Sharing features for multiclass object detection Antonio Torralba

Sharing features for multi-class object detection Antonio Torralba, Kevin Murphy and Bill Freeman MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) Sept. 1, 2004

The lead author: Antonio Torralba

Goal • We want a machine to be able to identify thousands of different objects as it looks around the world.

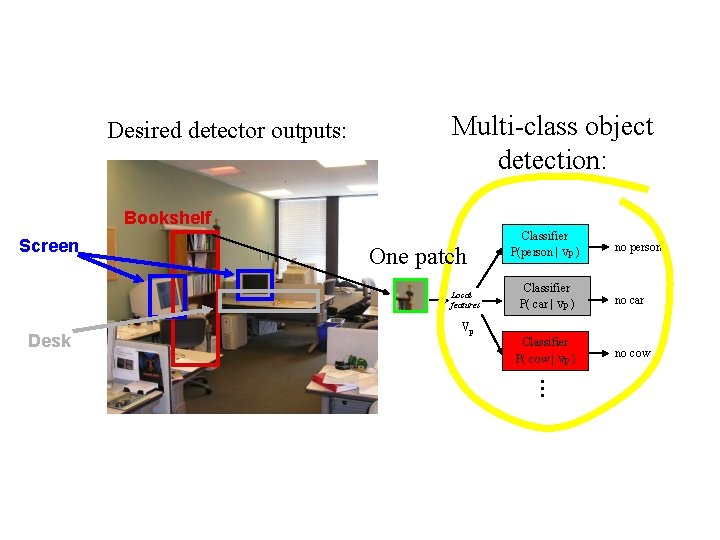

Desired detector outputs: Multi-class object detection: Bookshelf Screen One patch Local features Desk Vp Classifier P(person | vp ) no person Classifier P( car | vp ) no car Classifier P( cow | vp ) no cow …

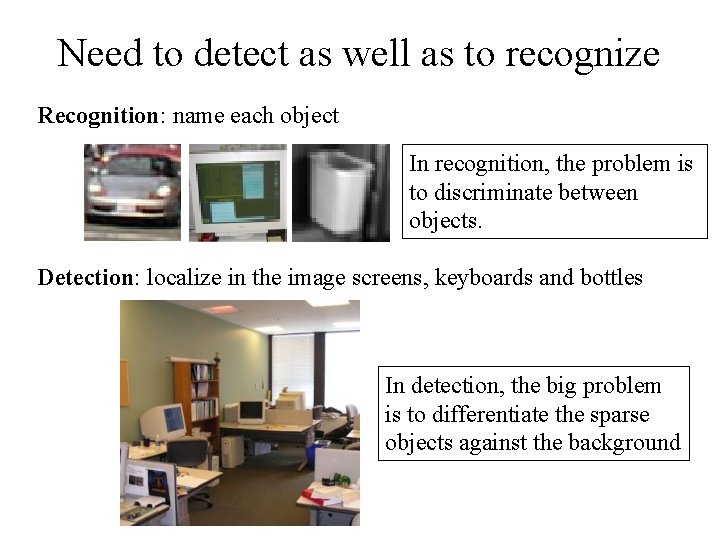

Need to detect as well as to recognize Recognition: name each object In recognition, the problem is to discriminate between objects. Detection: localize in the image screens, keyboards and bottles In detection, the big problem is to differentiate the sparse objects against the background

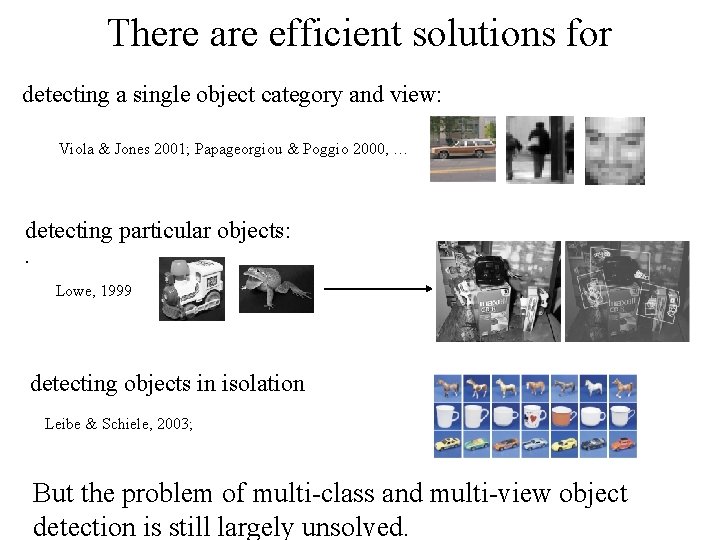

There are efficient solutions for detecting a single object category and view: Viola & Jones 2001; Papageorgiou & Poggio 2000, … detecting particular objects: . Lowe, 1999 detecting objects in isolation Leibe & Schiele, 2003; But the problem of multi-class and multi-view object detection is still largely unsolved.

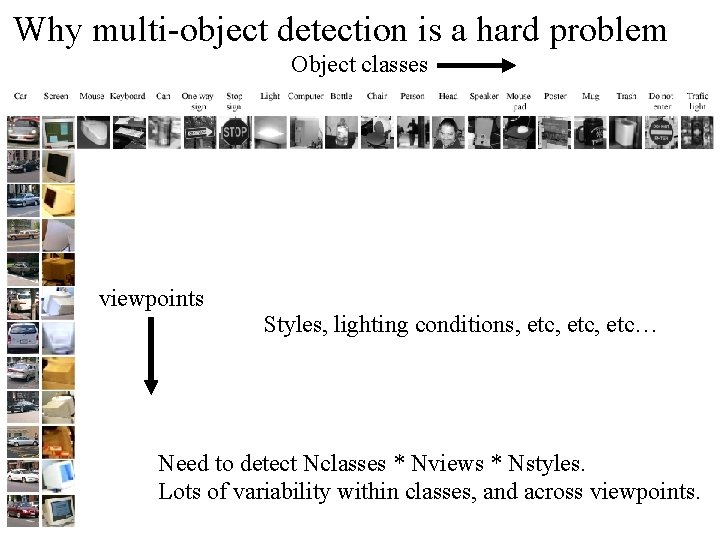

Why multi-object detection is a hard problem Object classes viewpoints Styles, lighting conditions, etc, etc… Need to detect Nclasses * Nviews * Nstyles. Lots of variability within classes, and across viewpoints.

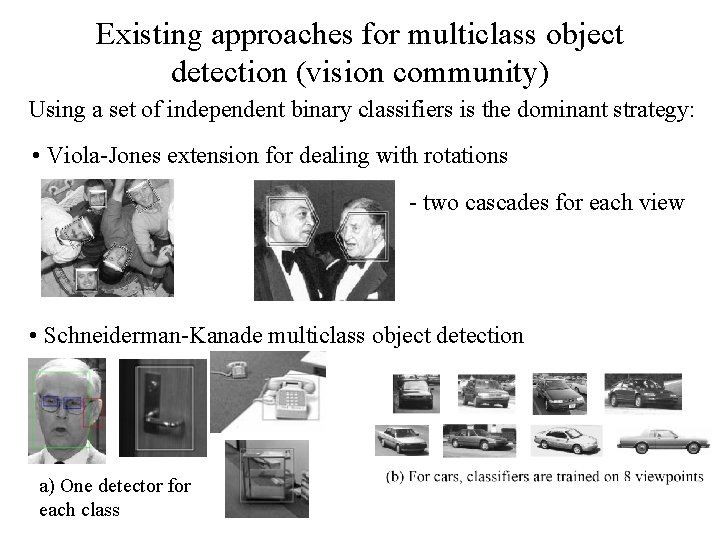

Existing approaches for multiclass object detection (vision community) Using a set of independent binary classifiers is the dominant strategy: • Viola-Jones extension for dealing with rotations - two cascades for each view • Schneiderman-Kanade multiclass object detection a) One detector for each class

