Social Behavior Sociocultural context We argued that all

Social Behavior

Sociocultural context • We argued that all human behavior is cultural to some extent. This is because the human species is fundamentally a social one. • Our intimate and prolonged interpersonal relations promote the development of shared meanings, and the creation of institutions and artifacts. • To understand our social nature, and how it is organized, we need to examine some basic features of society.

Sociocultural context • On the one hand, social behaviors are obviously linked to the particular sociocultural context in which they develop; for example, greeting procedures (bowing, handshaking, or kissing) vary widely from culture to culture, and these are clear-cut examples of the influence of cultural transmission on our social behavior.

Sociocultural context • On the other hand, greeting takes place in all cultures, suggesting the presence of some fundamental communality in the very essence of social behavior. • If there are difficulties in transporting theories, methods, and findings from the United States to, for example, Israel and Canada, how much more likely are there to be problems when larger cultural contrasts are involved?

Sociocultural context • One solution is to create indigenous (yerel) social psychologies. • These attempt to develop social psychologies that are appropriate to a particular society or region.

Sociocultural context • In every social system individuals occupy positions for which certain behaviors are expected; these behaviors are called roles. • Each role occupant is the object of sanctions that exert social influence, even pressure, to behave according to social norms or standards. • These elements of a social system are not random, but are organized or structured by each cultural group.

Sociocultural context • Societies make distinctions among roles; some societies make few, while others make many. • For example, in a relatively undifferentiated (farklılaşmamış) social structure positions and roles may be limited to a few basic familial, social, and economic ones. • Such as parent–child, hunter–food preparer. • There is minimal role diversity.

Sociocultural context • In contrast, in a relatively more differentiated societies, there are many more positions and roles to be found in particular domains. • Such as king–aristocracy–citizen–slave, corporate owner–manager–worker–retiree, or pope–cardinal–bishop–priest–layperson. • There is more role diversity.

Sociocultural context • Fiske (1993) proposed four elementary relational structures: – Communal sharing: where people are merged, boundaries of individual selves are indistinct, people attend to group membership and have a sense of common identity. – Authority ranking: where inequality and hierarchy prevail, highly ranked persons control people, things, and resources.

Sociocultural context • Fiske (1993) proposed four elementary relational structures: – Equality matching: where there are egalitarian relations among peers; people are separate but equal, engaging in turn-taking, reciprocity, and balanced relationships. – Market pricing: actions are evaluated according to the rates at which they can be exchanged for other commodities (metalar).

Sociocultural context • «These models are fundamental, in that they are in some sense the lowest or most basic level “grammars” for social relations. My hypothesis is that these models are general, giving order to most forms of social interaction, thought, and affect. They are elementary, in the sense that they are the basic constituents for all higher order social forms. My hypothesis is that they are also universal, being the basis for social relations among all people in all cultures and the essential foundation for cross-cultural understanding and intercultural engagement. »

Conformity • Without some degree of conformity, it is quite likely that social cohesiveness would be so minimal that the group could not continue to function as a group. • There appears to be variation across cultures in the degree to which individuals are raised or trained to be independent and self- (as opposed to group-)reliant.

Conformity • There is likely to be relatively more individual conformity in societies that emphasize compliance training (i. e. , densely populated and highly stratified-tabakalaşma- societies), and relatively less in societies that stress assertion training (i. e. , sparse and unstratified societies).

Conformity • Researchers studying conformity have usually investigated the tendency of individuals to be influenced by what they believe to be the judgments of a group. • Asch’s experiment: https: //amara. org/kn/videos/q. Sk 79 dwvr. Vxx/tr/9569 19/

Conformity • Conformity was likely to be found across cultures, but would vary according to ecological and cultural factors. • Hunting-based peoples, with loose forms of social organization (low societal conformity) and socialization for assertion, would exhibit lower levels of conformity than those in agricultural societies, with tighter social organization and socialization for compliance.

Values • In an early definition, the term “values” refers to a conception held by an individual, or collectively by members of a group, of that which is desirable, and which influences the selection of both means and ends of action from among available alternatives. • More recently, values are defined as “a broad tendency to prefer certain states of affairs over others”

Values • Values are usually considered to be more general in character than attitudes, but less general than ideologies (such as political systems). • They appear to be relatively stable features of individuals and societies.

