Sodium Disorder Aisha Abu Rashed Disorders of plasma

Sodium Disorder Aisha Abu Rashed

Disorders of plasma sodium are the most common electrolyte disturbances in clinical medicine Distinguishing the cause(s) of hyponatraemia may be challenging in clinical practice, and controversies surrounding its management remain

• Under normal conditions, plasma sodium concentrations are finely maintained within the narrow range of 135 -145 mmol/l despite great variations in water and salt intake.

Sodium and its accompanying anions, principally chloride and bicarbonate, account for 86% of the extracellular fluid osmolality, which is normally 285 -295 mosm/kg and calculated as • The equation: Posm = 2 [Na+] + glucose (mg/d. L)/18 + BUN (mg/d. L)//2. 8 i • The main determinant of the plasma sodium concentration is the plasma water content, itself determined by water intake (thirst or habit), “insensible” losses (such as metabolic water, sweat), and urinary dilution •

Notes • The causes of sodium imbalance are often iatrogenic and therefore avoidable • Assessing hydration status and measuring sodium in plasma and urine are key to diagnosing the cause of hyponatraemia • The cause of hypernatraemia will usually be evident from the history

• Hyponatre mia

• Determining the cause of hyponatraemia may be straightforward if an obvious precipitating cause is vomiting or diarrhoea, when both sodium and total body water are low, and elderlytaking diuretics.

• Here, hyponatraemia almost always reflects an excess of water relative to sodium, commonly by dilution of total body sodium secondary to increases in total body water (water overload) and sometimes as a result of depletion of total body sodium in excess of concurrent body water losses

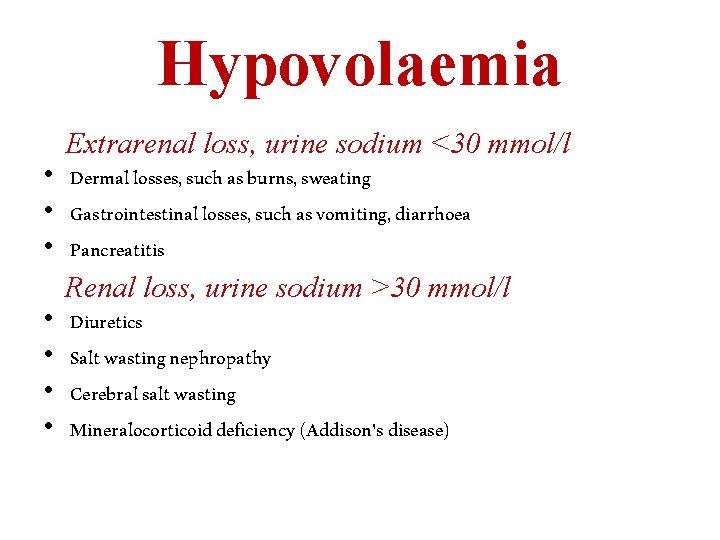

Hypovolaemia • • Extrarenal loss, urine sodium <30 mmol/l Dermal losses, such as burns, sweating Gastrointestinal losses, such as vomiting, diarrhoea Pancreatitis Renal loss, urine sodium >30 mmol/l Diuretics Salt wasting nephropathy Cerebral salt wasting Mineralocorticoid deficiency (Addison's disease)

Hyponatraemia with hypovolaemia • This is due to salt loss in excess of water loss. In this situation, ADH secretion is initially suppressed (via the hypothalamic osmoreceptors); but as fluid volume is lost, volume receptors override the osmoreceptors and stimulate both thirst and the release of ADH. This is an attempt by the body to defend circulating volume at the expense of osmolality. With extrarenal losses and normal kidneys, the urinary excretion of sodium falls in response to the volume depletion

