Rhyss Wide Sargasso Sea a postcolonial rewriting of

- Slides: 19

Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea: a post-colonial rewriting of Jane Eyre. Roberta Grandi Università della Valle d’Aosta

All begins with what seems almost a happy ending • Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre, published in 1847 • Jane is an orphan who, refused by the family of her aunt Mrs Reed, grows up in the (horrible) boarding school Lowood. She becomes a strong-willed and well educated young woman and is hired at the great mansion Thornfield Hall as the teacher of the young Adele, Mr Rochester’s natural daughter. • Though plain and poor, she conquers the heart of the moody Mr. Rochester who asks her to marry him in Chapter 23.

Almost… • The marriage (8: 10 -end) • http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=b. SWcj 9 M 1 w. LE • So, just on the point of getting married, Jane Eyre finds out that Mr. Rochester is already married, and that his wife is still alive. • But where is she?

The First Wife (Chapter 26) • • The madwoman in the attic: (start/2: 00) http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=M 4 li. BKw. BBKM • “Bertha Mason is mad; and she came of a mad family; idiots and maniacs through three generations. Her mother, the Creole, was both a madwoman and a drunkard!--as I found out after I had wed the daughter: for they were silent on family secrets before. ” • [. . . ] • “bound to a bad, mad, and embruted partner” • [. . . ] • “In the deep shade, at the farther end of the room, a figure ran backwards and forwards. What it was, whether beast or human being, one could not, at first sight, tell: it grovelled, seemingly, on all fours; it snatched and growled like some strange wild animal: but it was covered with clothing, and a quantity of dark, grizzled hair, wild as a mane, hid its head and face. ”

The Fire (Chapter 36) • And what happens to Bertha? • Bertha gives fire to the house and dies in the fire: (3: 40, 30/5: 10) • http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=M 4 li. BK w. BBKM

A Masterpiece of the Western Canon • • Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre has been considered a potentially subversive text because of its social and political position. Jane Eyre is a young woman, orphan and low born, who fights for emancipation and liberty. She wants to lead her life independently without any external control. Jane manages to provide herself with a lower middle class education, which enables her to be independent enough to earn a moderate income as a teacher. As a partner of Mr. Rochester, she rejects his despotism, characteristic of a male aristocrat of his era, and is reluctant to be his subordinate. She questions women’s position in society with regard to working rights and equal opportunities. She does not comply with the conventional norm which forces women to be restricted to the domestic sphere only. On the contrary she wants to take full advantage of her keen intellect, as a man in her position would normally do. Above all, she, a servant, marries her master, thus disturbing the social order. – From Nikos Karkavelias, Bertha must be kept silent, 2001, http: //www. qub. ac. uk/imperial/carib/Berthasilent. htm Chapter 23: • "I am no bird; and no net ensnares me; I am a free human being with an independent will, which I now exert to leave you. " [. . . ] • "My bride is here, " he said, again drawing me to him, "because my equal is here, and my likeness. Jane, will you marry me? "

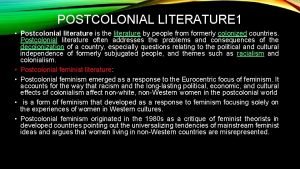

Feminist Critique and Post-colonial perspectives • • • From The Empire Writes Back, Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, Helen Tiffin, 2002 p. 172 “Women in many societies have been relegated to the position of “Other”, marginalized and, in a metaphorical sense, “colonized” [. . . ] They share with colonized races and peoples an intimate experience of the politics of oppression and repression, and like them they have been forced to articulate their experiences in the language of their oppressors. Women, like post-colonial peoples, have had to construct a language of their own when their only available “tools” are those of the “colonizer”. Remember Virginia Woolf? p. 173 “both feminist and post-colonial critics have reread the classic texts [. . . ] demonstrating clearly that a canon is produced by the intersection of a number of readings and reading assumptions legitimized in the privileging hierarchy of a “patriarchal” or “metropolitan” concept of “literature. [. . . ] to change the canon is to do more than change the legitimate texts. It is to change the condition of reading for all texts. ” p. 191 “Some contemporary critics have suggested that post-colonial is more than a body of texts produced within post-colonial societies, and that it is best conceived as a reading practice. ”

Feminist Critique and Post-colonial perspectives • The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination, published in 1979, examines Victorian literature from a feminist perspective. Authors Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar draw their title from Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre, in which Rochester's mad wife Bertha stays locked in the attic. • Bertha becomes the symbol of the female characters in English fiction, victims of society whose stories are forced to silence and told uniquely by male points of view. • At this stage, we are ready to try to reread Bertha’s story from a post-colonial perspective.

