Relational Databases and SQL Session 1 An Introduction

Relational Databases and SQL Session 1 An Introduction Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004

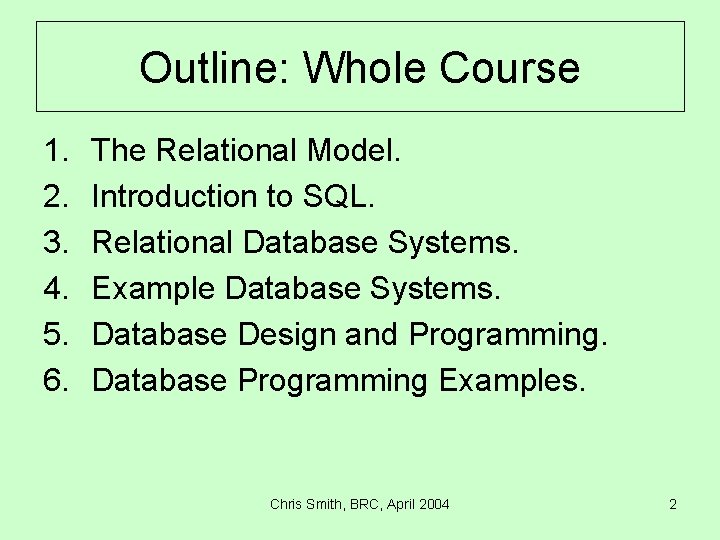

Outline: Whole Course 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. The Relational Model. Introduction to SQL. Relational Database Systems. Example Database Systems. Database Design and Programming. Database Programming Examples. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 2

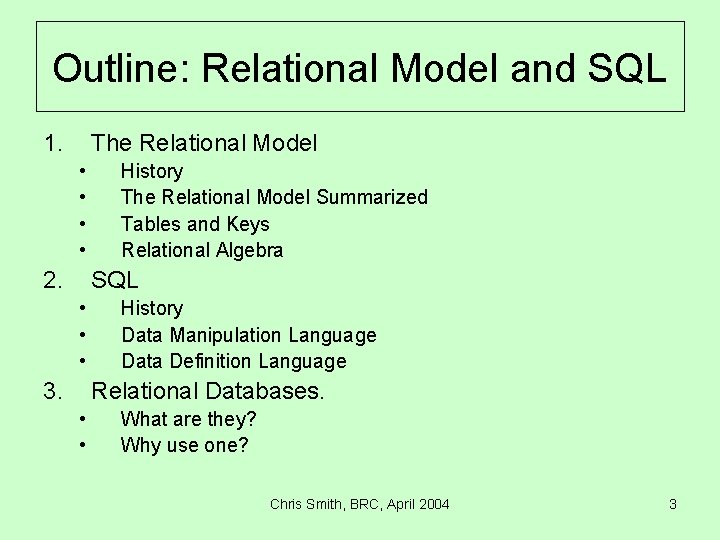

Outline: Relational Model and SQL 1. The Relational Model • • 2. History The Relational Model Summarized Tables and Keys Relational Algebra SQL • • • 3. History Data Manipulation Language Data Definition Language Relational Databases. • • What are they? Why use one? Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 3

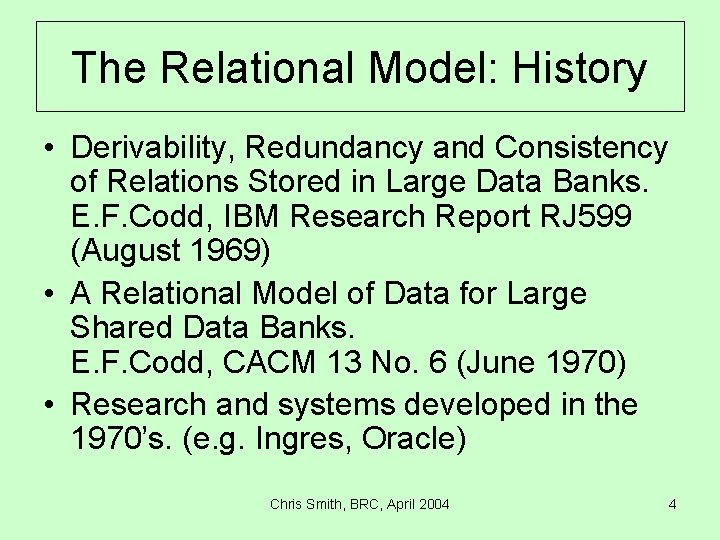

The Relational Model: History • Derivability, Redundancy and Consistency of Relations Stored in Large Data Banks. E. F. Codd, IBM Research Report RJ 599 (August 1969) • A Relational Model of Data for Large Shared Data Banks. E. F. Codd, CACM 13 No. 6 (June 1970) • Research and systems developed in the 1970’s. (e. g. Ingres, Oracle) Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 4

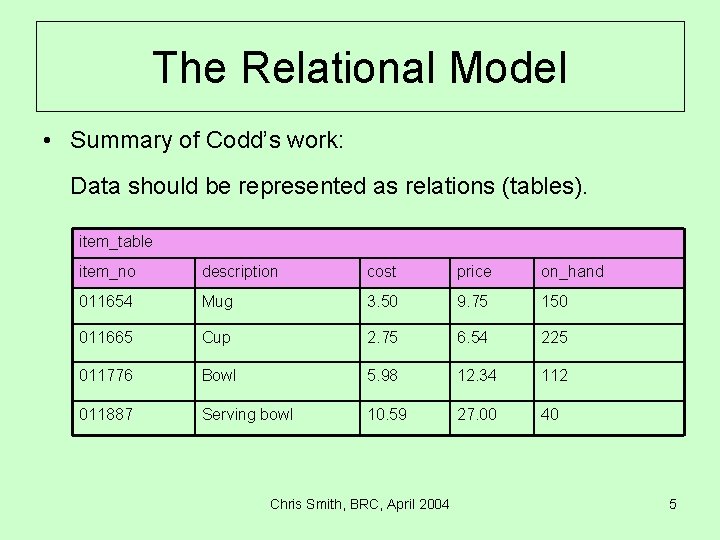

The Relational Model • Summary of Codd’s work: Data should be represented as relations (tables). item_table item_no description cost price on_hand 011654 Mug 3. 50 9. 75 150 011665 Cup 2. 75 6. 54 225 011776 Bowl 5. 98 12. 34 112 011887 Serving bowl 10. 59 27. 00 40 Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 5

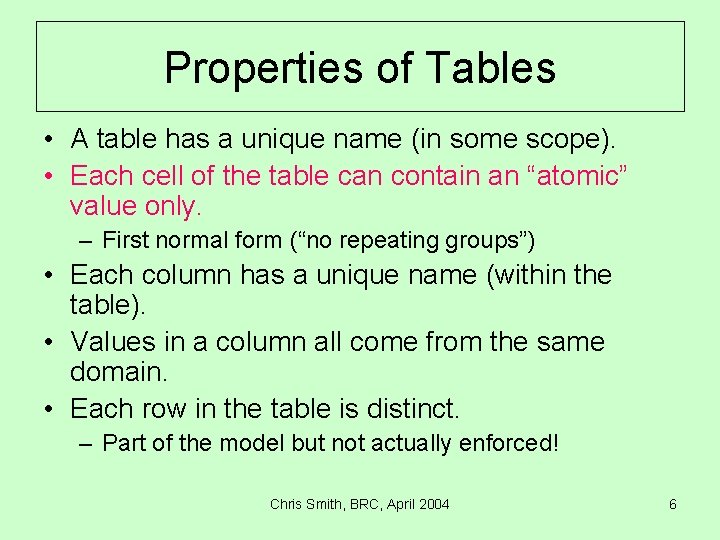

Properties of Tables • A table has a unique name (in some scope). • Each cell of the table can contain an “atomic” value only. – First normal form (“no repeating groups”) • Each column has a unique name (within the table). • Values in a column all come from the same domain. • Each row in the table is distinct. – Part of the model but not actually enforced! Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 6

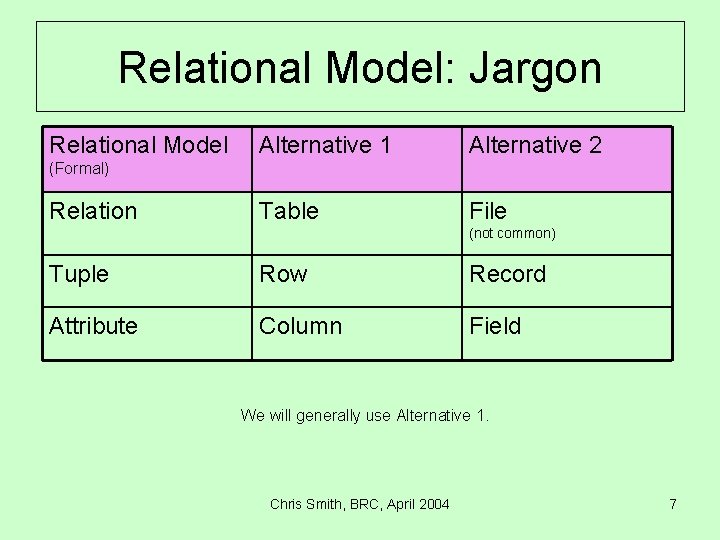

Relational Model: Jargon Relational Model Alternative 1 Alternative 2 Table File (Formal) Relation (not common) Tuple Row Record Attribute Column Field We will generally use Alternative 1. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 7

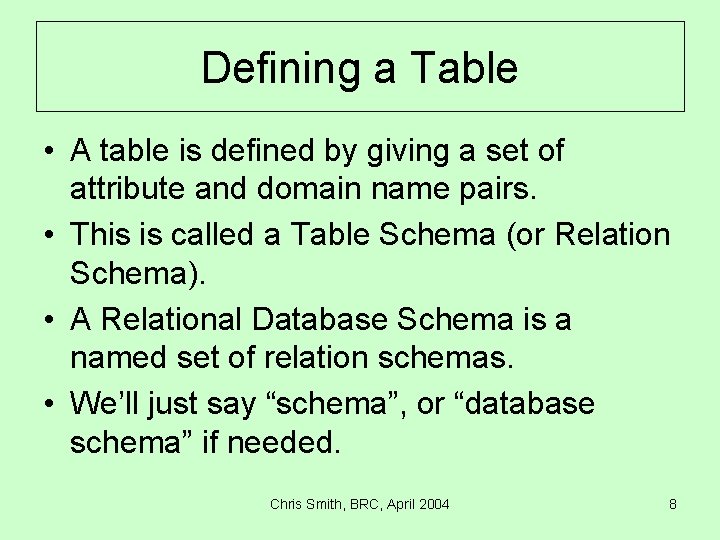

Defining a Table • A table is defined by giving a set of attribute and domain name pairs. • This is called a Table Schema (or Relation Schema). • A Relational Database Schema is a named set of relation schemas. • We’ll just say “schema”, or “database schema” if needed. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 8

Keys • For practical purposes we want to be able to identify rows in our tables. – We use keys for this. • A key is just a set of columns in the table. • Quite frequently just one column is enough, and quite often it is obvious what it should be. • There are rules of thumb regarding choosing keys which we will see later. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 9

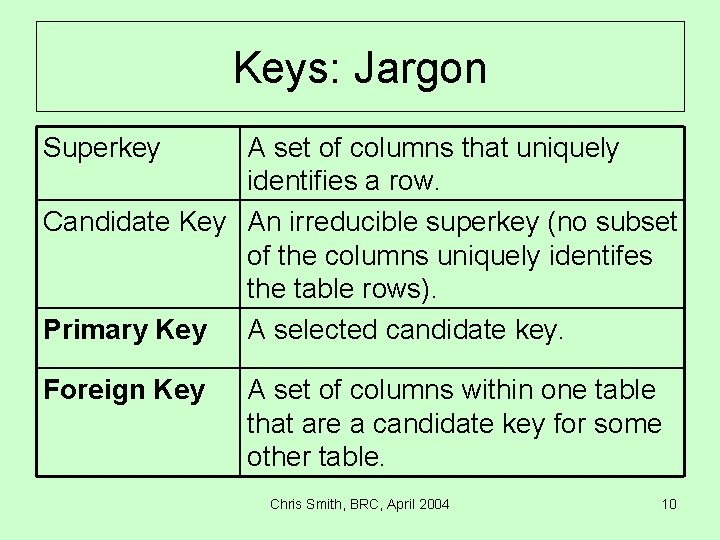

Keys: Jargon Superkey A set of columns that uniquely identifies a row. Candidate Key An irreducible superkey (no subset of the columns uniquely identifes the table rows). Primary Key A selected candidate key. Foreign Key A set of columns within one table that are a candidate key for some other table. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 10

NULL Values • A special value “NULL” is provided to allow for cells in a table that have an unspecified value. • NULL is not the same as zero or the empty string, but represents complete absence of a value. • Incorporation of NULL in the relational is contentious – but it’s here to stay. • No part of a primary key may be NULL. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 11

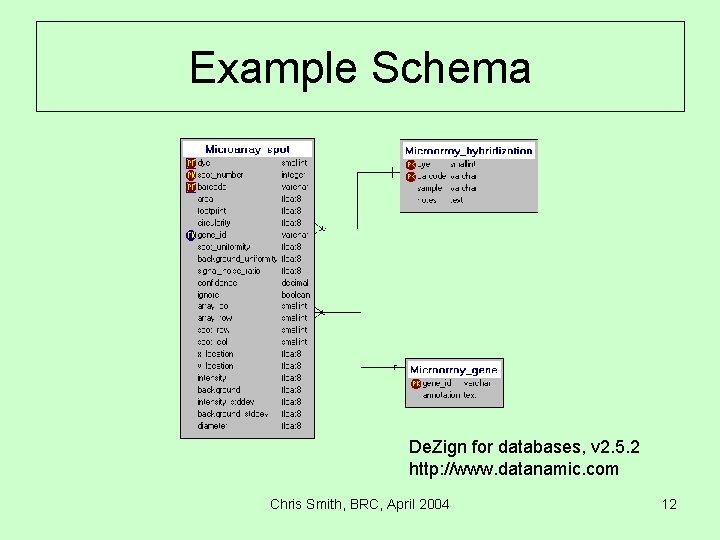

Example Schema De. Zign for databases, v 2. 5. 2 http: //www. datanamic. com Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 12

Hierarchical Data • The restriction to one atomic piece of data per cell precludes adding hierarchical data directly to a table. • Use a separate table and a foreign key instead. • All “spots” are gathered into one table and connected to their owner by the foreign key. • Using multiple tables helps reduce redundancy e. g. gene annotation text is not duplicated for every spot with that gene. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 13

Relational Algebra • We have seen how to define tables (relations). We want to be able to manipulate them too. • “The relational algebra is a theoretical language with operations that work on one or more relations to define another relation without changing the original relation(s). ” (“Database Systems” Connolly and Begg. ) Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 14

Relational Algebra: Unary Operations • Selection – Take a subset of rows from a table (on some criterion). • Projection – Take a subset of columns from a table. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 15

Relational Algebra: Binary Operations 1 • Union – Return all rows from two tables. – The two tables must have columns with the same domains (union compatibility). • Intersection – Return all matching rows from two tables. • Difference – Return all rows from one table not in another. – The two tables must be union compatible. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 16

Relational Algebra: Binary Operations 2 • Cartesian Product – Concatenate every row from one table with every row from another. • Join – Not really a separate operation: can be defined in terms of cartesian product and selection. – Is very important. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 17

Relational Database Management System (RDBMS) • Implements the relational model and relational algebra (under the covers). • Provides a language for managing relations. • Provides a language for accessing and updating data. • Provides other services: – – Security Indexing for efficiency. Backup services (maybe). Distribution services (maybe). Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 18

RDBMS Implementation • An RDBMS is usually implemented as a server program. • Client programs communicate with the server (typically using TCP/IP). – In Unix-based systems the server will run as a daemon. – In Windows it will run as a service. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 19

