Restricted Preference Domains In Social Choice Two Perspectives

- Slides: 25

Restricted Preference Domains In Social Choice: Two Perspectives Edith Elkind University of Oxford

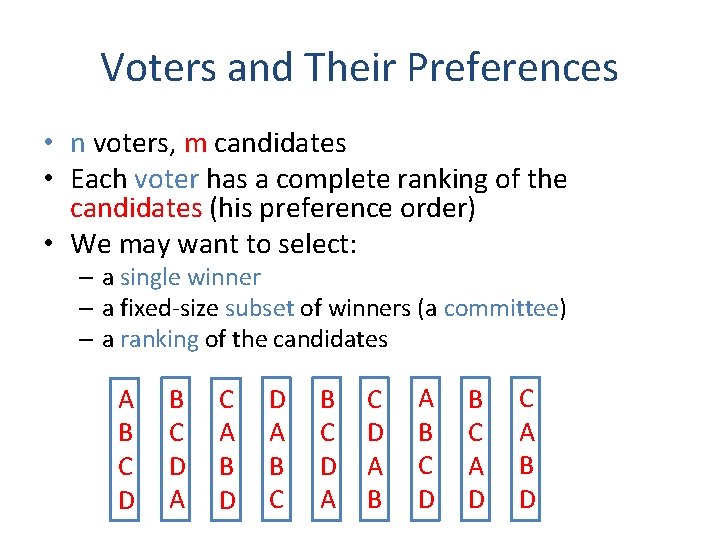

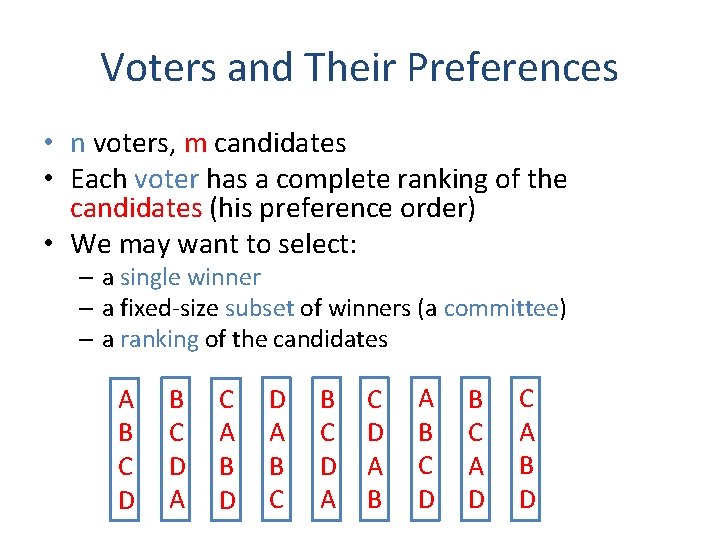

Voters and Their Preferences • n voters, m candidates • Each voter has a complete ranking of the candidates (his preference order) • We may want to select: – a single winner – a fixed-size subset of winners (a committee) – a ranking of the candidates A B C D A C A B D D A B C D A B C D B C A D C A B D

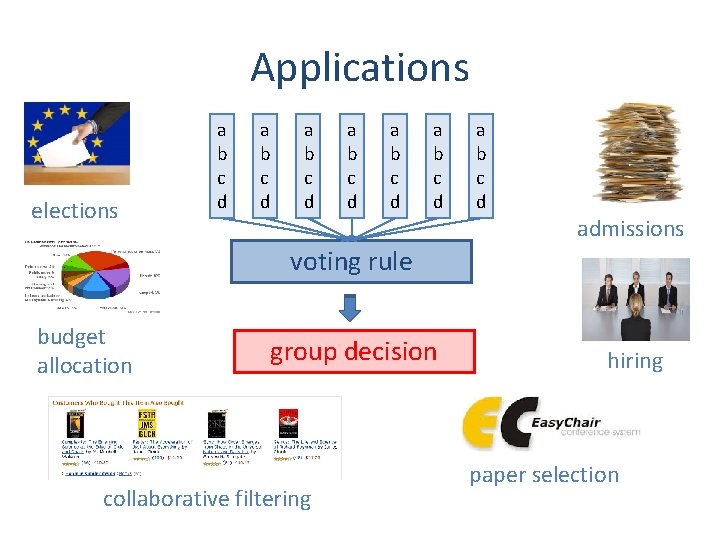

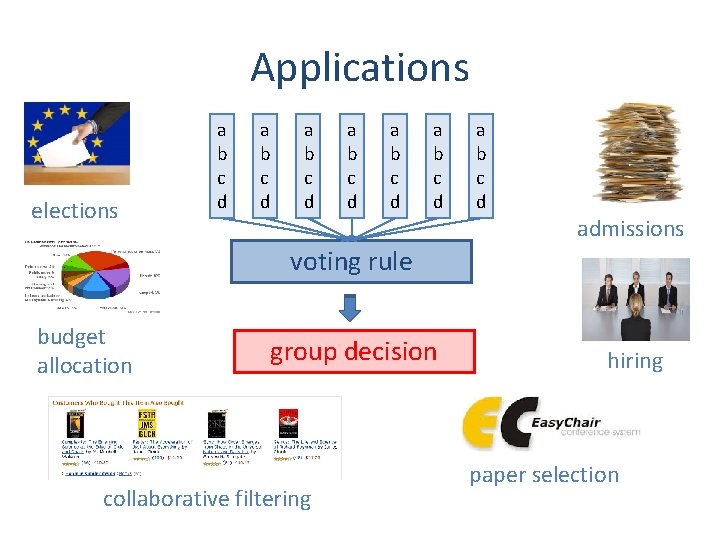

Applications elections a b c d a b c d admissions voting rule budget allocation group decision collaborative filtering hiring paper selection

