Social accountability of medical schools The primary goal

Social accountability of medical schools

The primary goal of undergraduate medical education (UME) : to create a doctor who is broadly educated across the key competencies of medicine and who has the knowledge and clinical skills to enter graduate training

It is difficult to accomplish this goal : In traditional fragmented and highly specialized clinical environments in which medical student education competes with: resident education research clinical productivity

o. Over the years, the WHO and other organizations have advocated that doctors consciously adopt new roles to become more active in health development, particularly through primary health care o. They have insisted on the need for new physicians to acquire new competencies: ? ? ?

Care provider Manager Community leader Decisionmaker Communicator

ØHowever, too few medical schools have acted to recast their educational programs accordingly ØAs a result, a mismatch has persisted between what is being taught and learned in medical schools and what is expected from future doctors in their health systems ØTraditional medical education in high- and low-income countries emphasize : Biomedical disease-oriented model Øalone does not fully address today’s public health need, and often lacks firm social mandates

Definition of Social accountability of medical schools

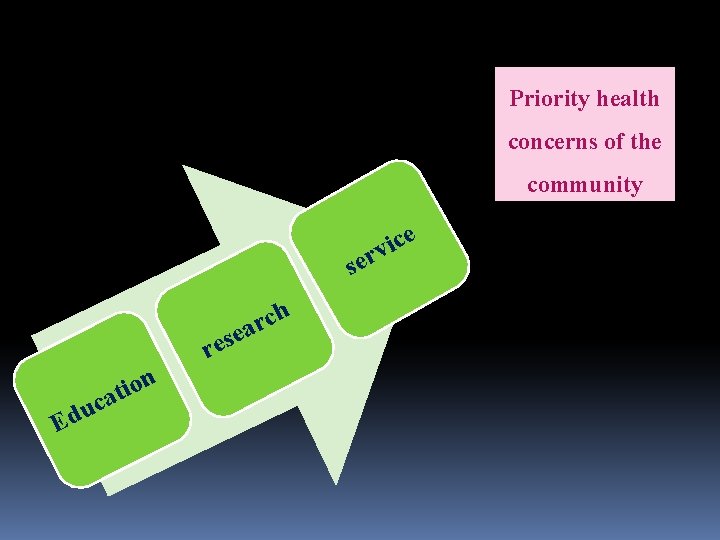

Priority health concerns of the community e c i rv se h c r ea res Ed n o i t uca

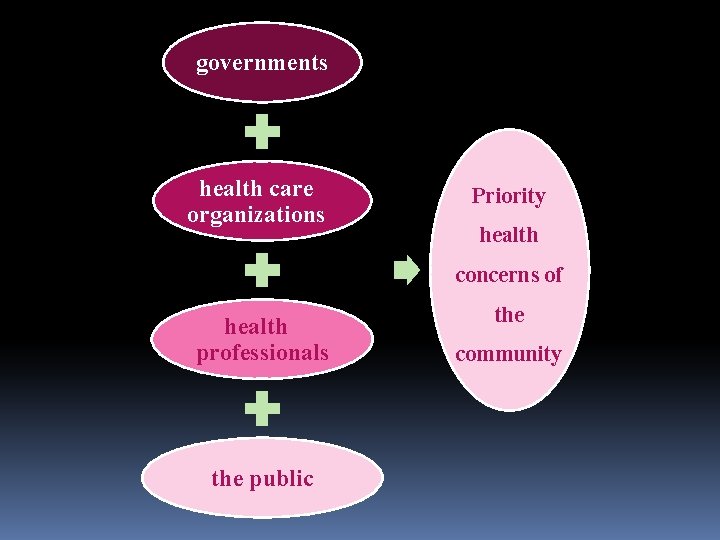

governments health care organizations Priority health concerns of health professionals the public the community

