SECTION 13 8 STOKES THEOREM STOKES VS GREENS

- Slides: 47

SECTION 13. 8 STOKES’ THEOREM

STOKES’ VS. GREEN’S THEOREM v. Stokes’ Theorem can be regarded as a higherdimensional version of Green’s Theorem. n n Green’s Theorem relates a double integral over a plane region D to a line integral around its plane boundary curve. Stokes’ Theorem relates a surface integral over a surface S to a line integral around the boundary curve of S (a space curve). 13. 8 P 2

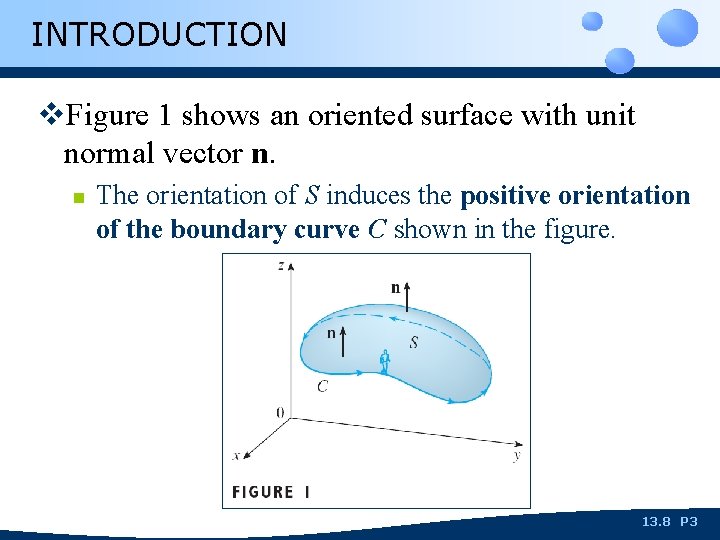

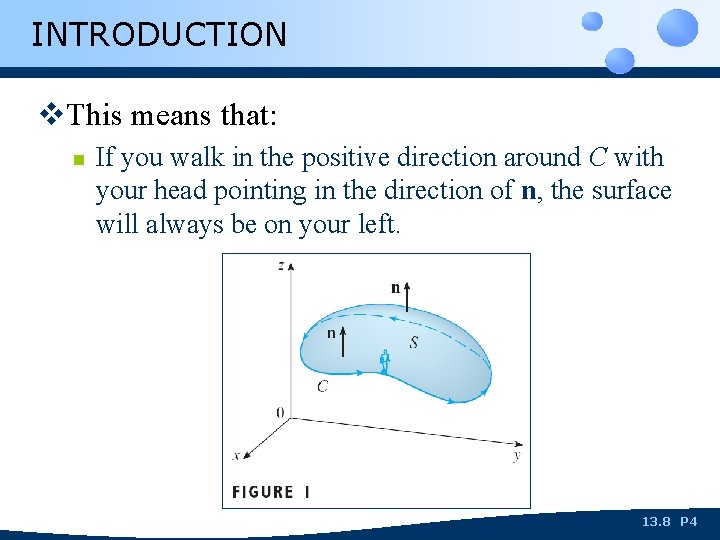

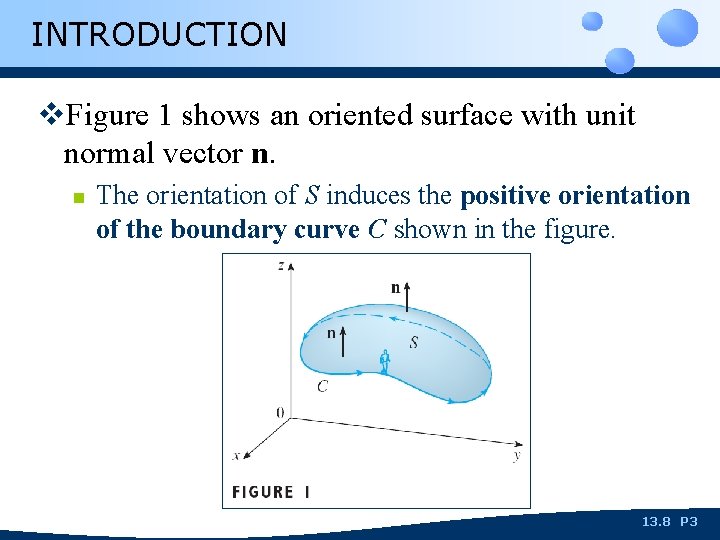

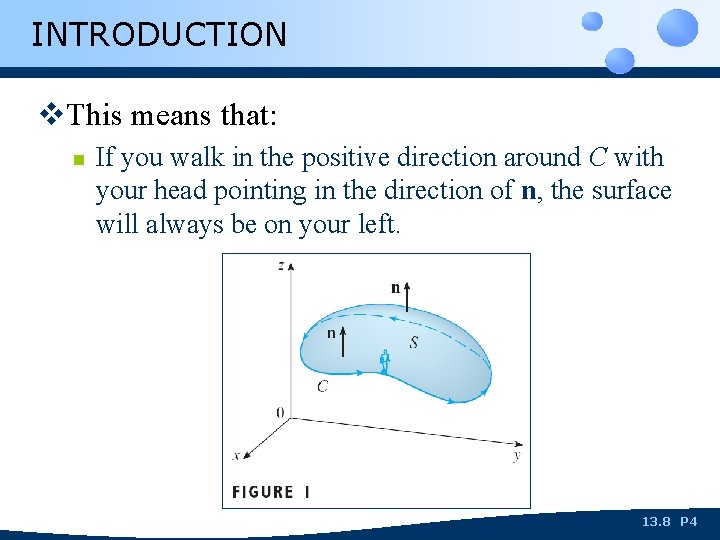

INTRODUCTION v. Figure 1 shows an oriented surface with unit normal vector n. n The orientation of S induces the positive orientation of the boundary curve C shown in the figure. 13. 8 P 3

INTRODUCTION v. This means that: n If you walk in the positive direction around C with your head pointing in the direction of n, the surface will always be on your left. 13. 8 P 4

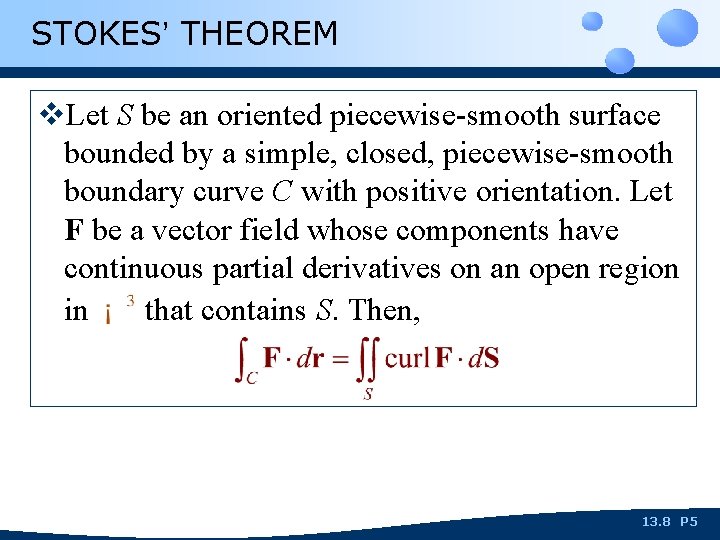

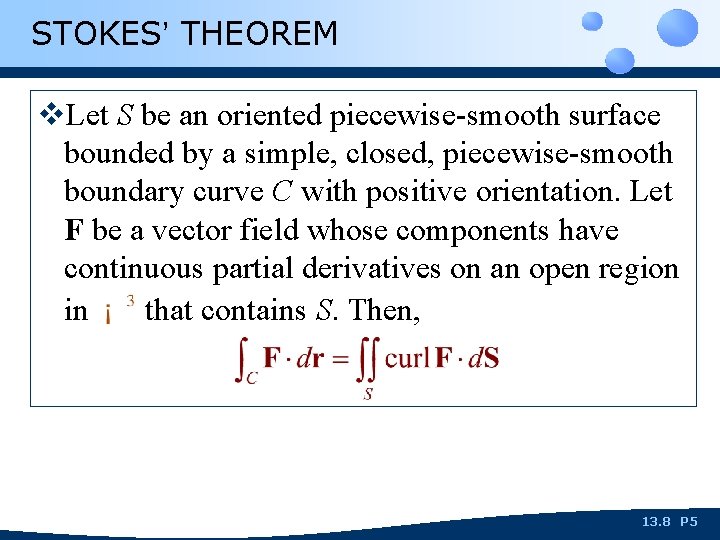

STOKES’ THEOREM v. Let S be an oriented piecewise-smooth surface bounded by a simple, closed, piecewise-smooth boundary curve C with positive orientation. Let F be a vector field whose components have continuous partial derivatives on an open region in that contains S. Then, 13. 8 P 5

STOKES’ THEOREM v. The theorem is named after the Irish mathematical physicist Sir George Stokes (1819 – 1903). n n What we call Stokes’ Theorem was actually discovered by the Scottish physicist Sir William Thomson (1824– 1907, known as Lord Kelvin). Stokes learned of it in a letter from Thomson in 1850. 13. 8 P 6

