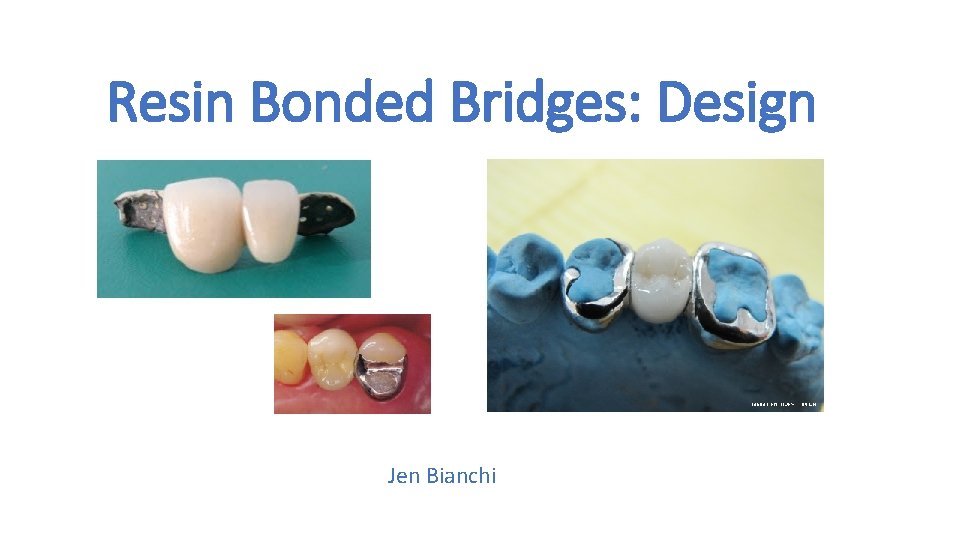

Resin Bonded Bridges Design Jen Bianchi Aims Objectives

Resin Bonded Bridges: Design Jen Bianchi

Aims & Objectives 1) Discuss case selection, indications and contra-indications for RBBs 2) Review the success rates for RBBs 3) Discuss abutment tooth selection for RBB 4) Discuss preparation for RBBs 5) Discuss wing design for RBBs 6) Consider the appropriate number of abutments 7) Discuss rigidity of the RBB framework 8) Discuss posterior RBBs 9) Occlusal considerations 10) Discuss pontic design

Case Selection • Careful case selection, appropriate design and attention to operative detail are key factors for the clinical longevity of RBBs • Well motivated patient • Good oral hygiene • Stable periodontium

