Shakespeares Humor Irony and Language Play 1 Humor

- Slides: 16

Shakespeare’s Humor, Irony, and Language Play 1

Humor in Shakespeare’s Comedies As an example of a Shakespearean comedy consider A Midsummer Night’s Dream. It is a “comedy of humors” with many eccentric characters, but the magic in the play makes the characters even funnier. Bottom, for example, ends up with the head of an ass. His name is Bottom, and in English, one’s “bottom” is one’s “ass. ” 2

Humor in Shakespeare’s Romances The women in Shakespeare’s romances can be uppity until the last act, when everybody gets married and the natural order is restored (with the man in charge) so they can live happily ever after. This is true in Much Ado about Nothing, and it is also true in The Taming of the Shrew, where in the last act the shrew gets tamed. Romeo and Juliet is a romance that begins as a comedy and ends as a tragedy. Mercutio is a mercurial or comic figure. When Romeo asks how badly he is wounded, he says, “ ‘Tis not so deep as a well, nor so wide as a church-door, but ‘tis enough, ‘twill serve…. Ask for me tomorrow, and you will find me a grave man. ” 3

Humor in Shakespeare’s Tragedies The humor in Shakespeare’s tragedies is more important than is that in his comedies. When the tragedy becomes unbearable, Shakespears inserts humor not only for comic relief, but also to contrast with the stark tragedy that came before and will surely follow afterward. Here are some examples: The drunken porter scene in Macbeth The fool-is-smarter-than-the-king dialogue in King Lear The Polonius in the wings speech in Hamlet And the grave digger’s scene in Hamlet: “Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horation; a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy…. Where be your gibes now? Your gambols? Your songs? Your flashes of merriment, that were wont to set the table on a roar? Not one now, to mock your own grinning. ” 4

Comedy of Errors (1592) Alleen and I will discuss the humor, irony, and language play of Shakespearean plays going from 1592 to 1606. In the process, we will contrast the humor of Shakespearean comedies with that in his tragedies, and we’ll also contrast the humor of Shakespeare’s male characters vs. that of his female characters. Comedy of Errors (1592) is a knockabout farce, but a knockabout farce with a difference, because the characters in the play and the issues being presented are serious ones—love, fidelity, and personal honor (Bryant 25). 5

Twelfth Night (1599) In sixteenth century England there were the twelve days of Christmas which was followed by “twelfth night, ” the title of one of Shakespeare’s plays. On the twelfth night, Christ was supposedly revealed to the Magi, who represented the Gentile world. The “Twelfth Night” was, therefore, the night of the Epiphany. It also became celebrated as a festive day of misrule. “Servants took their masters’ places for a day and the lower orders were allowed impertinence against their betters that would have been heavily fined any other time of the year. The festivity generally celebrated the age of grace that Christ ushered in, the age in which it was revealed that human sins were already cleansed in the blood of God’s Son” (Grawe 110 -111). 6

In Twelfth Night, everyone is a fool except for the fool. Viola fools others by dressing up as a man. Sir Toby fools Malvolio. The lovers fool themselves by pursuing characters who are not interested in them. Feste, on the other hand, knows them all for the fools that they are (Draper 211 -212). Feste is perhaps the shrewdest character in Twelfth Night. He is an excellent manipulator and can quickly adapt his talents and wit to serve him in any situation. The tools of music, speech, and action are always in close reach of his clever mind. He confounds Sir Andrew with nonsense, and outwits his mistress with logical paradoxes. He wisely ascertains that he cannot entertain Malvolio at all and so he entertains himself at Malvolio’s expense (Draper 204). 7

Feste, the fool in Twelfth Night is a character reminiscent of the character of Vice in the Tudor morality plays. Vice was a crude character who taunted the Devil with a wooden dagger and rode off the stage on the Devil’s back (Hotson 84). Fest leaves the stage in the same way: “I am gone, sir, / And anon, sir, / I’ll be with you again, / In a trice, / Like to the old vice, / Your need to sustain; / Who, with dagger of lath, / In his rage and his wrath, / Cries, ah, ha! To the devil: / Like a mad lad, / Pare thy nails, dad; / Adieu, goodman devil” (Evans 132). 8

Hamlet (1600) There is much irony in Hamlet. The most famous pun in Hamlet occurs after Hamlet decides to obey the ghost. Horatio’s question, “To what issue will this come? ” is a play on that which issues from an arse, i. e. a fart, and Marcellus answers that “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark. ” Claudius, of course, is the state of Denmark, and it is Claudius which is rotten (Rubinstein 186). 9

When Horatio mentions that the funeral of Hamlet’s father and the marriage of Hamlet’s mother come very close together, Hamlet ironically replies, “ ‘Thrift, thrift, Horatio! The funeral bak’d meats / Did coldly furnish forth the marriage tables. ’” Hamlet gives this ridiculous explanation of his mother’s hasty wedding ironically, in order to intensify his revulsion at the lust which he and Horatio both recognize as the real explanation (Booth, 177). 10