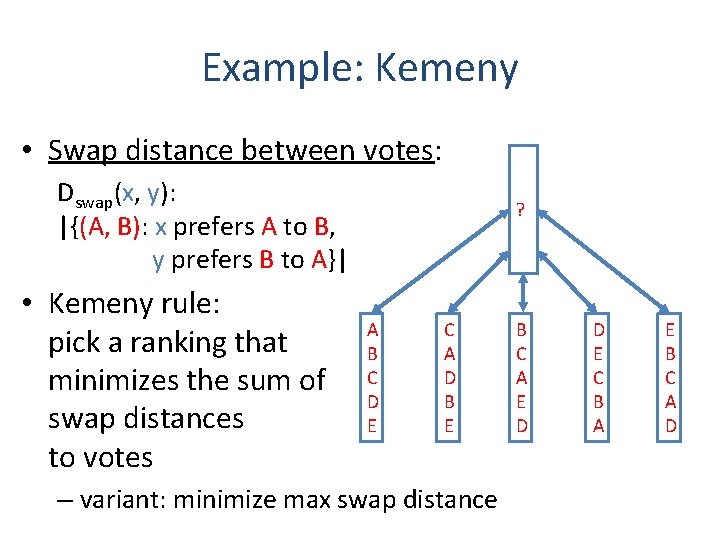

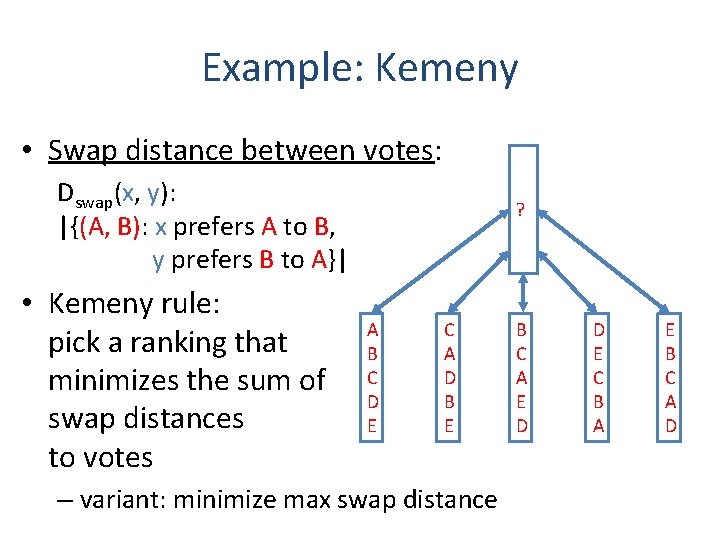

Example: Kemeny • Swap distance between votes: Dswap(x, y): |{(A, B): x prefers A to B, y prefers B to A}| • Kemeny rule: pick a ranking that minimizes the sum of swap distances to votes ? A B C D E C A D B E – variant: minimize max swap distance B C A E D D E C B A E B C A D

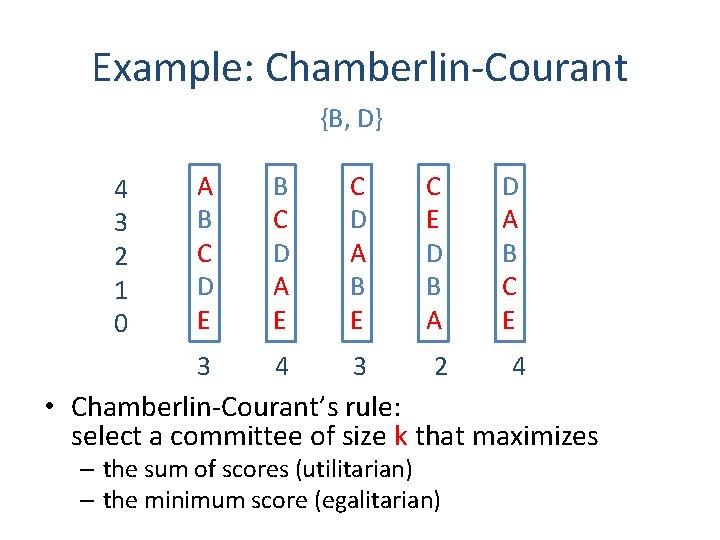

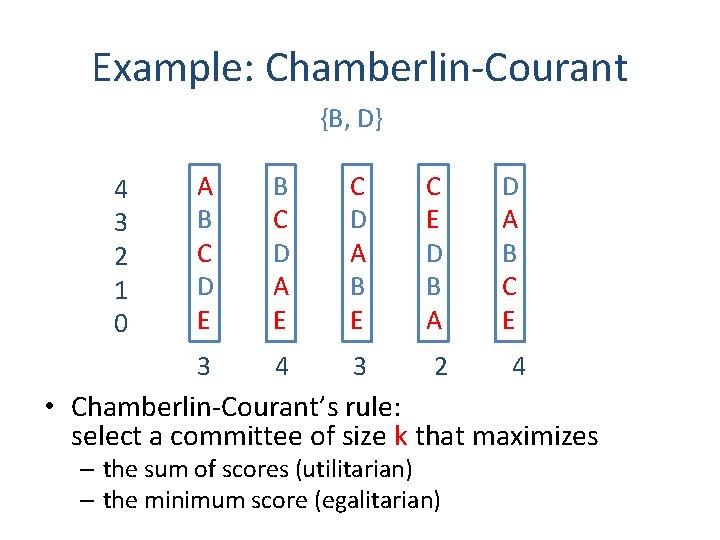

Example: Chamberlin-Courant {B, D} 4 3 2 1 0 A B C D E B C D A E C D A B E C E D B A D A B C E 3 4 3 2 4 • Chamberlin-Courant’s rule: select a committee of size k that maximizes – the sum of scores (utilitarian) – the minimum score (egalitarian)