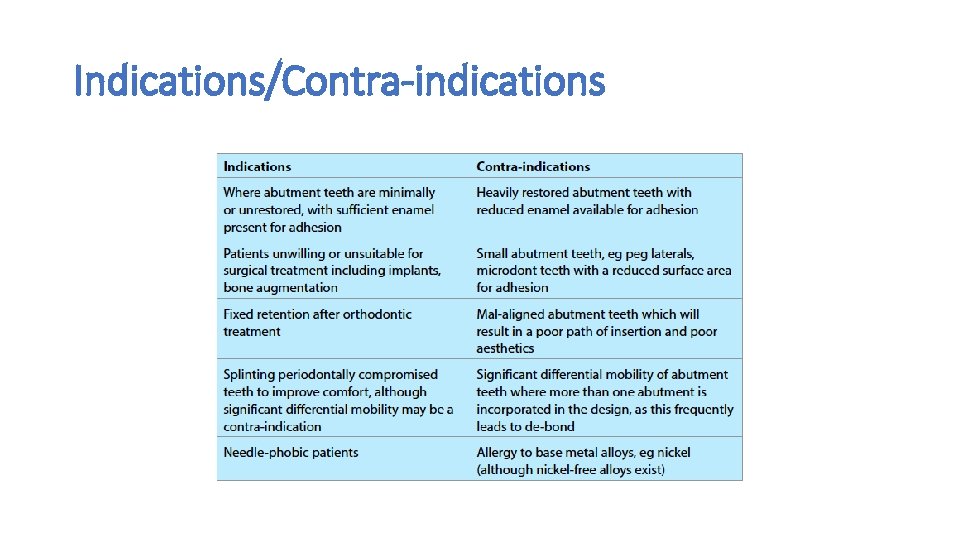

Indications/Contra-indications

Success Rates • Resin bonded bridges have been used since the 1970 s • Systematic review by Pjetursson et al 2008 reported a survival rate of 87. 7% at 5 years • 2015 prospective study of 771 resin retained bridges carried out by King et al showed that most failures occurred in the first four years, and that very few failed thereafter, with an estimated survival rate of 80. 4% at 10 years

Treatment Planning/Consent Full assessment and discussion with the patient • All available treatment options have been discussed with the patient and they are happy to have a resin bonded bridge • Costs have been discussed • The tooth/teeth missing have been missing for long enough to allow adequate healing of the ridge • Clinical photographs • Articulated study casts (+/- diagnostic wax up)

Abutment Tooth Selection • Factors to consider: 1) Size of abutment tooth 2) Restorative status 3) Angulation and position of the potential abutment tooth 4) Periodontal status

Abutment Tooth Selection(1): Size • The abutment tooth should have sufficient height and width to ensure that a sufficient surface area of enamel is available for bonding • The retainer should be designed to incorporate the maximum available enamel

Abutment Tooth Selection(2): Restorative Status • RBBs are ideally suited to the replacement of single units. Ideally the abutment tooth is unrestored or minimally restored • A large area of enamel allows for a predictable bond to the abutment and is a crucial indicator for success • King et al (2015) found that the presence of one or more old restorations on the abutment tooth was associated with a three-fold increase in risk of failure, whereas a new restoration was not significantly more likely to fail than an unrestored abutment • • • Enamel gives the best bond strength Consider replacing any small GIC or amalgam restorations with composite Re-surface old composite restorations that are otherwise sound to improve bond streng

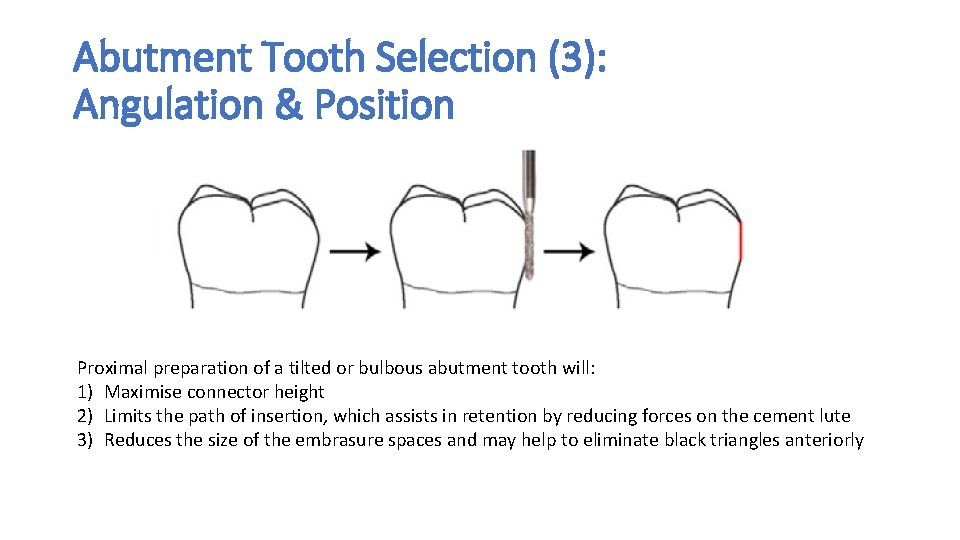

Abutment Tooth Selection (3): Angulation & Position • Unfavourably tilted or bulbous teeth will reduce the connector height • A narrow connector will cause an increase in flexibilty of the bridge and lead to failure • In tilted or bulbous abutment teeth, consideration should be given to a minimal proximal surface preparation to reduce the bulbosity (anteriorly and posteriorly)