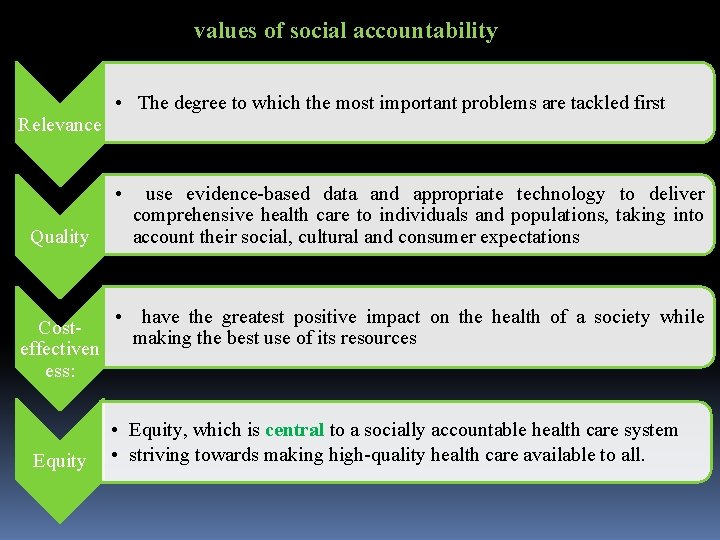

values of social accountability Relevance • The degree to which the most important problems are tackled first • Quality Costeffectiven ess: Equity use evidence-based data and appropriate technology to deliver comprehensive health care to individuals and populations, taking into account their social, cultural and consumer expectations • have the greatest positive impact on the health of a society while making the best use of its resources • Equity, which is central to a socially accountable health care system • striving towards making high-quality health care available to all.

Criteria to determine the social accountability of a medical school v The extent to which the school’s guiding principles are community orientated v. The emphasis placed in the curriculum on concepts and knowledge of what constitutes a community and a population, how to measure and cope with health needs and how to take proper account of the cultural and social background v. The extent to which community-based learning forms part of the curriculum v The degree of community involvement in the training program v. The organizational linkages between the school or program and the health services system

What major initiatives should a medical school take to be recognized as “socially accountable”?

First: The school must : vprovide ample and appropriate learning opportunities for medical students to grasp the complexity of socioeconomic determinants in health vintegrate the biomedical aspects of diseases into a holistic approach to health

Second: The school must : v. Share responsibility for ensuring equitable and quality health services delivery to an entire population within a well defined geographical area v In this context, public health and health service research should be declared priority investments to experiment and develop best health practices for involving future graduates.

Third: the school must : v. Recognize social accountability as a mark of academic excellence, promoting relevant evaluation and accreditation standards and mechanisms v New standards should be adopted highlighting the school’s capacity to anticipate the profile, mix, and number of health professionals needed to meet society’s present and future priority health concerns, and its ability to help create relevant work environments for its graduates v Moreover, the school’s performance should be assessed by a group composed partly by academic staff and partly by representatives of the society the school intends to serve.

A number of innovative medical education programs, building on social accountability principles, have been established to address priority health needs of their communities and health systems

Networking Innovative Socially Accountable Medical Education Programs

ØIn 2007, the Global Health Education Consortium (GHEC) received funding to facilitate the development of a network of socially accountable medical schools whose express mandate is to train physicians for addressing health needs in resource-constrained settings. ØGHEC identified eight medical education programs of varying sizes and operating in high- and low-income countries, whose mission is to train doctors for service in underserved areas

These schools are: o The Latin American School of Medicine in Cuba (ELAM) o The Comprehensive Community Physician Training Program in Venezuela (CCPTP) o The Northern Ontario School of Medicine in Canada (NOSM) o The Faculty of Health Sciences at Walter Sisulu University in South Africa (WSU) o Flinders University School of Medicine (FLINDERS) and James Cook Faculty of Medicine, Health and Molecular Sciences (JCU) in Australia o. Ateneo de Zamboanga University School of Medicine (ADZU) and the University of Philippines School of Health Sciences (SHS) in the Philippines

In late 2008 : THE net was created: To increase understanding globally of how schools can produce health and health workforce outcomes that improve health equity and health system performance and how to measure progress towards these goals It is a global network of socially accountable schools sharing a core commitment to achieving equity in health care and health outcomes through quality education, service and action-oriented research responsive to the needs of communities and health care systems.

