Regulation of gene expression Gene expression is controlled

- Slides: 42

Regulation of gene expression Gene expression is controlled at four levels: A. At transcription level. B. At post transcription level. C. At epigenetic level. D. Gene rearrangement.

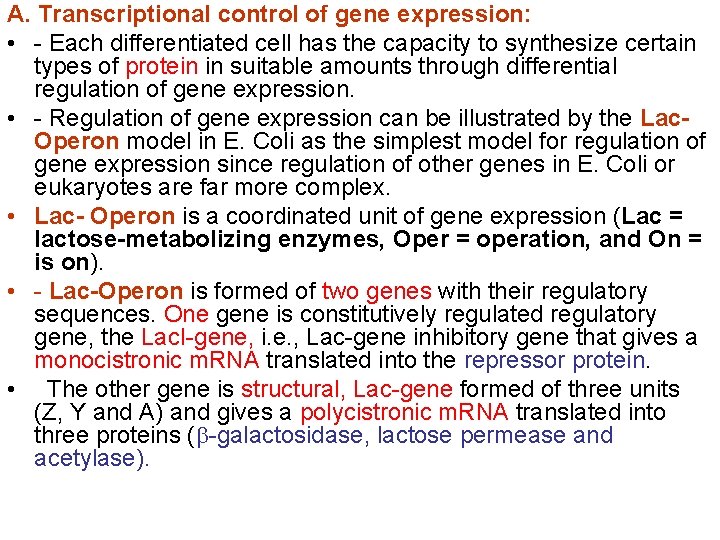

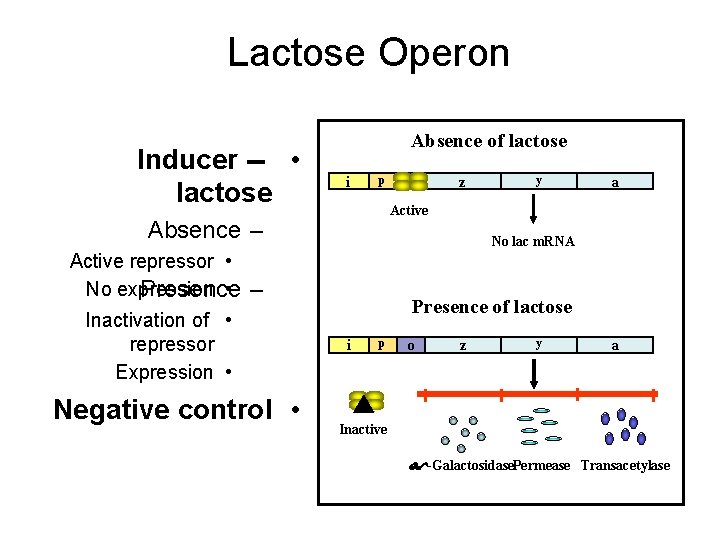

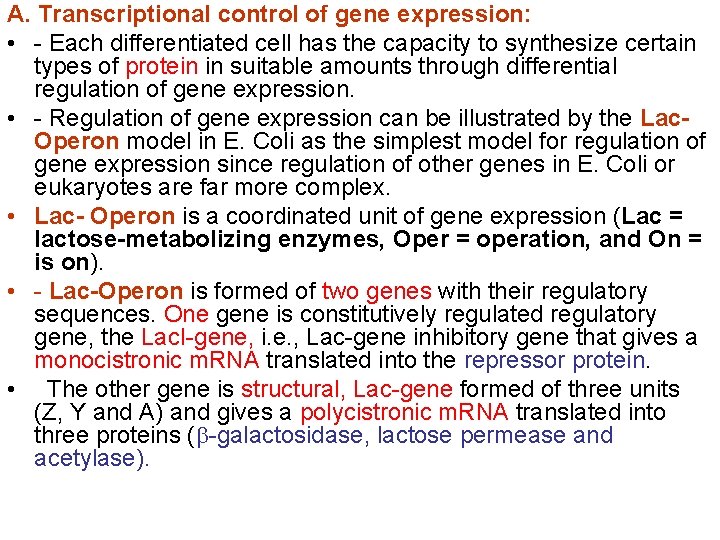

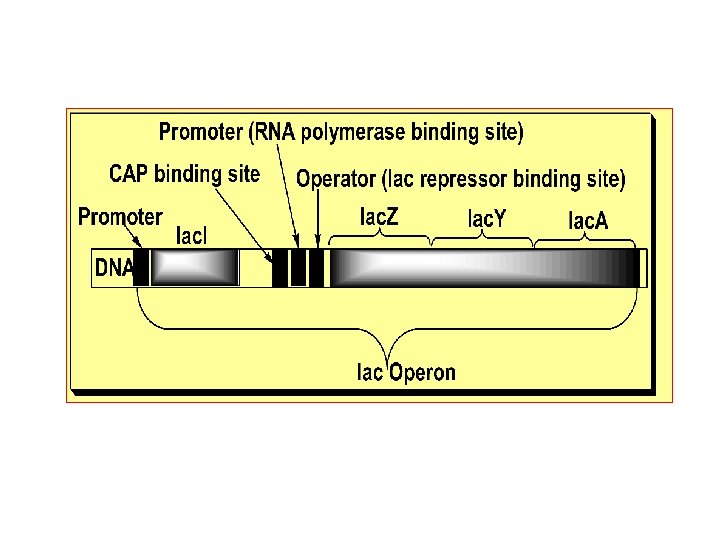

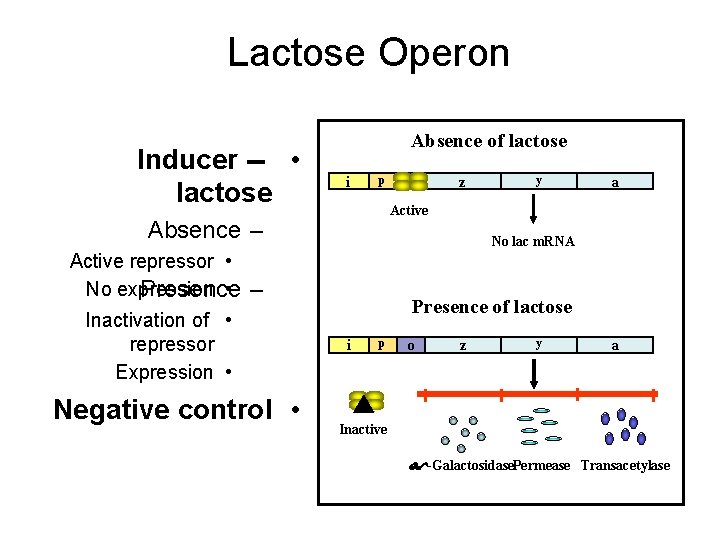

A. Transcriptional control of gene expression: • - Each differentiated cell has the capacity to synthesize certain types of protein in suitable amounts through differential regulation of gene expression. • - Regulation of gene expression can be illustrated by the Lac. Operon model in E. Coli as the simplest model for regulation of gene expression since regulation of other genes in E. Coli or eukaryotes are far more complex. • Lac- Operon is a coordinated unit of gene expression (Lac = lactose-metabolizing enzymes, Oper = operation, and On = is on). • - Lac-Operon is formed of two genes with their regulatory sequences. One gene is constitutively regulated regulatory gene, the Lac. I-gene, i. e. , Lac-gene inhibitory gene that gives a monocistronic m. RNA translated into the repressor protein. • The other gene is structural, Lac-gene formed of three units (Z, Y and A) and gives a polycistronic m. RNA translated into three proteins ( -galactosidase, lactose permease and acetylase).