Abutment Tooth Selection (3): Angulation & Position Proximal preparation of a tilted or bulbous abutment tooth will: 1) Maximise connector height 2) Limits the path of insertion, which assists in retention by reducing forces on the cement lute 3) Reduces the size of the embrasure spaces and may help to eliminate black triangles anteriorly

Abutment Tooth Selection (4): Periodontal Status • It is difficult to define an absolute threshold of periodontal support below which bridgework is contra-indicated, there is no clinical evidence relating to this • A systematic review by Lulic et al (2007) indicated that the long term prognosis of bridgework using abutments that have severely reduced periodontal support depends on the maintenance of a healthy periodontium • Careful control of occlusal force distribution in this cohort of patients is advised

Abutment Tooth Selection (4): Periodontal Status • Careful consideration should be given if there is greater than 50% bone loss • If there is bone loss >50% with mobility, consider a fixed-fixed design to splint the mobile teeth but ensure the occlusal forces are evenly distributed over both abutment teeth • Ideally if the abutment teeth are mobile, you want them to have similar mobility, both in direction and magnitude • Quite tricky to get a decent impression of mobile teeth!

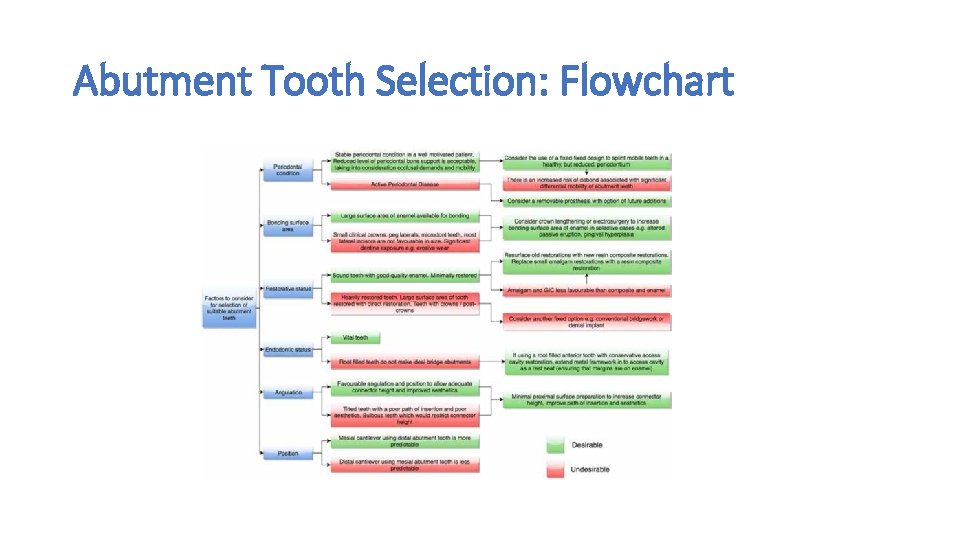

Abutment Tooth Selection: Flowchart

Preparation (1) • No preparation at all? • Advantages • (1) No tooth tissue loss, leaves plenty of enamel to bond to • (2) No sensitivity • (3) If teeth aren’t in occlusion you could question the need for a cingulum rest Disadvantages (1) You are asking a lot of your luting cement if the teeth are in occlusion! (2) May be difficult to locate the wing during cementation Clinicians who opt to do no preparation may ask the technician to add a little extra metal to be added to the wing that hooks over the incisal edge. This helps aid accurate location of the wing during cementation and can be cut off after. However, there is potential for this to detract from aesthetic inspection of the bridge at try in.

