Sensors calibration and orientation Eduardo Abaroa Delfin de

Sensors, calibration and orientation Eduardo Abaroa: Delfin de supervision Mark Johnson markjohnson@st-andrews. ac. uk

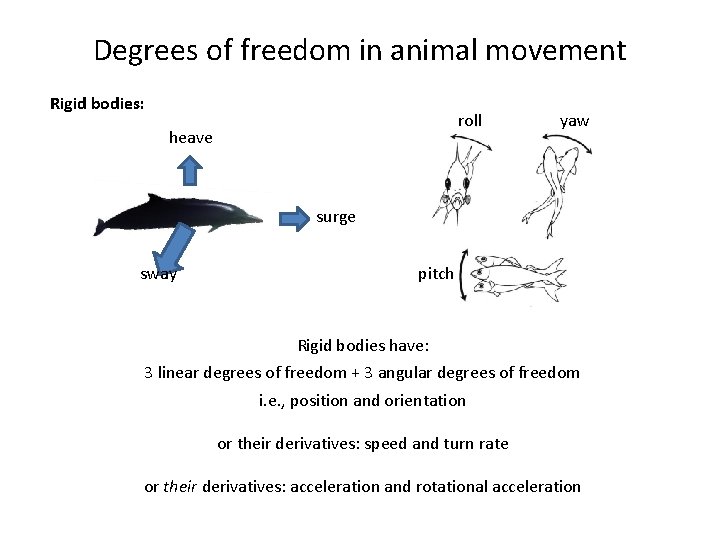

Degrees of freedom in animal movement Rigid bodies: roll heave yaw surge sway pitch Rigid bodies have: 3 linear degrees of freedom + 3 angular degrees of freedom i. e. , position and orientation or their derivatives: speed and turn rate or their derivatives: acceleration and rotational acceleration

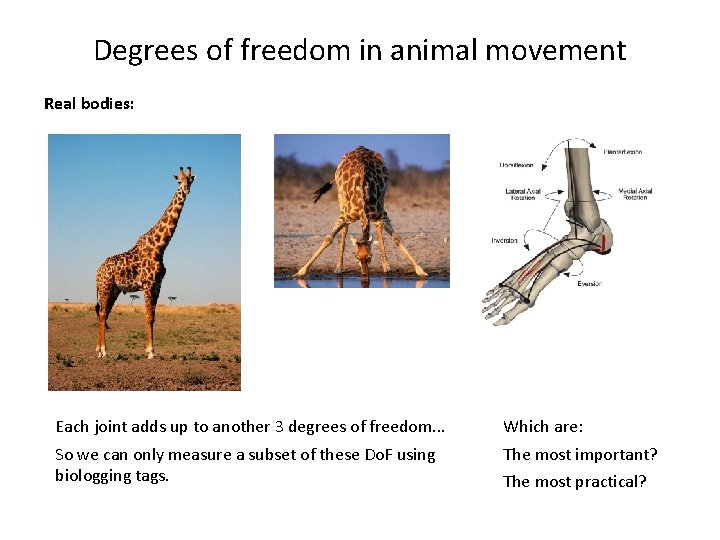

Degrees of freedom in animal movement Real bodies: Each joint adds up to another 3 degrees of freedom. . . Which are: So we can only measure a subset of these Do. F using biologging tags. The most important? The most practical?

Biologging sensors for animal movement Pressure (depth, altitude) Measures the deflection of a membrane with pressure on one side and vacuum on the other. Accelerometer (orientation, activity) Measures the total force in 3 dimensions acting on a suspended mass. Magnetometer (heading, orientation) Measures the total magnetic field in 3 dimensions. GPS (position) Measures position from the travel time of radio signals from satellites. Speed (turbine or propeller) Measures speed in one direction with respect to the surrounding medium. Gyroscope (orientation) Measures the turning rate around 3 axes.

Biologging sensors for animal movement piggybacking on mass-market sensors The big enabler: MEMS (Micro-Electro-Mechanical-Systems) is a way to make a sensor on a chip. . . → small size, low cost, low power

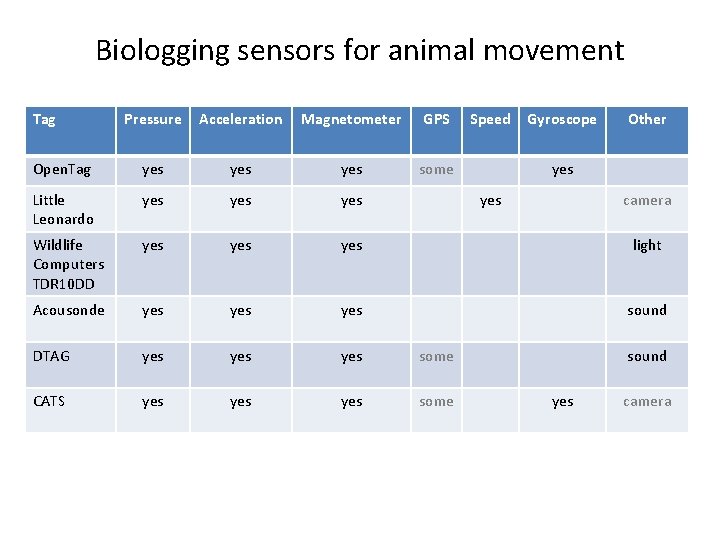

Biologging sensors for animal movement Tag Pressure Acceleration Magnetometer GPS Speed Gyroscope Other Open. Tag yes yes some Little Leonardo yes yes Wildlife Computers TDR 10 DD yes yes light Acousonde yes yes sound DTAG yes yes some CATS yes yes some yes camera sound yes camera

