Slides by Iddo Tzameret and Gil Shklarski Adapted

Slides by Iddo Tzameret and Gil Shklarski. Adapted from Oded Goldreich’s course lecture notes by Erez Waisbard and Gera Weiss. 1

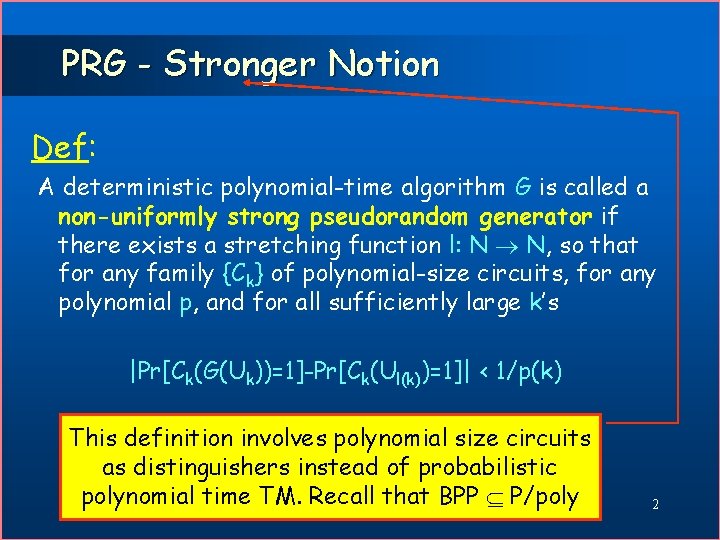

PRG - Stronger Notion Def: A deterministic polynomial-time algorithm G is called a non-uniformly strong pseudorandom generator if there exists a stretching function l: N N, so that for any family {Ck} of polynomial-size circuits, for any polynomial p, and for all sufficiently large k’s |Pr[Ck(G(Uk))=1]-Pr[Ck(Ul(k))=1]| < 1/p(k) This definition involves polynomial size circuits as distinguishers instead of probabilistic polynomial time TM. Recall that BPP P/poly 2

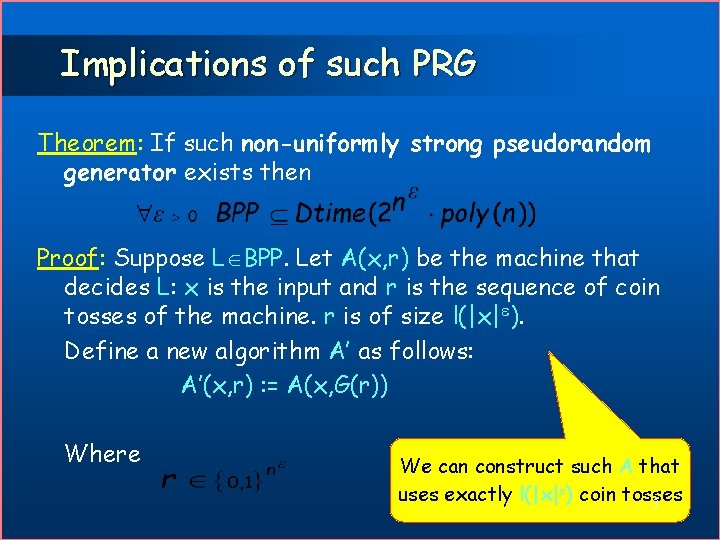

Implications of such PRG Theorem: If such non-uniformly strong pseudorandom generator exists then Proof: Suppose L BPP. Let A(x, r) be the machine that decides L: x is the input and r is the sequence of coin tosses of the machine. r is of size l(|x| ). Define a new algorithm A’ as follows: A’(x, r) : = A(x, G(r)) Where We can construct such A that uses exactly l(|x| ) coin tosses 3

![Proof Continued (1( Claim: For all but finitely many x’s |Pr[A(x, Ul(k))=1] - Pr[A’(x, Proof Continued (1( Claim: For all but finitely many x’s |Pr[A(x, Ul(k))=1] - Pr[A’(x,](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e2576c773c2db623a25a17b6c1595084/image-4.jpg)

Proof Continued (1( Claim: For all but finitely many x’s |Pr[A(x, Ul(k))=1] - Pr[A’(x, Uk)=1]| < 1/6 where k=|x|. Proof: Assume, by way of contradiction, that, for infinitely many x’s |Pr[A(x, Ul(k))=1] - Pr[A’(x, Uk)=1]| 1/6 and construct a family of poly-size circuits x C(x)(input) : = A(x, input) then construct the family {Ck} as follows: Ck {C(x)| A(x) uses l(k) coin tosses} Infinitely many x’s on which A and A’ differ imply infinitely many 4 sizes of x’s on which they differ, and infinite number of such Cks.

