SO 441 Synoptic Meteorology Extratropical cyclones Cloud pattern

- Slides: 23

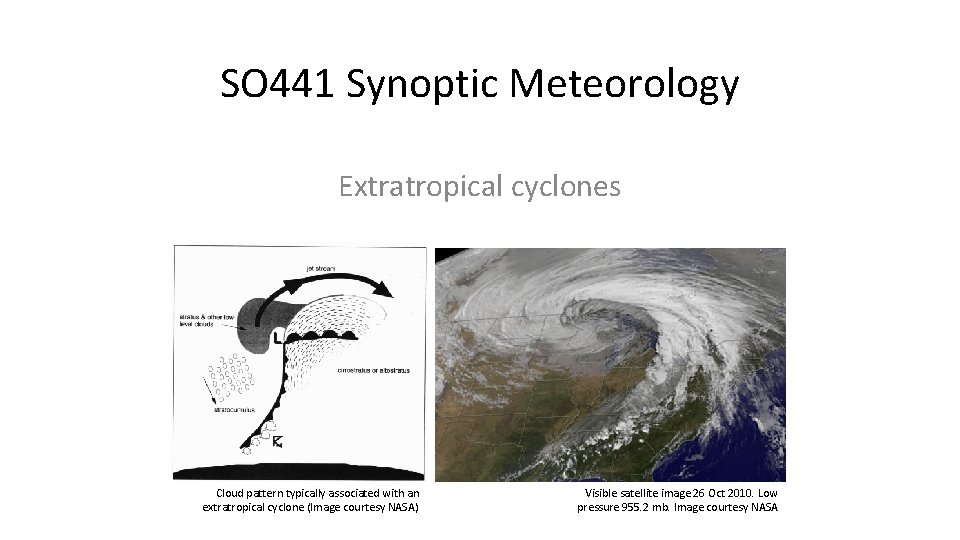

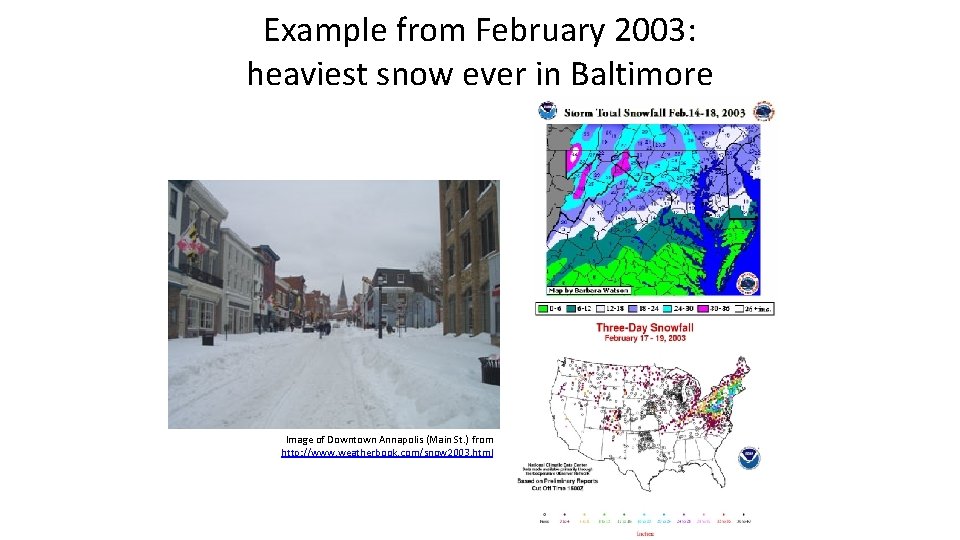

SO 441 Synoptic Meteorology Extratropical cyclones Cloud pattern typically associated with an extratropical cyclone (Image courtesy NASA) Visible satellite image 26 Oct 2010. Low pressure 955. 2 mb. Image courtesy NASA

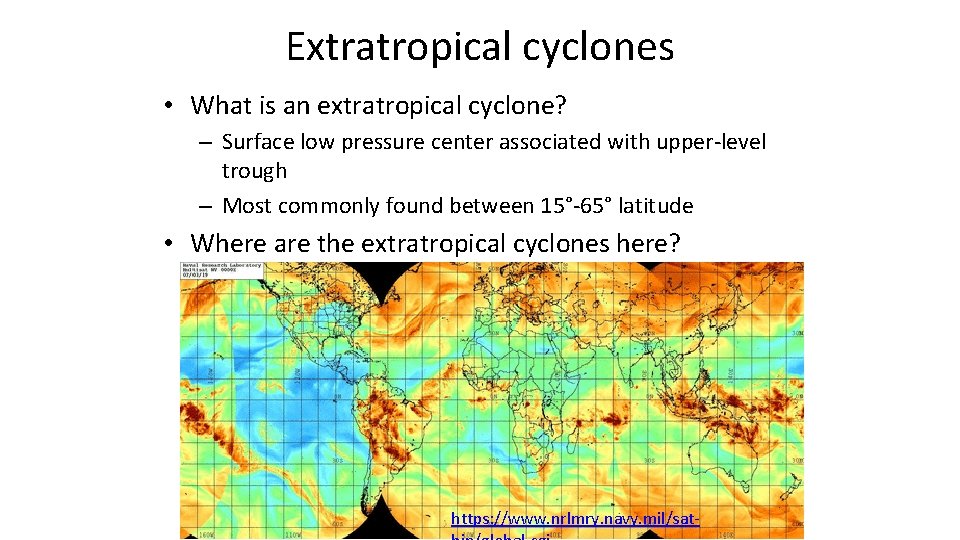

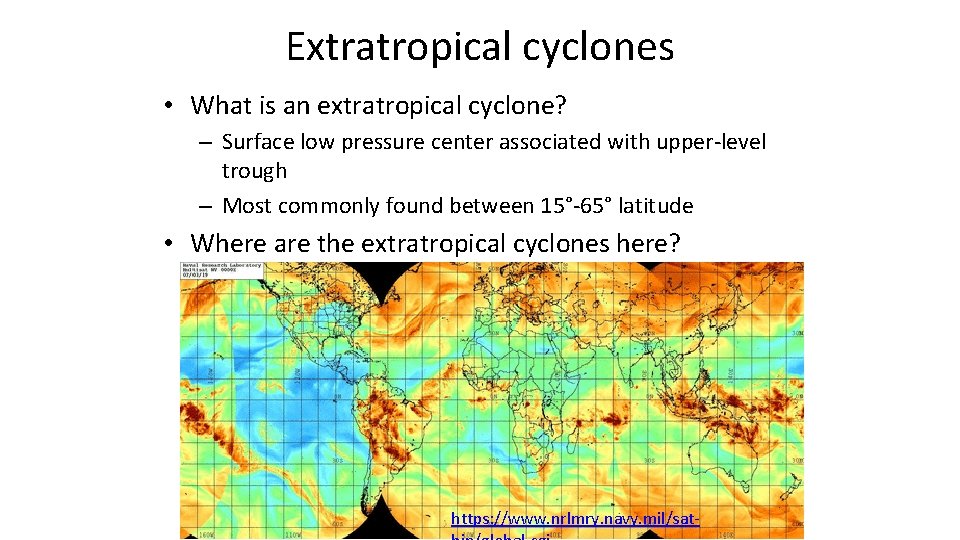

Extratropical cyclones • What is an extratropical cyclone? – Surface low pressure center associated with upper-level trough – Most commonly found between 15°-65° latitude • Where are the extratropical cyclones here? https: //www. nrlmry. navy. mil/sat-

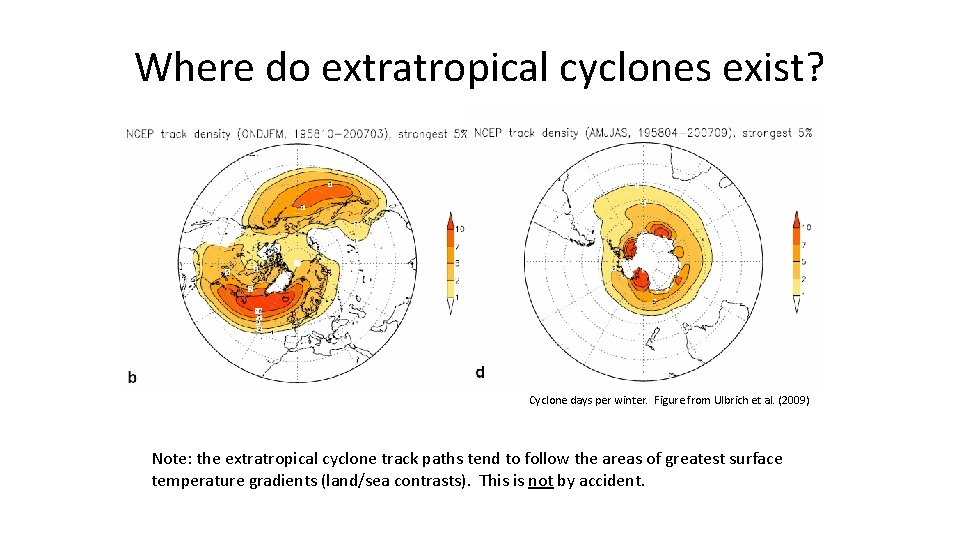

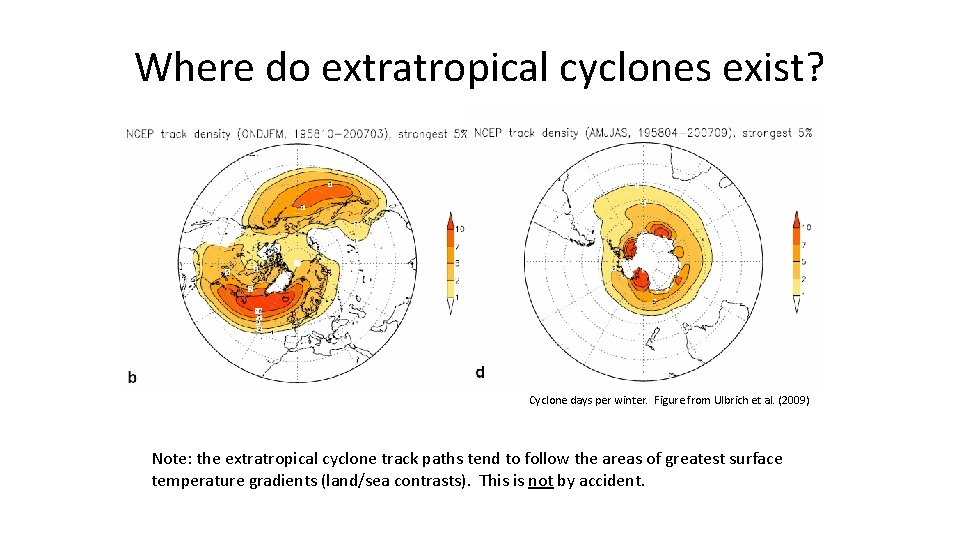

Where do extratropical cyclones exist? Cyclone days per winter. Figure from Ulbrich et al. (2009) Note: the extratropical cyclone track paths tend to follow the areas of greatest surface temperature gradients (land/sea contrasts). This is not by accident.

