SEGMENTATION AND EQUIVALENCE CLASSES IN LARGE VOCABULARY CONTINUOUS

SEGMENTATION AND EQUIVALENCE CLASSES IN LARGE VOCABULARY CONTINUOUS SPEECH RECOGNITION Paul De Palma Ph. D. Candidate Department of Linguistics University of New Mexico Slides At: www. cs. gonzaga. edu/depalma 1

An Engineering Artifact � Segments � Instead of syllables � No claim about faithfulness to human language � Equivalence classes � Instead of concepts � No claim about cognition � LVCSR Systems � Vocabularies of 20 -60, 000 words � Continuous speech � Multiple speakers

A Motivational Observation � The consensus view in ASR research “The goal of automatic speech recognition (ASR) is to … [build] systems that map from an acoustic signal to a string of words” (Jurafsky & Martin, 2000, p. 235).

Implication Map => A functional relationship between speech and writing Roughly Language is writing

Back in the World of Human Speech We can (at best) paraphrase our conversational partner. Mostly, this is good enough.

The Art of the Quote � Faux quote from the NY Times � “We have never seen anything like this in our history. Even the British colonial rule, they stopped chasing people around when they ran into a monastery. ” � Hand-transcribed quote from the Buckeye Corpus � yes <VOCNOISE> i uh <SIL> um <SIL> uh <VOCNOISE> lordy <VOCNOISE> um <VOCNOISE> grew up on the westside i went to <EXCLUDE-name> my husband went to <EXCLUDEname> um <SIL> proximity wise is probably within a mile of each other we were kind of high school sweethearts and <VOCNOISE> the whole bit <SIL> um <VOCNOISE> his dad still lives in grove city my mom lives still <SIL> at our old family house there on the westside <VOCNOISE> and we moved <SIL> um <SIL> also on the westside probably couple miles from my mom

Working Hypotheses We can develop more robust LVCSR systems if we use A segmentation scheme 2. Equivalence classes 1. Which will produce an approximation (we hope accurate) of the original utterance Price: the output is not human-readable

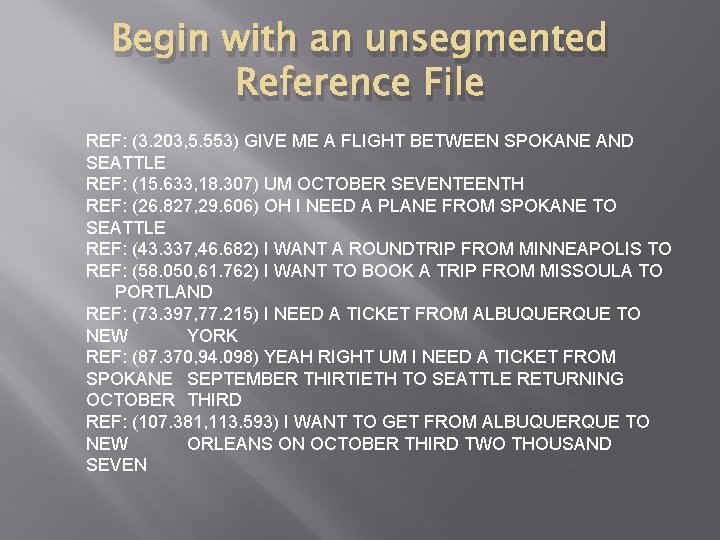

Begin with an unsegmented Reference File REF: (3. 203, 5. 553) GIVE ME A FLIGHT BETWEEN SPOKANE AND SEATTLE REF: (15. 633, 18. 307) UM OCTOBER SEVENTEENTH REF: (26. 827, 29. 606) OH I NEED A PLANE FROM SPOKANE TO SEATTLE REF: (43. 337, 46. 682) I WANT A ROUNDTRIP FROM MINNEAPOLIS TO REF: (58. 050, 61. 762) I WANT TO BOOK A TRIP FROM MISSOULA TO PORTLAND REF: (73. 397, 77. 215) I NEED A TICKET FROM ALBUQUERQUE TO NEW YORK REF: (87. 370, 94. 098) YEAH RIGHT UM I NEED A TICKET FROM SPOKANE SEPTEMBER THIRTIETH TO SEATTLE RETURNING OCTOBER THIRD REF: (107. 381, 113. 593) I WANT TO GET FROM ALBUQUERQUE TO NEW ORLEANS ON OCTOBER THIRD TWO THOUSAND SEVEN

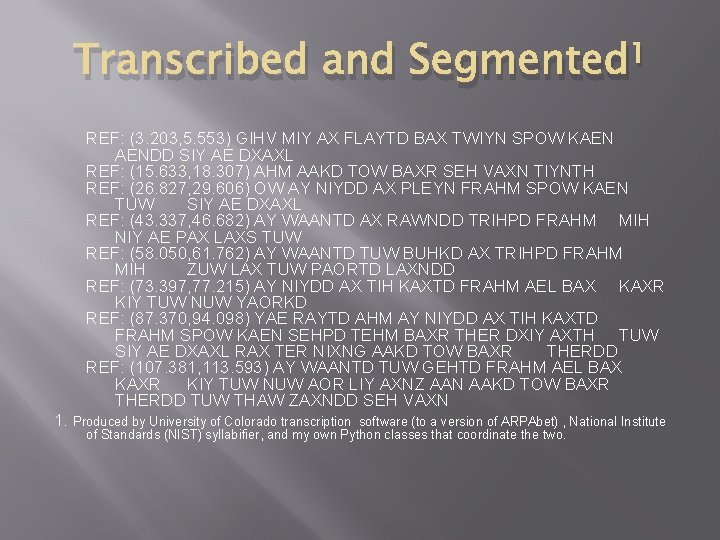

Transcribed and Segmented 1 REF: (3. 203, 5. 553) GIHV MIY AX FLAYTD BAX TWIYN SPOW KAEN AENDD SIY AE DXAXL REF: (15. 633, 18. 307) AHM AAKD TOW BAXR SEH VAXN TIYNTH REF: (26. 827, 29. 606) OW AY NIYDD AX PLEYN FRAHM SPOW KAEN TUW SIY AE DXAXL REF: (43. 337, 46. 682) AY WAANTD AX RAWNDD TRIHPD FRAHM MIH NIY AE PAX LAXS TUW REF: (58. 050, 61. 762) AY WAANTD TUW BUHKD AX TRIHPD FRAHM MIH ZUW LAX TUW PAORTD LAXNDD REF: (73. 397, 77. 215) AY NIYDD AX TIH KAXTD FRAHM AEL BAX KAXR KIY TUW NUW YAORKD REF: (87. 370, 94. 098) YAE RAYTD AHM AY NIYDD AX TIH KAXTD FRAHM SPOW KAEN SEHPD TEHM BAXR THER DXIY AXTH TUW SIY AE DXAXL RAX TER NIXNG AAKD TOW BAXR THERDD REF: (107. 381, 113. 593) AY WAANTD TUW GEHTD FRAHM AEL BAX KAXR KIY TUW NUW AOR LIY AXNZ AAN AAKD TOW BAXR THERDD TUW THAW ZAXNDD SEH VAXN 1. Produced by University of Colorado transcription software (to a version of ARPAbet) , National Institute of Standards (NIST) syllabifier, and my own Python classes that coordinate the two.

