Sampling Design for Impact Evaluation Alemayehu Worku Addis

- Slides: 59

Sampling Design for Impact Evaluation Alemayehu Worku Addis Ababa University/Addis Continental Institute of Public Health July 2016 International Workshop on Impact Evaluation of Population, Health and Nutrition Programs

Learning Objectives • Understand how to draw study units in the sample from a population of interest to precisely estimate differences in outcomes between treatment group and the comparison group • Able to determine the size of a sample/power calculation

Introduction Once you have chosen a method to select the comparison group, the next step in planning an impact evaluation is to determine what data you need and the sample required to estimate differences in outcomes between the treatment group and the comparison group You must determine both the size of the sample and how to draw the units in the sample from a population of interest

Sampling Procedures The three common sampling procedure in Impact Evaluation are: • Simple Random Sampling • Cluster Sampling • Stratified Random Sampling

Simple Random Sampling SRS is often used as a basic design to which the sampling variance of statistics using other sample designs are compared SRS assign an equal probability of selection to each frame element

Simple Random Sampling The mean of the variable y is The sampling variance of the mean (SE of the mean) is estimated by the term 1 -f is the finite population correction, or fpc When the fpc is close to 1,

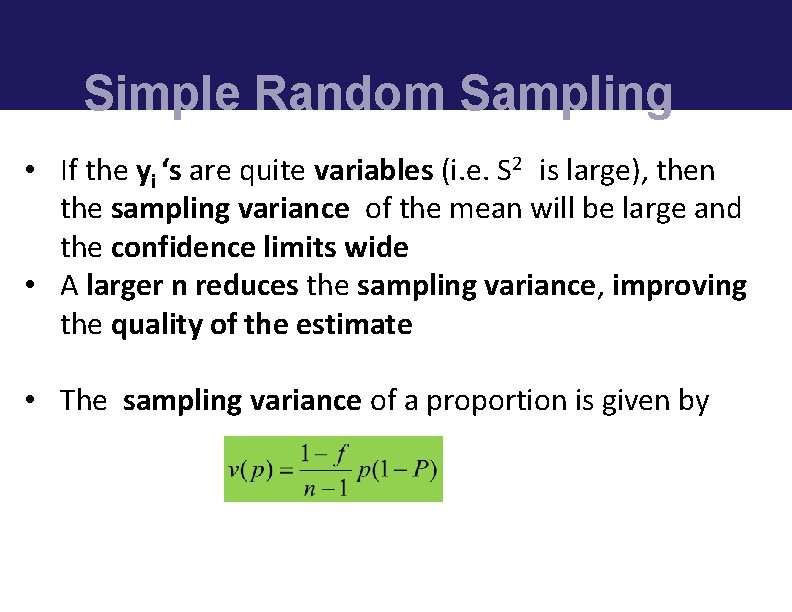

Simple Random Sampling • If the yi ‘s are quite variables (i. e. S 2 is large), then the sampling variance of the mean will be large and the confidence limits wide • A larger n reduces the sampling variance, improving the quality of the estimate • The sampling variance of a proportion is given by

Cluster Sampling Cluster sampling: • Divide the population into c subsets (clusters), each having b elements • • Select a of the c clusters Measure the total of the attribute of interest in each of the selected cluster If we select elements randomly from the selected clusters, the design effect of the sample mean will go down and the precession of the sample mean will increase

