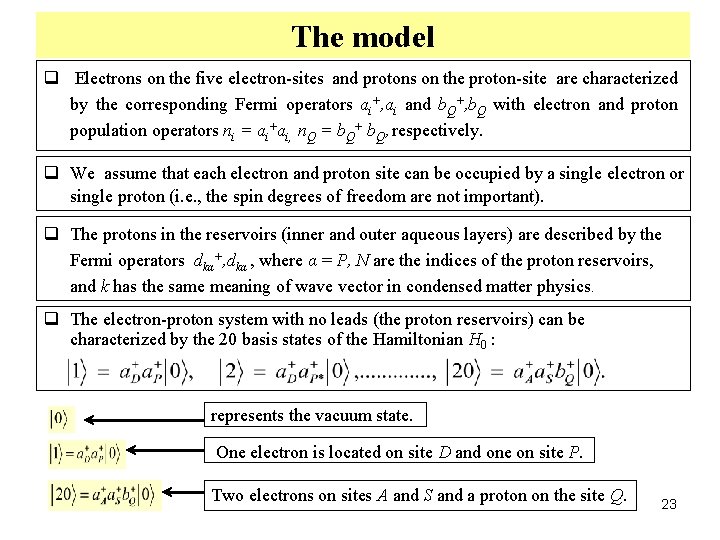

The model q Electrons on the five electron-sites and protons on the proton-site are characterized by the corresponding Fermi operators ai+, ai and b. Q+, b. Q with electron and proton population operators ni = ai+ai, n. Q = b. Q+ b. Q, respectively. q We assume that each electron and proton site can be occupied by a single electron or single proton (i. e. , the spin degrees of freedom are not important). q The protons in the reservoirs (inner and outer aqueous layers) are described by the Fermi operators dkα+, dkα , where α = P, N are the indices of the proton reservoirs, and k has the same meaning of wave vector in condensed matter physics. q The electron-proton system with no leads (the proton reservoirs) can be characterized by the 20 basis states of the Hamiltonian H 0 : represents the vacuum state. One electron is located on site D and one on site P. Two electrons on sites A and S and a proton on the site Q. 23

Energy diagram: energy of the electron and proton sites (a) P* S μN H+ D H+ H+ Shuttle (S) Acceptor (A) H+ H+ H+ P Donor (D) H+ Ground state of photo-sensitive group (P) H+ Proton energy S N-reservoir Electron energy A H+ Excited state of photo-sensitive group (P*) 24

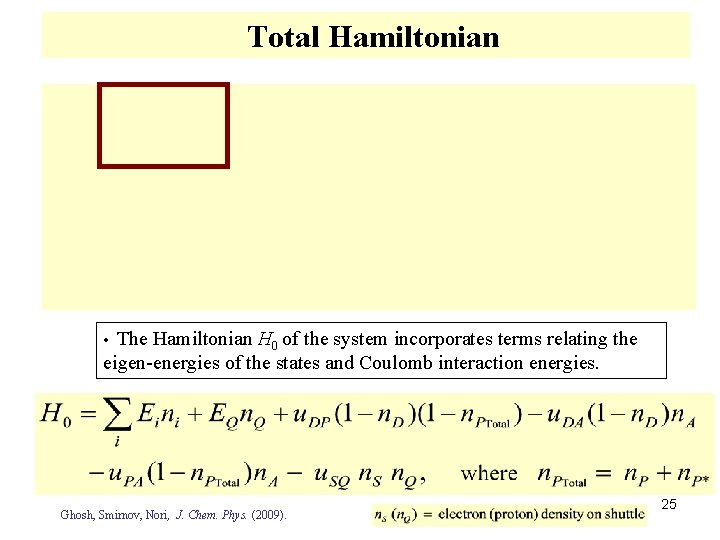

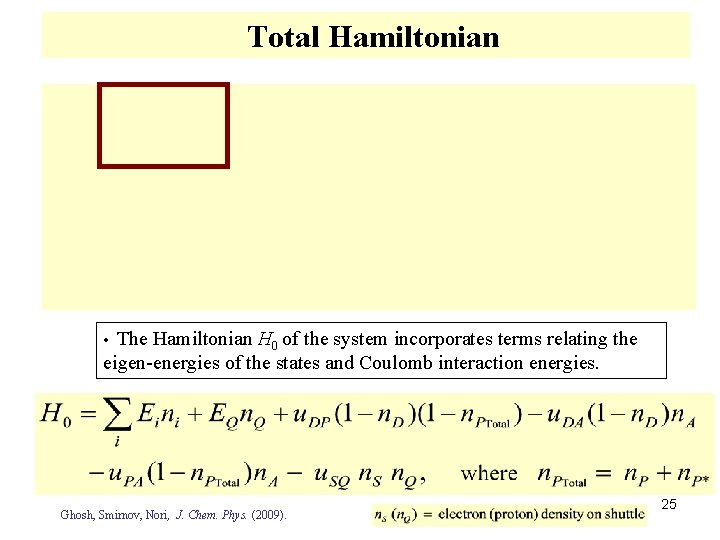

Total Hamiltonian The Hamiltonian H 0 of the system incorporates terms relating the eigen-energies of the states and Coulomb interaction energies. • Ghosh, Smirnov, Nori, J. Chem. Phys. (2009). 25

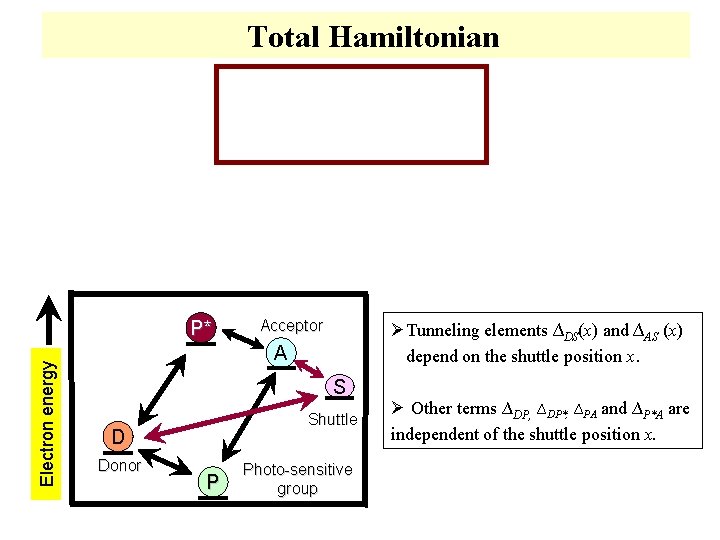

Total Hamiltonian Electron energy P* Acceptor ØTunneling elements ∆DS(x) and ∆AS (x) depend on the shuttle position x. A S Shuttle D Donor P Photo-sensitive group Ø Other terms ∆DP, ∆DP*, ∆PA and ∆P*A are independent of the shuttle position x.

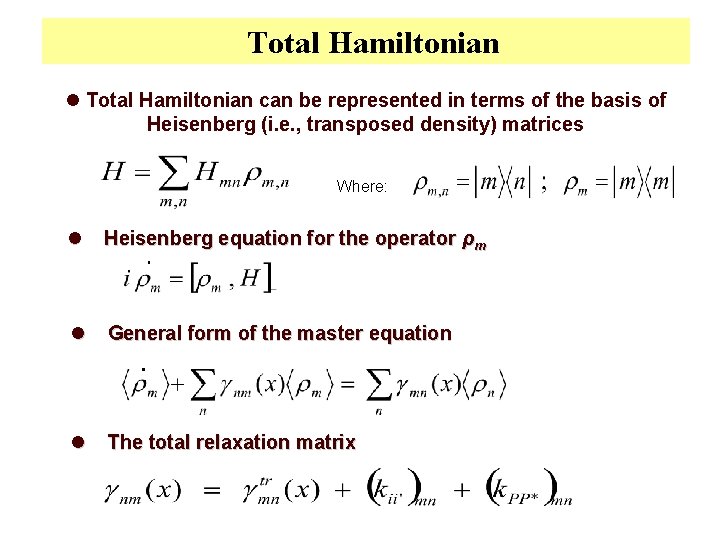

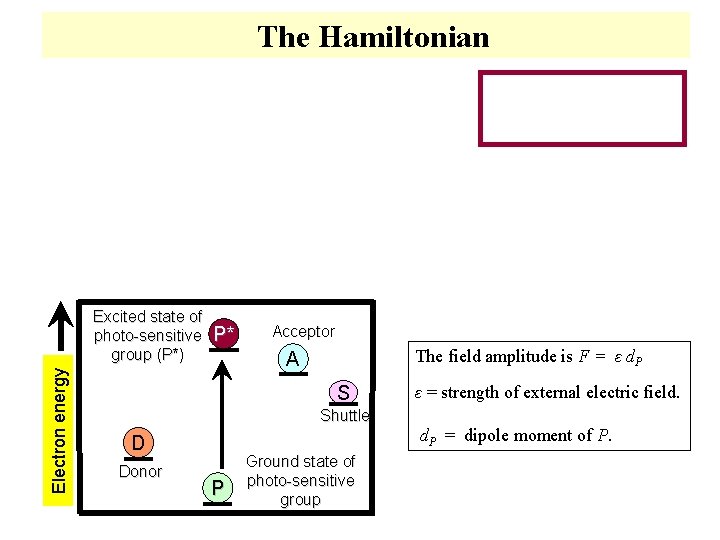

The Hamiltonian Electron energy Excited state of photo-sensitive group (P*) P* Acceptor The field amplitude is F = ε d. P A S ε = strength of external electric field. Shuttle d. P = dipole moment of P. D Donor P Ground state of photo-sensitive group

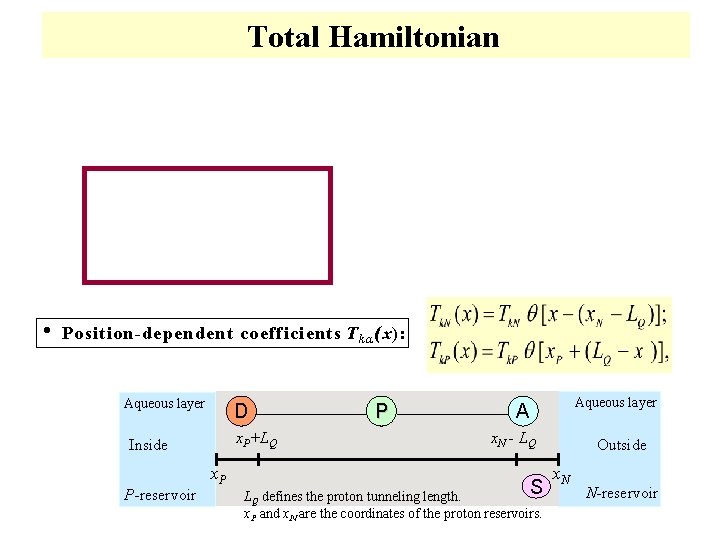

Total Hamiltonian • Position-dependent coefficients T kα ( x) : Aqueous layer D x. P+LQ Inside P-reservoir x. P P Aqueous layer A x N - LQ S LQ defines the proton tunneling length. x. P and x. N are the coordinates of the proton reservoirs. Outside x. N N-reservoir

Total Hamiltonian • The medium surrounding the active sites is represented by a system of harmonic oscillators. These oscillators are coupled to the active sites. • The parameters xji determine the strengths of the coupling between the electron subsystem and the environment. 29

Total Hamiltonian l Total Hamiltonian can be represented in terms of the basis of Heisenberg (i. e. , transposed density) matrices Where: l Heisenberg equation for the operator ρm l General form of the master equation l The total relaxation matrix . .

