Slide 16 A 1 ObjectOriented and Classical Software

Slide 16 A. 1 Object-Oriented and Classical Software Engineering Sixth Edition, WCB/Mc. Graw-Hill, 2005 Stephen R. Schach srs@vuse. vanderbilt. edu © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

CHAPTER 16 — Unit A MORE ON UML © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005 Slide 16 A. 2

Chapter Overview l l l l l UML is not a methodology Class diagrams Notes Use-case diagrams Stereotypes Interaction diagrams Statecharts Activity diagrams Packages Component diagrams © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005 Slide 16 A. 3

Chapter Overview (contd) l l l Deployment diagrams Review of UML diagrams UML and iteration © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005 Slide 16 A. 4

The Current Version of UML l Slide 16 A. 5 Like all modern computer languages, UML is constantly changing 4 When this book was written, the latest version of UML was Version 1. 4 4 By now, some aspects of UML may have changed l UML is now under the control of the Object Management Group (OMG) 4 Check for updates at the OMG Web site, www. omg. org © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

16. 1 UML Is Not a Methodology l Slide 16 A. 6 UML is an acronym for Unified Modeling Language 4 UML is therefore a language l A language is simply a tool for expressing ideas © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

UML Is Not a Methodology l Slide 16 A. 7 UML is a notation, not a methodology 4 It can be used in conjunction with any methodology l UML is not merely a notation, it is the notation l UML has become a world standard 4 Every information technology professional today needs to know UML © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

UML Is Not a Methodology (contd) l Slide 16 A. 8 The title of this chapter is “More on UML” 4 Surely it should be “All of UML”? l The manual for Version 1. 4 of UML is nearly 600 pages long 4 Complete coverage is not possible l But surely every information technology professional must know every aspect of UML? © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

UML Is Not a Methodology (contd) Slide 16 A. 9 l UML is a language l The English language has over 100, 000 words 4 We can manage fine with just a subset l The small subset of UML presented in Chapters 7, 10, 12, and 13 is adequate for the purposes of this book l The larger subset of UML presented in this chapter is adequate for the development and maintenance of most software products © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

16. 2 Class Diagrams l A class diagram depicts classes and their interrelationships l Here is the simplest possible class diagram Figure 16. 1 © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005 Slide 16 A. 10

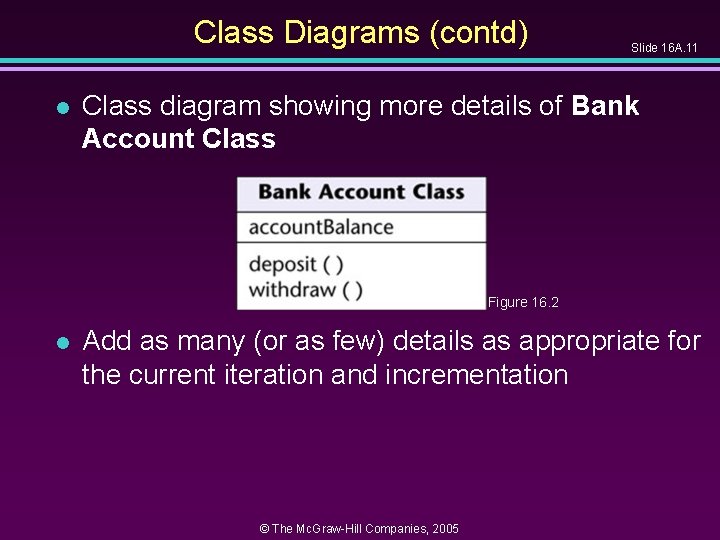

Class Diagrams (contd) l Slide 16 A. 11 Class diagram showing more details of Bank Account Class Figure 16. 2 l Add as many (or as few) details as appropriate for the current iteration and incrementation © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Class Diagrams: Notation (contd) l Freedom of notation extends to objects l Example: Slide 16 A. 12 4 bank account : Bank Account Class l bank account is an object, an instance of a class Bank Account Class 4 The underlining denotes an object 4 The colon denotes “an instance of” 4 The bold face and initial upper case letters in Bank Account Class denote that this is a class © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Class Diagrams: Notation (contd) l Slide 16 A. 13 UML allows a shorter notation when there is no ambiguity 4 bank account © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Class Diagrams: Notation (contd) l Slide 16 A. 14 The UML notation for modeling the concept of an arbitrary bank account is 4: Bank Account Class l The colon means “an instance of, ” so : Bank Account Class means “an instance of class Bank Account Class” l This notation has been used in the interaction diagrams of Chapter 12 © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Class Diagrams: Visibility Prefixes (contd) Slide 16 A. 15 l UML visibility prefixes (used for information hiding) 4 Prefix + indicates that an attribute or operation is public » Visible everywhere 4 Prefix – denotes that the attribute or operation is private » Visible only in the class in which it is defined 4 Prefix # denotes that the attribute or operation is protected » Visible either within the class in which it is defined or within subclasses of that class © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