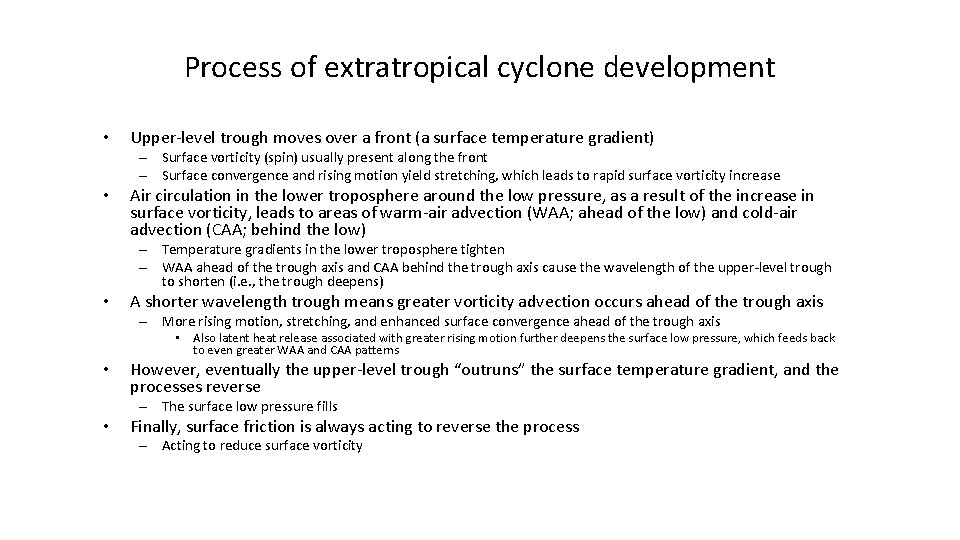

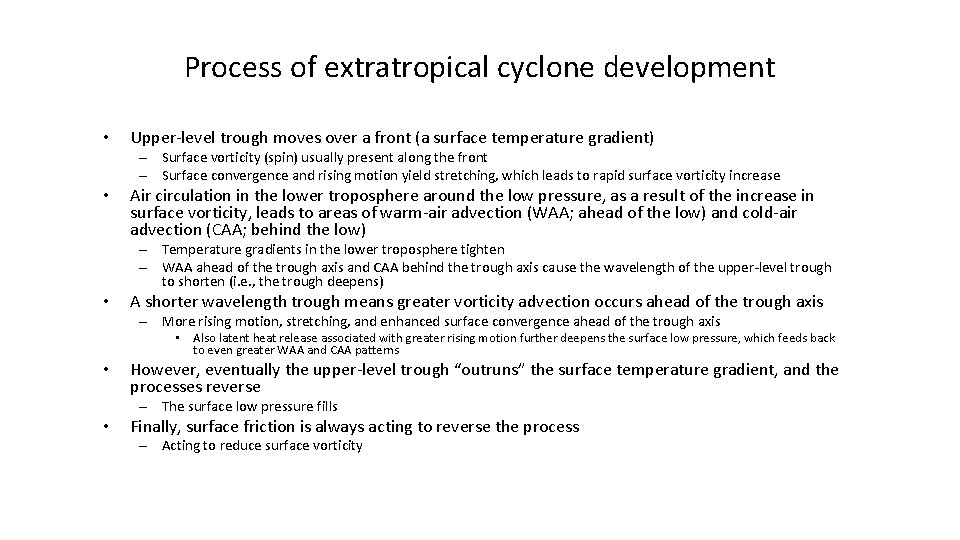

Process of extratropical cyclone development • Upper-level trough moves over a front (a surface temperature gradient) – Surface vorticity (spin) usually present along the front – Surface convergence and rising motion yield stretching, which leads to rapid surface vorticity increase • Air circulation in the lower troposphere around the low pressure, as a result of the increase in surface vorticity, leads to areas of warm-air advection (WAA; ahead of the low) and cold-air advection (CAA; behind the low) – Temperature gradients in the lower troposphere tighten – WAA ahead of the trough axis and CAA behind the trough axis cause the wavelength of the upper-level trough to shorten (i. e. , the trough deepens) • A shorter wavelength trough means greater vorticity advection occurs ahead of the trough axis – More rising motion, stretching, and enhanced surface convergence ahead of the trough axis • Also latent heat release associated with greater rising motion further deepens the surface low pressure, which feeds back to even greater WAA and CAA patterns • However, eventually the upper-level trough “outruns” the surface temperature gradient, and the processes reverse – The surface low pressure fills • Finally, surface friction is always acting to reverse the process – Acting to reduce surface vorticity

