Scheduling Buffer Management Lecture 4 1 The setting

Scheduling: Buffer Management Lecture 4 1

The setting Lecture 4 2

Buffer Scheduling q Who to send next? q What happens when buffer is full? q Who to discard? Lecture 4 3

Requirements of scheduling q An ideal scheduling discipline m is easy to implement m is fair and protective m provides performance bounds q Each scheduling discipline makes a different trade-off among these requirements Lecture 4 4

Ease of implementation q Scheduling discipline has to make a decision once every few microseconds! q Should be implementable in a few instructions or hardware m for hardware: critical constraint is VLSI space m Complexity of enqueue + dequeue processes q Work per packet should scale less than linearly with number of active connections Lecture 4 5

Fairness q Intuitively m each connection should get no more than its demand m the excess, if any, is equally shared q But it also provides protection m traffic hogs cannot overrun others m automatically isolates heavy users Lecture 4 6

Max-min Fairness: Single Buffer m Allocate bandwidth equally among all users m If anyone doesn’t need its share, redistribute m maximize the minimum bandwidth provided to any flow not receiving its request m Ex: Compute the max-min fair allocation for a set of four sources with demands 2, 2. 6, 4, 5 when the resource has a capacity of 10. • s 1= 2; • s 2= 2. 6; • s 3 = s 4= 2. 7 m More complicated in a network. Lecture 4 7

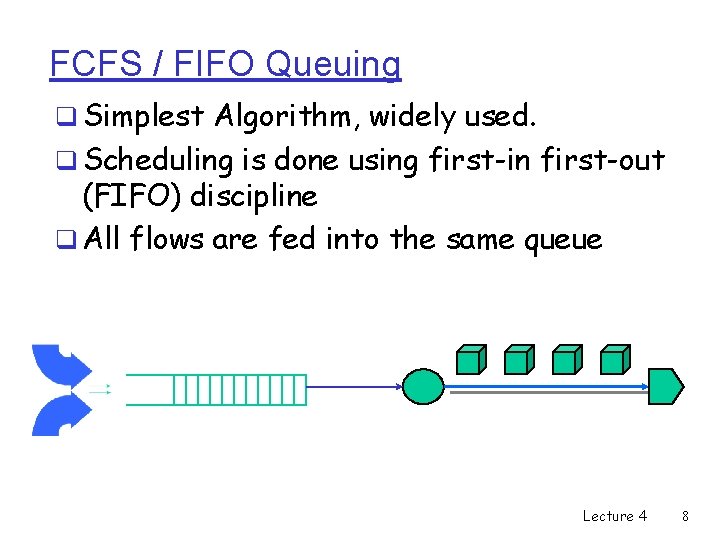

FCFS / FIFO Queuing q Simplest Algorithm, widely used. q Scheduling is done using first-in first-out (FIFO) discipline q All flows are fed into the same queue Lecture 4 8

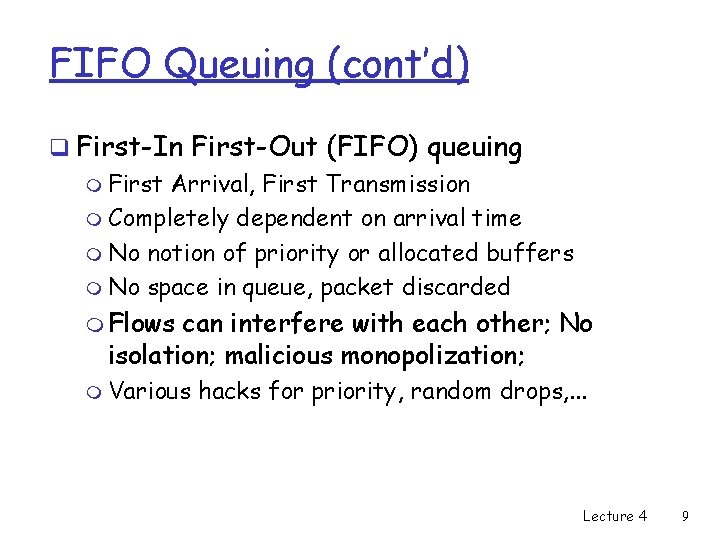

FIFO Queuing (cont’d) q First-In First-Out (FIFO) queuing m First Arrival, First Transmission m Completely dependent on arrival time m No notion of priority or allocated buffers m No space in queue, packet discarded m Flows can interfere with each other; No isolation; malicious monopolization; m Various hacks for priority, random drops, . . . Lecture 4 9

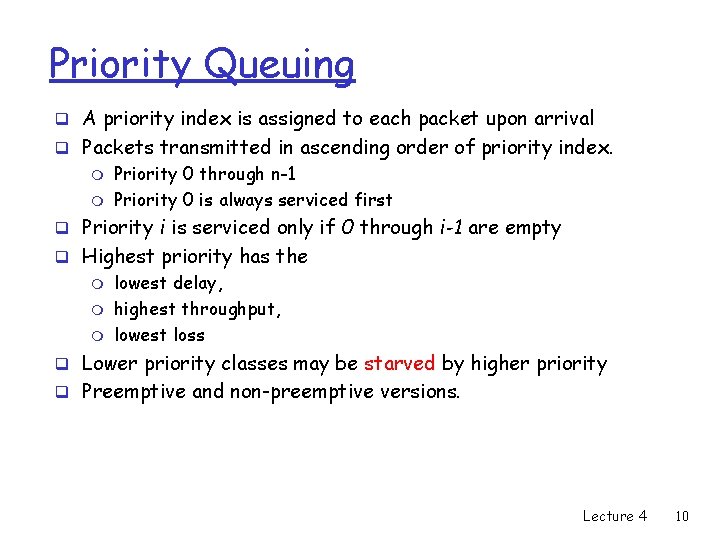

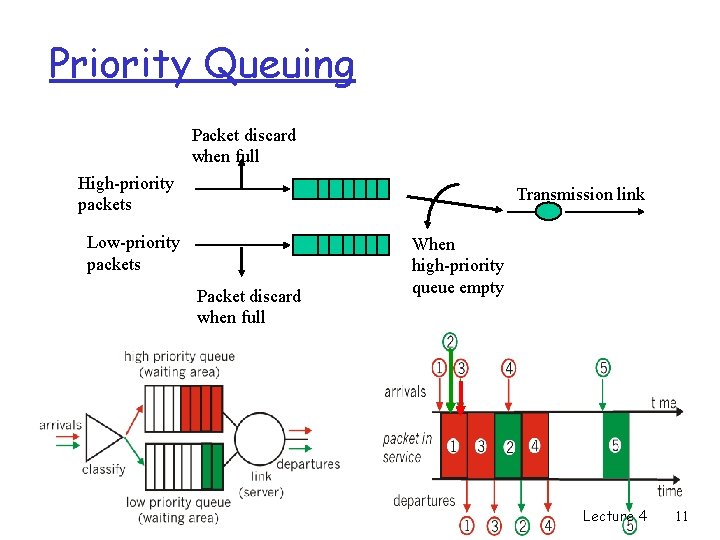

Priority Queuing q A priority index is assigned to each packet upon arrival q Packets transmitted in ascending order of priority index. m m Priority 0 through n-1 Priority 0 is always serviced first q Priority i is serviced only if 0 through i-1 are empty q Highest priority has the m m m lowest delay, highest throughput, lowest loss q Lower priority classes may be starved by higher priority q Preemptive and non-preemptive versions. Lecture 4 10

Priority Queuing Packet discard when full High-priority packets Transmission link Low-priority packets Packet discard when full When high-priority queue empty Lecture 4 11

