Shakespeares London 9 Strangers Jane Stevenson Campion Hall

- Slides: 44

Shakespeare’s London 9: Strangers Jane Stevenson Campion Hall

Urban growth London’s population quadrupled from around 50, 000 people in 1500 to 200, 000 in 1600. London grew to be a great city on the basis of immigration. Vast numbers were needed to fuel the city's growth in early modern times because deaths outnumbered births by about 2, 000 a year, from 1560 to 1625. London's growth between those dates required an influx of about 5, 600 people every year. Immigration on this scale would cause problems in a modern city of similar size. In the London of I 600 the difficulties were enormous. Westminster was the scene of incredible poverty. The records of St. Margaret's parish overseers and of the Court of Burgesses show people living, having children, and dying in the streets and in cellars. In his Survey of London, John Stow described slums springing up in Southwark, Whitechapel and Houndsditch.

. . . it would seem probable that London in 1500 did not number more than about 1. 5 per cent of the whole population. But by 1600 the city very probably included slightly more than 5 per cent of the inhabitants of the kingdom and, most pertinently, controlled nearly 80 per cent of its foreign trade. London’s expansion ‘was ill understood in the late sixteenth century and was truly frightening to the responsible authorities’. It continued as ‘hordes of men poured in to the metropolis to fill its ranks and. . . the population continued to rise at a rate which suggests that London can best be described as a ‘boom town’.

Foreign contaminants? The area round St Paul’s Cathedral, in the heart of the City of London, was described by John Earle as ‘the whole world’s map … with a vast confusion of languages … nothing liker Babel. ’ ‘…we have derived to ourselves, with our commerce with foreign Nations, with their wares and commodities, their vices and eveill conditions; as our drunkenness and rudeness from the Germans, our fashions and factions from the French, our insolence from the Spaniards, our Machiavelianism from the Italians, our levity and inconstancy from the Greeks, our usury and extortion from the Jew, our atheism and impiety from the Turks and Moors, and our voluptuousness and luxury from the Persians and Indians. ’ Walter Hamond, A Paradox, London, 1640, f. 2 r

Exotic creatures in St James’s Park, 1615 https: //www. bl. uk/collection-items/a-virginian-indian-in-st-jamesspark-from-the-friendship-album-of-michael-van-meer

English appetite for seeing exotic people Were I in England now, as once I was, and had but this fish painted, not a holiday fool there but would give a piece of silver: there would this monster make a man; any strange beast there makes a man: when they will not give a doit to relieve a lame beggar, they will lazy out ten to see a dead Indian. The Tempest, Act II, sc. 1

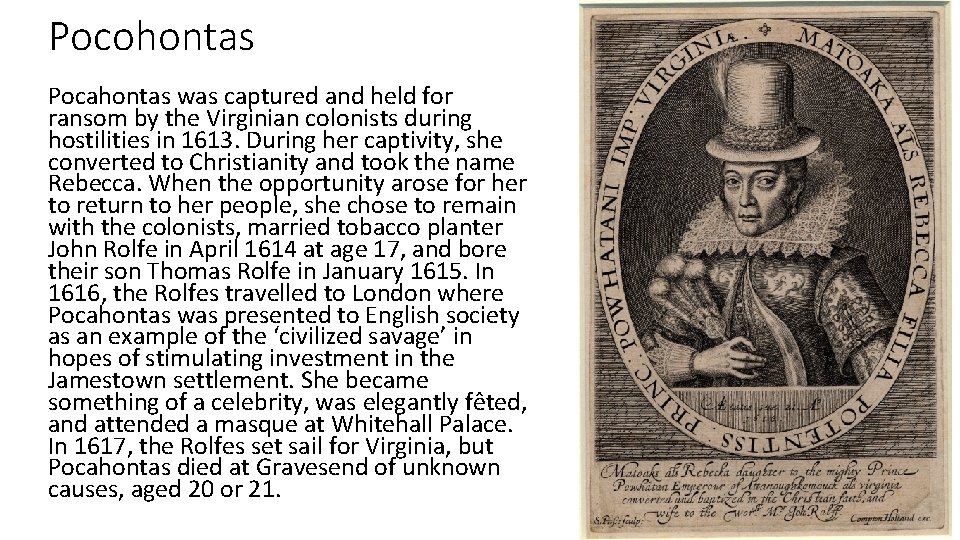

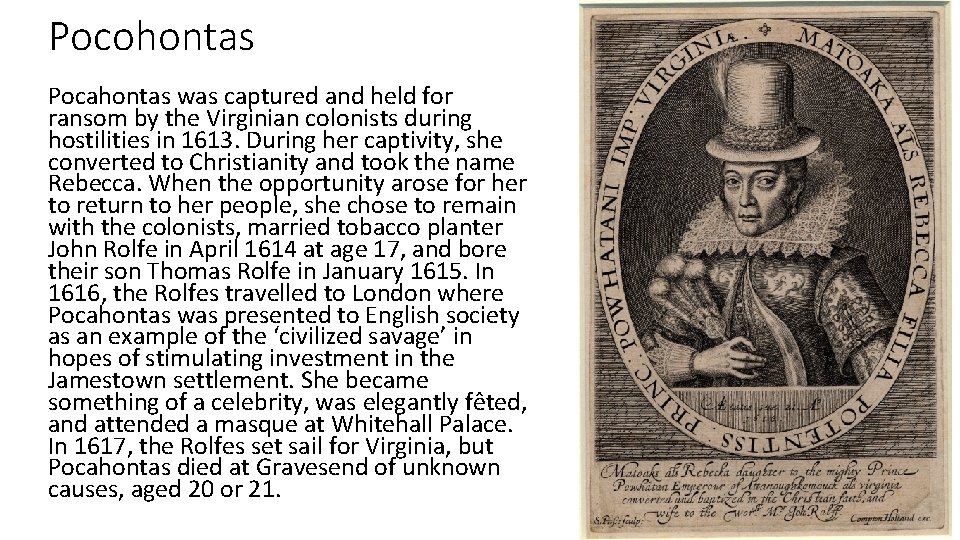

Pocohontas Pocahontas was captured and held for ransom by the Virginian colonists during hostilities in 1613. During her captivity, she converted to Christianity and took the name Rebecca. When the opportunity arose for her to return to her people, she chose to remain with the colonists, married tobacco planter John Rolfe in April 1614 at age 17, and bore their son Thomas Rolfe in January 1615. In 1616, the Rolfes travelled to London where Pocahontas was presented to English society as an example of the ‘civilized savage’ in hopes of stimulating investment in the Jamestown settlement. She became something of a celebrity, was elegantly fêted, and attended a masque at Whitehall Palace. In 1617, the Rolfes set sail for Virginia, but Pocahontas died at Gravesend of unknown causes, aged 20 or 21.