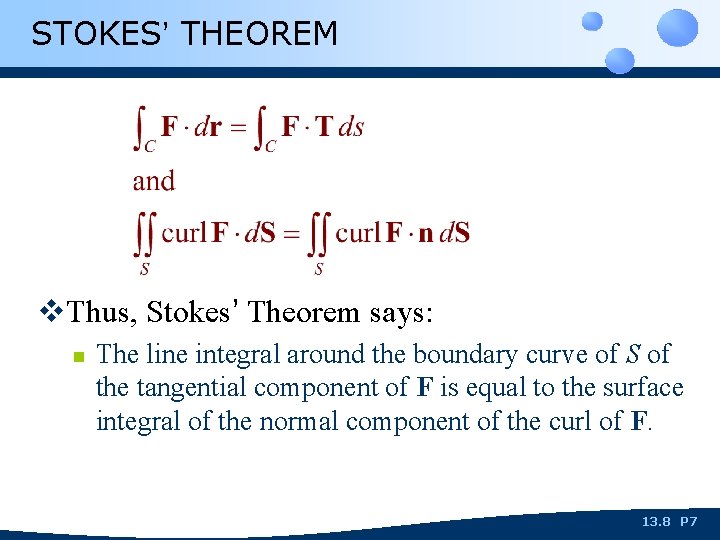

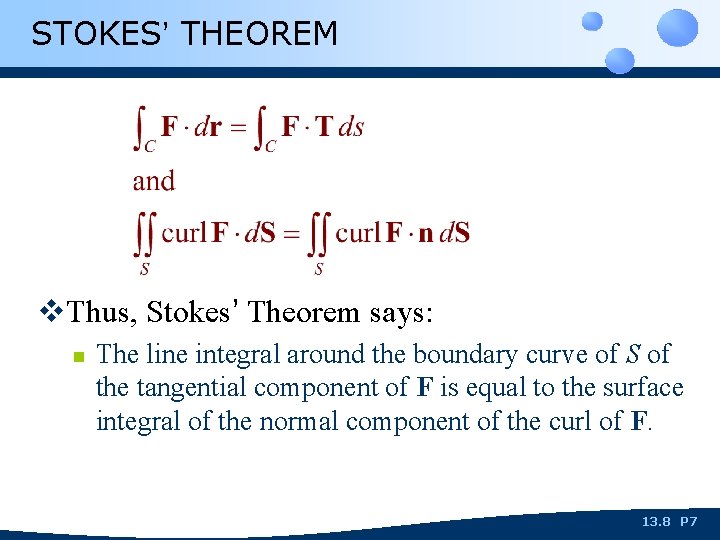

STOKES’ THEOREM v. Thus, Stokes’ Theorem says: n The line integral around the boundary curve of S of the tangential component of F is equal to the surface integral of the normal component of the curl of F. 13. 8 P 7

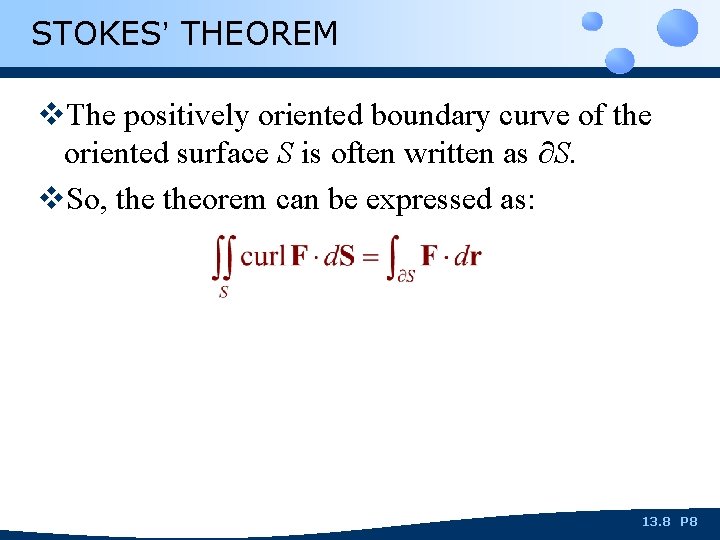

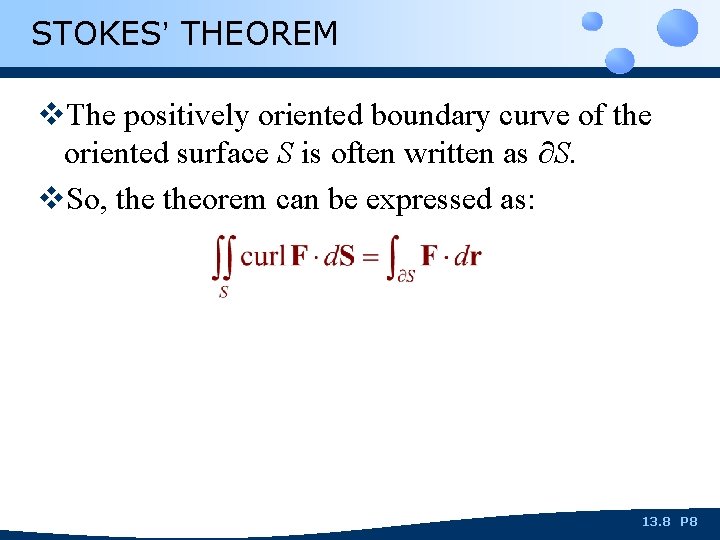

STOKES’ THEOREM v. The positively oriented boundary curve of the oriented surface S is often written as ∂S. v. So, theorem can be expressed as: 13. 8 P 8

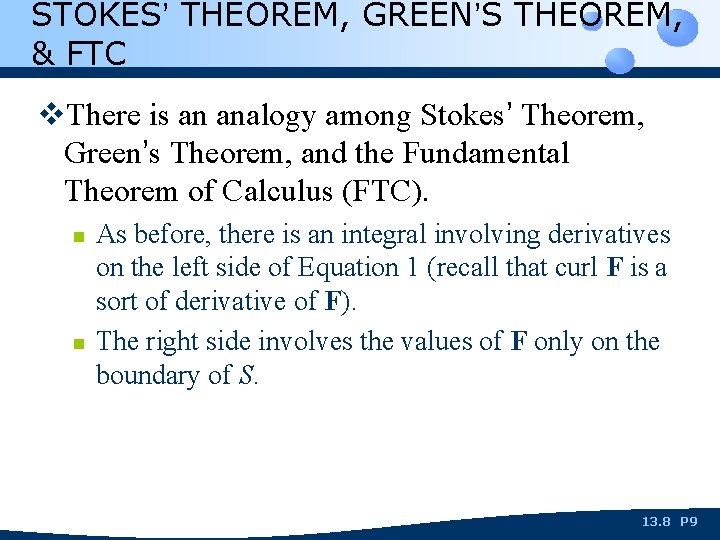

STOKES’ THEOREM, GREEN’S THEOREM, & FTC v. There is an analogy among Stokes’ Theorem, Green’s Theorem, and the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus (FTC). n n As before, there is an integral involving derivatives on the left side of Equation 1 (recall that curl F is a sort of derivative of F). The right side involves the values of F only on the boundary of S. 13. 8 P 9

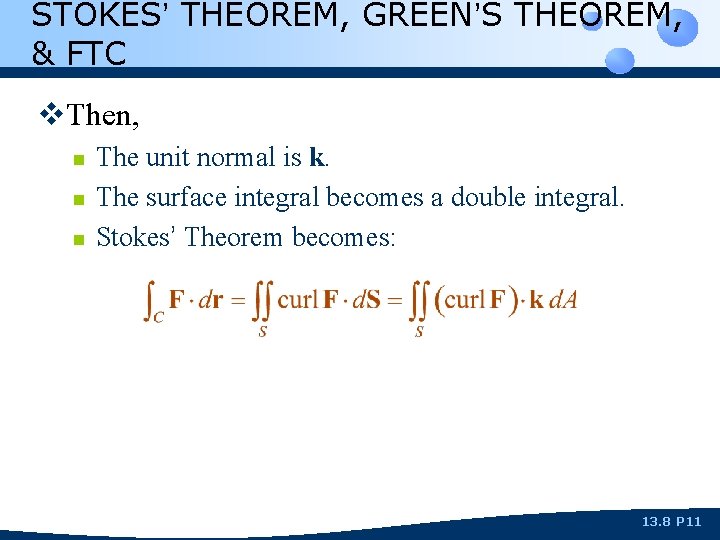

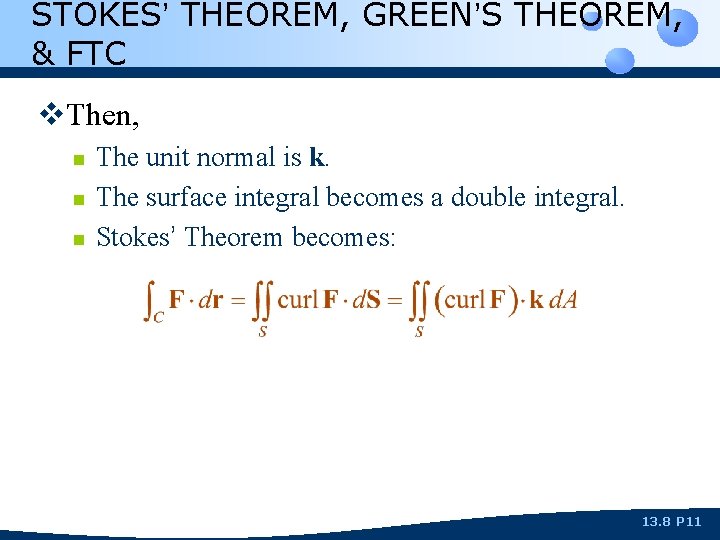

STOKES’ THEOREM, GREEN’S THEOREM, & FTC v. In fact, consider the special case where the surface S: n n Is flat. Lies in the xy-plane with upward orientation. 13. 8 P 10