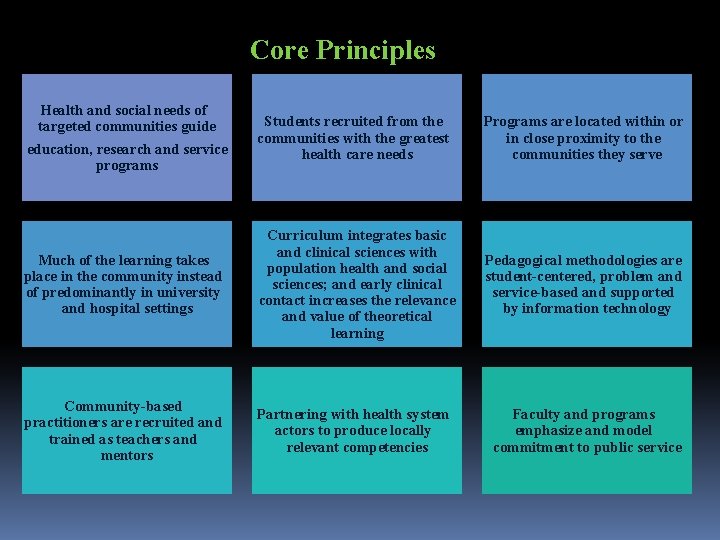

Core Principles Health and social needs of targeted communities guide education, research and service programs Students recruited from the communities with the greatest health care needs Programs are located within or in close proximity to the communities they serve Much of the learning takes place in the community instead of predominantly in university and hospital settings Curriculum integrates basic and clinical sciences with population health and social sciences; and early clinical contact increases the relevance and value of theoretical learning Pedagogical methodologies are student-centered, problem and service-based and supported by information technology Community-based practitioners are recruited and trained as teachers and mentors Partnering with health system actors to produce locally relevant competencies Faculty and programs emphasize and model commitment to public service

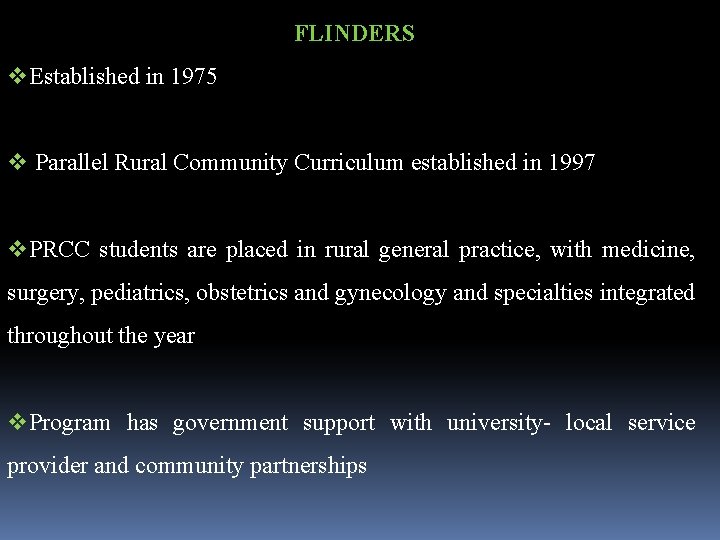

FLINDERS v. Established in 1975 v Parallel Rural Community Curriculum established in 1997 v. PRCC students are placed in rural general practice, with medicine, surgery, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology and specialties integrated throughout the year v. Program has government support with university- local service provider and community partnerships

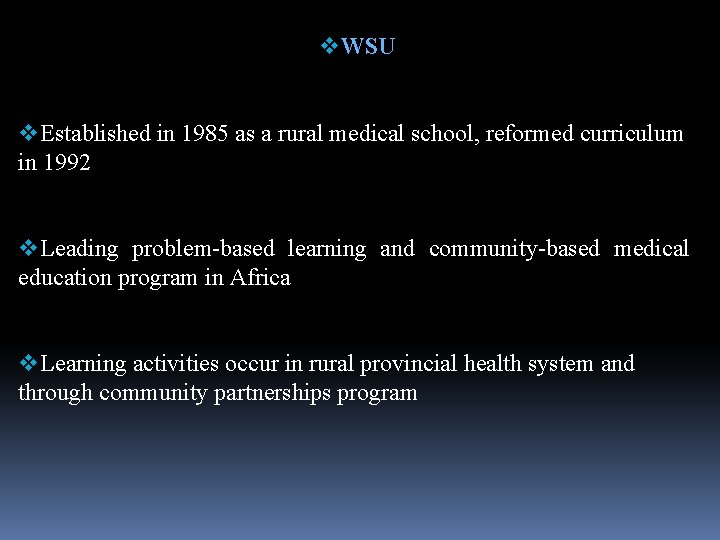

v. WSU v. Established in 1985 as a rural medical school, reformed curriculum in 1992 v. Leading problem-based learning and community-based medical education program in Africa v. Learning activities occur in rural provincial health system and through community partnerships program