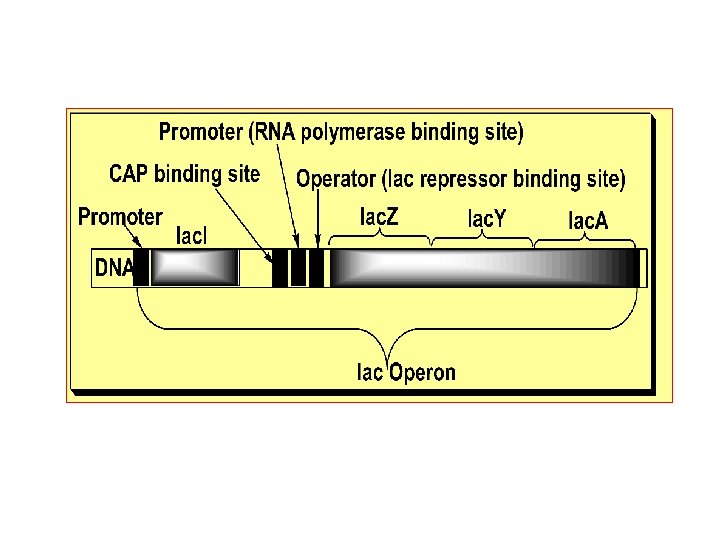

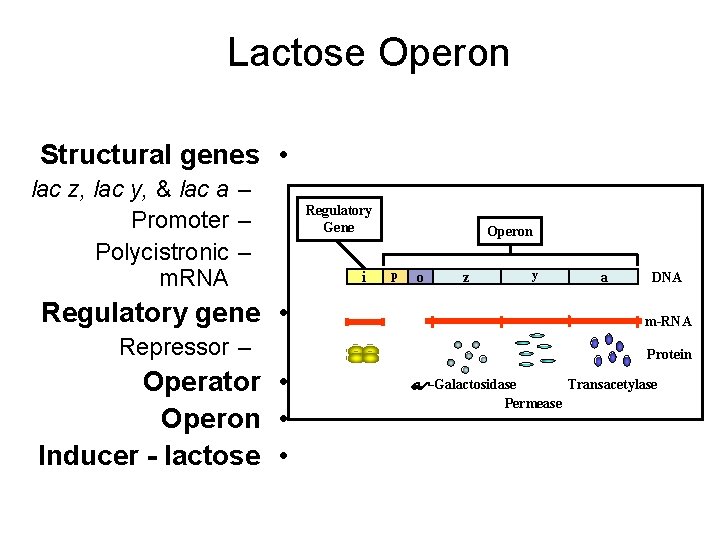

Lactose Operon Structural genes • lac z, lac y, & lac a – Promoter – Polycistronic – m. RNA Regulatory gene • Repressor – Operator • Operon • Inducer - lactose • Regulatory Gene i Operon p o z y a DNA m-RNA Protein -Galactosidase Transacetylase Permease

Lactose Operon Inducer -- • lactose Absence of lactose i p Negative control • y a No lac m. RNA – Inactivation of • repressor Expression • z Active Absence – Active repressor • No expression • Presence of lactose i p o z y a Inactive -Galactosidase. Permease Transacetylase

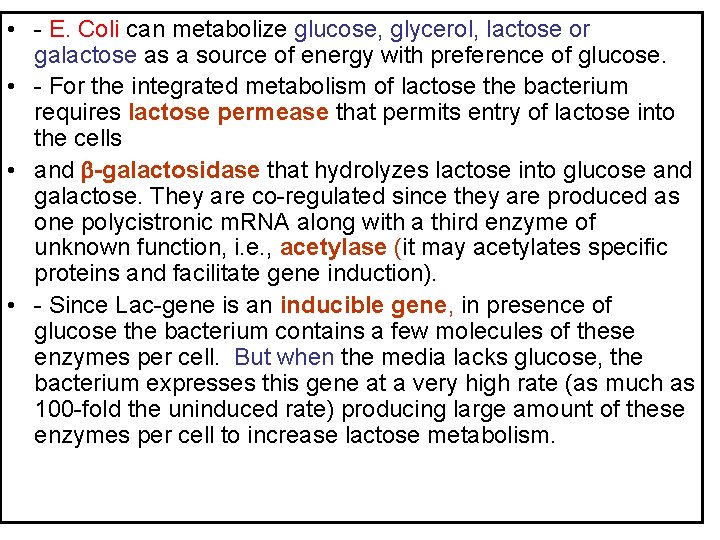

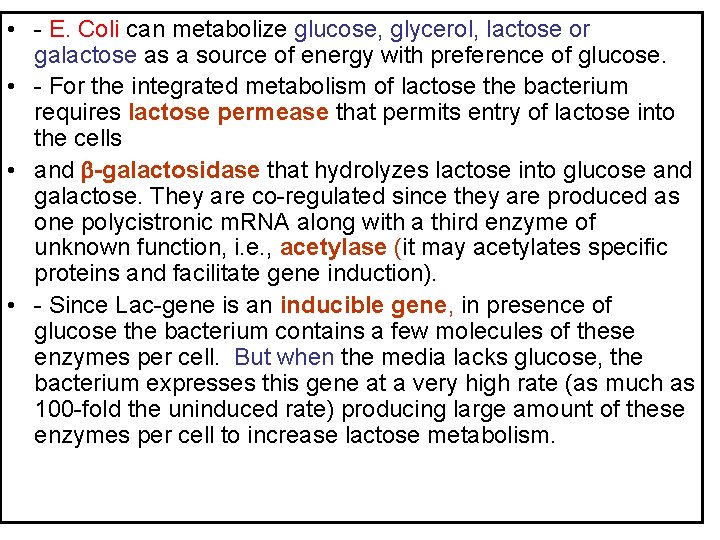

• - E. Coli can metabolize glucose, glycerol, lactose or galactose as a source of energy with preference of glucose. • - For the integrated metabolism of lactose the bacterium requires lactose permease that permits entry of lactose into the cells • and -galactosidase that hydrolyzes lactose into glucose and galactose. They are co-regulated since they are produced as one polycistronic m. RNA along with a third enzyme of unknown function, i. e. , acetylase (it may acetylates specific proteins and facilitate gene induction). • - Since Lac-gene is an inducible gene, in presence of glucose the bacterium contains a few molecules of these enzymes per cell. But when the media lacks glucose, the bacterium expresses this gene at a very high rate (as much as 100 -fold the uninduced rate) producing large amount of these enzymes per cell to increase lactose metabolism.

