Role of serpentine soil in divergent selection and

- Slides: 1

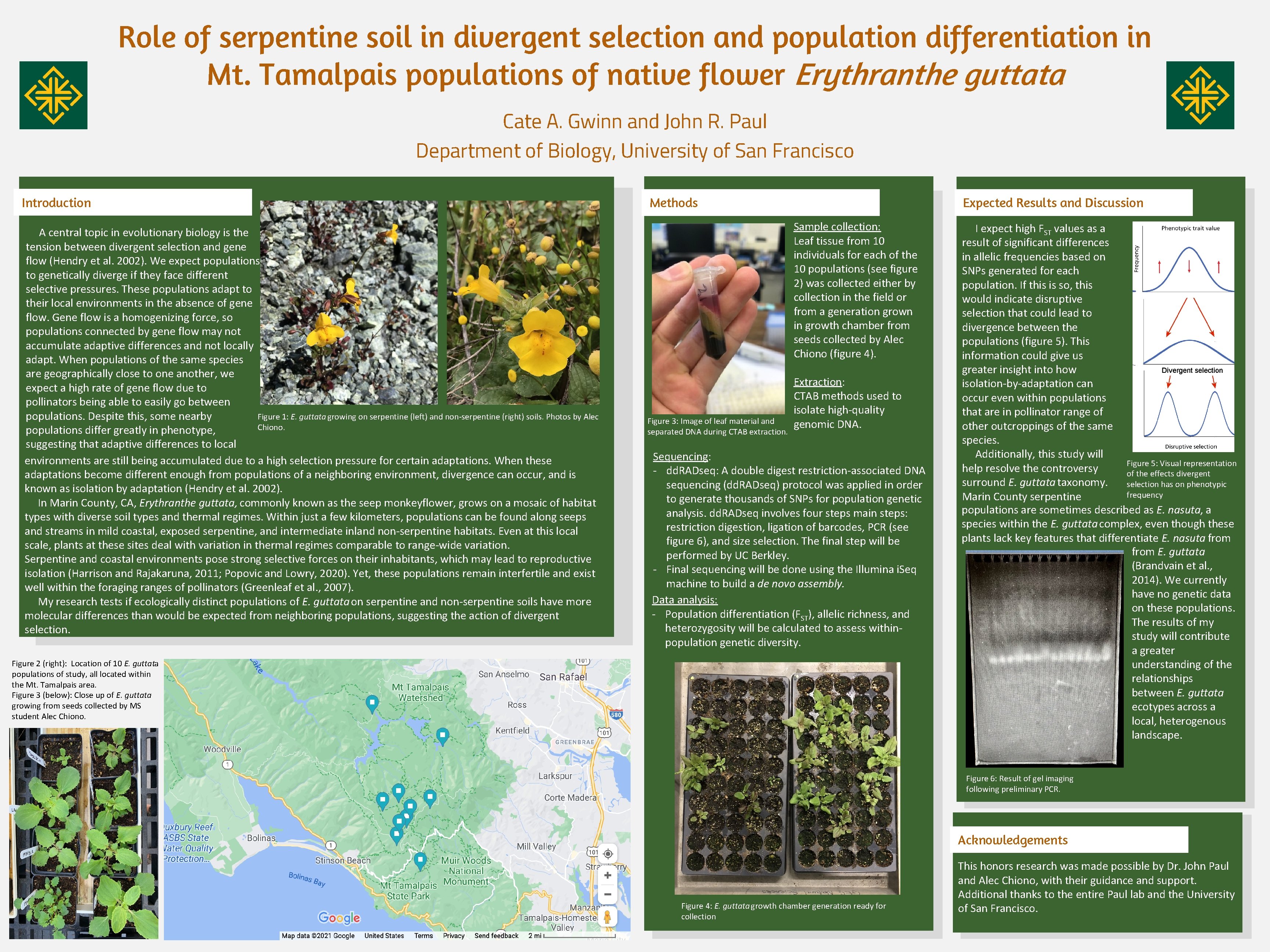

Role of serpentine soil in divergent selection and population differentiation in Mt. Tamalpais populations of native flower Erythranthe guttata Cate A. Gwinn and John R. Paul Department of Biology, University of San Francisco Introduction A central topic in evolutionary biology is the tension between divergent selection and gene flow (Hendry et al. 2002). We expect populations to genetically diverge if they face different selective pressures. These populations adapt to their local environments in the absence of gene flow. Gene flow is a homogenizing force, so populations connected by gene flow may not accumulate adaptive differences and not locally adapt. When populations of the same species are geographically close to one another, we expect a high rate of gene flow due to pollinators being able to easily go between Figure 1: E. guttata growing on serpentine (left) and non-serpentine (right) soils. Photos by Alec populations. Despite this, some nearby Chiono. populations differ greatly in phenotype, suggesting that adaptive differences to local environments are still being accumulated due to a high selection pressure for certain adaptations. When these adaptations become different enough from populations of a neighboring environment, divergence can occur, and is known as isolation by adaptation (Hendry et al. 2002). In Marin County, CA, Erythranthe guttata, commonly known as the seep monkeyflower, grows on a mosaic of habitat types with diverse soil types and thermal regimes. Within just a few kilometers, populations can be found along seeps and streams in mild coastal, exposed serpentine, and intermediate inland non-serpentine habitats. Even at this local scale, plants at these sites deal with variation in thermal regimes comparable to range-wide variation. Serpentine and coastal environments pose strong selective forces on their inhabitants, which may lead to reproductive isolation (Harrison and Rajakaruna, 2011; Popovic and Lowry, 2020). Yet, these populations remain interfertile and exist well within the foraging ranges of pollinators (Greenleaf et al. , 2007). My research tests if ecologically distinct populations of E. guttata on serpentine and non-serpentine soils have more molecular differences than would be expected from neighboring populations, suggesting the action of divergent selection. Methods Expected Results and Discussion Sample collection: Leaf tissue from 10 individuals