Shame and dissociation in complex trauma disorders Emerging

- Slides: 72

Shame and dissociation in complex trauma disorders: Emerging insights from the empirical literature Martin Dorahy Department of Psychology University of Canterbury New Zealand Martin. dorahy@canterbury. ac. nz

“Shame…is such an acutely painful and disorganizing experience that we wish it would end quickly and have no taste for introspecting it” H. B. Lewis, 1987, p. 1

Plan Shame: Overview, definitions, functions, manifestations Shame and Trauma Shame, trauma and dissociation Q&A Shame, dissociation and relationship functioning Shame and therapy

Shame defined “Shame can be defined simply as the feeling we have when we evaluate our actions, feelings, or behavior, and conclude that we have done wrong. It encompasses the whole of ourselves; it generates a wish to hide, to disappear or even to die” (M. Lewis, 1992, p. 2) Shame is the affect of inferiority (Kaufman, 1989) ‘Seeing oneself negatively in the eyes of others’ (Scheff, 2003, p. 244) ‘Shame is an experience of one’s felt sense of self disintegrating in relation to a dysregulating other’ (De. Young, 2015. p. xii). Shame is inherently a social emotion and threat to the social bond/relationships (Lewis, Scheff, 2003) SHAME IS RELATED TO THE SELF signal 1971;

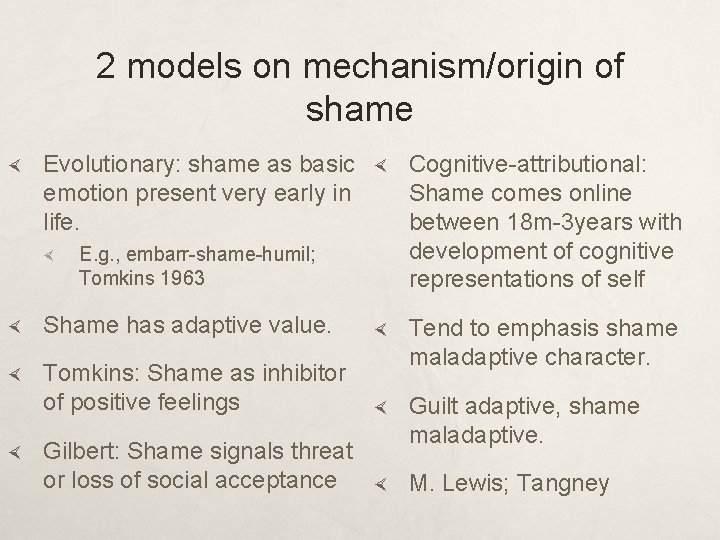

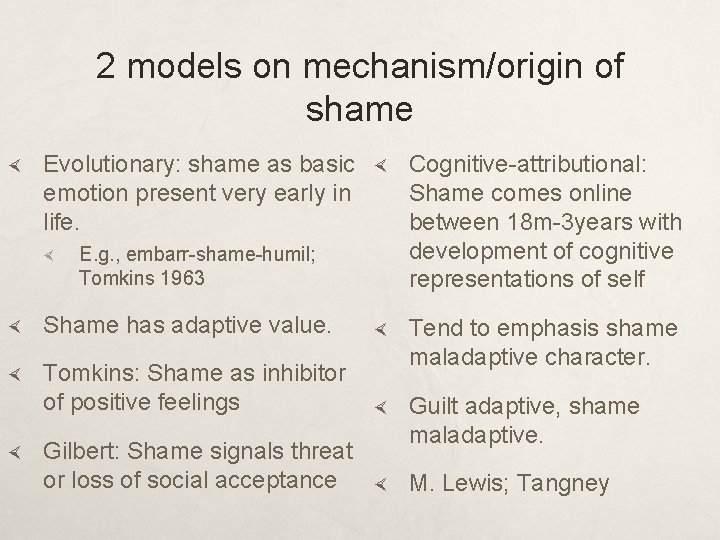

2 models on mechanism/origin of shame Evolutionary: shame as basic emotion present very early in life. Cognitive-attributional: Shame comes online between 18 m-3 years with development of cognitive representations of self E. g. , embarr-shame-humil; Tomkins 1963 Shame has adaptive value. Tomkins: Shame as inhibitor of positive feelings Tend to emphasis shame maladaptive character. Gilbert: Shame signals threat or loss of social acceptance Guilt adaptive, shame maladaptive. M. Lewis; Tangney

Shame and development “Shame is embedded in the attachment system and occurs in the first stages of life in response to perceived rejection or separation from caregivers. Shame alerts the child to the threat of separation, and then action can be taken to protect the attachment bond. The cycles of attachment rupture and repair in the infant-caregiver dyad are fundamental for emotional regulation and shame plays an important role in this process” Schimmenti, 2012, p. 202

Shame not by nature pathological Shame is not pathological per se, but when it becomes pervasive or disavowed/dissociated (i. e. , maladaptive regulation), it has a negative impact on a person’s life. Schimmenti, 2012

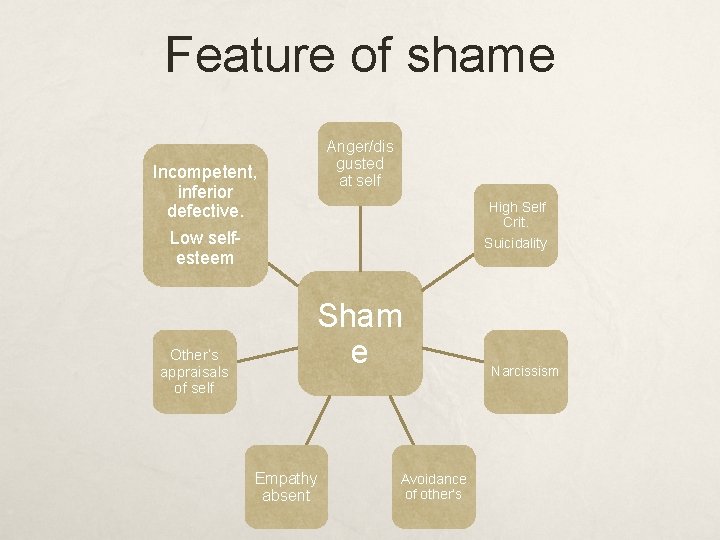

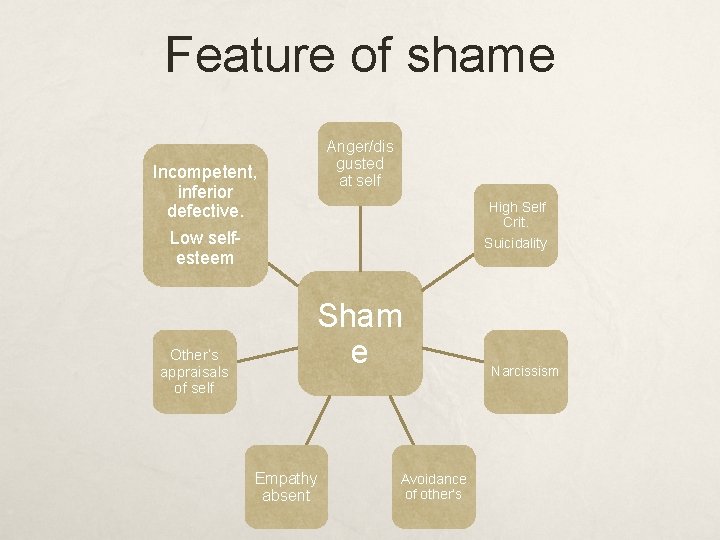

Feature of shame Anger/dis gusted at self Incompetent, inferior defective. Low selfesteem Other’s appraisals of self High Self Crit. Suicidality Sham e Empathy absent Avoidance of other’s Narcissism

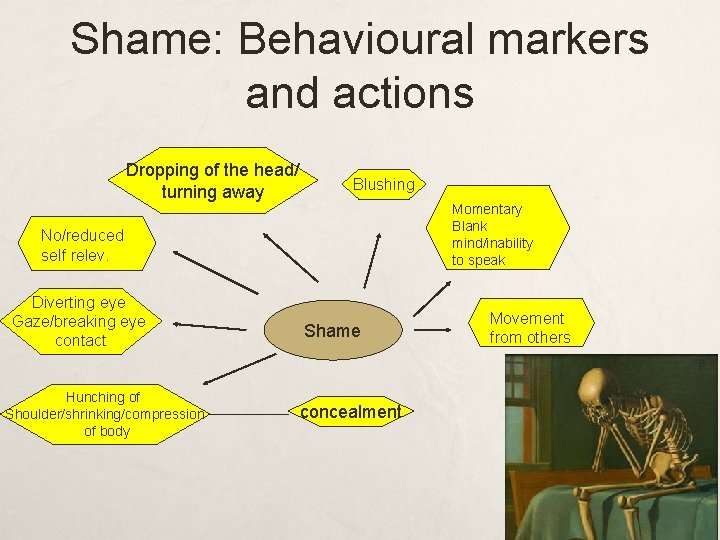

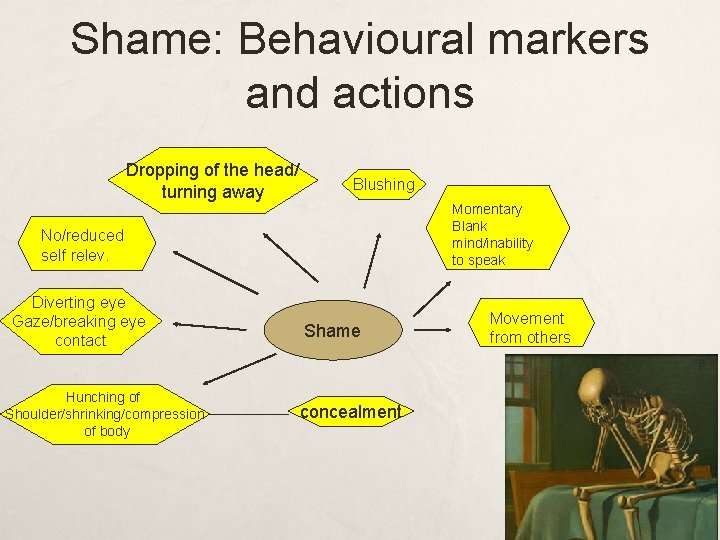

Shame: Behavioural markers and actions Dropping of the head/ turning away Blushing Momentary Blank mind/inability to speak No/reduced self relev. Diverting eye Gaze/breaking eye contact Hunching of Shoulder/shrinking/compression of body Shame concealment Movement from others

Shame & trauma

Shame and trauma Shame intimately linked to traumatic events, especially those of a relational nature (Andrews, Brewin, Rose & Kirk, 2000; Dorahy, 2010; Dorahy & Clearwater, 2012; Harvey, Dorahy, Vertue, & Duthie, 2012; Feiring & Taska, 2005). Relational trauma characterised by dominance, subordination and control evokes a strong shame response

Trauma and shame (cont. ) People feel ashamed for 1) What happened, 2) How they (e. g. , their body) responded 3) Who they are Boon et al. , 2011; Dorahy & Clearwater, 2012, Herman, 2011; Talbot, 1996 Herman (2011) argues that PTSD resulting from relational trauma can be conceptualised as both an anxiety disorder and a shame disorder.

Abuse and shame 2 key areas where early abuse directly relates to pathological shame is the development of: Healthy narcissism (so the individual can assert and defend oneself) Bad or malignant internal objects (so relationships are skewed and distorted – e. g. , rejection is expected. Schimmenti, 2012

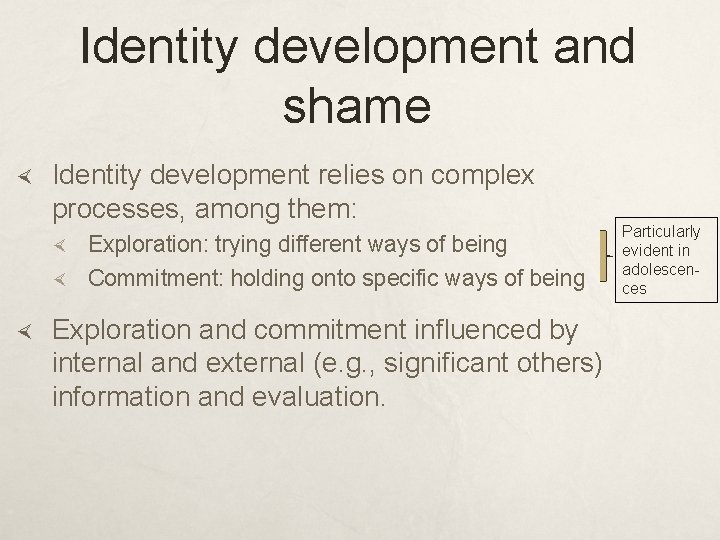

Identity development and shame Identity development relies on complex processes, among them: Exploration: trying different ways of being Commitment: holding onto specific ways of being Exploration and commitment influenced by internal and external (e. g. , significant others) information and evaluation. Particularly evident in adolescences

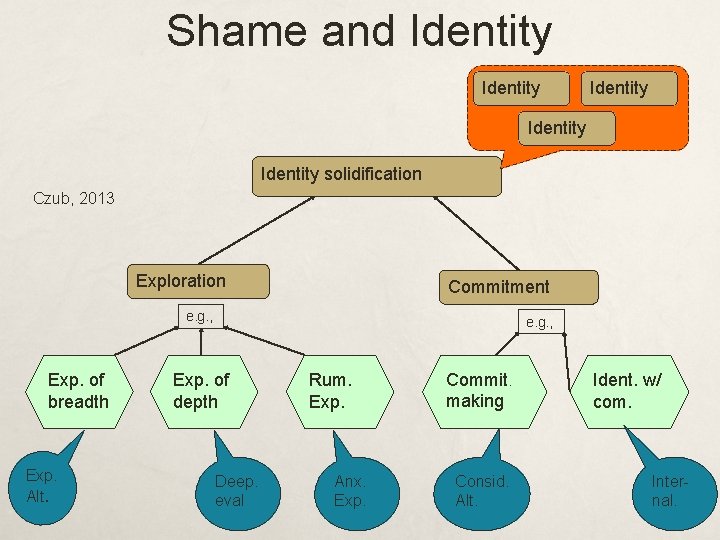

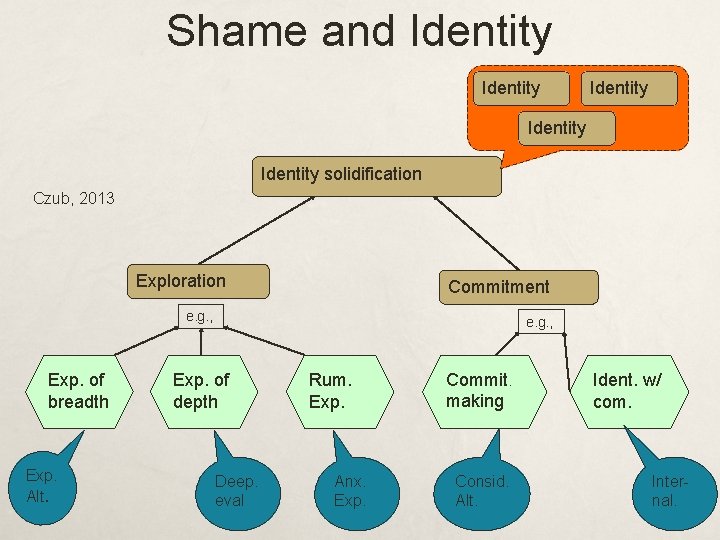

Shame and Identity Identity solidification Czub, 2013 Exploration Commitment e. g. , Exp. of breadth Exp. Alt. e. g. , Exp. of depth Deep. eval Rum. Exp. Anx. Exp. Commit. making Consid. Alt. Ident. w/ com. Internal.