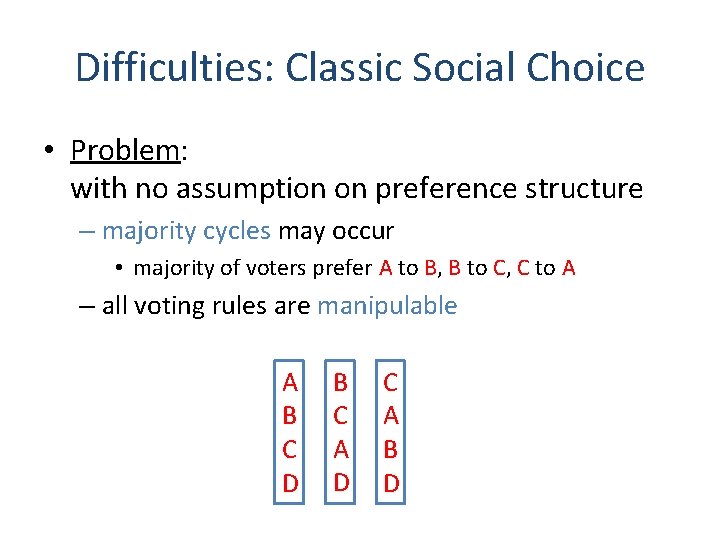

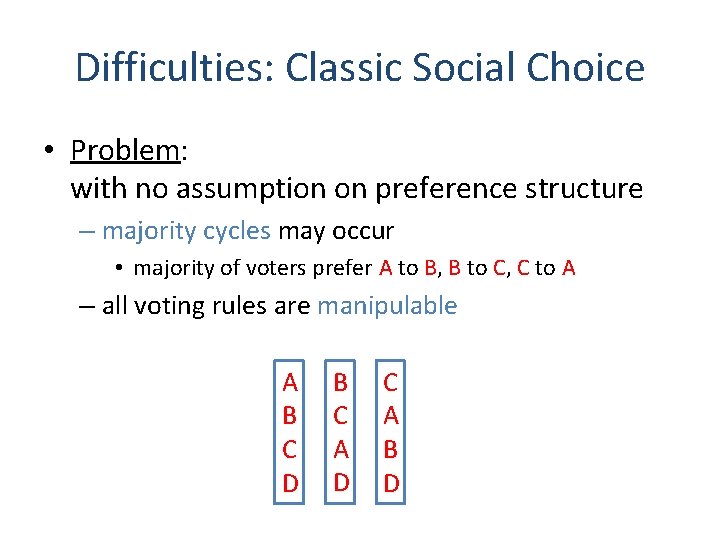

Difficulties: Classic Social Choice • Problem: with no assumption on preference structure – majority cycles may occur • majority of voters prefer A to B, B to C, C to A – all voting rules are manipulable A B C D B C A D C A B D

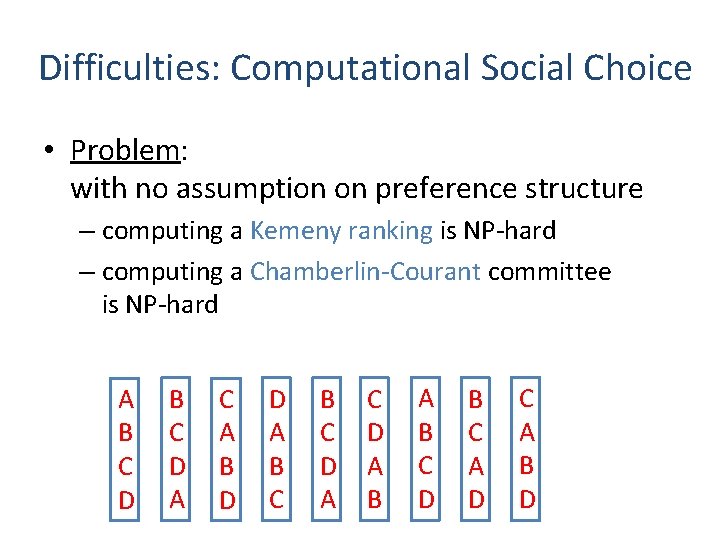

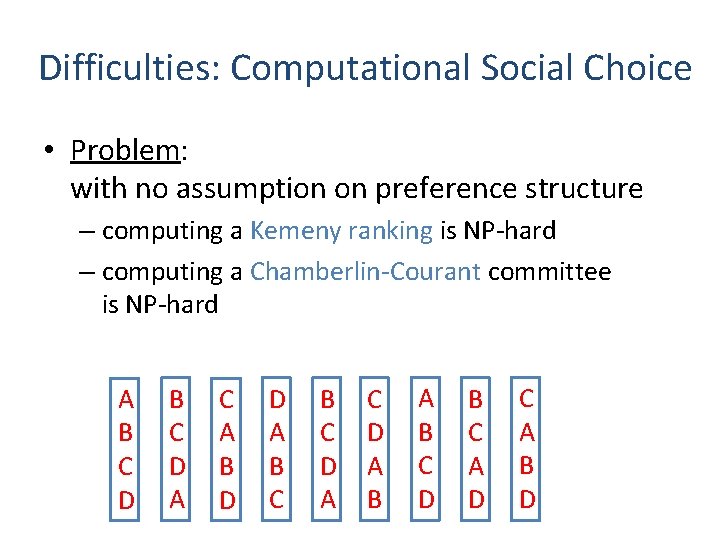

Difficulties: Computational Social Choice • Problem: with no assumption on preference structure – computing a Kemeny ranking is NP-hard – computing a Chamberlin-Courant committee is NP-hard A B C D A C A B D D A B C D A B C D B C A D C A B D