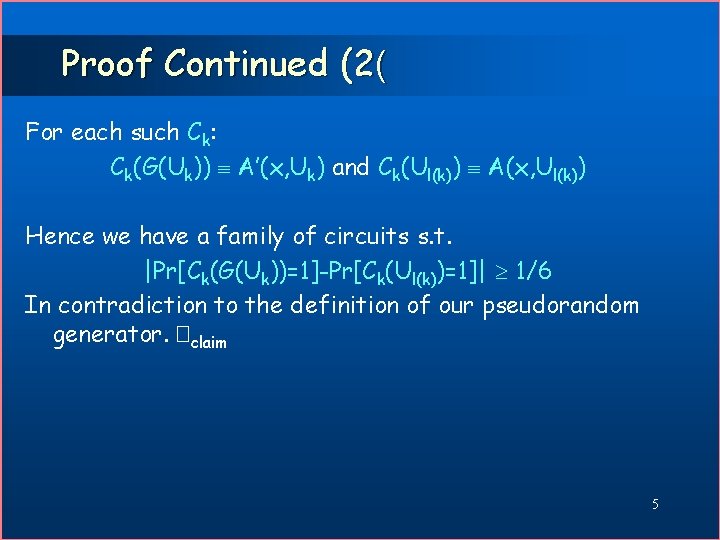

Proof Continued (2( For each such Ck: Ck(G(Uk)) A’(x, Uk) and Ck(Ul(k)) A(x, Ul(k)) Hence we have a family of circuits s. t. |Pr[Ck(G(Uk))=1]-Pr[Ck(Ul(k))=1]| 1/6 In contradiction to the definition of our pseudorandom generator. �claim 5

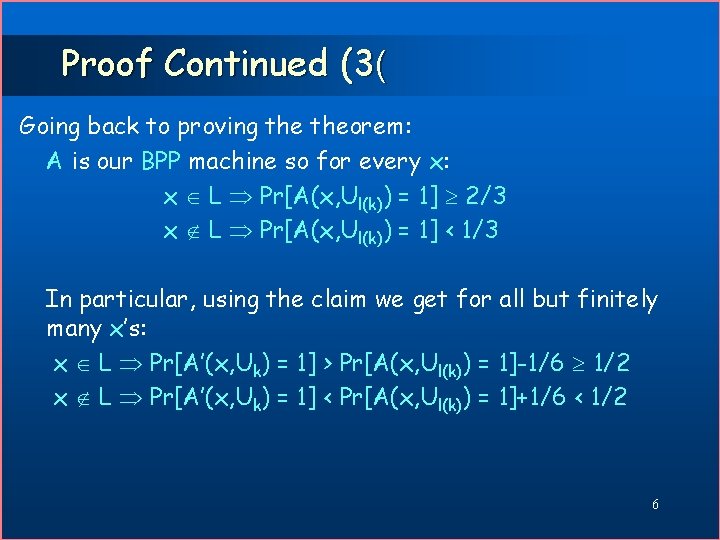

Proof Continued (3( Going back to proving theorem: A is our BPP machine so for every x: x L Pr[A(x, Ul(k)) = 1] 2/3 x L Pr[A(x, Ul(k)) = 1] < 1/3 In particular, using the claim we get for all but finitely many x’s: x L Pr[A’(x, Uk) = 1] > Pr[A(x, Ul(k)) = 1]-1/6 1/2 x L Pr[A’(x, Uk) = 1] < Pr[A(x, Ul(k)) = 1]+1/6 < 1/2 6

Proof Continued (4( Now, define a deterministic algorithm A’’ for deciding L: if x is one of those finitely x’s return a known pre-computed answer else { for all Run A’(x, r) return the majority of A’ answers. } A’’ deterministically decides L and run in time as required. �Theorem 7

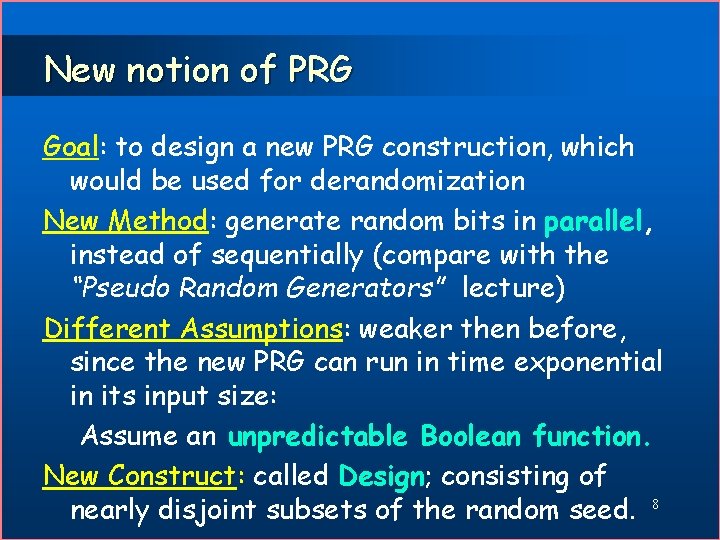

New notion of PRG Goal: to design a new PRG construction, which would be used for derandomization New Method: generate random bits in parallel, instead of sequentially (compare with the “Pseudo Random Generators” lecture) Different Assumptions: weaker then before, since the new PRG can run in time exponential in its input size: Assume an unpredictable Boolean function. New Construct: called Design; consisting of nearly disjoint subsets of the random seed. 8

