Sample Efficiency Generalisation and Robustness in Multilingual NLP

Sample Efficiency, Generalisation, and Robustness in Multilingual NLP Edoardo Maria Ponti Mila Montreal and University of Cambridge ep 490@cam. ac. uk

1. Motivation and Background 2. Sample Efficiency via Inductive Biases 3. Generalisation via Modularity 4. Robustness via non-Bayes Criteria 5. Conclusions

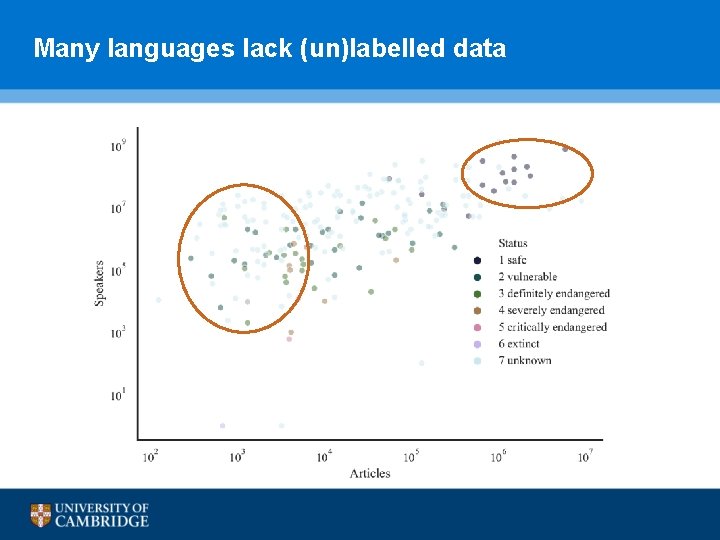

Many languages lack (un)labelled data

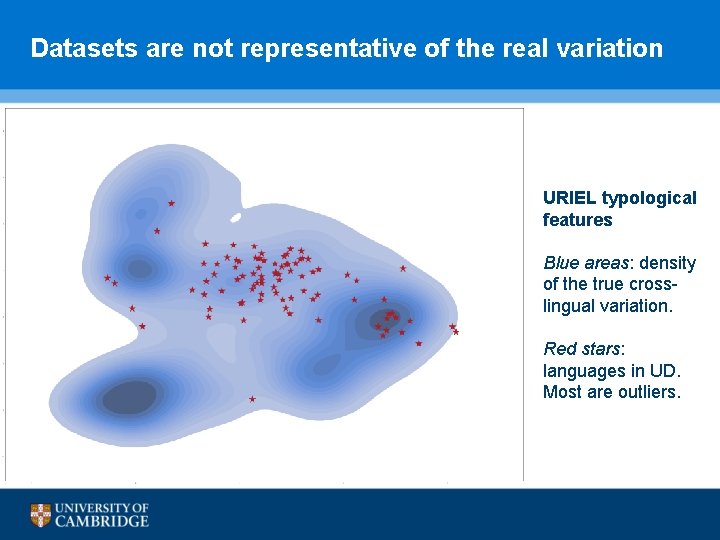

Datasets are not representative of the real variation URIEL typological features Blue areas: density of the true crosslingual variation. Red stars: languages in UD. Most are outliers.

Paradigms of learning Machine learning A child’s brain 1. Massive data, from scratch 1. Sample efficiency 2. Catastrophic forgetting 2. Continuous learning 3. Limited to observed domains 3. Generalisation to new domains 4. Over-confident predictions 4. Robustness to uncertainty

Bayesian Neural Networks Solutions in this framework Desiderata 1. Inductive bias through prior 1. Sample efficiency 2. Bayesian updating 2. Continuous learning 3. Modular design through graphical models 3. Generalisation to new domains 4. Bayesian model averaging 4. Robustness to uncertainty

1. Motivation and Background 2. Sample Efficiency via Inductive Biases 3. Generalisation via Modularity 4. Robustness via non-Bayes Criteria 5. Conclusions

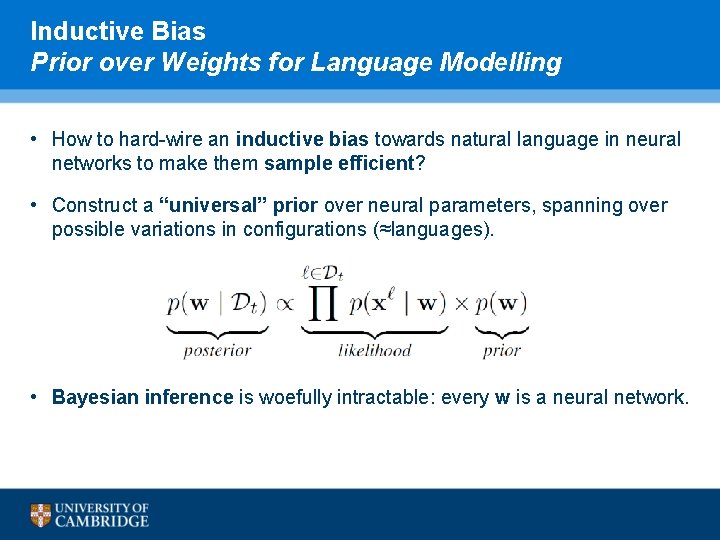

Inductive Bias Prior over Weights for Language Modelling • How to hard-wire an inductive bias towards natural language in neural networks to make them sample efficient? • Construct a “universal” prior over neural parameters, spanning over possible variations in configurations (≈languages). • Bayesian inference is woefully intractable: every w is a neural network.

