Simple Modulation pure sinusoid no information AAsinusoidal electrical

- Slides: 13

Simple Modulation pure, sinusoid no information AAsinusoidal electrical signal can be By varying aspects ofcarries a(voltage/current) transmitted the We referinvariant tocertain the pure, invariant sinusoid assinusoid, a “carrier”. except for fact that it and can measured be. The detected, andreceiver, it’s generated atthe abe high frequency. fields variations can detected at associated the presence absence one bit ofmost information. with suchtoor a the signal canrepresents practically beof made to and interpreted assystematic useful information. The We refer variation one or more of its propagate varied through free space and be recovered at are a commonly aspects of transmitted sinusoids properties as “modulation. distance through coupling structures which we call its amplitude, its frequency, or its phase. antennas.

Amplitude Modulation The simplest (and oldest) method of modulation is Ifaccomplished v. I(t) can be recovered theamplitude remote location, amplified, by varyingatthe of the carrier by aand We call this “communication”. used to drive a speaker, then the sounds picked up by the we second signal, call it v. I(t), which contains the information microphone will at beareproduced at the remote location. let v. I(t) wish to recover remote location. As an example, be the voltage generated by a microphone.

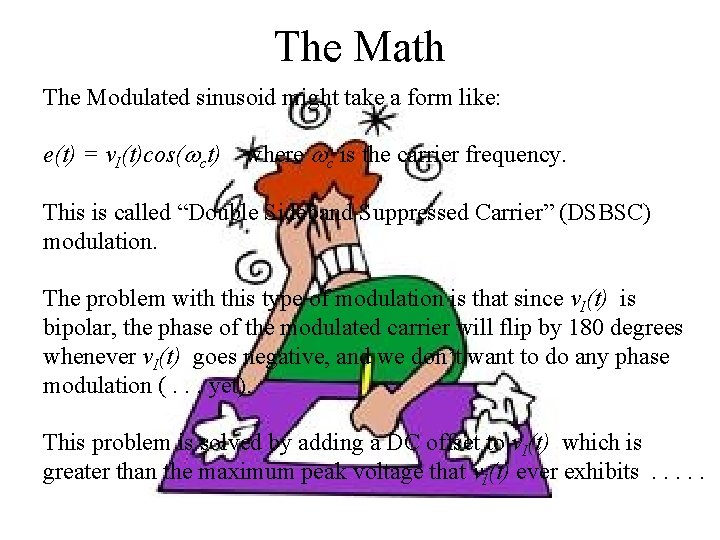

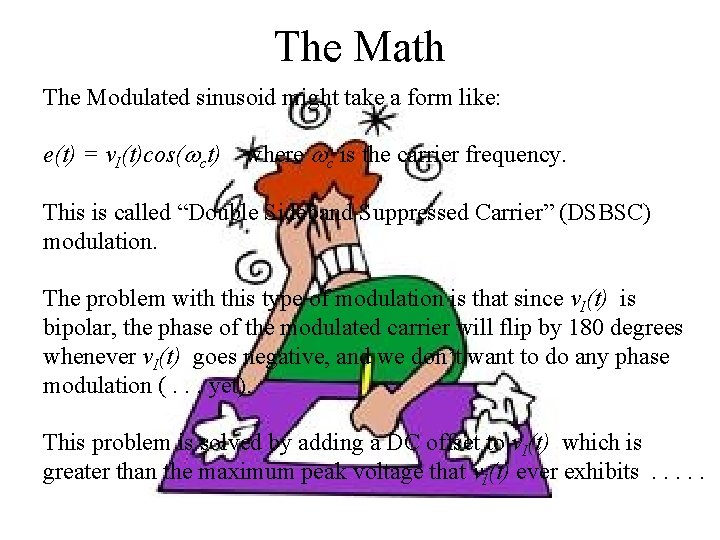

The Math The Modulated sinusoid might take a form like: e(t) = v. I(t)cos(wct) where wc is the carrier frequency. This is called “Double Sideband Suppressed Carrier” (DSBSC) modulation. The problem with this type of modulation is that since v. I(t) is bipolar, the phase of the modulated carrier will flip by 180 degrees whenever v. I(t) goes negative, and we don’t want to do any phase modulation (. . . yet). This problem is solved by adding a DC offset to v. I(t) which is greater than the maximum peak voltage that v. I(t) ever exhibits. . .

