Rheumatic diseases classification Common rheumatic diseases Rafa Wojciechowski

- Slides: 52

Rheumatic diseases – classification Common rheumatic diseases Rafał Wojciechowski, MD Senior assistant Clinical Department of Rheumatology and Connective Tisssue Diseases

• Rheumatic diseases are a group of over 300 clinical units • common feature of most rheumatic diseases are chronic inflammatory process involving the connective tissue • autoimmune reactions are the cause of the inflammation

Division of rheumatic diseases based on American Rheumatism Association classification • 1. connective tissue diseases – rheumatoid arthritis (RA) – juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) – systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) – antiphospholipid syndrome – scleroderma – polymyositis and dermatomyositis (PM and DM) – vasculitis with necrosis – Sjogren's syndrome – overlap syndromes – mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) – undifferentiated connective tissue disease

Division of rheumatic diseases based on American Rheumatism Association classification • other connective tissue diseases: – polymyalgia rheumatica – inflammation of adipose tissue – erythema nodosum – recurrent inflammation of cartilage – eosinophilic fasciitis – Still's disease in adults

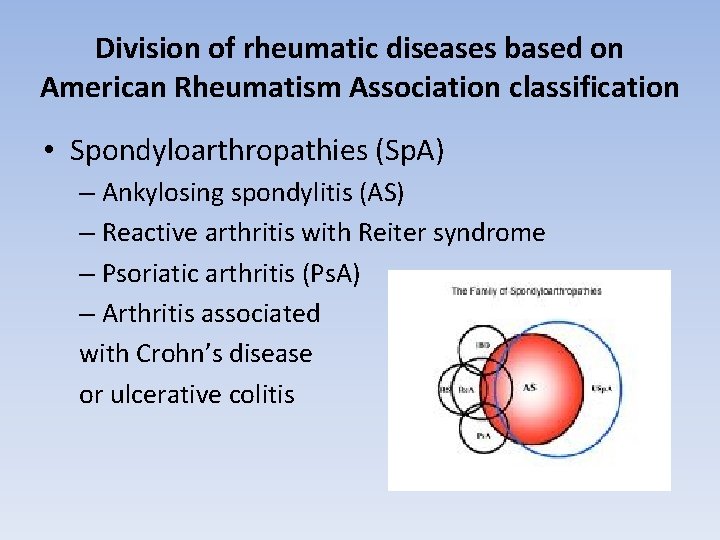

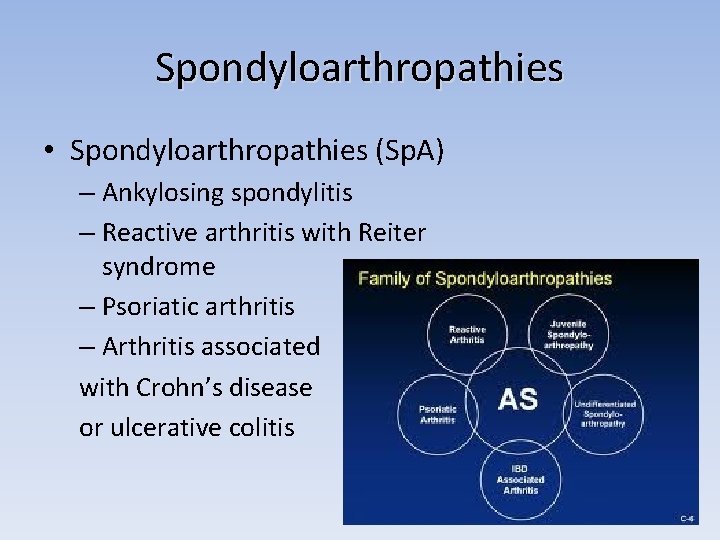

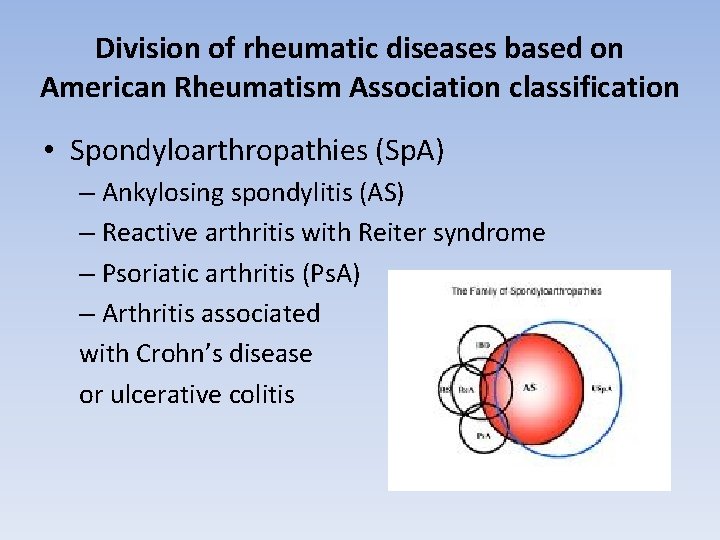

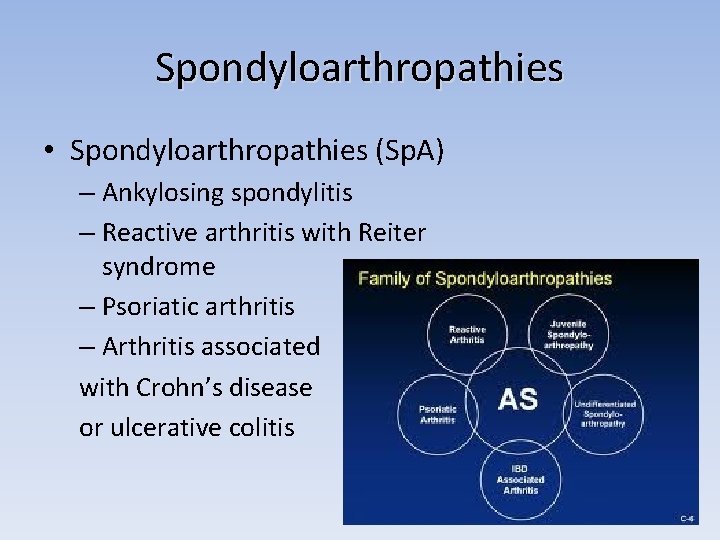

Division of rheumatic diseases based on American Rheumatism Association classification • Spondyloarthropathies (Sp. A) – Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) – Reactive arthritis with Reiter syndrome – Psoriatic arthritis (Ps. A) – Arthritis associated with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis

Division of rheumatic diseases based on American Rheumatism Association classification • Osteoarthritis (OA) • arthritis associated with infection – bacterial, viral, fungal, parasitic infection • reactive inflammation • arthritis associated with metabolic diseases and endocrine diseases – inflammation associated with the presence of crystals such as gout

Division of rheumatic diseases based on American Rheumatism Association classification • disease of bone and cartilage – Osteoporosis – Osteomalacia – hypertrophic osteoarthropathy – idiopathic generalized hyperostosis = Forestier's disease – Paget's disease

Division of rheumatic diseases based on American Rheumatism Association classification • changes in non-joint - the soft tissue rheumatism – fibromyalgia pain syndromes ( like f. ex. : neck pain, cervicoshoulder pain) – enthesopathy – bursitis – Etc.

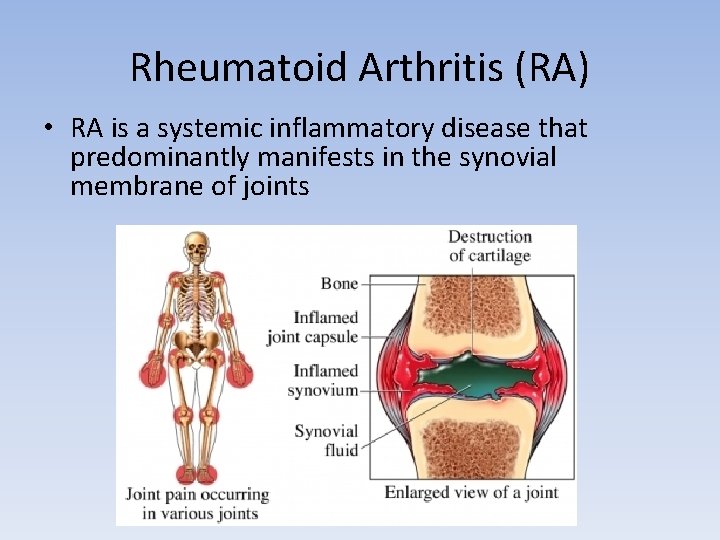

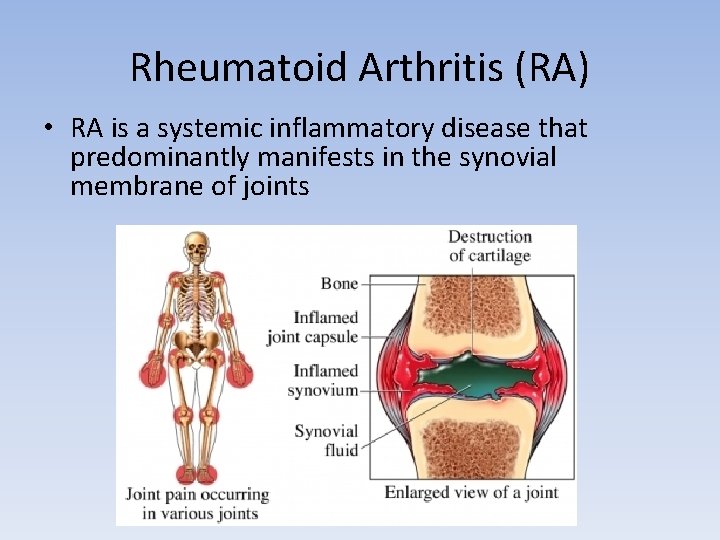

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) • RA is a systemic inflammatory disease that predominantly manifests in the synovial membrane of joints