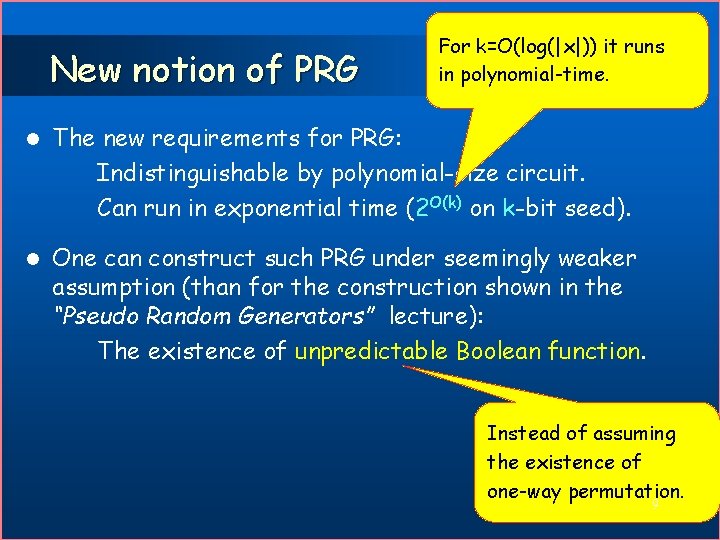

New notion of PRG For k=O(log(|x|)) it runs in polynomial-time. l The new requirements for PRG: Indistinguishable by polynomial-size circuit. Can run in exponential time (2 O(k) on k-bit seed). l One can construct such PRG under seemingly weaker assumption (than for the construction shown in the “Pseudo Random Generators” lecture): The existence of unpredictable Boolean function. Instead of assuming the existence of one-way permutation. 9

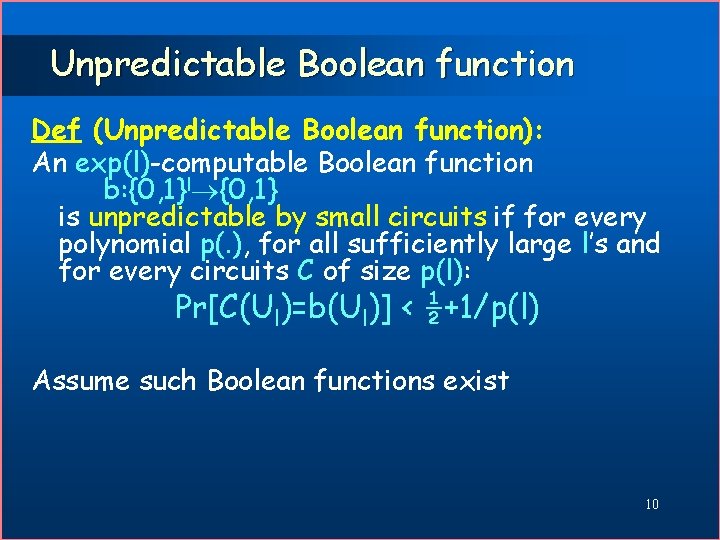

Unpredictable Boolean function Def (Unpredictable Boolean function): An exp(l)-computable Boolean function b: {0, 1}l {0, 1} is unpredictable by small circuits if for every polynomial p(. ), for all sufficiently large l’s and for every circuits C of size p(l): Pr[C(Ul)=b(Ul)] < ½+1/p(l) Assume such Boolean functions exist 10

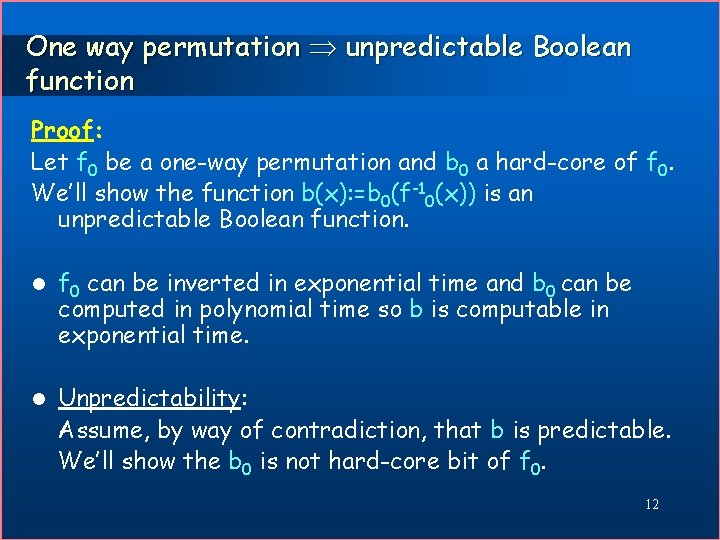

Unpredictable Boolean function How strong is that assumption? We prove that it is not stronger than assuming the existence of a one-way permutation: ? one-way permutation unpredictable Boolean function Claim: if f 0 is a one-way permutation and b 0 is a hard-core of f 0, then b(x): =b 0(f 0 -1(x)) is an unpredictable Boolean function. 11

One way permutation unpredictable Boolean function Proof: Let f 0 be a one-way permutation and b 0 a hard-core of f 0. We’ll show the function b(x): =b 0(f-10(x)) is an unpredictable Boolean function. l f 0 can be inverted in exponential time and b 0 can be computed in polynomial time so b is computable in exponential time. l Unpredictability: Assume, by way of contradiction, that b is predictable. We’ll show the b 0 is not hard-core bit of f 0. 12

Proof continued Assuming b is predictable we have a family of circuits {Ck} of size p(k) s. t. for infinite number of k’s Pr[Ck(Uk)=b(Uk)] 1/2 + 1/p(l). For y: =f 0 -1 (x) we get b(f 0(y))=b 0(y). f is a permutation so we get Pr[Ck(f 0(Uk))=b(f 0(Uk))] 1/2 + 1/p(l) Pr[Ck(f 0(Uk))=b 0(Uk)] 1/2 + 1/p(l). Which is a contradiction to b 0 being a hard core. We defined hard-core bit with BPP machines and 13 not P/poly so there is a problem here !