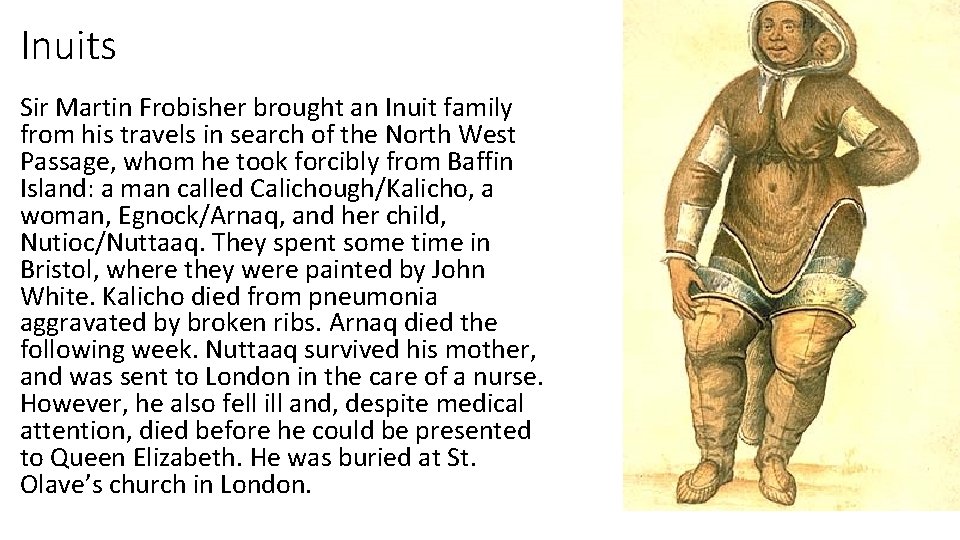

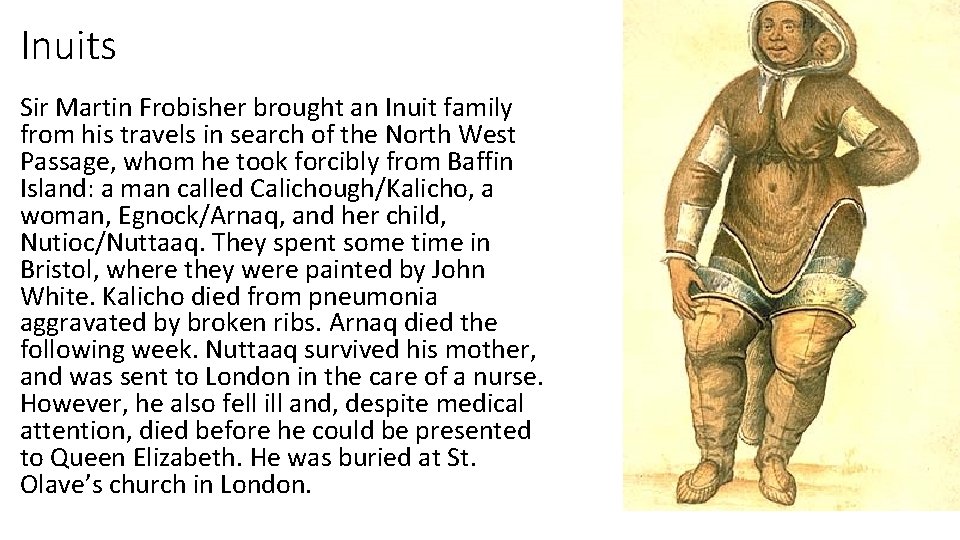

Inuits Sir Martin Frobisher brought an Inuit family from his travels in search of the North West Passage, whom he took forcibly from Baffin Island: a man called Calichough/Kalicho, a woman, Egnock/Arnaq, and her child, Nutioc/Nuttaaq. They spent some time in Bristol, where they were painted by John White. Kalicho died from pneumonia aggravated by broken ribs. Arnaq died the following week. Nuttaaq survived his mother, and was sent to London in the care of a nurse. However, he also fell ill and, despite medical attention, died before he could be presented to Queen Elizabeth. He was buried at St. Olave’s church in London.

‘Coree’ (Xhore), a Khoikhoi chief Taken against his will from Table Bay, then called Saldania, in South Africa, where English ships put in for rest and recuperation, in 1612: ‘He had good diet, good cloaths, good lodging and all other fitting accommodations … yet all this contented him not … he would daily lie upon the ground and cry very often thus in broken English “Coree home go, Saldania go, home go”. ’ He was allowed to return on the New Year’s Gift in 1614: ‘he had no sooner sett foot on his own shore but did presently throw away his cloaths, his linen and other covering and got his sheepskin upon his back. ’

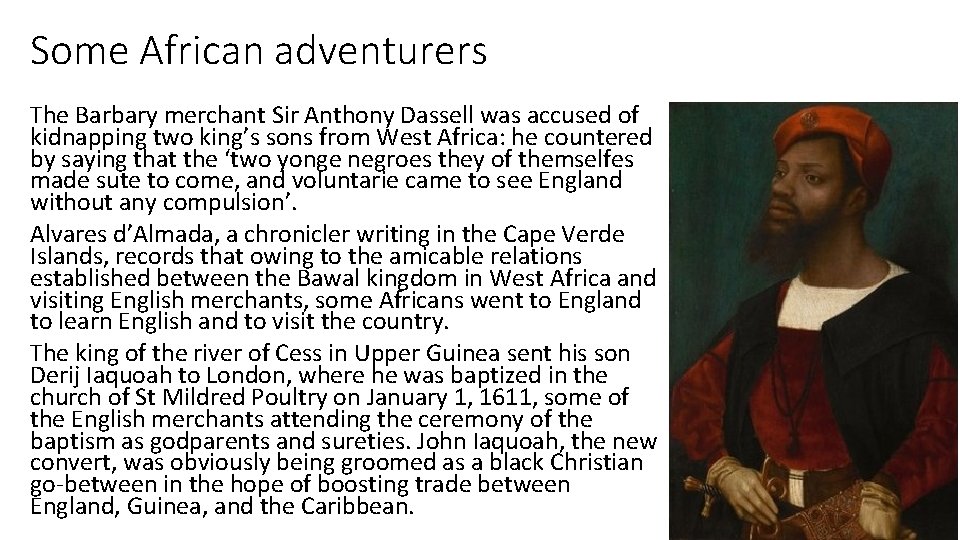

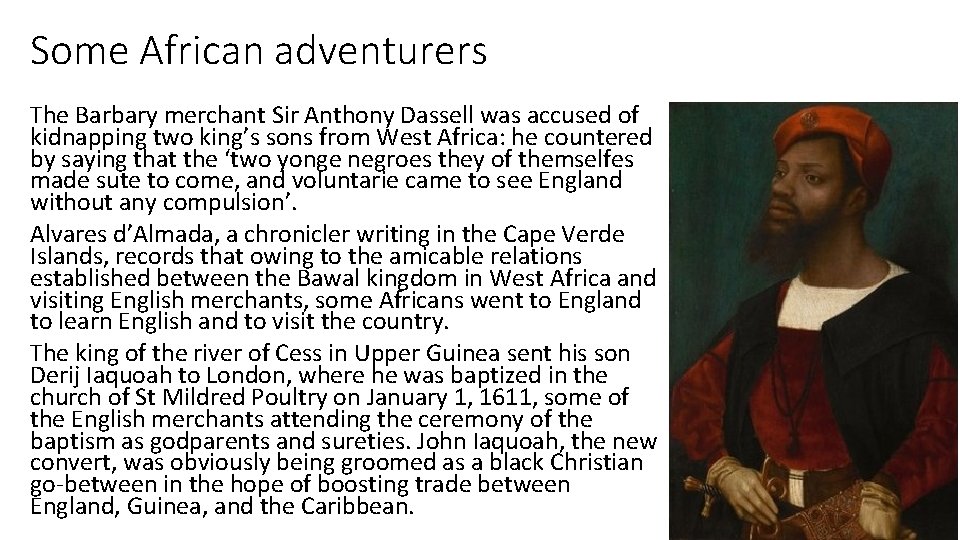

Some African adventurers The Barbary merchant Sir Anthony Dassell was accused of kidnapping two king’s sons from West Africa: he countered by saying that the ‘two yonge negroes they of themselfes made sute to come, and voluntarie came to see England without any compulsion’. Alvares d’Almada, a chronicler writing in the Cape Verde Islands, records that owing to the amicable relations established between the Bawal kingdom in West Africa and visiting English merchants, some Africans went to England to learn English and to visit the country. The king of the river of Cess in Upper Guinea sent his son Derij Iaquoah to London, where he was baptized in the church of St Mildred Poultry on January 1, 1611, some of the English merchants attending the ceremony of the baptism as godparents and sureties. John Iaquoah, the new convert, was obviously being groomed as a black Christian go-between in the hope of boosting trade between England, Guinea, and the Caribbean.