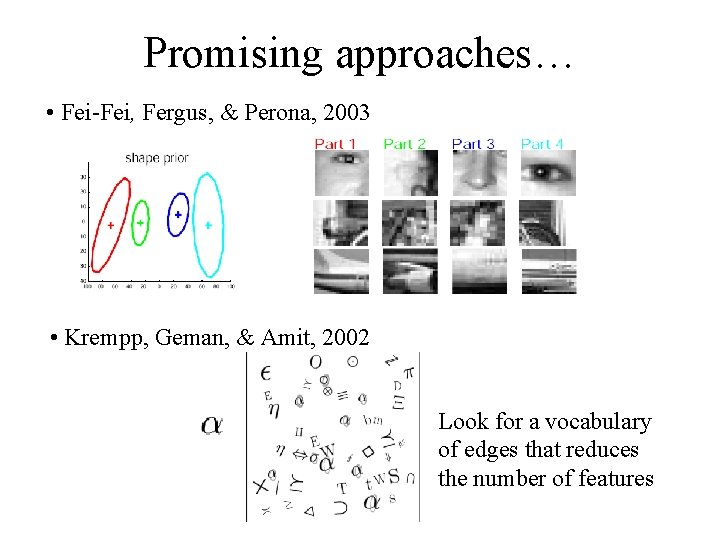

Promising approaches… • Fei-Fei, Fergus, & Perona, 2003 • Krempp, Geman, & Amit, 2002 Look for a vocabulary of edges that reduces the number of features

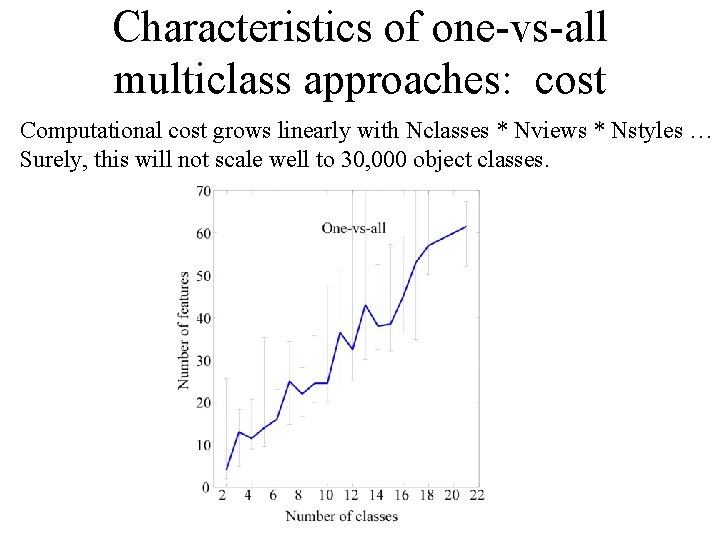

Characteristics of one-vs-all multiclass approaches: cost Computational cost grows linearly with Nclasses * Nviews * Nstyles … Surely, this will not scale well to 30, 000 object classes.

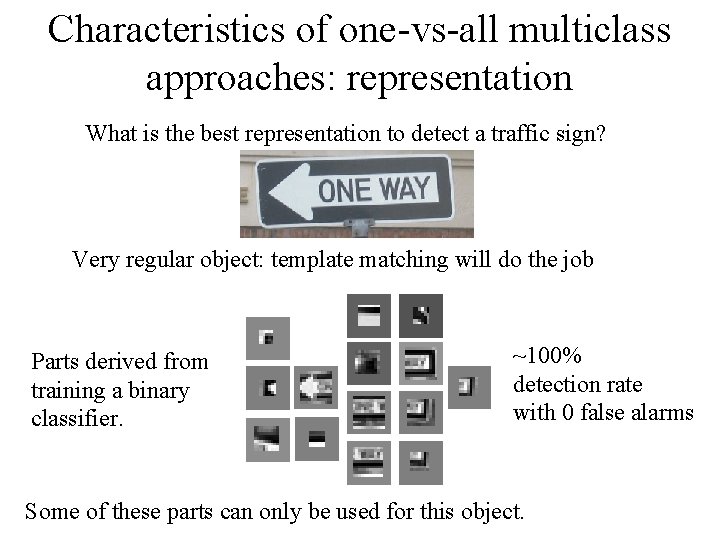

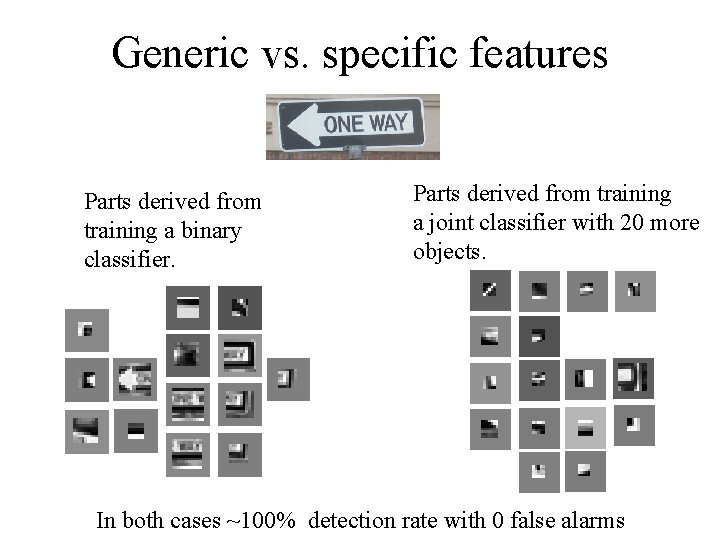

Characteristics of one-vs-all multiclass approaches: representation What is the best representation to detect a traffic sign? Very regular object: template matching will do the job Parts derived from training a binary classifier. ~100% detection rate with 0 false alarms Some of these parts can only be used for this object.

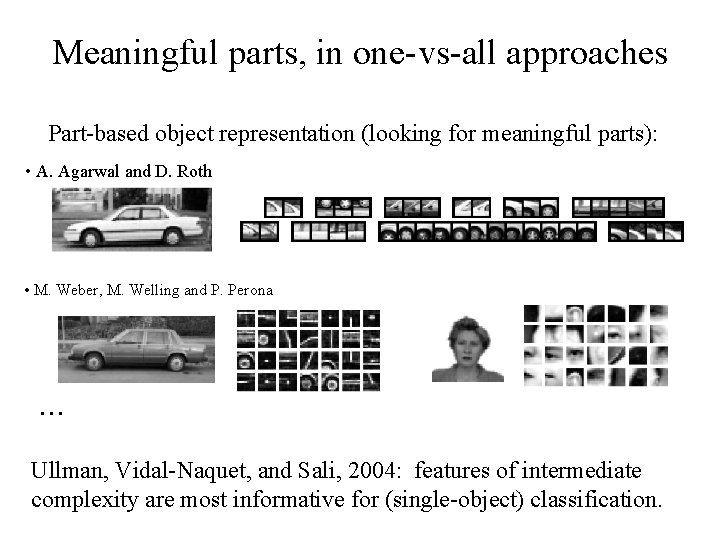

Meaningful parts, in one-vs-all approaches Part-based object representation (looking for meaningful parts): • A. Agarwal and D. Roth • M. Weber, M. Welling and P. Perona … Ullman, Vidal-Naquet, and Sali, 2004: features of intermediate complexity are most informative for (single-object) classification.

Multi-classifiers (machine learning community) • Error correcting output codes (Dietterich & Bakiri, 1995; …) But only use classification decisions (1/-1), not real values. • Reducing multi-class to binary (Allwein et al, 2000) Showed that the best code matrix is problem-dependent; don’t address how to design code matrix. • Bunching algorithm (Dekel and Singer, 2002) Also learns code matrix and classifies, but more complicated than our algorithm and not applied to object detection. • Multitask learning (Caruana, 1997; …) Train tasks in parallel to improve generalization, share features. But not applied to object detection, nor in a boosting framework.