STOKES’ THEOREM, GREEN’S THEOREM, & FTC v. Then, n n n The unit normal is k. The surface integral becomes a double integral. Stokes’ Theorem becomes: 13. 8 P 11

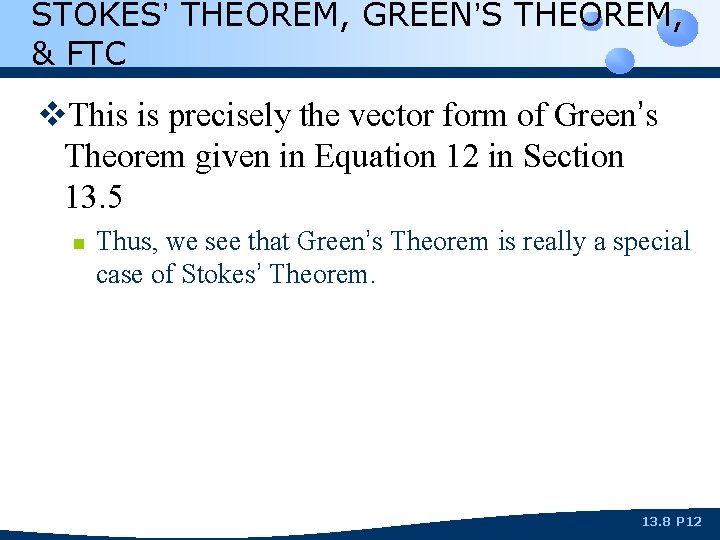

STOKES’ THEOREM, GREEN’S THEOREM, & FTC v. This is precisely the vector form of Green’s Theorem given in Equation 12 in Section 13. 5 n Thus, we see that Green’s Theorem is really a special case of Stokes’ Theorem. 13. 8 P 12

STOKES’ THEOREM v. Stokes’ Theorem is too difficult for us to prove in its full generality. v. Still, we can give a proof when: n n S is a graph. F, S, and C are well behaved. 13. 8 P 13

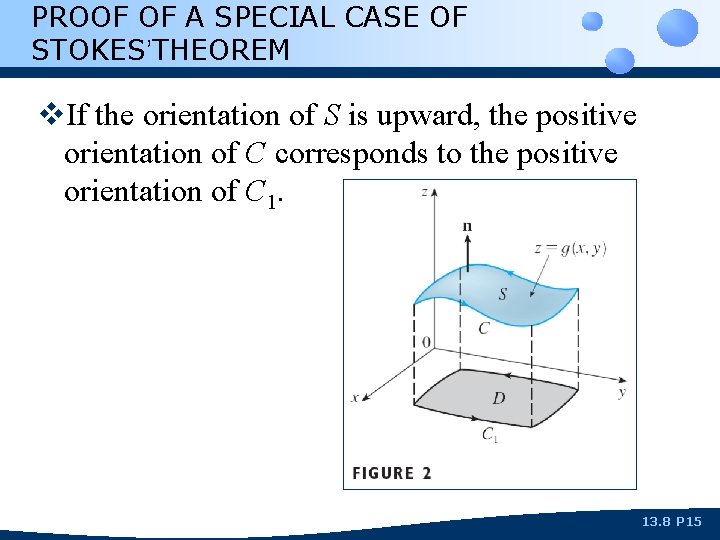

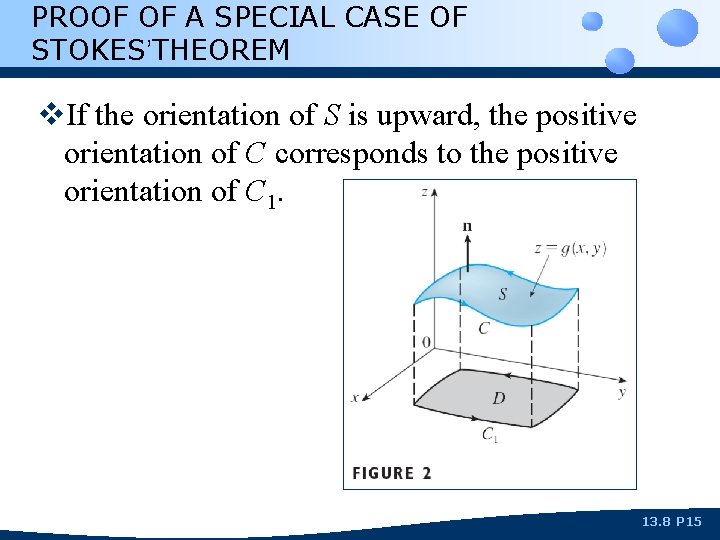

PROOF OF A SPECIAL CASE OF STOKES’THEOREM v. We assume that the equation of S is: z = g(x, y), (x, y) D where: n n g has continuous second-order partial derivatives. D is a simple plane region whose boundary curve C 1 corresponds to C. 13. 8 P 14

PROOF OF A SPECIAL CASE OF STOKES’THEOREM v. If the orientation of S is upward, the positive orientation of C corresponds to the positive orientation of C 1. 13. 8 P 15

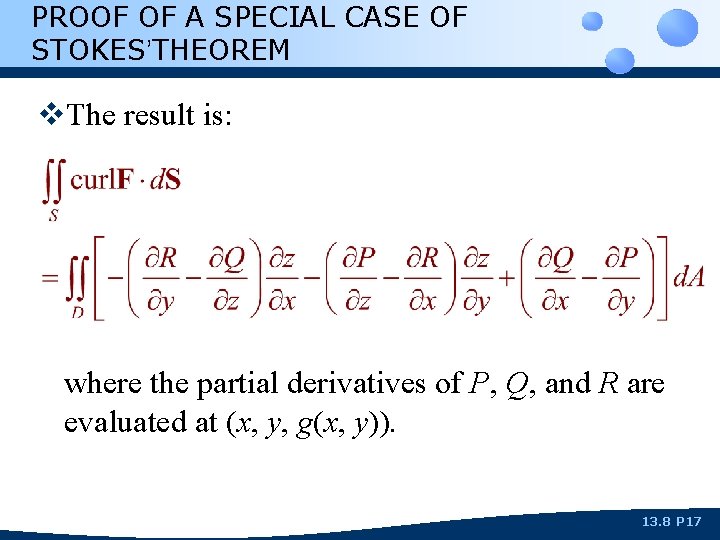

PROOF OF A SPECIAL CASE OF STOKES’THEOREM v. We are also given that: F=Pi+Qj+Rk where the partial derivatives of P, Q, and R are continuous. v. S is a graph of a function. v. Thus, we can apply Formula 10 in Section 13. 7 with F replaced by curl F. 13. 8 P 16

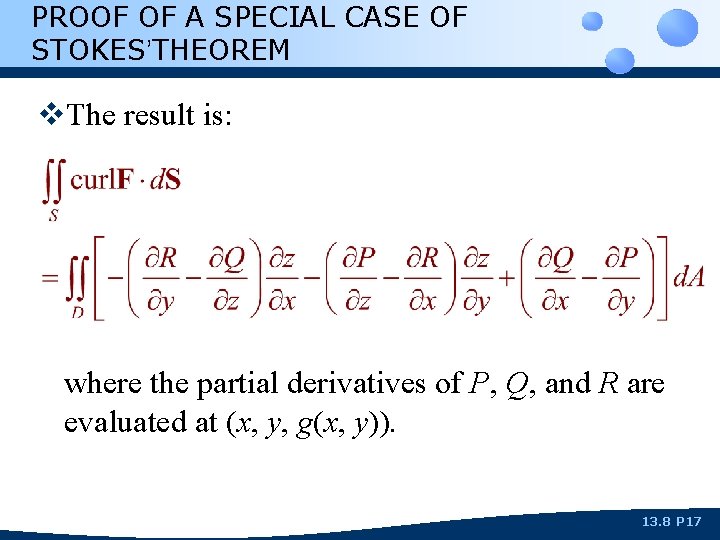

PROOF OF A SPECIAL CASE OF STOKES’THEOREM v. The result is: where the partial derivatives of P, Q, and R are evaluated at (x, y, g(x, y)). 13. 8 P 17