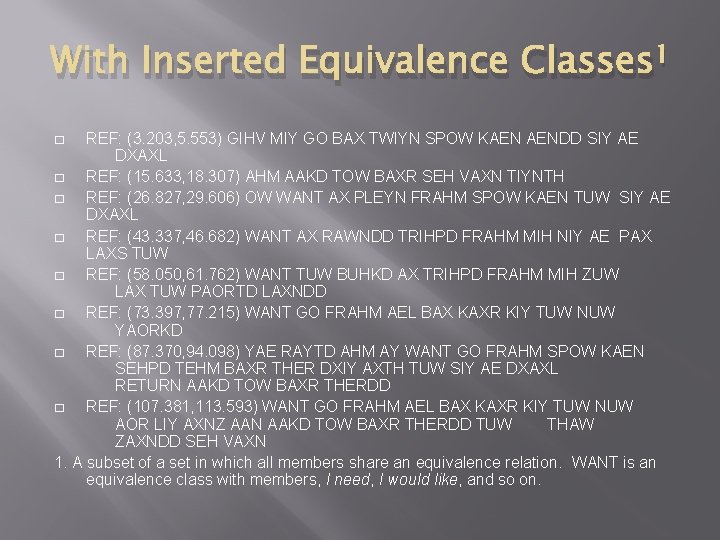

With Inserted Equivalence Classes 1 REF: (3. 203, 5. 553) GIHV MIY GO BAX TWIYN SPOW KAEN AENDD SIY AE DXAXL � REF: (15. 633, 18. 307) AHM AAKD TOW BAXR SEH VAXN TIYNTH � REF: (26. 827, 29. 606) OW WANT AX PLEYN FRAHM SPOW KAEN TUW SIY AE DXAXL � REF: (43. 337, 46. 682) WANT AX RAWNDD TRIHPD FRAHM MIH NIY AE PAX LAXS TUW � REF: (58. 050, 61. 762) WANT TUW BUHKD AX TRIHPD FRAHM MIH ZUW LAX TUW PAORTD LAXNDD � REF: (73. 397, 77. 215) WANT GO FRAHM AEL BAX KAXR KIY TUW NUW YAORKD � REF: (87. 370, 94. 098) YAE RAYTD AHM AY WANT GO FRAHM SPOW KAEN SEHPD TEHM BAXR THER DXIY AXTH TUW SIY AE DXAXL RETURN AAKD TOW BAXR THERDD � REF: (107. 381, 113. 593) WANT GO FRAHM AEL BAX KAXR KIY TUW NUW AOR LIY AXNZ AAN AAKD TOW BAXR THERDD TUW THAW ZAXNDD SEH VAXN 1. A subset of a set in which all members share an equivalence relation. WANT is an equivalence class with members, I need, I would like, and so on. �

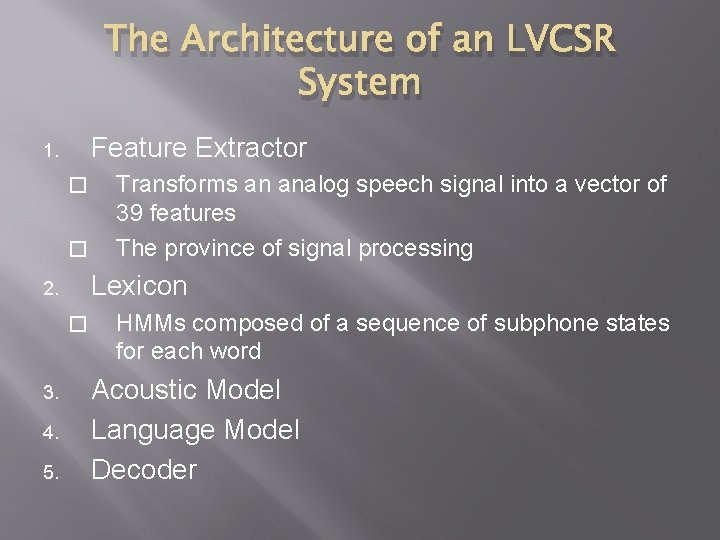

The Architecture of an LVCSR System Feature Extractor 1. � � Lexicon 2. � 3. 4. 5. Transforms an analog speech signal into a vector of 39 features The province of signal processing HMMs composed of a sequence of subphone states for each word Acoustic Model Language Model Decoder

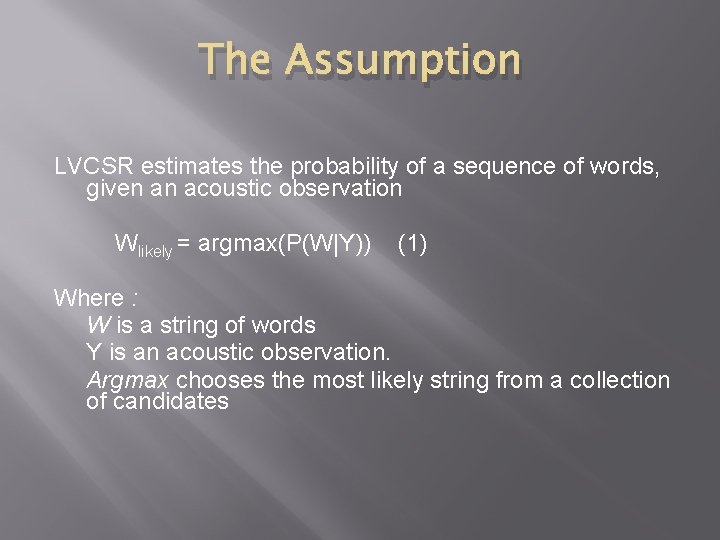

The Assumption LVCSR estimates the probability of a sequence of words, given an acoustic observation Wlikely = argmax(P(W|Y)) (1) Where : W is a string of words Y is an acoustic observation. Argmax chooses the most likely string from a collection of candidates

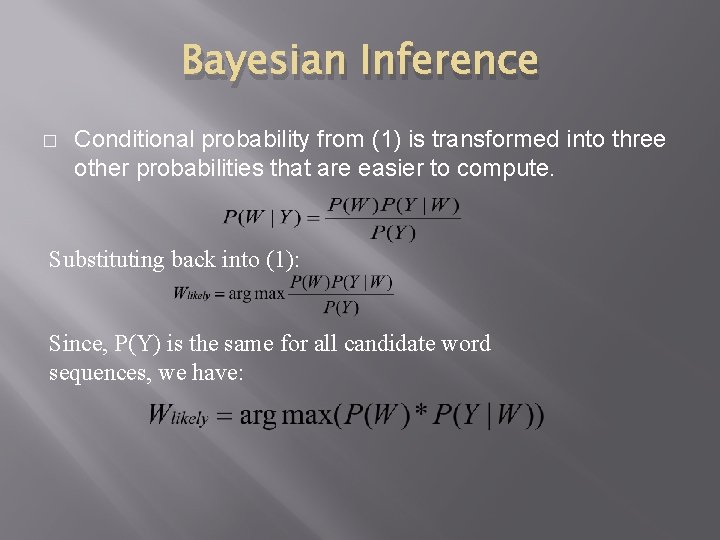

Bayesian Inference � Conditional probability from (1) is transformed into three other probabilities that are easier to compute. Substituting back into (1): Since, P(Y) is the same for all candidate word sequences, we have:

