SESSION 1 KEY ELEMENTS OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH 2

- Slides: 29

SESSION 1. KEY ELEMENTS OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH 2. OBSERVATION AS A RESEARCH METHOD 3. INTRODUCING QUALITATIVE DATA ANALYSIS Anuj Kapilashrami, Global Public Health Unit

Qualitative research is difficult to define clearly. It has no theory or paradigm that is distinctively its own…Nor does qualitative research have a distinct set of methods or practices that are entirely its own. . - Denzin & Lincoln (2011: 6) PART 1. QUALITATIVE RESEARCH Key characteristics

Qualitative research is… “…a set of interpretive, material practices that make the world visible. . . ” “Qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings attempting to make sense of or interpret phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them” (Denzin & Lincoln 2011: 3) � There are multiple qualitative methodologies (underpinned by different worldviews/knowledge).

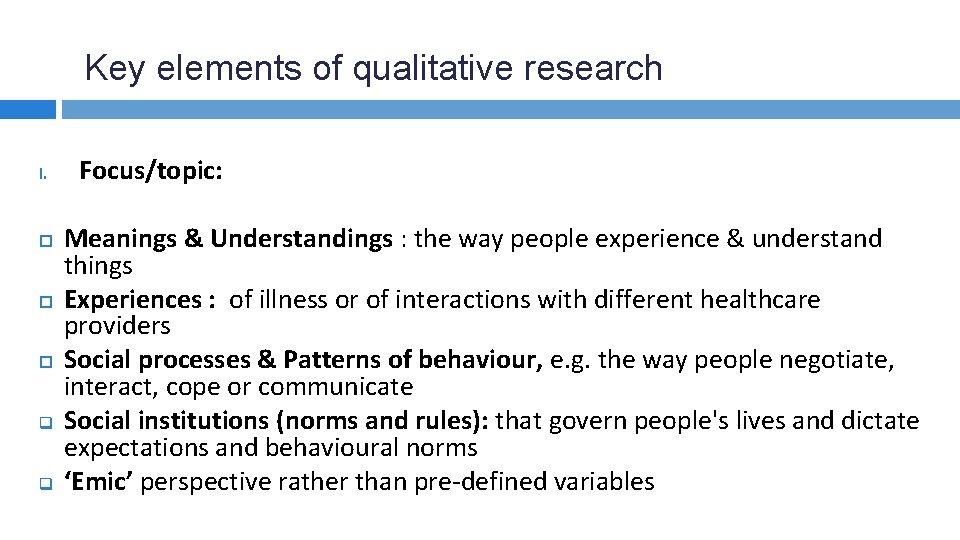

Key elements of qualitative research I. q q Focus/topic: Meanings & Understandings : the way people experience & understand things Experiences : of illness or of interactions with different healthcare providers Social processes & Patterns of behaviour, e. g. the way people negotiate, interact, cope or communicate Social institutions (norms and rules): that govern people's lives and dictate expectations and behavioural norms ‘Emic’ perspective rather than pre-defined variables

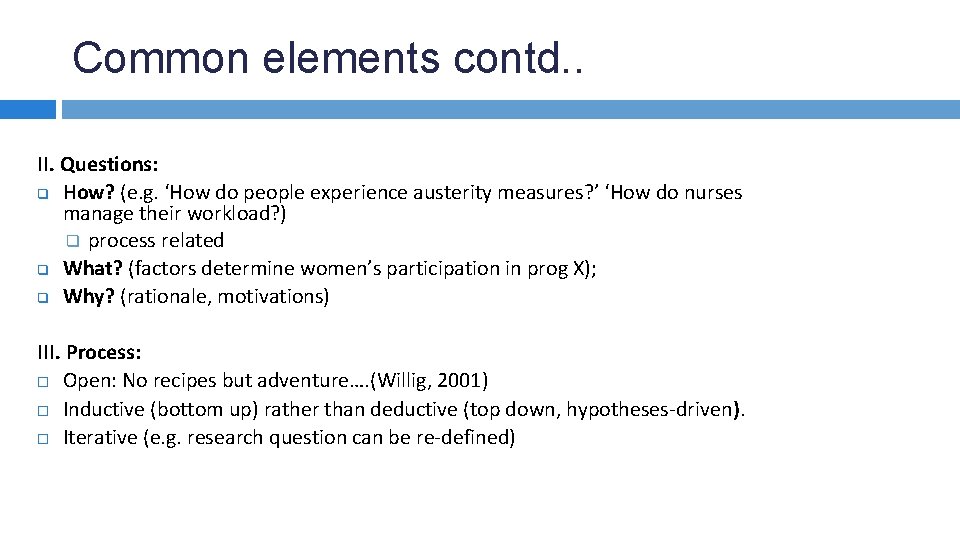

Common elements contd. . II. Questions: q How? (e. g. ‘How do people experience austerity measures? ’ ‘How do nurses manage their workload? ) q process related q What? (factors determine women’s participation in prog X); q Why? (rationale, motivations) III. Process: Open: No recipes but adventure…. (Willig, 2001) Inductive (bottom up) rather than deductive (top down, hypotheses-driven). Iterative (e. g. research question can be re-defined)