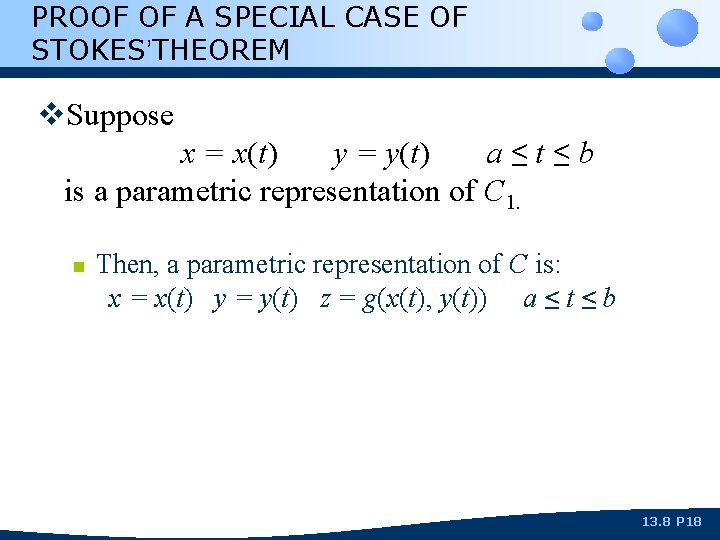

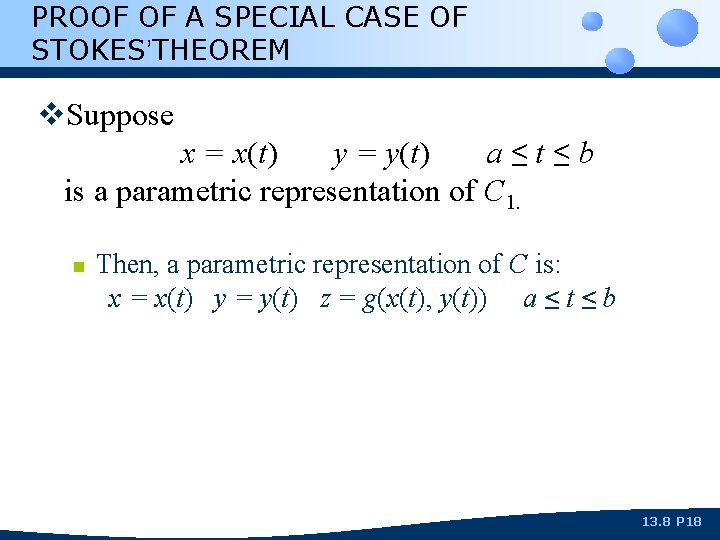

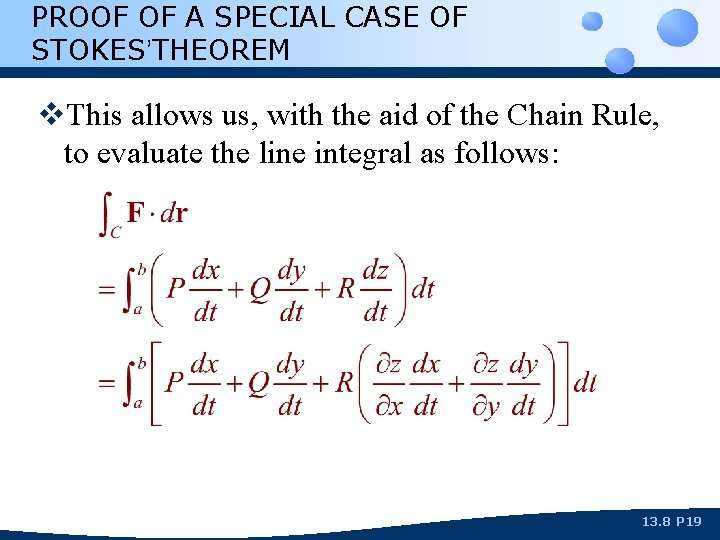

PROOF OF A SPECIAL CASE OF STOKES’THEOREM v. Suppose x = x(t) y = y(t) a≤t≤b is a parametric representation of C 1. n Then, a parametric representation of C is: x = x(t) y = y(t) z = g(x(t), y(t)) a ≤ t ≤ b 13. 8 P 18

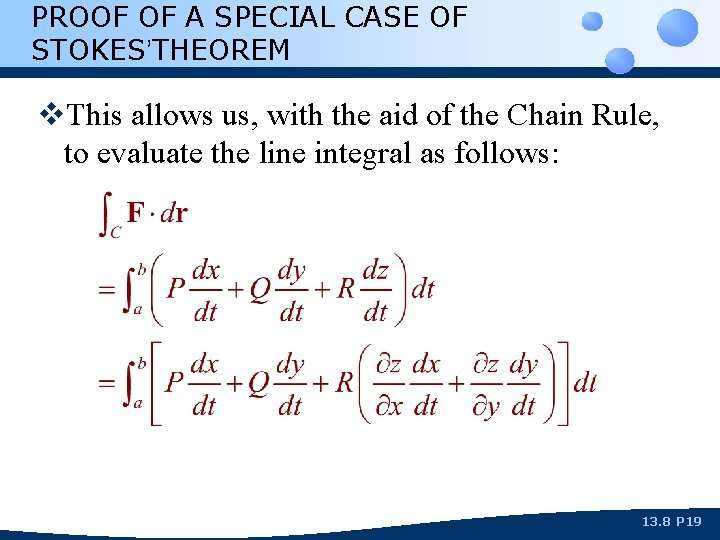

PROOF OF A SPECIAL CASE OF STOKES’THEOREM v. This allows us, with the aid of the Chain Rule, to evaluate the line integral as follows: 13. 8 P 19

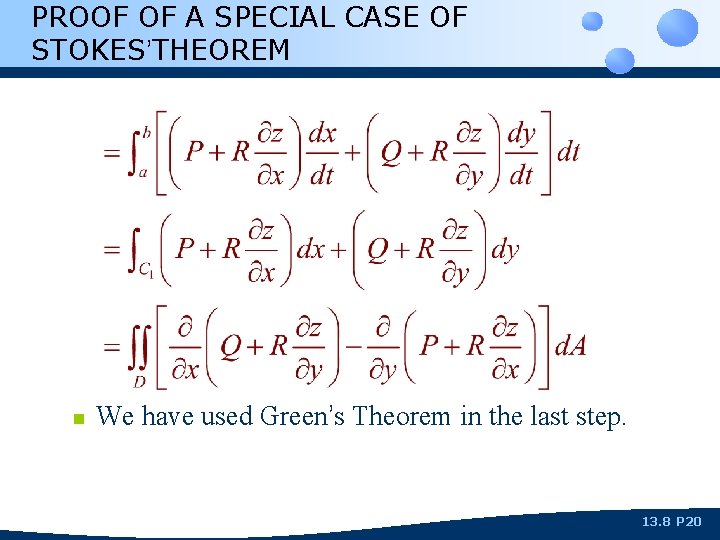

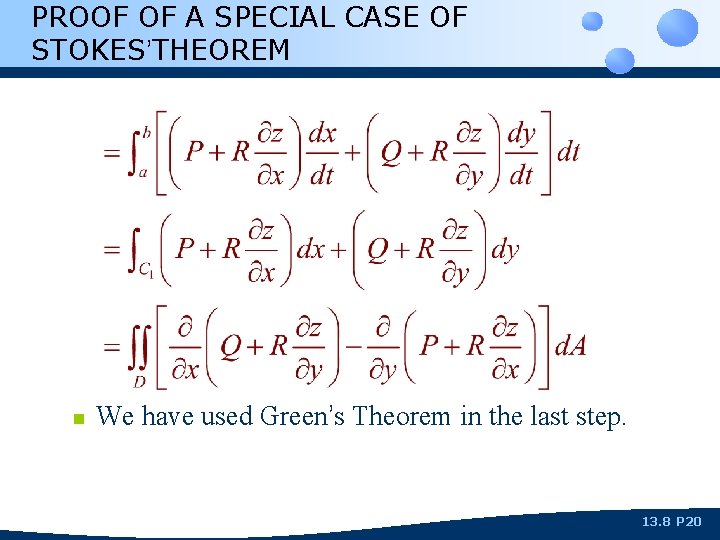

PROOF OF A SPECIAL CASE OF STOKES’THEOREM n We have used Green’s Theorem in the last step. 13. 8 P 20

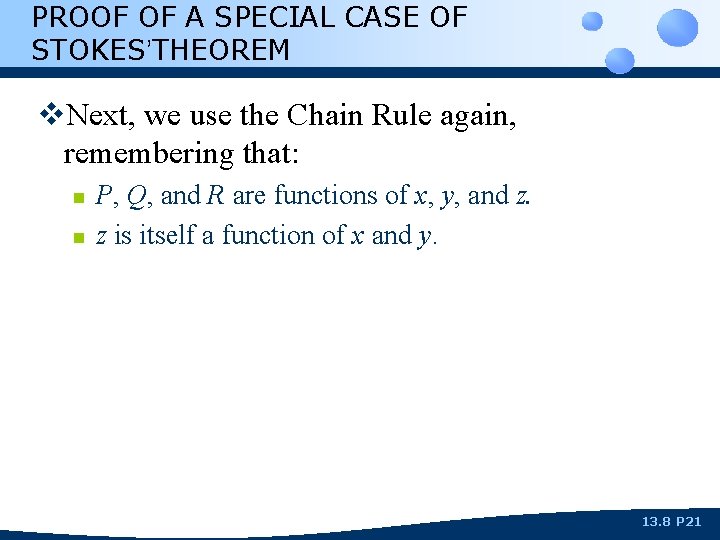

PROOF OF A SPECIAL CASE OF STOKES’THEOREM v. Next, we use the Chain Rule again, remembering that: n n P, Q, and R are functions of x, y, and z. z is itself a function of x and y. 13. 8 P 21