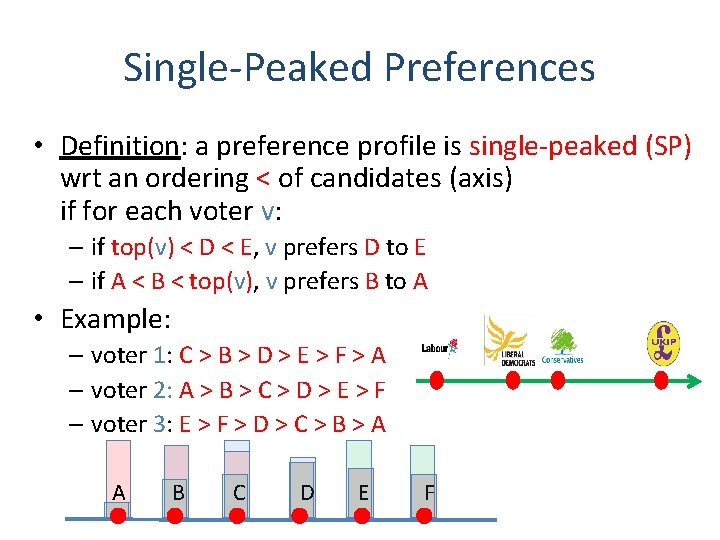

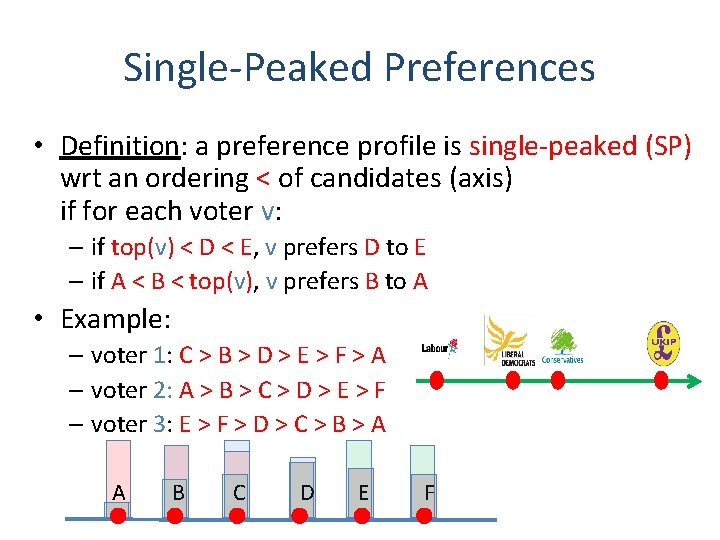

Single-Peaked Preferences • Definition: a preference profile is single-peaked (SP) wrt an ordering < of candidates (axis) if for each voter v: – if top(v) < D < E, v prefers D to E – if A < B < top(v), v prefers B to A • Example: – voter 1: C > B > D > E > F > A – voter 2: A > B > C > D > E > F – voter 3: E > F > D > C > B > A A B C D E F

Example: Temperature • Perfect water temperature? +16 +20 +23 +25 +27 +30

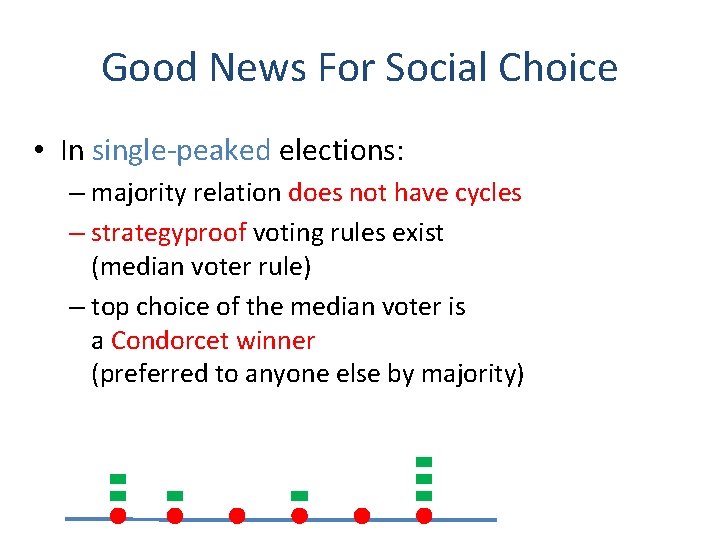

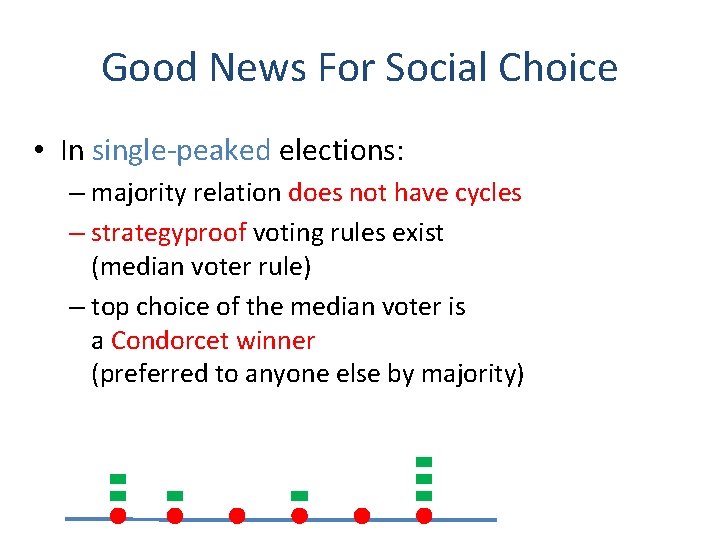

Good News For Social Choice • In single-peaked elections: – majority relation does not have cycles – strategyproof voting rules exist (median voter rule) – top choice of the median voter is a Condorcet winner (preferred to anyone else by majority)

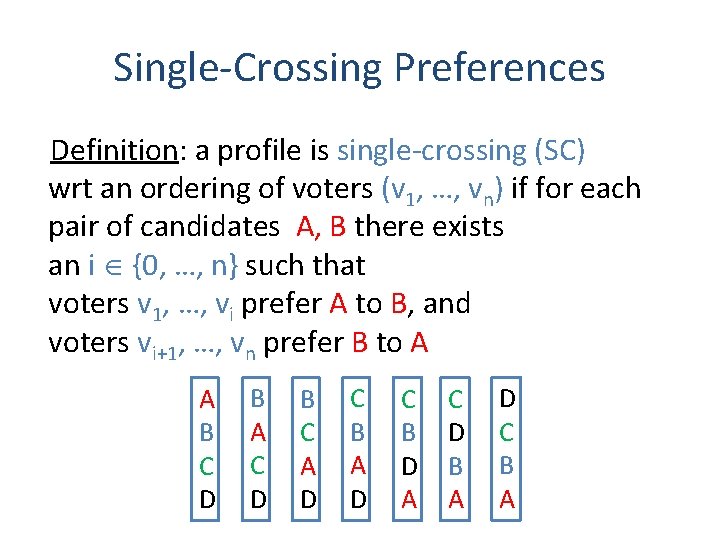

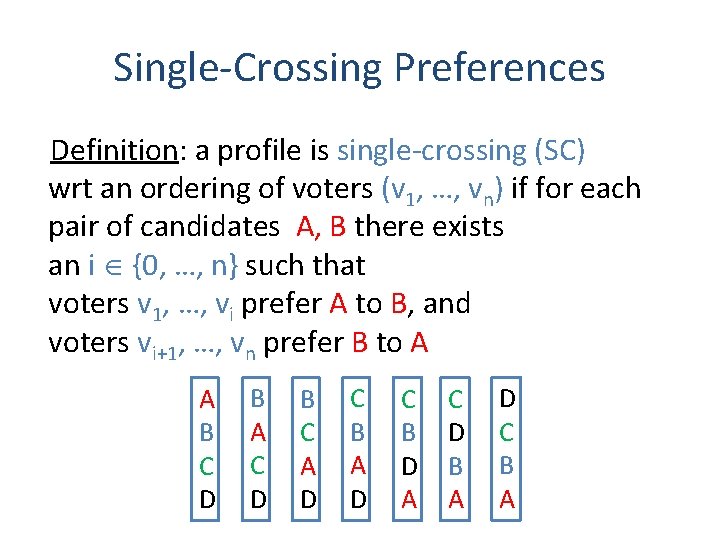

Single-Crossing Preferences Definition: a profile is single-crossing (SC) wrt an ordering of voters (v 1, …, vn) if for each pair of candidates A, B there exists an i {0, …, n} such that voters v 1, …, vi prefer A to B, and voters vi+1, …, vn prefer B to A A B C D B A C D B C A D C B D A C D B A D C B A