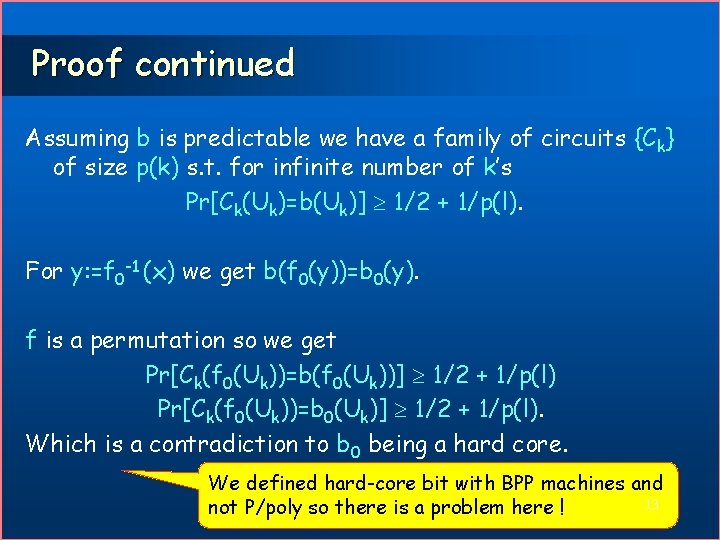

The Design Generating a single random bit from a seed is easy assuming you have an unpredictable Boolean function. l But how can we generate more than one bit? We will manage that, utlizing a collection of nearly disjoined subsets of the seed to get random bits that are almost mutually independent l Almost means: indistinguishable by polynomial sized circuits 14

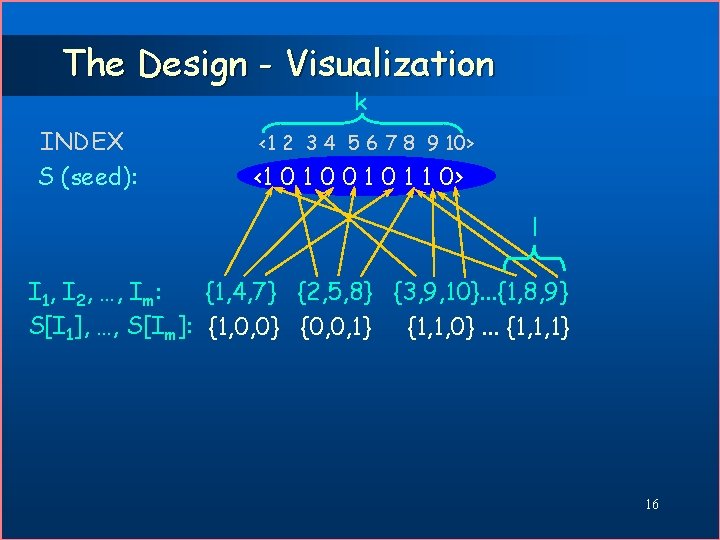

The Design Def: A collection of m subsets {I 1, I 2, …, Im} of {1…k} is a (k, m, l)-design if the following hold: l For every i {1, …, m}: |Ii| = l l For every i j {1, …, m}: |Ii Ij| = O(log k) l The collection is constructible in exp(k)-time. Notation: For S=<x 1, x 2, …, xk> and I={i 1, …, il} {1, . . , k} 15

The Design - Visualization k INDEX S (seed): <1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10> <1 0 0 1 1 0> l I 1, I 2, …, Im: {1, 4, 7} {2, 5, 8} {3, 9, 10}. . . {1, 8, 9} S[I 1], …, S[Im]: {1, 0, 0} {0, 0, 1} {1, 1, 0}. . . {1, 1, 1} 16

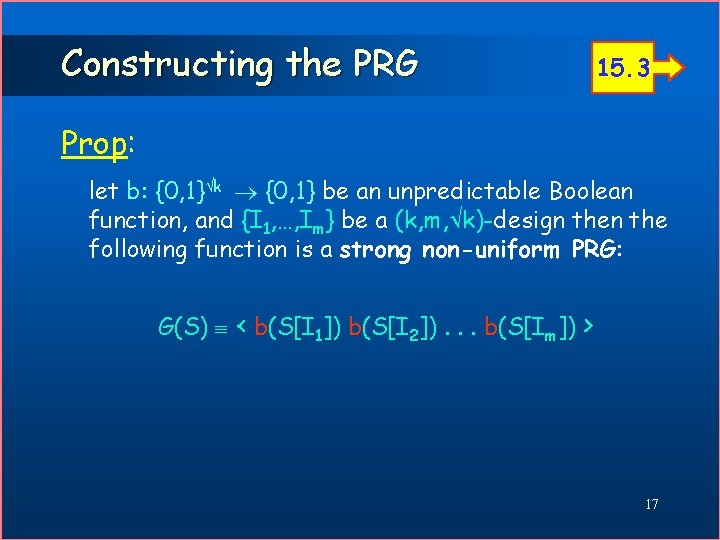

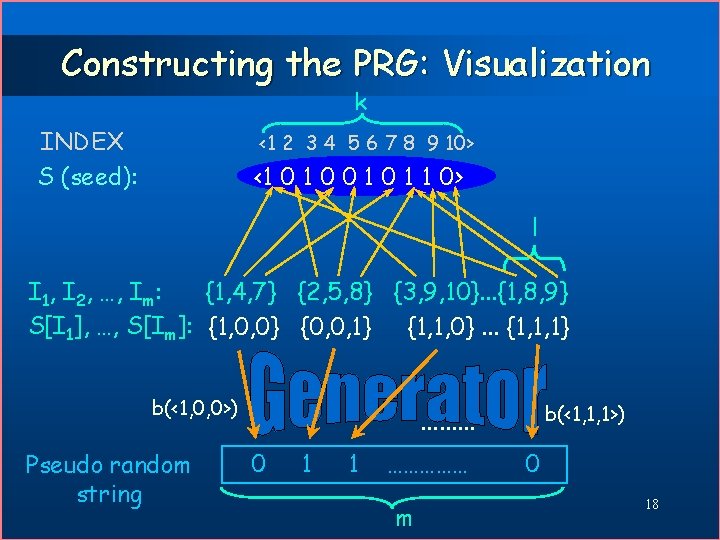

Constructing the PRG 15. 3 Prop: let b: {0, 1} k {0, 1} be an unpredictable Boolean function, and {I 1, …, Im} be a (k, m, k)-design the following function is a strong non-uniform PRG: G(S) < b(S[I 1]) b(S[I 2]). . . b(S[Im]) > 17