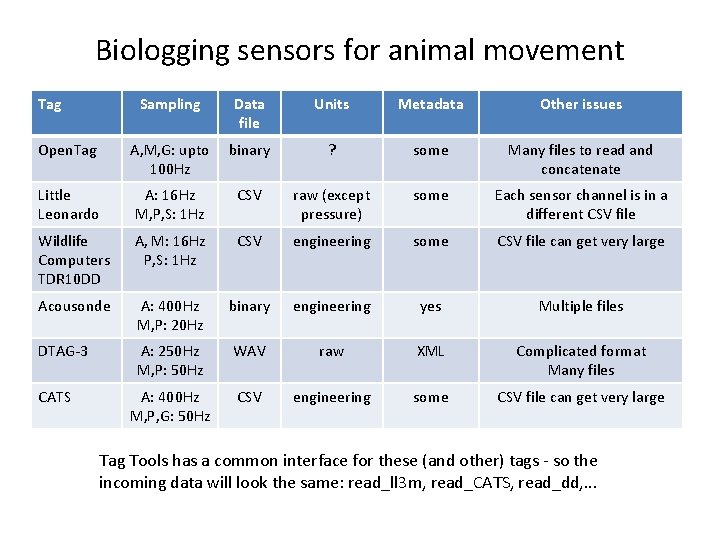

Biologging sensors for animal movement Tag Sampling Open. Tag Data file A, M, G: upto binary 100 Hz Units Metadata Other issues ? some Many files to read and concatenate Little Leonardo A: 16 Hz M, P, S: 1 Hz CSV raw (except pressure) some Each sensor channel is in a different CSV file Wildlife Computers TDR 10 DD A, M: 16 Hz P, S: 1 Hz CSV engineering some CSV file can get very large Acousonde A: 400 Hz M, P: 20 Hz binary engineering yes Multiple files DTAG-3 A: 250 Hz M, P: 50 Hz WAV raw XML Complicated format Many files A: 400 Hz M, P, G: 50 Hz CSV engineering some CSV file can get very large CATS Tag Tools has a common interface for these (and other) tags - so the incoming data will look the same: read_ll 3 m, read_CATS, read_dd, . . .

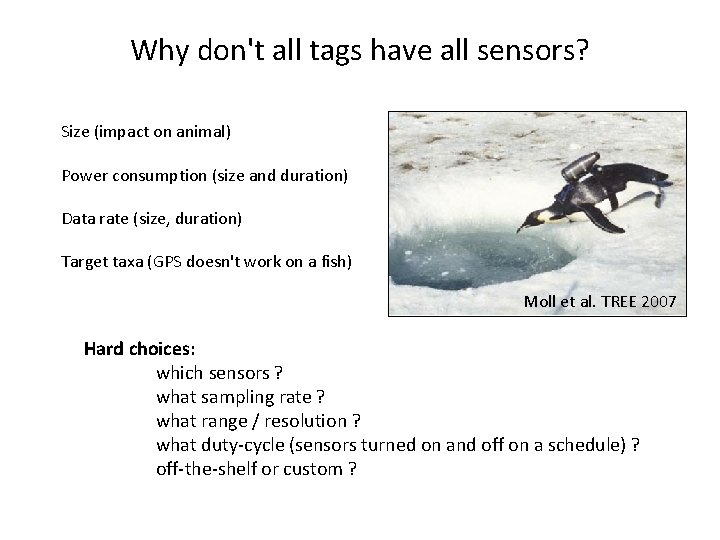

Why don't all tags have all sensors? Size (impact on animal) Power consumption (size and duration) Data rate (size, duration) Target taxa (GPS doesn't work on a fish) Moll et al. TREE 2007 Hard choices: which sensors ? what sampling rate ? what range / resolution ? what duty-cycle (sensors turned on and off on a schedule) ? off-the-shelf or custom ?

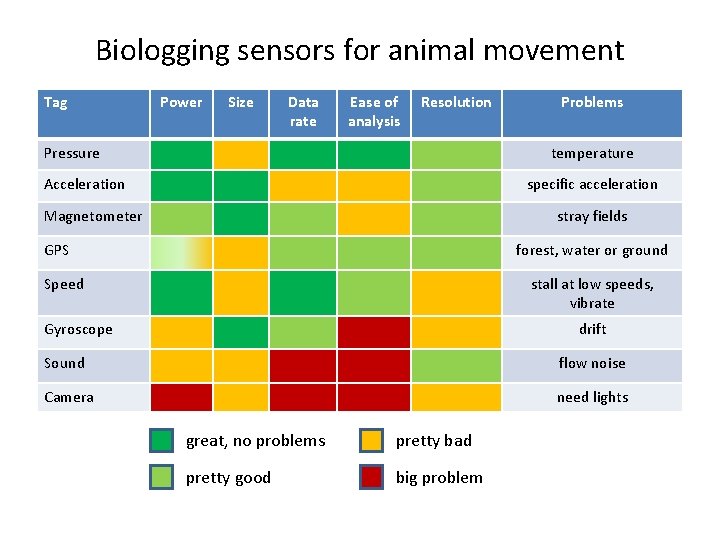

Biologging sensors for animal movement Tag Power Size Data rate Ease of analysis Resolution Pressure Problems temperature Acceleration specific acceleration Magnetometer stray fields GPS forest, water or ground Speed stall at low speeds, vibrate Gyroscope drift Sound flow noise Camera need lights great, no problems pretty bad pretty good big problem

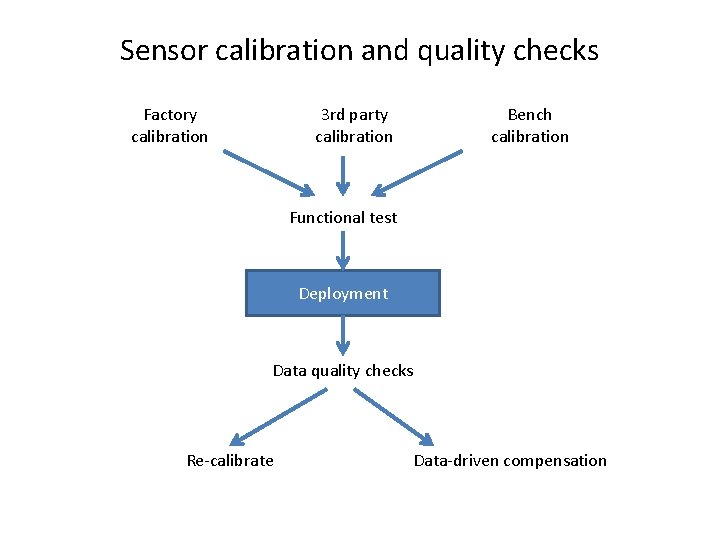

Sensor calibration and quality checks Factory calibration 3 rd party calibration Bench calibration Functional test Deployment Data quality checks Re-calibrate Data-driven compensation