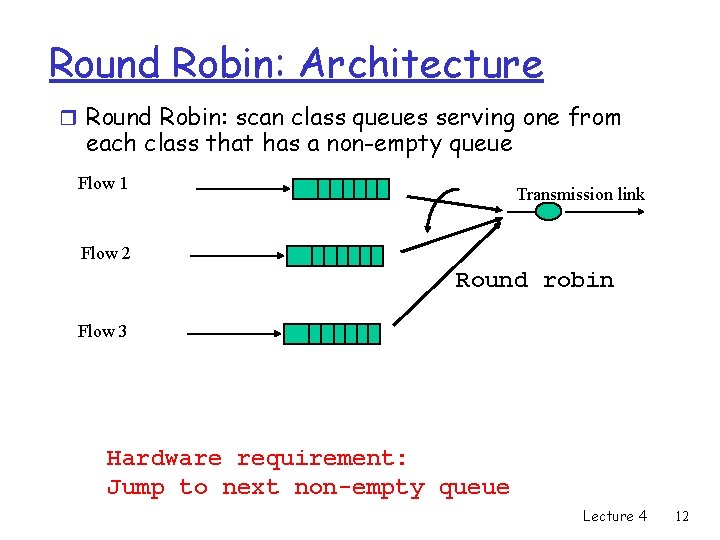

Round Robin: Architecture r Round Robin: scan class queues serving one from each class that has a non-empty queue Flow 1 Transmission link Flow 2 Round robin Flow 3 Hardware requirement: Jump to next non-empty queue Lecture 4 12

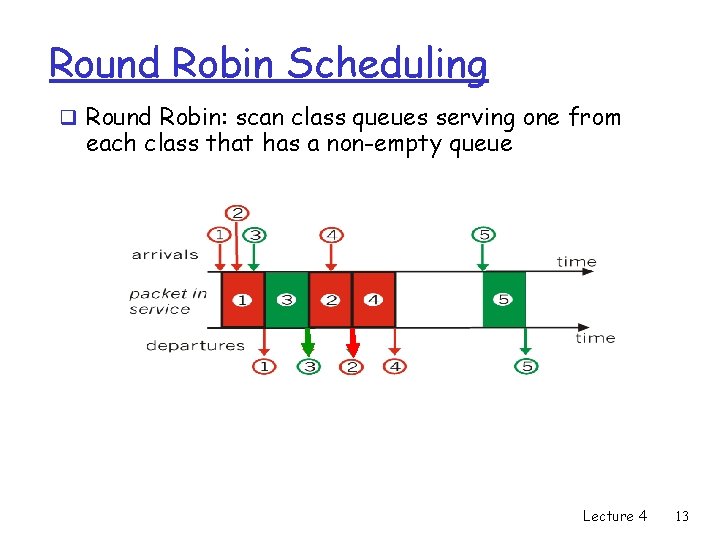

Round Robin Scheduling q Round Robin: scan class queues serving one from each class that has a non-empty queue Lecture 4 13

Round Robin (cont’d) q Characteristics: m Classify incoming traffic into flows (sourcedestination pairs) m Round-robin among flows q Problems: m Ignores packet length (GPS, Fair queuing) m Inflexible allocation of weights (WRR, WFQ) q Benefits: m protection against heavy users (why? ) Lecture 4 14

Weighted Round-Robin q Weighted round-robin m Different weight wi (per flow) m Flow j can sends wj packets in a period. m Period of length wj q Disadvantage m Variable packet size. m Fair only over time scales longer than a period time. • If a connection has a small weight, or the number of connections is large, this may lead to long periods of unfairness. Lecture 4 15

DRR algorithm q Choose a quantum of bits to serve from each connection in order. q For each HOL (Head of Line) packet, m m m if its size is <= (quantum + credit) send and save excess, otherwise save entire quantum. If no packet to send, reset counter (to remain fair) q Each connection has a deficit counter (to store credits) with initial value zero. q Easier implementation than other fair policies m WFQ Lecture 4 16

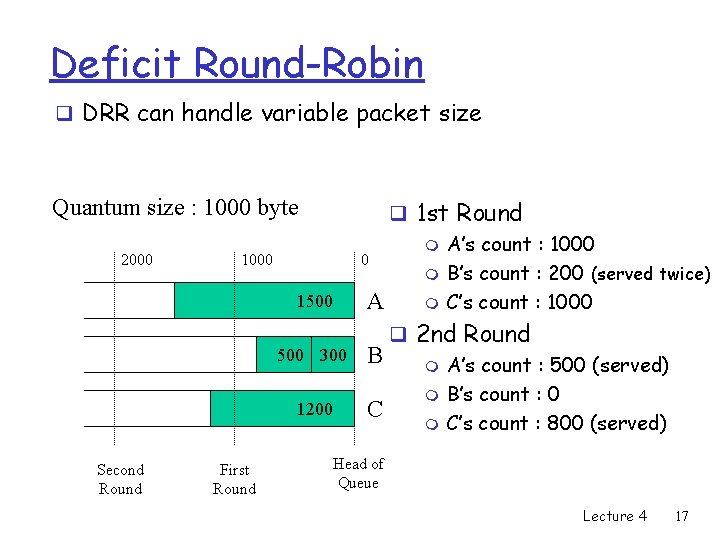

Deficit Round-Robin q DRR can handle variable packet size Quantum size : 1000 byte 2000 1500 q 1 st Round m A’s count : 1000 0 m B’s count : 200 (served twice) A m C’s count : 1000 q 2 nd Round 500 300 B m A’s count : 500 (served) m B’s count : 0 1200 C m C’s count : 800 (served) Second Round First Round Head of Queue Lecture 4 17

DRR: performance q Handles variable length packets q Backlogged source share bandwidth equally q Preferably, packet size < Quantum q Simple to implement m Similar to round robin Lecture 4 18

Generalized Processor Sharing Lecture 4 19

Generalized Process Sharing (GPS) q The methodology: m Assume we can send infinitesimal packets • single bit m Perform round robin. • At the bit level q Idealized policy to split bandwidth q GPS is not implementable q Used mainly to evaluate and compare real approaches. q Has weights that give relative frequencies. Lecture 4 20

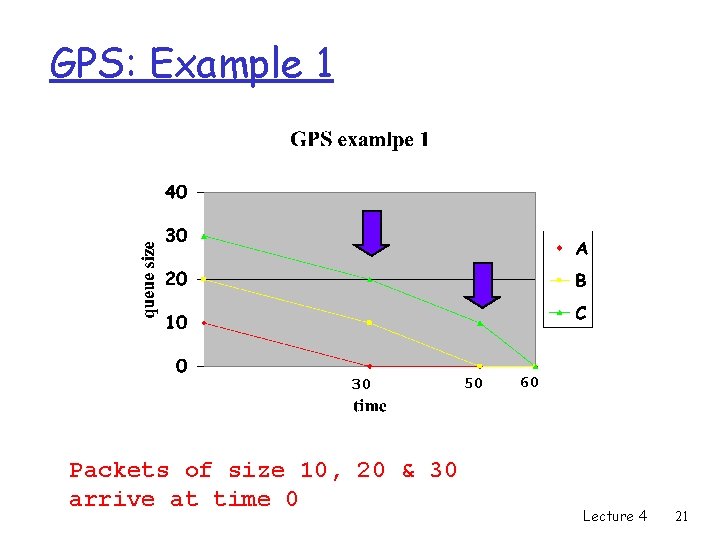

GPS: Example 1 30 Packets of size 10, 20 & 30 arrive at time 0 50 60 Lecture 4 21