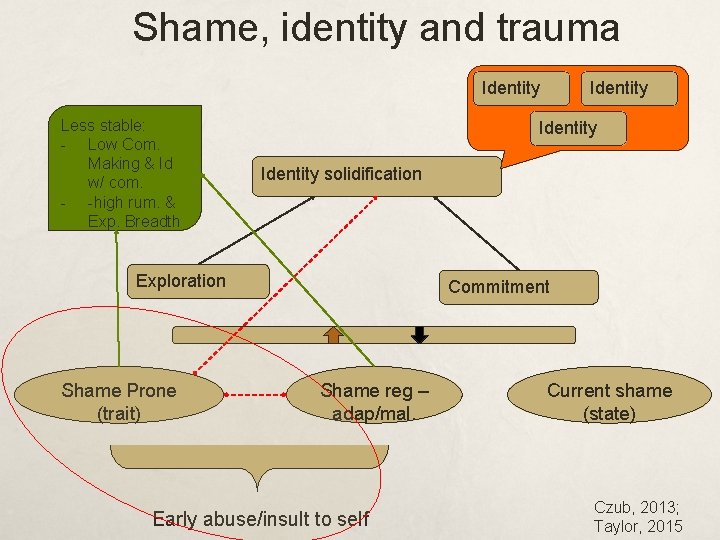

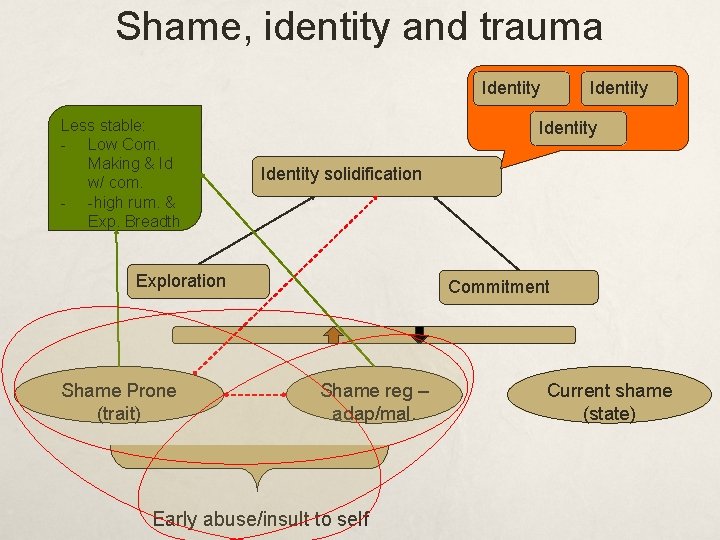

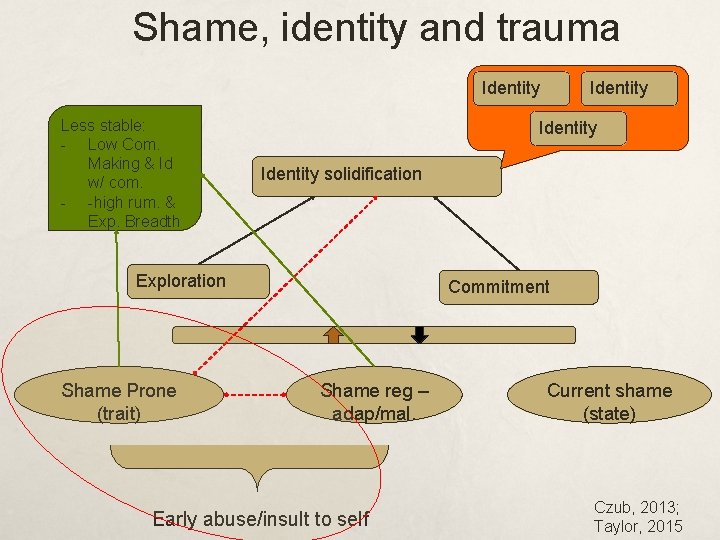

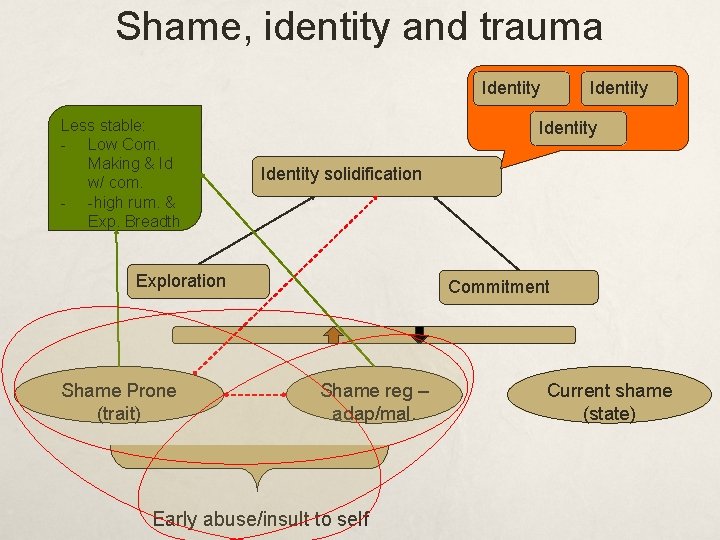

Shame, identity and trauma Identity Less stable: - Low Com. Making & Id w/ com. - -high rum. & Exp. Breadth Identity solidification Exploration Shame Prone (trait) Identity Commitment Shame reg – adap/mal. Early abuse/insult to self Current shame (state) Czub, 2013; Taylor, 2015

Trauma and shame Many theorists have proposed a link between exposure to trauma and increases in feeling shame (e. g. , Chefetz, 2015; Herman, 2011; Lee et al. , 2001; Schimmenti, 2012; Talbot, 1996; Wilson et al. , 2006) EG. , ‘Shame and shame regulation play a role in the exacerbation and perpetuation of posttrauma disorders’ (Taylor, 2015, p. 1) What about research findings?

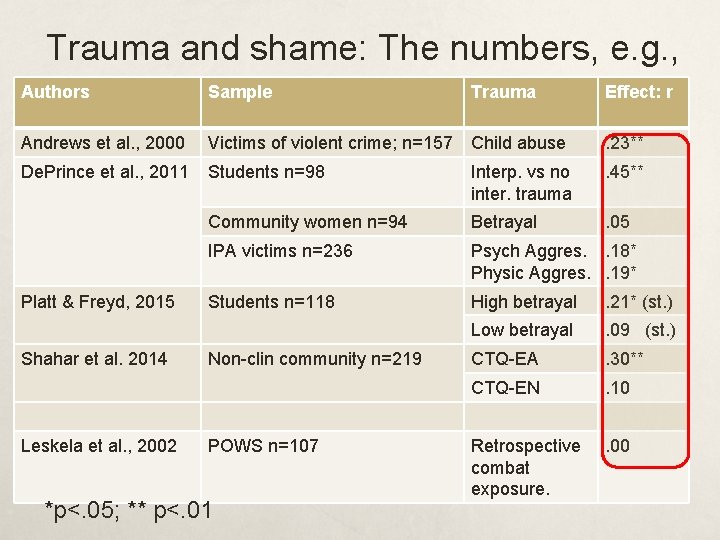

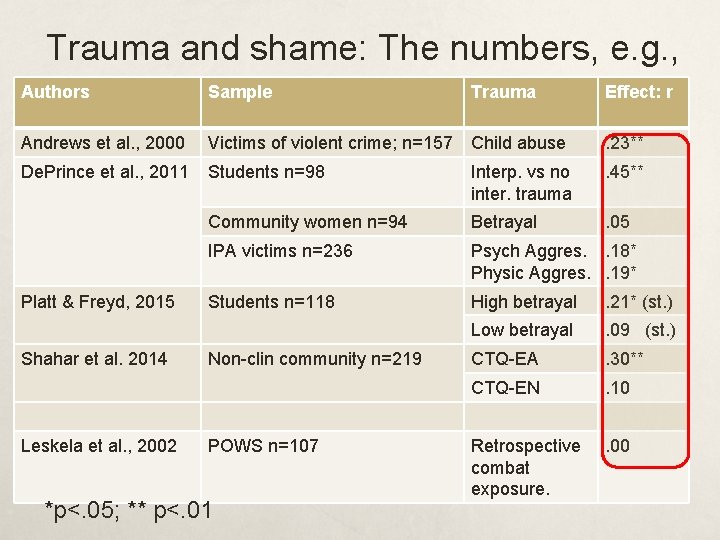

Trauma and shame: The numbers, e. g. , Authors Sample Trauma Effect: r Andrews et al. , 2000 Victims of violent crime; n=157 Child abuse . 23** De. Prince et al. , 2011 Students n=98 Interp. vs no inter. trauma . 45** Community women n=94 Betrayal . 05 IPA victims n=236 Psych Aggres. . 18* Physic Aggres. . 19* Students n=118 High betrayal . 21* (st. ) Low betrayal . 09 (st. ) CTQ-EA . 30** CTQ-EN . 10 Retrospective combat exposure. . 00 Platt & Freyd, 2015 Shahar et al. 2014 Leskela et al. , 2002 Non-clin community n=219 POWS n=107 *p<. 05; ** p<. 01

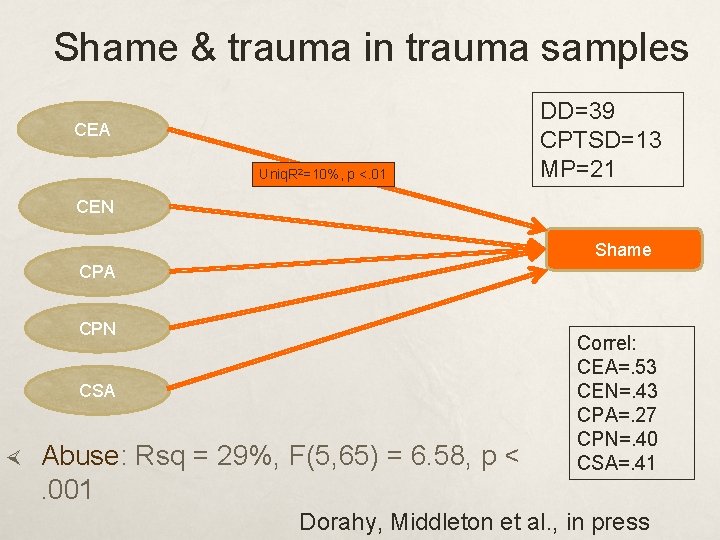

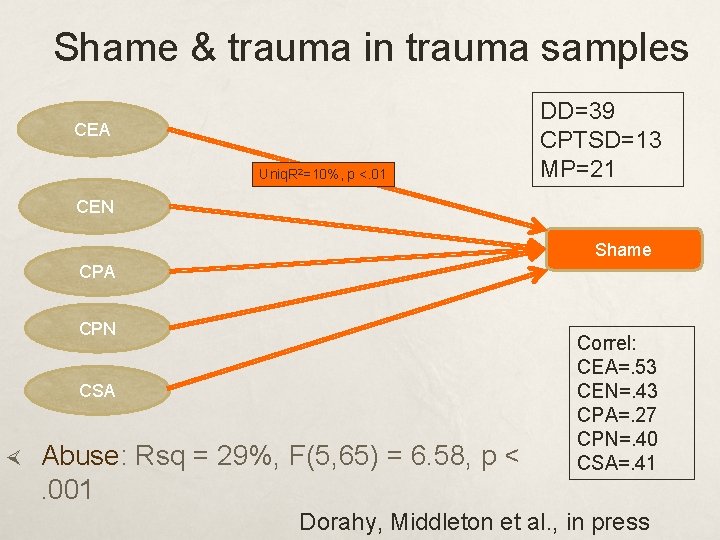

Shame & trauma in trauma samples CEA Uniq. R 2=10%, p <. 01 DD=39 CPTSD=13 MP=21 CEN Shame CPA CPN CSA Abuse: Rsq = 29%, F(5, 65) = 6. 58, p <. 001 Correl: CEA=. 53 CEN=. 43 CPA=. 27 CPN=. 40 CSA=. 41 Dorahy, Middleton et al. , in press