Our approach • Share features across objects, automatically selecting the best sharing pattern. • Benefits of shared features: – Efficiency – Accuracy – Generalization ability

Algorithm goals, for object recognition. We want to find the vocabulary of parts that can be shared We want share across different objects generic knowledge about detecting objects (eg, from the background). We want to share computations across classes so that computational cost < O(Number of classes)

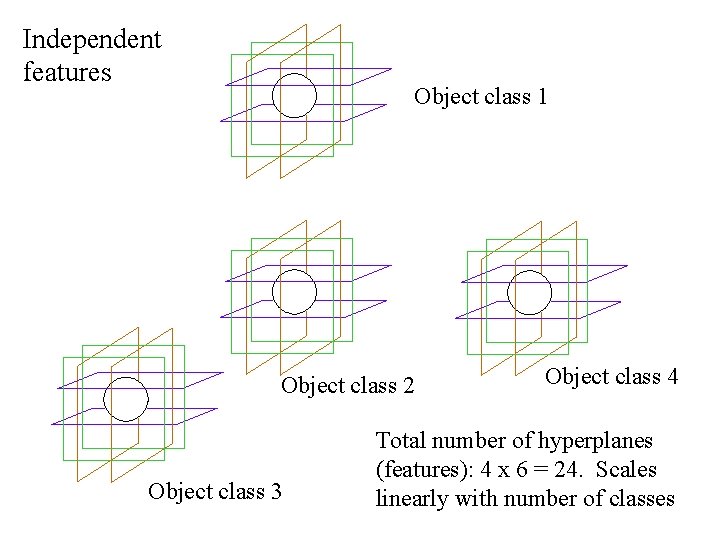

Independent features Object class 1 Object class 2 Object class 3 Object class 4 Total number of hyperplanes (features): 4 x 6 = 24. Scales linearly with number of classes

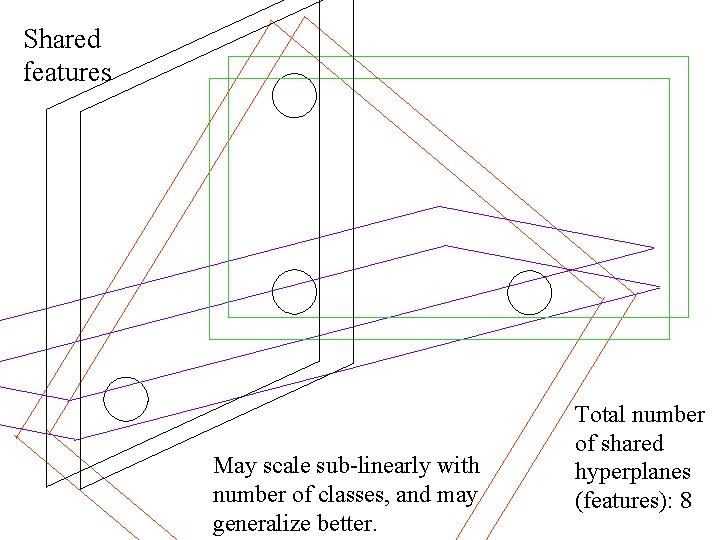

Shared features May scale sub-linearly with number of classes, and may generalize better. Total number of shared hyperplanes (features): 8

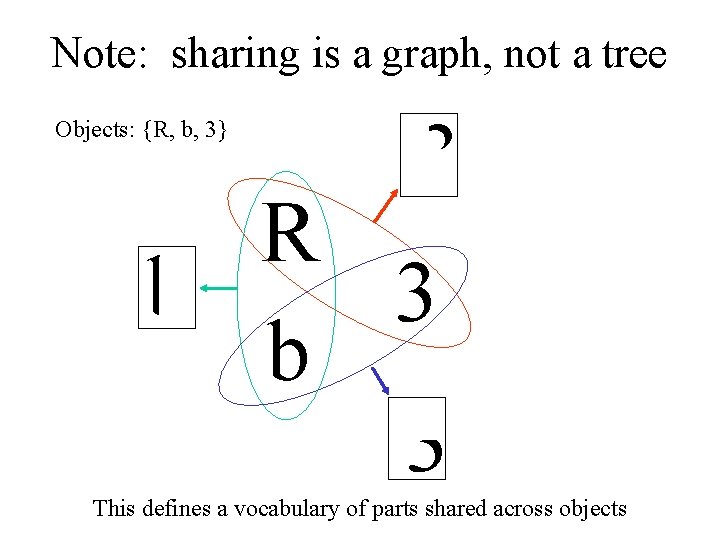

Note: sharing is a graph, not a tree Objects: {R, b, 3} 3 R b 3 This defines a vocabulary of parts shared across objects

At the algorithmic level • Our approach is a variation on boosting that allows for sharing features in a natural way. • So let’s review boosting (ada-boost demo)

Boosting demo

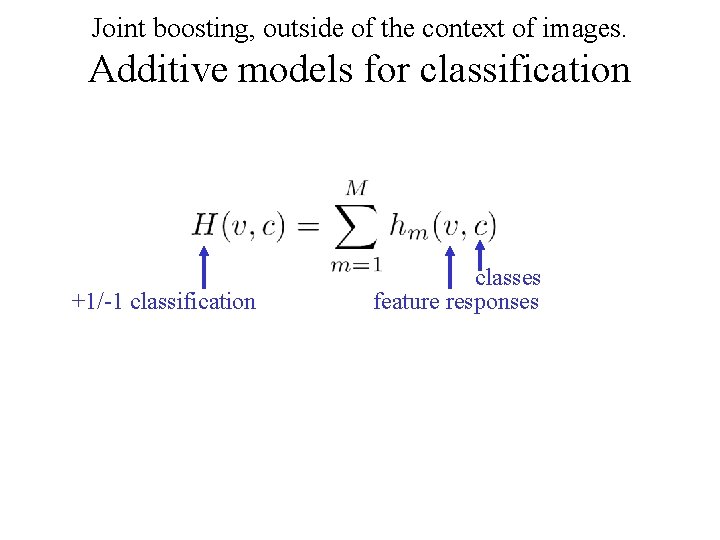

Joint boosting, outside of the context of images. Additive models for classification +1/-1 classification classes feature responses

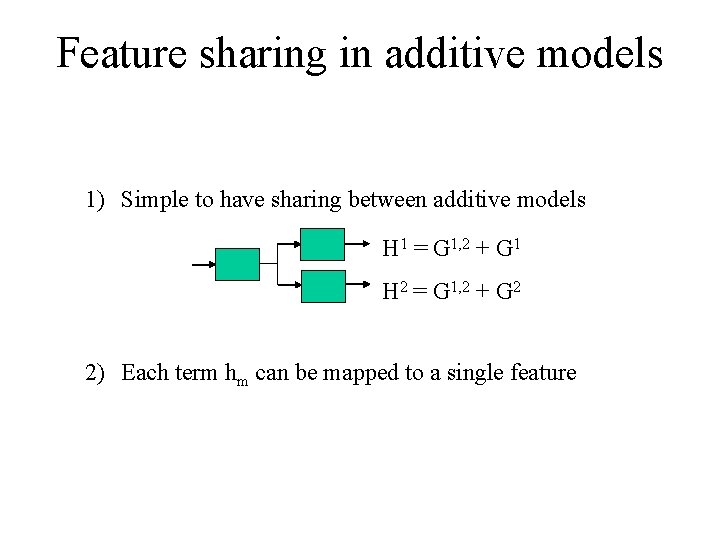

Feature sharing in additive models 1) Simple to have sharing between additive models H 1 = G 1, 2 + G 1 H 2 = G 1, 2 + G 2 2) Each term hm can be mapped to a single feature

Flavors of boosting • Different boosting algorithms use different loss functions or minimization procedures (Freund & Shapire, 1995; Friedman, Hastie, Tibshhirani, 1998). • We base our approach on Gentle boosting: learns faster than others (Friedman, Hastie, Tibshhirani, 1998; Lienahart, Kuranov, & Pisarevsky, 2003).

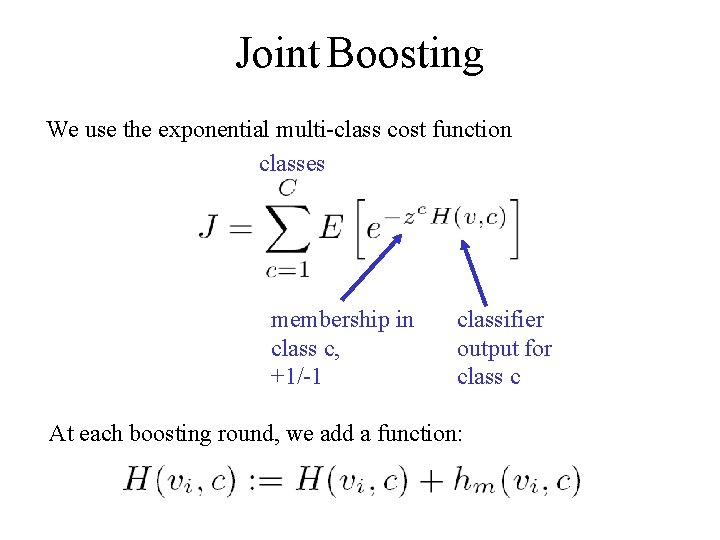

Joint Boosting We use the exponential multi-class cost function classes membership in class c, +1/-1 classifier output for class c At each boosting round, we add a function:

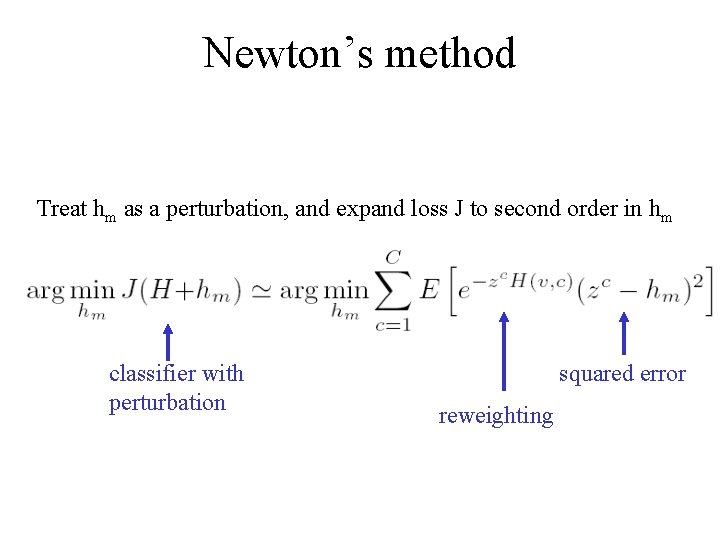

Newton’s method Treat hm as a perturbation, and expand loss J to second order in hm classifier with perturbation squared error reweighting

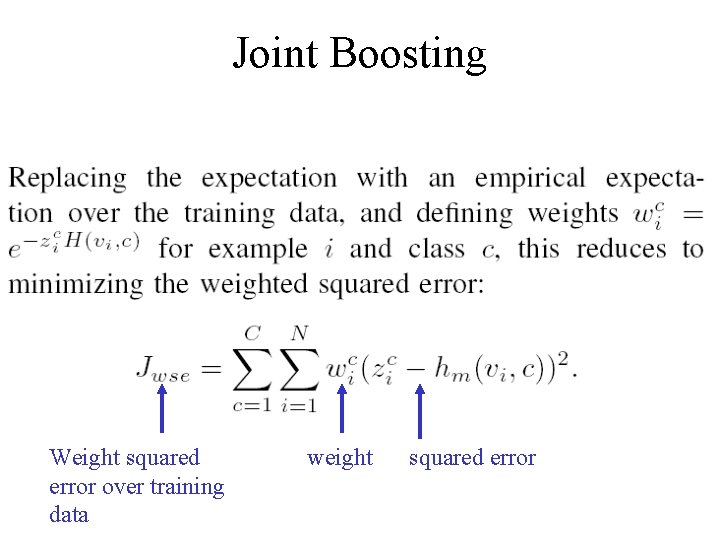

Joint Boosting Weight squared error over training data weight squared error

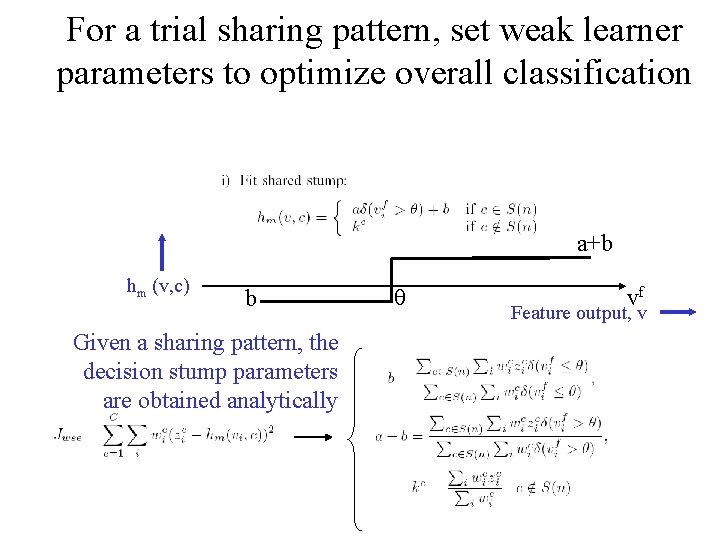

For a trial sharing pattern, set weak learner parameters to optimize overall classification a+b hm (v, c) b Given a sharing pattern, the decision stump parameters are obtained analytically q vf Feature output, v

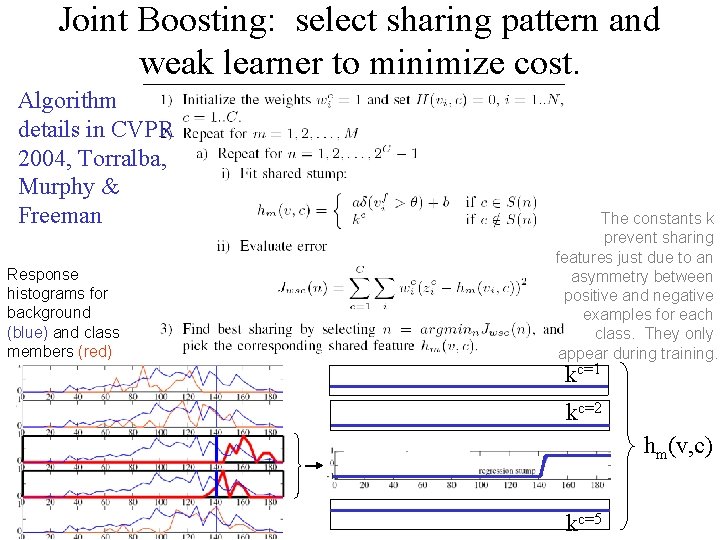

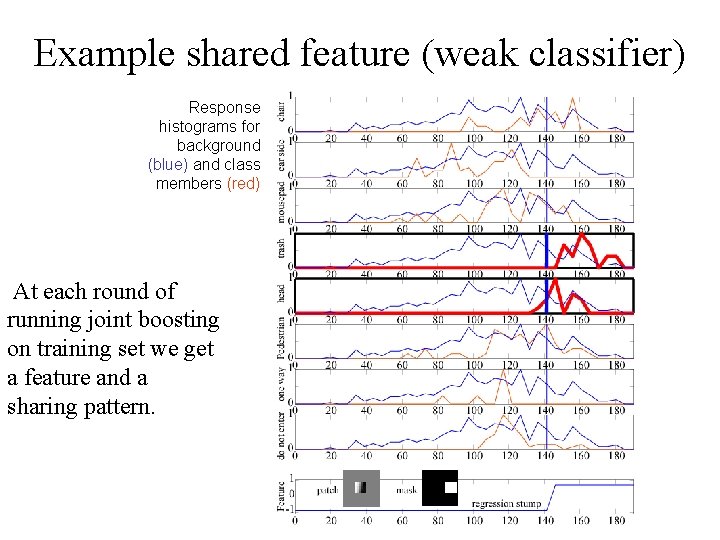

Joint Boosting: select sharing pattern and weak learner to minimize cost. Algorithm details in CVPR 2004, Torralba, Murphy & Freeman Response histograms for background (blue) and class members (red) The constants k prevent sharing features just due to an asymmetry between positive and negative examples for each class. They only appear during training. kc=1 kc=2 hm(v, c) kc=5

Approximate best sharing But this requires exploring 2 C – 1 possible sharing patterns Instead we use a first-best search: • S = [] • 1) We fit stumps for each class independently • 2) take best class - ci • S = [S ci] • fit stumps for [S ci] with ci not in S • go to 2, until length(S) = Nclasses • 3) select the sharing with smallest WLS error

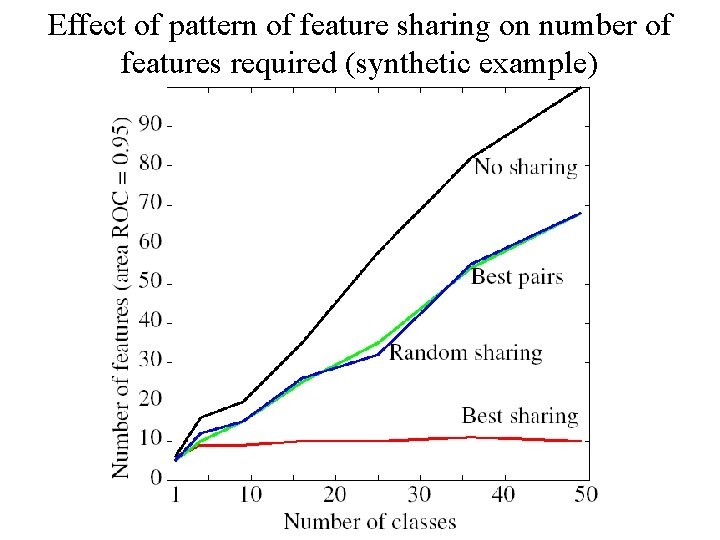

Effect of pattern of feature sharing on number of features required (synthetic example)