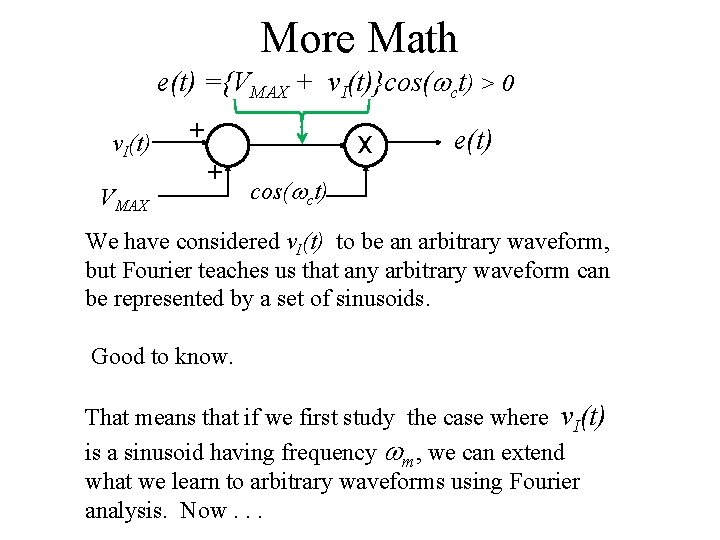

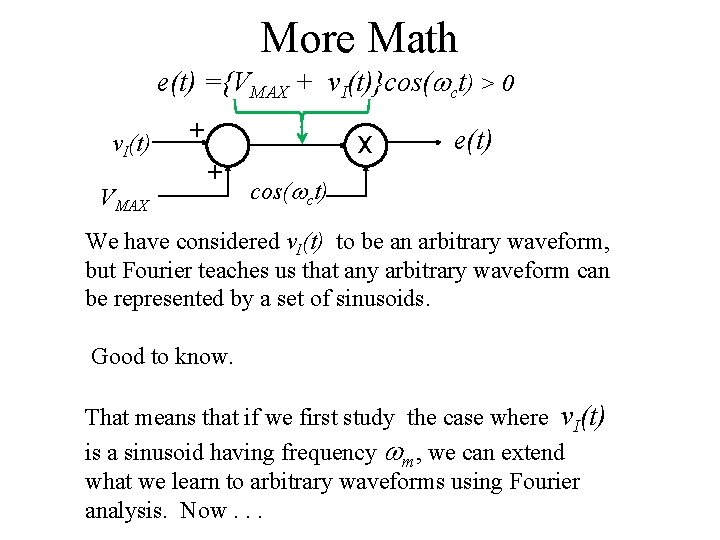

More Math e(t) ={VMAX + v. I(t)}cos(wct) > 0 v. I(t) VMAX + + x e(t) cos(wct) We have considered v. I(t) to be an arbitrary waveform, but Fourier teaches us that any arbitrary waveform can be represented by a set of sinusoids. Good to know. That means that if we first study the case where v. I(t) is a sinusoid having frequency wm, we can extend what we learn to arbitrary waveforms using Fourier analysis. Now. . .