SQL History • Structured Query Language. • Officially pronounced S-Q-L, but many people say “sequel”. • Has its roots in the mid-1970’s. • Standardized in 1986 (ANSI), 1987 (ISO) • Further standards in 1992 (ISO SQL 2 or SQL-92), 1999 (ISO SQL 3). Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 20

SQL Today • SQL is the only database language to have gained broad acceptance. • Nearly every database system supports it. • The ISO SQL standard uses the “Table, Row, Column” terminology rather than “Relation, Tuple, Attribute”. • Some debate about how closely SQL adheres to the relational model. • Many different dialects from different vendors. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 21

SQL • SQL is divided into two parts: – Data Manipulation Language – Data Definition Language • Originally designed to be used from another language and not intended to be a complete programming language in its own right. • Non-procedural. Define what you want, not how to get it. • Supposed to be “English Like”! Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 22

SQL: Syntax • Can be a little arcane. • String literals are surrounded by single quotes. Numeric literals are not enclosed in quotes. • SELECT price FROM item_table WHERE description = ‘Mug’ Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 23

SQL: Data Manipulation Language • Statements – SELECT – INSERT – UPDATE – DELETE Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 24

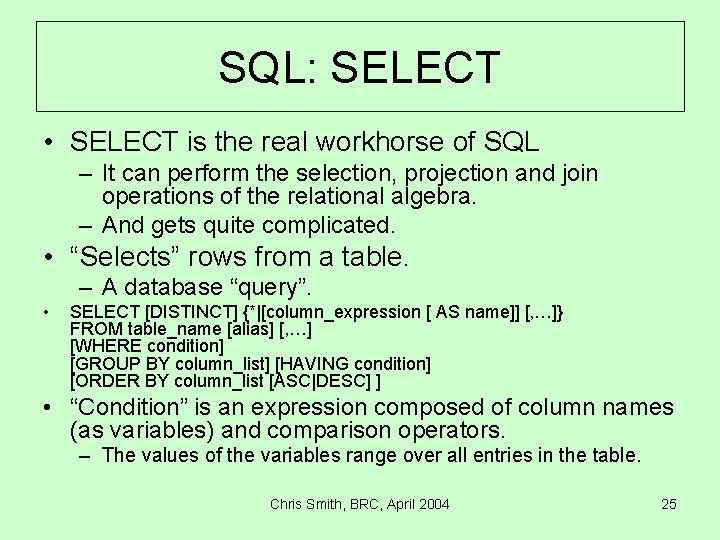

SQL: SELECT • SELECT is the real workhorse of SQL – It can perform the selection, projection and join operations of the relational algebra. – And gets quite complicated. • “Selects” rows from a table. – A database “query”. • SELECT [DISTINCT] {*|[column_expression [ AS name]] [, …]} FROM table_name [alias] [, …] [WHERE condition] [GROUP BY column_list] [HAVING condition] [ORDER BY column_list [ASC|DESC] ] • “Condition” is an expression composed of column names (as variables) and comparison operators. – The values of the variables range over all entries in the table. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 25

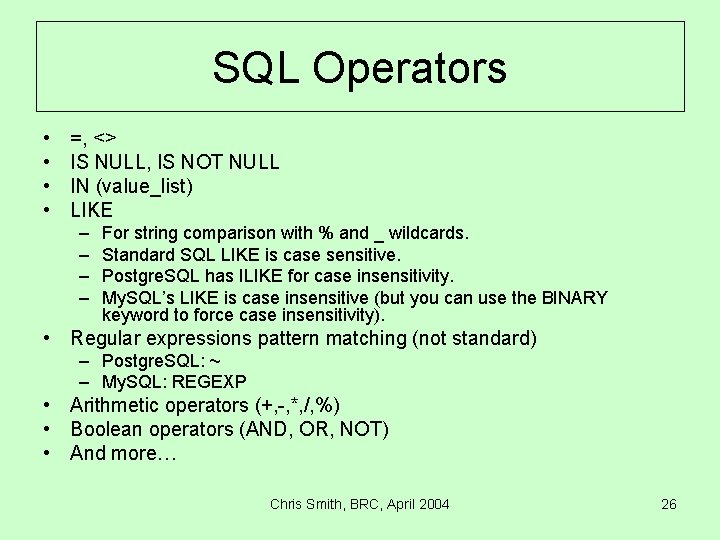

SQL Operators • • =, <> IS NULL, IS NOT NULL IN (value_list) LIKE – – For string comparison with % and _ wildcards. Standard SQL LIKE is case sensitive. Postgre. SQL has ILIKE for case insensitivity. My. SQL’s LIKE is case insensitive (but you can use the BINARY keyword to force case insensitivity). • Regular expressions pattern matching (not standard) – Postgre. SQL: ~ – My. SQL: REGEXP • Arithmetic operators (+, -, *, /, %) • Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) • And more… Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 26

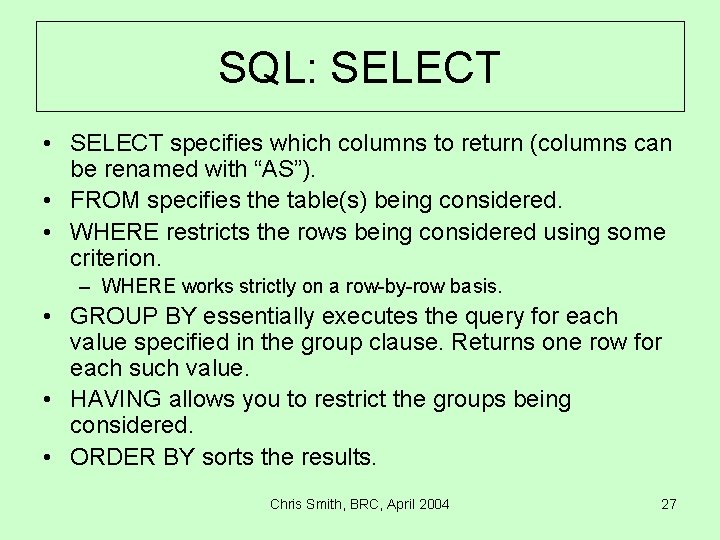

SQL: SELECT • SELECT specifies which columns to return (columns can be renamed with “AS”). • FROM specifies the table(s) being considered. • WHERE restricts the rows being considered using some criterion. – WHERE works strictly on a row-by-row basis. • GROUP BY essentially executes the query for each value specified in the group clause. Returns one row for each such value. • HAVING allows you to restrict the groups being considered. • ORDER BY sorts the results. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 27

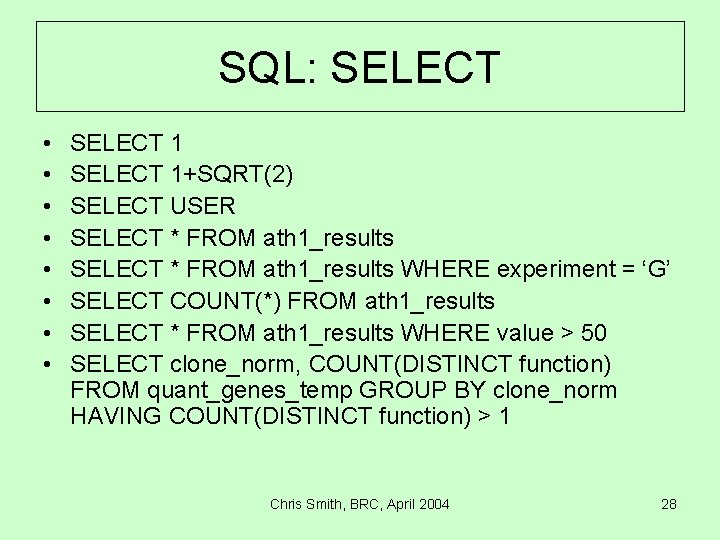

SQL: SELECT • • SELECT 1+SQRT(2) SELECT USER SELECT * FROM ath 1_results WHERE experiment = ‘G’ SELECT COUNT(*) FROM ath 1_results SELECT * FROM ath 1_results WHERE value > 50 SELECT clone_norm, COUNT(DISTINCT function) FROM quant_genes_temp GROUP BY clone_norm HAVING COUNT(DISTINCT function) > 1 Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 28

SQL: Aggregate Functions • Can only appear in the SELECT clause, or a HAVING clause (not in a WHERE clause: WHERE applies to single rows). • SUM, AVG, COUNT, MIN, MAX – Different systems provide others e. g. Postgre. SQL has STDDEV and VARIANCE, My. SQL has STDDEV. • Can use DISTINCT inside the parentheses: COUNT(DISTINCT name) • Can use COUNT(*) to count number of rows. • Apart from COUNT(*), NULLs are ignored. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 29

SQL: JOIN • Cartesian product and selection from relational algebra. • Joining large tables can be very, very slow (because of the product step): make sure you limit the results as much as possible. • Different types of join determine behavior on mismatches. – LEFT JOIN includes rows with values on the left, but no matching value on the right etc. • Joins recreate the spreadsheet view from a hierarchical view of the data. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 30

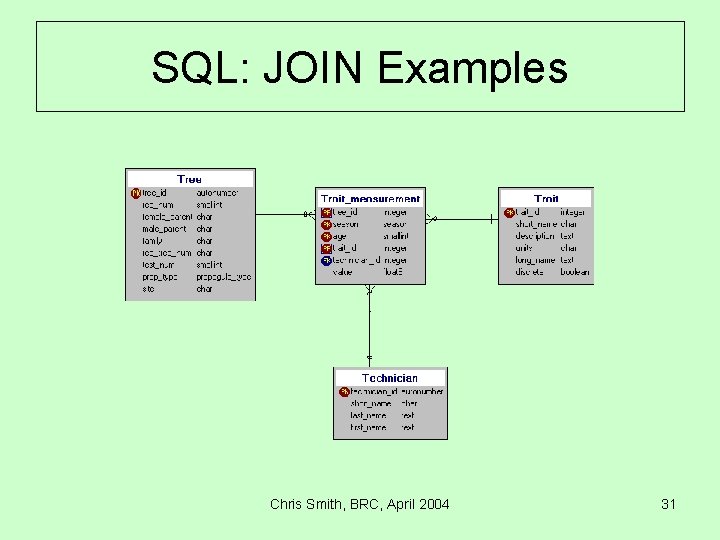

SQL: JOIN Examples Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 31

SQL: JOIN Examples • SELECT COUNT(*) FROM trait_measurement m, technician c WHERE m. technician_id = c. technician_id • SELECT COUNT(*) FROM trait_measurement m LEFT JOIN technician c ON m. technician_id = c. technician_id • SELECT COUNT(*) FROM trait_measurement m FULL JOIN technician c ON m. technician_id = c. technician_id Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 32

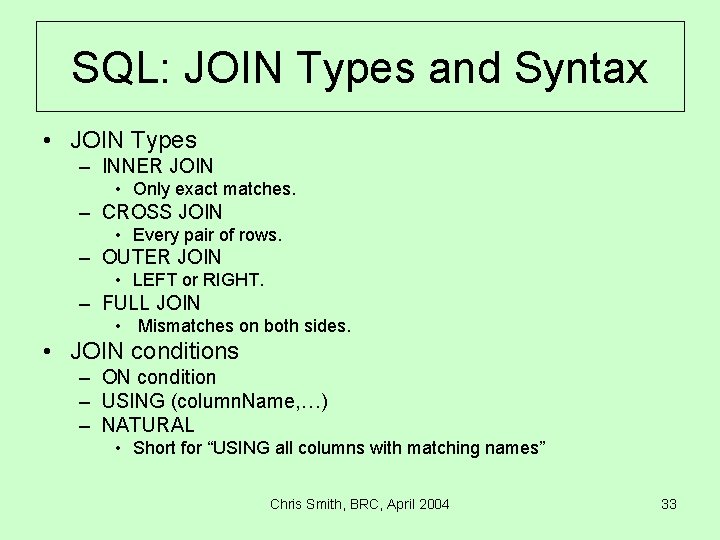

SQL: JOIN Types and Syntax • JOIN Types – INNER JOIN • Only exact matches. – CROSS JOIN • Every pair of rows. – OUTER JOIN • LEFT or RIGHT. – FULL JOIN • Mismatches on both sides. • JOIN conditions – ON condition – USING (column. Name, …) – NATURAL • Short for “USING all columns with matching names” Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 33

![SQL: UNION, EXCEPT, INTERSECT • (SELECT …) UNION [ALL] (SELECT …) • (SELECT …) SQL: UNION, EXCEPT, INTERSECT • (SELECT …) UNION [ALL] (SELECT …) • (SELECT …)](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/13e57dc6b68e01a008b9eea417a65e2c/image-34.jpg)

SQL: UNION, EXCEPT, INTERSECT • (SELECT …) UNION [ALL] (SELECT …) • (SELECT …) EXCEPT [ALL] (SELECT …) • (SELECT …) INTERSECT [ALL] (SELECT …) – INTERSECT is supported by Postgre. SQL, but not My. SQL (no big deal). • Results of SELECTs must match. • Returns table consisting of distinct results from both SELECTs, unless ALL is specified. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 34

SQL: LIMIT and OFFSET • Sometimes we want to limit the number of results returned by a query. • Especially useful on web sites for dividing many result rows between pages. • SELECT … LIMIT n OFFSET m • Not always supported: but both My. SQL and Postgre. SQL have it. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 35

Other Functions • SQL allows other functions in SELECT statements. • Highly dependent on the particular RDBMS being used. • Some standard ones: – – – CURRENT_DATE CURRENT_TIME SUBSTRING || (string concatenation) LOWER, UPPER Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 36

![SQL: INSERT • INSERT INTO table_name [(column_list)] VALUES (value_list) • INSERT INTO table_name [(column_list)] SQL: INSERT • INSERT INTO table_name [(column_list)] VALUES (value_list) • INSERT INTO table_name [(column_list)]](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/13e57dc6b68e01a008b9eea417a65e2c/image-37.jpg)

SQL: INSERT • INSERT INTO table_name [(column_list)] VALUES (value_list) • INSERT INTO table_name [(column_list)] SELECT … • Column_list is optional, but if not provided you must give values for all columns. – Defaults can be specified when the table is created. • Second form allows moving data from table to table. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 37

SQL: UPDATE • UPDATE table_name SET col 1 = val 1 [, col 2 = val 2 …] [WHERE condition] • In general cannot UPDATE based on data in other tables. – Both My. SQL and Postgre. SQL provide an extension to allow this. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 38

![SQL: DELETE • DELETE FROM table_name [WHERE condition] • (Too) easy to delete everything SQL: DELETE • DELETE FROM table_name [WHERE condition] • (Too) easy to delete everything](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/13e57dc6b68e01a008b9eea417a65e2c/image-39.jpg)

SQL: DELETE • DELETE FROM table_name [WHERE condition] • (Too) easy to delete everything from a table. • In general cannot DELETE based on data in other tables. – My. SQL provides an extension to allow this. – Postgre. SQL does not. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 39

SQL: Data Definition Language • Statements: – CREATE • TABLE, VIEW, INDEX – ALTER • TABLE – DROP • TABLE, VIEW, INDEX Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 40

![SQL: CREATE TABLE • CREATE TABLE ({column_name data_type [DEFAULT value] [, …]} [, PRIMARY SQL: CREATE TABLE • CREATE TABLE ({column_name data_type [DEFAULT value] [, …]} [, PRIMARY](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/13e57dc6b68e01a008b9eea417a65e2c/image-41.jpg)

SQL: CREATE TABLE • CREATE TABLE ({column_name data_type [DEFAULT value] [, …]} [, PRIMARY KEY (column_list)]) • Simplified! – Integrity mechanisms not shown. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 41

![SQL Numeric Data Types • Exact numeric types – NUMERIC [(precision[, scale])] – DECIMAL SQL Numeric Data Types • Exact numeric types – NUMERIC [(precision[, scale])] – DECIMAL](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/13e57dc6b68e01a008b9eea417a65e2c/image-42.jpg)