Laplace Approximation

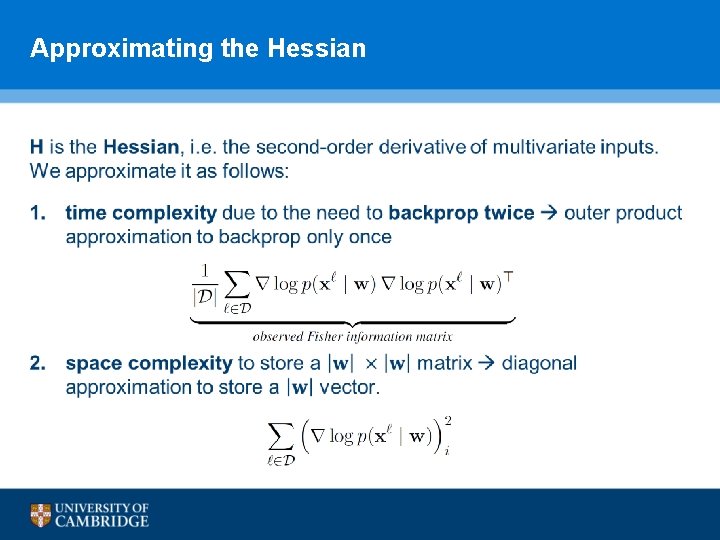

Approximating the Hessian •

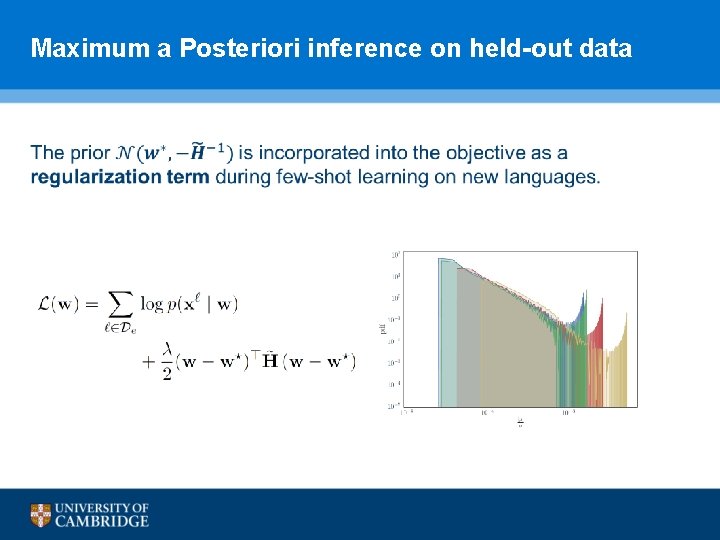

Maximum a Posteriori inference on held-out data •

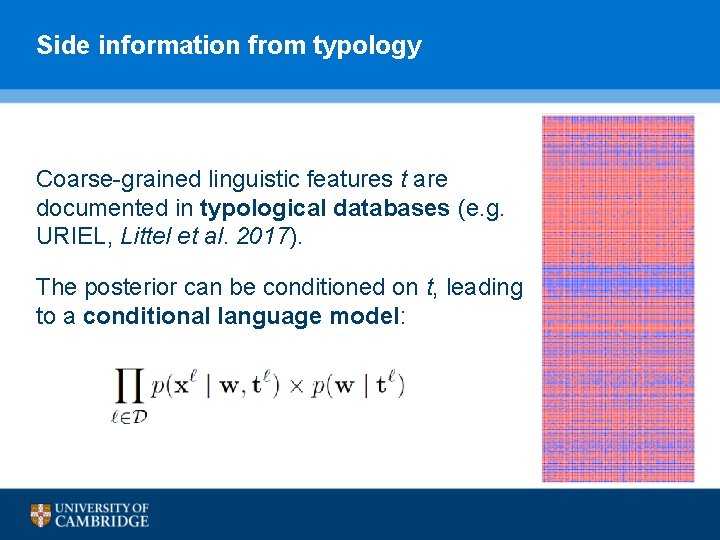

Side information from typology Coarse-grained linguistic features t are documented in typological databases (e. g. URIEL, Littel et al. 2017). The posterior can be conditioned on t, leading to a conditional language model:

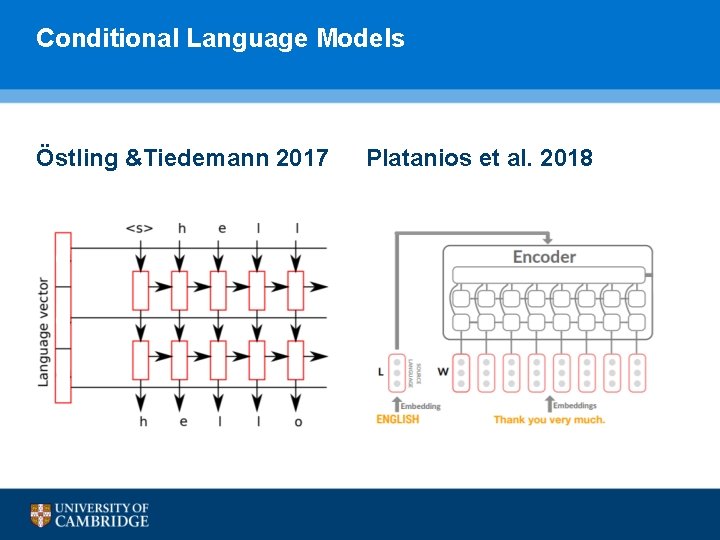

Conditional Language Models Östling &Tiedemann 2017 Platanios et al. 2018

Sample of languages Bible corpus (Christodoulopoulos and Steedman 2015)

Experiment setup • We randomly partitioned our sample into 4 subsets of 20 languages. • In each experiment iteration, a subset is held out. • The remaining 60 languages are considered as seen. Prior Parameters Non-informative: Informative: Data Paucity (# examples in held-out language) Zero-shot learning: 0 Few-shot learning: 100

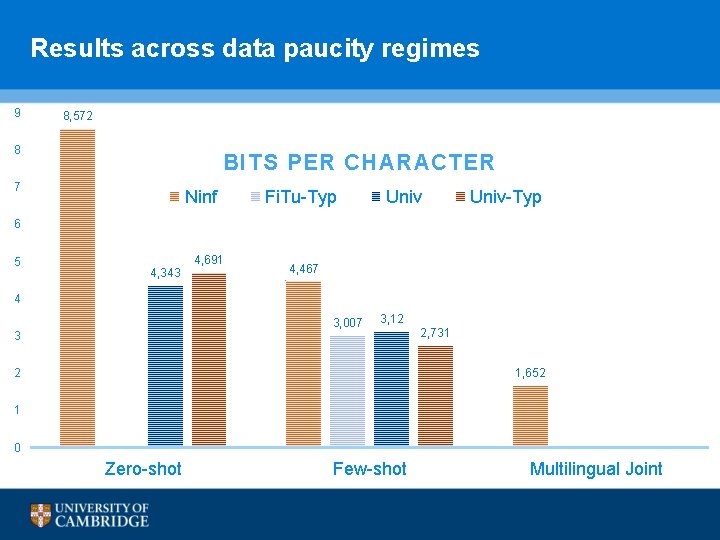

Results across data paucity regimes 9 8, 572 8 BITS PER CHARACTER 7 Ninf Fi. Tu-Typ Univ-Typ 6 5 4, 343 4, 691 4, 467 4 3, 007 3 3, 12 2 2, 731 1, 652 1 0 Zero-shot Few-shot Multilingual Joint

Conclusions • Laplace’s method allows us to construct a prior truly imbued of universal (phono-tactic) knowledge. • The universal prior significantly out-performs baselines with uninformative priors (including fine-tuning) across the board. • Mixed results for adding side typological information: + in the fewshot setting, but - in the zero-shot setting.

1. Motivation and Background 2. Sample Efficiency via Inductive Biases 3. Generalisation via Modularity 4. Robustness via non-Bayes Criteria 5. Conclusions

Intuition • Possible tasks are the Cartesian product of different dimensions: applications (QA, Dialogue, …), languages (Chinese, English, …), modalities (text, vision, …). Most combinations lack training examples. • Core assumption: the neural parameter space is structured and can be factorized into separate variables, one for each application, language, and modality. • Disentangling and recombining knowledge should lead to systematic generalisation for zero-shot predictions in new combinations. • For instance, observing task A in language 1 and task B in language 2 should be sufficient to make predictions for new combinations A 2 and B 1.

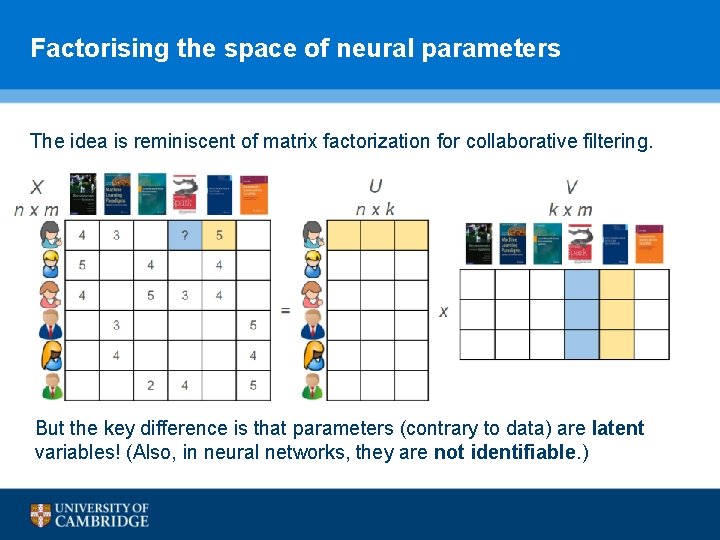

Factorising the space of neural parameters The idea is reminiscent of matrix factorization for collaborative filtering. But the key difference is that parameters (contrary to data) are latent variables! (Also, in neural networks, they are not identifiable. )