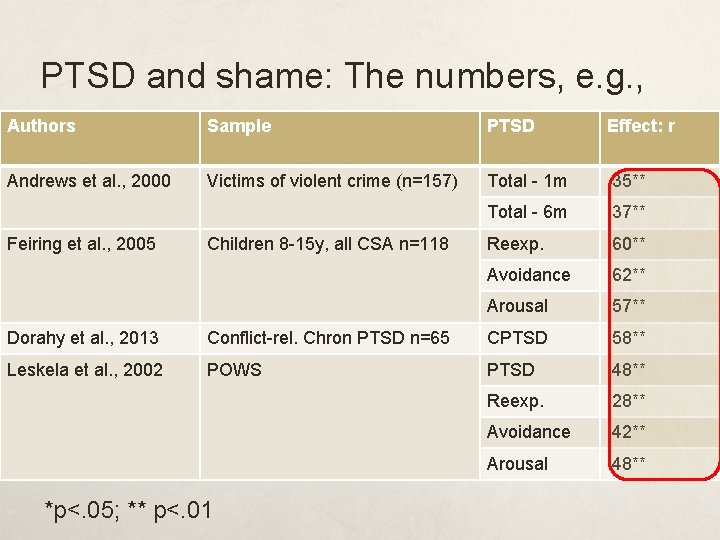

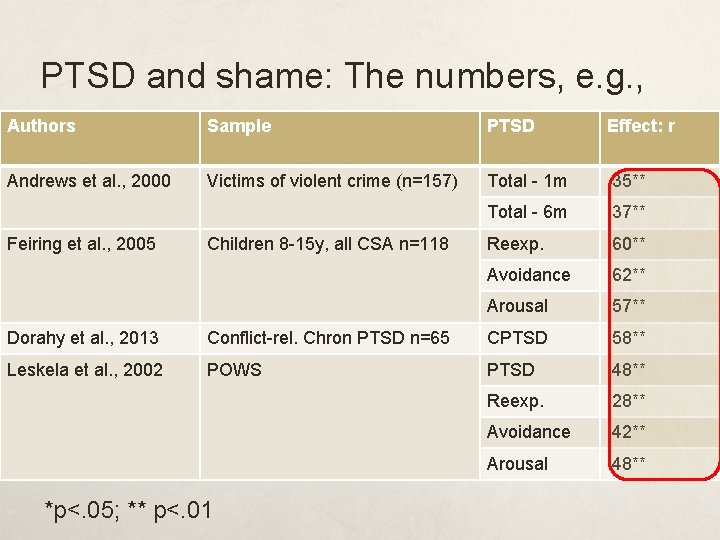

PTSD and shame: The numbers, e. g. , Authors Sample PTSD Effect: r Andrews et al. , 2000 Victims of violent crime (n=157) Total - 1 m . 35** Total - 6 m . 37** Reexp. . 60** Avoidance . 62** Arousal . 57** Feiring et al. , 2005 Children 8 -15 y, all CSA n=118 Dorahy et al. , 2013 Conflict-rel. Chron PTSD n=65 CPTSD . 58** Leskela et al. , 2002 POWS PTSD . 48** Reexp. . 28** Avoidance . 42** Arousal . 48** *p<. 05; ** p<. 01

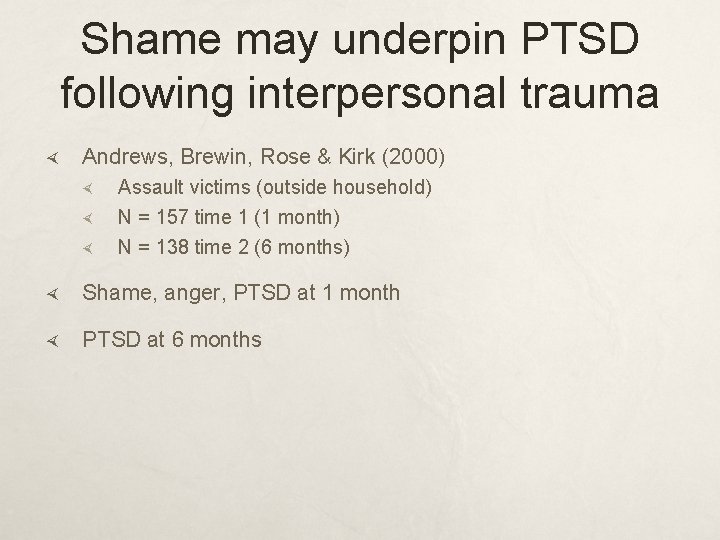

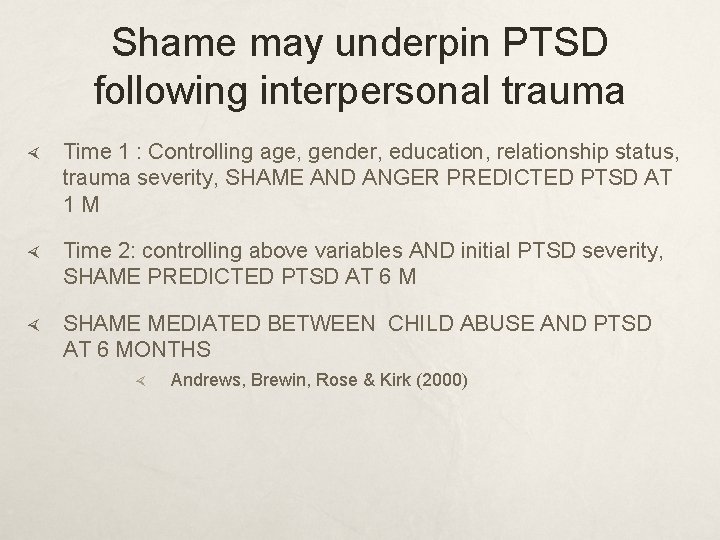

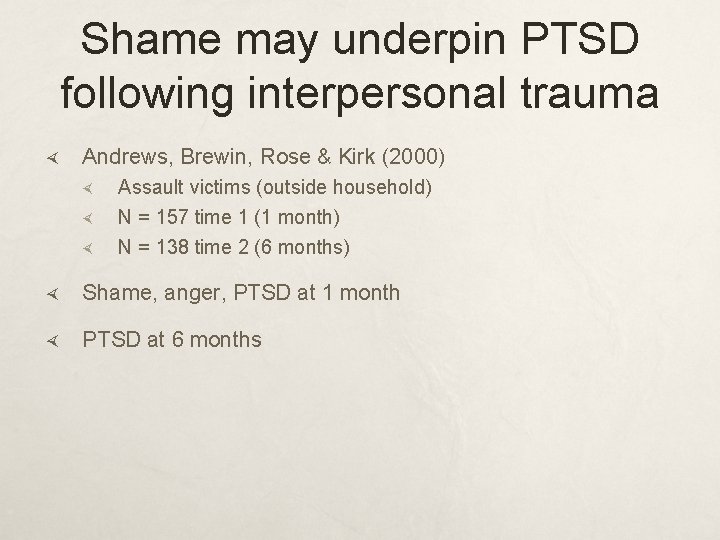

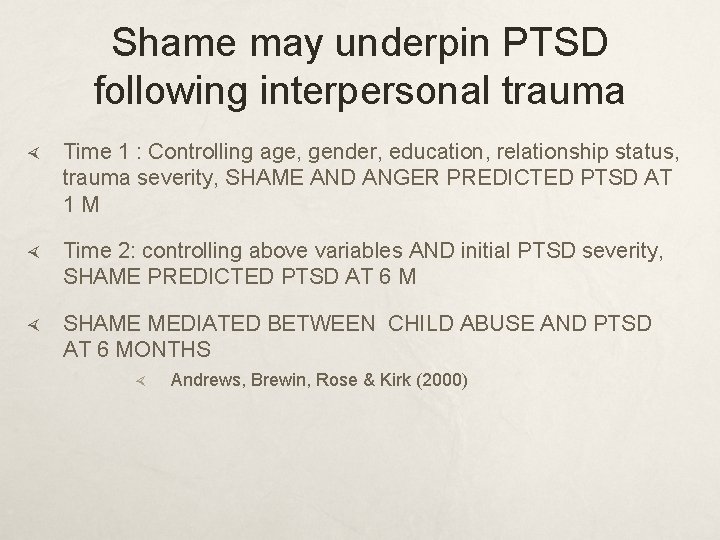

Shame may underpin PTSD following interpersonal trauma Andrews, Brewin, Rose & Kirk (2000) Assault victims (outside household) N = 157 time 1 (1 month) N = 138 time 2 (6 months) Shame, anger, PTSD at 1 month PTSD at 6 months

Shame may underpin PTSD following interpersonal trauma Time 1 : Controlling age, gender, education, relationship status, trauma severity, SHAME AND ANGER PREDICTED PTSD AT 1 M Time 2: controlling above variables AND initial PTSD severity, SHAME PREDICTED PTSD AT 6 M SHAME MEDIATED BETWEEN CHILD ABUSE AND PTSD AT 6 MONTHS Andrews, Brewin, Rose & Kirk (2000)

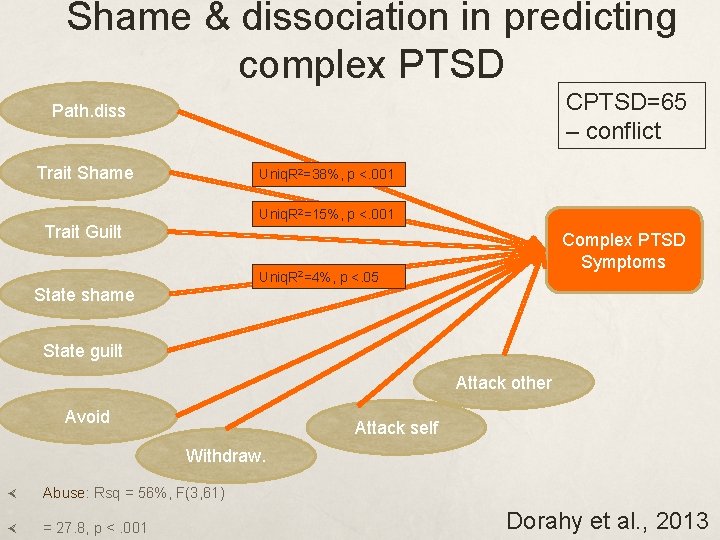

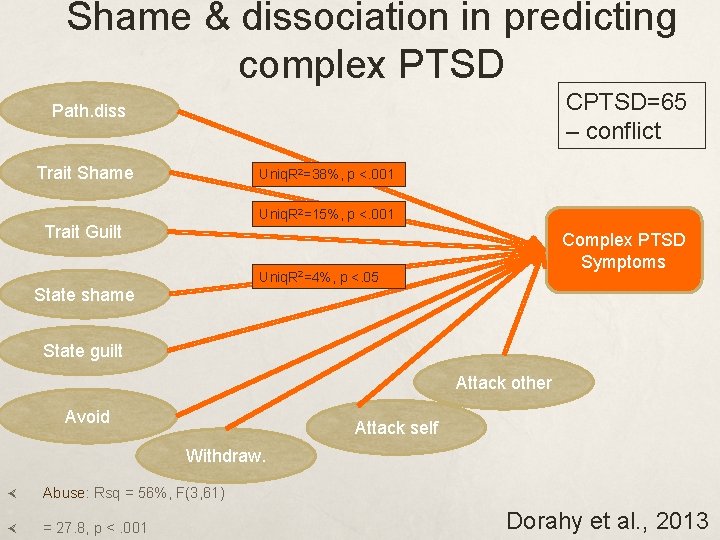

Shame & dissociation in predicting complex PTSD CPTSD=65 – conflict Path. diss Trait Shame Uniq. R 2=38%, p <. 001 Uniq. R 2=15%, p <. 001 Trait Guilt Complex PTSD Symptoms Uniq. R 2=4%, p <. 05 State shame State guilt Attack other Avoid Attack self Withdraw. Abuse: Rsq = 56%, F(3, 61) = 27. 8, p <. 001 Dorahy et al. , 2013

Shame and PTSD Shame associated with slower recovery from PTSD (Brewin & Holmes, 2003

‘shame as a traumatic memory’ Matos & Pinto-Gouveia (2010) argued and found evidence for child and adolescent shame experiences having similar characteristics to trauma memories (e. g. , intrusive, avoided, arousing).

‘shame as a traumatic memory’ Shame trauma memories acted as a moderator between shame feelings & depression i. e. , if shame experiences are represented internally like a trauma memory depression increases. ? Same for PTSD, CPTSD, DDs

Shame and current threat Harman & Lee (2010) 49 trauma survivors (e. g. , accidents, assaults); 45 PTSD Shame positively correlated with self-criticism; selfhatred Shame contributes to sense of ongoing threat that maintains PTSD symptoms like avoidance and arousal

Shame, identity and trauma Identity Less stable: - Low Com. Making & Id w/ com. - -high rum. & Exp. Breadth Identity solidification Exploration Shame Prone (trait) Identity Commitment Shame reg – adap/mal. Early abuse/insult to self Current shame (state)

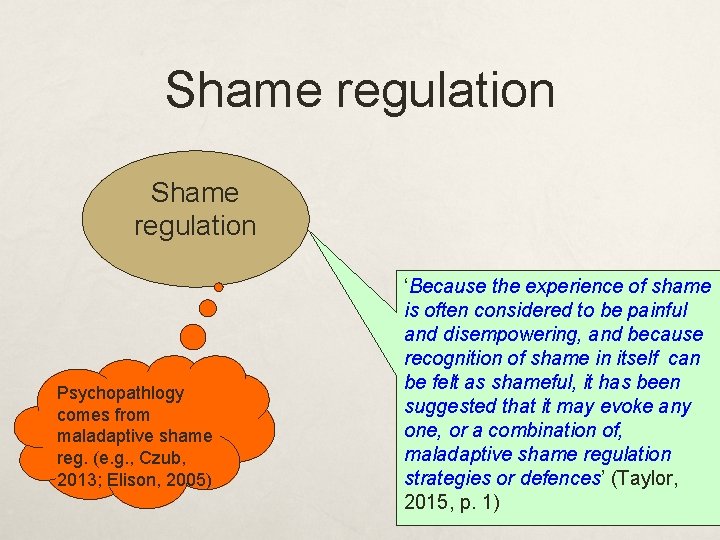

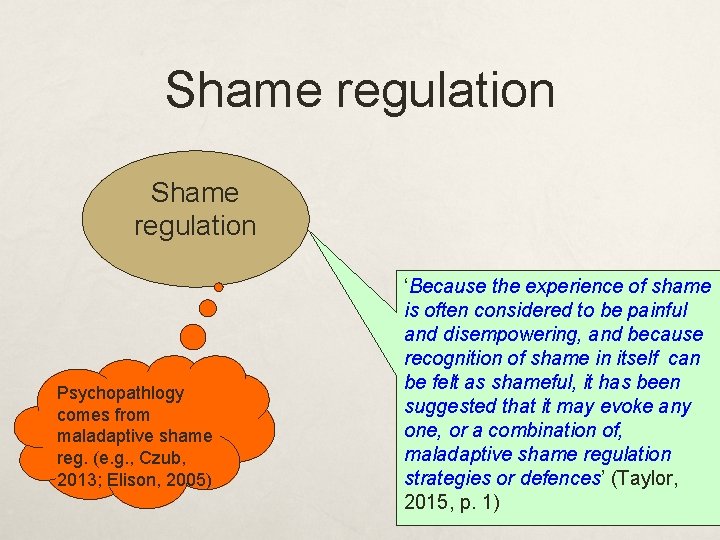

Shame regulation Psychopathlogy comes from maladaptive shame reg. (e. g. , Czub, 2013; Elison, 2005) ‘Because the experience of shame is often considered to be painful and disempowering, and because recognition of shame in itself can be felt as shameful, it has been suggested that it may evoke any one, or a combination of, maladaptive shame regulation strategies or defences’ (Taylor, 2015, p. 1)