Values • Rokeach identified eighteen values of each kind, and his instrument (the Rokeach Value Survey) requires respondents to rank order the values within each set of eighteen. • Terminal values were defined as idealized end states of existence. • These are the goals that a person would like to achieve during his or her lifetime. These values vary among different groups of people in different cultures.

Values Terminal Values • True Friendship • Mature Love • Self-Respect • Happiness • Inner Harmony • Equality • Freedom • Pleasure • Social Recognition • • • Wisdom Salvation Family Security National Security A Sense of Accomplishment A World of Beauty A World at Peace A Comfortable Life An Exciting Life

Values • Instrumental values were defined as idealized modes of behavior used to attain the end states. • These are preferable modes of behavior, or means of achieving the terminal values.

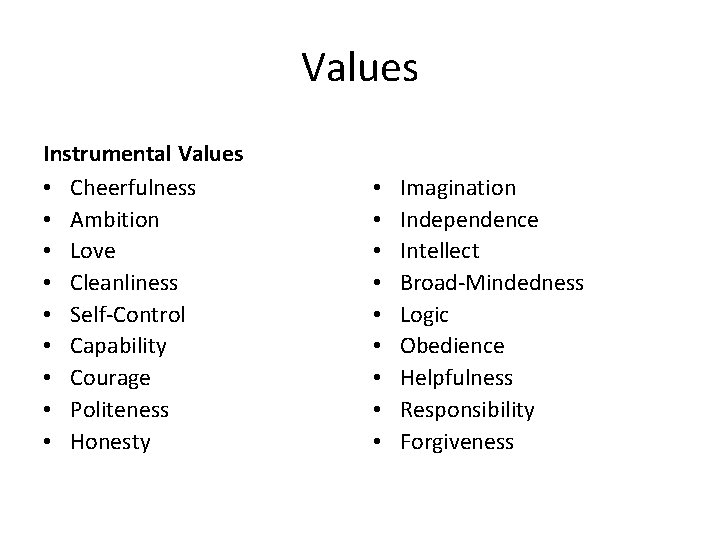

Values Instrumental Values • Cheerfulness • Ambition • Love • Cleanliness • Self-Control • Capability • Courage • Politeness • Honesty • • • Imagination Independence Intellect Broad-Mindedness Logic Obedience Helpfulness Responsibility Forgiveness

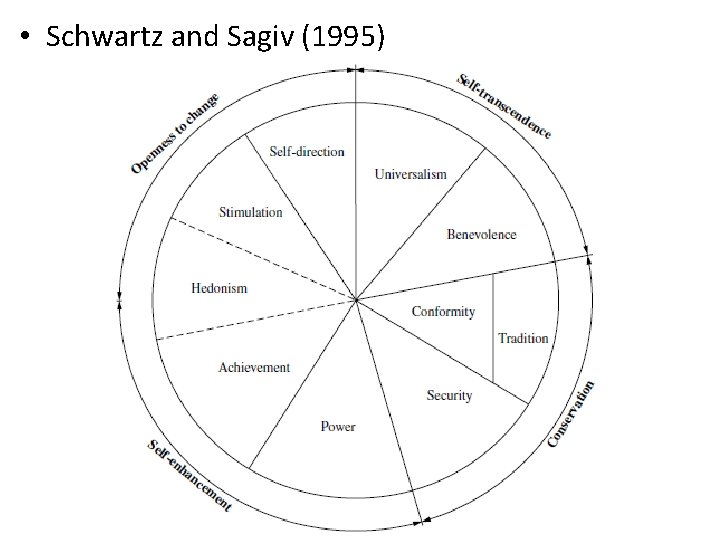

• Schwartz and Sagiv (1995)

Values • There are two dimensions that organize the ten value types into clusters situated at either end of the two dimensions. • These dimensions are: – self-enhancement (power, achievement, hedonism) versus self-transcendence (universalism, benevolence); – conservatism (conformity, security, tradition) versus openness to change (self-direction, stimulation).

Values • These two dimensions (and ten values) are considered to represent universal aspects of human existence, which are rooted in basic individual needs. • Individual scores can be aggregated (toplanma) over individuals within a group (culture or country) to yield a score that is thought to be characteristic of the group.