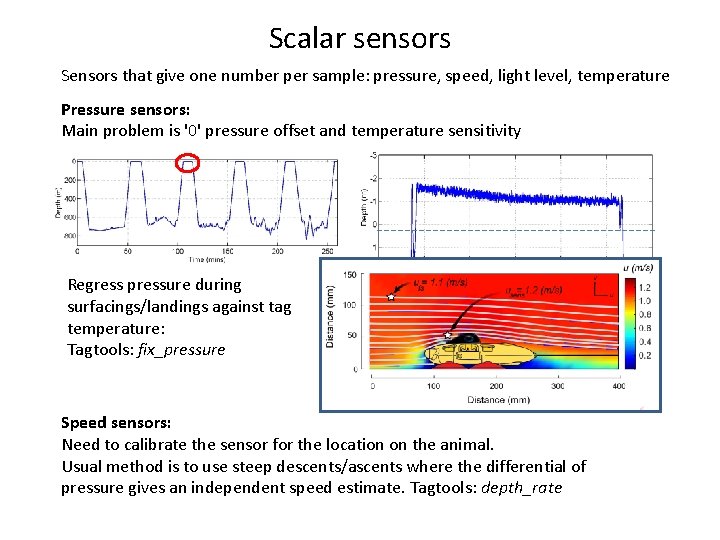

Scalar sensors Sensors that give one number per sample: pressure, speed, light level, temperature Pressure sensors: Main problem is '0' pressure offset and temperature sensitivity Regress pressure during surfacings/landings against tag temperature: Tagtools: fix_pressure Speed sensors: Need to calibrate the sensor for the location on the animal. Usual method is to use steep descents/ascents where the differential of pressure gives an independent speed estimate. Tagtools: depth_rate

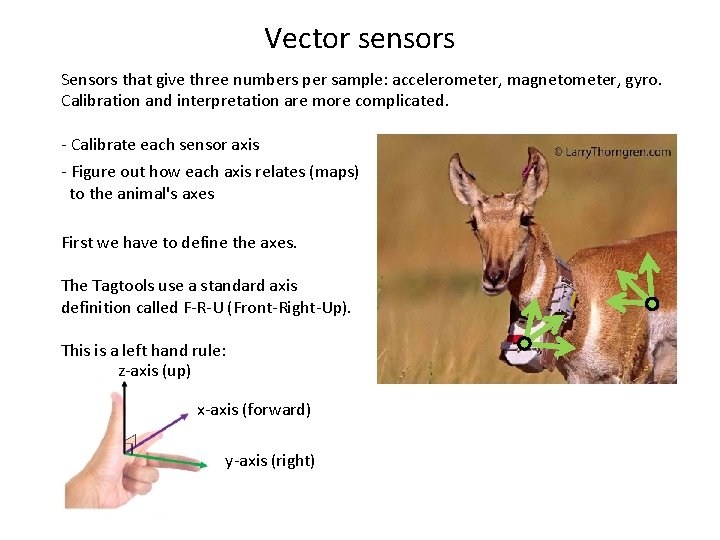

Vector sensors Sensors that give three numbers per sample: accelerometer, magnetometer, gyro. Calibration and interpretation are more complicated. - Calibrate each sensor axis - Figure out how each axis relates (maps) to the animal's axes First we have to define the axes. The Tagtools use a standard axis definition called F-R-U (Front-Right-Up). This is a left hand rule: z-axis (up) x-axis (forward) y-axis (right)

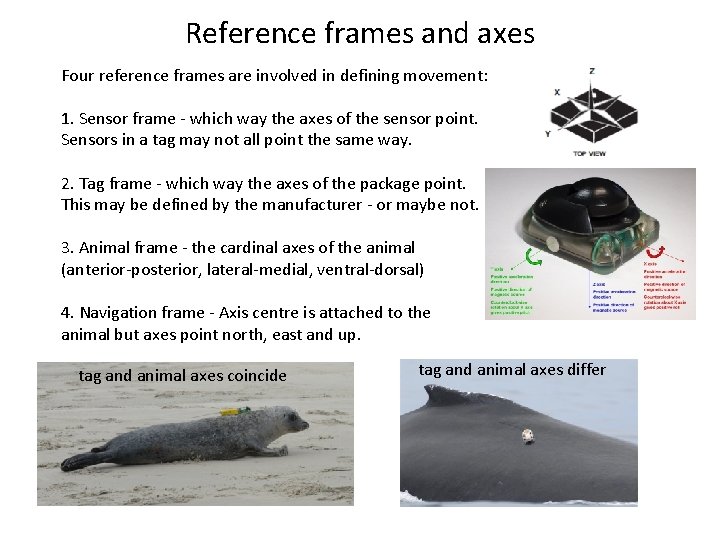

Reference frames and axes Four reference frames are involved in defining movement: 1. Sensor frame - which way the axes of the sensor point. Sensors in a tag may not all point the same way. 2. Tag frame - which way the axes of the package point. This may be defined by the manufacturer - or maybe not. 3. Animal frame - the cardinal axes of the animal (anterior-posterior, lateral-medial, ventral-dorsal) 4. Navigation frame - Axis centre is attached to the animal but axes point north, east and up. tag and animal axes coincide tag and animal axes differ

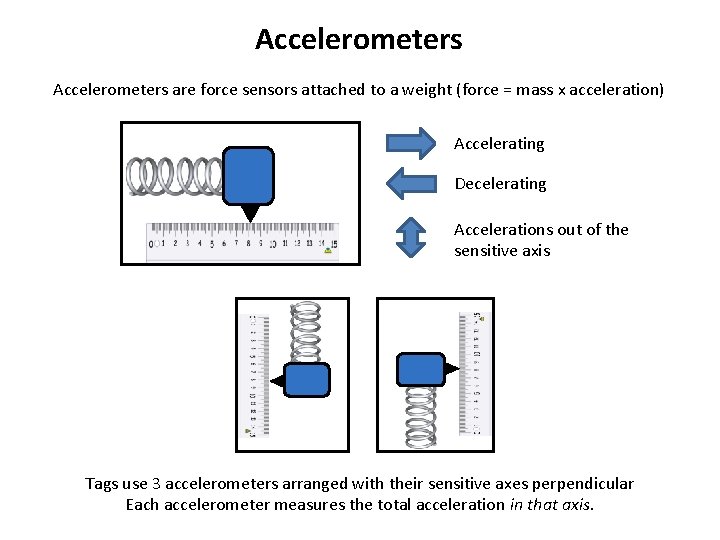

Accelerometers are force sensors attached to a weight (force = mass x acceleration) Accelerating Decelerating Accelerations out of the sensitive axis Tags use 3 accelerometers arranged with their sensitive axes perpendicular Each accelerometer measures the total acceleration in that axis.

