Remote Monitoring and Management of the Heart Failure

- Slides: 62

Remote Monitoring and Management of the Heart Failure Patient: Telemonitoring of the HF patient Dr Scott Mc. Kenzie The Prince Charles Hospital Holy Spirit Northside Hospital University of Queensland

Overview • Why we need remote monitoring in heart failure • Tools for remote monitoring • Effectiveness of • What might work

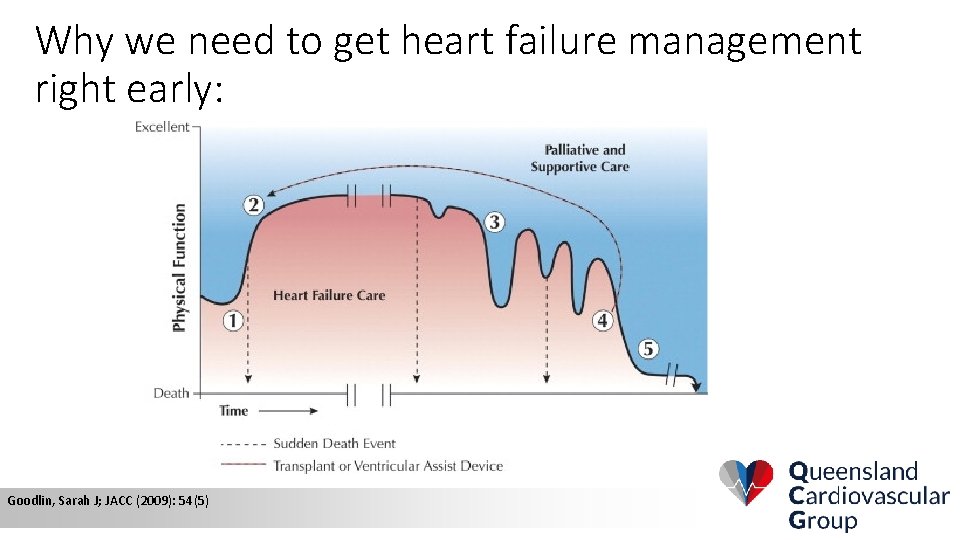

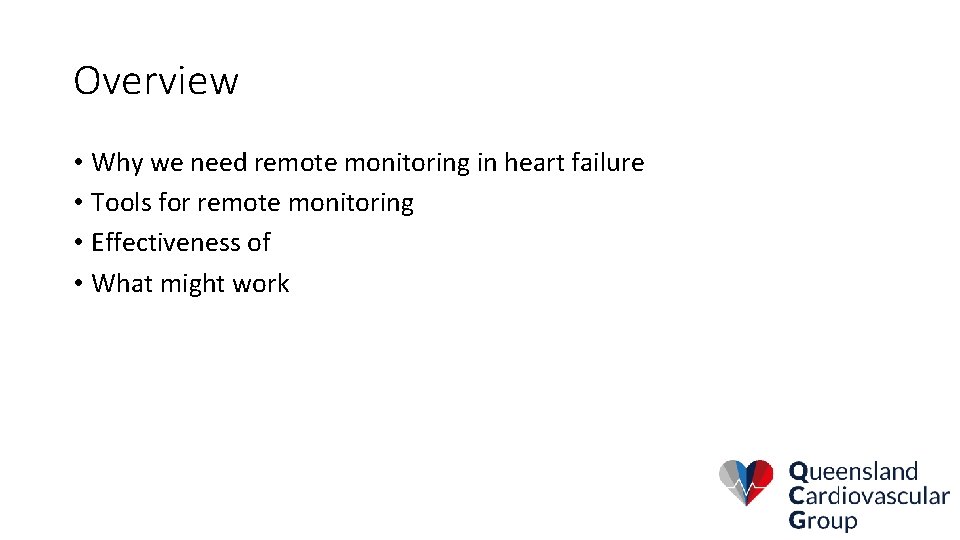

Why we need to get heart failure management right early: Goodlin, Sarah J; JACC (2009): 54(5)

Heart Failure Care Costs • Potentially 23 Million patients world wide • Over $39 Billion annually in USA • About 1 – 2% of total annual health expenditure in the developed world Liao, L. , Allen, L. A. & Whellan, D. J. Pharmacoeconomics 26, 447– 462 (2008).

Heart failure in Australia • Estimated 930, 000 people (4. 3% of population) with chronic heart failure (CHF) in Australia 1 • 30, 000 new HF patients diagnosed each year 2 • Prevalence of CHF and its associated deaths continue to rise 2, 3 • 8. 9 Days Average length of stay 4 1. Stewart S, et al. Population prevalence of heart failure in Australia: an under-estimated burden of disease. Poster P 1722 at ESC Heart Failure 2014 2. AIHW: Field B 2003. Heart failure … what of the future? Bulletin no. 6. AIHW Cat. No. AUS 34. Canberra: AIHW 3. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Causes of Death, Australia, 2012. 4. National Heart Foundation of Australia. A systematic approach to chronic heart failure care: a consensus statement. Melbourne: National Heart Foundation of Australia, 2013.

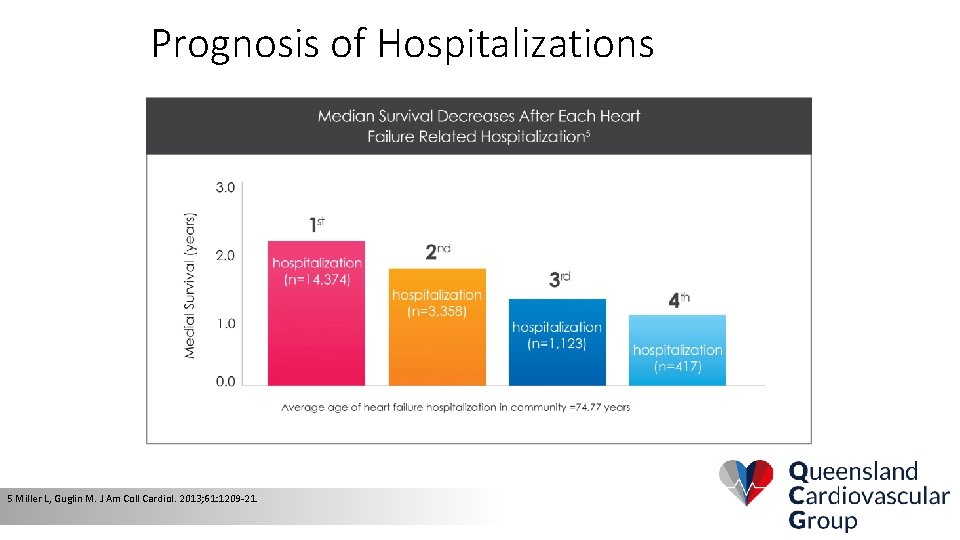

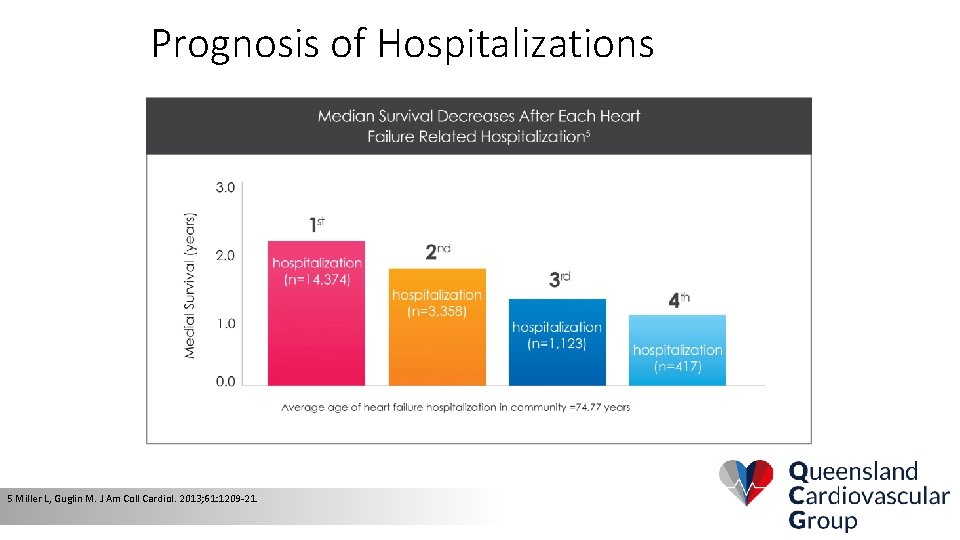

Prognosis of Hospitalizations 5 Miller L, Guglin M. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 61: 1209 -21.

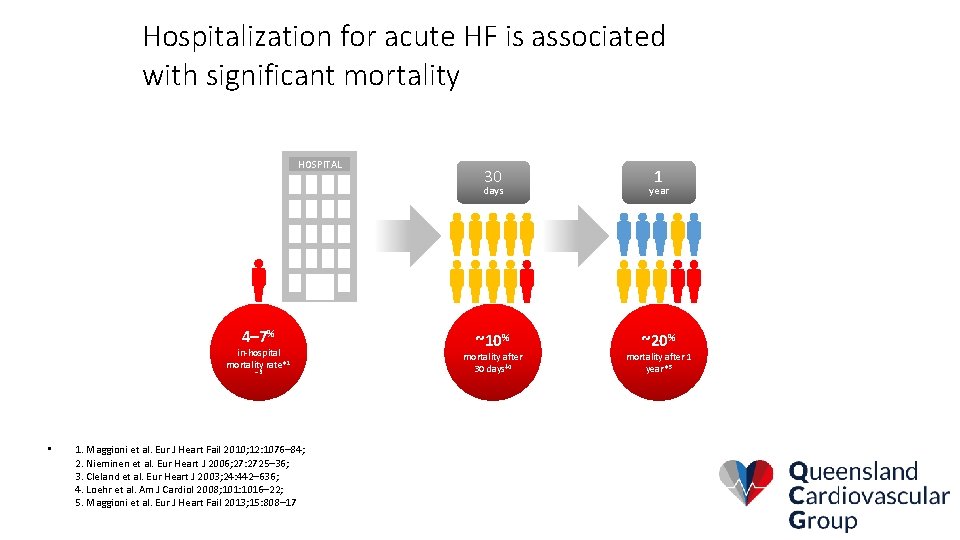

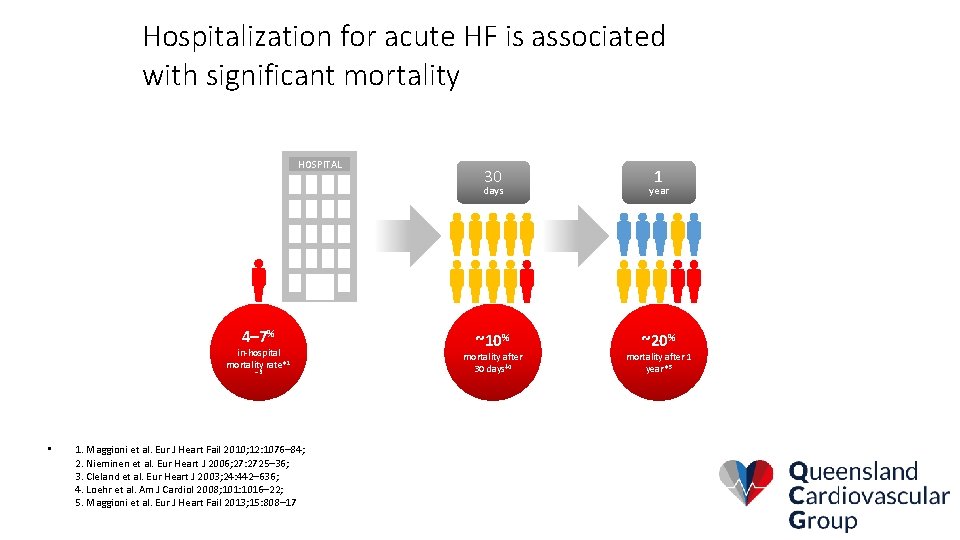

Hospitalization for acute HF is associated with significant mortality HOSPITAL 4– 7% in-hospital mortality rate*1 – 3 • 1. Maggioni et al. Eur J Heart Fail 2010; 12: 1076– 84; 2. Nieminen et al. Eur Heart J 2006; 27: 2725– 36; 3. Cleland et al. Eur Heart J 2003; 24: 442– 636; 4. Loehr et al. Am J Cardiol 2008; 101: 1016– 22; 5. Maggioni et al. Eur J Heart Fail 2013; 15: 808– 17 30 1 days year ~10% ~20% mortality after 30 days‡ 4 mortality after 1 year*5

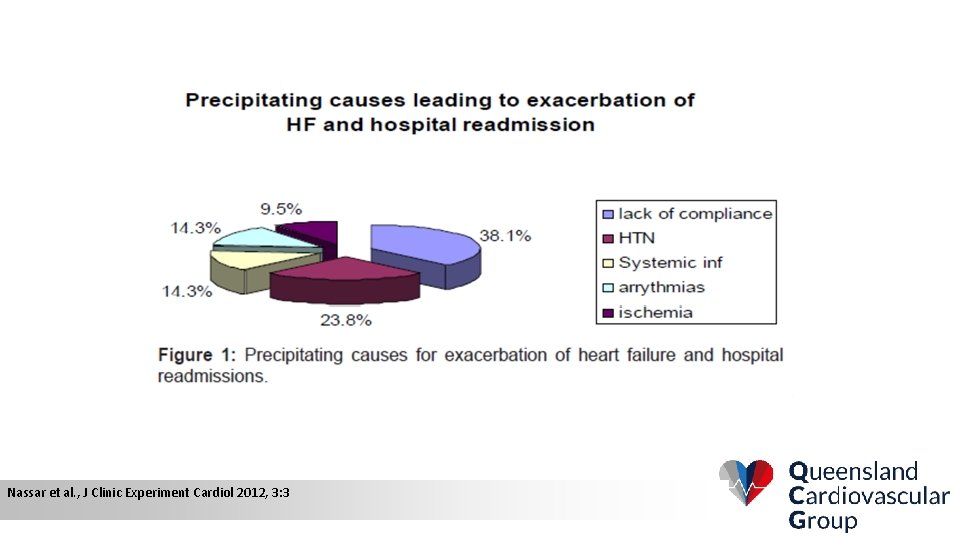

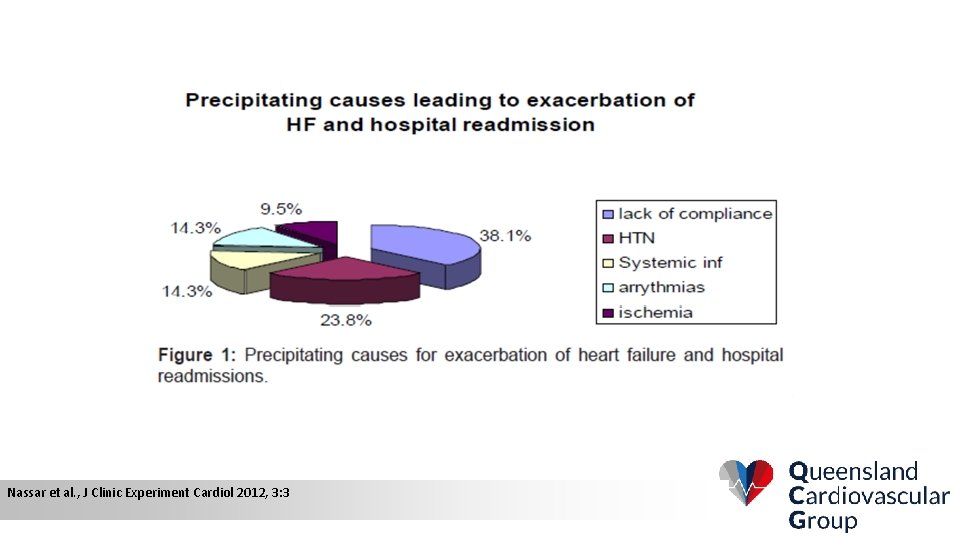

Nassar et al. , J Clinic Experiment Cardiol 2012, 3: 3

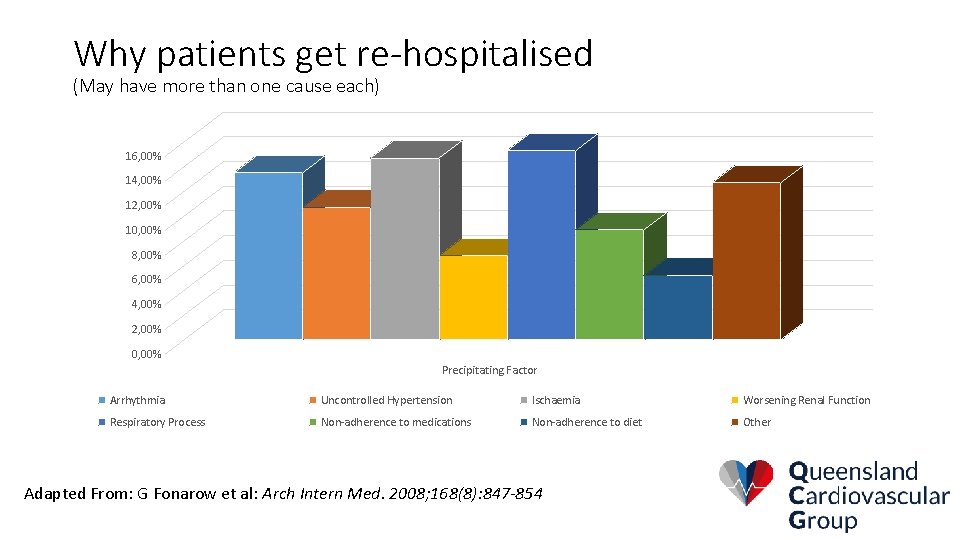

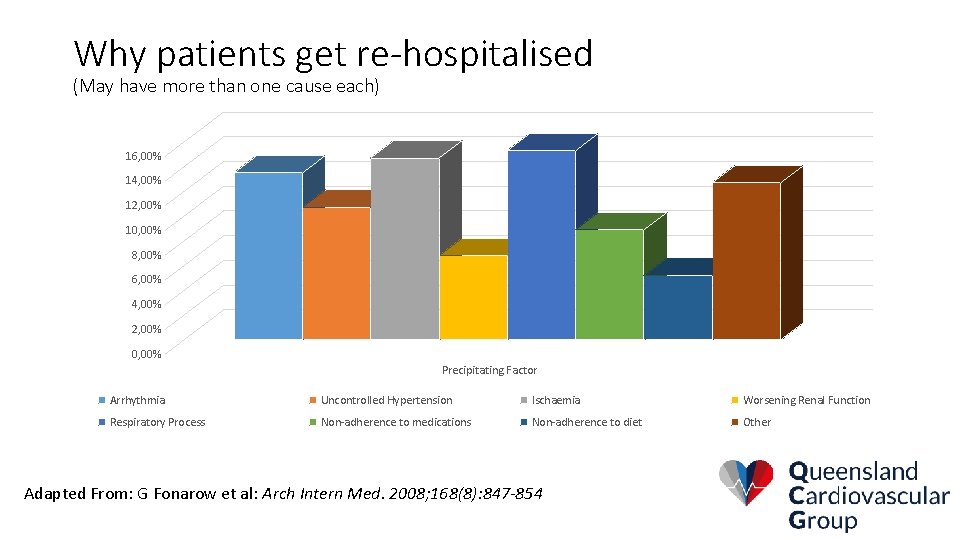

Why patients get re-hospitalised (May have more than one cause each) 16, 00% 14, 00% 12, 00% 10, 00% 8, 00% 6, 00% 4, 00% 2, 00% 0, 00% Precipitating Factor Arrhythmia Uncontrolled Hypertension Ischaemia Worsening Renal Function Respiratory Process Non-adherence to medications Non-adherence to diet Other Adapted From: G Fonarow et al: Arch Intern Med. 2008; 168(8): 847 -854

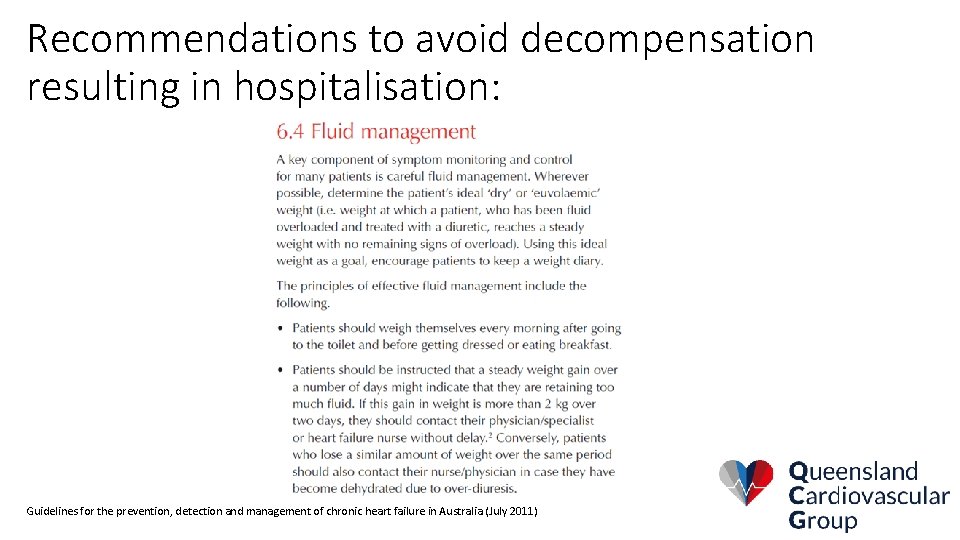

Recommendations to avoid decompensation resulting in hospitalisation: Guidelines for the prevention, detection and management of chronic heart failure in Australia (July 2011)