Preparation (2) • Cingulum Rest • This is minimal with no real loss of enamel so won’t reduce bond strength • Reduces potential sheer stresses within the luting cement caused by occlusal load • Helps to locate the wing in the correct place during cementation • In tilted or bulbous abutment teeth, consideration should be given to a minimal proximal surface preparation to reduce the bulbosity (see previous slide)

Preparation (3) • Cervical chamfer • Advantages • (1) Reduces the potential for an overhang of the cervical margin • (2) Can help with positioning the wing during cementation Disadvantages (1) Reduces enamel bond (2) Potential for dentine to be exposed and this may cause the patient sensitivity

Wing Design • Maximum enamel coverage • Occlusal rest seats are important to help resist the increased occlusal forces posteriorly so try to incorporate the palatal/lingual cusps and occlusal surfaces of posterior teeth • Aiming to get as close to a 1800 wrap around to the wing retainer as possible (posteriorly) • Anteriorly, extend the retainer onto the incisal edge to aid with location at cementation - aesthetic compromise is minimal? • Addition of location tags – cutting these off immediately after cementation may reduce your bond strength

Number of Abutments • It would seem logical that 2 wings increases the surface area for boding so should increase retention. However, frequently, you can get a partial debond of one of the retainers • The design of choice when replacing a single unit is to cantilever the pontic from a single abutment tooth • Fixed-fixed resin bonded bridgework has a lower survival rate and there is evidence that they are twice as likely to fail compared to cantilever designs • King et al (2015) showed that fixed-fixed RBBs are more likely to fail by an odds ratio of 2. 23 (Prospective study of 771 RBBs) • Djemal et al (1999) showed fixed-fixed RRBs are more likely to fail by an odds ratio of 1. 94 (Reterospective study of 832 RBBs)

Framework Rigidity • The longer the span of the bridge, the greater the need for rigidity in the framework. Flexure may lead to bond/bridge failure • Framework rigidity is crucial in posterior RBBs where the increased occlusal loads are higher • The thickness of the nickel-chromium retainer should be at least 0. 7 mm to give adequate rigidity. Ensure you communicate this to the lab

Posterior Resin Bonded Bridges • The use of RBBs to replace posterior teeth is less predictable than anterior teeth due to increased occlusal demands • There is little published evidence assessing the factors associated with success for the replacement of molar teeth with RBBs • When designing posterior RBBs you should apply the same design principles you would use anteriorly

Occlusal Considerations • Your pre-operative assessment should include examination of the occlusion – articulated study casts. ? facebow reg in larger span or multiple bridges • Bonding a metal wing to the palatal surface of a tooth on a patient who has a tooth to tooth overbite will create an early contact in their occlusion • Need to discuss this with the patient prior to treatment • Ideally want only a light contact, if any, of the pontic in ICP • The ICP contact should be kept clear of the margin of the retainer • Design options to combat this issue are: • 1) Adjust the opposing tooth when you cement the bridge in place • 2) Cut occlusal clearance during preparation of the abutment tooth • 3) Cement the bridge in high, effectively acting as a Dahl appliance.

Pontic Design • The pontic should achieve a passive contact with the tissues and allow adequate oral hygiene by the patient • The two most common pontic designs for bridgework are • 1) Modified ridge-lap • 2) Ovate • better emergence profile but technically more demanding to make and may require electrosurgery to modify the shape of the soft tissue

Aesthetic considerations • Central incisors as abutments • The enamel can be quite translucent and the metal can shine through. • Centrals can look grey and dull – consider using a opaque luting cement? • This will make whatever shade you choose for the pontic look poor Canines as abutments Often the canine is quite bulbous and this can cause the connector to be too fragile The bulboisty can often impede oral hygiene and aesthetics May need to design a guide plane into your preparation to overcome these issues

References • Resin Bonded Bridges – the Problem or the Solution? Part 1: Assessment and Design • Dent Update 2016; 43: 506 -521 Advanced Operative Dentistry. A Practical Approach Chapter 18 p 227 David Ricketts & David Bartlett

- Slides: 25