Effect of pattern of feature sharing on number of features required (synthetic example)

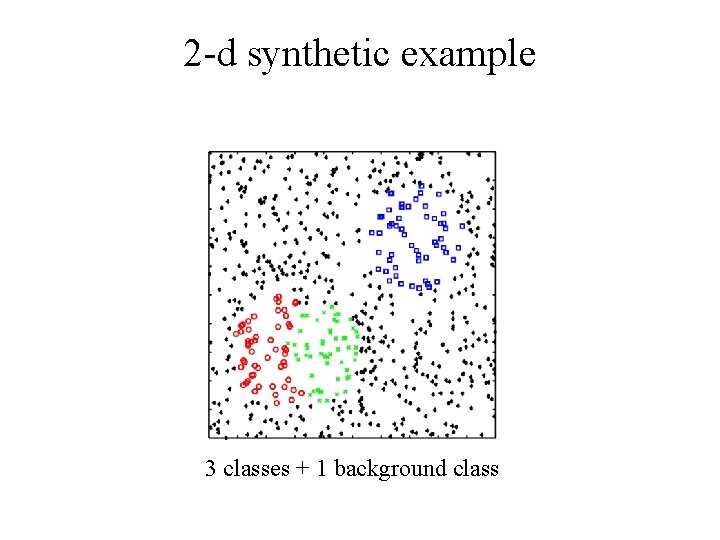

2 -d synthetic example 3 classes + 1 background class

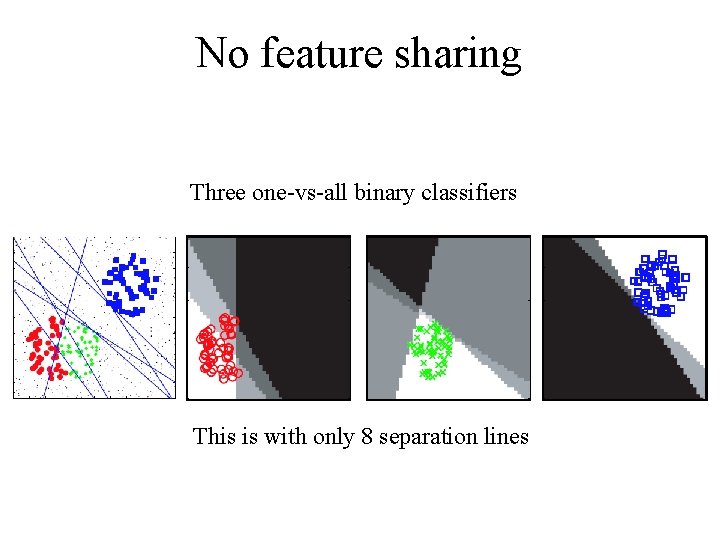

No feature sharing Three one-vs-all binary classifiers This is with only 8 separation lines

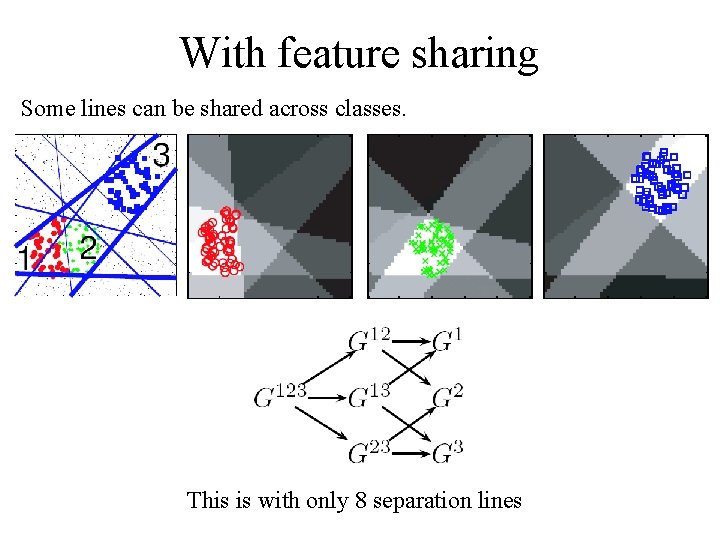

With feature sharing Some lines can be shared across classes. This is with only 8 separation lines

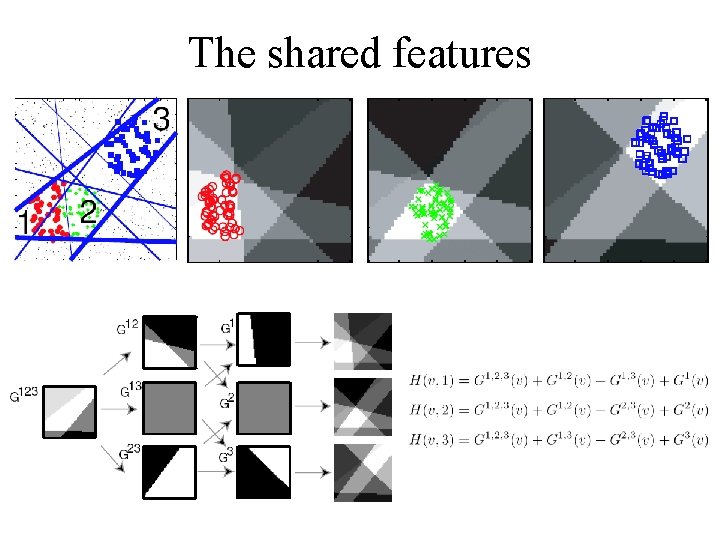

The shared features

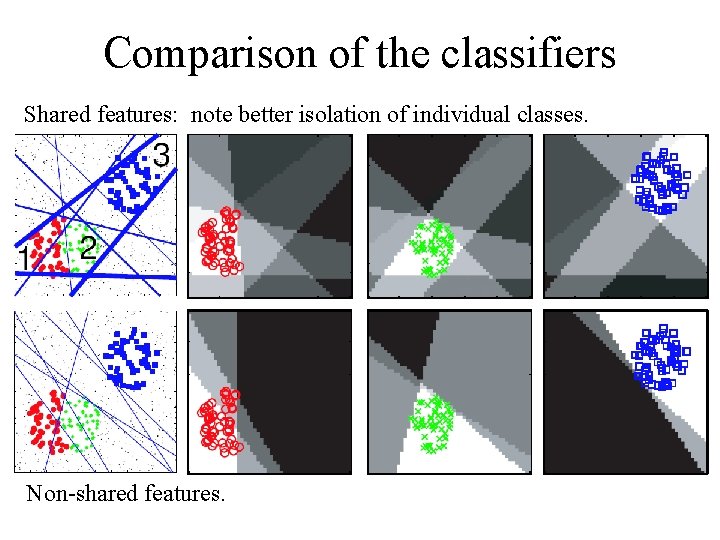

Comparison of the classifiers Shared features: note better isolation of individual classes. Non-shared features.