Black Londoners: John Blanke, 1520

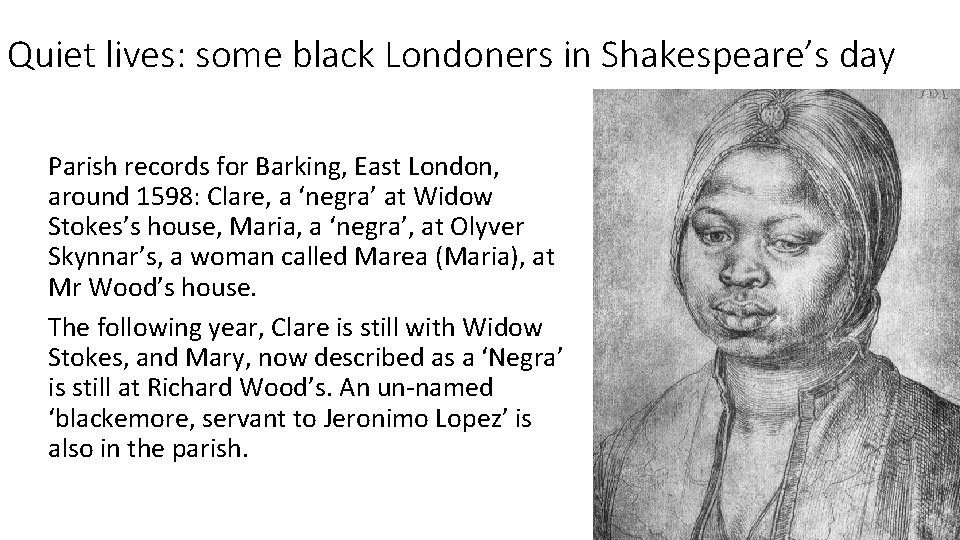

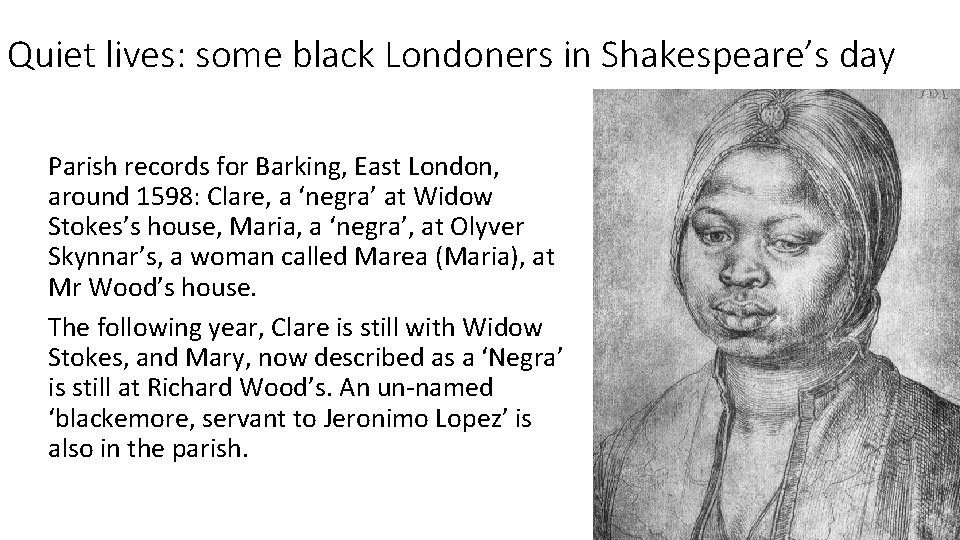

Quiet lives: some black Londoners in Shakespeare’s day Parish records for Barking, East London, around 1598: Clare, a ‘negra’ at Widow Stokes’s house, Maria, a ‘negra’, at Olyver Skynnar’s, a woman called Marea (Maria), at Mr Wood’s house. The following year, Clare is still with Widow Stokes, and Mary, now described as a ‘Negra’ is still at Richard Wood’s. An un-named ‘blackemore, servant to Jeronimo Lopez’ is also in the parish.

Draft proclamation on the expulsion of 'Negroes and Blackamoors', 1601 ‘WHEREAS the Queen’s majesty, tendering the good and welfare of her own natural subjects, greatly distressed in these hard times of dearth, is highly discontented to understand the great number of Negroes and blackamoors which (as she is informed) are carried into this realm since the troubles between her highness and the King of Spain; who are fostered and powered here, to the great annoyance of her own liege people that which co[vet? ] the relief which these people consume, as also for that the most of them are infidels having no understanding of Christ or his Gospel…’

Refugees: Shakespeare asks, how would you feel? Imagine that you see the wretched strangers, Their babies at their backs, with their poor luggage, Plodding to th’ ports and coasts for transportation, And that you sit as kings in your desires, Authority quite silenced by your brawl. . . say now the King, As he is clement if th’offender mourn, Should so much come too short of your great trespass As but to banish you: whither would you go? What country, by the nature of your error, Should give you harbour? Go you to France or Flanders, To any German province, Spain or Portugal, Nay, anywhere that not adheres to England, Why, you must needs be strangers, would you be pleas’d To find a nation of such barbarous temper That breaking out in hideous violence Would not afford you an abode on earth. Whet their detested knives against your throats, Spurn you like dogs, and like as if that God Owed not nor made not you, not that the elements Were not all appropriate to your comforts, But charter’d unto them? What would you think To be us’d thus? This is the strangers’ case And this your mountainish inhumanity.

Hugenots: French Protestants Hugenots were French Calvinists, refugees from religious persecution in Catholic France. 1567: A company of the Walloons or Strangers, is allowed to inhabit within the liberties of the city [of Canterbury], by order from the queen's council, under the direction of the Burghmote. They are said to have come from Winchelsea (Records of the Burghmote) Acts of the Privy Council 20 February 1574 '…the Mayor of Canterbury and his brethren have convenient roume for receipt of straingers for a hundred families by Midsomer Daye … and desyrd to have regarde that they may not be of the meanest sort but choice to be made suche as makers of bayes, grograines …’ The great majority of Huguenots were town-dwellers; artisans, especially weavers, Those who came to Britain included many skilled craftsmen, silversmiths, watchmakers and the like, and professional people – clergy, doctors, merchants soldiers, teachers, There was a small sprinkling of the lesser nobility. Therefore some of them may indeed have been proud people.

Concern about competition: foreigners’ arrogance About this season (1517) there grew a great hartburning and malicious grudge amongst the Englishmen of the citie of London against strangers; and namelie the artificers found themselves sore grieved, for that such numbers of strangers were permitted to resort hither with their wares and to exercise handie crafts to the great hinderance and impoverishing of the kings liege people. Besides that, they set nought by the rulers of the citie, & bare themselves too bold of the kings favor, wherof they would insolentlie boast; vpon presumption therof, & they offred manie an iniurious abuse to his liege people, insomuch that among other accidents which were manifest, it fortuned that as a carpenter in London called Williamson had bought two stockdooves in Cheape, and was about to pay for them, a Frenchman tooke them out of his hand, and said they were not meate for a carpenter. (Holinshed, Chronicles, 1587)

French Hugenot church in London

Shakespeare and the Hugenots As becomes apparent from the records of a legal case in 1612, Shakespeare was living from 1602 to 1604 as a lodger with Christopher Mountjoy and his family in Silver Street in the respectable neighbourhood of Cripplegate. The case provides rare glimpses of Shakespeare's London life in 1602– 4 and in 1612. Mountjoy, a French Huguenot refugee, with his wife and daughter, was a successful tiremaker: i. e. , he made wigs and headdresses. Shakespeare might have met the Mountjoys through the French wife of the fellow. Stratfordian and printer Richard Field who lived nearby, but theatre companies always needed the services of wigmakers, so the Lord Chamberlain’s Men may have been the connection.

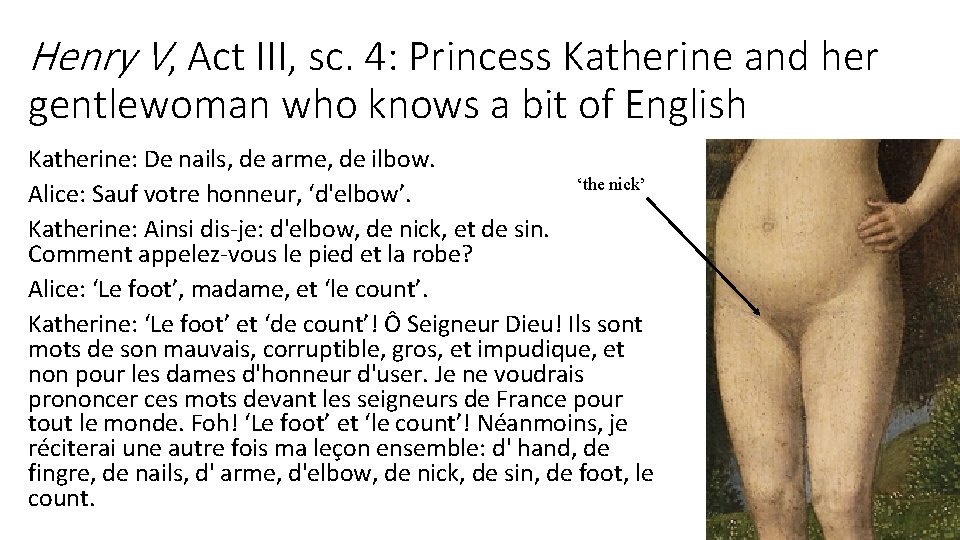

Henry V, Act III, sc. 4: Princess Katherine and her gentlewoman who knows a bit of English Katherine: De nails, de arme, de ilbow. ‘the nick’ Alice: Sauf votre honneur, ‘d'elbow’. Katherine: Ainsi dis-je: d'elbow, de nick, et de sin. Comment appelez-vous le pied et la robe? Alice: ‘Le foot’, madame, et ‘le count’. Katherine: ‘Le foot’ et ‘de count’! Ô Seigneur Dieu! Ils sont mots de son mauvais, corruptible, gros, et impudique, et non pour les dames d'honneur d'user. Je ne voudrais prononcer ces mots devant les seigneurs de France pour tout le monde. Foh! ‘Le foot’ et ‘le count’! Néanmoins, je réciterai une autre fois ma leçon ensemble: d' hand, de fingre, de nails, d' arme, d'elbow, de nick, de sin, de foot, le count.