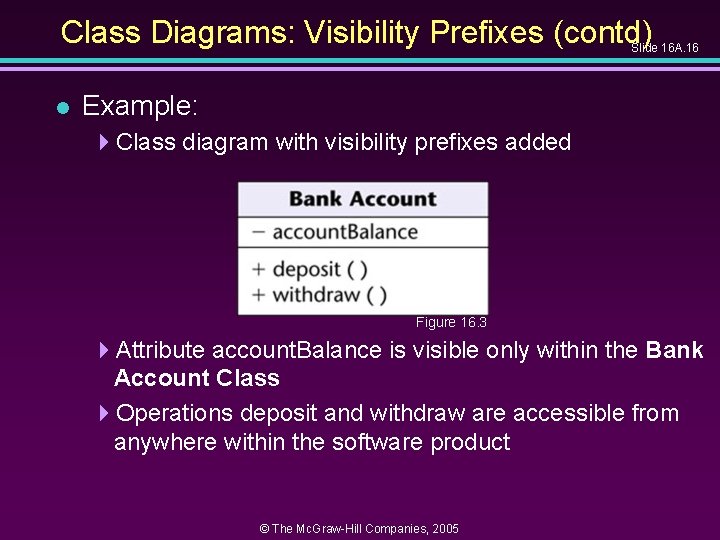

Class Diagrams: Visibility Prefixes (contd) Slide 16 A. 16 l Example: 4 Class diagram with visibility prefixes added Figure 16. 3 4 Attribute account. Balance is visible only within the Bank Account Class 4 Operations deposit and withdraw are accessible from anywhere within the software product © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

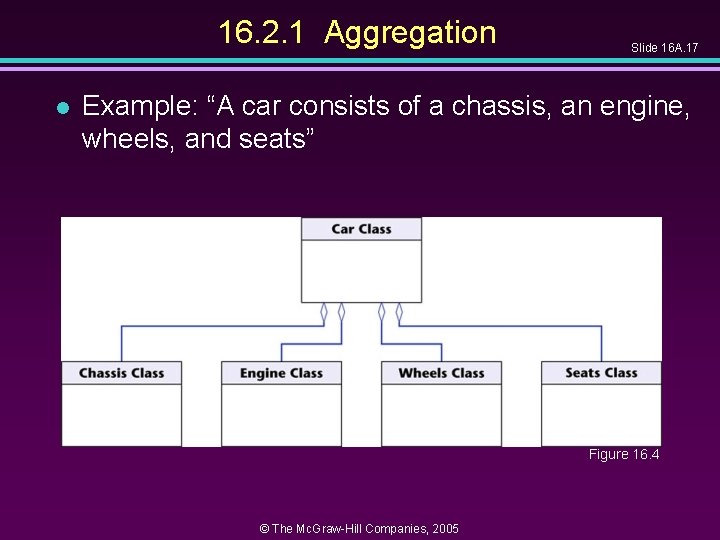

16. 2. 1 Aggregation l Slide 16 A. 17 Example: “A car consists of a chassis, an engine, wheels, and seats” Figure 16. 4 © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

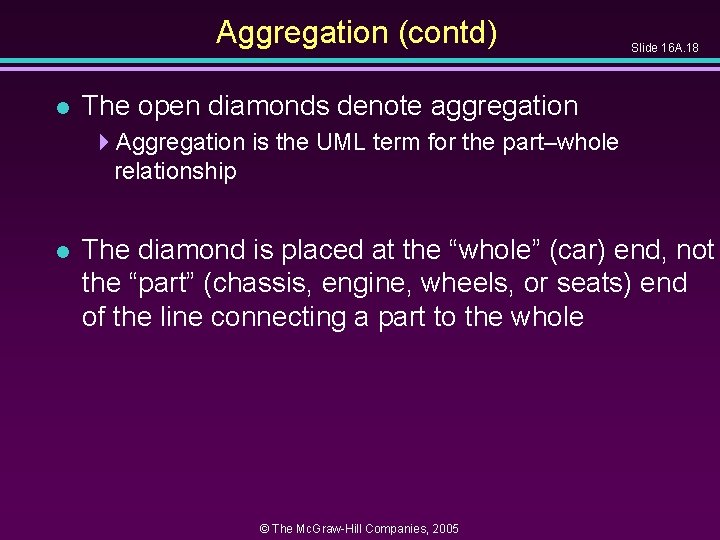

Aggregation (contd) l Slide 16 A. 18 The open diamonds denote aggregation 4 Aggregation is the UML term for the part–whole relationship l The diamond is placed at the “whole” (car) end, not the “part” (chassis, engine, wheels, or seats) end of the line connecting a part to the whole © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