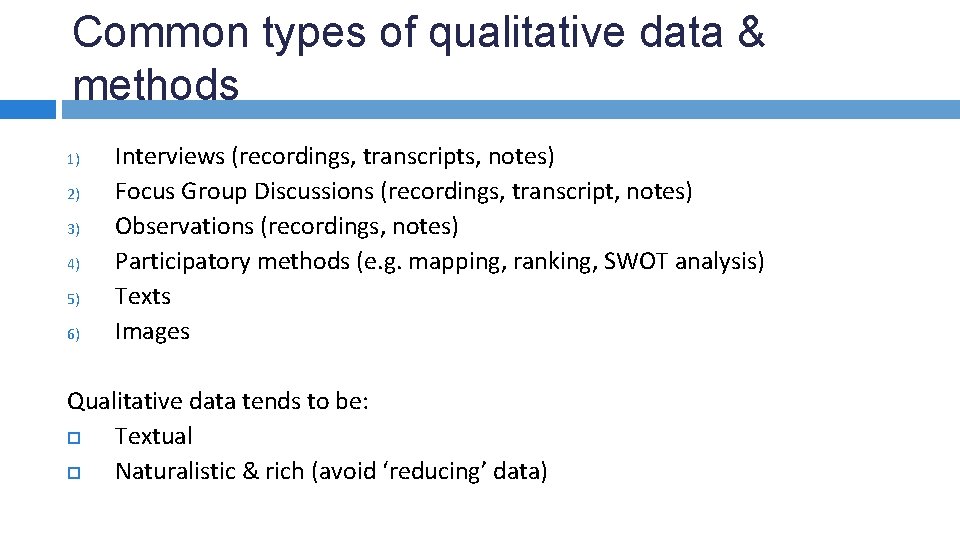

Common types of qualitative data & methods 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) Interviews (recordings, transcripts, notes) Focus Group Discussions (recordings, transcript, notes) Observations (recordings, notes) Participatory methods (e. g. mapping, ranking, SWOT analysis) Texts Images Qualitative data tends to be: Textual Naturalistic & rich (avoid ‘reducing’ data)

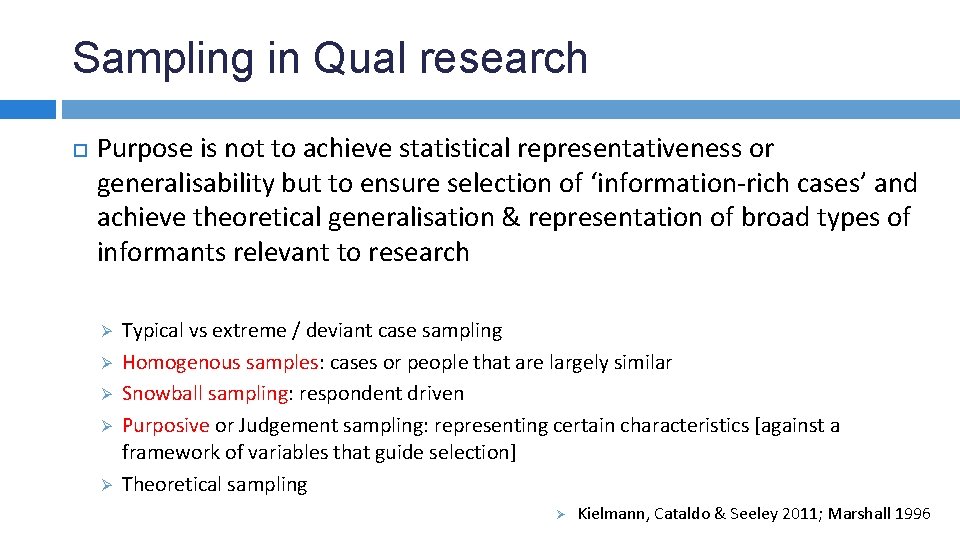

Sampling in Qual research Purpose is not to achieve statistical representativeness or generalisability but to ensure selection of ‘information-rich cases’ and achieve theoretical generalisation & representation of broad types of informants relevant to research Ø Ø Ø Typical vs extreme / deviant case sampling Homogenous samples: cases or people that are largely similar Snowball sampling: respondent driven Purposive or Judgement sampling: representing certain characteristics [against a framework of variables that guide selection] Theoretical sampling Ø Kielmann, Cataldo & Seeley 2011; Marshall 1996

Reflexivity in Qual Research Activity 1: “Doing qualitative research is by nature a reflective and recursive process. " (Ely et al, 1991: 179) DISCUSS IN PAIRS What does reflexivity mean?