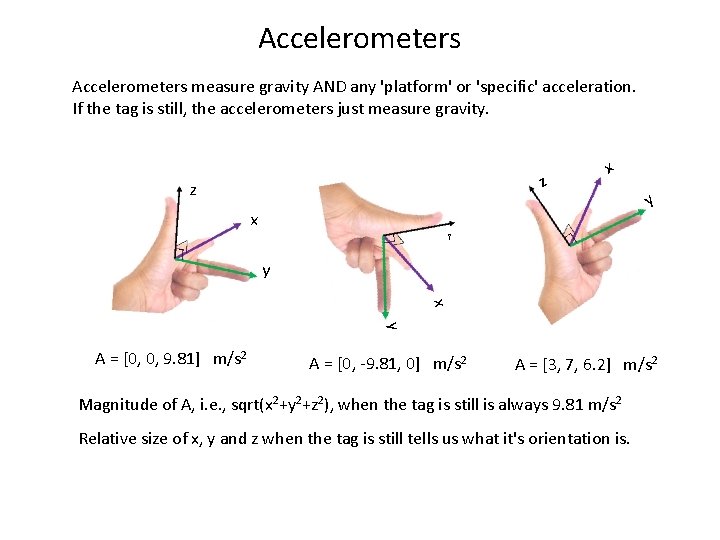

Accelerometers measure gravity AND any 'platform' or 'specific' acceleration. If the tag is still, the accelerometers just measure gravity. z z x x y z y x y A = [0, 0, 9. 81] m/s 2 A = [0, -9. 81, 0] m/s 2 A = [3, 7, 6. 2] m/s 2 Magnitude of A, i. e. , sqrt(x 2+y 2+z 2), when the tag is still is always 9. 81 m/s 2 Relative size of x, y and z when the tag is still tells us what it's orientation is.

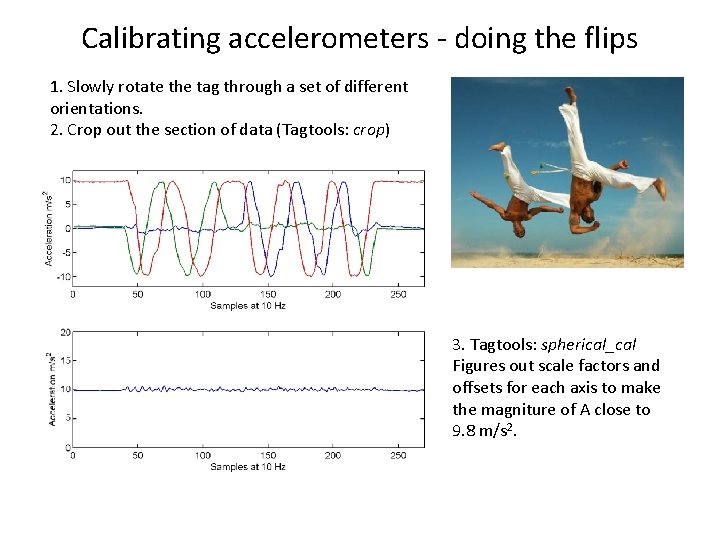

Calibrating accelerometers - doing the flips 1. Slowly rotate the tag through a set of different orientations. 2. Crop out the section of data (Tagtools: crop) 3. Tagtools: spherical_cal Figures out scale factors and offsets for each axis to make the magniture of A close to 9. 8 m/s 2.

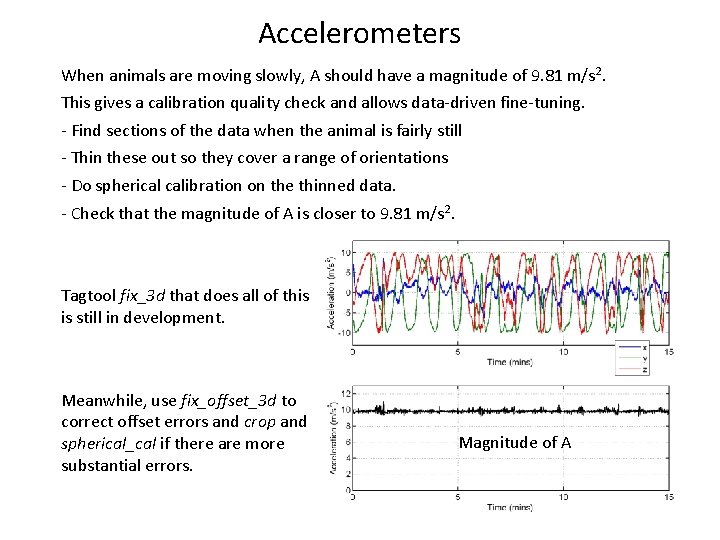

Accelerometers When animals are moving slowly, A should have a magnitude of 9. 81 m/s 2. This gives a calibration quality check and allows data-driven fine-tuning. - Find sections of the data when the animal is fairly still - Thin these out so they cover a range of orientations - Do spherical calibration on the thinned data. - Check that the magnitude of A is closer to 9. 81 m/s 2. Tagtool fix_3 d that does all of this is still in development. Meanwhile, use fix_offset_3 d to correct offset errors and crop and spherical_cal if there are more substantial errors. Magnitude of A

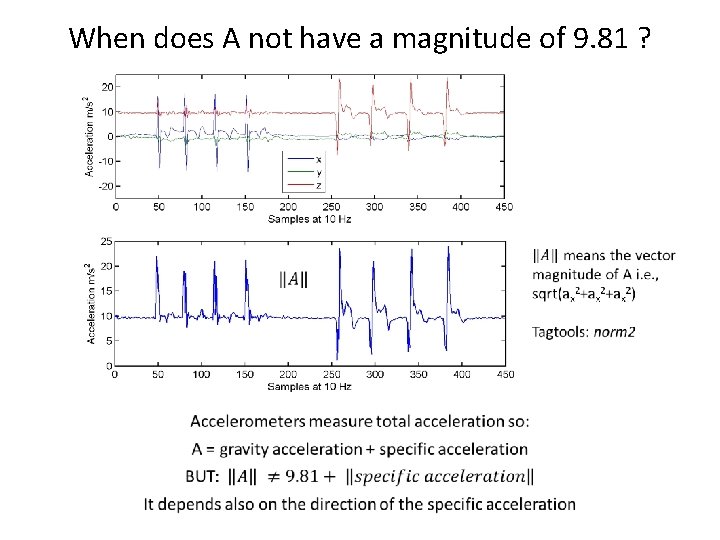

When does A not have a magnitude of 9. 81 ?