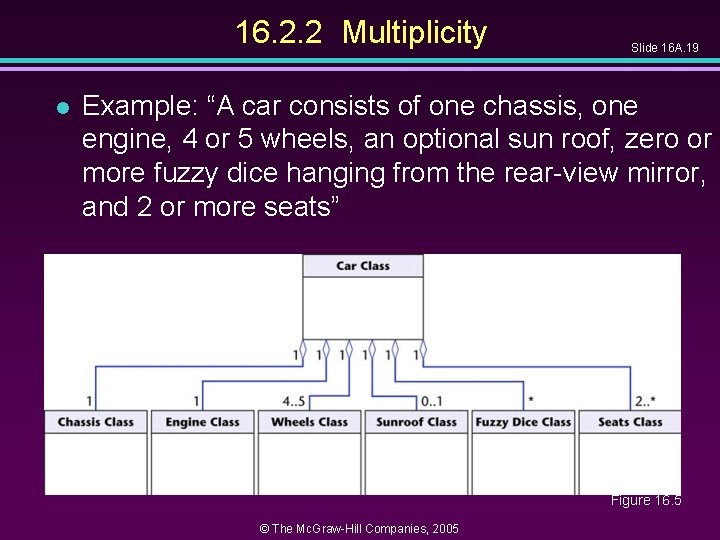

16. 2. 2 Multiplicity l Slide 16 A. 19 Example: “A car consists of one chassis, one engine, 4 or 5 wheels, an optional sun roof, zero or more fuzzy dice hanging from the rear-view mirror, and 2 or more seats” Figure 16. 5 © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Multiplicity (contd) l Slide 16 A. 20 The numbers next to the ends of the lines denote multiplicity 4 The number of times that the one class is associated with the other class © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

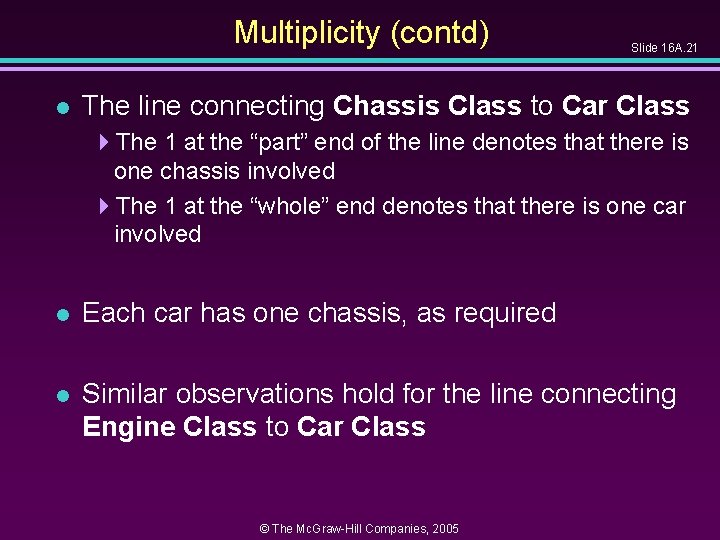

Multiplicity (contd) l Slide 16 A. 21 The line connecting Chassis Class to Car Class 4 The 1 at the “part” end of the line denotes that there is one chassis involved 4 The 1 at the “whole” end denotes that there is one car involved l Each car has one chassis, as required l Similar observations hold for the line connecting Engine Class to Car Class © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

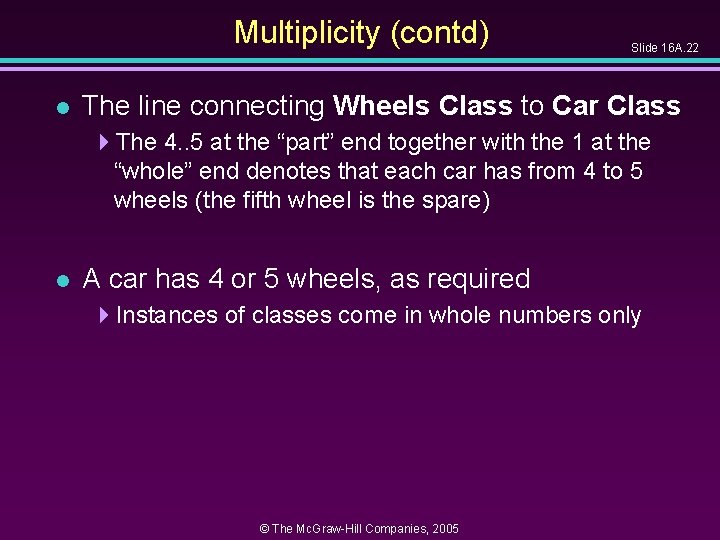

Multiplicity (contd) l Slide 16 A. 22 The line connecting Wheels Class to Car Class 4 The 4. . 5 at the “part” end together with the 1 at the “whole” end denotes that each car has from 4 to 5 wheels (the fifth wheel is the spare) l A car has 4 or 5 wheels, as required 4 Instances of classes come in whole numbers only © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