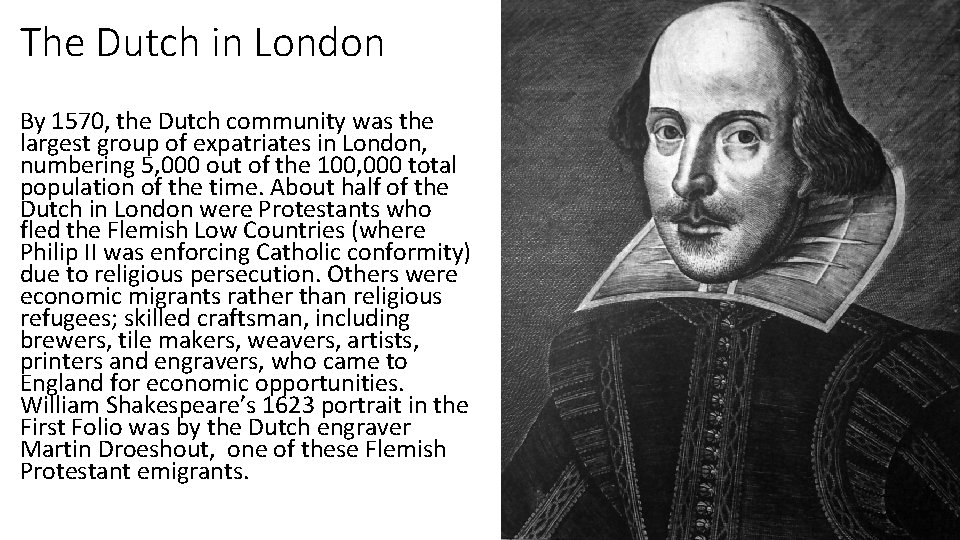

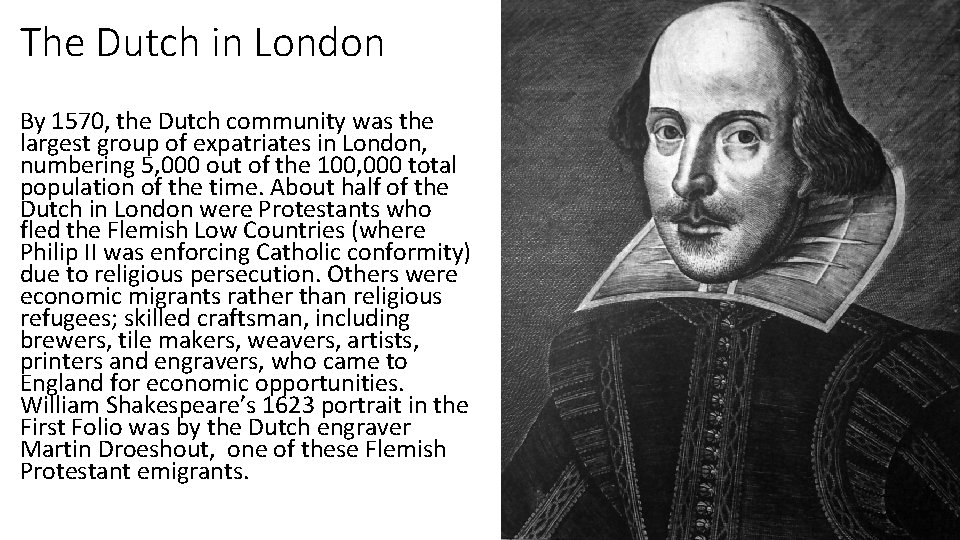

The Dutch in London By 1570, the Dutch community was the largest group of expatriates in London, numbering 5, 000 out of the 100, 000 total population of the time. About half of the Dutch in London were Protestants who fled the Flemish Low Countries (where Philip II was enforcing Catholic conformity) due to religious persecution. Others were economic migrants rather than religious refugees; skilled craftsman, including brewers, tile makers, weavers, artists, printers and engravers, who came to England for economic opportunities. William Shakespeare’s 1623 portrait in the First Folio was by the Dutch engraver Martin Droeshout, one of these Flemish Protestant emigrants.

Marcus Gheeraerts (c. 1561/62 -1636) A Flemish artist working at the Tudor court, the most important artist of quality to work in England in largescale between Hans Eworth and Anthony Van Dyck (both of whom were also Flemish). Gheeraerts’ father fled to England with his son to escape persecution in the Low Countries. His wife was a Catholic and remained behind: she is believed to have died a few years later. Father and son are recorded living with a Dutch servant in the London parish of St Mary Abchurch in 1568. On 9 September 1571, the elder Gheeraerts remarried. His new wife was Susanna de Critz, a member of an exiled family of painters from Antwerp. He became a fashionable portraitist in the last decade of the reign of Elizabeth I and was a favorite portraitist of James I’s queen, Anne of Denmark.

Tapestry (Easter altar frontal), 1573, made as a thank offering to St Peter’s Mancroft, Norwich, by refugee Flemish weavers

Dutch Calvinist church licensed by Edward VI: he hands the license to its first pastor, the Polish Protestant John à Lasco

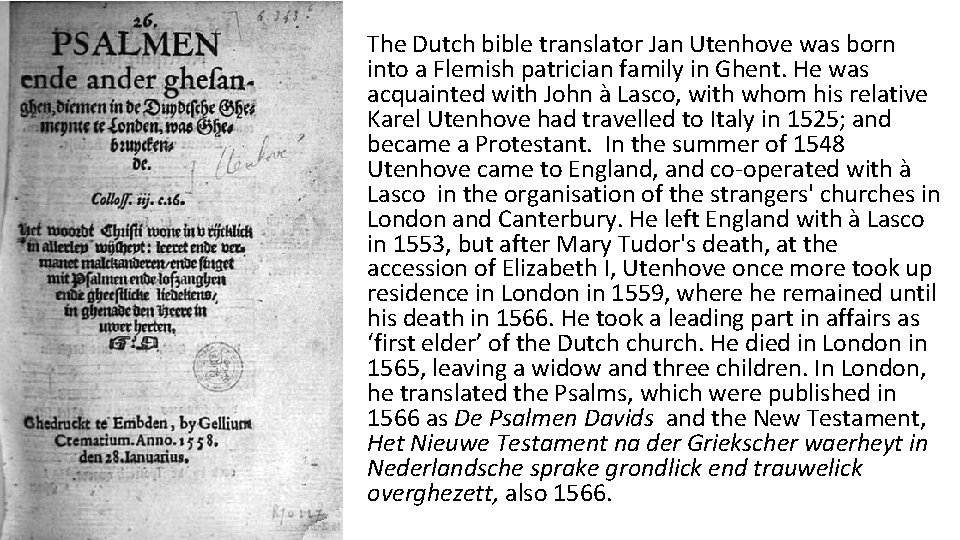

Jan Utenhove The Dutch bible translator Jan Utenhove was born into a Flemish patrician family in Ghent. He was acquainted with John à Lasco, with whom his relative Karel Utenhove had travelled to Italy in 1525; and became a Protestant. In the summer of 1548 Utenhove came to England, and co-operated with à Lasco in the organisation of the strangers' churches in London and Canterbury. He left England with à Lasco in 1553, but after Mary Tudor's death, at the accession of Elizabeth I, Utenhove once more took up residence in London in 1559, where he remained until his death in 1566. He took a leading part in affairs as ‘first elder’ of the Dutch church. He died in London in 1565, leaving a widow and three children. In London, he translated the Psalms, which were published in 1566 as De Psalmen Davids and the New Testament, Het Nieuwe Testament na der Griekscher waerheyt in Nederlandsche sprake grondlick end trauwelick overghezett, also 1566.