Constructing the PRG: Visualization k INDEX S (seed): <1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10> <1 0 0 1 1 0> l I 1, I 2, …, Im: {1, 4, 7} {2, 5, 8} {3, 9, 10}. . . {1, 8, 9} S[I 1], …, S[Im]: {1, 0, 0} {0, 0, 1} {1, 1, 0}. . . {1, 1, 1} b(<1, 0, 0>) Pseudo random string ……… 0 1 1 …………… m b(<1, 1, 1>) 0 18

Proof (1( Proof: Computing G(s) takes time exponential in k, since: l we have m=l(k) computations of b(S[Ii]); l Computing each b(S[Ii]) takes exp( |S[Ii]| ) = O(exp(k)). 19

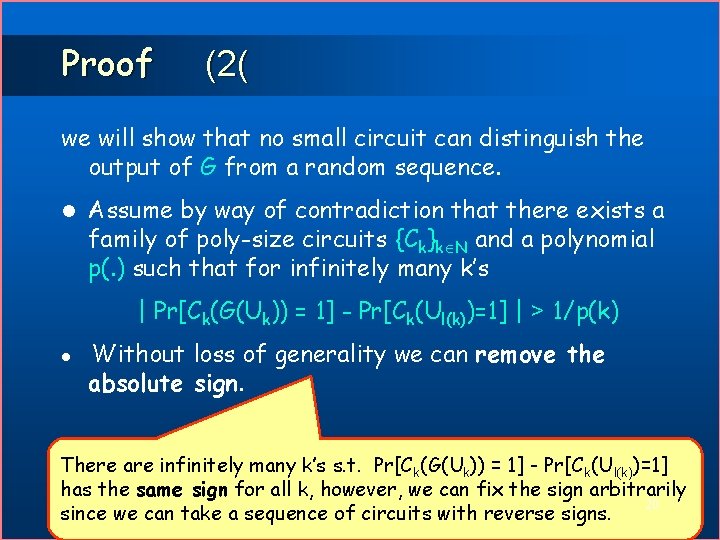

Proof (2( we will show that no small circuit can distinguish the output of G from a random sequence. l Assume by way of contradiction that there exists a family of poly-size circuits {Ck}k N and a polynomial p(. ) such that for infinitely many k’s | Pr[Ck(G(Uk)) = 1] - Pr[Ck(Ul(k))=1] | > 1/p(k) l Without loss of generality we can remove the absolute sign. There are infinitely many k’s s. t. Pr[Ck(G(Uk)) = 1] - Pr[Ck(Ul(k))=1] has the same sign for all k, however, we can fix the sign arbitrarily 20 since we can take a sequence of circuits with reverse signs.

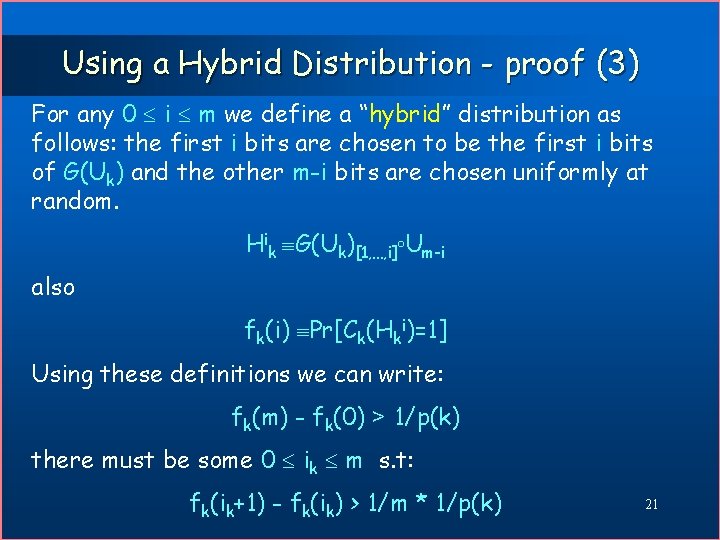

Using a Hybrid Distribution - proof (3) For any 0 i m we define a “hybrid” distribution as follows: the first i bits are chosen to be the first i bits of G(Uk) and the other m-i bits are chosen uniformly at random. Hik G(Uk)[1, …, i] Um-i also fk(i) Pr[Ck(Hki)=1] Using these definitions we can write: fk(m) - fk(0) > 1/p(k) there must be some 0 ik m s. t: fk(ik+1) - fk(ik) > 1/m * 1/p(k) 21