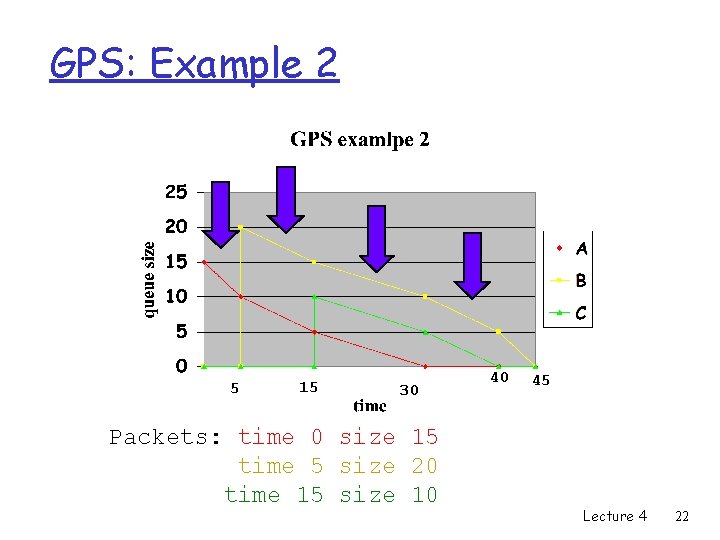

GPS: Example 2 5 15 30 Packets: time 0 size 15 time 5 size 20 time 15 size 10 40 45 Lecture 4 22

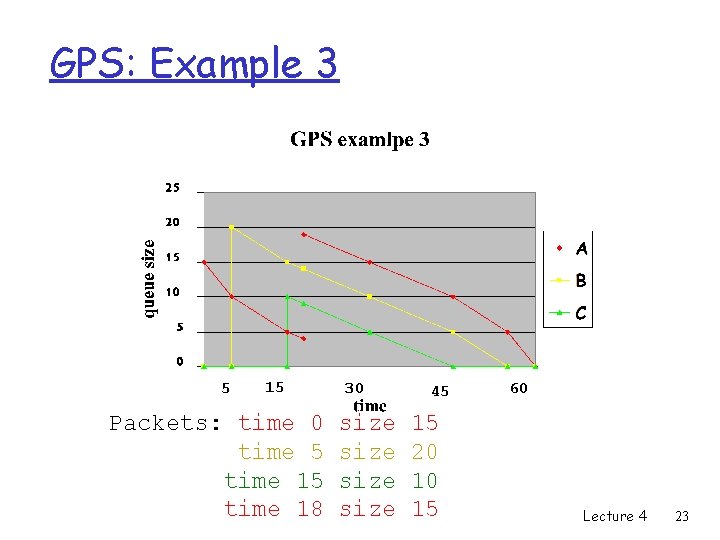

GPS: Example 3 5 15 Packets: time 0 time 5 time 18 30 size 45 15 20 10 15 60 Lecture 4 23

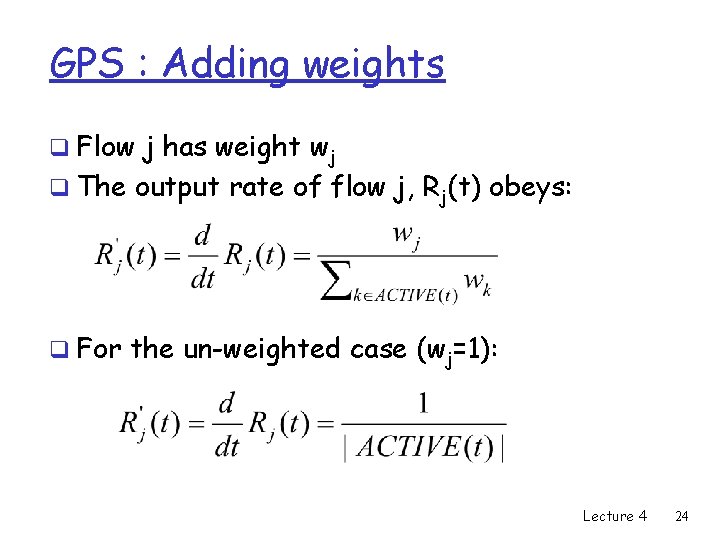

GPS : Adding weights q Flow j has weight wj q The output rate of flow j, Rj(t) obeys: q For the un-weighted case (wj=1): Lecture 4 24

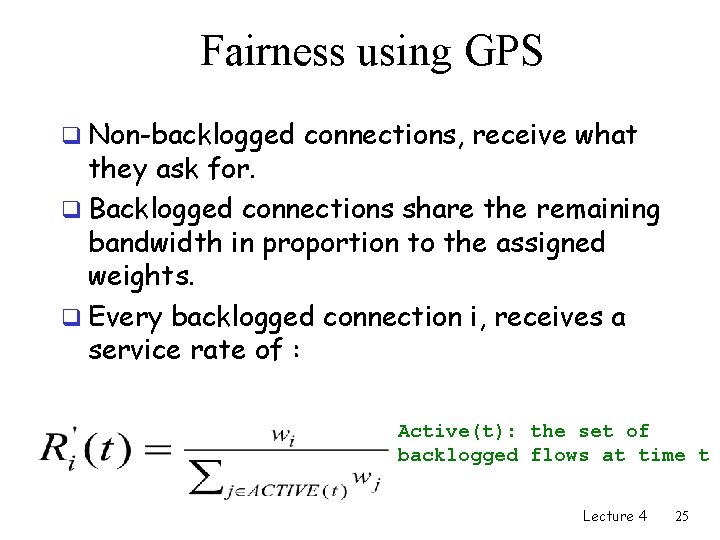

Fairness using GPS q Non-backlogged connections, receive what they ask for. q Backlogged connections share the remaining bandwidth in proportion to the assigned weights. q Every backlogged connection i, receives a service rate of : Active(t): the set of backlogged flows at time t Lecture 4 25

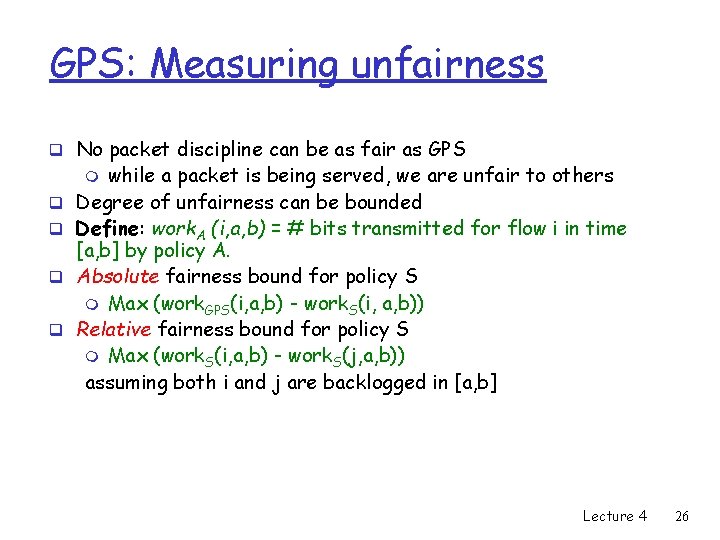

GPS: Measuring unfairness q No packet discipline can be as fair as GPS while a packet is being served, we are unfair to others Degree of unfairness can be bounded Define: work. A (i, a, b) = # bits transmitted for flow i in time [a, b] by policy A. Absolute fairness bound for policy S m Max (work. GPS(i, a, b) - work. S(i, a, b)) Relative fairness bound for policy S m Max (work. S(i, a, b) - work. S(j, a, b)) assuming both i and j are backlogged in [a, b] m q q Lecture 4 26

GPS: Measuring unfairness q Assume fixed packet size and round robin q Relative bound: 1 q Absolute bound: < 1 q Challenge: handle variable size packets. Lecture 4 27