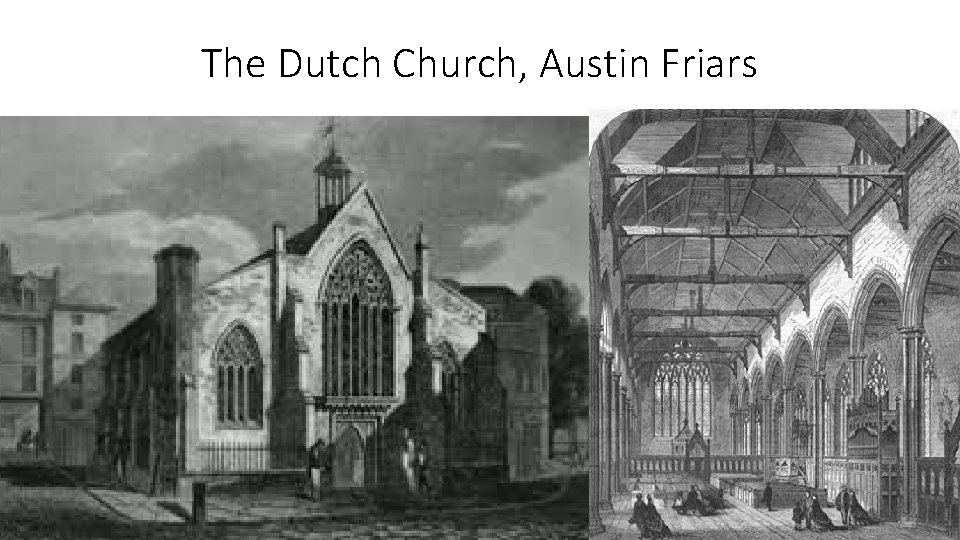

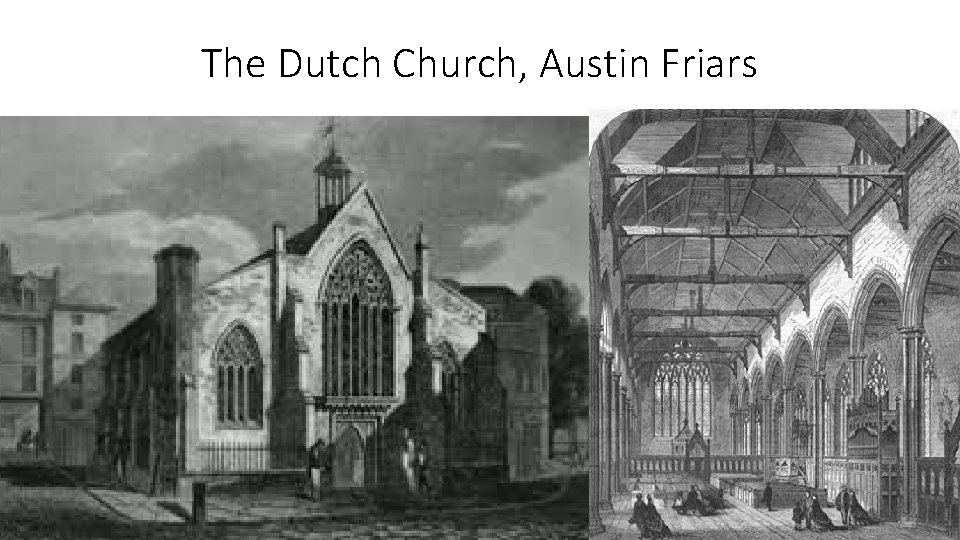

The Dutch Church, Austin Friars

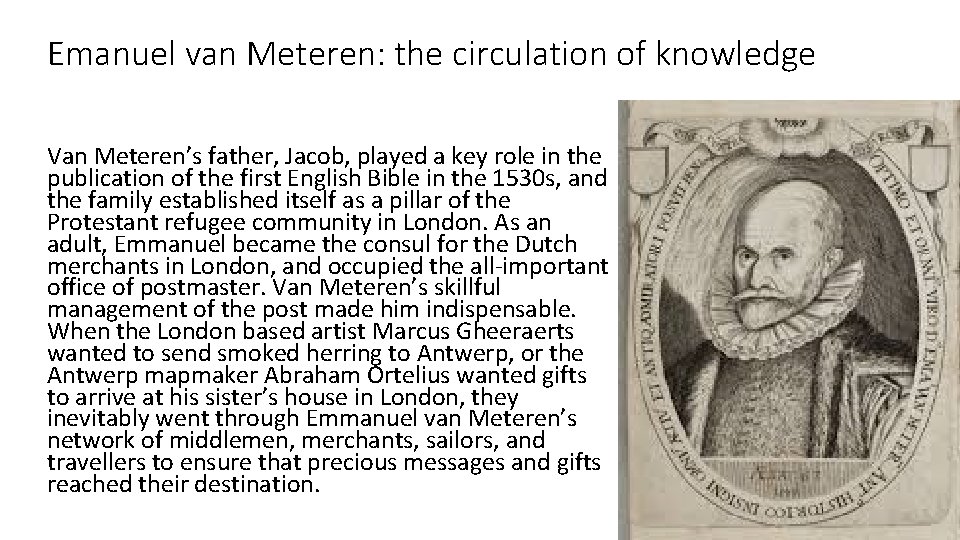

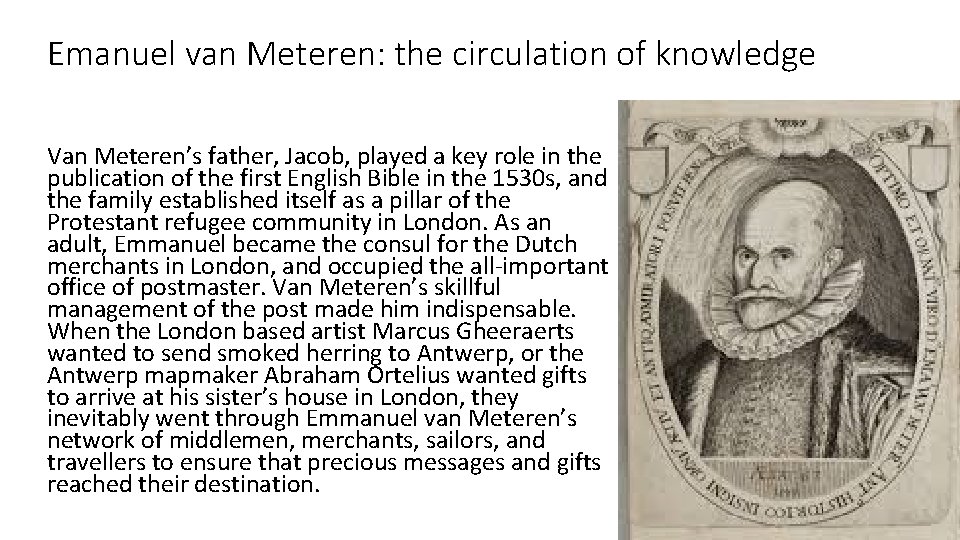

Emanuel van Meteren: the circulation of knowledge Van Meteren’s father, Jacob, played a key role in the publication of the first English Bible in the 1530 s, and the family established itself as a pillar of the Protestant refugee community in London. As an adult, Emmanuel became the consul for the Dutch merchants in London, and occupied the all-important office of postmaster. Van Meteren’s skillful management of the post made him indispensable. When the London based artist Marcus Gheeraerts wanted to send smoked herring to Antwerp, or the Antwerp mapmaker Abraham Ortelius wanted gifts to arrive at his sister’s house in London, they inevitably went through Emmanuel van Meteren’s network of middlemen, merchants, sailors, and travellers to ensure that precious messages and gifts reached their destination.

Left: Emanuel van Meteren writing in the friendship album of an Antwerp friend: he has written ‘EMANUEL’ (‘God with us’) in Hebrew. Right: anonymous contribution to his own friendship album: an emblem, ‘All Flesh is Grass’, with a fine view of London Bridge. Bodleian Library MS Douce 68

Catholics: the intimate enemy? Of if not, what? Churches were reformed for use through collective, brutal rehabbing: smashed windows, whitewashed walls, beheaded statues, and demolished altar rails. Eamonn Duffy in The Stripping of the Altars depicts a reluctant populace, clinging to pre-Reformation beliefs, pieces of rood lofts, and hopes for a return to the mother church. He presents the process of stripping the altars as a violent and distressing break from the past. Other historians argue that this process was more consensual, popular, and un-traumatic. In either case, for those who had a long association with devotional spaces that were suddenly ‘purified’ or ‘vandalized’ (depending on perspective), the experience of inhabiting these changed spaces must have been either mournful or bracing. It can hardly have been neutral.

Shakespeare’s sonnet 73: is the end of an old world relevant? That time of year thou mayst in me behold When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang Upon those boughs which shake against the cold, Bare ruin'd choirs, where late the sweet birds sang. In me thou seest the twilight of such day As after sunset fadeth in the west, Which by and by black night doth take away, Death's second self, that seals up all in rest. In me thou see'st the glowing of such fire That on the ashes of his youth doth lie, As the death-bed whereon it must expire Consumed with that which it was nourish'd by. This thou perceivest, which makes thy love more strong, To love that well which thou must leave ere long. https: //www. historyextra. com/pe riod/tudor/elizabeth-is-war-withenglands-catholics/

Foreign Catholics, and a foreign queen The Reformation literally displaced Catholics and Catholicism everywhere except London, where some Catholics could worship collectively, publicly, and theatrically in chapels maintained by foreign ambassadors. Ambassadors of Catholic nations sought to provide relief for persecuted English Catholics by protecting worship at their chapels with diplomatic immunity. The English government several times unsuccessfully attempted to dissuade such use of the Spanish and Portuguese embassies between 1563 and 1611. In 1610, James I asked foreign ambassadors not to allow English priests to celebrate at, or English Catholics to attend, their chapels, but only the Venetian ambassador complied. Anne of Denmark had a group of Catholic court ladies with whom she was intimate. Among their number was Jane Drummond, later Countess of Roxburghe (left), who facilitated the queen’s private Catholic worship. This included smuggling priests into court and disguising them as her personal attendants. The Spanish ambassador reported that ‘Mass was being said by a Scottish priest, who was simply called a ‘servant’ of [the queen’s] lady-in-waiting, Lady Drummond. ’

Some Italians in London Sir Horatio Palavicino, d. 1600. From a celebrated North Italian family, converted to Protestantism and was a leading financier in London. Giovanni Castiglione, royal language tutor to Elizabeth I, John Florio, Anglo. Italian, son of Michelangelo Florio, a Tuscan, royal language tutor at the court of James I Five Bassano brothers, Anthony, Alvise, Jasper, John (Giovanni), and Baptista Bassano, who moved from Venice to England to serve in the court of King Henry VIII. They performed as a recorder consort. Anthony was recorded as a foreigner, formerly Queen Elizabeth's musician, resident in the London parish of St Olave and All Hallows Staining, in 1607. He was married with five children, all born in England. Baptista was the father of the poet Aemilia Lanier. Petruccio Ubaldini, a Tuscan. He settled in England, where he found a patron in Henry Fitzalan, 12 th Earl of Arundel, who presented him at court. He taught Italian, transcribed and illuminated manuscripts, rhymed, and wrote or translated into Italian historical and other tracts.