Approximating the Next bit from the previous bits Defining p’(k): =m p(k) and i: =ik we get: Pr[Ck(Hki+1)=1]- Pr[Ck(Hki)=1] > 1/p’(k) Now, we can construct from Ck a circuit C’k which can approximate the next bit with large enough probability: When Ri are independent uniformly distributed bits. It can be shown that Probability over random bits Ri and Uk Pr[C’k(G(Uk)[1, …i] ) = G(Uk)i+1] > 1/2 + 1/p’(k) 22

![Approximating the Next bit from the previous bits b(S[I 1]) ½- …… b(S[Iik]) Next Approximating the Next bit from the previous bits b(S[I 1]) ½- …… b(S[Iik]) Next](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e2576c773c2db623a25a17b6c1595084/image-23.jpg)

Approximating the Next bit from the previous bits b(S[I 1]) ½- …… b(S[Iik]) Next bit ½+ b(S[Iik+1]) : =1/p’(k) Circuit C‘ k 23

![Approximating b(S[Ii+1]) from S and b(S[Ii])’s We can construct a circuit C’’ which inputs Approximating b(S[Ii+1]) from S and b(S[Ii])’s We can construct a circuit C’’ which inputs](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e2576c773c2db623a25a17b6c1595084/image-24.jpg)

Approximating b(S[Ii+1]) from S and b(S[Ii])’s We can construct a circuit C’’ which inputs S in addition to b(S[I 1]), …, b(S[Ii]) and can approximate the unpredictable boolean function b(S[Ii+1]). This can be done by ‘ignoring’ those new inputs and using b(S[I 1]), …, b(S[Ii]) and C’. The formal definition is: C’’k(S°G(S)[1. . i]) : = C’k(G(S)[1. . i]) We get: Prs[C’’k(S°G(S)[1. . i] ) = G(S)i+1] > 1/2 + 1/p’(k) Prs[C’’k(S°G(S)[1. . i] ) = b(S[Ii+1])] > 1/2 + 1/p’(k) Probabilities over random bits Ri and S 24

![Approximating b(S[Ii+1]) from S[Ii+1] and b(S[Ij])’s There exist {0, 1}k-|Ii| s. t. Prs[C’’k(S°G(S)[1. . Approximating b(S[Ii+1]) from S[Ii+1] and b(S[Ij])’s There exist {0, 1}k-|Ii| s. t. Prs[C’’k(S°G(S)[1. .](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e2576c773c2db623a25a17b6c1595084/image-25.jpg)

Approximating b(S[Ii+1]) from S[Ii+1] and b(S[Ij])’s There exist {0, 1}k-|Ii| s. t. Prs[C’’k(S°G(S)[1. . i] ) = b(S[Ii+1]) | S[Ii+1]= ] > 1/2 + 1/p’(k) We’ll hard-code this into our circuit and get a circuit that takes b(S[I 1]), …, b(S[Ii]) and S[Ii+1] as inputs and approximate b(S[Ii+1]) with some bias. Applying the Law of Averages: Pr[C’’k(S°G(S)[1. . i] ) = b(S[Ii+1])] = Pr [C’’k(S°G(S)[1. . i] ) = b(S[Ii+1]) | S[Ii+1]= ] • Pr[S[Ii+1]= ] If for all : Pr [C’’k(S°G(S)[1. . i] ) = b(S[Ii+1]) | S[Ii+1]= ] 1/2+1/p’(k) We’d get Pr[C’’k(S°G(S)[1. . i] ) = b(S[Ii+1])] 1/2+1/p’(k). 25

![Visualization of C’’ S[Ii+1]) S: b(S[I 1])… b(S[Ii]) Circuit C‘’ k …… ½- ½+ Visualization of C’’ S[Ii+1]) S: b(S[I 1])… b(S[Ii]) Circuit C‘’ k …… ½- ½+](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e2576c773c2db623a25a17b6c1595084/image-26.jpg)

Visualization of C’’ S[Ii+1]) S: b(S[I 1])… b(S[Ii]) Circuit C‘’ k …… ½- ½+ Circuit C‘k Next bit b(S[Ii+1]) 26

![Approximating b(S[Ii+1]) from S[Ii+1] We know how to approximate b(S[Ii+1]) from its input S[Ii+1] Approximating b(S[Ii+1]) from S[Ii+1] We know how to approximate b(S[Ii+1]) from its input S[Ii+1]](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e2576c773c2db623a25a17b6c1595084/image-27.jpg)

Approximating b(S[Ii+1]) from S[Ii+1] We know how to approximate b(S[Ii+1]) from its input S[Ii+1] and from b(S[I 1]), …, b(S[Ii]). Can we approximate it using only S[Ii+1] ? 27

![Computing S[Ij]’s from S[Ii+1] After hard-coding , S: there is only a small number Computing S[Ij]’s from S[Ii+1] After hard-coding , S: there is only a small number](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e2576c773c2db623a25a17b6c1595084/image-28.jpg)

Computing S[Ij]’s from S[Ii+1] After hard-coding , S: there is only a small number of free bits in S[I 1]…S[Ii]. The design gives us i • O(log(k)) as a bound. =S[Ii+1]) ? S[I 1] S[Ii+1] ? ? S[I 2] ……… ? S[Ii] O(log(k)) 28

![Computing S[Ij]’s from S[Ii+1] Example S[Ii+1] S: S[Ii+10]) 1 0 0 = 1 ……… Computing S[Ij]’s from S[Ii+1] Example S[Ii+1] S: S[Ii+10]) 1 0 0 = 1 ………](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e2576c773c2db623a25a17b6c1595084/image-29.jpg)