SQL Numeric Data Types • Exact numeric types – NUMERIC [(precision[, scale])] – DECIMAL [(precision[, scale])] • DECIMAL(5, 2) means 999. 99 – INTEGER (INT) – SMALLINT – BIGINT • Approximate numeric types – FLOAT [(precision)] – REAL – DOUBLE PRECISION Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 42

SQL Character Types • CHAR(length) – Short form of CHARACTER • VARCHAR(length) – Short form of CHARACTER VARYING • Postgre. SQL allows TEXT type for “long” character data fields. • My. SQL has TINYTEXT, MEDIUMTEXT and LONGTEXT types! Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 43

![SQL Date and Time Types • • DATE TIME [WITH TIME ZONE] TIMESTAMP [WITH SQL Date and Time Types • • DATE TIME [WITH TIME ZONE] TIMESTAMP [WITH](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/13e57dc6b68e01a008b9eea417a65e2c/image-44.jpg)

SQL Date and Time Types • • DATE TIME [WITH TIME ZONE] TIMESTAMP [WITH TIME ZONE] INTERVAL – Not available in My. SQL. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 44

SQL: CREATE VIEW • A view is a “virtual table”. • Not available in My. SQL 4. – Supposed to be coming in version 5. • Created as needed from a SELECT statement given when the view is defined. • CREATE VIEW AS SELECT … – Simplified! • Often used to restrict access to a table (by hiding some columns or rows). • Also used to “hide” complex queries in the database (rather than repeating them in code). Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 45

SQL: CREATE INDEX • Used to enhance performance of SELECT’s (may slow down INSERT’s since index must be updated). • Index columns used for frequently for lookup. • Primary key columns are usually automatically indexed. • CREATE INDEX index_name ON table_name (col 1 [, …]) Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 46

SQL: DROP • DROP is used to remove tables, views and indices from the system. – DROP TABLE table_name – DROP INDEX index_name – DROP VIEW view_name • For a table: all data in the table will be lost. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 47

Creating a Database • Creation of an entire database tends to depend on the RDBMS being used. • Usually allow multiple named databases to be accessed through a single instance of a database server. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 48

When to Use an RDBMS? • Good for large amounts of data. – Indexing capabilities. • Frequent updates: – Insertions of new values • Many different views of the data wanted. • Associations between different entities (foreign keys). • Data integrity. – Constraints. – Transactions. • ACID = Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability. • Integration with other systems e. g. web pages. • Sharing data between users. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 49

Plain Old Text Files • Can be perfect (even for largish amounts of data). • Easier to hand over to someone else. – Don’t have to say “first install database X”. • Not great for updates to existing values. • No integrity checks (can be made in code). Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 50

SAS Datasets • • SAS allows SQL queries on its datasets. Datasets can be merged (= joined). Probably not indexed (speed). Very good for personal analysis of data, less good for shared data. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 51

What We Have Not Covered • Transactions and referential integrity – Very important in systems that are frequently updated. – Less important in “read only” or infrequently updated databases. – Add greatly to the complexity of RDBMS’s. • SQL Stored procedures. • Security. • How to get data into the database from external sources. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 52

References • “Database Systems”, Connolly and Begg, Addison Wesley, 3 rd Edition, 2002 • “Postgre. SQL”, Douglas and Douglas, SAMS Publishing, 2003 • “My. SQL”, Du. Bois, SAMS Publishing, 2 nd Edition, 2003 • http: //www. postgresql. org – Recommended website for further reading. • http: //www. mysql. com Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 53

Summary • RDBMS’s are good at manipulating data. • Need to decide if you need one. • SQL is the standard language. – Standard up to a point. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 54

Relational Databases and SQL Session 2 Installing and Using a Database. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004

Outline: Example Systems 1. Choose My. SQL or Postgre. SQL. • • Or both if you want to compare them. They will happily co-exist on the same machine. 2. System installation and setup. 3. Command-line interaction with the chosen system. • • Creating a new database (if necessary). Creating some example tables. 4. Graphical tools. 5. User rights assignment. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 56

Operating Systems • The lab we are using has Windows-based laptops. So we will be installing these systems on Windows. • Both databases run on a variety of Unixbased systems. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 57

Resources • ftp: //statgen. ncsu. edu/pub/chris/sql_course • Course CD Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 58

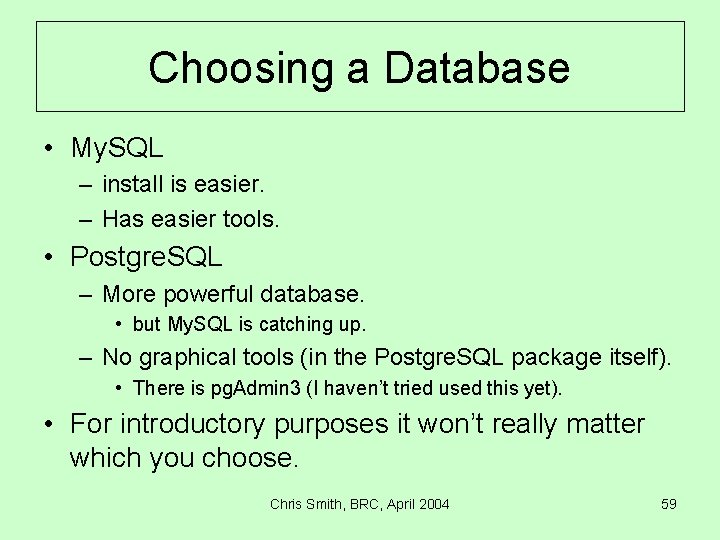

Choosing a Database • My. SQL – install is easier. – Has easier tools. • Postgre. SQL – More powerful database. • but My. SQL is catching up. – No graphical tools (in the Postgre. SQL package itself). • There is pg. Admin 3 (I haven’t tried used this yet). • For introductory purposes it won’t really matter which you choose. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 59

Recommendation is… • My. SQL Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 60

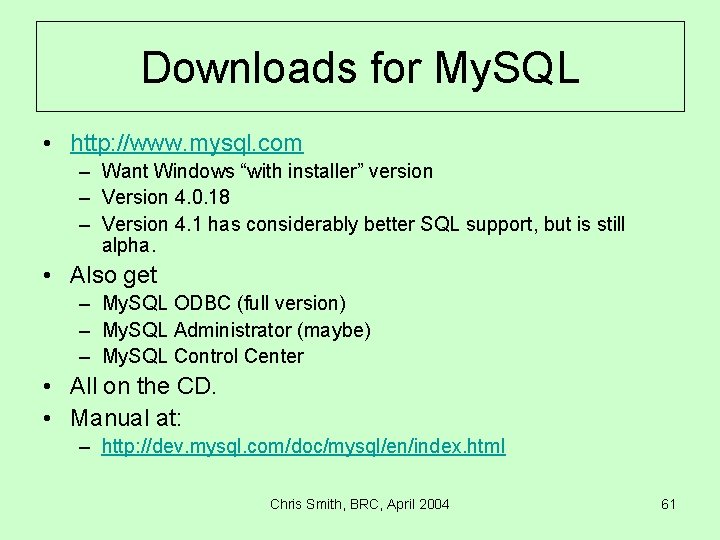

Downloads for My. SQL • http: //www. mysql. com – Want Windows “with installer” version – Version 4. 0. 18 – Version 4. 1 has considerably better SQL support, but is still alpha. • Also get – My. SQL ODBC (full version) – My. SQL Administrator (maybe) – My. SQL Control Center • All on the CD. • Manual at: – http: //dev. mysql. com/doc/mysql/en/index. html Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 61

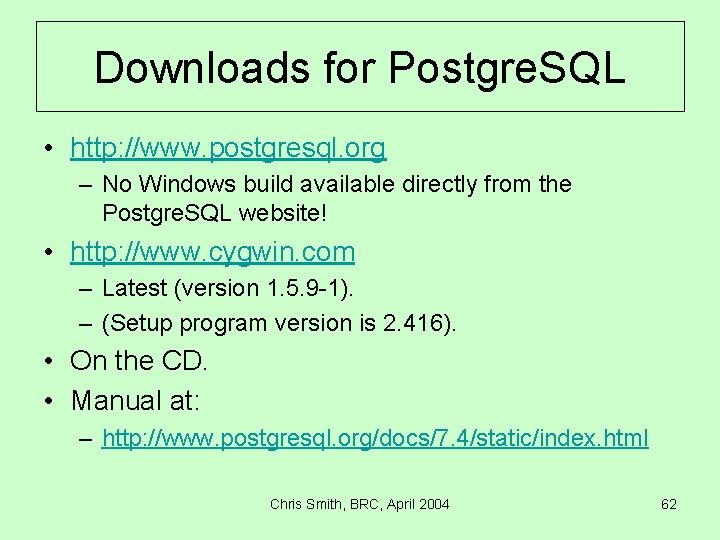

Downloads for Postgre. SQL • http: //www. postgresql. org – No Windows build available directly from the Postgre. SQL website! • http: //www. cygwin. com – Latest (version 1. 5. 9 -1). – (Setup program version is 2. 416). • On the CD. • Manual at: – http: //www. postgresql. org/docs/7. 4/static/index. html Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 62

Command Line Interfaces • For both My. SQL and Postgre. SQL we will be using command line interfaces. They are call mysql and psql respectively. • Both interfaces give you a command line prompt. • In both cases you can type some commands (e. g. help) and hit the enter key. • You can also type SQL statements terminated with a semi-colon. – If you do not give the semi-colon the application will assume that you are going to type more and will change the prompt slightly to indicate this. (Try it out. ) Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 63

My. SQL Installation Plan • Install the program. – Using the supplied installer. • • • Check that it runs OK. Stop the server. Perform some extra setup. Restart the server. Try it out. Complete configuration. – Create a test database. • Install supplementary programs. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 64

My. SQL Installation: Simple Version • Really easy! • Read the printed instructions for alternatives. • On the CD directory mysqlmysql-4. 0. 18 -win contains what you need - run setup. exe. • Choose “Typical” installation. • Accept default directory. – May want to use a non-default directory if you have limited space on your C drive. – If so, you need to create an options file for My. SQL (use Notepad). Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 65

Running My. SQL the first time • Open a command-line window. • Change directory to c: mysqlbin. (Or your installation directory. ) • Choose a server(!) – mysqld-max-nt recommended. • Run “mysqld-max-nt --console” – “console” option directs messages to the screen. – Should see a number of messages ending in: mysqld: ready for connections Version: '4. 0. 14 -log' socket: '' port: 3306 • It’s running! Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 66

Stopping My. SQL • Open a new command-line window. • In c: mysqlbin run: – “mysqladmin –u root shutdown” • Server will stop. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 67

Restarting the My. SQL server • • Open a command-line window. Change directory to c: mysqlbin. Run “mysqld-max-nt”. Info and errors will be logged to c: mysqldata<machine_name>. err Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 68

Running My. SQL as a service • A Windows service starts whenever the system is booted. – No need for a user to log on. – Correct thing to do on a production server. – On a personal machine it’s up to you. • From a command-line: – mysqld-max-nt –install • Adds the service. • Use standard Windows tools to control the service. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 69

Running My. SQL from a Command Line • Command-line interface is mysql –u <username> <dbname> mysql –p –u <username> <dbname> • -p means “use password”. • You will get a prompt: mysql> Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 70

Security Issue • My. SQL opens a TCP/IP port (3306 by default) on your machine. • Hackers will try to attack this port – just like they do any other. • Run a firewall! – Locally • E. g. Zone. Alarm from Zone. Labs • Try the free version. – On a router. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 71

Securing your server • After installation anyone can connect and have root user privileges (within the database). • Change directory to c: mysqlbin. • To give root a password: – Run “mysql –u root”. – At the “mysql>” prompt execute: SET PASSWORD FOR ‘root’@’localhost’ = PASSWORD(‘rootpass’); SET PASSWORD FOR ‘root’@’%’ = PASSWORD(‘rootpass’); QUIT • From now on you will need “mysql –p –u root” to start mysql. • To remove anonymous users: – Restart mysql with “mysql –p –u root”. – At the “mysql>” prompt execute: USE mysql; DELETE FROM user WHERE user = ‘’; DELETE FROM db WHERE user = ‘’; FLUSH PRIVILEGES; Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 72

Create your own database • Create a user to be the administrator of the new database. (Not absolutely necessary, but recommended. ) mysql> GRANT ALL ON testdb. * TO ‘testroot’@’localhost’ IDENTIFIED BY ‘xxxx’; – ‘xxxx’ is the user’s password. • Create the new database: mysql> CREATE DATABASE testdb; • Restart mysql with the new user: mysql –p –u testdb • Switch to the new database: mysql> use testdb; Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 73

My. ODBC Installation • From a command line: – Run My. ODBC-3. 51. 06. exe – No questions asked! Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 74

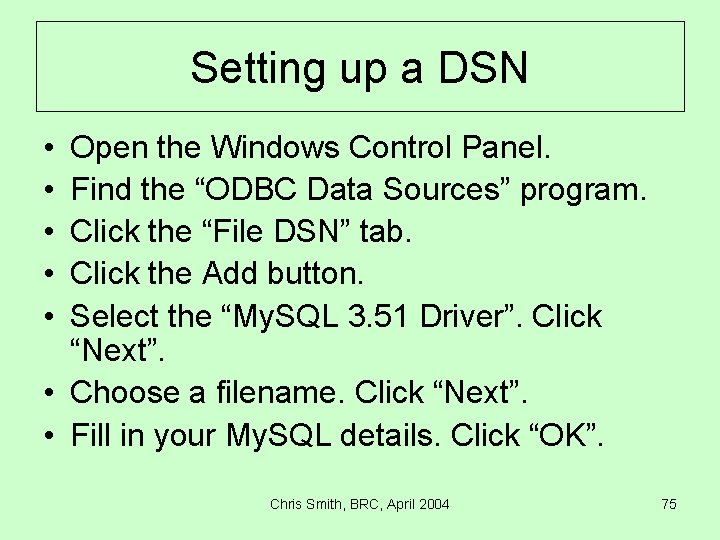

Setting up a DSN • • • Open the Windows Control Panel. Find the “ODBC Data Sources” program. Click the “File DSN” tab. Click the Add button. Select the “My. SQL 3. 51 Driver”. Click “Next”. • Choose a filename. Click “Next”. • Fill in your My. SQL details. Click “OK”. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 75

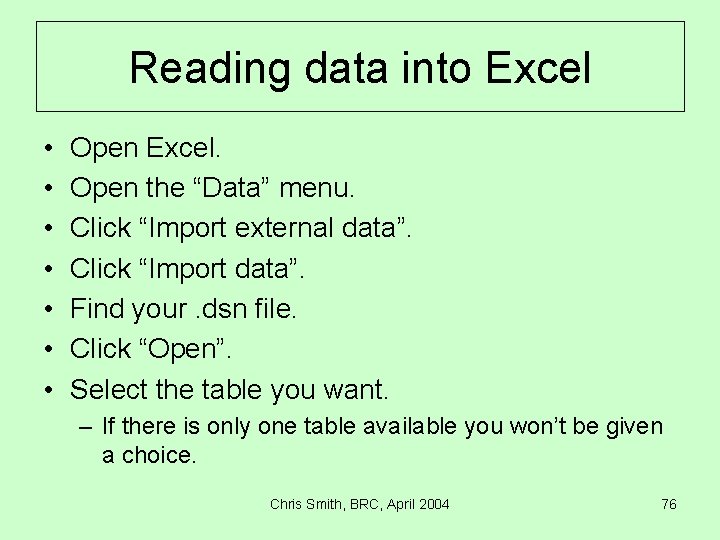

Reading data into Excel • • Open Excel. Open the “Data” menu. Click “Import external data”. Click “Import data”. Find your. dsn file. Click “Open”. Select the table you want. – If there is only one table available you won’t be given a choice. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 76

Installing My. SQL Administrator • Optional. • “Alpha” software – Not yet fully tested. – May contain serious bugs. • GUI administration tool. • Run “setup. exe” from mysql-administrator 1. 0. 3 -alpha-win. • No difficult questions. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 77

