SATYR DRAMA SATYR DRAMA OR SATYR PLAY Tragedy

- Slides: 50

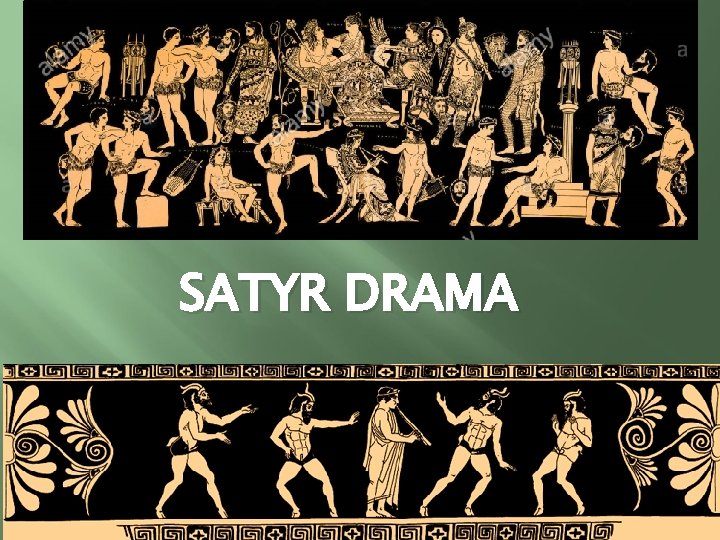

SATYR DRAMA

SATYR DRAMA OR SATYR PLAY Tragedy – Satyr Drama – Comedy: the three genres of Greek Drama • • Nothing to do with satire • Satyr Drama: because it always had a chorus of satyrs

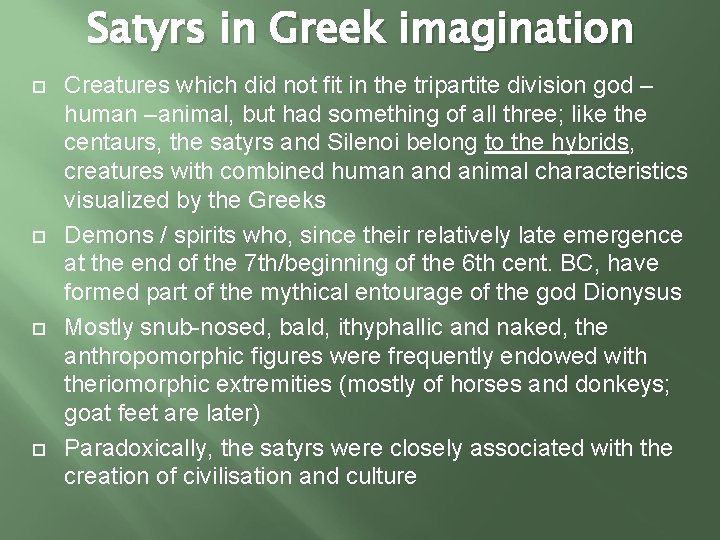

What were the satyrs?

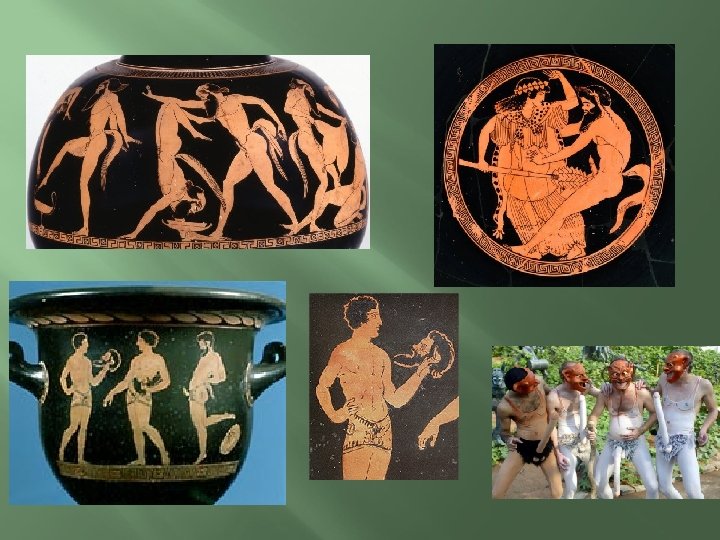

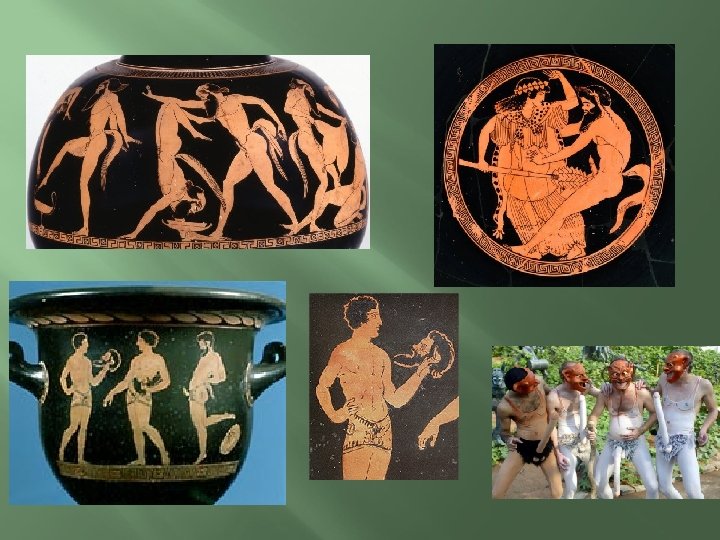

Satyrs in Greek imagination Creatures which did not fit in the tripartite division god – human –animal, but had something of all three; like the centaurs, the satyrs and Silenoi belong to the hybrids, creatures with combined human and animal characteristics visualized by the Greeks Demons / spirits who, since their relatively late emergence at the end of the 7 th/beginning of the 6 th cent. BC, have formed part of the mythical entourage of the god Dionysus Mostly snub-nosed, bald, ithyphallic and naked, the anthropomorphic figures were frequently endowed with theriomorphic extremities (mostly of horses and donkeys; goat feet are later) Paradoxically, the satyrs were closely associated with the creation of civilisation and culture

Satyr Drama at the Dramatic Festivals of Athens Composed by TRAGIC POETS as the LAST play of their TETRALOGIES With the same chorus, actors and musician the tragic poets produced one satyr drama, too. Thrived already at the time of Aeschylus Euripides’ Cyclops is the only surviving satyr play; Produced probably in 408, alongside Euripides’ Orestes and two more tragedies Also in significant fragments: Aeschylus’ Spectators at the Isthmian Games; Net-haulers; Sophocles’ Searchers (or Trackers)

SATYR DRAMA AND GREEK MYTHS Satyr dramas of the fifth century always dramatise traditional myths Like the plays of a tragic tetralogy, the satyr plays did not have to follow the same myth of the tetralogy But some did:

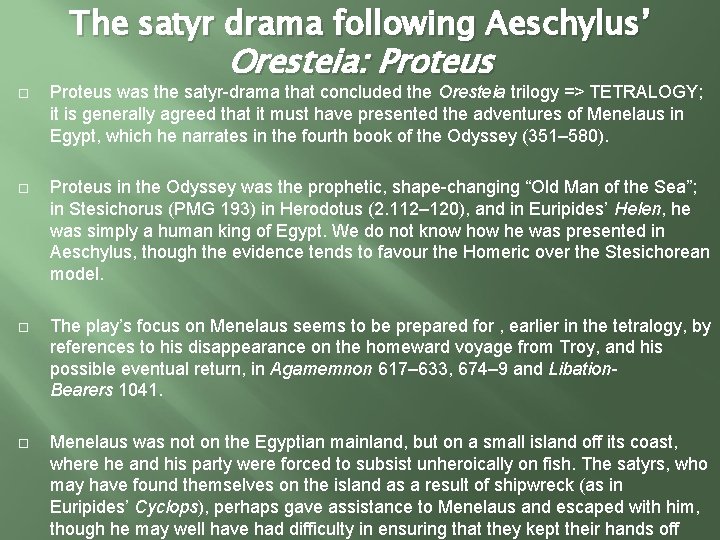

The satyr drama following Aeschylus’ Oresteia: Proteus was the satyr-drama that concluded the Oresteia trilogy => TETRALOGY; it is generally agreed that it must have presented the adventures of Menelaus in Egypt, which he narrates in the fourth book of the Odyssey (351– 580). Proteus in the Odyssey was the prophetic, shape-changing “Old Man of the Sea”; in Stesichorus (PMG 193) in Herodotus (2. 112– 120), and in Euripides’ Helen, he was simply a human king of Egypt. We do not know he was presented in Aeschylus, though the evidence tends to favour the Homeric over the Stesichorean model. The play’s focus on Menelaus seems to be prepared for , earlier in the tetralogy, by references to his disappearance on the homeward voyage from Troy, and his possible eventual return, in Agamemnon 617– 633, 674– 9 and Libation. Bearers 1041. Menelaus was not on the Egyptian mainland, but on a small island off its coast, where he and his party were forced to subsist unheroically on fish. The satyrs, who may have found themselves on the island as a result of shipwreck (as in Euripides’ Cyclops), perhaps gave assistance to Menelaus and escaped with him, though he may well have had difficulty in ensuring that they kept their hands off