Petruccio Ubaldini’s psalter for Arundel: BL Royal 2 B IX

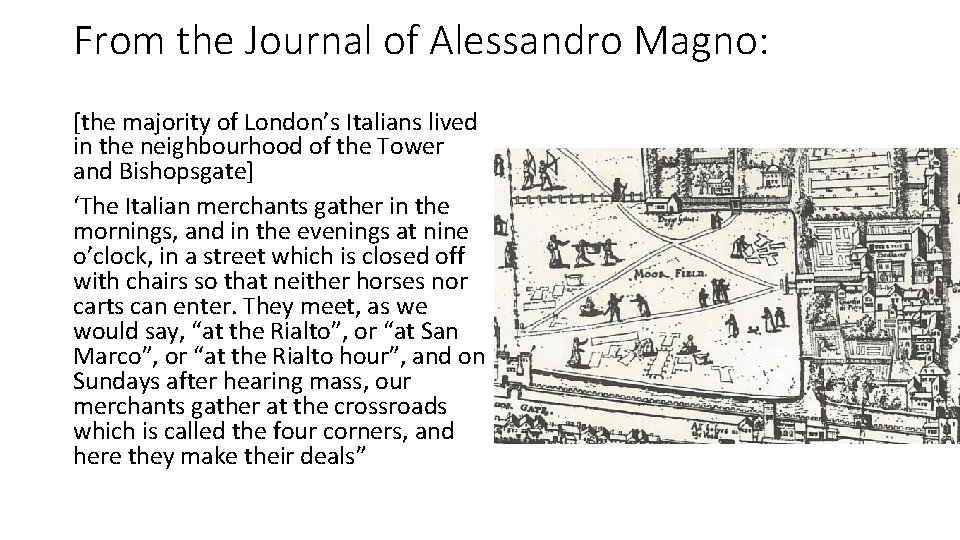

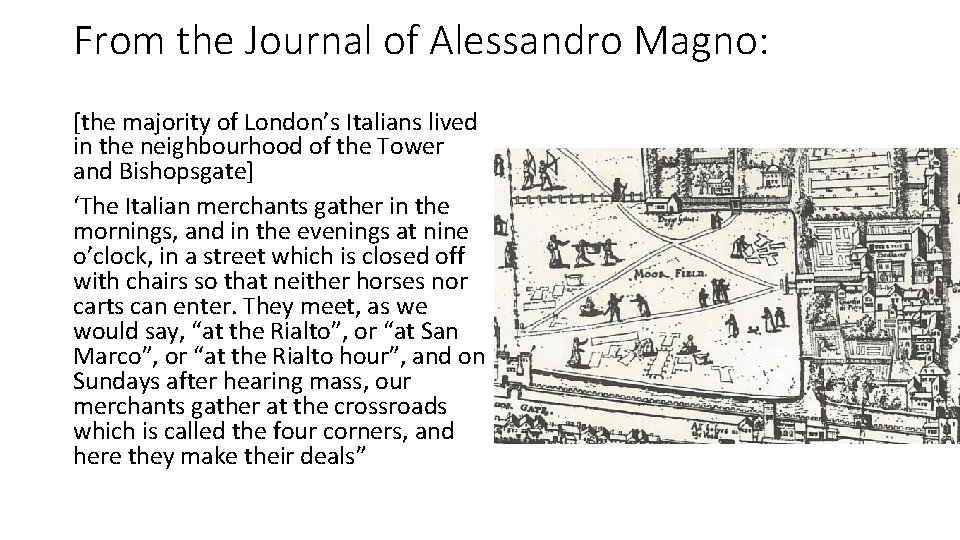

From the Journal of Alessandro Magno: [the majority of London’s Italians lived in the neighbourhood of the Tower and Bishopsgate] ‘The Italian merchants gather in the mornings, and in the evenings at nine o’clock, in a street which is closed off with chairs so that neither horses nor carts can enter. They meet, as we would say, “at the Rialto”, or “at San Marco”, or “at the Rialto hour”, and on Sundays after hearing mass, our merchants gather at the crossroads which is called the four corners, and here they make their deals”

Italian puppet shows A document from 1573 licensed Italian puppeteers to perform their ‘Strangemotions’ in England. Several puppet theatres were established, at Southbridge fair, Holborn Bridge, and Fleet Street. The letter authorising marionette and burattini precedes the first public theatre, built by Richard Burbage in Shoreditch in 1576. In 1561 the Duchess of Suffolk recorded paying ‘two men who played upon the puppets’. ‘Now, Iras, what think'st thou? Thou, an Egyptian puppet, shalt be shown In Rome, as well as I. Mechanic slaves With greasy aprons, rules, and hammers, shall Uplift us to the view. ’ Anthony and Cleopatra, Act V, sc 2