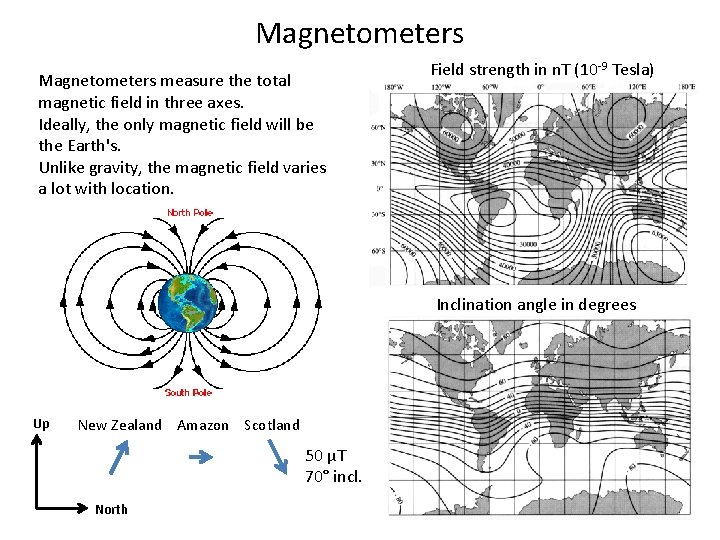

Magnetometers measure the total magnetic field in three axes. Ideally, the only magnetic field will be the Earth's. Unlike gravity, the magnetic field varies a lot with location. Field strength in n. T (10 -9 Tesla) Inclination angle in degrees Up New Zealand Amazon Scotland 50 µT 70° incl. North

Magnetometer sensitivity Three calibration problems with magnetometers: Hard iron: Magnetometers are sensitive to any magnetic field held by metal components in the tag, e. g. , nickel plated wires on electronic components, magnets in speed sensors. Soft iron: Even non-magnetized metal in the tag can warp the Earth's magnetic field and make it seem like it comes from a different direction, e. g. , stainless steel pressure sensors. Non-linearity: Magnets used to turn tags on/off can cause saturation or reduce sensitivity. Effect persists until magnetometer is degaussed. Seems to happen much less with newer Hall effect sensors.

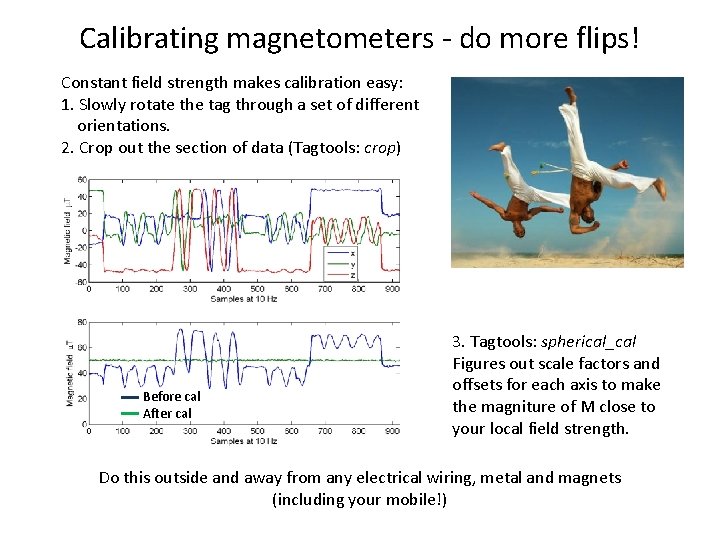

Calibrating magnetometers - do more flips! Constant field strength makes calibration easy: 1. Slowly rotate the tag through a set of different orientations. 2. Crop out the section of data (Tagtools: crop) Before cal After cal 3. Tagtools: spherical_cal Figures out scale factors and offsets for each axis to make the magniture of M close to your local field strength. Do this outside and away from any electrical wiring, metal and magnets (including your mobile!)

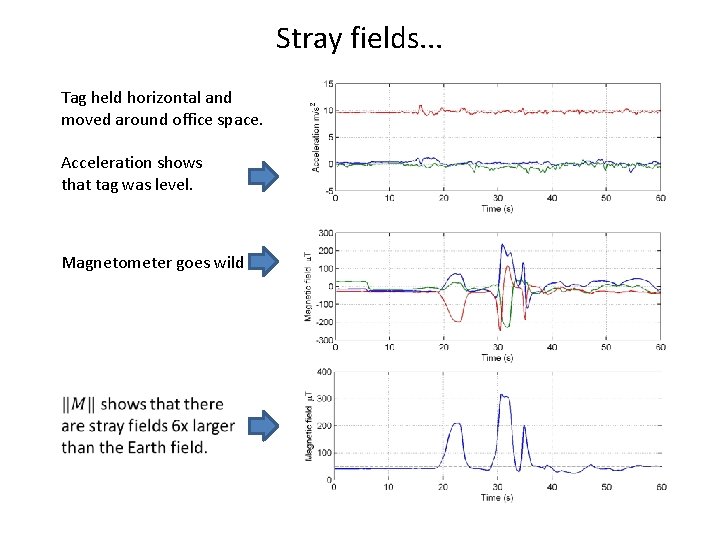

Stray fields. . . Tag held horizontal and moved around office space. Acceleration shows that tag was level. Magnetometer goes wild

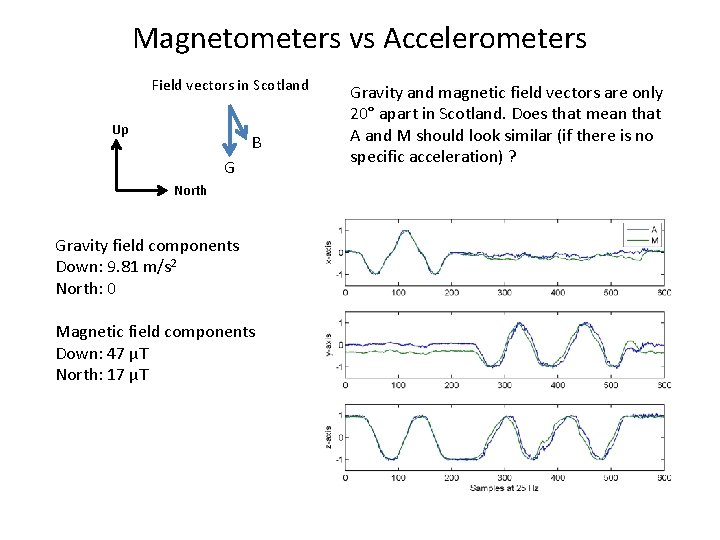

Magnetometers vs Accelerometers Field vectors in Scotland Up B G North Gravity field components Down: 9. 81 m/s 2 North: 0 Magnetic field components Down: 47 µT North: 17 µT Gravity and magnetic field vectors are only 20° apart in Scotland. Does that mean that A and M should look similar (if there is no specific acceleration) ?