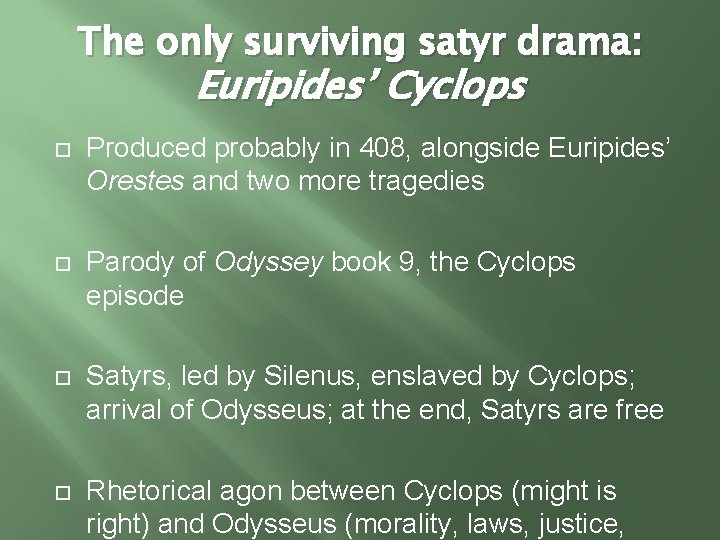

The only surviving satyr drama: Euripides’ Cyclops Produced probably in 408, alongside Euripides’ Orestes and two more tragedies Parody of Odyssey book 9, the Cyclops episode Satyrs, led by Silenus, enslaved by Cyclops; arrival of Odysseus; at the end, Satyrs are free Rhetorical agon between Cyclops (might is right) and Odysseus (morality, laws, justice,