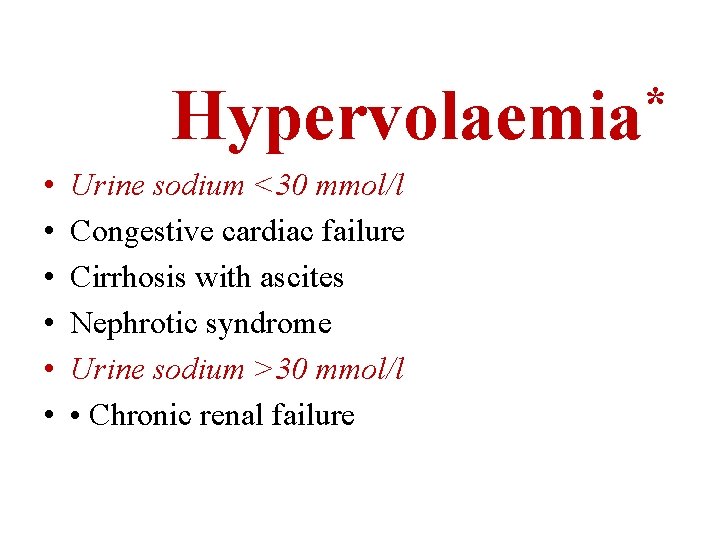

* Hypervolaemia • • • Urine sodium <30 mmol/l Congestive cardiac failure Cirrhosis with ascites Nephrotic syndrome Urine sodium >30 mmol/l • Chronic renal failure

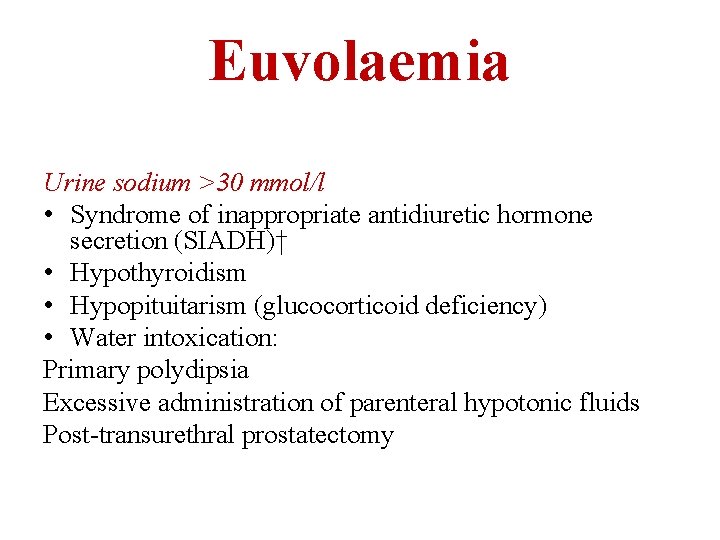

Euvolaemia Urine sodium >30 mmol/l • Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH)† • Hypothyroidism • Hypopituitarism (glucocorticoid deficiency) • Water intoxication: Primary polydipsia Excessive administration of parenteral hypotonic fluids Post-transurethral prostatectomy

• Paradoxical retention of sodium and water despite a total body excess of each; baroreceptors in the arterial circulation perceive hypoperfusion, triggering an increase in arginine vasopressin release and net water retention. • †Remember that SIADH is a diagnosis of exclusion

symptoms • Patients with mild hyponatraemia (plasma sodium 130 -135 mmol/l) are usually asymptomatic. • Nausea and malaise are typically seen when plasma sodium concentration falls below 125 -130 mmol/l. • Headache, lethargy, restlessness, and disorientation follow, as the sodium concentration falls below 115 -120 mmol/l. • With severe and rapidly evolving hyponatraemia, seizure, coma, permanent brain damage, respiratory arrest, brain stem herniation, and death may occur.

History, examination, and investigation • An accurate history may reveal a clue to the cause of the hyponatraemia and establish the rapidity of the symptoms • Plasma osmolality is almost always low in hyponatraemia,

History, examination, and investigation • • Evaluation of volume status Skin turgor Pulse rate Postural blood pressure Jugular venous pressure Consider central venous pressure monitoring General examination for underlying illness Congestive cardiac failure , Cirrhosis, Nephrotic syndrome, Addison's disease , Hypopituitarism Hypothyroidism

History, examination, and investigation • • Investigations Urinary sodium Plasma glucose and lipids* Renal function Thyroid function Peak cortisol during short synacthen test† Plasma and urine osmolality‡ If indicated: chest x ray, and computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of head and thorax