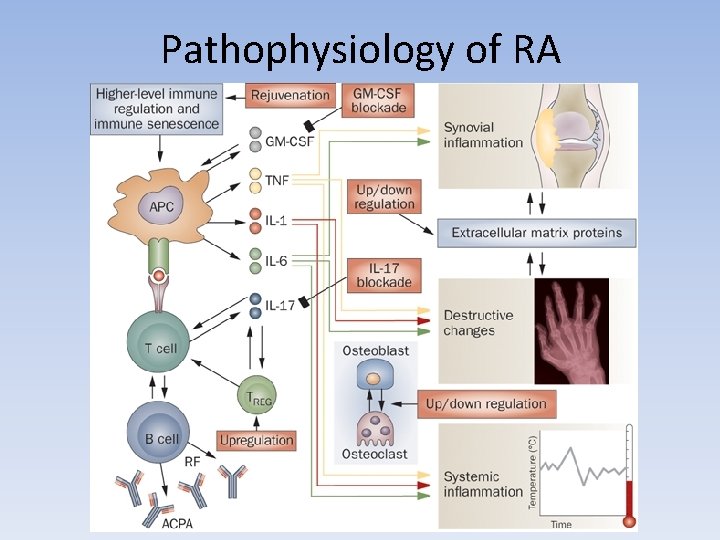

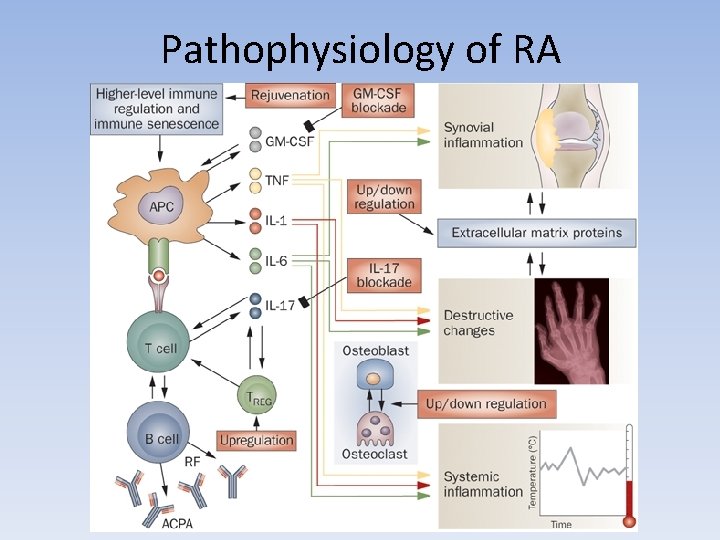

Pathophysiology of RA • The most widely accepted hypothesis is the disease is triggered in a genetically susceptible individual by an unknown antigen. • The initial stages consist of T-cell infilitration into the synovial membrane. The early inflammatory response results in reqruitment of other cells to the synovium which is facilitated by upregulation of adhesion molecules and proliferation of new blood vessels. • T-cells activate macrophages to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF, IL-1, IFN). T-cells activate B-cells to produce rheumatoid factor. • The natural anti-inflammatory and regulatory mechanisms are overwhelmed resulting in a runaway inflammatory processs leading to the destruction of cartilage and bone.

Pathophysiology of RA

RA - Presentation • Identifying Data: Peak incidence between 30 -50 years old (can occur at any age). Prevelence of 1% in general population. Female : Male = 2. 5 : 1 • Onset: Usually an insidious onset (70%) of joint pain and swelling in an oligoarticular pattern evolving to a polyarthritis. Occasionally can see a subacute presentation (20%), an acute presentation (10%), or a preceding palindromic presentation. Morning stiffness > 60 minutes, gelling phenomenon, decreased energy and poor sleep, weight gain, rare appetite loss and weight loss when severe

RA - Presentation • Progression: as the disease progresses more joints become continously involved leading to the symmetrical polyarthritis. With continued inflammation damage to joints may result with the initial findings of erosions of plain radiographs. Almost 90% joints ultimately affected in a given patient are involved during the first year of disease. By 4 months of symptoms, 50% of patients will have erosions on MRI. By 3 years, 70 -90% of patients demonstrate erosions on X-ray. • Constitutional Features: malaise, anorexia and weight loss • Functional Status: reduced functional status and difficulties with activities of daily living, loss of employment

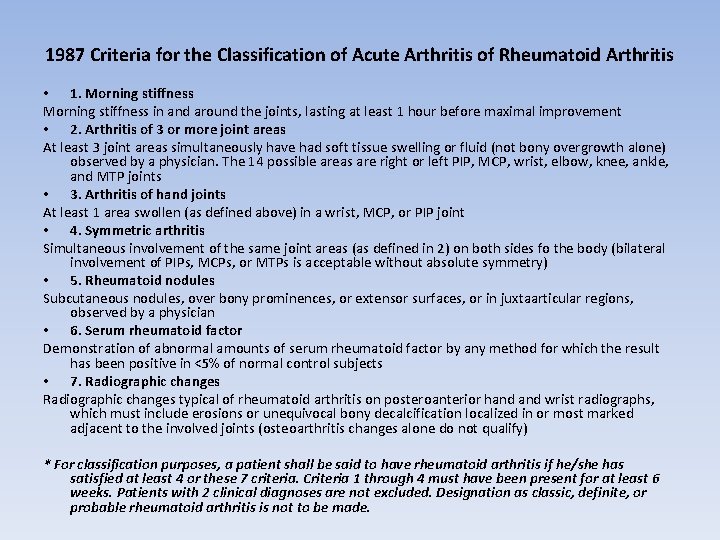

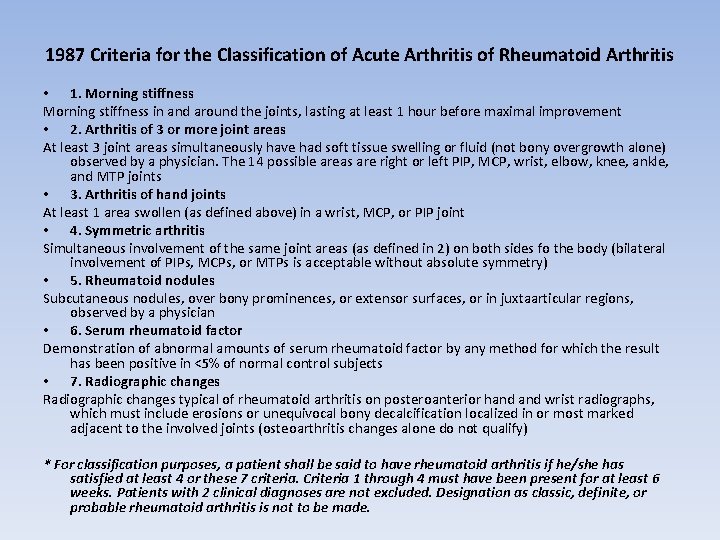

1987 Criteria for the Classification of Acute Arthritis of Rheumatoid Arthritis • 1. Morning stiffness in and around the joints, lasting at least 1 hour before maximal improvement • 2. Arthritis of 3 or more joint areas At least 3 joint areas simultaneously have had soft tissue swelling or fluid (not bony overgrowth alone) observed by a physician. The 14 possible areas are right or left PIP, MCP, wrist, elbow, knee, ankle, and MTP joints • 3. Arthritis of hand joints At least 1 area swollen (as defined above) in a wrist, MCP, or PIP joint • 4. Symmetric arthritis Simultaneous involvement of the same joint areas (as defined in 2) on both sides fo the body (bilateral involvement of PIPs, MCPs, or MTPs is acceptable without absolute symmetry) • 5. Rheumatoid nodules Subcutaneous nodules, over bony prominences, or extensor surfaces, or in juxtaarticular regions, observed by a physician • 6. Serum rheumatoid factor Demonstration of abnormal amounts of serum rheumatoid factor by any method for which the result has been positive in <5% of normal control subjects • 7. Radiographic changes typical of rheumatoid arthritis on posteroanterior hand wrist radiographs, which must include erosions or unequivocal bony decalcification localized in or most marked adjacent to the involved joints (osteoarthritis changes alone do not qualify) * For classification purposes, a patient shall be said to have rheumatoid arthritis if he/she has satisfied at least 4 or these 7 criteria. Criteria 1 through 4 must have been present for at least 6 weeks. Patients with 2 clinical diagnoses are not excluded. Designation as classic, definite, or probable rheumatoid arthritis is not to be made.