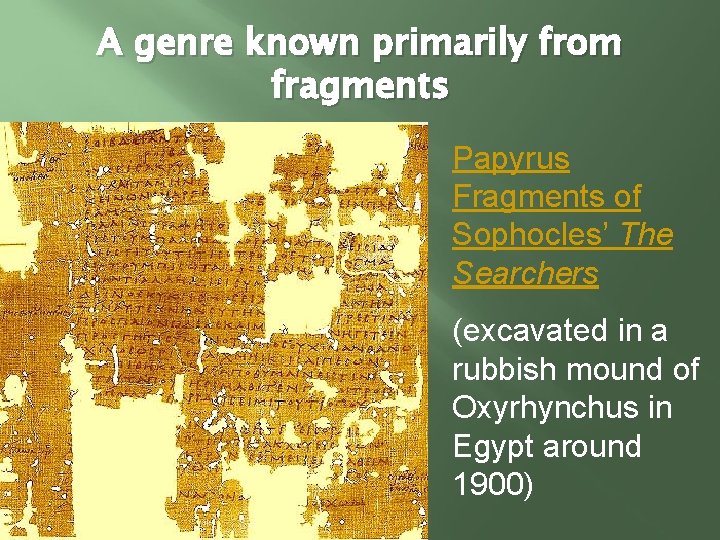

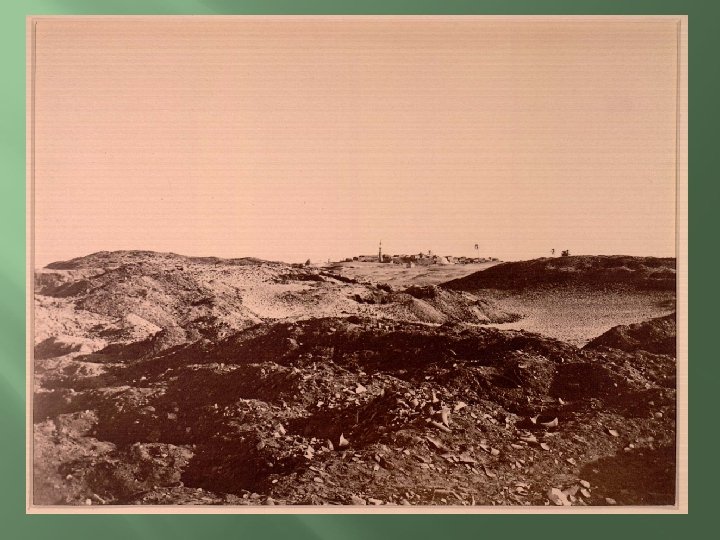

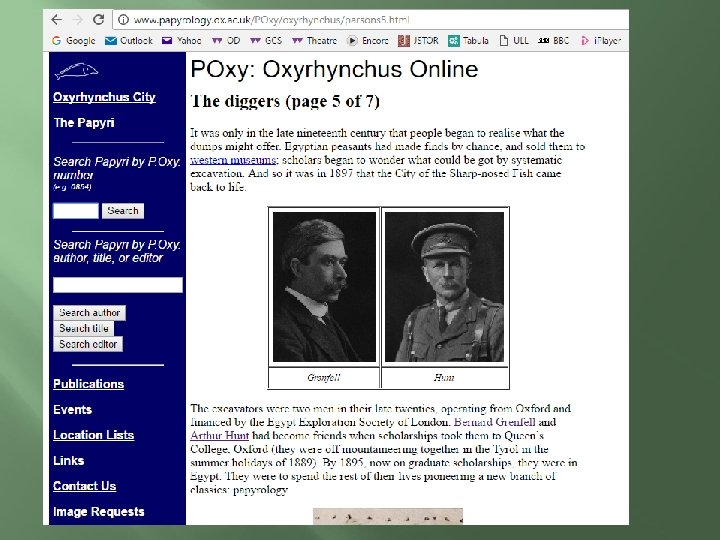

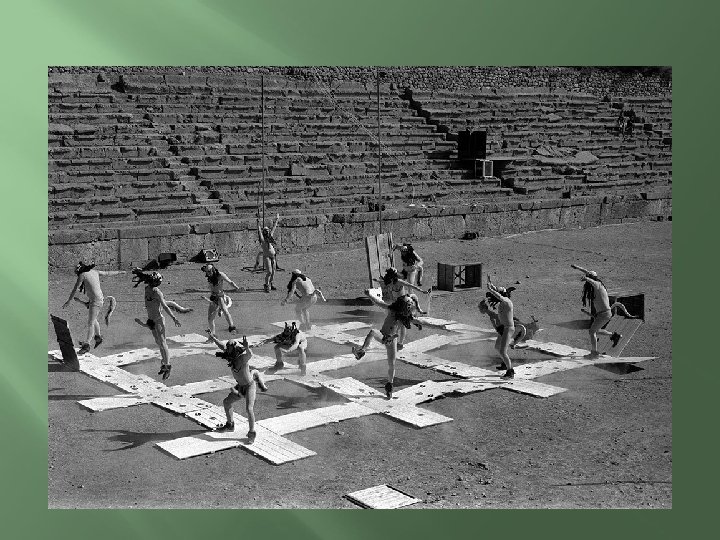

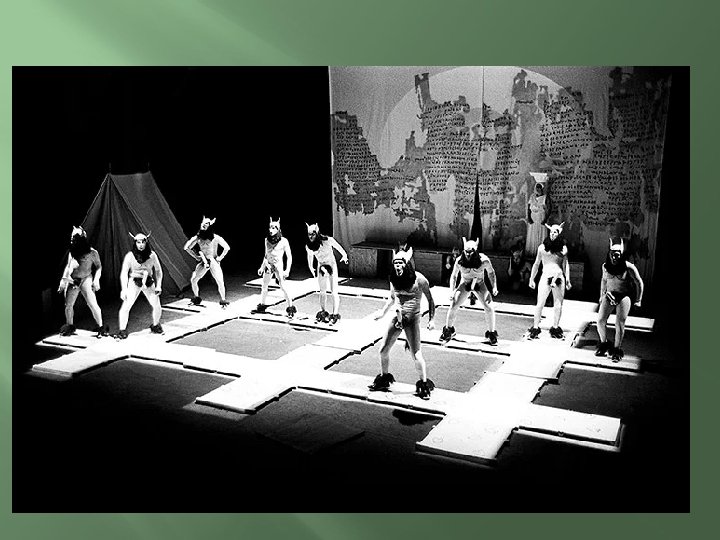

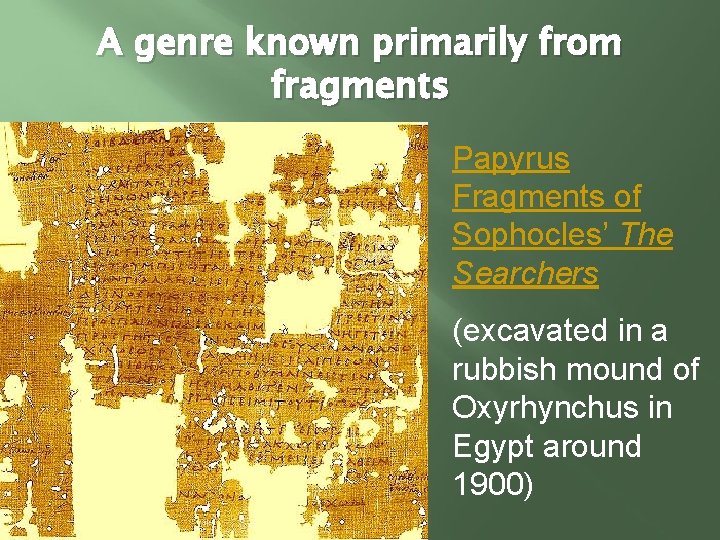

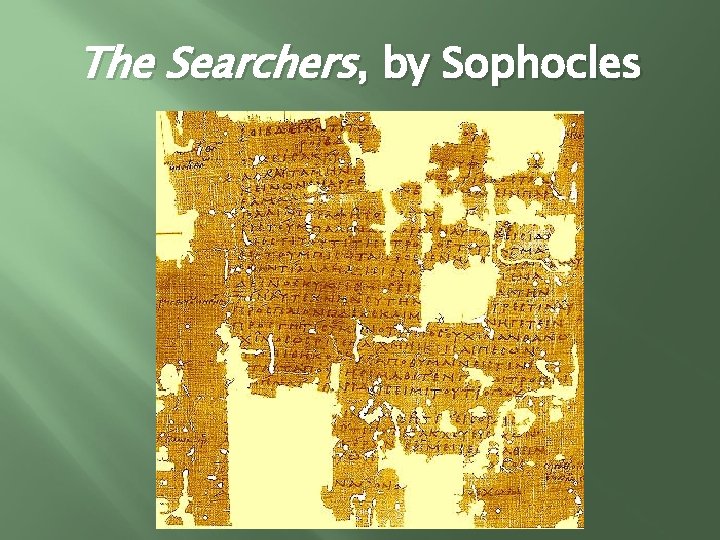

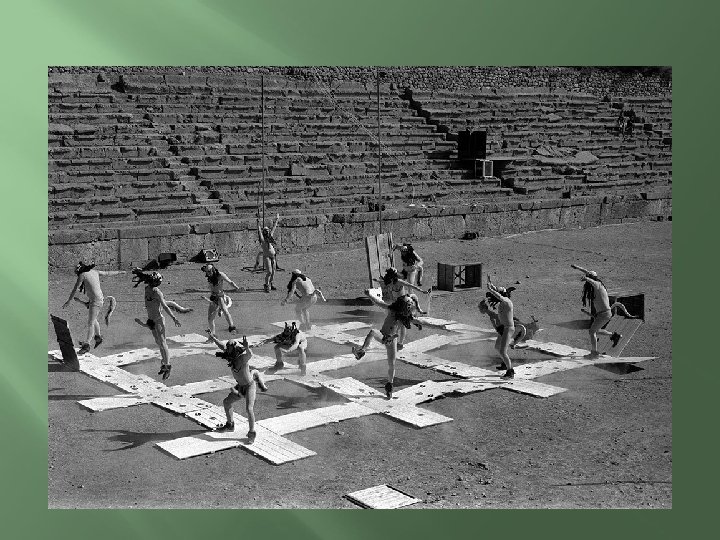

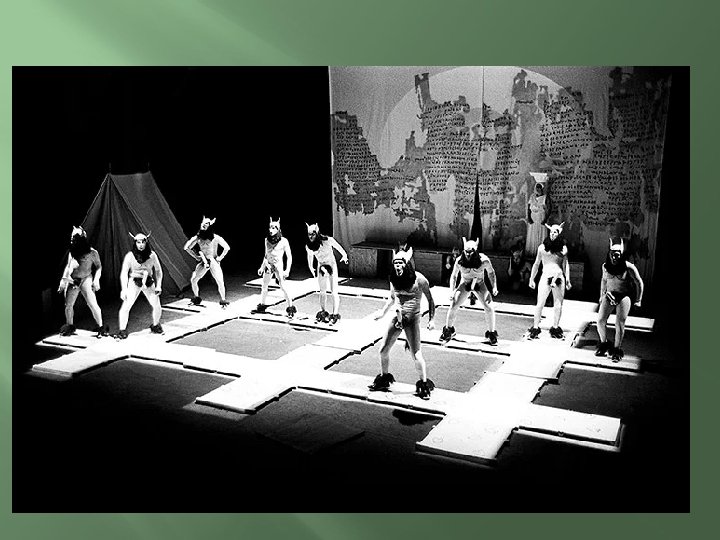

A genre known primarily from fragments Papyrus Fragments of Sophocles’ The Searchers (excavated in a rubbish mound of Oxyrhynchus in Egypt around 1900)

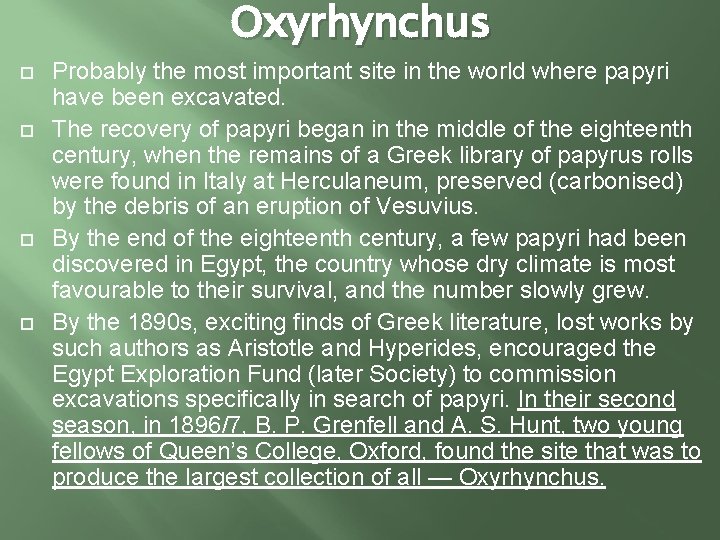

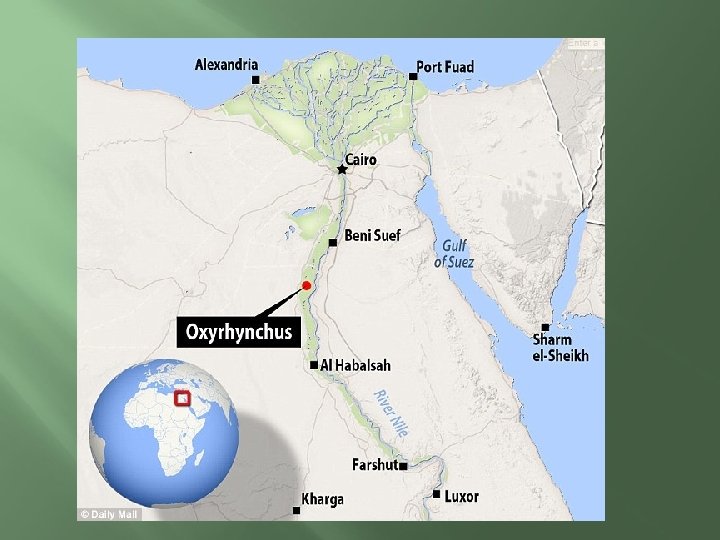

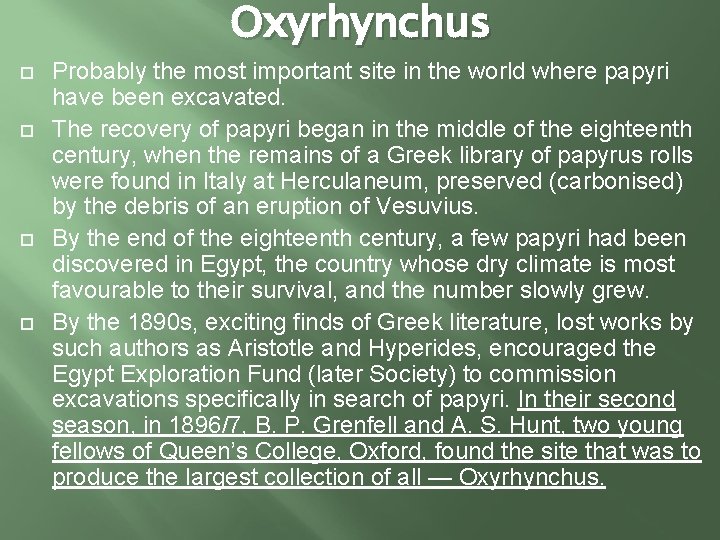

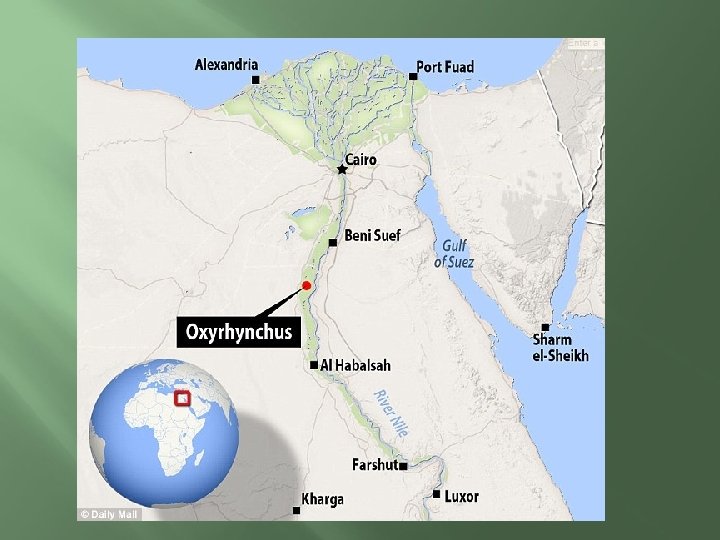

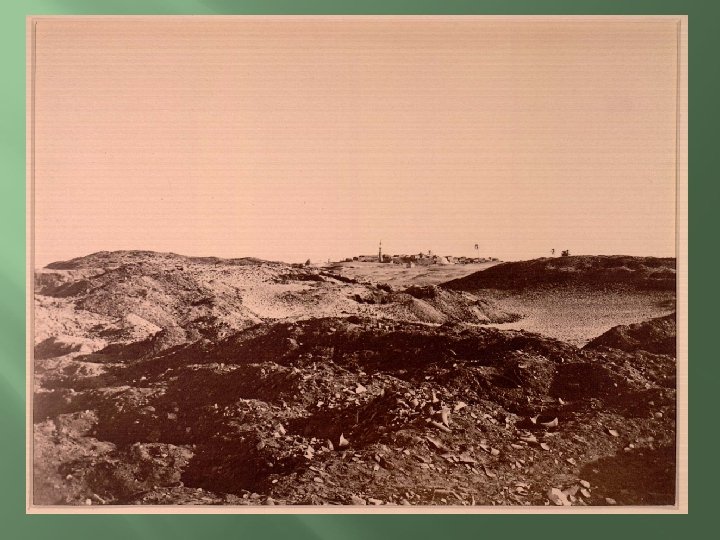

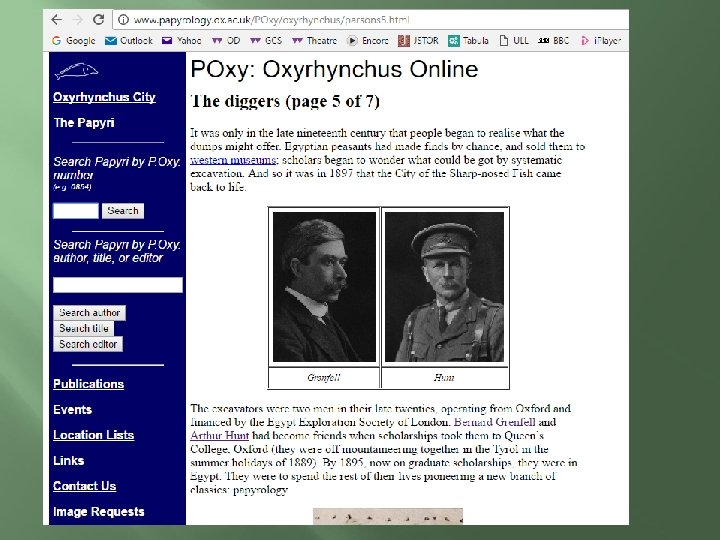

Oxyrhynchus Probably the most important site in the world where papyri have been excavated. The recovery of papyri began in the middle of the eighteenth century, when the remains of a Greek library of papyrus rolls were found in Italy at Herculaneum, preserved (carbonised) by the debris of an eruption of Vesuvius. By the end of the eighteenth century, a few papyri had been discovered in Egypt, the country whose dry climate is most favourable to their survival, and the number slowly grew. By the 1890 s, exciting finds of Greek literature, lost works by such authors as Aristotle and Hyperides, encouraged the Egypt Exploration Fund (later Society) to commission excavations specifically in search of papyri. In their second season, in 1896/7, B. P. Grenfell and A. S. Hunt, two young fellows of Queen’s College, Oxford, found the site that was to produce the largest collection of all — Oxyrhynchus.