• Pseudohyponatraemia due to artefactual reduction in = hyperlipidemia +hyperprotenmia. artificially lowers the plasma sodium concentration measurement via laboratory artifact, but the amount of sodium in plasma is normal • Pseudohyponatremia = ====This occurs in hyperlipidaemia or hyperproteinaemia where there is a spuriously low measured sodium concentration, the sodium being confined to the aqueous phase but having its concentration expressed in terms of the total volume of plasma. In this situation, plasma osmolality is normal and therefore treatment of ‘hyponatraemia’ is unnecessary • hyperglycaemia causes true hyponatraemia, irrespective of laboratory method. • For SIADH: plasma osmolality < 270 mosm/kg with inappropriate urinary concentration (> 100 mosm/kg), in a euvolaemic patient after exclusion of hypothyroidism and glucocorticoid deficiency).

Hyponatraemia with hypervolaemia The common causes of hyponatraemia due to water excess. there is usually an element of reduced glomerular filtration rate with avid reabsorption of sodium and chloride in the proximal tubule. This leads to reduced delivery of chloride to the ‘diluting’ ascending limb of Henle’s loop and a reduced ability to generate ‘free water’, with a consequent inability to excrete dilute urine. This is commonly compounded by the administration of diuretics that block chloride reabsorption and interfere with the dilution of filtrate either in Henle’s loop (loop diuretics) or distally (thiazides).

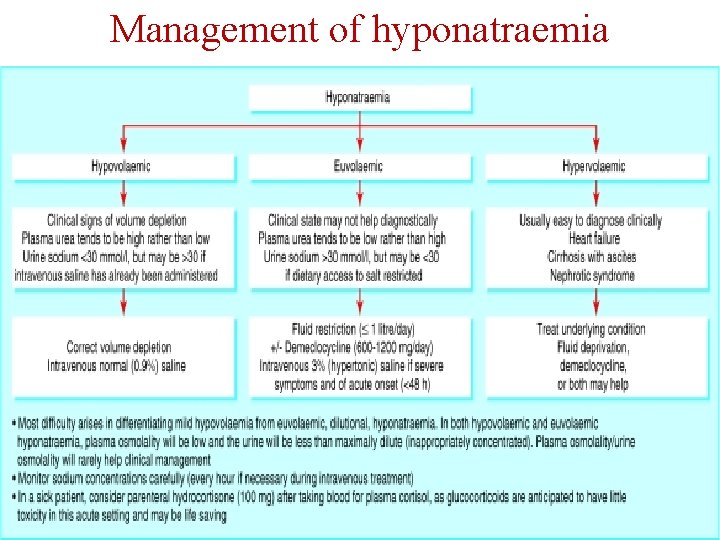

Management of hyponatraemia

Management of hyponatraemia Treatment This is directed at the primary cause whenever possible. In a healthy patient: # Give oral electrolyte-glucose mixtures # Increase salt intake with slow sodium 60– 80 mmol/day. In a patient with vomiting or severe volume depletion: # Give intravenous fluid with potassium supplements, i. e. 1. 5– 2 L 5% glucose (with 20 mmol K+ ) and 1 L 0. 9% saline over 24 h PLUS measurable losses

Management of hyponatraemia Hyponatraemia with euvolaemia # The most common iatrogenic cause is overgenerous infusion of 5% glucose into postoperative patients; in this situation it is exacerbated by an increased ADH secretion in response to stress. # Postoperative hyponatraemia is a common clinical problem (almost 1% of patients) with symptomatic hyponatraemia occurring in 20% of these patients. # Marathon runners drinking excess water and ‘sports drinks’ can become hyponatraemic. # Premenopausal females are at most risk for developing hyponatraemic encephalopathy postoperatively, with postoperative ADH values in young females being 40 times higher than in young males

demeclocycline • It is widely used (though off-label in many countries including the United States) in the treatment of hyponatremia (low blood sodium concentration) due to the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) when fluid restriction alone has been ineffective. Physiologically, this works by reducing the responsiveness of the collecting tubule cells to ADH. • The use in SIADH actually relies on a side effect; demeclocycline induces nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (dehydration due to the inability to concentrate urine. • Demeclocycline used to be the drug of choice for treating SIADH. [13] Meanwhile it might be superseded, now that vasopressin receptor antagonists, such as tolvaptan, became available