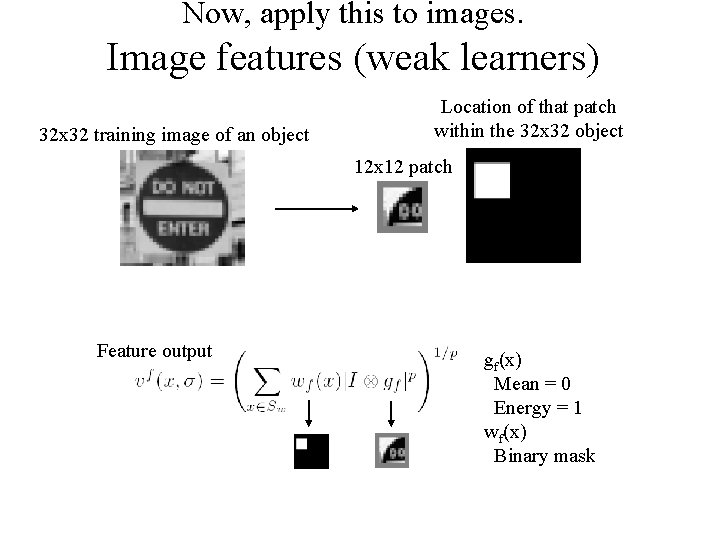

Now, apply this to images. Image features (weak learners) 32 x 32 training image of an object Location of that patch within the 32 x 32 object 12 x 12 patch Feature output gf(x) Mean = 0 Energy = 1 wf(x) Binary mask

The candidate features template position

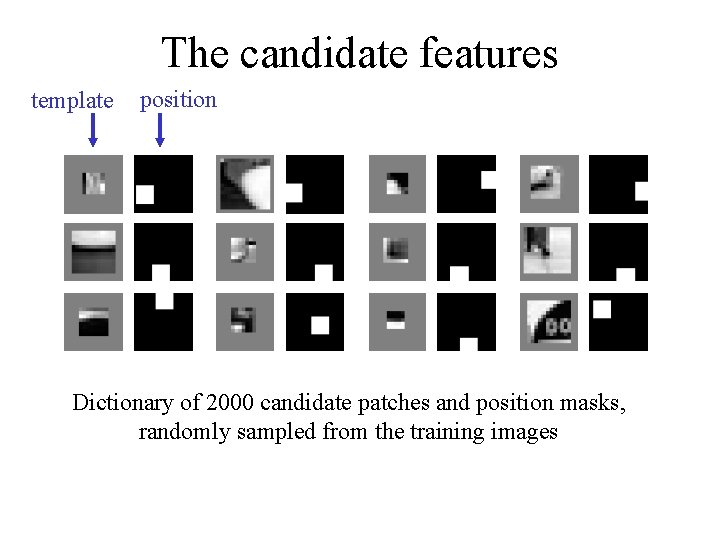

The candidate features template position Dictionary of 2000 candidate patches and position masks, randomly sampled from the training images

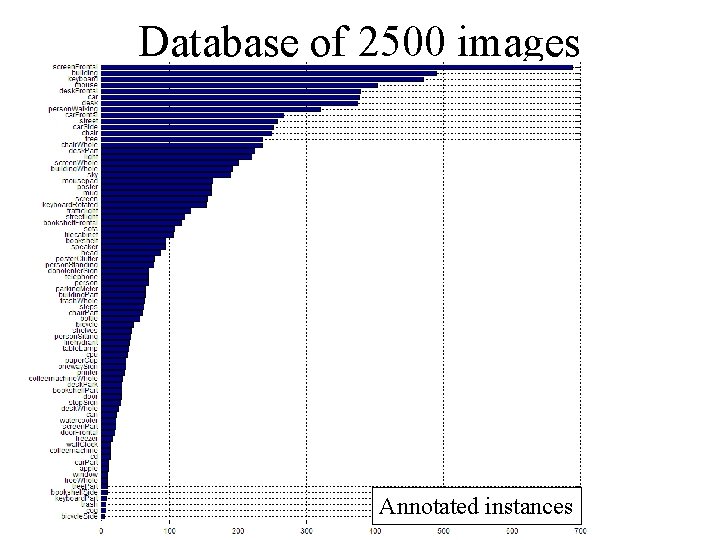

Database of 2500 images Annotated instances

![Multiclass object detection 21 objects We use [20, 50] training samples per object, and Multiclass object detection 21 objects We use [20, 50] training samples per object, and](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/188b51178f94099a5c5535fddcf72bf4/image-41.jpg)

Multiclass object detection 21 objects We use [20, 50] training samples per object, and about 20 times as many background examples as object examples.

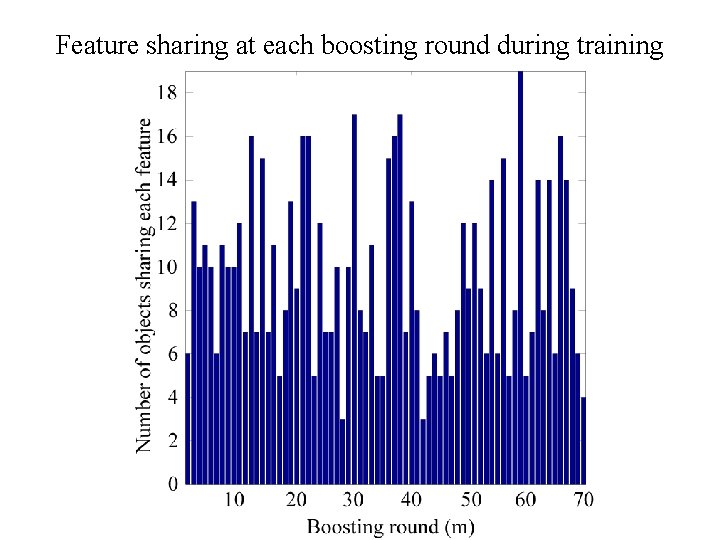

Feature sharing at each boosting round during training

Feature sharing at each boosting round during training

Example shared feature (weak classifier) Response histograms for background (blue) and class members (red) At each round of running joint boosting on training set we get a feature and a sharing pattern.

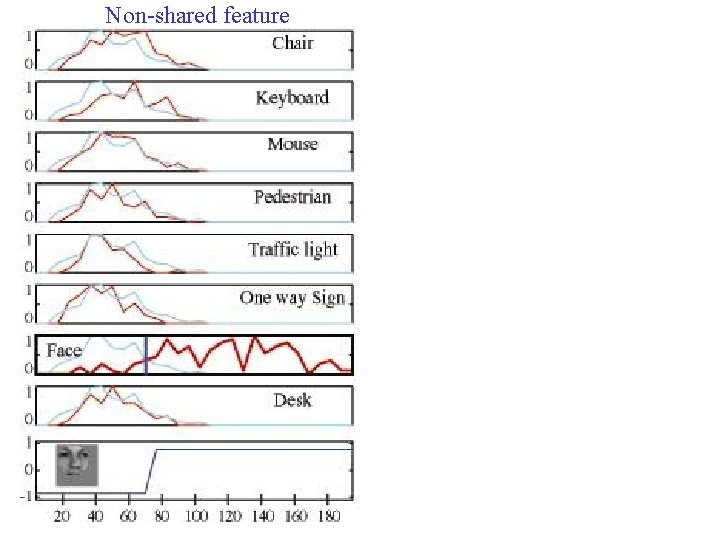

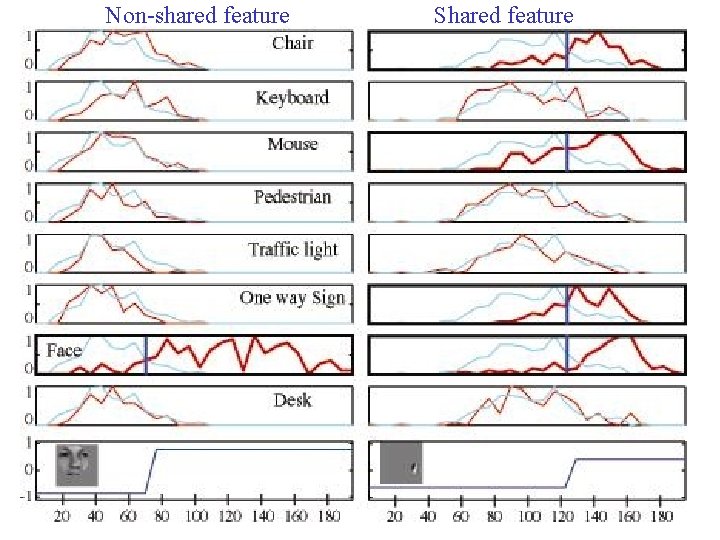

Non-shared feature Shared feature

Non-shared feature Shared feature

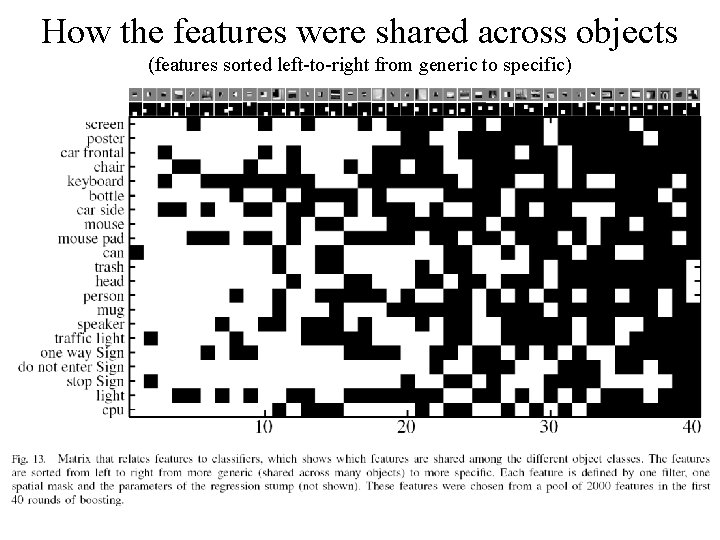

How the features were shared across objects (features sorted left-to-right from generic to specific)