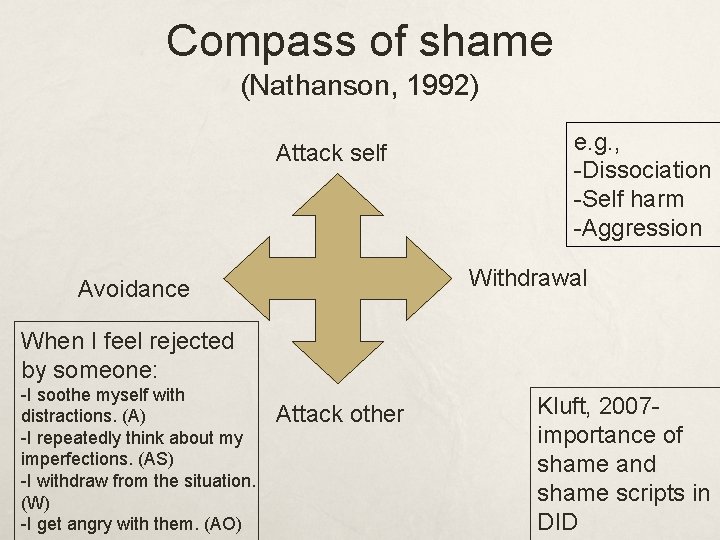

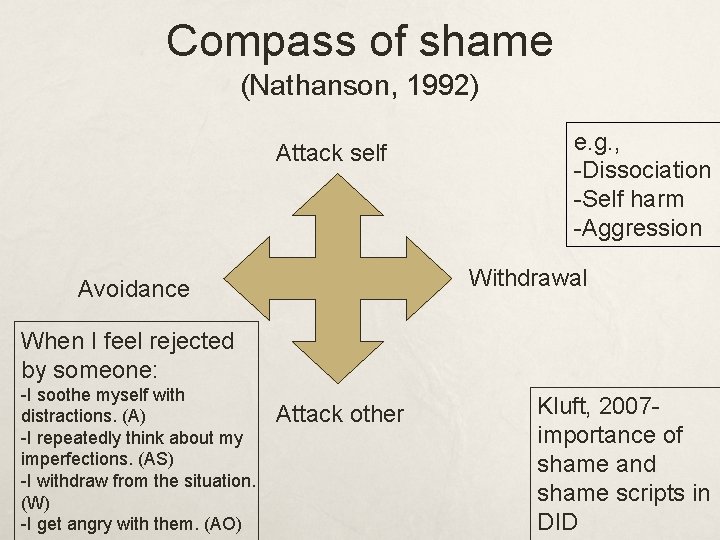

Compass of shame (Nathanson, 1992) Attack self e. g. , -Dissociation -Self harm -Aggression Withdrawal Avoidance When I feel rejected by someone: -I soothe myself with distractions. (A) -I repeatedly think about my imperfections. (AS) -I withdraw from the situation. (W) -I get angry with them. (AO) Attack other Kluft, 2007 importance of shame and shame scripts in DID

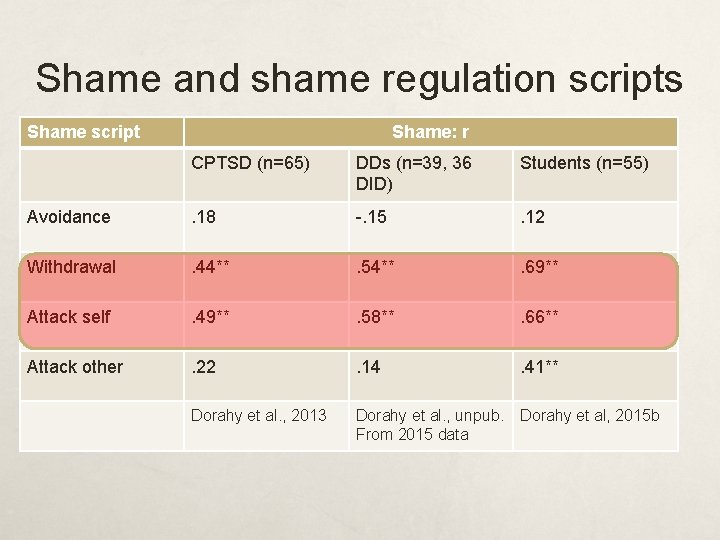

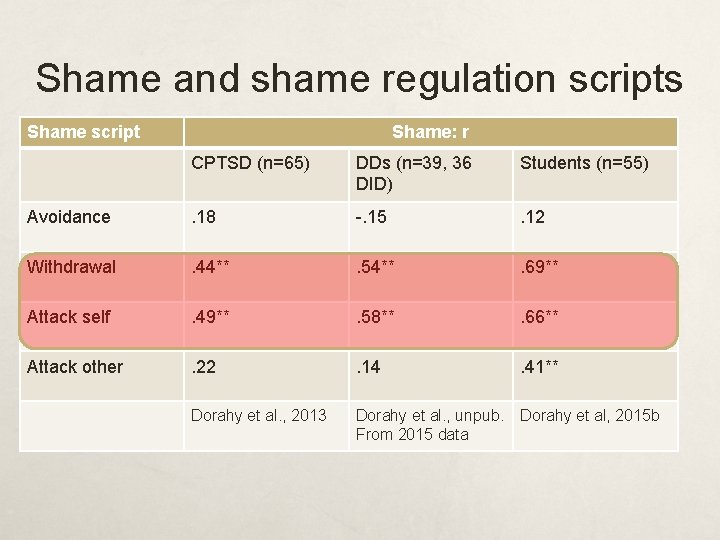

Shame and shame regulation scripts Shame script Shame: r CPTSD (n=65) DDs (n=39, 36 DID) Students (n=55) Avoidance . 18 -. 15 . 12 Withdrawal . 44** . 54** . 69** Attack self . 49** . 58** . 66** Attack other . 22 . 14 . 41** Dorahy et al. , 2013 Dorahy et al. , unpub. From 2015 data Dorahy et al, 2015 b

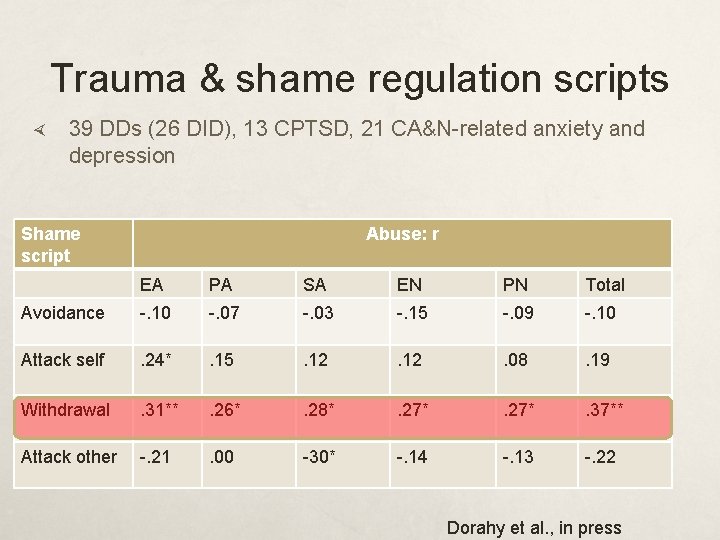

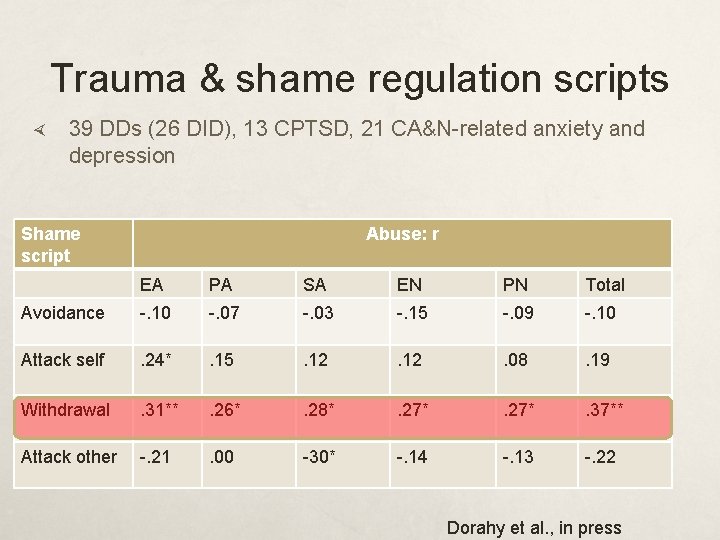

Trauma & shame regulation scripts 39 DDs (26 DID), 13 CPTSD, 21 CA&N-related anxiety and depression Shame script Abuse: r EA PA SA EN PN Total Avoidance -. 10 -. 07 -. 03 -. 15 -. 09 -. 10 Attack self . 24* . 15 . 12 . 08 . 19 Withdrawal . 31** . 26* . 28* . 27* . 37** Attack other -. 21 . 00 -30* -. 14 -. 13 -. 22 Dorahy et al. , in press

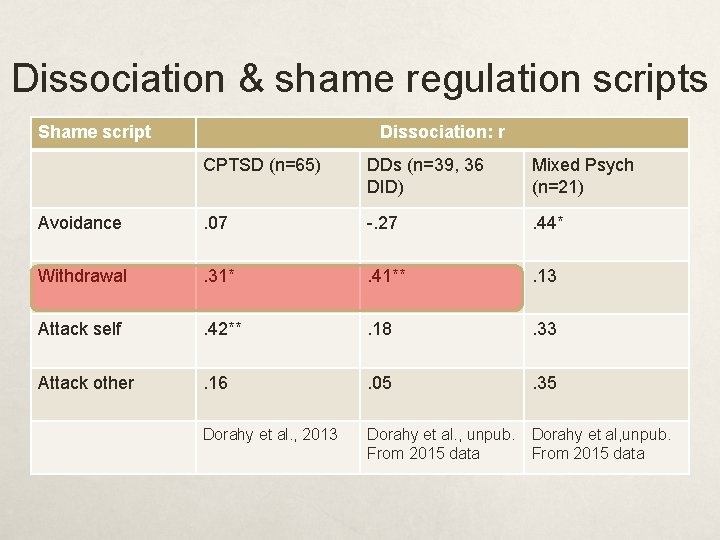

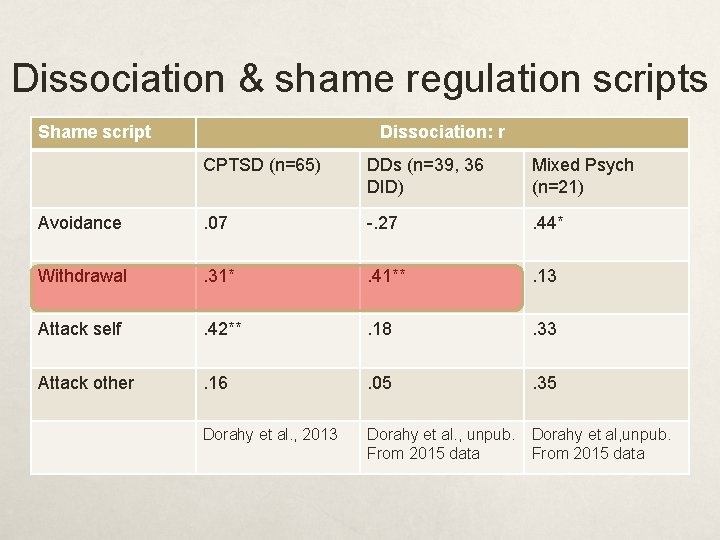

Dissociation & shame regulation scripts Shame script Dissociation: r CPTSD (n=65) DDs (n=39, 36 DID) Mixed Psych (n=21) Avoidance . 07 -. 27 . 44* Withdrawal . 31* . 41** . 13 Attack self . 42** . 18 . 33 Attack other . 16 . 05 . 35 Dorahy et al. , 2013 Dorahy et al. , unpub. From 2015 data Dorahy et al, unpub. From 2015 data

Shame, trauma & dissociation

Trauma, shame and dissociation Shame typically has a positive and moderatestrong strength correlation to dissociation (e. g. , ≈ r =. 05) E. g. , Dorahy et al. , 2013 This relationship tends to be stronger in traumatised than non-traumatised individuals

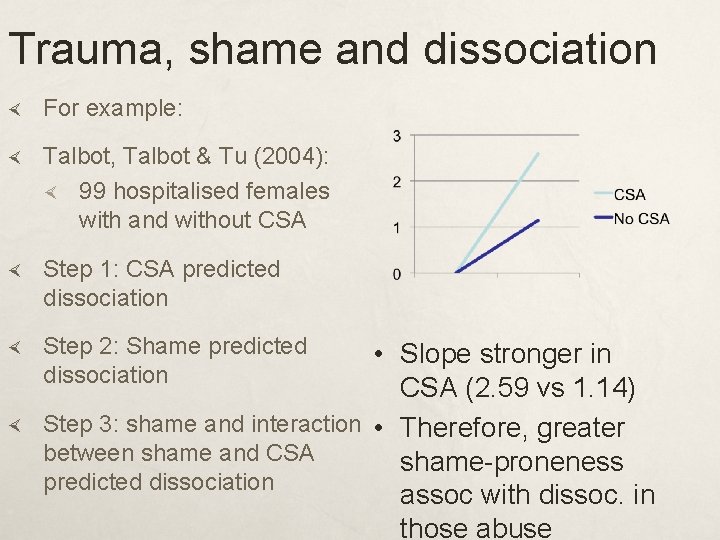

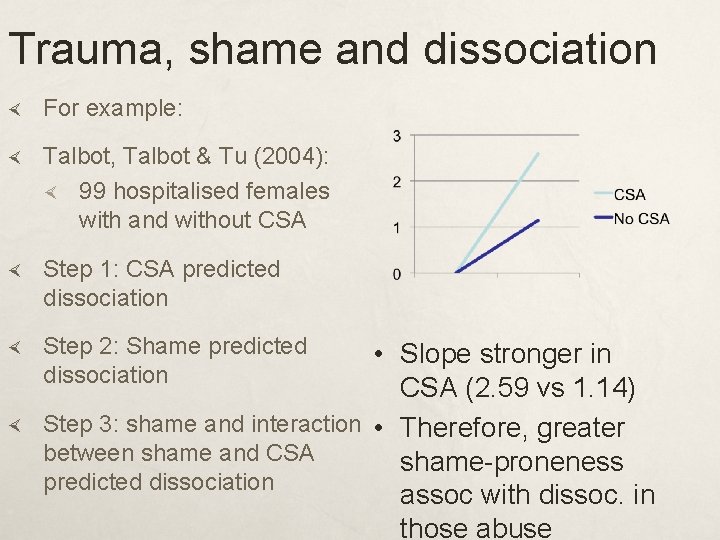

Trauma, shame and dissociation For example: Talbot, Talbot & Tu (2004): 99 hospitalised females with and without CSA Step 1: CSA predicted dissociation Step 2: Shame predicted dissociation • Slope stronger in CSA (2. 59 vs 1. 14) Step 3: shame and interaction • Therefore, greater between shame and CSA shame-proneness predicted dissociation assoc with dissoc. in those abuse