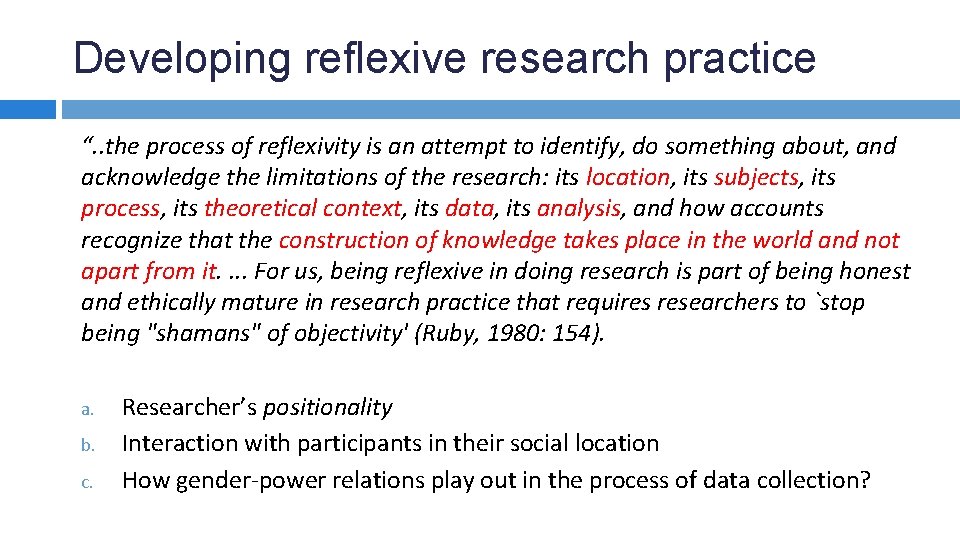

Developing reflexive research practice “. . the process of reflexivity is an attempt to identify, do something about, and acknowledge the limitations of the research: its location, its subjects, its process, its theoretical context, its data, its analysis, and how accounts recognize that the construction of knowledge takes place in the world and not apart from it. . For us, being reflexive in doing research is part of being honest and ethically mature in research practice that requires researchers to `stop being "shamans" of objectivity' (Ruby, 1980: 154). a. b. c. Researcher’s positionality Interaction with participants in their social location How gender-power relations play out in the process of data collection?

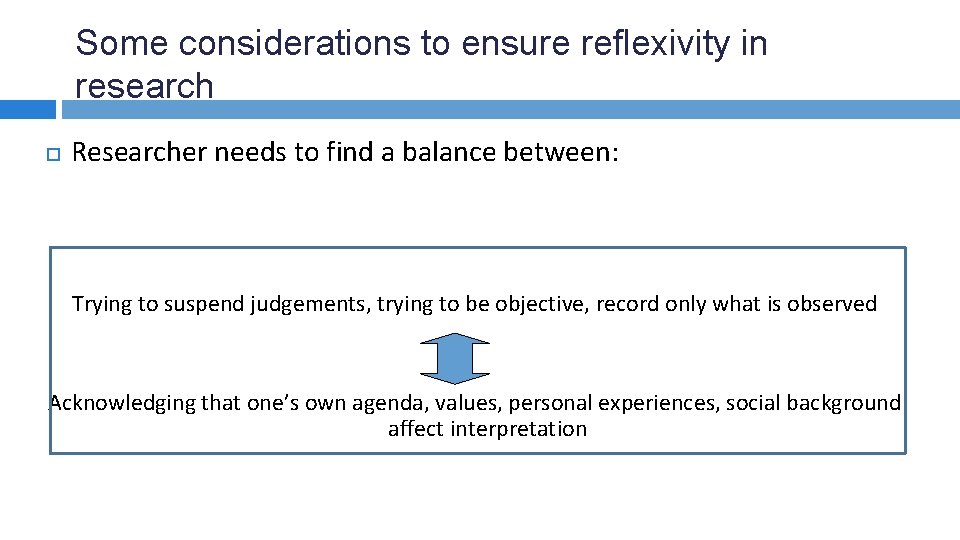

Some considerations to ensure reflexivity in research Researcher needs to find a balance between: Trying to suspend judgements, trying to be objective, record only what is observed Acknowledging that one’s own agenda, values, personal experiences, social background affect interpretation