Computing S[Ij]’s from S[Ii+1] Example S[Ii+1] S: S[Ii+10]) 1 0 0 = 1 ……… precomputed S[I 1 i+1] ? ? ? 0 1 1 b(<0010>) b(<0011>) ? < 0 0 1 1? > S[I 1] <1 0 1 ? ? > S[I 2] ……… … <0? 1 1 ? > S[Ii] O(log(k)) 29

![Computing b(S[Ii+1])’s from S[Ii+1] Exp(log(k))= S: 1 2 3 ……… j ? ? j+1… Computing b(S[Ii+1])’s from S[Ii+1] Exp(log(k))= S: 1 2 3 ……… j ? ? j+1…](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e2576c773c2db623a25a17b6c1595084/image-30.jpg)

Computing b(S[Ii+1])’s from S[Ii+1] Exp(log(k))= S: 1 2 3 ……… j ? ? j+1… k-l poly(k) circuit S[I 1] ………S[Ii] Lookup table: for every possible S[Ii] return precomputed value of b(S[Ii]) b(S[I 1])……… b(S[Ii]) < 1 2 3 ? > S[I 1] < 3 j-1 j ? > S[I 2] There are only poly(k) possible such S[Ii]’s, given S[Ii+1]= . … <? j+1 j+2 k-l > S[Ii] 30

![Final Circuit: Approximating b(S[Ii+1]) from S[Ii+1] poly(k) circuit S[I 1] ………S[Ii] Lookup table b(S[I Final Circuit: Approximating b(S[Ii+1]) from S[Ii+1] poly(k) circuit S[I 1] ………S[Ii] Lookup table b(S[I](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e2576c773c2db623a25a17b6c1595084/image-31.jpg)

Final Circuit: Approximating b(S[Ii+1]) from S[Ii+1] poly(k) circuit S[I 1] ………S[Ii] Lookup table b(S[I 1]) … b(S[Ii]) ½- ½+ Circuit C‘ Next bit b(S[Ii+1]) 31

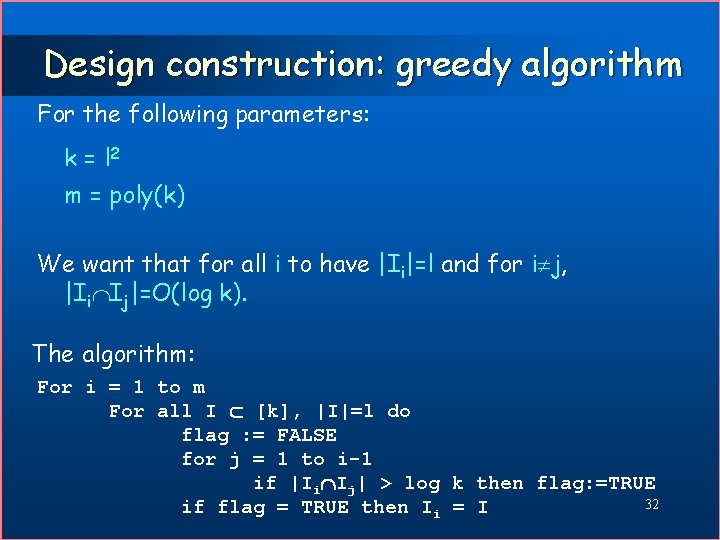

Design construction: greedy algorithm For the following parameters: k = l 2 m = poly(k) We want that for all i to have |Ii|=l and for i j, |Ii Ij|=O(log k). The algorithm: For i = 1 to m For all I [k], |I|=l do flag : = FALSE for j = 1 to i-1 if |Ii Ij| > log k then flag: =TRUE 32 if flag = TRUE then Ii = I

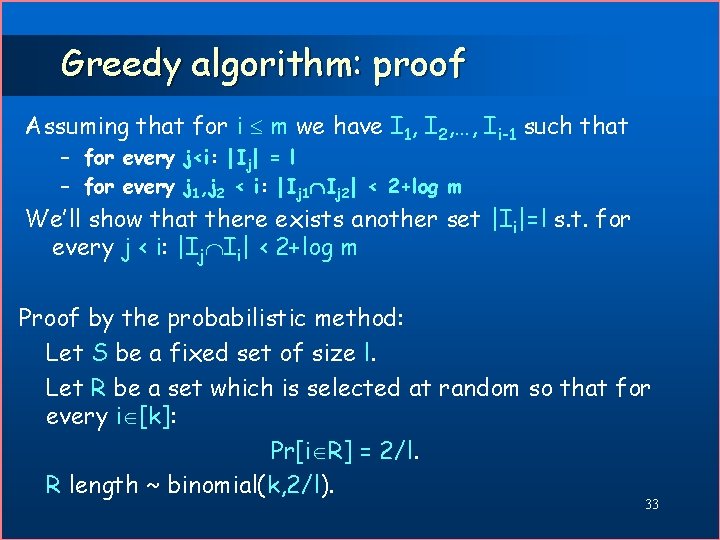

Greedy algorithm: proof Assuming that for i m we have I 1, I 2, …, Ii-1 such that – for every j<i: |Ij| = l – for every j 1, j 2 < i: |Ij 1 Ij 2| < 2+log m We’ll show that there exists another set |Ii|=l s. t. for every j < i: |Ij Ii| < 2+log m Proof by the probabilistic method: Let S be a fixed set of size l. Let R be a set which is selected at random so that for every i [k]: Pr[i R] = 2/l. R length ~ binomial(k, 2/l). 33

Proof continued (1( Let Si be the i’th element in S sorted in some order. We’ll define the sequence {Xi}i=1. . l of random variables: Xi are independent Bernoulli variables with Pr[Xi=1]= 2/l for each i. Using Chernoff’s bound: 34