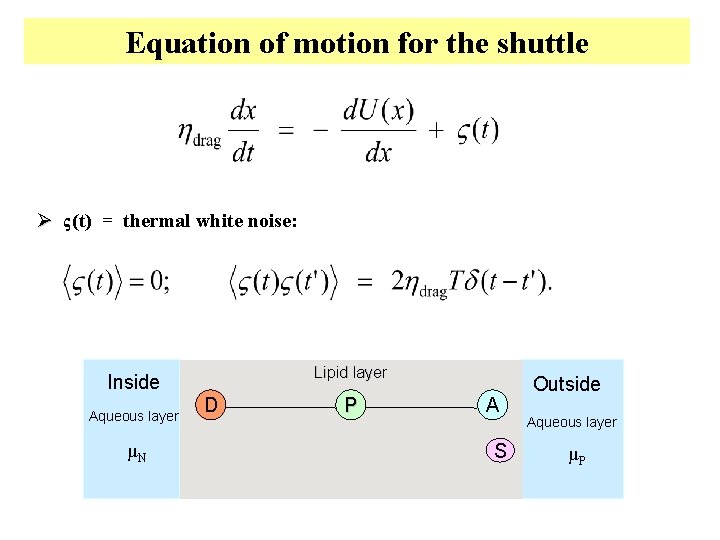

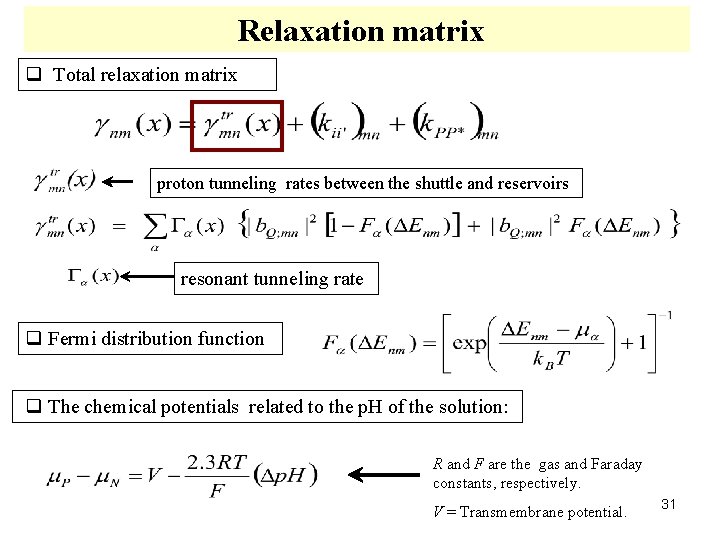

Relaxation matrix q Total relaxation matrix proton tunneling rates between the shuttle and reservoirs resonant tunneling rate q Fermi distribution function q The chemical potentials related to the p. H of the solution: R and F are the gas and Faraday constants, respectively. V = Transmembrane potential. 31

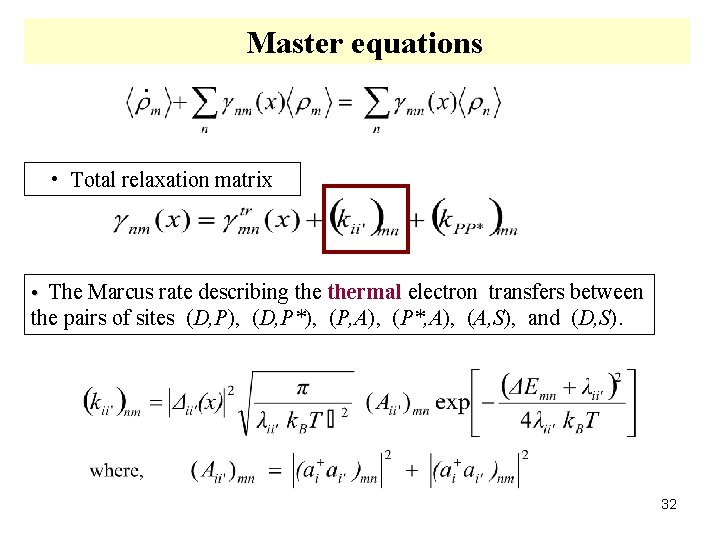

Master equations . • Total relaxation matrix • The Marcus rate describing thermal electron transfers between the pairs of sites (D, P), (D, P*), (P, A), (P*, A), (A, S), and (D, S). 32

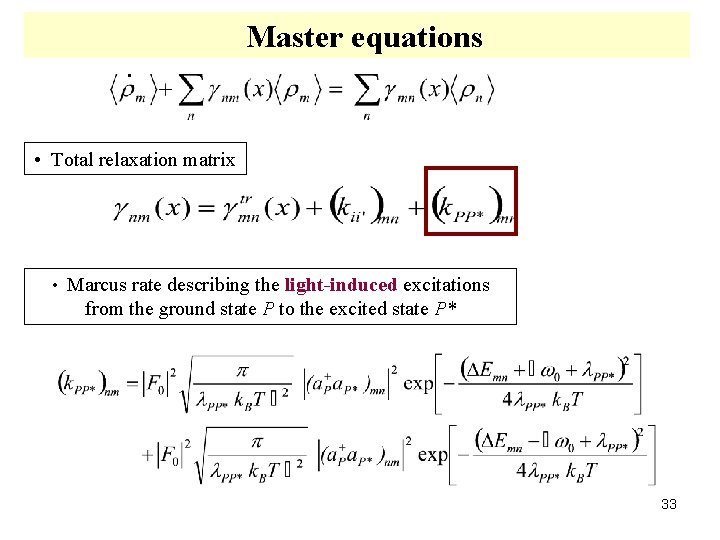

. Master equations • Total relaxation matrix • Marcus rate describing the light-induced excitations from the ground state P to the excited state P* 33

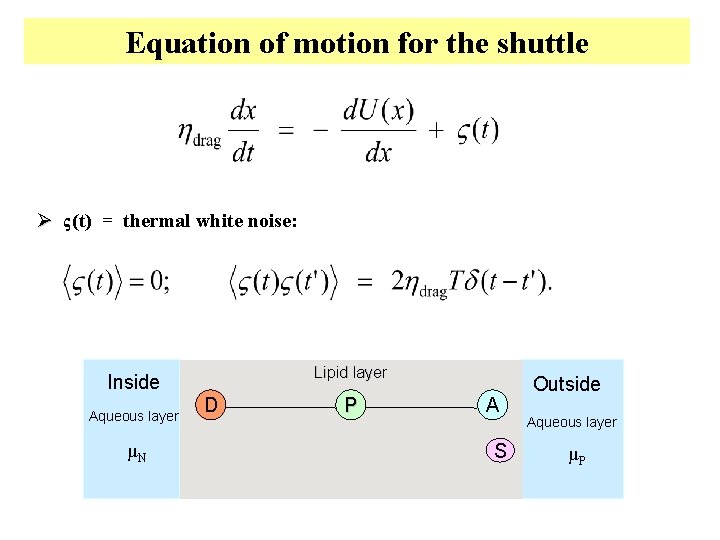

Equation of motion for the shuttle Ø ς(t) = thermal white noise: Lipid layer Inside Aqueous layer μN D P A S Outside Aqueous layer μP

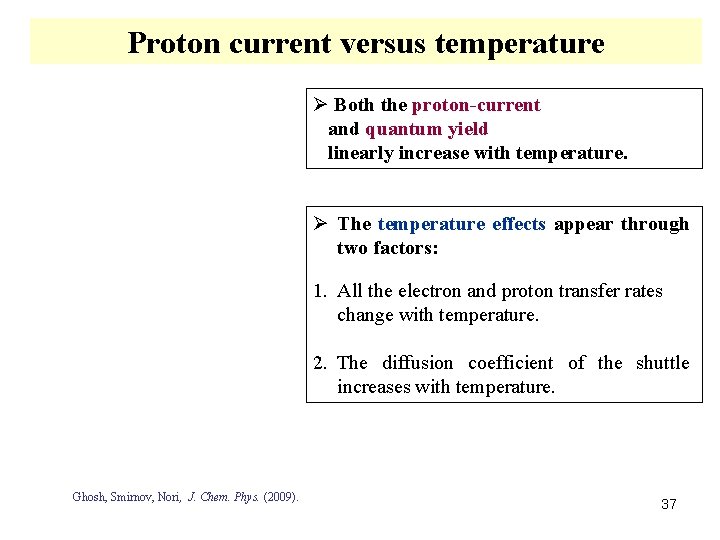

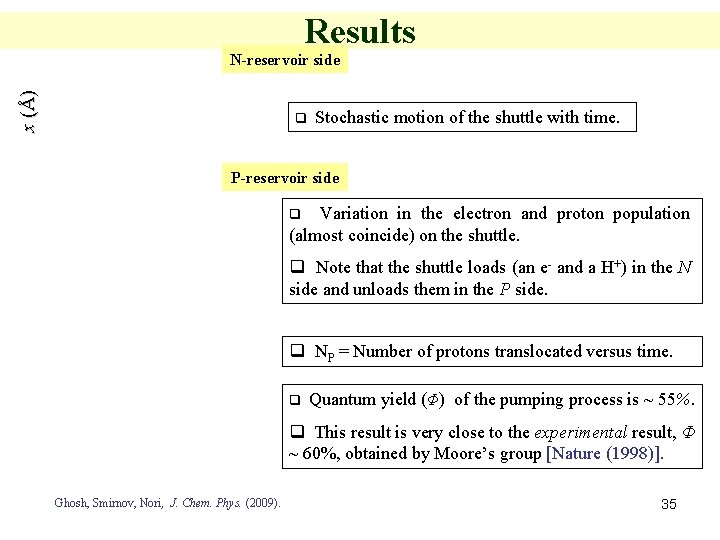

Results x (Å ) N-reservoir side q Stochastic motion of the shuttle with time. P-reservoir side Variation in the electron and proton population (almost coincide) on the shuttle. q q Note that the shuttle loads (an e- and a H+) in the N side and unloads them in the P side. q NP = Number of protons translocated versus time. q Quantum yield (Φ) of the pumping process is ~ 55%. q This result is very close to the experimental result, Φ ~ 60%, obtained by Moore’s group [Nature (1998)]. Ghosh, Smirnov, Nori, J. Chem. Phys. (2009). 35