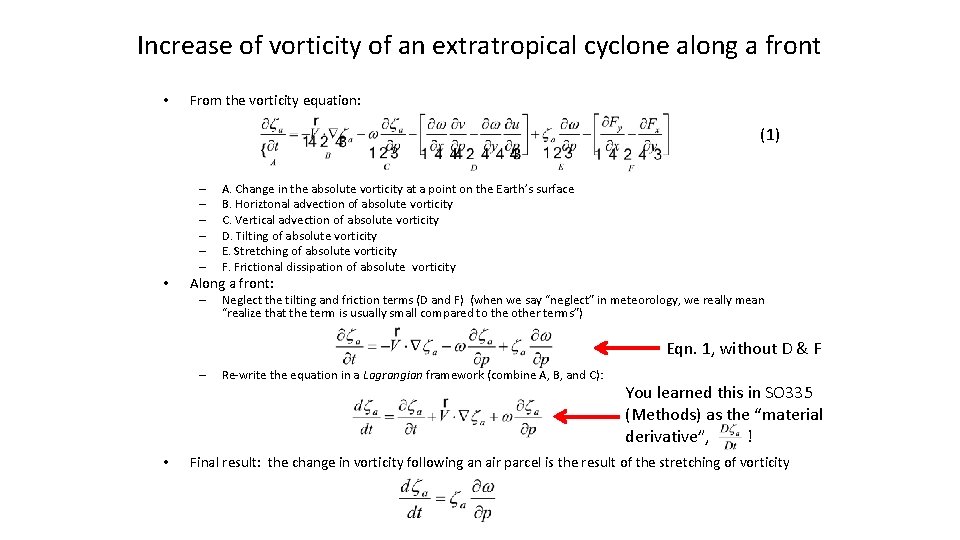

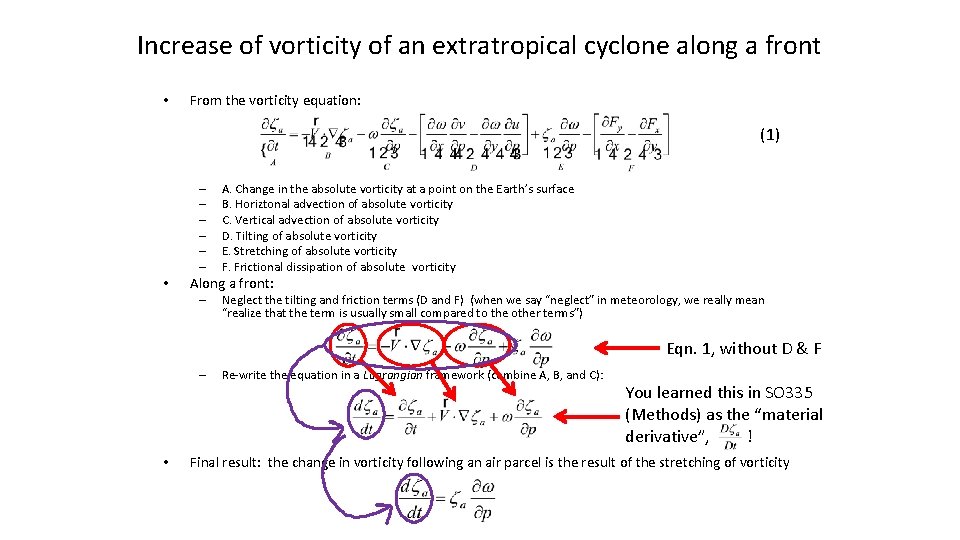

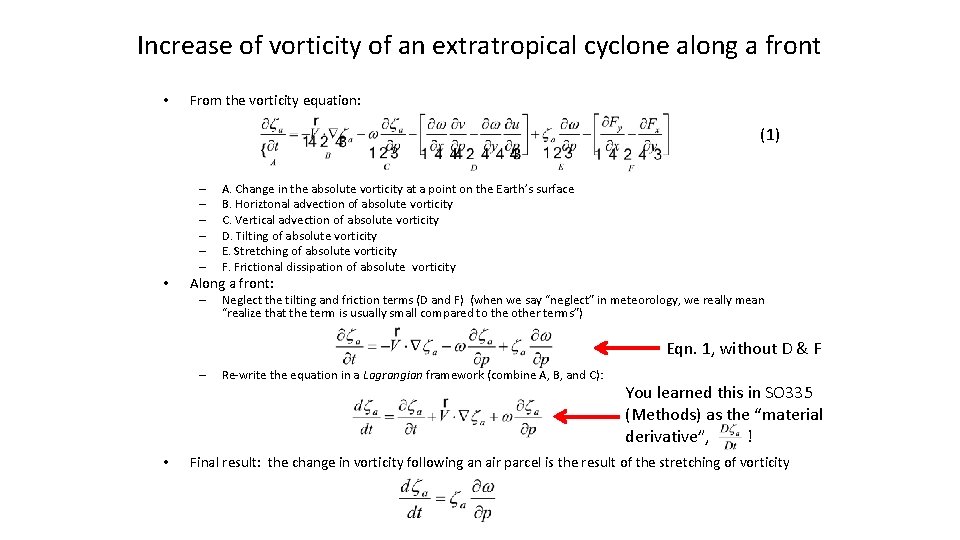

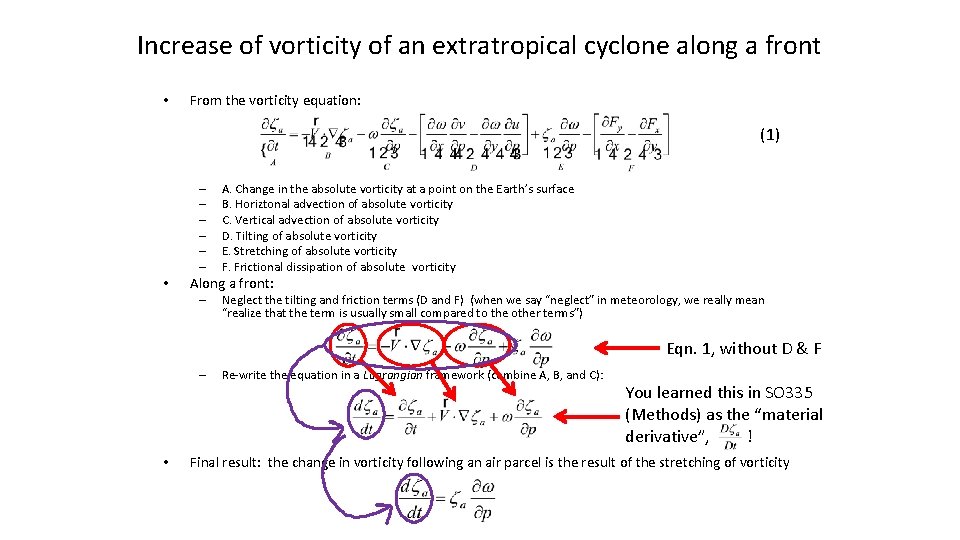

Increase of vorticity of an extratropical cyclone along a front • From the vorticity equation: (1) – – – • A. Change in the absolute vorticity at a point on the Earth’s surface B. Horiztonal advection of absolute vorticity C. Vertical advection of absolute vorticity D. Tilting of absolute vorticity E. Stretching of absolute vorticity F. Frictional dissipation of absolute vorticity Along a front: – Neglect the tilting and friction terms (D and F) (when we say “neglect” in meteorology, we really mean “realize that the term is usually small compared to the other terms”) Eqn. 1, without D & F – • Re-write the equation in a Lagrangian framework (combine A, B, and C): You learned this in SO 335 (Methods) as the “material derivative”, ! Final result: the change in vorticity following an air parcel is the result of the stretching of vorticity

Increase of vorticity of an extratropical cyclone along a front • From the vorticity equation: (1) – – – • A. Change in the absolute vorticity at a point on the Earth’s surface B. Horiztonal advection of absolute vorticity C. Vertical advection of absolute vorticity D. Tilting of absolute vorticity E. Stretching of absolute vorticity F. Frictional dissipation of absolute vorticity Along a front: – Neglect the tilting and friction terms (D and F) (when we say “neglect” in meteorology, we really mean “realize that the term is usually small compared to the other terms”) Eqn. 1, without D & F – • Re-write the equation in a Lagrangian framework (combine A, B, and C): You learned this in SO 335 (Methods) as the “material derivative”, ! Final result: the change in vorticity following an air parcel is the result of the stretching of vorticity

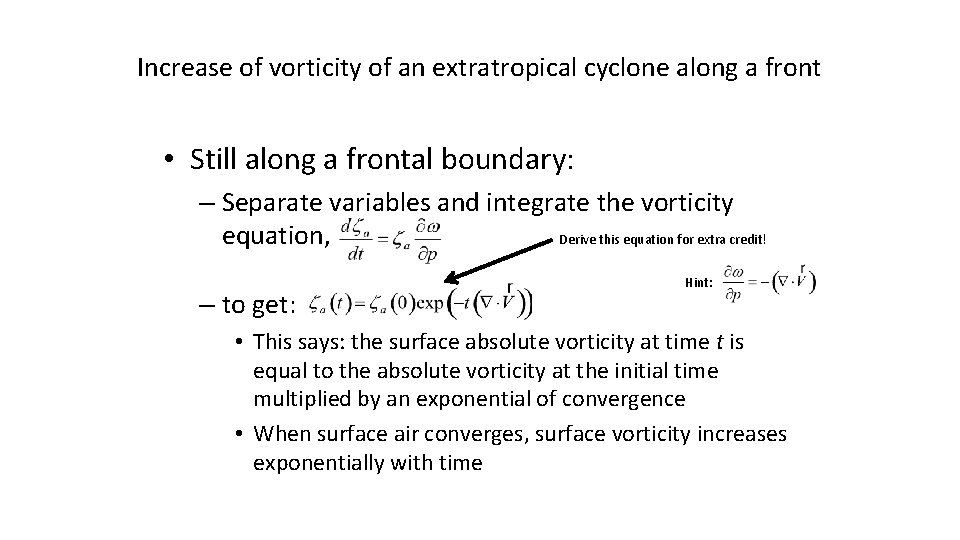

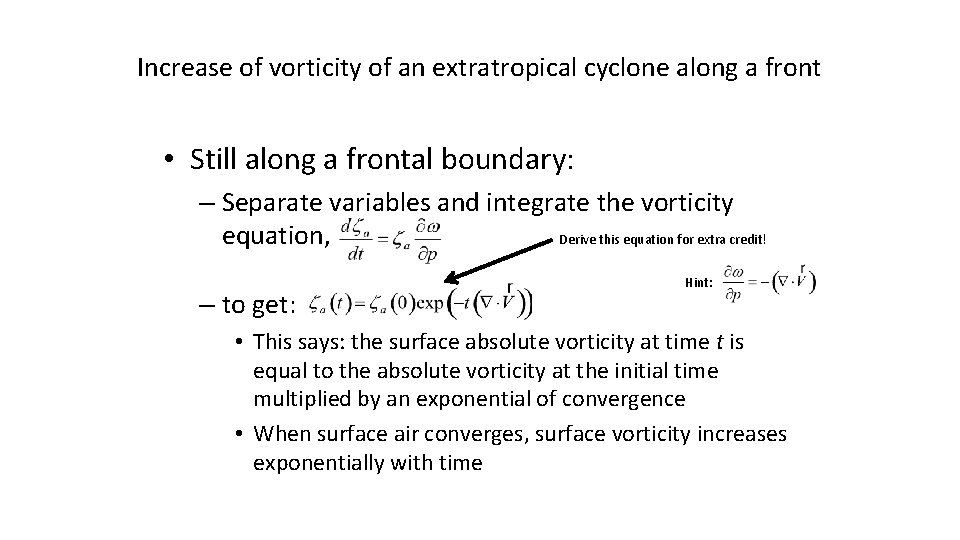

Increase of vorticity of an extratropical cyclone along a front • Still along a frontal boundary: – Separate variables and integrate the vorticity equation, Derive this equation for extra credit! – to get: Hint: • This says: the surface absolute vorticity at time t is equal to the absolute vorticity at the initial time multiplied by an exponential of convergence • When surface air converges, surface vorticity increases exponentially with time