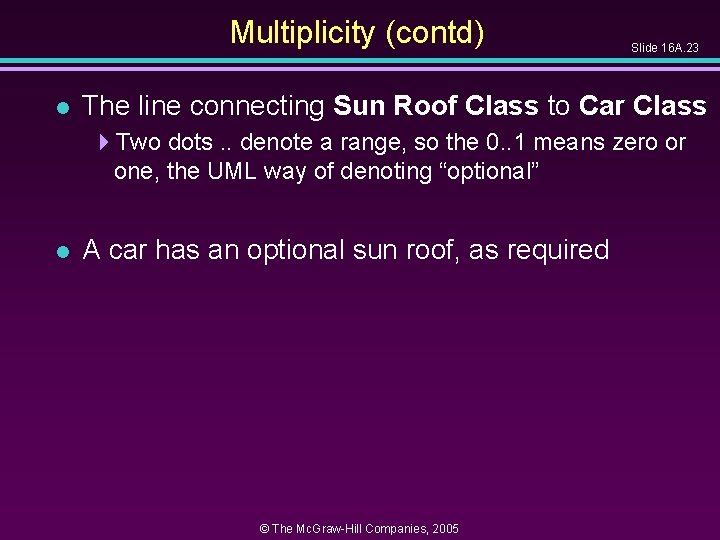

Multiplicity (contd) l Slide 16 A. 23 The line connecting Sun Roof Class to Car Class 4 Two dots. . denote a range, so the 0. . 1 means zero or one, the UML way of denoting “optional” l A car has an optional sun roof, as required © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

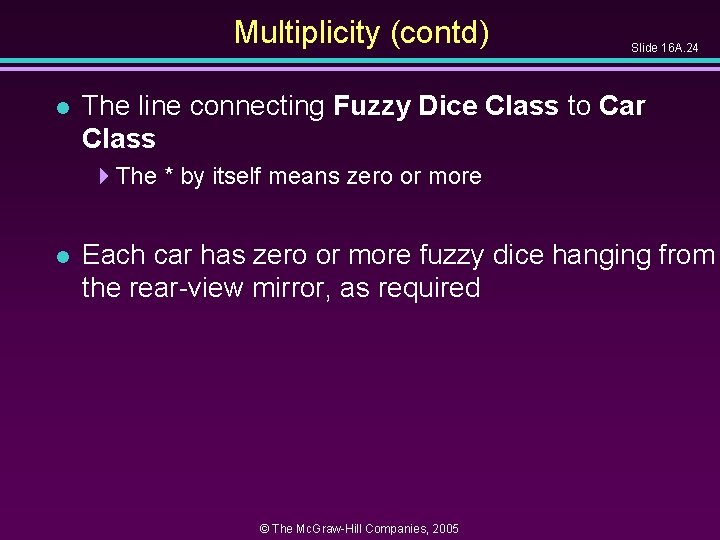

Multiplicity (contd) l Slide 16 A. 24 The line connecting Fuzzy Dice Class to Car Class 4 The * by itself means zero or more l Each car has zero or more fuzzy dice hanging from the rear-view mirror, as required © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Multiplicity (contd) l Slide 16 A. 25 The line connecting Seats Class to Car Class 4 An asterisk in a range denotes “or more, ” so the 2. . * means 2 or more l A car has two or more seats, as required © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Multiplicity (contd) l Slide 16 A. 26 If the exact multiplicity is known, use it 4 Example: The 1 that appears in 8 places l If the range is known, use the range notation 4 Examples: 0. . 1 or 4. . 5 l If the number is unspecified, use the asterisk 4 Example: * l If the range has upper limit unspecified, combine the range notation with the asterisk notation 4 Example: 2. . * © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

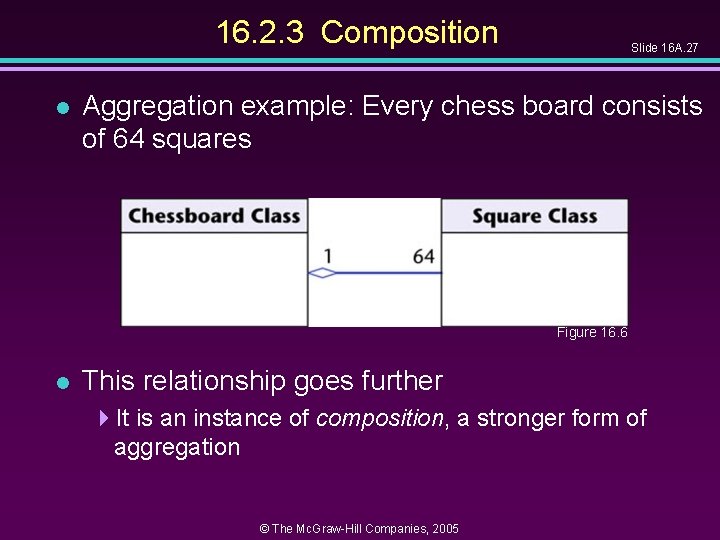

16. 2. 3 Composition l Slide 16 A. 27 Aggregation example: Every chess board consists of 64 squares Figure 16. 6 l This relationship goes further 4 It is an instance of composition, a stronger form of aggregation © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Composition (contd) l Slide 16 A. 28 Association 4 Models the part–whole relationship l Composition 4 Also models the part–whole relationship but, in addition, 4 Every part may belong to only one whole, and 4 If the whole is deleted, so are the parts l Example: A number of different chess boards 4 Each square belongs to only one board 4 If a chess board is thrown away, all 64 squares on that board go as well © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