Shame, Trauma and Dissociation Thomson & Jaque (2013) 140 pre-prof. & prof dancers 99 athletes (trained 5+years, compete) DES, Internal Shame Scale, Trauma. Ex. Q. Dancers higher shame and path. Dissociation than athletes

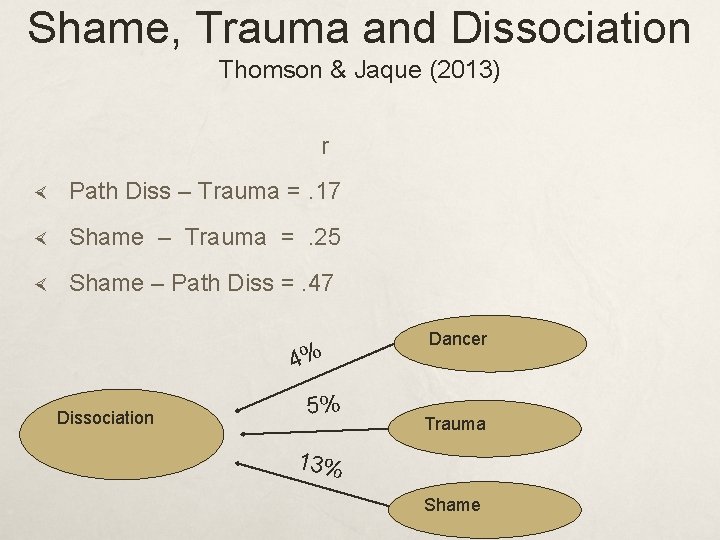

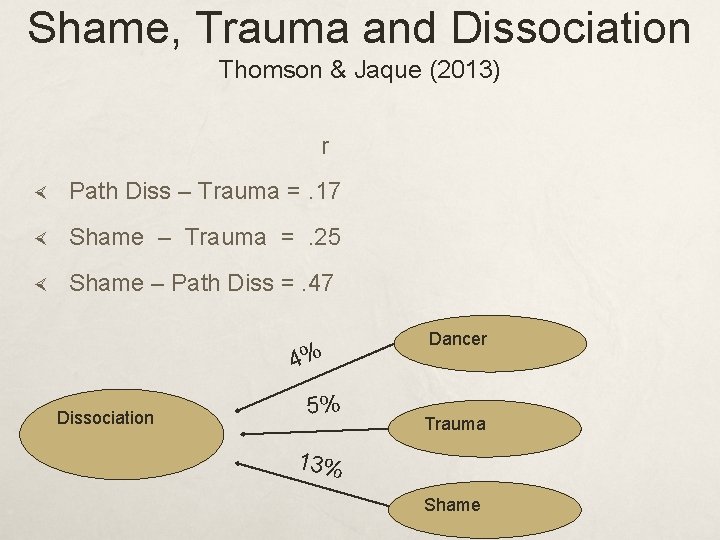

Shame, Trauma and Dissociation Thomson & Jaque (2013) r Path Diss – Trauma =. 17 Shame – Trauma =. 25 Shame – Path Diss =. 47 4% Dissociation 5% Dancer Trauma 13% Shame

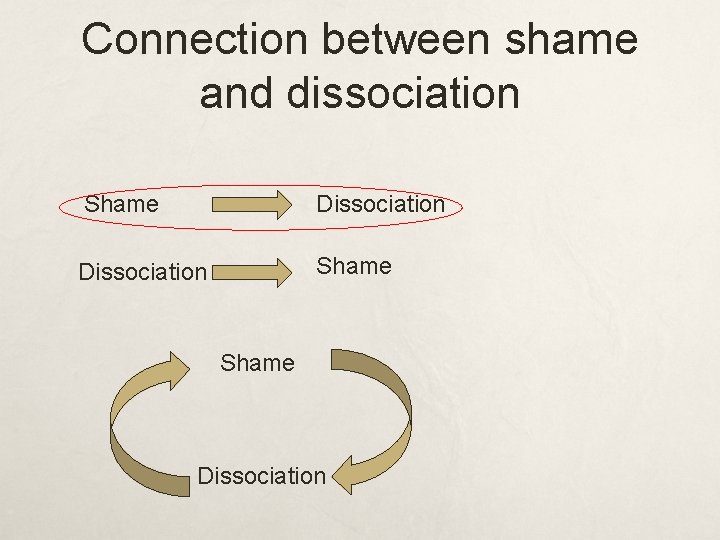

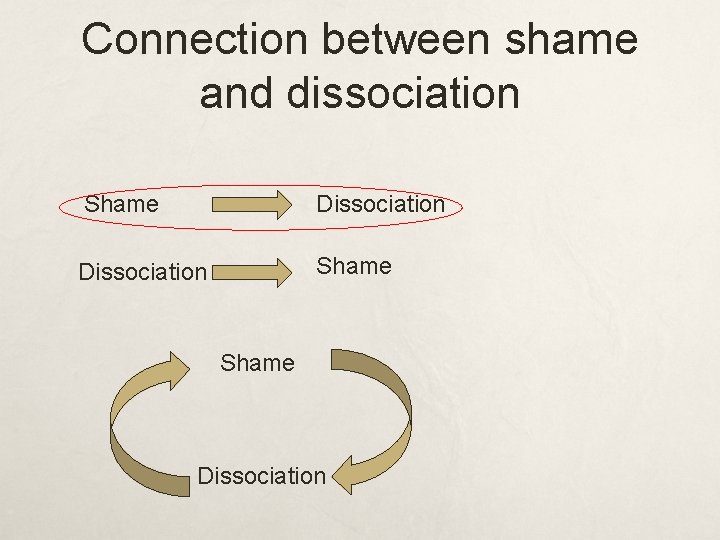

Connection between shame and dissociation Shame Dissociation

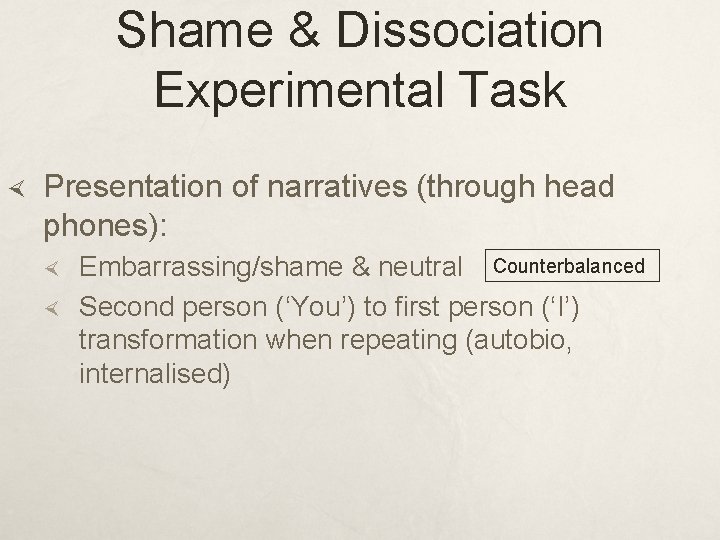

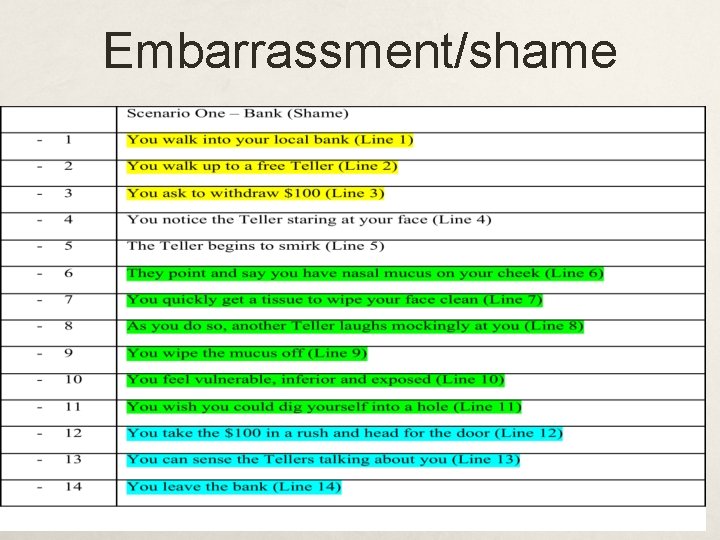

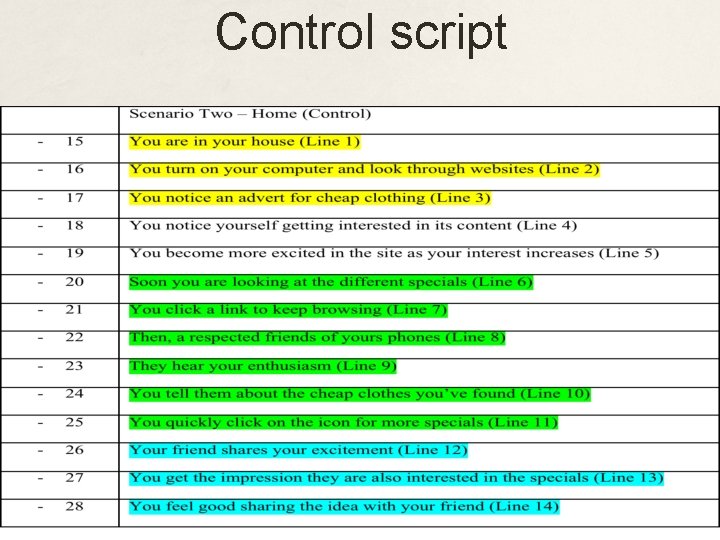

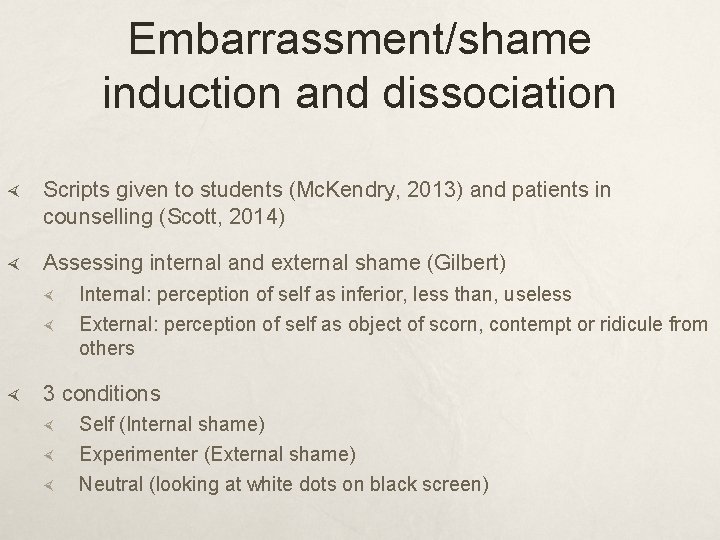

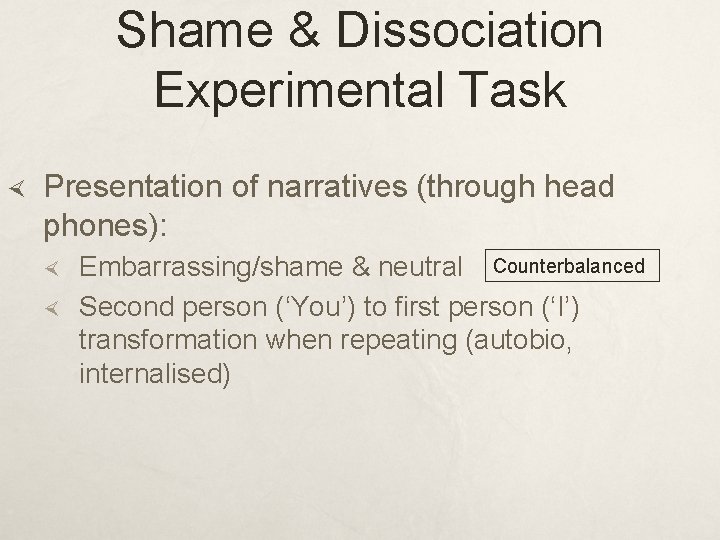

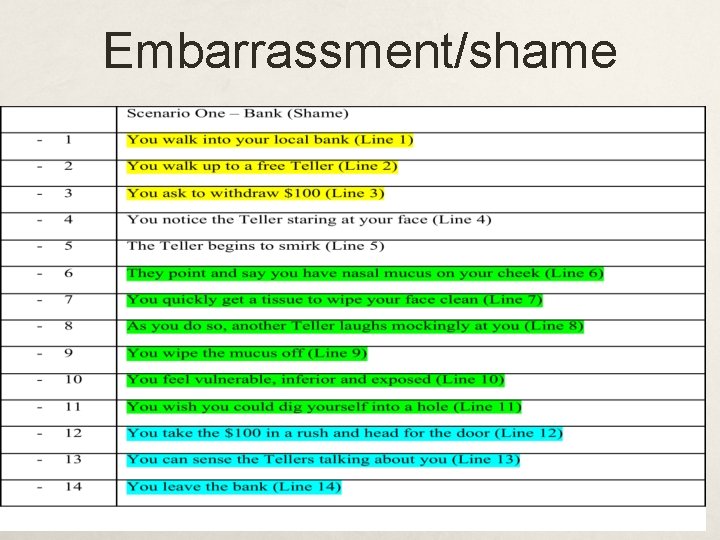

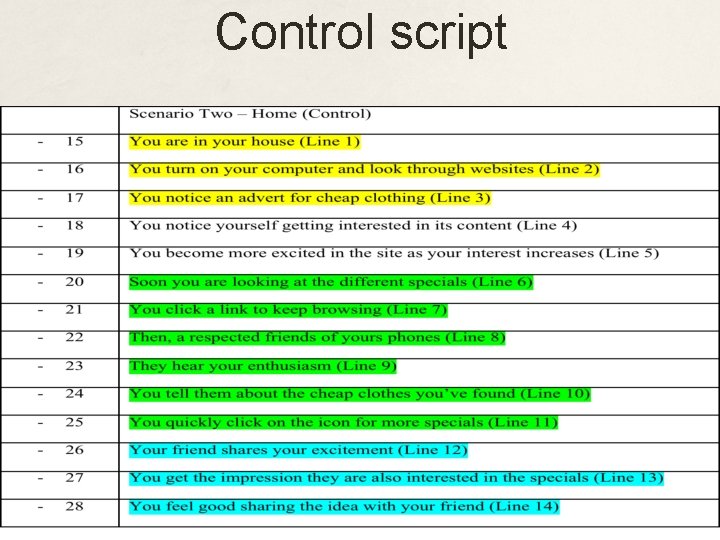

Shame & Dissociation Experimental Task Presentation of narratives (through head phones): Embarrassing/shame & neutral Counterbalanced Second person (‘You’) to first person (‘I’) transformation when repeating (autobio, internalised)