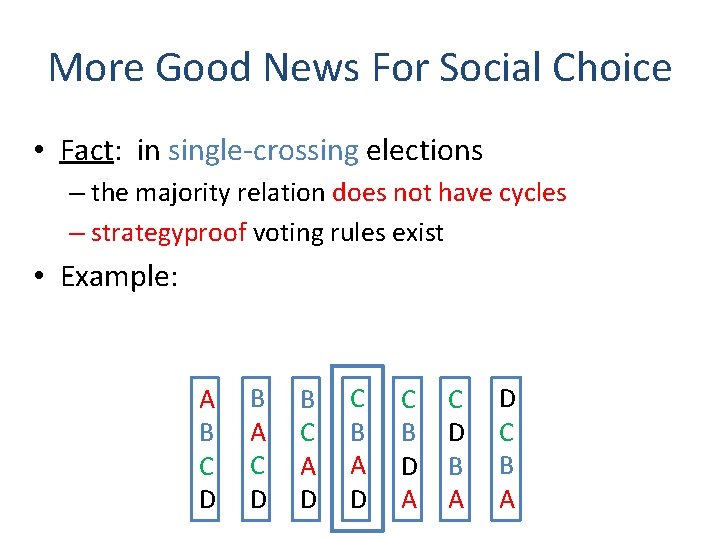

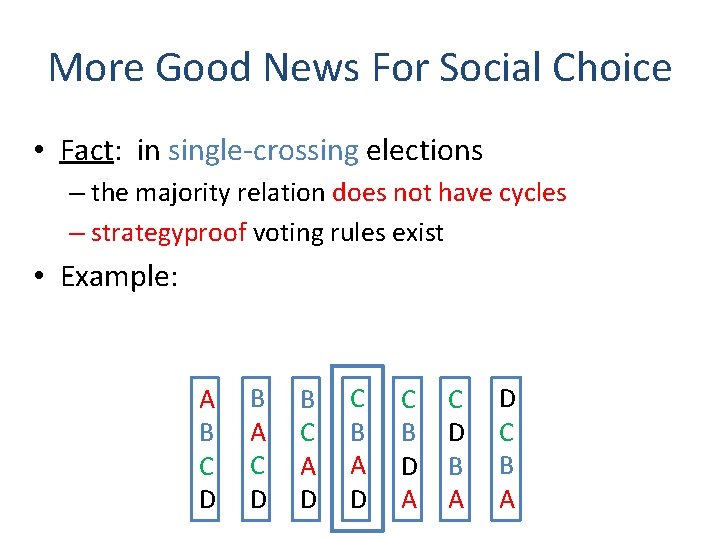

More Good News For Social Choice • Fact: in single-crossing elections – the majority relation does not have cycles – strategyproof voting rules exist • Example: A B C D B A C D B C A D C B D A C D B A D C B A

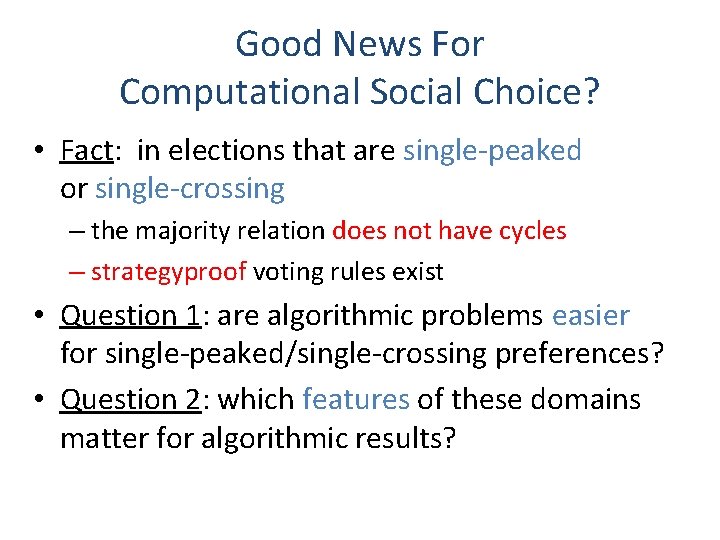

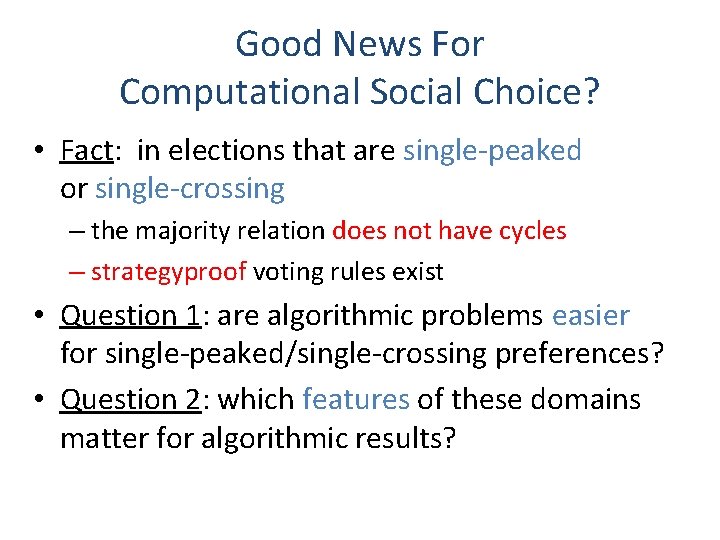

Good News For Computational Social Choice? • Fact: in elections that are single-peaked or single-crossing – the majority relation does not have cycles – strategyproof voting rules exist • Question 1: are algorithmic problems easier for single-peaked/single-crossing preferences? • Question 2: which features of these domains matter for algorithmic results?