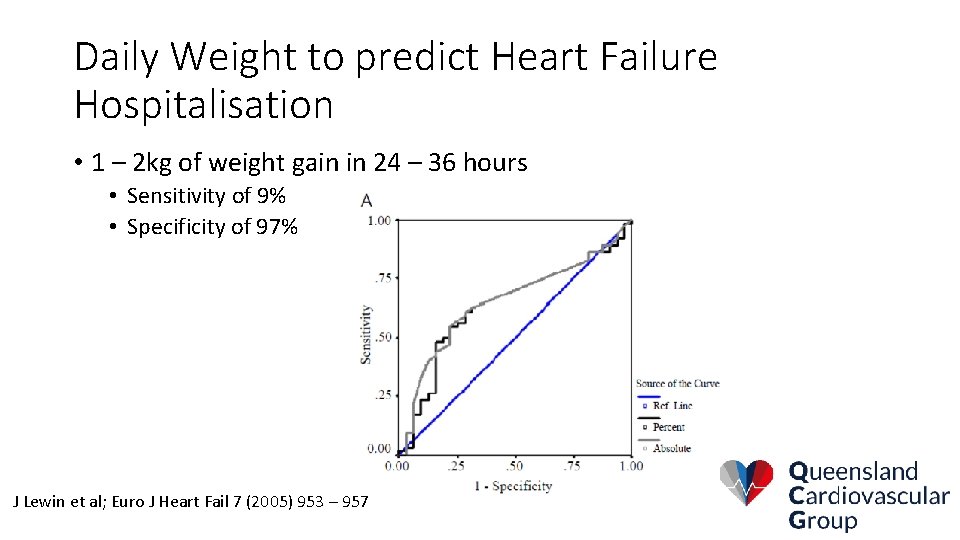

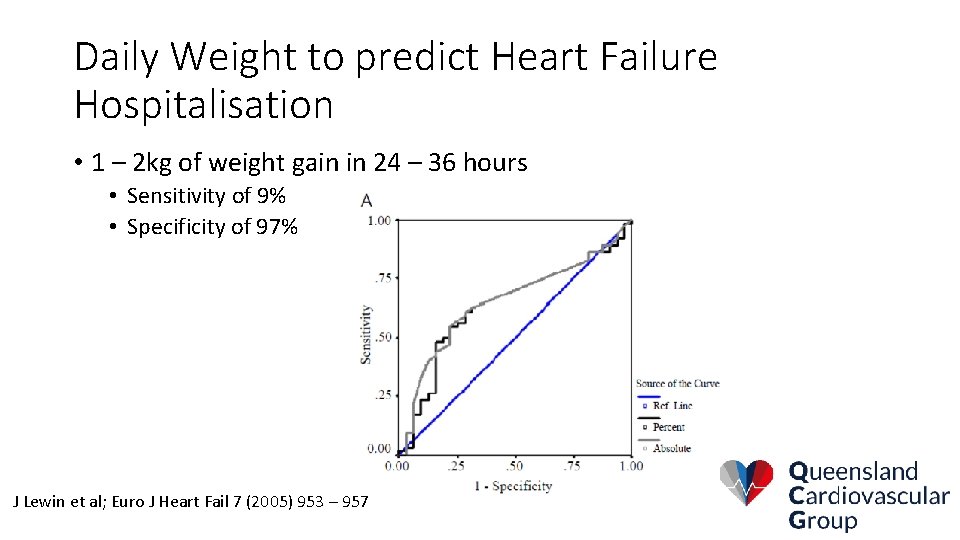

Daily Weight to predict Heart Failure Hospitalisation • 1 – 2 kg of weight gain in 24 – 36 hours • Sensitivity of 9% • Specificity of 97% J Lewin et al; Euro J Heart Fail 7 (2005) 953 – 957

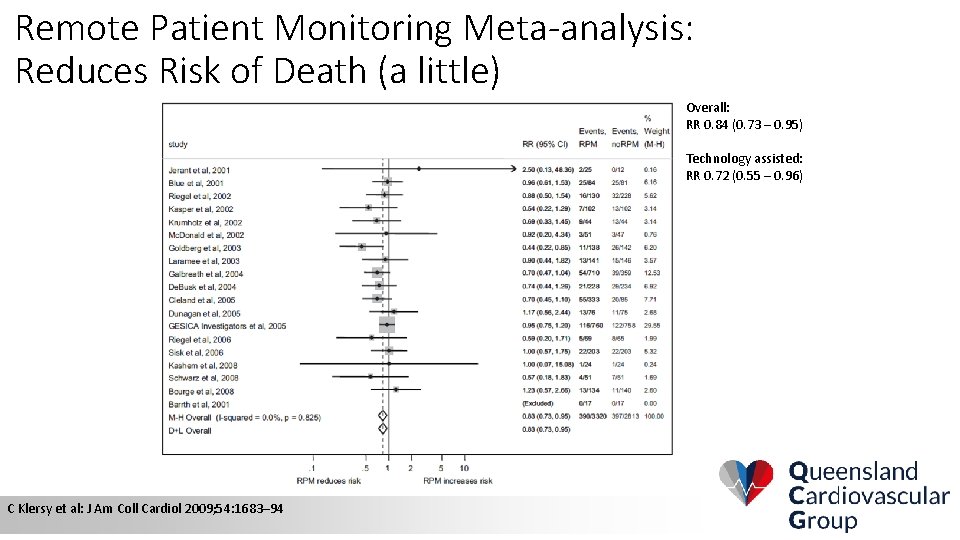

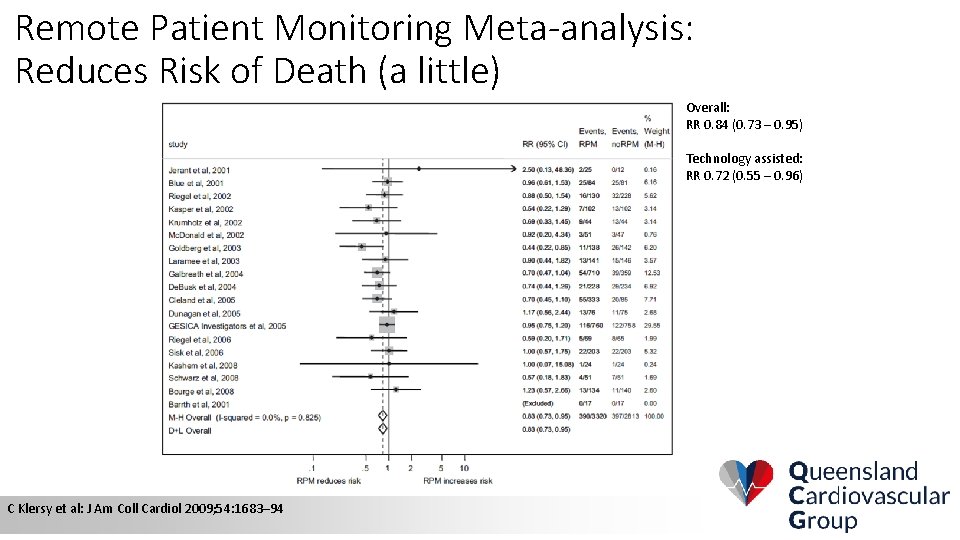

Remote Patient Monitoring Meta-analysis: Reduces Risk of Death (a little) Overall: RR 0. 84 (0. 73 – 0. 95) Technology assisted: RR 0. 72 (0. 55 – 0. 96) C Klersy et al: J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54: 1683– 94

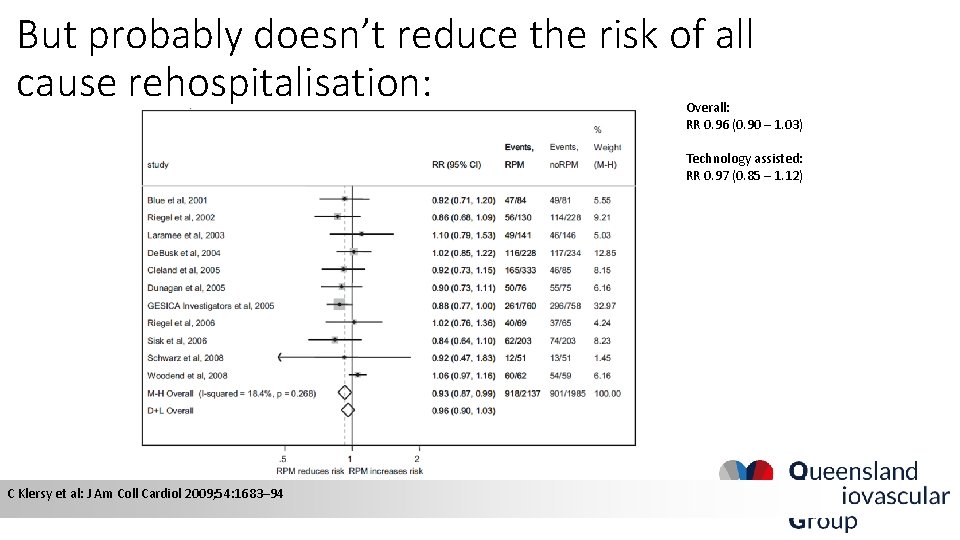

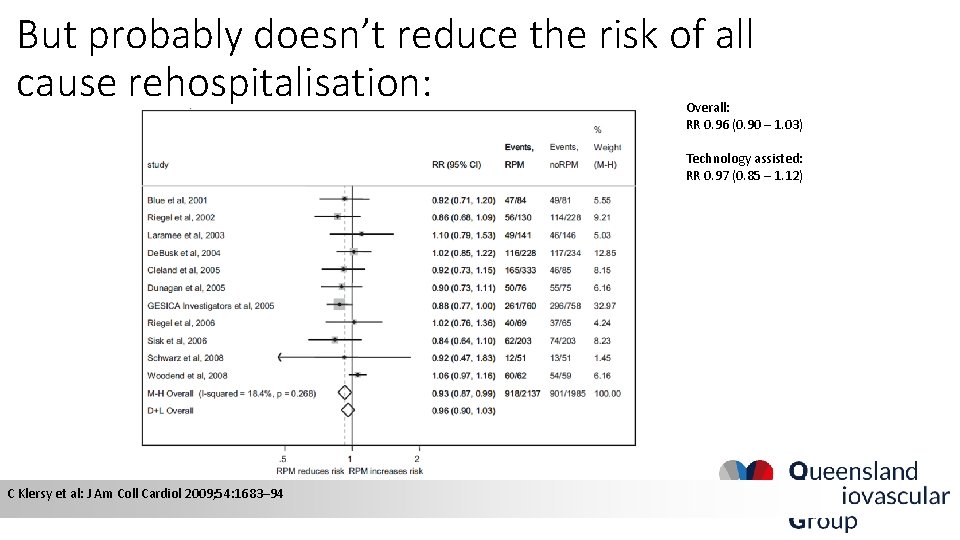

But probably doesn’t reduce the risk of all cause rehospitalisation: Overall: RR 0. 96 (0. 90 – 1. 03) Technology assisted: RR 0. 97 (0. 85 – 1. 12) C Klersy et al: J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54: 1683– 94

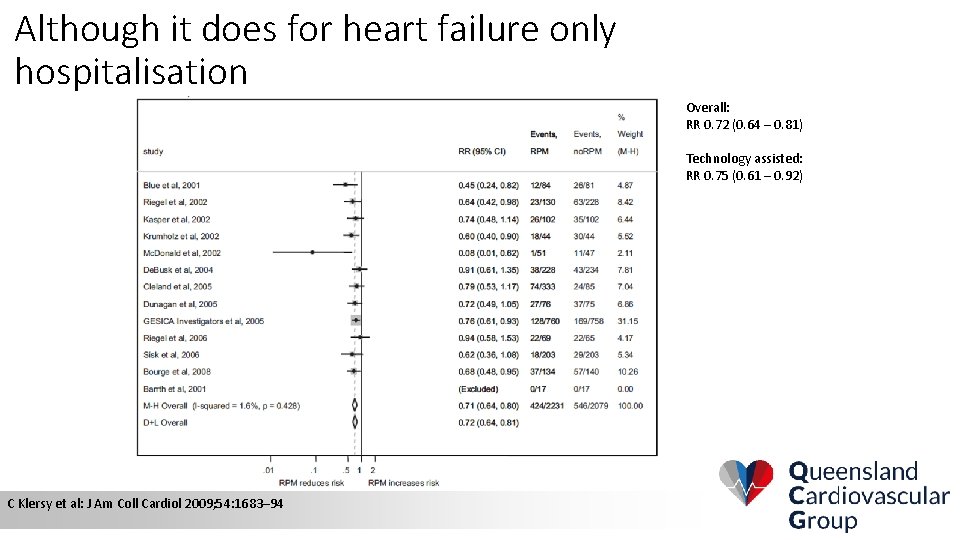

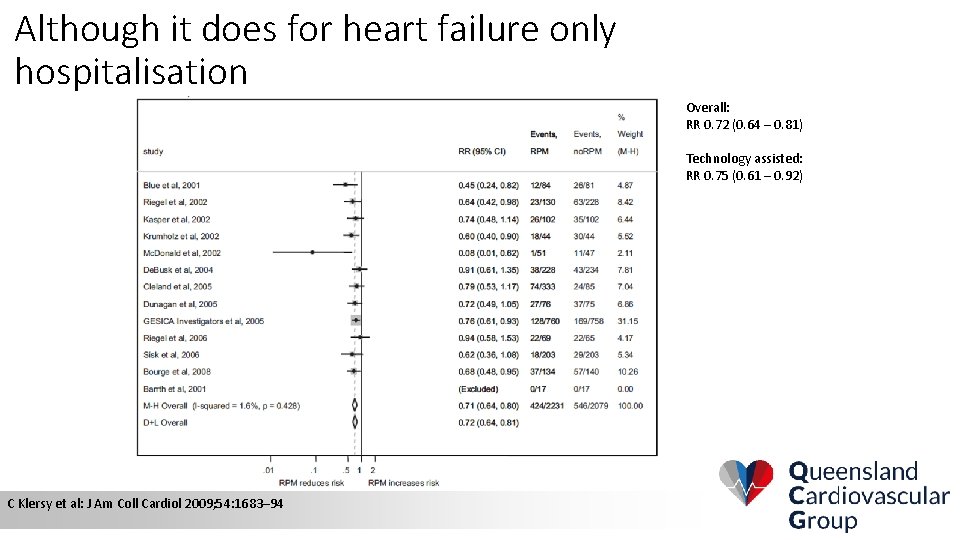

Although it does for heart failure only hospitalisation Overall: RR 0. 72 (0. 64 – 0. 81) Technology assisted: RR 0. 75 (0. 61 – 0. 92) C Klersy et al: J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54: 1683– 94

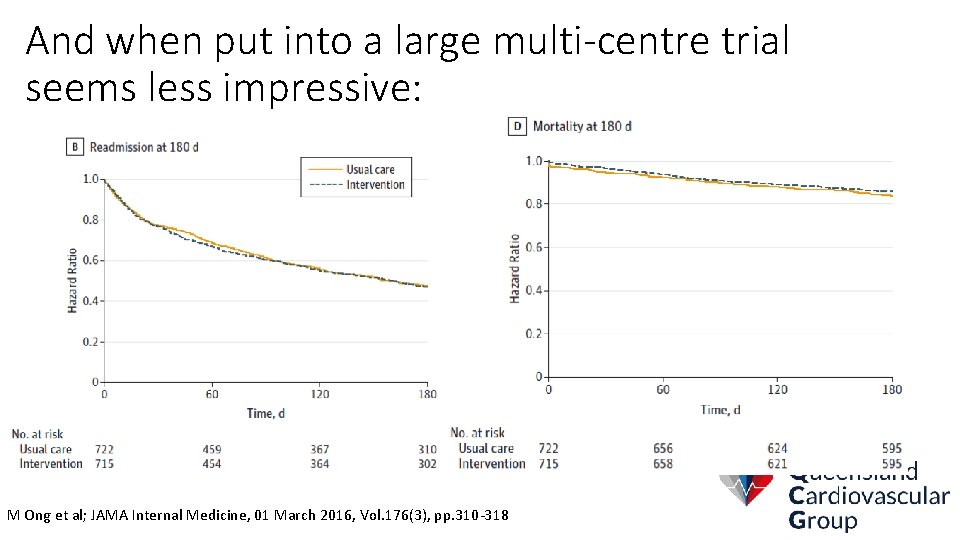

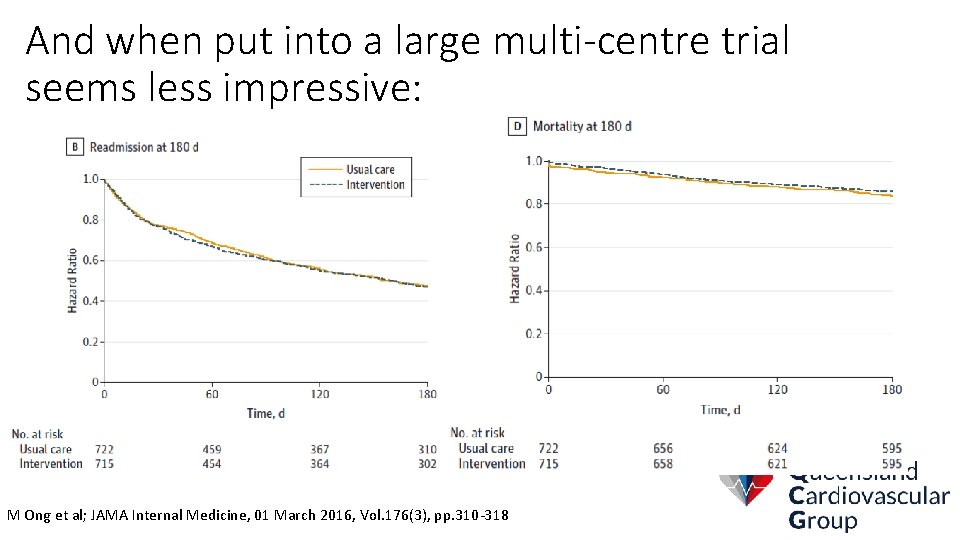

And when put into a large multi-centre trial seems less impressive: M Ong et al; JAMA Internal Medicine, 01 March 2016, Vol. 176(3), pp. 310 -318