Embarrassment/shame

Control script

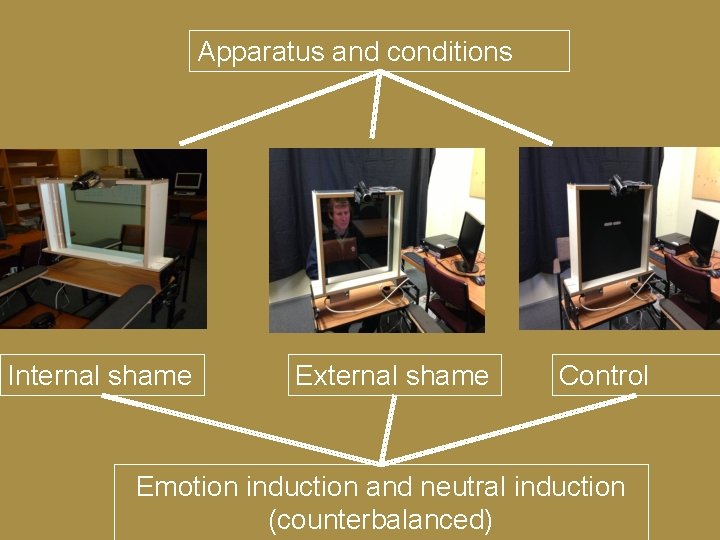

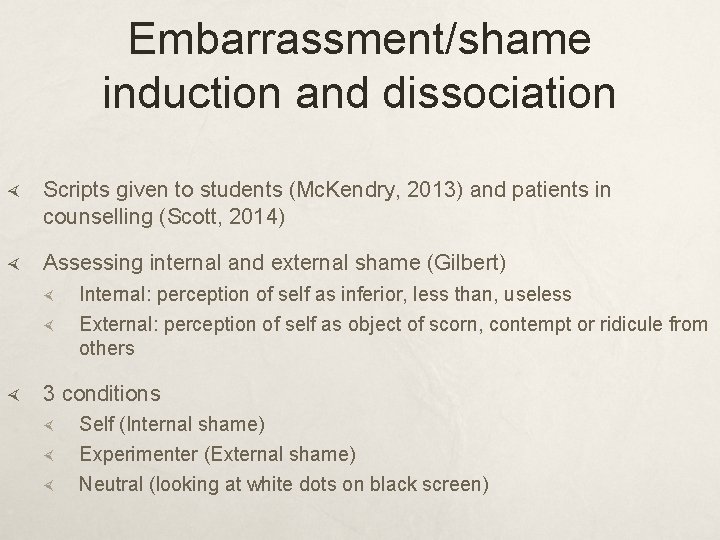

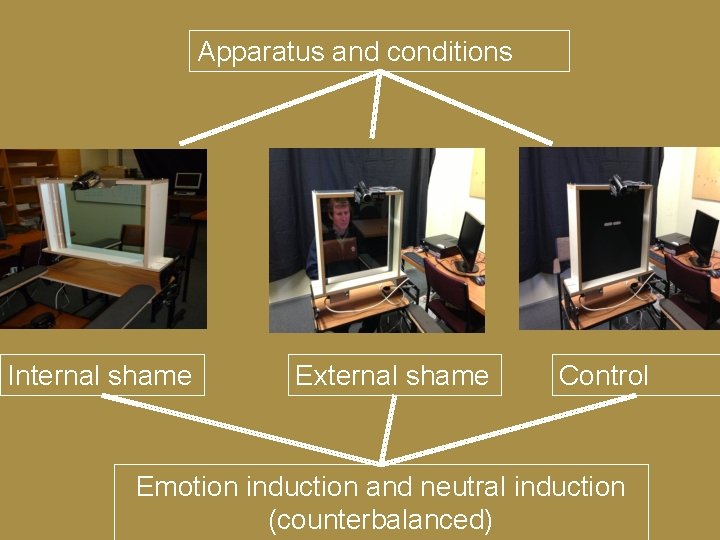

Embarrassment/shame induction and dissociation Scripts given to students (Mc. Kendry, 2013) and patients in counselling (Scott, 2014) Assessing internal and external shame (Gilbert) Internal: perception of self as inferior, less than, useless External: perception of self as object of scorn, contempt or ridicule from others 3 conditions Self (Internal shame) Experimenter (External shame) Neutral (looking at white dots on black screen)

Apparatus and conditions Internal shame External shame Control Emotion induction and neutral induction (counterbalanced)

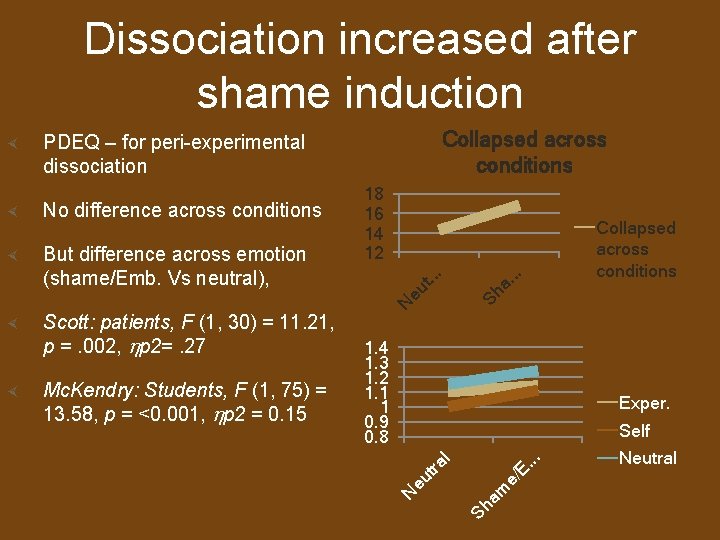

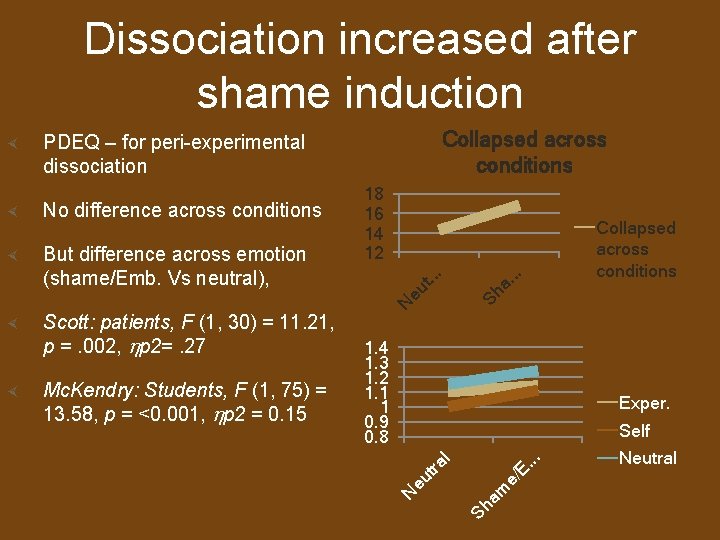

Dissociation increased after shame induction Collapsed across conditions PDEQ – for peri-experimental dissociation . . a. Exper. tra l E. . . Self eu Mc. Kendry: Students, F (1, 75) = 13. 58, p = <0. 001, p 2 = 0. 15 N 1. 4 1. 3 1. 2 1. 1 1 0. 9 0. 8 e/ Scott: patients, F (1, 30) = 11. 21, p =. 002, p 2=. 27 Collapsed across conditions Sh Sh am But difference across emotion (shame/Emb. Vs neutral), . t. . No difference across conditions N 18 16 14 12 eu Neutral

discussion Dissociation is not related to specific kind on shame/embarrassment-inducing context. Rather, it seems to operate with a general increase in shame/embarrassment, regardless of whether one is in the company of others or not.

Shame, dissociation and relationship functioning Does shame and dissociation relate to relationship functioning in traumatised groups?

Shame, dissociation and relationship functioning Shame has a long tradition of being associated with relationship difficulties. Shame impedes social connection (‘severs interpersonal connection’ – Kluft, 2007) Intimacy fears are especially high in shame-prone individuals and they may avoid relationships fearing rejection from others (e. g. , Schimmenti, 2012) Dissociation, less investigation (Lyons-Ruth, 2003, 2008)

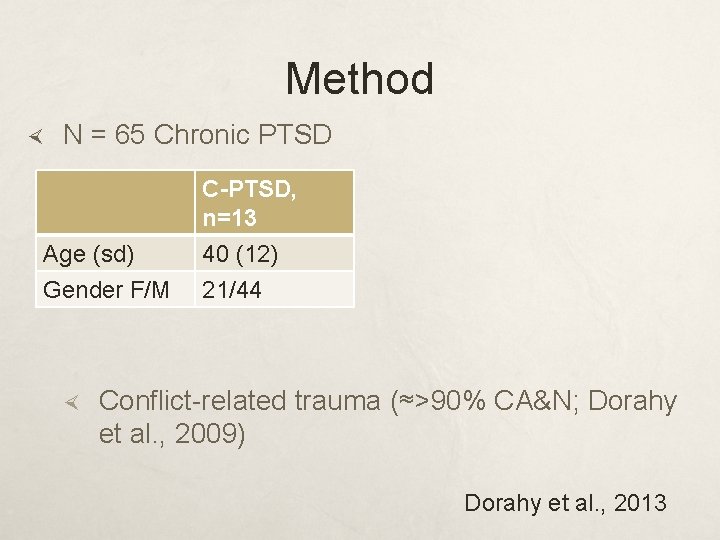

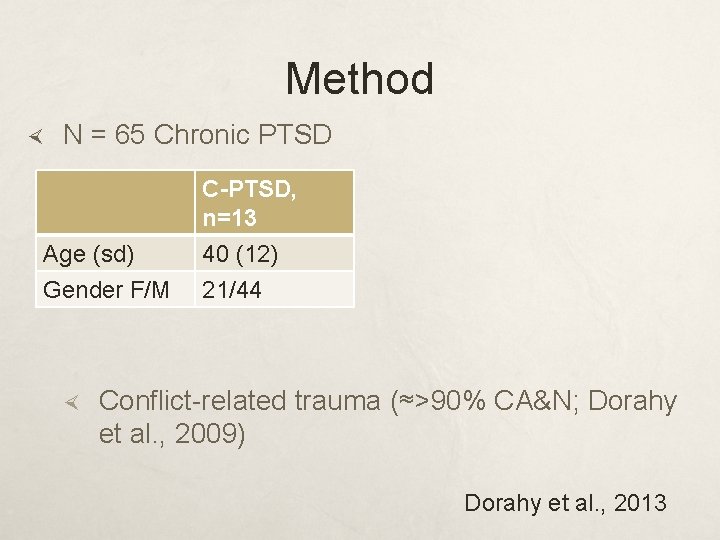

Method N = 65 Chronic PTSD C-PTSD, n=13 Age (sd) 40 (12) Gender F/M 21/44 Conflict-related trauma (≈>90% CA&N; Dorahy et al. , 2009) Dorahy et al. , 2013

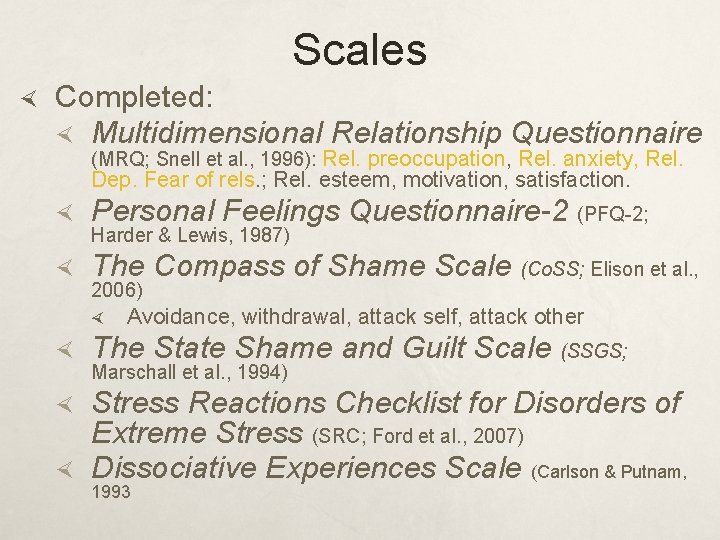

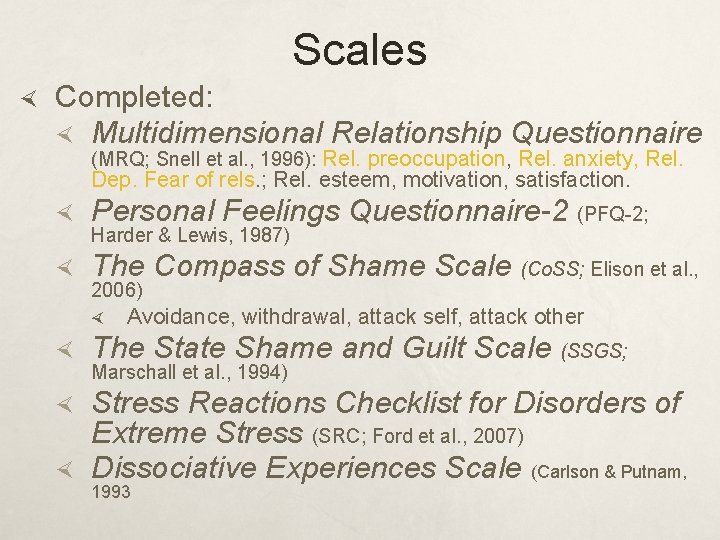

Scales Completed: Multidimensional Relationship Questionnaire (MRQ; Snell et al. , 1996): Rel. preoccupation, Rel. anxiety, Rel. Dep. Fear of rels. ; Rel. esteem, motivation, satisfaction. Personal Feelings Questionnaire-2 (PFQ-2; The Compass of Shame Scale (Co. SS; Elison et al. , Harder & Lewis, 1987) 2006) Avoidance, withdrawal, attack self, attack other The State Shame and Guilt Scale (SSGS; Stress Reactions Checklist for Disorders of Extreme Stress (SRC; Ford et al. , 2007) Dissociative Experiences Scale (Carlson & Putnam, Marschall et al. , 1994) 1993