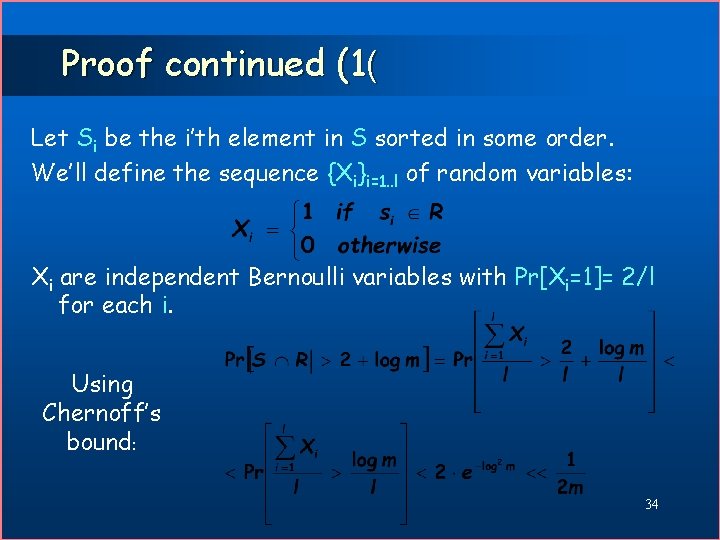

Proof continued (2( For R selected as above the probability that there exists Ij s. t. |Ij R| > 2+log m us bounded above by (i-1)/2 m < 1/2. R is not necessarily of size l. We can show that with high Note: The algorithm itself probability |R| l so it contains a subset of size l that we is deterministic. We use can choose as our Ii. the randomness as a tool in Considering the sequence {Xi}i=1. . l : will showing the algorithm always find what it is looking for. Using Chernoff’s bound: For R selected as above the probability of too many collisions or being too small is strictly smaller than one. Therefore, there exists such R to be selected as Ii. � 35

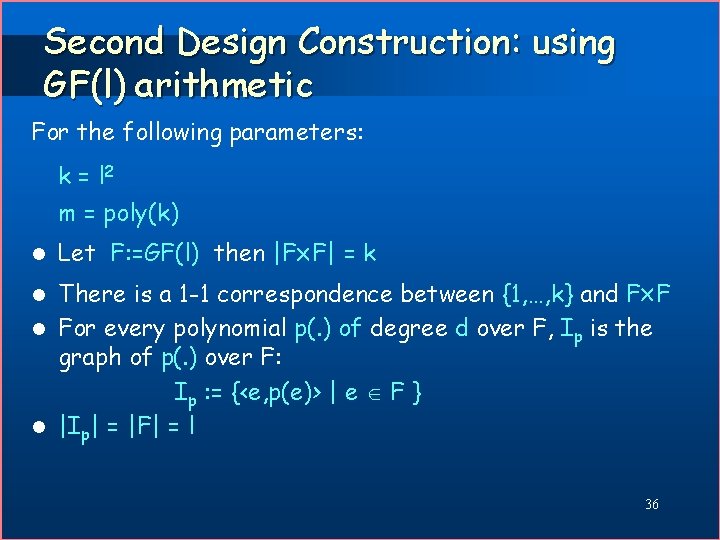

Second Design Construction: using GF(l) arithmetic For the following parameters: k = l 2 m = poly(k) l Let F: =GF(l) then |F F| = k There is a 1 -1 correspondence between {1, …, k} and F F l For every polynomial p(. ) of degree d over F, Ip is the graph of p(. ) over F: Ip : = {<e, p(e)> | e F } l |Ip| = |F| = l l 36

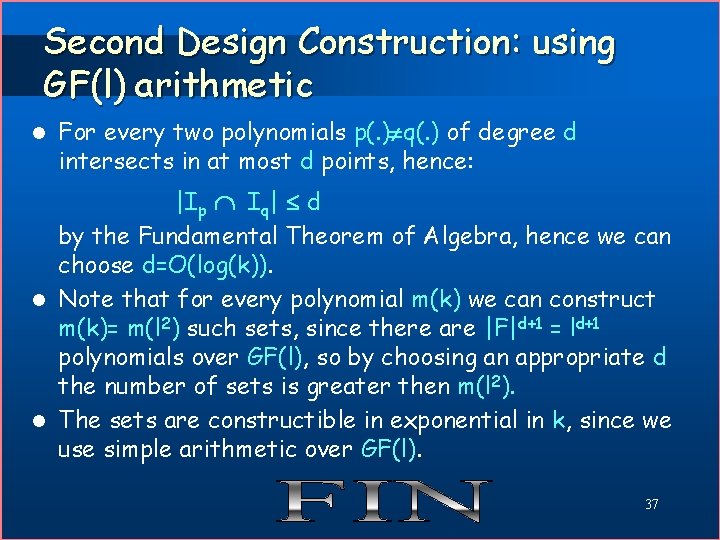

Second Design Construction: using GF(l) arithmetic l For every two polynomials p(. ) q(. ) of degree d intersects in at most d points, hence: |Ip Iq| d by the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra, hence we can choose d=O(log(k)). l Note that for every polynomial m(k) we can construct m(k)= m(l 2) such sets, since there are |F|d+1 = ld+1 polynomials over GF(l), so by choosing an appropriate d the number of sets is greater then m(l 2). l The sets are constructible in exponential in k, since we use simple arithmetic over GF(l). 37

- Slides: 37