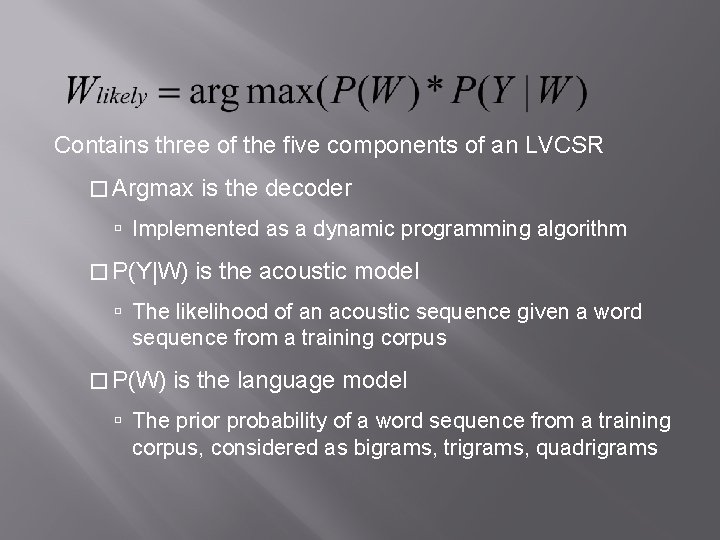

Contains three of the five components of an LVCSR � Argmax is the decoder Implemented as a dynamic programming algorithm � P(Y|W) is the acoustic model The likelihood of an acoustic sequence given a word sequence from a training corpus � P(W) is the language model The prior probability of a word sequence from a training corpus, considered as bigrams, trigrams, quadrigrams

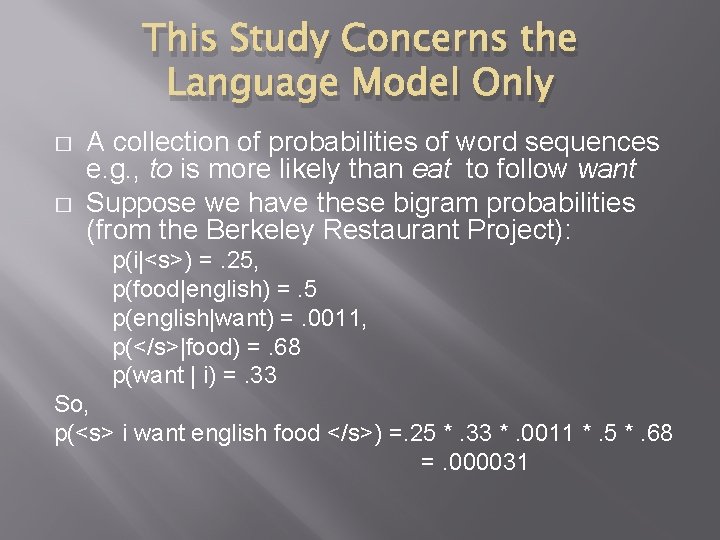

This Study Concerns the Language Model Only � � A collection of probabilities of word sequences e. g. , to is more likely than eat to follow want Suppose we have these bigram probabilities (from the Berkeley Restaurant Project): p(i|<s>) =. 25, p(food|english) =. 5 p(english|want) =. 0011, p(</s>|food) =. 68 p(want | i) =. 33 So, p(<s> i want english food </s>) =. 25 *. 33 *. 0011 *. 5 *. 68 =. 000031

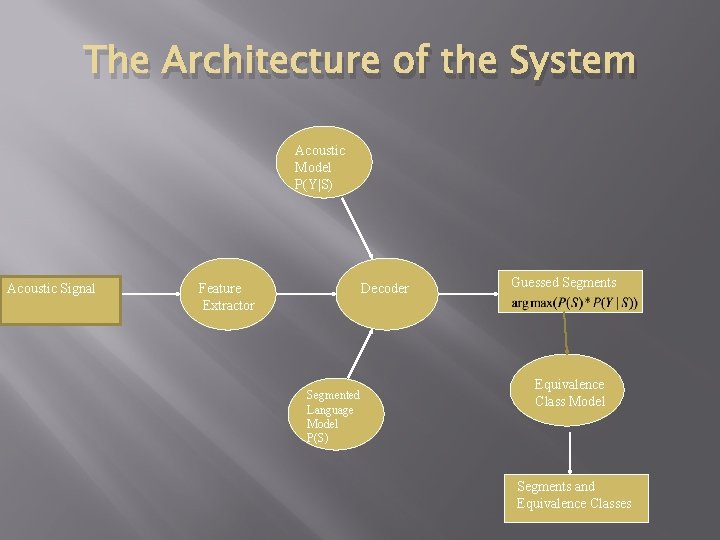

The Architecture of the System Acoustic Model P(Y|S) Acoustic Signal Feature Extractor Decoder Segmented Language Model P(S) Guessed Segments Equivalence Class Model Segments and Equivalence Classes

Four Experiments 1. 2. 3. 4. Perplexity: segmented language model WER: segmented language model constructed with stress markings WER: segmented language model and equivalence class model

Experiment 1: Perplexity � � Computes the inverse probability of randomly chosen word sequences Can be viewed as the weighted average branching factor of word sequences

Some Background � Perplexity is defined as the Nth inverse root of the probability that a language model assigns to a sequence of words: PP(W) = p(w 1 w 2…wn) -1/n where: W is a sequence of n words, w 1 w 2…wn � p(w 1 w 2…wn) is the probability that a language model assigns to that sequence � n is the number of words in the sequence �

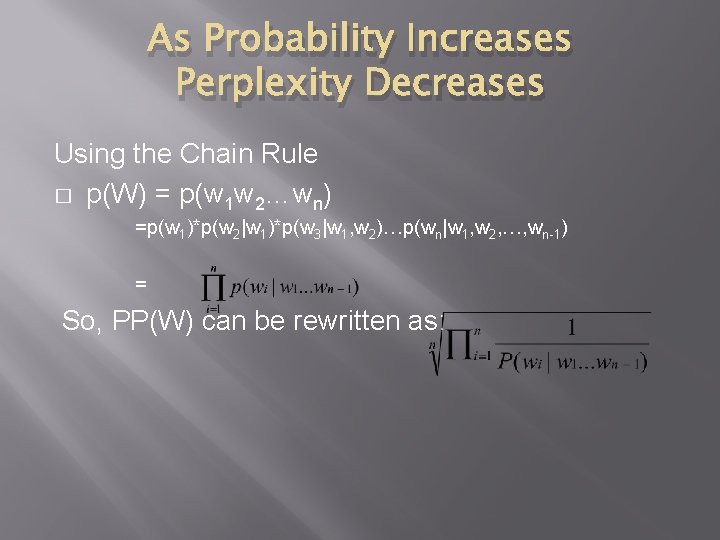

As Probability Increases Perplexity Decreases Using the Chain Rule � p(W) = p(w 1 w 2…wn) =p(w 1)*p(w 2|w 1)*p(w 3|w 1, w 2)…p(wn|w 1, w 2, …, wn-1) = So, PP(W) can be rewritten as:

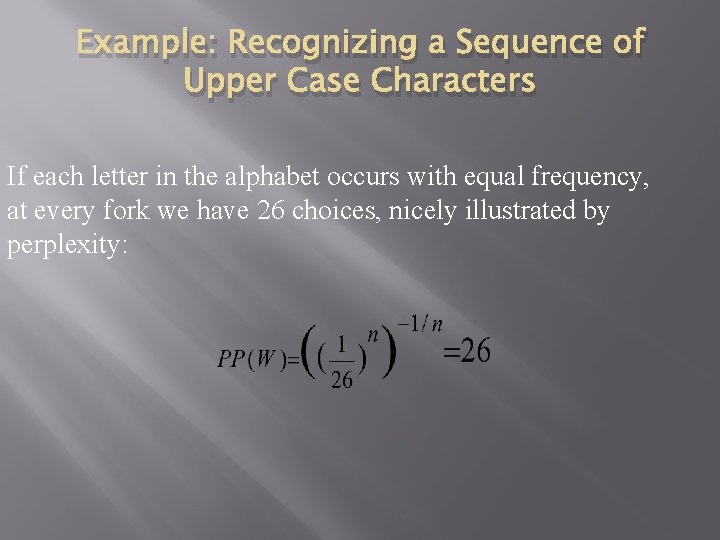

Example: Recognizing a Sequence of Upper Case Characters If each letter in the alphabet occurs with equal frequency, at every fork we have 26 choices, nicely illustrated by perplexity:

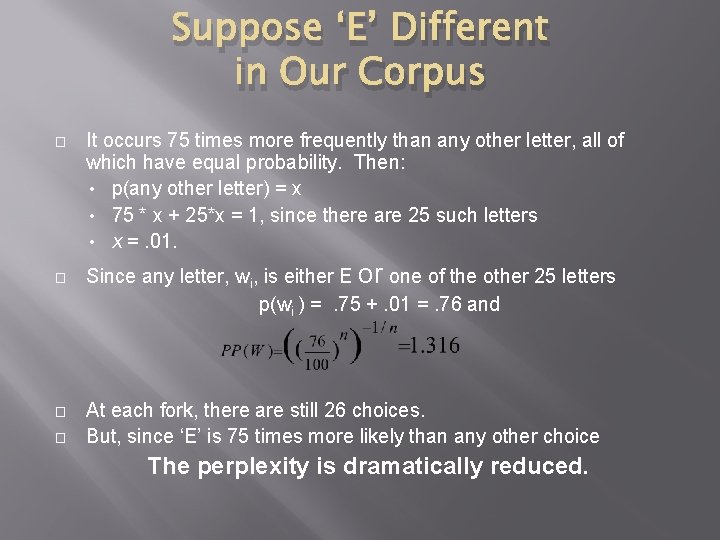

Suppose ‘E’ Different in Our Corpus � � It occurs 75 times more frequently than any other letter, all of which have equal probability. Then: • p(any other letter) = x • 75 * x + 25*x = 1, since there are 25 such letters • x =. 01. Since any letter, wi, is either E or one of the other 25 letters p(wi ) =. 75 +. 01 =. 76 and At each fork, there are still 26 choices. But, since ‘E’ is 75 times more likely than any other choice The perplexity is dramatically reduced.

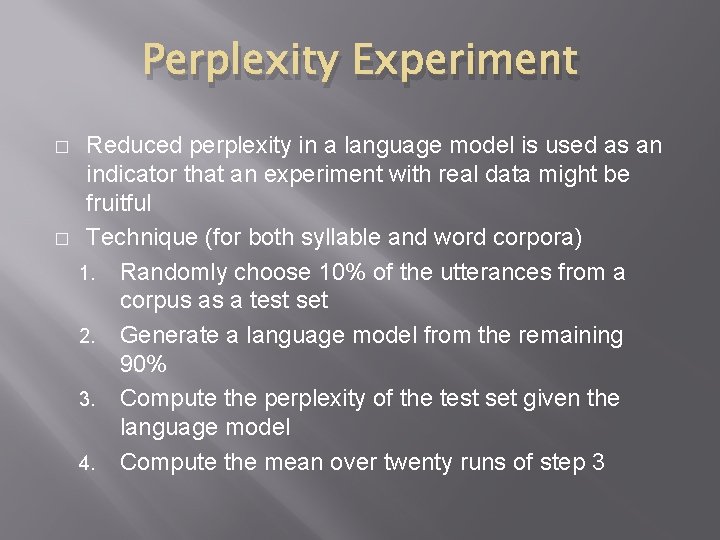

Perplexity Experiment � � Reduced perplexity in a language model is used as an indicator that an experiment with real data might be fruitful Technique (for both syllable and word corpora) 1. Randomly choose 10% of the utterances from a corpus as a test set 2. Generate a language model from the remaining 90% 3. Compute the perplexity of the test set given the language model 4. Compute the mean over twenty runs of step 3

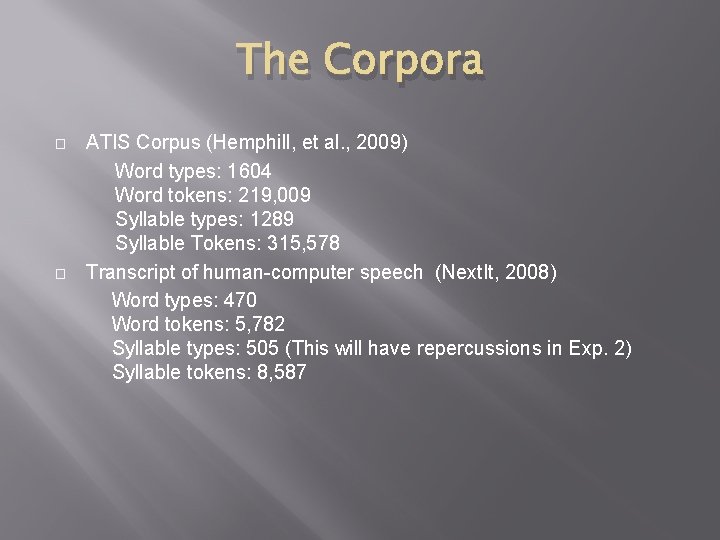

The Corpora � � ATIS Corpus (Hemphill, et al. , 2009) Word types: 1604 Word tokens: 219, 009 Syllable types: 1289 Syllable Tokens: 315, 578 Transcript of human-computer speech (Next. It, 2008) Word types: 470 Word tokens: 5, 782 Syllable types: 505 (This will have repercussions in Exp. 2) Syllable tokens: 8, 587

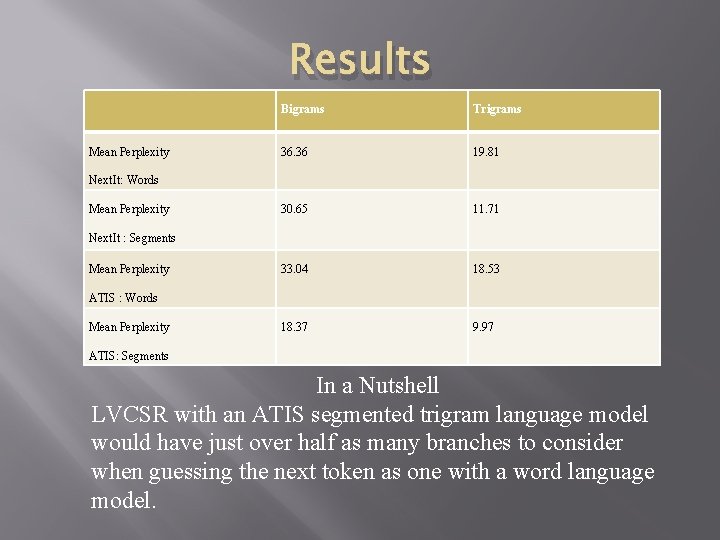

Results Mean Perplexity Bigrams Trigrams 36. 36 19. 81 30. 65 11. 71 33. 04 18. 53 18. 37 9. 97 Next. It: Words Mean Perplexity Next. It : Segments Mean Perplexity ATIS : Words Mean Perplexity ATIS: Segments In a Nutshell LVCSR with an ATIS segmented trigram language model would have just over half as many branches to consider when guessing the next token as one with a word language model.