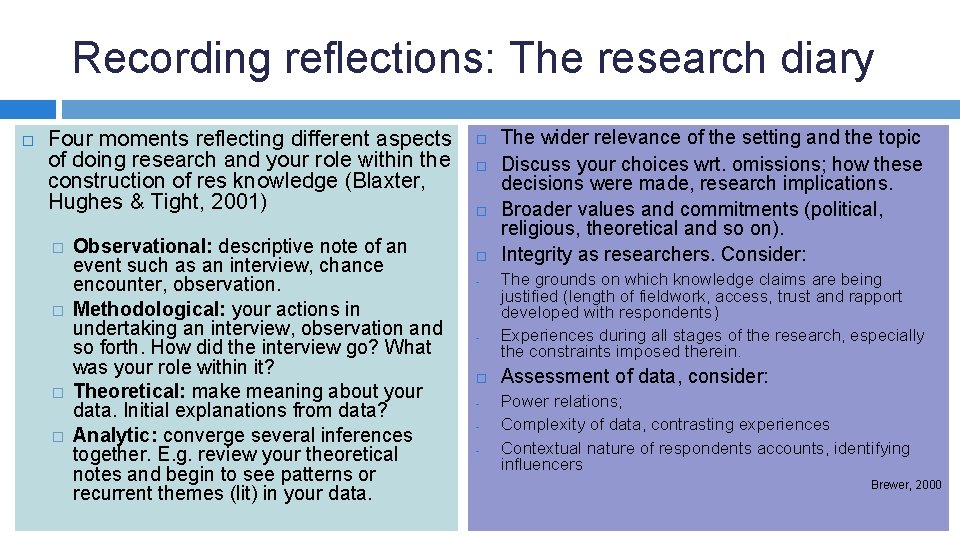

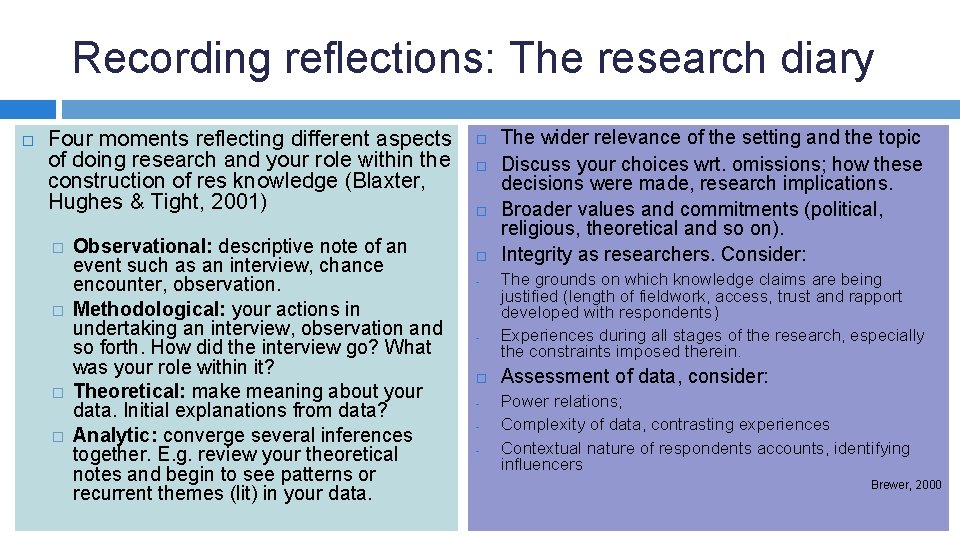

Recording reflections: The research diary Four moments reflecting different aspects of doing research and your role within the construction of res knowledge (Blaxter, Hughes & Tight, 2001) � � Observational: descriptive note of an event such as an interview, chance encounter, observation. Methodological: your actions in undertaking an interview, observation and so forth. How did the interview go? What was your role within it? Theoretical: make meaning about your data. Initial explanations from data? Analytic: converge several inferences together. E. g. review your theoretical notes and begin to see patterns or recurrent themes (lit) in your data. - - - The wider relevance of the setting and the topic Discuss your choices wrt. omissions; how these decisions were made, research implications. Broader values and commitments (political, religious, theoretical and so on). Integrity as researchers. Consider: The grounds on which knowledge claims are being justified (length of fieldwork, access, trust and rapport developed with respondents) Experiences during all stages of the research, especially the constraints imposed therein. Assessment of data, consider: Power relations; Complexity of data, contrasting experiences Contextual nature of respondents accounts, identifying influencers Brewer, 2000

