Shunt Malfunction Objectives Explain normal CSF circulation and

Shunt Malfunction

Objectives • Explain normal CSF circulation and reabsorption • Describe indications for shunts and the different varieties of shunts • Understand the signs and symptoms of shunt malfunction

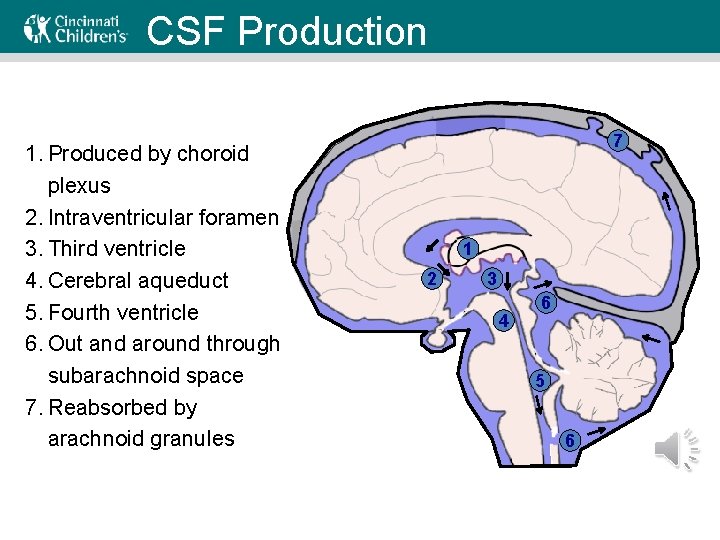

CSF Production CSF Circulation 1. Produced by choroid plexus 2. Intraventricular foramen 3. Third ventricle 4. Cerebral aqueduct 5. Fourth ventricle 6. Out and around through subarachnoid space 7. Reabsorbed by arachnoid granules 7 1 2 3 4 6 5 6

Shunt indications • Blockage in CSF circulation or failure to reabsorb – Aqueductal stenosis – Hemmorhage – Trauma – Infection – Tumor • CSF needs to be diverted to avoid increased intracranial pressure