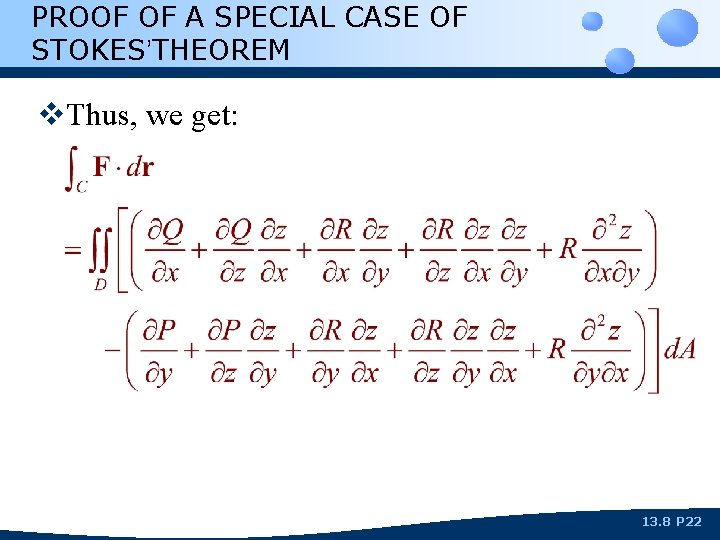

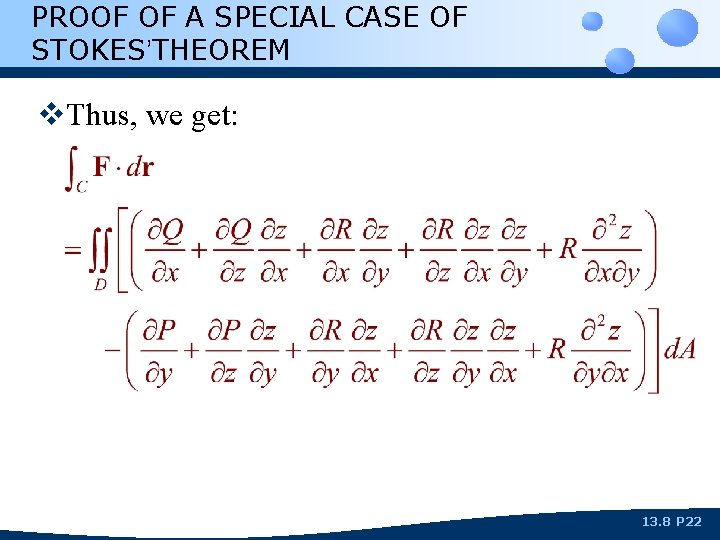

PROOF OF A SPECIAL CASE OF STOKES’THEOREM v. Thus, we get: 13. 8 P 22

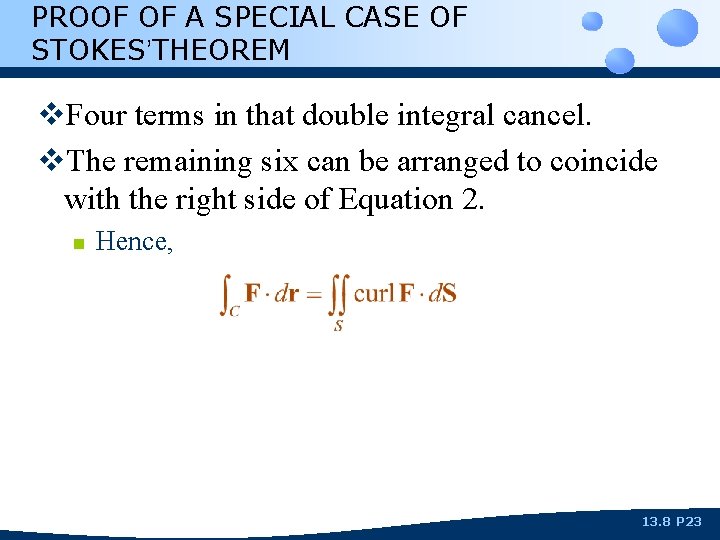

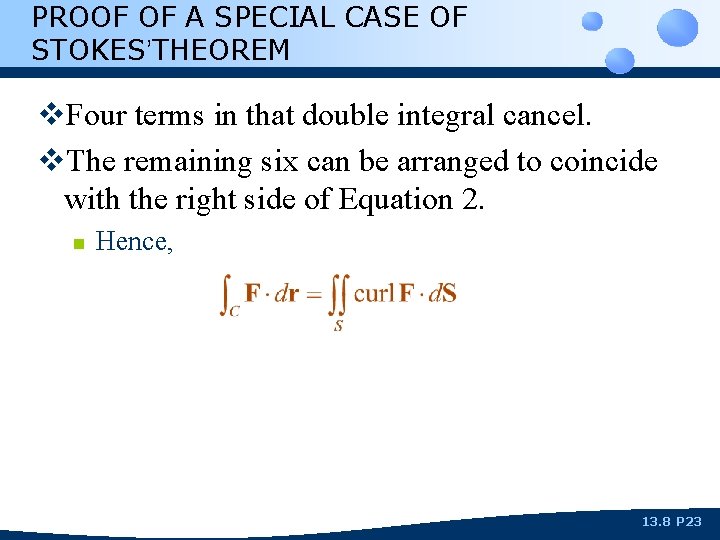

PROOF OF A SPECIAL CASE OF STOKES’THEOREM v. Four terms in that double integral cancel. v. The remaining six can be arranged to coincide with the right side of Equation 2. n Hence, 13. 8 P 23

