Redox reactions In a similar way that acids

![Carbonate chemistry Ksp = [Me 2+] [CO 32 - ] = CT/([H+]2/K 1 K Carbonate chemistry Ksp = [Me 2+] [CO 32 - ] = CT/([H+]2/K 1 K](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5b6153e6c314585e79f3533e661cfcb9/image-40.jpg)

- Slides: 59

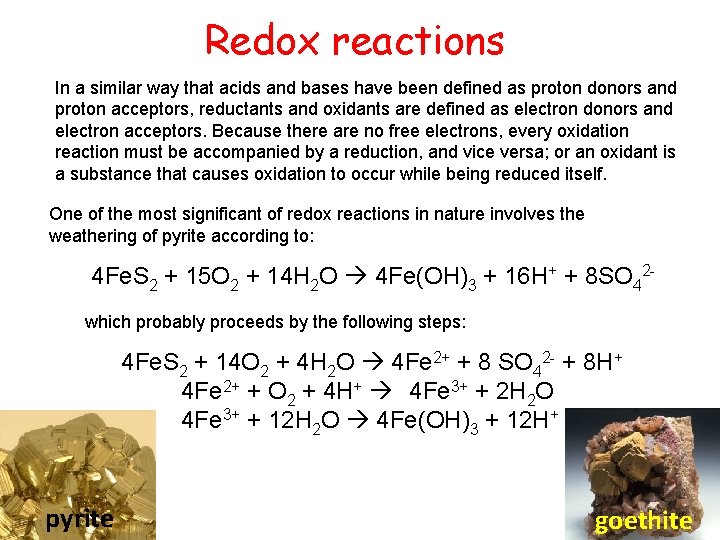

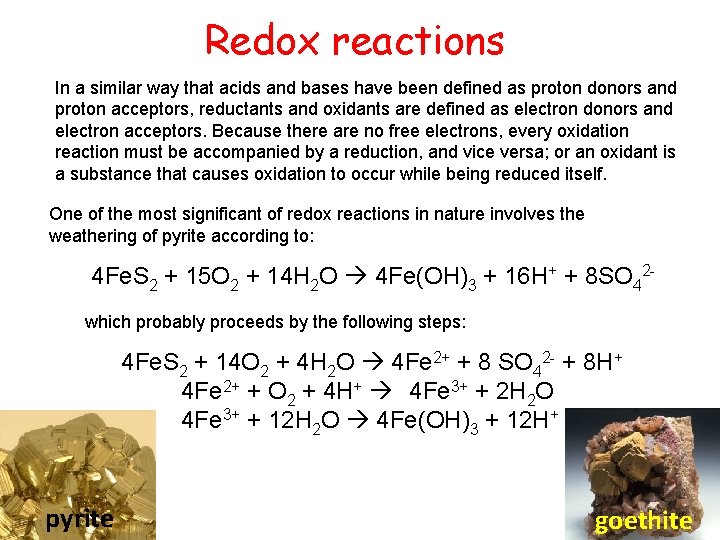

Redox reactions In a similar way that acids and bases have been defined as proton donors and proton acceptors, reductants and oxidants are defined as electron donors and electron acceptors. Because there are no free electrons, every oxidation reaction must be accompanied by a reduction, and vice versa; or an oxidant is a substance that causes oxidation to occur while being reduced itself. One of the most significant of redox reactions in nature involves the weathering of pyrite according to: 4 Fe. S 2 + 15 O 2 + 14 H 2 O 4 Fe(OH)3 + 16 H+ + 8 SO 42 which probably proceeds by the following steps: 4 Fe. S 2 + 14 O 2 + 4 H 2 O 4 Fe 2+ + 8 SO 42 - + 8 H+ 4 Fe 2+ + O 2 + 4 H+ 4 Fe 3+ + 2 H 2 O 4 Fe 3+ + 12 H 2 O 4 Fe(OH)3 + 12 H+ pyrite goethite