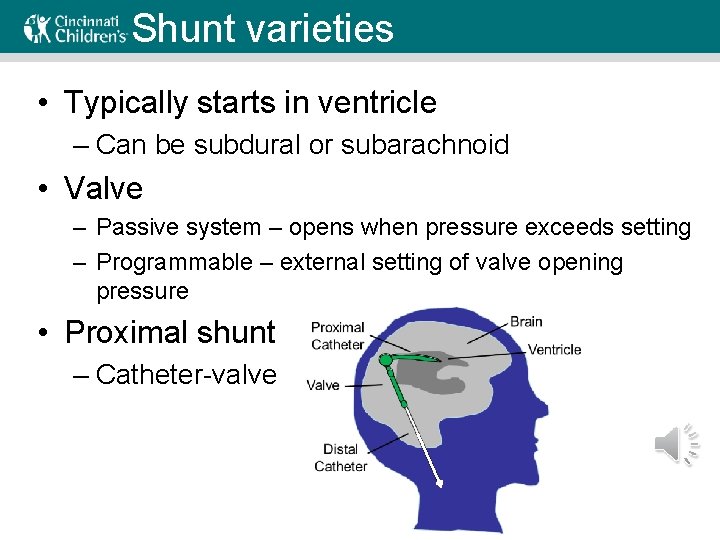

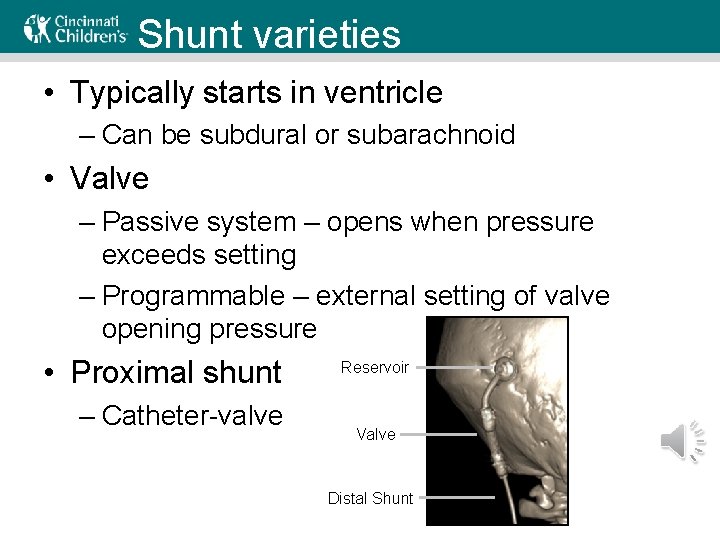

Shunt varieties • Typically starts in ventricle – Can be subdural or subarachnoid • Valve – Passive system – opens when pressure exceeds setting – Programmable – external setting of valve opening pressure • Proximal shunt – Catheter-valve

Shunt varieties • Typically starts in ventricle – Can be subdural or subarachnoid • Valve – Passive system – opens when pressure exceeds setting – Programmable – external setting of valve opening pressure • Proximal shunt – Catheter-valve Reservoir Valve Distal Shunt

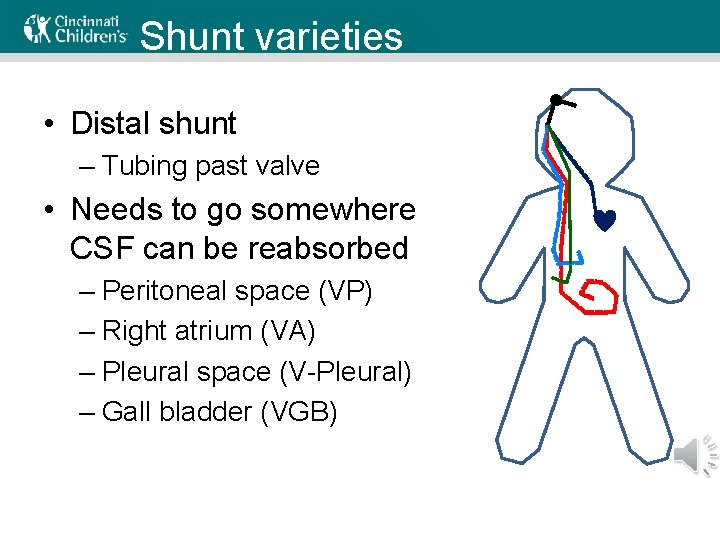

Shunt varieties • Distal shunt – Tubing past valve • Needs to go somewhere CSF can be reabsorbed – Peritoneal space (VP) – Right atrium (VA) – Pleural space (V-Pleural) – Gall bladder (VGB)

Shunt varieties • How do you decide – Peritoneum preferred – Poor distal absorption (e. g. , NEC damages peritoneum, abdominal adhesions) – Patient size (can a pleural effusion be tolerated? ) – Thrombosis risk (risk of VA shunt failure) – All other routes exhausted (gall bladder is last choice) • Shunt malfunction may differ by distal site

Risk factors – Shunt Malfunction • Recent shunt placement or revision – Highest suspicion if within 6 months – 30 -40% shunts fail in first year – Additional 15% fail in the second year – Most infections present within 3 -6 months • Sick visit in infant with shunt – More likely to be the shunt than older patients

Etiology • Infection – Often normal skin flora – Positive CSF culture confirms • Obstruction – Proximal occlusion (debris in ventricles) – Distal occlusion (pseudocyst, clot) • Disconnection – Migration, fracture • Over-shunting

Diagnosis • Most reliable may be history – What did previous malfunction look like? – When was last shunt revision? – Sick contacts or other symptoms that point to another cause • No single test to confirm – Every child’s malfunction looks different

