Scheduling Chapter 10 Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

![List Scheduling Algorithm I Idea: Keep a collection of worklists W[c], one per cycle List Scheduling Algorithm I Idea: Keep a collection of worklists W[c], one per cycle](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/d01657e533ccaf7e2e3bd49d5b3a4247/image-16.jpg)

![List Scheduling Algorithm II while Wcount > 0 do begin while W[c. W] = List Scheduling Algorithm II while Wcount > 0 do begin while W[c. W] =](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/d01657e533ccaf7e2e3bd49d5b3a4247/image-17.jpg)

- Slides: 49

Scheduling Chapter 10 Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Introduction • We shall discuss: — Straight line scheduling — Trace Scheduling — Kernel Scheduling (Software Pipelining) — Vector Unit Scheduling — Cache coherence in coprocessors Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Introduction • Scheduling: Mapping of parallelism within the constraints of limited available parallel resources • Best Case Scenario: All the uncovered parallelism can be exploited by the machine • In general, we must sacrifice some execution time to fit a program within the available resources • Our goal: Minimize the amount of execution time sacrificed Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Introduction • Variants of the scheduling problem: • Will concentrate on instruction scheduling (fine grained parallelism) — Instruction scheduling: Specifying the order in which instructions will be executed — Vector unit scheduling: Make most effective use of the instructions and capabilities of a vector unit. Requires pattern recognition and synchronization minimization Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Introduction • Categories of processors supporting fine-grained parallelism: — VLIW — Superscalar processors Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Introduction • Scheduling in VLIW and Superscalar architectures: • Standard approach: — Order instruction stream so that as many function units as possible are being used on every cycle — Emit a sequential stream of instructions — Reorder this sequential stream to utilize available parallelism — Reordering must preserve dependences Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Introduction • Issue: Creating a sequential stream must consider available resources. This may create artificial dependences a = b + c + d + e • One possible sequential stream: add a, b, c add a, a, d add a, a, e • And, another: add r 1, b, c add r 2, d, e add a, r 1, r 2 Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Fundamental conflict in scheduling • Fundamental conflict in scheduling: — If the original instruction stream takes into account available resources, will create artificial dependences — If not, then there may not be enough resources to correctly execute the stream Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

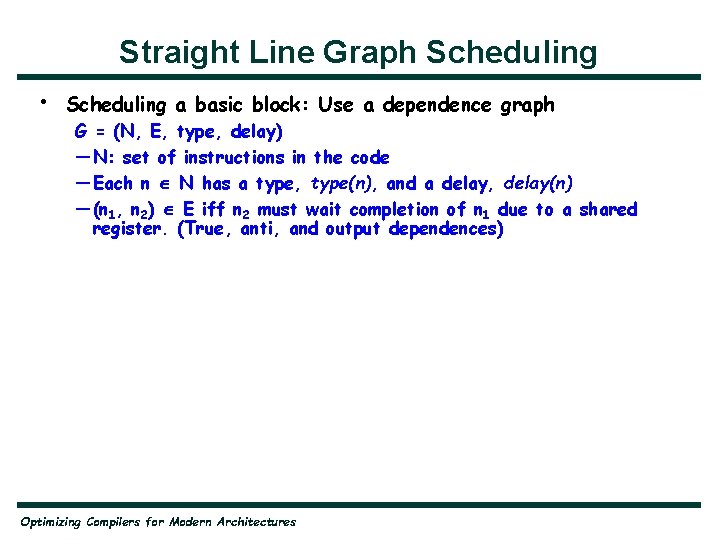

Machine Model • • Machine contains a number of issue units • Ikj denotes the jth unit of type k • Number of units of type k = mk • Total number of issue units: M = Issue unit has an associated type and a delay where, l = number of issue-unit types in the machine Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Machine Model • • We will assume a VLIW model • Note that code can be generated easily for an equivalent superscalar machine Goal of compiler: select set of M instructions for each cycle such that the number of instructions of type k is mk Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Straight Line Graph Scheduling • Scheduling a basic block: Use a dependence graph G = (N, E, type, delay) — N: set of instructions in the code — Each n N has a type, type(n), and a delay, delay(n) — (n 1, n 2) E iff n 2 must wait completion of n 1 due to a shared register. (True, anti, and output dependences) Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Straight Line Graph Scheduling • A correct schedule is a mapping, S, from vertices in the graph to nonnegative integers representing cycle numbers such that: 1. S(n) 0 for all n N, 2. If (n 1, n 2) E, S(n 1) + delay(n 1) S(n 2), and 3. For any type t, no more than mt vertices of type t are mapped to a given integer. • The length of a schedule, S, denoted L(S) is defined as: L(S) = (S(n) + delay(n)) • Goal of straight-line scheduling: Find a shortest possible correct schedule. A straight line schedule is said to be optimal if: L(S) L(S 1), correct schedules S 1 Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

List Scheduling • Use variant of topological sort: — Maintain a list of instructions which have no predecessors in the graph — Schedule these instructions — This will allow other instructions to be added to the list Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

List Scheduling • Algorithm for list scheduling: — Schedule an instruction at the first opportunity after all instructions it depends on have completed — count array determines how many predecessors are still to be scheduled — earliest array maintains the earliest cycle on which the instruction can be scheduled — Maintain a number of worklists which hold instructions to be scheduled for a particular cycle number. How many worklists are required? Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

List Scheduling • How shall we select instructions from the worklist? — Random selection — Selection based on other criteria: Worklists are priority queues. Highest Level First (HLF) heuristic schedules more critical instructions first Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

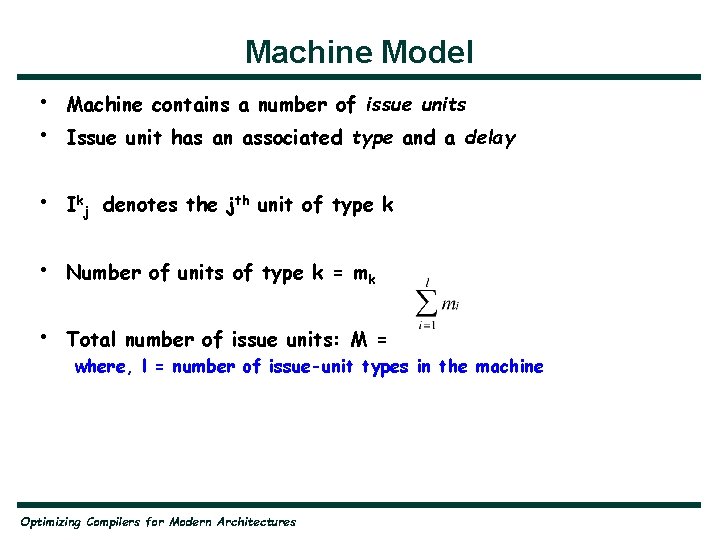

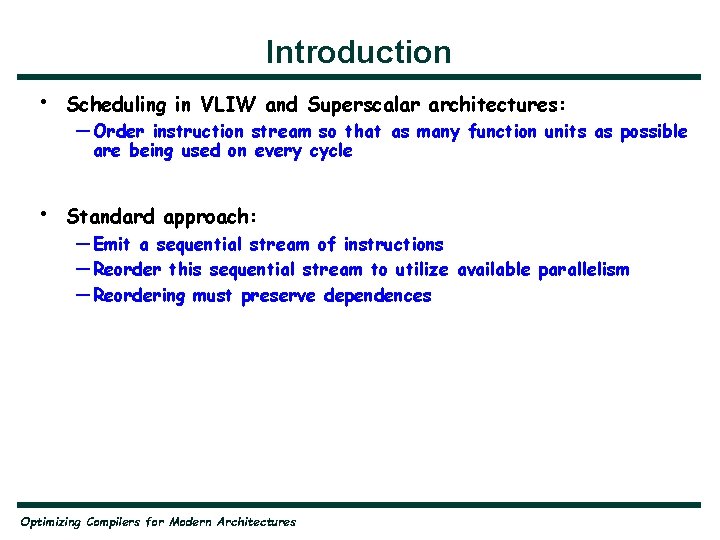

![List Scheduling Algorithm I Idea Keep a collection of worklists Wc one per cycle List Scheduling Algorithm I Idea: Keep a collection of worklists W[c], one per cycle](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/d01657e533ccaf7e2e3bd49d5b3a4247/image-16.jpg)