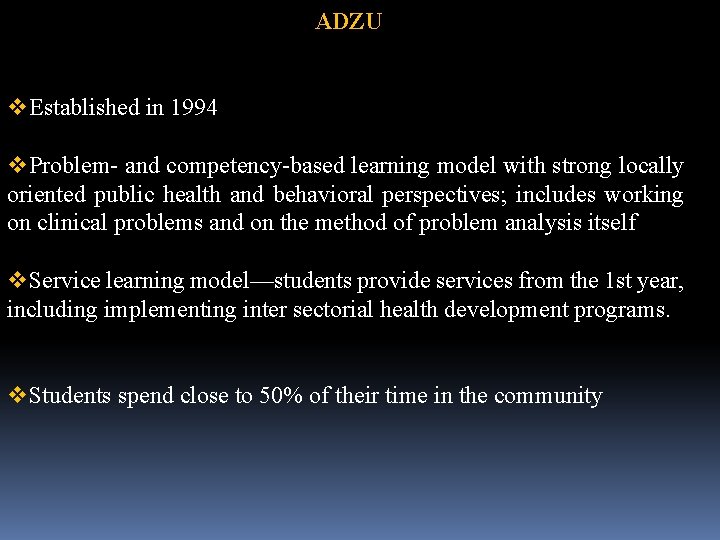

ADZU v. Established in 1994 v. Problem- and competency-based learning model with strong locally oriented public health and behavioral perspectives; includes working on clinical problems and on the method of problem analysis itself v. Service learning model—students provide services from the 1 st year, including implementing inter sectorial health development programs. v. Students spend close to 50% of their time in the community

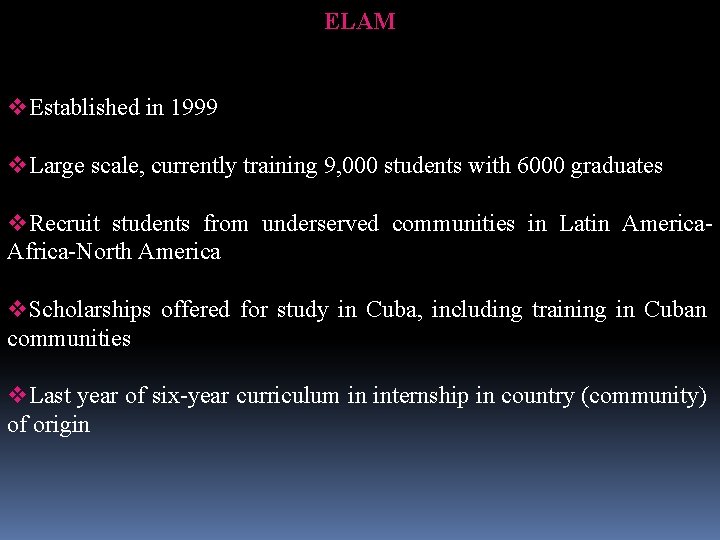

ELAM v. Established in 1999 v. Large scale, currently training 9, 000 students with 6000 graduates v. Recruit students from underserved communities in Latin America. Africa-North America v. Scholarships offered for study in Cuba, including training in Cuban communities v. Last year of six-year curriculum in internship in country (community) of origin