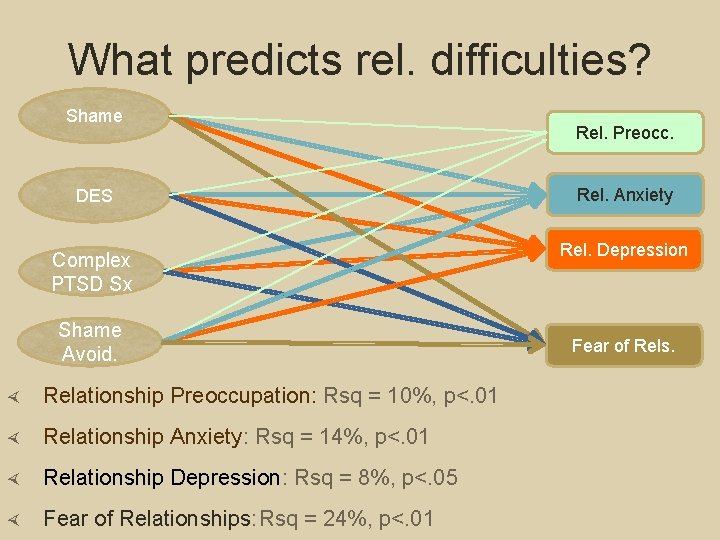

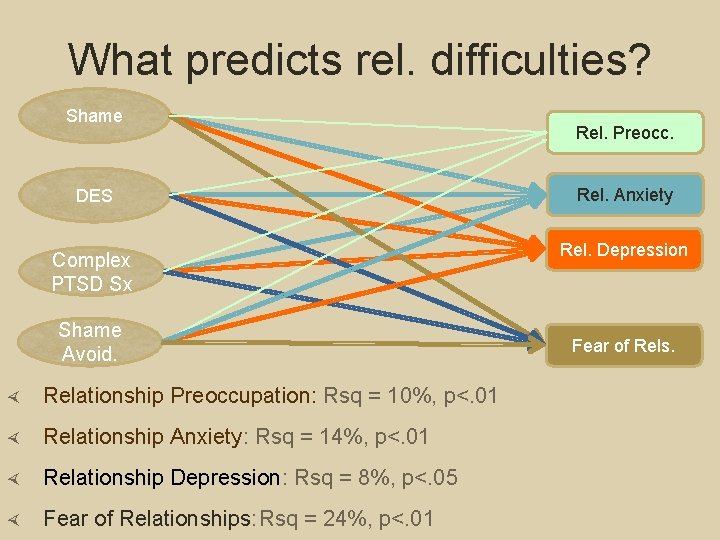

What predicts rel. difficulties? Shame DES Complex PTSD Sx Shame Avoid. Relationship Preoccupation: Rsq = 10%, p<. 01 Relationship Anxiety: Rsq = 14%, p<. 01 Relationship Depression: Rsq = 8%, p<. 05 Fear of Relationships: Rsq = 24%, p<. 01 Rel. Preocc. Rel. Anxiety Rel. Depression Fear of Rels.

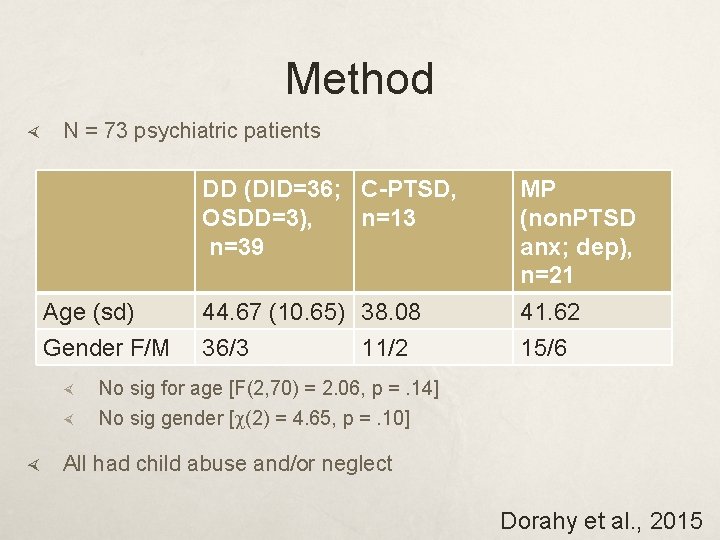

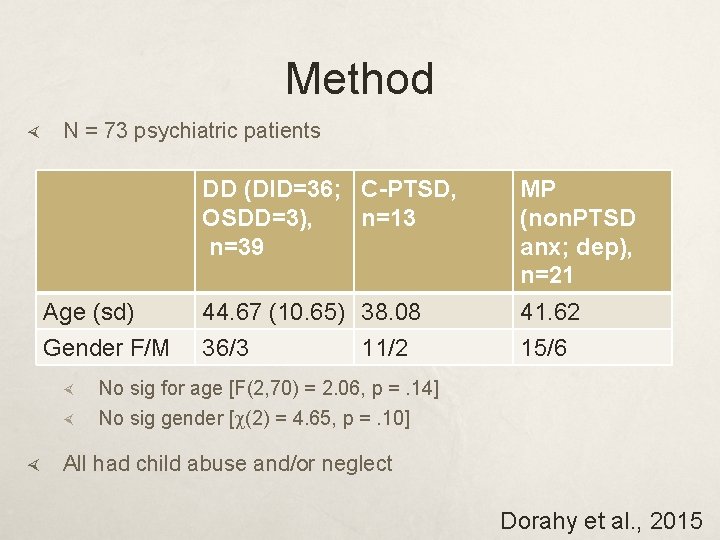

Method N = 73 psychiatric patients DD (DID=36; C-PTSD, OSDD=3), n=13 n=39 MP (non. PTSD anx; dep), n=21 Age (sd) 44. 67 (10. 65) 38. 08 41. 62 Gender F/M 36/3 15/6 11/2 No sig for age [F(2, 70) = 2. 06, p =. 14] No sig gender [ (2) = 4. 65, p =. 10] All had child abuse and/or neglect Dorahy et al. , 2015

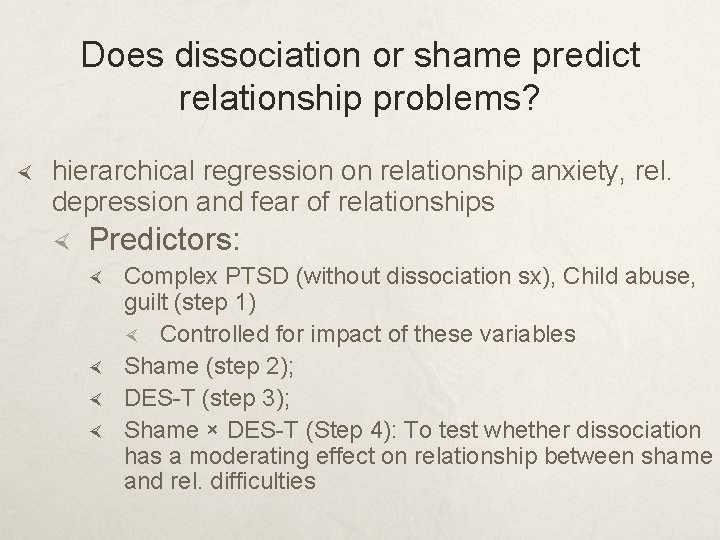

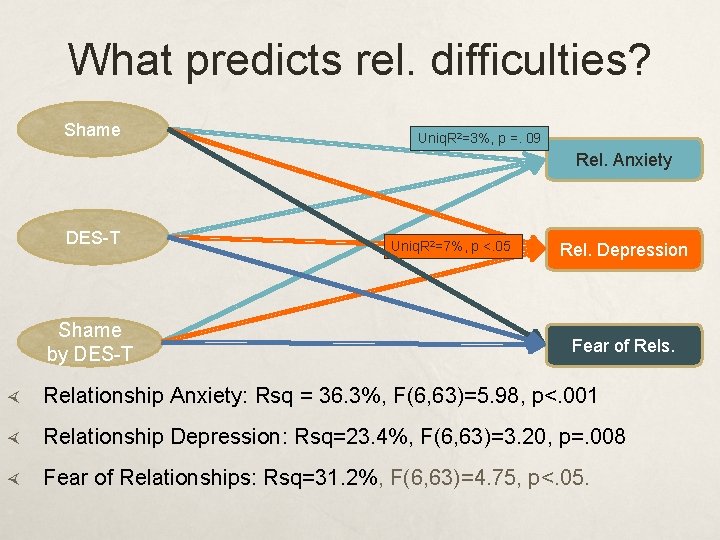

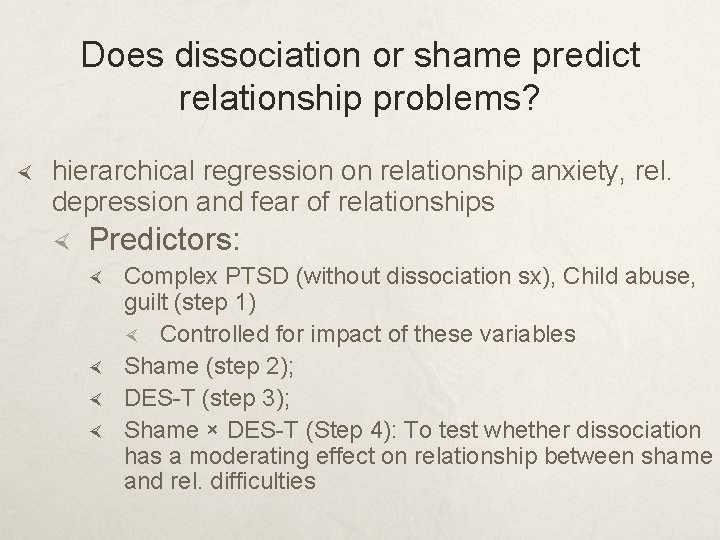

Does dissociation or shame predict relationship problems? hierarchical regression on relationship anxiety, rel. depression and fear of relationships Predictors: Complex PTSD (without dissociation sx), Child abuse, guilt (step 1) Controlled for impact of these variables Shame (step 2); DES-T (step 3); Shame × DES-T (Step 4): To test whether dissociation has a moderating effect on relationship between shame and rel. difficulties

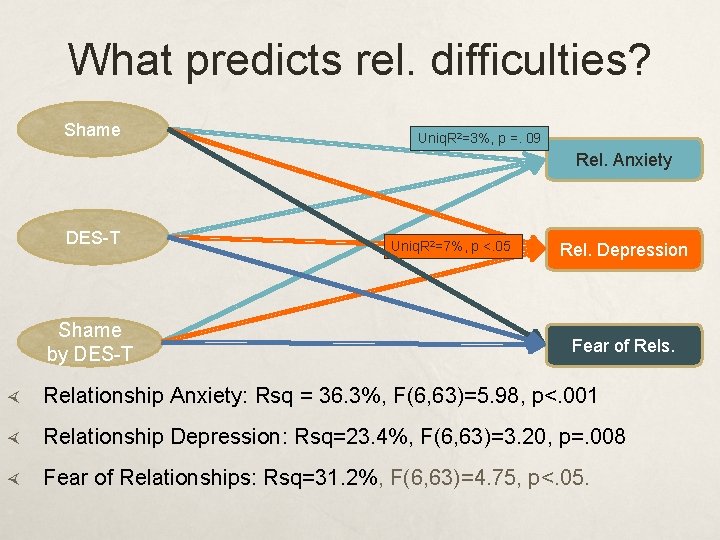

What predicts rel. difficulties? Shame Uniq. R 2=3%, p =. 09 Rel. Anxiety DES-T Shame by DES-T Uniq. R 2=7%, p <. 05 Rel. Depression Fear of Rels. Relationship Anxiety: Rsq = 36. 3%, F(6, 63)=5. 98, p<. 001 Relationship Depression: Rsq=23. 4%, F(6, 63)=3. 20, p=. 008 Fear of Relationships: Rsq=31. 2%, F(6, 63)=4. 75, p<. 05.