Values • Conservatism versus autonomy: how individuals relate to their group (whether they are embedded or independent). • Hierarchy versus egalitarianism: how people consider the welfare of others (whether relationships are vertically or horizontally structured). • Mastery versus harmony: the relationship of people to their natural and social world (whether they dominate and exploit it, or live with it).

Values • The World Values Survey: This has been carried out three times since 1981; it has sampled values from individuals in sixty-five countries containing over 75 percent of the world population. • Using a wide range of items, Inglehart and Baker (2000) found two basic value dimensions, which they labeled traditional versus secular-rational, and survival versus self-expression.

Values • Traditional versus secular-rational: values that emphasize obedience rather than independence when raising children as well as respect for authority. • Survival versus self-expression: values that emphasize economic and physical security over quality of life.

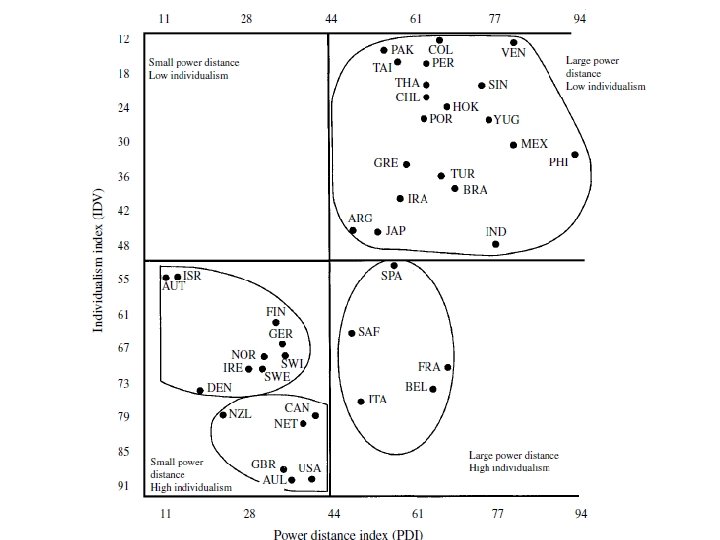

Values • Hofstede worked for a major international corporation, and was able to administer over 116, 000 questionnaires (in 1968 and in 1972) to employees in fifty different countries and of sixty-six different nationalities.

Values • Power distance: the extent to which there is inequality (a pecking order) between supervisors and subordinates in an organization. • Uncertainty avoidance: the lack of tolerance for ambiguity, and the need formal rules. • Individualism: a concern for oneself as opposed to concern for the collectivity to which one belongs. • Masculinity: the extent of emphasis on work goals (earnings, advancement) and assertiveness, as opposed to interpersonal goals (friendly atmosphere, getting along with the boss) and nurturance.

Individualism and collectivism • The defining difference between individualism and collectivism is a primary concern for oneself in contrast to a concern for the groups(s) to which one belongs.

Individualism and collectivism • In-group solidarity – Teenagers should listen to their parents’ advice on dating. (C) – I would not share my ideas and newly acquired knowledge with my parents. (I) – The decision of where one is to work should be jointly made with one’s spouse. (C) – Even if the child won the Nobel prize, the parents should not feel honored in any way. (I) – I like to live close to my good friends. (C) – To go on a trip with friends makes one less free and mobile; as a result there is less fun. (I)

Individualism and collectivism • Social obligation – I can count on my relatives for help if I find myself in any kind of trouble. (C) – Each family has its own problems unique to itself. It does not help to tell relatives about one’s problems. (I) – I enjoy meeting and talking to my neighbors every day. (C) – I am not interested in knowing what my neighbors are really like. (I)

Social cognition • How individuals perceive and interpret their social world, an area now known as social cognition. • Attribution refers to the way in which individuals think about the causes of their own, or other people’s, behavior. • People can attribute behaviors to internal causes (i. e. , to their own actions and dispositions), or to external causes (i. e. , not to themselves but to others or to fate).

Social cognition • There is a frequently observed preference for attributions to internal dispositions, especially when it comes to the behavior of others, that has become known as the “fundamental attribution error”. • Both dispositional and situational attributions were present across cultures, but were used differentially.

Social cognition • In particular, Western (European) peoples prefer to make dispositional attributions, while East Asian peoples prefer situational (contextual) ones when interpreting human behavior.