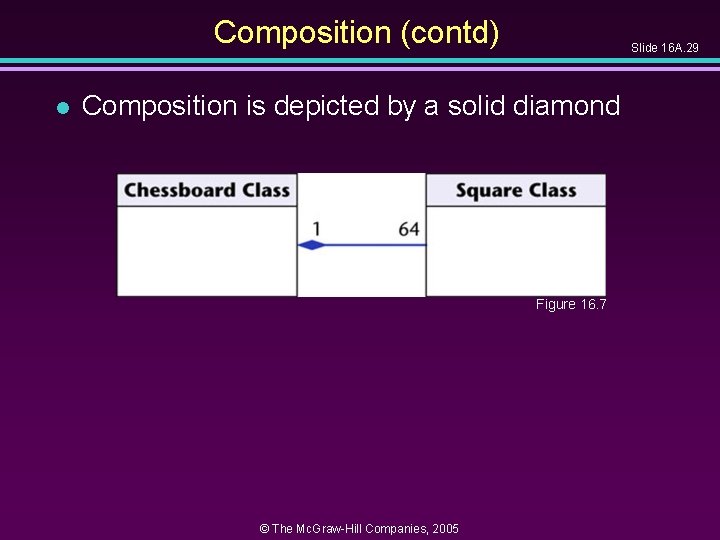

Composition (contd) l Slide 16 A. 29 Composition is depicted by a solid diamond Figure 16. 7 © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

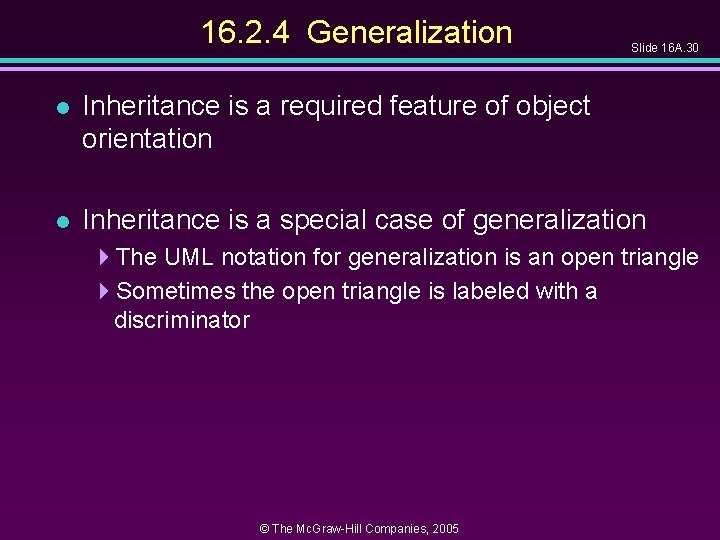

16. 2. 4 Generalization Slide 16 A. 30 l Inheritance is a required feature of object orientation l Inheritance is a special case of generalization 4 The UML notation for generalization is an open triangle 4 Sometimes the open triangle is labeled with a discriminator © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

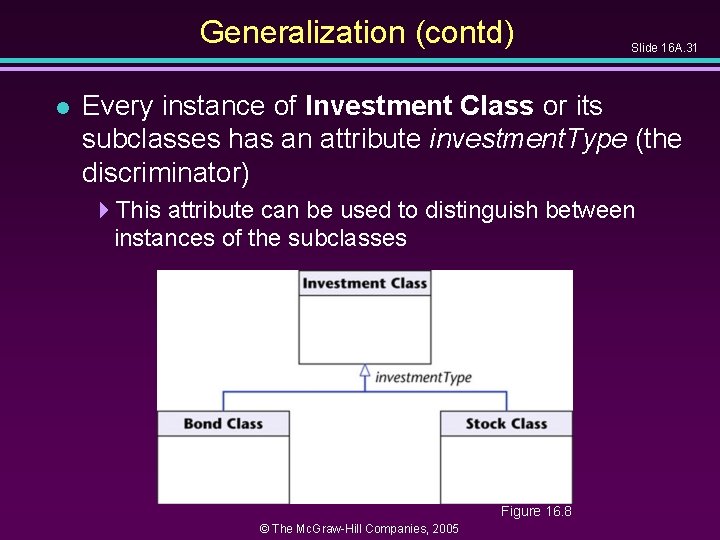

Generalization (contd) l Slide 16 A. 31 Every instance of Investment Class or its subclasses has an attribute investment. Type (the discriminator) 4 This attribute can be used to distinguish between instances of the subclasses Figure 16. 8 © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