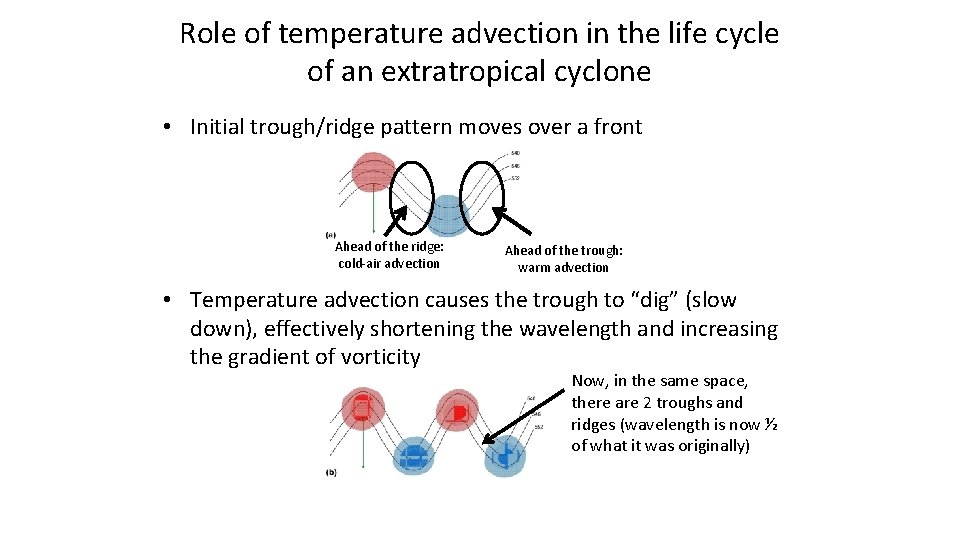

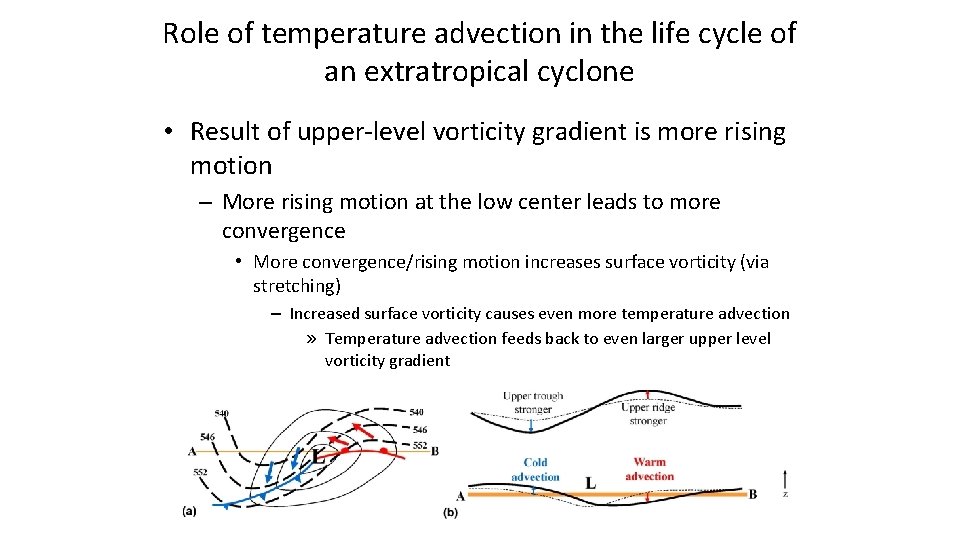

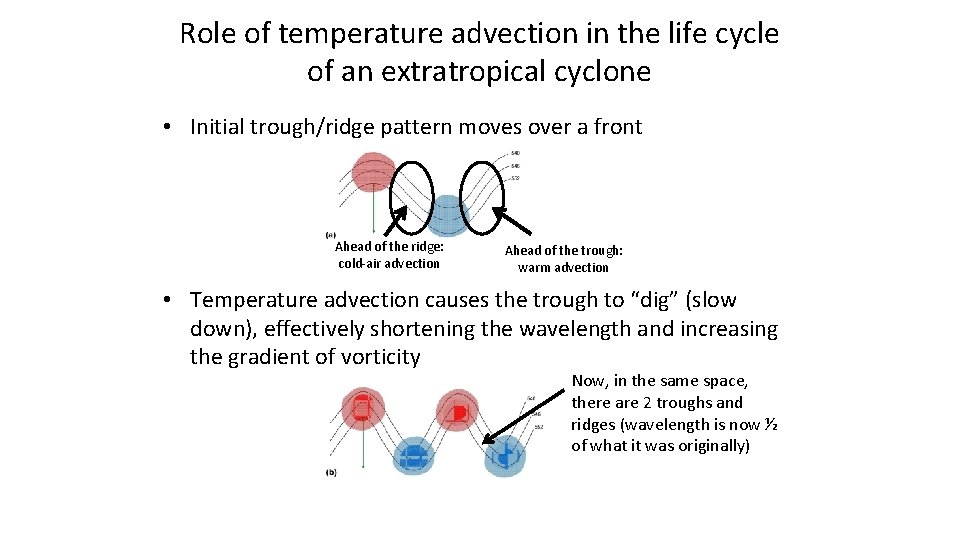

Role of temperature advection in the life cycle of an extratropical cyclone • Initial trough/ridge pattern moves over a front Ahead of the ridge: cold-air advection Ahead of the trough: warm advection • Temperature advection causes the trough to “dig” (slow down), effectively shortening the wavelength and increasing the gradient of vorticity Now, in the same space, there are 2 troughs and ridges (wavelength is now ½ of what it was originally)

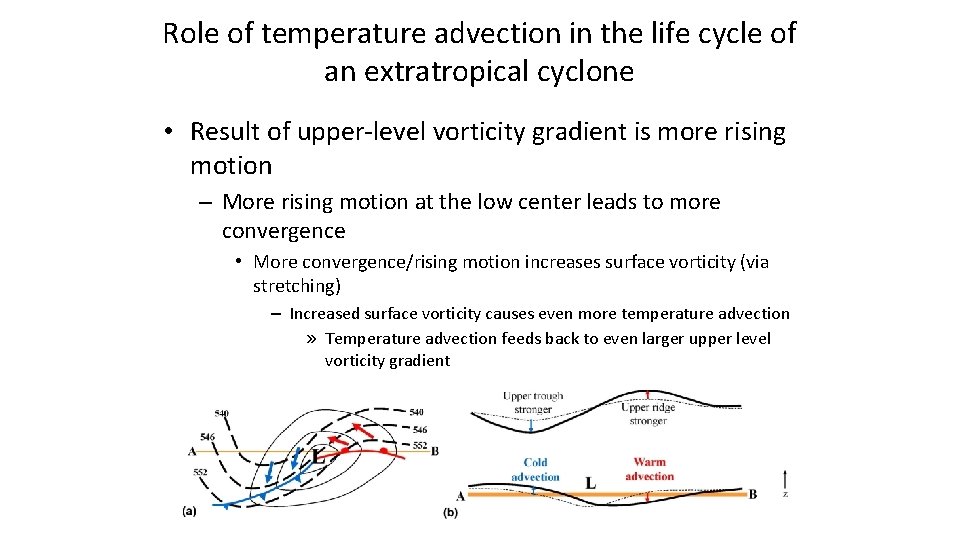

Role of temperature advection in the life cycle of an extratropical cyclone • Result of upper-level vorticity gradient is more rising motion – More rising motion at the low center leads to more convergence • More convergence/rising motion increases surface vorticity (via stretching) – Increased surface vorticity causes even more temperature advection » Temperature advection feeds back to even larger upper level vorticity gradient

Example from 16 -17 Feb 2003 0000 Z 16 Feb 2003

Example from 16 -17 Feb 2003 • Weak frontal boundaries over Southeast U. S. • Upper-level trough moves overhead 0000 Z 16 Feb 2003