Management of hyponatraemia • Symptoms and their severity should guide the treatment strategy Acute hyponatraemia developing within 48 hours carries a risk of cerebral oedema, so prompt treatment is indicated with apparently small risk of central pontine myelinolysis. A rapid rise in extracellular osmolality, particularly if there is an ‘overshoot’ to high serum sodium and osmolality, will result in the osmotic demyelination, syndrome (ODS====central pontine demyelination • This is presumed to occur if the blood-brain barrier becomes permeable with rapid correction of hyponatraemia and allows complement mediated oligodendrocyte toxicity. Alcoholics with malnutrition, premenopausal or elderly women on thiazide diuretics, and patients with hypokalaemia or burns are at increased risk of central pontine myelinolysis.

Osmotic Demylination syndrome in the phase of rapid correction of hyponatraemia, resulting in an hypo-osmolar intracellular compartment and lead to shrinkage of cerebral vascular endothelial cells. Consequently the blood–brain barrier is functionally impaired, allowing lymphocytes, complement, and cytokines to enter the brain, damage oligodendrocytes, activate microglial cells and cause demyelination.

Management of hyponatraemia • Neurological injury is typically delayed for two to six days after elevation of the sodium concentration, but the symptoms, which include dysarthria, dysphagia, spastic paraparesis, lethargy, seizures, coma, and even death, are generally irreversible, so prevention is key. • raising the sodium concentration by 1 -2 mmol/l per hour until symptoms have resolved, with close monitoring of plasma sodium • Therefore, the rate of correction should not exceed 12 m. Eq/L/day (should be <8 m. Eq/L in the first 24 hours).

Management of hyponatraemia In general, the plasma sodium should not be corrected to >125– 130 mmol/L. 1 m. L/kg of 3% sodium chloride will raise the plasma sodium by 1 mmol/L, assuming that total body water comprises 50% of total bodyweight. # Symptomatic hyponatraemia in patients with intracranial pathology should be managed aggressively and immediately with 3% saline like acute hyponatraemia

Hyponatremia Risk factors for developing hyponatraemic encephalopathy. The brain’s adaptation to hyponatraemia initially involves extrusion of blood and CSF, as well as sodium, potassium and organic osmolytes, in order to decrease brain osmolality. Various factors can interfere with successful adaptation. These factors rather than the absolute change in serum sodium predict whether a patient will suffer hyponatraemic encephalopathy. # Children under 16 years are at increased risk due to their relatively larger brain-to-intracranial volume ratio compared with adults.

Hyponatremia

Hyponatremia # To prevent hyponatraemia, avoid using hypotonic fluids postoperatively and administer 0. 9% saline unless otherwise clinically contraindicated. # The serum sodium should be measured daily in any patient receiving continuous parenteral fluid. # Some degree of hyponatraemia is usual in acute oliguric kidney injury, while in chronic kidney disease (CKD) it is most often due to ill-given advice to ‘push’ fluids

Hyponatremia # Chronic/asymptomatic. If hyponatraemia has developed slowly, as it does in the majority of patients, the brain will have adapted by decreasing intracellular osmolality and the hyponatraemia can be corrected slowly (without use of hypertonic saline). # However, clinically it can be difficult to know how long the hyponatraemia has been present and 3% of hypertonic saline is still required.

• Hypernatremia

Hypernatremia • Hypernatraemia = reflects a water loss or a hypertonic sodium gain, , hyperosmolality. • Severe symptoms are usually evident only with acute and large increases in plasma sodium concentrations to above 158 -160 mmol/l.

• Importantly, the sensation of intense thirst that protects against severe hypernatraemia in health may be absent or reduced in patients with altered mental status or with hypothalamic lesions affecting their sense of thirst (adipsia) and in infants and elderly people. Non-specific symptoms such as anorexia, muscle weakness, restlessness, nausea, and vomiting tend to occur early. • More serious signs follow, with altered mental status, lethargy, irritability, stupor, or coma. Acute brain shrinkage can induce vascular rupture, with cerebral bleeding and subarachnoid haemorrhage.