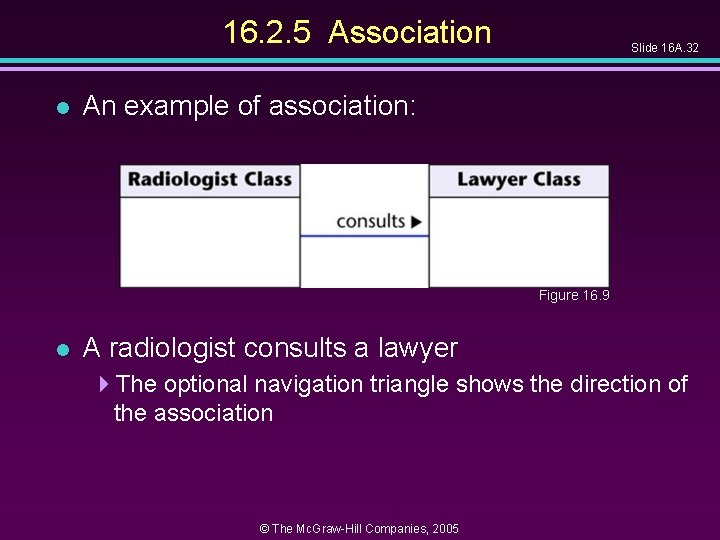

16. 2. 5 Association l Slide 16 A. 32 An example of association: Figure 16. 9 l A radiologist consults a lawyer 4 The optional navigation triangle shows the direction of the association © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

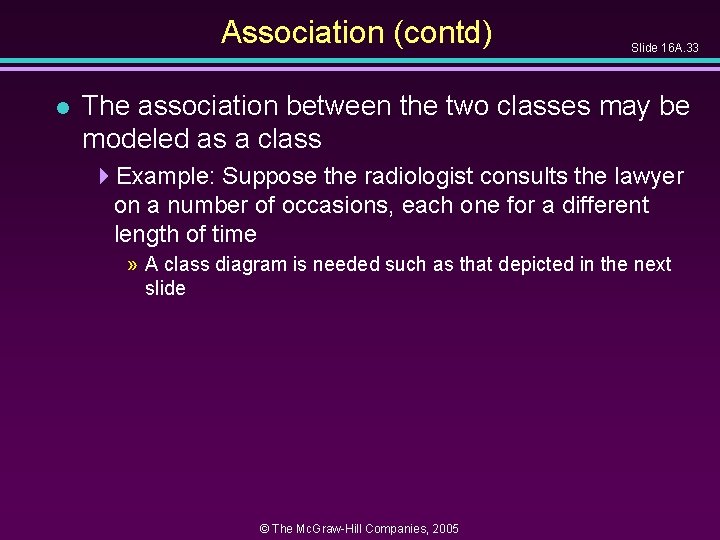

Association (contd) l Slide 16 A. 33 The association between the two classes may be modeled as a class 4 Example: Suppose the radiologist consults the lawyer on a number of occasions, each one for a different length of time » A class diagram is needed such as that depicted in the next slide © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

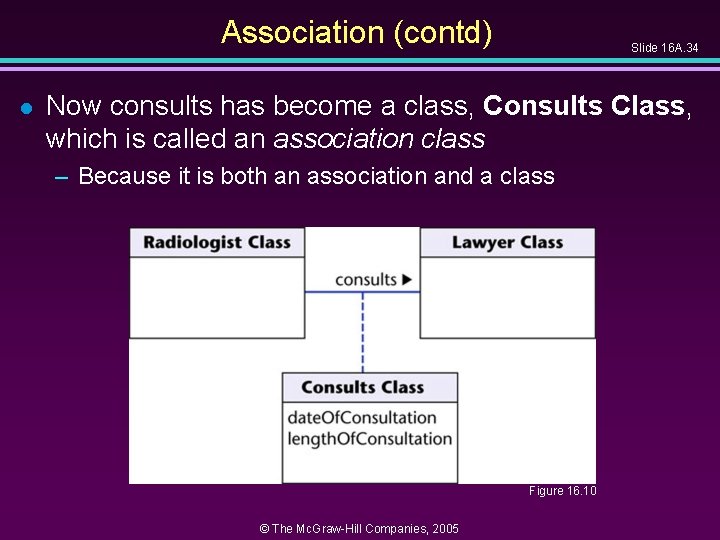

Association (contd) l Slide 16 A. 34 Now consults has become a class, Consults Class, which is called an association class – Because it is both an association and a class Figure 16. 10 © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

16. 3 Notes l Slide 16 A. 35 A comment in a UML diagram is called a note 4 Depicted as a rectangle with the top right-hand corner bent over 4 A dashed line is drawn from the note to the item to which the note refers © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

16. 4 Use-Case Diagrams l Slide 16 A. 36 A use case is a model of the interaction between 4 External users of a software product (actors) and 4 The software product itself » More precisely, an actor is a user playing a specific role l A use-case diagram is a set of use cases © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