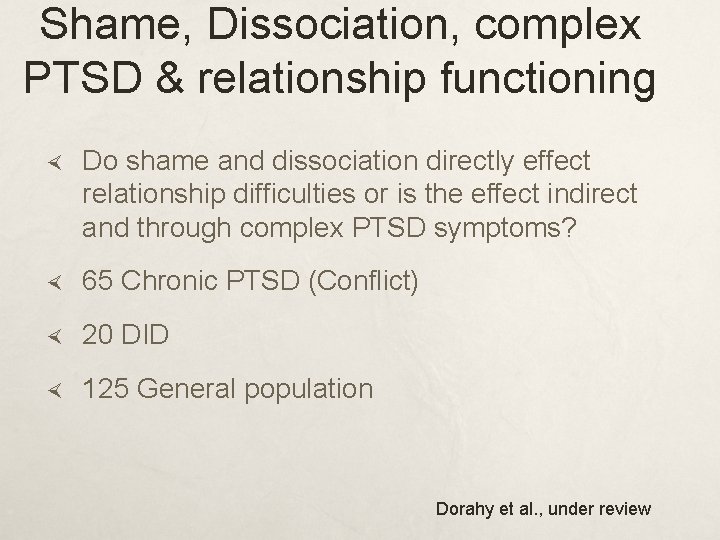

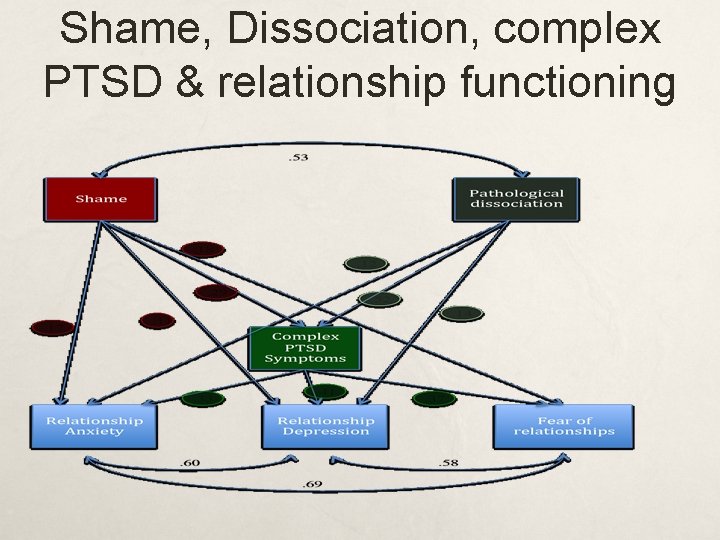

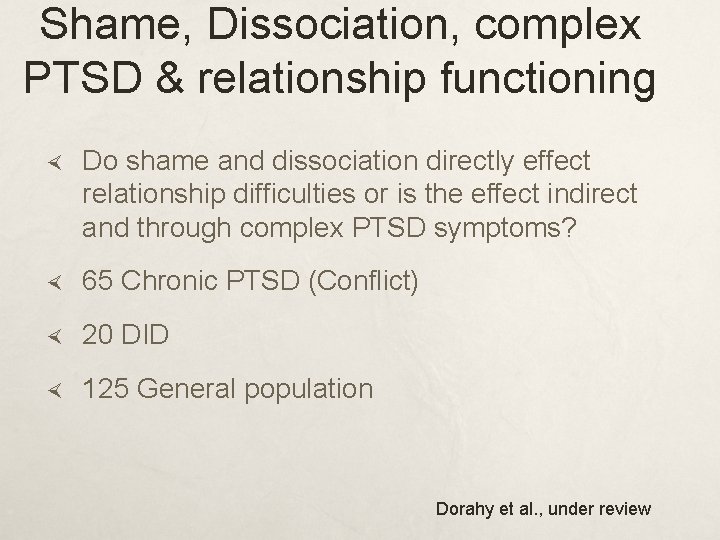

Shame, Dissociation, complex PTSD & relationship functioning Do shame and dissociation directly effect relationship difficulties or is the effect indirect and through complex PTSD symptoms? 65 Chronic PTSD (Conflict) 20 DID 125 General population Dorahy et al. , under review

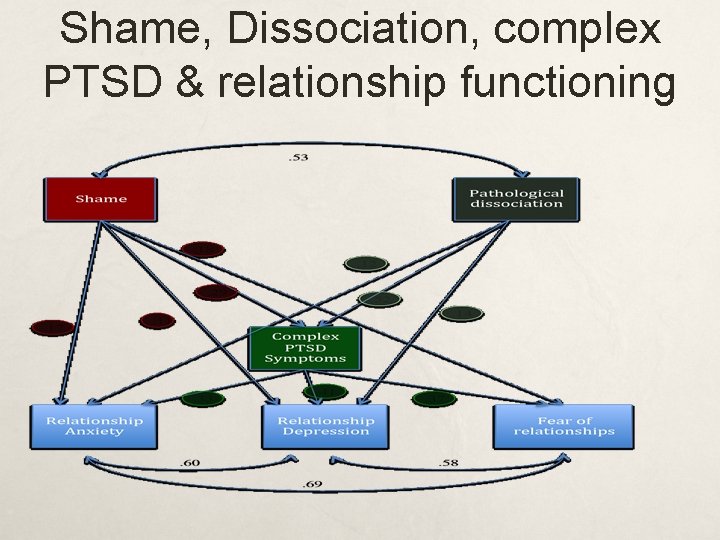

Shame, Dissociation, complex PTSD & relationship functioning

Implications Treating shame and dissociation is likely to reduce: Complex PTSD symptoms Relationship anxiety Relationship depression Fear of Relationships

Therapy

Shame is only occasionally felt but constantly anticipated Scheff, 2003

Why focus on shame in traumatised clients? “Overwhelming feelings of shame may contribute to early treatment drop-out or indeed may be the reason why some individuals never present for treatment in spite of suffering from debilitating symptoms of PTSD” (Lee et al. , 2001, p. 464) Has implications for all stages of treatment (Herman, 2011)

Shame in therapy In therapy, unaddressed shame is detrimental to: The therapeutic process The client-therapist interaction Hahn, 2004; Kluft, 2007; Retzinger, 1998

Shame in therapy Shame needs to be considered early and worked with patiently Given covert nature of shame assume it’s presence and allow yourself in the service of the clients to actively enquire about it. Anticipate resistance and reluctance

Three levels shame can be examined in therapy Intrapersonal shame Interpersonal shame at intimate level Examination changes in self-concept e. g. , Changes in personal relationships Occupational and societal level E. g. , loss, isolation, and exclusion. Taylor, 2015

Identifying shame themes/scripts The clients story involves description of self as feeling “small”, “humiliated”, “weak”, “inferior”, “worthless”, “less than human” or “non-existent”, ‘dumb’, ‘idiotic’ (Herman, 2011). Client may judge self in the story as pathetic or despicable (Cloitre et al. , 2006, p. 288) Often evoke strong responses in therapist: e. g. , powerlessness, the desire to reassure, the desire to defend by e. g. , feeling rage at perpetrator; or desire to stop feelings-e. g. , rage at client or emotional/attentional withdrawal CT can identify & help understand shame & rage - e. g. , concordant CT (e. g. , powerlessness), complimentary CT (attack client mentally, withdraw) See Chefetz, 2015

Even the term ‘shame’ can be too much Naming shame is important (Lewis, 1971). But, in some cases using the word ‘shame’ can be too strong. Thus start with ‘mortified’, ‘embarrassed’, ‘lowest of the low’ Herman, 2011

What is the best initial intervention In a study of preferred interventions to highlyshame-inducing therapy stimuli (n = 55) Shame and surprised narratives by ‘clients’ Dorahy et al. , 2015

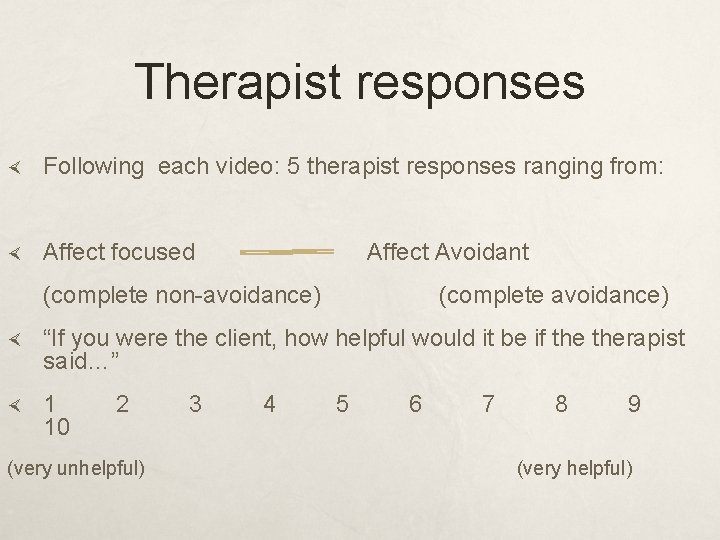

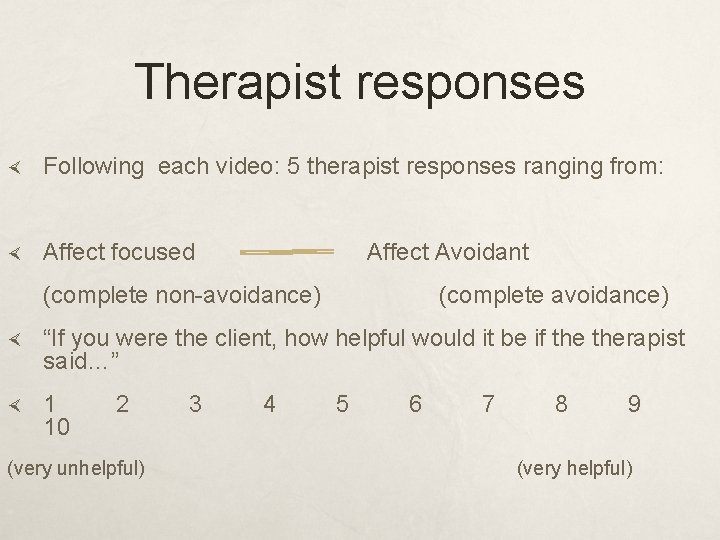

Therapist responses Following each video: 5 therapist responses ranging from: Affect focused Affect Avoidant (complete non-avoidance) (complete avoidance) “If you were the client, how helpful would it be if therapist said…” 1 10 2 (very unhelpful) 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 (very helpful)

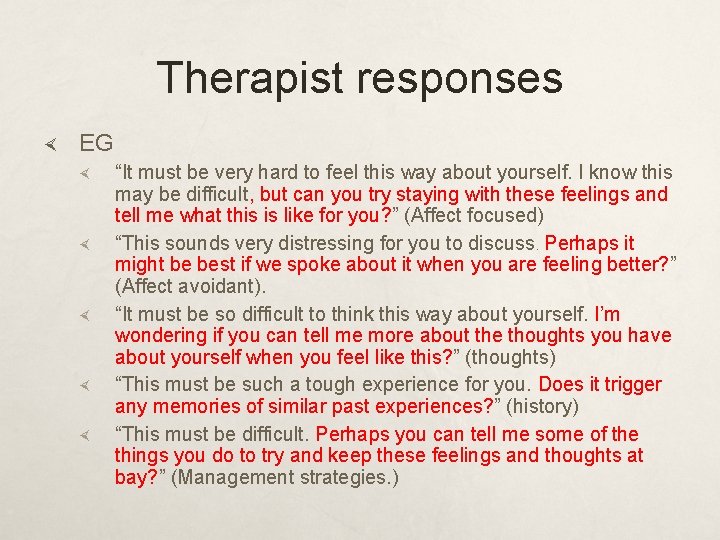

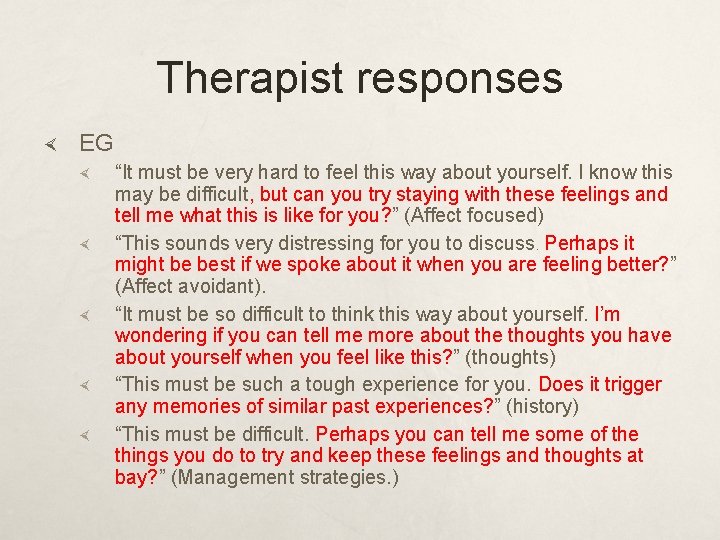

Therapist responses EG “It must be very hard to feel this way about yourself. I know this may be difficult, but can you try staying with these feelings and tell me what this is like for you? ” (Affect focused) “This sounds very distressing for you to discuss. Perhaps it might be best if we spoke about it when you are feeling better? ” (Affect avoidant). “It must be so difficult to think this way about yourself. I’m wondering if you can tell me more about the thoughts you have about yourself when you feel like this? ” (thoughts) “This must be such a tough experience for you. Does it trigger any memories of similar past experiences? ” (history) “This must be difficult. Perhaps you can tell me some of the things you do to try and keep these feelings and thoughts at bay? ” (Management strategies. )

Summary of results High shame-prone participants deemed unhelpful: Avoidance interventions (e. g. , ‘talking about it later) Direct experience interventions (e. g. , experience feeling). Interventions in the ‘middle’ that touched on management (i. e. , how do you manage these feelings’) was deemed best.

Shame often ignored in therapy Shame is often ignored in therapy. Not simply because of the pain it causes in the patient, But also the pain (and strategies to avoid it) it causes in therapist. The recognition of shame is itself is often considered shaming Lewis, 1971; Taylor, 2015; Wilson, 2006

“When shame is accepted and examined inside the consulting room, this becomes for the patient a crucial opportunity to repair his or her self-image and to restore a sense of a connected self” Schimmenti, 2012, p. 207)

Furtherapy readings Chefetz, R. A. (2015). Intensive psychotherapy for persistent dissociative processes: The fear of feeling real. New York: Norton Gilbert, P. (1998 b). Shame and humiliation in the treatment of complex case. In N. Tarrier, A. Wells & G. Haddock (Eds. ), Treating complex cases: The cognitive behavioural therapy approach (pp. 241 -271). Chichester: Wiley & Sons. Kluft, R. P. (2007). Application of innate affect theory to the understanding and treatment of dissociative identity disorder. In E. Vermetten, M. J. Dorahy and D. Spiegel (Eds. ), Traumatic dissociation: Neurobiology and treatment (pp. 301316). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Press. Lee, D. A. , Scragg, P. , & Turner, S. (2001). The role of shame and guilt in traumatic events: A clinical model of shame-based and guilt-based PTSD. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 74, 451 -466. Stewart, B. L. , Dadson, M. R. , & Fallding, M. J. (2011). The application of attachment theory and mentalization in complex tertiary structural dissociation: A case study. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 20, 322– 343.