Using My. SQL Administrator • Run it from “Start”, “All Programs”, “My. SQL”. • Allows: – Stopping and starting My. SQL. – User administration. – Backup and restore. –… • Worth a look if you are managing a server. • Worth trying if you prefer a GUI. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 78

Installing the My. SQL Control Center • Run setup. exe from mysqlcc-0. 9. 4 -win 32. • Can either install translations or trun installation off. • Run the control center from “Start”, “All programs”, “My. SQL Control Center”. – Slightly annoying that it puts it in a separate menu entry from the My. SQL Administrator. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 79

Using the My. SQL Control Center • • Start it up. “Register” a new server. Use “localhost” as the host name. User name can be “root”. Enter your password. Click “Test” to make sure it’s OK. Click “Add”. Select a database and click “SQL”, or double click a table name (and then click “SQL”). – Lets you enter queries and see results. – You can update the values in the database by editing them. • Looks like an OK tool for playing with SQL. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 80

Postgre. SQL Installation Plan • Postgre. SQL is not a “native” Windows application. – Needs some Unix functions. – But there’s nothing magic about Unix functions. – An upcoming version will have a native Windows binary included. (version 7. 5 or 8. ) • Postgre. SQL can be run under Cygwin. – A set of libraries for Windows that implement Unix functions. • Plan is to install Cygwin – It includes a build of Postgre. SQL. – It also includes a version of perl. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 81

Installing Cygwin (and Postgres) • • • Run setup. exe from the cygwin directory. Choose “install from local directory”. Choose an installation directory (default is c: cygwin). When asked to specify the local package directory click browse and choose the long name beginning with http … Click Next. Under “Admin” check cygrunsrv. Under “Databases” check postgresql. Under “Devel” make sure that cygipc is checked. When installation completes choose to have an icon placed on the desktop or in the start menu. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 82

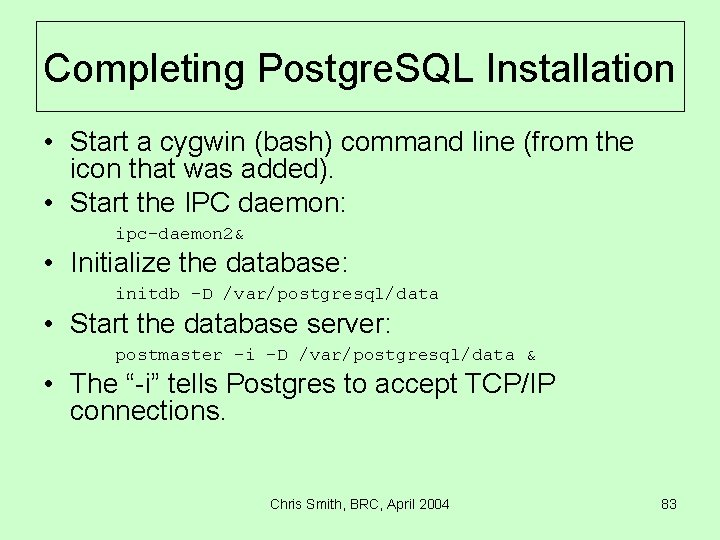

Completing Postgre. SQL Installation • Start a cygwin (bash) command line (from the icon that was added). • Start the IPC daemon: ipc-daemon 2& • Initialize the database: initdb –D /var/postgresql/data • Start the database server: postmaster –i –D /var/postgresql/data & • The “-i” tells Postgres to accept TCP/IP connections. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 83

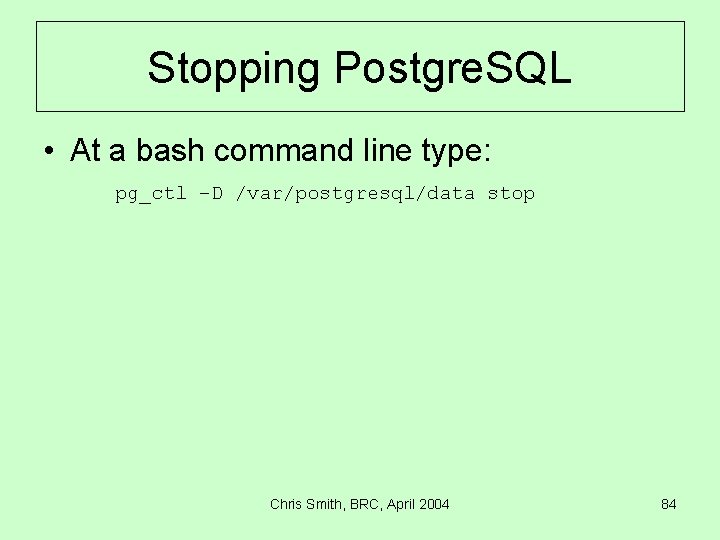

Stopping Postgre. SQL • At a bash command line type: pg_ctl –D /var/postgresql/data stop Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 84

Running Postgre. SQL as a service • More complex than for My. SQL. • Need to get ownership of files correct. • Uses cygrunsrv program from cygwin installation. • Read the installation notes! Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 85

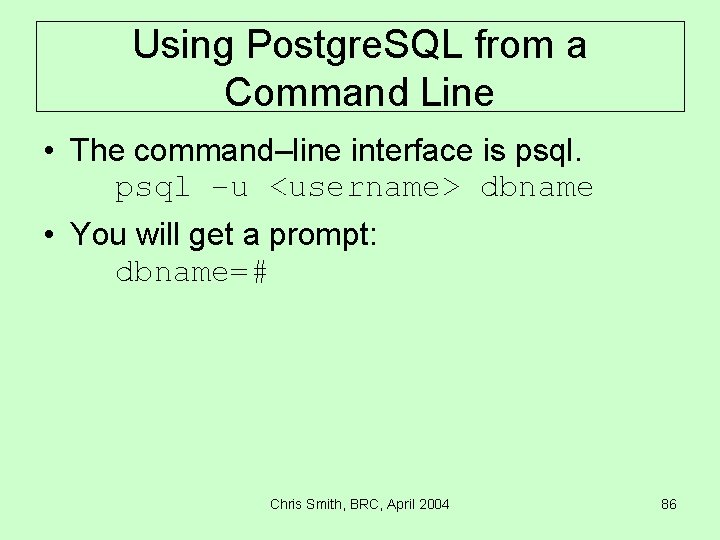

Using Postgre. SQL from a Command Line • The command–line interface is psql –u <username> dbname • You will get a prompt: dbname=# Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 86

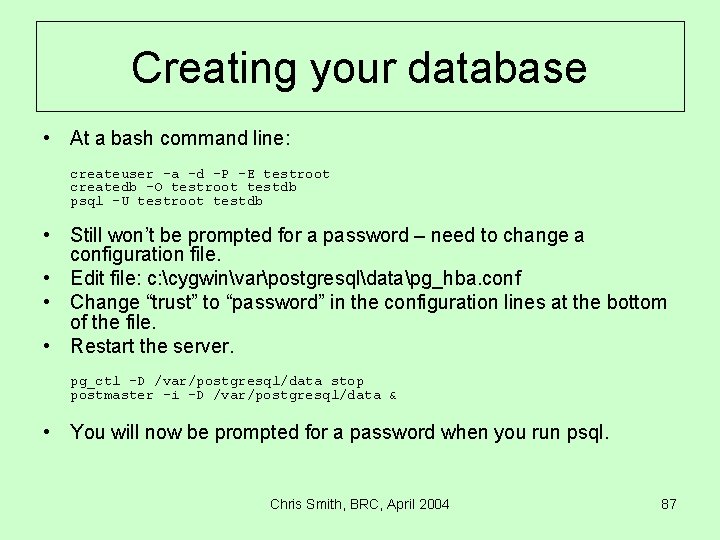

Creating your database • At a bash command line: createuser –a –d –P –E testroot createdb –O testroot testdb psql –U testroot testdb • Still won’t be prompted for a password – need to change a configuration file. • Edit file: c: cygwinvarpostgresqldatapg_hba. conf • Change “trust” to “password” in the configuration lines at the bottom of the file. • Restart the server. pg_ctl –D /var/postgresql/data stop postmaster –i –D /var/postgresql/data & • You will now be prompted for a password when you run psql. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 87

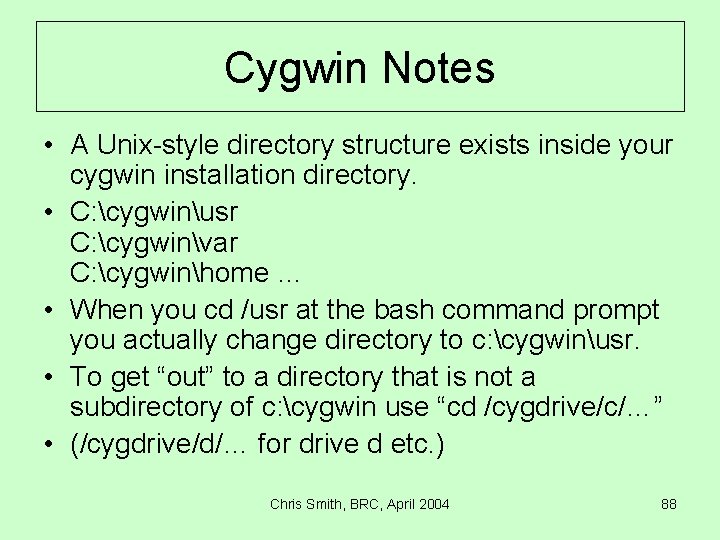

Cygwin Notes • A Unix-style directory structure exists inside your cygwin installation directory. • C: cygwinusr C: cygwinvar C: cygwinhome … • When you cd /usr at the bash command prompt you actually change directory to c: cygwinusr. • To get “out” to a directory that is not a subdirectory of c: cygwin use “cd /cygdrive/c/…” • (/cygdrive/d/… for drive d etc. ) Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 88

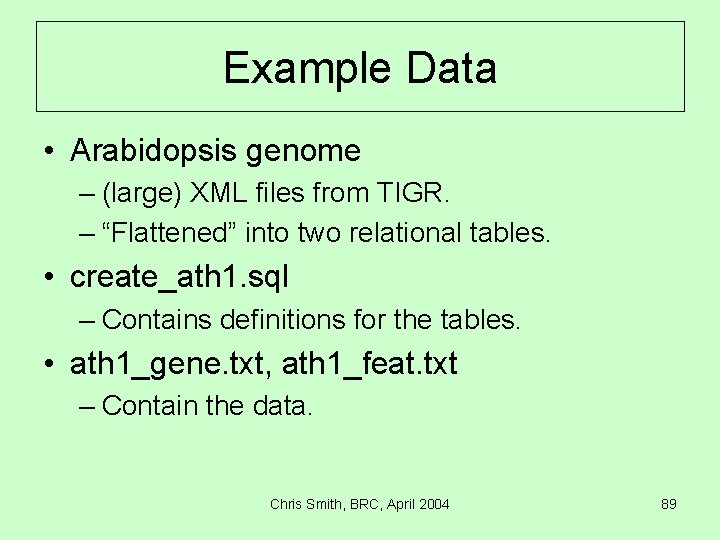

Example Data • Arabidopsis genome – (large) XML files from TIGR. – “Flattened” into two relational tables. • create_ath 1. sql – Contains definitions for the tables. • ath 1_gene. txt, ath 1_feat. txt – Contain the data. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 89

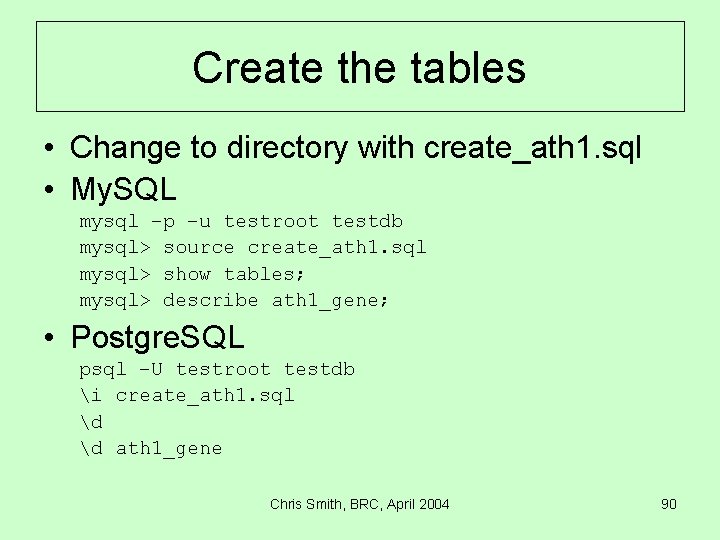

Create the tables • Change to directory with create_ath 1. sql • My. SQL mysql –p –u testroot testdb mysql> source create_ath 1. sql mysql> show tables; mysql> describe ath 1_gene; • Postgre. SQL psql –U testroot testdb i create_ath 1. sql d d ath 1_gene Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 90

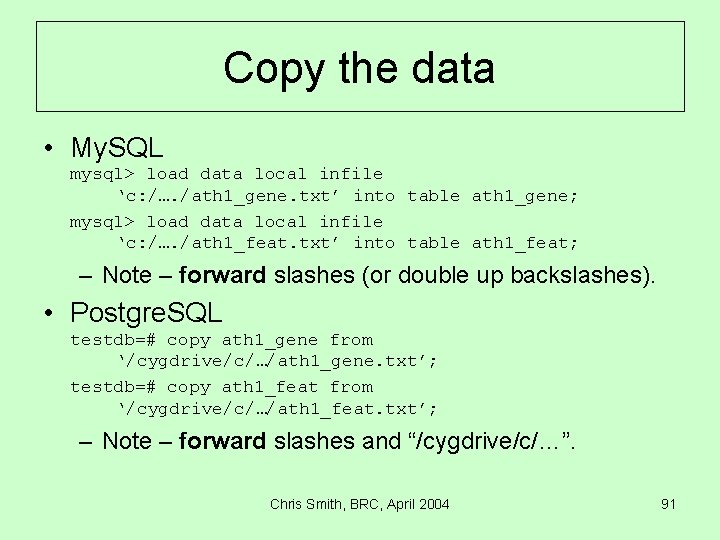

Copy the data • My. SQL mysql> load data local infile ‘c: /…. /ath 1_gene. txt’ into table ath 1_gene; mysql> load data local infile ‘c: /…. /ath 1_feat. txt’ into table ath 1_feat; – Note – forward slashes (or double up backslashes). • Postgre. SQL testdb=# copy ath 1_gene from ‘/cygdrive/c/…/ath 1_gene. txt’; testdb=# copy ath 1_feat from ‘/cygdrive/c/…/ath 1_feat. txt’; – Note – forward slashes and “/cygdrive/c/…”. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 91

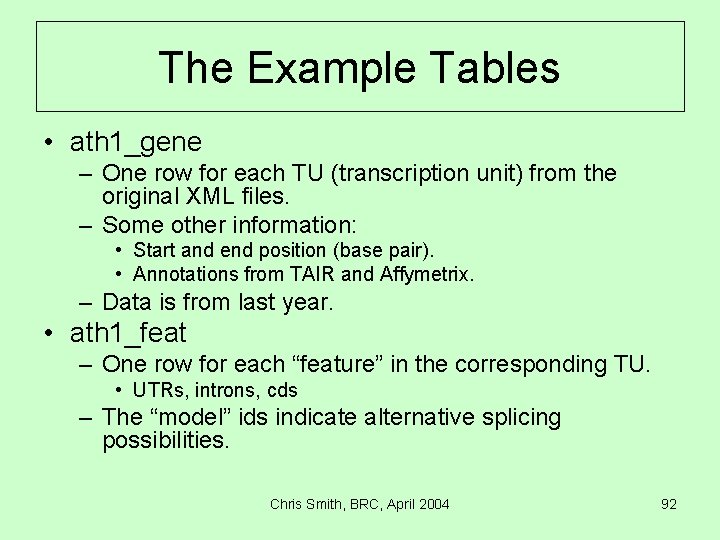

The Example Tables • ath 1_gene – One row for each TU (transcription unit) from the original XML files. – Some other information: • Start and end position (base pair). • Annotations from TAIR and Affymetrix. – Data is from last year. • ath 1_feat – One row for each “feature” in the corresponding TU. • UTRs, introns, cds – The “model” ids indicate alternative splicing possibilities. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 92