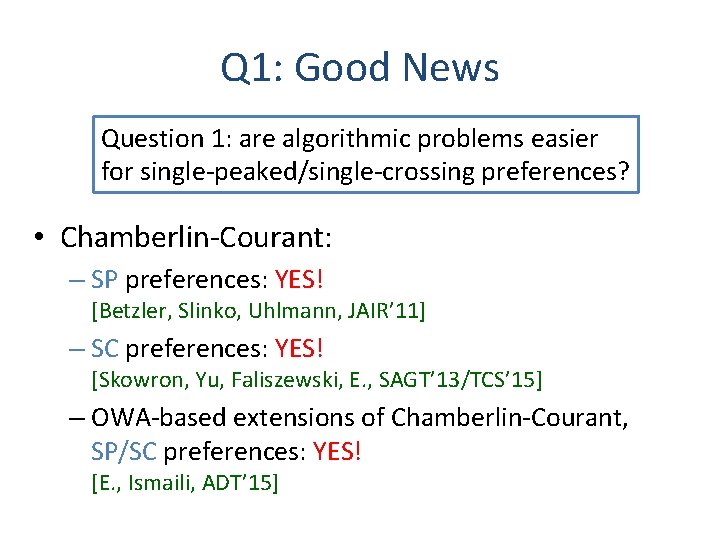

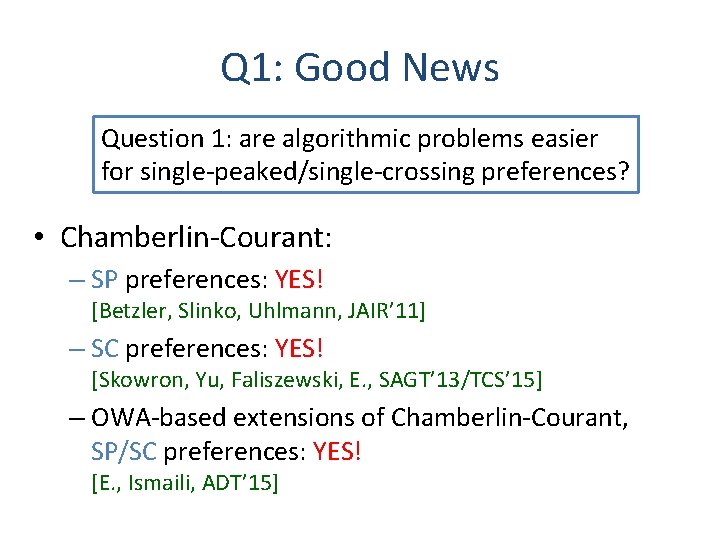

Q 1: Good News Question 1: are algorithmic problems easier for single-peaked/single-crossing preferences? • Chamberlin-Courant: – SP preferences: YES! [Betzler, Slinko, Uhlmann, JAIR’ 11] – SC preferences: YES! [Skowron, Yu, Faliszewski, E. , SAGT’ 13/TCS’ 15] – OWA-based extensions of Chamberlin-Courant, SP/SC preferences: YES! [E. , Ismaili, ADT’ 15]

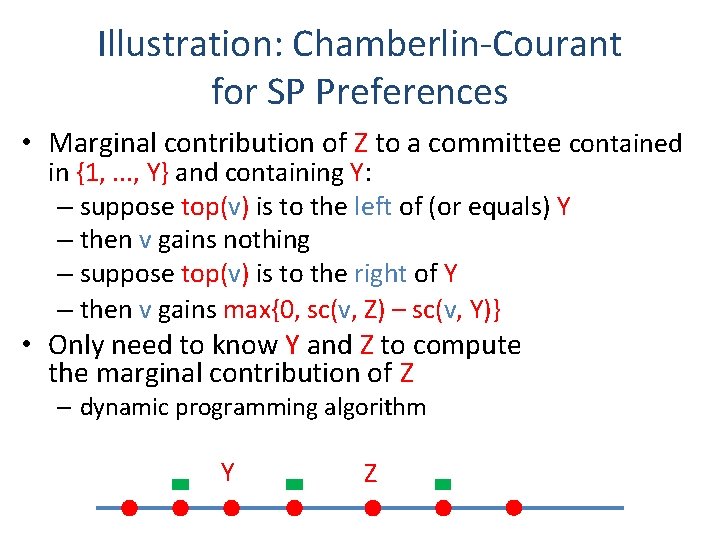

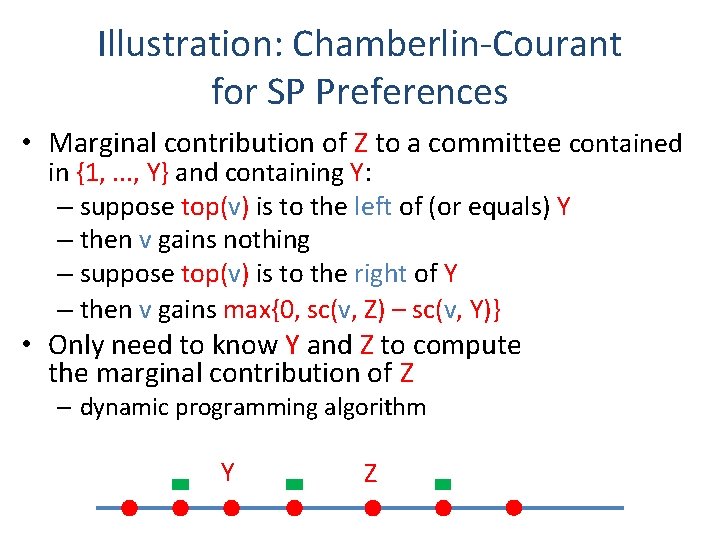

Illustration: Chamberlin-Courant for SP Preferences • Marginal contribution of Z to a committee contained in {1, . . . , Y} and containing Y: – suppose top(v) is to the left of (or equals) Y – then v gains nothing – suppose top(v) is to the right of Y – then v gains max{0, sc(v, Z) – sc(v, Y)} • Only need to know Y and Z to compute the marginal contribution of Z – dynamic programming algorithm Y Z