for each of the 10 populations (see figure 2) was collected either by collection in the field or from a generation grown in growth chamber from seeds collected by Alec Chiono (figure 4). Figure 3: Image of leaf material and separated DNA during CTAB extraction. Extraction: CTAB methods used to isolate high-quality genomic DNA. Sequencing: - dd. RADseq: A double digest restriction-associated DNA sequencing (dd. RADseq) protocol was applied in order to generate thousands of SNPs for population genetic analysis. dd. RADseq involves four steps main steps: restriction digestion, ligation of barcodes, PCR (see figure 6), and size selection. The final step will be performed by UC Berkley. - Final sequencing will be done using the Illumina i. Seq machine to build a de novo assembly. Data analysis: - Population differentiation (FST), allelic richness, and heterozygosity will be calculated to assess withinpopulation genetic diversity. Figure 2 (right): Location of 10 E. guttata populations of study, all located within the Mt. Tamalpais area. Figure 3 (below): Close up of E. guttata growing from seeds collected by MS student Alec Chiono. I expect high FST values as a result of significant differences in allelic frequencies based on SNPs generated for each population. If this is so, this would indicate disruptive selection that could lead to divergence between the populations (figure 5). This information could give us greater insight into how isolation-by-adaptation can occur even within populations that are in pollinator range of other outcroppings of the same species. Additionally, this study will Figure 5: Visual representation help resolve the controversy of the effects divergent surround E. guttata taxonomy. selection has on phenotypic frequency Marin County serpentine populations are sometimes described as E. nasuta, a species within the E. guttata complex, even though these plants lack key features that differentiate E. nasuta from E. guttata (Brandvain et al. , 2014). We currently have no genetic data on these populations. The results of my study will contribute a greater understanding of the relationships between E. guttata ecotypes across a local, heterogenous landscape. Figure 6: Result of gel imaging following preliminary PCR. Acknowledgements Figure 4: E. guttata growth chamber generation ready for collection This honors research was made possible by Dr. John Paul and Alec Chiono, with their guidance and support. Additional thanks to the entire Paul lab and the University of San Francisco.