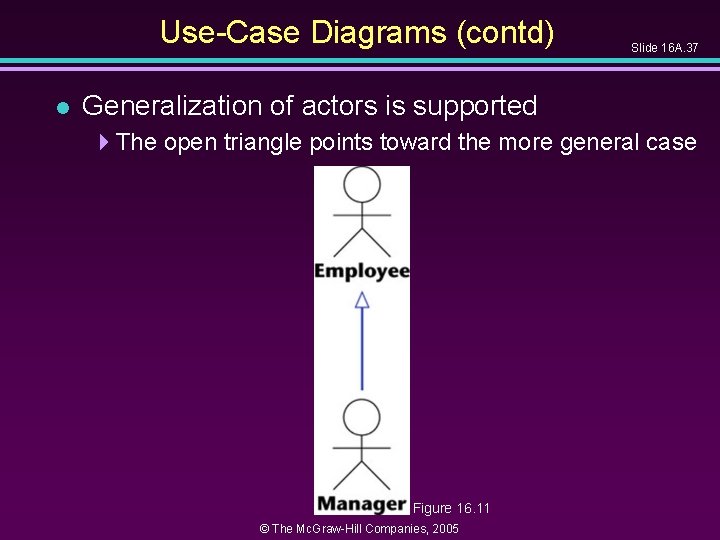

Use-Case Diagrams (contd) l Slide 16 A. 37 Generalization of actors is supported 4 The open triangle points toward the more general case Figure 16. 11 © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

16. 5 Stereotypes Slide 16 A. 38 l A stereotype in UML is a way of extending UML l Stereotypes already encountered include 4 Boundary, control, and entity classes, and 4 The «include» stereotype l The names of stereotypes appear between guillemets 4 Example: «This is my own construct» © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

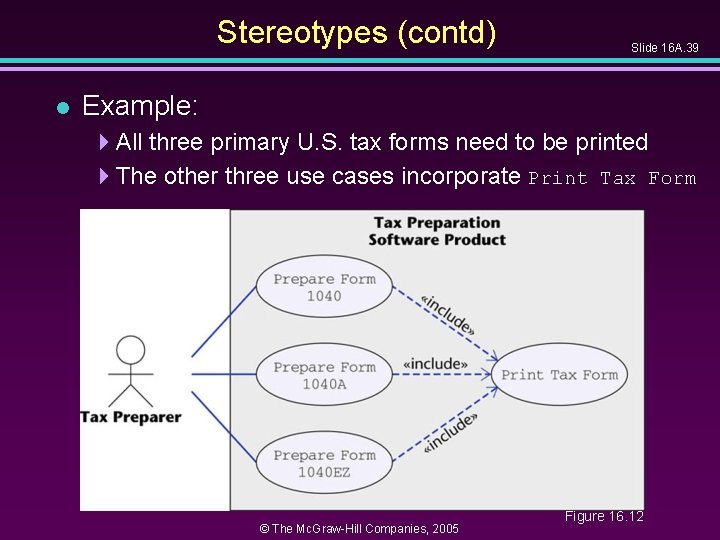

Stereotypes (contd) l Slide 16 A. 39 Example: 4 All three primary U. S. tax forms need to be printed 4 The other three use cases incorporate Print Tax Form © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005 Figure 16. 12

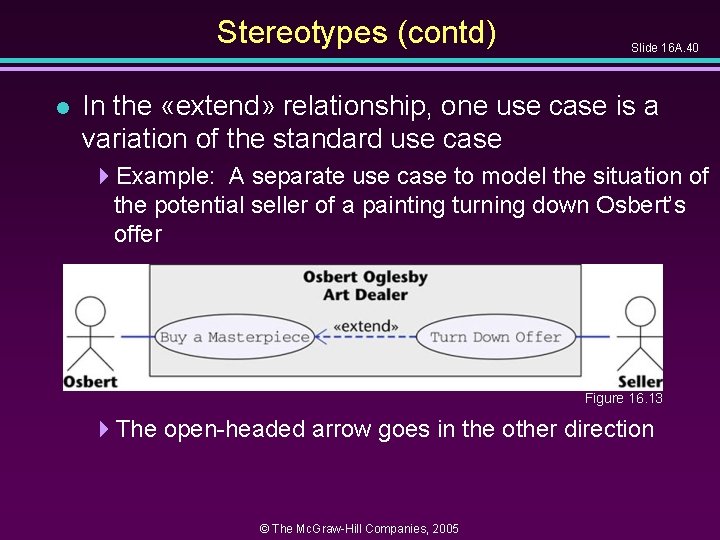

Stereotypes (contd) l Slide 16 A. 40 In the «extend» relationship, one use case is a variation of the standard use case 4 Example: A separate use case to model the situation of the potential seller of a painting turning down Osbert’s offer Figure 16. 13 4 The open-headed arrow goes in the other direction © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