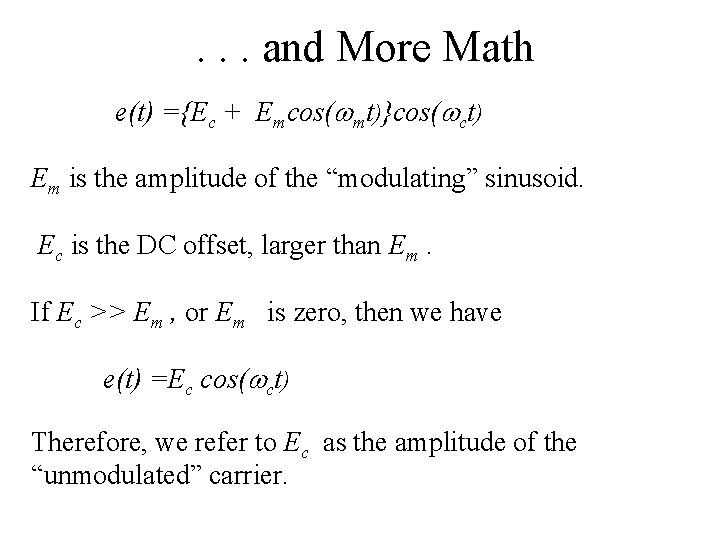

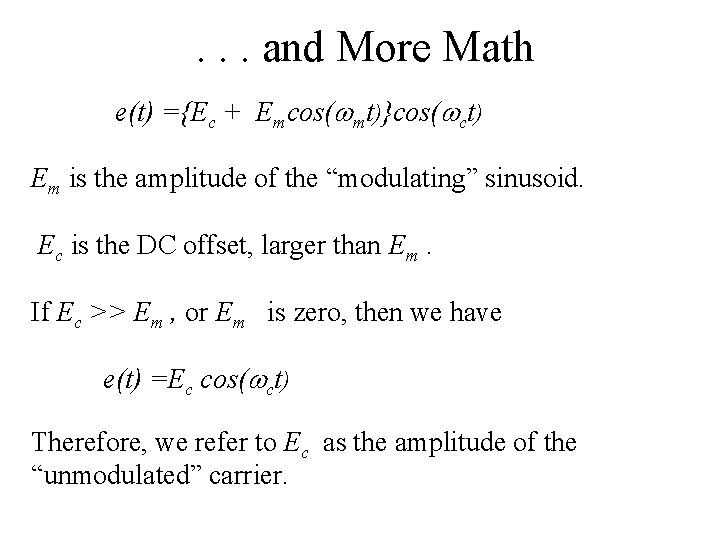

. . . and More Math e(t) ={Ec + Emcos(wmt)}cos(wct) Em is the amplitude of the “modulating” sinusoid. Ec is the DC offset, larger than Em. If Ec >> Em , or Em is zero, then we have e(t) =Ec cos(wct) Therefore, we refer to Ec as the amplitude of the “unmodulated” carrier.