Hands with joint swelling and damage from rheumatoid arthritis

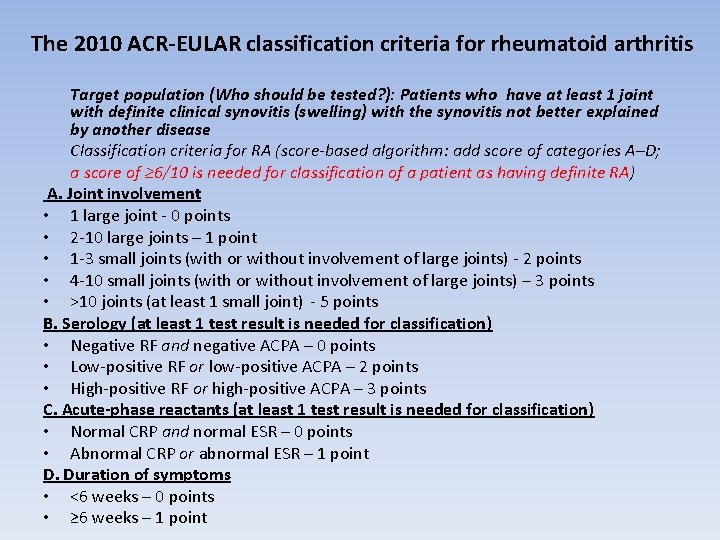

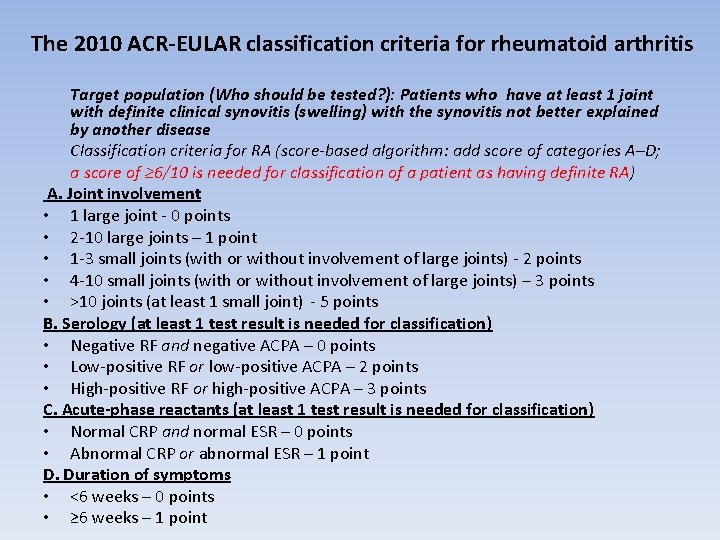

The 2010 ACR-EULAR classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis Target population (Who should be tested? ): Patients who have at least 1 joint with definite clinical synovitis (swelling) with the synovitis not better explained by another disease Classification criteria for RA (score-based algorithm: add score of categories A–D; a score of ≥ 6/10 is needed for classification of a patient as having definite RA) A. Joint involvement • 1 large joint - 0 points • 2 -10 large joints – 1 point • 1 -3 small joints (with or without involvement of large joints) - 2 points • 4 -10 small joints (with or without involvement of large joints) – 3 points • >10 joints (at least 1 small joint) - 5 points B. Serology (at least 1 test result is needed for classification) • Negative RF and negative ACPA – 0 points • Low-positive RF or low-positive ACPA – 2 points • High-positive RF or high-positive ACPA – 3 points C. Acute-phase reactants (at least 1 test result is needed for classification) • Normal CRP and normal ESR – 0 points • Abnormal CRP or abnormal ESR – 1 point D. Duration of symptoms • <6 weeks – 0 points • ≥ 6 weeks – 1 point

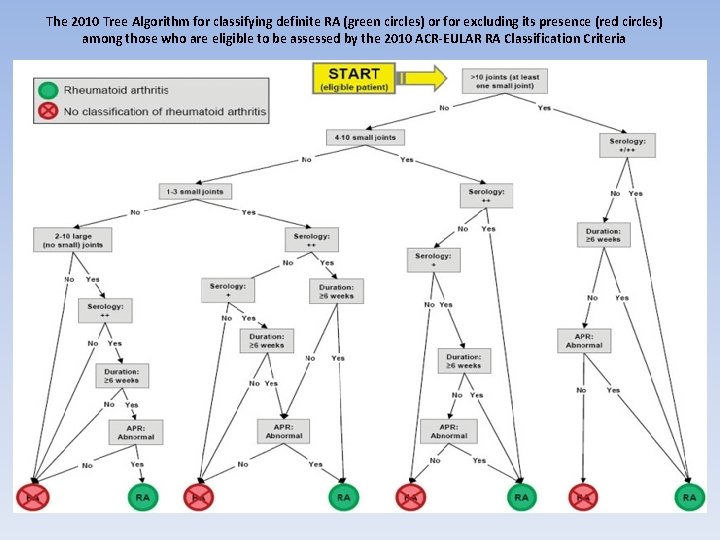

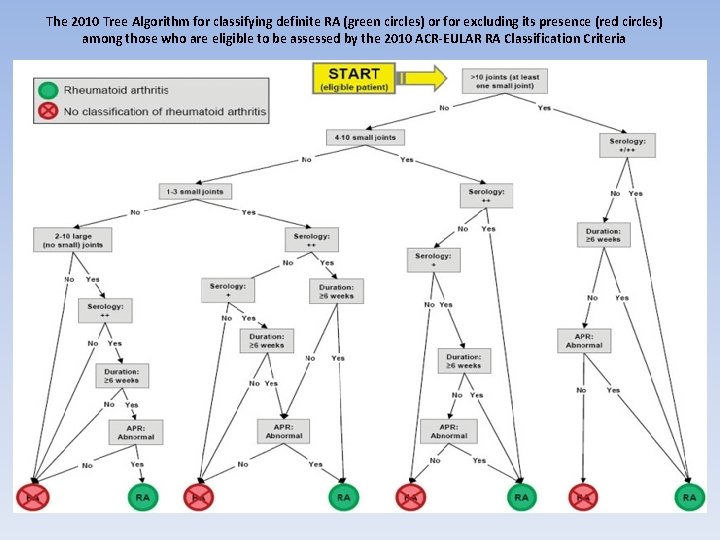

The 2010 Tree Algorithm for classifying definite RA (green circles) or for excluding its presence (red circles) among those who are eligible to be assessed by the 2010 ACR-EULAR RA Classification Criteria

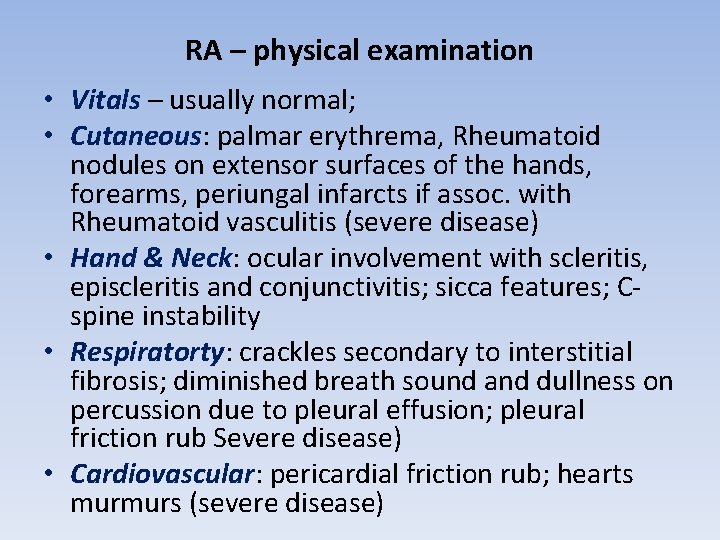

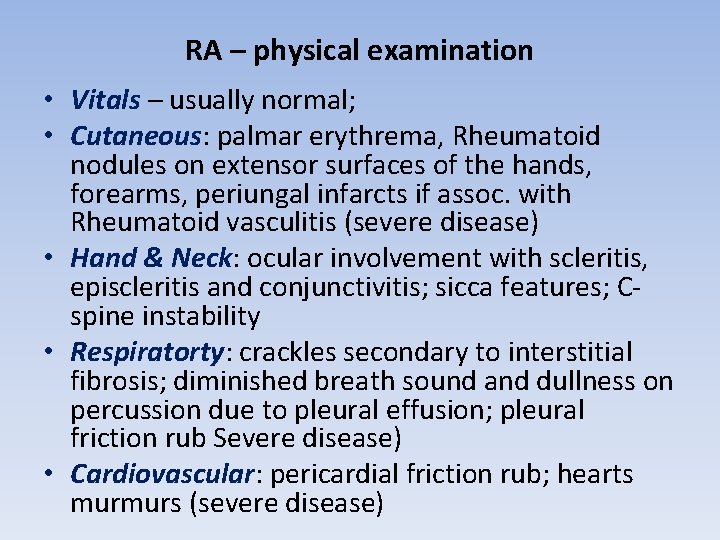

RA – physical examination • Vitals – usually normal; • Cutaneous: palmar erythrema, Rheumatoid nodules on extensor surfaces of the hands, forearms, periungal infarcts if assoc. with Rheumatoid vasculitis (severe disease) • Hand & Neck: ocular involvement with scleritis, episcleritis and conjunctivitis; sicca features; Cspine instability • Respiratorty: crackles secondary to interstitial fibrosis; diminished breath sound and dullness on percussion due to pleural effusion; pleural friction rub Severe disease) • Cardiovascular: pericardial friction rub; hearts murmurs (severe disease)