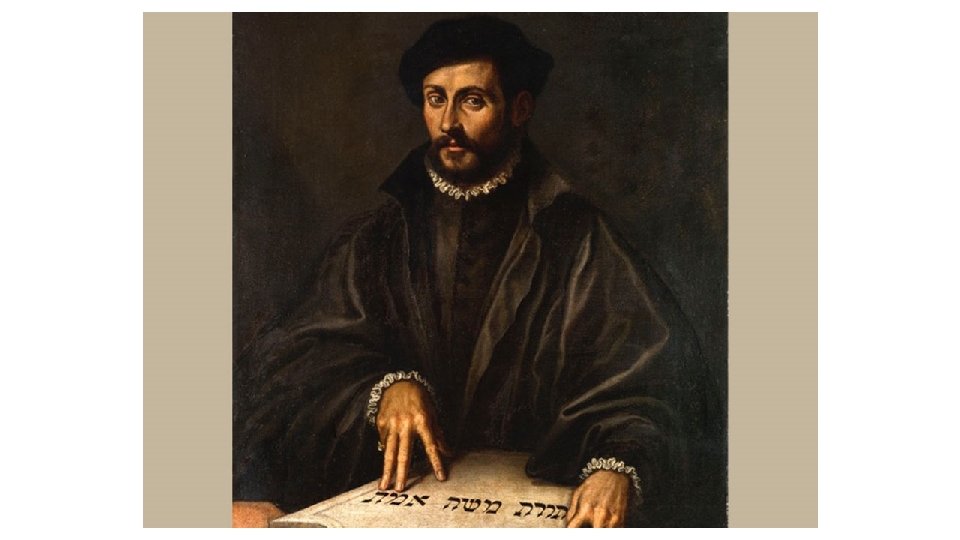

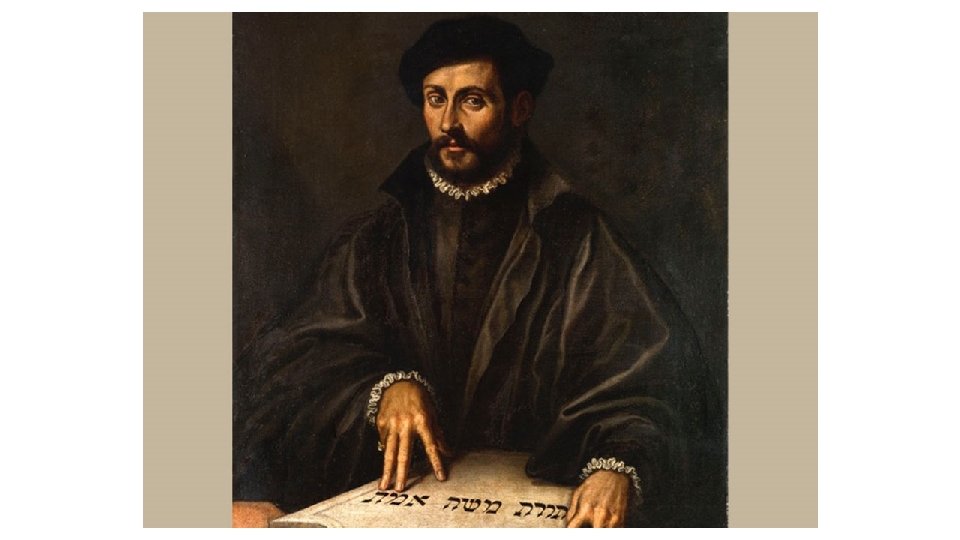

Dr Lopez; Jew Rodrigo Lopez was born c. 1517 in Crato, Portugal. His family were Jewish but had been forced to convert to Catholicism in 1497. His father was physician to King John III of Portugal. Lopes studied at the University of Coimbra, but came under suspicion of the Portuguese Inquisition and fled to England in 1559, settling in London where he managed to pass the licensing requirements to become a physician. He chose to be baptized and became a member of the Church of England, but there is evidence his family did practice Jewish rites at home. He was successful, and became the Queen’s doctor: since he spoke five languages, worked as an agent of intelligence first for Walsingham, then for Lord Burleigh. He was accused of attempting to murder the Queen for a fee of fifty thousand crowns. At his trial in 1594, he said he had been tortured, vehemently denied any plot and maintained his innocence but Englishmen found it hard to believe a Jew from Portugal. Indeed, the prosecutor Sir Edward Coke called Lopez ‘a perjured, murdering villain and Jewish doctor worse than Judas himself…[not] a new Christian. . [but] a very Jew’.

Roderigo Lopez Jews: ‘intolerable scorpion-like savageness, so furiously boiling against the innocent infants of Christian Gentiles’

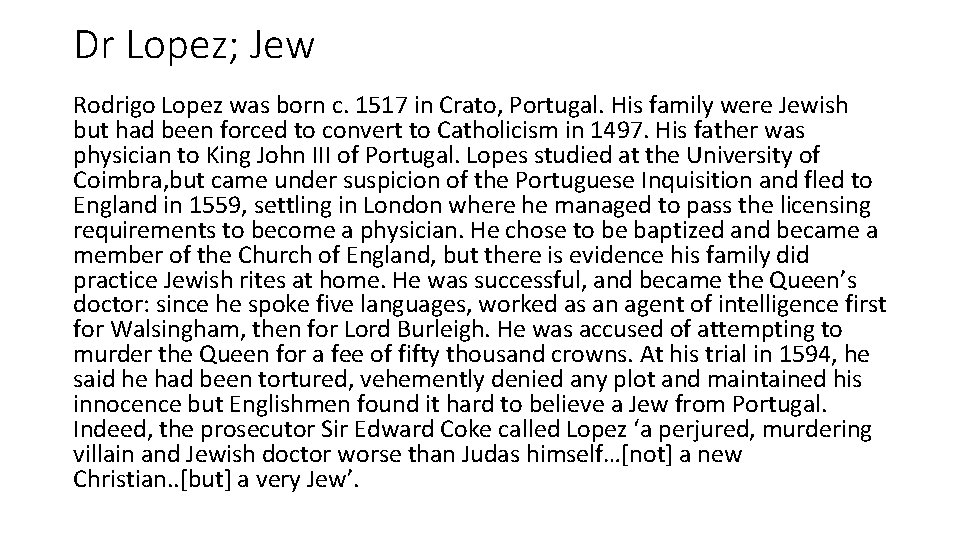

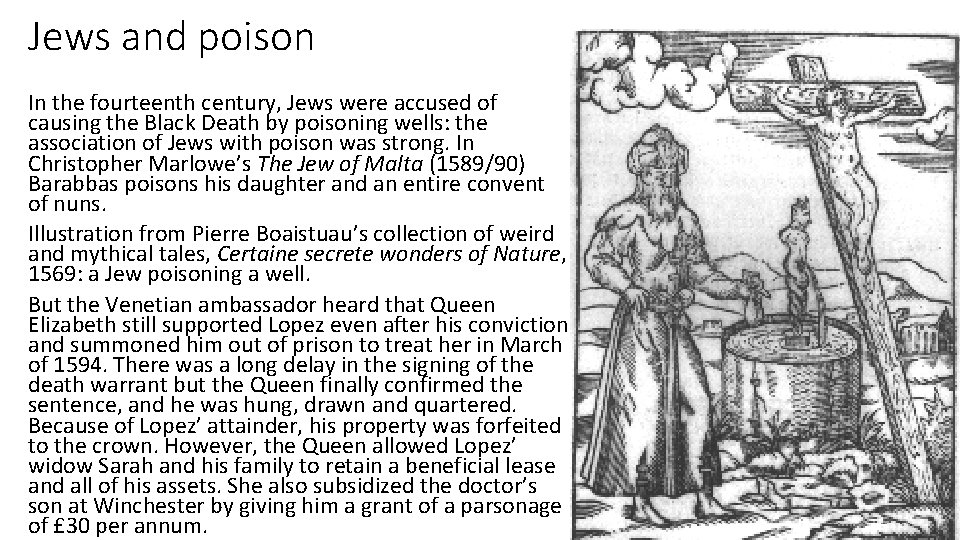

Jews and poison In the fourteenth century, Jews were accused of causing the Black Death by poisoning wells: the association of Jews with poison was strong. In Christopher Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta (1589/90) Barabbas poisons his daughter and an entire convent of nuns. Illustration from Pierre Boaistuau’s collection of weird and mythical tales, Certaine secrete wonders of Nature, 1569: a Jew poisoning a well. But the Venetian ambassador heard that Queen Elizabeth still supported Lopez even after his conviction and summoned him out of prison to treat her in March of 1594. There was a long delay in the signing of the death warrant but the Queen finally confirmed the sentence, and he was hung, drawn and quartered. Because of Lopez’ attainder, his property was forfeited to the crown. However, the Queen allowed Lopez’ widow Sarah and his family to retain a beneficial lease and all of his assets. She also subsidized the doctor’s son at Winchester by giving him a grant of a parsonage of £ 30 per annum.

The Merchant of Venice (1596/99) He hath disgraced me, and hindered me half a million; laughed at my losses, mocked at my gains, scorned my nation, thwarted my bargains, cooled my friends, heated mine enemies; and what's his reason? I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? if you tickle us, do we not laugh? if you poison us, do we not die? and if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong a Christian, what is humility? Revenge. If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge. The villany you teach me, I will execute. Act III sc 1

A new Song, shewing the crueltie of Gernutus a Iew, who lending to a Marchant a hundred Crownes, would haue a pound of his Flesh, because he could not pay him at the day appoynted (London, 1620) Gernutus called was the Jew, Which never thought to dye, Nor ever yet did any good To them in streets that lie. His life was like a barrow hogge, That liveth many a day, Yet never once doth any good, Until men will him slay. Or like a filthy heap of dung, That lyeth in a hoard; Which never can do any good, Till it be spread abroad. So fares it with the usurer, He cannot sleep in rest, For feare thiefe will him pursue To plucke him from his nest.