Weighted Fair Queueing Lecture 4 28

GPS to WFQ q We can’t implement GPS q So, lets see how to emulate it q We want to be as fair as possible q But also have an efficient implementation Lecture 4 29

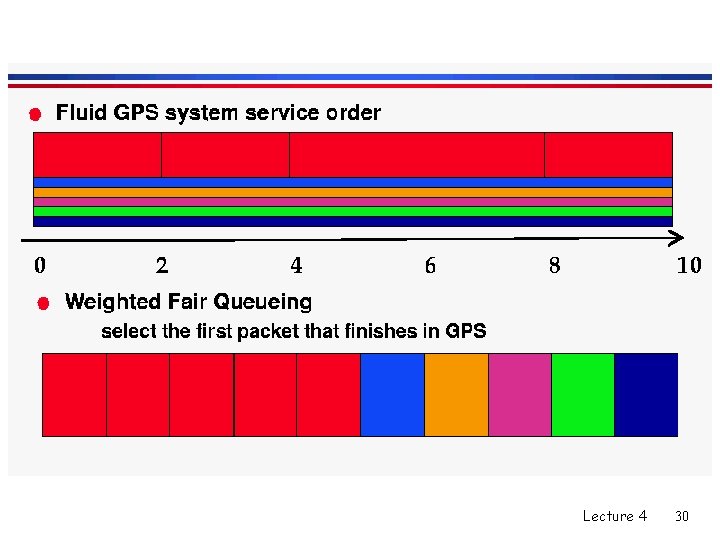

Lecture 4 30

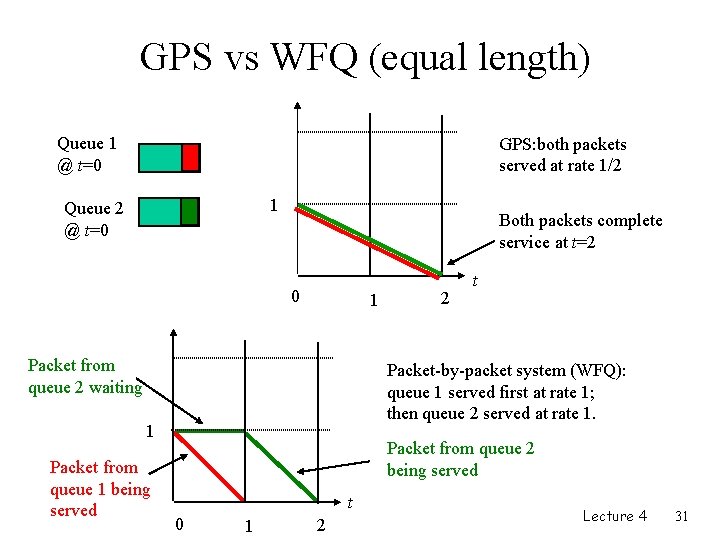

GPS vs WFQ (equal length) Queue 1 @ t=0 GPS: both packets served at rate 1/2 1 Queue 2 @ t=0 Both packets complete service at t=2 0 1 Packet from queue 2 waiting Packet-by-packet system (WFQ): queue 1 served first at rate 1; then queue 2 served at rate 1. 1 Packet from queue 1 being served 2 t Packet from queue 2 being served t 0 1 2 Lecture 4 31

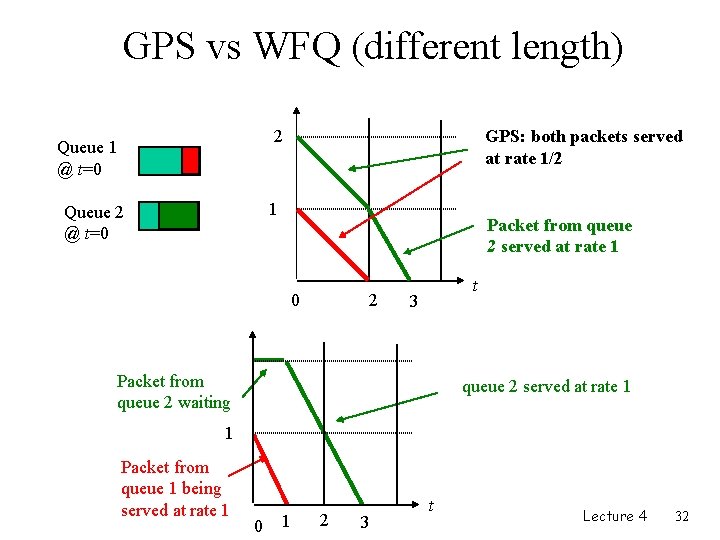

GPS vs WFQ (different length) 2 Queue 1 @ t=0 GPS: both packets served at rate 1/2 1 Queue 2 @ t=0 Packet from queue 2 served at rate 1 0 2 t 3 Packet from queue 2 waiting queue 2 served at rate 1 1 Packet from queue 1 being served at rate 1 0 1 2 3 t Lecture 4 32

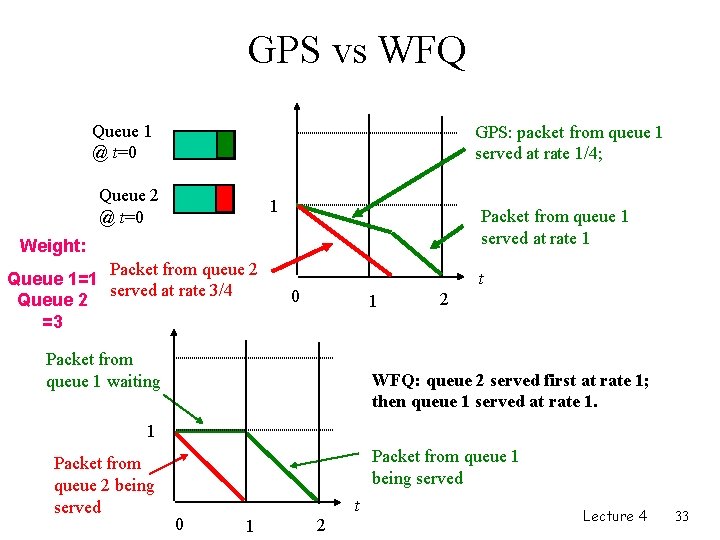

GPS vs WFQ Queue 1 @ t=0 GPS: packet from queue 1 served at rate 1/4; Queue 2 @ t=0 1 Packet from queue 1 served at rate 1 Weight: Packet from queue 2 Queue 1=1 served at rate 3/4 Queue 2 =3 t 0 1 Packet from queue 1 waiting 2 WFQ: queue 2 served first at rate 1; then queue 1 served at rate 1. 1 Packet from queue 2 being served Packet from queue 1 being served 0 1 2 t Lecture 4 33

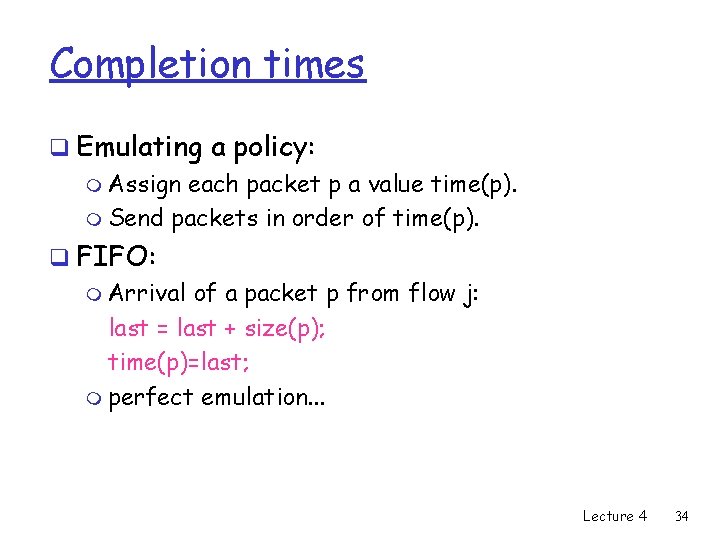

Completion times q Emulating a policy: m Assign each packet p a value time(p). m Send packets in order of time(p). q FIFO: m Arrival of a packet p from flow j: last = last + size(p); time(p)=last; m perfect emulation. . . Lecture 4 34