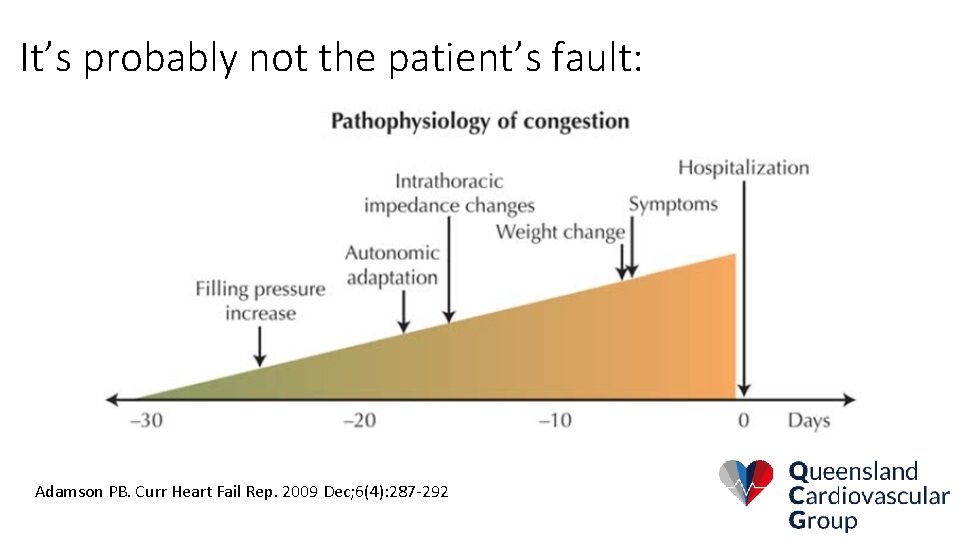

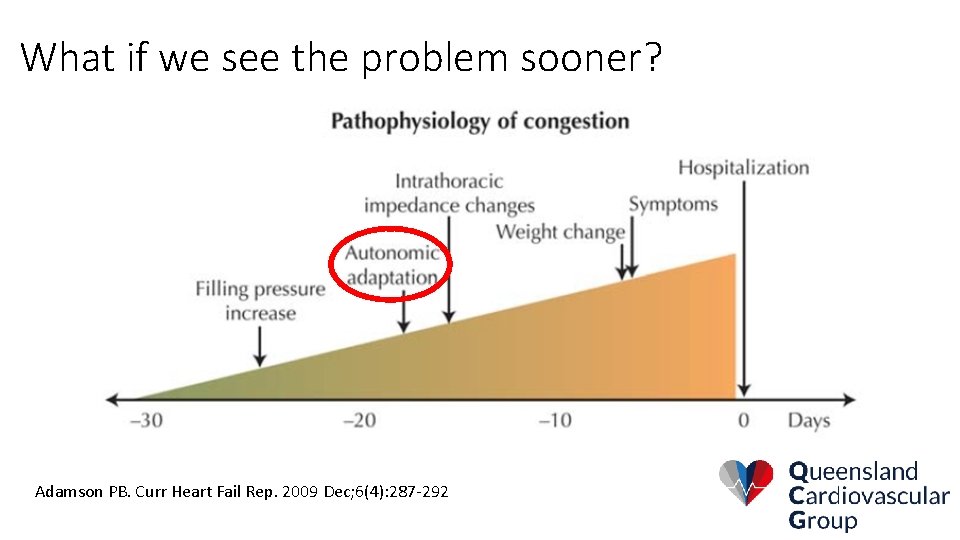

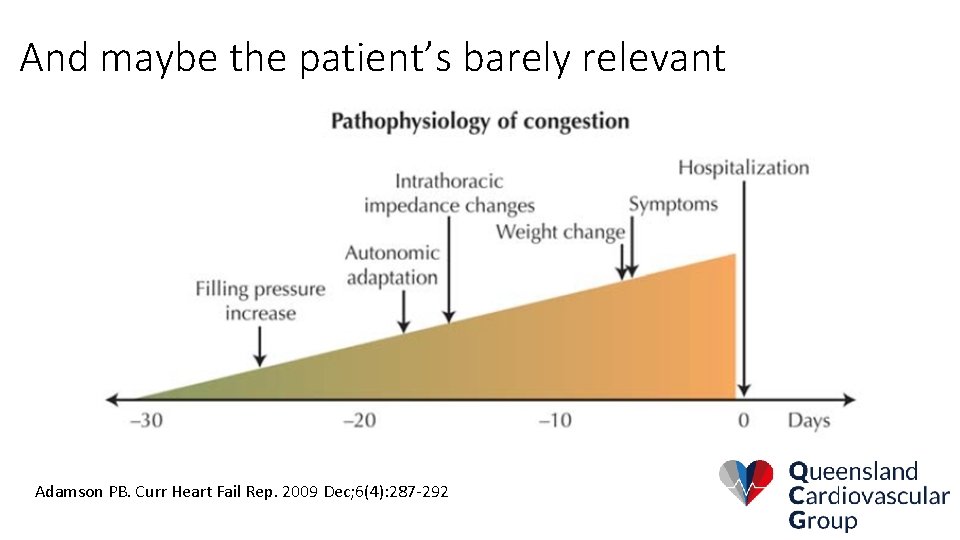

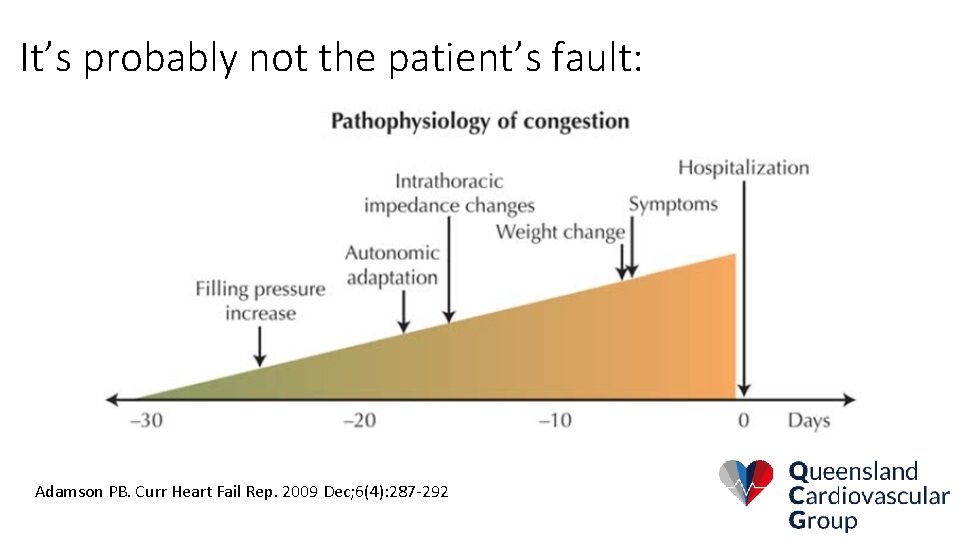

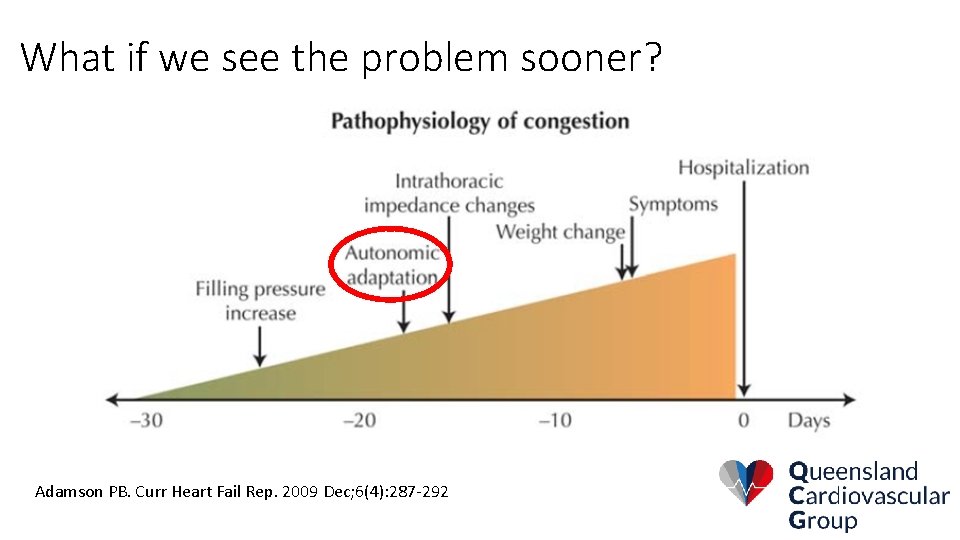

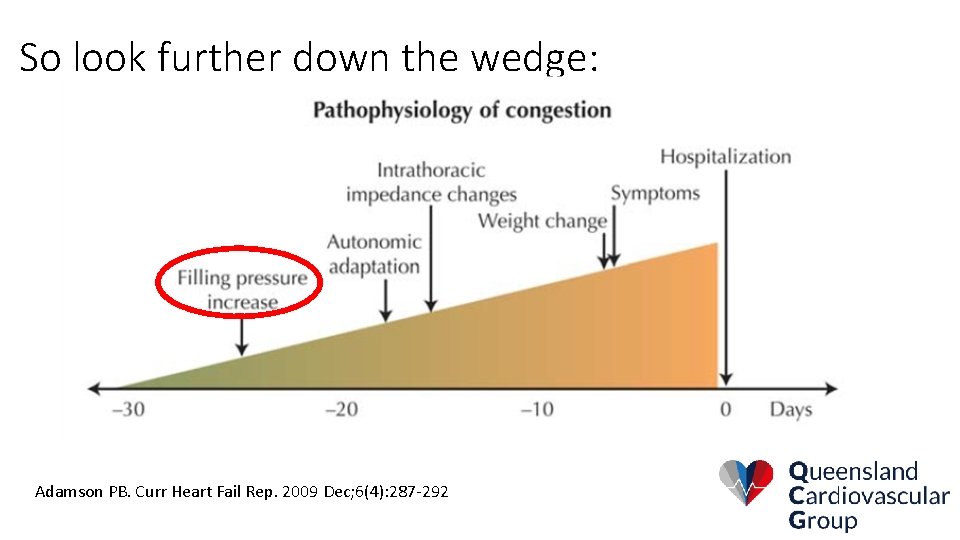

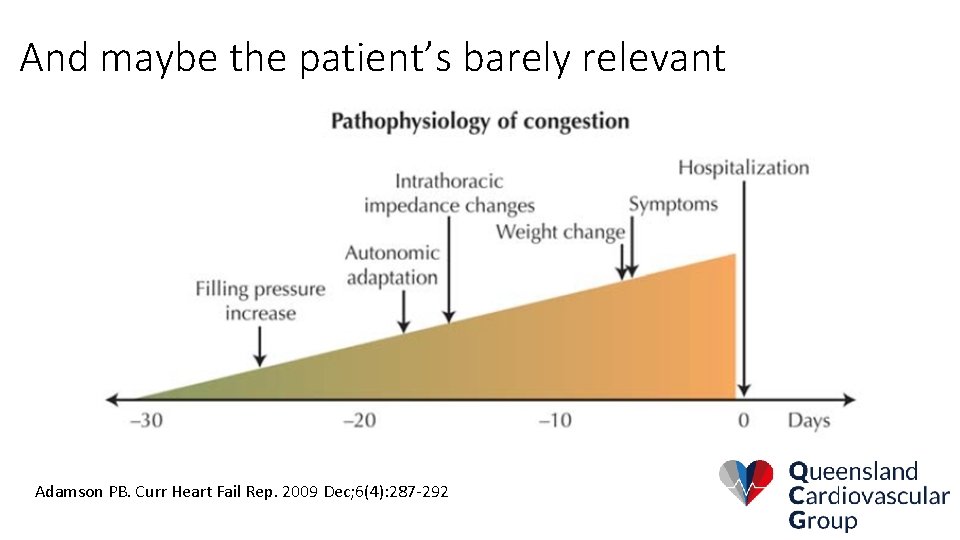

It’s probably not the patient’s fault: Adamson PB. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2009 Dec; 6(4): 287 -292

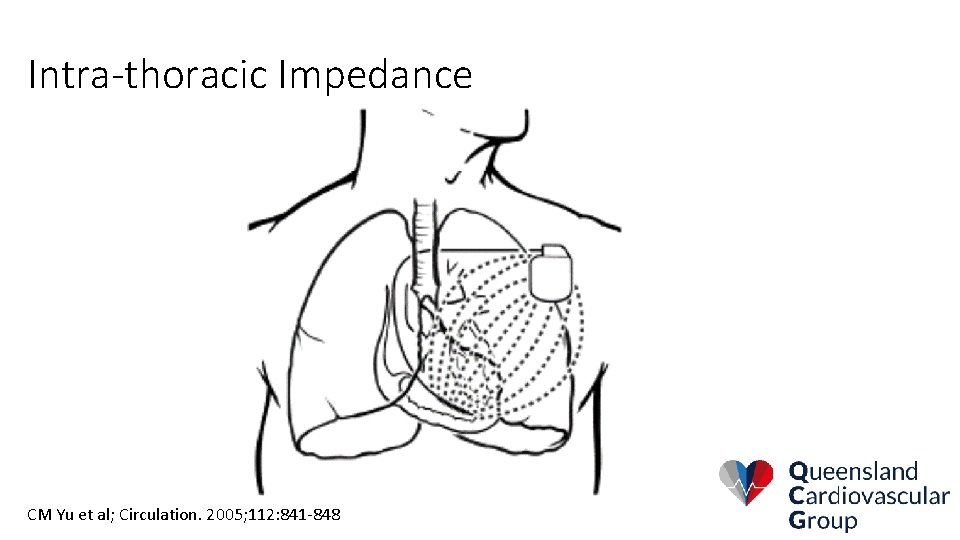

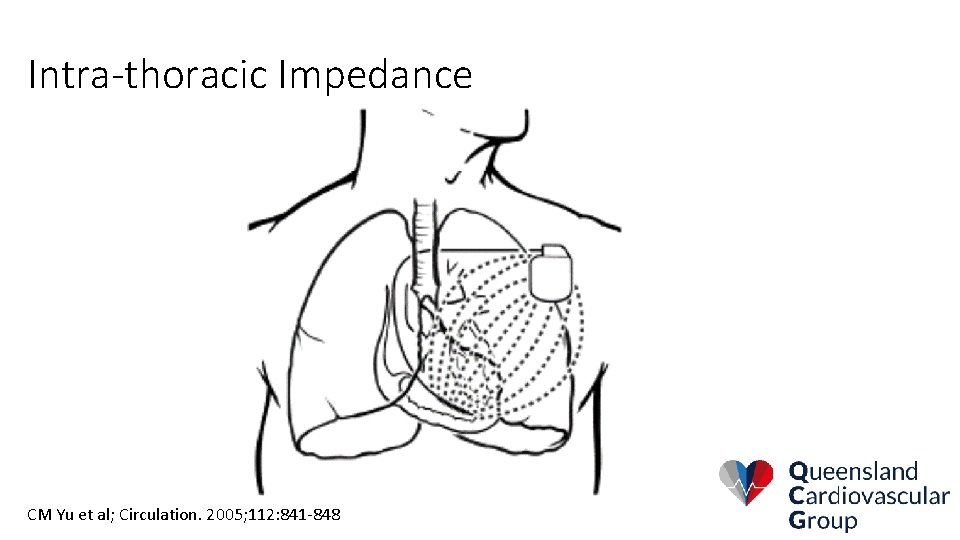

Intra-thoracic Impedance CM Yu et al; Circulation. 2005; 112: 841 -848

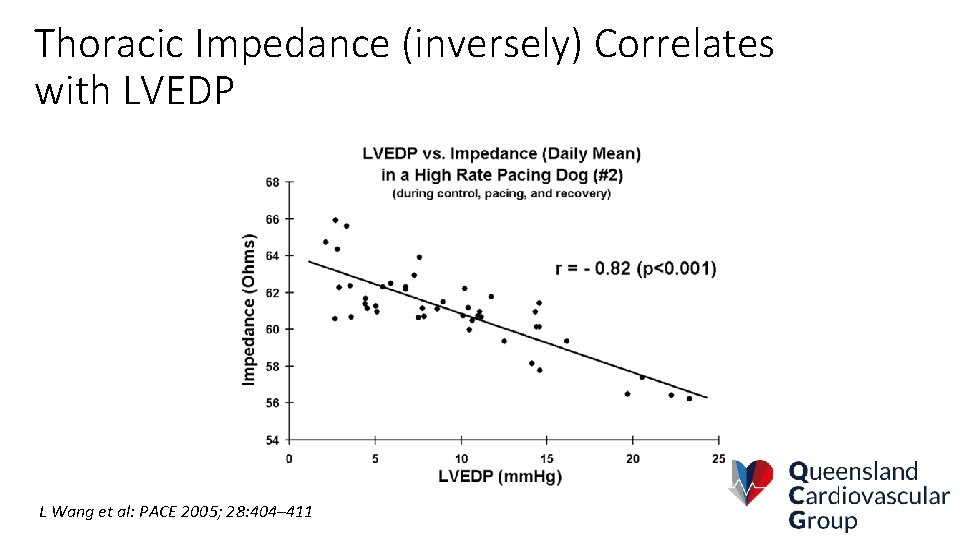

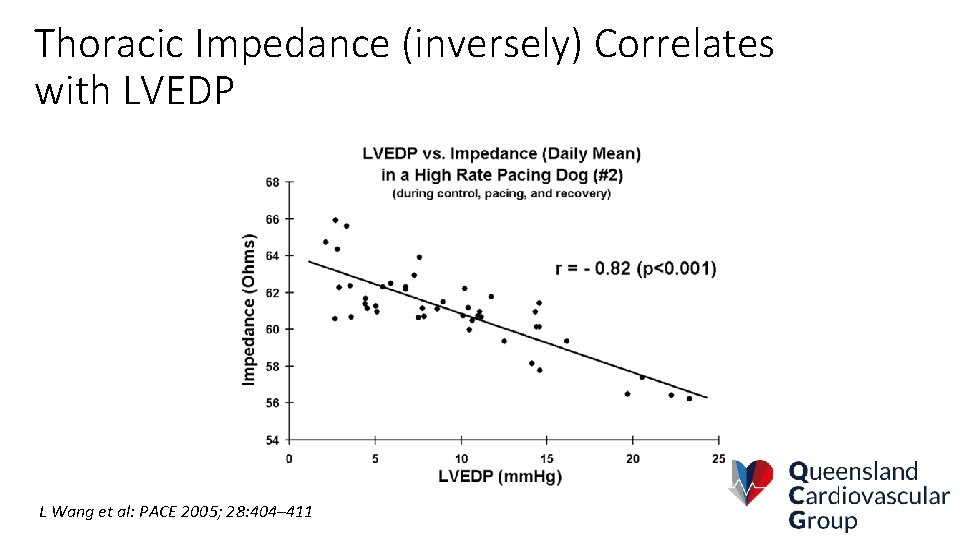

Thoracic Impedance (inversely) Correlates with LVEDP L Wang et al: PACE 2005; 28: 404– 411

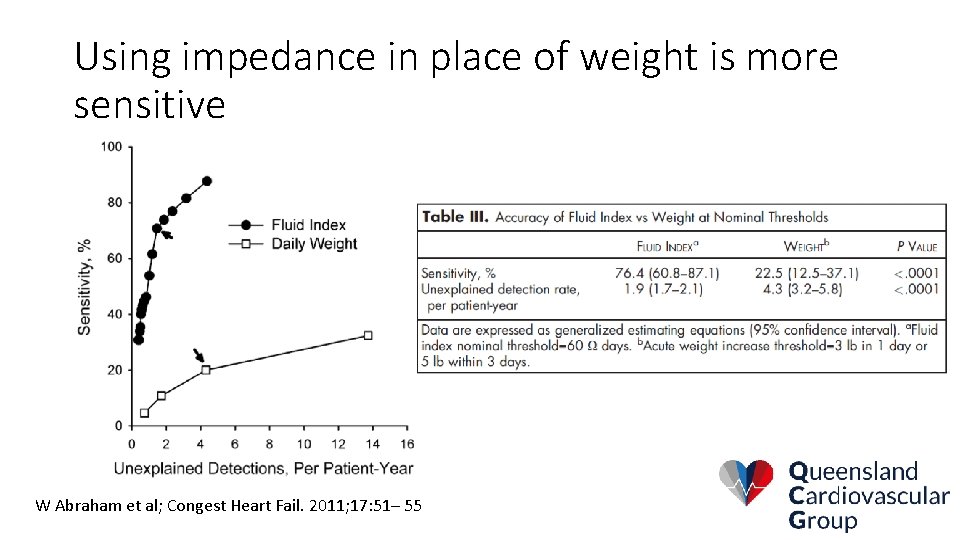

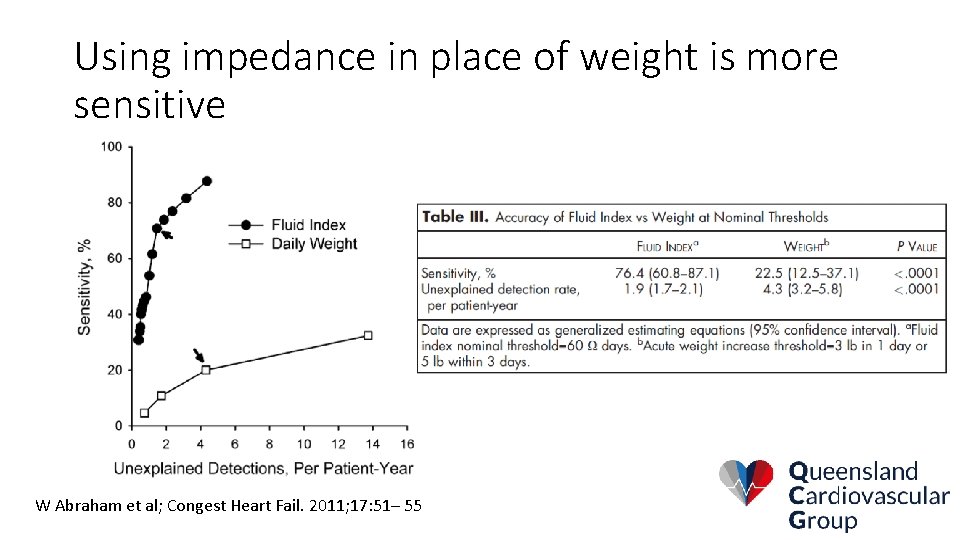

Using impedance in place of weight is more sensitive W Abraham et al; Congest Heart Fail. 2011; 17: 51– 55