Oxyrhynchus Its exotic name means ‘sharp-snouted (fish)’ and was the Greek for the Nile fish regarded as the incarnation of a god by the original inhabitants. In the Roman period it was a flourishing place with about twenty temples, colonnaded streets, and an open air theatre. When Christianity came, it was famous for the numbers of its monks and nuns. In the fifth century A. D. it had a hippodrome for chariot races and other shows. Almost nothing of all this remains. The stone was carted away for use elsewhere or burnt to produce lime to spread on the fields. A modern village now occupies part of the site. What Grenfell and Hunt found was the rubbish of Oxyrhynchus, which had been carried out and piled into a heap until it became more convenient to start another heap elsewhere, and so on. In the huge rubbish heaps were papyri, sometimes by the basketful, many rotted and fragile, but in such numbers that it took six seasons of excavation to bring them away. 103 volumes with transcripts, translations, and commentaries on the texts have been published so far. Many more volumes will be needed before all that is interesting has been extracted.

The Searchers, by Sophocles

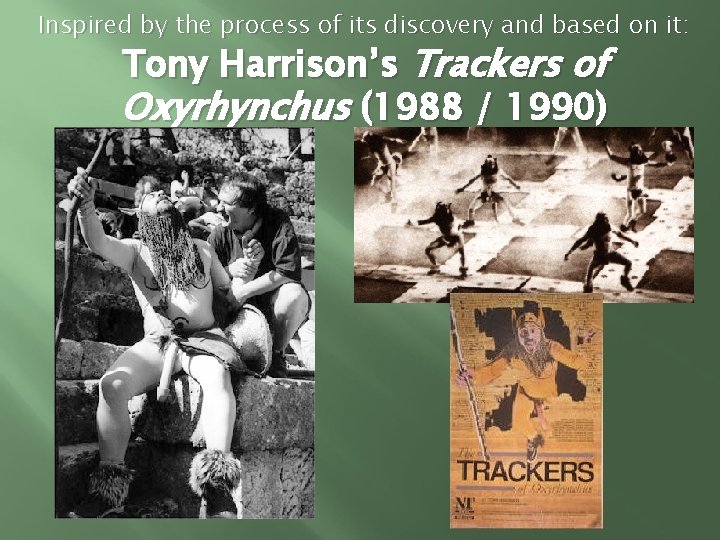

Inspired by the process of its discovery and based on it: Tony Harrison’s Trackers of Oxyrhynchus (1988 / 1990)

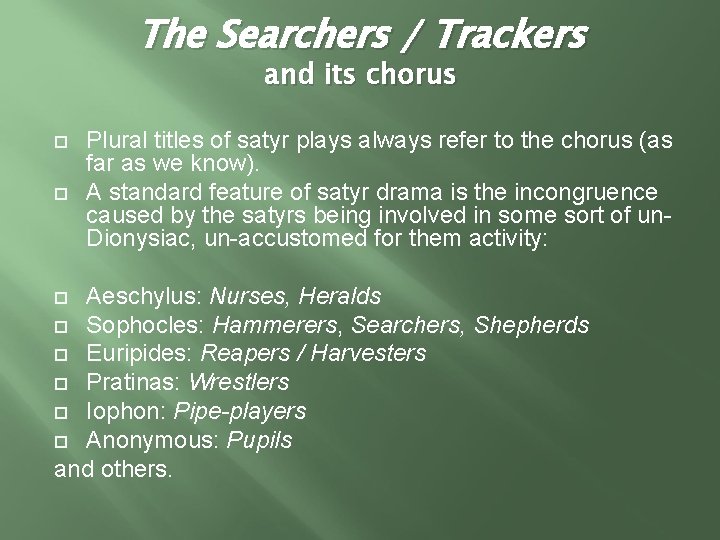

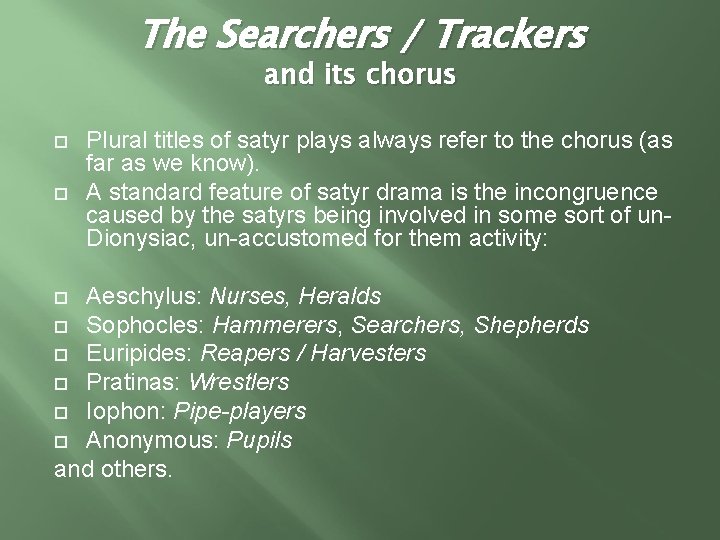

The Searchers / Trackers and its chorus Plural titles of satyr plays always refer to the chorus (as far as we know). A standard feature of satyr drama is the incongruence caused by the satyrs being involved in some sort of un. Dionysiac, un-accustomed for them activity: Aeschylus: Nurses, Heralds Sophocles: Hammerers, Searchers, Shepherds Euripides: Reapers / Harvesters Pratinas: Wrestlers Iophon: Pipe-players Anonymous: Pupils and others.

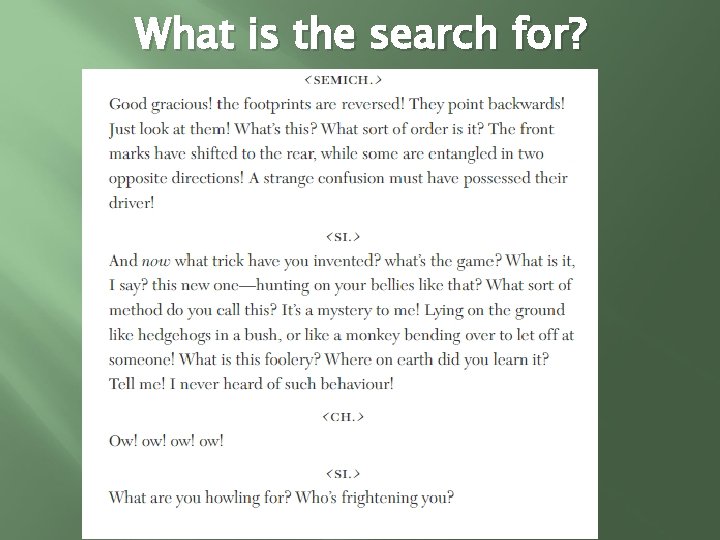

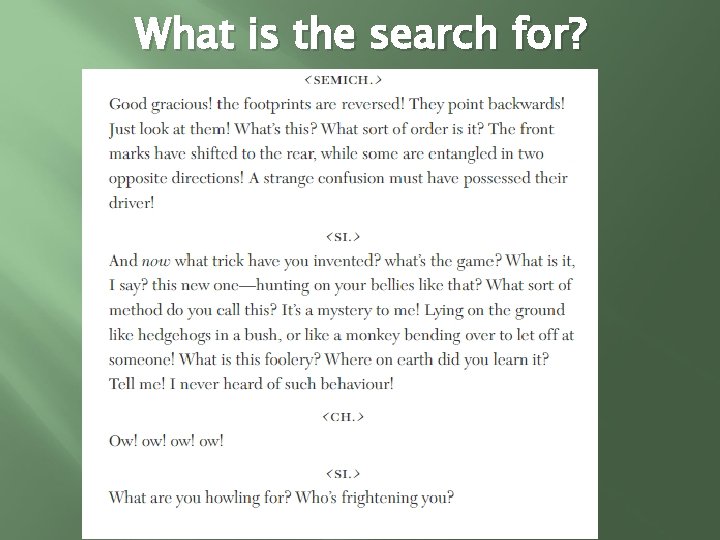

What is the search for?