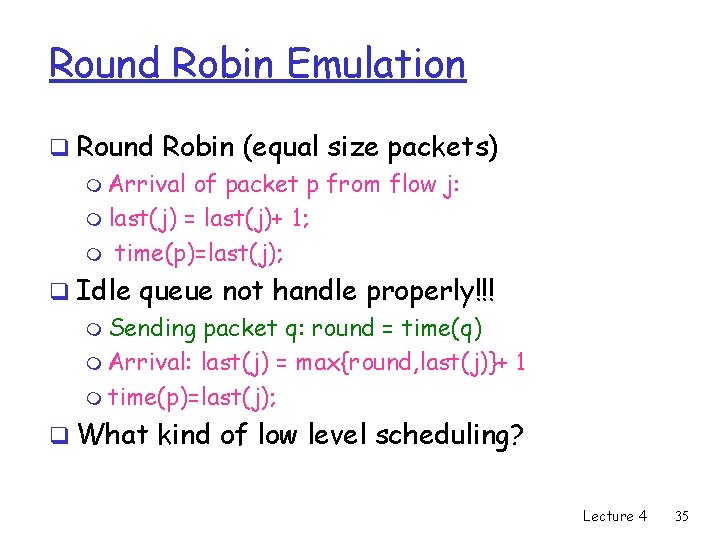

Round Robin Emulation q Round Robin (equal size packets) m Arrival of packet p from flow j: m last(j) = last(j)+ 1; m time(p)=last(j); q Idle queue not handle properly!!! m Sending packet q: round = time(q) m Arrival: last(j) = max{round, last(j)}+ 1 m time(p)=last(j); q What kind of low level scheduling? Lecture 4 35

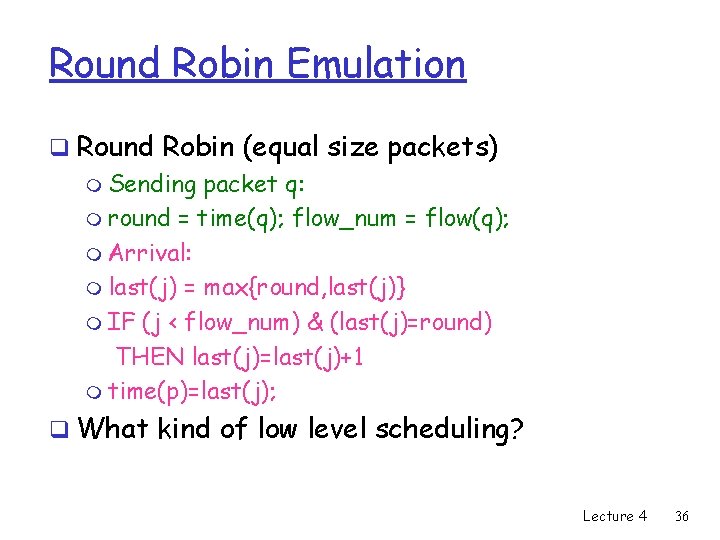

Round Robin Emulation q Round Robin (equal size packets) m Sending packet q: m round = time(q); flow_num = flow(q); m Arrival: m last(j) = max{round, last(j)} m IF (j < flow_num) & (last(j)=round) THEN last(j)=last(j)+1 m time(p)=last(j); q What kind of low level scheduling? Lecture 4 36

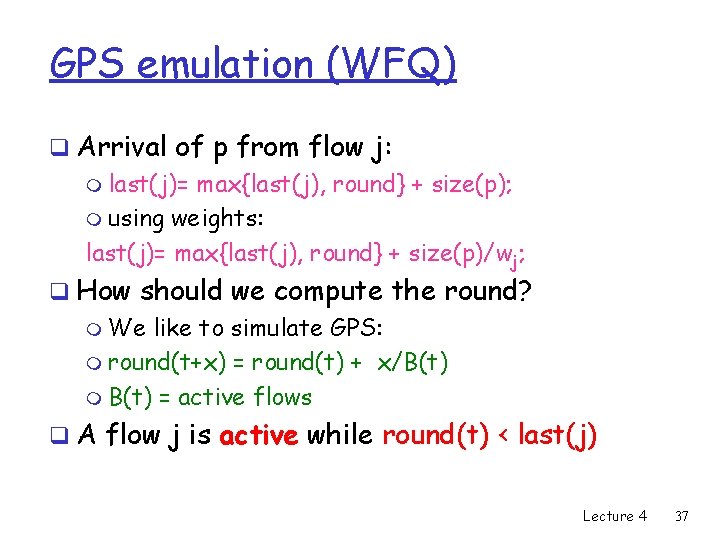

GPS emulation (WFQ) q Arrival of p from flow j: m last(j)= max{last(j), round} + size(p); m using weights: last(j)= max{last(j), round} + size(p)/wj; q How should we compute the round? m We like to simulate GPS: m round(t+x) = round(t) + x/B(t) m B(t) = active flows q A flow j is active while round(t) < last(j) Lecture 4 37

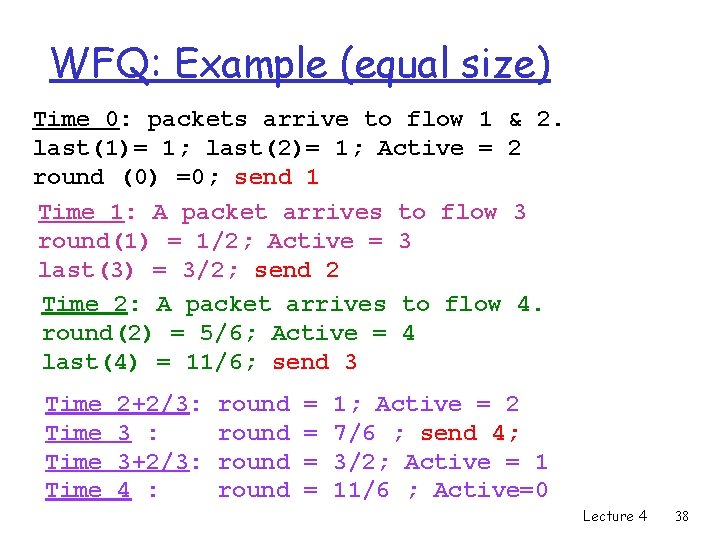

WFQ: Example (equal size) Time 0: packets arrive to flow 1 & 2. last(1)= 1; last(2)= 1; Active = 2 round (0) =0; send 1 Time 1: A packet arrives to flow 3 round(1) = 1/2; Active = 3 last(3) = 3/2; send 2 Time 2: A packet arrives to flow 4. round(2) = 5/6; Active = 4 last(4) = 11/6; send 3 Time 2+2/3: 3 : 3+2/3: 4 : round = = 1; Active = 2 7/6 ; send 4; 3/2; Active = 1 11/6 ; Active=0 Lecture 4 38