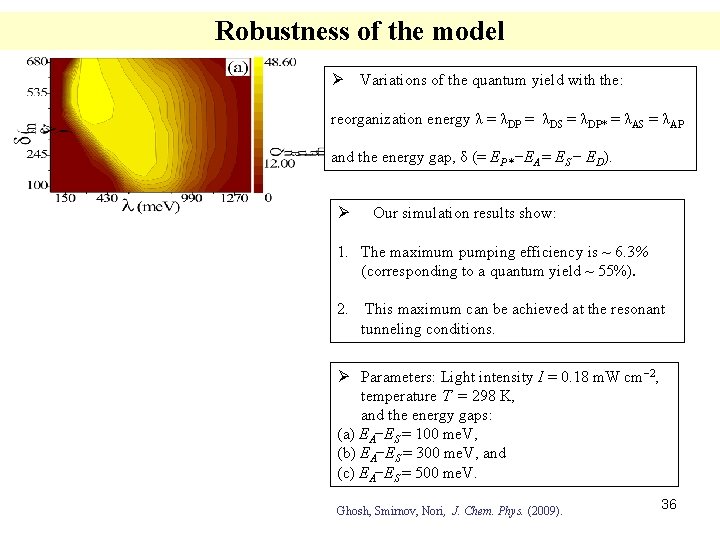

Robustness of the model Ø Variations of the quantum yield with the: reorganization energy λ = λDP = λDS = λDP* = λAS = λAP and the energy gap, δ (= EP* −EA = ES − ED). Ø Our simulation results show: 1. The maximum pumping efficiency is ~ 6. 3% (corresponding to a quantum yield ~ 55%). 2. This maximum can be achieved at the resonant tunneling conditions. Ø Parameters: Light intensity I = 0. 18 m. W cm− 2, temperature T = 298 K, and the energy gaps: (a) EA−ES = 100 me. V, (b) EA−ES = 300 me. V, and (c) EA−ES = 500 me. V. Ghosh, Smirnov, Nori, J. Chem. Phys. (2009). 36

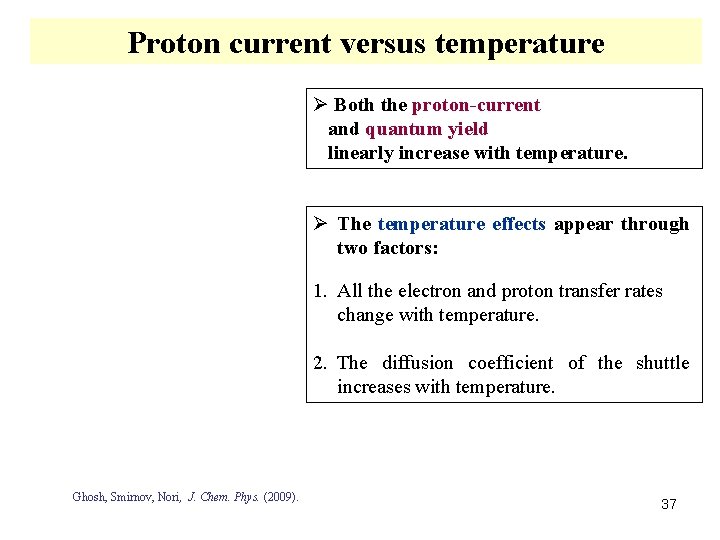

Proton current versus temperature Ø Both the proton-current and quantum yield linearly increase with temperature. Ø The temperature effects appear through two factors: 1. All the electron and proton transfer rates change with temperature. 2. The diffusion coefficient of the shuttle increases with temperature. Ghosh, Smirnov, Nori, J. Chem. Phys. (2009). 37

Proton current versus light intensity Ø The proton current is roughly linear for small intensities of light, but it saturates with higher light-intensity. ØThis is consistent with experiments. Ø The pumping quantum efficiency decreases with light-intensity, for all temperatures (because the number of unsuccessful attempts to pump protons also increases, decreasing the quantum yield). 38

Proton current versus proton potentials of the leads Ø The proton current saturates when the P-side (left) potential is sufficiently low, μP < 160 me. V, and goes to zero when μP > 200 me. V (i. e. μP > EQ). Ø Also, the pumping device does not work when the potential μN is too low μN < EQ − u. SQ. Ø Main parameters: I=0. 18 m. W cm− 2, temperature T = 298 K. 39

Summary of light-driven proton pumps l Our study is the only theoretical model for the quantitative study of light-driven protons pumps in a molecular triad. l Our results explain previous experimental findings on light-to -proton energy conversion in a molecular triad. l We compute several quantities and how they vary with various parameters (e. g. , light intensity, temperature, chemical potentials). l We have shown that, under resonant tunneling conditions, the power conversion efficiency increases drastically. This prediction could be useful for further experiments. 40

Second part of the talk starts here (~ ten slides) High-efficiency energy conversion in a molecular triad connected to conducting electrodes. Smirnov, Mourokh, Ghosh, and Nori, High-efficiency energy conversion in a molecular triad connected to conducting leads. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 21218 (2009). Complimentary color copies of these are available online. 41

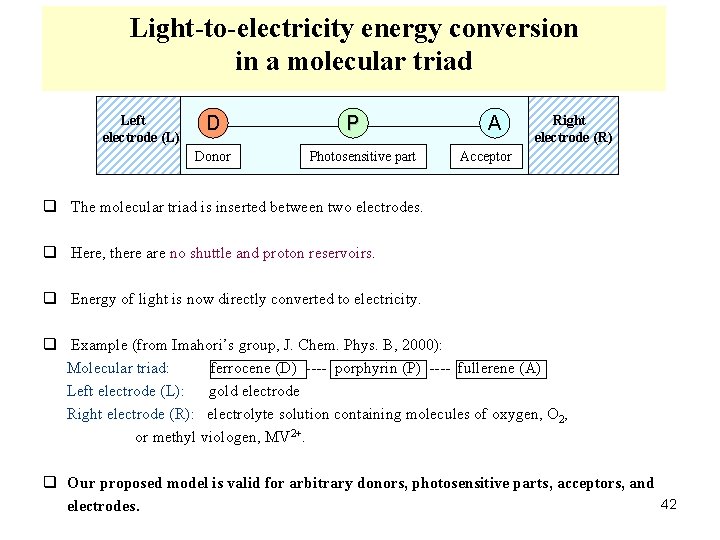

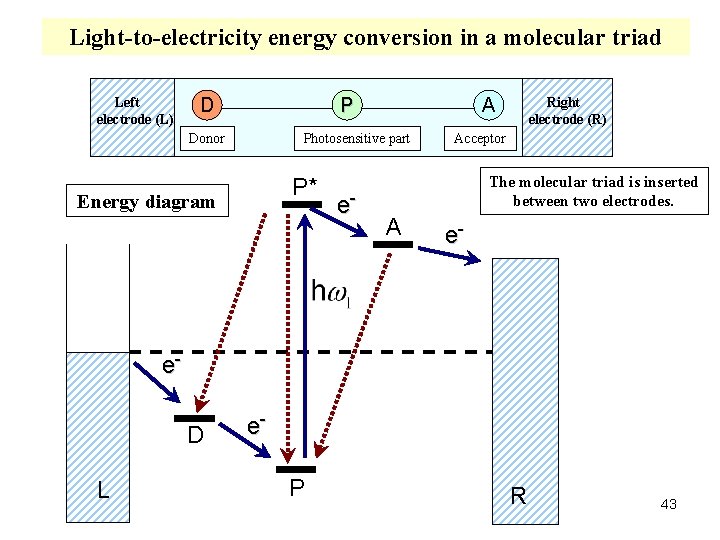

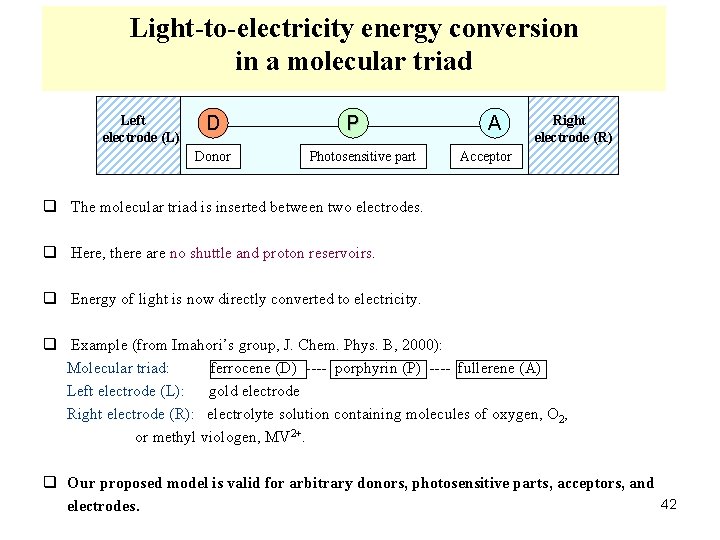

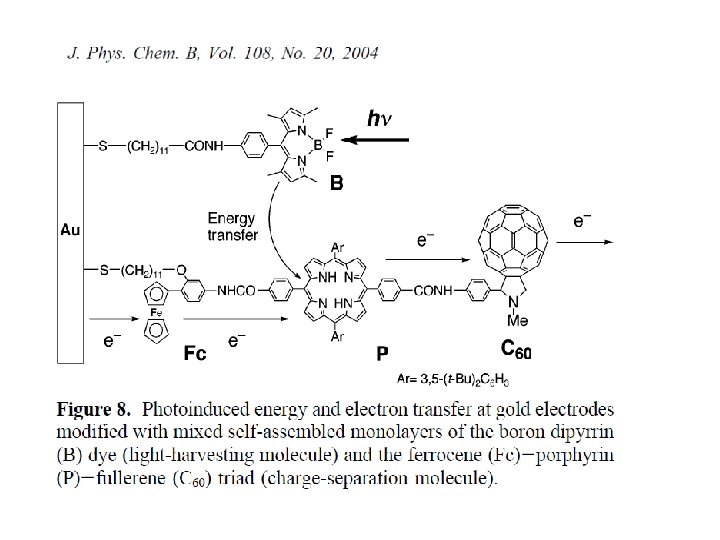

Light-to-electricity energy conversion in a molecular triad Left electrode (L) D Donor P Photosensitive part A Right electrode (R) Acceptor q The molecular triad is inserted between two electrodes. q Here, there are no shuttle and proton reservoirs. q Energy of light is now directly converted to electricity. q Example (from Imahori’s group, J. Chem. Phys. B, 2000): Molecular triad: ferrocene (D) ---- porphyrin (P) ---- fullerene (A) Left electrode (L): gold electrode Right electrode (R): electrolyte solution containing molecules of oxygen, O 2, or methyl viologen, MV 2+. q Our proposed model is valid for arbitrary donors, photosensitive parts, acceptors, and 42 electrodes.