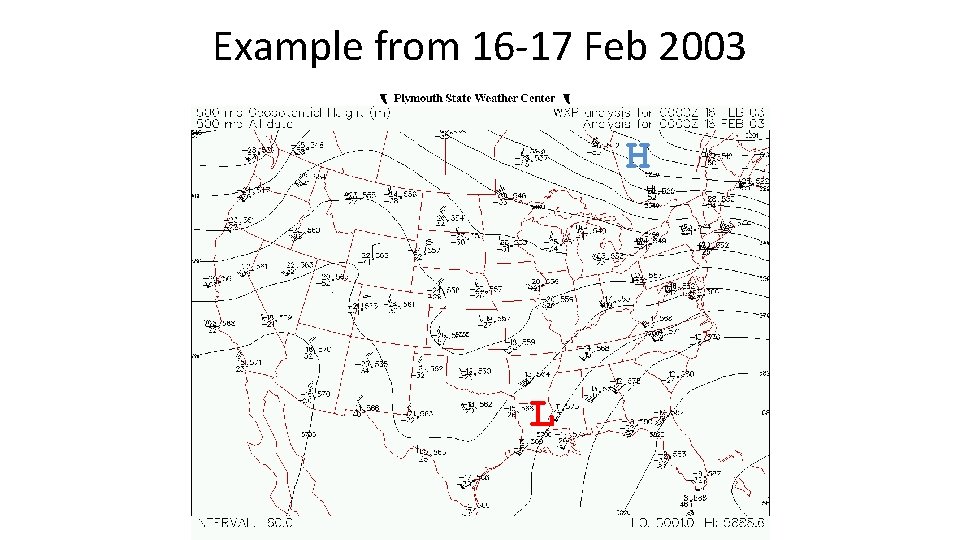

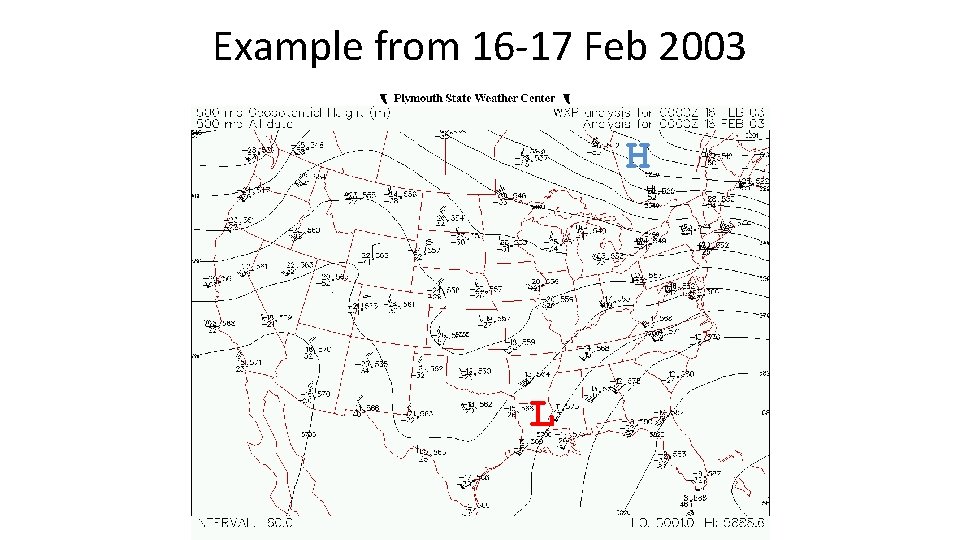

Example from 16 -17 Feb 2003 H L

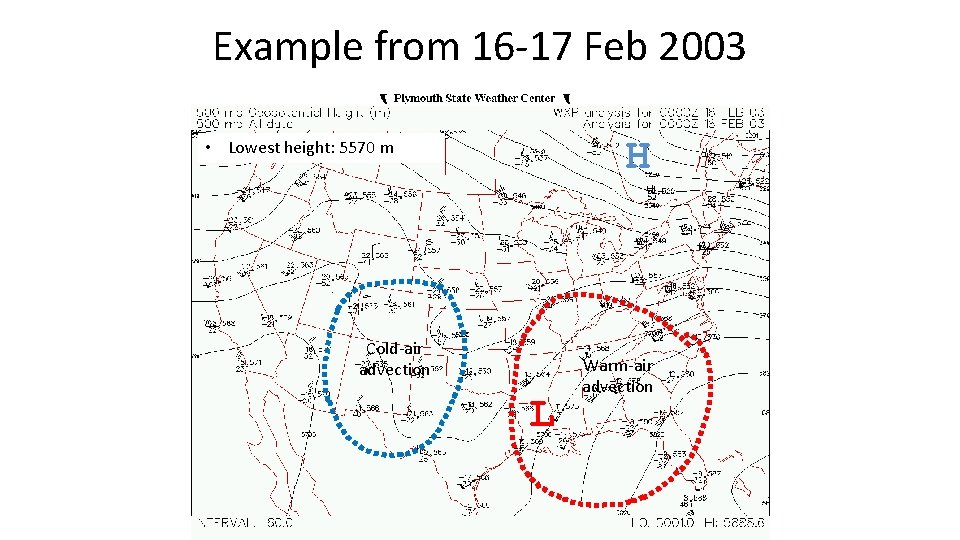

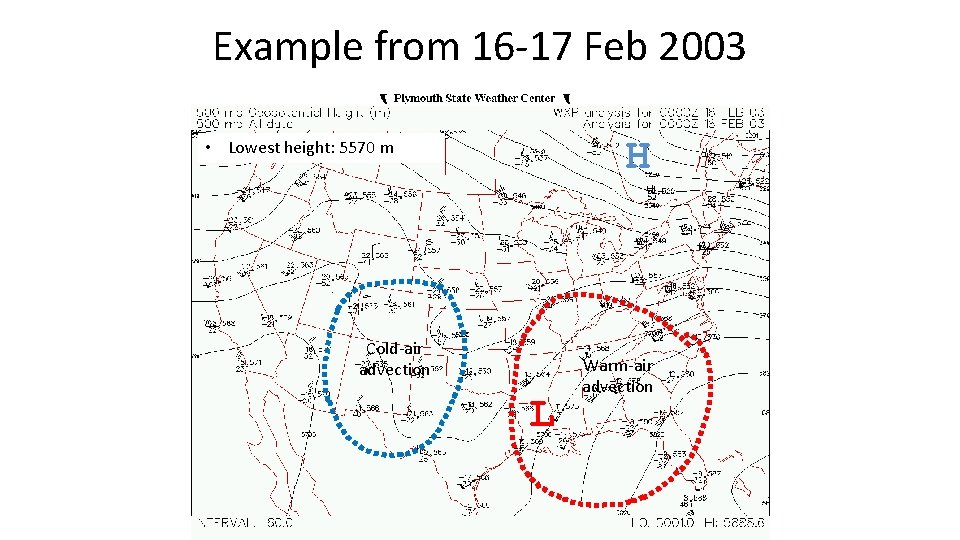

Example from 16 -17 Feb 2003 H • Lowest height: 5570 m Cold-air advection L Warm-air advection

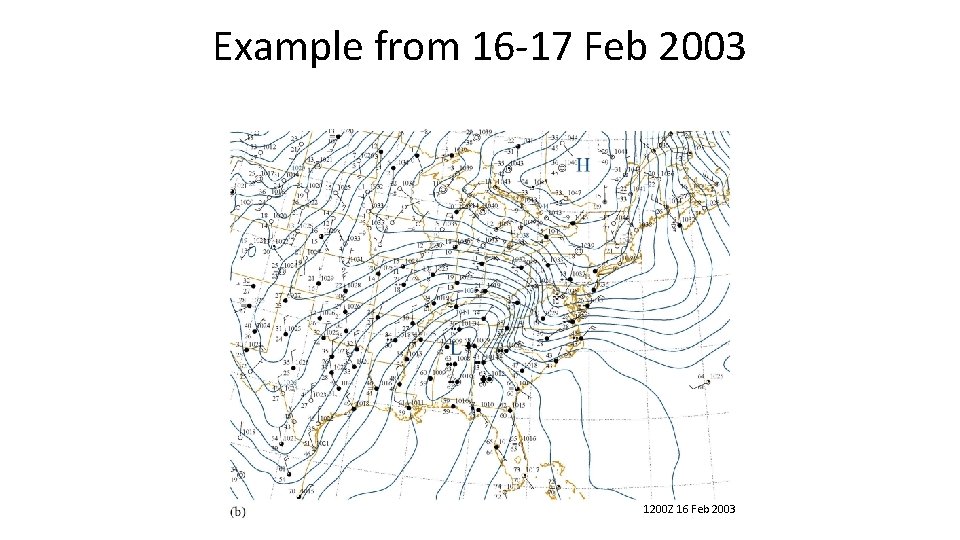

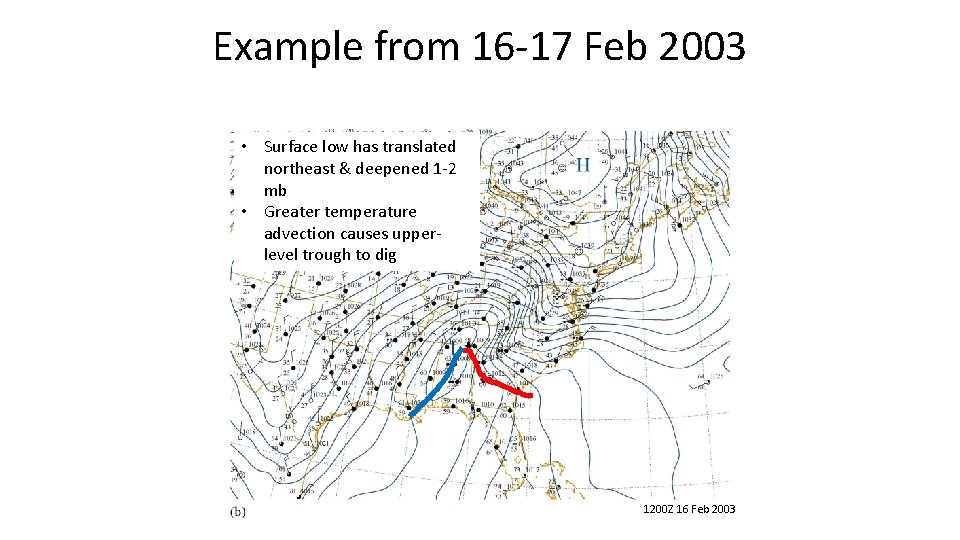

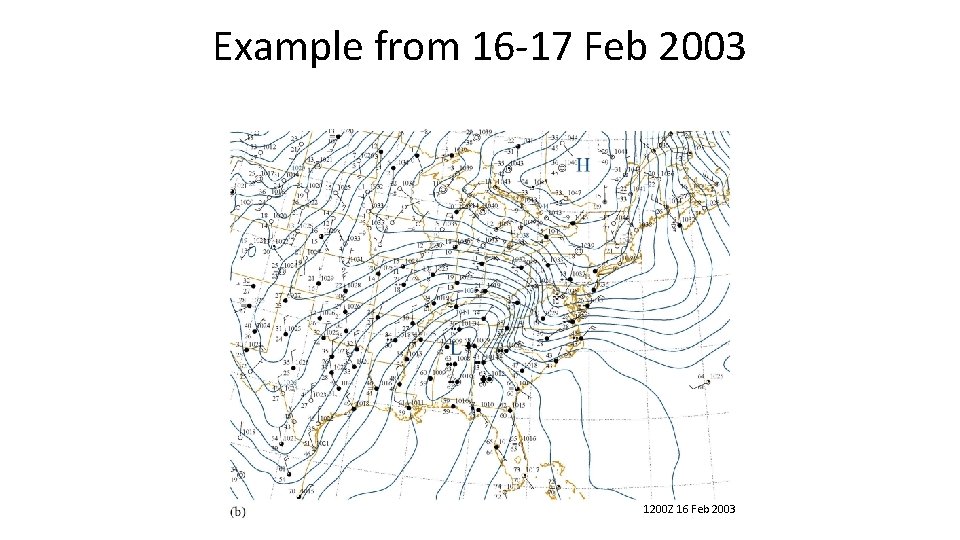

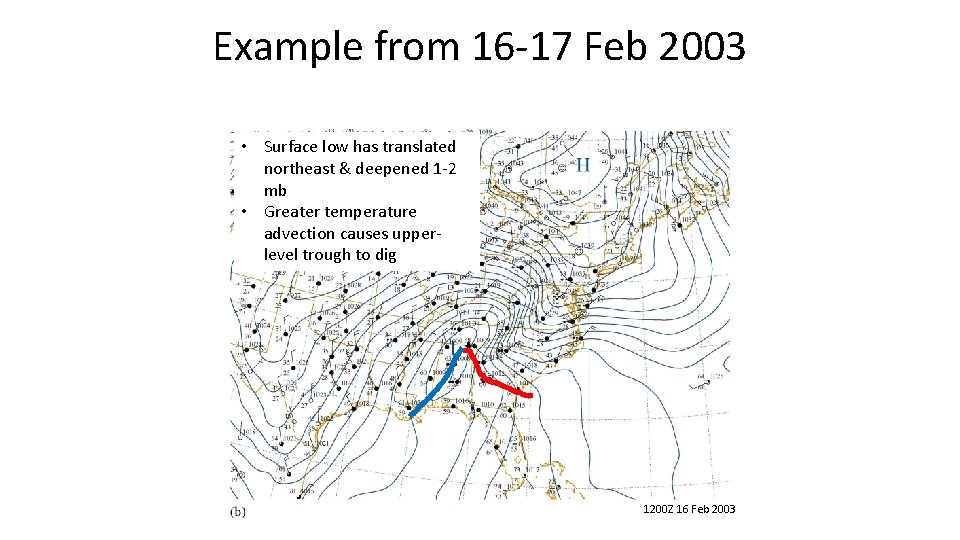

Example from 16 -17 Feb 2003 1200 Z 16 Feb 2003

Example from 16 -17 Feb 2003 • Surface low has translated northeast & deepened 1 -2 mb • Greater temperature advection causes upperlevel trough to dig 1200 Z 16 Feb 2003