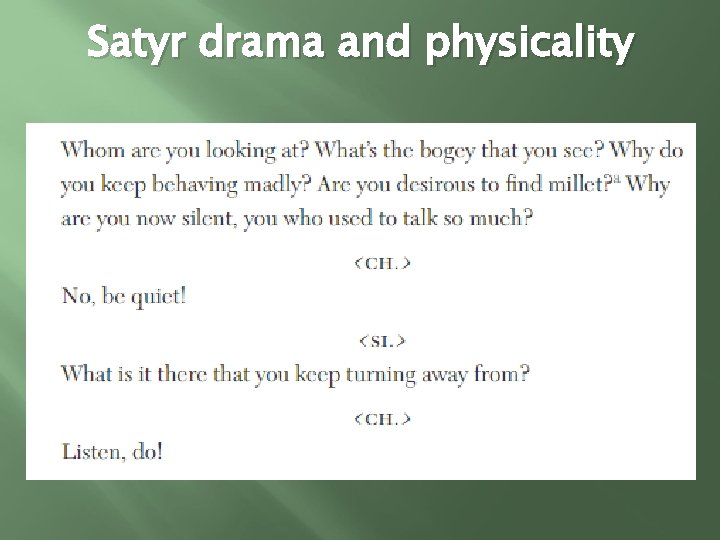

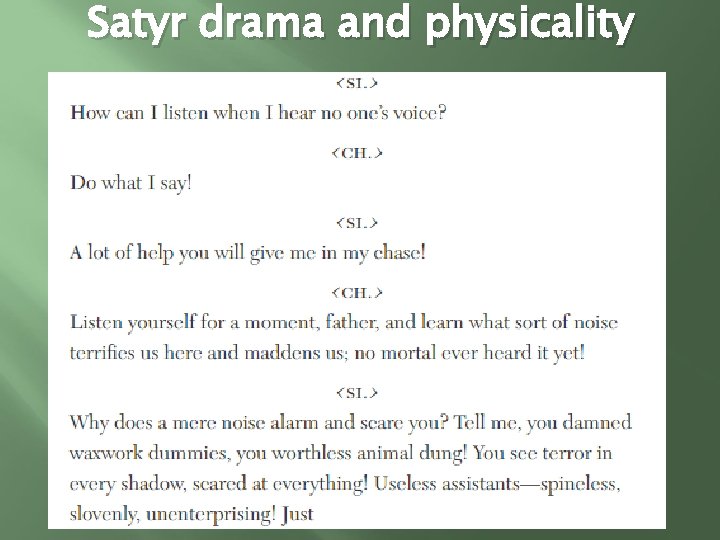

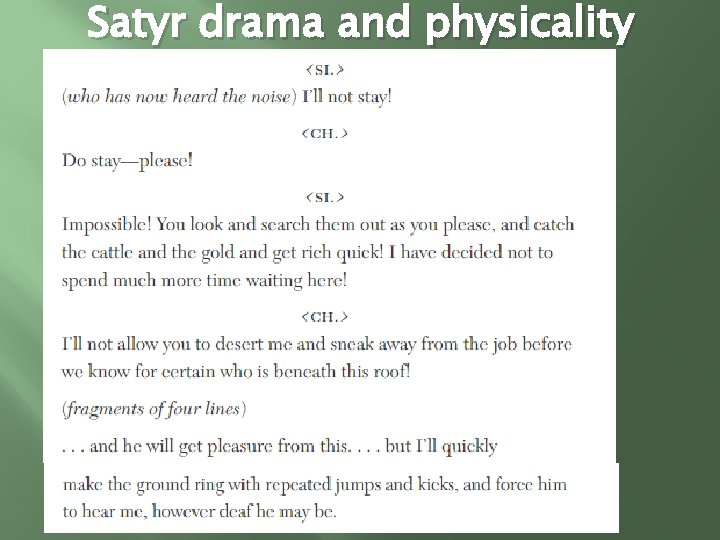

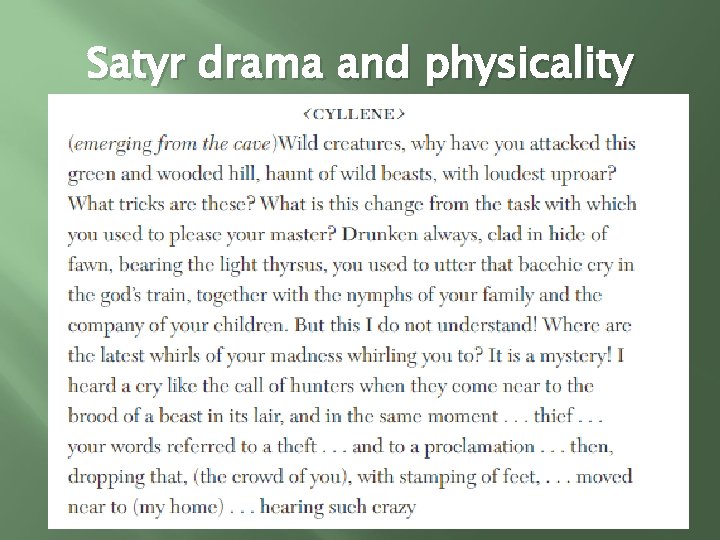

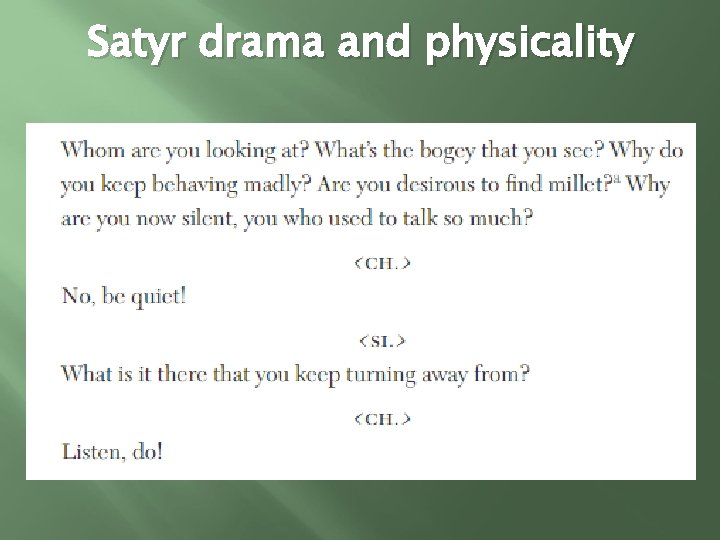

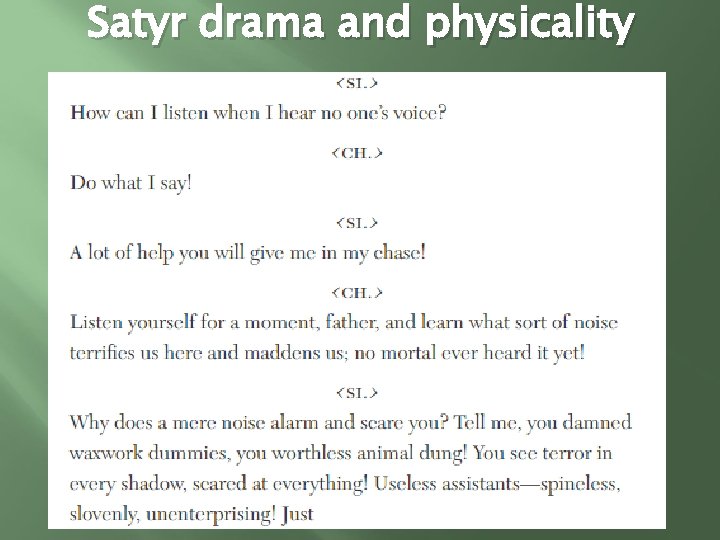

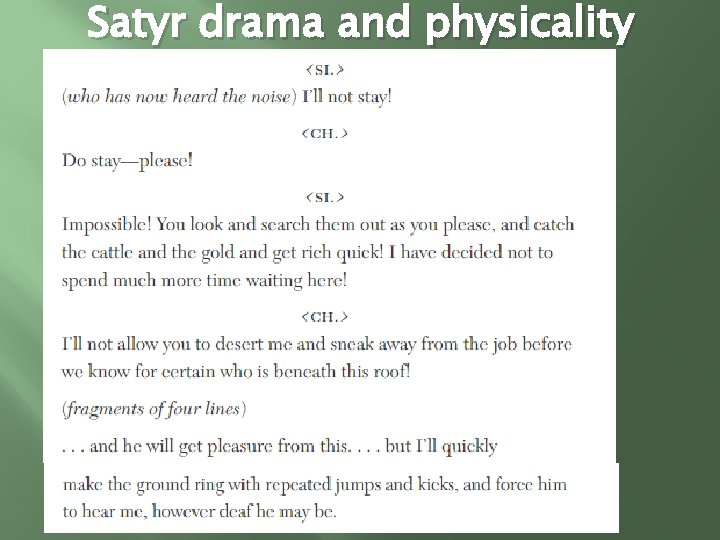

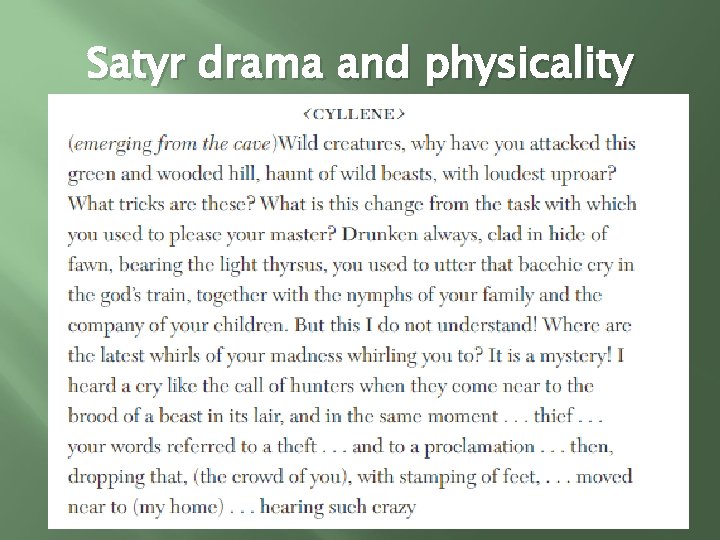

Satyr drama and physicality

Satyr drama and physicality

Satyr drama and physicality

Satyr drama and physicality

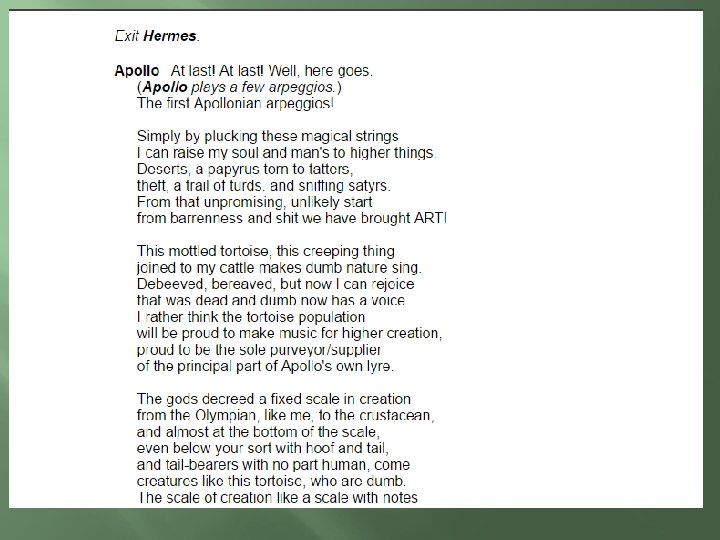

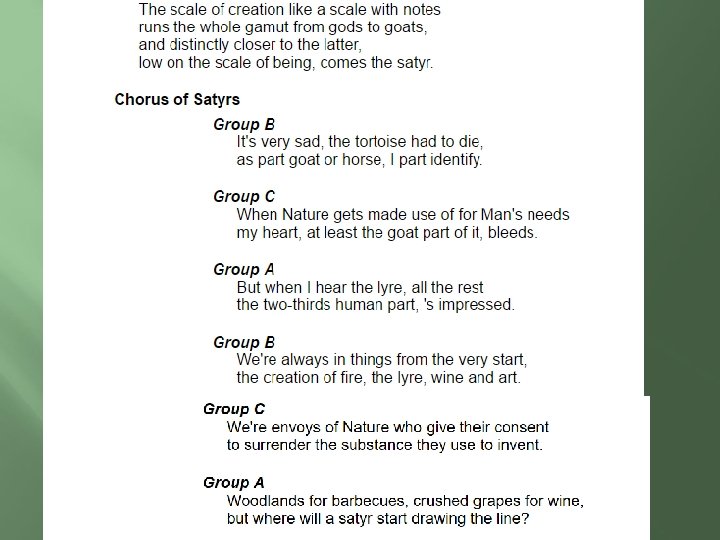

Recipe for a satyr play i. iii. Chorus of satyrs Mythical plot … … in a parodic form (i. e. Parody) Myth parody: Through the presence of the incongruous satyrs Twist of plot elements

Recipe for a satyr play Other ingredients: its stereotypical motifs which were always associated with satyr play’s Dionysiac nature iv. the estrangement of the satyrs from their master Dionysus, their engagement in an unaccustomed and abnormal for them activity and, finally, their return to their normal role as revellers and attendants of Dionysus Motif that often goes with it: Discovery of elements of civilisation (music (as in Searchers), wine (as in Cyclops), sports festivals (as in Spectators), agriculture (as in Harvesters), writing, etc. )

Recipe for a satyr play v. Captivity and Liberation vi. Rural, wild setting vii. Trickery and Fraud viii. Folk motifs, such as adventures with an ogre, miraculous events, emergence from the underworld

Function of Satyr Drama Known as ‘Playful Tragedy’ (Demetrios, On Style) Just Comic Relief after the terrors of tragedy? Not another form of Greek Comedy (although many elements in common) In many ways, sub-genre of tragedy

Function of Satyr Drama Relation to tragedy written by the tragic poets subjects drawn from the same myths which featured in tragedies shared in whole or in part the structural elements (prologue – parodos – episodes – choral songs called stasima – exodos), as well as the actors and the stage conventions of tragedy and the language and the meters of tragedy Overarching themes of tragedy, especially barbarity and civilisation

Function of Satyr Drama Making up for the lost Dionysiac element of tragedy? (‘Nothing to do with Dionysus!’) Close, but not exactly… Satyr drama was taken by the spectators to form an essential part of the tragic experience And its Dionysiac nature is the key to its attraction

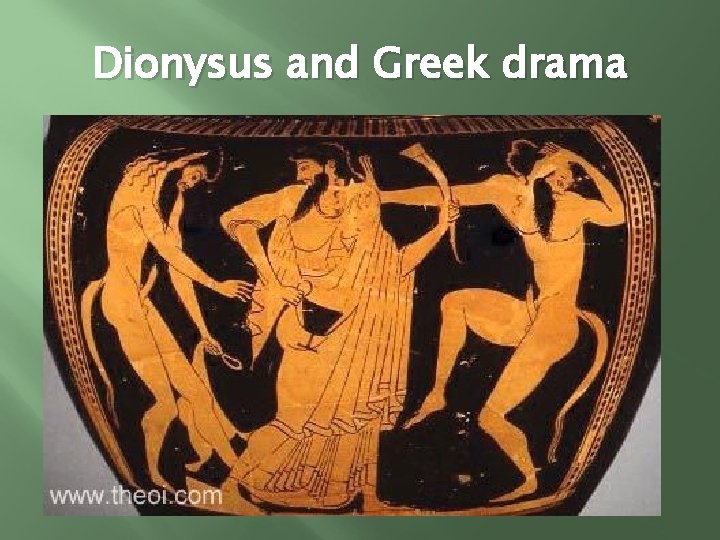

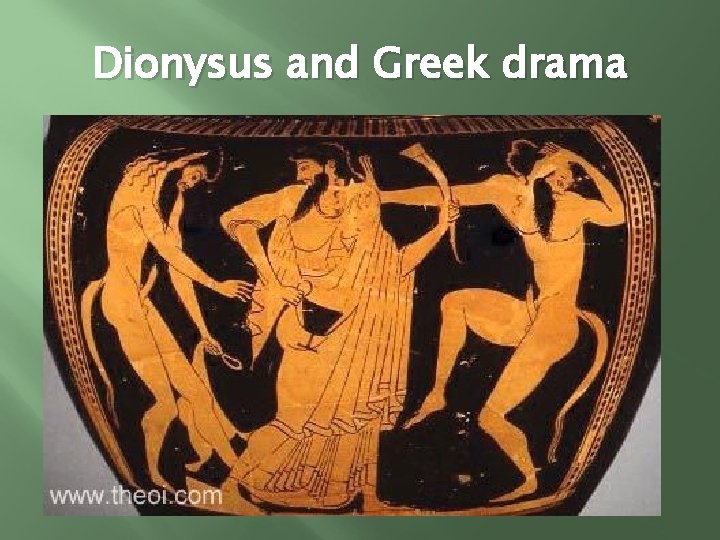

Dionysus and Greek drama

Dionysus in the Greek imagination The most elusive and versatile god of the Greek pantheon, the divinity who transcends and collapses even fundamental boundaries – those of human, animal and god, masculine and feminine, self and other. The Dionysiac is captured by a range symbols, ideas, and concepts, most of which fit into a rich but strangely coherent spectrum. Epithets of Dionysus capture the fact that at his essence is the recognition and acceptance of the wholeness of the human experience For example, epithets include Lysios (‘deliverer’), Eleuthereus (‘of freedom’), Meilichios (‘mild’), but also Mainoles (‘mad’, ‘raging’), Omestes (‘eater of raw flesh’) and ‘Anthroporraistos’ (‘man-slayer’). See encyclopedic entries uploaded on website

What is the function of Dionysus and the Dionysiac in a tragic tetralogy?

How is our understanding of the tragic experience different due to the loss of satyr plays? “With the loss of these plays we are lacking important clues to the wholeness of the Greek imagination, and its ability to absorb and yet not be defeated by the tragic. In the satyr play, that spirit of celebration, held in the dark solution of tragedy, is precipitated into release, and a release into the worship of the Dionysus who presided over the whole dramatic festival. ” Tony Harrison, introduction to the Trackers of Oxyrhynchus, in Tony Harrison: Plays, vol. 5

PS: The tension Dionysiacnon-Dionysiac and its meaning Satyrs try to escape from slavery to Dionysus; they engage in unaccustomed ‘secular’ profession ‘Discovery’ of element of civilisation comes out of that activity In the end the satyrs always return to Dionysus The pattern is clear (even from Cratinus’ satyrcomedy, see next time), but unfortunately we do not know for certain how it was used and what it meant But we can make an educated guess…