A Post-colonial “rereading” • The first question is: Who really is the madwoman in the attic? • And consequently: Was she really mad? – If so, was she mad from the beginning? Then why did Rochester marry her? – Or when did she become mad? – If not, why does he pretend she is? • Is Rochester a reliable narrator? • What really happened before? • What can we imagine of Bertha’s past life? • And finally, is Bertha her real name?

A Postcolonial Re-writing: Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea, 1966 • • • Jean Rhys was always troubled by the portrayal of the Caribbean Creole in Bronte's novel, and in her novel she tried to give voice to the silenced “Other”: Antoinette (Bertha) Cosway (Mason). Jean Rhys was born in Roseau, Dominica, West Indies. Her father, was a Welsh doctor and mother, Minna Williams was a third-generation Dominican Creole of Scottish ancestry. Rhys's Creole heritage, her experiences as a white Creole woman, both in the Caribbean and in England, influenced deeply her life and writing. Most of Dominica's people are of African descent. The slavery had ended in the island in 1834. “Set in Jamaica, Dominica, and England in the 1830 s, it explores that fluid historical era when black and white communities were adjusting to emancipation. ” – • From Moira Ferguson – Sending the Younger Son Across the Wide Sargasso Sea: the New Colonizer Arrives – 1993, p. 310 The story is set just after the emancipation of the slaves, in that uneasy time when racial relations in the Caribbean were at their most strained. Antoinette is descended from the plantation owners. She can be accepted neither by the negro community nor by the representatives of the colonial centre. As a white Creole she is nothing. The taint of racial impurity, coupled with the suspicion that she is mentally imbalanced bring about her inevitable downfall.

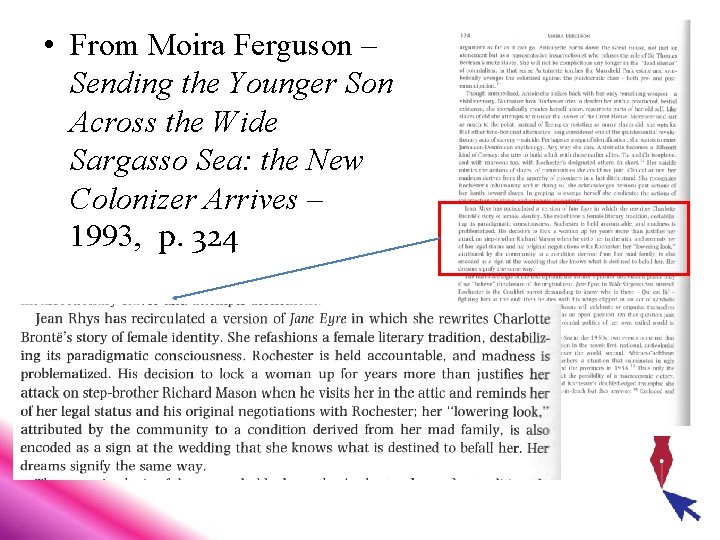

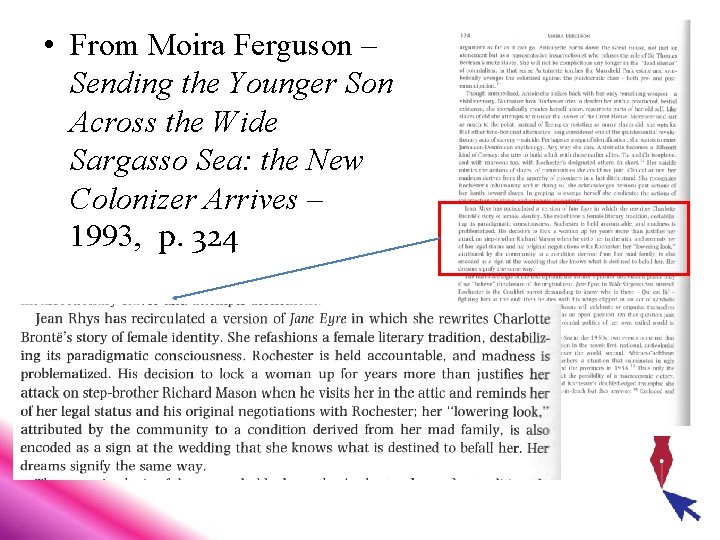

• From Moira Ferguson – Sending the Younger Son Across the Wide Sargasso Sea: the New Colonizer Arrives – 1993, p. 324