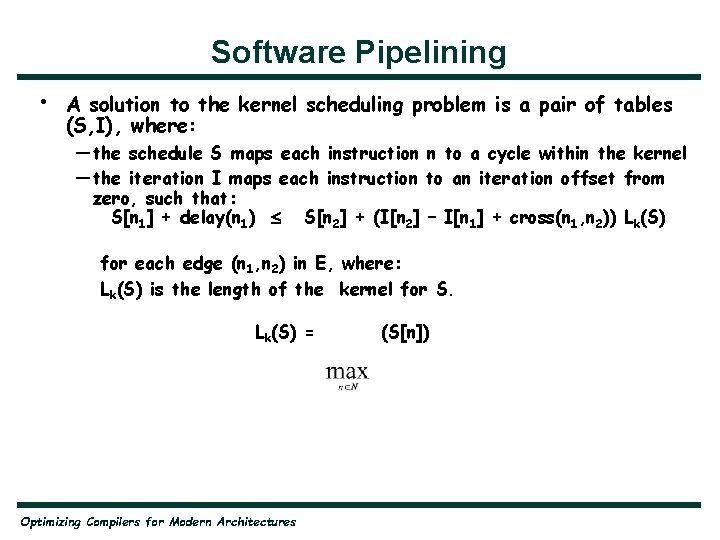

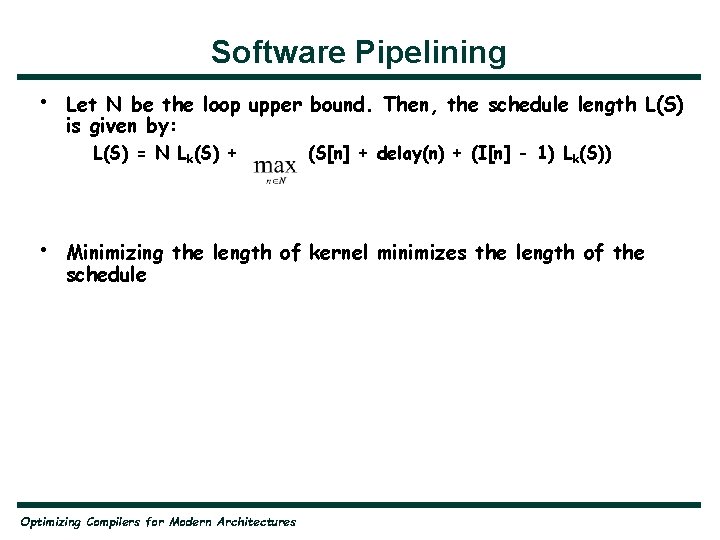

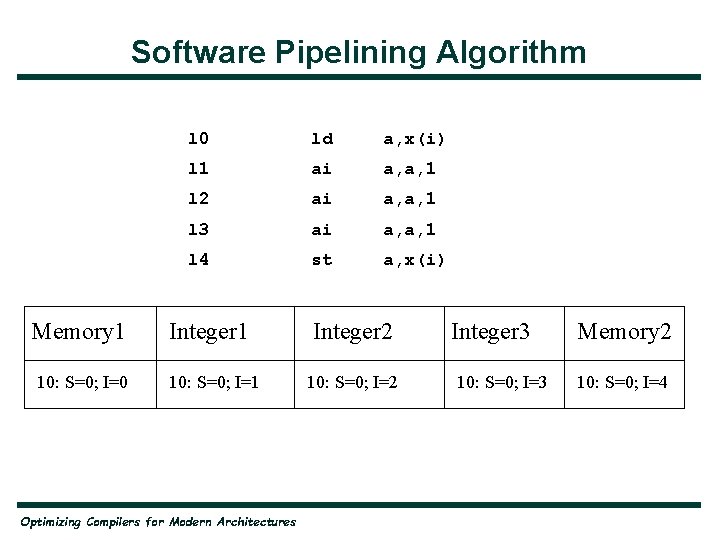

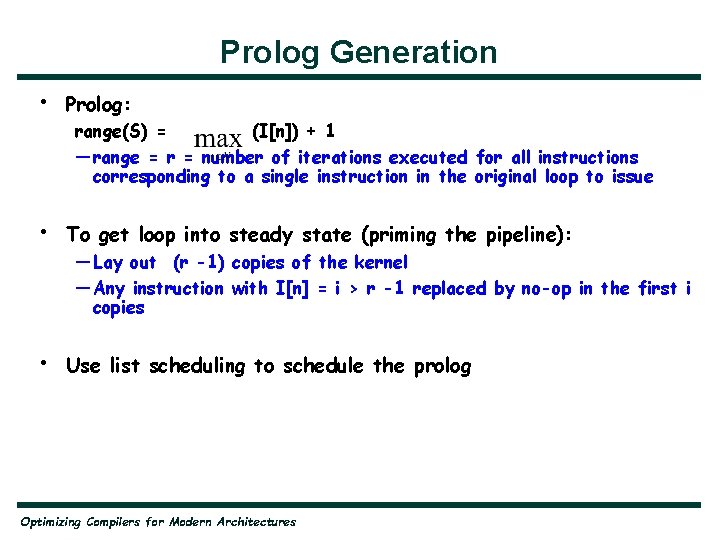

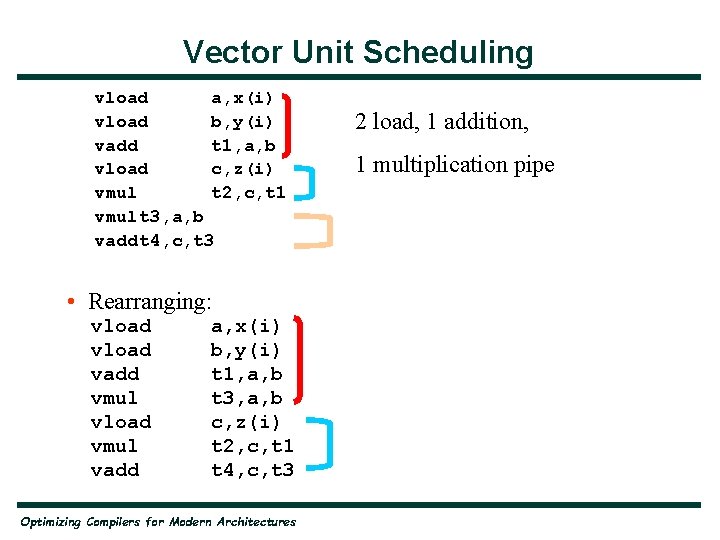

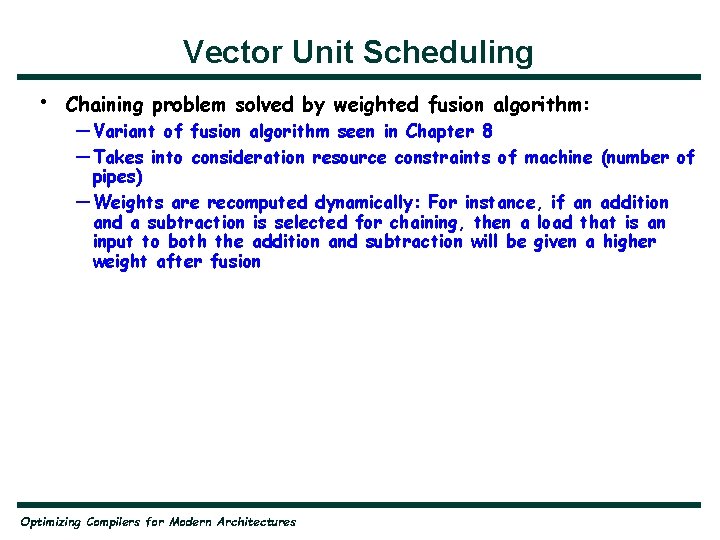

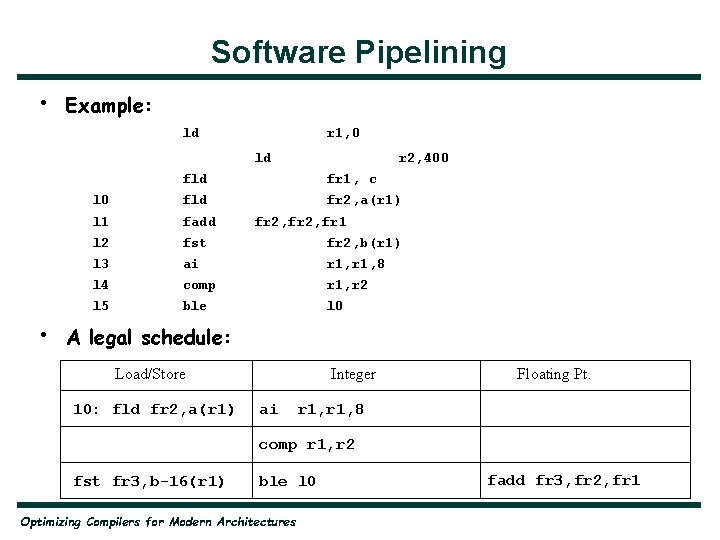

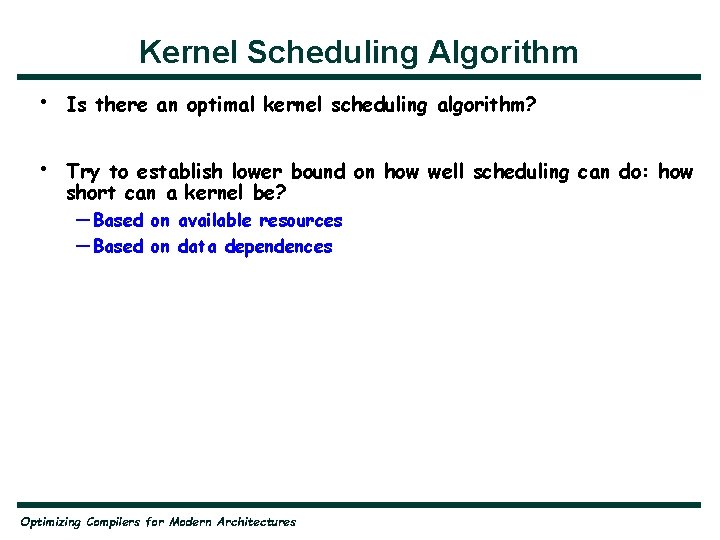

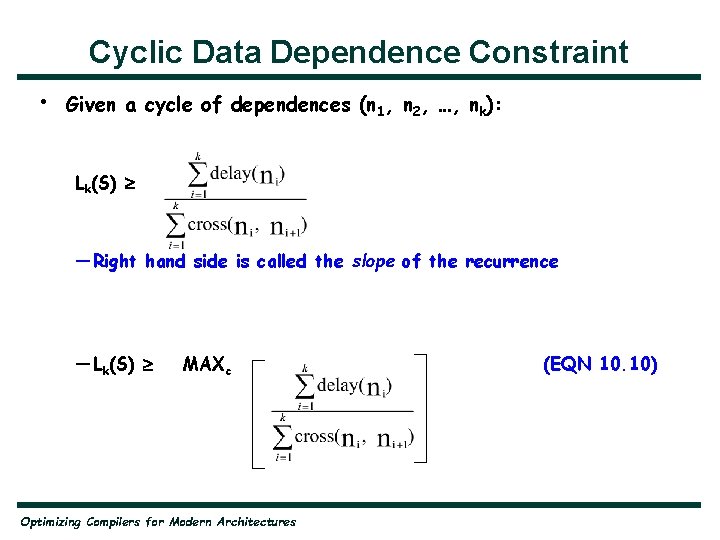

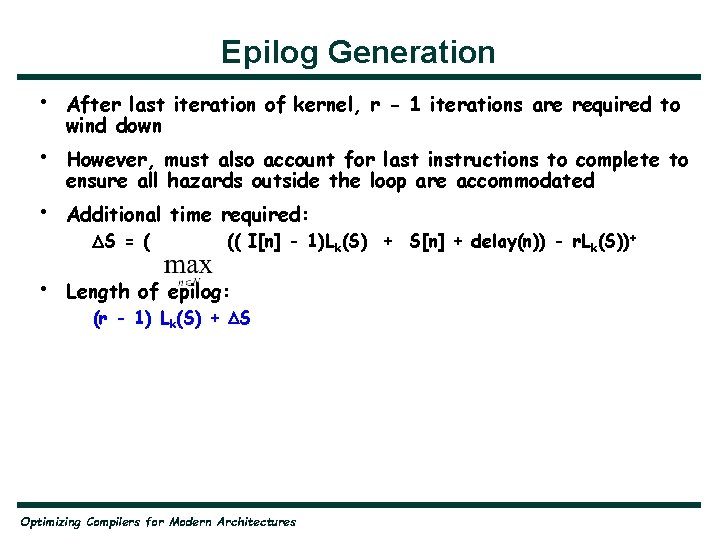

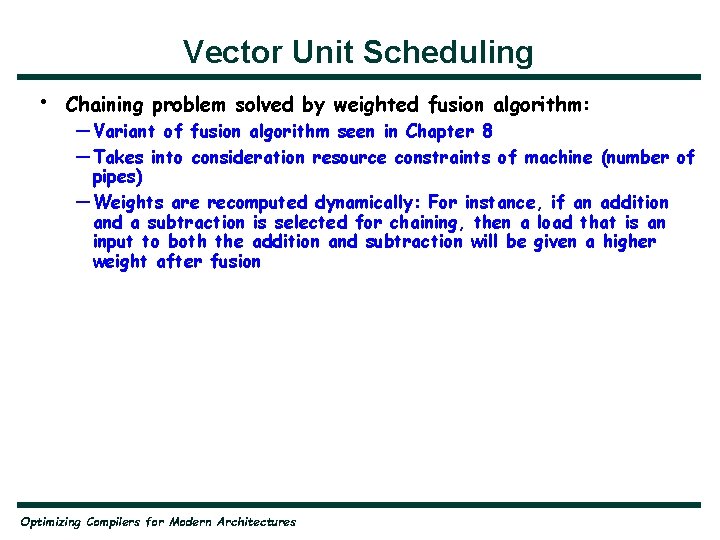

List Scheduling Algorithm I Idea: Keep a collection of worklists W[c], one per cycle — We need Max. C = max delay + 1 such worklists Code: for each n N do begin count[n] : = 0; earliest[n] = 0 end for each (n 1, n 2) E