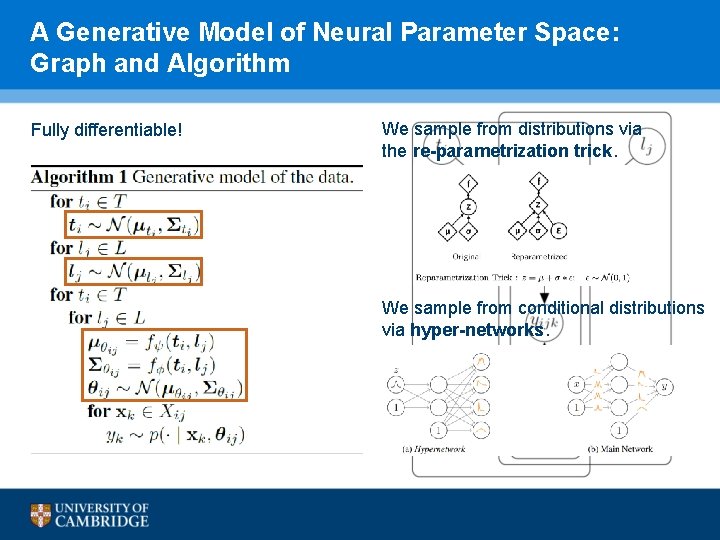

A Generative Model of Neural Parameter Space: Graph and Algorithm Fully differentiable! We sample from distributions via the re-parametrization trick. We sample from conditional distributions via hyper-networks.

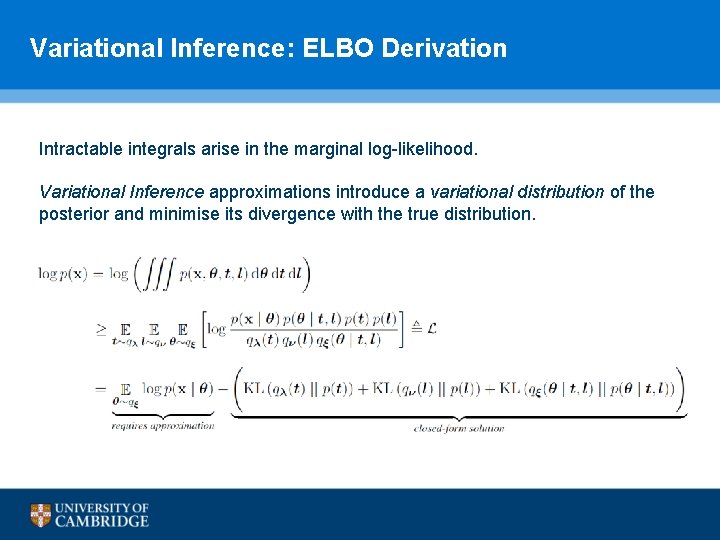

Variational Inference: ELBO Derivation Intractable integrals arise in the marginal log-likelihood. Variational Inference approximations introduce a variational distribution of the posterior and minimise its divergence with the true distribution.

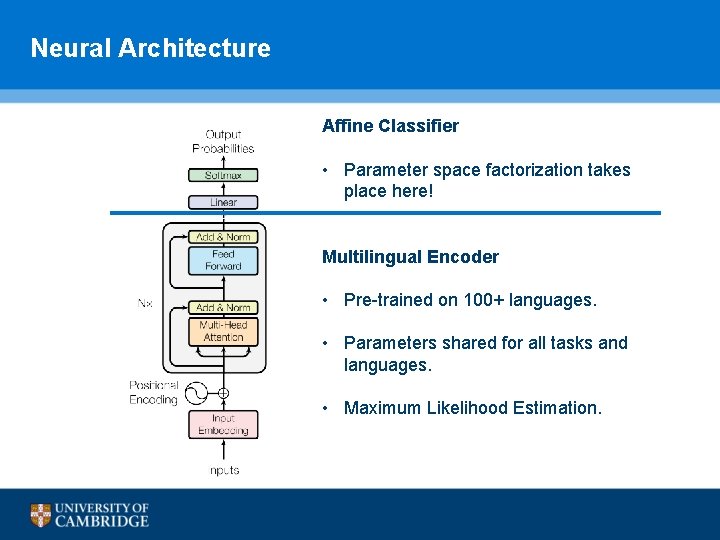

Neural Architecture Affine Classifier • Parameter space factorization takes place here! Multilingual Encoder • Pre-trained on 100+ languages. • Parameters shared for all tasks and languages. • Maximum Likelihood Estimation.