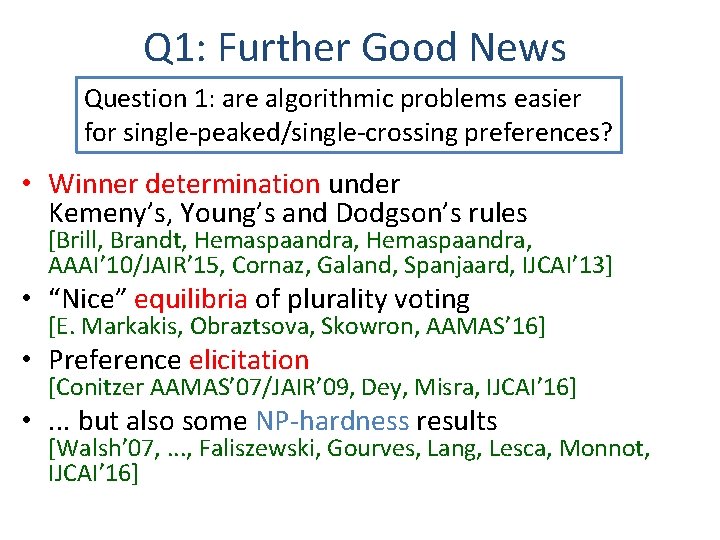

Q 1: Further Good News Question 1: are algorithmic problems easier for single-peaked/single-crossing preferences? • Winner determination under Kemeny’s, Young’s and Dodgson’s rules [Brill, Brandt, Hemaspaandra, AAAI’ 10/JAIR’ 15, Cornaz, Galand, Spanjaard, IJCAI’ 13] • “Nice” equilibria of plurality voting [E. Markakis, Obraztsova, Skowron, AAMAS’ 16] • Preference elicitation [Conitzer AAMAS’ 07/JAIR’ 09, Dey, Misra, IJCAI’ 16] • . . . but also some NP-hardness results [Walsh’ 07, . . . , Faliszewski, Gourves, Lang, Lesca, Monnot, IJCAI’ 16]

Q 2: Why Is SP/SC Useful? • Social choice: because there is a median voter • Computational social choice: – because there is a median voter or. . . – because the ordering of voters/candidates enables us to do dynamic programming • side note: the relevant orderings can be computed efficiently even if not part of the input • Implications?

Extension: Dichotomous Preferences • Dichotomous preferences: each voter approves some candidates and disapproves others • Analogues of SP/SC preferences A can be defined for this setting B • Social choice: {A, B} dichotomous preferences are easy C D • Computational social choice: E dichotomous SP/SC preferences are algorithmically useful [Faliszewski, Hemaspaandra, Rothe, TARK’ 09/I&C’ 11, E. , Lackner, IJCAI’ 15]

Extension: Preferences SP on a Circle • Intuition: – candidates are placed on a circle – for each voter we can cut the circle so that her preferences are SP on the resulting line A • Social choice: preferences SP on a circle are useless – A > B > C, B > C > A, C > A > B C • Computational social choice: preferences SP on a circle can be exploited [Peters, Lackner AAAI’ 17] B

Extension: Almost SP/SC Preferences • Preferences that can be made SP/SC by – deleting a few voters or candidates, – swapping a few pairs of candidates, etc. • Social choice: almost structured preferences are useless • Computaitonal social choice: “almost SP/SC” can be exploited [Faliszewski, Hemaspaandra, TARK’ 11/AIJ’ 14, Yang, Guo, AAMAS’ 14, ’ 15, Misra, Sonar, Vaidyanathan ADT’ 17. ]

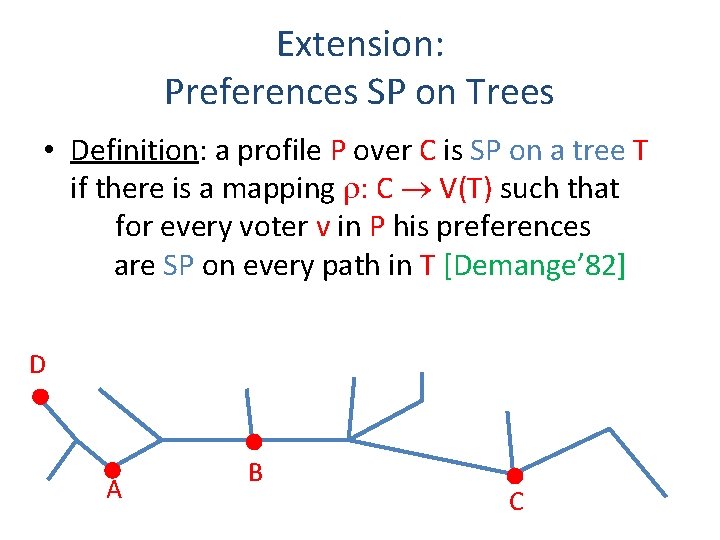

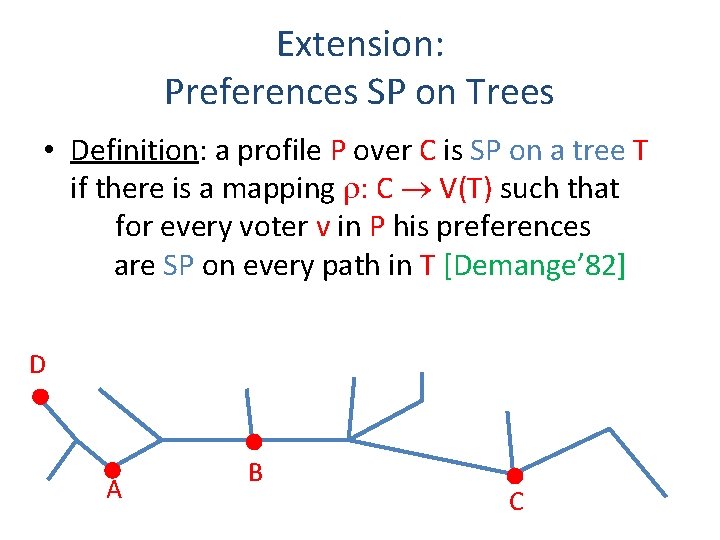

Extension: Preferences SP on Trees • Definition: a profile P over C is SP on a tree T if there is a mapping r: C V(T) such that for every voter v in P his preferences are SP on every path in T [Demange’ 82] D A B C