do begin count[n 2] : = count[n 2] + 1; successors[n 1] : = successors[n 1] {n 2}; end for i : = 0 to Max. C – 1 do W[i] : = ; Wcount : = 0; for each n N do if count[n] = 0 then begin W[0] : = W[0] {n}; Wcount : = Wcount + 1; end c : = 0; // c is the cycle number c. W : = 0; // c. W is the number of the worklist for cycle c instr[c] : = ; Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

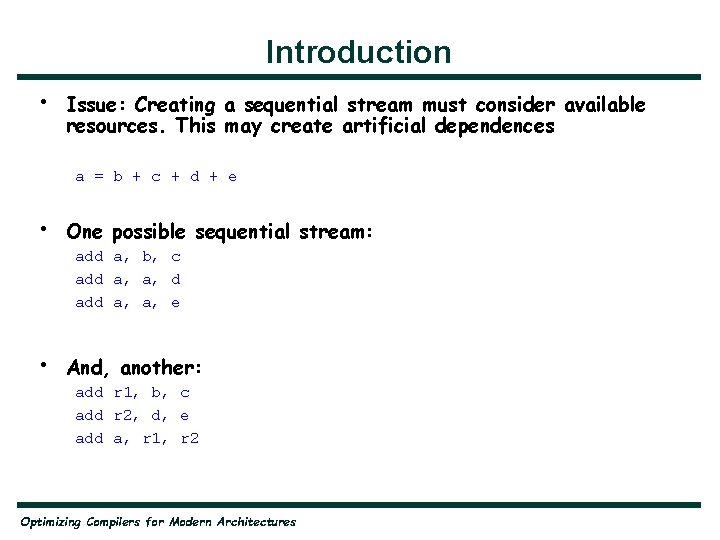

![List Scheduling Algorithm II while Wcount 0 do begin while Wc W List Scheduling Algorithm II while Wcount > 0 do begin while W[c. W] =](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/d01657e533ccaf7e2e3bd49d5b3a4247/image-17.jpg)