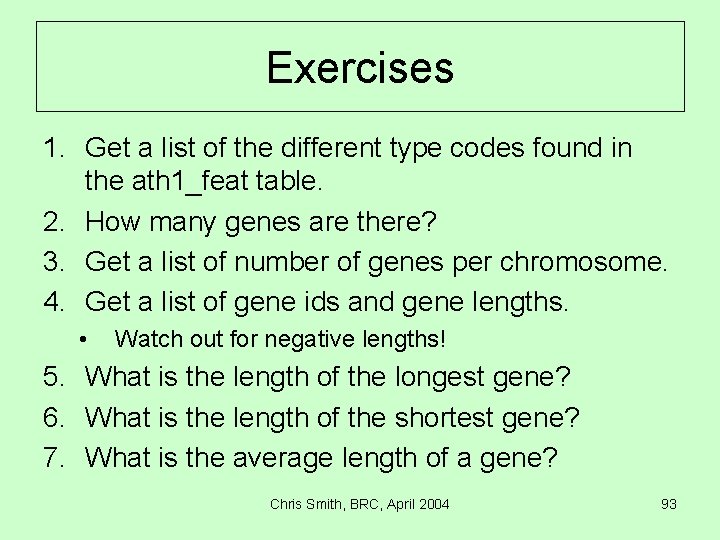

Exercises 1. Get a list of the different type codes found in the ath 1_feat table. 2. How many genes are there? 3. Get a list of number of genes per chromosome. 4. Get a list of gene ids and gene lengths. • Watch out for negative lengths! 5. What is the length of the longest gene? 6. What is the length of the shortest gene? 7. What is the average length of a gene? Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 93

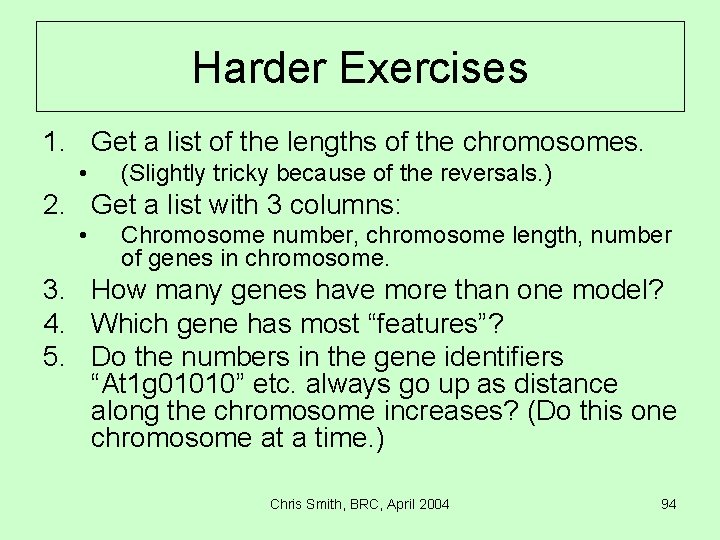

Harder Exercises 1. Get a list of the lengths of the chromosomes. • (Slightly tricky because of the reversals. ) 2. Get a list with 3 columns: • Chromosome number, chromosome length, number of genes in chromosome. 3. How many genes have more than one model? 4. Which gene has most “features”? 5. Do the numbers in the gene identifiers “At 1 g 01010” etc. always go up as distance along the chromosome increases? (Do this one chromosome at a time. ) Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 94

Solutions to exercises 1. 2. 3. 4. SELECT DISTINCT type FROM ath 1_feat; SELECT COUNT(*) FROM ath 1_gene; SELECT chromosome, COUNT(*) FROM ath 1_gene GROUP BY chromosome; SELECT tair_id, end_bp – start_bp FROM ath 1_gene; • • 5. 6. 7. Use ABS() to get rid of the negative values. Reverse direction is indicated by the start/end values being reversed. SELECT tair_id, ABS(end_bp – start_bp) AS len FROM ath 1_gene ORDER BY len DESC LIMIT 1; SELECT tair_id, ABS(end_bp – start_bp) AS len FROM ath 1_gene ORDER BY len ASC LIMIT 1; SELECT AVG(ABS(end_bp – start_bp)) FROM ath 1_gene; Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 95

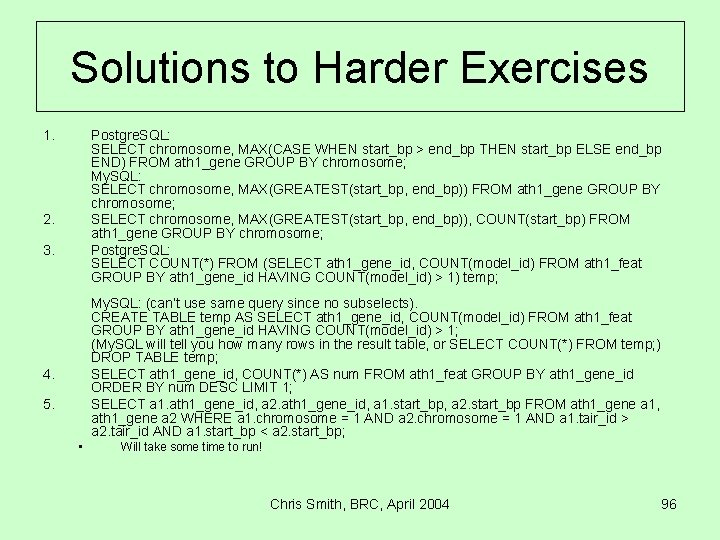

Solutions to Harder Exercises 1. Postgre. SQL: SELECT chromosome, MAX(CASE WHEN start_bp > end_bp THEN start_bp ELSE end_bp END) FROM ath 1_gene GROUP BY chromosome; My. SQL: SELECT chromosome, MAX(GREATEST(start_bp, end_bp)) FROM ath 1_gene GROUP BY chromosome; SELECT chromosome, MAX(GREATEST(start_bp, end_bp)), COUNT(start_bp) FROM ath 1_gene GROUP BY chromosome; Postgre. SQL: SELECT COUNT(*) FROM (SELECT ath 1_gene_id, COUNT(model_id) FROM ath 1_feat GROUP BY ath 1_gene_id HAVING COUNT(model_id) > 1) temp; 2. 3. My. SQL: (can’t use same query since no subselects). CREATE TABLE temp AS SELECT ath 1_gene_id, COUNT(model_id) FROM ath 1_feat GROUP BY ath 1_gene_id HAVING COUNT(model_id) > 1; (My. SQL will tell you how many rows in the result table, or SELECT COUNT(*) FROM temp; ) DROP TABLE temp; SELECT ath 1_gene_id, COUNT(*) AS num FROM ath 1_feat GROUP BY ath 1_gene_id ORDER BY num DESC LIMIT 1; SELECT a 1. ath 1_gene_id, a 2. ath 1_gene_id, a 1. start_bp, a 2. start_bp FROM ath 1_gene a 1, ath 1_gene a 2 WHERE a 1. chromosome = 1 AND a 2. chromosome = 1 AND a 1. tair_id > a 2. tair_id AND a 1. start_bp < a 2. start_bp; 4. 5. • Will take some time to run! Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 96

Relational Databases and SQL Session 3 Script Languages and Database Access Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004

Script Languages and Database Access 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Tidy-up from previous sessions. Perl and the DBI. PHP and the Pear DB. Example script. Users and User Rights. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 98

Errata • Session 1: JOIN types differ on their treatment of mismatches (not NULLs as written on the slide). • Session 2: The My. SQL ODBC driver will let you update data through Microsoft Access. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 99

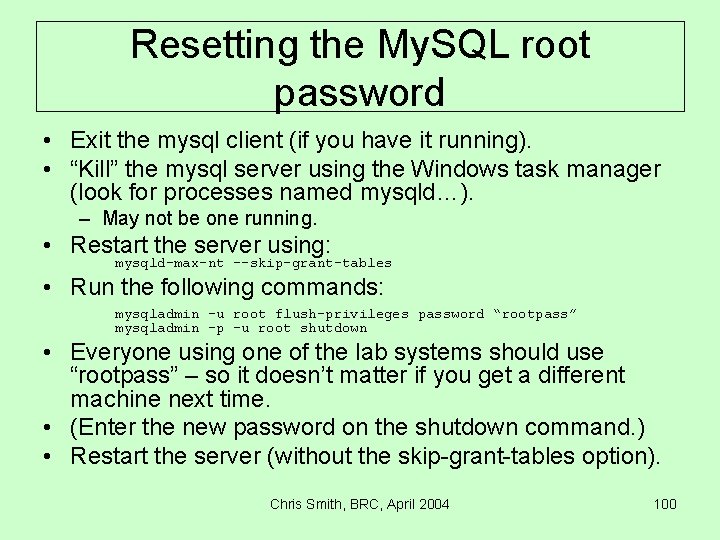

Resetting the My. SQL root password • Exit the mysql client (if you have it running). • “Kill” the mysql server using the Windows task manager (look for processes named mysqld…). – May not be one running. • Restart the server using: mysqld-max-nt --skip-grant-tables • Run the following commands: mysqladmin –u root flush-privileges password “rootpass” mysqladmin –p –u root shutdown • Everyone using one of the lab systems should use “rootpass” – so it doesn’t matter if you get a different machine next time. • (Enter the new password on the shutdown command. ) • Restart the server (without the skip-grant-tables option). Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 100

Disallowing network connections in My. SQL • When starting the server use these options: --skip-networking --enable-named-pipes Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 101

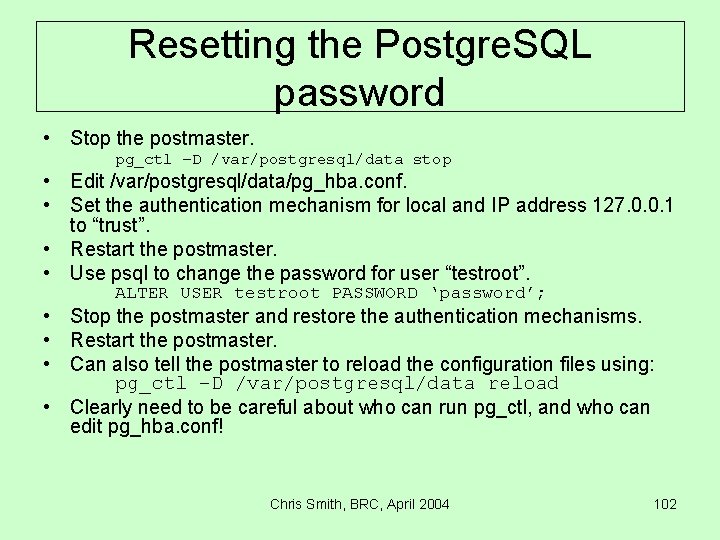

Resetting the Postgre. SQL password • Stop the postmaster. pg_ctl –D /var/postgresql/data stop • Edit /var/postgresql/data/pg_hba. conf. • Set the authentication mechanism for local and IP address 127. 0. 0. 1 to “trust”. • Restart the postmaster. • Use psql to change the password for user “testroot”. ALTER USER testroot PASSWORD ‘password’; • Stop the postmaster and restore the authentication mechanisms. • Restart the postmaster. • Can also tell the postmaster to reload the configuration files using: pg_ctl –D /var/postgresql/data reload • Clearly need to be careful about who can run pg_ctl, and who can edit pg_hba. conf! Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 102

Poll • Who would like me to go through the solutions to the exercises and explain why/how/if they work? Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 103

Script Languages • Interpreted (rather than compiled) – Write it and try it. • Dynamically typed – Don’t have to declare the type of a variable. – May not have to declare variables at all. • Perl, PHP, Python, Ruby, Java. Script, … Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 104

Perl • • Popular scripting language. Somewhat C-like. A lot of quirks. A lot of add-on modules. – Bio. Perl (http: //www. bioperl. org) Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 105

Perl Information • Get Perl info and packages from: http: //cpan. org • There is an Apache module mod_perl allowing efficient execution of Perl scripts within a web server. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 106

Installing Active. State Perl • Will use Active. State Perl with My. SQL – Built for Windows. – Nice installer. • Use the. msi file: Active. Perl-5. 8. 3. 809 -MSWin 32 -x 86. msi – On Windows 98 you may need to install the Microsoft Installer. On XP or 2000 it is already present. • Have the installer add the Perl binary directory to your path. • Install takes some time (but you just have to sit and wait). Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 107

Check your install • From a command line type: perl -v • Should get version information for Active. State Perl v 5. 8. 3 binary build 809. • Type: perl hello. pl • hello. pl is in course downloads (but is very simple: print “Hello, worldn”; ). • Should get “Hello, world” printed in response. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 108

Installing the Perl DBI • We will use the Perl DBI (Database Interface). • With Active. State Perl there is a “package management” tool “ppm”. • At a Windows command prompt enter: ppm • You will get a ppm> prompt. • Type: install DBI • You should get some lines of information ending with something like “succesfully installed”. • Then type: install DBD-mysql • You should get more lines of information and another “successfully installed” message. • Type “q” to quit from ppm. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 109

Testing the Perl DBI/My. SQL DBD • mysql_test. pl is in the downloaded course files (and on the CD). • Edit the mysql_test. pl file using Notepad (or another editor). • You will see lines of Perl code setting the database name, the user name and password. Check that these match your installation. • Make sure the My. SQL server is running. • At Windows command line type: perl mysql_test. pl • Should get 20 lines of results from the ath 1_gene table. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 110

Installing Cygwin Perl • You can also install a ready-built Perl through Cygwin. • Use this if you installed Postgre. SQL under Cygwin. • Start the Cygwin setup utility. • Click through to the package selection dialog. • Add perl (under interpreters). • Also add gcc and make (under “Devel” - they will be used to install the perl DBD for Postgre. SQL). Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 111

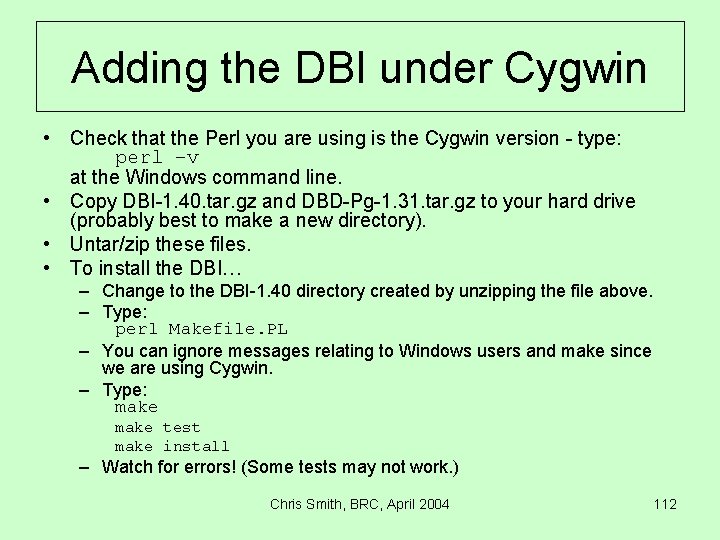

Adding the DBI under Cygwin • Check that the Perl you are using is the Cygwin version - type: perl –v at the Windows command line. • Copy DBI-1. 40. tar. gz and DBD-Pg-1. 31. tar. gz to your hard drive (probably best to make a new directory). • Untar/zip these files. • To install the DBI… – Change to the DBI-1. 40 directory created by unzipping the file above. – Type: perl Makefile. PL – You can ignore messages relating to Windows users and make since we are using Cygwin. – Type: make test make install – Watch for errors! (Some tests may not work. ) Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 112