Worst Case Fair Weighted Fair 2 Queuing (WF Q) Lecture 4 39

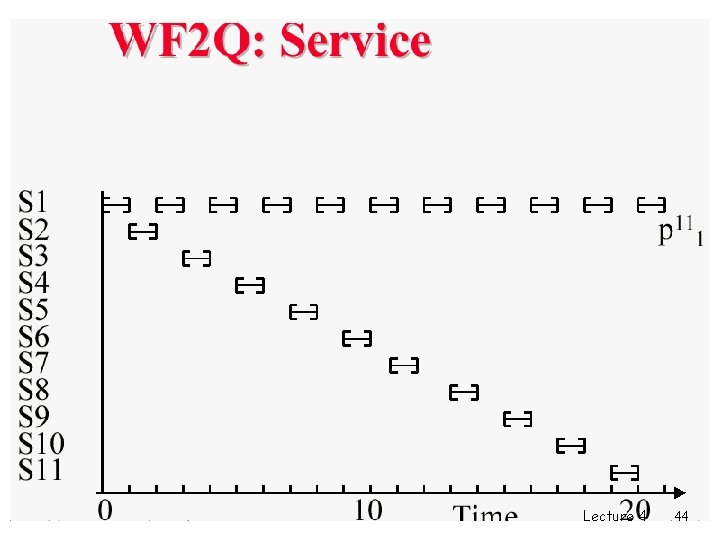

Worst Case Fair Weighted Fair Queuing (WF 2 Q) q WF 2 Q fixes an unfairness problem in WFQ. m WFQ: among packets waiting in the system, pick one that will finish service first under GPS m WF 2 Q: among packets waiting in the system, that have started service under GPS, select one that will finish service first GPS q WF 2 Q provides service closer to GPS m difference in packet service time bounded by max. packet size. Lecture 4 40

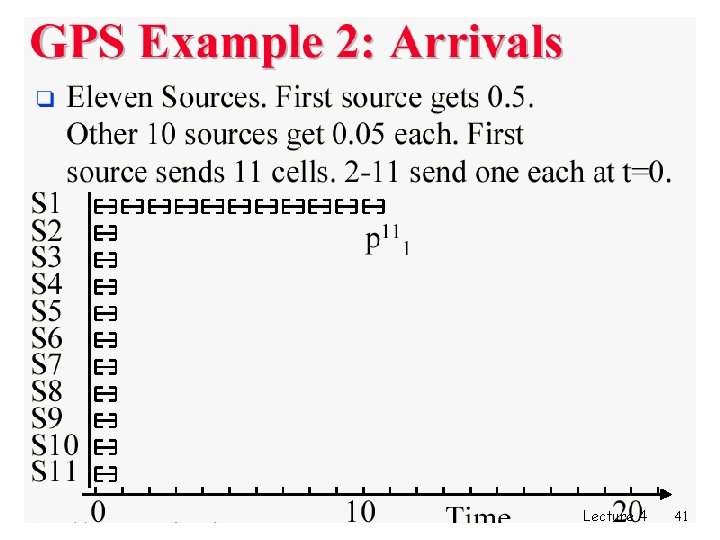

Lecture 4 41

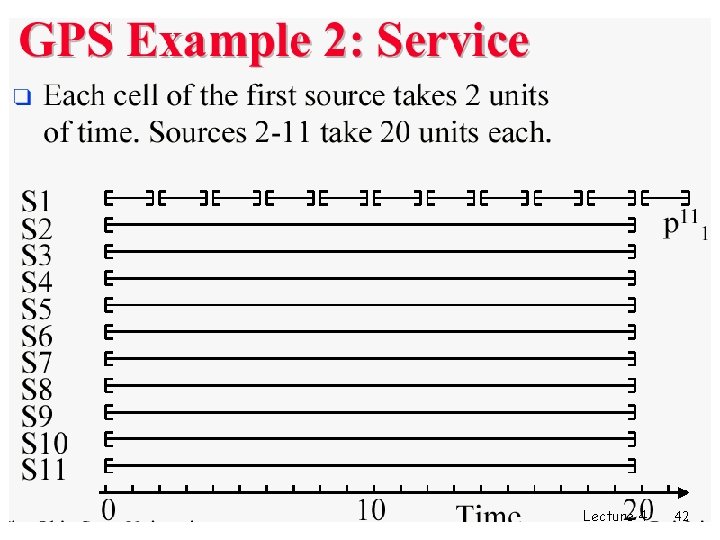

Lecture 4 42

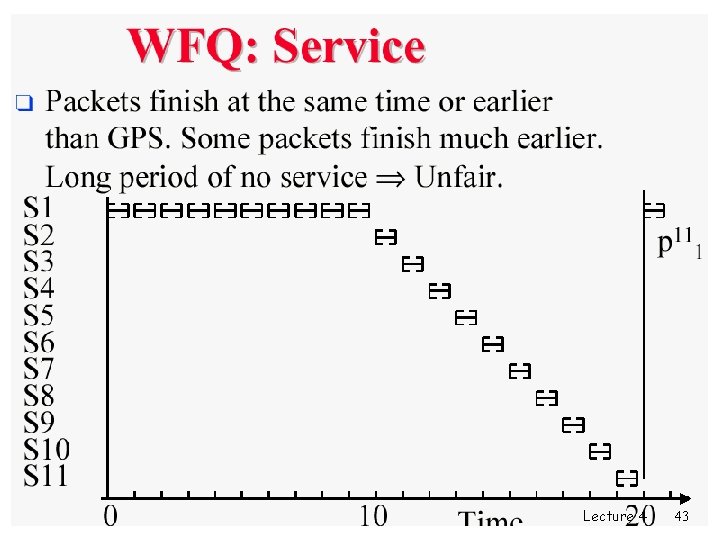

Lecture 4 43

Lecture 4 44

Multiple Buffers Lecture 4 45

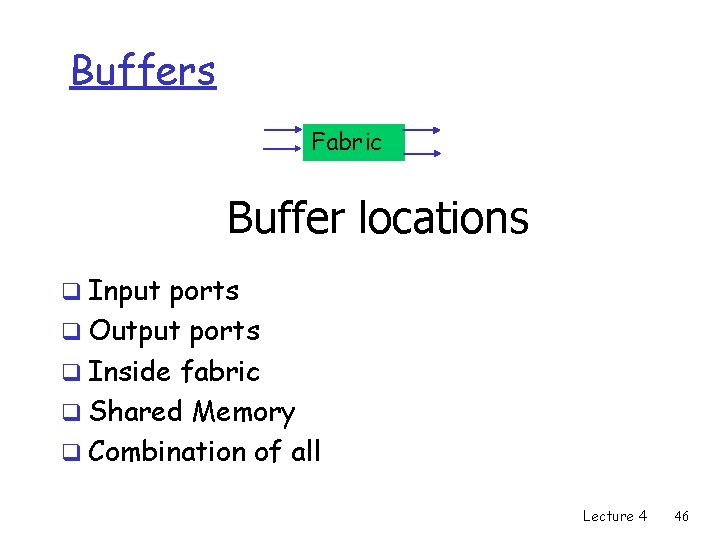

Buffers Fabric Buffer locations q Input ports q Output ports q Inside fabric q Shared Memory q Combination of all Lecture 4 46