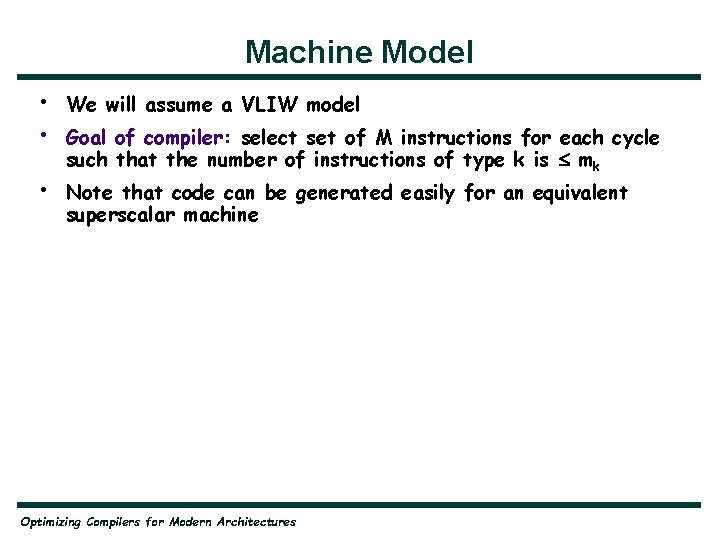

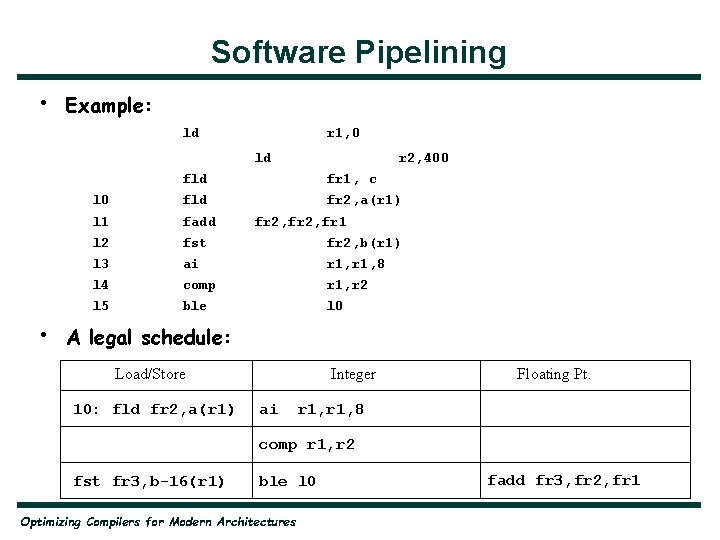

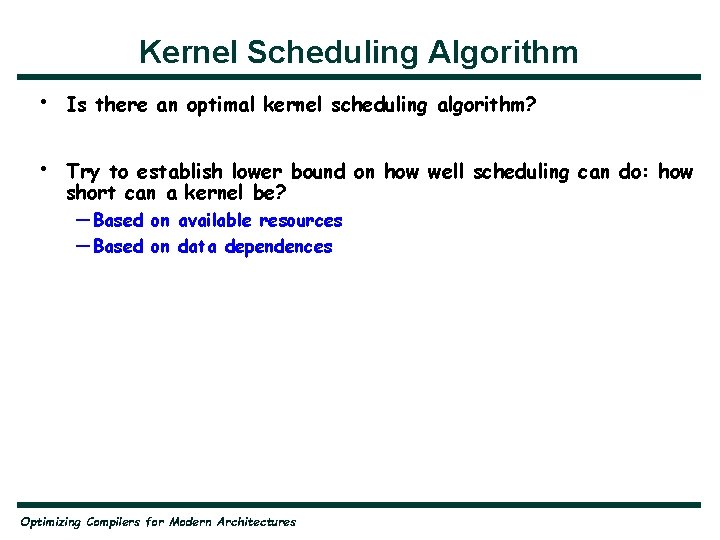

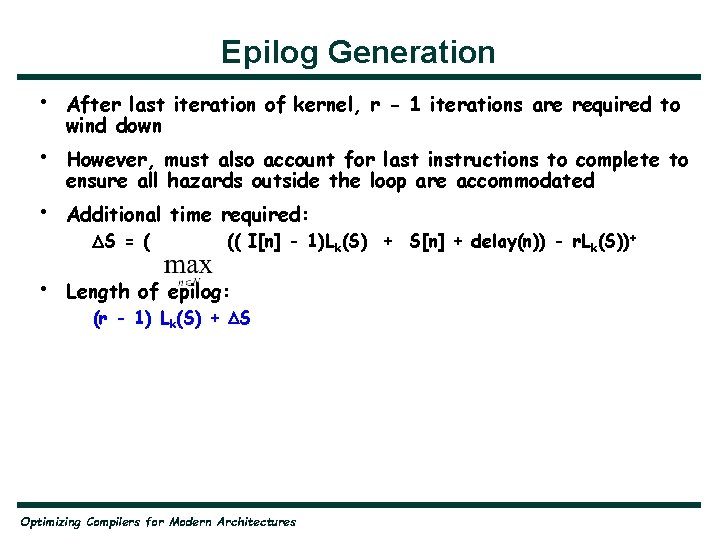

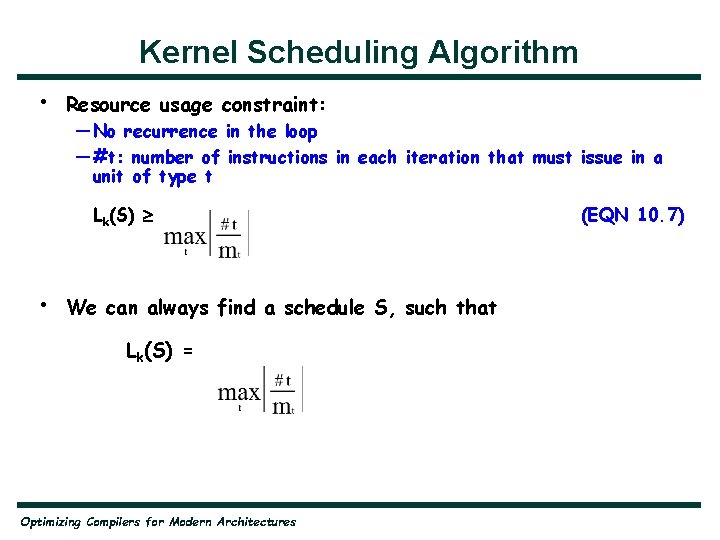

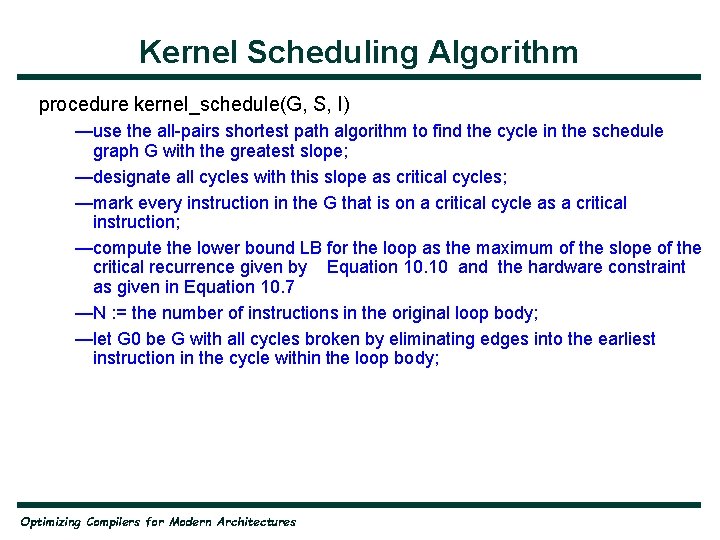

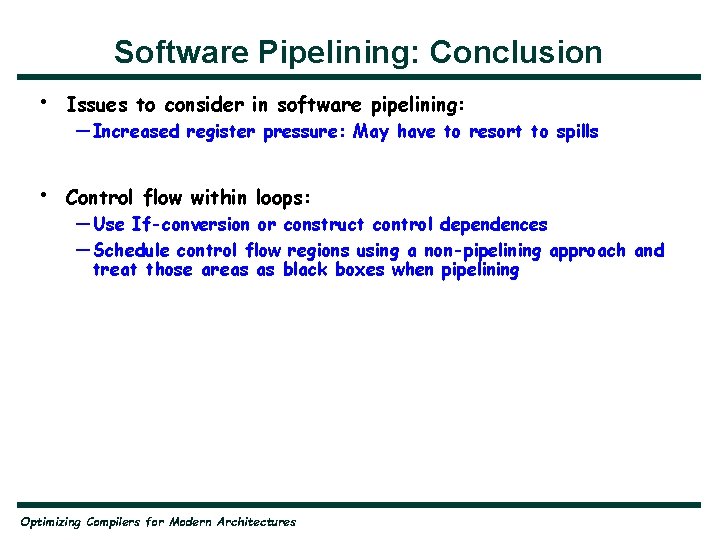

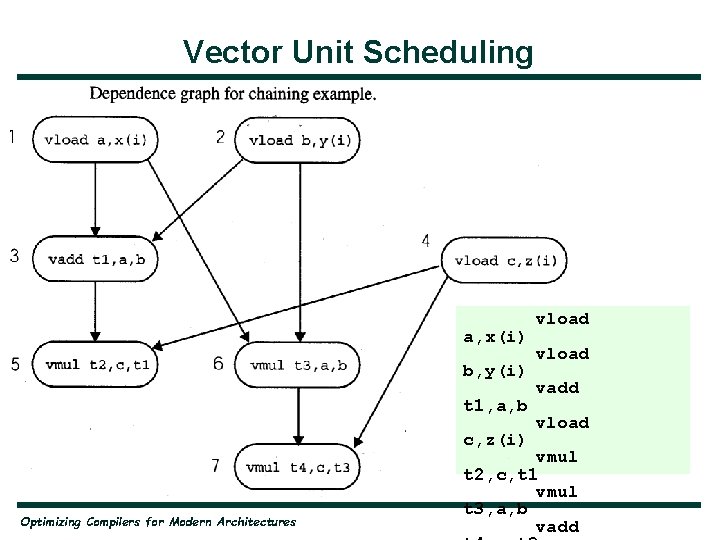

List Scheduling Algorithm II while Wcount > 0 do begin while W[c. W] = do begin c : = c + 1; instr[c] : = ; c. W : = mod(c. W+1, Max. C); end nextc : = mod(c+1, Max. C); while W[c. W] ≠ do begin select and remove an arbitrary instruction x from W[c. W]; Priority if free issue units of type(x) on cycle c then begin instr[c] : = instr[c] {x}; Wcount : = Wcount - 1; for each y successors[x] do begin count[y] : = count[y] – 1; earliest[y] : = max(earliest[y], c+delay(x)); if count[y] = 0 then begin loc : = mod(earliest[y], Max. C); W[loc] : = W[loc] {y}; Wcount : = Wcount + 1; end else W[nextc] : = W[nextc] {x}; end Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Trace Scheduling • • Problem with list scheduling: Transition points between basic blocks • Results in significant overhead! Must insert enough instructions at the end of a basic block to ensure that results are available on entry into next basic block • • Alternative to list scheduling: trace scheduling • • Trace Scheduling schedules an entire trace at a time • Trace: is a collection of basic blocks that form a single path through all or part of the program Traces are chosen based on their expected frequencies of execution Caveat: Cannot schedule cyclic graphs. Loops must be unrolled Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

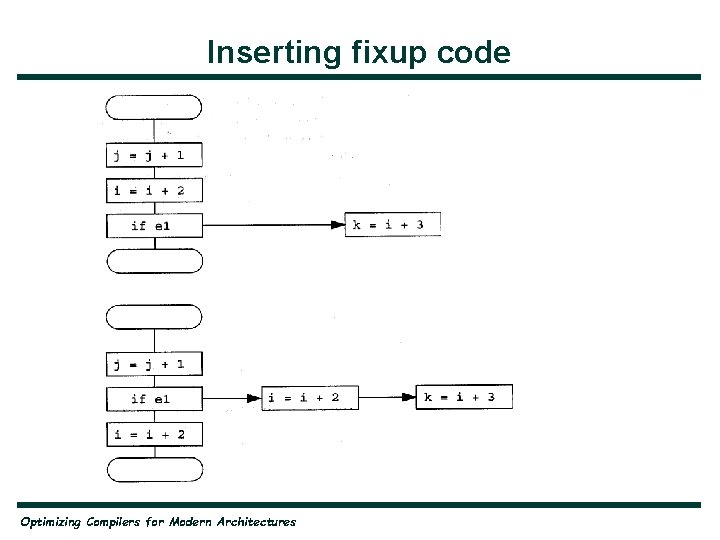

Trace Scheduling • Three steps for trace scheduling: — Selecting a trace — Scheduling the trace — Inserting fixup code Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