Light-to-electricity energy conversion in a molecular triad Left electrode (L) D P Donor A Photosensitive part P* Energy diagram e- Right electrode (R) Acceptor The molecular triad is inserted between two electrodes. A e- e. D L e. P R 43

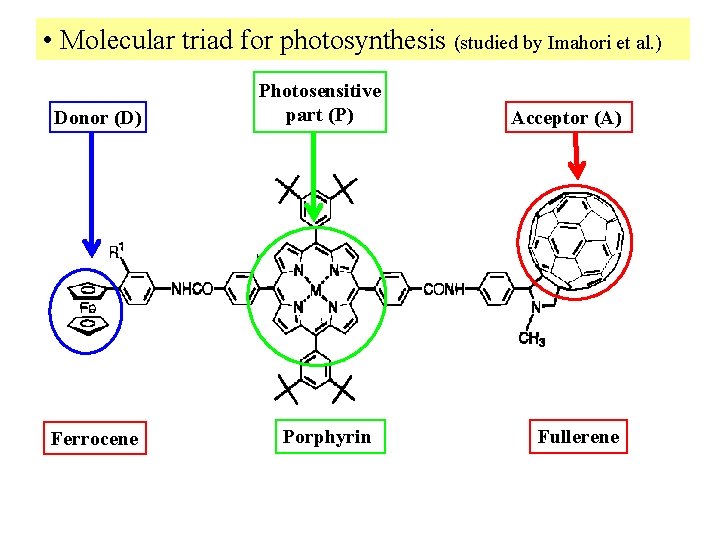

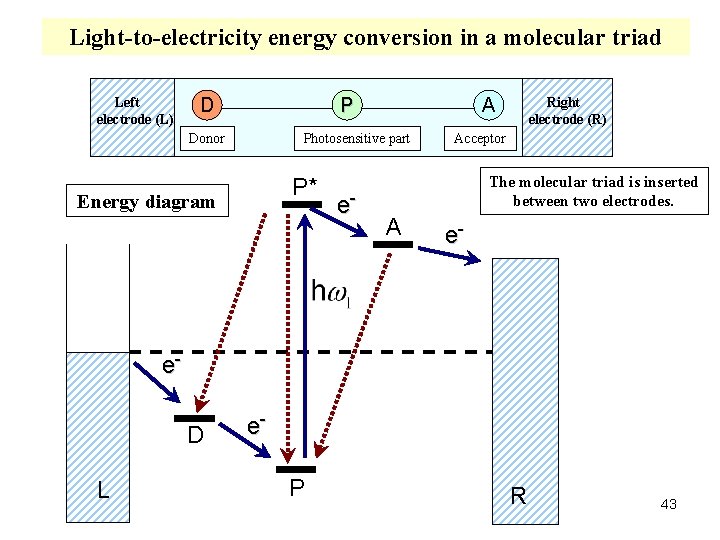

• Molecular triad for photosynthesis (studied by Imahori et al. ) Donor (D) Ferrocene Photosensitive part (P) Porphyrin Acceptor (A) Fullerene

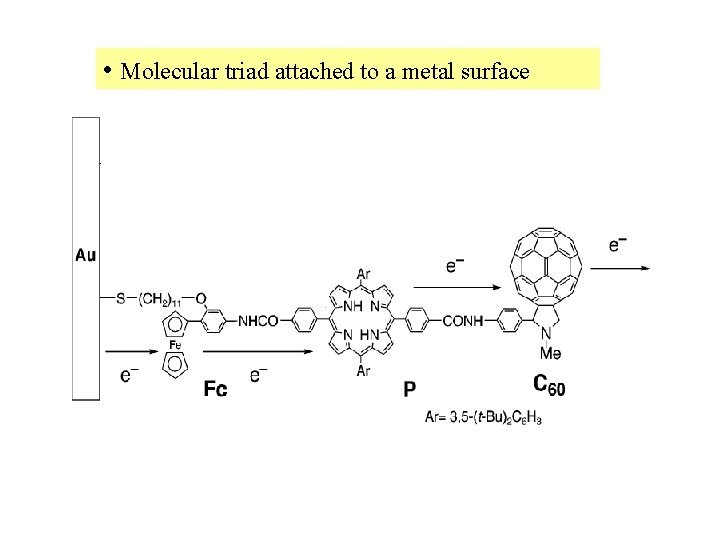

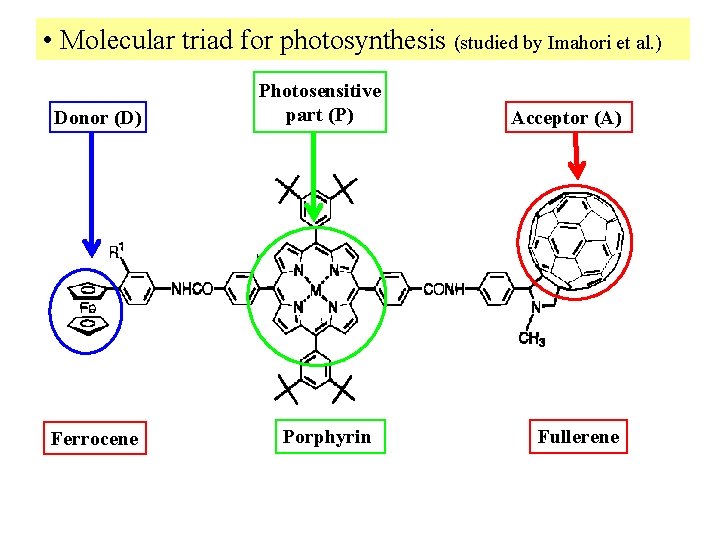

• Molecular triad attached to a metal surface

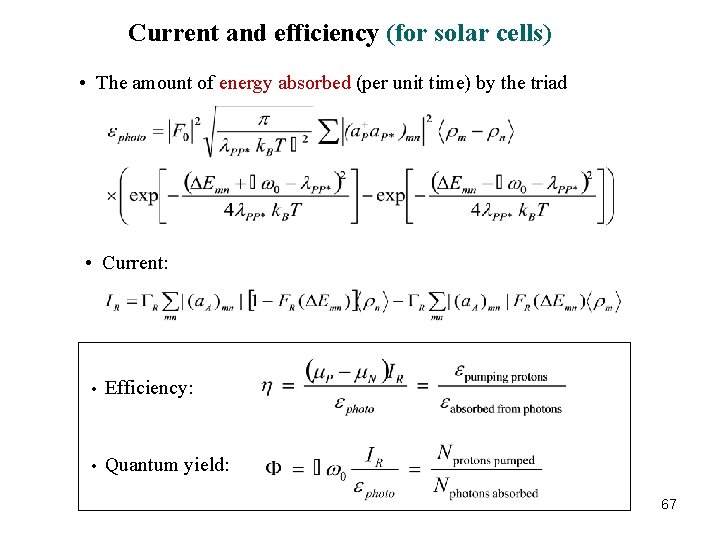

For solar cells: Input energy = (number of photons absorbed) x ћω0 Output energy = (number of electrons pumped) x (μP - μN) Efficiency = (output energy) / (input energy) Efficiency = (Quantum yield) x (μP - μN ) / ћω0 Quantum yield Φ = (# of electrons pumped) / (# photons absorbed) 46

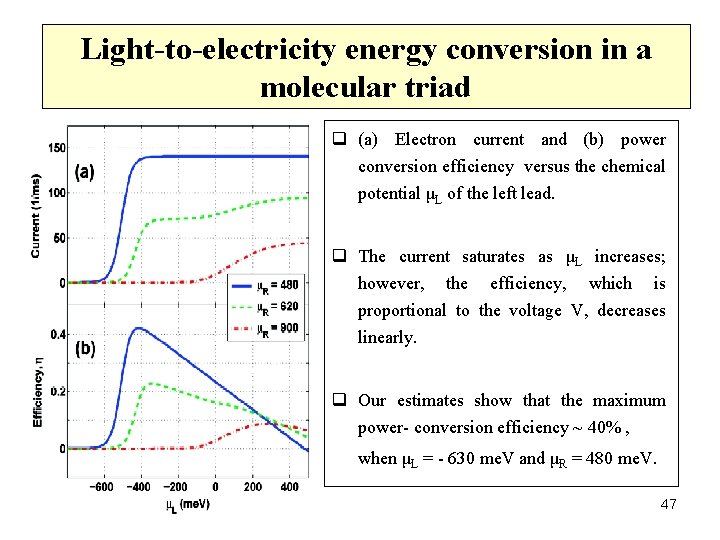

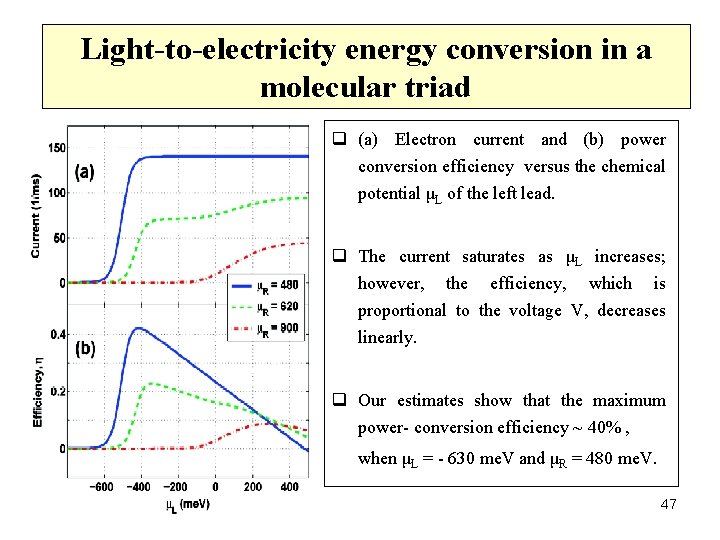

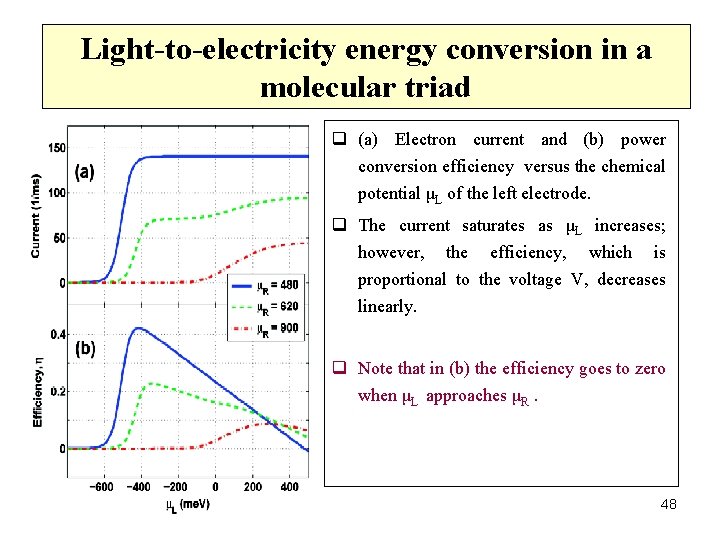

Light-to-electricity energy conversion in a molecular triad q (a) Electron current and (b) power conversion efficiency versus the chemical potential μL of the left lead. q The current saturates as μL increases; however, the efficiency, which is proportional to the voltage V, decreases linearly. q Our estimates show that the maximum power- conversion efficiency ~ 40% , when μL = - 630 me. V and μR = 480 me. V. 47