Gender behavior • We said that girls generally are socialized more toward compliance (nurturance, responsibility, and obedience), while boys are raised more for assertion (independence, selfreliance, and achievement). • These differential socialization patterns are themselves related to some other cultural factors (such as social stratification) and ecological factors (such as subsistence economy and population density).

Gender behavior • Biological, cultural, and transmission variables are related to differential gender behavior. • At birth, a neonate (yenidoğan) has a sex, but no gender. • At birth, one’s biological sex can usually be decided on the basis of physical anatomical evidence; but culturally rooted experiences, feelings, and behaviors that are associated by adults with this biological distinction are a major influence on how individuals see their gender.

Gender behavior • How males and females differ, and how they are similar, will be interpreted as a cultural construction on a biological foundation, rather than as a biological given. • Values, cultural beliefs (stereotypes), and expectations (ideology) lead to male–female differences in socialization, role differentiation and assignment, and eventually to differences in a number of psychological characteristics (abilities, aggression, etc. ).

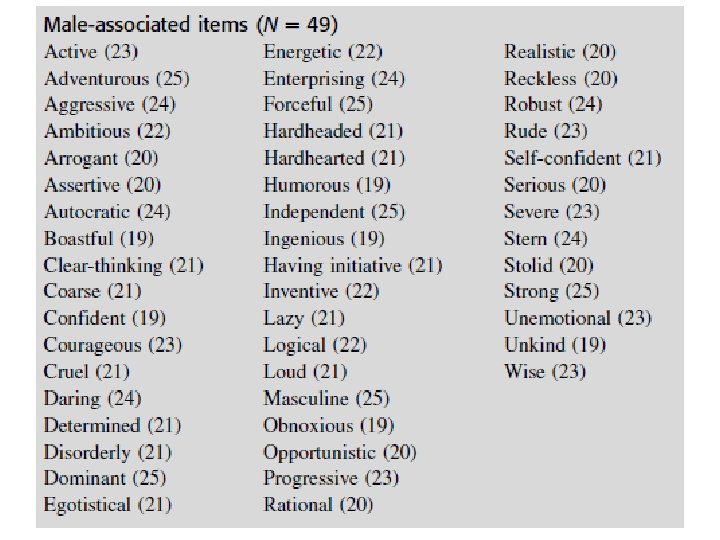

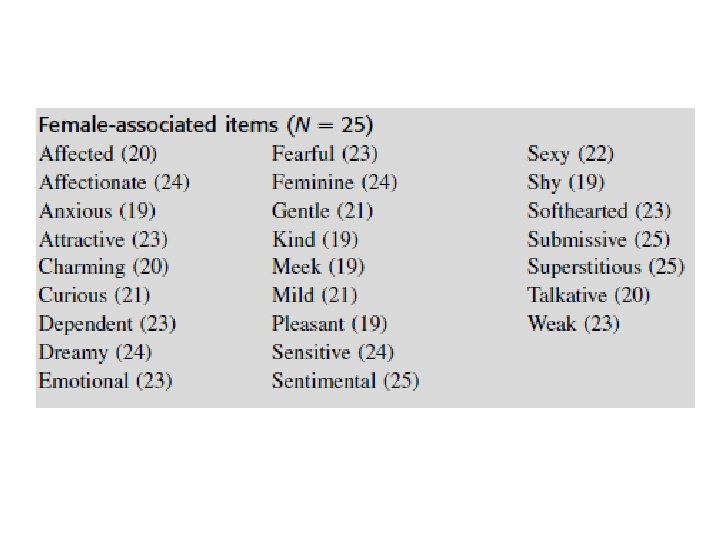

Gender behavior • Gender stereotypes • Stereotypes of males and females are very different from one another, with males usually viewed as dominant, independent, and adventurous and females as emotional, submissive, and weak.

Gender behavior • A total of 2, 800 persons, ranging between 52 to 120 respondents per country, and usually close to an equal number of males and females were investigated. • Results indicated a large-scale difference in the views about what males and females were like in all countries, and a broad consensus across countries.

Gender behavior • This degree of consensus was so large that it may be appropriate to suggest that the researchers had found psychological universals when it comes to gender stereotypes.

Gender behavior • Mate selection • Using a questionnaire with around 10, 000 respondents in thirty-seven countries, Buss first asked them to rate each of – (1)eighteen characteristics (on a four-point scale) as important or desirable in choosing a mate. – (2)to rank thirteen characteristics for their desirability in choosing a mate.