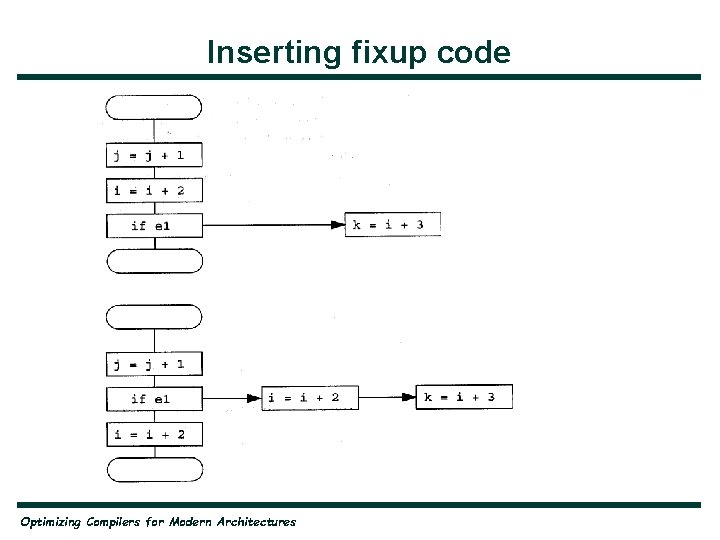

Inserting fixup code Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

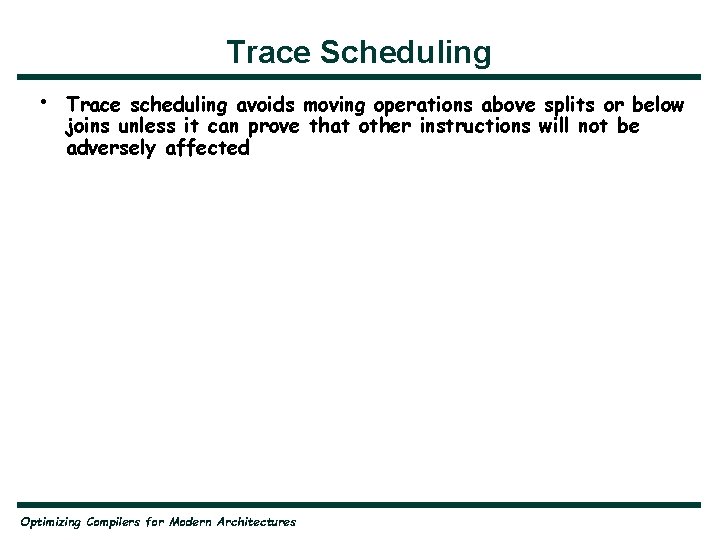

Trace Scheduling • Trace scheduling avoids moving operations above splits or below joins unless it can prove that other instructions will not be adversely affected Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Trace Scheduling • • Trace scheduling will always converge However, in the worst case, a very large amount of fixup code may result — Worst case: operations increase to O(n en) Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Straight-line Scheduling: Conclusion • Issues in straight-line scheduling: — Relative order of register allocation and instruction scheduling — Dealing with loads and stores: Without sophisticated analysis, almost no movement is possible among memory references Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Kernel Scheduling • Drawback of straight-line scheduling: • Kernel scheduling: Try to maximize parallelism across loop iterations — Loops are unrolled. — Ignores parallelism among loop iterations Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Kernel Scheduling • Schedule a loop in three parts: • The kernel scheduling problem seeks to find a minimal-length kernel for a given loop • Issue: loops with small iteration counts? — a kernel: includes code that must be executed on every cycle of the loop — a prolog: which includes code that must be performed before steady state can be reached — an epilog, which contains code that must be executed to finish the loop once the kernel can no longer be executed Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Kernel Scheduling: Software Pipelining • A kernel scheduling problem is a graph: G = (N, E, delay, type, cross) where cross (n 1, n 2) defined for each edge in E is the number of iterations crossed by the dependence relating n 1 and n 2 • • Temporal movement of instructions through loop iterations Software Pipelining: Body of one loop iteration is pipelined across multiple iterations. Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Software Pipelining • A solution to the kernel scheduling problem is a pair of tables (S, I), where: — the schedule S maps each instruction n to a cycle within the kernel — the iteration I maps each instruction to an iteration offset from zero, such that: S[n 1] + delay(n 1) S[n 2] + (I[n 2] – I[n 1] + cross(n 1, n 2)) Lk(S) for each edge (n 1, n 2) in E, where: Lk(S) is the length of the kernel for S. Lk(S) = Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures (S[n])

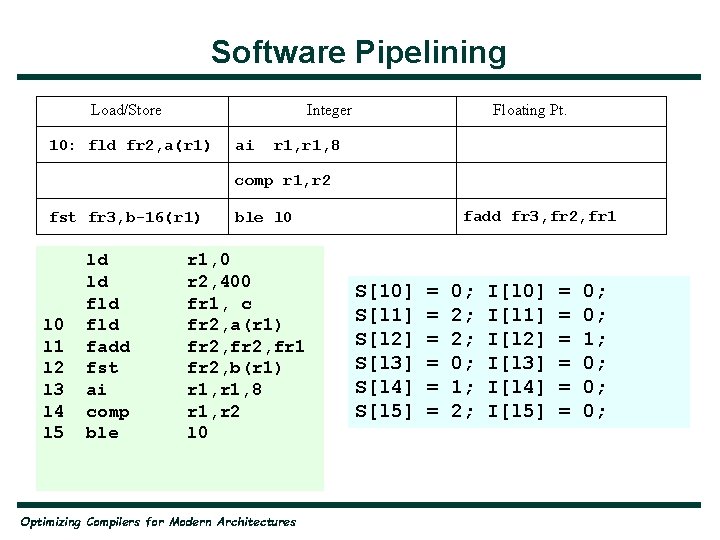

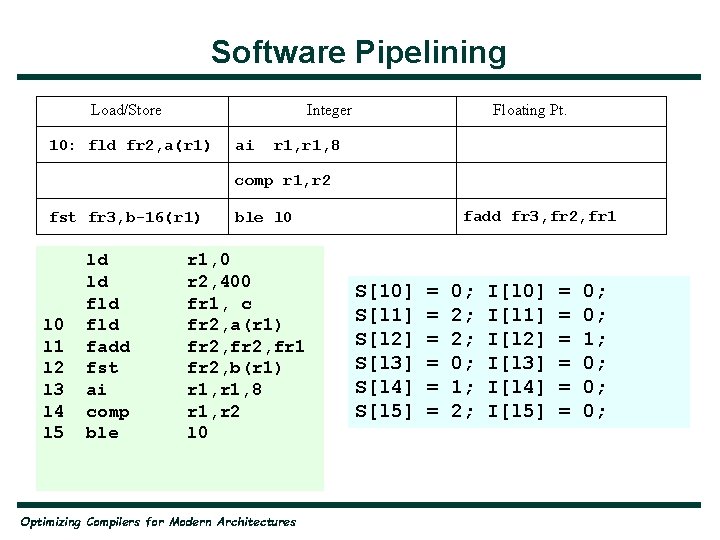

Software Pipelining • Example: ld r 1, 0 ld • r 2, 400 fld fr 1, c l 0 fld fr 2, a(r 1) l 1 fadd l 2 fst fr 2, b(r 1) l 3 ai r 1, 8 l 4 comp r 1, r 2 l 5 ble l 0 fr 2, fr 1 A legal schedule: Load/Store 10: fld fr 2, a(r 1) Integer ai Floating Pt. r 1, 8 comp r 1, r 2 fst fr 3, b-16(r 1) ble l 0 Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures fadd fr 3, fr 2, fr 1

Software Pipelining Load/Store Integer 10: fld fr 2, a(r 1) ai Floating Pt. r 1, 8 comp r 1, r 2 fst fr 3, b-16(r 1) l 0 l 1 l 2 l 3 l 4 l 5 ld ld fld fadd fst ai comp ble fadd fr 3, fr 2, fr 1 ble l 0 r 1, 0 r 2, 400 fr 1, c fr 2, a(r 1) fr 2, fr 1 fr 2, b(r 1) r 1, 8 r 1, r 2 l 0 Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures S[10] S[l 1] S[l 2] S[l 3] S[l 4] S[l 5] = = = 0; 2; 2; 0; 1; 2; I[l 0] I[l 1] I[l 2] I[l 3] I[l 4] I[l 5] = = = 0; 0; 1; 0; 0; 0;

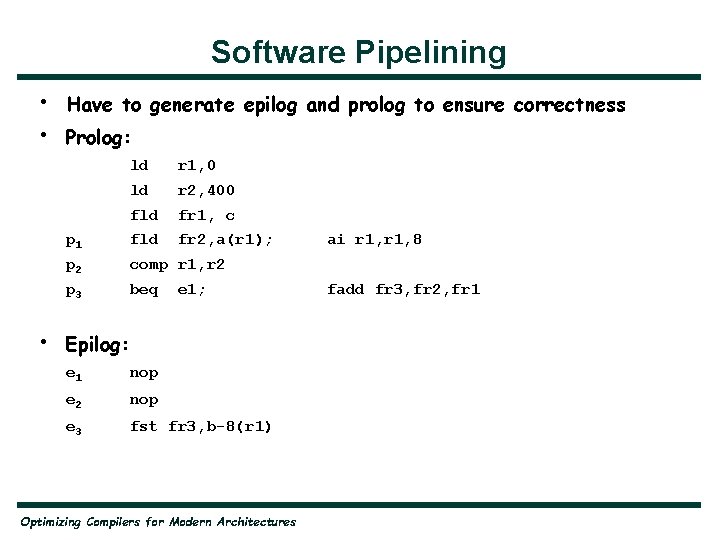

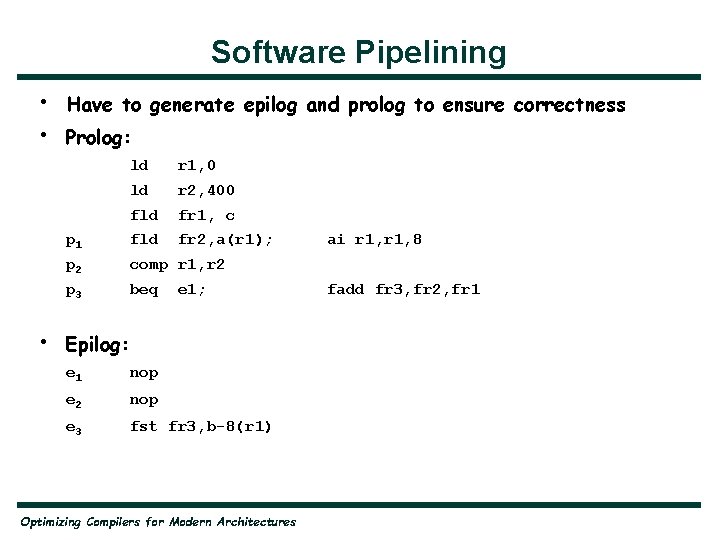

Software Pipelining • • • Have to generate epilog and prolog to ensure correctness Prolog: ld r 1, 0 ld r 2, 400 fld fr 1, c p 1 fld fr 2, a(r 1); p 2 comp r 1, r 2 p 3 beq e 1; Epilog: e 1 nop e 2 nop e 3 fst fr 3, b-8(r 1) Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures ai r 1, 8 fadd fr 3, fr 2, fr 1