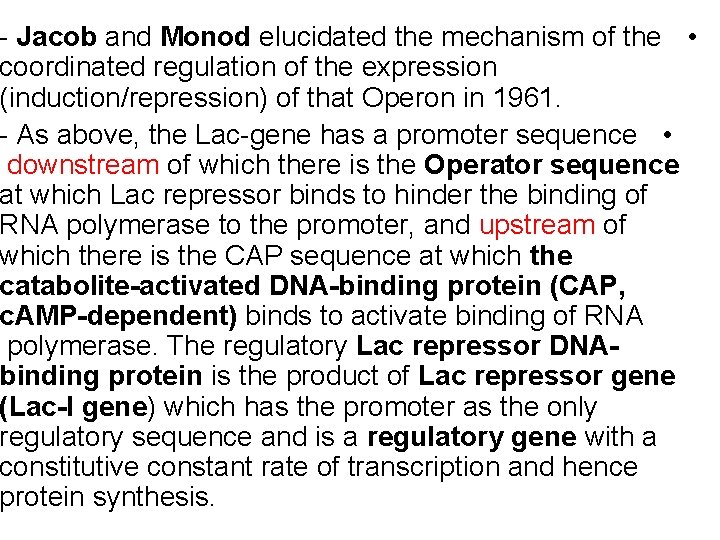

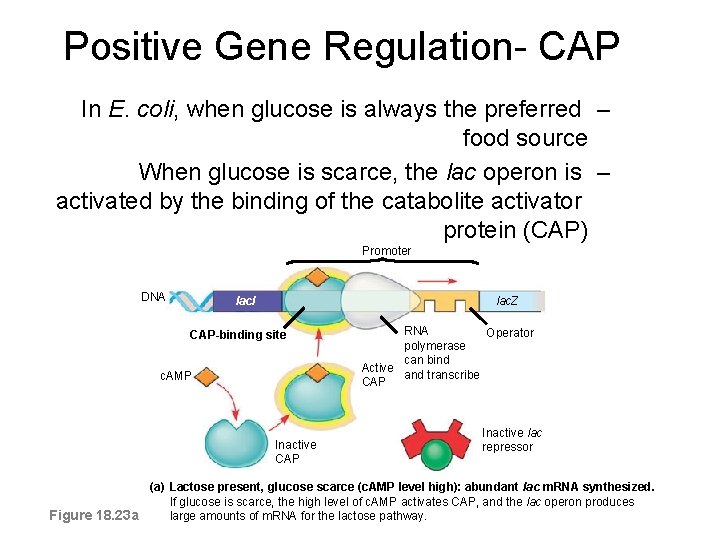

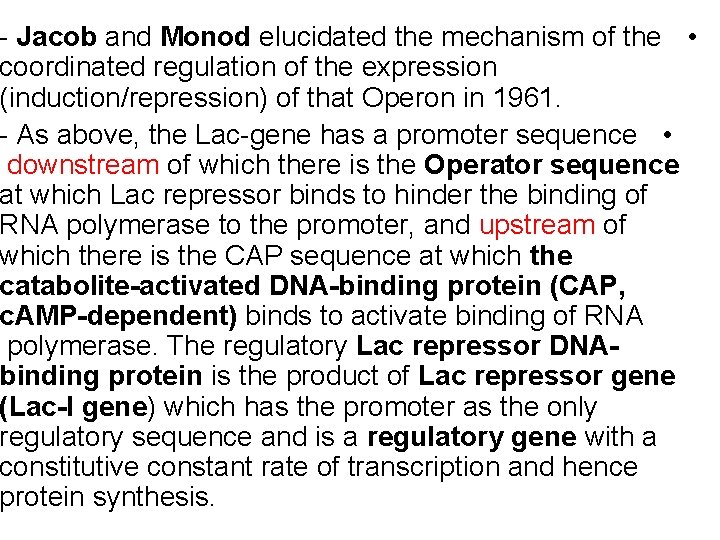

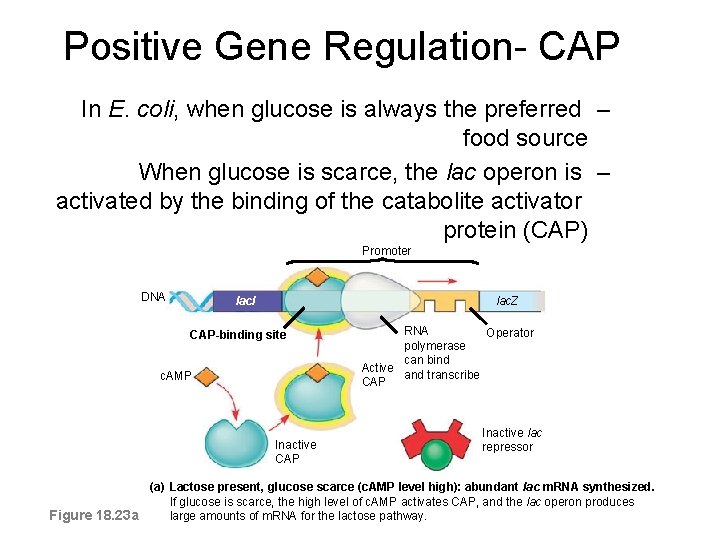

- Jacob and Monod elucidated the mechanism of the • coordinated regulation of the expression (induction/repression) of that Operon in 1961. - As above, the Lac-gene has a promoter sequence • downstream of which there is the Operator sequence at which Lac repressor binds to hinder the binding of RNA polymerase to the promoter, and upstream of which there is the CAP sequence at which the catabolite-activated DNA-binding protein (CAP, c. AMP-dependent) binds to activate binding of RNA polymerase. The regulatory Lac repressor DNAbinding protein is the product of Lac repressor gene (Lac-I gene) which has the promoter as the only regulatory sequence and is a regulatory gene with a constitutive constant rate of transcription and hence protein synthesis.

Operons An operon is a group • of genes that are transcribed at the same time. They usually control • an important biochemical process. They are only found • in prokaryotes. © 2007 Paul Billiet ODWS Jacob, Monod & Lwoff © Nobel. Prize. org