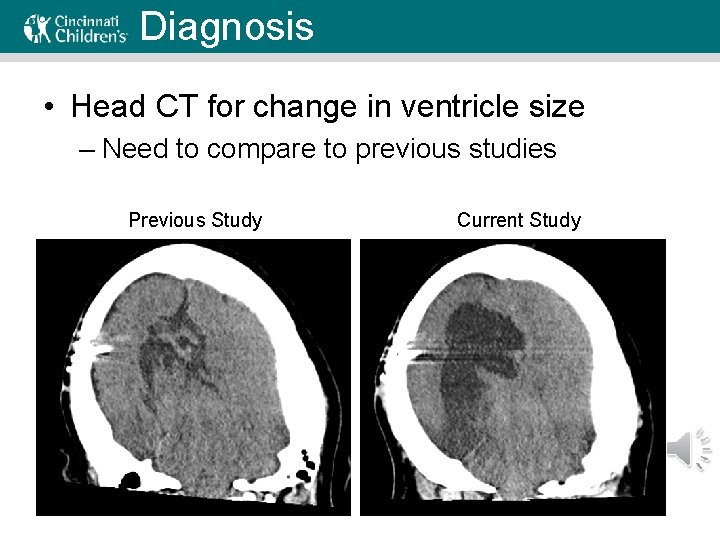

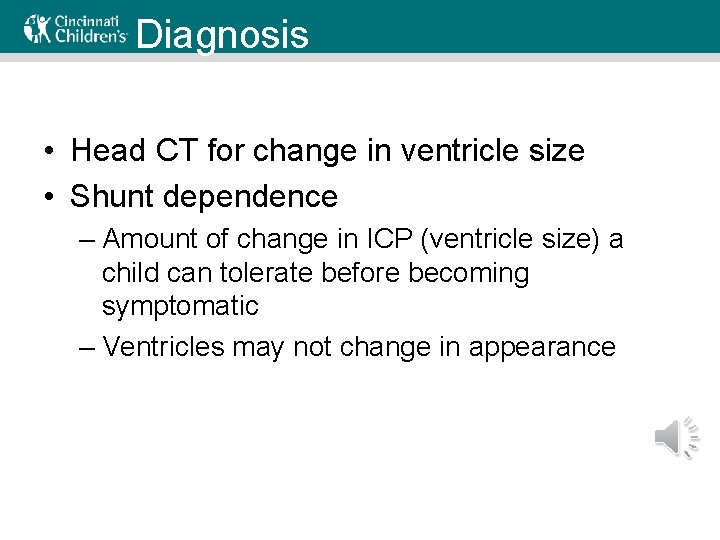

Diagnosis • Head CT for change in ventricle size – Need to compare to previous studies Previous Study Current Study

Diagnosis • Head CT for change in ventricle size • Shunt dependence – Amount of change in ICP (ventricle size) a child can tolerate before becoming symptomatic – Ventricles may not change in appearance