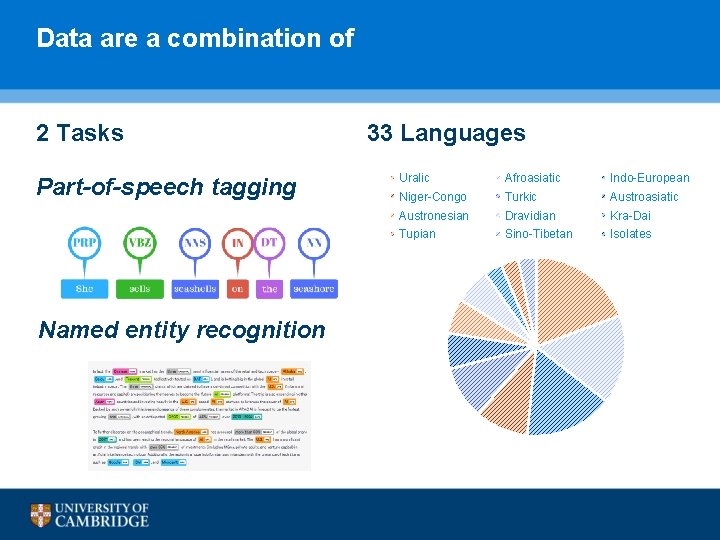

Data are a combination of 2 Tasks Part-of-speech tagging Named entity recognition 33 Languages Uralic Afroasiatic Indo-European Niger-Congo Turkic Austroasiatic Austronesian Dravidian Kra-Dai Tupian Sino-Tibetan Isolates

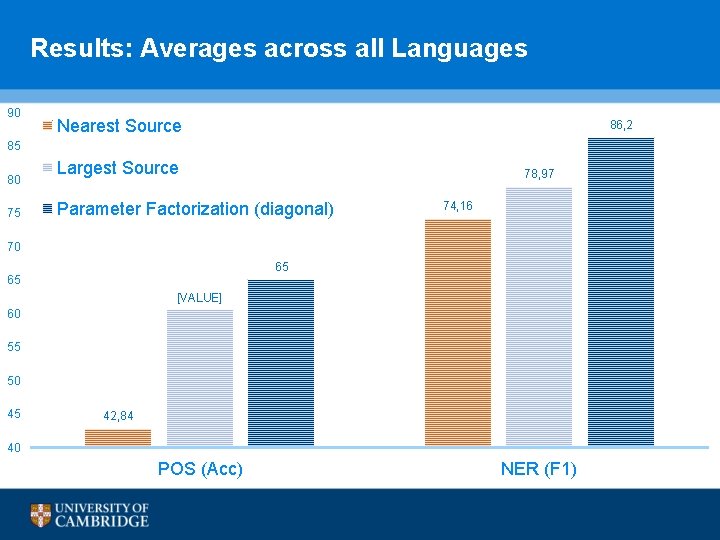

Baselines 2 baselines where the BERT encoder is shared across all languages and tasks, and each task-language combination has a private affine classifier. For a given target unseen combination, we select: • the classifier trained on the nearest source (based on typological, genealogical, and geographical similarity). • the classifier trained on the largest source, i. e. the language with most annotated examples (here it is English). Trade-off between abundance of data and reduction of the shift in the data

Results: Averages across all Languages 90 Nearest Source 86, 2 85 80 75 Largest Source 78, 97 Parameter Factorization (diagonal) 74, 16 70 65 65 [VALUE] 60 55 50 45 42, 84 40 POS (Acc) NER (F 1)

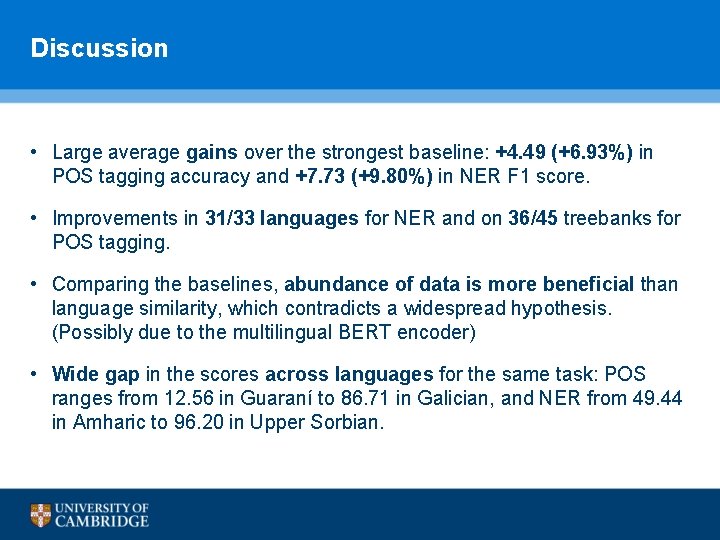

Discussion • Large average gains over the strongest baseline: +4. 49 (+6. 93%) in POS tagging accuracy and +7. 73 (+9. 80%) in NER F 1 score. • Improvements in 31/33 languages for NER and on 36/45 treebanks for POS tagging. • Comparing the baselines, abundance of data is more beneficial than language similarity, which contradicts a widespread hypothesis. (Possibly due to the multilingual BERT encoder) • Wide gap in the scores across languages for the same task: POS ranges from 12. 56 in Guaraní to 86. 71 in Galician, and NER from 49. 44 in Amharic to 96. 20 in Upper Sorbian.