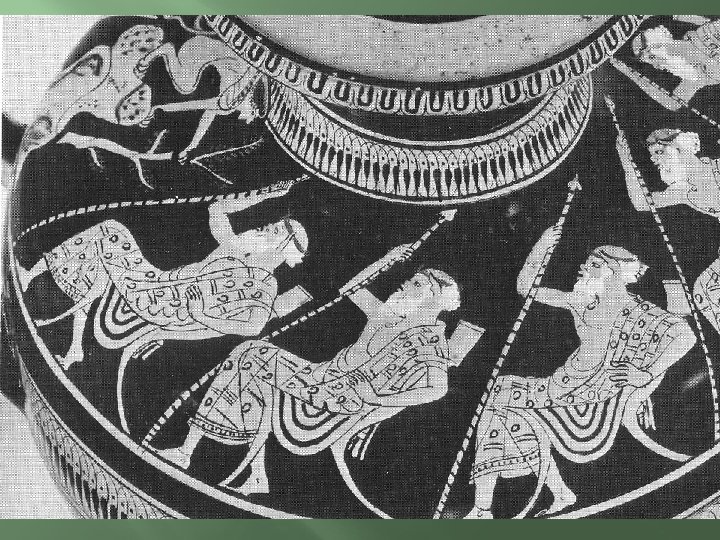

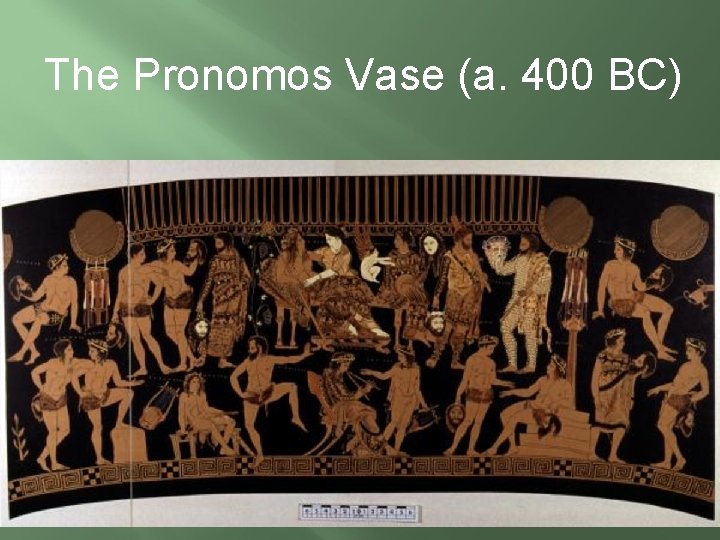

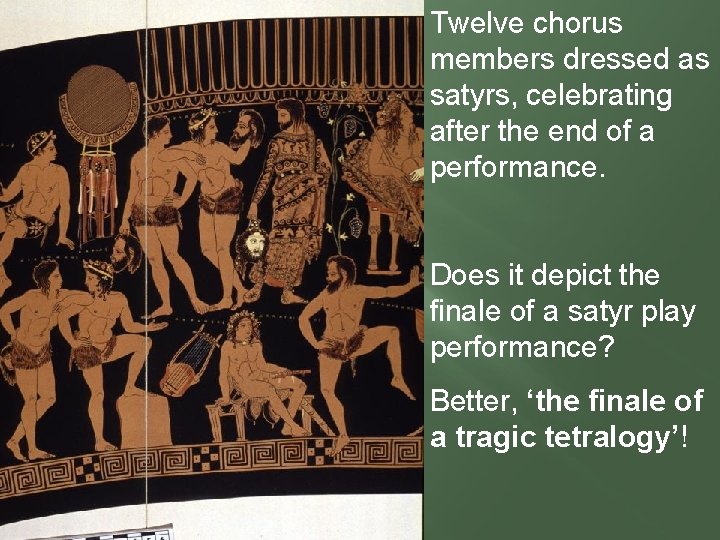

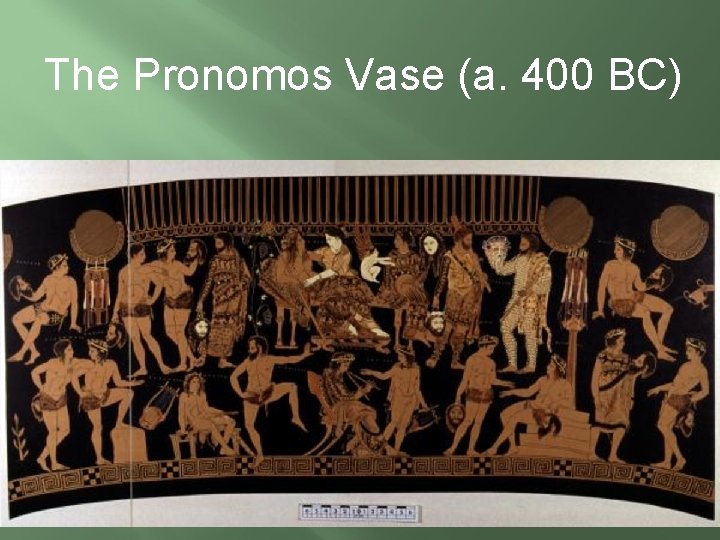

The Pronomos Vase (a. 400 BC)

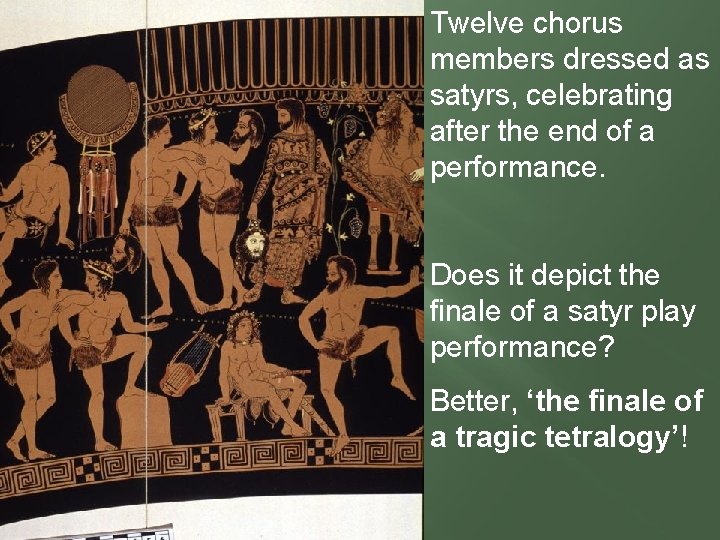

Twelve chorus members dressed as satyrs, celebrating after the end of a performance. Does it depict the finale of a satyr play performance? Better, ‘the finale of a tragic tetralogy’!

“In the one complete surviving satyr play, the Cyclops of Euripides, the very last line allows the chorus the prospect of being liberated finally from the dark shadow of the Cyclops Polyphemus and spend the rest of the time in the service of Bacchus: Hip, hurray! We’re on our way As ship-mates of the Ithacan! And happy days We’ll pass in praise Extolling Bacchus with a can! The journey back into the service of the presiding god seems to be paralleled by the release of the spirit back into the life of the senses at the end of the tragic journey. The sensual relish for life and its affirmation must have been the spirit of the conclusion of the four plays. The satyrs are included in the wholeness of the tragic vision. ” Tony Harrison (Continued from above)

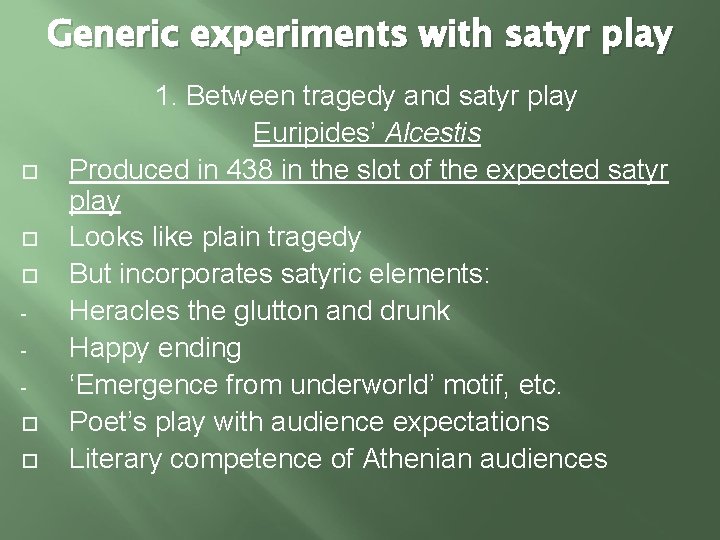

Generic experiments with satyr play 1. Between tragedy and satyr play Euripides’ Alcestis Produced in 438 in the slot of the expected satyr play Looks like plain tragedy But incorporates satyric elements: Heracles the glutton and drunk Happy ending ‘Emergence from underworld’ motif, etc. Poet’s play with audience expectations Literary competence of Athenian audiences

Harrison draws attention specifically to what he calls “the category-disturbing Alcestis, often termed proto-satyric because Euripides offered it in place of the satyr play as the fourth play of his competition entry. In this play Euripides introduced his ‘satyr’ , in the shape of Heracles, into the very body of the tragedy: the celebrant admitted before the tragic section had come to an end. The playwright thus showed both elements intertwined: at the same time the reveller is hasting to his wine and Admetus is burying his wife.

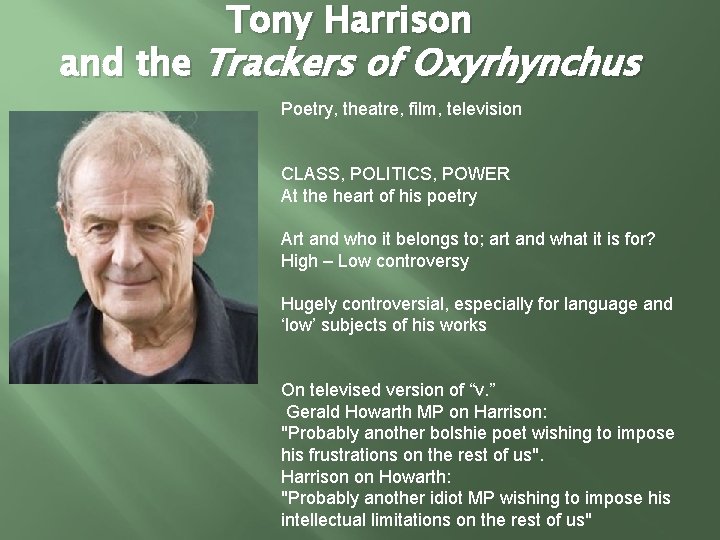

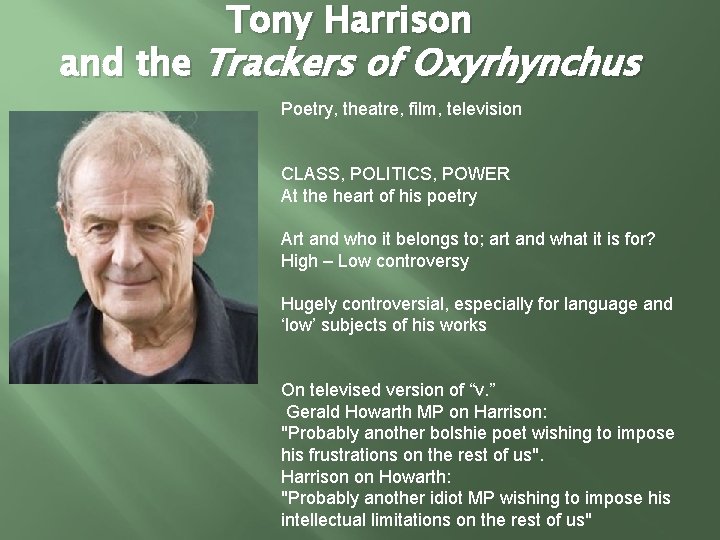

Tony Harrison and the Trackers of Oxyrhynchus Poetry, theatre, film, television CLASS, POLITICS, POWER At the heart of his poetry Art and who it belongs to; art and what it is for? High – Low controversy Hugely controversial, especially for language and ‘low’ subjects of his works On televised version of “v. ” Gerald Howarth MP on Harrison: "Probably another bolshie poet wishing to impose his frustrations on the rest of us". Harrison on Howarth: "Probably another idiot MP wishing to impose his intellectual limitations on the rest of us"