Gender behavior • There was widespread agreement in preferences. • Both males and females chose the same qualities in the first four places: – being kind and understanding, – intelligent, – having an exciting personality, – being healthy.

Gender behavior • However, within this overall similarity, both gender and cultural differences were observed. • The main gender difference was for females to value potential earnings more highly than males, and for males to value physical appearance more highly than females.

Gender behavior • The cultural differences were widespread, with chastity (bekaret) showing the largest cross-cultural variance, being valued less in northern Europe than in Asia. • Despite these cultural and sexual variations, there were strong similarities among cultures and between sexes on the preference ordering of mate selection.

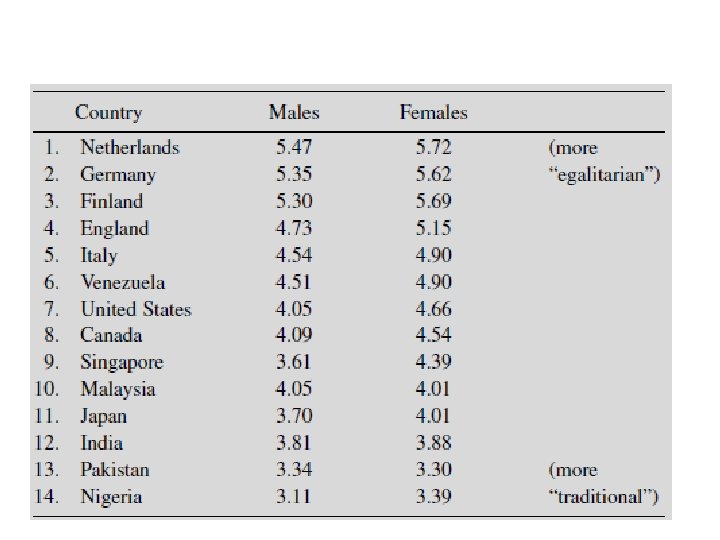

Gender behavior • Gender role ideology is a normative belief about what males and females should be like, or should do. • According to Kalin and Tilby (1978), scores ranging between “traditional” and “egalitarian. ” • In general, the more egalitarian scores were obtained in countries with relatively high socioeconomic development.

Gender behavior • Traditional ideology are: – When a man and woman live together she should do the housework and he should do the heavier chores. – A woman should be careful how she looks, for it influences what people think of her husband. – The first duty of a woman with young children is to home and family.

Gender behavior • For the egalitarian ideology sample items were: – A woman should have exactly the same freedom of action as a man. – Marriage should not interfere with a woman’s career any more than it does with a man’s. – Women should be allowed the same sexual freedom as men.

Gender behavior • Psychological characteristics • Differences in psychological characteristics between men and women. • Three behavioral domains: – perceptual-cognitive abilities, – conformity, – aggression.

Gender behavior • Perceptual-cognitive abilities: It has been a common claim that on spatial tasks (and those tasks that have a spatial component) males tend to perform better than females. • But spatial abilities were highly adaptive for both males and females in Inuit (Eskimo) society, and both boys and girls had ample (bol) training and experiences that promoted the acquisition of spatial ability. • Those with poor spatial abilities are likely to die in hunting societies, and their genes thus be eliminated.

Gender behavior • Conformity: In the Western literature there is some evidence that females may be more susceptible to conformity pressures than males. • But this has been the subject of heated controversy.

Gender behavior • Aggression: On the average, males (particularly adolescents) quite consistently commit more acts of aggression than do females. • Evidence that testosterone levels are linked with dominance striving is available but more for primates like baboons than for humans. • There is also evidence that testosterone levels are linked to antisocial behavior in delinquent populations.

Gender behavior • The degree to which the expression of aggression is tolerated (or even encouraged) is influenced by the sociocultural environment. • If males and females have different experiences that impact on their tendencies to behave aggressively, then knowing what those experiences are is necessary in any attempt to understand aggression.

Gender behavior • Aggression is seen partly as gender-marking behavior. • Young boys develop a cross-sex identity which later is corrected either by severe male initiation ceremonies for adolescent males or by individual efforts by males to assert their manliness.

- Slides: 58