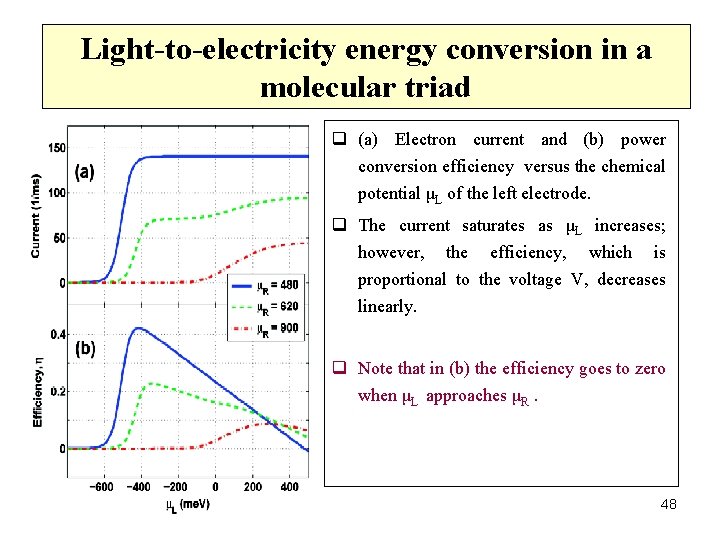

Light-to-electricity energy conversion in a molecular triad q (a) Electron current and (b) power conversion efficiency versus the chemical potential μL of the left electrode. q The current saturates as μL increases; however, the efficiency, which is proportional to the voltage V, decreases linearly. q Note that in (b) the efficiency goes to zero when μL approaches μR. 48

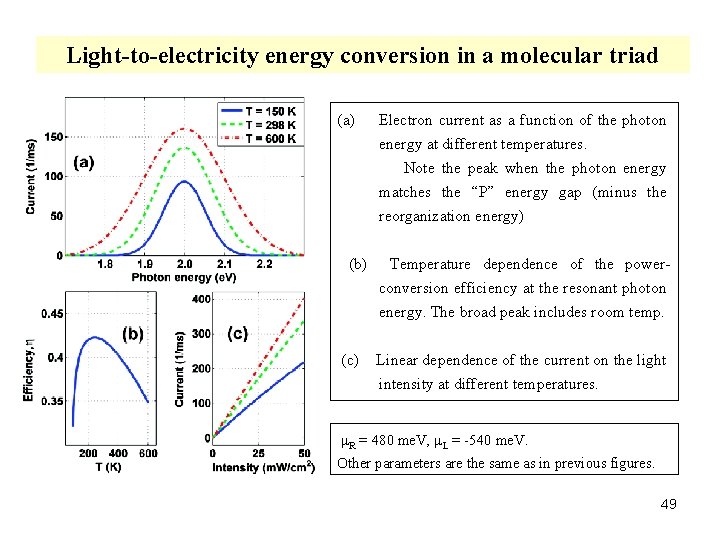

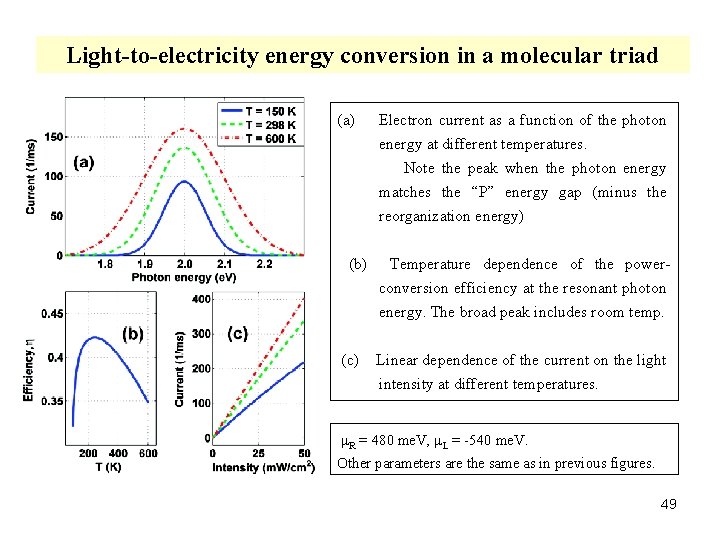

Light-to-electricity energy conversion in a molecular triad (a) (b) (c) Electron current as a function of the photon energy at different temperatures. Note the peak when the photon energy matches the “P” energy gap (minus the reorganization energy) Temperature dependence of the powerconversion efficiency at the resonant photon energy. The broad peak includes room temp. Linear dependence of the current on the light intensity at different temperatures. μR = 480 me. V, μL = -540 me. V. Other parameters are the same as in previous figures. 49

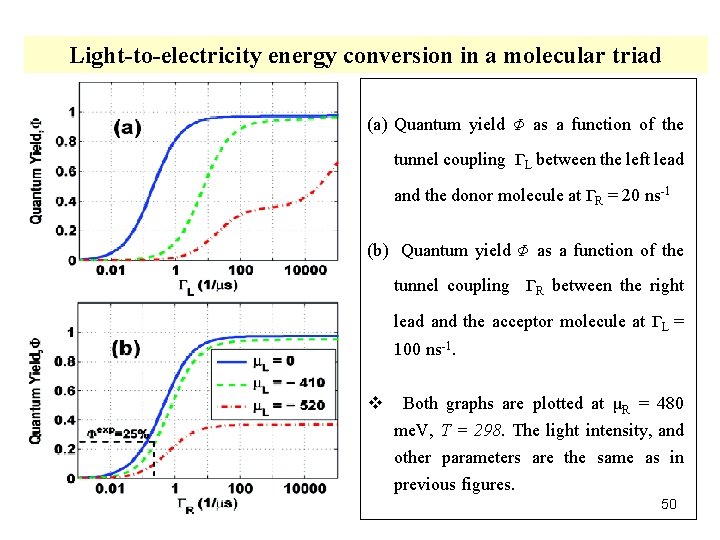

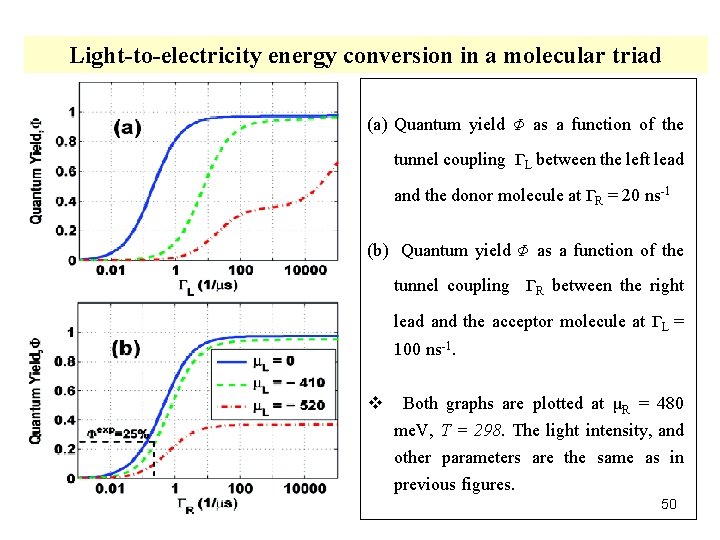

Light-to-electricity energy conversion in a molecular triad (a) Quantum yield Φ as a function of the г. L between the left lead and the donor molecule at г. R = 20 ns-1 tunnel coupling (b) Quantum yield Φ as a function of the tunnel coupling г. R between the right lead and the acceptor molecule at г. L = 100 ns-1. v Both graphs are plotted at μR = 480 me. V, T = 298. The light intensity, and other parameters are the same as in previous figures. 50

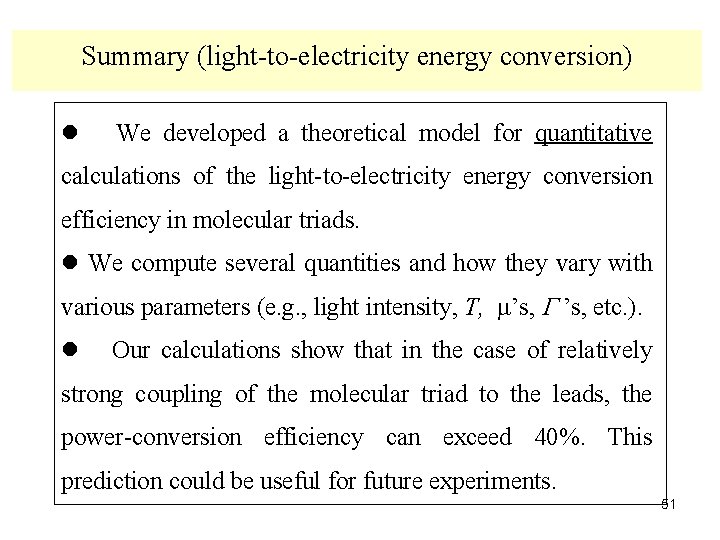

Summary (light-to-electricity energy conversion) l We developed a theoretical model for quantitative calculations of the light-to-electricity energy conversion efficiency in molecular triads. l We compute several quantities and how they vary with various parameters (e. g. , light intensity, T, μ’s, G ’s, etc. ). l Our calculations show that in the case of relatively strong coupling of the molecular triad to the leads, the power-conversion efficiency can exceed 40%. This prediction could be useful for future experiments. 51

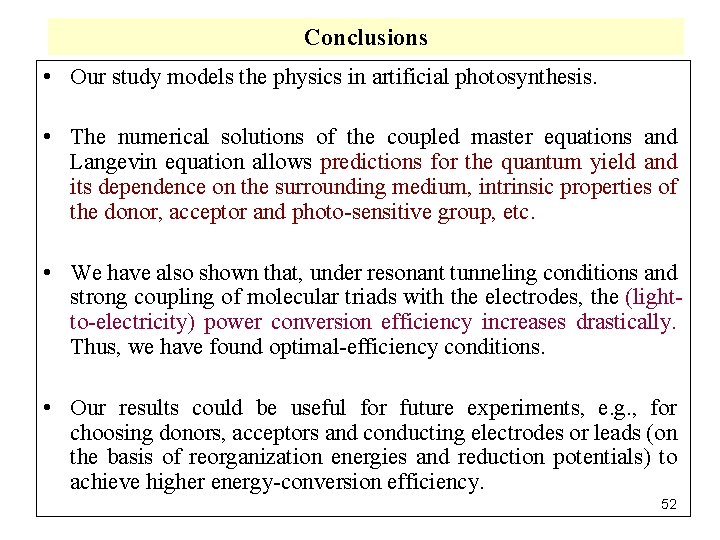

Conclusions • Our study models the physics in artificial photosynthesis. • The numerical solutions of the coupled master equations and Langevin equation allows predictions for the quantum yield and its dependence on the surrounding medium, intrinsic properties of the donor, acceptor and photo-sensitive group, etc. • We have also shown that, under resonant tunneling conditions and strong coupling of molecular triads with the electrodes, the (lightto-electricity) power conversion efficiency increases drastically. Thus, we have found optimal-efficiency conditions. • Our results could be useful for future experiments, e. g. , for choosing donors, acceptors and conducting electrodes or leads (on the basis of reorganization energies and reduction potentials) to achieve higher energy-conversion efficiency. 52

Summary of light-driven proton pumps l Our study is the only theoretical model for the quantitative study of light-driven protons pumps in a molecular triad. l Our results explain previous experimental findings on light-to -proton energy conversion in a molecular triad. l We compute several quantities and how they vary with various parameters (e. g. , light intensity, temperature, chemical potentials). l We have shown that, under resonant tunneling conditions, the power conversion efficiency increases drastically. This prediction could be useful for further experiments. 53

Thanks for your attention 54

Following slides are for the Q & A period (also, those slides can be used for longer talks) 55