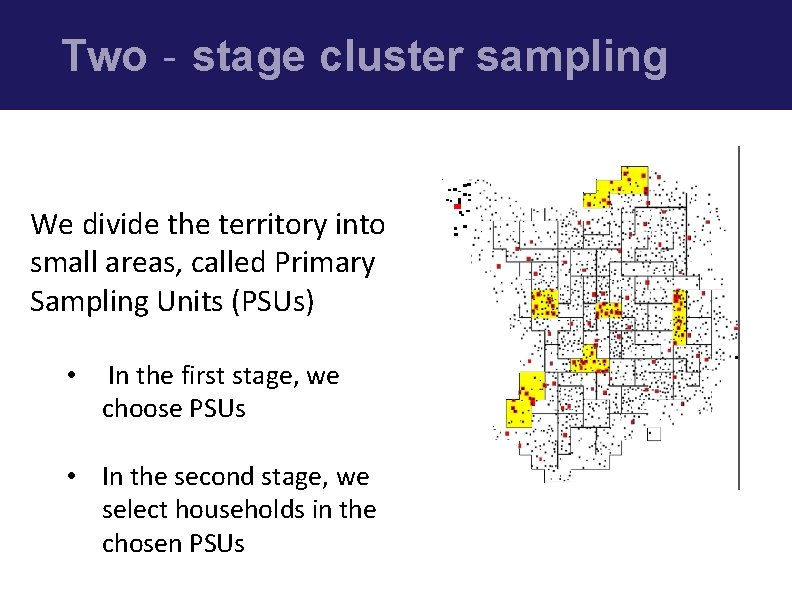

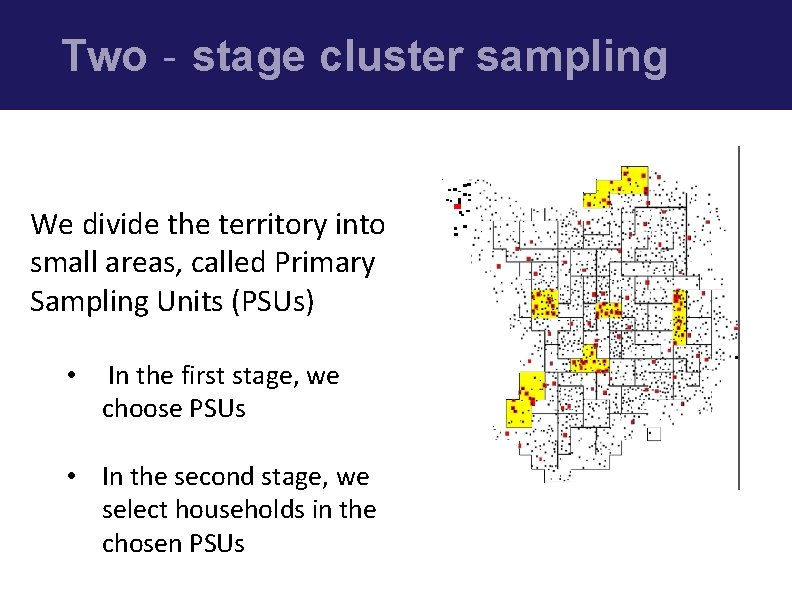

Two‐stage cluster sampling We divide the territory into small areas, called Primary Sampling Units (PSUs) • In the first stage, we choose PSUs • In the second stage, we select households in the chosen PSUs

Cluster Sampling The mean is Where there are =1, 2, …, a clusters in the sample; and =1, 2, …, b elements in each cluster The sampling variance is Where s 2 a is variability across the a clusters, i. e. , where

Cluster Sampling • The sampling variance of the cluster sample mean is larger. It is larger by the following ratio The statistic d 2 is referred to as the design effect. • It is widely used in survey sampling in sample size determination and in summarizing the effect of having sampled clusters instead of elements • Every statistic in a survey has its own design effect

Cluster Sampling • Cluster samples generally have increased variance relative to element samples • The more variability between cluster means, the more relatively homogeneous the elements are within the cluster • One way to measure the clustering effect is with an intraclass correlation among element values within a cluster, averaged across clusters

Cluster Sampling • The intraclass correlation measures the tendency for values of a variable within a cluster to be correlated among themselves, relative to values outside the cluster • The intraclass correlation, , which is the “rate of homogeneity” is almost always positive • We can link to the design effect that summarizes the change in sampling variance as we go from an SRS of size n to a cluster sample of size n • If b is the number of elements in a cluster

Cluster Sampling Cluster size (b) 1 10 Intra-class correlation (ρ ) 0. 005 0. 01 0. 02 0. 03 0. 04 0. 05 0. 1 0. 2 Design effects for selected combinations of cluster sample size and intraclass 1 1 1 1 correlation 0. 3 1 1. 05 1. 09 1. 18 1. 27 1. 36 1. 45 1. 90 2. 80 3. 70 15 1. 07 1. 14 1. 28 1. 47 1. 56 1. 70 2. 40 3. 80 5. 20 20 1. 19 1. 38 1. 57 1. 76 1. 95 2. 90 4. 80 6. 70 30 1. 15 1. 29 1. 58 1. 87 2. 16 2. 45 3. 90 6. 80 9. 70 50 1. 25 1. 49 1. 98 2. 47 2. 96 3. 45 5. 90 10. 80 15. 70

Cluster Sampling

Cluster Sampling

Cluster Sampling • The optimum number of cluster size/households to be selected in each cluster/PSU will depend on the data-collection cost structure and the degree of homogeneity or clustering with respect to the survey variables within the PSU. The optimum choice for b that minimizes the variance of the sample mean is approximately given by where C 1 and C 2 are, respectively, the cost of an additional PSU and the cost of an additional household

Cluster Sampling • The interclass correlaltion can be expressed as Where: is between-cluster component of variance is within-cluster component of variance ranges between 0 ( = 0) and 1 ( = 0)

Cluster Sampling The cluster sampling variance for proportion can be expressed as a function of the variance between units, , not between total cluster.