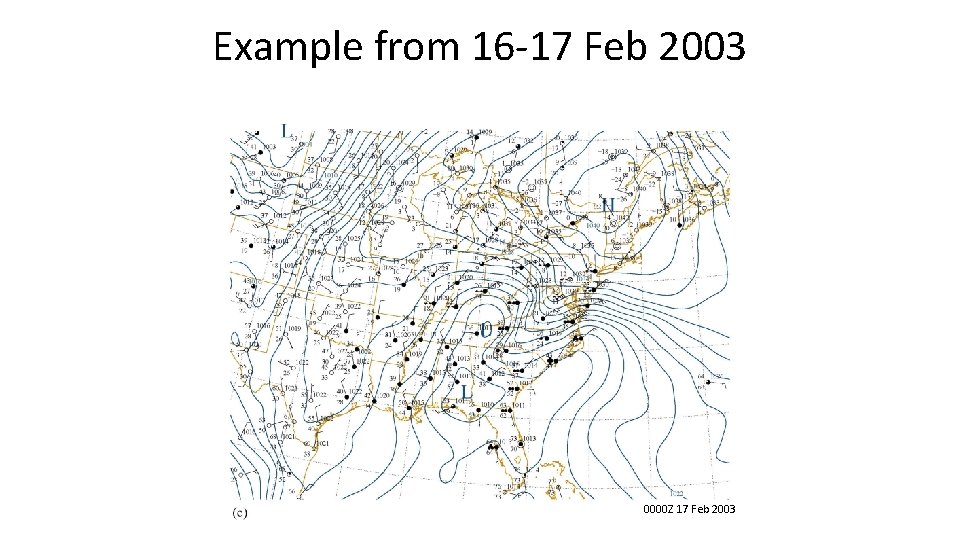

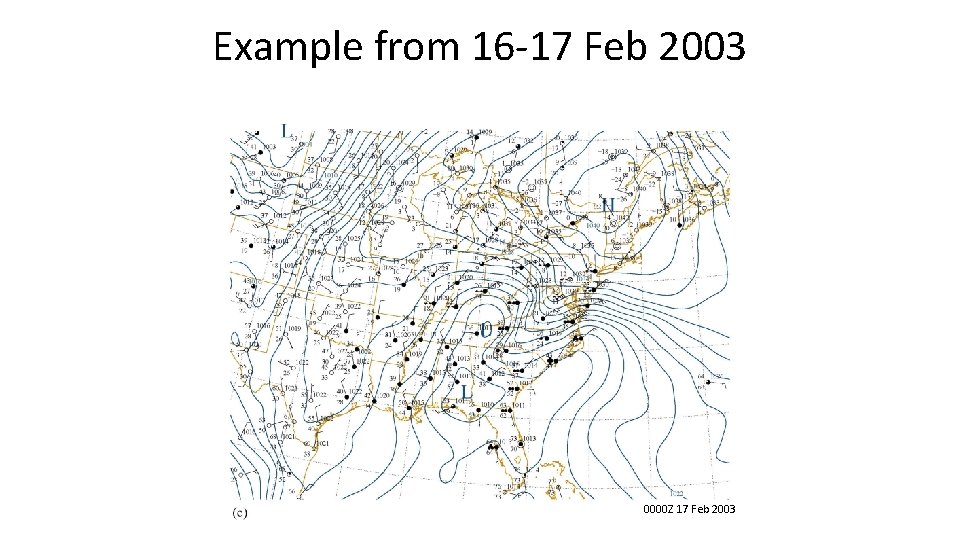

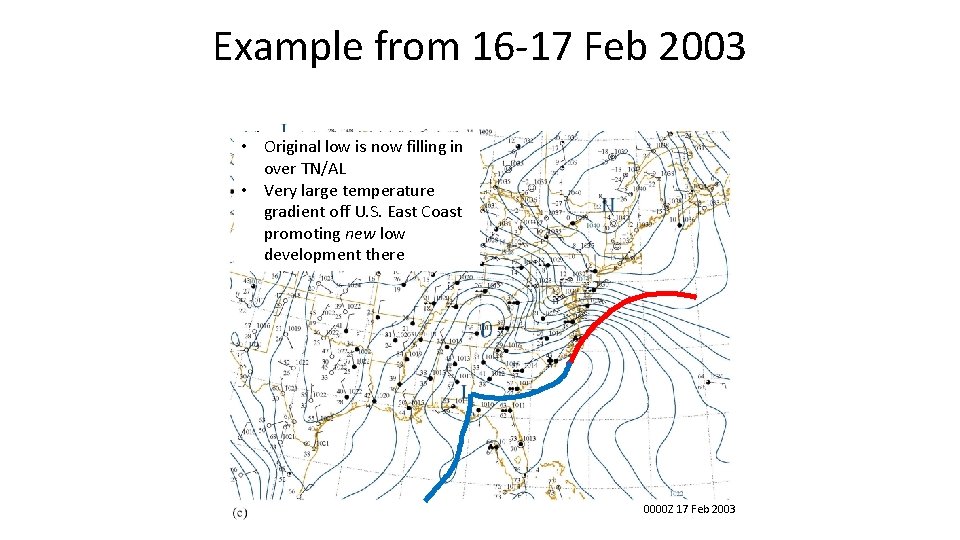

Example from 16 -17 Feb 2003 0000 Z 17 Feb 2003

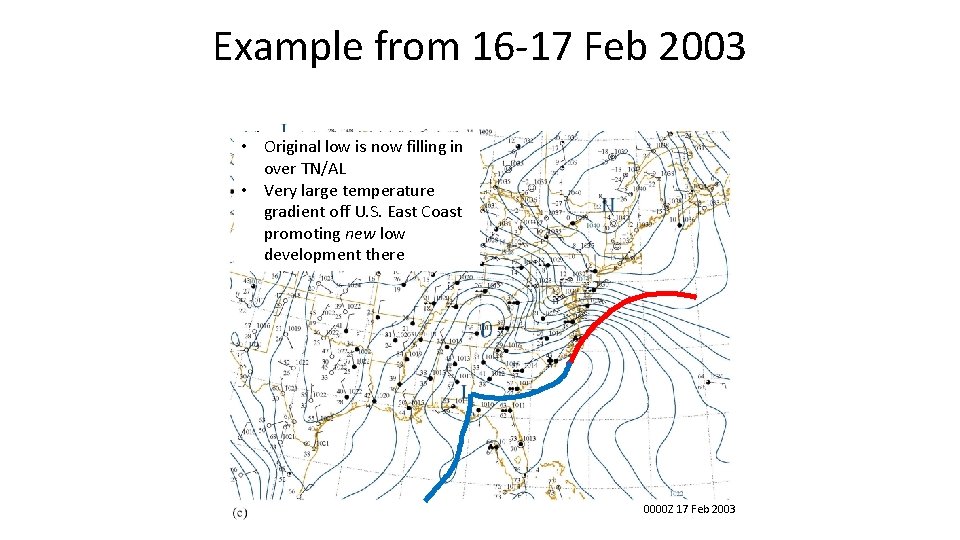

Example from 16 -17 Feb 2003 • Original low is now filling in over TN/AL • Very large temperature gradient off U. S. East Coast promoting new low development there 0000 Z 17 Feb 2003