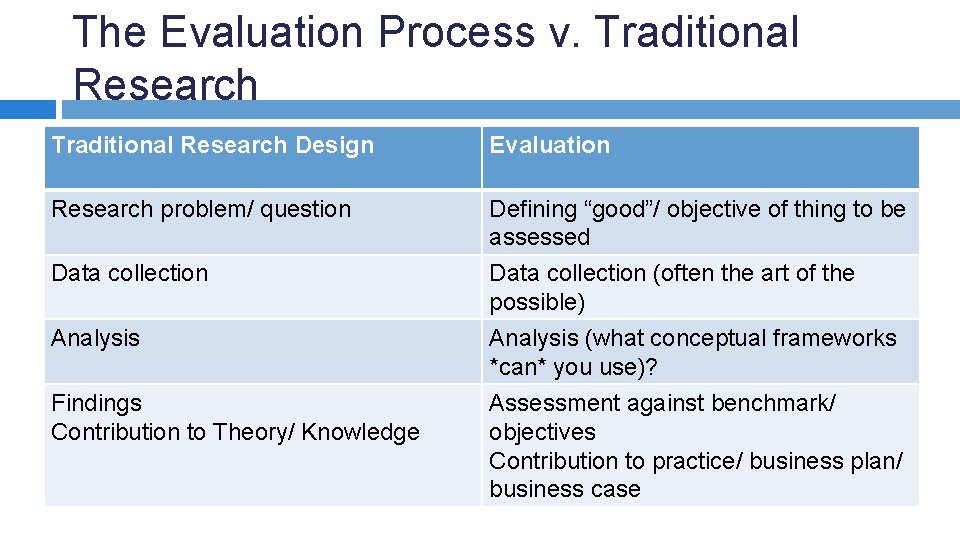

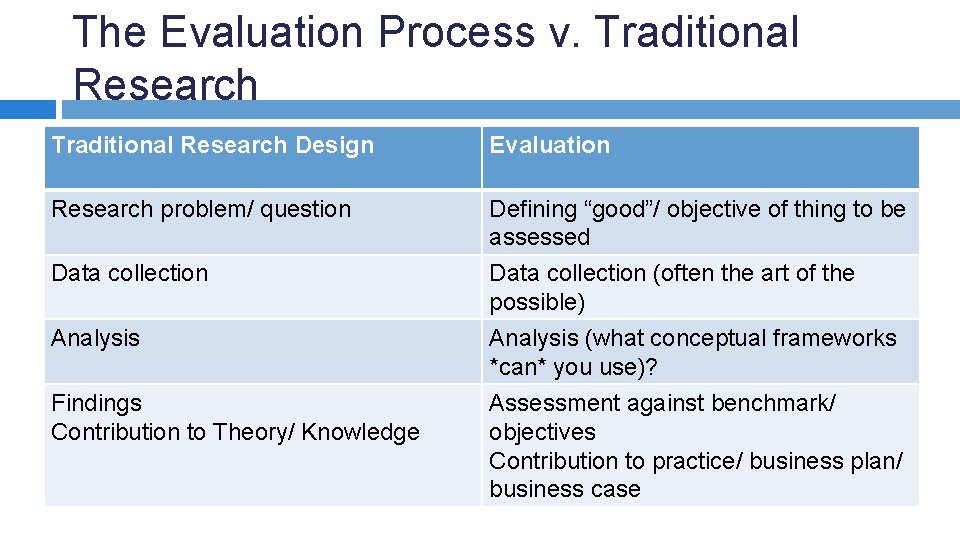

The Evaluation Process v. Traditional Research Design Evaluation Research problem/ question Defining “good”/ objective of thing to be assessed Data collection (often the art of the possible) Data collection Analysis Findings Contribution to Theory/ Knowledge Analysis (what conceptual frameworks *can* you use)? Assessment against benchmark/ objectives Contribution to practice/ business plan/ business case

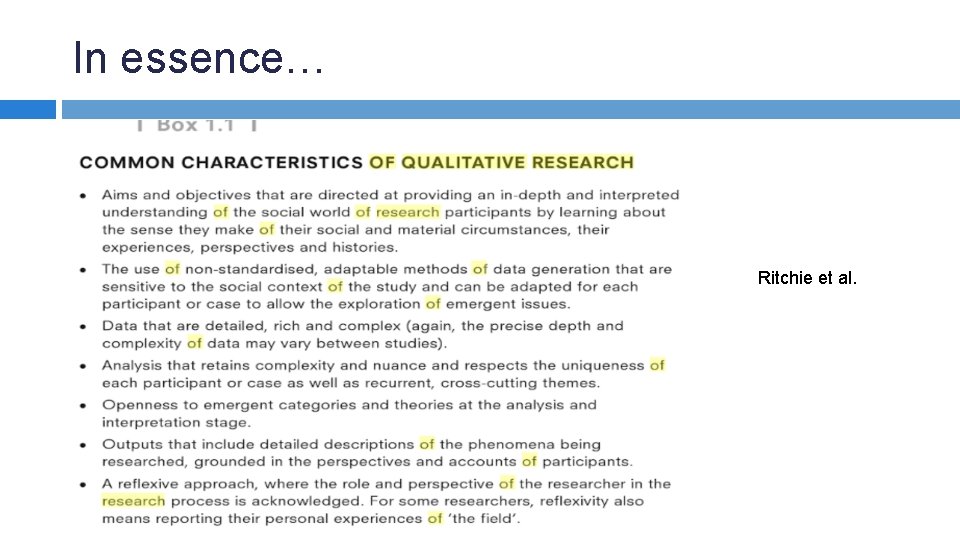

In essence… Ritchie et al.

PART III. OBSERVATION From Kielmann et al. 2011

Observation “involves situating what we see in relation to what we know about a particular setting. ” - Kielmann et al. 2011 Purpose: to gain close-up, intimate understanding of everyday practices and beliefs of a specific group of people How? spending extended time systematically collecting data about everyday life Has significant ethical and methodological considerations

Why observe? Can help answer “why? ” and “how? ” questions. Gain familiarity with the wider context & physical environment that influences behaviours Appreciation of ‘how things work’ in an unfamiliar research setting; whether reported behavior corresponds with actual behaviour Helps create coherent, situated pictures of living (sub)cultures, and to explore them “inside out”. Explore taboo or sensitive topics or otherwise hidden/ latent social phenomena.

Four criteria Direct/ Indirect Overt/ Covert - Obtrusive/ unobtrusive? Concealment/ Disclosure? ("Duplicitous" or justified? (Lugosi 2006)) Participant or Non-Participant - Intervention or "blending in”? Activism, naturalism. . . (NB Participatory methods, critical ethnography) Structured vs Unstructured BUT… This has important implications for what you can claim to know as an observer � Generalisability/ Validity � Whose meaning is whose?