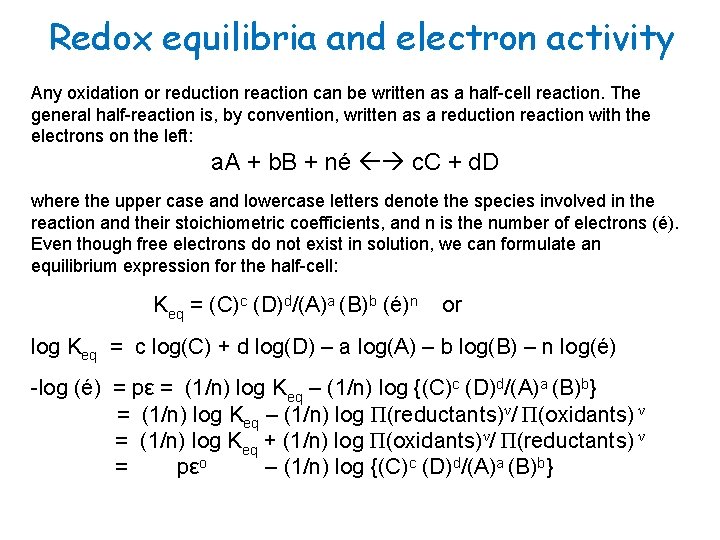

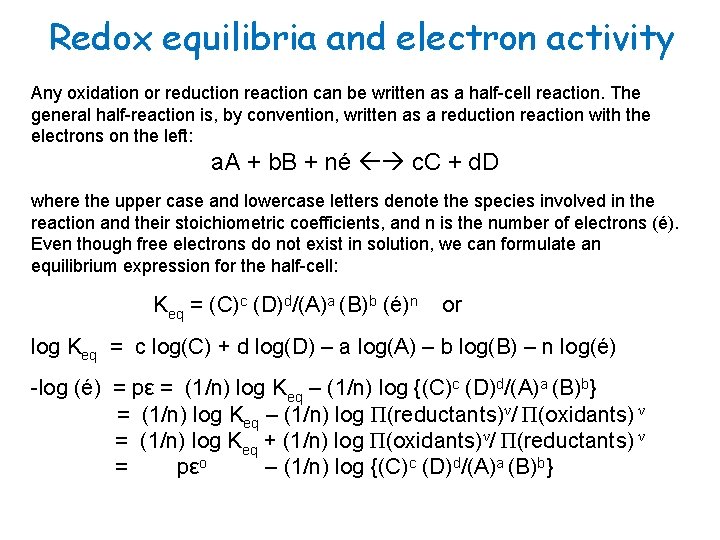

Redox equilibria and electron activity Any oxidation or reduction reaction can be written as a half-cell reaction. The general half-reaction is, by convention, written as a reduction reaction with the electrons on the left: a. A + b. B + né c. C + d. D where the upper case and lowercase letters denote the species involved in the reaction and their stoichiometric coefficients, and n is the number of electrons (é). Even though free electrons do not exist in solution, we can formulate an equilibrium expression for the half-cell: Keq = (C)c (D)d/(A)a (B)b (é)n or log Keq = c log(C) + d log(D) – a log(A) – b log(B) – n log(é) -log (é) = pε = (1/n) log Keq – (1/n) log {(C)c (D)d/(A)a (B)b} = (1/n) log Keq – (1/n) log Π(reductants)ν/ Π(oxidants) ν = (1/n) log Keq + (1/n) log Π(oxidants)ν/ Π(reductants) ν = pεo – (1/n) log {(C)c (D)d/(A)a (B)b}

Electron activity and the Nernst equation pεo = 1/n log Koeq = -(1/n) ΔGorx/2. 303 RT = Eoh /(2. 303 RTF-1) or ΔGorx = -RT ln Koeq = -2. 303 RTn pεo = -n. FEoh thus, Eh = Eoh - 2. 303 (RT/n. F) · log (C)c(D)d/(A)a (B)b where Eoh is the equilibrium redox potential (volts, w/r hydrogen electrode), related to the free energy of the reaction, R is the gas constant, T is the absolute temperature and F is the Faraday constant = 96, 490 C mol-1. The term (2. 303 RT/F) is called the Nernst factor and is equal to 0. 05916 volts at 25 o. C. The above expression is know as the Nernst equation.