History, examination, and investigation • • Measurement of urine osmolality plasma osmolality and the urine sodium concentration

Box 3: Classification of hypernatraemia Hypovolaemia • • • Dermal losses—for example, burns, sweating Gastrointestinal losses—for example, vomiting, diarrhoea, fistulas Diuretics Postobstruction Acute and chronic renal disease Hyperosmolar non-ketotic coma*

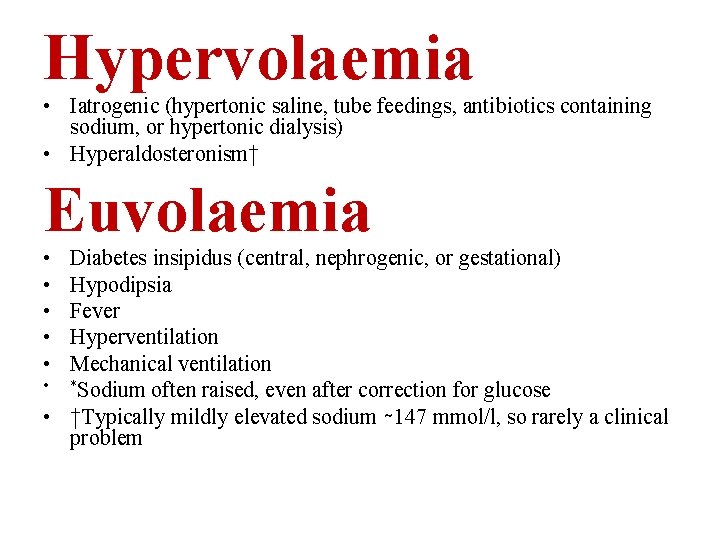

Hypervolaemia • Iatrogenic (hypertonic saline, tube feedings, antibiotics containing sodium, or hypertonic dialysis) • Hyperaldosteronism† Euvolaemia • • • Diabetes insipidus (central, nephrogenic, or gestational) Hypodipsia Fever Hyperventilation Mechanical ventilation • *Sodium often raised, even after correction for glucose • †Typically mildly elevated sodium ∼ 147 mmol/l, so rarely a clinical problem

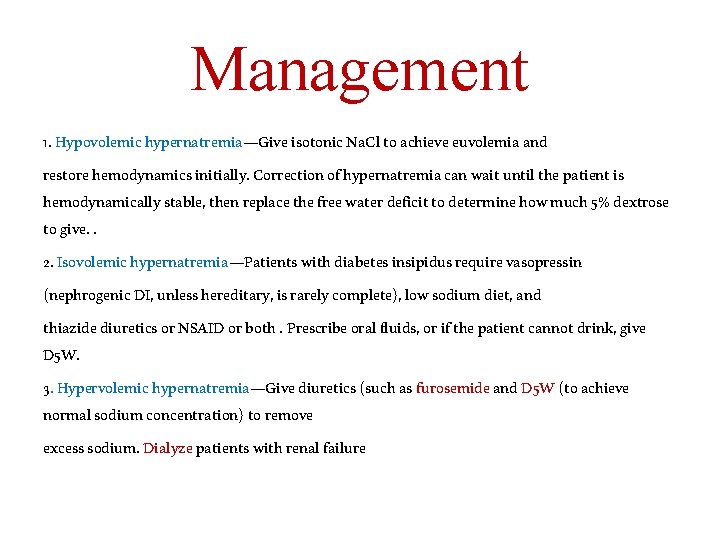

Management 1. Hypovolemic hypernatremia—Give isotonic Na. Cl to achieve euvolemia and restore hemodynamics initially. Correction of hypernatremia can wait until the patient is hemodynamically stable, then replace the free water deficit to determine how much 5% dextrose to give. . 2. Isovolemic hypernatremia—Patients with diabetes insipidus require vasopressin (nephrogenic DI, unless hereditary, is rarely complete), low sodium diet, and thiazide diuretics or NSAID or both. Prescribe oral fluids, or if the patient cannot drink, give D 5 W. 3. Hypervolemic hypernatremia—Give diuretics (such as furosemide and D 5 W (to achieve normal sodium concentration) to remove excess sodium. Dialyze patients with renal failure