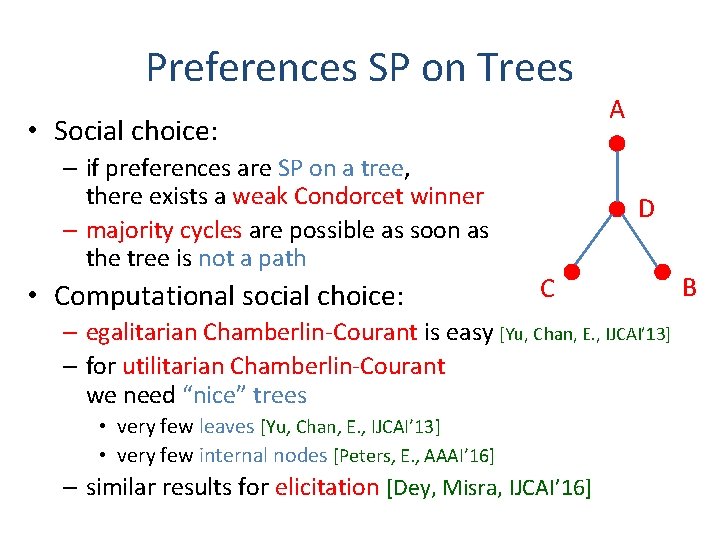

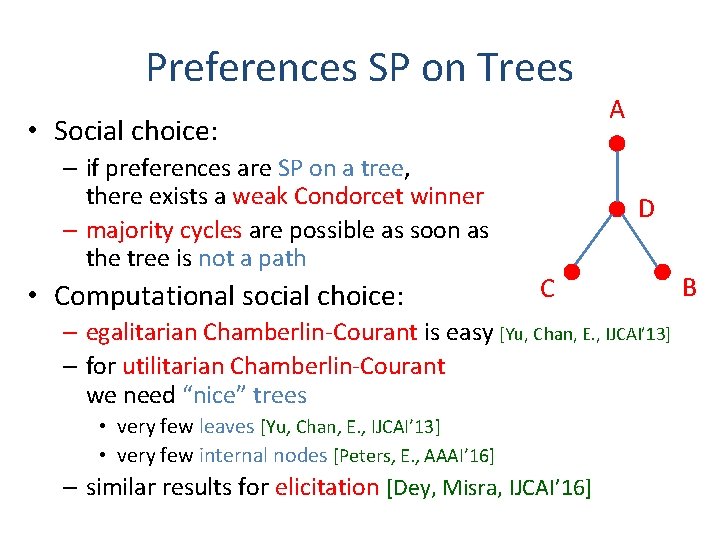

Preferences SP on Trees • Social choice: – if preferences are SP on a tree, there exists a weak Condorcet winner – majority cycles are possible as soon as the tree is not a path • Computational social choice: A D C – egalitarian Chamberlin-Courant is easy [Yu, Chan, E. , IJCAI’ 13] – for utilitarian Chamberlin-Courant we need “nice” trees • very few leaves [Yu, Chan, E. , IJCAI’ 13] • very few internal nodes [Peters, E. , AAAI’ 16] – similar results for elicitation [Dey, Misra, IJCAI’ 16] B

Not In This Talk. . . • Identifying preferences that are – SP on nice trees (mostly easy) – dichotomous SP (easy) – SP on a circle (easy) – nearly SP/SC (mostly hard, but sometimes easy) • Preferences SC on a tree [Clearwater, Slinko, Puppe, IJCAI’ 15] • Possibly SP/SC preferences [Lackner AAAI’ 14, E. , Faliszewski, Lackner, Obraztsova, AAAI’ 15]

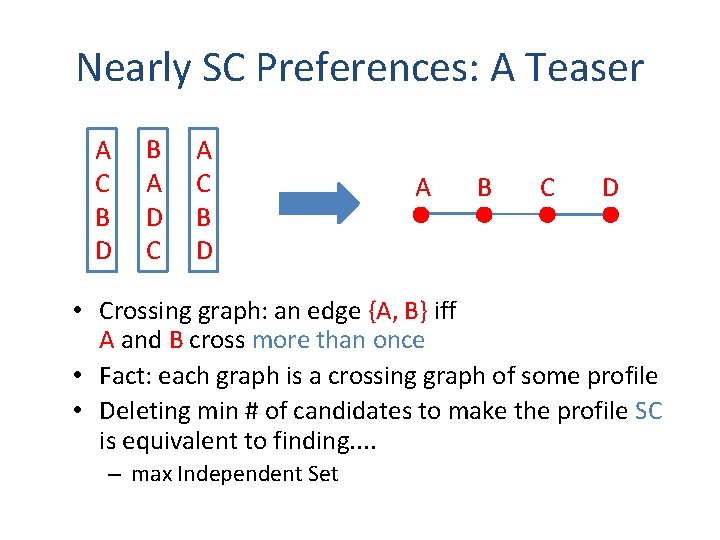

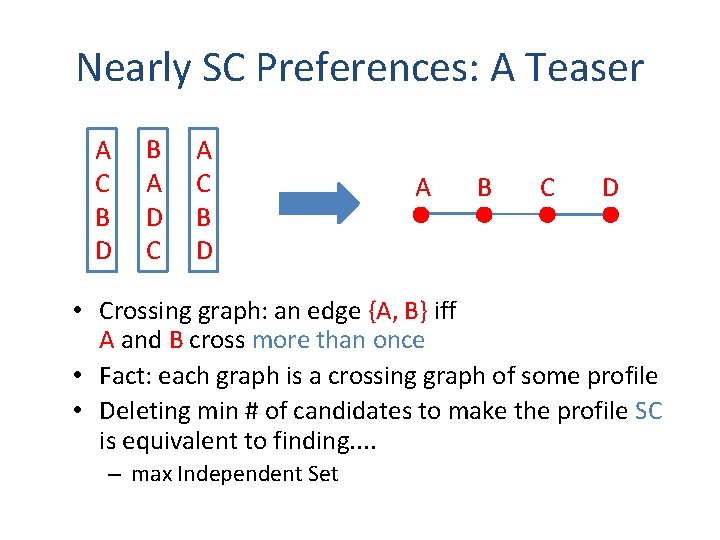

Nearly SC Preferences: A Teaser A C B D B A D C A C B D A B C D • Crossing graph: an edge {A, B} iff A and B cross more than once • Fact: each graph is a crossing graph of some profile • Deleting min # of candidates to make the profile SC is equivalent to finding. . – max Independent Set

Summary • Preference restrictions are useful both axiomatically and computationally – but for subtly different reasons – this has implications for generalizations • Real-life preferences are very rarely single-peaked or single-crossing – but are often close to having these properties – algorithmic results tend to be more robust than axiomatic results