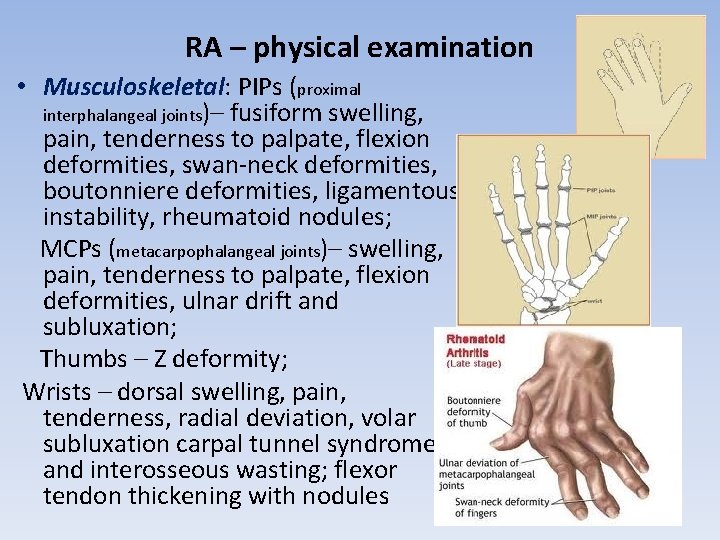

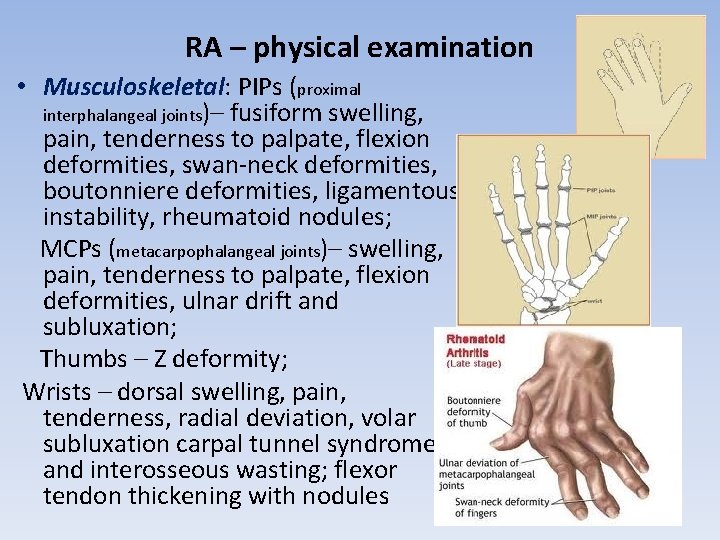

RA – physical examination • Musculoskeletal: PIPs (proximal interphalangeal joints)– fusiform swelling, pain, tenderness to palpate, flexion deformities, swan-neck deformities, boutonniere deformities, ligamentous instability, rheumatoid nodules; MCPs (metacarpophalangeal joints)– swelling, pain, tenderness to palpate, flexion deformities, ulnar drift and subluxation; Thumbs – Z deformity; Wrists – dorsal swelling, pain, tenderness, radial deviation, volar subluxation carpal tunnel syndrome and interosseous wasting; flexor tendon thickening with nodules

RA – physical examination • Musculoskeletal: Elbow and shoulder involvement; Knee and Hip involvement; Foot – hindfoot valgus deformity and forefoot abduction (pronated); MTP – inflammation with loss visibility of the extensor tendons and splayed toes lifted off the ground. Subluxation of MTPs with distal migration of the fat pad and callous formation • Neurologic: neuropathy – polyneuropathy or mononeuritis multiplex; upper motor neuron signs with cervical spine involvement causing spinal cord compromise

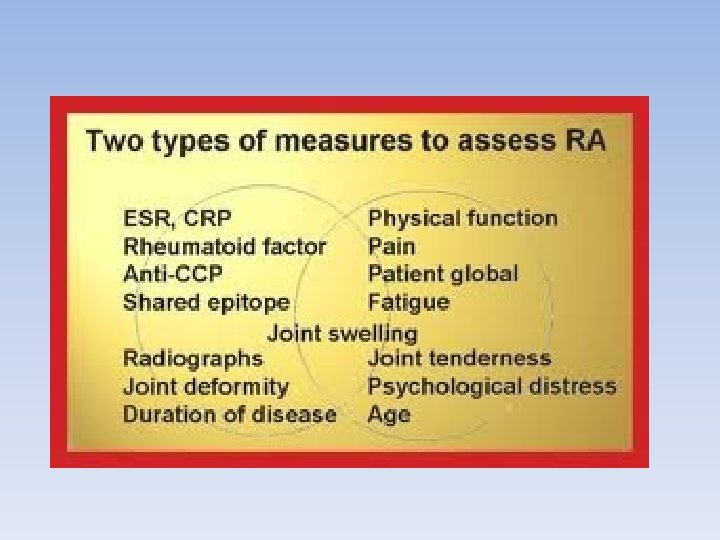

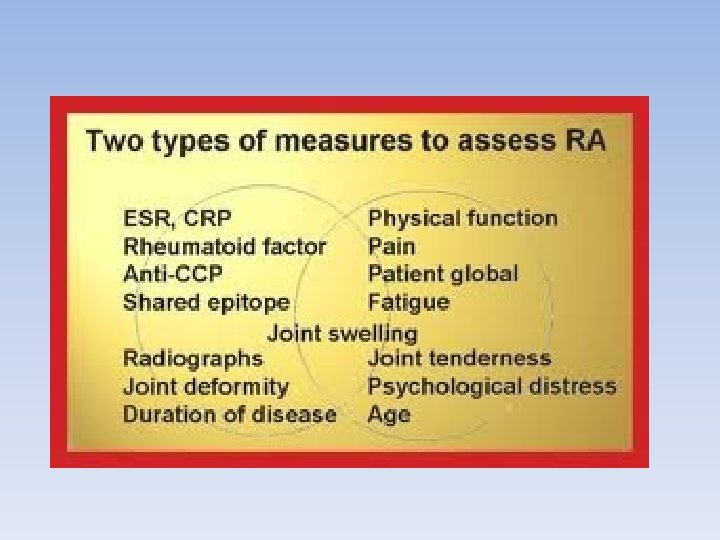

RA - Investigations • CBS: anaemia of chronic inflammation or secondary to blood loss (NSAIDs) or to bone marrow supression; leukopenia with Felt’s or secondary to medications; thromocytosis with inflammation or thromobocytopenia secondary to Felty’s or medications • ESR/CRP: usually elevated however rarely may be normal • RF: early disease (30 -50%); established disease (7085%); • Anti-CCP: higly specific for RA (95%) but poor sensitivity • ANA: present in 25% patients

RA - Investigations • Plain Radiographs: – Bones: periarticular osteopenia, periarticular cysts if rheumatoid robustus; – Joints: uniform joint space narrowing and marginal erosions; erliest erosions in 2’nd and 3’rd metacarpal heads, ulnear styloid, medial aspect of first metacarpal head – Alignment: demage to joints results in melalignment: PIPs – contractures, swan-neck deformities, boutonniere deformities; MCPs: subluxation and ulnar deviation; Thumbs: Z deformity; Wrists: radial deviation and volar subluxation; C-Spine: A-A instability (vertiacal, horizontal and lateral); MTPs: subluxation, angulation deformities; – Soft Tissue: periarticular swelling and evidence of joint effusions;

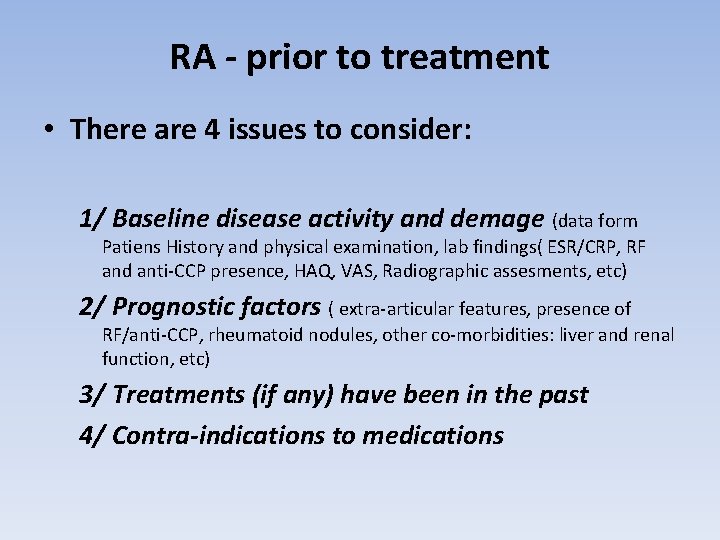

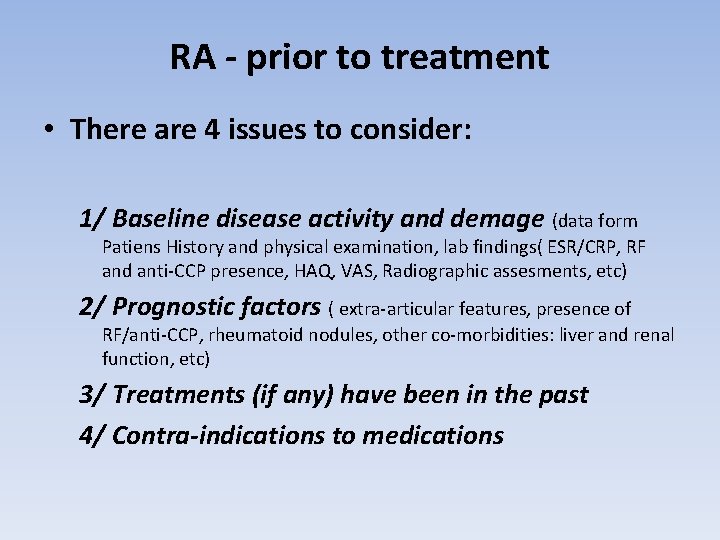

RA - prior to treatment • There are 4 issues to consider: 1/ Baseline disease activity and demage (data form Patiens History and physical examination, lab findings( ESR/CRP, RF and anti-CCP presence, HAQ, VAS, Radiographic assesments, etc) 2/ Prognostic factors ( extra-articular features, presence of RF/anti-CCP, rheumatoid nodules, other co-morbidities: liver and renal function, etc) 3/ Treatments (if any) have been in the past 4/ Contra-indications to medications