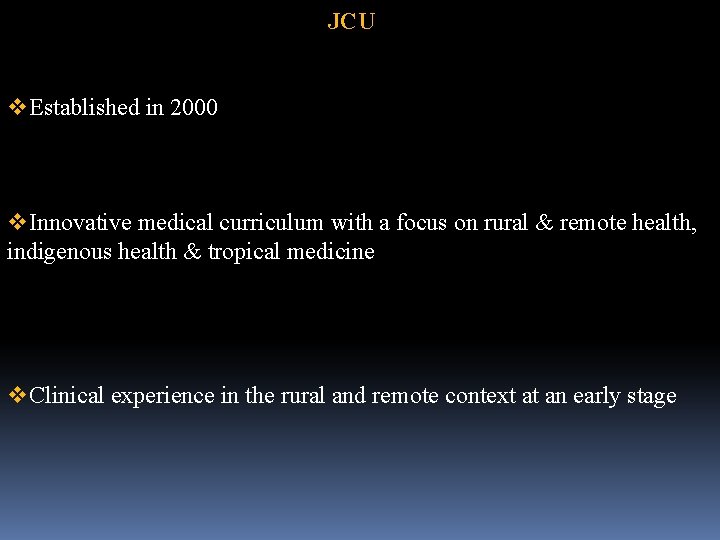

JCU v. Established in 2000 v. Innovative medical curriculum with a focus on rural & remote health, indigenous health & tropical medicine v. Clinical experience in the rural and remote context at an early stage

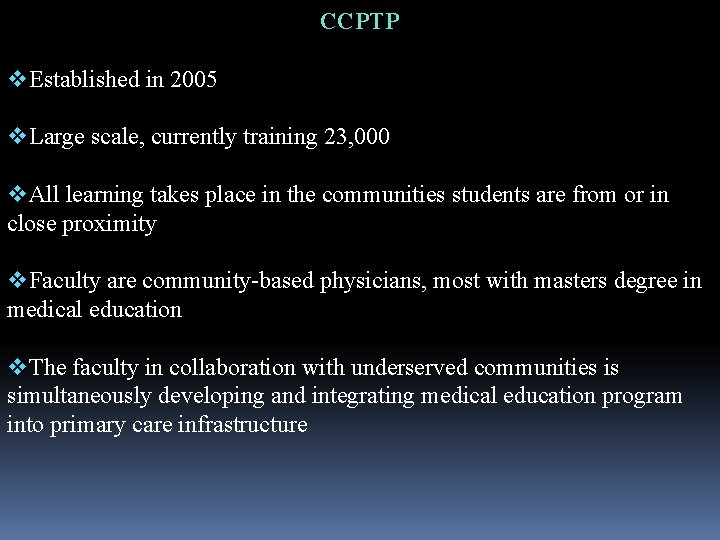

CCPTP v. Established in 2005 v. Large scale, currently training 23, 000 v. All learning takes place in the communities students are from or in close proximity v. Faculty are community-based physicians, most with masters degree in medical education v. The faculty in collaboration with underserved communities is simultaneously developing and integrating medical education program into primary care infrastructure

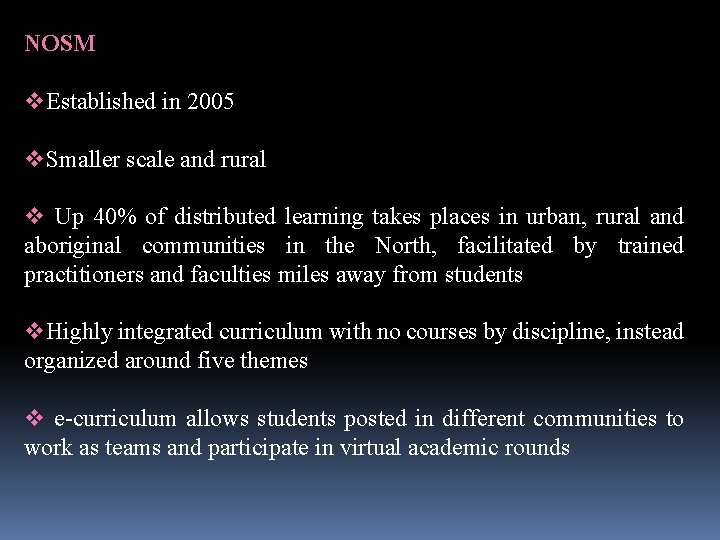

NOSM v. Established in 2005 v. Smaller scale and rural v Up 40% of distributed learning takes places in urban, rural and aboriginal communities in the North, facilitated by trained practitioners and faculties miles away from students v. Highly integrated curriculum with no courses by discipline, instead organized around five themes v e-curriculum allows students posted in different communities to work as teams and participate in virtual academic rounds