Stratified Sampling • Probability sampling design can be made better with features to assure representation of population subgroups in the sample • Stratification is one such feature • On a frame of population elements, assume that there is information for every element on the list that can used to divided elements into separate groups or strata. • Strata are mutually exclusive groups of elements on a sampling frame • Independent selections are made from each stratum, one by one

Stratified Sampling HOW We divide the population into subgroups, called strata We take a separate sample in each stratum WHEN Stratification may be needed if: We want to reduce the standard error, by gaining control of the composition of the sample We want to assure the representativity of certain groups

Stratified Sampling • To estimate the whole population, results must be combined across strata • One method weights stratum results by the population proportion in stratum h, wh if the allocation is proportional • Suppose we are interested in estimating a mean for the population, and we have computed means for each stratum, the stratified estimate of the population mean is

Stratified Sampling • The sampling variance of the mean is

Stratified Sampling • The estimation procedure for proportion is similar to the one for mean

Sampling weights • Inverse of the net sampling probability • Interpretation: the sampling weight for a sampled individual is the number of individuals his/her data “represent”

Example--sampling weights • There are individuals in a population stratum 1: 50 individuals aged 18 -29 stratum 2: 100 individuals aged 30 -69 • We sample 10 from each stratum • Sampling probabilities are stratum 1: 10/50 = 0. 20 stratum 2: 10/100 = 0. 10

Example: sampling weights • Sampling weights stratum 1: 1/0. 20 = 5 stratum 2: 1/0. 10 = 10 • Interpretation: • Each sampled individual in stratum 1 represents 5 individuals • Each sampled individual in stratum 2 represents 10 individuals

Non-response rate adjustment? • 1 individual in the stratum 1 sample and 3 individuals in the stratum 2 sample refuse to participate in the survey • Net sampling probabilities stratum 1: 9/50 = 0. 18 stratum 2: 7/100 = 0. 07 • Sampling weights revised for non-response stratum 1: 1/0. 18 = 5. 56 stratum 2: 1/0. 07 = 14. 29 • This computation is often done by multiplying the original sampling weights by adjustment factors to account for non-response rates

Post-stratification weighting • Define strata, which may or may not have been used as strata in the sampling design • Compute sampling probabilities = proportion of each stratum that was actually sampled • Compute sampling weights from these sampling probabilities • Allows post-hoc treatment of unequal representation of population segments in the sample

Power Calculation • To assess the impact of the intervention on the outcomes of interest, if power calculations to determine sample sizes are not used correctly, researchers are likely to reach incorrect conclusions about whether or not the intervention works • Two main concerns support the need to perform power calculations: sample sizes can be too small and sample size can be too large

Power Calculation • Power calculation helps to avoid the consequences of having a sample that is too small to detect the smallest magnitude of interest in the outcome variable • Having a sample size smaller than statistically required increases the likelihood of researchers concluding that the evaluated intervention has no impact when the intervention does, indeed • For costefficiency and value-for-money it is important to ensure that an evaluation research design does not use a larger sample size than is required to detect the minimum detectable effect of interest

Power Calculation • some indicators may not be amenable to impact evaluation in relatively small samples • Detecting impacts for outcome indicators that are extremely variable, rare events, or that are likely to be only marginally affected by an intervention may require prohibitively large samples • E. G. , Identifying the impact of an intervention on maternal mortality rates will be feasible only in a sample that contains many pregnant women

Power Calculation • Most impact evaluations test a simple hypothesis embodied in the question, Does the program have an impact? In other words, Is the program impact different from zero? Answering this question requires two steps: 1. Estimate the average outcomes for the treatment and comparison groups 2. Assess whether a difference exists between the average outcome for the treatment group and the average outcome for the comparison group • The key question is, exactly how large must the sample be to allow you to know that a positive estimated impact is due to true program impact, rather than to lack of precision in your estimates?