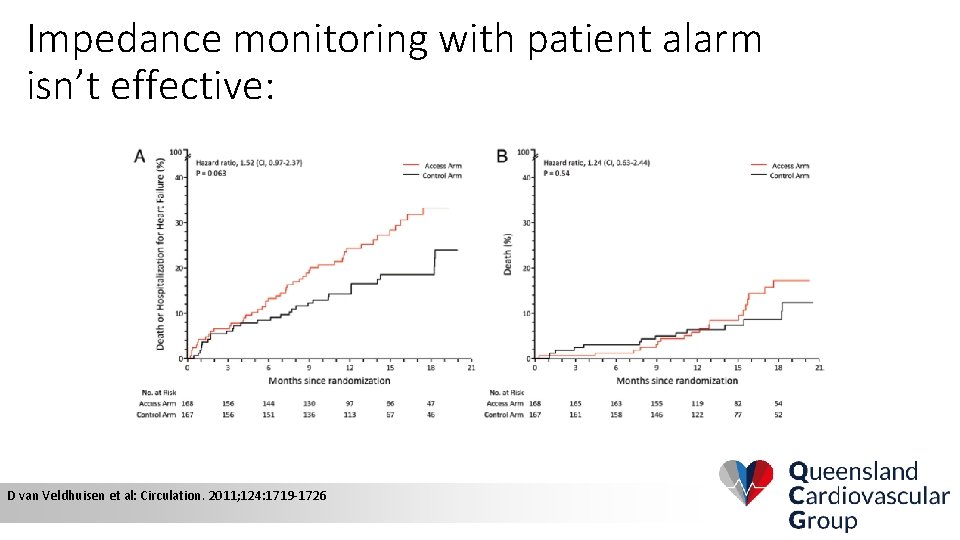

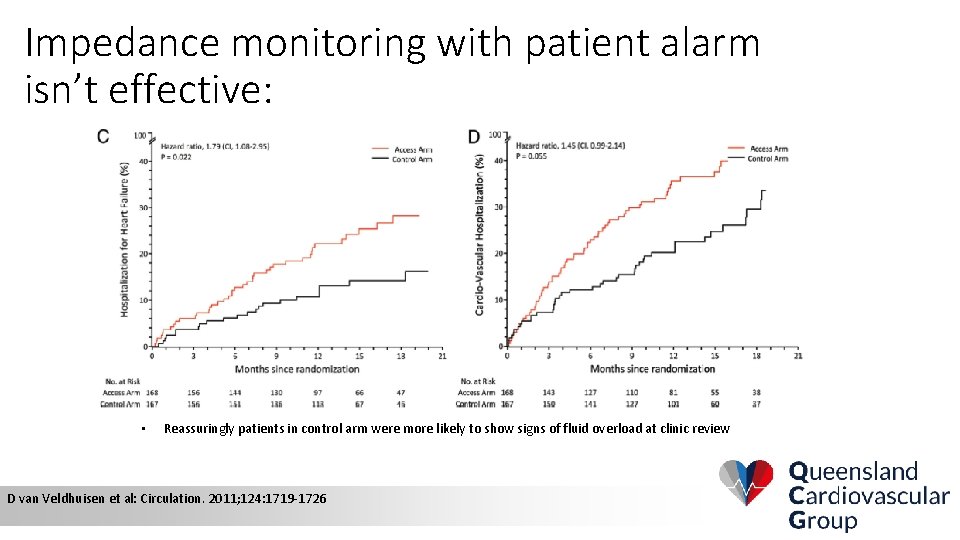

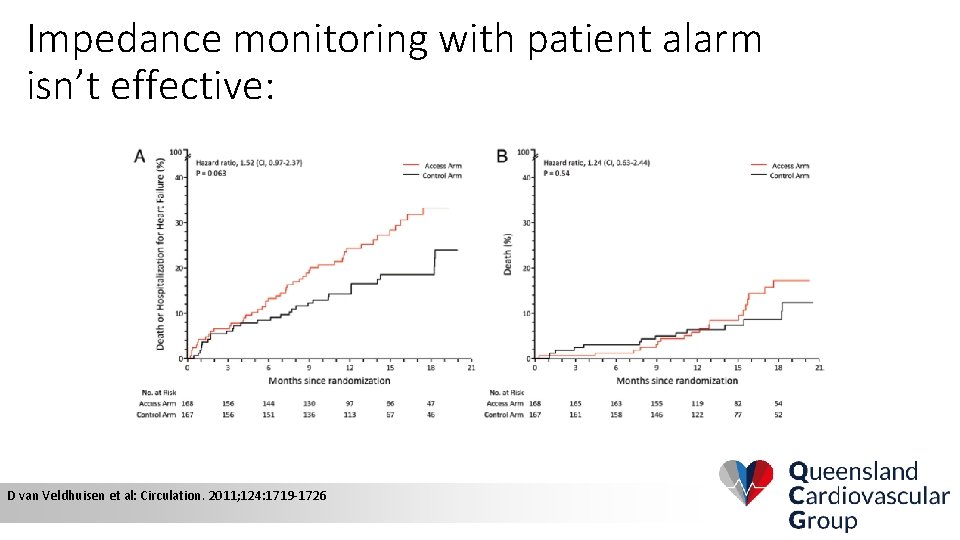

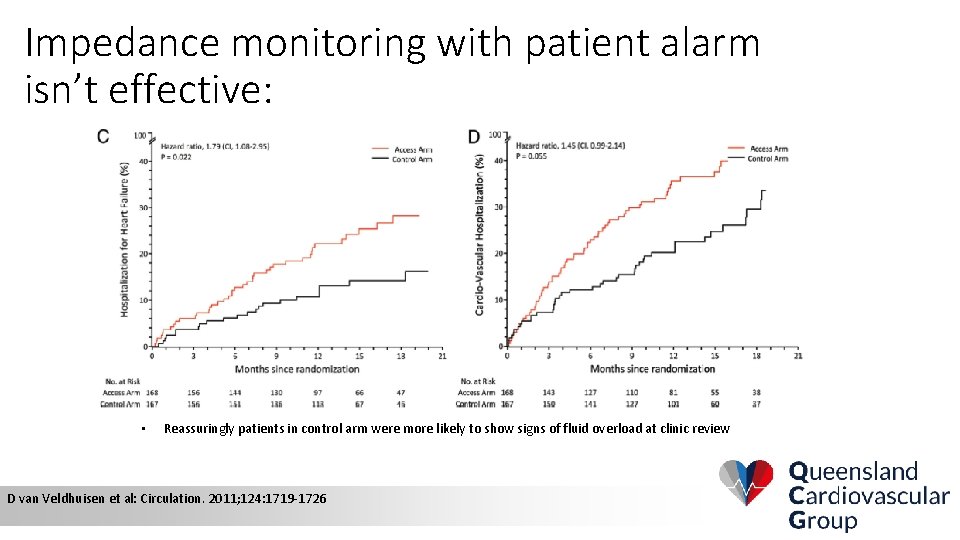

Impedance monitoring with patient alarm isn’t effective: D van Veldhuisen et al: Circulation. 2011; 124: 1719 -1726

Impedance monitoring with patient alarm isn’t effective: • Reassuringly patients in control arm were more likely to show signs of fluid overload at clinic review D van Veldhuisen et al: Circulation. 2011; 124: 1719 -1726

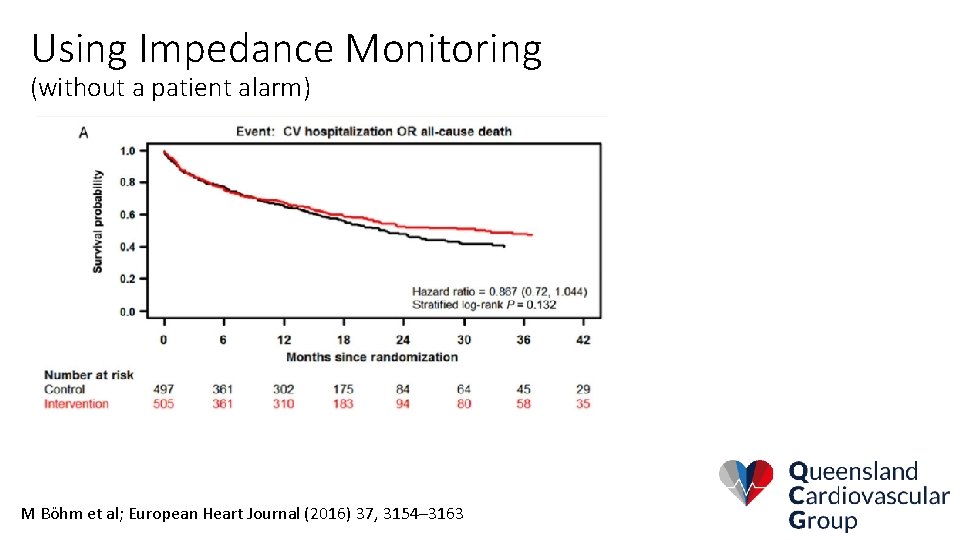

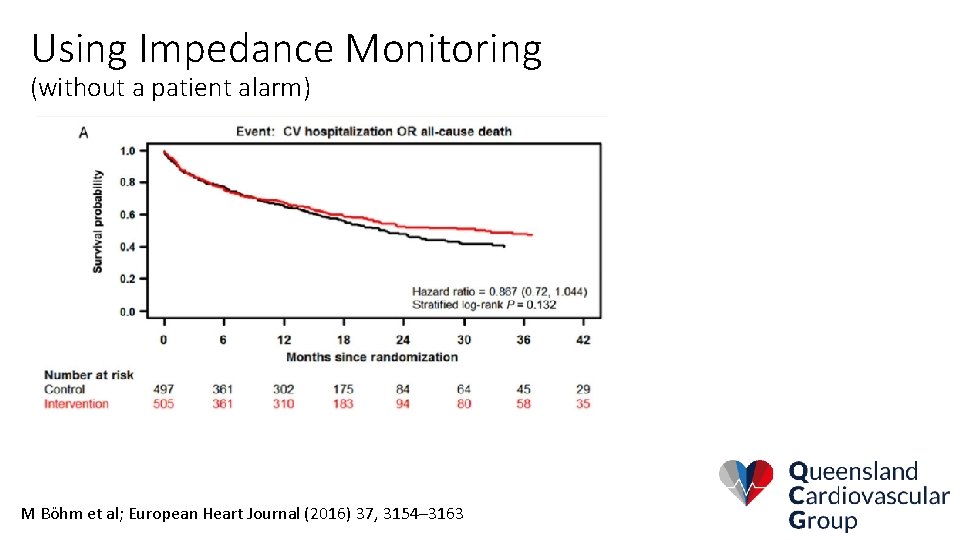

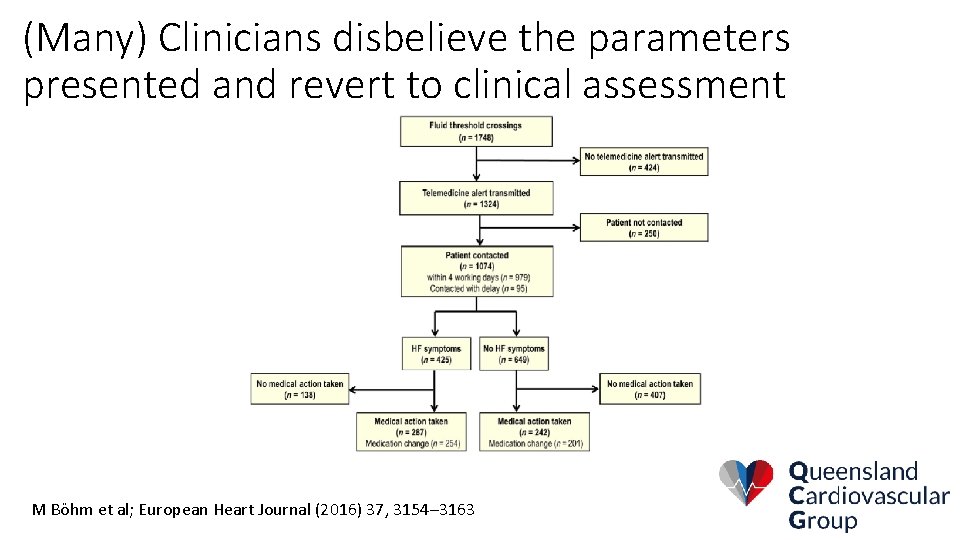

Using Impedance Monitoring (without a patient alarm) M Böhm et al; European Heart Journal (2016) 37, 3154– 3163

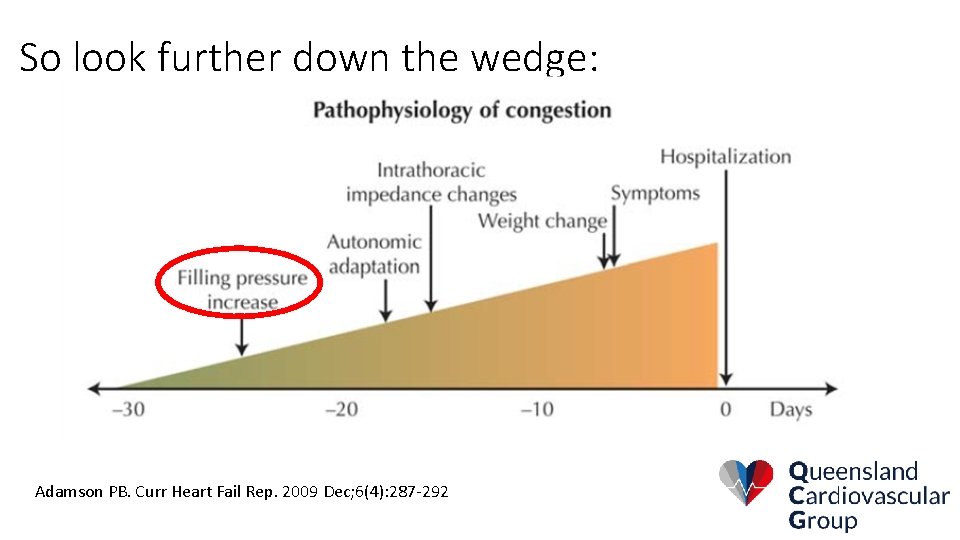

What if we see the problem sooner? Adamson PB. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2009 Dec; 6(4): 287 -292

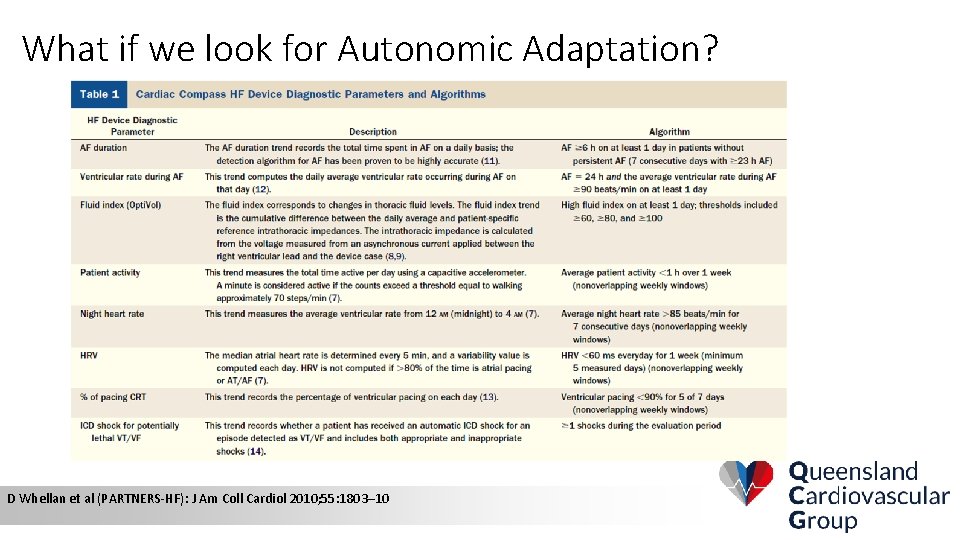

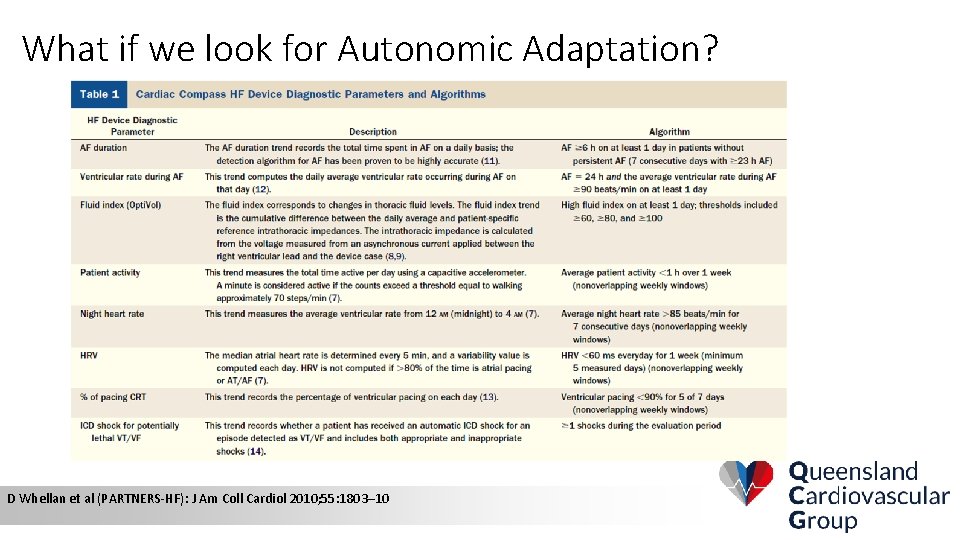

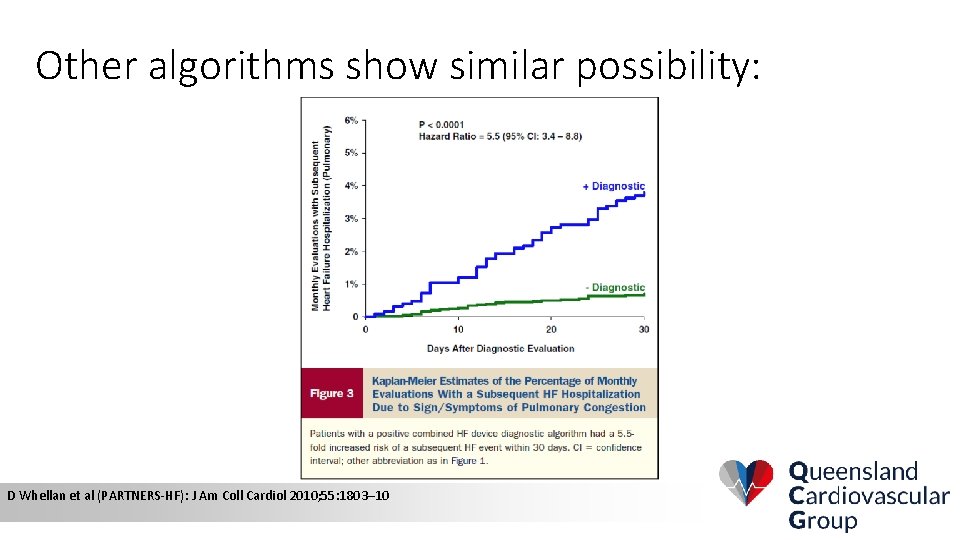

What if we look for Autonomic Adaptation? D Whellan et al (PARTNERS-HF): J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 55: 1803– 10

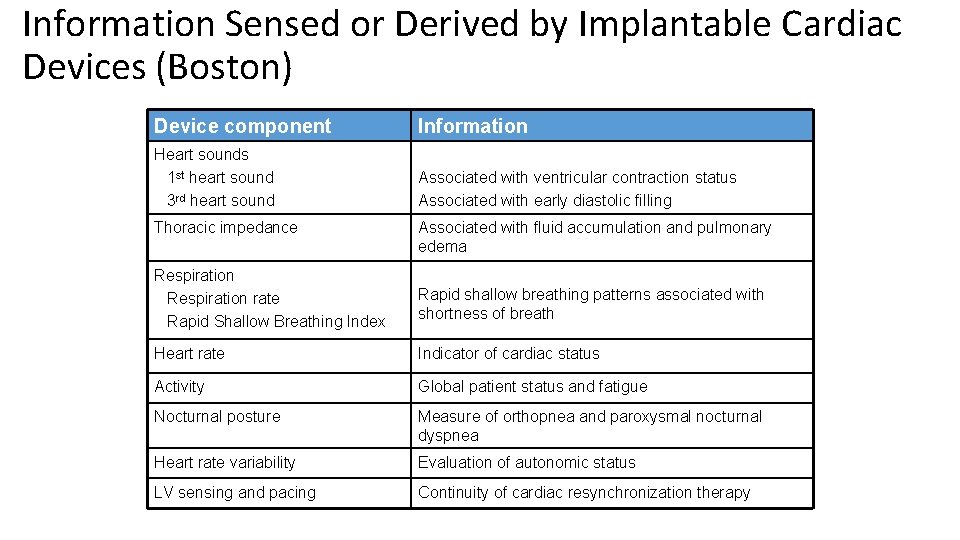

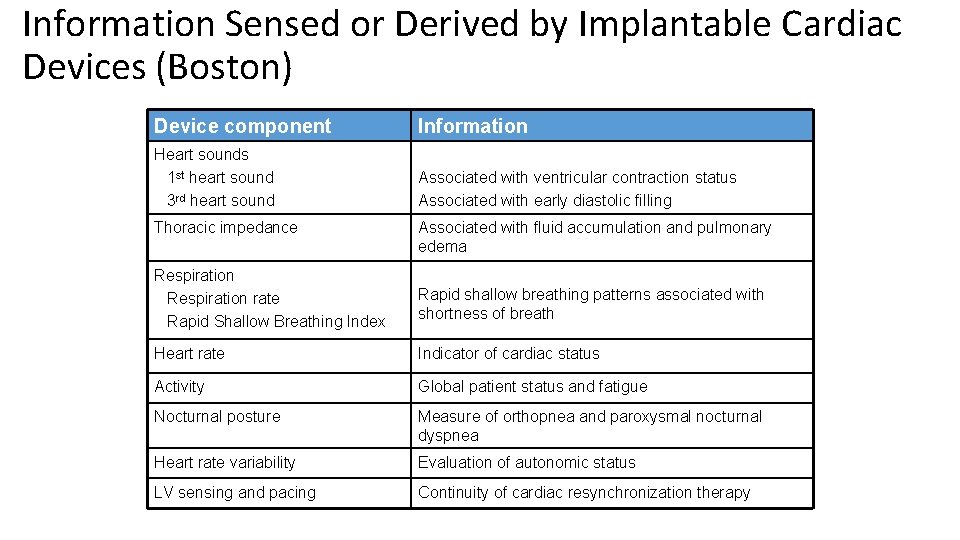

Information Sensed or Derived by Implantable Cardiac Devices (Boston) Device component Information Heart sounds 1 st heart sound 3 rd heart sound Associated with ventricular contraction status Associated with early diastolic filling Thoracic impedance Associated with fluid accumulation and pulmonary edema Respiration rate Rapid Shallow Breathing Index Rapid shallow breathing patterns associated with shortness of breath Heart rate Indicator of cardiac status Activity Global patient status and fatigue Nocturnal posture Measure of orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea Heart rate variability Evaluation of autonomic status LV sensing and pacing Continuity of cardiac resynchronization therapy