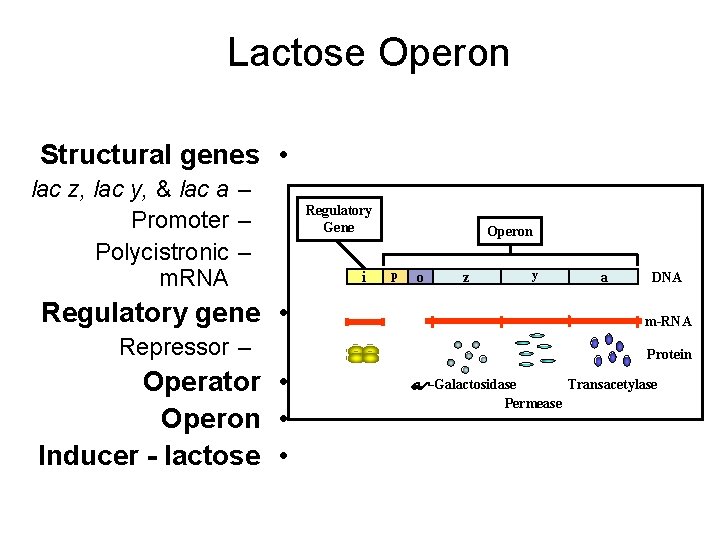

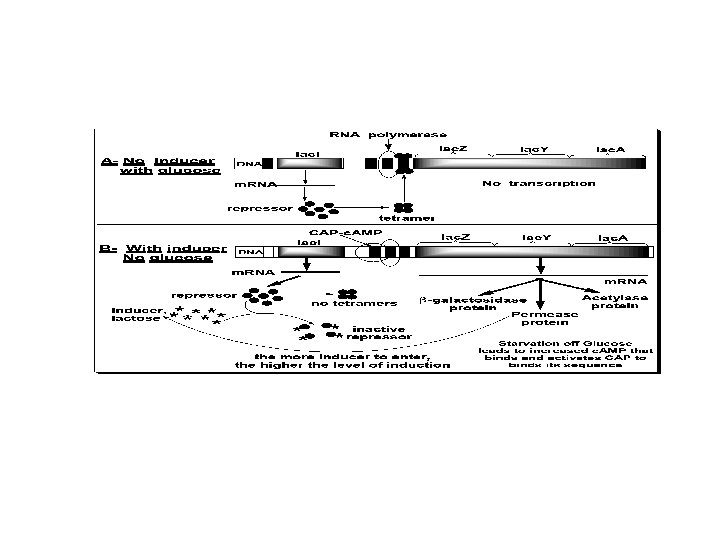

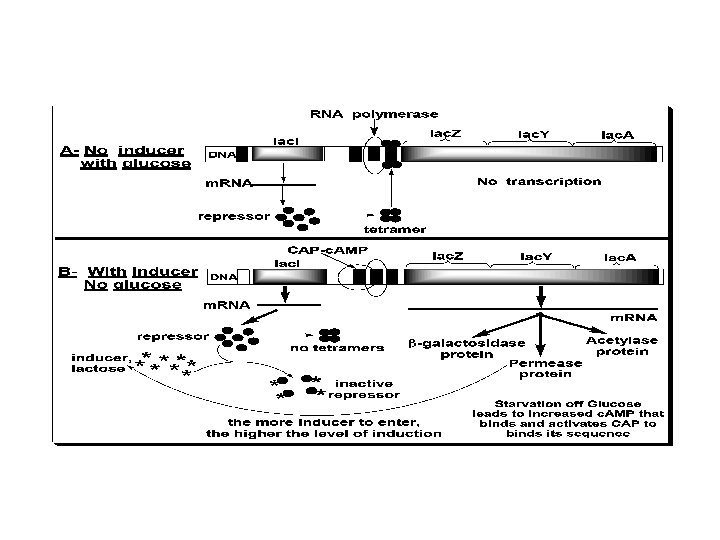

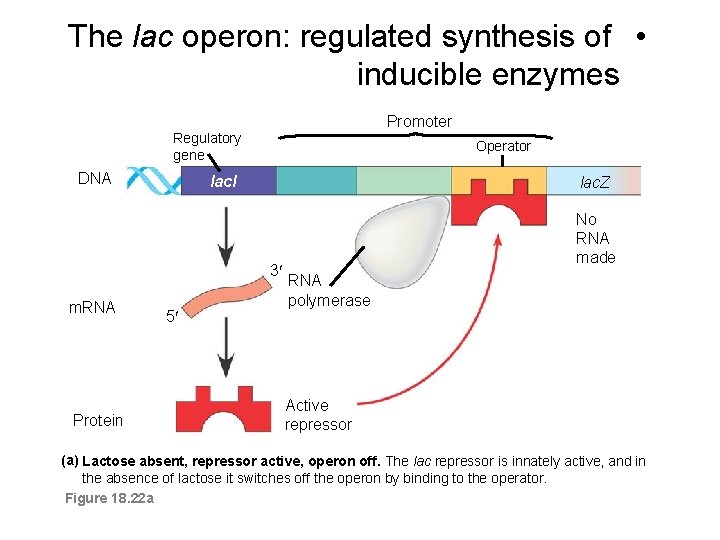

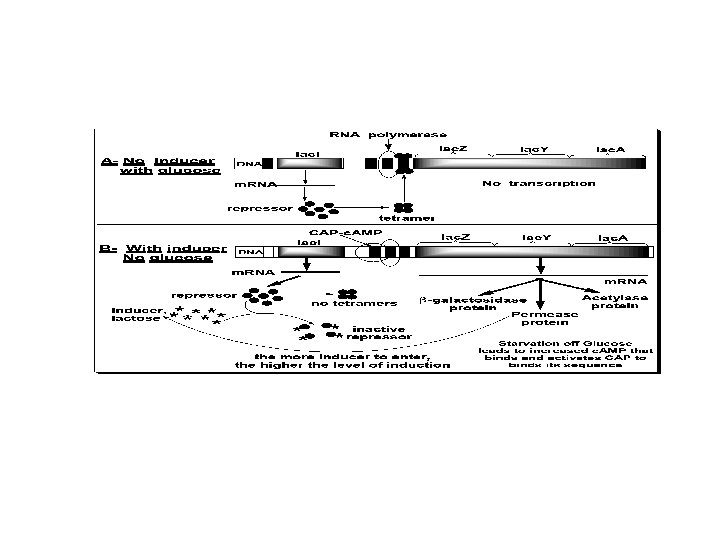

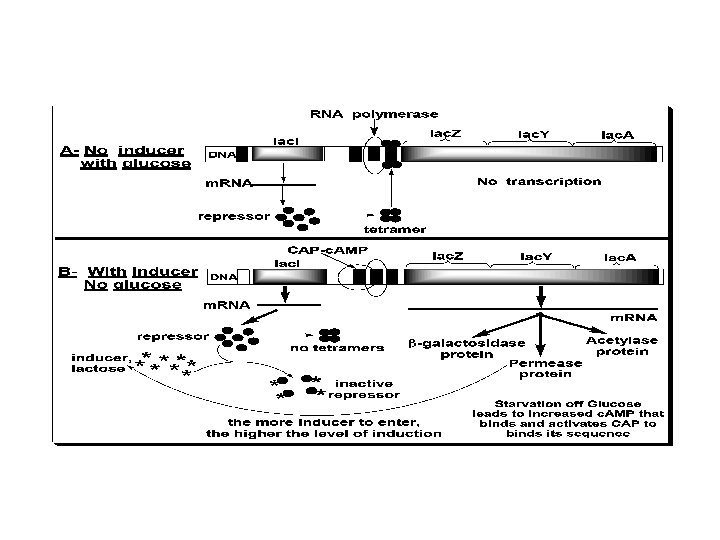

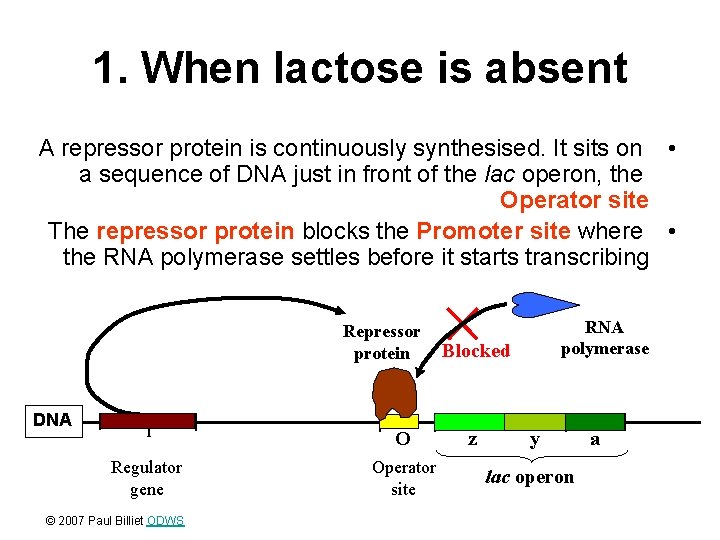

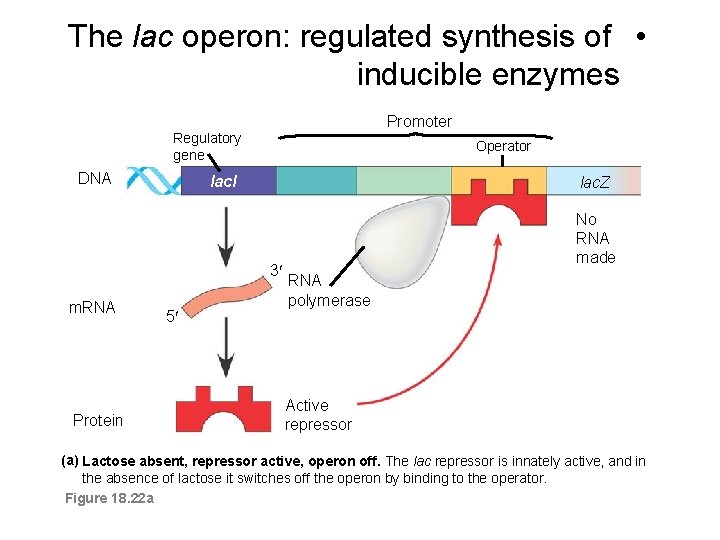

The two states of Lac-Operon (Repression and induction): 1. Repression: • - When E. Coli is grown in presence of glucose, transcription of the Lac-gene is repressed. Repression is mediated by Lac repressor, which binds as a tetramer to the operator sequence preventing the binding of RNA polymerase to the promoter and prevents the transcription of the Lac-gene. The repressor is a negative regulator, and its sequence is a silencer on expression of the Operon, see the following figure.