Power Calculation • The power (or statistical power) of an impact evaluation is the probability that it will detect a difference between the treatment and comparison groups, when in fact one exists • An impact evaluation has high power if a type II error is unlikely to happen, meaning that you are unlikely to be disappointed by results showing that the program being evaluated has had no impact, when in reality it did have an impact • Power calculation indicate the smallest sample size required for an evaluation design to detect a meaningful difference (Minimum Detectable Effect) in outcomes between the treatment and comparison groups

Power Calculation • Power analysis is the decision-making process about sample size, given real-world constraints, including budget, time, accessibility of samples of interest, distance, surveyor safety concerns, politics and the policy-relevant magnitudes of effects in policyrelevant time frames • Power analysis tries to optimise sample size and power against these constraints • Though power calculation is an ex ante process, there are instances when ex post power calculations can be performed

Power Calculation

Power Calculation • Power calculation requires examining the following questions: Does the program create clusters? What is the outcome indicator? Do you aim to compare program impacts between subgroups? • What is the minimum detectable effect (MDE) that would justify the investment that has been made in the intervention? • The level of significance ( ) • What is a reasonable level of power (1 - ) for the evaluation being conducted? • • •

Power Calculation Power calculation requires examining the following questions: Graphical visualisation of critical statistical power and other key parameters

Power Calculation • Power calculation requires examining the following questions: • Statistical tests can be performed as one-sided or two-sided: specifying which will be used is important for power calculations. • One-sided statistical tests are used when the alternative hypothesis is expected to be unidirectional. • Two-sided statistical tests are used when the alternative hypothesis is nondirectional

Power Calculation • Power calculation requires examining the following questions: The proportion of the study sample that is randomly assigned to the treatment group: optimization of statistical power suggests 50/50 treatment/control group allocation • What are the baseline mean/prevalence and variance of the outcome indicators? • coefficient of variation and intra class correlation • Attrition, which refers to a reduction of the initial sample size involved in a study •

Power Calculation • If a study does not detect a statistically significant effect of an intervention, it does not necessarily mean that the study is underpowered. It may be because the intervention fails to deliver according to plan (implementation failure) or it is just not the right intervention for the problem at hand. Do not blame power whenever there is no statistically significant result…

Power Calculation: Simple random sampling § §

Power Calculation: Two stage cluster sampling Sample size for continuous outcome D is the effect size or how much of an impact your project will have Sample size for binary outcome

Rules of thumb for power calculation 1. Even though power calculation is a technical task, it is also true that there a few rules of thumb that are applied and can always serve as guidance. 2. When power increases, the probability to find a true impact of the intervention (if it exists) increases. In social science, researchers aim to have at least 80% power which means allowing 20% chance of committing a type II error. 3. The larger your sample size, the smaller the standard error and therefore the higher your power. 4. The smaller the Minimum Detectable Effect, the larger the sample size needs to be. 5. For any given number of clusters, the larger the intracluster correlation, the lower the power.

Rules of thumb for power calculation 6. For any given number of unit of observation per cluster, the larger the number of clusters the higher the power. 7. Increasing the units of observation per clusters will generally not improve power as much as would increase the number of clusters (unless ICC is 0). 8. Intra-cluster correlation increases when observations within clusters are getting more and more identical relative to other clusters, which lowers the number of independent observations and, effectively, the sample size. 9. Baseline covariates are used in model specification to increase the statistical power of the study because they reduce the standard error of outcome and therefore increase the likelihood to reduce the minimum effect that the design can detect.

Common pitfalls for power calculation • Sample size should be determined for all main outcome variables before final decision on study sample size is made. It is not appropriate for instance to run power calculation only for school attendance when, for instance, learning outcomes are also a main outcome of interest. • Minimum Detectable Effect of an intervention is highly a function of the impact trajectory of the intervention over time. and therefore it is necessary and essential to take into account the expected timeline of the intervention to evaluate before deciding the magnitude of the Minimum Detectable Effect. • Power calculations must account for intra-cluster correlation in case of cluster sampling, as it does affect power. That is,

Summary of power calculation

Example: Simple random sampling 1. 42% youth unemployment rate (national survey Jan 2014). 2. Youth wage voucher programme to reduce unemployment to 20% in 2 years 3. 4000 youngsters are eligible 4. Minister decides 420 equally distributed in T and C groups. 5. You lead a 3 ie impact evaluation team and a journalist asks you: Do you think that a sample size of 420 is enough for the evaluation?

Example: Simple random sampling t(1 - β)=0. 84 (if β=0. 2) and t(1 -α/2)=1. 96 (if α =0. 05) IF power is 80%, β=0. 2 and α =0. 05 then n =(((1. 96+0. 84)/0. 22)^2)*(2*(0. 42*(1 -0. 42)))=79 participants in each group 158 participants in total. Assuming 5% attrition rate, we may plan to sample 83 participants by group 166 participants in total YES 420 participants is enough if not far beyond what is required.