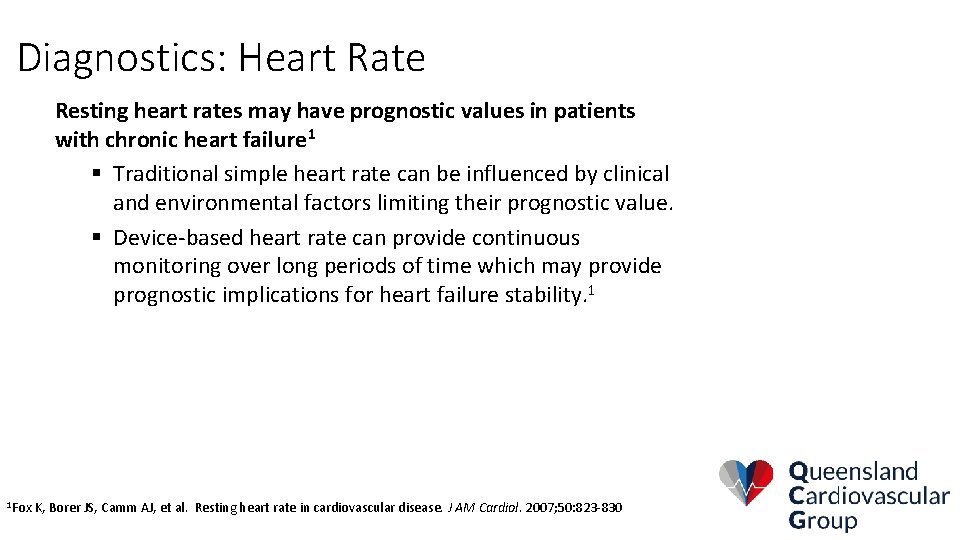

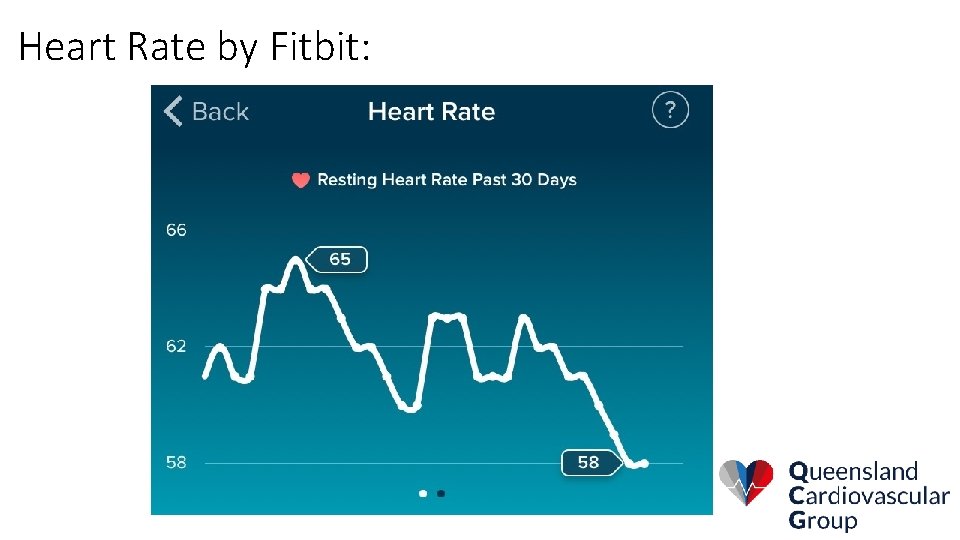

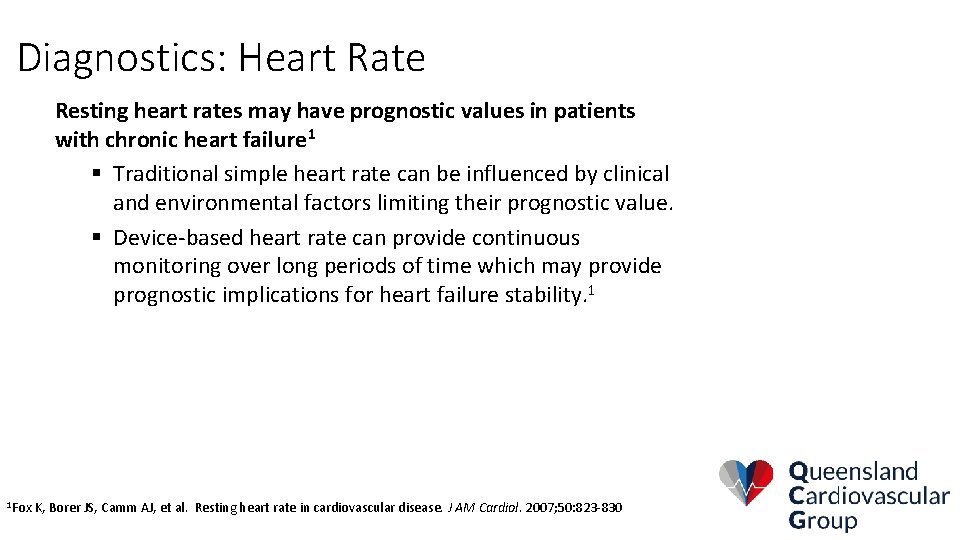

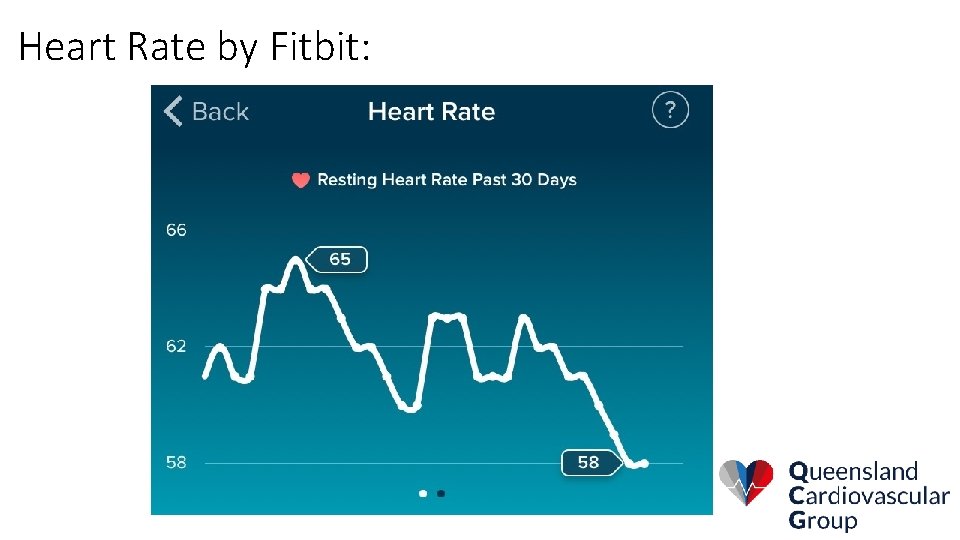

Diagnostics: Heart Rate Resting heart rates may have prognostic values in patients with chronic heart failure 1 § Traditional simple heart rate can be influenced by clinical and environmental factors limiting their prognostic value. § Device-based heart rate can provide continuous monitoring over long periods of time which may provide prognostic implications for heart failure stability. 1 1 Fox K, Borer JS, Camm AJ, et al. Resting heart rate in cardiovascular disease. J AM Cardiol. 2007; 50: 823 -830

Heart Rate by Fitbit:

Diagnostic: Arrhythmia Burden Atrial Rhythms § Hours spent in Atrial Fibrillation (atrial burden) § Ventricular rate during AT/AF § Paroxysmal AF events Clinical Implications § AT/AF episodes in heart failure associated with poor prognosis and mortality 1 § AF can exacerbate HF 2 • Loss of atrial contribution to cardiac output • Nonphysiologic HR response • Irregular episodes of ventricular filling • Increased risk of thromboembolism 1 Cesario, D; Powell, B; Cao, M et al. ACC 2011; WG et al, NEJM 2004: 351: 2437 -2440; 2 Stevenson

Diagnostic: Arrhythmia Burden Ventricular Rhythms § § Allows continuous assessment of ventricular response to atrial fibrillation Continuous assessment of ventricular rate during activities of daily living Documents the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias Records appropriate and inappropriate shock Clinical Implications § § § Is this the cause of new symptoms? Is there an increase in frequency? Have they received therapy without knowing? Has therapy been appropriate? What is the cause of the ventricular or increased ventricular rhythm?

Diagnostics: Biventricular Pacing Percent Pacing The goal of CRT is to maximize resynchronization through a high rate of biventricular pacing. Preferred percentage of pacing >95%1 § Influence medical therapy an follow-up § High percentage of biventricular pacing in patients with a CRT device was associated with improved prognosis. 2 Percent pacing can be limited by patients with: Persistent rapid ventricular response to atrial fibrillation § Or frequent ventricular premature contraction § 1 Wilkoff, BL et al. Dual-chamber pacing or ventricular backup pacing in patients with an ICD, JAMA 2002; 288: 3115 -3123 David et al. Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy and the Relationship of Percent Biventricular Pacing to Symptoms and Survival, Heart Rhythm, doi: 10. 1016/j. hrthm. 2011. 04. 015 2 Hayes,

The problem with 10+ parameters per patient per day: • Noise +++

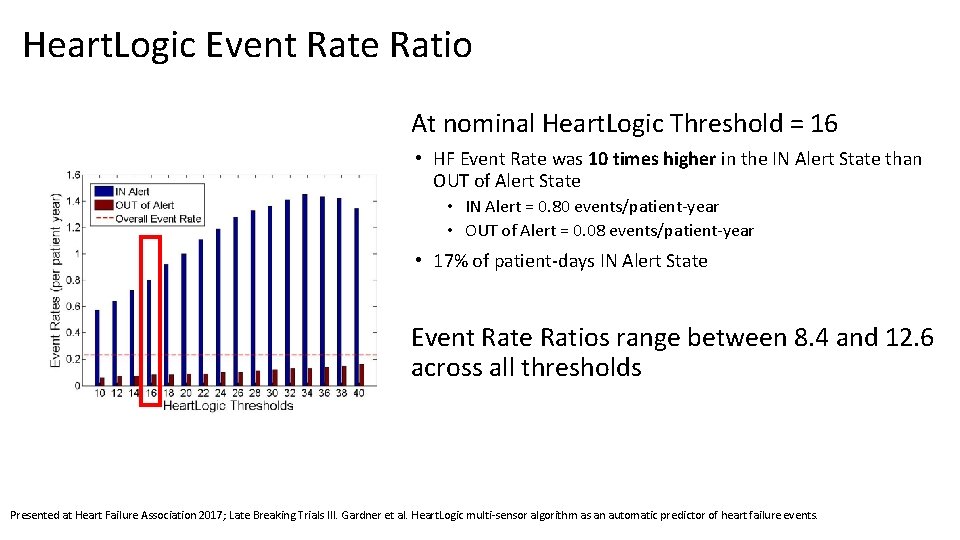

Multi. SENSE Trial: • Heart. Logic Index will be a weighted calculation of the patient’s change in 5 sensor trends calculated daily: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Accelerometer-based first and third heart sounds Thoracic impedance Respiration rate and volume Heart rate Patient activity • The Heart. Logic* Alert Threshold will be programmable, with nominal at 16

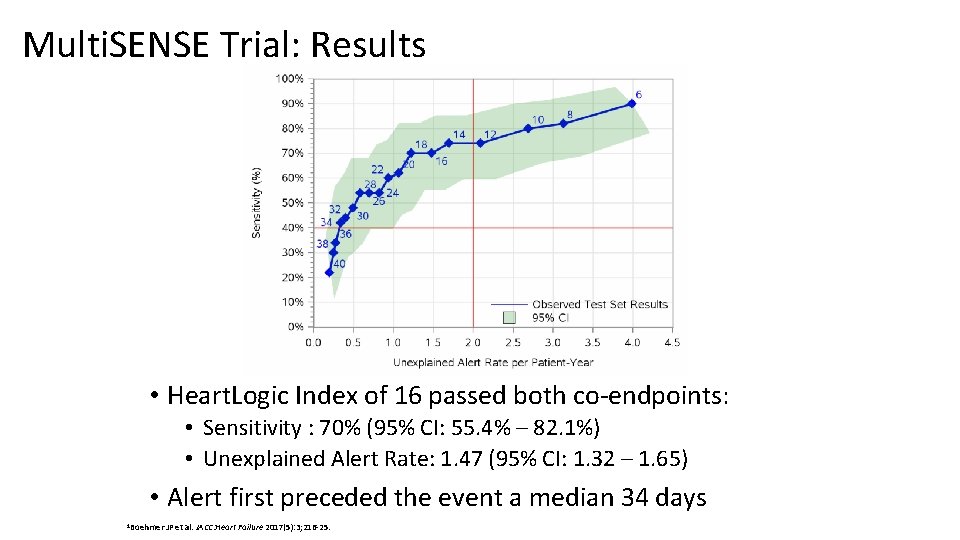

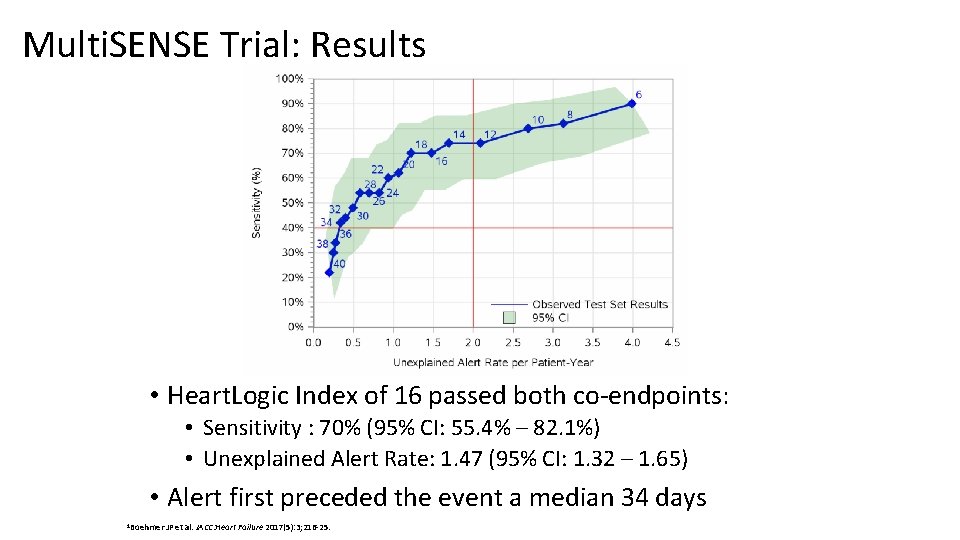

Multi. SENSE Trial: Results • Heart. Logic Index of 16 passed both co-endpoints: • Sensitivity : 70% (95% CI: 55. 4% – 82. 1%) • Unexplained Alert Rate: 1. 47 (95% CI: 1. 32 – 1. 65) • Alert first preceded the event a median 34 days 1 Boehmer JP et al. JACC: Heart Failure 2017(5): 3; 216 -25.

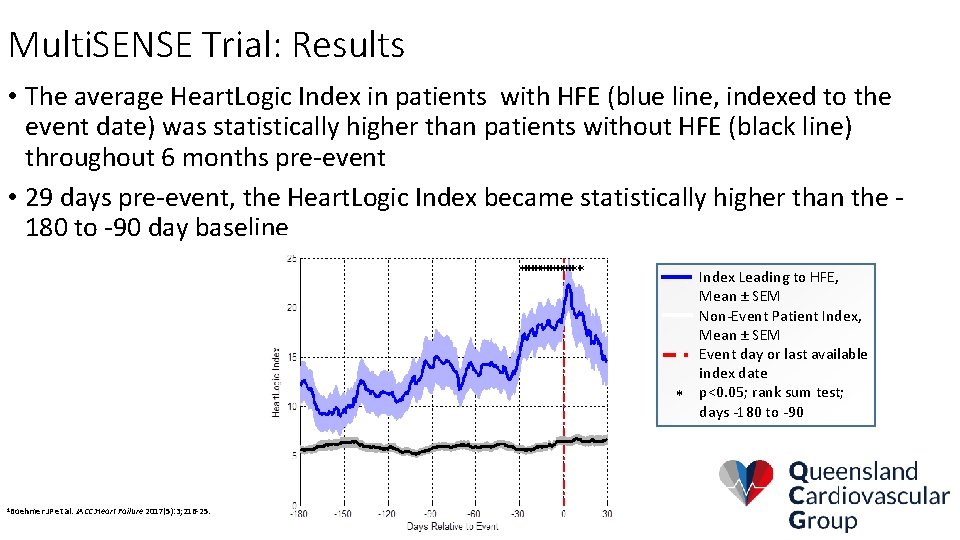

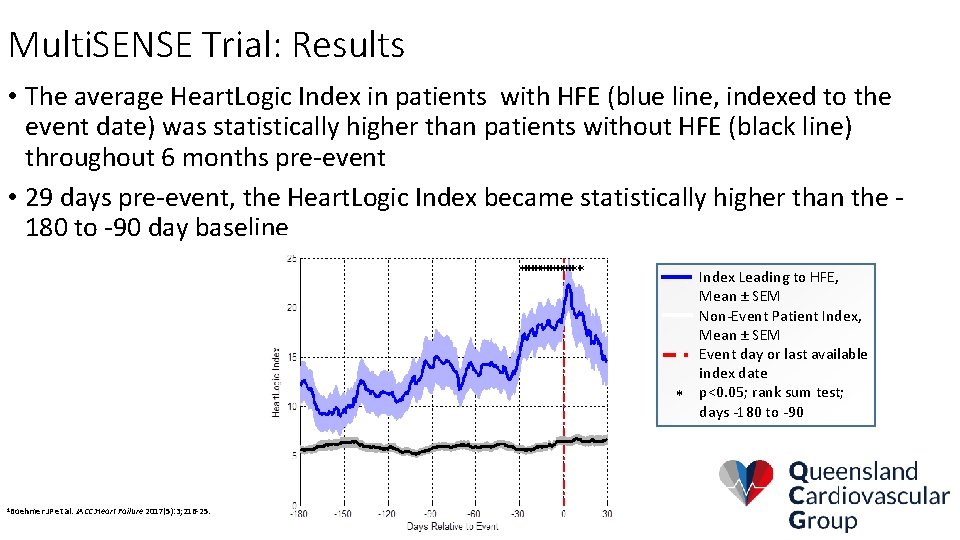

Multi. SENSE Trial: Results • The average Heart. Logic Index in patients with HFE (blue line, indexed to the event date) was statistically higher than patients without HFE (black line) throughout 6 months pre-event • 29 days pre-event, the Heart. Logic Index became statistically higher than the 180 to -90 day baseline Index Leading to HFE, Mean ± SEM Non-Event Patient Index, Mean ± SEM Event day or last available index date * p<0. 05; rank sum test; days -180 to -90 1 Boehmer JP et al. JACC: Heart Failure 2017(5): 3; 216 -25.

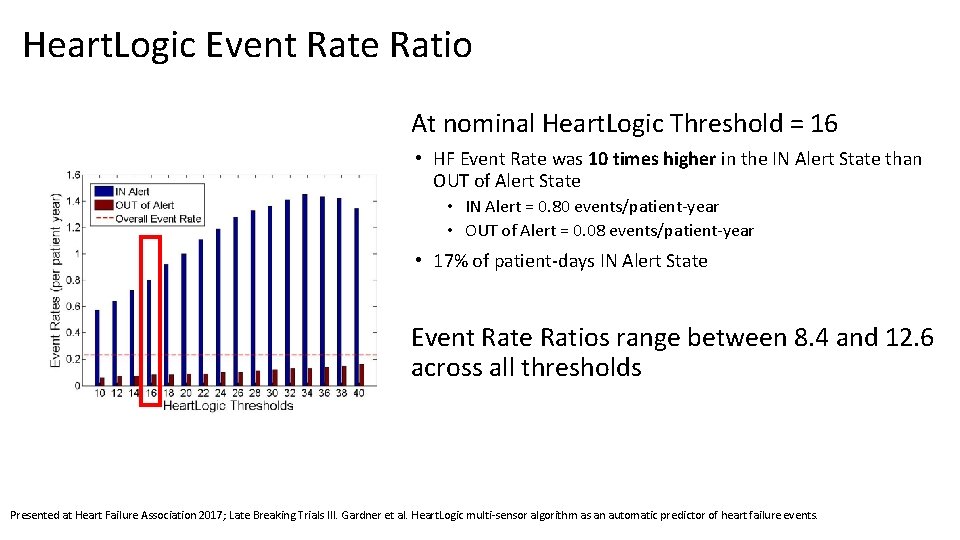

Heart. Logic Event Rate Ratio At nominal Heart. Logic Threshold = 16 • HF Event Rate was 10 times higher in the IN Alert State than OUT of Alert State • IN Alert = 0. 80 events/patient-year • OUT of Alert = 0. 08 events/patient-year • 17% of patient-days IN Alert State Event Rate Ratios range between 8. 4 and 12. 6 across all thresholds Presented at Heart Failure Association 2017; Late Breaking Trials III. Gardner et al. Heart. Logic multi-sensor algorithm as an automatic predictor of heart failure events.