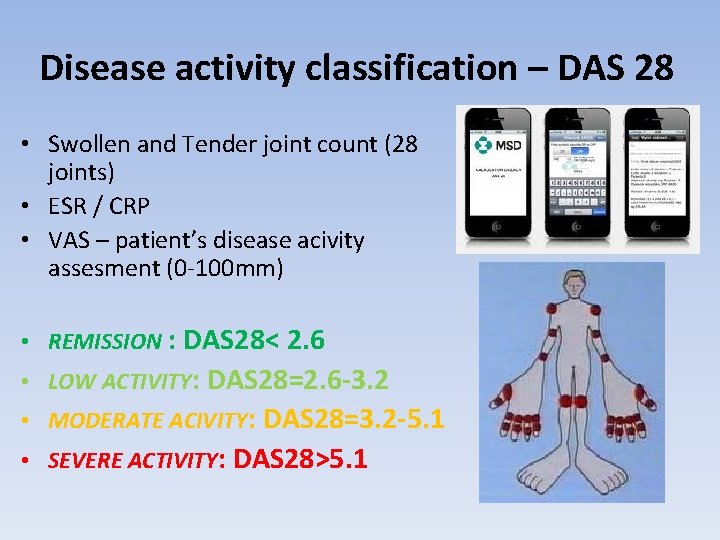

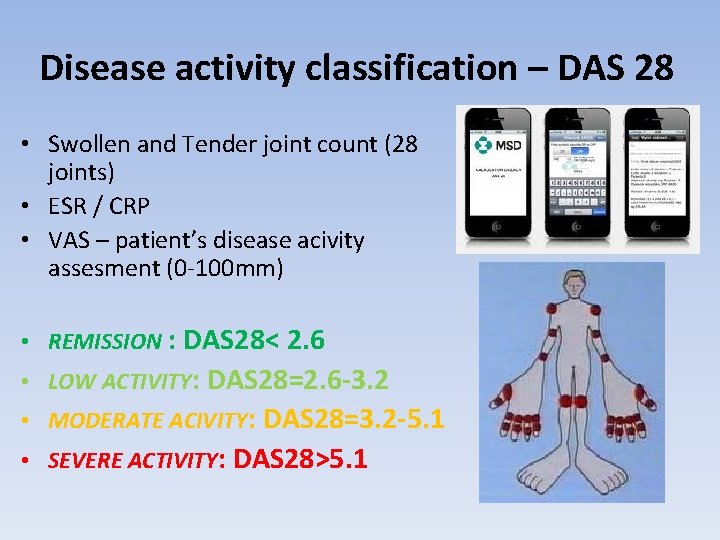

Disease activity classification – DAS 28 • Swollen and Tender joint count (28 joints) • ESR / CRP • VAS – patient’s disease acivity assesment (0 -100 mm) • REMISSION : DAS 28< 2. 6 • LOW ACTIVITY: DAS 28=2. 6 -3. 2 • MODERATE ACIVITY: DAS 28=3. 2 -5. 1 • SEVERE ACTIVITY: DAS 28>5. 1

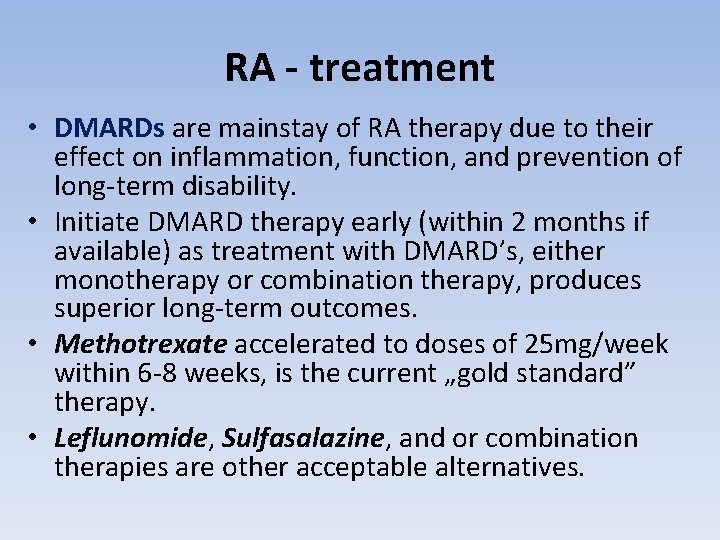

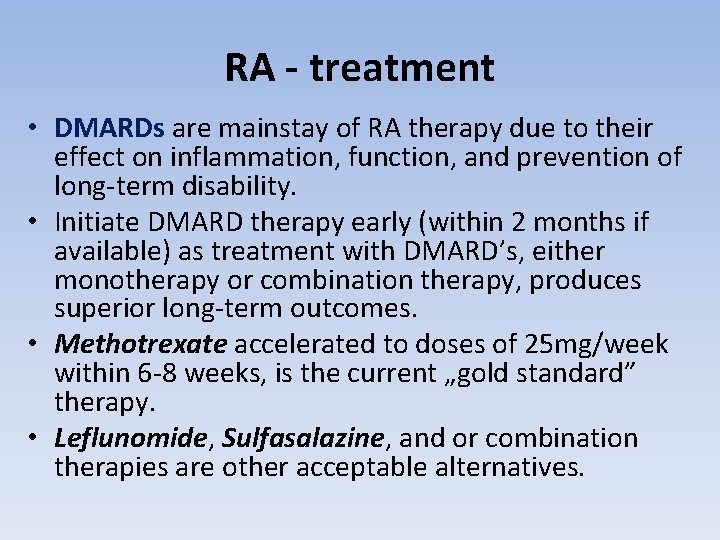

RA - treatment • DMARDs are mainstay of RA therapy due to their effect on inflammation, function, and prevention of long-term disability. • Initiate DMARD therapy early (within 2 months if available) as treatment with DMARD’s, either monotherapy or combination therapy, produces superior long-term outcomes. • Methotrexate accelerated to doses of 25 mg/week within 6 -8 weeks, is the current „gold standard” therapy. • Leflunomide, Sulfasalazine, and or combination therapies are other acceptable alternatives.

RA - treatment • Corticosteroids (CS): low dose (5 -10 mg of predniosone) are higly effective in controling symptoms in patients with active RA • CS may slow the rate of joint damage and thereforemay have a disease modifying effect • The benefits of low dose of CS should always be balanced against the risks • CS can be used nicely as bridge therapy while waiting for a DMARD to work.

RA - treatment • NSAIDs and COXIBs: have analgesic and antiinflammatory properties but do not alter the course of the disease or prevent joint destruction and shouldn’t be used alone for the treatment of RA • Biologics: the high cost of treatment may limit their use as first line therapy in RA. The current approach is to use biologics if there is inadequate response or intolerance of traditional DMARD therapy. Infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, golimumab or tocilizumab and rituximab are highly effective in early RA and/or those with active RA who have failed previous DMARD therapy.

RA - prognosis • Two general categories: 1) 5 -20% have intermittent disease with periods of exacerbation and a relatively good prognosis; 2) 80 -85% have progressive disease with either a slow or rapid course: 50% of patients will be functional class 3 or 4 within 10 years; 30% of patients will be unemployed at 5 years; • Higher incidence of infections, cardiovascular disease and lymphoma.

Spondyloarthropathies • The term ‘spondyloarthritis’ (Sp. A) comprises AS, reactive arthritis, arthritis/spondylitis associated with psoriasis, and arthritis/spondylitis associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). • There is considerable overlap between the single subsets. • The main link between each is the association with the human leukocyte antigen(HLA)-B 27, the same pattern of peripheral joint involvement with an asymmetrical, often pauciarticular, arthritis, predominantly of the lower limbs, and the possible occurrence of sacroiliitis, spondylitis, enthesitis, dactylitis and uveitis. • All Sp. A subsetscan evolve into AS, especially in those patients who are positive for HLA-B 27. The Sp. A subsets can also be split into patients with predominantly axial and predominantly peripheral Sp. A with an overlap between the two parts in about 20– 40%of cases.

Spondyloarthropathies • Spondyloarthropathies (Sp. A) – Ankylosing spondylitis – Reactive arthritis with Reiter syndrome – Psoriatic arthritis – Arthritis associated with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis

Epidemiology of ankylosing spondylitis • AS is a disease that starts normally in the third decade of life, with about 80% of patients developing the first symptoms before the age of 30 and less than 5% of patients being older than 45 at the start of the disease. • Up to 20% of patients are even younger than 20 years when they experience their first symptoms. • Patients who are positive for HLA-B 27 are about 10 years younger than HLA-B 27 -negative patients when the disease starts.

Epidemiology of ankylosing spondylitis • Men are slightly more affected than are women, with a ratio of about 2: 1. • There is a clear correlation between the prevalence of HLA-B 27 and the prevalence of AS in a given population: the higher the HLA-B 27 prevalence the higher the AS prevalence. • HLA-B 27 is positive in 90– 95% of AS patients and in about 80– 90% of patients with non-radiographic axial Sp. A. • This percentage goes down to about 60% in AS patients who also have psoriasis or IBD. • In predominant peripheral. Sp. A, less than 50% of patients are positive for HLA-B 27

Clinical manifestations of ankylosing spondylitis Inflammatory back pain • The main clinical symptoms in AS are pain and stiffness of the back, pre-dominantly of the lower back and the pelvis, but any part of the spine can be involved. • Typical for AS/spondyloarthritis (Sp. A) is inflammatory back pain (IBP) which is defined clinically and not by laboratory tests such as CRP or ESR. • Patients complain about morning stiffness of the back, with improvement on exercise but not by rest. In addition, or alternatively, they report awakening at night, mostly in the second half of the night, because of back pain which improves on getting up and moving around. • Furthermore, back pain should be chronic (>3 months duration) not acute, and it should occur for the first time before the age of 45 years, because the disease starts at a young age; this also helps to differentiate it from degenerative spine disease, the prevalence of which increases with age. Most patients report a mixture of pain and stiffness in the spine, although either can be the main or only symptom.