Fieldnotes One of the key sources of validity and descriptive depth for a project (Sanjek, 1990). Tools/ media: audio, video, documents, material culture, pen and paper. . . � What is a "faithful representation" - simultaneous or from memory? Verbatim or impressionistic? � WHAT are you documenting? Words, things, expressions, process, bodies, spaces. . . � Fieldnotes are always a balance between expediency and representativeness, validity etc.

When is observation appropriate in a WBP? You are not going to be able to undertake a full-on, deep participant observation in the time available. � The ethical considerations are huge, never mind the practicalities! BUT approaching your personal experiences in the field with an “ethnographic sensibility” can be productive. � Make notes in your field journal/ research diary � Use observation techniques/ discipline to pay attention to local meanings and significances which you don’t share – ask THEM to explain why they do what they do/ say what they say… � Use fieldnotes to generate categories/ discussion points to shape data collection

PART III. ANALYSING QUALITATIVE DATA

Analysis is about seeing patterns and meaning Analysis is about…. . Thinking about what responses or observations mean: What do they suggest? What is their significance? In the light of your research aim and questions NB. data could suggest that you need to refine your research questions Identifying trends and patterns - similarities and differences within your data set

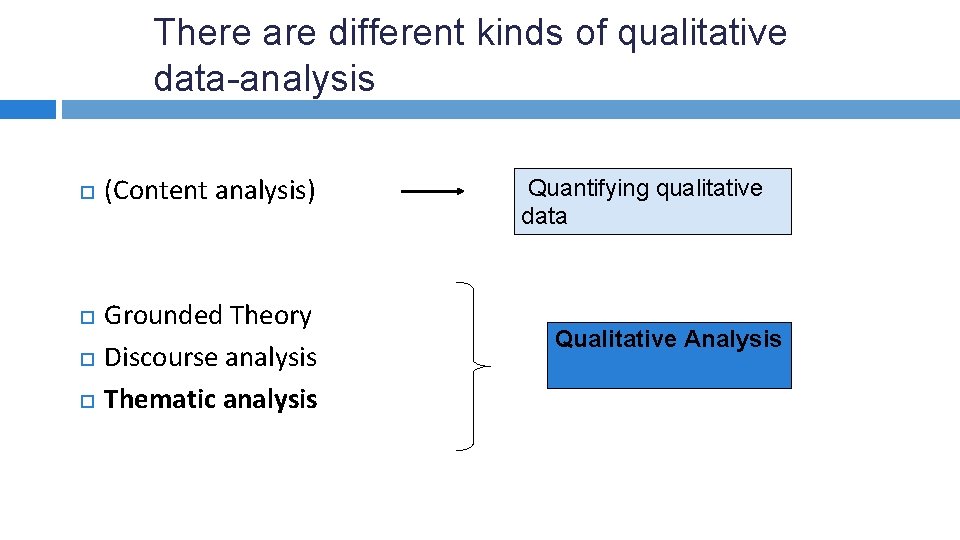

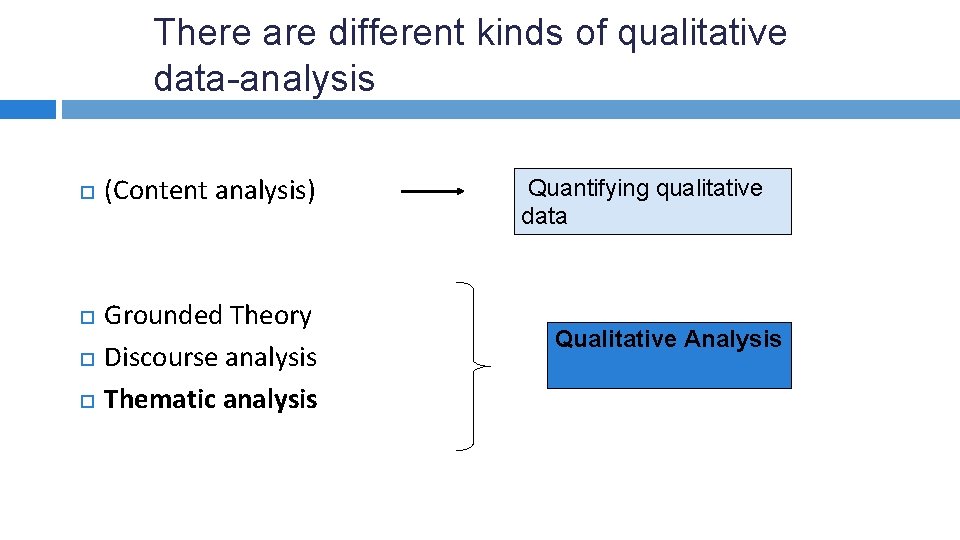

There are different kinds of qualitative data-analysis (Content analysis) Grounded Theory Discourse analysis Thematic analysis Quantifying qualitative data Qualitative Analysis