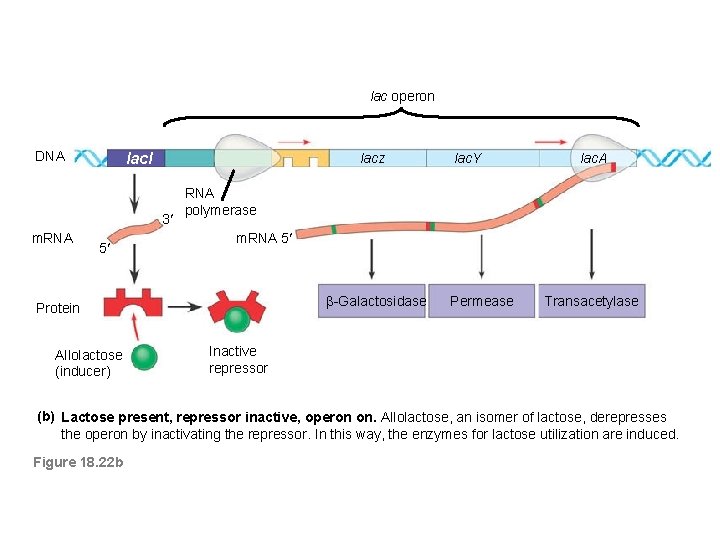

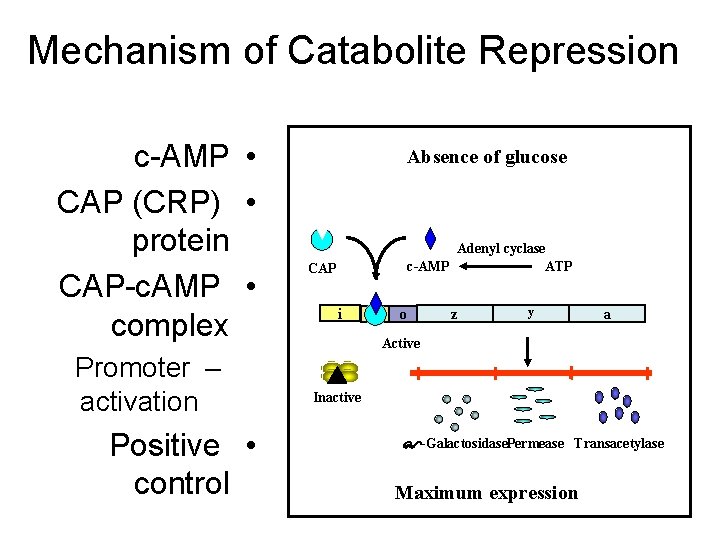

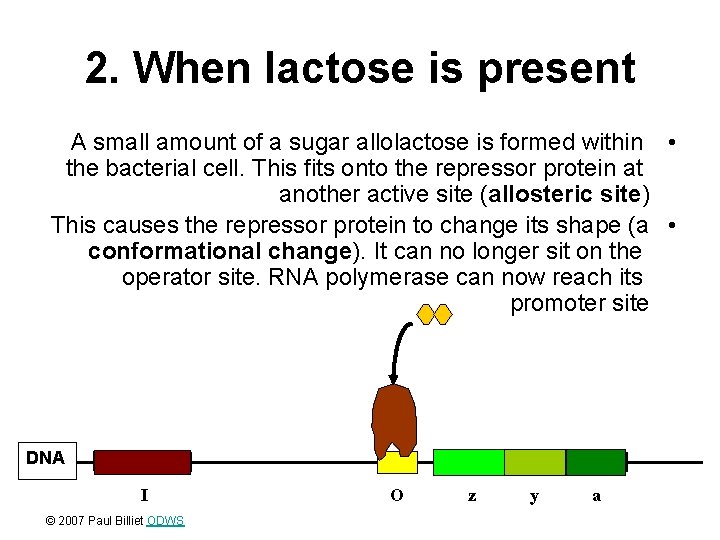

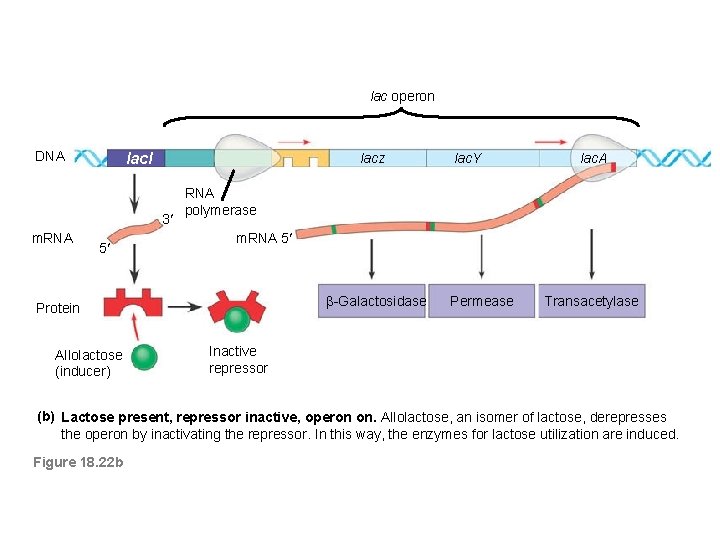

2. Induction (or derepression): • - When glucose is absent, the Lac-gene is induced, i. e. , expression rate of the Operon is increased. Starvation of the bacterium of glucose leads to increase of c. AMP that binds and activates the DNA binding of the Catabolite gene Activator Protein (CAP). The CAP binds to the CAP binding sequence of DNA up-stream the promoter to facilitate binding of RNA polymerase to the promoter to induce transcription of the Lacgene at a low level. Therefore, c. AMP-activated CAP is a positive regulator, and its sequence is an enhancer. • - The produced small amount of permease facilitates entrance of lactose into the cell. Lactose (an inducer) or its nonmetabolizible analogs (e. g. , isopropylthiogalacoside, a gratuitous inducer) have high affinity to bind the repressor causing a change in its conformation. This change prevents the repressor from binding to the operator. Therefore, lactose acts as an inducer and the operator becomes free for higher rate of transcription by RNA polymerase.

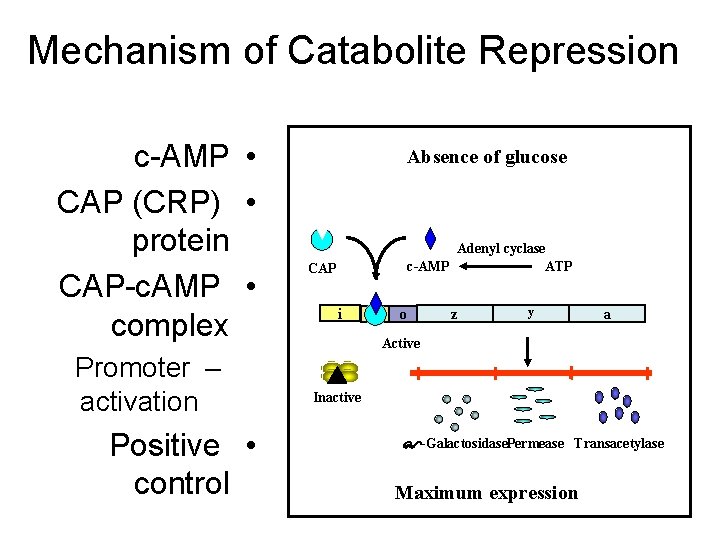

Mechanism of Catabolite Repression c-AMP • CAP (CRP) • protein CAP-c. AMP • complex Promoter – activation Positive • control Absence of glucose Adenyl cyclase c-AMP ATP CAP i p o z y a Active Inactive -Galactosidase. Permease Transacetylase Maximum expression

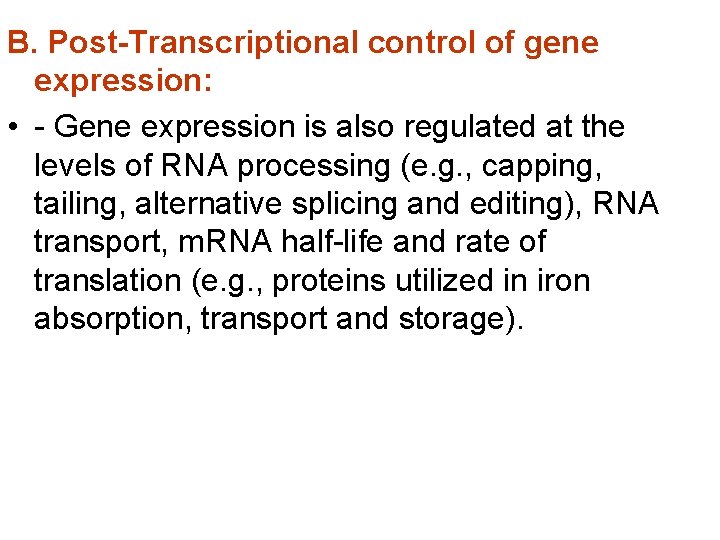

B. Post-Transcriptional control of gene expression: • - Gene expression is also regulated at the levels of RNA processing (e. g. , capping, tailing, alternative splicing and editing), RNA transport, m. RNA half-life and rate of translation (e. g. , proteins utilized in iron absorption, transport and storage).