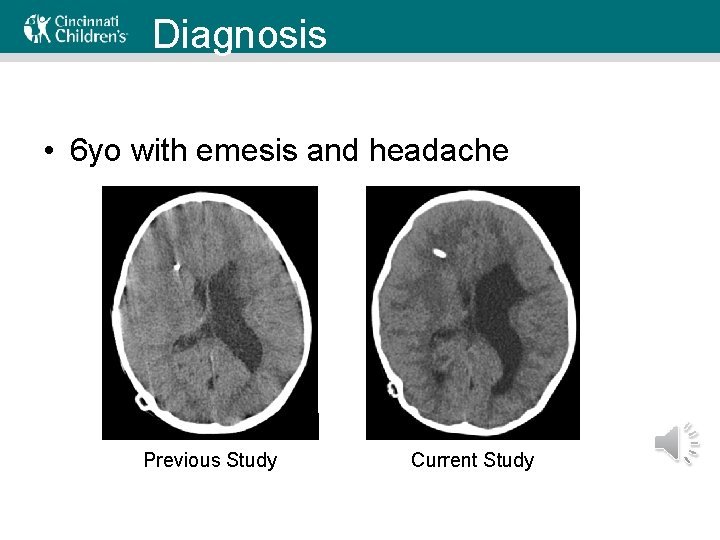

Diagnosis • 6 yo with emesis and headache Previous Study Current Study

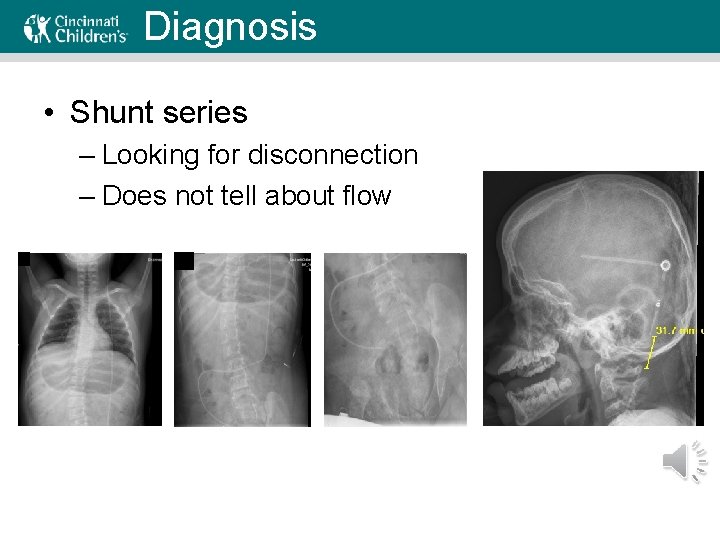

Diagnosis • Shunt series – Looking for disconnection – Does not tell about flow

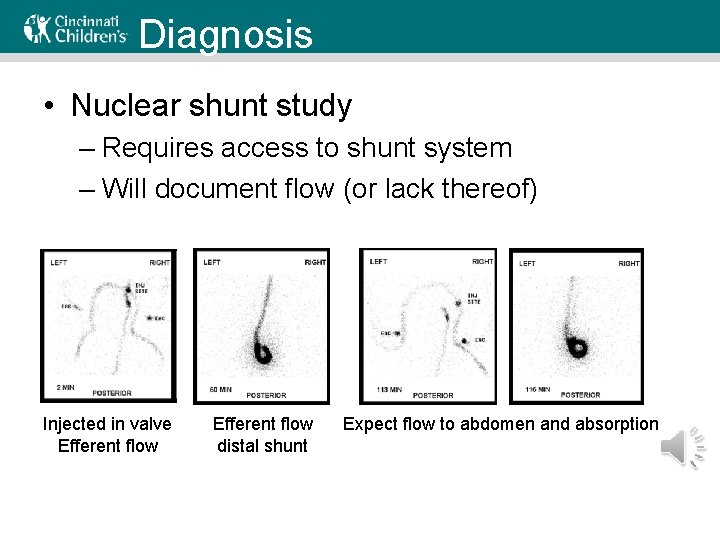

Diagnosis • Nuclear shunt study – Requires access to shunt system – Will document flow (or lack thereof) Injected in valve Efferent flow distal shunt Expect flow to abdomen and absorption

Diagnosis • Pumping valve – Empty reservoir to pull CSF from ventricle – Not reliable – Should NEVER be attempted by anyone other than Neurosurgery

Diagnosis • Echocardiogram – VA shunt looking for clot • Abdominal ultrasound – VP shunt looking for pseudocyst – Free peritoneal fluid (CSF) is normal finding • Shunt tap – CSF sample looking for infection – Controversial – may introduce bacteria to system

Diagnosis • History – particularly in ‘fresh’ shunts – Nausea/Vomiting – Irritability – Somnolence, ‘not his/herself’, decreased LOC – Symptoms of increased ICP – Headache (postural, awakening, early morning) – Increased seizure frequency – Loss of developmental milestones/school difficulty – Dyspnea/pleuritic pain (V-pleural) – What has past malfunction looked like?

Diagnosis • Physical exam – Bulging fontanelle – Exposed shunt (infected by default) – Fluid collection(s) along shunt path – Papilledema, Optic nerve atrophy – Peritoneal signs, abdominal tenderness – Wound erythema, drainage (pus, CSF)

Diagnosis • Alternatives – Gastroenteritis – diarrhea helpful – Other viral illness – consider PCR – Headache – migraine, stress, other – Pancreatitis – elevated lipase • Valve reprogramming – Change pressure setting – Watch for change in symptoms or CT

Diagnosis • Intra-operative evaluation – Only definitive way to diagnose malfunction – Proximal obstruction – no flow to valve – Distal obstruction – no flow through catheter – Infection – may see frank pus or inflammatory tissue

Treatment • Almost always involves OR – At times emergent • Procedure depends on findings – Infection? Remove and insert EVD – Malfunction? Replacement of portion • Final decision is Neurosurgeon’s – Any revision increases risk of infection or other malfunction – The surgeon has the most experience and sees things first hand