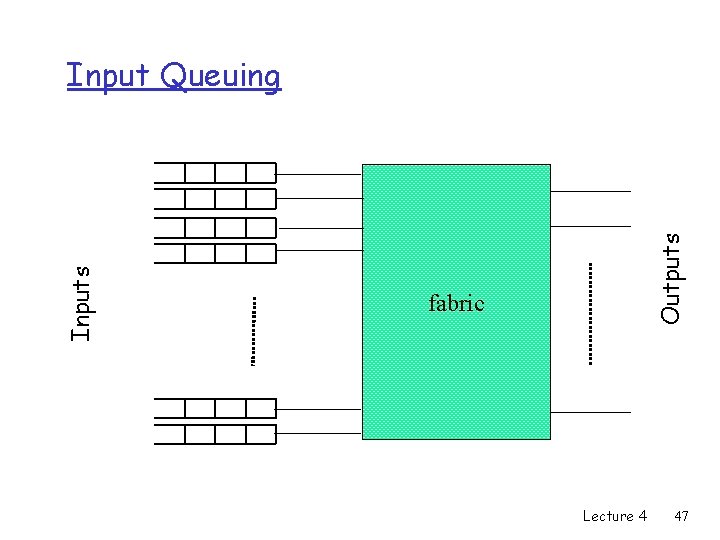

Outputs Input Queuing fabric Lecture 4 47

Input Buffer : properties • • • Input speed of queue – no more than input line Need arbiter (running N times faster than input) FIFO queue Head Of Line (HOL) blocking. Utilization: • Random destination • 1 - 1/e = 59% utilization • due to HOL blocking Lecture 4 48

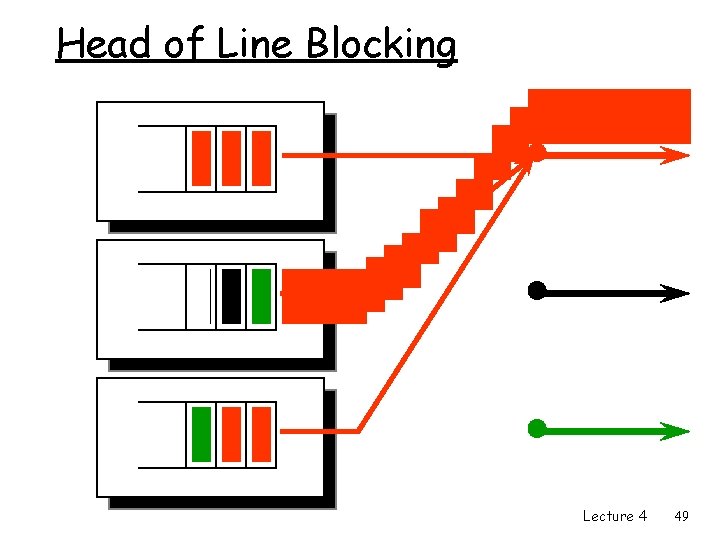

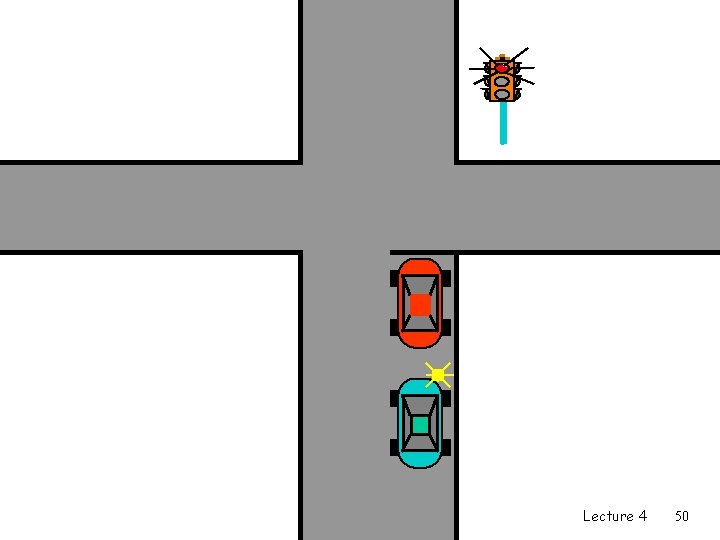

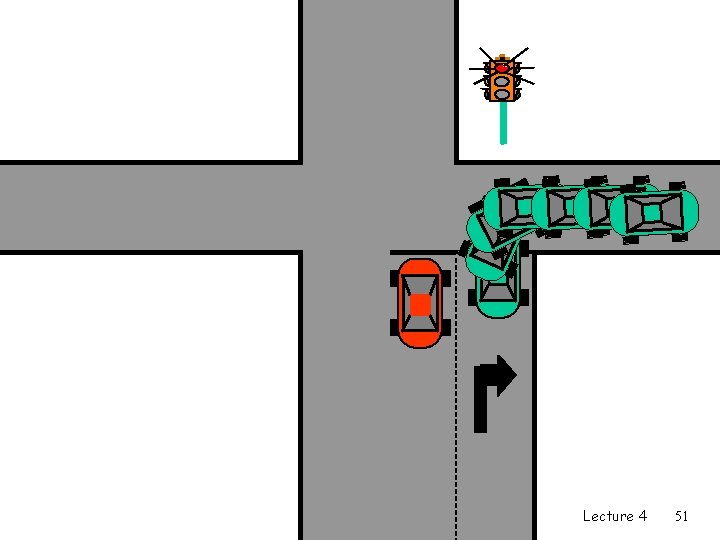

Head of Line Blocking Lecture 4 49

Lecture 4 50

Lecture 4 51

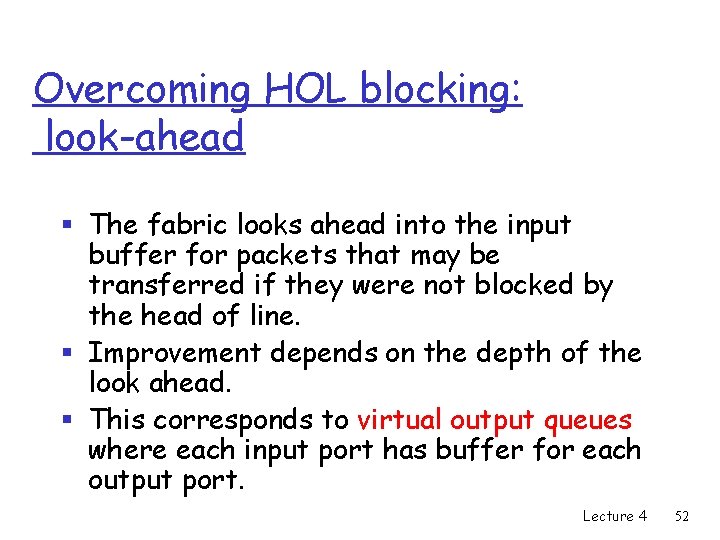

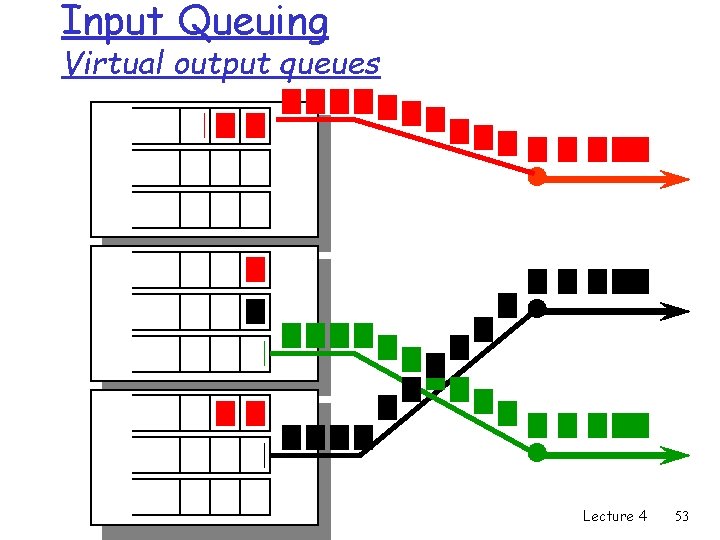

Overcoming HOL blocking: look-ahead § The fabric looks ahead into the input buffer for packets that may be transferred if they were not blocked by the head of line. § Improvement depends on the depth of the look ahead. § This corresponds to virtual output queues where each input port has buffer for each output port. Lecture 4 52