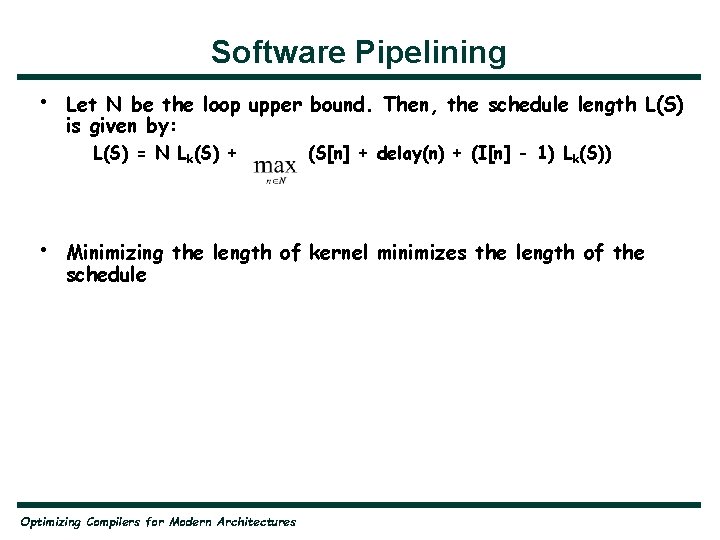

Software Pipelining • Let N be the loop upper bound. Then, the schedule length L(S) is given by: L(S) = N Lk(S) + • (S[n] + delay(n) + (I[n] - 1) Lk(S)) Minimizing the length of kernel minimizes the length of the schedule Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

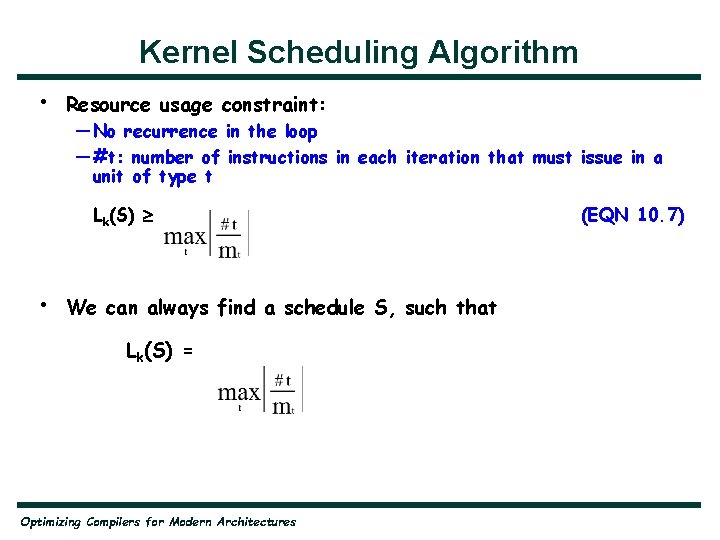

Kernel Scheduling Algorithm • Is there an optimal kernel scheduling algorithm? • Try to establish lower bound on how well scheduling can do: how short can a kernel be? — Based on available resources — Based on data dependences Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Kernel Scheduling Algorithm • Resource usage constraint: — No recurrence in the loop — #t: number of instructions in each iteration that must issue in a unit of type t Lk(S) • We can always find a schedule S, such that Lk(S) = Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures (EQN 10. 7)

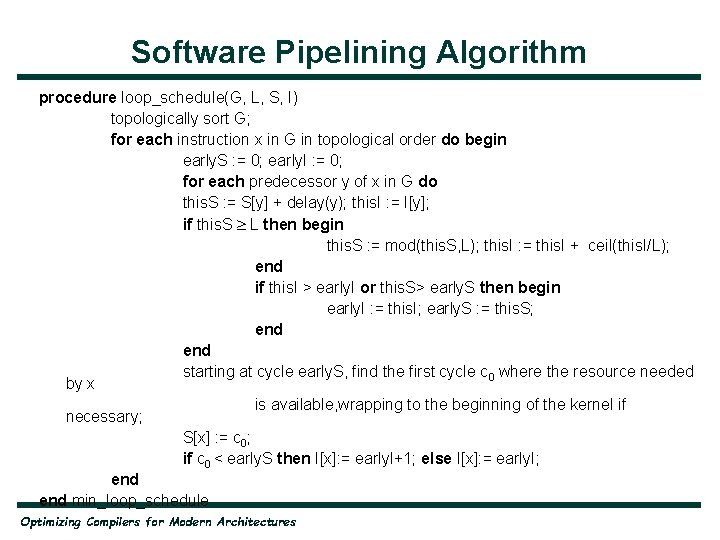

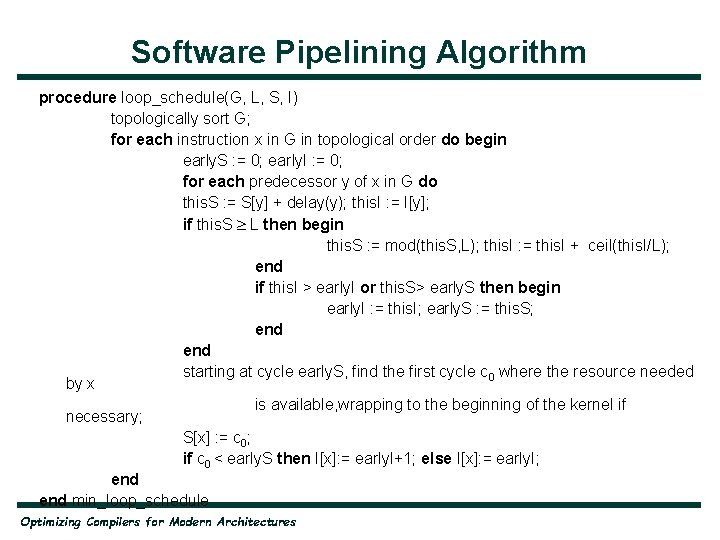

Software Pipelining Algorithm procedure loop_schedule(G, L, S, I) topologically sort G; for each instruction x in G in topological order do begin early. S : = 0; early. I : = 0; for each predecessor y of x in G do this. S : = S[y] + delay(y); this. I : = I[y]; if this. S L then begin this. S : = mod(this. S, L); this. I : = this. I + ceil(this. I/L); end if this. I > early. I or this. S> early. S then begin early. I : = this. I; early. S : = this. S; end starting at cycle early. S, find the first cycle c 0 where the resource needed by x is available, wrapping to the beginning of the kernel if necessary; S[x] : = c 0; if c 0 < early. S then I[x]: = early. I+1; else I[x]: = early. I; end min_loop_schedule Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

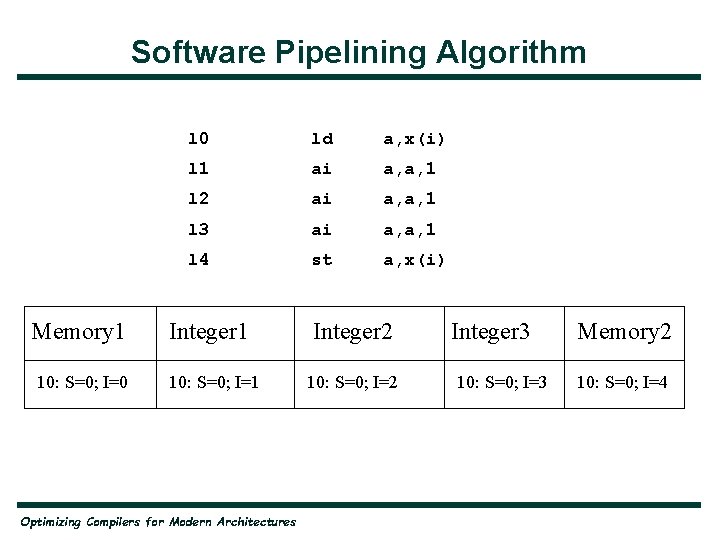

Software Pipelining Algorithm Memory 1 10: S=0; I=0 l 0 ld a, x(i) l 1 ai a, a, 1 l 2 ai a, a, 1 l 3 ai a, a, 1 l 4 st a, x(i) Integer 1 10: S=0; I=1 Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures Integer 2 10: S=0; I=2 Integer 3 10: S=0; I=3 Memory 2 10: S=0; I=4