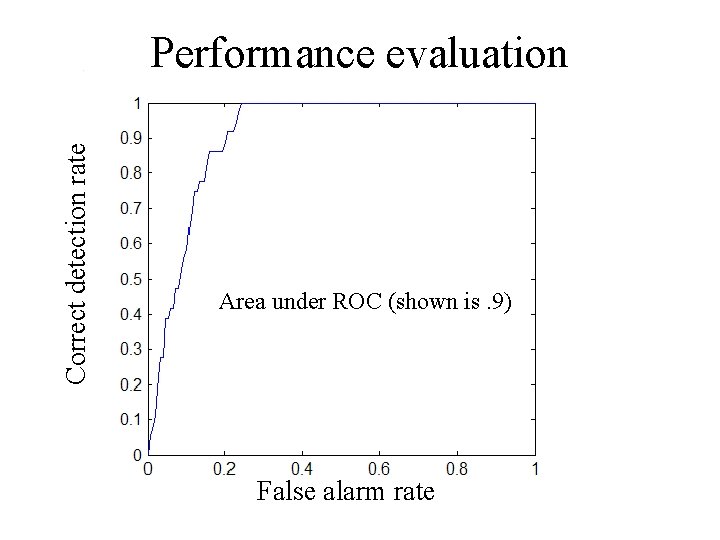

Correct detection rate Performance evaluation Area under ROC (shown is. 9) False alarm rate

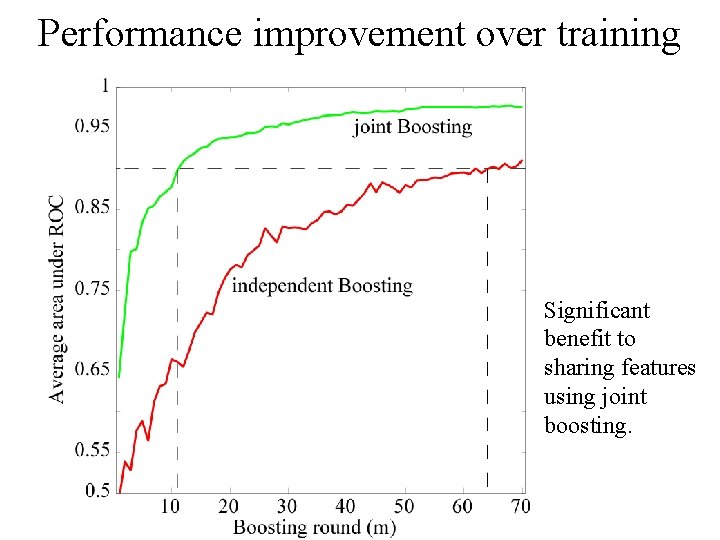

Performance improvement over training Significant benefit to sharing features using joint boosting.

ROC curves for our 21 object database • How will this work under training-starved or feature-starved conditions? • Presumably, in the real world, we will always be starved for training data and for features.

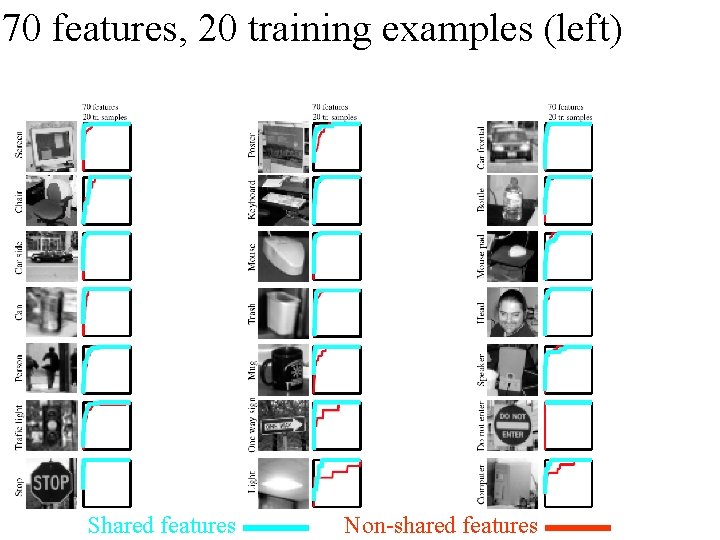

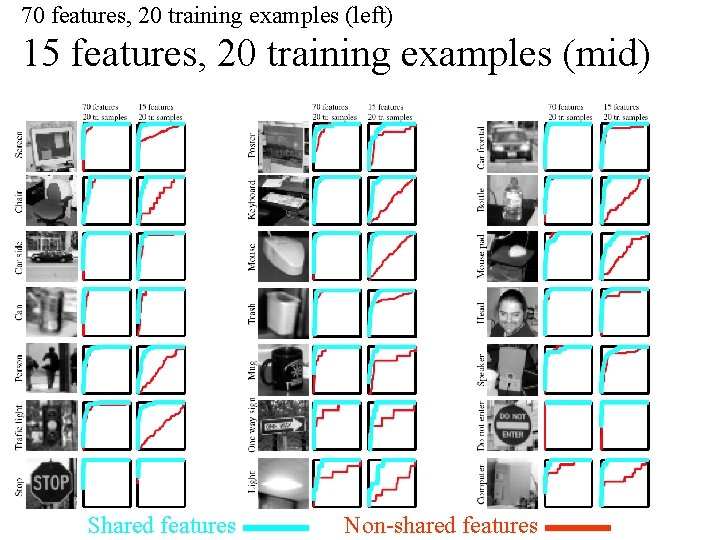

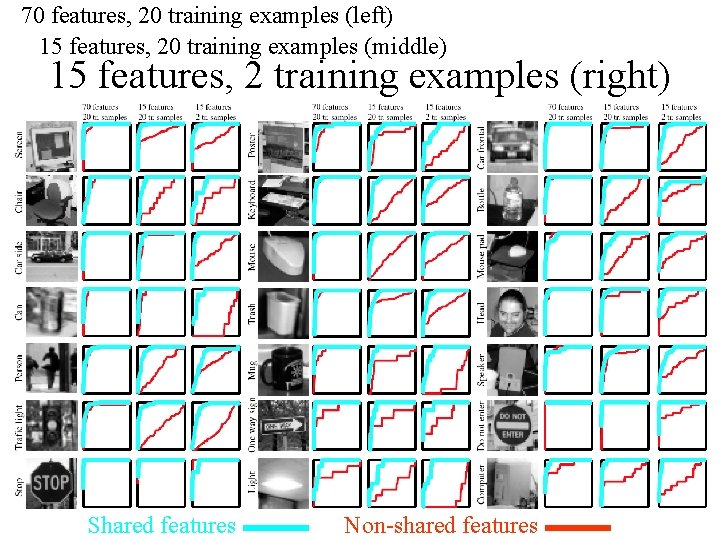

70 features, 20 training examples (left) Shared features Non-shared features

70 features, 20 training examples (left) 15 features, 20 training examples (mid) Shared features Non-shared features

70 features, 20 training examples (left) 15 features, 20 training examples (middle) 15 features, 2 training examples (right) Shared features Non-shared features

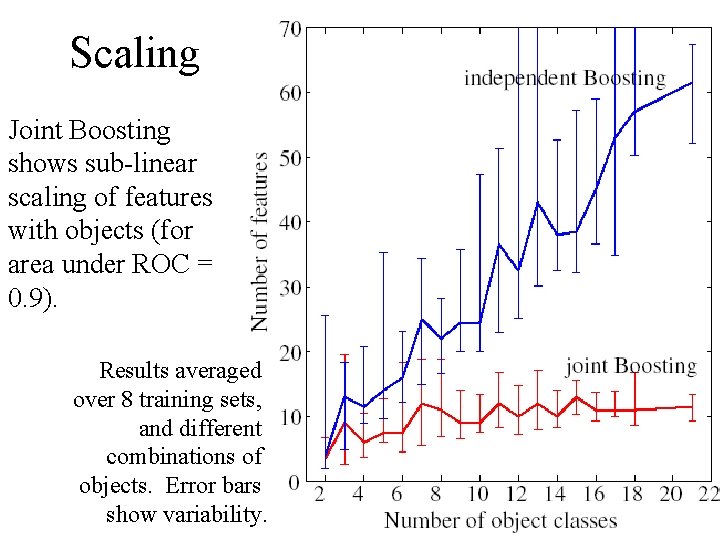

Scaling Joint Boosting shows sub-linear scaling of features with objects (for area under ROC = 0. 9). Results averaged over 8 training sets, and different combinations of objects. Error bars show variability.