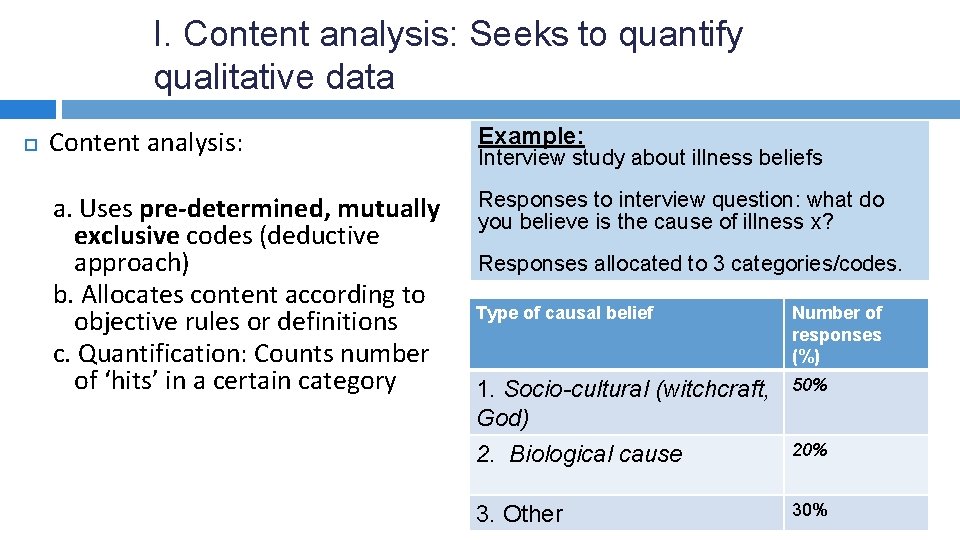

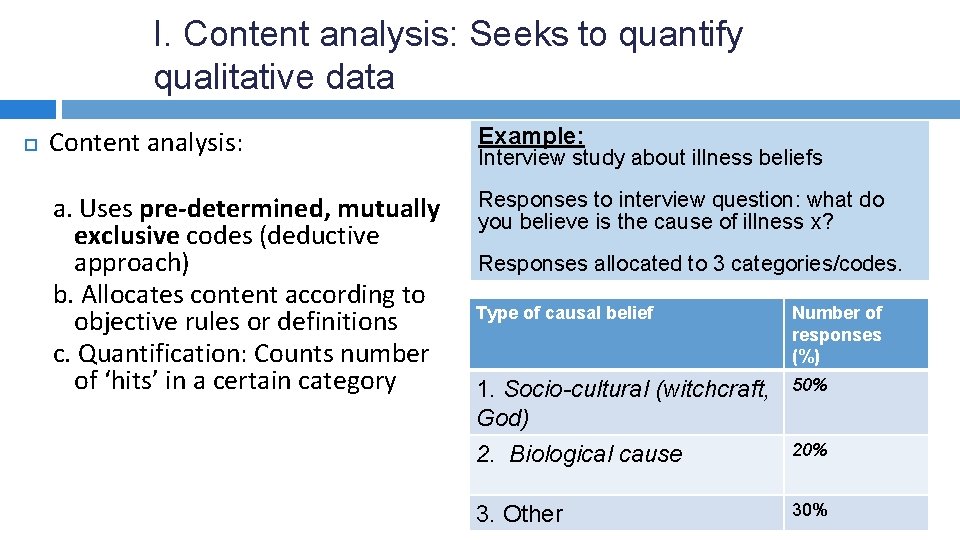

I. Content analysis: Seeks to quantify qualitative data Content analysis: Example: a. Uses pre-determined, mutually exclusive codes (deductive approach) b. Allocates content according to objective rules or definitions c. Quantification: Counts number of ‘hits’ in a certain category Responses to interview question: what do you believe is the cause of illness x? Interview study about illness beliefs Responses allocated to 3 categories/codes. Type of causal belief Number of responses (%) 1. Socio-cultural (witchcraft, God) 50% 2. Biological cause 20% 3. Other 30%

II. Grounded Theory Grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967): § A method of data collection and analysis § A product: Theory § § § Seeks to develop new theories which are grounded in data, instead of relying on preexisting hypotheses. Several specific analytic strategies and iterative steps, e. g. further ‘theoretical sampling’ after initial data collection and analysis Too elaborate & time-consuming for your MSc project NB. A watered-down version of GT is basically thematic analysis

III. Thematic analysis looks for patterns, recurrent themes in data Thematic analysis: Organizes, describes and interprets a data set, by reporting patterns (themes) within data (Braun & Clarke, 2006, p. 79). Often adds theoretical interpretation Quantification is possible, but not the main goal Inductive and deductive coding possible

Procedure of thematic analysis 1. 2. 3. 4. Transcribing Organizing your data Reading & re-reading Coding & categorising 5. Examining Relationships and Displaying Data 6. Authenticating Conclusions 7. Reflexivity

Coding proceeds in multiple steps 3) Reading & re-reading 4) Coding & categorising: i. ‘Open coding’ : Initial labelling of responses to capture their meaning. Initial codes are often very concrete, close to the text. II. III. Reflection on early coding: Do the codes ‘fit’? Do you feel like you have to ‘force’ some extracts into a code? Might a different label (code) be better? Identification of commonalities (patterns) and differences within and across interviews: Generate more abstract, recurrent themes & sub-themes.