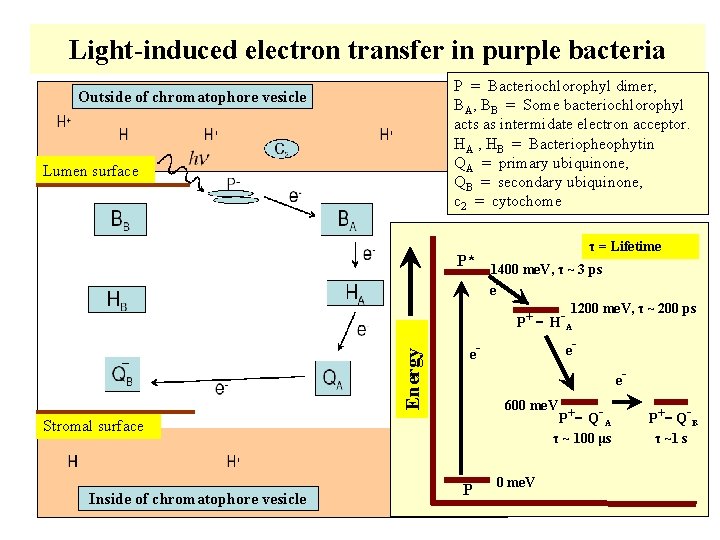

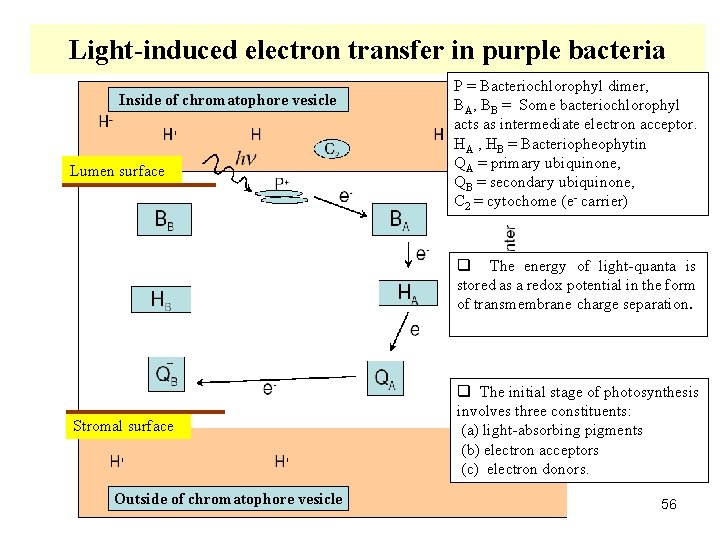

Light-induced electron transfer in purple bacteria Inside of chromatophore vesicle Lumen surface P = Bacteriochlorophyl dimer, BA, BB = Some bacteriochlorophyl acts as intermediate electron acceptor. HA , HB = Bacteriopheophytin QA = primary ubiquinone, QB = secondary ubiquinone, C 2 = cytochome (e- carrier) q The energy of light-quanta is stored as a redox potential in the form of transmembrane charge separation. Stromal surface Outside of chromatophore vesicle q The initial stage of photosynthesis involves three constituents: (a) light-absorbing pigments (b) electron acceptors (c) electron donors. 56

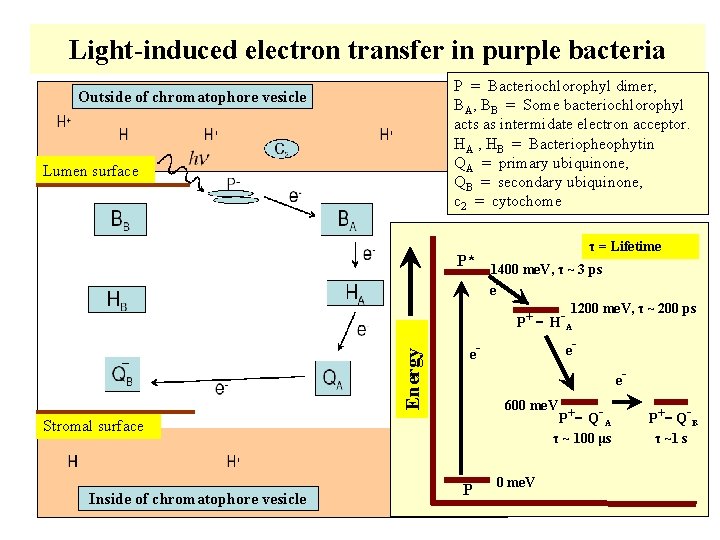

Light-induced electron transfer in purple bacteria P = Bacteriochlorophyl dimer, BA, BB = Some bacteriochlorophyl acts as intermidate electron acceptor. HA , HB = Bacteriopheophytin QA = primary ubiquinone, QB = secondary ubiquinone, c 2 = cytochome Outside of chromatophore vesicle Lumen surface P* τ = Lifetime 1400 me. V, τ ~ 3 ps e- Energy P+ 1200 me. V, τ ~ 200 ps A e- e- e 600 me. V - - P+ Q A τ ~ 100 μs Stromal surface Inside of chromatophore vesicle - H- P - - P+ Q τ ~1 s 0 me. V 57 B

![Mimicking natural photosynthesis Nishitani et al J Am Chem Soc 105 7771 1983 Mimicking natural photosynthesis • Nishitani et al. [J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105, 7771 (1983)],](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/5eb13bb94f04af5874650fdf3814f897/image-58.jpg)