16. 6 Interaction Diagrams Slide 16 A. 41 l Interaction diagrams show objects interact with one another l UML supports two types of interaction diagrams 4 Sequence diagrams 4 Collaboration diagrams © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

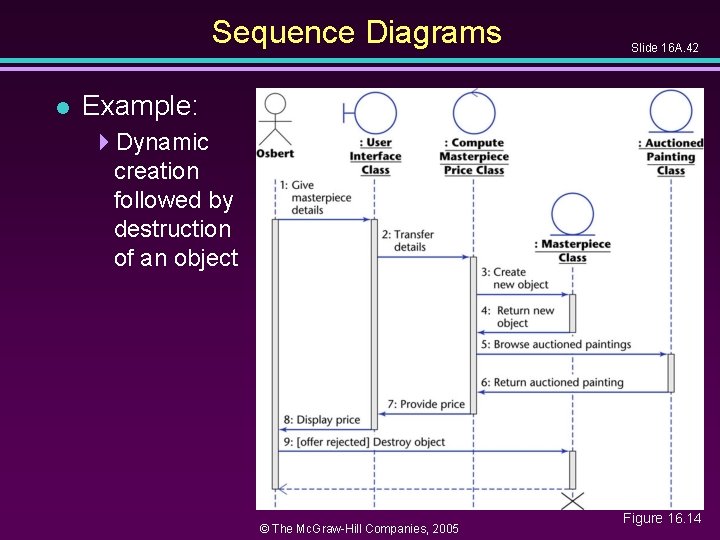

Sequence Diagrams l Slide 16 A. 42 Example: 4 Dynamic creation followed by destruction of an object © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005 Figure 16. 14

Sequence Diagrams (contd) l Slide 16 A. 43 The lifelines in the sequence diagram 4 An active object is denoted by a thin rectangle (activation box) in place of the dashed line l Creation of the : Masterpiece Class object is denoted by the lifeline starting at the point of dynamic creation l Destruction of that object after it receives message » 9: Destroy object is denoted by the heavy X © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Sequence Diagrams (contd) Slide 16 A. 44 l A message is optionally followed by a message sent back to the object that sent the original message l Even if there is a reply, it is not necessary that a specific new message be sent back 4 Instead, a dashed line ending in an open arrow indicates a return from the original message, as opposed to a new message © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Sequence Diagrams (contd) l Slide 16 A. 45 There is a guard on the message » 9: [offer rejected] Destroy object 4 Only if Osbert’s offer is rejected is message 9 sent l A guard (condition) is something that is true or false 4 The message sent only if the guard is true l The purpose of a guard 4 To ensure that the message is sent only if the relevant condition is true © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Sequence Diagrams (contd) Slide 16 A. 46 l Iteration an indeterminate number of times is modeled by an asterisk (Kleene star) l Example: Elevator (see next slide) » *move up one floor 4 The message means: “move up zero or more floors” © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

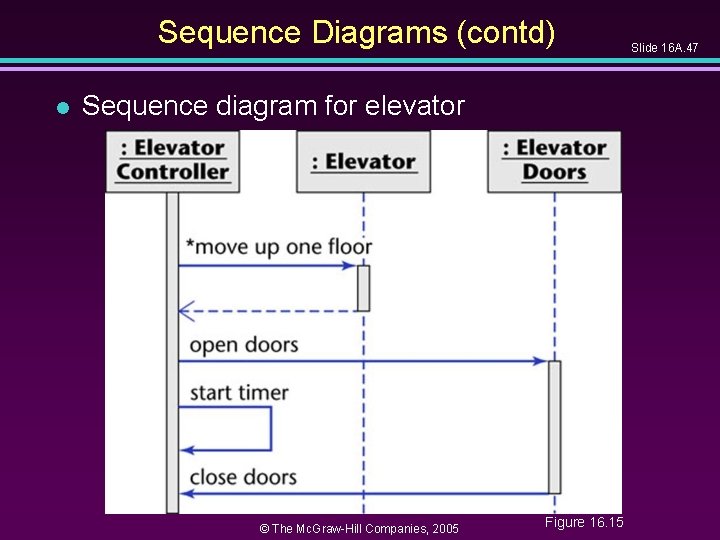

Sequence Diagrams (contd) l Sequence diagram for elevator © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005 Figure 16. 15 Slide 16 A. 47

Sequence Diagrams (contd) l Slide 16 A. 48 An object can send a message to itself 4 A self-call l Example: 4 The elevator has arrived at a floor 4 The elevator doors now open and a timer starts 4 At the end of the timer period the doors close again 4 The elevator controller sends a message to itself to start its timer — this self-call is shown in the previous UML diagram © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Collaboration Diagrams l Slide 16 A. 49 Collaboration diagrams are equivalent to sequence diagrams 4 All the features of sequence diagrams are equally applicable to collaboration diagrams l Use a sequence diagram when the transfer of information is the focus of attention l Use a collaboration diagram when concentrating on the classes © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Slide 16 A. 50 Continued in Unit 16 B © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

- Slides: 50