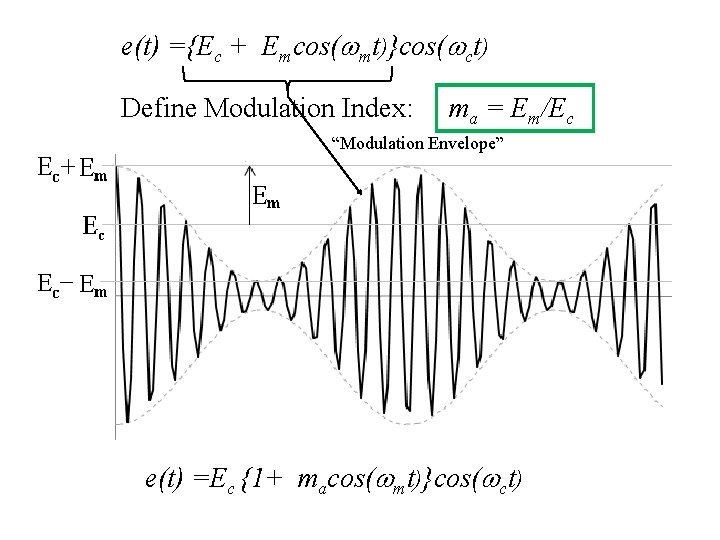

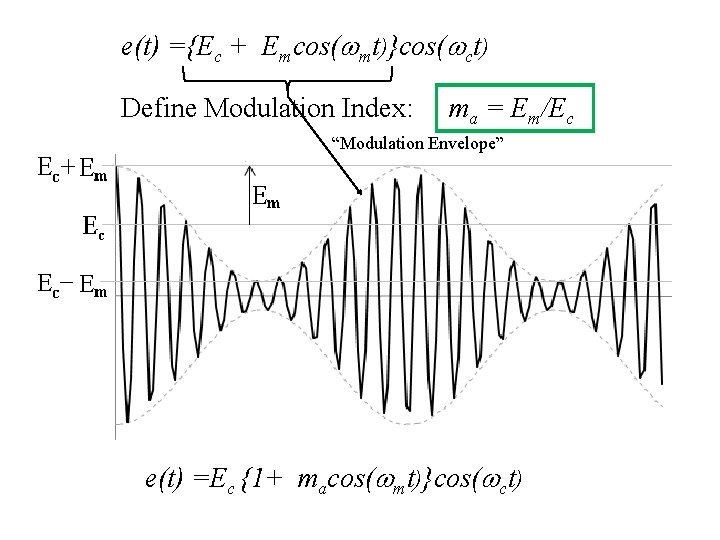

e(t) ={Ec + Emcos(wmt)}cos(wct) Define Modulation Index: ma = Em/Ec “Modulation Envelope” e(t) =Ec {1+ macos(wmt)}cos(wct)