A Postcolonial Re-writing: Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea, 1966 • But is Antoinette’s the only silence? • The re-writing goes further and proposes different stories: the voices of the blacks, the “maroons”, the people who are entirely forgotten, erased in Brontë’s novel. • The character of Christophine, Bertha’s nurse and housekeeper, is important as a centre of alternative power and culture. • Other secondary characters, other “maroons” who have different priorities and interests: Tia, Daniel Cosway, Amelie.

A Postcolonial Re-writing: Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea, 1966 • Since writing has long been recognised as one of the strongest forms of cultural control, the rewriting of central narratives of colonial superiority is a liberating act for those from the former colonies. Rhys's text is a highly sophisticated example of coming to terms with European perceptions of the Caribbean creole community. • From Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea, 1966, Introduction by Angela Smith • p. vii “The Sargasso Sea lies between Europe and the West Indies and is difficult to navigate, like the human situations in the novel. ” • p. xiv “a sense of déjà vu [. . . ] The narrative is both familiar and unfamiliar, made strange by being seen mostly from the perspective of the woman who laughs, yells and acts but never speaks in Brontë’s novel. ” • p. xxii “The plot is like the Sargasso Sea, where weeds tangle together and resist being unravelled”

Post-Colonial Themes: from Colonization to Decolonization, from Slavery to Freedom • The novel describes a fundamental element of Caribbean cultural evolution: the passage from colonization and slavery to decolonization, independence and nationalist consciousness. See Stuart Hall, Negotiating Caribbean Identities, p. 282 • Jean Rhys writes a sort of family saga which acts as the representative of the fate of the Creole people in the Caribbean Islands • p. 313 “After 1834, when slaves were legally free, planters suicides were not uncommon. Legal compensation they received often had to be paid to insistent creditors, and sugar prices rocketed. ” • From Moira Ferguson – Sending the Younger Son Across the Wide Sargasso Sea : the New Colonizer Arrives – 1993 • p. xxiii “The unspeakable story of human beings claiming, without pity, to own each other, in slavery, marriage or parenthood, is the revenant that haunts the novel. ” From Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea, 1966, Introduction by Angela Smith • p. 129 “mad Creole heiress in the early nineteenth century, whose dowries were only an additional burden to them: products of an inbred, decadent, expatriate society, resented by the recently freed slaves whose superstitions they shared, they (p. 130) languished uneasily in the oppressive beauty of their tropical surroundings, ripe for exploitation. ” From Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea, 1966, Introduction by Francis Wyndham

Post-Colonial Themes: Caribbean Diaspora • p. 282 “If the search for identity always involves a search for origins, it is impossible to locate in the Caribbean an origin for its peoples. ” • p. 283 “The melting-pot of the British islands produced everywhere you look a different combination of genetic features and factors and in each island elements of other ethnic cultures are present. ” – Stuart Hall, Negotiating Caribbean Identities • African inheritance, French, Spanish. • p. 40 “Long, sad, dark alien eyes. Creole of pure English descent she may be, but they are not English or European either. ” – From Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea, 1966

Post-Colonial Themes: Power • The novel describes the island in a critical moment in which power was being negotiated (or, better, contested) between the new colonizers and the liberated slaves (who considered themselves the legitimate inhabitants of the island). • The new colonizer: Rochester • p. Xii “With the confidence of his belied in his own cultural and racial superiority he has stolen her spirit and driven her mad” From Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea, 1966, Introduction by Angela Smith • The liberated slave: Christophine • p. 103 “No police here, -she said- No chain gang, no tread machine, no dark jail either. This is free country and I am a free woman. ” – From Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea, 1966 • p. 319 “A powerful member of the community, denounces the political overlord; she exorcises his presence from the community. ” – From Moira Ferguson – Sending the Younger Son Across the Wide Sargasso Sea: the New Colonizer Arrives – 1993 • (9: 20 -10: 00) http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=FJd. UMlgh. VE&feature=related