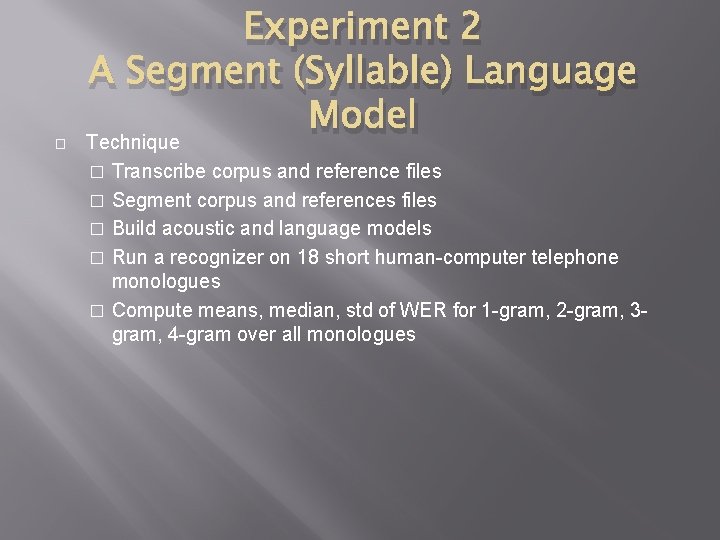

� Experiment 2 A Segment (Syllable) Language Model Technique Transcribe corpus and reference files � Segment corpus and references files � Build acoustic and language models � Run a recognizer on 18 short human-computer telephone monologues � Compute means, median, std of WER for 1 -gram, 2 -gram, 3 gram, 4 -gram over all monologues �

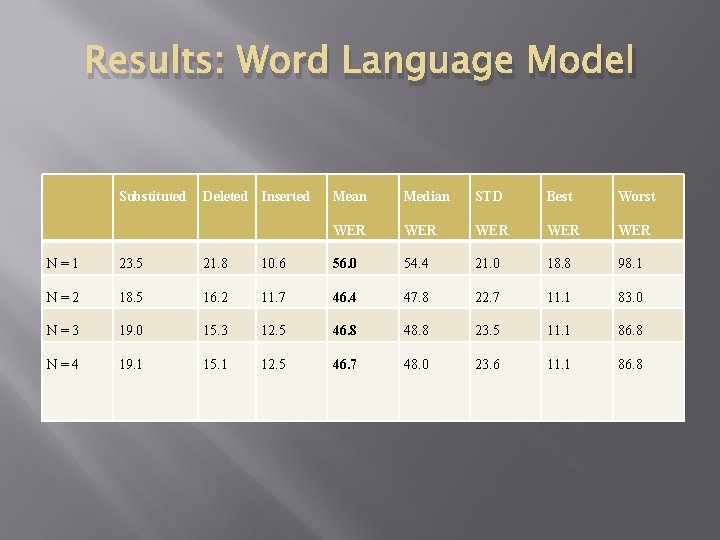

Results: Word Language Model Substituted Deleted Inserted Mean Median STD Best Worst WER WER WER N=1 23. 5 21. 8 10. 6 56. 0 54. 4 21. 0 18. 8 98. 1 N=2 18. 5 16. 2 11. 7 46. 4 47. 8 22. 7 11. 1 83. 0 N=3 19. 0 15. 3 12. 5 46. 8 48. 8 23. 5 11. 1 86. 8 N=4 19. 1 15. 1 12. 5 46. 7 48. 0 23. 6 11. 1 86. 8

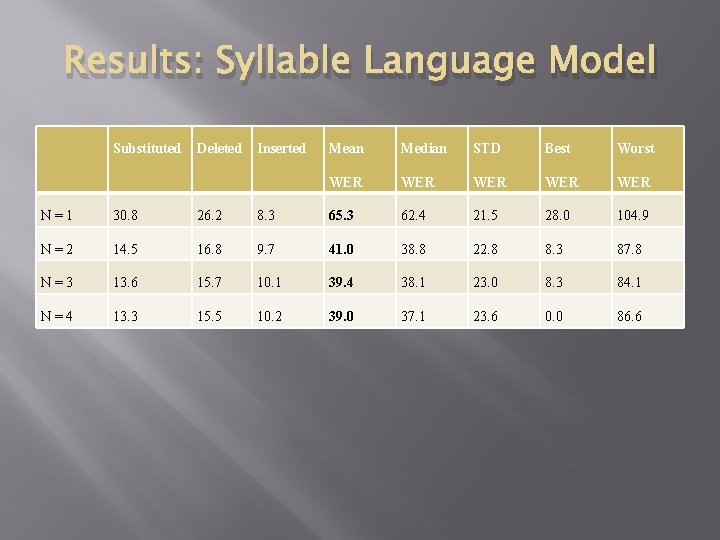

Results: Syllable Language Model Substituted Deleted Inserted Mean Median STD Best Worst WER WER WER N=1 30. 8 26. 2 8. 3 65. 3 62. 4 21. 5 28. 0 104. 9 N=2 14. 5 16. 8 9. 7 41. 0 38. 8 22. 8 8. 3 87. 8 N=3 13. 6 15. 7 10. 1 39. 4 38. 1 23. 0 8. 3 84. 1 N=4 13. 3 15. 5 10. 2 39. 0 37. 1 23. 6 0. 0 86. 6

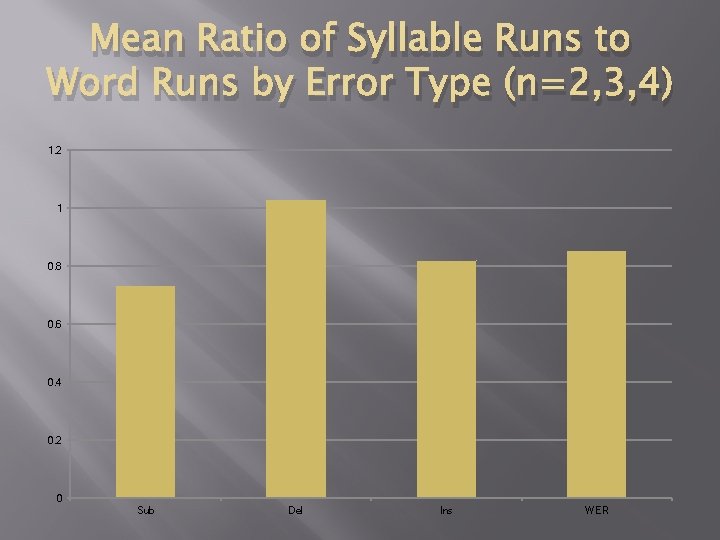

Mean Ratio of Syllable Runs to Word Runs by Error Type (n=2, 3, 4) 1. 2 1 0. 8 0. 6 0. 4 0. 2 0 Sub Del Ins WER