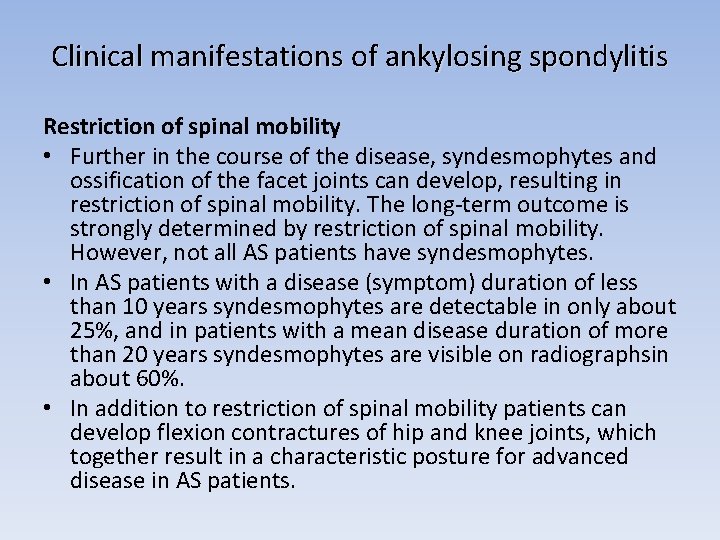

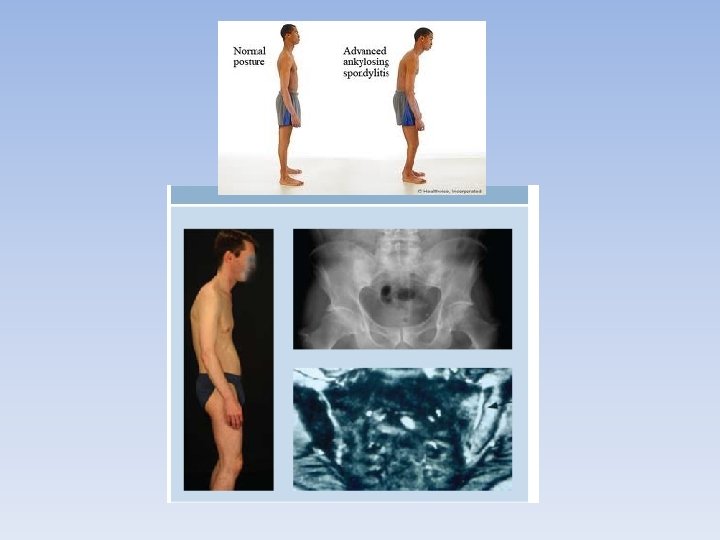

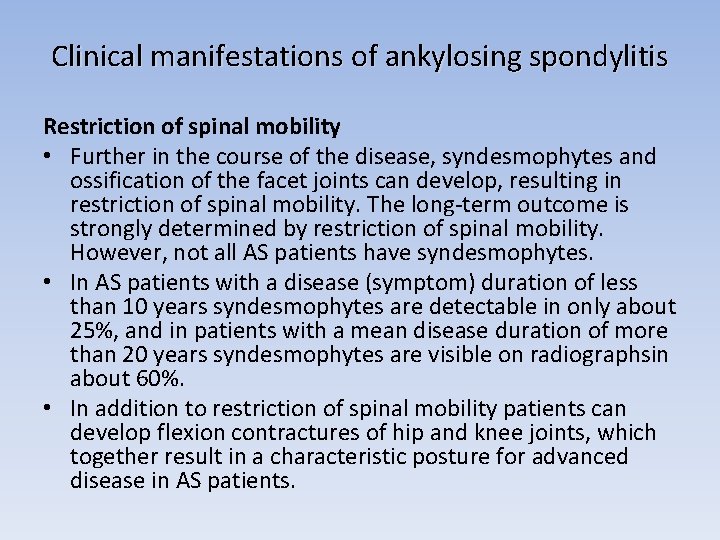

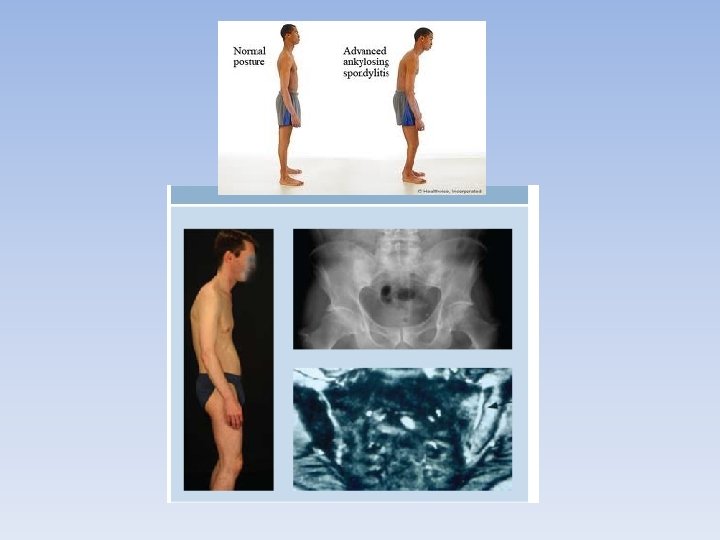

Clinical manifestations of ankylosing spondylitis Restriction of spinal mobility • Further in the course of the disease, syndesmophytes and ossification of the facet joints can develop, resulting in restriction of spinal mobility. The long-term outcome is strongly determined by restriction of spinal mobility. However, not all AS patients have syndesmophytes. • In AS patients with a disease (symptom) duration of less than 10 years syndesmophytes are detectable in only about 25%, and in patients with a mean disease duration of more than 20 years syndesmophytes are visible on radiographsin about 60%. • In addition to restriction of spinal mobility patients can develop flexion contractures of hip and knee joints, which together result in a characteristic posture for advanced disease in AS patients.

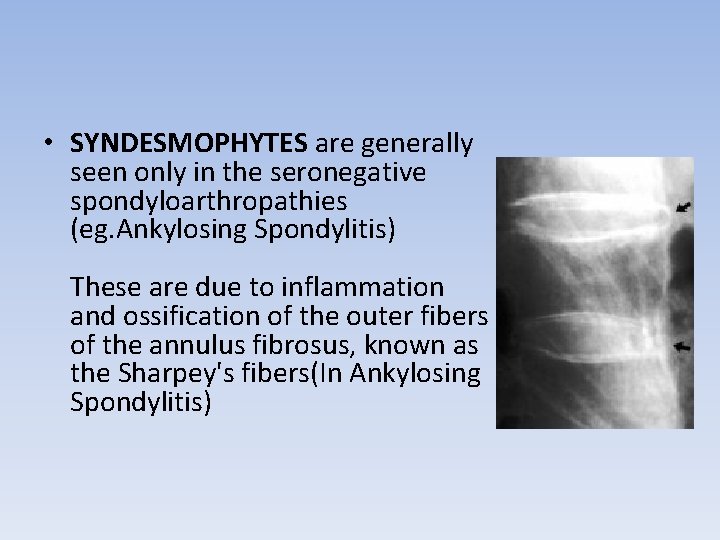

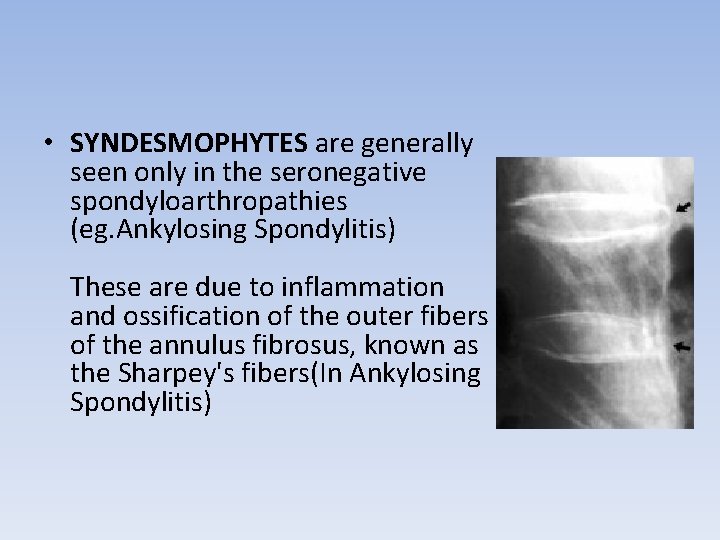

• SYNDESMOPHYTES are generally seen only in the seronegative spondyloarthropathies (eg. Ankylosing Spondylitis) These are due to inflammation and ossification of the outer fibers of the annulus fibrosus, known as the Sharpey's fibers(In Ankylosing Spondylitis)

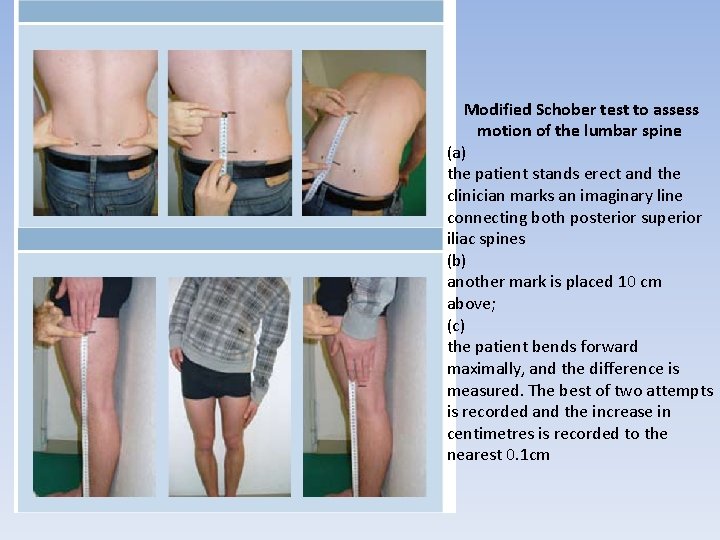

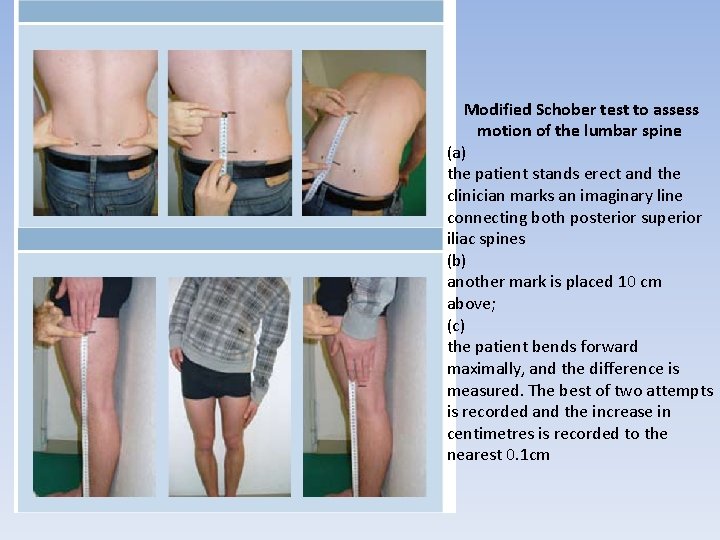

Modified Schober test to assess motion of the lumbar spine (a) the patient stands erect and the clinician marks an imaginary line connecting both posterior superior iliac spines (b) another mark is placed 10 cm above; (c) the patient bends forward maximally, and the difference is measured. The best of two attempts is recorded and the increase in centimetres is recorded to the nearest 0. 1 cm