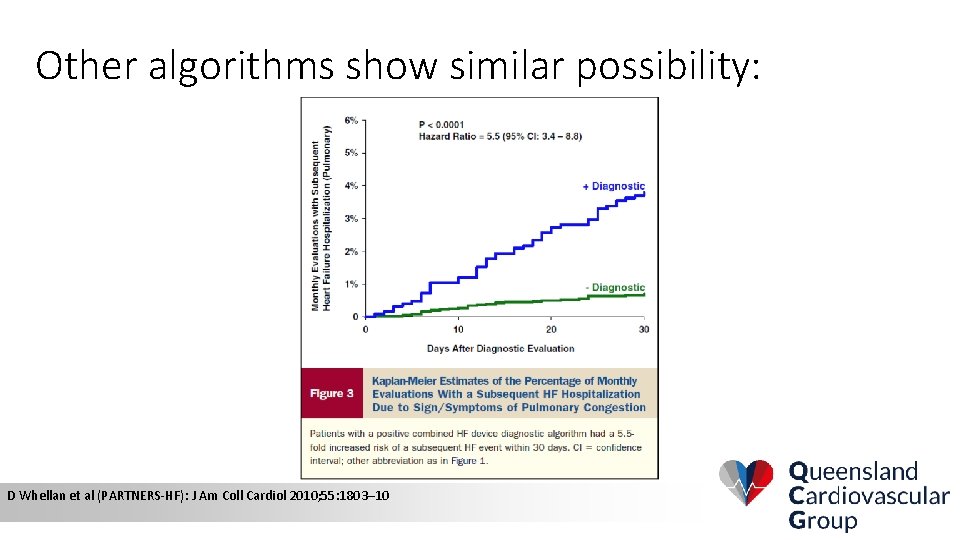

Other algorithms show similar possibility: D Whellan et al (PARTNERS-HF): J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 55: 1803– 10

• But there is no endpoint study for these derived multi-parameter tools • The triggering of an alert gives no clue as to what needs to be done

So look further down the wedge: Adamson PB. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2009 Dec; 6(4): 287 -292

Cardio. MEMS –

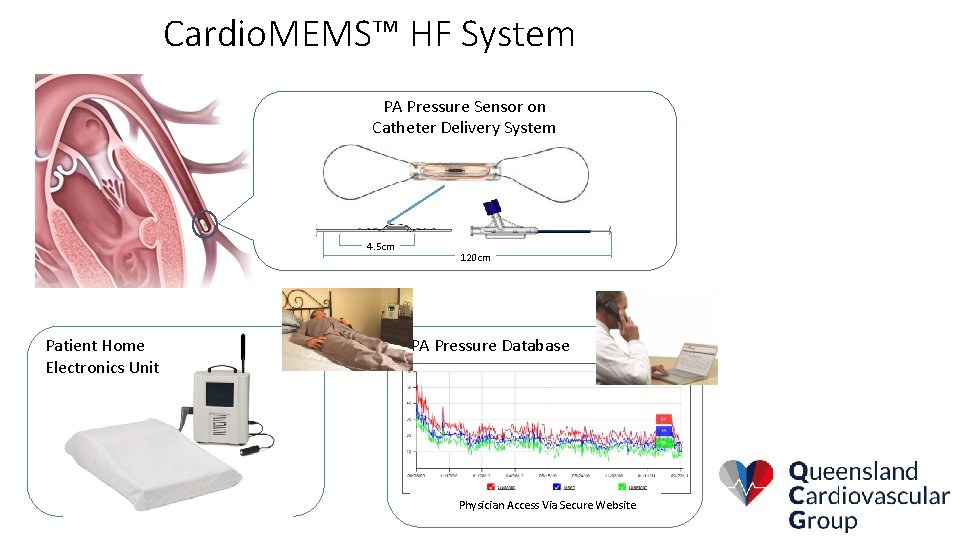

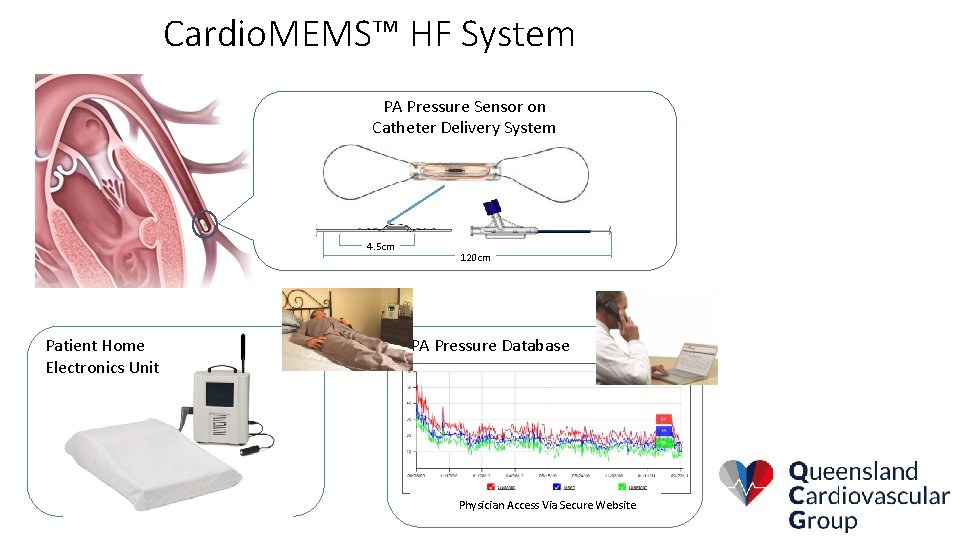

Cardio. MEMS™ HF System PA Pressure Sensor on Catheter Delivery System 4. 5 cm Patient Home Electronics Unit 120 cm PA Pressure Database Physician Access Via Secure Website

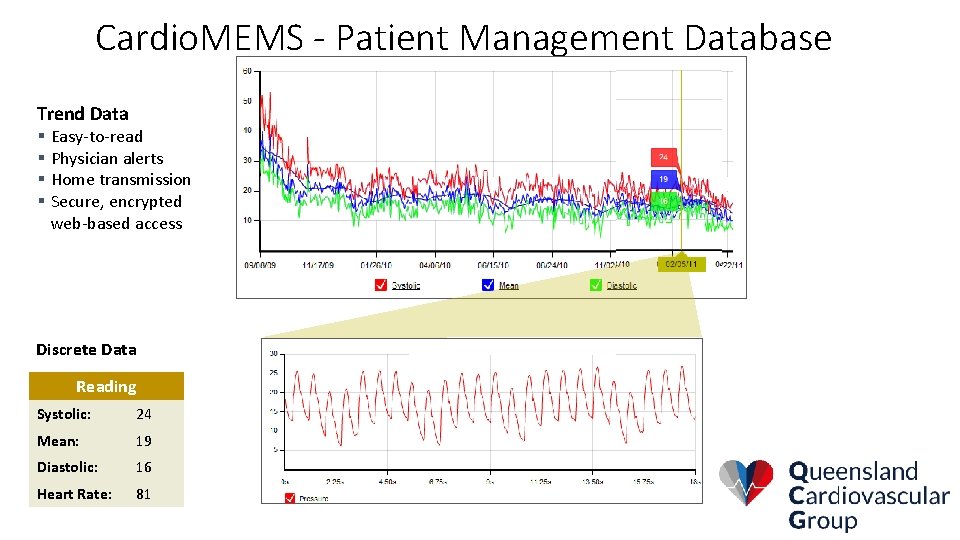

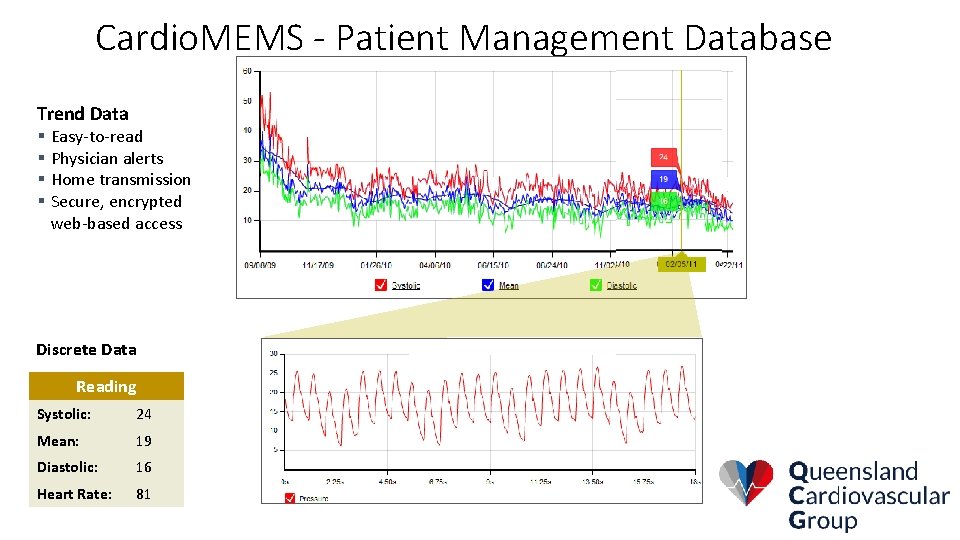

Cardio. MEMS - Patient Management Database Trend Data § Easy-to-read § Physician alerts § Home transmission § Secure, encrypted web-based access Discrete Data Reading Systolic: 24 Mean: 19 Diastolic: 16 Heart Rate: 81

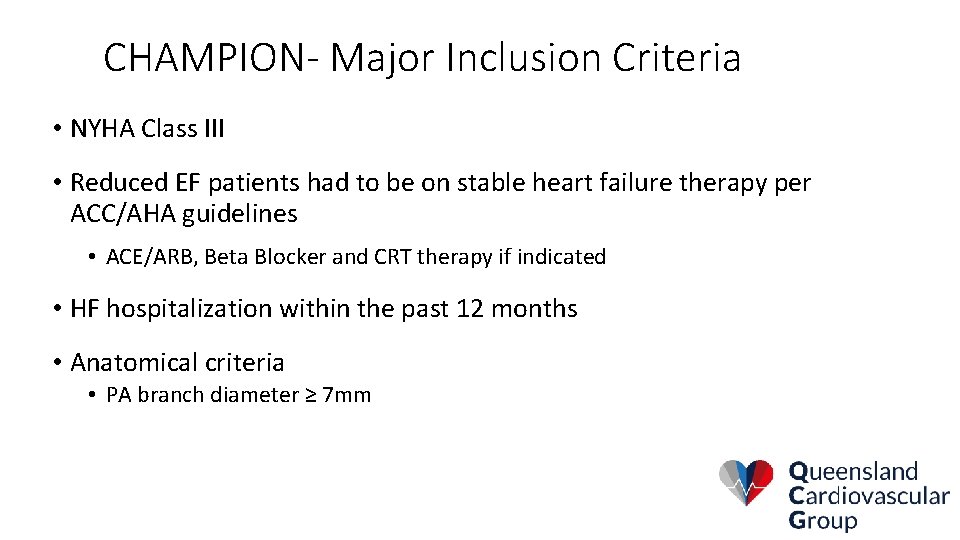

CHAMPION- Major Inclusion Criteria • NYHA Class III • Reduced EF patients had to be on stable heart failure therapy per ACC/AHA guidelines • ACE/ARB, Beta Blocker and CRT therapy if indicated • HF hospitalization within the past 12 months • Anatomical criteria • PA branch diameter ≥ 7 mm

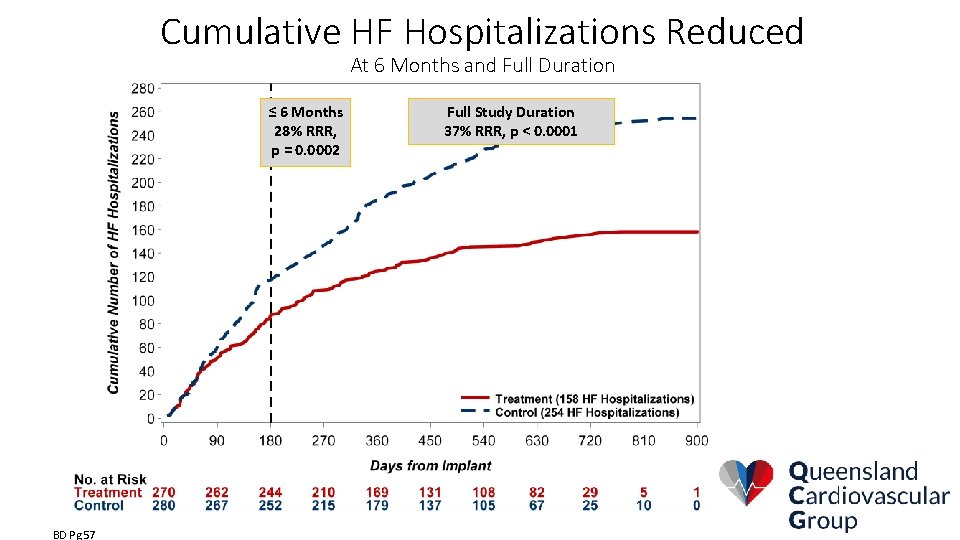

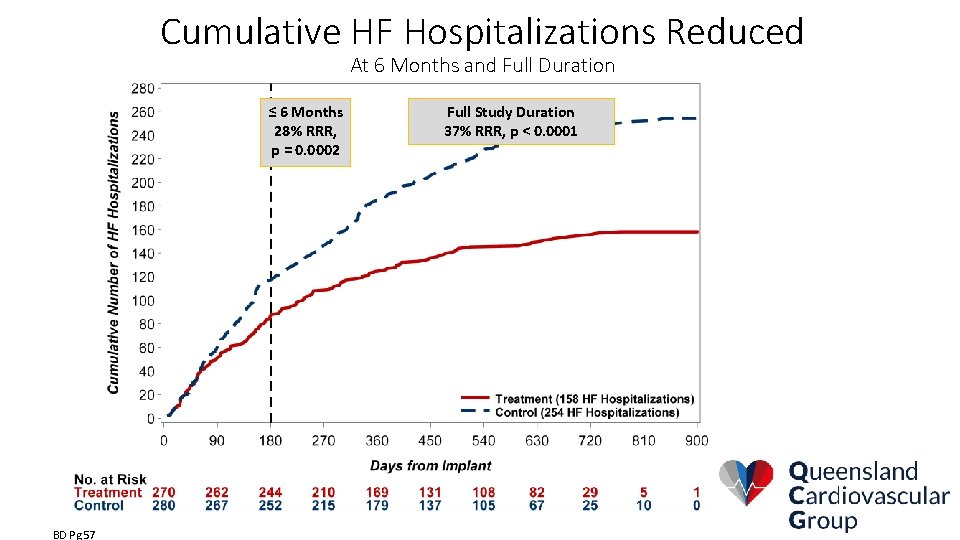

Cumulative HF Hospitalizations Reduced At 6 Months and Full Duration ≤ 6 Months 28% RRR, p = 0. 0002 BD Pg 57 Full Study Duration 37% RRR, p < 0. 0001

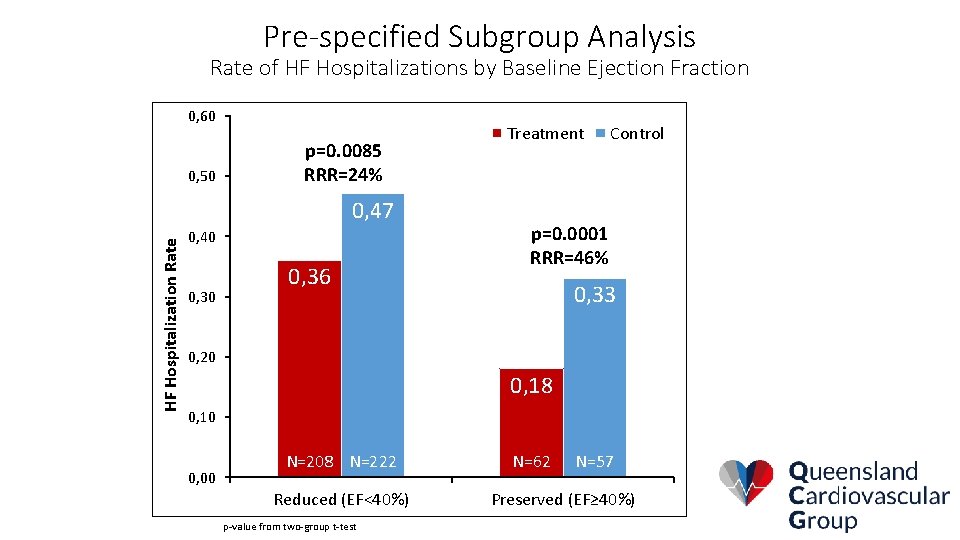

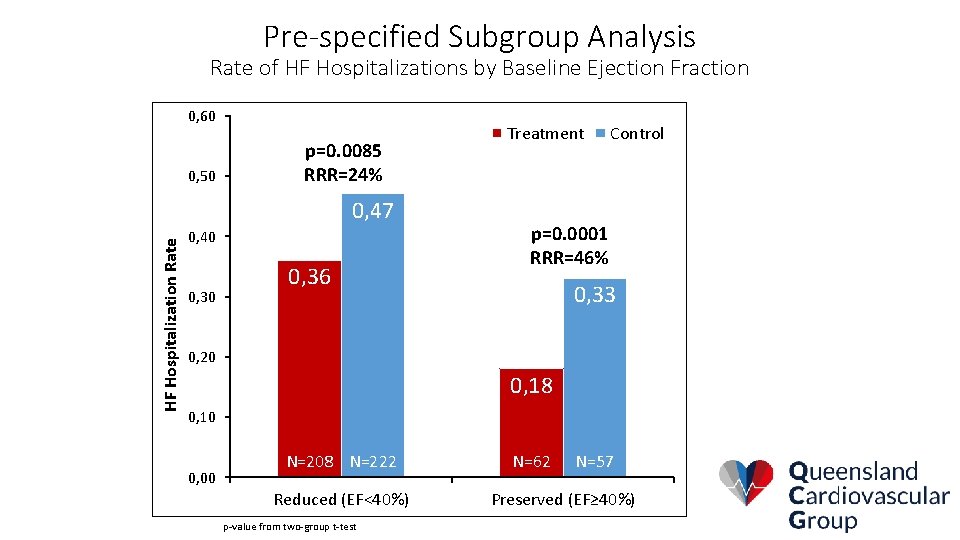

Pre-specified Subgroup Analysis Rate of HF Hospitalizations by Baseline Ejection Fraction 0, 60 0, 50 Treatment p=0. 0085 RRR=24% HF Hospitalization Rate 0, 47 0, 40 0, 36 Control p=0. 0001 RRR=46% 0, 33 0, 20 0, 18 0, 10 n= 222 0, 00 N=208 n= 208 N=222 Reduced (EF<40%) p-value from two-group t-test 62 n= 57 N=62 n=N=57 Preserved (EF≥ 40%)

CHAMPION Results in Special Populations

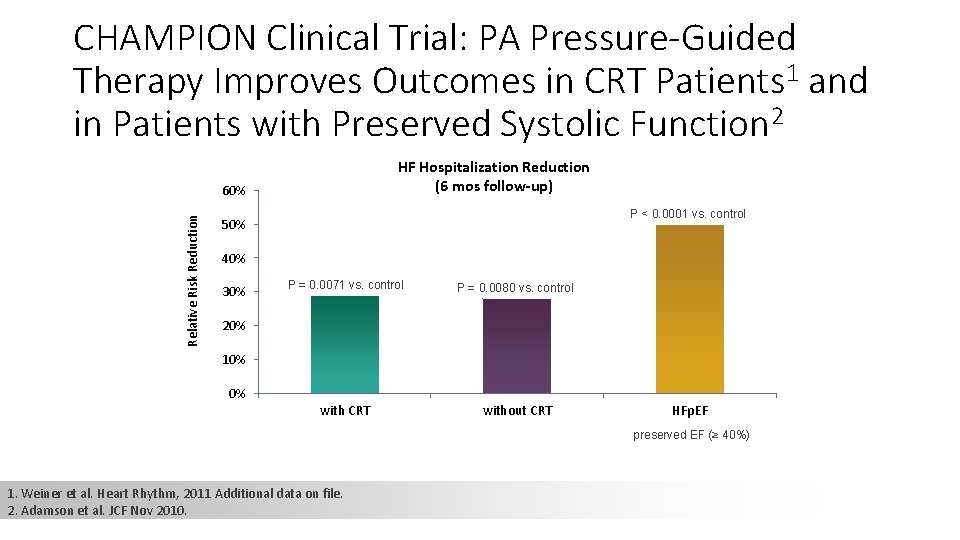

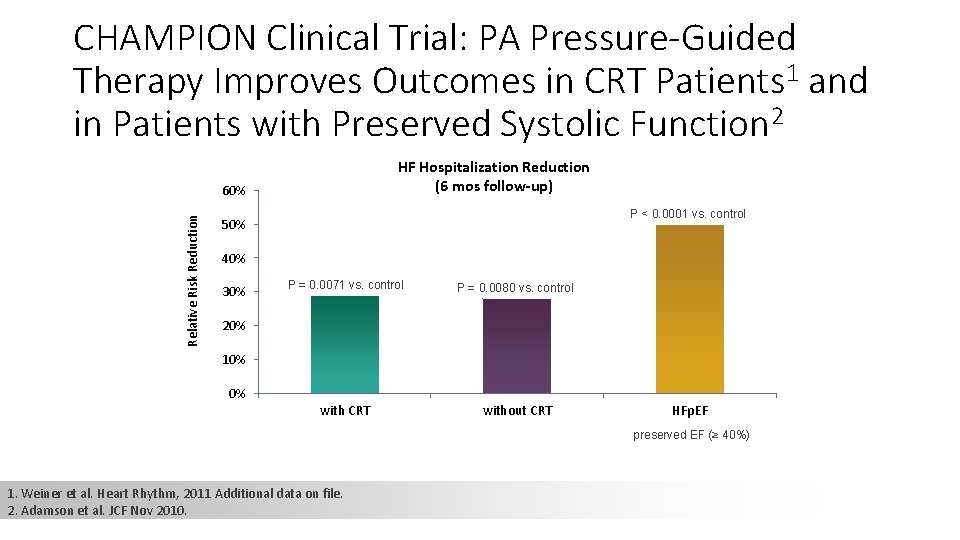

CHAMPION Clinical Trial: PA Pressure-Guided Therapy Improves Outcomes in CRT Patients 1 and in Patients with Preserved Systolic Function 2 HF Hospitalization Reduction (6 mos follow-up) Relative Risk Reduction 60% P < 0. 0001 vs. control 50% 40% 30% P = 0. 0071 vs. control P = 0. 0080 vs. control with CRT without CRT 20% 10% 0% HFp. EF preserved EF (≥ 40%) 1. Weiner et al. Heart Rhythm, 2011 Additional data on file. 2. Adamson et al. JCF Nov 2010.