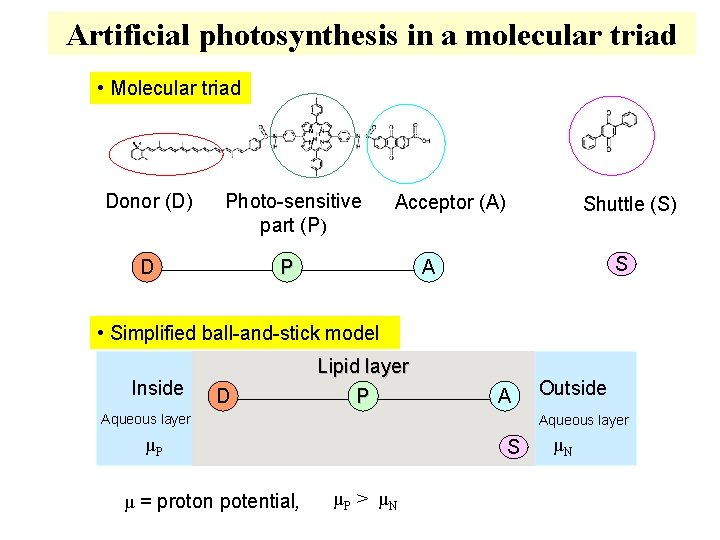

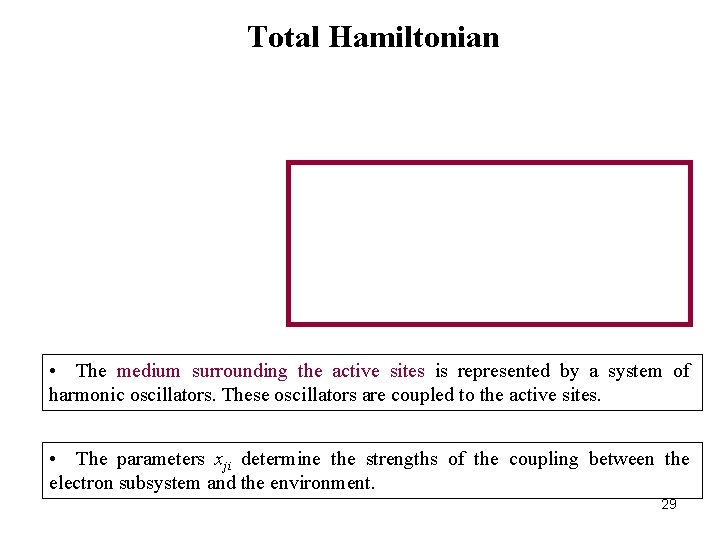

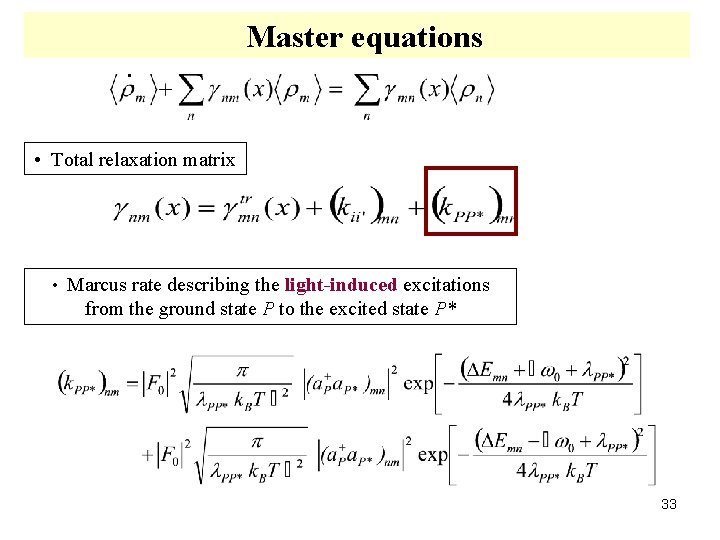

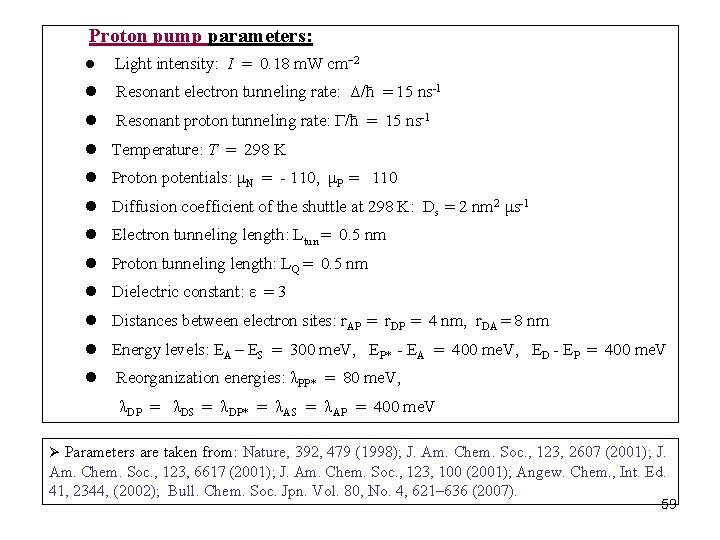

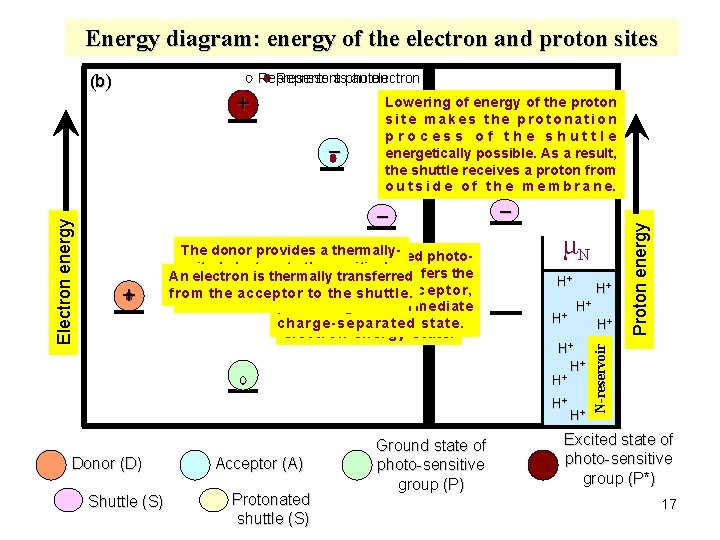

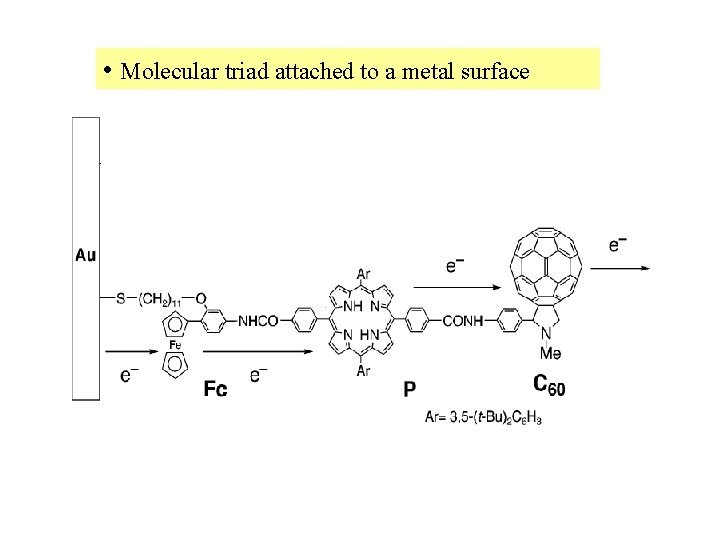

Mimicking natural photosynthesis • Nishitani et al. [J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105, 7771 (1983)], first synthesized a donor-acceptor system linking porphyrin (P) to two quinones (Q 1 and Q 2): Light P – Q 1 – Q 2 P* – Q 1 – Q 2 + _ P - Q 1 - Q 2 • The lifetime t of a charge-separated state of triads, tt, is long compared to the one for a dyad system td. _ + + _ P - Q 1 - Q 2 P - Q 1 τt τd τt > τd 58

Proton pump parameters: l Light intensity: I = 0. 18 m. W cm− 2 l Resonant electron tunneling rate: Δ/ћ = 15 ns-1 l Resonant proton tunneling rate: Γ/ћ = 15 ns-1 l Temperature: T = 298 K l Proton potentials: μN = - 110, μP = 110 l Diffusion coefficient of the shuttle at 298 K: Ds = 2 nm 2 μs-1 l Electron tunneling length: Ltun = 0. 5 nm l Proton tunneling length: LQ = 0. 5 nm l Dielectric constant: ε = 3 l Distances between electron sites: r. AP = r. DP = 4 nm, r. DA = 8 nm l Energy levels: EA – ES = 300 me. V, EP* - EA = 400 me. V, ED - EP = 400 me. V l Reorganization energies: λPP* = 80 me. V, λDP = λDS = λDP* = λAS = λAP = 400 me. V Ø Parameters are taken from: Nature, 392, 479 (1998); J. Am. Chem. Soc. , 123, 2607 (2001); J. Am. Chem. Soc. , 123, 6617 (2001); J. Am. Chem. Soc. , 123, 100 (2001); Angew. Chem. , Int. Ed. 41, 2344, (2002); Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. Vol. 80, No. 4, 621– 636 (2007). 59

Quantum yield versus Resonant tunneling rate 60

Quantum yield versus Dielectric constant 61

Potential energy the for shuttle motion U (x ) Aqueous layer Lipid layer Aqueous layer x 62

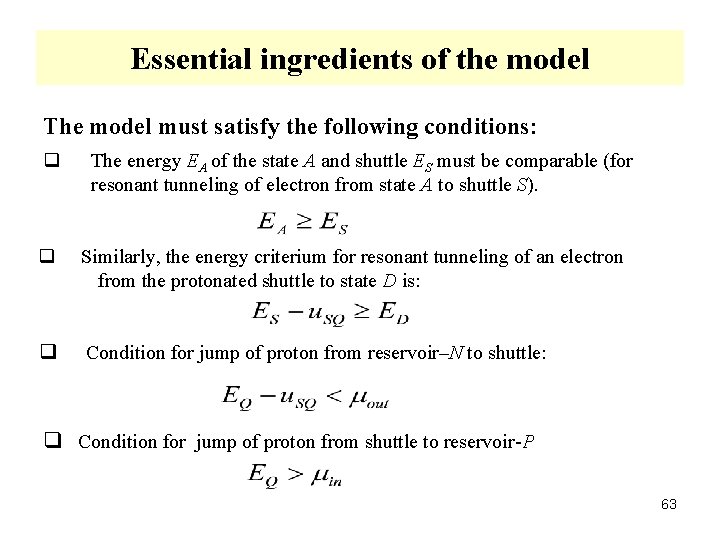

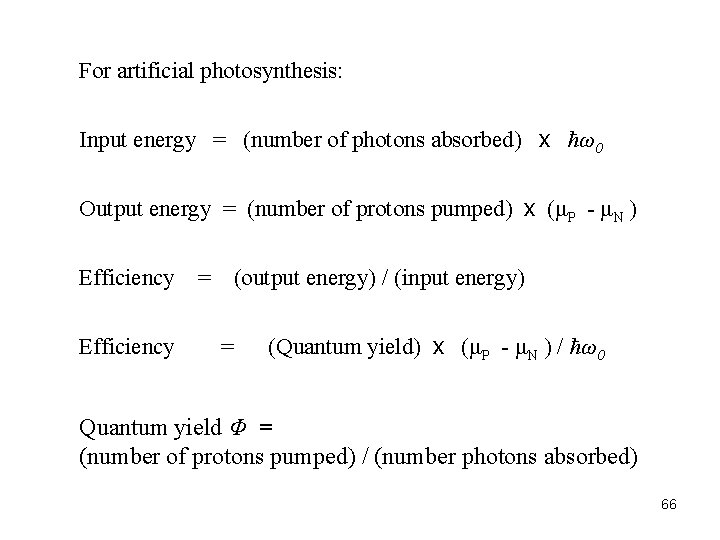

Essential ingredients of the model The model must satisfy the following conditions: q The energy EA of the state A and shuttle ES must be comparable (for resonant tunneling of electron from state A to shuttle S). q Similarly, the energy criterium for resonant tunneling of an electron from the protonated shuttle to state D is: q Condition for jump of proton from reservoir–N to shuttle: q Condition for jump of proton from shuttle to reservoir-P 63

Total Hamiltonian The Hamiltonian H 0 of the system incorporates terms relating the eigen-energies of the states and Coulomb interaction energies. • Ghosh, Smirnov, Nori, J. Chem. Phys. (2009). 64

The total Hamiltonian of the system l To remove dependency of xjk we use unitary transformation l Total Hamiltonian after unitary transform 65

For artificial photosynthesis: Input energy = (number of photons absorbed) x ћω0 Output energy = (number of protons pumped) x (μP - μN ) Efficiency = (output energy) / (input energy) = (Quantum yield) x (μP - μN ) / ћω0 Quantum yield Φ = (number of protons pumped) / (number photons absorbed) 66

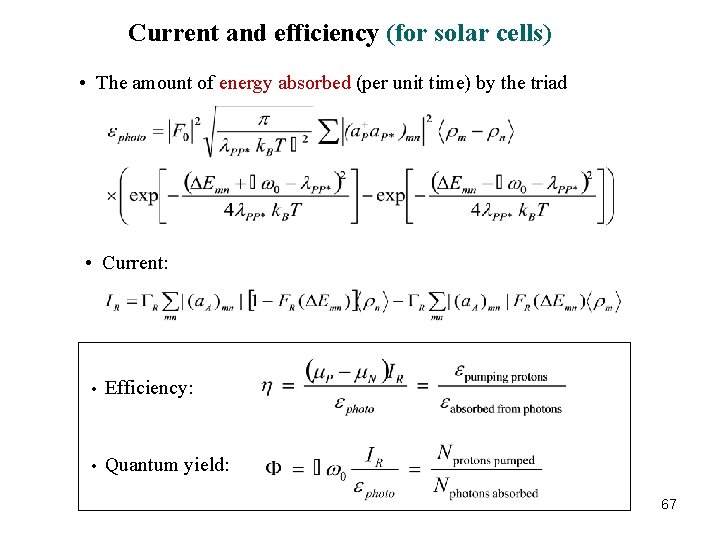

Current and efficiency (for solar cells) • The amount of energy absorbed (per unit time) by the triad • Current: • Efficiency: • Quantum yield: 67

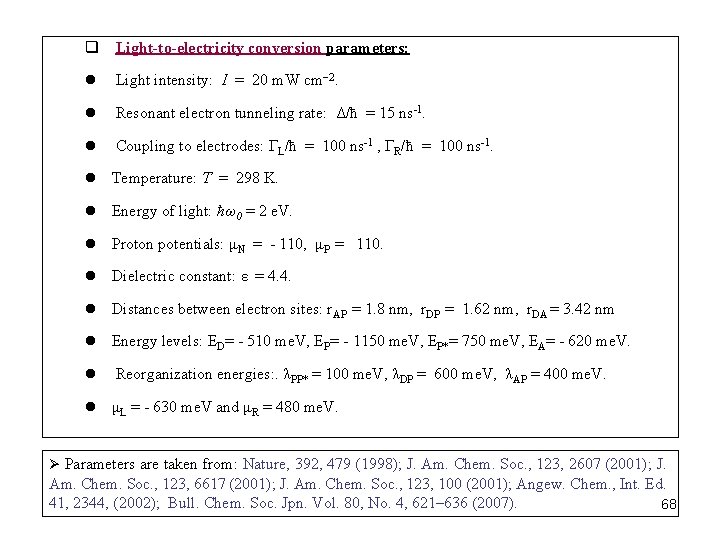

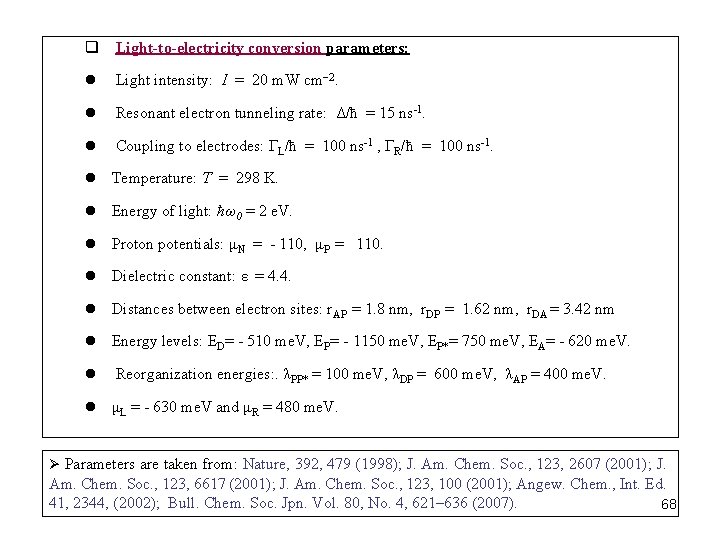

q Light-to-electricity conversion parameters: l Light intensity: I = 20 m. W cm− 2. l Resonant electron tunneling rate: Δ/ћ = 15 ns-1. l Coupling to electrodes: ΓL/ћ = 100 ns-1 , ΓR/ћ = 100 ns-1. l Temperature: T = 298 K. l Energy of light: ћω0 = 2 e. V. l Proton potentials: μN = - 110, μP = 110. l Dielectric constant: ε = 4. 4. l Distances between electron sites: r. AP = 1. 8 nm, r. DP = 1. 62 nm, r. DA = 3. 42 nm l Energy levels: ED= - 510 me. V, EP= - 1150 me. V, EP*= 750 me. V, EA= - 620 me. V. l Reorganization energies: . λPP* = 100 me. V, λDP = 600 me. V, λAP = 400 me. V. l μL = - 630 me. V and μR = 480 me. V. Ø Parameters are taken from: Nature, 392, 479 (1998); J. Am. Chem. Soc. , 123, 2607 (2001); J. Am. Chem. Soc. , 123, 6617 (2001); J. Am. Chem. Soc. , 123, 100 (2001); Angew. Chem. , Int. Ed. 41, 2344, (2002); Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. Vol. 80, No. 4, 621– 636 (2007). 68