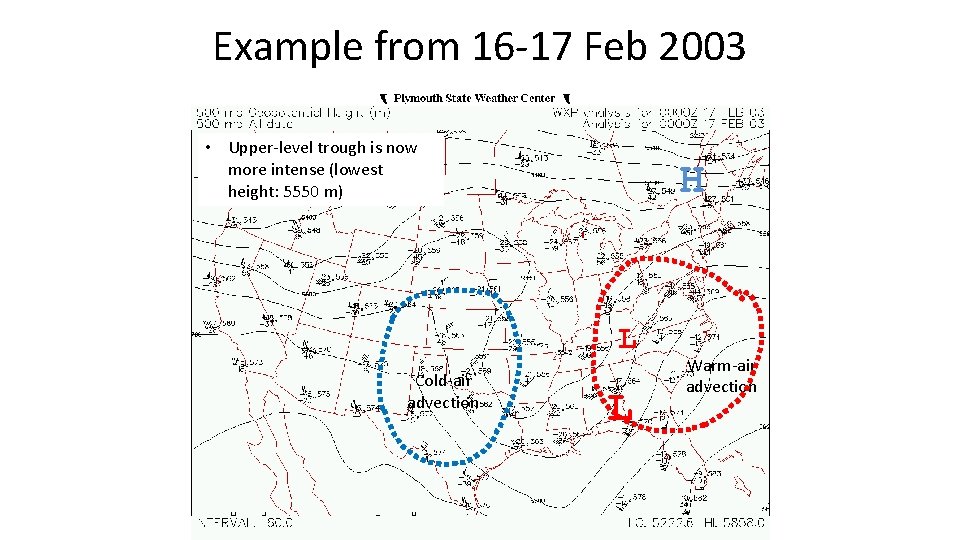

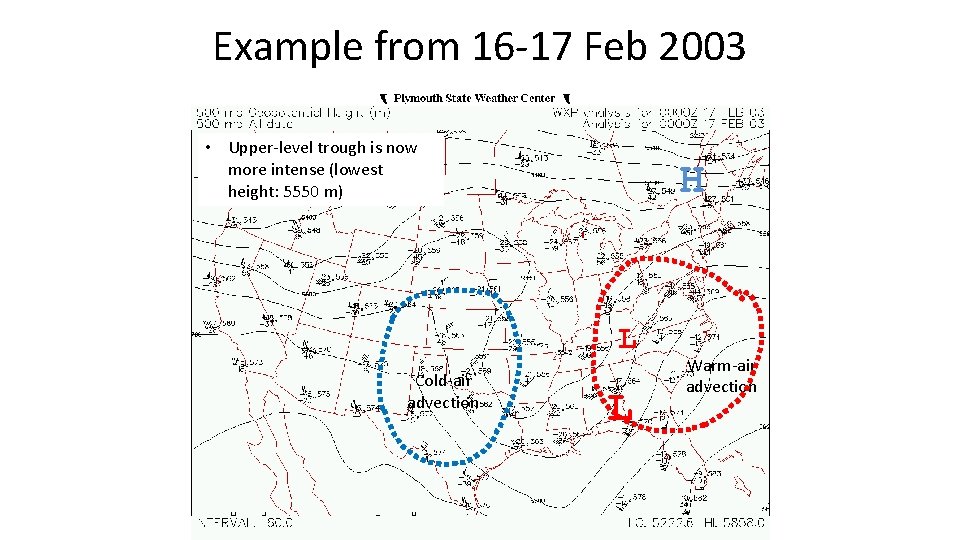

Example from 16 -17 Feb 2003 • Upper-level trough is now more intense (lowest height: 5550 m) H L Cold-air advection L Warm-air advection

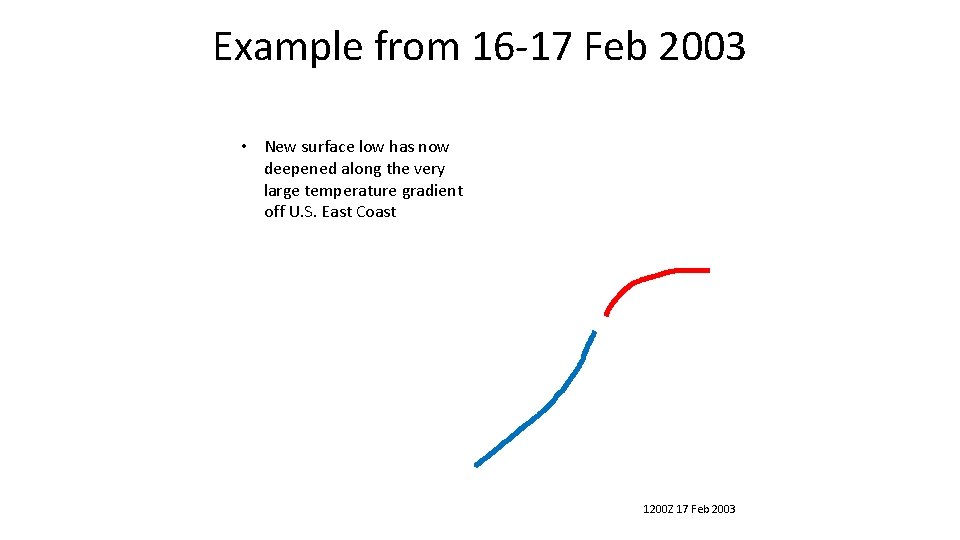

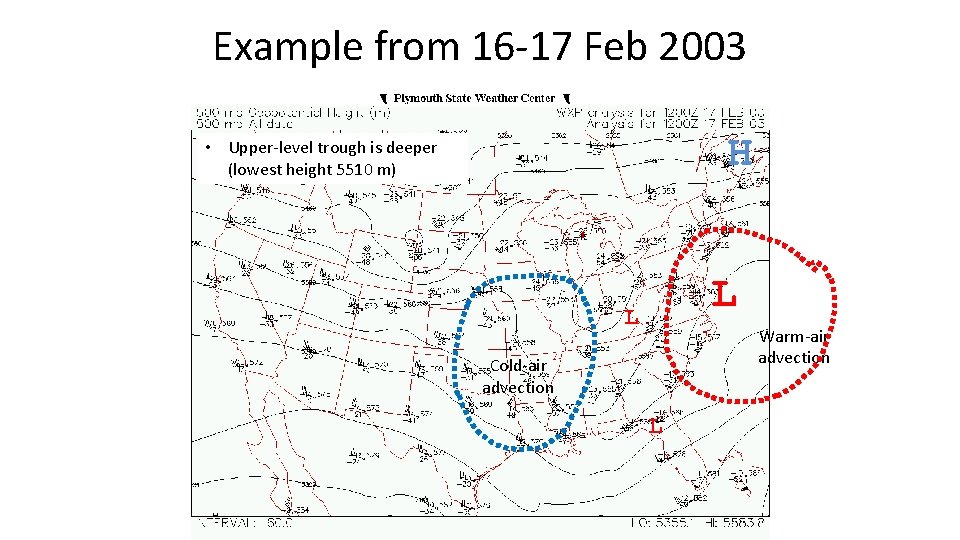

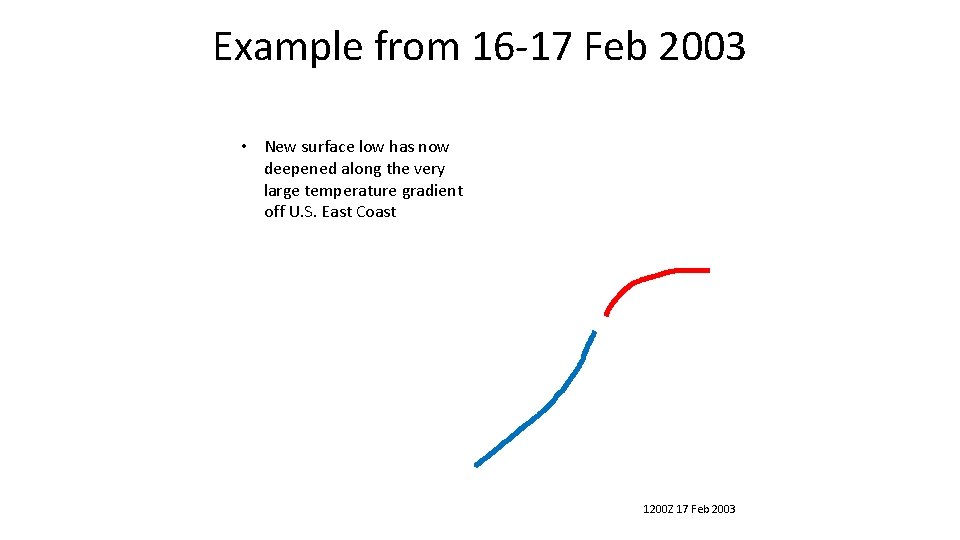

Example from 16 -17 Feb 2003 • New surface low has now deepened along the very large temperature gradient off U. S. East Coast 1200 Z 17 Feb 2003

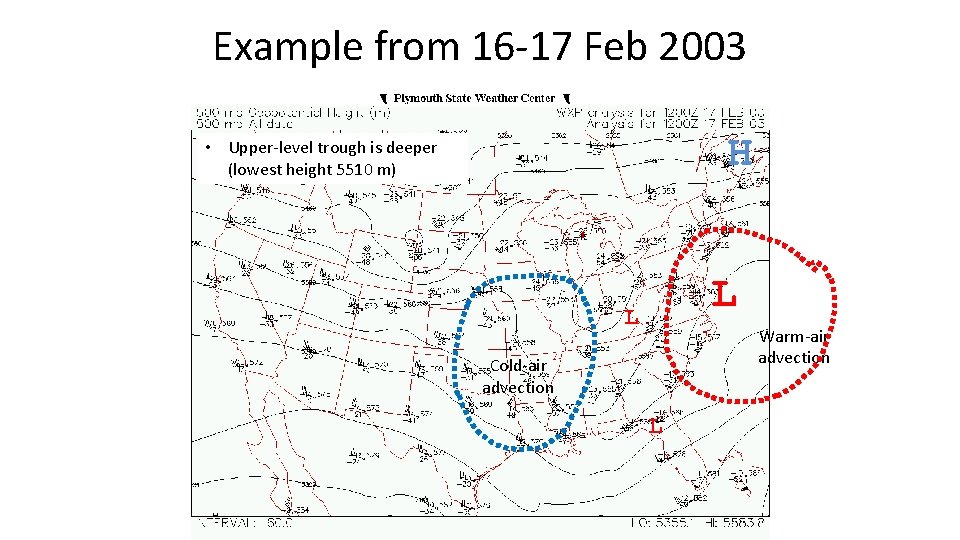

Example from 16 -17 Feb 2003 H • Upper-level trough is deeper (lowest height 5510 m) L L Warm-air advection Cold-air advection L