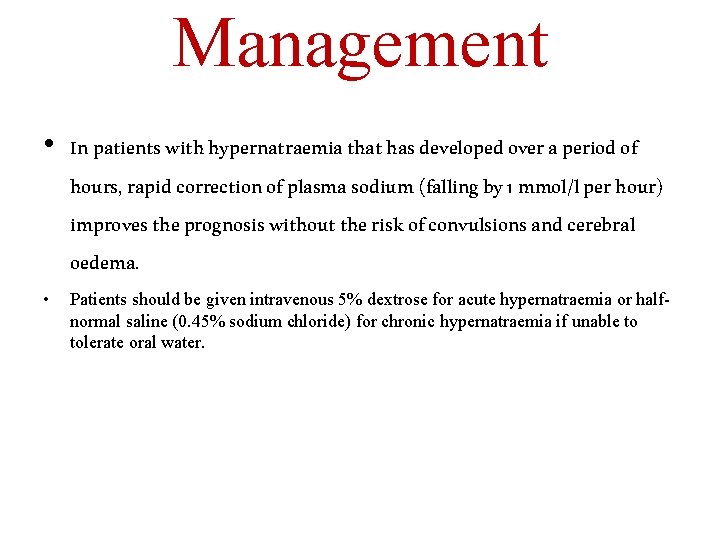

Management • In patients with hypernatraemia that has developed over a period of hours, rapid correction of plasma sodium (falling by 1 mmol/l per hour) improves the prognosis without the risk of convulsions and cerebral oedema. • Patients should be given intravenous 5% dextrose for acute hypernatraemia or halfnormal saline (0. 45% sodium chloride) for chronic hypernatraemia if unable to tolerate oral water.

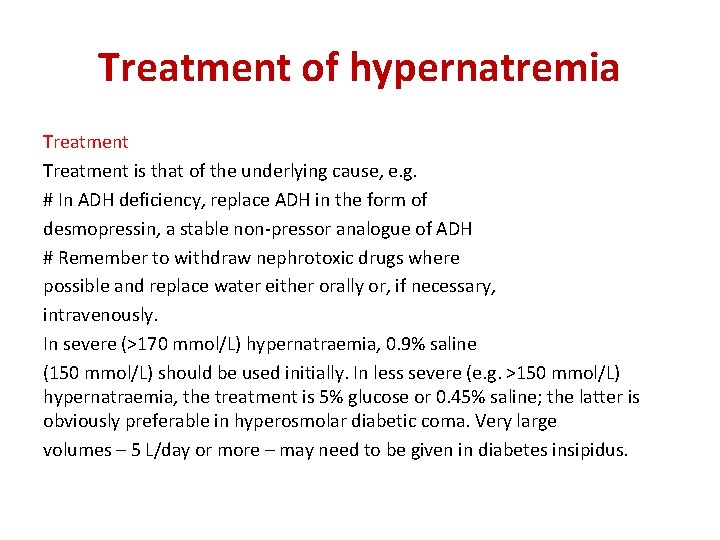

Treatment of hypernatremia Treatment is that of the underlying cause, e. g. # In ADH deficiency, replace ADH in the form of desmopressin, a stable non-pressor analogue of ADH # Remember to withdraw nephrotoxic drugs where possible and replace water either orally or, if necessary, intravenously. In severe (>170 mmol/L) hypernatraemia, 0. 9% saline (150 mmol/L) should be used initially. In less severe (e. g. >150 mmol/L) hypernatraemia, the treatment is 5% glucose or 0. 45% saline; the latter is obviously preferable in hyperosmolar diabetic coma. Very large volumes – 5 L/day or more – may need to be given in diabetes insipidus.

Calculation of Maintenance Fluids 100/50/20 rule: 100 m. L/kg for first 10 kg, 50 m. L/kg for next 10 kg, 20 m. L/kg for every 1 kg over 20 Divide total by 24 for hourly rate For example, for a 70 kg man: 100 × 10 = 1, 000; 50 × 10 = 500, 20 × 50 kg = 1, 000. Total = 2, 500. Divide by 24 hours: 104 m. L/hr 4/2/1 rule: 4 m. L/kg for first 10 kg, 2 m. L/kg for next 10 kg, 1 m. L/kg for every 1 kg over 20 For example, for a 70 kg man: 4 × 10 = 40; 2 × 10 = 20; 1 × 50 = 50. Total = 110 m. L/hr

- Slides: 41