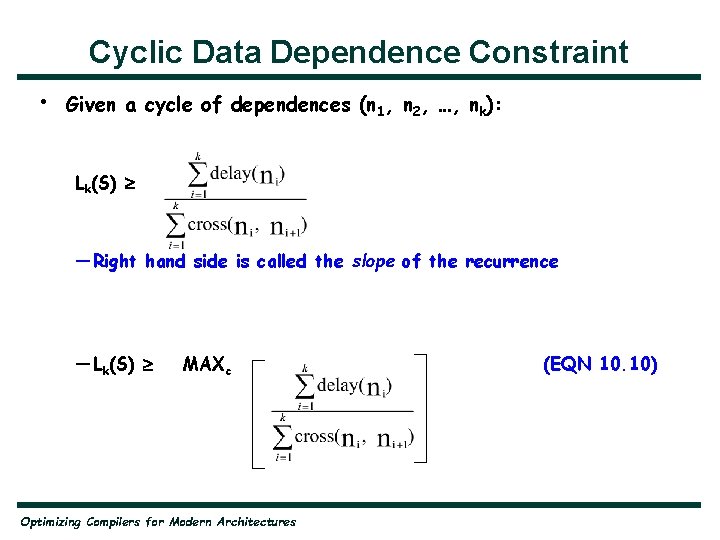

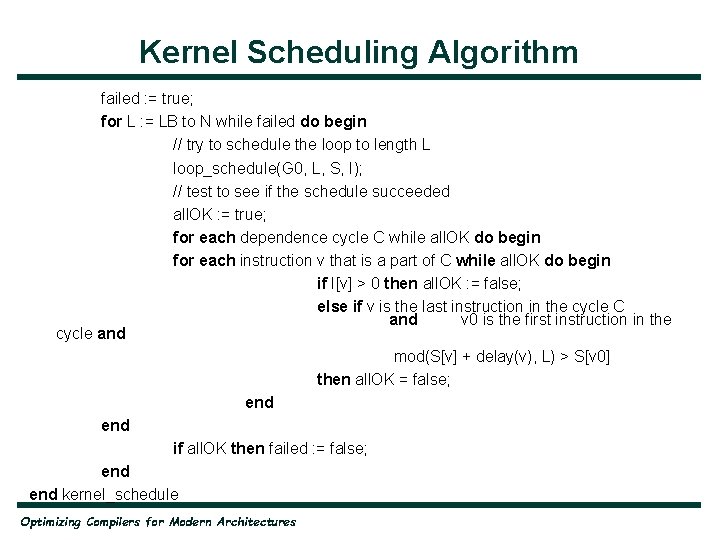

Cyclic Data Dependence Constraint • Given a cycle of dependences (n 1, n 2, …, nk): Lk(S) — Right hand side is called the slope of the recurrence — Lk(S) MAXc Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures (EQN 10. 10)

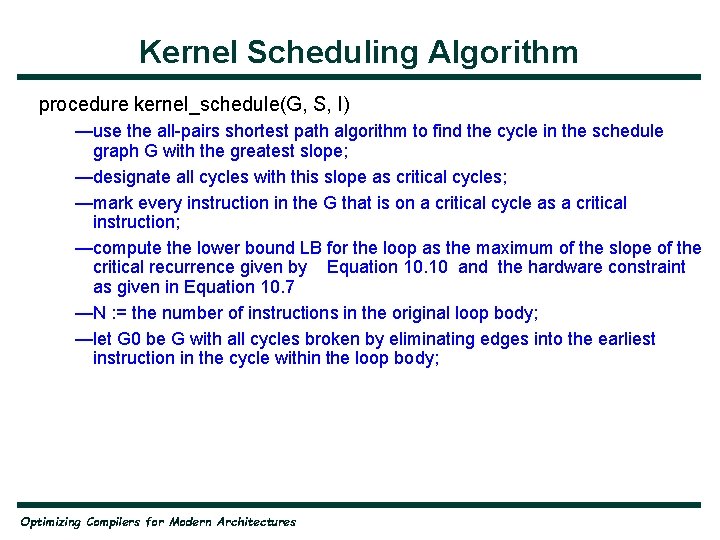

Kernel Scheduling Algorithm procedure kernel_schedule(G, S, I) —use the all-pairs shortest path algorithm to find the cycle in the schedule graph G with the greatest slope; —designate all cycles with this slope as critical cycles; —mark every instruction in the G that is on a critical cycle as a critical instruction; —compute the lower bound LB for the loop as the maximum of the slope of the critical recurrence given by Equation 10. 10 and the hardware constraint as given in Equation 10. 7 —N : = the number of instructions in the original loop body; —let G 0 be G with all cycles broken by eliminating edges into the earliest instruction in the cycle within the loop body; Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

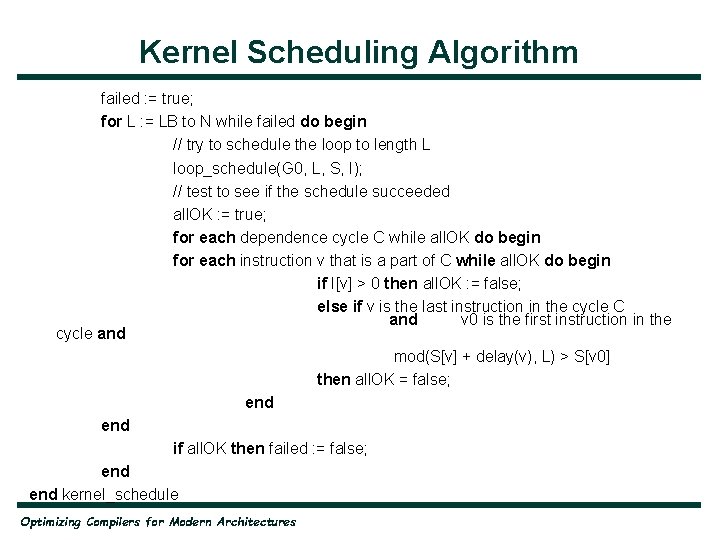

Kernel Scheduling Algorithm failed : = true; for L : = LB to N while failed do begin // try to schedule the loop to length L loop_schedule(G 0, L, S, I); // test to see if the schedule succeeded all. OK : = true; for each dependence cycle C while all. OK do begin for each instruction v that is a part of C while all. OK do begin if I[v] > 0 then all. OK : = false; else if v is the last instruction in the cycle C and v 0 is the first instruction in the cycle and mod(S[v] + delay(v), L) > S[v 0] then all. OK = false; end if all. OK then failed : = false; end kernel_schedule Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

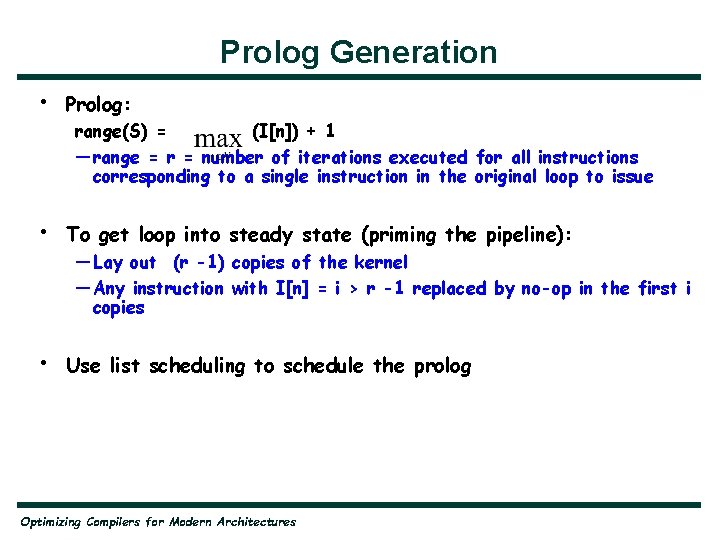

Prolog Generation • Prolog: • To get loop into steady state (priming the pipeline): • Use list scheduling to schedule the prolog range(S) = (I[n]) + 1 — range = r = number of iterations executed for all instructions corresponding to a single instruction in the original loop to issue — Lay out (r -1) copies of the kernel — Any instruction with I[n] = i > r -1 replaced by no-op in the first i copies Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Epilog Generation • • After last iteration of kernel, r - 1 iterations are required to wind down However, must also account for last instructions to complete to ensure all hazards outside the loop are accommodated Additional time required: S = ( (( I[n] - 1)Lk(S) + S[n] + delay(n)) - r. Lk(S))+ Length of epilog: (r - 1) Lk(S) + S Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

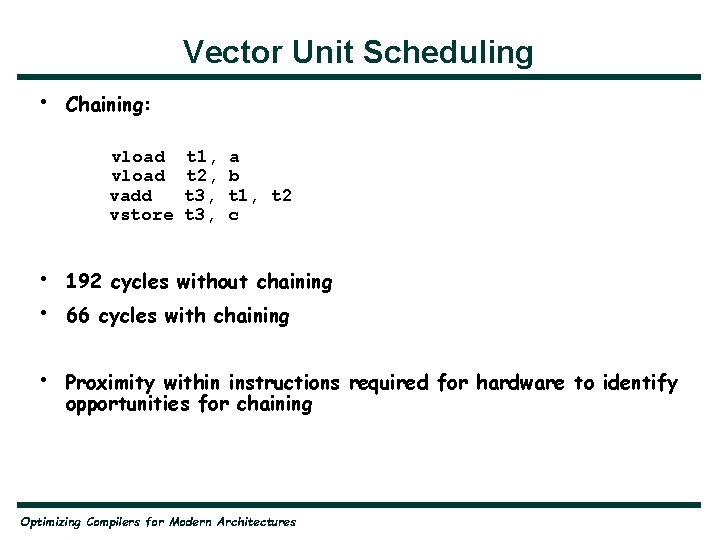

Software Pipelining: Conclusion • Issues to consider in software pipelining: • Control flow within loops: — Increased register pressure: May have to resort to spills — Use If-conversion or construct control dependences — Schedule control flow regions using a non-pipelining approach and treat those areas as black boxes when pipelining Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