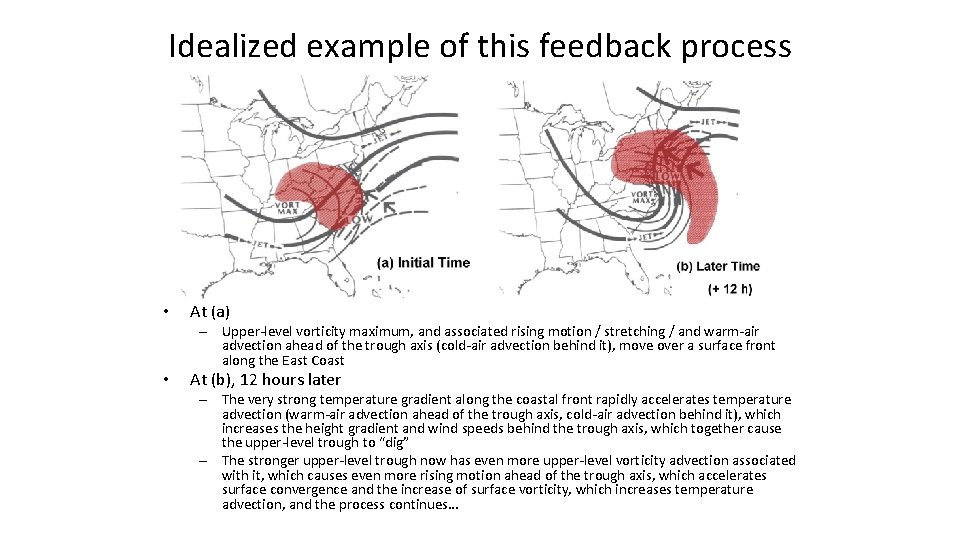

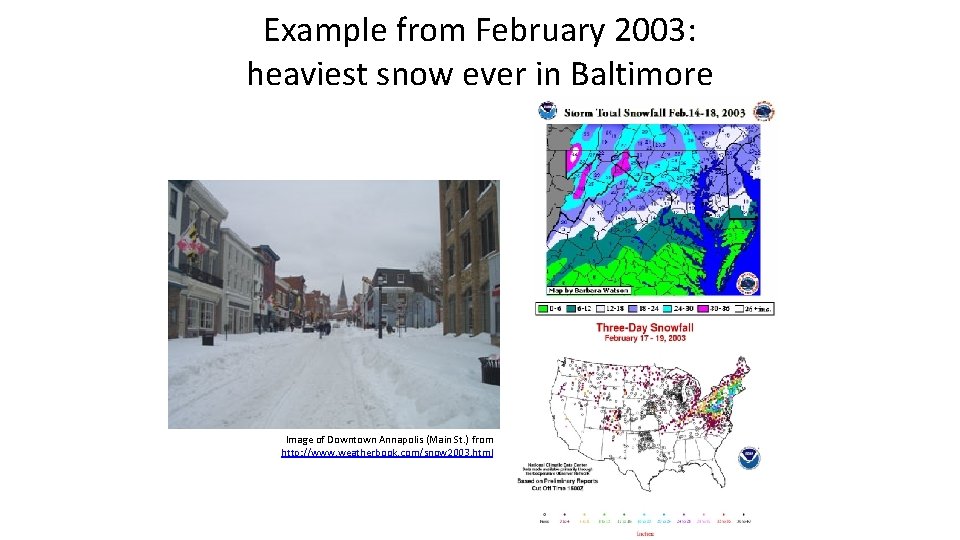

Example from February 2003: heaviest snow ever in Baltimore Image of Downtown Annapolis (Main St. ) from http: //www. weatherbook. com/snow 2003. html

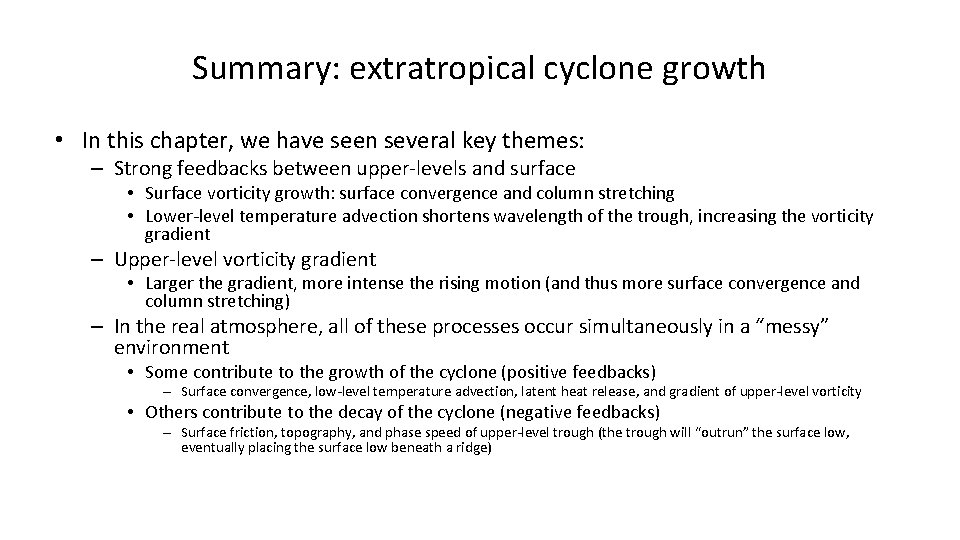

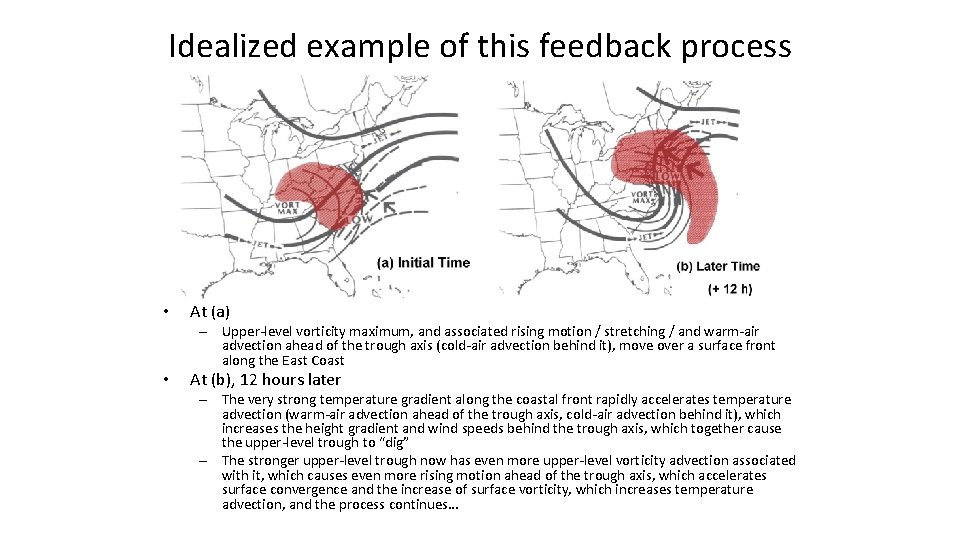

Idealized example of this feedback process • At (a) – Upper-level vorticity maximum, and associated rising motion / stretching / and warm-air advection ahead of the trough axis (cold-air advection behind it), move over a surface front along the East Coast • At (b), 12 hours later – The very strong temperature gradient along the coastal front rapidly accelerates temperature advection (warm-air advection ahead of the trough axis, cold-air advection behind it), which increases the height gradient and wind speeds behind the trough axis, which together cause the upper-level trough to “dig” – The stronger upper-level trough now has even more upper-level vorticity advection associated with it, which causes even more rising motion ahead of the trough axis, which accelerates surface convergence and the increase of surface vorticity, which increases temperature advection, and the process continues…

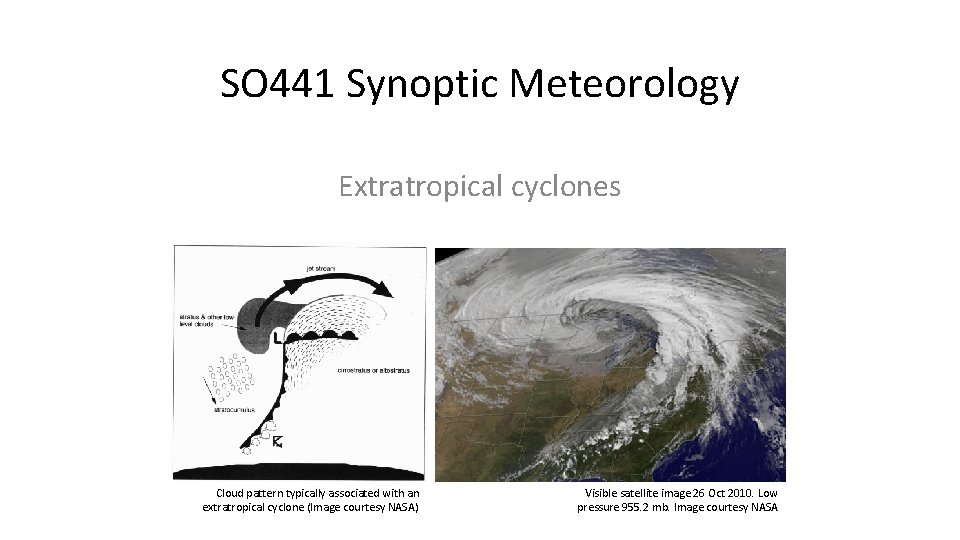

Summary: extratropical cyclone growth • In this chapter, we have seen several key themes: – Strong feedbacks between upper-levels and surface • Surface vorticity growth: surface convergence and column stretching • Lower-level temperature advection shortens wavelength of the trough, increasing the vorticity gradient – Upper-level vorticity gradient • Larger the gradient, more intense the rising motion (and thus more surface convergence and column stretching) – In the real atmosphere, all of these processes occur simultaneously in a “messy” environment • Some contribute to the growth of the cyclone (positive feedbacks) – Surface convergence, low-level temperature advection, latent heat release, and gradient of upper-level vorticity • Others contribute to the decay of the cyclone (negative feedbacks) – Surface friction, topography, and phase speed of upper-level trough (the trough will “outrun” the surface low, eventually placing the surface low beneath a ridge)