Post-Revision Management • Time to symptom resolution – Influenced by patient’s shunt dependence – May be immediate or more gradual – Remember post-anesthesia could affect mental status, emesis, etc. – Expect to progressively improve • Post-op head imaging – May involve CT 6 -12 hr post-op – Evaluate for complication (e. g. , hemorrhage)

Post-Revision Management • Keep in mind possible complications based on distal catheter location – Peritoneal – ileus, bowel perforation, hernia, constipation – Pleural – symptomatic pleural effusion, pneumothorax – Atrial – arrhythmia, thrombosis (including PE), pulmonary hypertension, endocarditis

Key Points • Shunt malfunction is difficult to diagnose – Ultimately, surgeon makes the call • Red flags – Acute symptoms of increased ICP – Revision within 6 mo – Similar symptoms as last malfunction • Pediatricians can help with alternative diagnoses – Help rule-in or out medical conditions

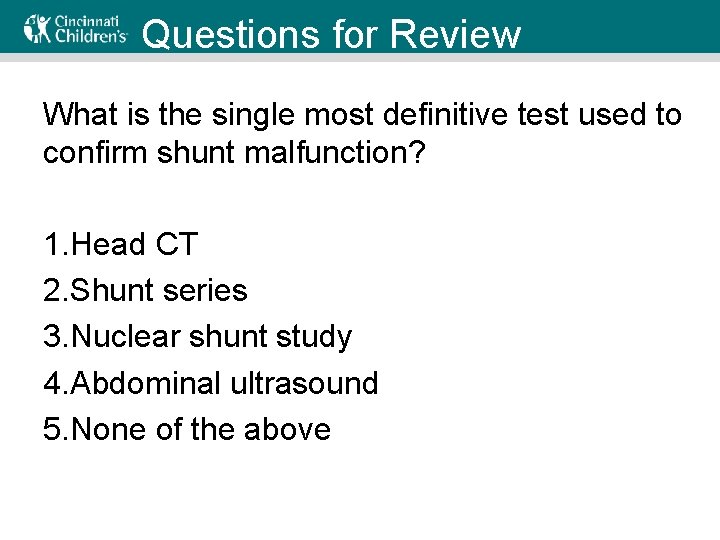

Questions for Review What is the single most definitive test used to confirm shunt malfunction? 1. Head CT 2. Shunt series 3. Nuclear shunt study 4. Abdominal ultrasound 5. None of the above

Questions for Review What is the single most definitive test used to confirm shunt malfunction? 1. Head CT 2. Shunt series 3. Nuclear shunt study 4. Abdominal ultrasound 5. None of the above

Questions for Review Which of the following is NOT a determinant of distal shunt placement? 1. Patient size 2. History of abdominal pathology 3. History of thrombosis 4. Patient sex 5. Surgeon preference

Questions for Review Which of the following is NOT a determinant of distal shunt placement? 1. Patient size 2. History of abdominal pathology 3. History of thrombosis 4. Patient sex 5. Surgeon preference

Question for Discussion A 12 yo patient with a VP shunt presents with vomiting. What additional historical information should you obtain to aid in diagnosing a possible shunt malfunction?

References • Garton HJL & Piatt JH. Hydrocephalus. Pediatr Clin N Am (2004) 51: 305 -25. • Browd SR et al. Failure of cerebral spinal fluid shunts: part 1: obstruction and mechanical failure. Pediatr Nurol (2006) 34: 83 -92. • Browd SR et al. Failure of cerebral spinal fluid shunts: part 2: overdrainage, loculation, and abdominal complications. Pediatr Nurol (2006) 34: 171 -6. • Stein SC & Guo W. Have we made progress in preventing shunt failure? A critical analysis. J Neurosurg Pediatr (2008) 1: 40 -7. • Simon TD, et al. Risk factors for first cerebrospinal fluid shunt infection: findings from a multi-center prospective cohort study. J Pediatr (2014) 164: 1462 -8. • Kestle JR, et al. Management of shunt infections: a multicenter pilot study. J Neurosurg (3 Suppl Pediatrics) (2006) 105: 177 -81. • George R, et al. Long-term analysis of cerebrospinal fluid shunt infections a 25 year experience. J Neurosurg (1979) 51: 804 -11.

- Slides: 32