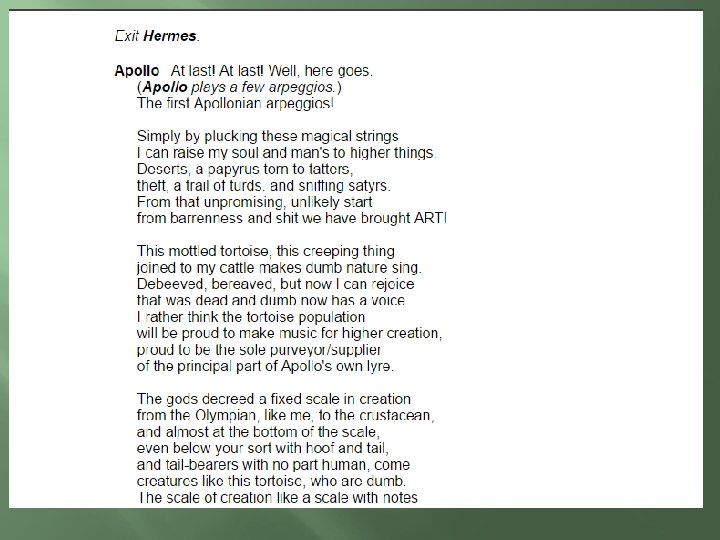

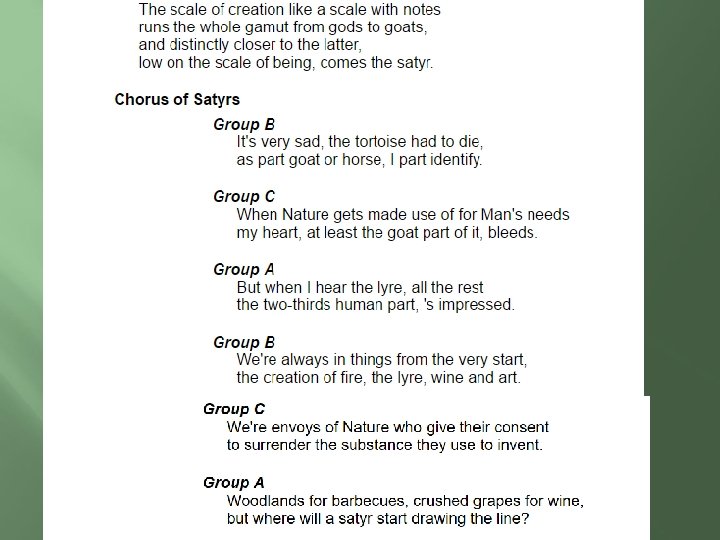

Rendering the physicality and sensuality of the original in the modern play The clog dance https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=M 0 Uuc 5 j. M 8 Dg

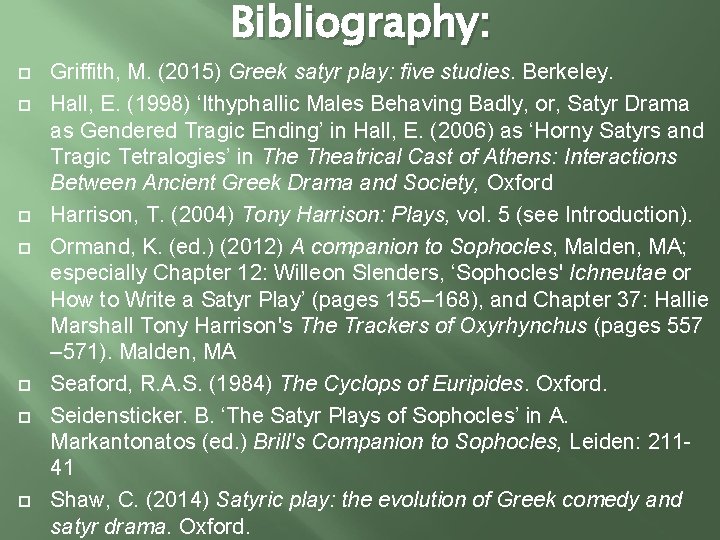

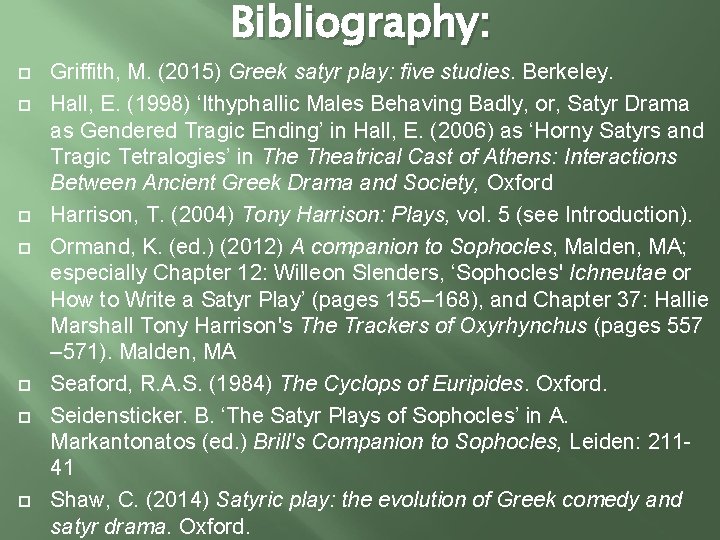

Bibliography: Griffith, M. (2015) Greek satyr play: five studies. Berkeley. Hall, E. (1998) ‘Ithyphallic Males Behaving Badly, or, Satyr Drama as Gendered Tragic Ending’ in Hall, E. (2006) as ‘Horny Satyrs and Tragic Tetralogies’ in Theatrical Cast of Athens: Interactions Between Ancient Greek Drama and Society, Oxford Harrison, T. (2004) Tony Harrison: Plays, vol. 5 (see Introduction). Ormand, K. (ed. ) (2012) A companion to Sophocles, Malden, MA; especially Chapter 12: Willeon Slenders, ‘Sophocles' Ichneutae or How to Write a Satyr Play’ (pages 155– 168), and Chapter 37: Hallie Marshall Tony Harrison's The Trackers of Oxyrhynchus (pages 557 – 571). Malden, MA Seaford, R. A. S. (1984) The Cyclops of Euripides. Oxford. Seidensticker. B. ‘The Satyr Plays of Sophocles’ in A. Markantonatos (ed. ) Brill's Companion to Sophocles, Leiden: 21141 Shaw, C. (2014) Satyric play: the evolution of Greek comedy and satyr drama. Oxford.

Satyr theater

Satyr theater What is the origin of greek drama

What is the origin of greek drama Shakespearean tragedy definition

Shakespearean tragedy definition Characteristics of shakespeare's tragedy

Characteristics of shakespeare's tragedy A character whose personality and attitude contrast sharply

A character whose personality and attitude contrast sharply When was drama invented

When was drama invented Tragedy literary term

Tragedy literary term Elizabethan drama the tragedy of hamlet unit test

Elizabethan drama the tragedy of hamlet unit test Opening stage directions examples

Opening stage directions examples Play within the play hamlet

Play within the play hamlet I've got a friend we like to play we play together

I've got a friend we like to play we play together Play random play basketball

Play random play basketball Typewriter types

Typewriter types A satire against reason and mankind theme

A satire against reason and mankind theme A satyr against mankind

A satyr against mankind Introduction of dramatization

Introduction of dramatization What is drama/play

What is drama/play Elements of drama pdf

Elements of drama pdf Moro moro props and costumes

Moro moro props and costumes Monologue

Monologue Dramatic play structure

Dramatic play structure Drama berasal dari bahasa yunani yang artinya

Drama berasal dari bahasa yunani yang artinya Drama serial drama serial

Drama serial drama serial Drama türleri

Drama türleri Natak

Natak Isotrotinoin

Isotrotinoin The tragedy of romeo and juliet prologue

The tragedy of romeo and juliet prologue Tragedy story example

Tragedy story example Hamlet unit test answers

Hamlet unit test answers Catharsis in macbeth

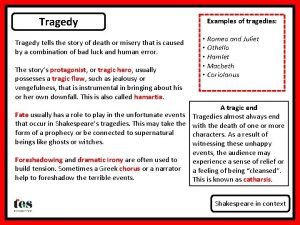

Catharsis in macbeth What is a tragedy

What is a tragedy Sarcasm in twelfth night

Sarcasm in twelfth night Oedipus family tree

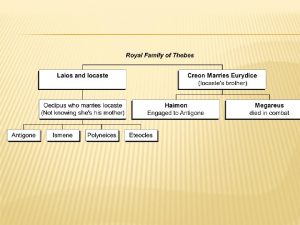

Oedipus family tree Romeo's father

Romeo's father Poisonous gas leaked in bhopal gas tragedy

Poisonous gas leaked in bhopal gas tragedy Catastrophe of questions

Catastrophe of questions Pathos in julius caesar

Pathos in julius caesar Jeopardy quotes

Jeopardy quotes Shakespeare othello themes

Shakespeare othello themes Ode greek theatre definition

Ode greek theatre definition Why was the inventor of tragedy important to theater

Why was the inventor of tragedy important to theater Ancient greek theatre costume

Ancient greek theatre costume Greek tragedy conventions

Greek tragedy conventions Love canal tragedy

Love canal tragedy Achilles heel story

Achilles heel story Characteristics of tragedy

Characteristics of tragedy Miss julie as a naturalistic tragedy

Miss julie as a naturalistic tragedy What is tragedy of the commons

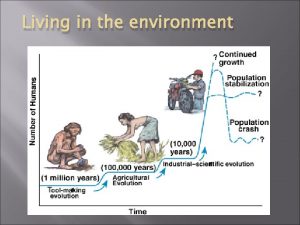

What is tragedy of the commons Rule of 70 population growth

Rule of 70 population growth Othello act 1 scene 1

Othello act 1 scene 1 Antigone greek mask

Antigone greek mask