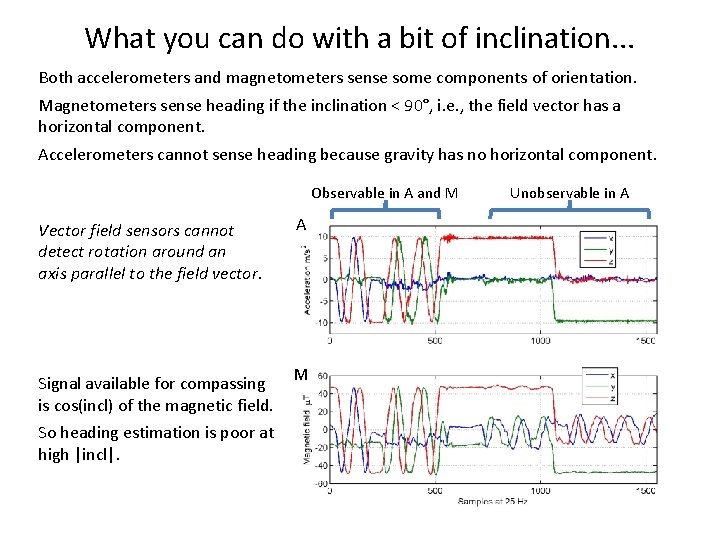

What you can do with a bit of inclination. . . Both accelerometers and magnetometers sense some components of orientation. Magnetometers sense heading if the inclination < 90°, i. e. , the field vector has a horizontal component. Accelerometers cannot sense heading because gravity has no horizontal component. Observable in A and M Vector field sensors cannot detect rotation around an axis parallel to the field vector. A Signal available for compassing is cos(incl) of the magnetic field. M So heading estimation is poor at high |incl|. Unobservable in A

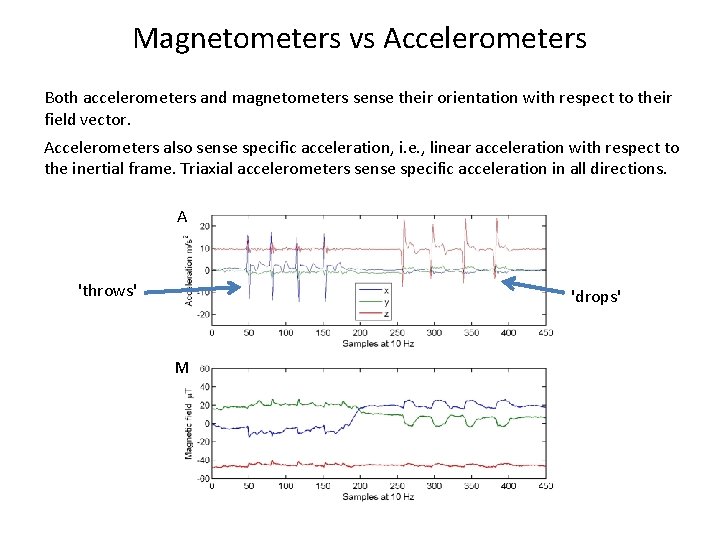

Magnetometers vs Accelerometers Both accelerometers and magnetometers sense their orientation with respect to their field vector. Accelerometers also sense specific acceleration, i. e. , linear acceleration with respect to the inertial frame. Triaxial accelerometers sense specific acceleration in all directions. A 'throws' 'drops' M

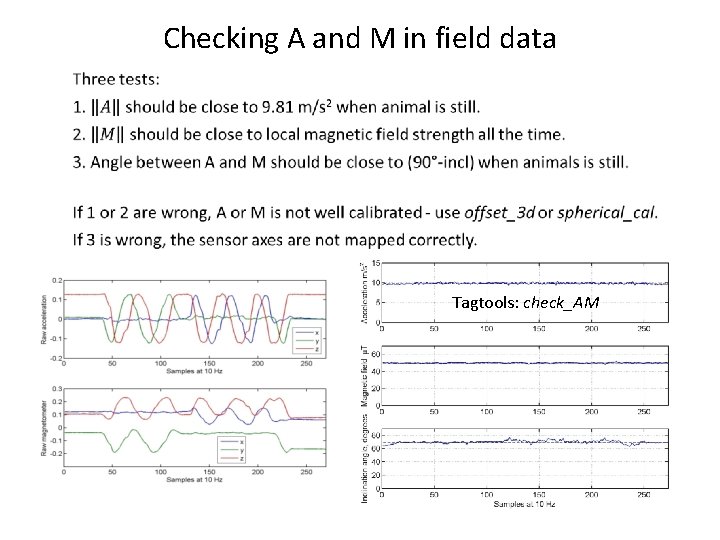

Checking A and M in field data Tagtools: check_AM

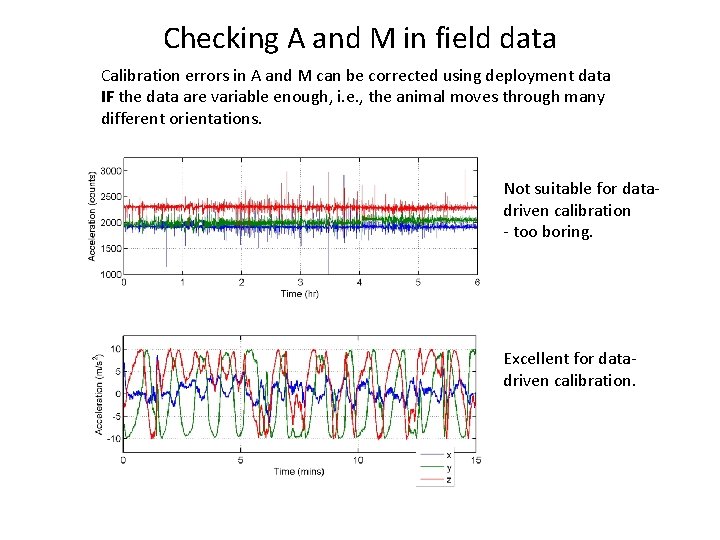

Checking A and M in field data Calibration errors in A and M can be corrected using deployment data IF the data are variable enough, i. e. , the animal moves through many different orientations. Not suitable for datadriven calibration - too boring. Excellent for datadriven calibration.