Adding the Postgre. SQL DBD. • Untar/unzip the DBD-Pg-1. 31. tar. gz file. • Perform the same steps as for the DBI… perl Makefile. PL make test make install Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 113

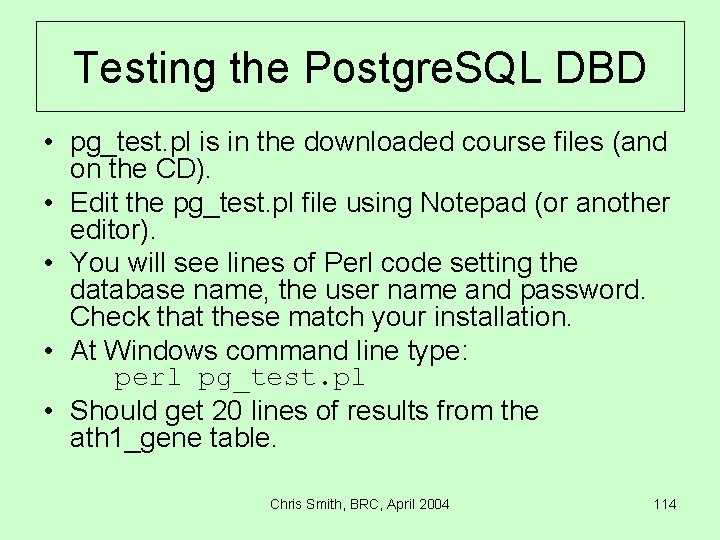

Testing the Postgre. SQL DBD • pg_test. pl is in the downloaded course files (and on the CD). • Edit the pg_test. pl file using Notepad (or another editor). • You will see lines of Perl code setting the database name, the user name and password. Check that these match your installation. • At Windows command line type: perl pg_test. pl • Should get 20 lines of results from the ath 1_gene table. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 114

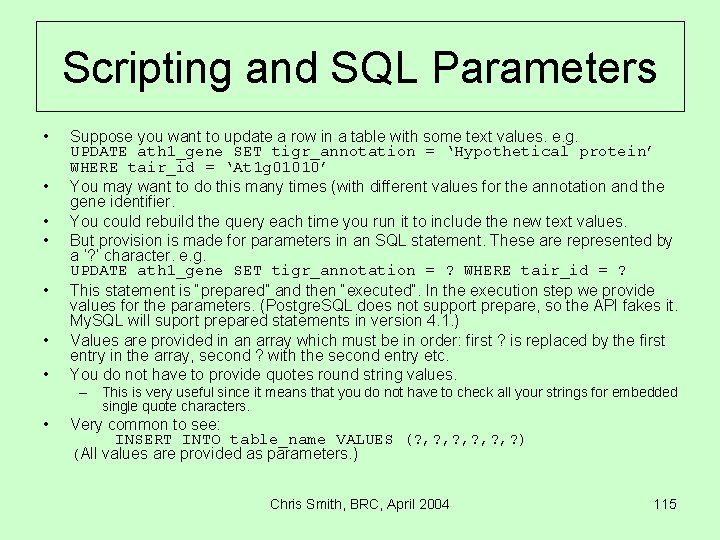

Scripting and SQL Parameters • • Suppose you want to update a row in a table with some text values. e. g. UPDATE ath 1_gene SET tigr_annotation = ‘Hypothetical protein’ WHERE tair_id = ‘At 1 g 01010’ You may want to do this many times (with different values for the annotation and the gene identifier. You could rebuild the query each time you run it to include the new text values. But provision is made for parameters in an SQL statement. These are represented by a ‘? ’ character. e. g. UPDATE ath 1_gene SET tigr_annotation = ? WHERE tair_id = ? This statement is “prepared” and then “executed”. In the execution step we provide values for the parameters. (Postgre. SQL does not support prepare, so the API fakes it. My. SQL will suport prepared statements in version 4. 1. ) Values are provided in an array which must be in order: first ? is replaced by the first entry in the array, second ? with the second entry etc. You do not have to provide quotes round string values. – This is very useful since it means that you do not have to check all your strings for embedded single quote characters. • Very common to see: INSERT INTO table_name VALUES (? , ? , ? , ? ) (All values are provided as parameters. ) Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 115

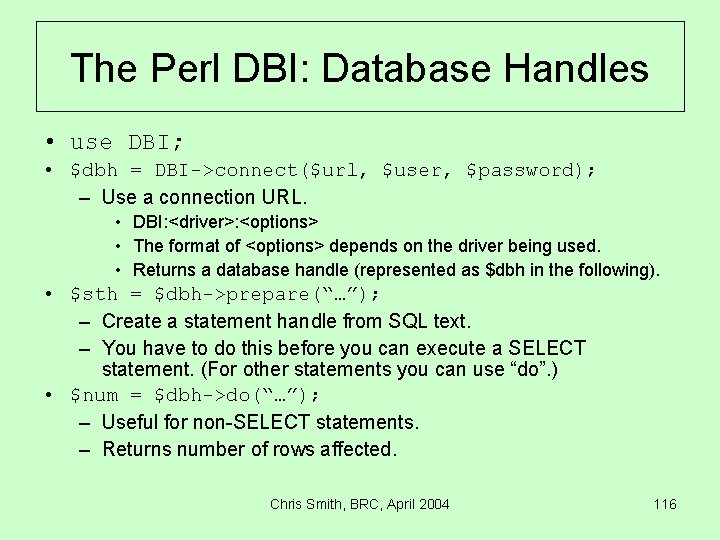

The Perl DBI: Database Handles • use DBI; • $dbh = DBI->connect($url, $user, $password); – Use a connection URL. • DBI: <driver>: <options> • The format of <options> depends on the driver being used. • Returns a database handle (represented as $dbh in the following). • $sth = $dbh->prepare(“…”); – Create a statement handle from SQL text. – You have to do this before you can execute a SELECT statement. (For other statements you can use “do”. ) • $num = $dbh->do(“…”); – Useful for non-SELECT statements. – Returns number of rows affected. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 116

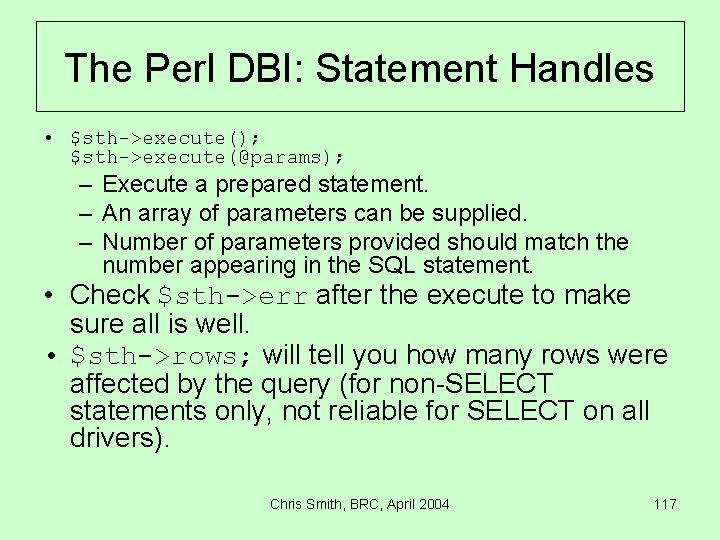

The Perl DBI: Statement Handles • $sth->execute(); $sth->execute(@params); – Execute a prepared statement. – An array of parameters can be supplied. – Number of parameters provided should match the number appearing in the SQL statement. • Check $sth->err after the execute to make sure all is well. • $sth->rows; will tell you how many rows were affected by the query (for non-SELECT statements only, not reliable for SELECT on all drivers). Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 117

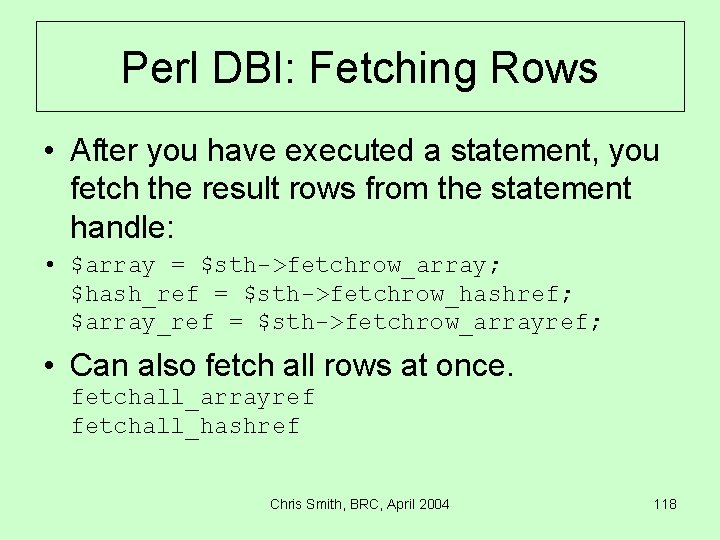

Perl DBI: Fetching Rows • After you have executed a statement, you fetch the result rows from the statement handle: • $array = $sth->fetchrow_array; $hash_ref = $sth->fetchrow_hashref; $array_ref = $sth->fetchrow_arrayref; • Can also fetch all rows at once. fetchall_arrayref fetchall_hashref Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 118

Perl DBI: Statement Done • After you have finished with a statement you should call “finish” to let the API release any resources associated with it. $sth->finish; Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 119

PHP • Very C/C++-like. – Easy to pick up if you know C. – Some similarities to Perl. – Fewer idiosyncrasies than Perl (in my opinion). • Replacing Perl for dynamic web sites. • Some sites use PHP for creating web pages and Perl for background applications. • Definitely easy to create small sites. Not so sure about large sites (no namespace support). • I like it (except for the fact that you still have to start every variable name with a ‘$’ sign, yuck!) Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 120

PHP Information • Downloads and documentation at: http: //www. php. net • There is an Apache module mod_php that lets PHP code run efficiently within Apache. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 121

Installing PHP • Use the “manual install” rather than the installer. (The installer only installs the CGI version. ) – We are not going to be talking about installing a web server. But the code we write in PHP would work just as well from within a web server. • Downloaded file is php-4. 3. 6 -Win 32. zip. • Unzip this file into C: . • You will get a directory named: c: php-4. 3. 6 -Win 32 • Consider renaming this to c: php for ease of use! Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 122

Installing PHP: Continued • In php 4 ts. dll must be in your path: – Put c: php into your path. – Alternative is to copy it to somewhere in the path e. g. C: windowssystem 32 • Also want C: phpcliphp. exe in our path. – Either copy it to C: php (if you put C: php in your path). – Or copy php. exe to C: windowssystem 32. – I renamed mine to phpcli. exe to distinguish it from the CGI version – php. exe. • Copy php. ini-recommended to C: windowsphp. ini – Note the name change! Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 123

Testing PHP • There is a file php_test. php in the download directory. • At a Windows command line type: php_test. php • Should get lots of information printed to the console. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 124

Pear DB • PHP has built-in interfaces to My. SQL and Postgre. SQL. • It also has an equivalent of the Perl DBI. This is the Pear DB module. • At a Windows command line, change directory to C: php and type: go-pear • Let the script update your ini file when it asks. • The My. SQL interface is active by default (on Windows). • The Postgre. SQL interface must be activated by uncommenting the following line in php. ini. ; extension=php_pgsql. dll – Delete the semi-colon to uncomment. • Must also make sure PHP can find the Postgre. SQL “extension” – set the value of the “extension_dir” option in php. ini to: c: phpextensions Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 125

Testing the Installation • In the download directory there are two files: pg_test. php and mysql_test. php. • Look in them to see that they are very similar to the Perl versions. • Run them from a Windows command line by typing (one of): php pg_test. php mysql_test. php Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 126

Pear DB: Database Handle • Similar to the Perl DBI database handle. • Look for details at: http: //pear. php. net • In general check for errors using: DB: : is. Error($val); – Where $val is the result from any Pear DB call. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 127

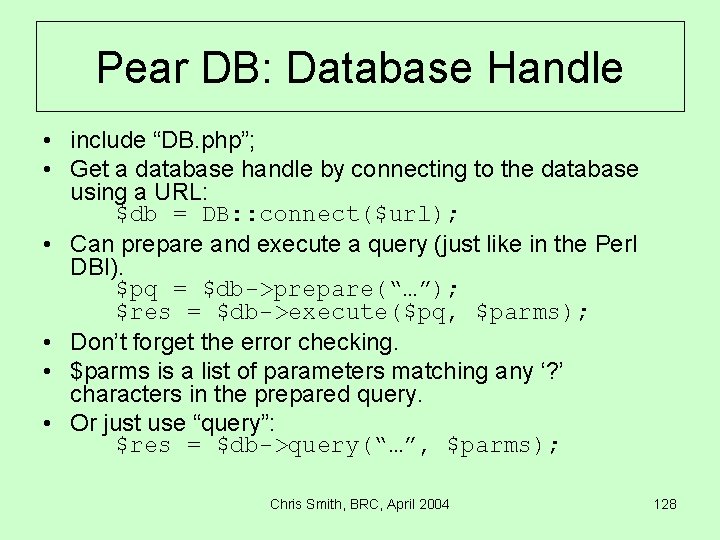

Pear DB: Database Handle • include “DB. php”; • Get a database handle by connecting to the database using a URL: $db = DB: : connect($url); • Can prepare and execute a query (just like in the Perl DBI). $pq = $db->prepare(“…”); $res = $db->execute($pq, $parms); • Don’t forget the error checking. • $parms is a list of parameters matching any ‘? ’ characters in the prepared query. • Or just use “query”: $res = $db->query(“…”, $parms); Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 128

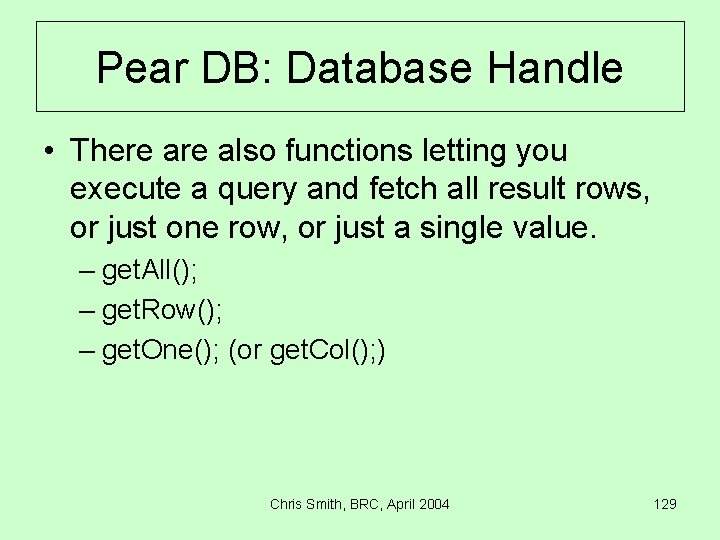

Pear DB: Database Handle • There also functions letting you execute a query and fetch all result rows, or just one row, or just a single value. – get. All(); – get. Row(); – get. One(); (or get. Col(); ) Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 129