Input Queuing Virtual output queues Lecture 4 53

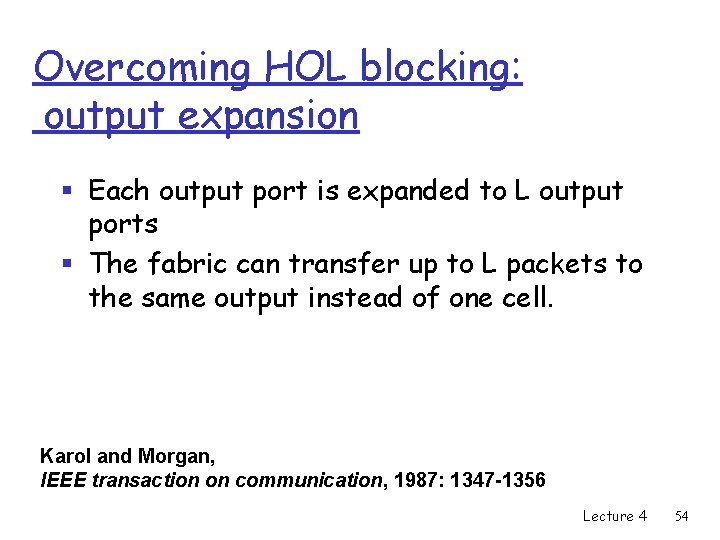

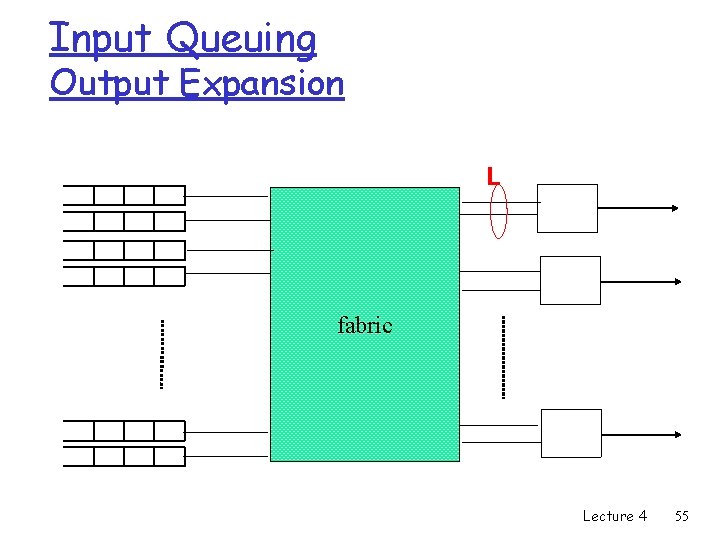

Overcoming HOL blocking: output expansion § Each output port is expanded to L output ports § The fabric can transfer up to L packets to the same output instead of one cell. Karol and Morgan, IEEE transaction on communication, 1987: 1347 -1356 Lecture 4 54

Input Queuing Output Expansion L fabric Lecture 4 55

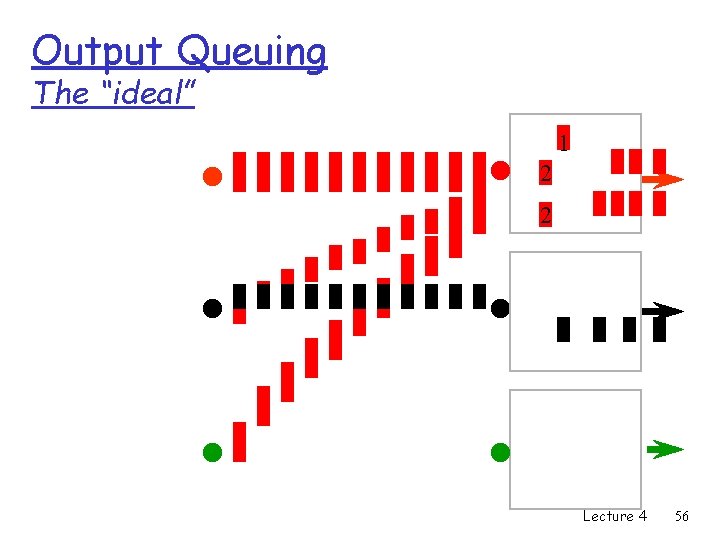

Output Queuing The “ideal” 2 1 1 2 1 2 11 2 2 1 Lecture 4 56

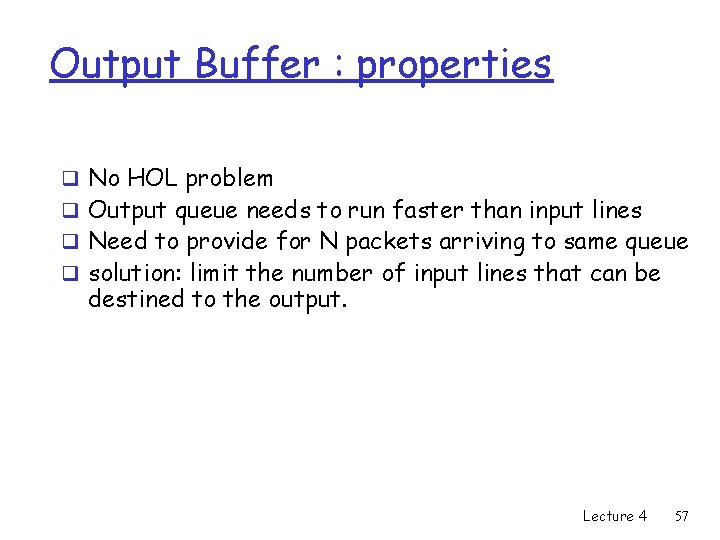

Output Buffer : properties q No HOL problem q Output queue needs to run faster than input lines q Need to provide for N packets arriving to same queue q solution: limit the number of input lines that can be destined to the output. Lecture 4 57

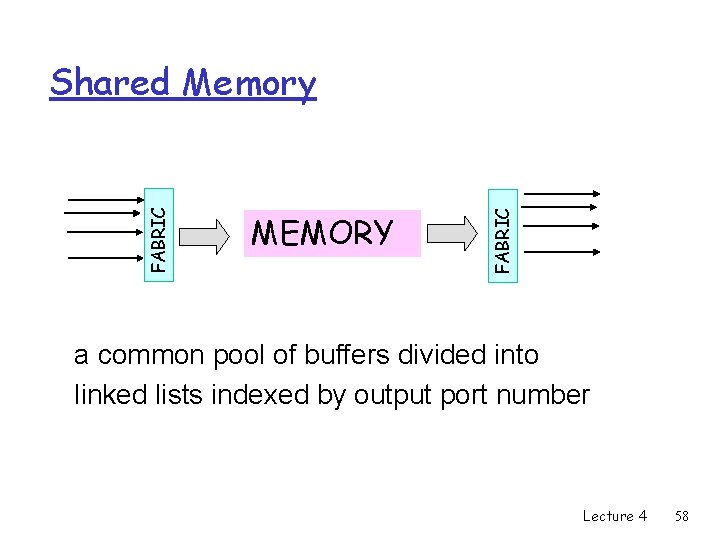

MEMORY FABRIC Shared Memory a common pool of buffers divided into linked lists indexed by output port number Lecture 4 58

Shared Memory: properties • • Packets stored in memory as they arrive Resource sharing Easy to implement priorities Memory is accessed at speed equal to sum of the input or output speeds • How to divide the space between the sessions Lecture 4 59

- Slides: 59