Red: shared features Blue: independent features

Red: shared features Blue: independent features

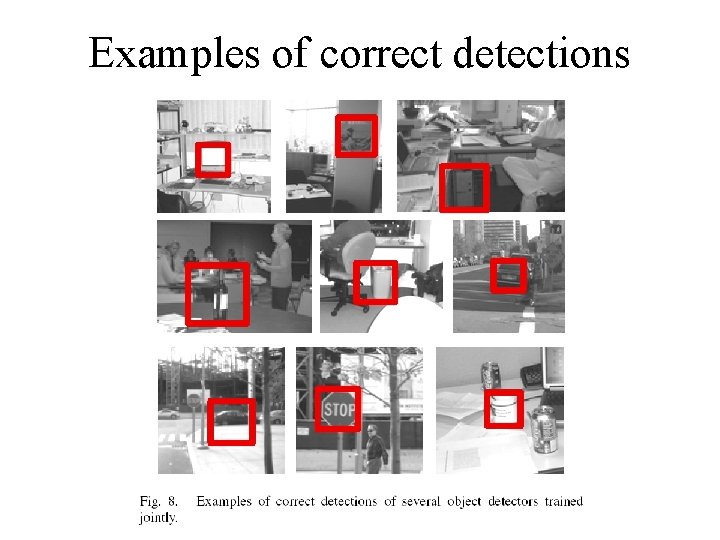

Examples of correct detections

What makes good features? • Depends on whether we are doing singleclass or multi-class detection…

Generic vs. specific features Parts derived from training a binary classifier. Parts derived from training a joint classifier with 20 more objects. In both cases ~100% detection rate with 0 false alarms

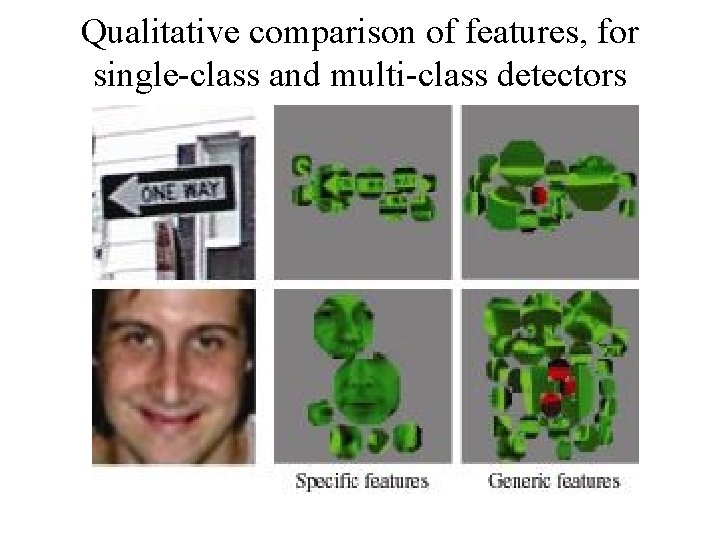

Qualitative comparison of features, for single-class and multi-class detectors

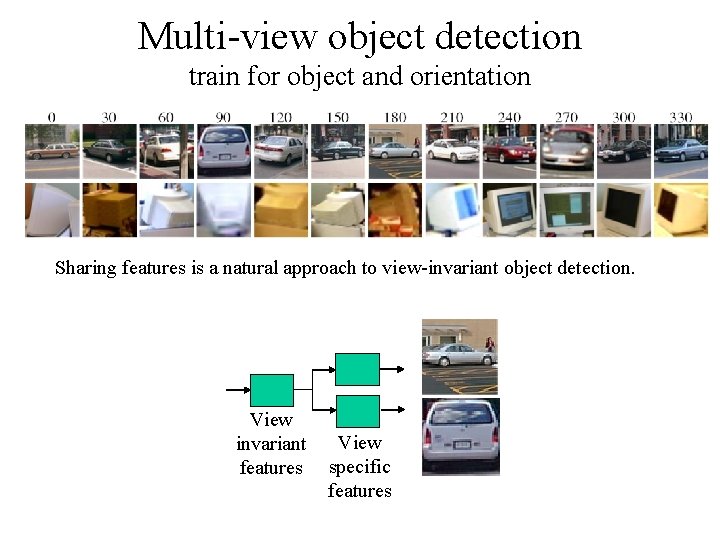

Multi-view object detection train for object and orientation Sharing features is a natural approach to view-invariant object detection. View invariant features View specific features

Multi-view object detection Sharing is not a tree. Depends also on 3 D symmetries. … …

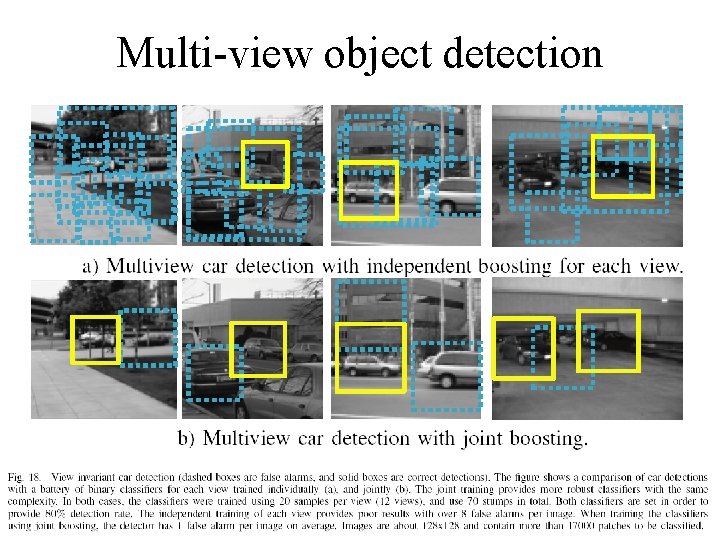

Multi-view object detection

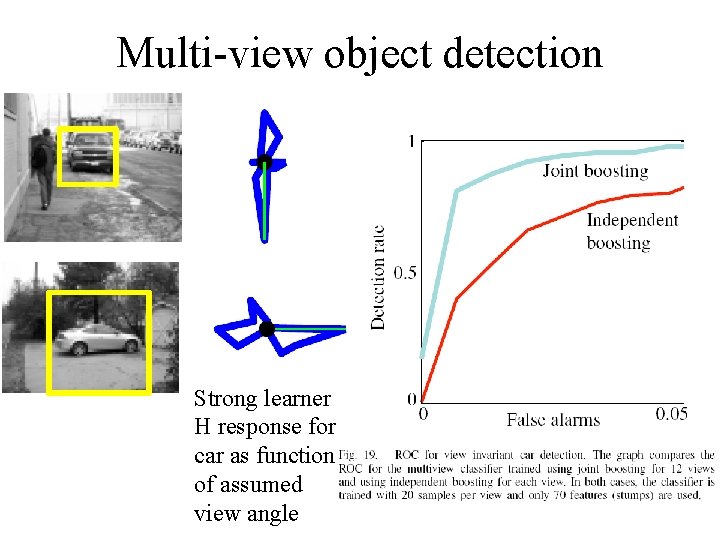

Multi-view object detection Strong learner H response for car as function of assumed view angle

Visual summary…

Features Object units

Summary • Argued that feature sharing will be an essential part of scaling up object detection to hundreds or thousands of objects (and viewpoints). • We introduced joint boosting, a generalization to boosting that incorporates feature sharing in a natural way. • Initial results (up to 30 objects) show the desired scaling behavior for # features vs # objects. • The shared features are observed to generalize better, allowing learning from fewer examples, using fewer features.

end

- Slides: 69