Example: Simple random sampling 3 i Manual

Example: Single-level trials with a continuous outcome variable • A research team is planning to do an experiment to determine if an apprenticeship programme increases annual earnings of youth in Kisumu, Kenya. • Due to budget constraints, the study can only afford 1, 000 participants. • Fifty per cent will be assigned to the treatment group and the rest will be assigned to the control group. The research team is uncertain of the direction of the impact, so they opt to use a twosided hypothesis test. They set the significance level at 0. 05 and decide to use 80 per cent statistical power.

Example: Single-level trials with a continuous outcome variable This example has the following parameter values: t 1 = 1. 96, t 2= 0. 84, σy = 2, 400 Kenyan shillings, p = 0. 5 and n = 1, 000, which yields MDE = 425. 7 Kenyan shillings.

Example: Two stage cluster sampling 1. 42% youth unemployment rate (national survey Jan 2014) 2. Youth wage voucher programme to reduce unemployment to 20% in 2 years 3. 4000 youngsters are eligible 4. Minister decides 15 youngsters in 28 communities (420 youngsters) equally distributed in T and C communities. 5. You lead a 3 ie impact evaluation team and a journalist asks you: Do you think that a sample size of 420, 15 youngsters in 28 communities, is enough for the evaluation?

Example: Two stage cluster sampling t(1 - β)=0. 84 (if β=0. 2) ; t(1 -α/2)=1. 96 (if α =0. 05) and ρ = 0. 2, CV=0. 55 n=m*k=15*16= 240 participants 5% attrition out of 15 1 extra/community 245 in total YES a sample size of 420 is enough for the evaluation

Example: Two-level cluster randomised controlled trials with individual-level outcomes (binary outcome) • In North Cameroon, one of the leading causes of morbidity among children under 5 years is vitamin A deficiency. In order to address this problem, a not-for-profit organisation works to educate mothers on the importance of vitamin A. Specifically, organisation staff visit houses where there are children under 5 years old, and if a vitamin A supplement is not being administered to a child, the mother or caregiver is advised to visit the closest health facility to receive a supplement. In order to evaluate whether this approach reduces morbidity, the organisation is working with a research team from the University of Maroua. • The research team will evaluate the impact of this intervention (door-to-door visits for promoting vitamin A

Example: Two-level cluster randomised controlled trials with individual-level outcomes (binary outcome) • To avoid contamination, the research team decides to conduct a cluster randomised controlled trial where a cluster is defined as a health facility catchment area constituted of a few villages. Half of the health facilities will be assigned to the intervention group and the other half will be assigned to the control group. In each village, 50 children will be sampled in the catchment area served by the health facility. • A survey conducted by the organisation a few years previously indicates that the proportion of children already receiving a vitamin A supplement is 0. 25 and that k is equal to 0. 25. The aim of the organisation is to increase this coverage to 0. 65. • Using a two-sided hypothesis test at the 0. 01 significance level, the research team will calculate the number of health facilities required in each group for a study with 80 per cent statistical power.

Example: Two-level cluster randomised controlled trials with individual-level outcomes (binary outcome) On the basis of this example, z 1 = 2. 58, z 2 = 0. 84, μ 0 = 0. 25, μ 1 = 0. 65, k = 0. 25 and n = 50, which yields four health facilities (clusters) in each group.

References Djimeu, EW and Houndolo, D-G, 2016. Power calculation for causal inference in social science: sample size and minimum detectable effect determination, 3 ie impact evaluation manual, 3 ie Working Paper 26. New Delhi: International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3 ie) Paul J. Gertler, Sebastian Martinez, Patrick Premand, Laura B. Rawlings, Christel M. J. Vermeersch. Impact Evaluation in Practice. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 2011, Washington DC Reober M. Groves, Flyd J. Fowler, JR. , Mick P. Couper; James M. Lepkowski, Eleanor Singer, and Roger Tourangean. Survey Methodology; Wiley Series in Survey Methodology 2004, Hobokrem, new Jersey MEASURE Evaluation Manual Series, No. 3. July 2001. SAMPLING MANUAL for FACILITY SURVEYS for Population, Maternal Health, Child Health and STD Programs in Developing Countries

This presentation was produced with the support of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of MEASURE Evaluation cooperative agreement AID-OAA-L-14 -00004. MEASURE Evaluation is implemented by the Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partnership with ICF International; John Snow, Inc. ; Management Sciences for Health; Palladium; and Tulane University. Views expressed are not necessarily those of USAID or the United States government. www. measureevaluation. org