Failing Loudly under High Uncertainty • Point estimate parameters tend to assign most of the probability mass to a single class, even in high-uncertainty settings like zero-shot learning. • Bayesian marginalization during predictive inference, instead, enables smoother predictions. • This is desirable, because in this case the model can “fail loudly”. • In particular, we propose to consider the entropy of the predictive distribution as a metric for confidence.

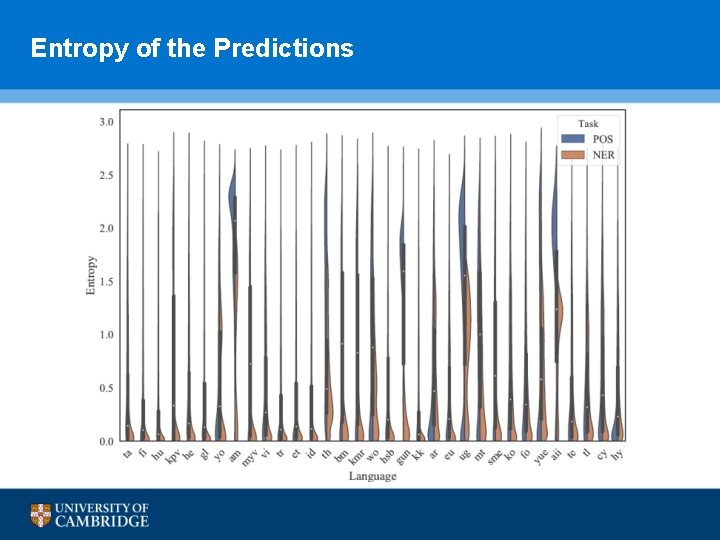

Entropy of the Predictions

1. Motivation and Background 2. Sample Efficiency via Inductive Biases 3. Generalisation via Modularity 4. Robustness via non-Bayes Criteria 5. Conclusions

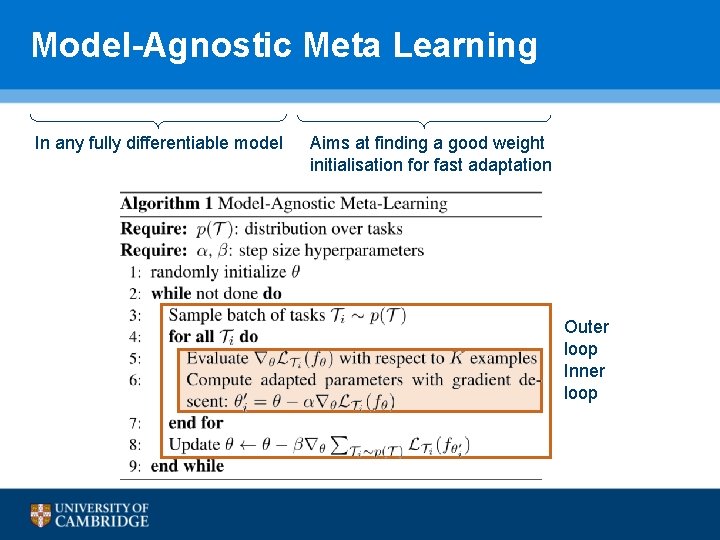

Model-Agnostic Meta Learning In any fully differentiable model Aims at finding a good weight initialisation for fast adaptation Outer loop Inner loop