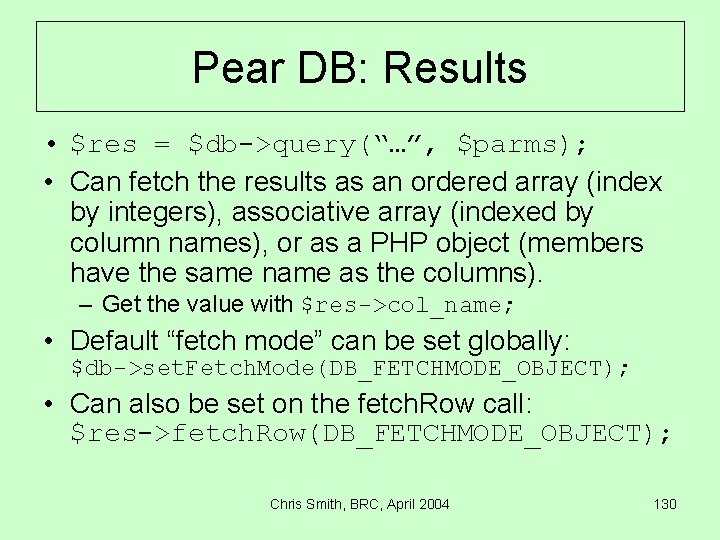

Pear DB: Results • $res = $db->query(“…”, $parms); • Can fetch the results as an ordered array (index by integers), associative array (indexed by column names), or as a PHP object (members have the same name as the columns). – Get the value with $res->col_name; • Default “fetch mode” can be set globally: $db->set. Fetch. Mode(DB_FETCHMODE_OBJECT); • Can also be set on the fetch. Row call: $res->fetch. Row(DB_FETCHMODE_OBJECT); Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 130

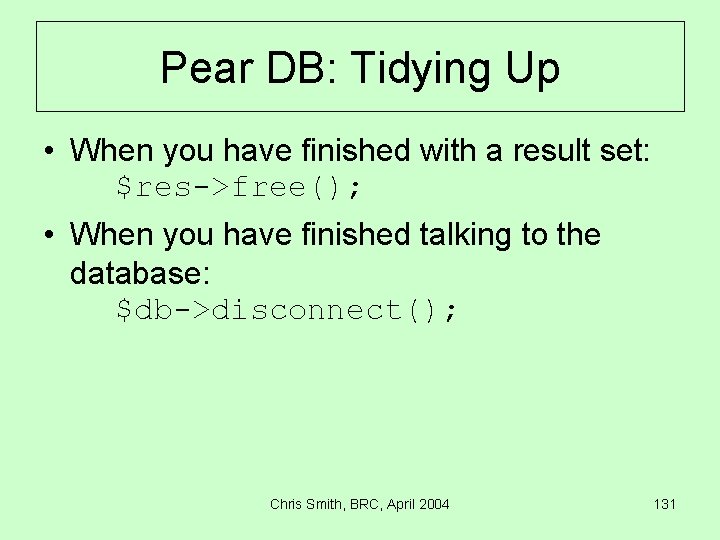

Pear DB: Tidying Up • When you have finished with a result set: $res->free(); • When you have finished talking to the database: $db->disconnect(); Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 131

Example Program • Example script – In the “microarray” subdirectory of the course downloads. • mysql_import. pl, mysql_import. php • pg_import. pl, pg_import. php • Import some microarray data downloaded from the Stanford Microarray Database. • Data files are in directories named after the experimenters and within “experiment set” subdirectories. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 132

Example Data • Each data file contains some header lines describing the experimental conditions. • The column names in these files vary from experimenter to experimenter. • The number and order of columns in the data files is not fixed. • The code attempts to find the columns in which we are interested. • There are 4 data files (from 4 microarrays) containing data for about 170, 000 spots. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 133

Example Code • The example code DROPs an existing table, and recreates it. • It expects a specific directory structure. • It then uses INSERT to add new entries to the newly created table. • With Postgre. SQL we use a transaction: – Without a transaction it runs veeerrrrrrryyyy slllllllooooowwwwwllllyyyy. • With My. SQL: – Even if we try starting a transaction it doesn’t use one. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 134

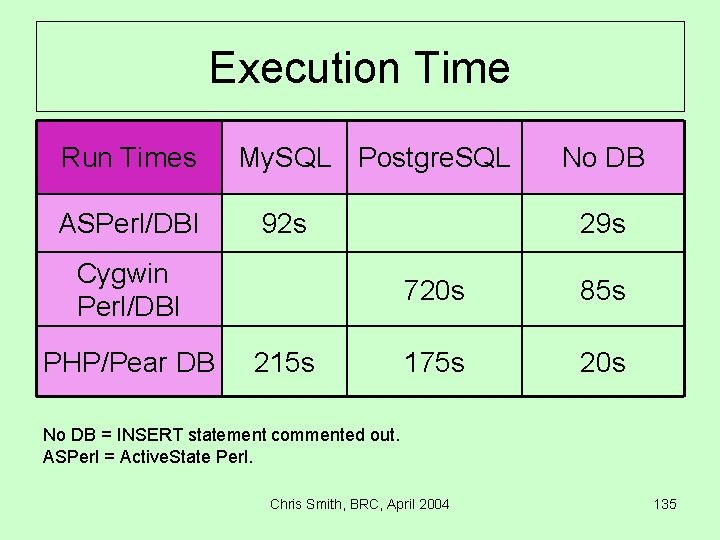

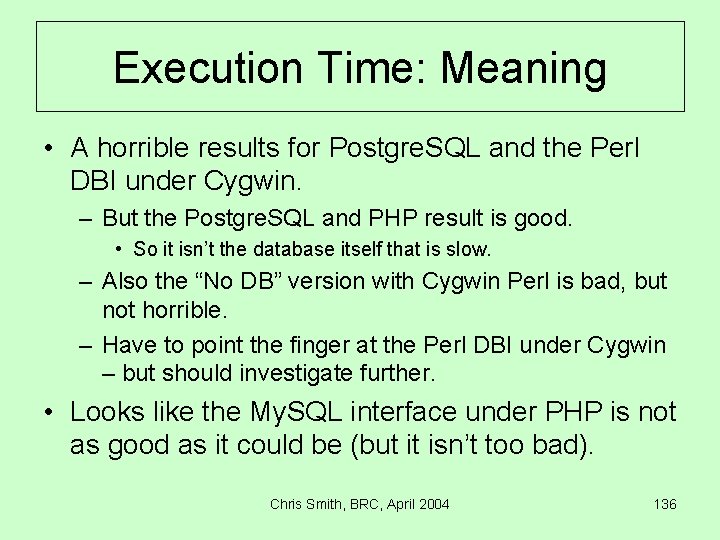

Execution Time Run Times ASPerl/DBI My. SQL Postgre. SQL 92 s Cygwin Perl/DBI PHP/Pear DB 215 s No DB 29 s 720 s 85 s 175 s 20 s No DB = INSERT statement commented out. ASPerl = Active. State Perl. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 135

Execution Time: Meaning • A horrible results for Postgre. SQL and the Perl DBI under Cygwin. – But the Postgre. SQL and PHP result is good. • So it isn’t the database itself that is slow. – Also the “No DB” version with Cygwin Perl is bad, but not horrible. – Have to point the finger at the Perl DBI under Cygwin – but should investigate further. • Looks like the My. SQL interface under PHP is not as good as it could be (but it isn’t too bad). Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 136

User Rights Assignment: GRANT • GRANT – Grantable privileges are: • SELECT, INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE, REFERENCES, USAGE • GRANT SELECT ON ath 1_gene TO PUBLIC; – Lets anyone read from the ath 1_gene table. • GRANT INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE ON ath 1_gene TO chris; – Lets a user called ‘chris’ make changes to the table. • GRANT ALL PRIVILEGES ON ath 1_gene TO chris; – Lets user chris do anything with table ath 1_gene. • GRANT …. . TO chris WITH GRANT OPTION; – Allows user chris to grant other users privileges on the table. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 137

User Rights Assignment: REVOKE • To remove a privilege from a user: – REVOKE INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE ON ath 1_gene FROM chris; Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 138

Managing Users in My. SQL • My. SQL extends the GRANT syntax considerably. • Uses the GRANT command to create users as well as manage privileges. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 139

Managing Users in Postgre. SQL • CREATE USER … • GRANT is standard SQL. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 140

Keeping Your Database Efficient • Both My. SQL and Postgre. SQL tables can tend to become fragmented over time (expecially if lots of updates are made). • Both databases provide mechanisms for tidying up. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 141

![Postgre. SQL VACUUM • VACUUM [FULL] [ANALYZE]; – VACUUM defragments the database. – FULL Postgre. SQL VACUUM • VACUUM [FULL] [ANALYZE]; – VACUUM defragments the database. – FULL](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/13e57dc6b68e01a008b9eea417a65e2c/image-142.jpg)

Postgre. SQL VACUUM • VACUUM [FULL] [ANALYZE]; – VACUUM defragments the database. – FULL returns space to the disk drive. – ANALYZE updates Postgre. SQL’s statistics (helping the query optimizer give good results). Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 142

My. SQL OPTIMIZE TABLE • OPTIMIZE TABLE table_name; – Can be used to optimize some types of table. – (I haven’t talked about the different types of My. SQL table!) Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 143

Relational Databases and SQL Session 4 Database Design Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004

Database Design 1. 2. 3. 4. Comments on last session. Entities and Relationships. Normalization. Examples. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 145

Loading Data 1 • Last time we saw a script that used the INSERT statement to load data into a microarray data table. • We also saw that the Postgre. SQL/Cygwin/Perl DBI combination was quite slow at this. • We could have parsed our microarray data files into plain tab-delimited text files and then used the Postgre. SQL COPY command, (or the My. SQL LOAD DATA command) as we did in the ath 1_gene example. • This would have been faster. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 146

Loading Data 2 • We saw the difference between My. SQL and Postgre. SQL when loading the microarray data. • Postgre. SQL was loading each array within a transaction. My. SQL was not. • One technique to prevent getting partial data into the table would be to first load the data to a temporary table. – Then when the temporary table holds the data for one array copy it to the permanent table using INSERT INTO table_name SELECT … syntax. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 147

Perl and PHP “Standards” • Last time someone asked whether Perl and PHP are standardized. • They aren’t – but there is only (currently) one source for each language. • So they are effectively standard. • They do tend to change considerably from version to version. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 148

Entities • An entity is anything for which we would like to store some data. – A customer in a store. – A customer order. – Microarray experiment. – An individual microarray. – A tree. –… Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 149

Relationships • Some entities are logically associated with other entities. – E. g. an individual microarray belongs to a specific microarray experiment. • We say that there is a relationship between the microarray entity and the microarray experiment entity. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 150

ER Diagrams • We document entities and relationships using an entity-relationship diagram. • There a number of different conventions used for drawing these diagrams: Chen, “Information Engineering”. • Doesn’t really matter which you use. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 151

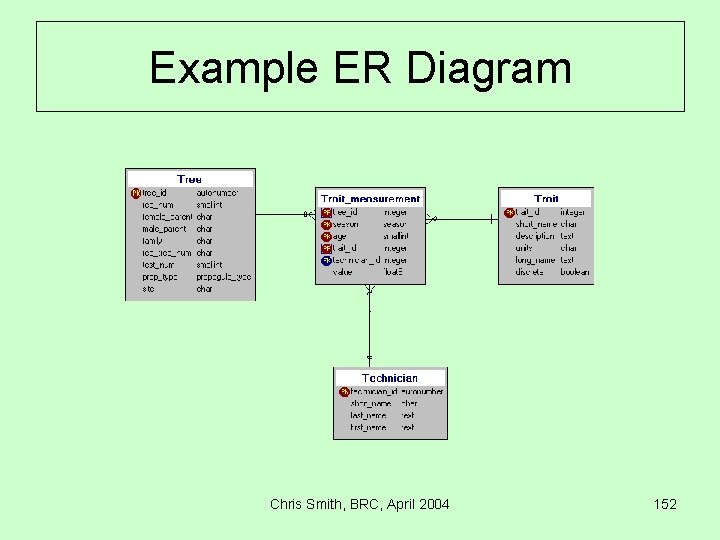

Example ER Diagram Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 152

ER Diagrams • When creating an ER diagram you are supposed to be documenting the entities and relationships in your domain of interest. • But the entities are (more-or-less) going to become tables in your database. – There isn’t a one-one mapping here. We’ll see examples later. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 153

ER Diagram Tools • Couldn’t find a decent free one. • De. Zign for Databases from Datanamic. – – Supports many different databases. Easy to use. Generates the SQL DDL code for your database. Not too expensive (but not really cheap). • Visio can do ER-diagrams. – But won’t generate code for you. • You can always use a piece of paper and write the code yourself! Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 154

Relationship Types • There are 3 basic types of relationship. – One-to-one. • People (in the US) and Social Security Numbers (trivial). • A store is managed by a single person. – One-to-many. • Trees planted on plots of land. Each plot of land can have many trees, but each tree is on just one plot. – Many-to-many. • Genes and microarrays. A gene can appear on many microarrays and each microarray contains many genes. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 155

One-to-Many Relationships • Very common. • We have already seen one: – ath 1_gene, ath 1_feat – Each gene has many features, each feature belongs to just one gene. – Represented in the database by including a gene id in the feature table. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 156

Many-to-Many Relationships • Can’t be represented directly between 2 tables. – Would need multiple gene entries per gene! • Or multiple feature ids in a gene record. • Solution is to use a third table to represent the relationship. – Third table contains rows with (essentially) two columns: the primary keys from each of the related tables. – The entries in this table are known as composite entities. • If you are using a design tool (such as De. Zign) it may do this for you. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 157

Relationship Data • Sometimes you will need to add extra attributes to the composite entity. – E. g. In a store you have items and orders for those items. There is a many-many relationship between orders and items. Where do you keep the number of items being ordered? • Add it to the composite entity create for the many relationship. • You might have modelled this as a “line item” anyway. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 158

Choosing Primary Keys • Once you have determined your entities you should look at which columns can be used as primary keys. – (In practice you won’t do this as a separate step, you’ll be doing it as you go along. ) • As a rule-of-thumb avoid primary keys that contain meaning. – Keys with embedded meaning have a tendency to change causing problems in your database. – Especially don’t use any value that is likely to change e. g. telephone number seems like it might be a good identifier but changes when someone moves. (On the other hand it may be a good identifier if you are the telephone company!) • If there is no obvious (non-meaningful) primary key you can add a column that contains an arbitrary (unique) identifier. – The database system you are using likely provides a feature that will do this for you. In Postgre. SQL it is the “serial” type, in My. SQL it is the “autonumber” type. • Primary keys can be constructed from multiple columns. – For some tables all columns may be in the primary key. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 159

Normalization • There a number of design rules in the text books. These are given the name “normal forms” – – – – First normal form (already mentioned). Second normal form. Third normal form. Boyce-Codd normal form. Fourth normal form. Fifth normal form. Domain-Key normal form. • A database doesn’t have to be in any of the normal forms in order to be useful. • The normal forms do help to avoid problems – usually to do with insertion and deletion. • Sometimes it is OK to break normal form for performance reasons. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 160

First Normal Form • One column – one value. – No “repeating groups” (attribute with multiple values for one instance of an entity). • Example is “child’s name” in a person table. – People often have more than one child. – Papers have more than one author. • Could use a comma-separated string of names in a single column. – Difficult to update, difficult to search. • Could add multiple columns to the table: child 1, child 2, child 3. – This is bad because it limits the maximum number of children allowed, it wastes space for people with no children, it makes queries difficult to write. • Right way is to use a separate “child” table (one-to-many relationship), – Or, in this case, put children into the “person” table with a “parent” foreign key. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 161

Second Normal Form • A relation is in second normal form if: It is in first normal form and all non-key attributes are functionally dependent on the entire primary key (and not on any subset of the primary key). • Key word is “entire”. • Also known as “full functional dependence”. • Like a mathematical function (one input value, one output value). • We are trying to eliminate attributes which only depend on part of the key. • Basically says “don’t repeat values in different rows”. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 162

Not Second Normal Form • Suppose I had decided to put all my Arabidopsis gene information in one table. • I could have had one row per feature and repeated the gene information for each feature. • Primary key would then have to include a gene id and a feature id. • Gene information only depends on the gene id (not on the feature id). So this table would not be in second normal form. • Repetition of information is one problem (gene details would be in multiple rows). • I could no longer add a gene with no features (since I would have a NULL as part of the primary key). • If I wanted to delete a feature (having found out that it was incorrect) I might end up deleting all the gene information too (if this was the gene’s only feature). • Right way to go is to split genes and features. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 163