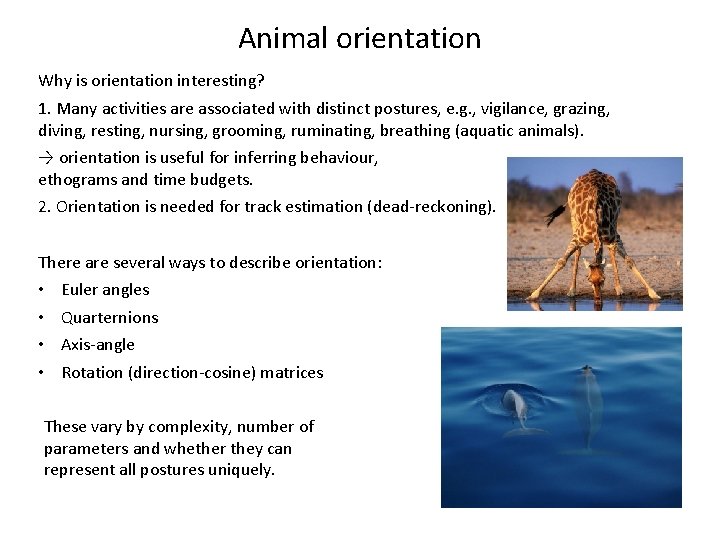

Animal orientation Why is orientation interesting? 1. Many activities are associated with distinct postures, e. g. , vigilance, grazing, diving, resting, nursing, grooming, ruminating, breathing (aquatic animals). → orientation is useful for inferring behaviour, ethograms and time budgets. 2. Orientation is needed for track estimation (dead-reckoning). There are several ways to describe orientation: • • Euler angles Quarternions Axis-angle Rotation (direction-cosine) matrices These vary by complexity, number of parameters and whether they can represent all postures uniquely.

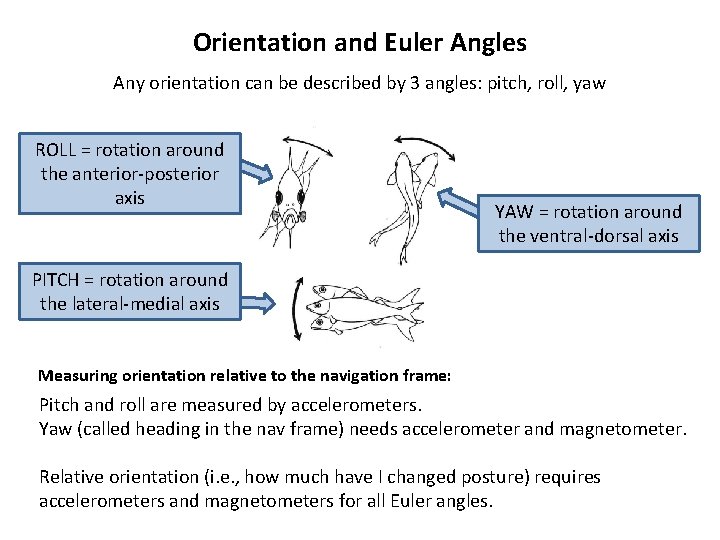

Orientation and Euler Angles Any orientation can be described by 3 angles: pitch, roll, yaw ROLL = rotation around the anterior-posterior axis YAW = rotation around the ventral-dorsal axis PITCH = rotation around the lateral-medial axis Measuring orientation relative to the navigation frame: Pitch and roll are measured by accelerometers. Yaw (called heading in the nav frame) needs accelerometer and magnetometer. Relative orientation (i. e. , how much have I changed posture) requires accelerometers and magnetometers for all Euler angles.

The pros and cons of Euler angles The good. . . Compact representation: only three numbers (rotation matrices have 9). Intuitive: pitch, roll and yaw rotations are easy to visualize. Biologically meaningful: animals have characteristic axes and use distinct muscles to pitch, roll and yaw. The bad. . . Orientation descriptions are not unique: heading 20°, pitch -120° = heading 200°, pitch -60° Problem solved by constraining pitch to within ± 90°. Gimbal lock: there is no solution for roll and heading when pitch = ± 90°. Roll and heading are unreliable when pitch is close to ± 90° e. g, aquatic animals diving steeply. Order of rotation matters: Tagtools convention is yaw-pitch-roll when going from navigation frame to animal frame, i. e. , when describing absolute orientation.

![Calculating Euler angles Tagtools: a 2 pr and m 2 h [pitch, roll] = Calculating Euler angles Tagtools: a 2 pr and m 2 h [pitch, roll] =](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/09cbaa78c404c0ff170c354c0dc920ed/image-31.jpg)

Calculating Euler angles Tagtools: a 2 pr and m 2 h [pitch, roll] = a 2 pr(A) heading = m 2 h(M, A) But the outcome depends on the frame of A and M. If the tag axis coincide with the animal axes, the orientation is also for the animal. If not, you first have to convert A and M to the animal frame. This requires an estimate of the pitch, roll and yaw of the tag on the animal. Can be estimated from photos.