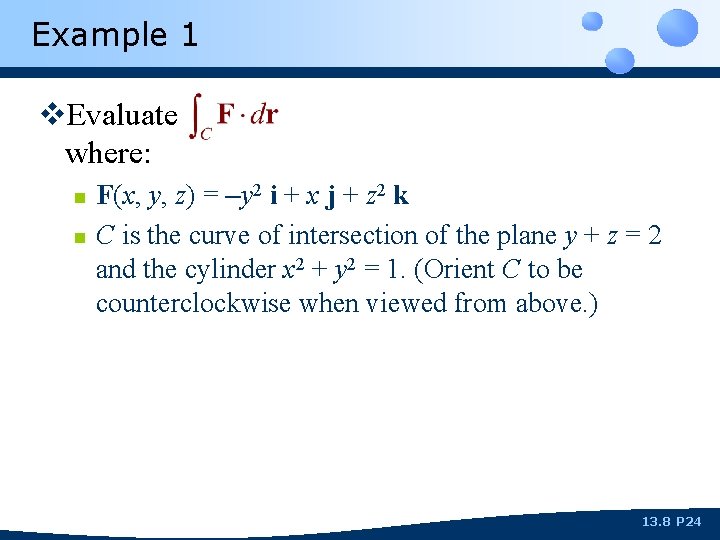

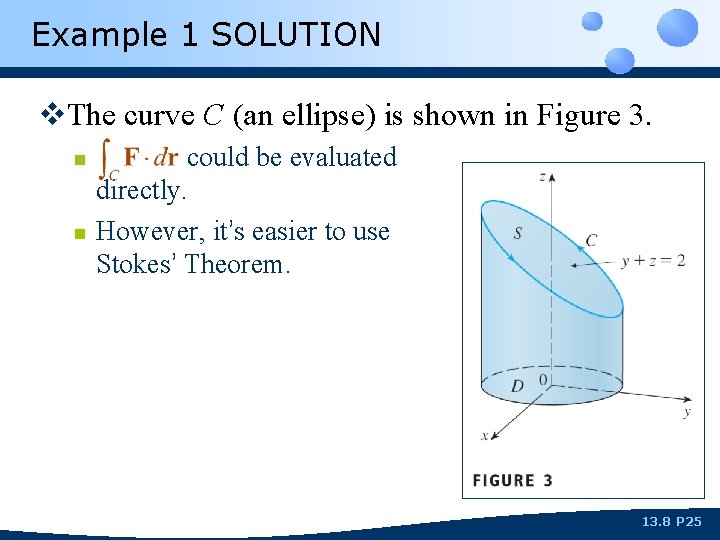

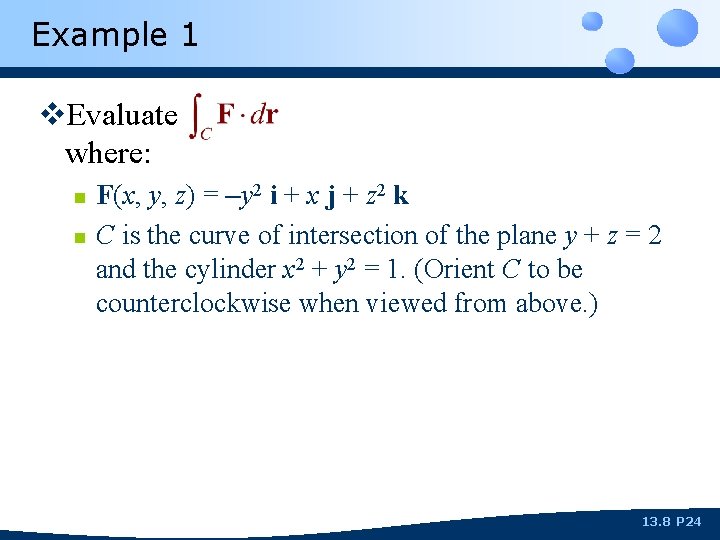

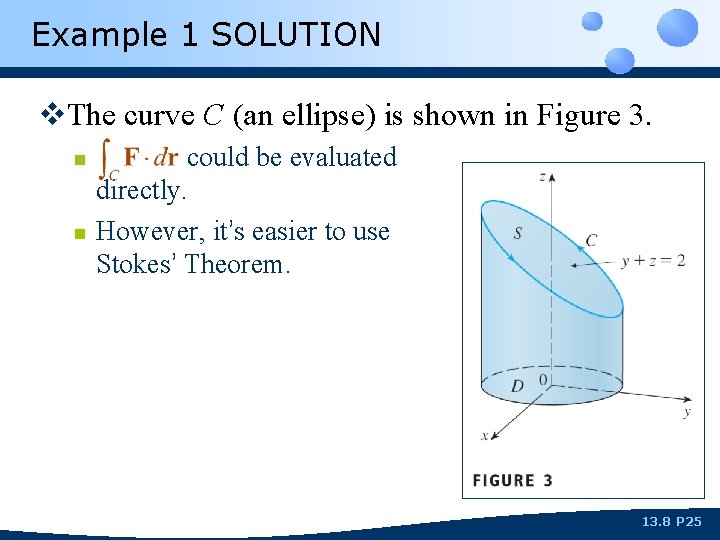

Example 1 v. Evaluate where: n n F(x, y, z) = –y 2 i + x j + z 2 k C is the curve of intersection of the plane y + z = 2 and the cylinder x 2 + y 2 = 1. (Orient C to be counterclockwise when viewed from above. ) 13. 8 P 24

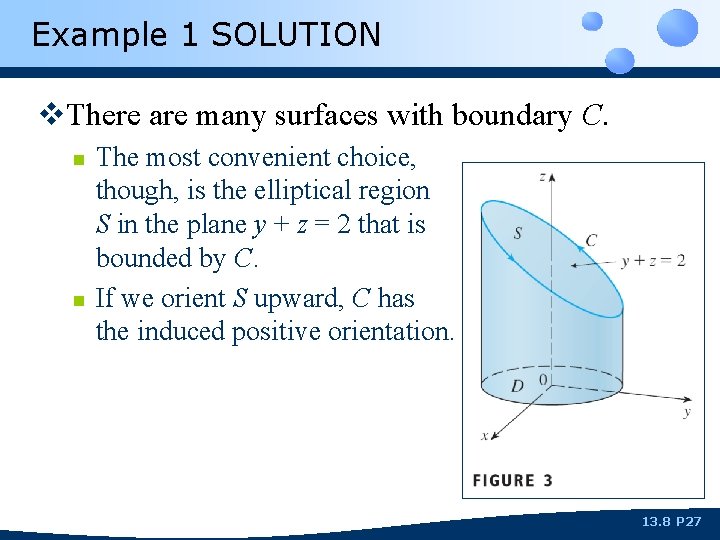

Example 1 SOLUTION v. The curve C (an ellipse) is shown in Figure 3. n n could be evaluated directly. However, it’s easier to use Stokes’ Theorem. 13. 8 P 25

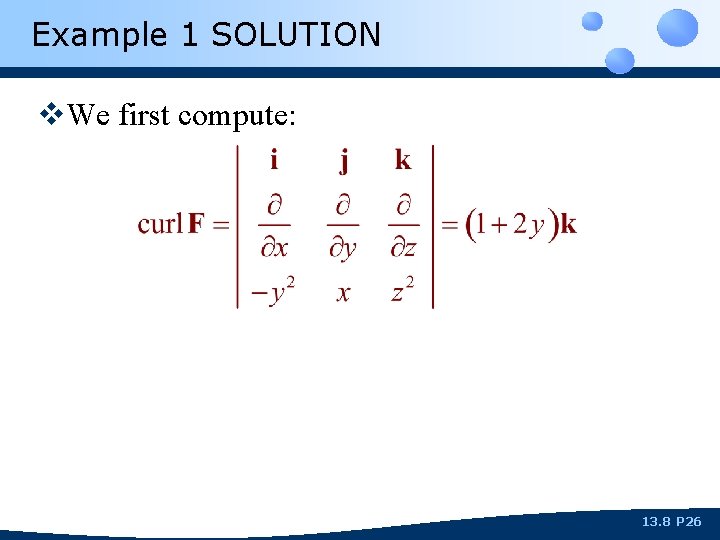

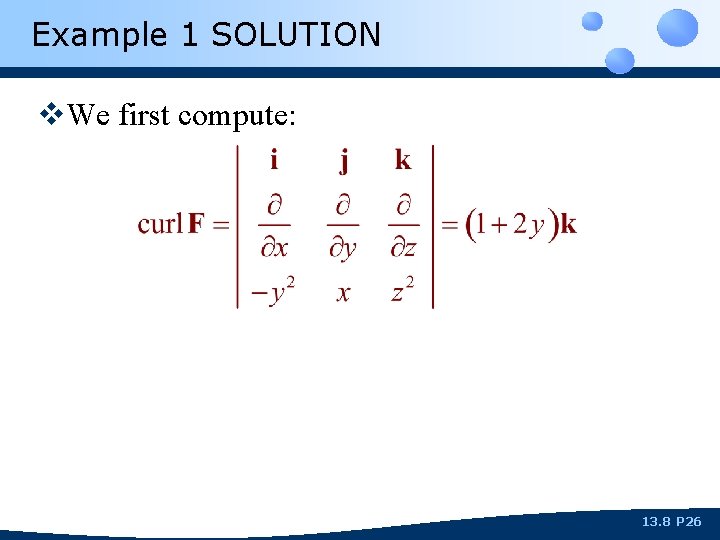

Example 1 SOLUTION v. We first compute: 13. 8 P 26

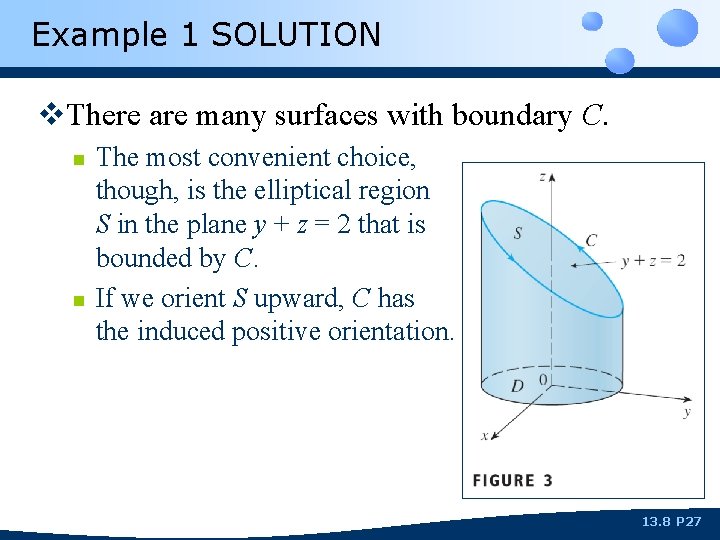

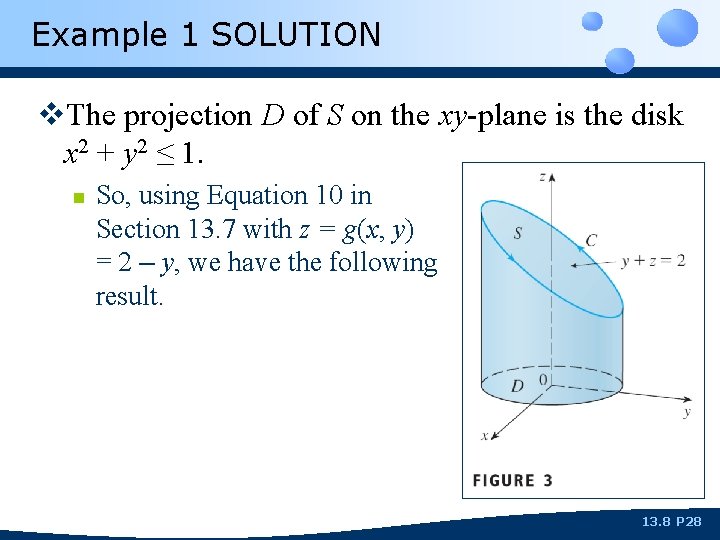

Example 1 SOLUTION v. There are many surfaces with boundary C. n n The most convenient choice, though, is the elliptical region S in the plane y + z = 2 that is bounded by C. If we orient S upward, C has the induced positive orientation. 13. 8 P 27

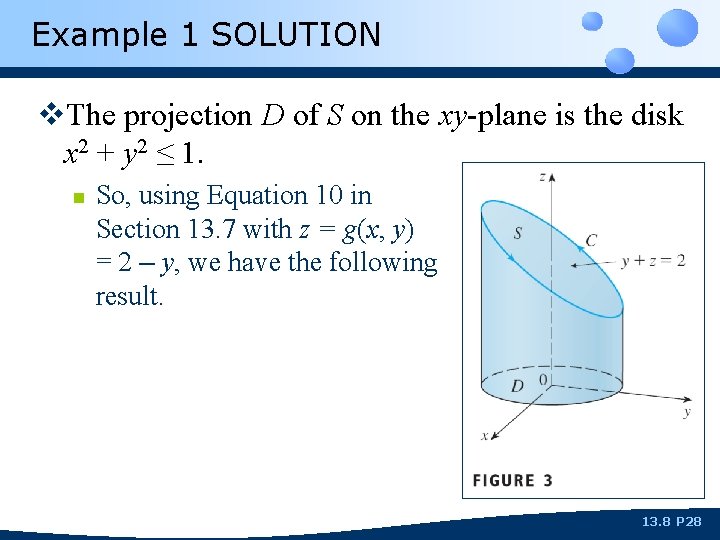

Example 1 SOLUTION v. The projection D of S on the xy-plane is the disk x 2 + y 2 ≤ 1. n So, using Equation 10 in Section 13. 7 with z = g(x, y) = 2 – y, we have the following result. 13. 8 P 28