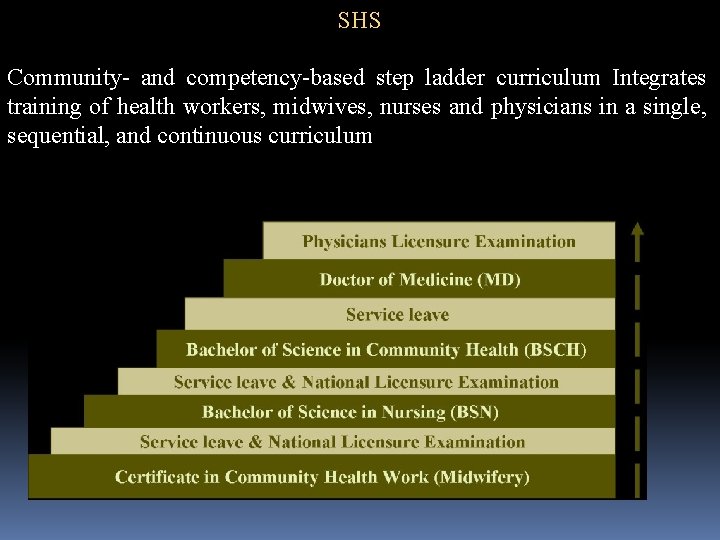

SHS Community- and competency-based step ladder curriculum Integrates training of health workers, midwives, nurses and physicians in a single, sequential, and continuous curriculum

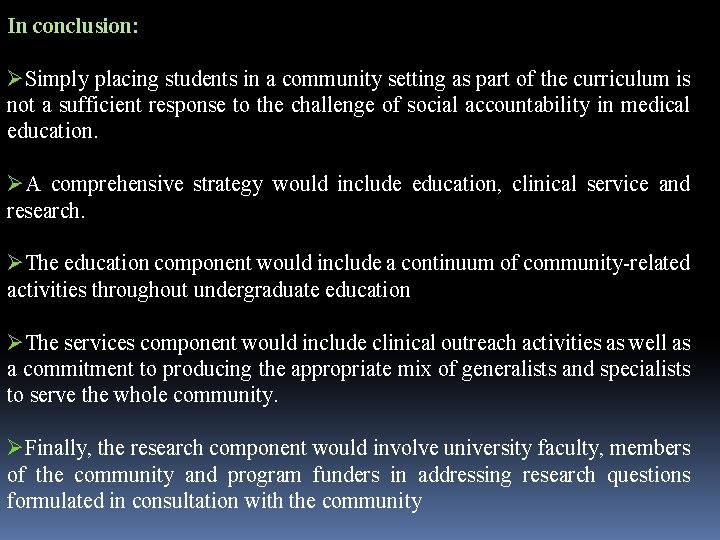

In conclusion: ØSimply placing students in a community setting as part of the curriculum is not a sufficient response to the challenge of social accountability in medical education. ØA comprehensive strategy would include education, clinical service and research. ØThe education component would include a continuum of community-related activities throughout undergraduate education ØThe services component would include clinical outreach activities as well as a commitment to producing the appropriate mix of generalists and specialists to serve the whole community. ØFinally, the research component would involve university faculty, members of the community and program funders in addressing research questions formulated in consultation with the community

community-based education: (WHO , 1987) • learning activities that take place within the community in which not only students but also teachers and patients are actively engaged throughout the educational experience • Community-based education can be implemented wherever people live, in rural, suburban or urban areas

rationale behind community-oriented medical education (Habbick & Leeder) : • creating more appropriate knowledge, skills and attitudes • Deeper understanding of range of health, illness, and the workings of health and social services • Deeper understanding of the contribution of social and environmental factors to the causation and prevention of illness • A more patient-oriented perspective • making better use of the expertise and availability of staff and patients who are in primary care settings • enhancing multidisciplinary working • Broader range of learning opportunities • Increasing recruitment into primary care and generalist specialties.

Collectively, THE net enables sharing, peer support and collaboration while working with stakeholders to develop and disseminate evidence, challenge assumptions, set standards and promote socially accountable medical education

- Slides: 36