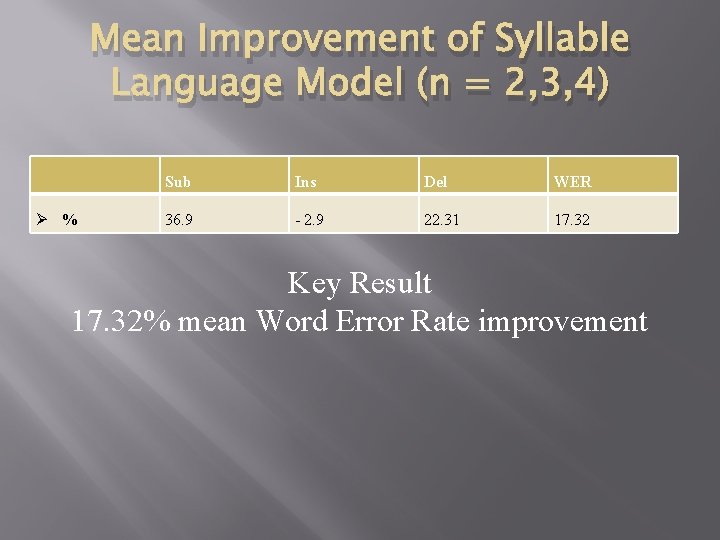

Mean Improvement of Syllable Language Model (n = 2, 3, 4) % Sub Ins Del WER 36. 9 - 2. 9 22. 31 17. 32 Key Result 17. 32% mean Word Error Rate improvement

Experiment 3: Stress Markings � � NIST syllabifier does not require (but can accept) stress markings Evidence that stress is involved in human syllabification: “segmentation for lexical access occurs at strong syllables” (Cutler & Norris 1988, 115) � Strong syllables are characterized by full vowels (eye, pill) � Weak syllables contain schwa or some reduced form of a vowel (second syllable in ion, scrounges) � Do stress markings result in a better/different NIST syllabification?

Input Compared Either is legal NIST syllabifier input for adult � [ax d ah l t] � ['0 ax d '1 ah l t] � Where 0/1 indicates nostress/stress

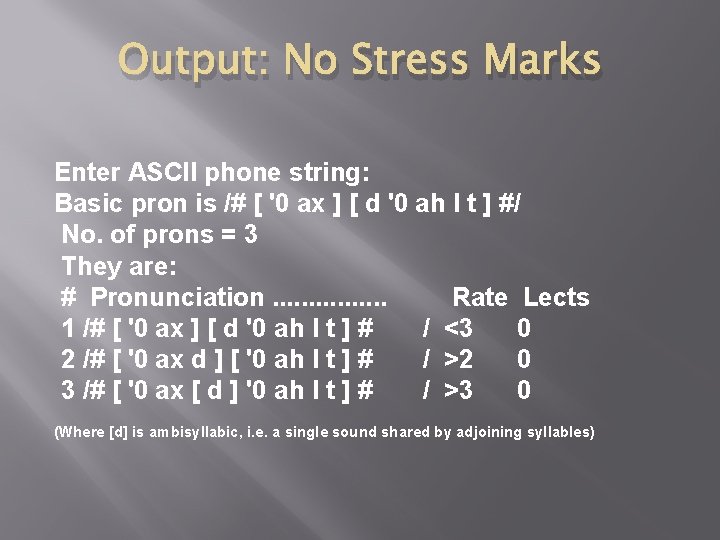

Output: No Stress Marks Enter ASCII phone string: Basic pron is /# [ '0 ax ] [ d '0 ah l t ] #/ No. of prons = 3 They are: # Pronunciation. . . . Rate Lects 1 /# [ '0 ax ] [ d '0 ah l t ] # / <3 0 2 /# [ '0 ax d ] [ '0 ah l t ] # / >2 0 3 /# [ '0 ax [ d ] '0 ah l t ] # / >3 0 (Where [d] is ambisyllabic, i. e. a single sound shared by adjoining syllables)

![Output: Stress Enter ASCII phone string: Basic pron is /# [ '0 ax ] Output: Stress Enter ASCII phone string: Basic pron is /# [ '0 ax ]](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7f150be8c26b3697784601571d84d367/image-34.jpg)

Output: Stress Enter ASCII phone string: Basic pron is /# [ '0 ax ] [ d '1 ah l t ] #/ No. of prons = 1 They are: # Pronunciation. . . . Rate Lects 1 /# [ '0 ax ] [ d '1 ah l t ] # / >0 0 Notice: This is the same as the basic pronunciation for the no stress input

Technique � � � Hand extract every mutisyllablic word in the training corpus Determine the canonical pronunciation using the Carnegie-Mellon pronunciation dictionary Syllabify the multisyllabic words using NIST Compare the syllabifications for stress unmarked/marked If different =>generate a second language and compare the results of the recognizer

Specifically � � � 44 words are multisyllabic in the corpus The pronouncer handled 41 of 44 Hand mark goin’, washtuh, washtuc (where the last is a place name in Washington State, and the middle is a disfluency that immediately precedes the last)

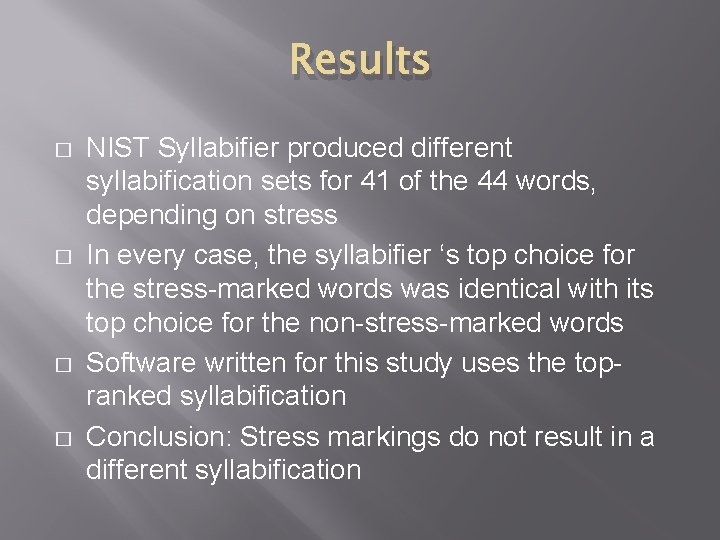

Results � � NIST Syllabifier produced different syllabification sets for 41 of the 44 words, depending on stress In every case, the syllabifier ‘s top choice for the stress-marked words was identical with its top choice for the non-stress-marked words Software written for this study uses the topranked syllabification Conclusion: Stress markings do not result in a different syllabification