Third Normal Form • A relation is in third normal form if: it is in second normal form and no non-primary-key attribute is transitively dependent on the primary key. • Transitive dependency is where: column B depends on column A, and column C depends on column B. A B C • E. g. In a realtor’s database we have a “property” table that includes some details of the owner. Property number Owner name Owner phone number • Problem is redundant information. Duplication of owner phone number (if the owner has multiple properties). • Solution is to split the property table into “property” and “owner” tables. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 164

Third Normal Form • In Third Normal Form: all non-key fields are dependent on the key, the whole key and nothing but the key. • Basically means “don’t mix different entities in one table”. • For most purposes 3 rd Normal Form is enough. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 165

Normalization and Tables • Each level of normalization involves splitting a table into multiple tables. • You can end up with a lot of tables! • You can always get back what you started with (using joins). • Use views to hide the complexity. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 166

Example: Microarray Database • Task: design a database to store microarray results for multiple experiments. • One experiment consists of multiple arrays. • Assume that we are using the same microarray for all experiments. • Assume it is a spotted microarray (two dyes per array two samples hybridized to each array). • Assume we have a list associating each spot on the array with a gene identifier. • The results data consists of 2 intensity readings per spot on the array (real results have a lot more information). Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 167

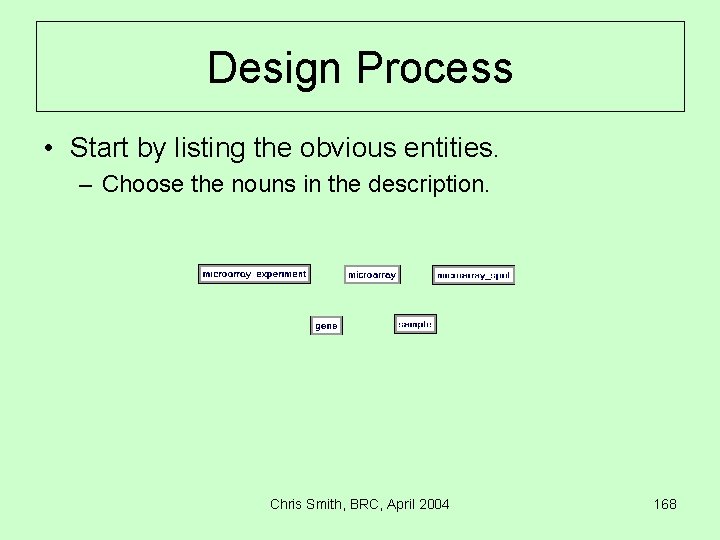

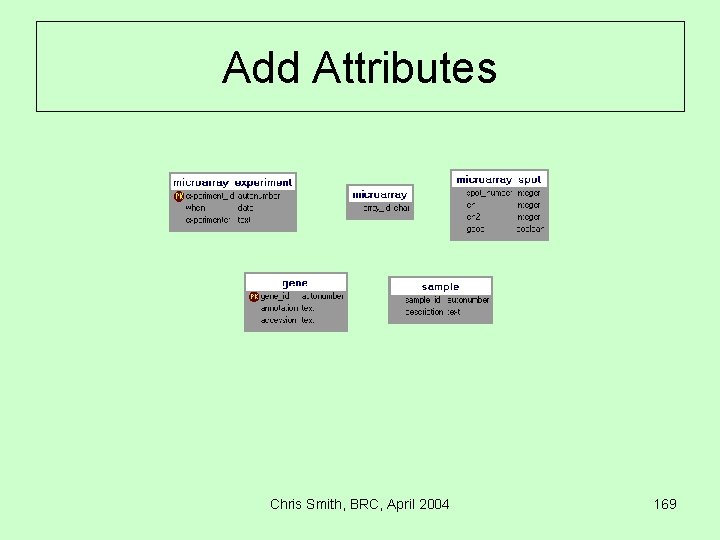

Design Process • Start by listing the obvious entities. – Choose the nouns in the description. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 168

Add Attributes Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 169

Add Relationships • • • Experiment -> microarray: 1 -N Microarray -> spot: 1 -N Microarray -> sample: N-2 Spot -> gene: N-1 In reality we have to choose more explicit limits on the relationships (0 -N, 1 -N). Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 170

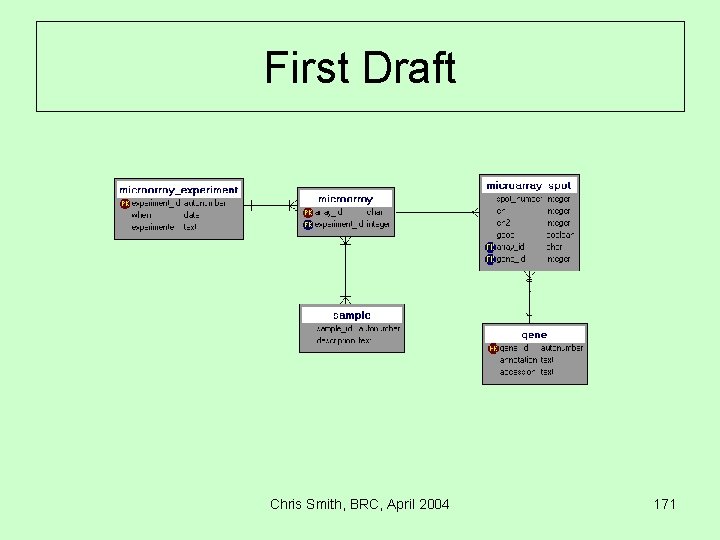

First Draft Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 171

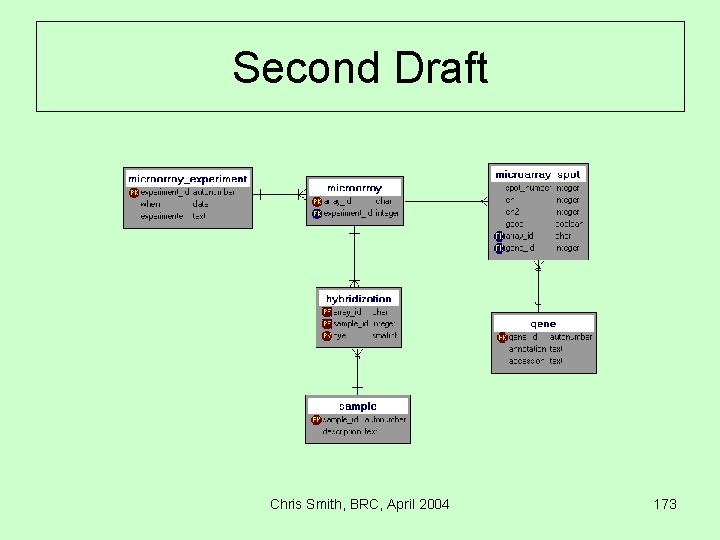

Small Problem • On generating the schema we get an extra table “microarray_sample” for the many-tomany relationship from microarrays to samples. • We notice that we don’t have anywhere that says which dye was used for which sample. – Could add this to the composite entity (need to make the relationship explicit as a table). Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 172

Second Draft Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 173

Possible Change • We might think that the sample-hybridizationmicroarray chain is getting a little complicated (we haven’t written any queries with it yet). • Could combine microarray and hybridization into a single table “microarray_hybridization”. • May depend on whether we have any other information to store in the microarray table e. g. type of slide used, procedure used, … Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 174

Oddities • There’s something funny going on with the spot table. • There’s no primary key yet. • We have channel 1 and channel 2 – but no way of matching channels to dyes. • Channel-dye mapping belongs in the hybridization table. • Also – is it OK to have columns ch 1 i and ch 2 i? – If we add a translation from dye to channel in the microarray table we would still be left writing awkward queries – we have to select the column name based on the channel. – On the downside – if we split each spot row into two we double the size of the table (and it’s big). And we violate second normal form. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 175

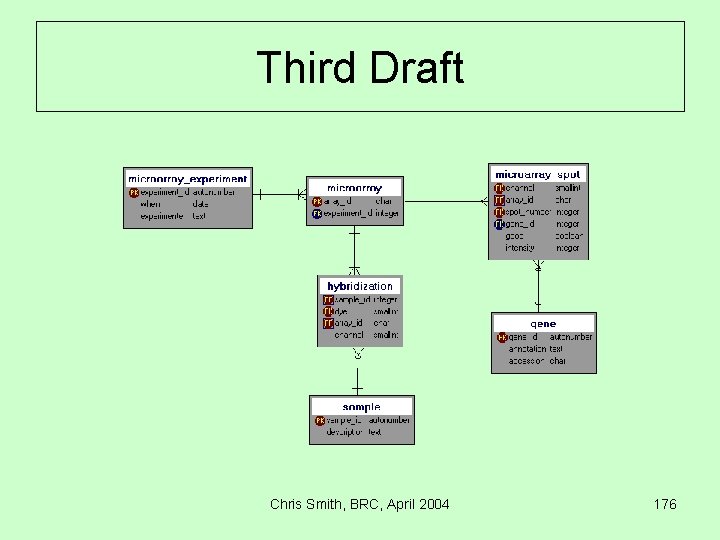

Third Draft Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 176

Other Possible Changes • Spot table is not in second normal form! • We assumed that we have a list mapping microarray spots to genes. • We could save space in the spot table by taking out the gene_id column and adding a spot number column to the gene table. • Would this work if we had assumed more than one type of microarray? Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 177

Domains • As mentioned in an earlier session you can have the database check that the values in your columns take a limited set of values. • Prime candidates for this are the dye and channel columns. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 178

Referential Integrity • When we add relationships to the ER diagram that are (strictly) 1 to N De. Zign adds a “constraint” to the table definition. • This makes the database check insertions for valid references to other entities. • E. g. when we insert a row into the microarray table the database will check that the experiment_id we give actually exists in the experiment table. – Means we have to add entries to the database in the correct order: experiments before microarrays. • You can add these constraints yourself by adding to the CREATE TABLE statement. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 179

Example Query 1 • Get all the result data for a specific experiment. • • SELECT r. * FROM microarray m, microarray_spot r WHERE m. experiment_id = ? AND r. array_id = m. array_id SELECT r. * FROM microarray m JOIN microarray_spot r USING (array_id) WHERE m. experiment_id = ? • Would need some interface for selecting the correct experiment id. – May be a web page that just lists all experiments. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 180

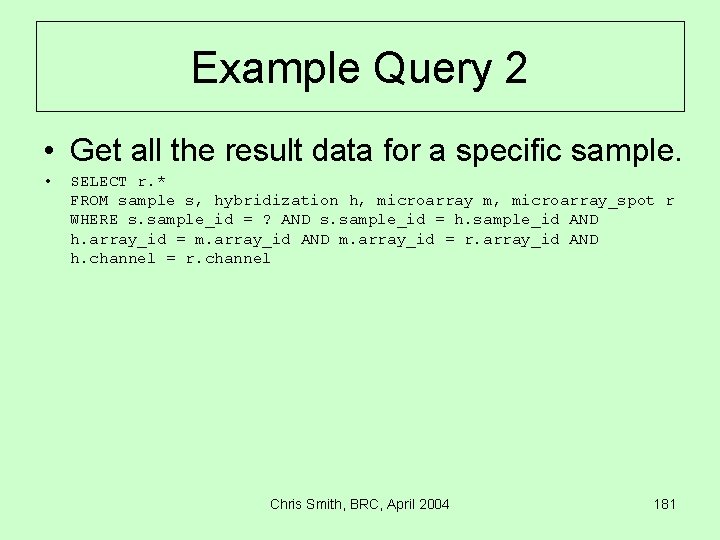

Example Query 2 • Get all the result data for a specific sample. • SELECT r. * FROM sample s, hybridization h, microarray m, microarray_spot r WHERE s. sample_id = ? AND s. sample_id = h. sample_id AND h. array_id = m. array_id AND m. array_id = r. array_id AND h. channel = r. channel Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 181

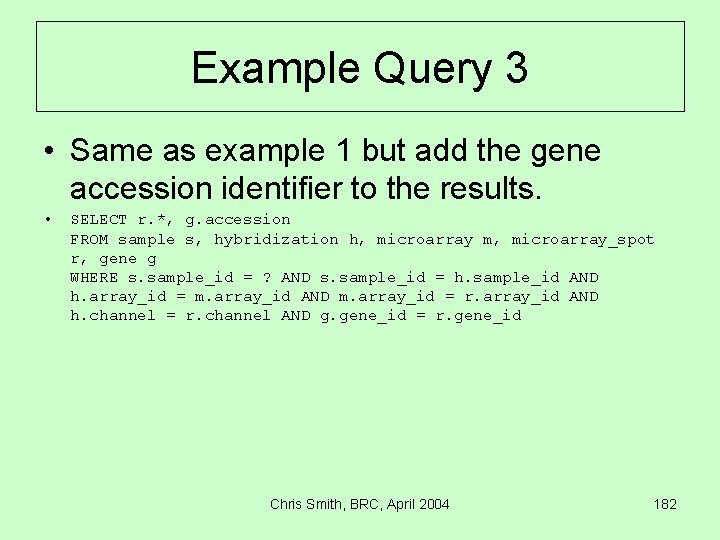

Example Query 3 • Same as example 1 but add the gene accession identifier to the results. • SELECT r. *, g. accession FROM sample s, hybridization h, microarray m, microarray_spot r, gene g WHERE s. sample_id = ? AND s. sample_id = h. sample_id AND h. array_id = m. array_id AND m. array_id = r. array_id AND h. channel = r. channel AND g. gene_id = r. gene_id Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 182

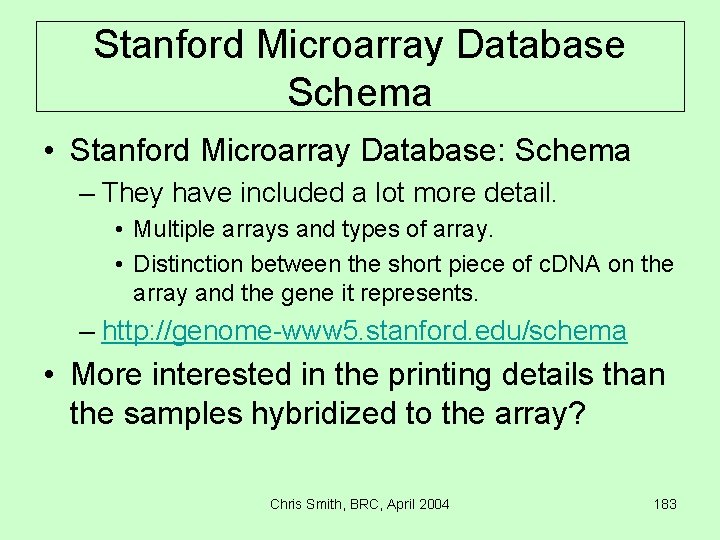

Stanford Microarray Database Schema • Stanford Microarray Database: Schema – They have included a lot more detail. • Multiple arrays and types of array. • Distinction between the short piece of c. DNA on the array and the gene it represents. – http: //genome-www 5. stanford. edu/schema • More interested in the printing details than the samples hybridized to the array? Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 183

General Advice 1 • Create a simple design and try it out. – Change things you don’t like. – If it is your own personal database the cost of changing it may be small (depending on how much code depends on its structure). – If lots of users have a copy the cost may be high (getting them all safely updated). • The rules are more like guidelines really. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 184

Exercises • The microarray data import scripts from session 3 are wrong in that they don’t include any array identifiers in the data table. There is also no primary key in the table. – Add the array identifier and choose a primary key (change the create table statement to include the key). • These scripts paid no attention to columns in the input data that indicated whether the spot is “good” or not. – These columns are: • “FAILED” indicating that PCR failed. (0=OK). • “IS_CONTAMINATED” indicates that the sample was contaminated (Y/N/U=Yes/No/Unknown? ) • “FLAG” indicates whether the spot was good or not. – Add code to take account of these columns to the scripts. Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 185

Harder Exercise • Update (one of) the scripts to use the microarray data schema designed in this session. • Design your own database! Chris Smith, BRC, April 2004 186

- Slides: 186