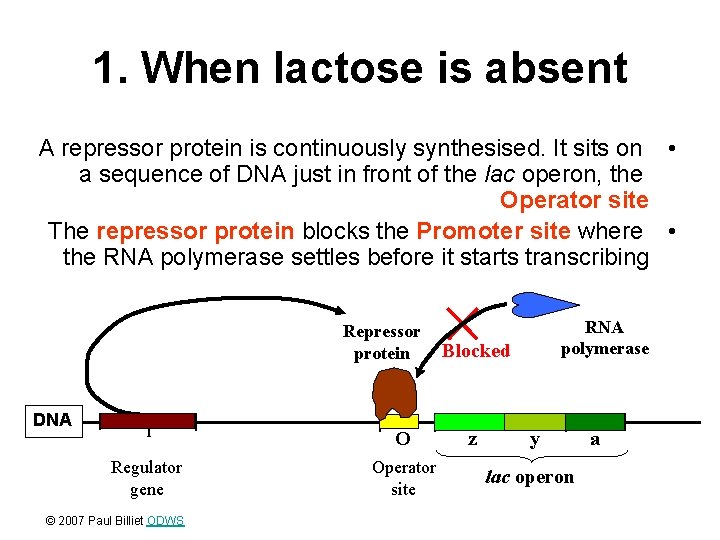

1. When lactose is absent A repressor protein is continuously synthesised. It sits on • a sequence of DNA just in front of the lac operon, the Operator site The repressor protein blocks the Promoter site where • the RNA polymerase settles before it starts transcribing Repressor protein DNA I O Regulator gene Operator site © 2007 Paul Billiet ODWS RNA polymerase Blocked z y lac operon a

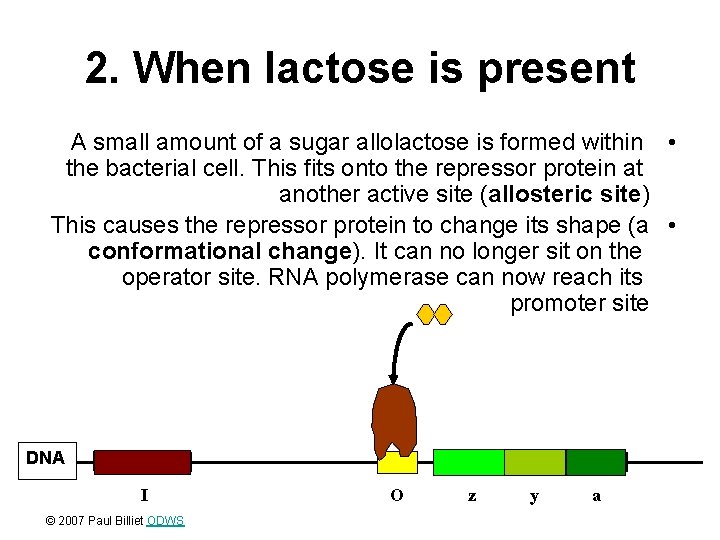

2. When lactose is present A small amount of a sugar allolactose is formed within • the bacterial cell. This fits onto the repressor protein at another active site (allosteric site) This causes the repressor protein to change its shape (a • conformational change). It can no longer sit on the operator site. RNA polymerase can now reach its promoter site DNA I © 2007 Paul Billiet ODWS O z y a

The lac operon: regulated synthesis of • inducible enzymes Promoter Regulatory gene DNA Operator lacl lac. Z 3 m. RNA Protein 5 No RNA made RNA polymerase Active repressor (a) Lactose absent, repressor active, operon off. The lac repressor is innately active, and in the absence of lactose it switches off the operon by binding to the operator. Figure 18. 22 a

lac operon DNA lacl lacz 3 m. RNA 5 lac. A RNA polymerase m. RNA 5' 5 m. RNA -Galactosidase Protein Allolactose (inducer) lac. Y Permease Transacetylase Inactive repressor (b) Lactose present, repressor inactive, operon on. Allolactose, an isomer of lactose, derepresses the operon by inactivating the repressor. In this way, the enzymes for lactose utilization are induced. Figure 18. 22 b

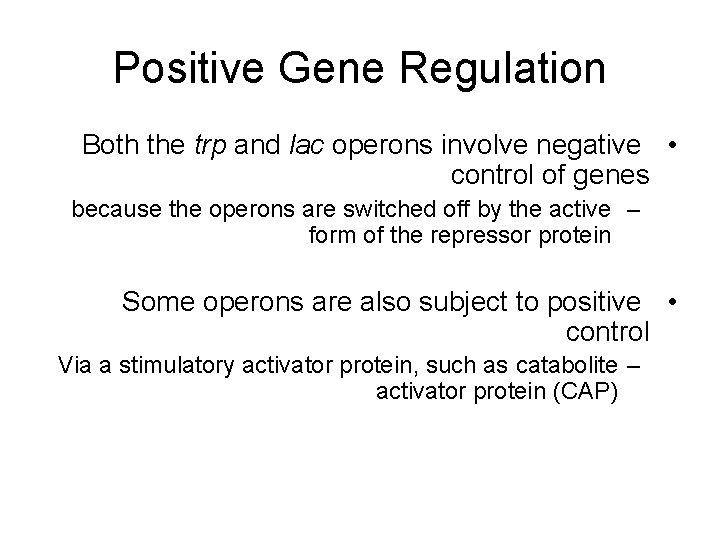

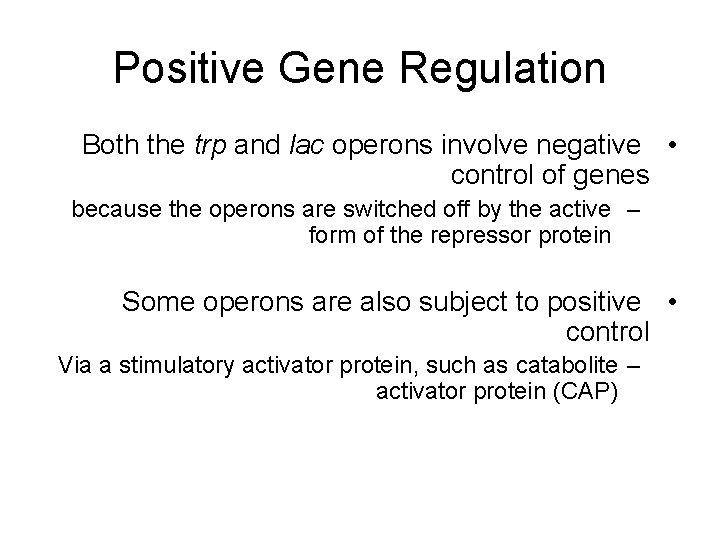

Positive Gene Regulation Both the trp and lac operons involve negative • control of genes because the operons are switched off by the active – form of the repressor protein Some operons are also subject to positive • control Via a stimulatory activator protein, such as catabolite – activator protein (CAP)

Positive Gene Regulation- CAP In E. coli, when glucose is always the preferred – food source When glucose is scarce, the lac operon is – activated by the binding of the catabolite activator protein (CAP) Promoter DNA lacl lac. Z CAP-binding site c. AMP Inactive CAP RNA Operator polymerase can bind Active and transcribe CAP Inactive lac repressor (a) Lactose present, glucose scarce (c. AMP level high): abundant lac m. RNA synthesized. If glucose is scarce, the high level of c. AMP activates CAP, and the lac operon produces Figure 18. 23 a large amounts of m. RNA for the lactose pathway.