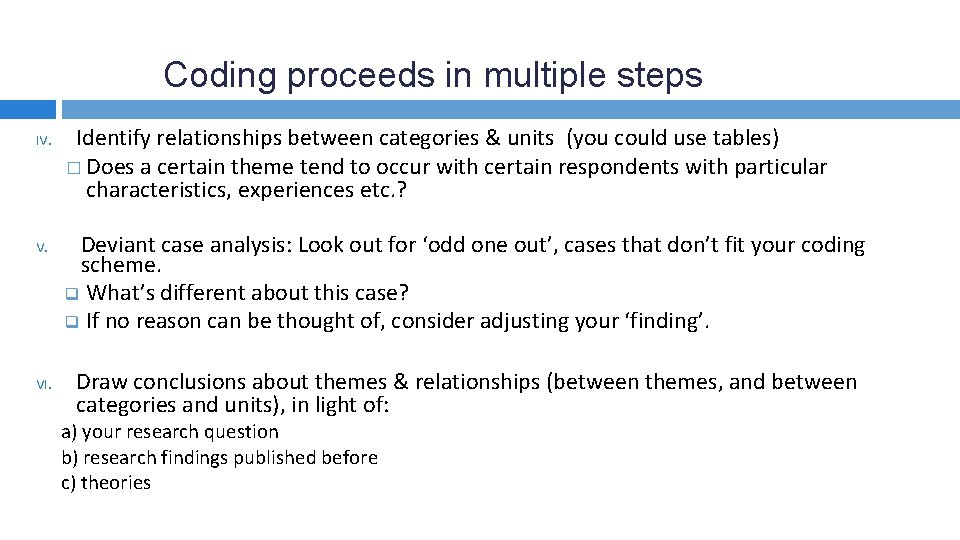

Coding proceeds in multiple steps IV. VI. Identify relationships between categories & units (you could use tables) � Does a certain theme tend to occur with certain respondents with particular characteristics, experiences etc. ? Deviant case analysis: Look out for ‘odd one out’, cases that don’t fit your coding scheme. q What’s different about this case? q If no reason can be thought of, consider adjusting your ‘finding’. Draw conclusions about themes & relationships (between themes, and between categories and units), in light of: a) your research question b) research findings published before c) theories

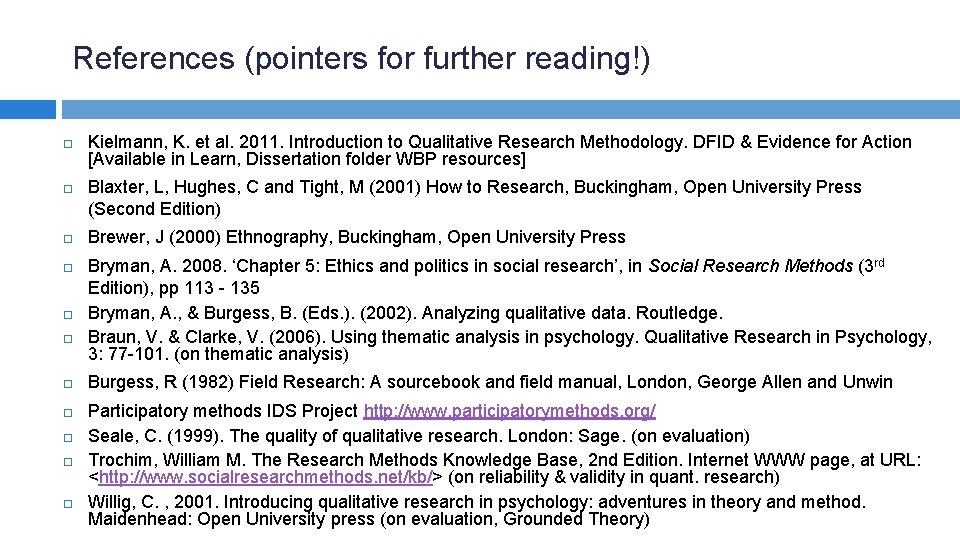

References (pointers for further reading!) Kielmann, K. et al. 2011. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methodology. DFID & Evidence for Action [Available in Learn, Dissertation folder WBP resources] Blaxter, L, Hughes, C and Tight, M (2001) How to Research, Buckingham, Open University Press (Second Edition) Brewer, J (2000) Ethnography, Buckingham, Open University Press Bryman, A. 2008. ‘Chapter 5: Ethics and politics in social research’, in Social Research Methods (3 rd Edition), pp 113 - 135 Bryman, A. , & Burgess, B. (Eds. ). (2002). Analyzing qualitative data. Routledge. Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3: 77 -101. (on thematic analysis) Burgess, R (1982) Field Research: A sourcebook and field manual, London, George Allen and Unwin Participatory methods IDS Project http: //www. participatorymethods. org/ Seale, C. (1999). The quality of qualitative research. London: Sage. (on evaluation) Trochim, William M. The Research Methods Knowledge Base, 2 nd Edition. Internet WWW page, at URL: <http: //www. socialresearchmethods. net/kb/> (on reliability & validity in quant. research) Willig, C. , 2001. Introducing qualitative research in psychology: adventures in theory and method. Maidenhead: Open University press (on evaluation, Grounded Theory)