Example 1 SOLUTION 13. 8 P 29

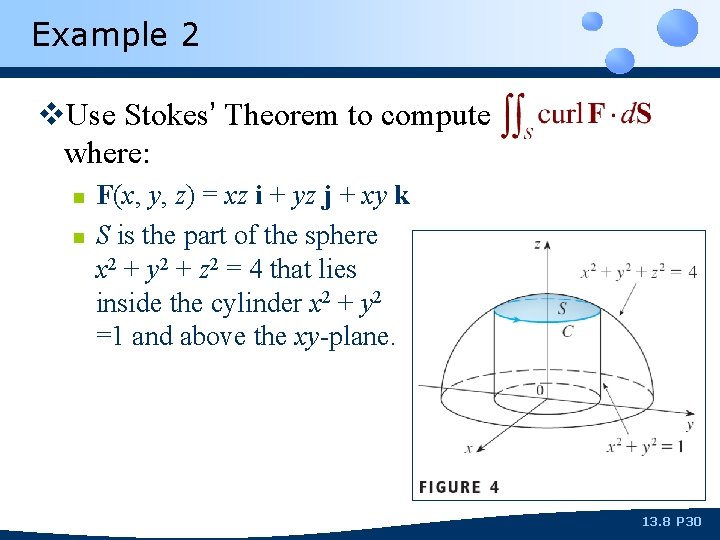

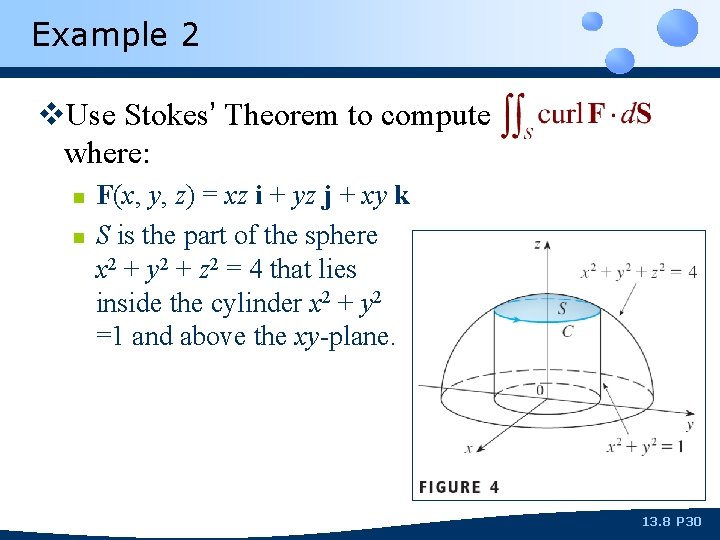

Example 2 v. Use Stokes’ Theorem to compute where: n n F(x, y, z) = xz i + yz j + xy k S is the part of the sphere x 2 + y 2 + z 2 = 4 that lies inside the cylinder x 2 + y 2 =1 and above the xy-plane. 13. 8 P 30

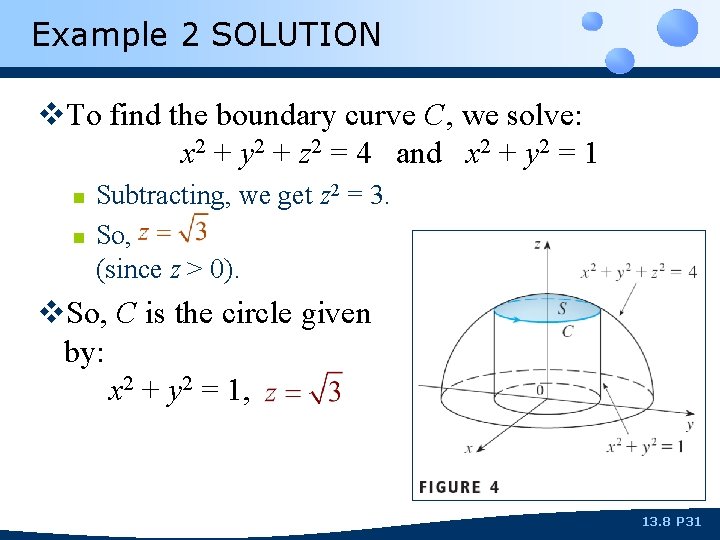

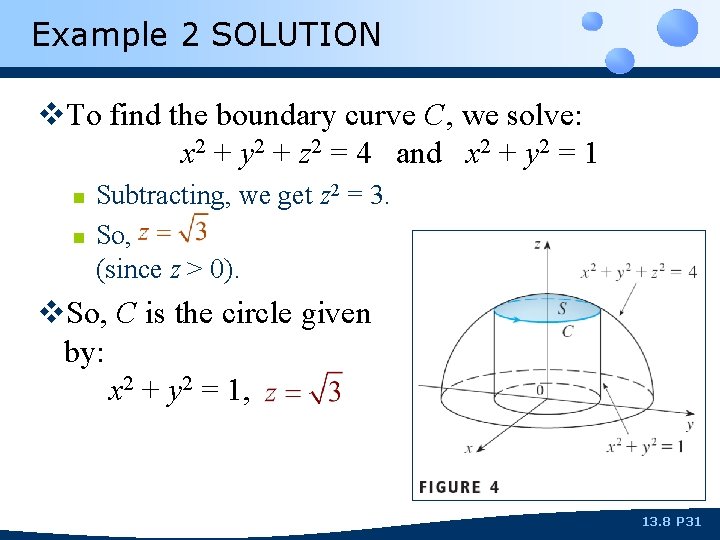

Example 2 SOLUTION v. To find the boundary curve C, we solve: x 2 + y 2 + z 2 = 4 and x 2 + y 2 = 1 n n Subtracting, we get z 2 = 3. So, (since z > 0). v. So, C is the circle given by: x 2 + y 2 = 1, 13. 8 P 31

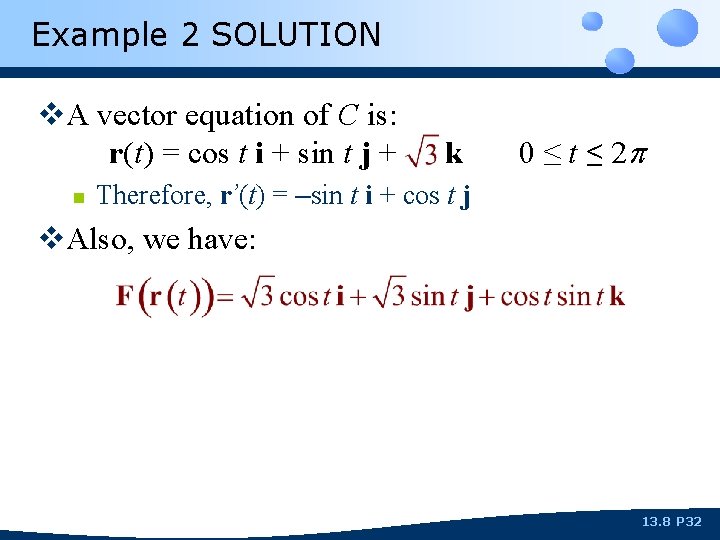

Example 2 SOLUTION v. A vector equation of C is: r(t) = cos t i + sin t j + n k 0 ≤ t ≤ 2 p Therefore, r’(t) = –sin t i + cos t j v. Also, we have: 13. 8 P 32

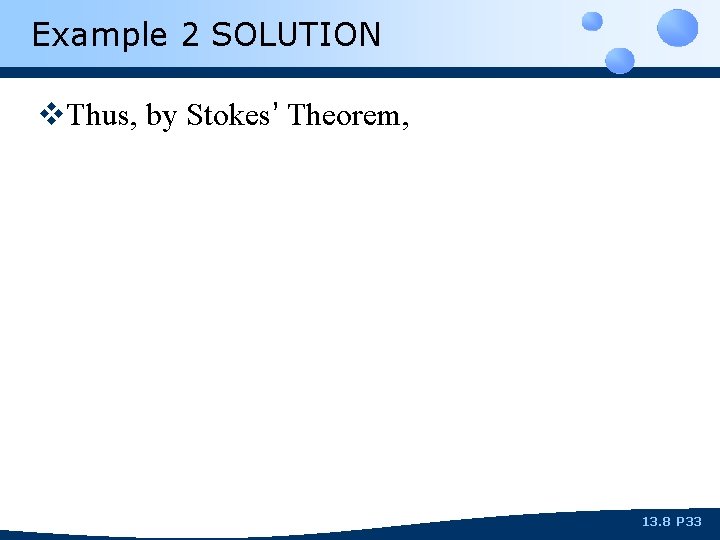

Example 2 SOLUTION v. Thus, by Stokes’ Theorem, 13. 8 P 33

STOKES’ THEOREM v. Note that, in Example 2, we computed a surface integral simply by knowing the values of F on the boundary curve C. v. This means that: n If we have another oriented surface with the same boundary curve C, we get exactly the same value for the surface integral! 13. 8 P 34