Macbeth (1606) There is very dark humor and irony in Macbeth when Lady Macbeth taunts her husband by equating his desires to kill the king with his sexual promises. “She links his twin deeds of assassination and lovemaking” (Homan 940). The play Macbeth also contains the famous “drunken porter scene of Act 2, Scene iii. This scene comes between the murder of King Duncan and the discovery of his body, and is therefore the most tense moment of the play. The audience is in an extreme state of arousal, as the drunken porter, before answering the loud knocking at the castle gate, decides to play the role of the gate keeper in Hell. In his fantasy, he opens the gates of Hell to admit a failed farmer, an equivocator, and an English tailor, before he, in reality, actually opens the castle gate and admits the messenger. 11

The drunken porter scene is comic relief, and occurs at a time in the play when the audience needs comic relief. But the comic relief of the drunker porter scene also adds to the tragedy of the play in two ways: First, it allows the audience to take a breath and prepare themselves for more tragedy. And second, it provides a comic foil against which the tragedy becomes even more tragic (Derks 52). 12

Conclusion # 1: Shakespeare’s Tragedies vs. Shakespeare’s Comedies Shakespearean tragedy is engaging, while Shakespearean comedy is transcending. But they are different in another way as well. Northrup Frye says, “just as comedy often sets up an arbitrary law and then organizes the action to break or evade it, so tragedy presents the reverse theme of narrowing a comparatively free life into a process of causation. ” (166) This process of causation happens in Macbeth when he accepts the logic of usurpation, to Hamlet when he accepts the logic of revenge, to Lear when he accepts the logic of abdication (Frye 212). 13

Frye says that in comedy there tends to be a “tricky slave” (dolosus servus”) that is an “eiron” figure who acts from a pure love of mischief, and is able to set the comic action going (212). Some of these “tricky slaves” or “vices” can be as lighthearted as Puck in A Midsumer Night’s Dream, or as malevolent as Don John in Much Ado about Nothing (Frye 137). Shakespeare’s comedies also have a buffoon character, which Frye describes as an “entertainer. ” He is jovial and loquacious and both Falstaff and Sir Toby Belch are examples (Frye 175). 14

Conclusion # 2: Women in Shakespeare’s Comedies Carol Neely suggests that in Shakespeare’s comedies there are four women whose skills at logic, wit, and language play make them as strong as the strongest of Shakespeare’s men. These women are Katharine in The Taming of the Shrew, Portia in The Merchant of Venice, Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing, and Rosalind in As You Like It. Katharine ends up subjecting herself to marriage, but is able to keep her independence in the end. Portia, the most intellectual of the women, takes on the disguise of a male lawyer in order to prove her superior intellect to the men of Venice. 15

Beatrice uses her charming intellect to match wits with Benedick, thus proving her equality. And Rosalind disguises herself as a man, in which guise she befriends her own lover and takes control of all the events around her, making sure that everything comes to a happy conclusion. These plays all begin in a man’s world, but the women come in and take over, and by their intelligence and wit, they “transform the men from foolish lovers into—we hope—sensible husbands” (Neely 215). In her Shakespearean Comedy, Chintamani Desai notes that whenever Shakespeare has a battle of wits between a man and a woman the woman is bound to win. Much of Shakespearean Comedy is the result of the clash between the male and female intelligences. They hinge on the conflict between their wits. “And in this conflict, man is the loser. For wit is woman’s special quality as well as weapon” (Desai 45). 16

Situational irony vs dramatic irony

Situational irony vs dramatic irony Themes about jealousy

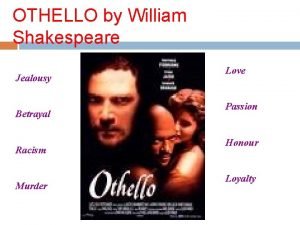

Themes about jealousy Shakespeare tragedy about racism and jealousy

Shakespeare tragedy about racism and jealousy Romeo's father

Romeo's father Humor vítreo e humor aquoso

Humor vítreo e humor aquoso Shakespeare 1587

Shakespeare 1587 Themes of hamlet

Themes of hamlet Shakespeares idioms

Shakespeares idioms Irony playfulness black humor

Irony playfulness black humor Dynamic irony

Dynamic irony I've got a friend we like to play we play together

I've got a friend we like to play we play together Louise made the chocolate cake active or passive

Louise made the chocolate cake active or passive Play by play

Play by play Hamlet

Hamlet Symbolic play and language development

Symbolic play and language development Valiant romeo and juliet

Valiant romeo and juliet Types of irony in pride and prejudice

Types of irony in pride and prejudice