Snack Time Intervention for Preschoolers with ASD Fun

- Slides: 1

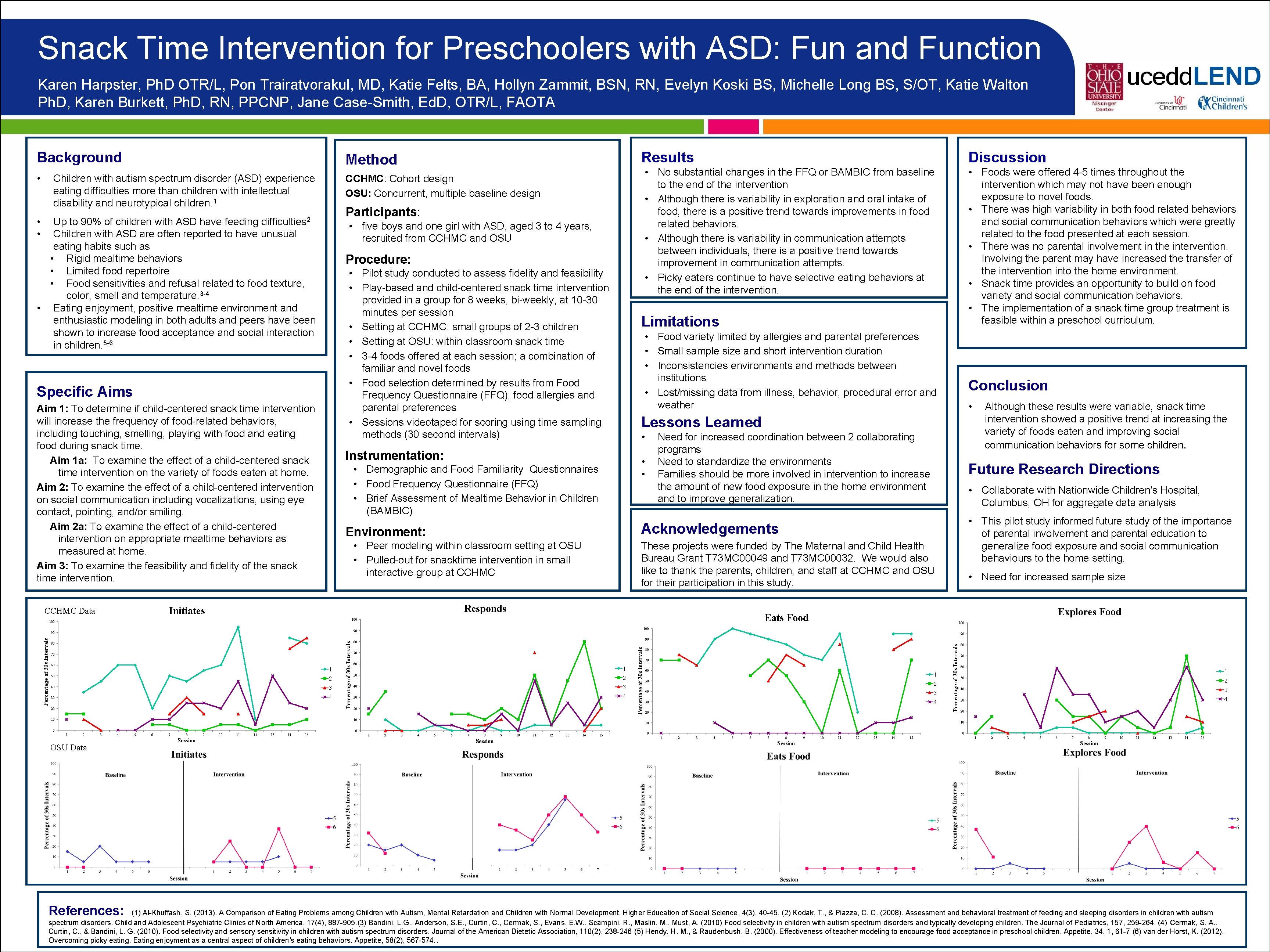

Snack Time Intervention for Preschoolers with ASD: Fun and Function Karen Harpster, Ph. D OTR/L, Pon Trairatvorakul, MD, Katie Felts, BA, Hollyn Zammit, BSN, RN, Evelyn Koski BS, Michelle Long BS, S/OT, Katie Walton Ph. D, Karen Burkett, Ph. D, RN, PPCNP, Jane Case-Smith, Ed. D, OTR/L, FAOTA Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) experience eating difficulties more than children with intellectual disability and neurotypical children. 1 CCHMC: Cohort design OSU: Concurrent, multiple baseline design Participants: • • Up to 90% of children with ASD have feeding difficulties 2 Children with ASD are often reported to have unusual eating habits such as • Rigid mealtime behaviors • Limited food repertoire • Food sensitivities and refusal related to food texture, color, smell and temperature. 3 -4 • Eating enjoyment, positive mealtime environment and enthusiastic modeling in both adults and peers have been shown to increase food acceptance and social interaction in children. 5 -6 • five boys and one girl with ASD, aged 3 to 4 years, recruited from CCHMC and OSU Procedure: • Pilot study conducted to assess fidelity and feasibility • Play-based and child-centered snack time intervention provided in a group for 8 weeks, bi-weekly, at 10 -30 minutes per session • Setting at CCHMC: small groups of 2 -3 children • Setting at OSU: within classroom snack time • 3 -4 foods offered at each session; a combination of familiar and novel foods • Food selection determined by results from Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ), food allergies and parental preferences • Sessions videotaped for scoring using time sampling methods (30 second intervals) Specific Aims Aim 1: To determine if child-centered snack time intervention will increase the frequency of food-related behaviors, including touching, smelling, playing with food and eating food during snack time. Aim 1 a: To examine the effect of a child-centered snack time intervention on the variety of foods eaten at home. Aim 2: To examine the effect of a child-centered intervention on social communication including vocalizations, using eye contact, pointing, and/or smiling. Aim 2 a: To examine the effect of a child-centered intervention on appropriate mealtime behaviors as measured at home. Aim 3: To examine the feasibility and fidelity of the snack time intervention. • 2 3 40 4 30 20 10 Percentage of 30 s Intervals 50 1 2 3 4 OSU Data References: 5 6 7 8 Session 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 • Need for increased sample size Explores Food 100 90 90 80 70 60 1 50 2 3 40 4 30 20 10 0 • This pilot study informed future study of the importance of parental involvement and parental education to generalize food exposure and social communication behaviours to the home setting. Eats Food 90 1 • Collaborate with Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH for aggregate data analysis These projects were funded by The Maternal and Child Health Bureau Grant T 73 MC 00049 and T 73 MC 00032. We would also like to thank the parents, children, and staff at CCHMC and OSU for their participation in this study. 