Post-Colonial Themes: Language • p. Xi “ this isle is full of voices, speaking different languages and different versions of English and French. Some of the words, such as obeah and zombi, cannot adequately be translated into English. The culture of most of the islands’ inhabitants is oral rather than literate. ” • From Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea, 1966, Introduction by Angela Smith • • • p. 40 “debased French patois they use in this island. ” p. 104 “She began to mutter to herself. Not in patois. I knew the sound of patois now. She’s as mad as the other I thought. ” P. 104 “Read and write I don’t know. Other things I know. ” • From Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea, 1966 • p. 7 “Language becomes the medium through which a hierarchical structure of power is perpetuated. [. . . ] Such power is rejected in the emergence of an effective post-colonial voice. [. . . ] the discussion of post-colonial writing [. . . ] is largely a discussion of the process by which the language, with its power, and the writing, with its signification of authority, has been wrested from the dominant European culture. ” • • From The Empire Writes Back, Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, Helen Tiffin, 2002 p. 8 English (Rochester)/ english (Antoinette - Christophine)/patois From The Empire Writes Back, Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, Helen Tiffin, 2002 (4: 00 -5: 00) http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=lah. Swz. OAvm. Q&feature=related • • • p. 45: Creole continuum (overlapping dialects and variations of english) • From The Empire Writes Back, Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, Helen Tiffin, 2002

Post-Colonial Themes: Identity • Antoinette/Bertha: no race, no social class, no language, no culture, no property, no roots (orphan), no name • • Race: p. 64 “a song about a white cockroach. That’s me. That’s what they call of us who were here before their own people in Africa sold them to the slave traders. And I’ve heard English women call us white niggers. So between you I often wonder who I am and where is my country and where do I belong and why was I ever born at all. ” • From Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea, 1966 • (7: 50 -8: 45) http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=lah. Swz. OAvm. Q&feature=related • • Social class: p. 316 “She is, after all, a white creole who sometimes empathizes with ex-slaves. ” • • • From Moira Ferguson – Sending the Younger Son Across the Wide Sargasso Sea: the New Colonizer Arrives – 1993 Culture: p. 58 “I felt very little tenderness for her, she was a stranger to me, a stranger who did not think or feel as I did. ” • • Name: p. 94 “Bertha is not my name. You are trying to make me into someone else, calling me by another name. I know, that’s obeah too. ” • From Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea, 1966 p. 317 “Antoinette belongs to no one and belongs nowhere. ” • From Moira Ferguson – Sending the Younger Son Across the Wide Sargasso Sea: the New Colonizer Arrives – 1993

An intertextual Element: the Fire • Annette Cosway (Antoinette’s mother) is driven crazy by the fire of Coulibri estate. • From freedom (freed slaves) to fire to madness • p. 315 “Burnt estates became familiar signifiers of historical resistance and revenge, of a celebratory post-emancipation landscape. ” – From Moira Ferguson – Sending the Younger Son Across the Wide Sargasso Sea: the New Colonizer Arrives – 1993 • Antoinette gives fire to Thornfield Hall in order to be set free. • From madness to fire to freedom. • (12: 00 -end) http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=d 2 A 3 Y 3 uno 5 s&feature=rela ted

Across the wide sargasso sea

Across the wide sargasso sea Christophine in wide sargasso sea

Christophine in wide sargasso sea Wide sargasso sea cliff notes

Wide sargasso sea cliff notes Extreme wide shot also known as

Extreme wide shot also known as Dom

Dom Postcolonial theory and literature

Postcolonial theory and literature Neocolonialism

Neocolonialism Postcolonial criticism ppt

Postcolonial criticism ppt Ethnic studies and postcolonial criticism

Ethnic studies and postcolonial criticism Paul gilroy postcolonial theory

Paul gilroy postcolonial theory Key terms in postcolonial theory

Key terms in postcolonial theory Moses crossing the red sea map

Moses crossing the red sea map Jane sells pillows

Jane sells pillows Rewriting radical expressions

Rewriting radical expressions Rewriting universal conditional statement examples

Rewriting universal conditional statement examples Servlet url rewriting

Servlet url rewriting Rewriting a universal existential statement example

Rewriting a universal existential statement example Intercept form of a parabola

Intercept form of a parabola Rewriting history

Rewriting history Rewrite cinderella story

Rewrite cinderella story