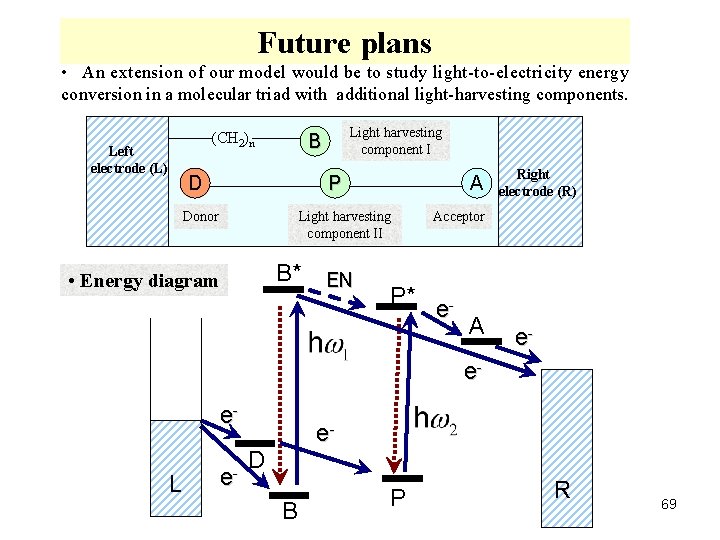

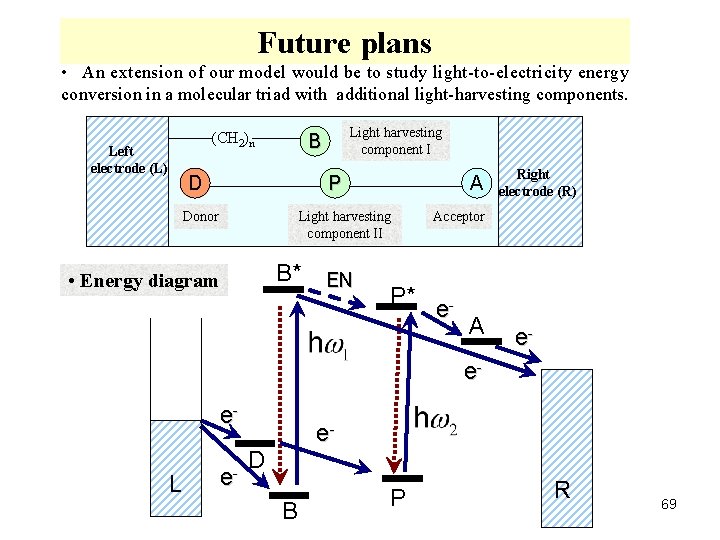

Future plans • An extension of our model would be to study light-to-electricity energy conversion in a molecular triad with additional light-harvesting components. (CH 2)n Left electrode (L) Light harvesting component I B D P Donor A Light harvesting component II B* • Energy diagram EN P* Right electrode (R) Acceptor e- A e- ee. L e- e- D B P R 69

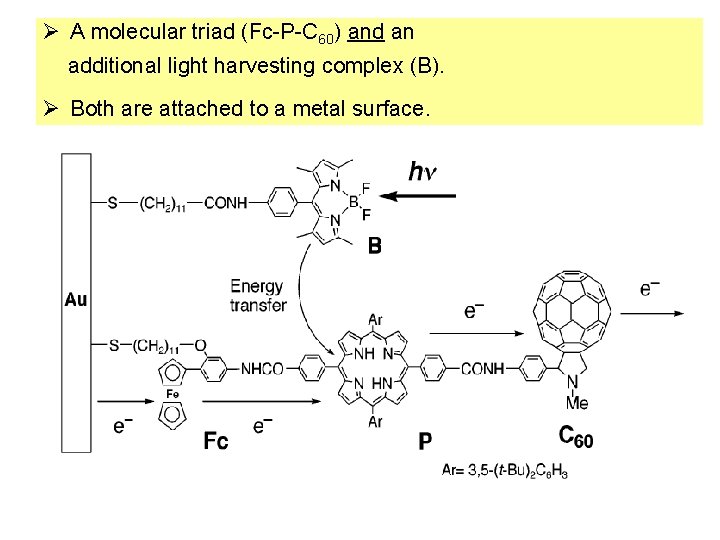

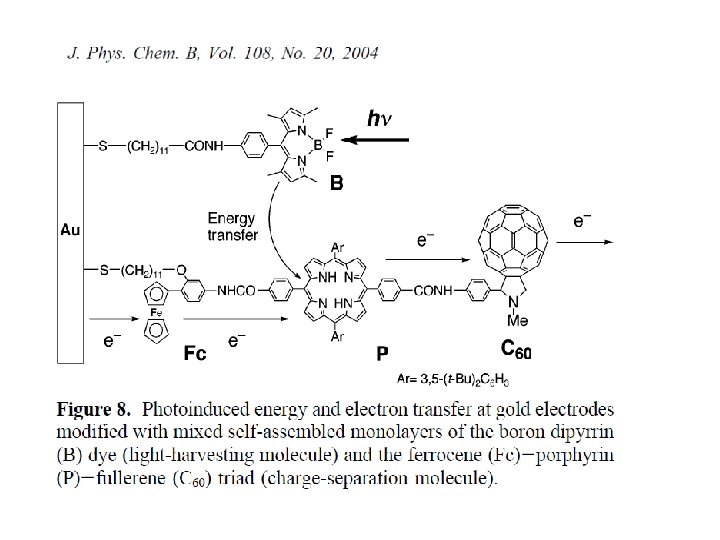

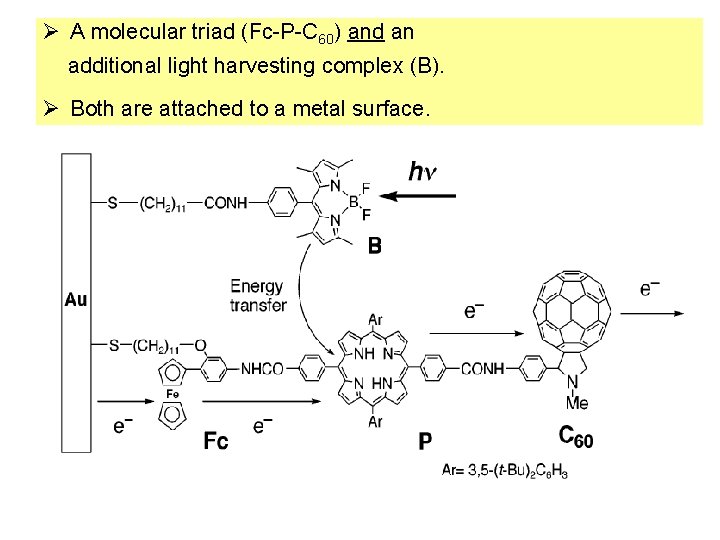

Ø A molecular triad (Fc-P-C 60) and an additional light harvesting complex (B). Ø Both are attached to a metal surface.

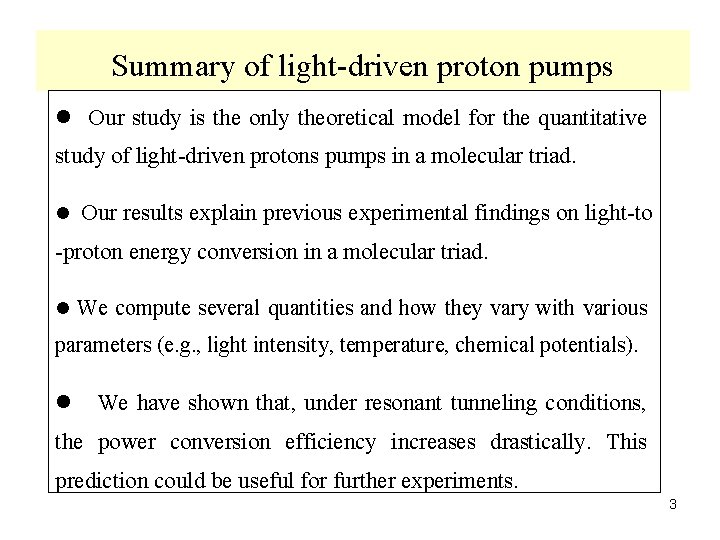

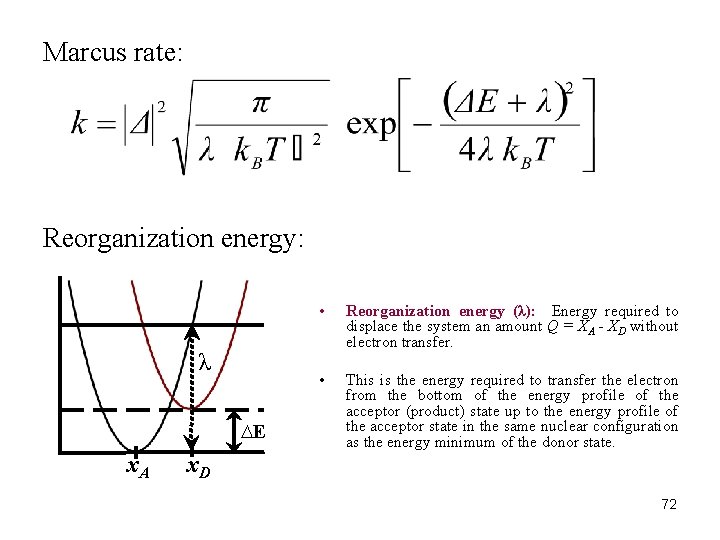

Marcus rate: Reorganization energy: λ ∆E x. A • Reorganization energy (λ): Energy required to displace the system an amount Q = XA - XD without electron transfer. • This is the energy required to transfer the electron from the bottom of the energy profile of the acceptor (product) state up to the energy profile of the acceptor state in the same nuclear configuration as the energy minimum of the donor state. x. D 72