100 60 Although these results were variable, snack time intervention showed a positive trend at increasing the variety of foods eaten and improving social communication behaviors for some children. Future Research Directions Acknowledgements Responds 70 • Need for increased coordination between 2 collaborating programs Need to standardize the environments Families should be more involved in intervention to increase the amount of new food exposure in the home environment and to improve generalization. • • • Peer modeling within classroom setting at OSU • Pulled-out for snacktime intervention in small interactive group at CCHMC 80 Conclusion Lessons Learned Environment: 90 Percentage of 30 s Intervals • Food variety limited by allergies and parental preferences • Small sample size and short intervention duration • Inconsistencies environments and methods between institutions • Lost/missing data from illness, behavior, procedural error and weather • Demographic and Food Familiarity Questionnaires • Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) • Brief Assessment of Mealtime Behavior in Children (BAMBIC) 100 • Foods were offered 4 -5 times throughout the intervention which may not have been enough exposure to novel foods. • There was high variability in both food related behaviors and social communication behaviors which were greatly related to the food presented at each session. • There was no parental involvement in the intervention. Involving the parent may have increased the transfer of the intervention into the home environment. • Snack time provides an opportunity to build on food variety and social communication behaviors. • The implementation of a snack time group treatment is feasible within a preschool curriculum. Limitations Instrumentation: Initiates CCHMC Data Discussion • No substantial changes in the FFQ or BAMBIC from baseline to the end of the intervention • Although there is variability in exploration and oral intake of food, there is a positive trend towards improvements in food related behaviors. • Although there is variability in communication attempts between individuals, there is a positive trend towards improvement in communication attempts. • Picky eaters continue to have selective eating behaviors at the end of the intervention. Percentage of 30 s Intervals • Results Method 80 70 60 1 50 2 40 3 30 4 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Session 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 80 70 60 1 50 2 40 3 30 4 20 10 10 0 Percentage of 30 s Intervals Background 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Session 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Session (1) Al-Khuffash, S. (2013). A Comparison of Eating Problems among Children with Autism, Mental Retardation and Children with Normal Development. Higher Education of Social Science, 4(3), 40 -45. (2) Kodak, T. , & Piazza, C. C. (2008). Assessment and behavioral treatment of feeding and sleeping disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 17(4), 887 -905. (3) Bandini, L. G. , Anderson, S. E. , Curtin, C. , Cermak, S. , Evans, E. W. , Scampini, R. , Maslin, M. , Must, A. (2010) Food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorders and typically developing children. The Journal of Pediatrics, 157, 259 -264. (4) Cermak, S. A. , Curtin, C. , & Bandini, L. G. (2010). Food selectivity and sensory sensitivity in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 110(2), 238 -246 (5) Hendy, H. M. , & Raudenbush, B. (2000). Effectiveness of teacher modeling to encourage food acceptance in preschool children. Appetite, 34, 1, 61 -7 (6) van der Horst, K. (2012). Overcoming picky eating. Eating enjoyment as a central aspect of children's eating behaviors. Appetite, 58(2), 567 -574. .