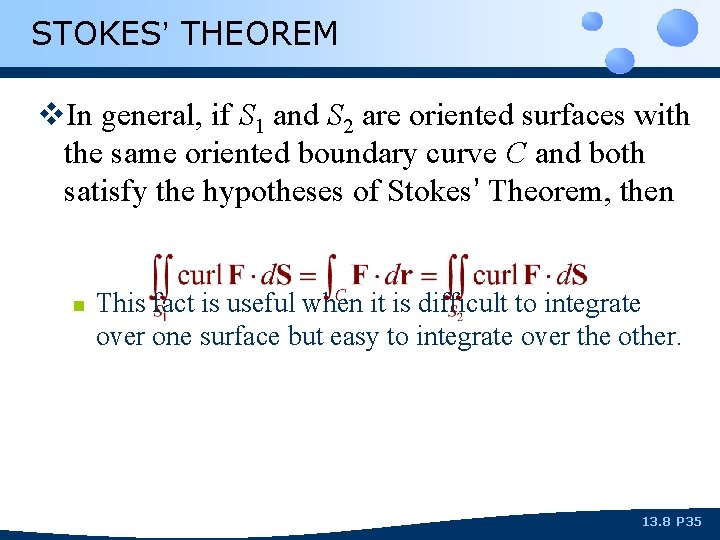

STOKES’ THEOREM v. In general, if S 1 and S 2 are oriented surfaces with the same oriented boundary curve C and both satisfy the hypotheses of Stokes’ Theorem, then n This fact is useful when it is difficult to integrate over one surface but easy to integrate over the other. 13. 8 P 35

CURL VECTOR v. We now use Stokes’ Theorem to throw some light on the meaning of the curl vector. n Suppose that C is an oriented closed curve and v represents the velocity field in fluid flow. 13. 8 P 36

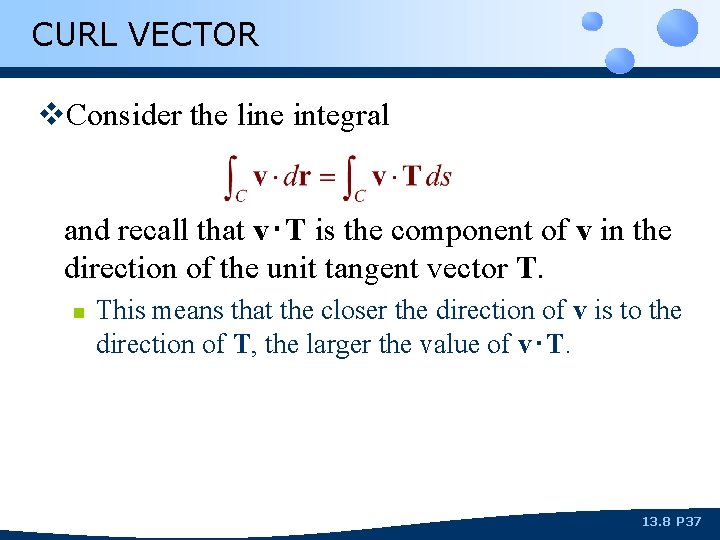

CURL VECTOR v. Consider the line integral and recall that v‧T is the component of v in the direction of the unit tangent vector T. n This means that the closer the direction of v is to the direction of T, the larger the value of v‧T. 13. 8 P 37

CIRCULATION v. Thus, is a measure of the tendency of the fluid to move around C. n n It is called the circulation of v around C. See Figure 5. 13. 8 P 38

CURL VECTOR v. Now, let P 0(x 0, y 0, z 0) be a point in the fluid. v. Sa be a small disk with radius a and center P 0. n Then, (curl F)(P) ≈ (curl F)(P 0) for all points P on Sa because curl F is continuous. 13. 8 P 39

CURL VECTOR v. Thus, by Stokes’ Theorem, we get the following approximation to the circulation around the boundary circle Ca: 13. 8 P 40

CURL VECTOR v. The approximation becomes better as a → 0. v. Thus, we have: 13. 8 P 41

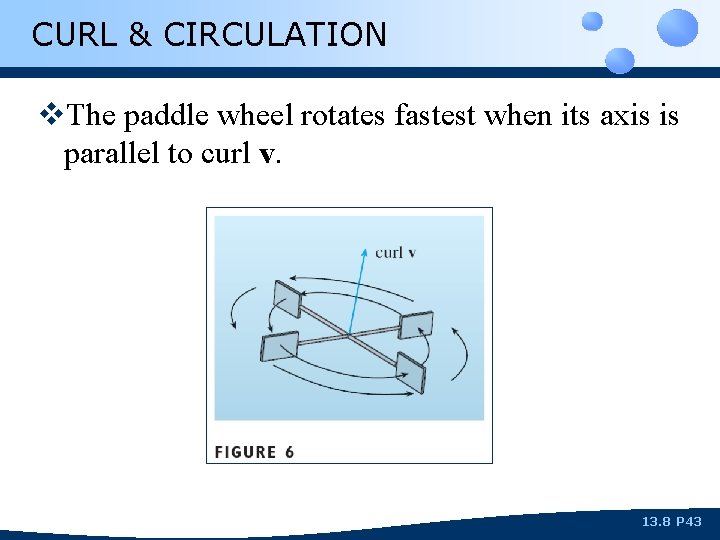

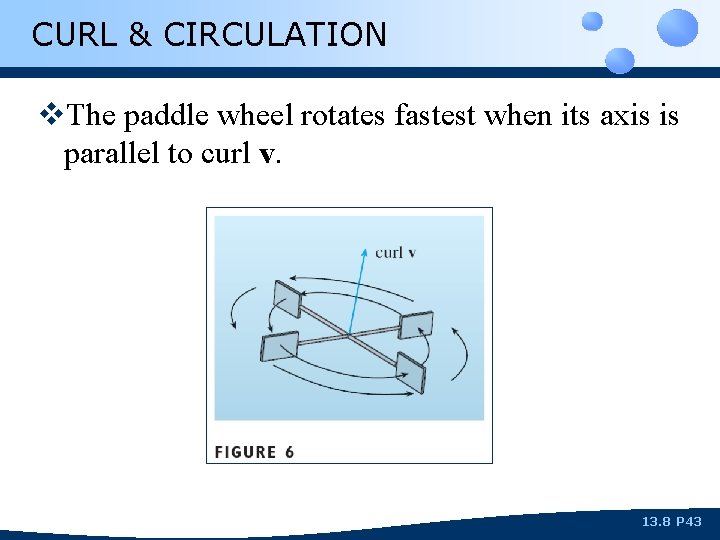

CURL & CIRCULATION v. Equation 4 gives the relationship between the curl and the circulation. n n It shows that curl v‧n is a measure of the rotating effect of the fluid about the axis n. The curling effect is greatest about the axis parallel to curl v. 13. 8 P 42

CURL & CIRCULATION v. The paddle wheel rotates fastest when its axis is parallel to curl v. 13. 8 P 43

CLOSED CURVES v. Finally, we mention that Stokes’ Theorem can be used to prove Theorem 4 in Section 13. 5: n If curl F = 0 on all of , then F is conservative. 13. 8 P 44

CLOSED CURVES v. From Theorems 3 and 4 in Section 13. 3, we know that F is conservative if for every closed path C. n n Given C, suppose we can find an orientable surface S whose boundary is C. This can be done, but the proof requires advanced techniques. 13. 8 P 45

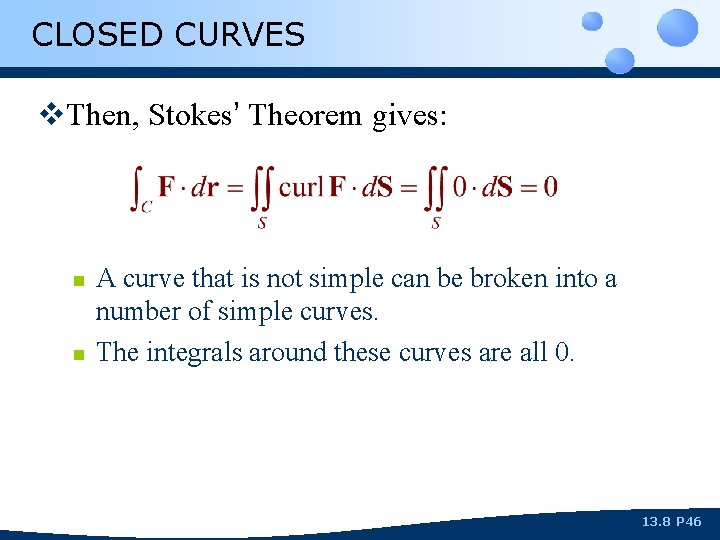

CLOSED CURVES v. Then, Stokes’ Theorem gives: n n A curve that is not simple can be broken into a number of simple curves. The integrals around these curves are all 0. 13. 8 P 46

CLOSED CURVES v. Adding these integrals, we obtain: for any closed curve C. 13. 8 P 47