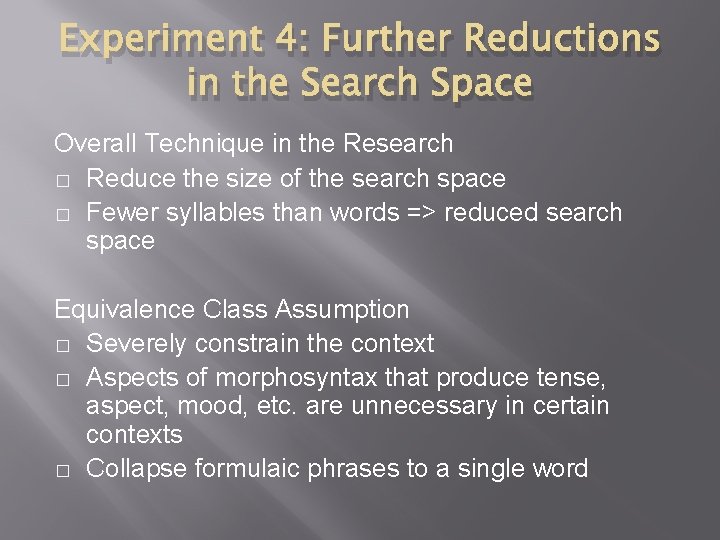

Experiment 4: Further Reductions in the Search Space Overall Technique in the Research � Reduce the size of the search space � Fewer syllables than words => reduced search space Equivalence Class Assumption � Severely constrain the context � Aspects of morphosyntax that produce tense, aspect, mood, etc. are unnecessary in certain contexts � Collapse formulaic phrases to a single word

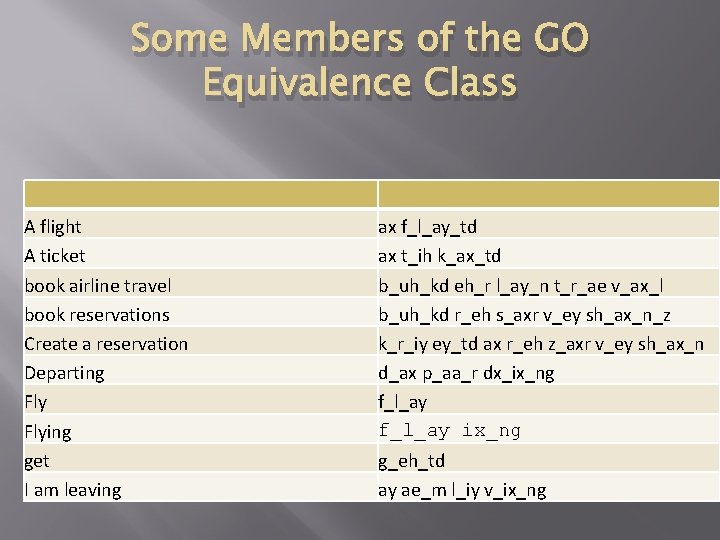

Some Members of the GO Equivalence Class A flight A ticket book airline travel book reservations Create a reservation Departing Flying get I am leaving ax f_l_ay_td ax t_ih k_ax_td b_uh_kd eh_r l_ay_n t_r_ae v_ax_l b_uh_kd r_eh s_axr v_ey sh_ax_n_z k_r_iy ey_td ax r_eh z_axr v_ey sh_ax_n d_ax p_aa_r dx_ix_ng f_l_ay ix_ng g_eh_td ay ae_m l_iy v_ix_ng

Question � Will the reduction of word strings to equivalence classes provide an WER sufficient to justify building a probabilistic concept language model

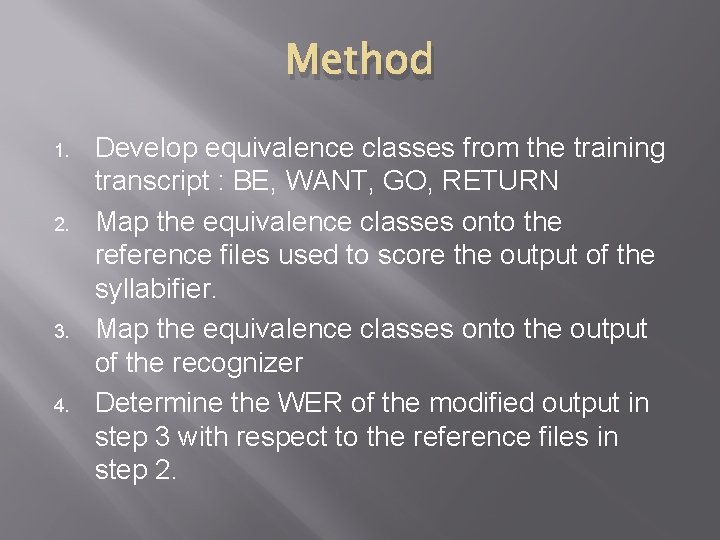

Method 1. 2. 3. 4. Develop equivalence classes from the training transcript : BE, WANT, GO, RETURN Map the equivalence classes onto the reference files used to score the output of the syllabifier. Map the equivalence classes onto the output of the recognizer Determine the WER of the modified output in step 3 with respect to the reference files in step 2.

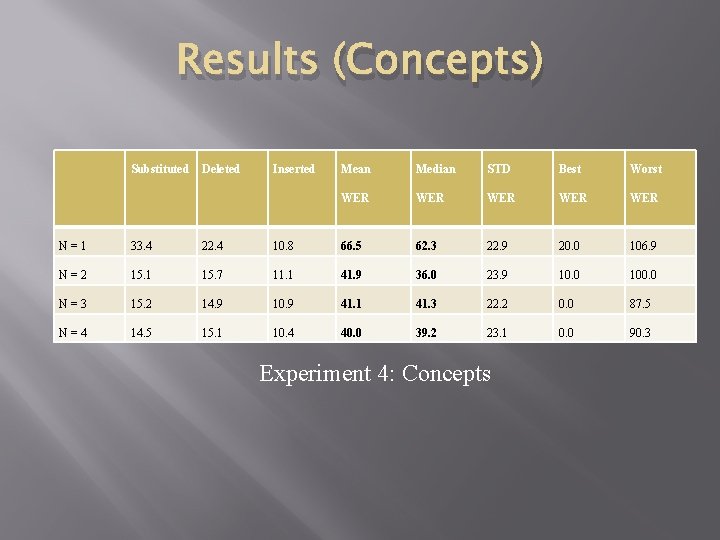

Results (Concepts) Substituted Deleted Inserted Mean Median STD Best Worst WER WER WER N=1 33. 4 22. 4 10. 8 66. 5 62. 3 22. 9 20. 0 106. 9 N=2 15. 1 15. 7 11. 1 41. 9 36. 0 23. 9 10. 0 100. 0 N=3 15. 2 14. 9 10. 9 41. 1 41. 3 22. 2 0. 0 87. 5 N=4 14. 5 15. 1 10. 4 40. 0 39. 2 23. 1 0. 0 90. 3 Experiment 4: Concepts

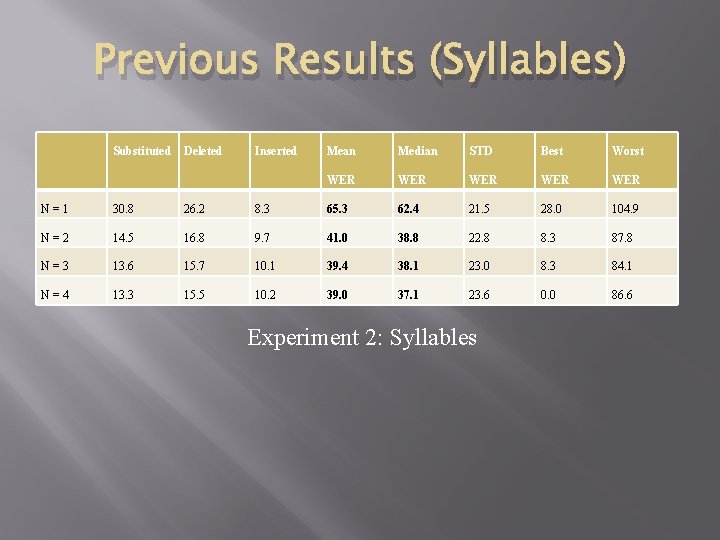

Previous Results (Syllables) Substituted Deleted Inserted Mean Median STD Best Worst WER WER WER N=1 30. 8 26. 2 8. 3 65. 3 62. 4 21. 5 28. 0 104. 9 N=2 14. 5 16. 8 9. 7 41. 0 38. 8 22. 8 8. 3 87. 8 N=3 13. 6 15. 7 10. 1 39. 4 38. 1 23. 0 8. 3 84. 1 N=4 13. 3 15. 5 10. 2 39. 0 37. 1 23. 6 0. 0 86. 6 Experiment 2: Syllables