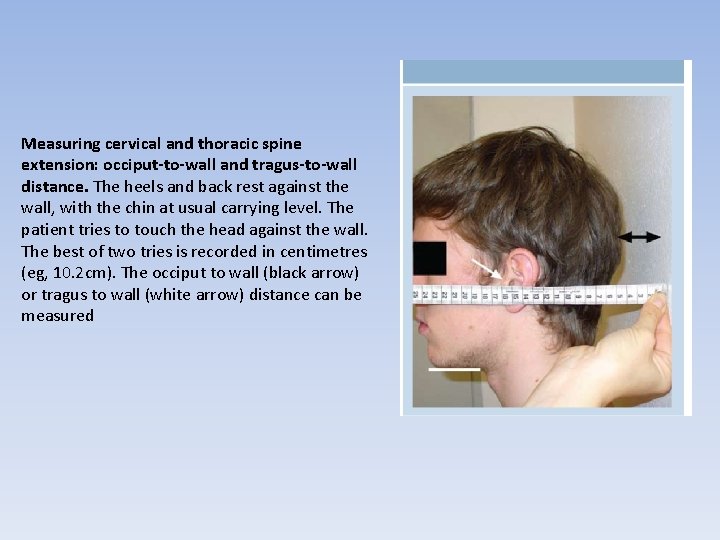

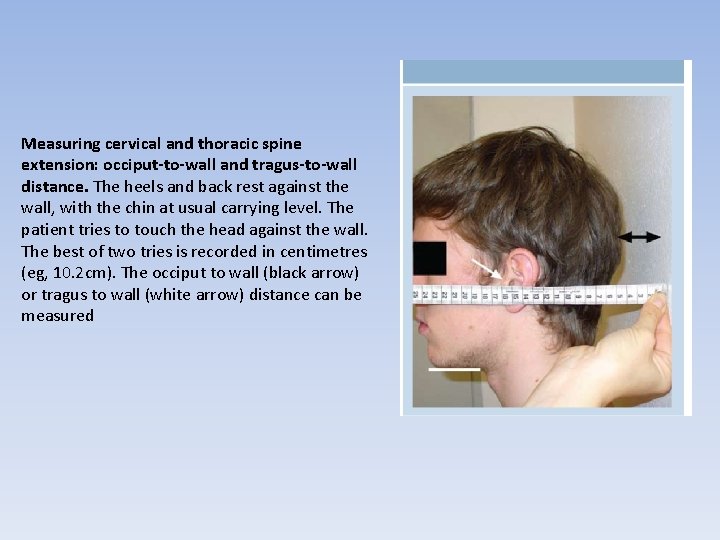

Measuring cervical and thoracic spine extension: occiput-to-wall and tragus-to-wall distance. The heels and back rest against the wall, with the chin at usual carrying level. The patient tries to touch the head against the wall. The best of two tries is recorded in centimetres (eg, 10. 2 cm). The occiput to wall (black arrow) or tragus to wall (white arrow) distance can be measured

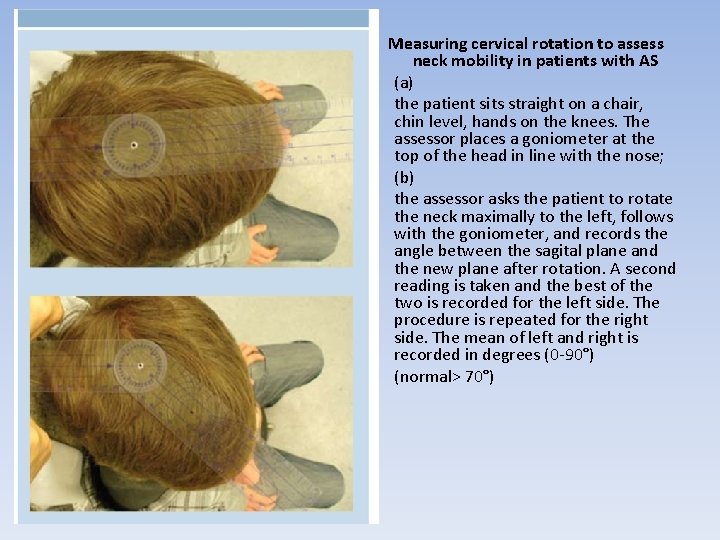

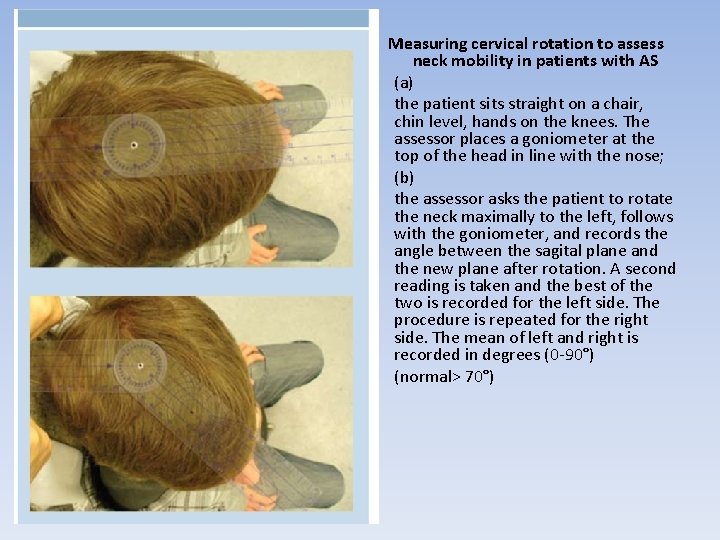

• • • Measuring cervical rotation to assess neck mobility in patients with AS (a) the patient sits straight on a chair, chin level, hands on the knees. The assessor places a goniometer at the top of the head in line with the nose; (b) the assessor asks the patient to rotate the neck maximally to the left, follows with the goniometer, and records the angle between the sagital plane and the new plane after rotation. A second reading is taken and the best of the two is recorded for the left side. The procedure is repeated for the right side. The mean of left and right is recorded in degrees (0 -90°) (normal> 70°)

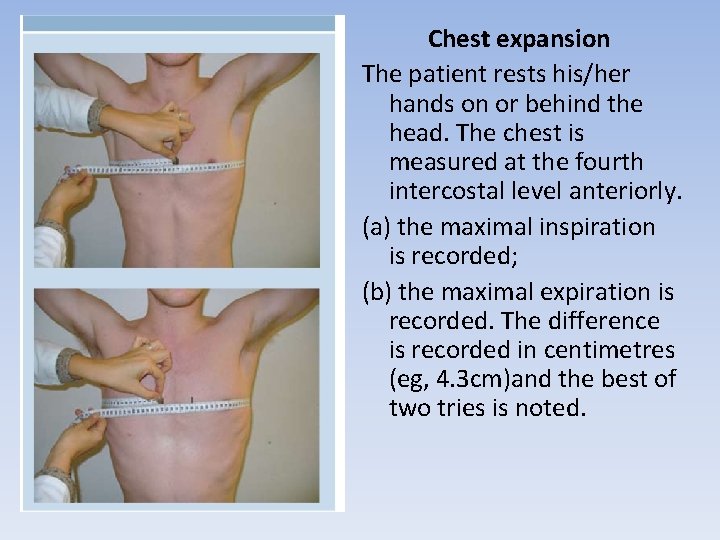

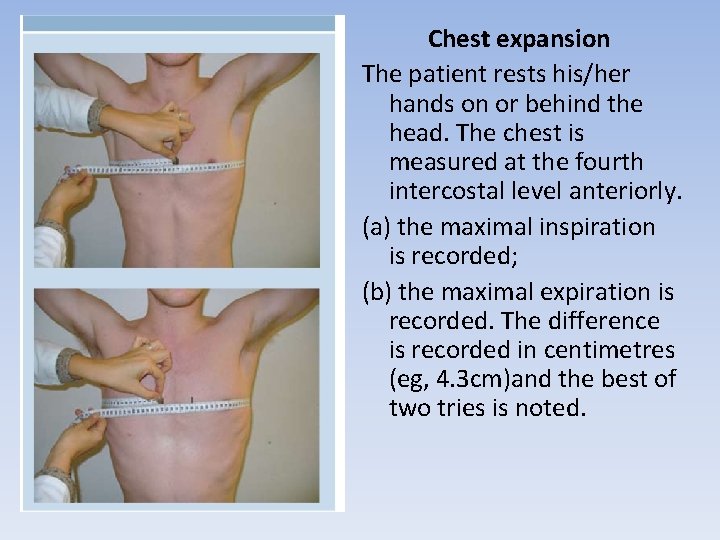

Chest expansion The patient rests his/her hands on or behind the head. The chest is measured at the fourth intercostal level anteriorly. (a) the maximal inspiration is recorded; (b) the maximal expiration is recorded. The difference is recorded in centimetres (eg, 4. 3 cm)and the best of two tries is noted.