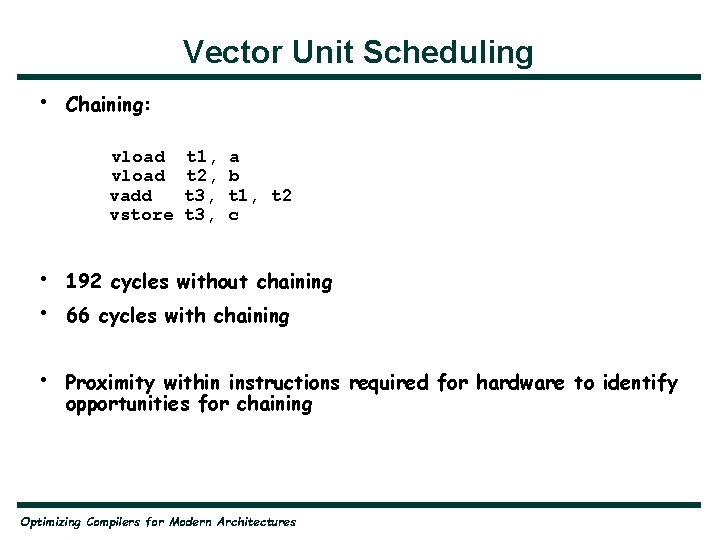

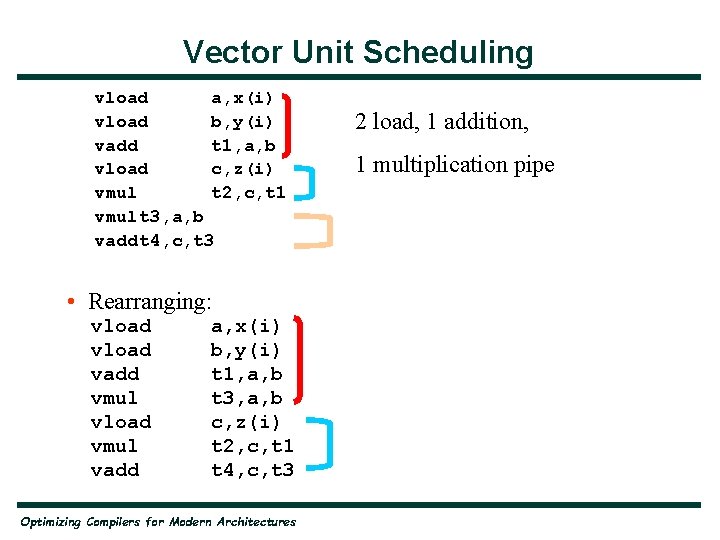

Vector Unit Scheduling • Chaining: vload vadd vstore t 1, t 2, t 3, a b t 1, t 2 c • • 192 cycles without chaining • Proximity within instructions required for hardware to identify opportunities for chaining 66 cycles with chaining Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

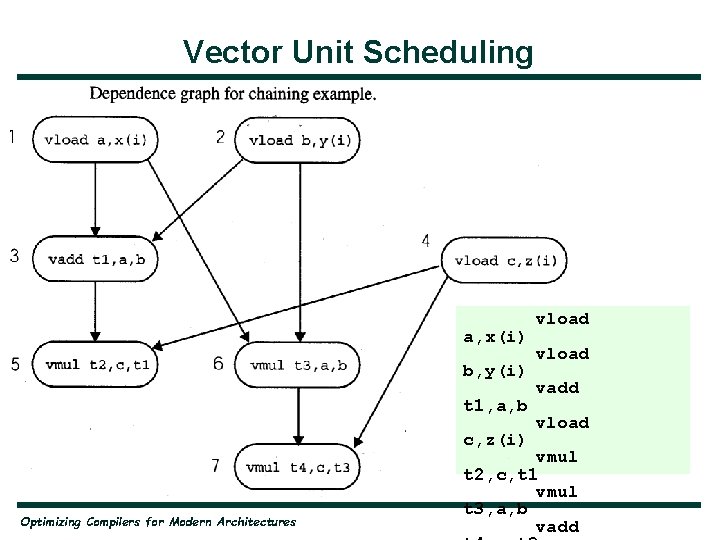

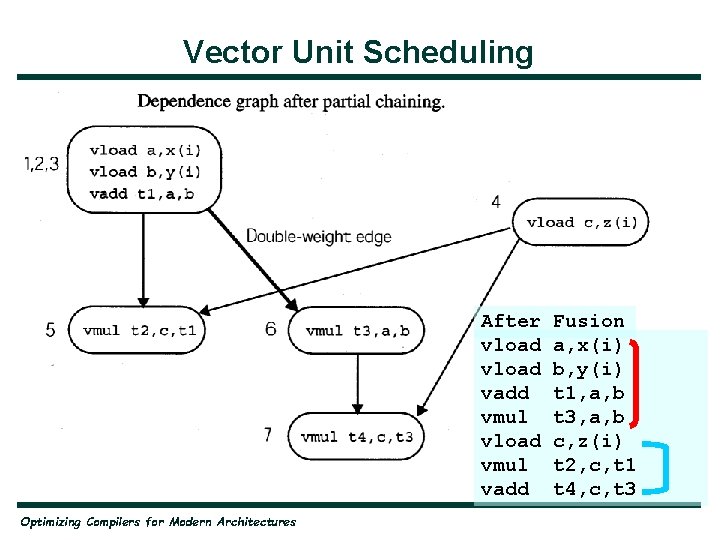

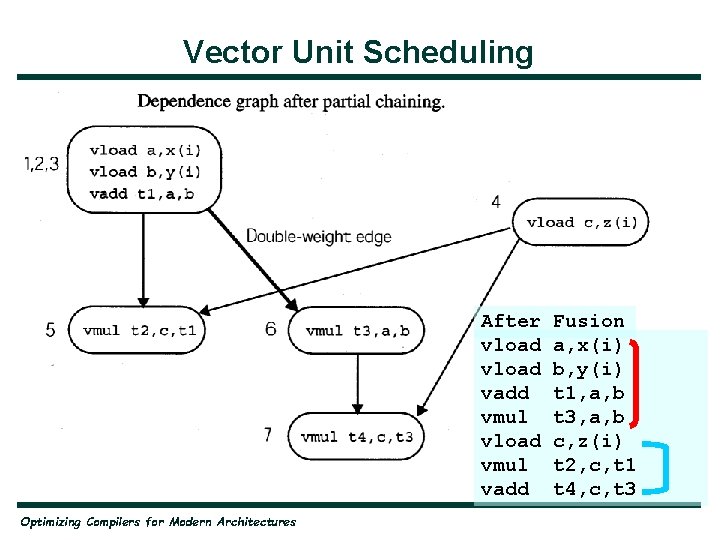

Vector Unit Scheduling vload a, x(i) vload b, y(i) vadd t 1, a, b vload c, z(i) vmul t 2, c, t 1 vmult 3, a, b vaddt 4, c, t 3 • Rearranging: vload vadd vmul vload vmul vadd a, x(i) b, y(i) t 1, a, b t 3, a, b c, z(i) t 2, c, t 1 t 4, c, t 3 Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures 2 load, 1 addition, 1 multiplication pipe

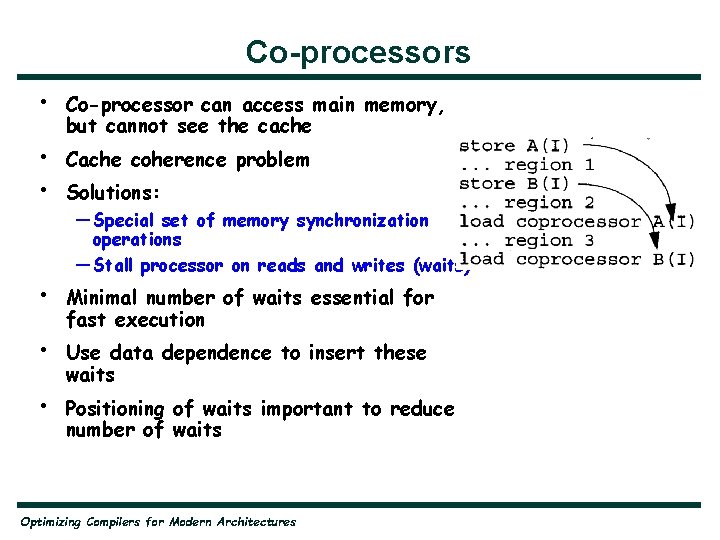

Vector Unit Scheduling • Chaining problem solved by weighted fusion algorithm: — Variant of fusion algorithm seen in Chapter 8 — Takes into consideration resource constraints of machine (number of pipes) — Weights are recomputed dynamically: For instance, if an addition and a subtraction is selected for chaining, then a load that is an input to both the addition and subtraction will be given a higher weight after fusion Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Vector Unit Scheduling a, x(i) b, y(i) t 1, a, b c, z(i) Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures vload vadd vload vmul t 2, c, t 1 vmul t 3, a, b vadd

Vector Unit Scheduling After vload vadd vmul vload vmul vadd Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures Fusion a, x(i) b, y(i) t 1, a, b t 3, a, b c, z(i) t 2, c, t 1 t 4, c, t 3

Co-processors • • • Co-processor can access main memory, but cannot see the cache Cache coherence problem Solutions: — Special set of memory synchronization operations — Stall processor on reads and writes (waits) Minimal number of waits essential for fast execution Use data dependence to insert these waits Positioning of waits important to reduce number of waits Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Co-processors • Algorithm to insert waits: • Produces minimum number of waits in absence of control flow • Minimizing waits in presence of control flow is NP Complete. Compiler must use heuristics — Make a single pass starting from the beginning of the block — Note source of edges — When target reached, insert wait Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures

Conclusion • We looked at: — Straight line scheduling: For basic blocks — Trace Scheduling: Across basic blocks — Kernel Scheduling: Exploit parallelism across loop iterations — Vector Unit Scheduling — Issues in cache coherence for coprocessors Optimizing Compilers for Modern Architectures