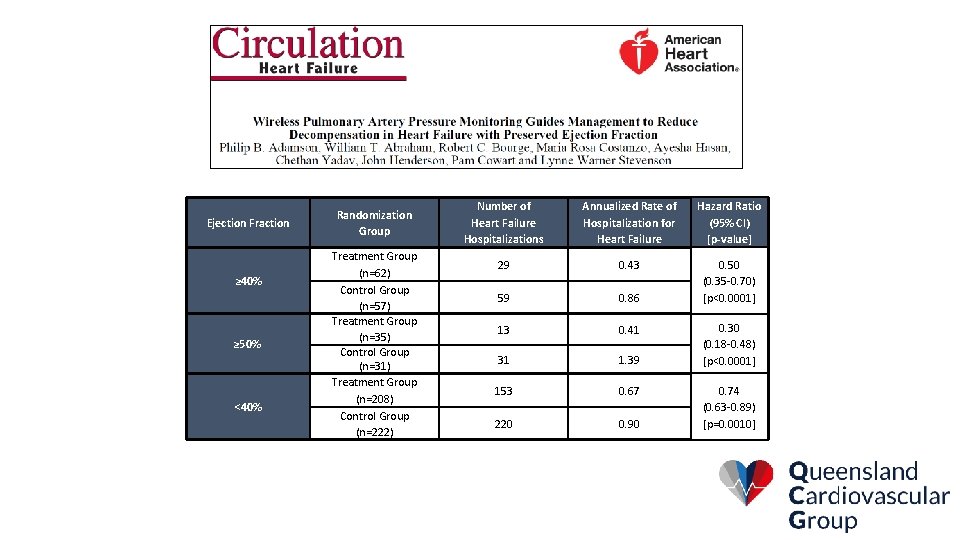

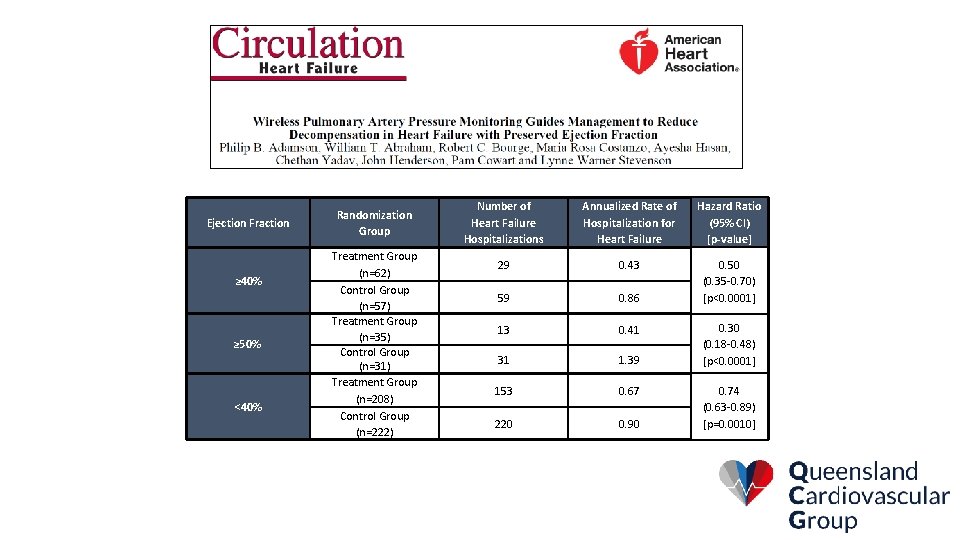

Ejection Fraction ≥ 40% ≥ 50% <40% Randomization Group Treatment Group (n=62) Control Group (n=57) Treatment Group (n=35) Control Group (n=31) Treatment Group (n=208) Control Group (n=222) Number of Heart Failure Hospitalizations Annualized Rate of Hospitalization for Heart Failure Hazard Ratio (95% CI) [p-value] 29 0. 43 59 0. 86 0. 50 (0. 35 -0. 70) [p<0. 0001] 13 0. 41 31 1. 39 153 0. 67 220 0. 90 0. 30 (0. 18 -0. 48) [p<0. 0001] 0. 74 (0. 63 -0. 89) [p=0. 0010]

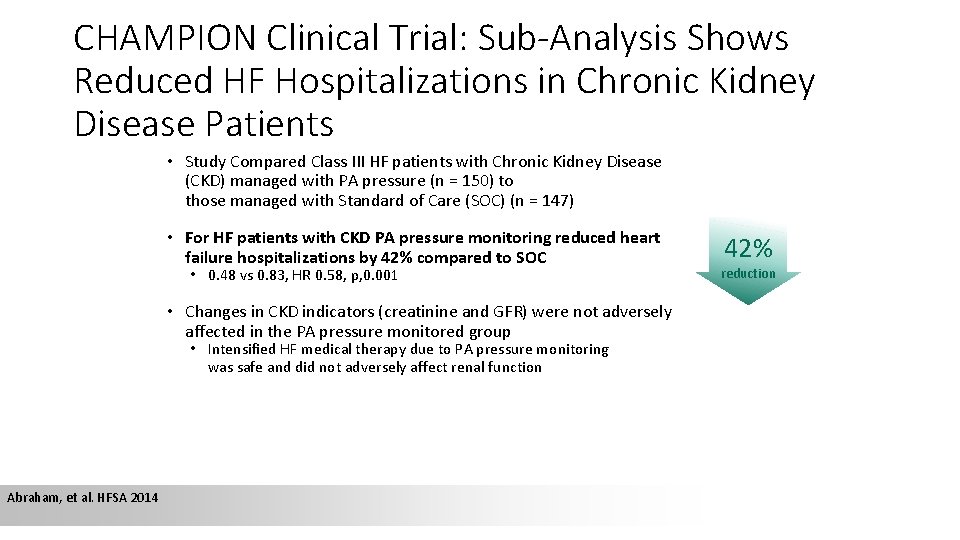

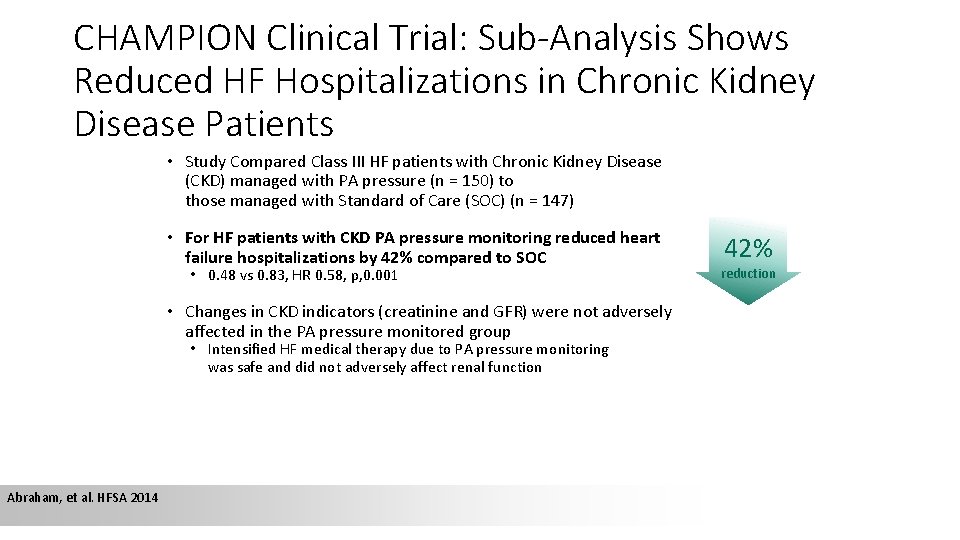

CHAMPION Clinical Trial: Sub-Analysis Shows Reduced HF Hospitalizations in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients • Study Compared Class III HF patients with Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) managed with PA pressure (n = 150) to those managed with Standard of Care (SOC) (n = 147) • For HF patients with CKD PA pressure monitoring reduced heart failure hospitalizations by 42% compared to SOC • 0. 48 vs 0. 83, HR 0. 58, p, 0. 001 • Changes in CKD indicators (creatinine and GFR) were not adversely affected in the PA pressure monitored group • Intensified HF medical therapy due to PA pressure monitoring was safe and did not adversely affect renal function Abraham, et al. HFSA 2014 42% reduction

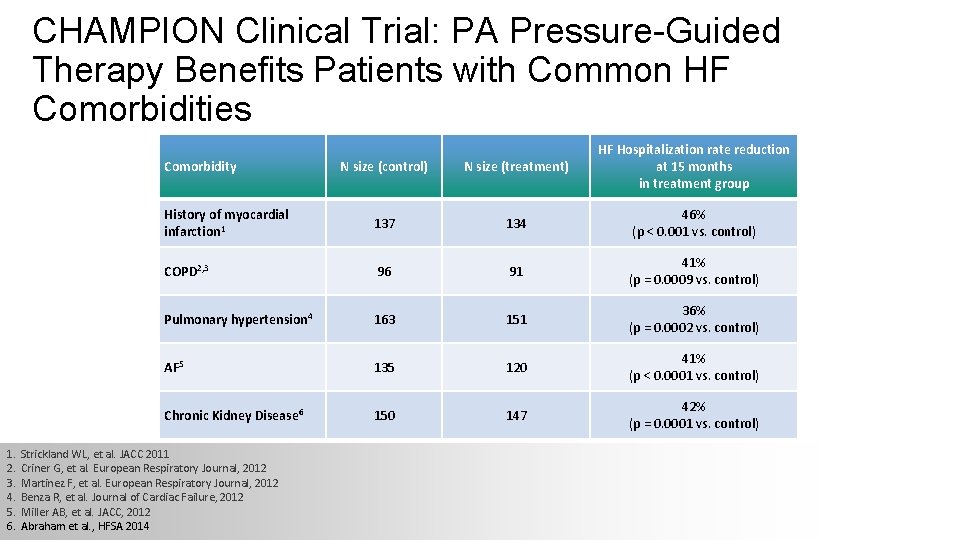

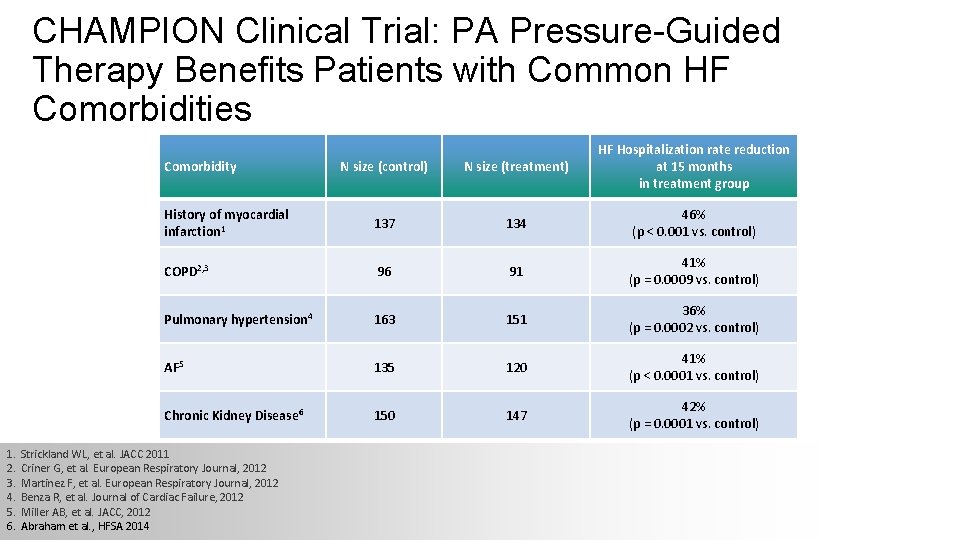

CHAMPION Clinical Trial: PA Pressure-Guided Therapy Benefits Patients with Common HF Comorbidities N size (control) N size (treatment) HF Hospitalization rate reduction at 15 months in treatment group History of myocardial infarction 1 137 134 46% (p < 0. 001 vs. control) COPD 2, 3 96 91 41% (p = 0. 0009 vs. control) Pulmonary hypertension 4 163 151 36% (p = 0. 0002 vs. control) AF 5 135 120 41% (p < 0. 0001 vs. control) Chronic Kidney Disease 6 150 147 42% (p = 0. 0001 vs. control) Comorbidity 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Strickland WL, et al. JACC 2011 Criner G, et al. European Respiratory Journal, 2012 Martinez F, et al. European Respiratory Journal, 2012 Benza R, et al. Journal of Cardiac Failure, 2012 Miller AB, et al. JACC, 2012 Abraham et al. , HFSA 2014

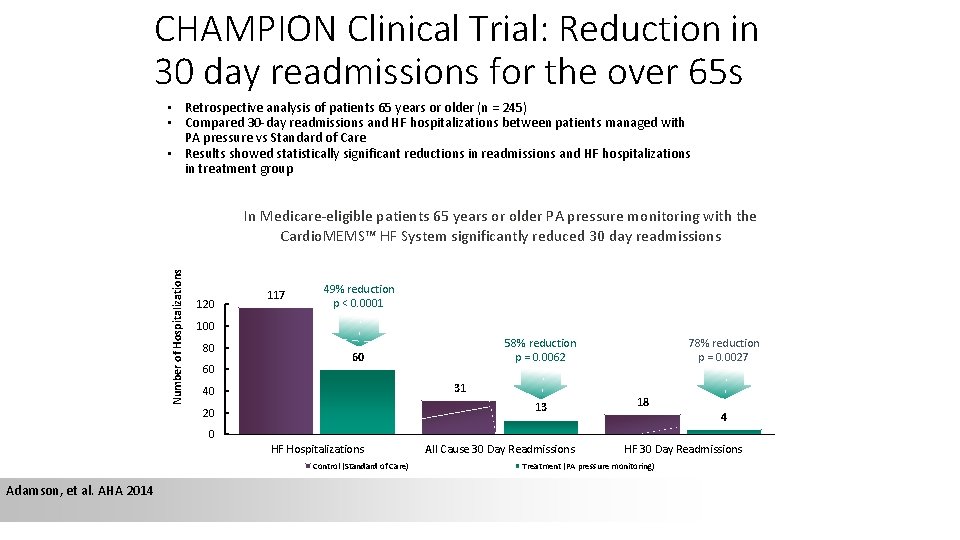

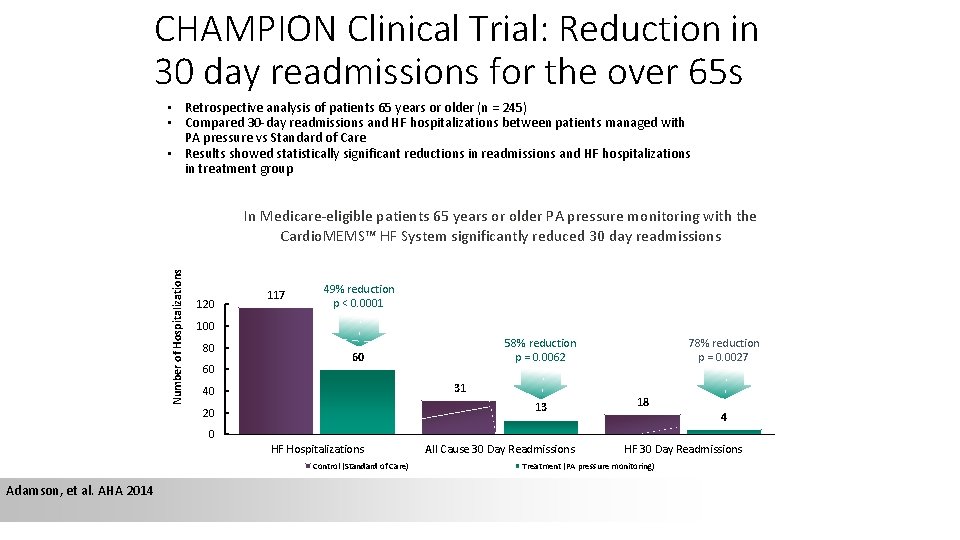

CHAMPION Clinical Trial: Reduction in 30 day readmissions for the over 65 s • Retrospective analysis of patients 65 years or older (n = 245) • Compared 30 -day readmissions and HF hospitalizations between patients managed with PA pressure vs Standard of Care • Results showed statistically significant reductions in readmissions and HF hospitalizations in treatment group Number of Hospitalizations In Medicare-eligible patients 65 years or older PA pressure monitoring with the Cardio. MEMS™ HF System significantly reduced 30 day readmissions 120 117 49% reduction p < 0. 0001 100 80 60 58% reduction p = 0. 0062 60 31 40 13 20 78% reduction p = 0. 0027 18 4 0 HF Hospitalizations Control (Standard of Care) Adamson, et al. AHA 2014 All Cause 30 Day Readmissions HF 30 Day Readmissions Treatment (PA pressure monitoring)

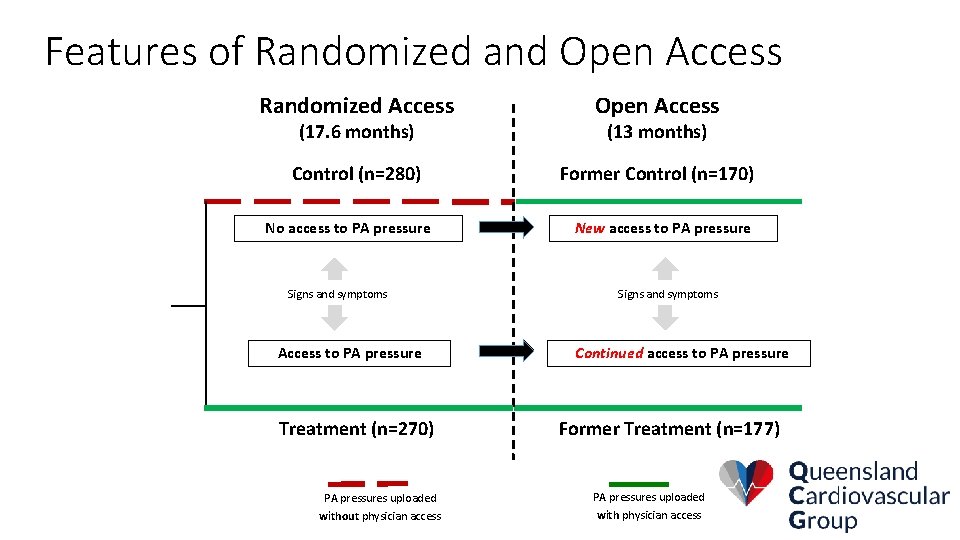

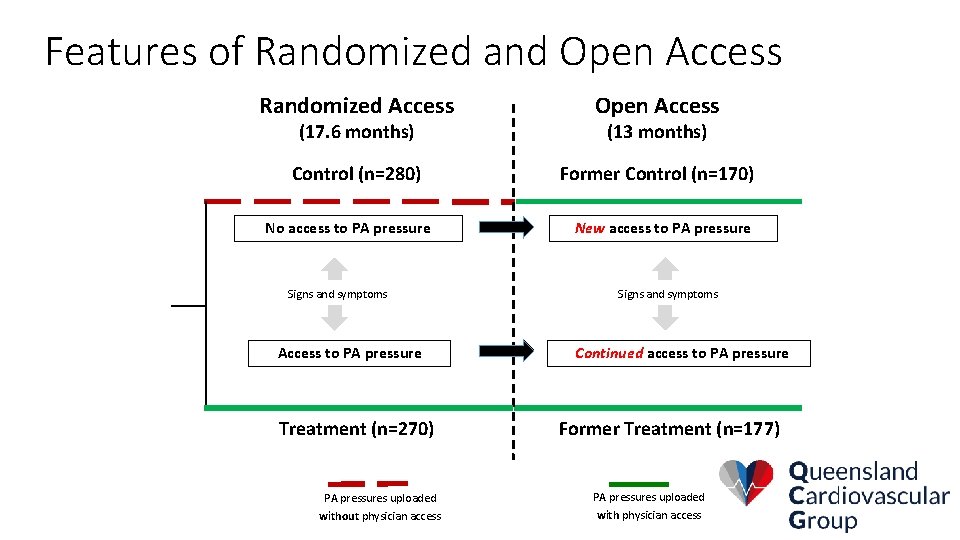

Features of Randomized and Open Access Randomized Access Open Access Control (n=280) Former Control (n=170) (17. 6 months) No access to PA pressure Signs and symptoms Access to PA pressure Treatment (n=270) (13 months) New access to PA pressure Signs and symptoms Continued access to PA pressure Former Treatment (n=177) PA pressures uploaded without physician access with physician access

Managing Heart Failure using PA Pressure 53

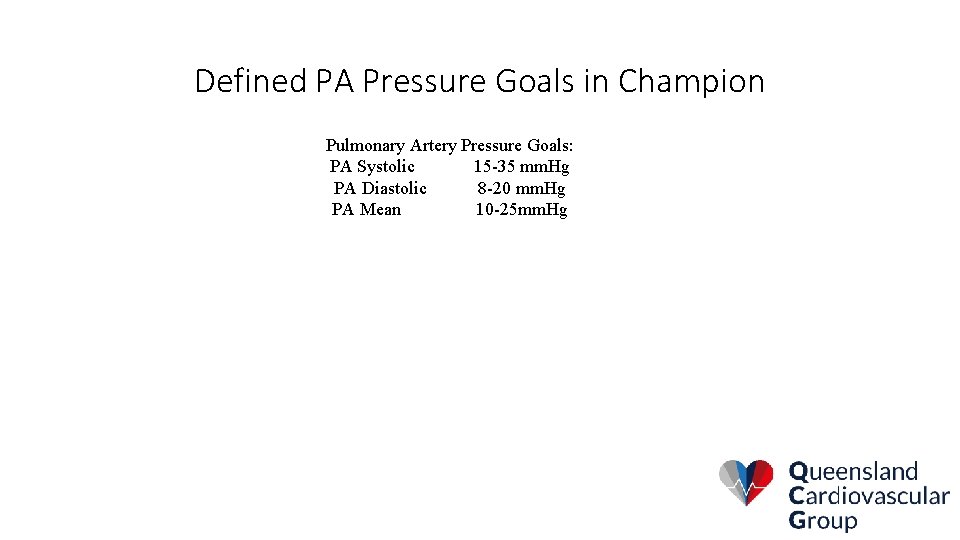

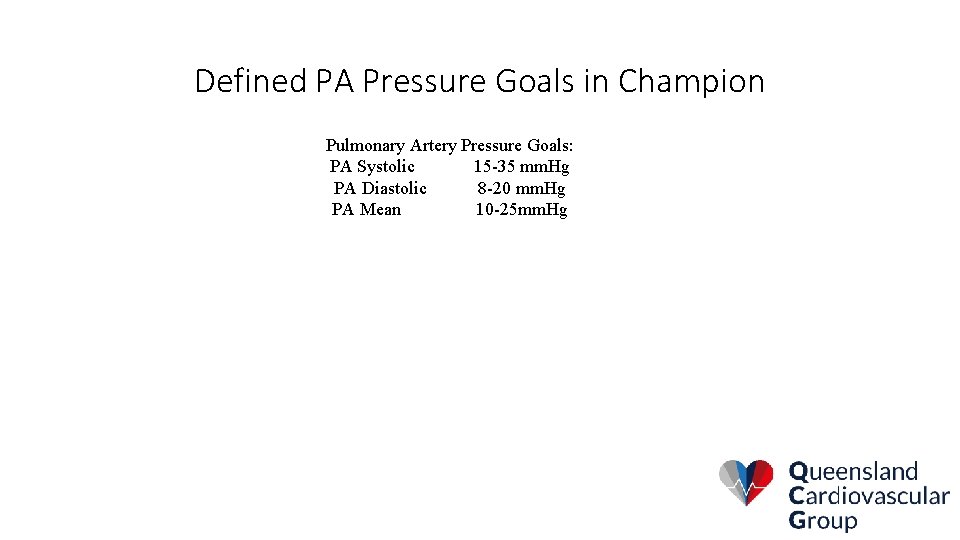

Defined PA Pressure Goals in Champion Pulmonary Artery Pressure Goals: PA Systolic 15 -35 mm. Hg PA Diastolic 8 -20 mm. Hg PA Mean 10 -25 mm. Hg