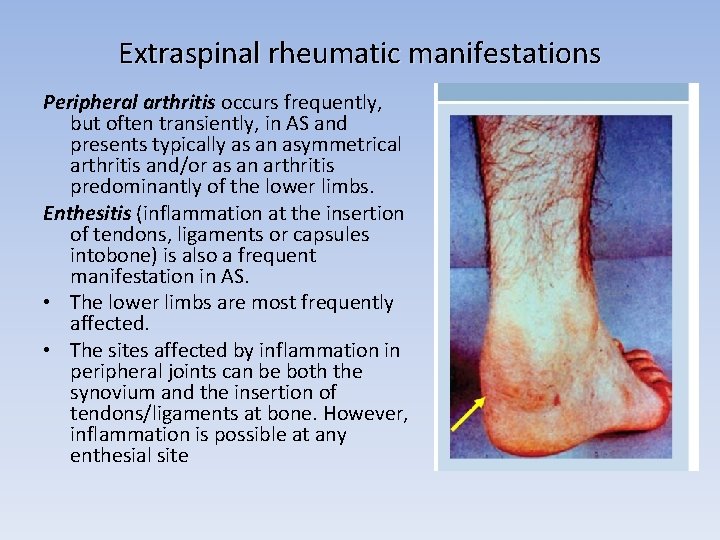

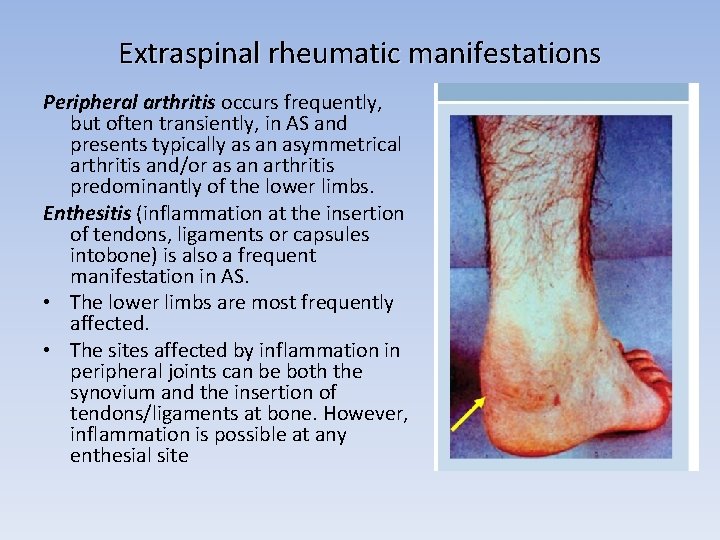

Extraspinal rheumatic manifestations Peripheral arthritis occurs frequently, but often transiently, in AS and presents typically as an asymmetrical arthritis and/or as an arthritis predominantly of the lower limbs. Enthesitis (inflammation at the insertion of tendons, ligaments or capsules intobone) is also a frequent manifestation in AS. • The lower limbs are most frequently affected. • The sites affected by inflammation in peripheral joints can be both the synovium and the insertion of tendons/ligaments at bone. However, inflammation is possible at any enthesial site

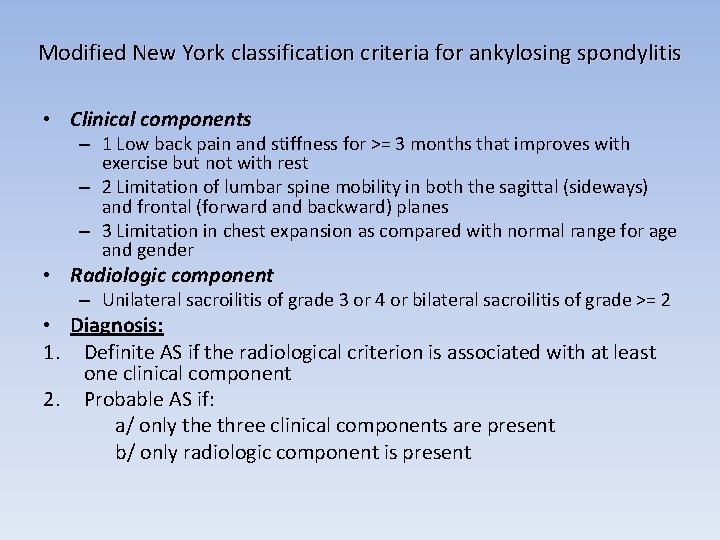

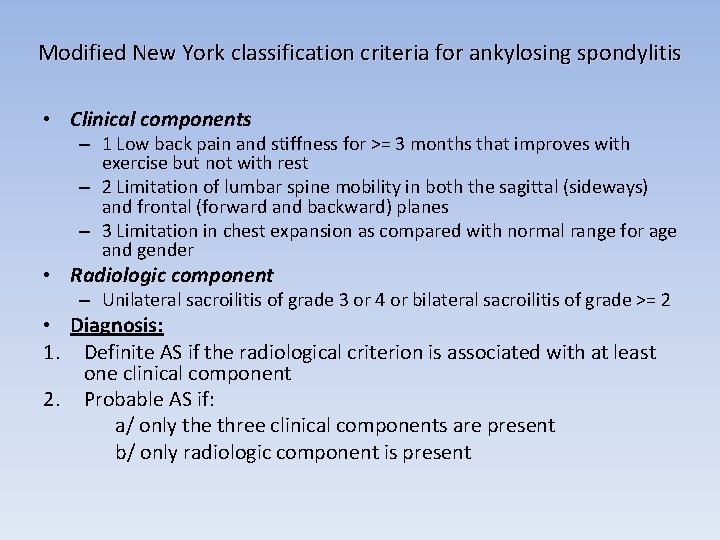

Modified New York classification criteria for ankylosing spondylitis • Clinical components – 1 Low back pain and stiffness for >= 3 months that improves with exercise but not with rest – 2 Limitation of lumbar spine mobility in both the sagittal (sideways) and frontal (forward and backward) planes – 3 Limitation in chest expansion as compared with normal range for age and gender • Radiologic component – Unilateral sacroilitis of grade 3 or 4 or bilateral sacroilitis of grade >= 2 • Diagnosis: 1. Definite AS if the radiological criterion is associated with at least one clinical component 2. Probable AS if: a/ only the three clinical components are present b/ only radiologic component is present

AS - management • General: education • Physiotherapy: regular exercise may slow the progression of spinal stiffness and restriction – it is imperative that patients work with a physiotherapist and understand the role of streching and exercise to minimize the long-term impact of their condition

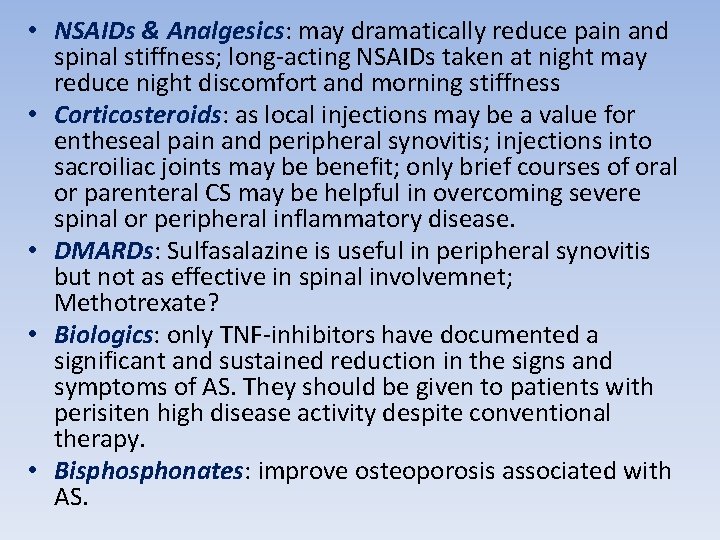

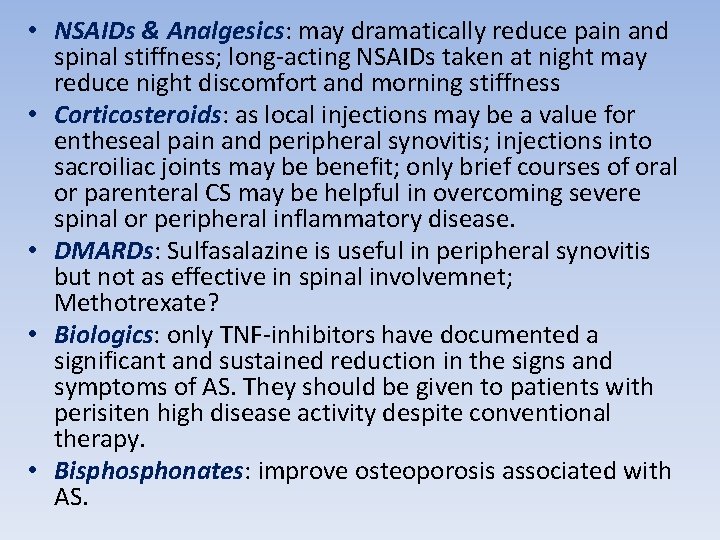

• NSAIDs & Analgesics: may dramatically reduce pain and spinal stiffness; long-acting NSAIDs taken at night may reduce night discomfort and morning stiffness • Corticosteroids: as local injections may be a value for entheseal pain and peripheral synovitis; injections into sacroiliac joints may be benefit; only brief courses of oral or parenteral CS may be helpful in overcoming severe spinal or peripheral inflammatory disease. • DMARDs: Sulfasalazine is useful in peripheral synovitis but not as effective in spinal involvemnet; Methotrexate? • Biologics: only TNF-inhibitors have documented a significant and sustained reduction in the signs and symptoms of AS. They should be given to patients with perisiten high disease activity despite conventional therapy. • Bisphonates: improve osteoporosis associated with AS.

Prognosis • Most patients with mild disease are able to continue with a resonable level of functional activity and full time employment • Disease activity fluctuates over decades with very few individuals enetering long term remission (1%); • AS doesn’t affect overall mortality • Physiotherapy is extremely important for keeping mobility and reducing contractures.