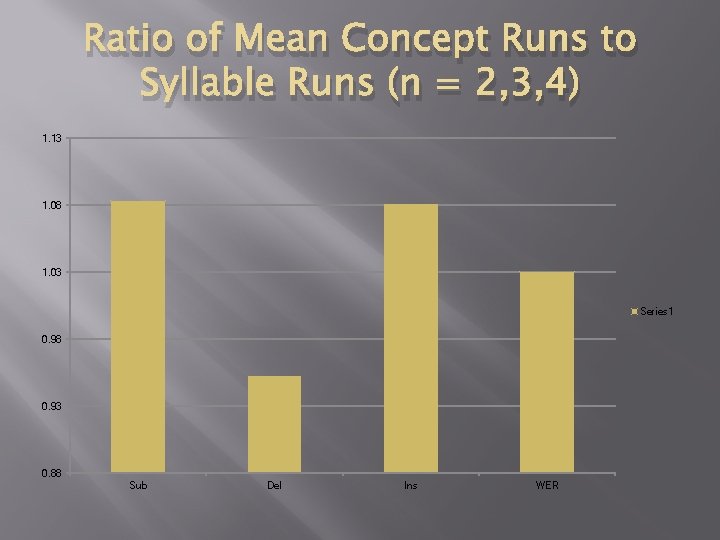

Ratio of Mean Concept Runs to Syllable Runs (n = 2, 3, 4) 1. 13 1. 08 1. 03 Series 1 0. 98 0. 93 0. 88 Sub Del Ins WER

Concept WER > Syllable WER by ~ 3% Why?

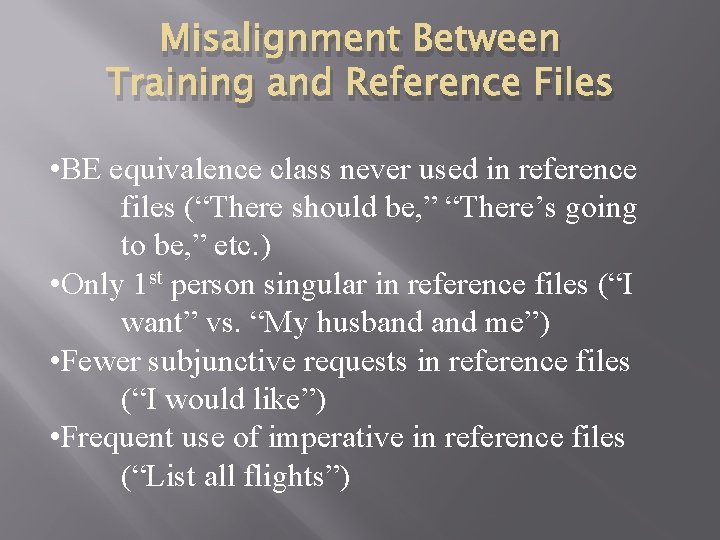

Misalignment Between Training and Reference Files • BE equivalence class never used in reference files (“There should be, ” “There’s going to be, ” etc. ) • Only 1 st person singular in reference files (“I want” vs. “My husband me”) • Fewer subjunctive requests in reference files (“I would like”) • Frequent use of imperative in reference files (“List all flights”)

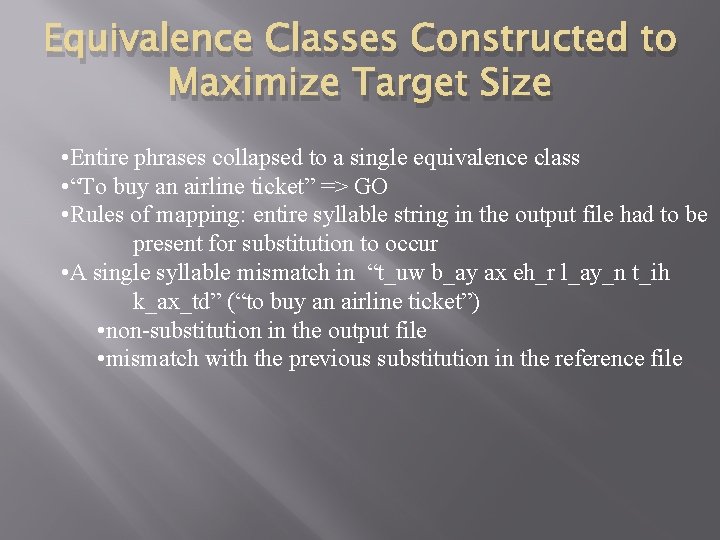

Equivalence Classes Constructed to Maximize Target Size • Entire phrases collapsed to a single equivalence class • “To buy an airline ticket” => GO • Rules of mapping: entire syllable string in the output file had to be present for substitution to occur • A single syllable mismatch in “t_uw b_ay ax eh_r l_ay_n t_ih k_ax_td” (“to buy an airline ticket”) • non-substitution in the output file • mismatch with the previous substitution in the reference file

Conclusion Given: 1. Mismatch between training and reference files 2. Rigid equivalence class mapping rules 3% increase in WER is very small and justifies further research

Summary � � 1. Perplexity testing suggests that a segmented language model will perform better than a word language model 2. Syllable language model results in a 17% mean reduction in WER 3. Use of stress markings in input to syllabifier does not result in an improved syllabification 4. The very slight increase in mean WER for a concept language model => probabilistic concept language could improve WER

Further Research 1. 2. 3. Develop of a probabilistic concept language model Test the given system over a large production corpus Develop necessary software to pass the output of the concept language model on to an expert system.

The Last Word “But it must be recognized that the notion ‘probability of a sentence’ is an entirely useless one under any known interpretation of the term. ” Cited in Jurafsky and Martin (2009) from a 1969 essay on Quine.

References Cutler, A. , Dahan, D. , Donselaar, W. (2007). Prosody in the Comprehension of Spoken Language: A Literature Review. Language and Speech, 40(2), 141 -201. Hemphill, C. , Godfrey, J. , Doddington, G. (2009). The ATIS Spoken Language Systems Pilot Corpus. Retrieved 6/17/09 from: http: //www. ldc. upenn. edu/Catalog/readme_files/atis/sspcrd/corpus. html Jurafsky, D. , Martin, J. (2000) Speech and Language Processing: An Introduction to Natural Language Processing, Computational Linguistics, and Speech Recognition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Jurafsky, D. , Martin, J. (2009) Speech and Language Processing: An. Introduction to Natural Language Processing, Computational Linguistics, and Speech Recognition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Next. It. (2008). Retrieved 4/5/08 from: http: /www. nextit. com.

- Slides: 52