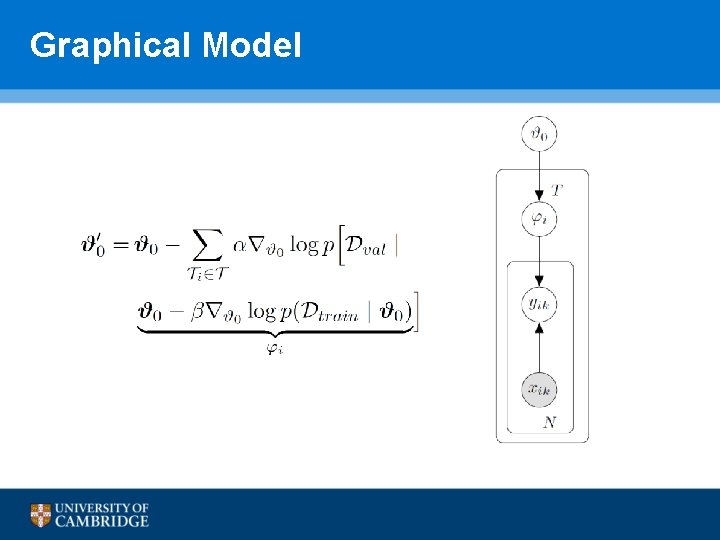

Graphical Model

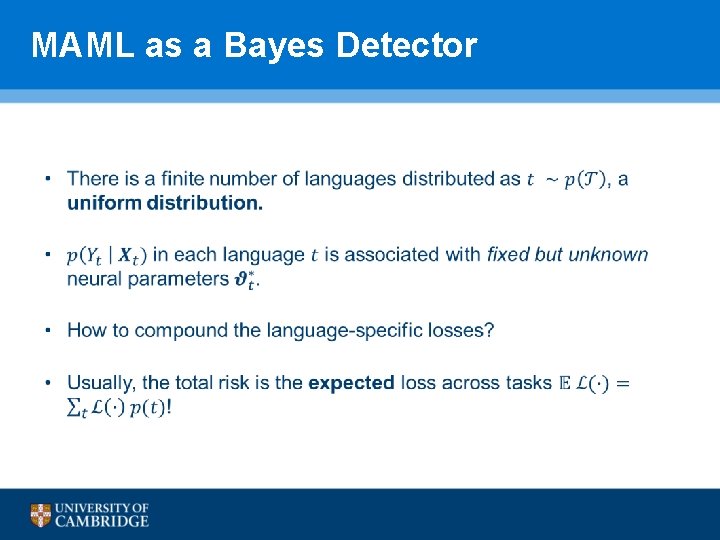

MAML as a Bayes Detector

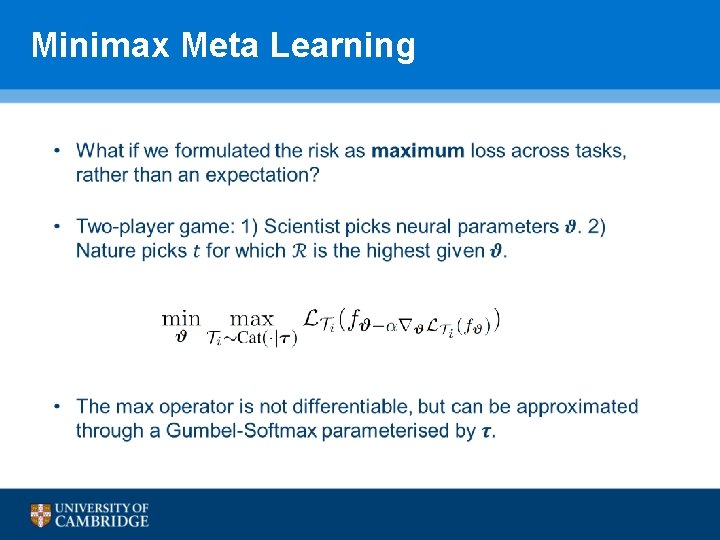

Minimax Meta Learning

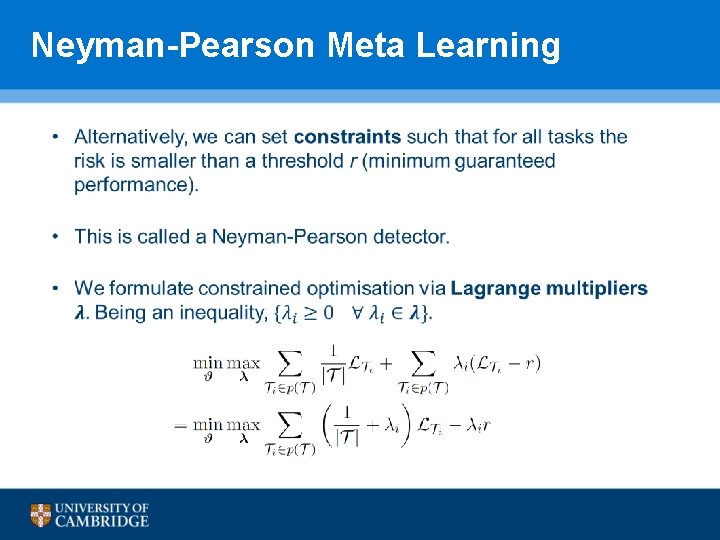

Neyman-Pearson Meta Learning

Solving Competitive Games

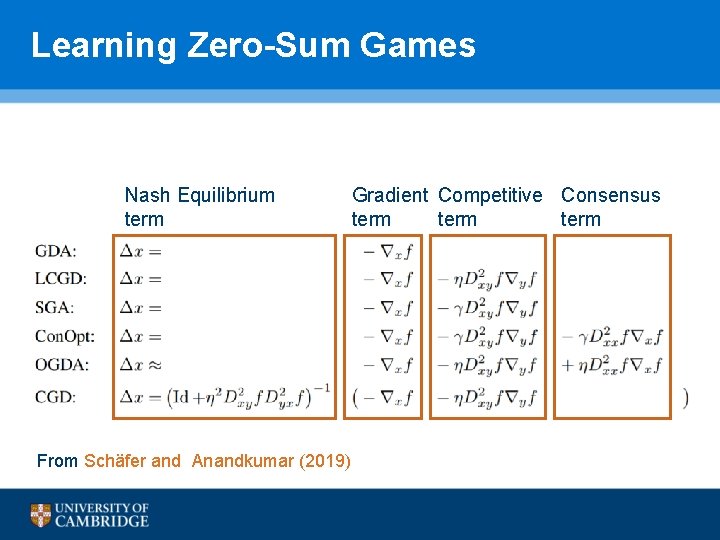

Learning Zero-Sum Games Nash Equilibrium term From Schäfer and Anandkumar (2019) Gradient Competitive Consensus term