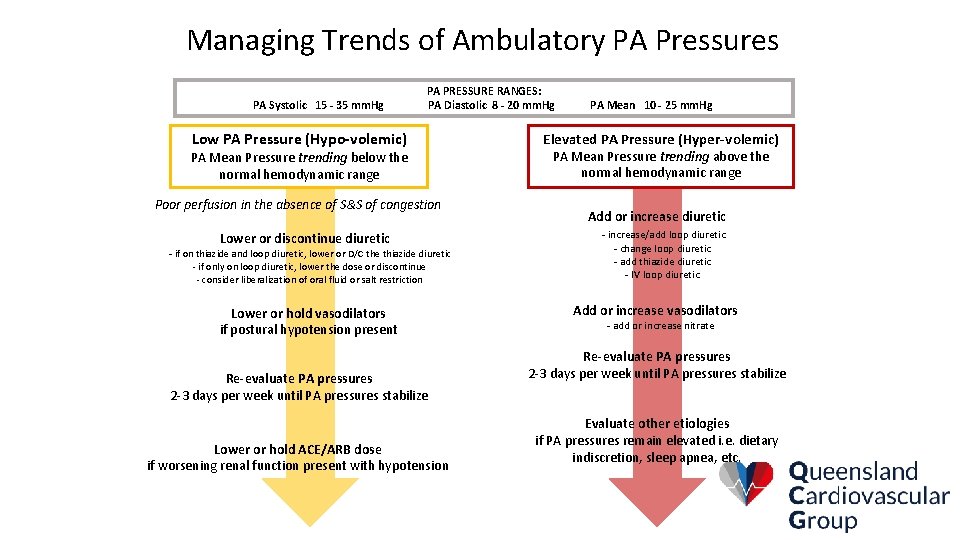

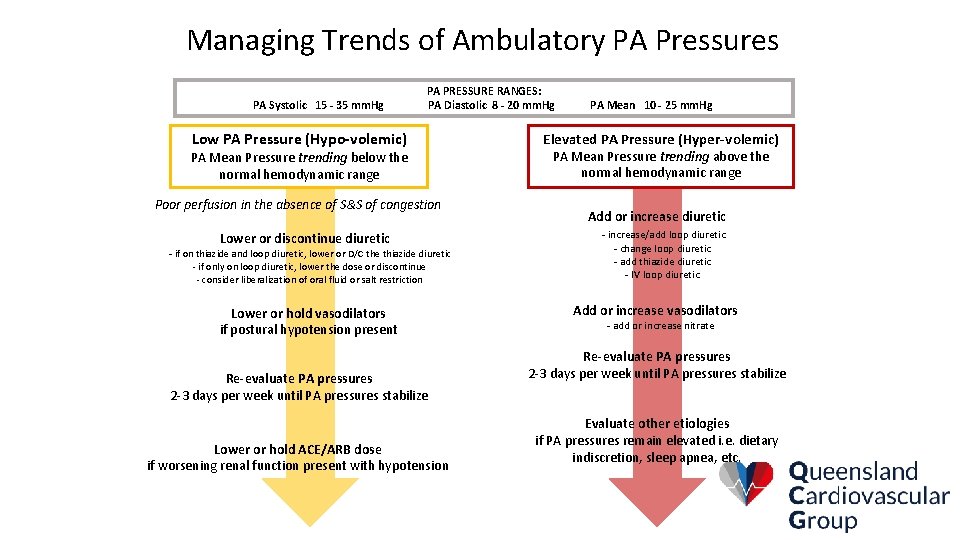

Managing Trends of Ambulatory PA Pressures PA Systolic 15 - 35 mm. Hg PA PRESSURE RANGES: PA Diastolic 8 - 20 mm. Hg Low PA Pressure (Hypo-volemic) PA Mean Pressure trending below the normal hemodynamic range Poor perfusion in the absence of S&S of congestion Lower or discontinue diuretic - if on thiazide and loop diuretic, lower or D/C the thiazide diuretic - if only on loop diuretic, lower the dose or discontinue - consider liberalization of oral fluid or salt restriction Lower or hold vasodilators if postural hypotension present Re-evaluate PA pressures 2 -3 days per week until PA pressures stabilize Lower or hold ACE/ARB dose if worsening renal function present with hypotension PA Mean 10 - 25 mm. Hg Elevated PA Pressure (Hyper-volemic) PA Mean Pressure trending above the normal hemodynamic range Add or increase diuretic - increase/add loop diuretic - change loop diuretic - add thiazide diuretic - IV loop diuretic Add or increase vasodilators - add or increase nitrate Re-evaluate PA pressures 2 -3 days per week until PA pressures stabilize Evaluate other etiologies if PA pressures remain elevated i. e. dietary indiscretion, sleep apnea, etc.

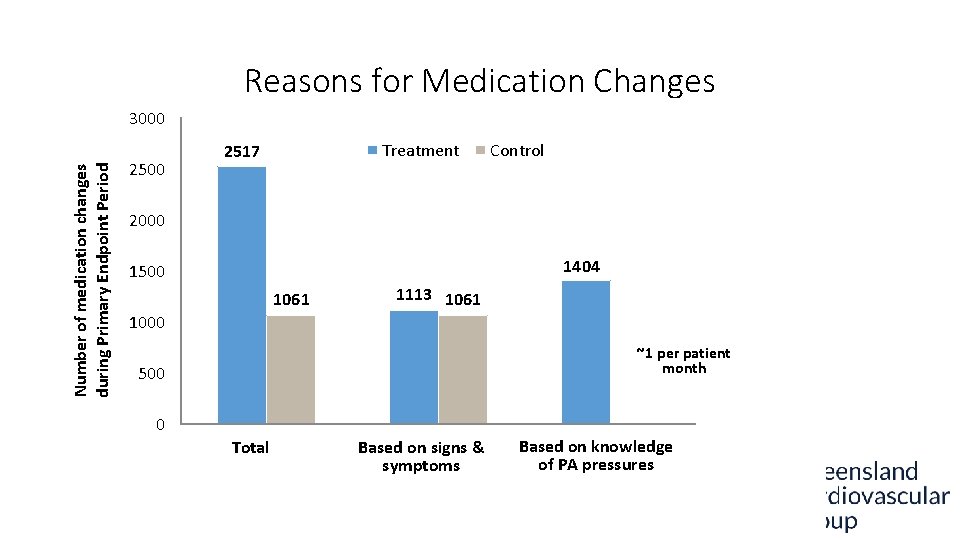

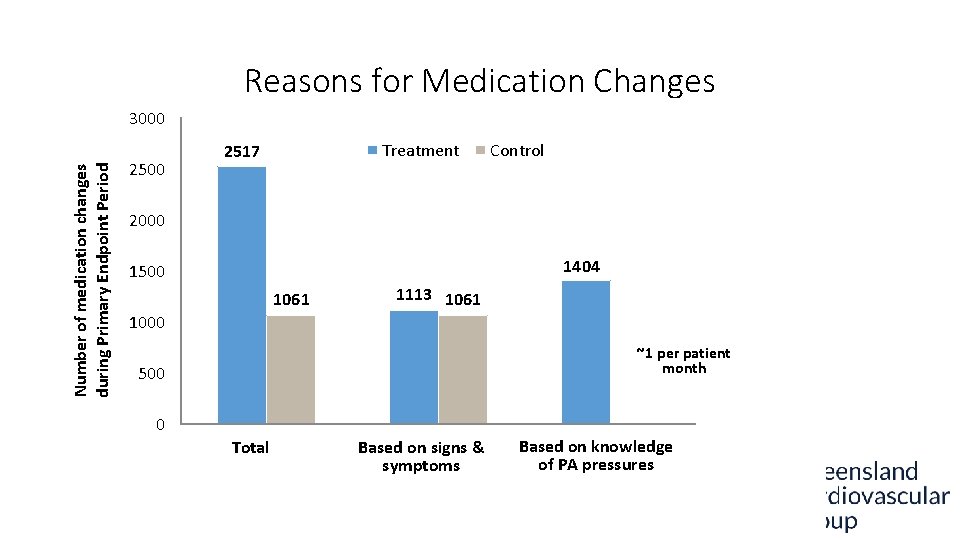

Reasons for Medication Changes Number of medication changes during Primary Endpoint Period 3000 2500 Treatment 2517 Control 2000 1404 1500 1061 1113 1061 1000 ~1 per patient month 500 0 0 NA Total Pressure-based Based on signs & symptoms Non-pressure based Based on knowledge of PA pressures

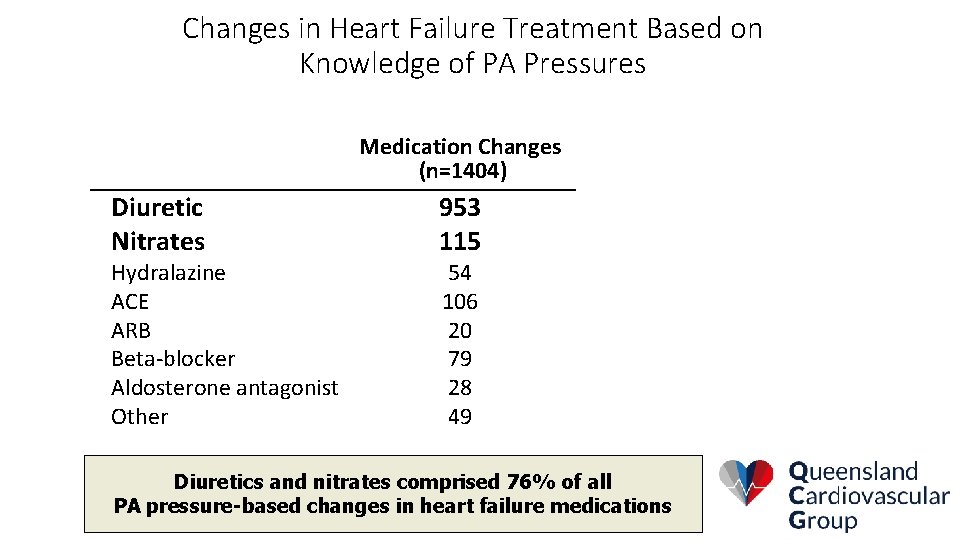

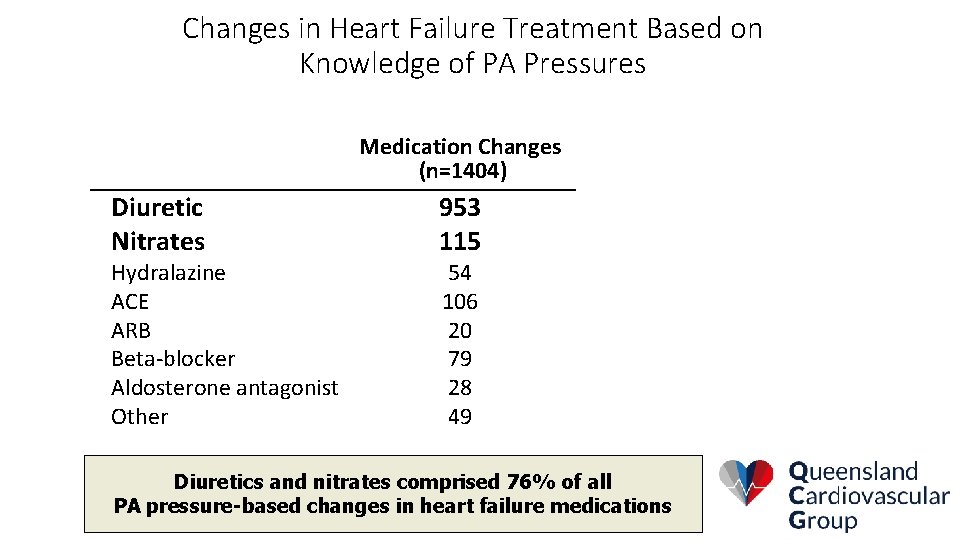

Changes in Heart Failure Treatment Based on Knowledge of PA Pressures Medication Changes (n=1404) Diuretic Nitrates Hydralazine ACE ARB Beta-blocker Aldosterone antagonist Other 953 115 54 106 20 79 28 49 Diuretics and nitrates comprised 76% of all PA pressure-based changes in heart failure medications

And maybe the patient’s barely relevant Adamson PB. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2009 Dec; 6(4): 287 -292

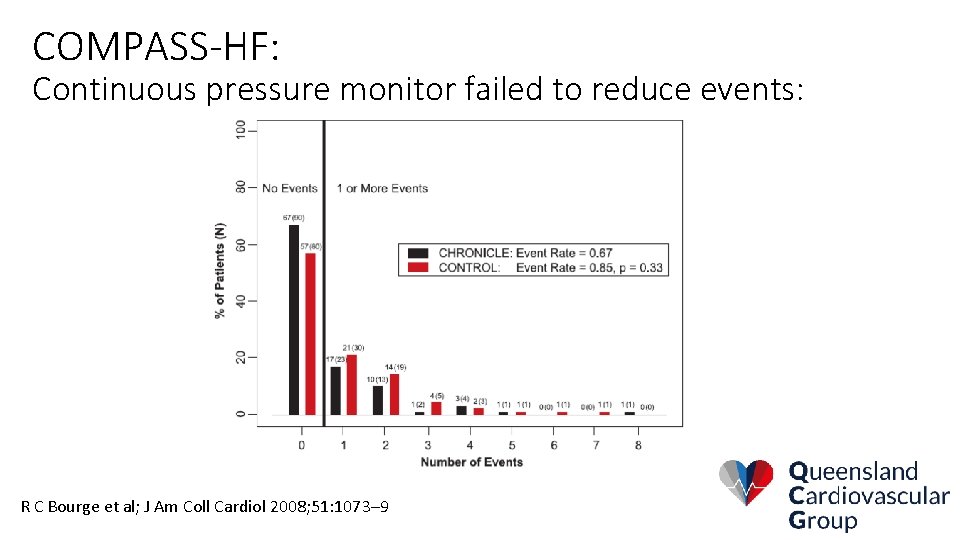

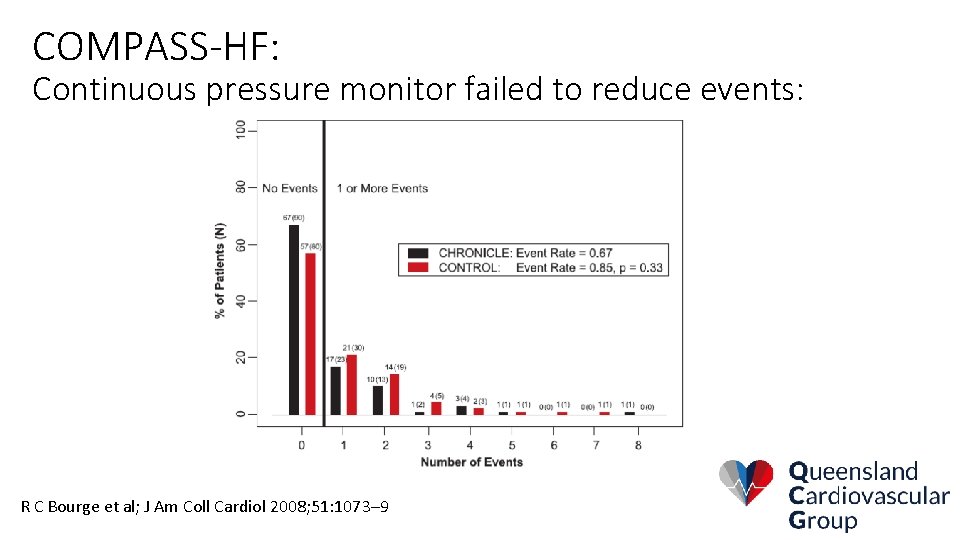

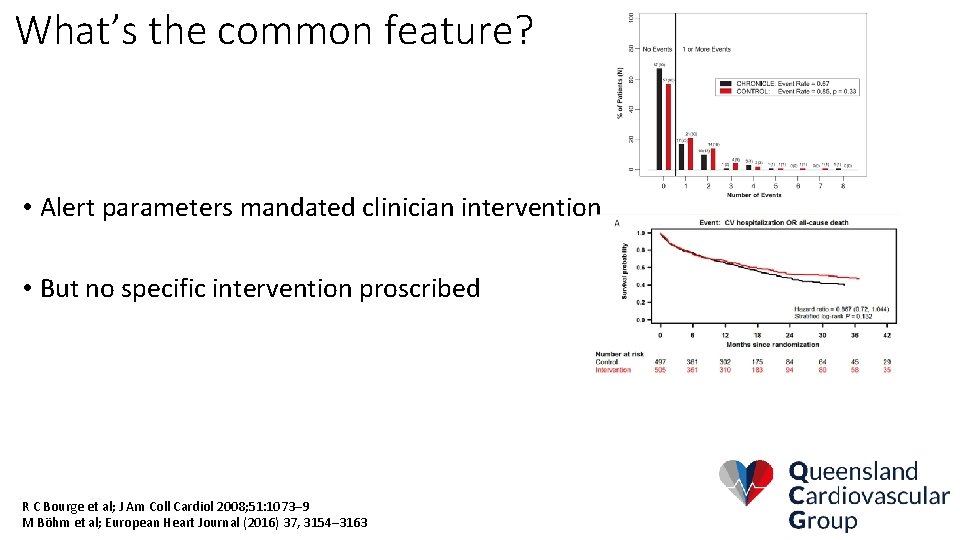

COMPASS-HF: Continuous pressure monitor failed to reduce events: R C Bourge et al; J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 51: 1073– 9

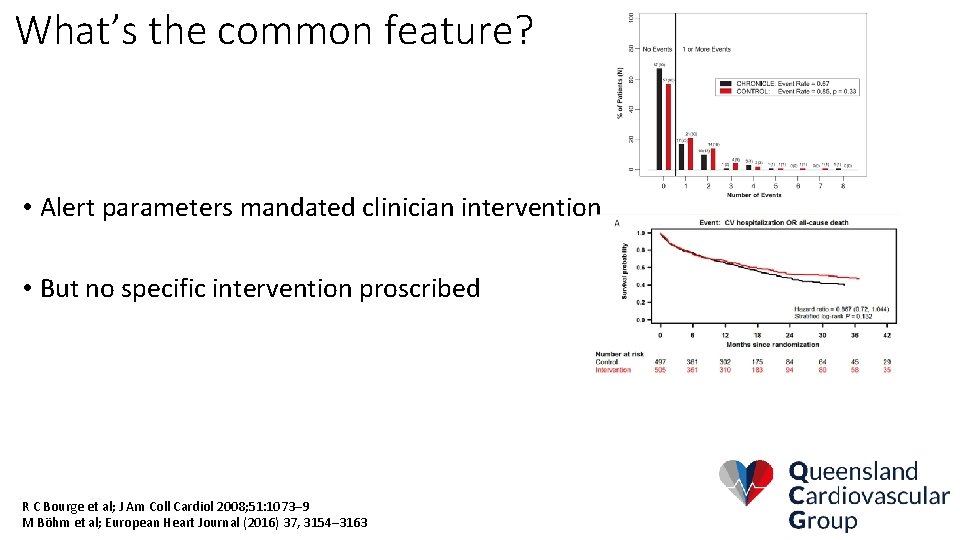

What’s the common feature? • Alert parameters mandated clinician intervention • But no specific intervention proscribed R C Bourge et al; J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 51: 1073– 9 M Böhm et al; European Heart Journal (2016) 37, 3154– 3163

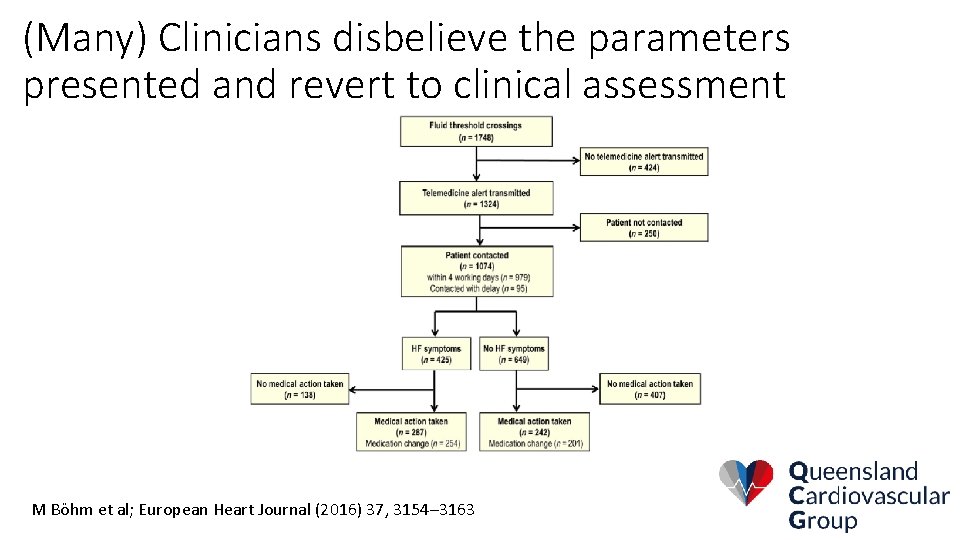

(Many) Clinicians disbelieve the parameters presented and revert to clinical assessment M Böhm et al; European Heart Journal (2016) 37, 3154– 3163

Conclusion • Heart Failure remote monitoring tools need to detect changes early enough that action can be taken • Clinicians need to act on the data presented and not wait for clinical signs and symptoms • But Clinicians need to understand what triggers an alert in order to know how to act