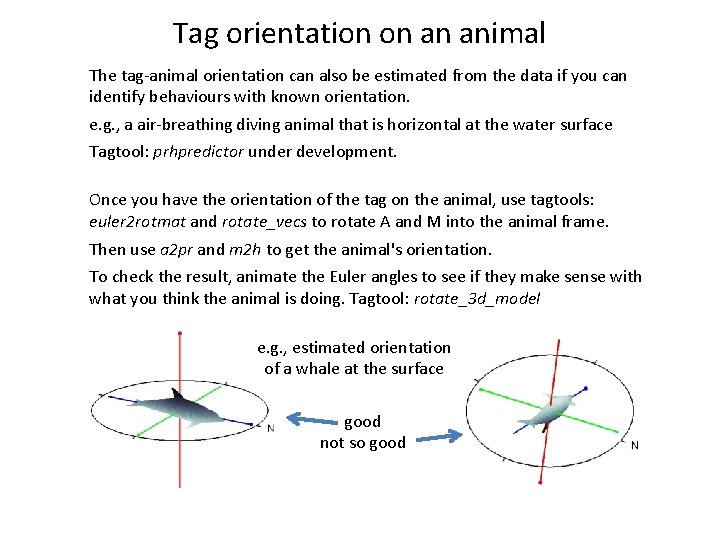

Tag orientation on an animal The tag-animal orientation can also be estimated from the data if you can identify behaviours with known orientation. e. g. , a air-breathing diving animal that is horizontal at the water surface Tagtool: prhpredictor under development. Once you have the orientation of the tag on the animal, use tagtools: euler 2 rotmat and rotate_vecs to rotate A and M into the animal frame. Then use a 2 pr and m 2 h to get the animal's orientation. To check the result, animate the Euler angles to see if they make sense with what you think the animal is doing. Tagtool: rotate_3 d_model e. g. , estimated orientation of a whale at the surface good not so good

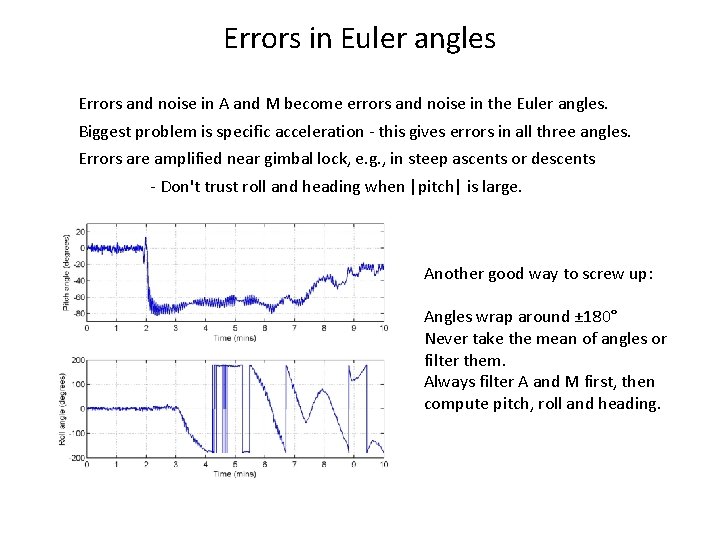

Errors in Euler angles Errors and noise in A and M become errors and noise in the Euler angles. Biggest problem is specific acceleration - this gives errors in all three angles. Errors are amplified near gimbal lock, e. g. , in steep ascents or descents - Don't trust roll and heading when |pitch| is large. Another good way to screw up: Angles wrap around ± 180° Never take the mean of angles or filter them. Always filter A and M first, then compute pitch, roll and heading.

Gyroscopes measure turn rate i. e. , d(pitch)/dt , d(roll)/dt, d(yaw)/dt Why not just integrate the gyroscope signals to get pitch, roll and yaw? Gyroscopes take more power than accelerometers and magnetometers because they require a moving mass. Gyroscopes have no absolute reference so you need to know the pitch, roll and yaw at least once to start the integration. Therefore you need accelerometers and magnetometers anyway. Offset errors (from miscalibration, temperature and drift) accumulate in the integration - animals seem to be rotating slowly all the time! Solution is to estimate and remove the drift with a Kalman filter - much more complex processing. The complete set of sensors (accelerometer, magnetometer and gyroscope) together with Kalman filter processing is termed an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU).

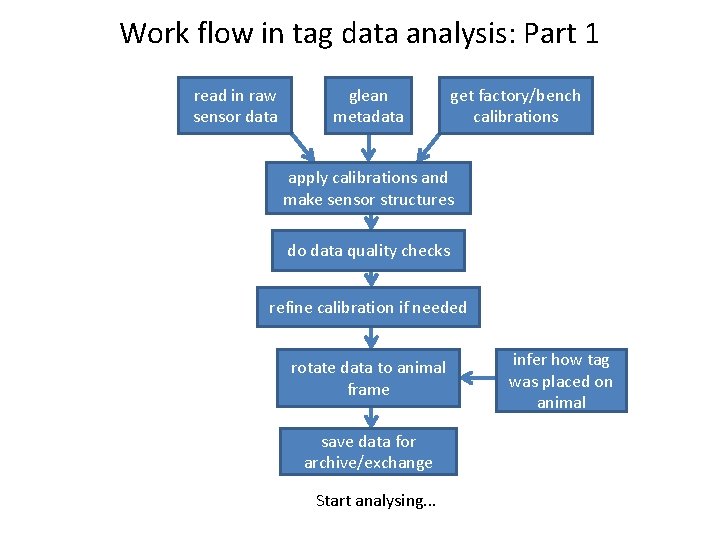

Work flow in tag data analysis: Part 1 read in raw sensor data glean metadata get factory/bench calibrations apply calibrations and make sensor structures do data quality checks refine calibration if needed rotate data to animal frame save data for archive/exchange Start analysing. . . infer how tag was placed on animal

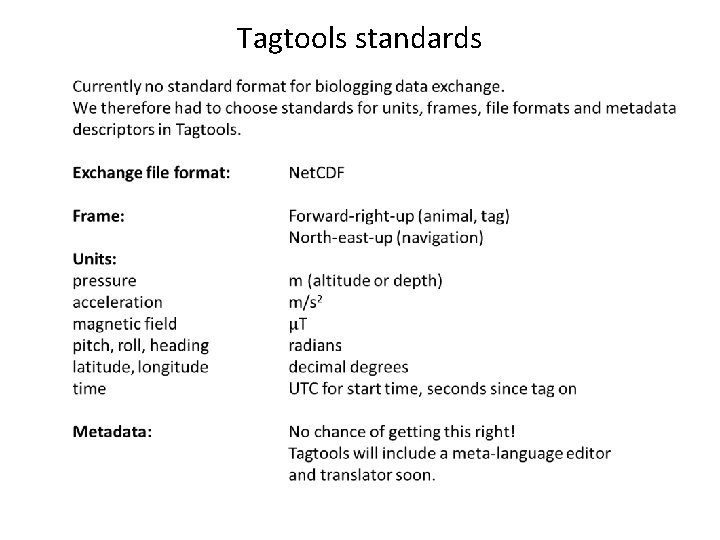

Tagtools standards

- Slides: 36