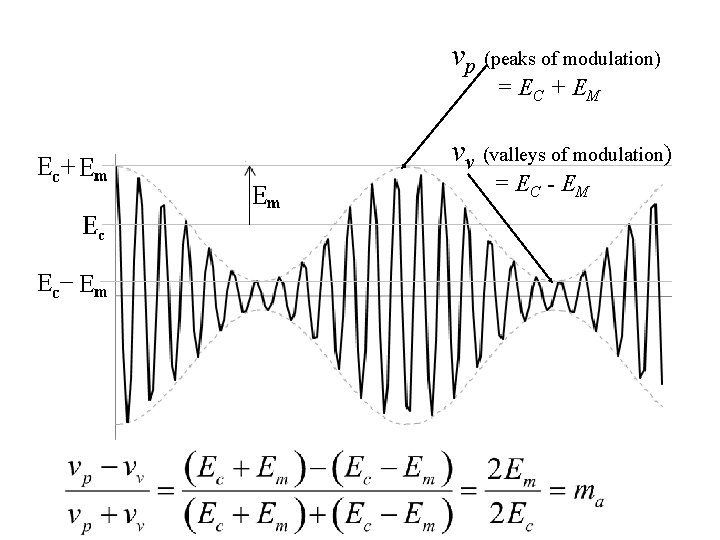

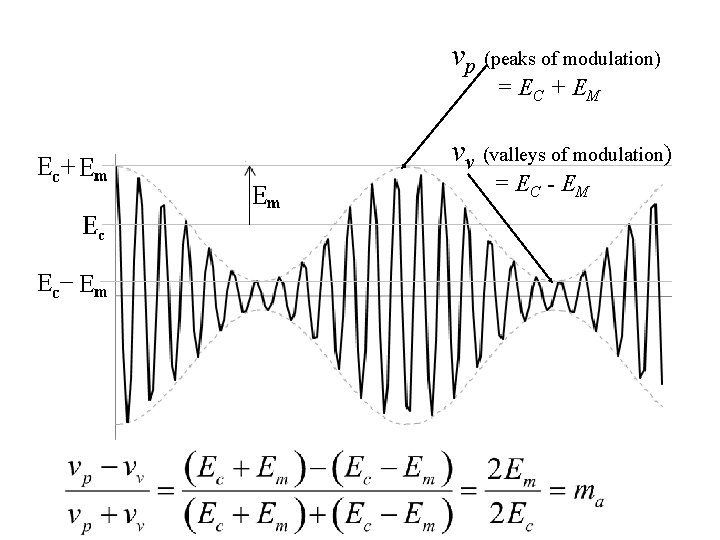

vp (peaks of modulation) = EC + EM vv (valleys of modulation) = E C - EM

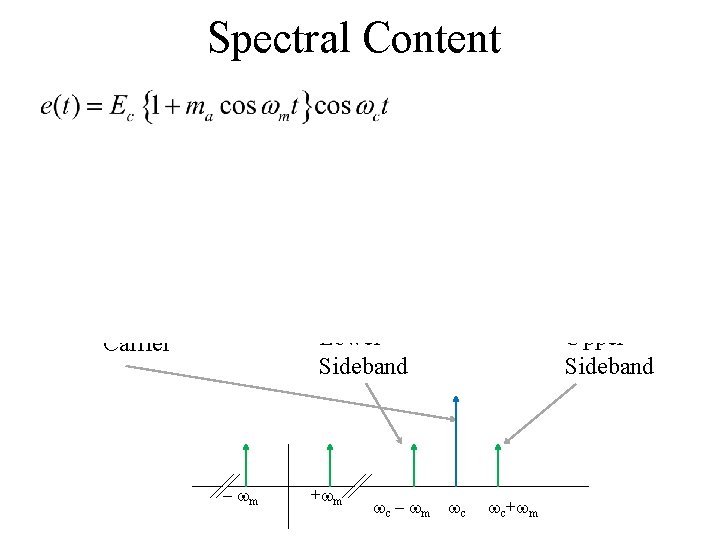

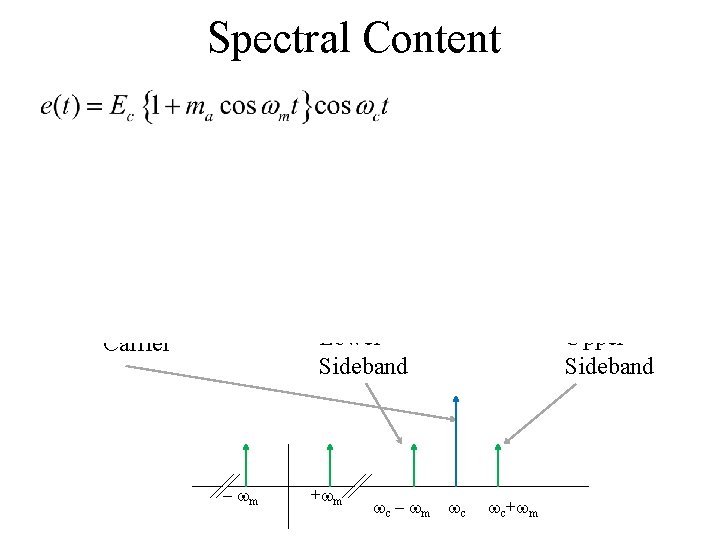

Spectral Content Lower Sideband Carrier – wm +wm wc – wm Upper Sideband wc wc+wm

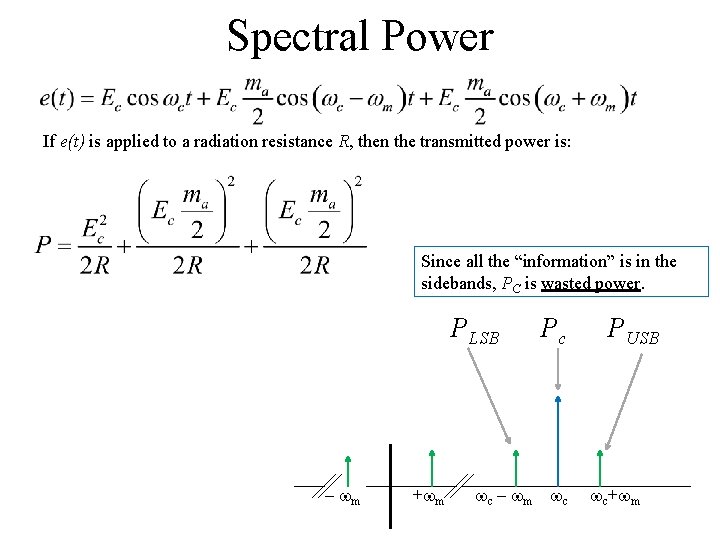

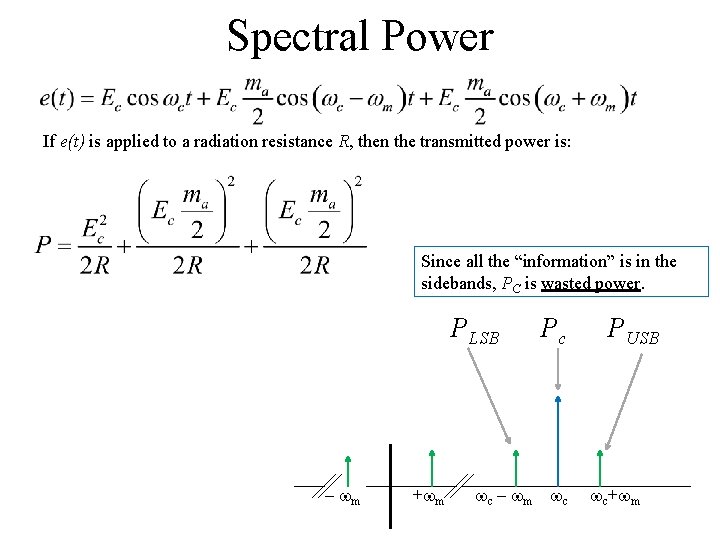

Spectral Power If e(t) is applied to a radiation resistance R, then the transmitted power is: Since all the “information” is in the sidebands, PC is wasted power. PLSB – wm +wm wc – wm Pc wc PUSB wc+wm

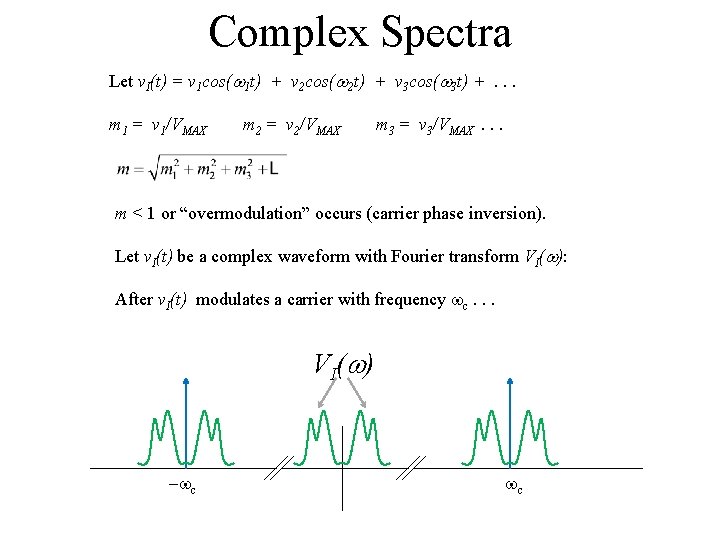

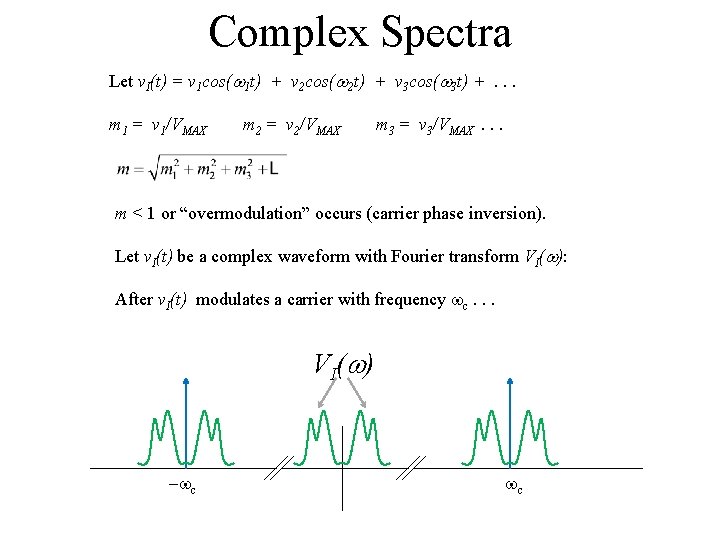

Complex Spectra Let v. I(t) = v 1 cos(w 1 t) + v 2 cos(w 2 t) + v 3 cos(w 3 t) +. . . m 1 = v 1/VMAX m 2 = v 2/VMAX m 3 = v 3/VMAX. . . m < 1 or “overmodulation” occurs (carrier phase inversion). Let v. I(t) be a complex waveform with Fourier transform VI(w): After v. I(t) modulates a carrier with frequency wc. . . V I( w ) -wc wc