C. Epigenetic control of gene expression: • - Gene expression is also regulated by epigenetic factors such as the spatial cell-cell and cell-matrix contact through mechanisms that include methylation at cytosine of specific Cp. G islands near the promoter region of genes (hyper- and hypo-methylation) and chromatin remodeling. Environmental agents, e. g. , alkylating pollutants may work by modulation of such methylation and remodeling. An example is the inactivation of most of the gene contained in the inactive female X chromosome as a form of genomic imprinting.

D. Gene rearrangement: - It is due to one of the following events: – Cross-over is a recombination between homologous chromosomes during meiosis with equal or unequal reciprocal exchange of genetic material. The later results in diseases due deletion/insertion mutation. – Sister chromatid exchange. – Differential rearrangement, i. e. , for the VL and CL genes for a single immunoglobulin molecule that are widely separated in the germ line DNA and upon maturation of plasma cell they move and become closer together.

– Transposition, transposons are small DNA elements that are capable of transposing themselves in and out of the host genome and may affect the function of the neighboring sequences. This occurs through an RNA intermediate utilizing reverse transcriptase. – Gene conversion by exchange of DNA sequences between homologous or nonhomologous chromosomes after being duplicated and become similar in these chromosomes. – Integration of oncogenic viruses. – Gene amplification, due to repeated initiation during DNA replication that increases the gene copy number and dosage, e. g. , genes for eggshell formation during oogenesis are amplified and also in cancer cells (See cancer biology).

DNA alteration (Mutations) Definition: - Mutation is the change of base sequence of nucleotides in the genetic code due to replacement, deletion (removal) or insertion (addition) of one or more bases resulting in altered gene product and/or regulation, or a change in gene copy number, or a structural or numerical abnormality in chromosomes. Causes: • Physical (most common) such as: UV, X and radiations. • Chemical carcinogens such as anticancer base analogs and alkylating agents. • Environmental pollutants-derived oxidative free radical such as nitrous acid. • Genomic instability, errors of DNA replication and defective repair.

Types of DNA mutation or alteration: a) Single base alteration (point mutation): • Deamination, e. g. , adenine into hypoxanthine and cytosine into uracil. • Depurination or depyrimidination, i. e. , removal of a purine or a pyrimidine base. • Alkylation of a base (mostly guanine) by covalent addition of an alkyl radical. • Insertion or deletion of a nucleotide. • Base-analog incorporation.

b) Two bases alteration: • UV-induced thymine–thymine dimer. • Cross linkage caused by bifunctional alkylating agent. • c) Strand breakage: Single-strand breaks are less • harmful than double- strand breaks in the phosphodiester backbone. It is caused by: Ionizing radiation. • Radioactive disintegration of incorporated element. • Oxidative free radical formation. • d) Cross-linkage: • Two bases in same strand or opposite strands. • DNA cross-linkage to histones or other proteins •

Point mutations • Definition and types: - It is a single base change that can be Transition mutation: a purine base is changed to another purine base, e. g. , adenine into guanine or a pyrimidine base to another pyrimidine base, e. g. , thymine into cytosine. Or, transversion mutation: a purine base is changed into a pyrimidine base and vice versa. And/or insertion or deletion of one or two bases that cause frame shift mutation.

Fate (or effect) of point mutation: • • Silent mutation, i. e. , the changed base leads to a codon, which produces the same amino acid. In this case, the change lies in the third base of the codon, which has several alternative names for same amino acid. Missense mutation, i. e. , the change occurred either in first or second base of the codon producing a different amino acid. The effect of missense mutation on the protein produced is dependent on the position and nature of the replacement amino acid. This protein could be normally functioning, partially functioning, non-functioning or not produced at all because of defective RNA processing. Example is Sickle cell anemia or hemoglobin S with normal two chains and abnormal two chains leading to rapid hemolysis due to mutant glutamate at position 6 into valine.

• • • Non-sense mutation, i. e. , the altered base results in a non-sense termination codon. This leads to pre -mature stopping of protein synthesis leading to truncated protein e. g. , c-erb. B 2 oncogene or no protein is produced at all. Frame shift mutation, i. e. , shift in the trinucleotide reading frame e. g. , in the BAX gene in ovarian cancer resulting in: Truncated protein if a non-sense codon is developed due to the shift. Garbled translation into totally different protein after the shift point. A protein may not be produced at all because m. RNA is degraded. - Insertion or deletion of three bases produces a protein with an extra or lacking an amino acid. It has a moderate effect on the produced protein.

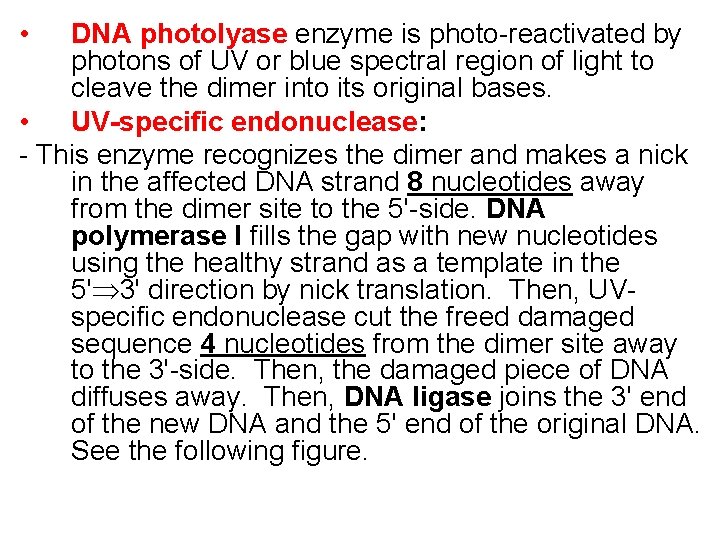

Mechanisms of repair of DNA Damage 1. Excision repair: - Used to correct many types of DNA damage that affects only one strand. It has three mechanisms as follows, A. Nucleotide excision repair of thymine-thymine (or pyrimidine) dimer: • - Thymine-thymine dimer is covalent linkage of two adjacent thymine bases in a single strand occurs spontaneously, or due to chemical, radiation, or ultraviolet (UV) light damage to DNA segment. • - These dimers prevent DNA polymerase from replicating DNA strand beyond the site of the dimer. There are two ways of correcting such damage:

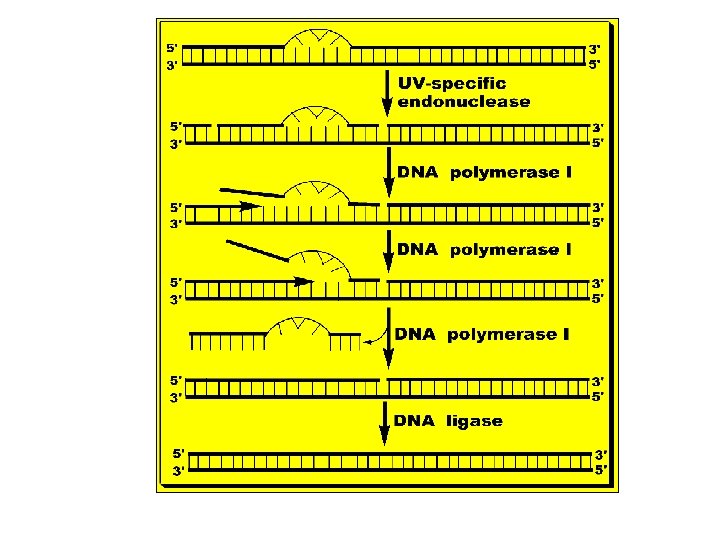

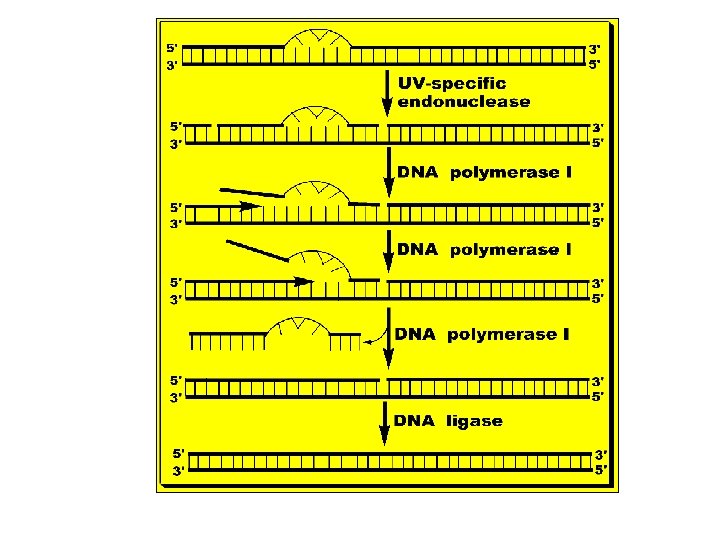

• DNA photolyase enzyme is photo-reactivated by photons of UV or blue spectral region of light to cleave the dimer into its original bases. • UV-specific endonuclease: - This enzyme recognizes the dimer and makes a nick in the affected DNA strand 8 nucleotides away from the dimer site to the 5'-side. DNA polymerase I fills the gap with new nucleotides using the healthy strand as a template in the 5' 3' direction by nick translation. Then, UVspecific endonuclease cut the freed damaged sequence 4 nucleotides from the dimer site away to the 3'-side. Then, the damaged piece of DNA diffuses away. Then, DNA ligase joins the 3' end of the new DNA and the 5' end of the original DNA. See the following figure.

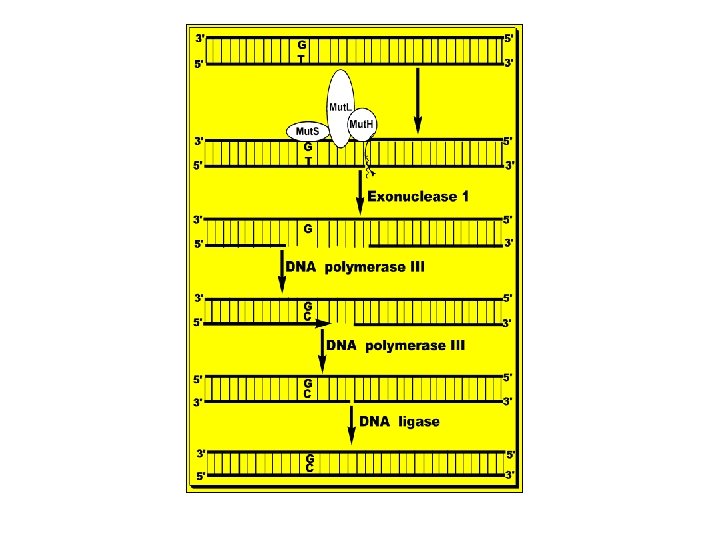

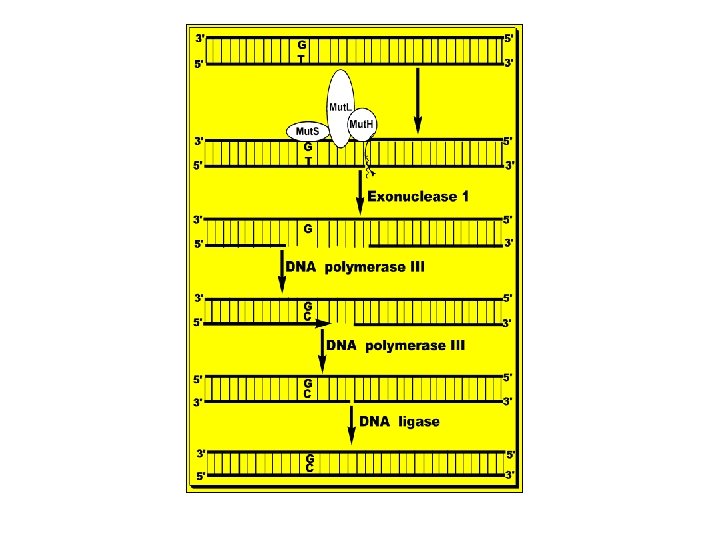

B. Mismatch Repair: • - Mismatch, e. g. , G-T, is due to copying errors during replication that may also lead to 1 - 5 bases unpair loops. • - The mismatch is recognized by a group of proteins called Mut. S, Mut. L and Mut. H that identify the parent DNA strand by its methylation at GATC sequences. Once identified the mismatch, they cut the defective DNA strand at the 3’ side of the mismatch dimer. • - A special exonuclease (exonuclease 1) hydrolyzes DNA in 3' 5' direction to a few nucleotides 5' the mismatch and releases free DNA nucleotides. • - A new DNA is synthesized to fill the gap by DNA polymerase III and DNA ligase joins the 3'-end of the new DNA and the 5'-end of the DNA ahead of it. • - Defects in these Mut proteins lead to specific types of hereditary types of cancer, e. g. , hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, see the figure below.

C. Base excision repair or correction of deamination of cytosine to uracil: • - Oxidative deamination of cytosine into uracil, adenine into hypoxanthine and guanine into xanthine occurs spontaneous, or due to chemical or radiation damage to a single base. • - Since uracil, hypoxanthine and xanthine are foreign to DNA; they are recognized and removed from the DNA strand by specific-DNA glycosylase that cuts the bond between the deoxyribose and the base leaving apyrimidinic or apurinic site, i. e. , AP. • - An AP-endonuclease cuts the deoxyribosephosphate backbone of the affected strand at 5' end of the AP site and removes a few nucleotides.

• - Then, DNA polymerase I excise the residual deoxyribose phosphate unit and inserts cytosine, as dictated by the presence of guanine on the undamaged complementary strand. Then, the deoxyribose-phosphate backbone is rejoined by a Ligase. • - Defective repair of this damage leads to A-U mutation in place of the original G-C because U base pairs with A and in a subsequent replication A-U is replaced by A-T.

2. Recombinational double strand breaks repair: • - The figure below illustrates the mechanism of repair of double DNA strand breaks that are due to ionizing radiation, chemotherapy and oxidative free radicals. • Two proteins are involved; Ku and DNA-dependent protein kinase. Both of them attach to each end of the double strand break, activate one another, unwind the duplex (Ku has helicase activity) and search for the closest DNA sequence of minimum complementarity in the opposite strands. • - The extranucleotide tails are degraded into free nucleotides by exonuclease and the gaps are filled by DNA polymerase III and DNA ligase seals the free ends.

Diseases related to defective repair of DNA damage: I- Xeroderma Pigmentosum: • - It is an autosomal recessive disease. It is an example of a defective mechanism for the repair of pyrimidine dimers in DNA. It is due to absence of the UV-specific endonuclease enzyme and defective correction of thymine dimer. Patients are highly sensitive to sunlight or UV light and their skin cells contain multiple thymine dimer. They develop skin cancer. II- Ataxia Telangiectasia: • - It is an autosomal recessive disease. Ataxia and malignant neoplasms of the reticuloendothelial system are the major symptoms. There is impaired repair of DNA strand breaks leading to increased sensitivity to X-ray-induced damage.

III- Fanconi’s Anemia: • - It is an autosomal recessive anemia. It is associated with increased susceptibility to malignant neoplasms. It is due to failure of correction of cross-linkage damage, e. g. , thymine dimer. IV- Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer (HPCC): • - It is Lynch syndrome in which patients develop cancer in the colon with cancer also in stomach and/or uterus. It is due to defective DNA mismatch repair due to mutations in two genes, h. MSH 2 and h. MLH 1 (human analogs of Mut. S and L).