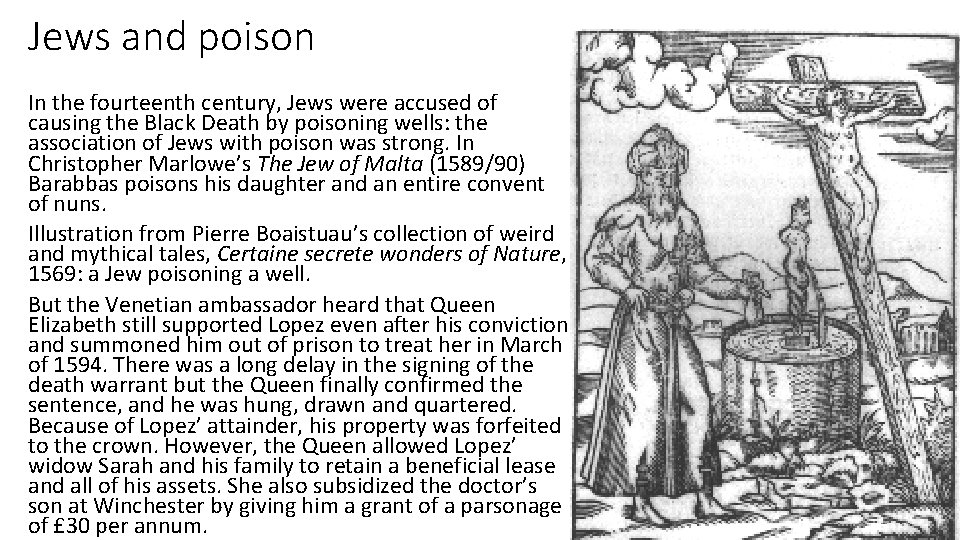

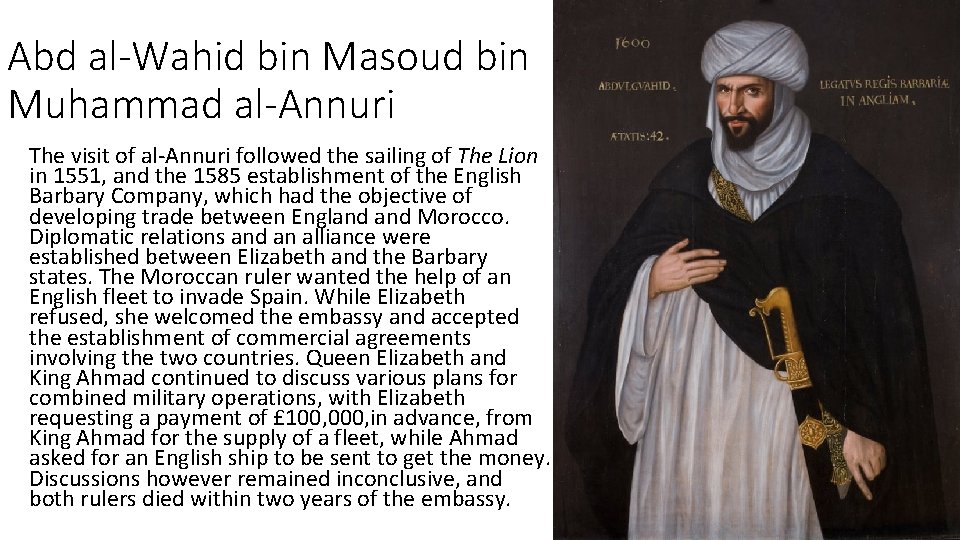

Abd al-Wahid bin Masoud bin Muhammad al-Annuri The visit of al-Annuri followed the sailing of The Lion in 1551, and the 1585 establishment of the English Barbary Company, which had the objective of developing trade between England Morocco. Diplomatic relations and an alliance were established between Elizabeth and the Barbary states. The Moroccan ruler wanted the help of an English fleet to invade Spain. While Elizabeth refused, she welcomed the embassy and accepted the establishment of commercial agreements involving the two countries. Queen Elizabeth and King Ahmad continued to discuss various plans for combined military operations, with Elizabeth requesting a payment of £ 100, 000, in advance, from King Ahmad for the supply of a fleet, while Ahmad asked for an English ship to be sent to get the money. Discussions however remained inconclusive, and both rulers died within two years of the embassy.

Othello: ‘Blackamoor’, or ‘Tawny Moor’? Only months after Al-Annuri’s public departure, Shakespeare began a play with a Moor as its central character. The similarities to Al-Annuri are striking. Othello is a mercenary, invited into the heart of a Christian community to fight the infidel but who is eventually unceremoniously expelled. As with Al‑Annuri, his ethnicity and religion are obscure. Asked his story, he speaks: ‘Of being taken by the insolent foe And sold to slavery; of my redemption thence And portance in my traveller’s history. ’ Is Othello born a Muslim or a polytheistic Berber? Is the ‘insolent foe’ he mentions the Turks? And does his slavery lead to a religious conversion prior to his Christian ‘redemption’? If Othello has converted from one religion to another, might he ‘turn’ again? As the play ends with Desdemona dead, Othello reminds the horrified Venetians: ‘… that in Aleppo once, Where a malignant and a turbaned Turk Beat a Venetian and traduced the state, I took by th’ throat the circumcised dog And smote him – thus!’

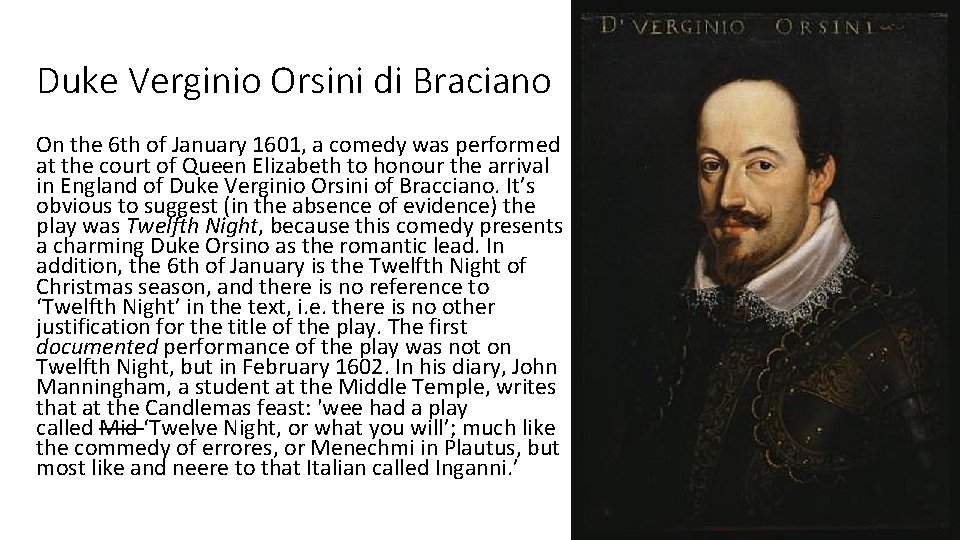

Duke Verginio Orsini di Braciano On the 6 th of January 1601, a comedy was performed at the court of Queen Elizabeth to honour the arrival in England of Duke Verginio Orsini of Bracciano. It’s obvious to suggest (in the absence of evidence) the play was Twelfth Night, because this comedy presents a charming Duke Orsino as the romantic lead. In addition, the 6 th of January is the Twelfth Night of Christmas season, and there is no reference to ‘Twelfth Night’ in the text, i. e. there is no other justification for the title of the play. The first documented performance of the play was not on Twelfth Night, but in February 1602. In his diary, John Manningham, a student at the Middle Temple, writes that at the Candlemas feast: 'wee had a play called Mid ‘Twelve Night, or what you will’; much like the commedy of errores, or Menechmi in Plautus, but most like and neere to that Italian called Inganni. ’

Jane campion tissues

Jane campion tissues Ashley jane campion

Ashley jane campion Mercutio meaning

Mercutio meaning Shakespeare 1587

Shakespeare 1587 Where was hamlet born

Where was hamlet born Themes of jealousy

Themes of jealousy Shakespeares idioms

Shakespeares idioms Shakespeares tragedy about racism and jealousy

Shakespeares tragedy about racism and jealousy Raphael campion

Raphael campion Sonya campion

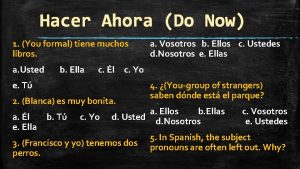

Sonya campion ¿(you ) (group of strangers) saben dónde está el parque?

¿(you ) (group of strangers) saben dónde está el parque? Cohesive adverbs

Cohesive adverbs De strangers 't strand van 't st. anneke

De strangers 't strand van 't st. anneke Butterflies true friends strangers barnacles

Butterflies true friends strangers barnacles Will't please you sit and look at her

Will't please you sit and look at her Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers

Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers De strangers ziekenkas

De strangers ziekenkas Runners repeaters strangers

Runners repeaters strangers Stranger things theme genre

Stranger things theme genre Louis balfour

Louis balfour Jeremy stevenson formulatrix

Jeremy stevenson formulatrix Dr john stevenson

Dr john stevenson Peter stevenson compassion in world farming

Peter stevenson compassion in world farming Donoghue v stevenson case summary

Donoghue v stevenson case summary Zechariah stevenson

Zechariah stevenson Jude stevenson

Jude stevenson Maeve stevenson

Maeve stevenson Dr matthew stevenson

Dr matthew stevenson Cuadrante de stevenson

Cuadrante de stevenson John stevenson bible study

John stevenson bible study John stevenson syndrome

John stevenson syndrome Stevenson and black 2007 inclusion spectrum

Stevenson and black 2007 inclusion spectrum Stevenson screen unit of measurement

Stevenson screen unit of measurement Zechariah stevenson sentence

Zechariah stevenson sentence Donoghue v stevenson case summary

Donoghue v stevenson case summary What are these

What are these Acts 10:19-20

Acts 10:19-20 Rowland v stevenson

Rowland v stevenson Valerie stevenson

Valerie stevenson Donoghue vs stevenson summary

Donoghue vs stevenson summary Mary stevenson cassatt

Mary stevenson cassatt Dr john stevenson

Dr john stevenson Maeve stevenson

Maeve stevenson Building a life howard stevenson

Building a life howard stevenson I am zealous

I am zealous