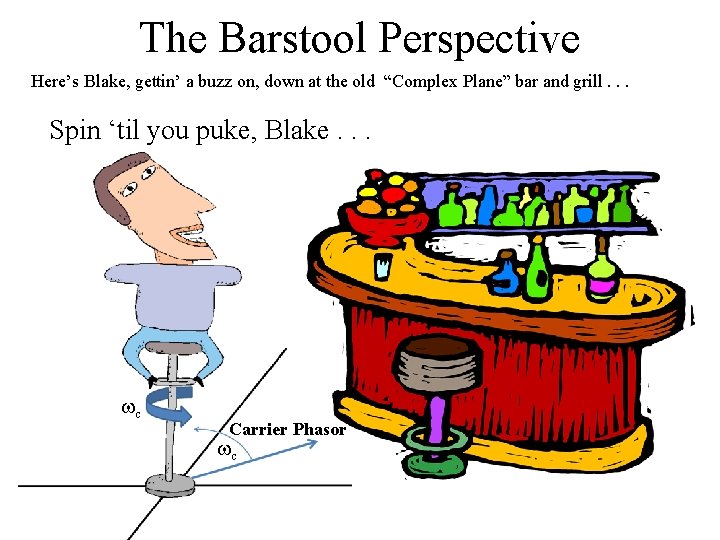

The Barstool Perspective Here’s Blake, gettin’ a buzz on, down at the old “Complex Plane” bar and grill. . . Spin ‘til you puke, Blake. . . wc Carrier Phasor wc

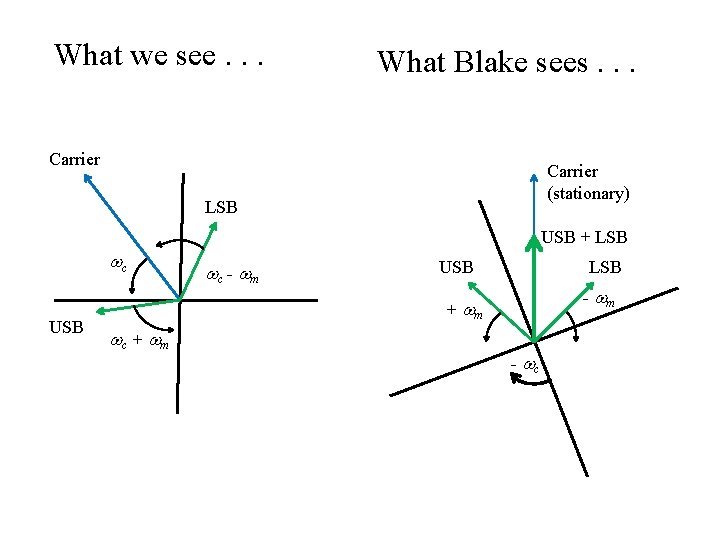

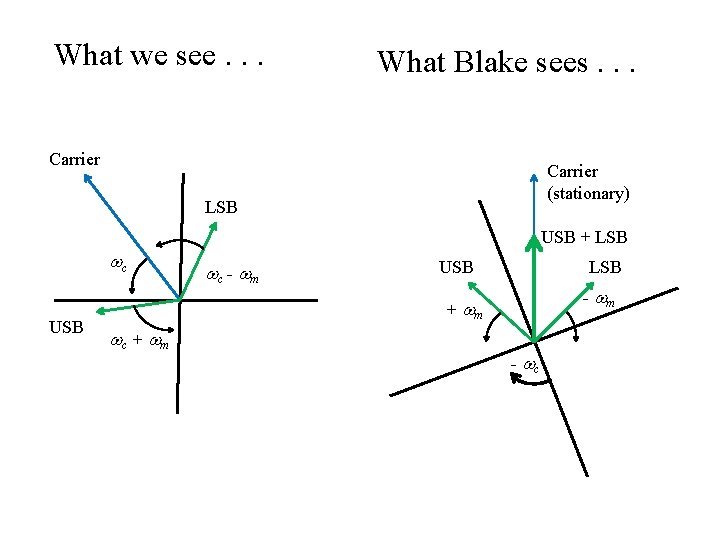

What we see. . . What Blake sees. . . Carrier (stationary) LSB USB + LSB wc USB wc - wm USB LSB - wm + wm wc + wm - wc

T G I FM