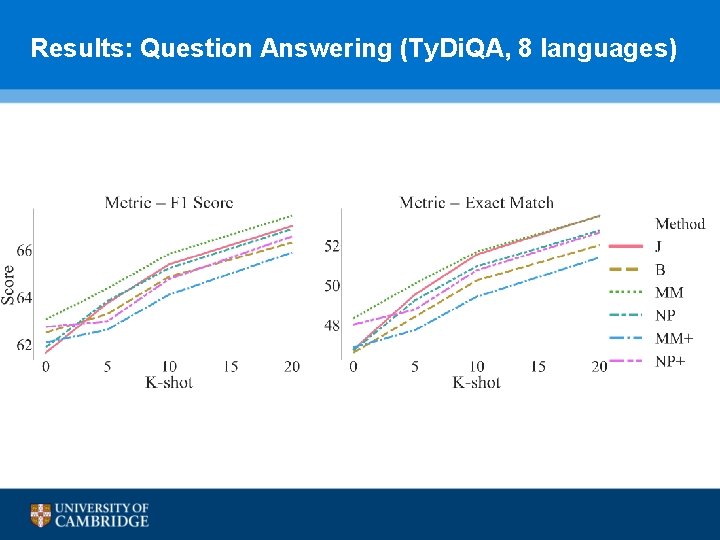

Results: Question Answering (Ty. Di. QA, 8 languages)

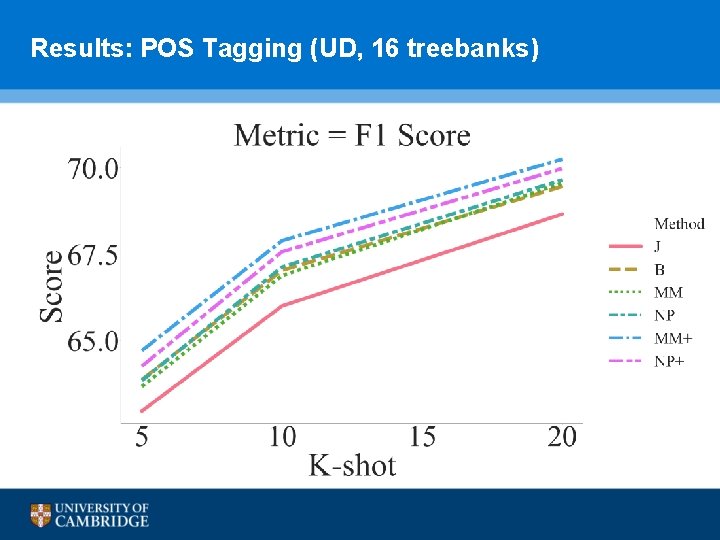

Results: POS Tagging (UD, 16 treebanks)

Discussion • Alternative criteria (Minimax and Neyman—Pearson) benefit crosslingual transfer to outlier languages. • Mixed results for competitive gradient descent, which does not always surpass naïve gradient ascent descent. • Multi-task learning outperforms vanilla MAML in QA, but not in POS tagging.

1. Motivation and Background 2. Sample Efficiency via Inductive Biases 3. Generalisation via Modularity 4. Robustness via non-Bayes Criteria 5. Conclusions

Take-home messages Main challenges for multilingual NLP: • Data paucity and cross-lingual variation Possible solutions include: • Constructing a universal prior over neural parameters that enables few-shot learning on unseen languages. • Factorizing the neural parameter space in order to transfer knowledge to new combinations of tasks and languages. • Adopting maximum-risk or constrained-risk objectives in non-i. i. d. settings (almost always in cross-lingual transfer).

Subscribe to SIGTYP! Mailing list and website: https: //sigtyp. github. io Next workshop (co-located with EMNLP 2021) in Mexico City, Mexico: https: //sigtyp. github. io/ws 20 21. html

Check out XCOPA! th ������ Cause ���������� en My eyes became red and puffy. I was sobbing. I was laughing. Cause New multilingual dataset on commonsense causal reasoning 11 typologically diverse languages (including Quechua and Haitian Creole) github. com/cambridgeltl/xcopa

References / Code • Ponti, Edoardo Maria, Ivan Vulić, Ryan Cotterell, Roi Reichart, and Anna Korhonen. 2019. Towards Zero-shot Language Modeling. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9 th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), pp. 2893 -2903. • Ponti, Edoardo Maria, Ivan Vulić, Ryan Cotterell, Marinela Parovic, Roi Reichart, and Anna Korhonen. 2020. Parameter Space Factorization for Zero-Shot Learning across Tasks and Languages. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics (to appear). Code: https: //github. com/cambridgeltl/parameter-factorization

Thank you for your attention! Questions? Kiitokset mielenkiinnostanne! Kysymyksiä?

- Slides: 46