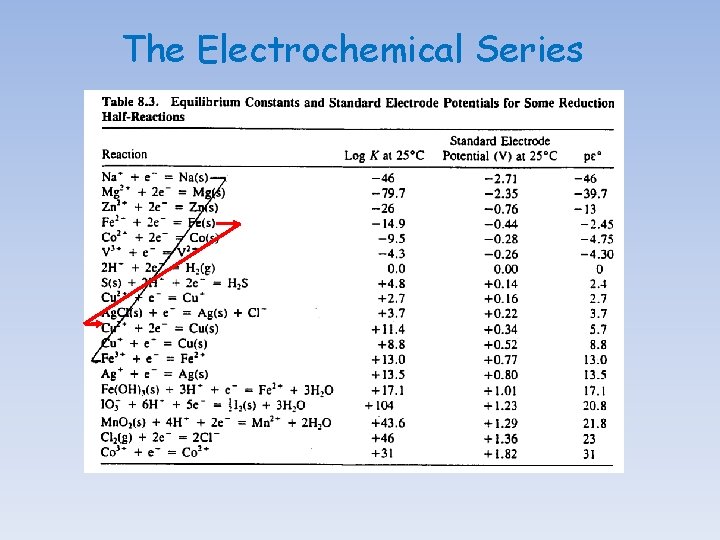

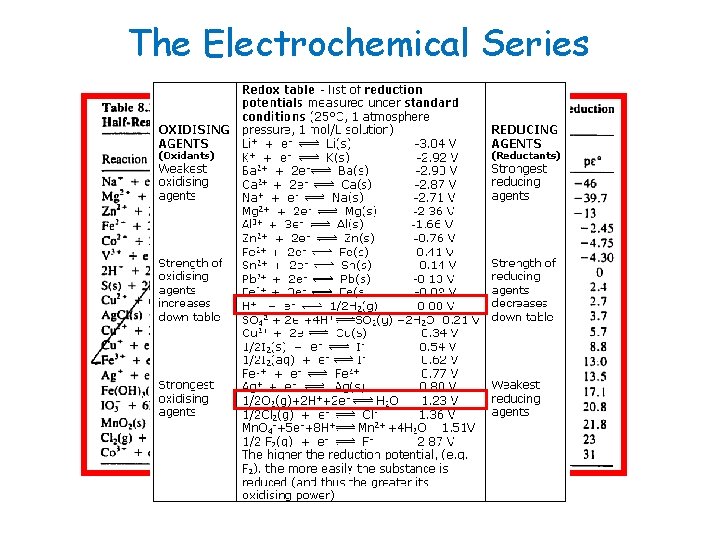

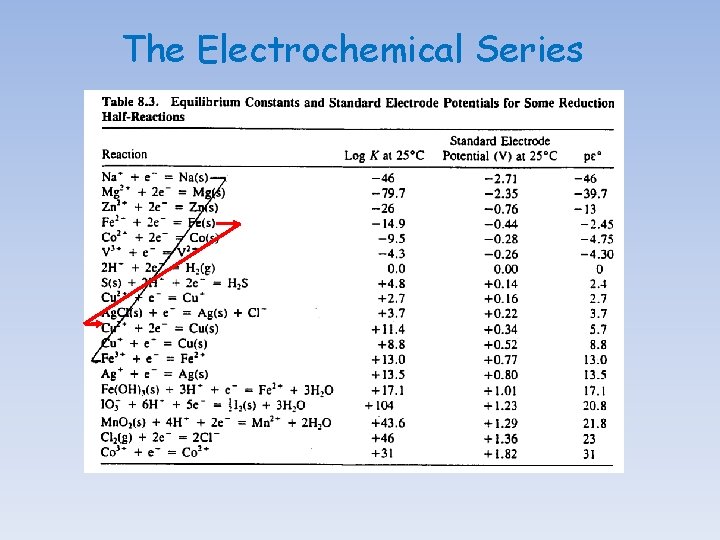

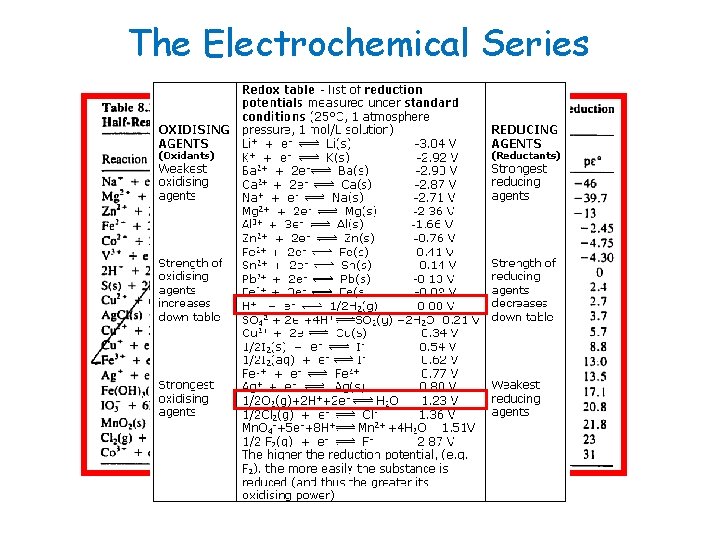

The Electrochemical Series

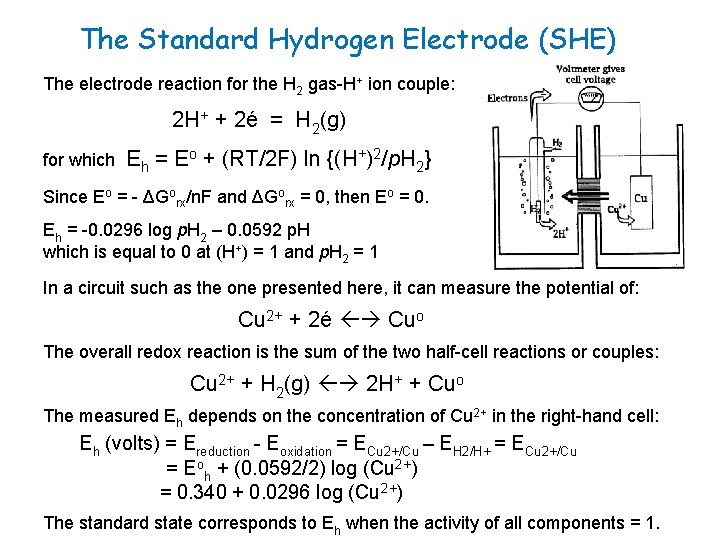

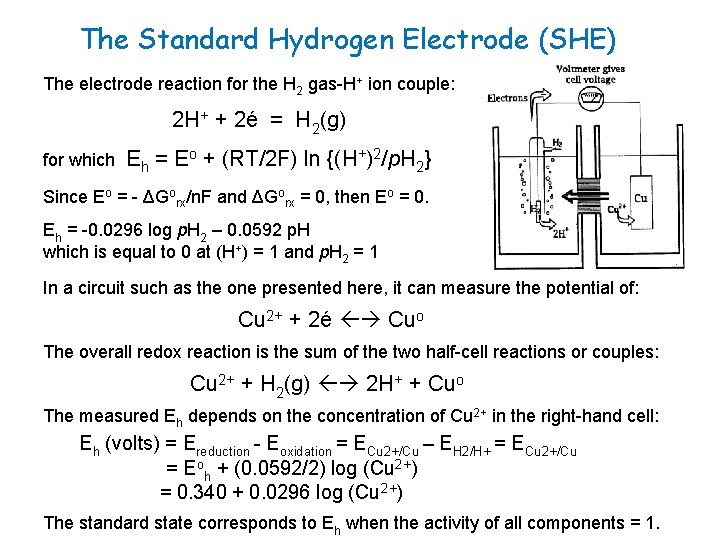

The Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE) The electrode reaction for the H 2 gas-H+ ion couple: 2 H+ + 2é = H 2(g) for which Eh = Eo + (RT/2 F) ln {(H+)2/p. H 2} Since Eo = - ΔGorx/n. F and ΔGorx = 0, then Eo = 0. Eh = -0. 0296 log p. H 2 – 0. 0592 p. H which is equal to 0 at (H+) = 1 and p. H 2 = 1 In a circuit such as the one presented here, it can measure the potential of: Cu 2+ + 2é Cuo The overall redox reaction is the sum of the two half-cell reactions or couples: Cu 2+ + H 2(g) 2 H+ + Cuo The measured Eh depends on the concentration of Cu 2+ in the right-hand cell: Eh (volts) = Ereduction - Eoxidation = ECu 2+/Cu – EH 2/H+ = ECu 2+/Cu = Eoh + (0. 0592/2) log (Cu 2+) = 0. 340 + 0. 0296 log (Cu 2+) The standard state corresponds to Eh when the activity of all components = 1.

The Electrochemical Series

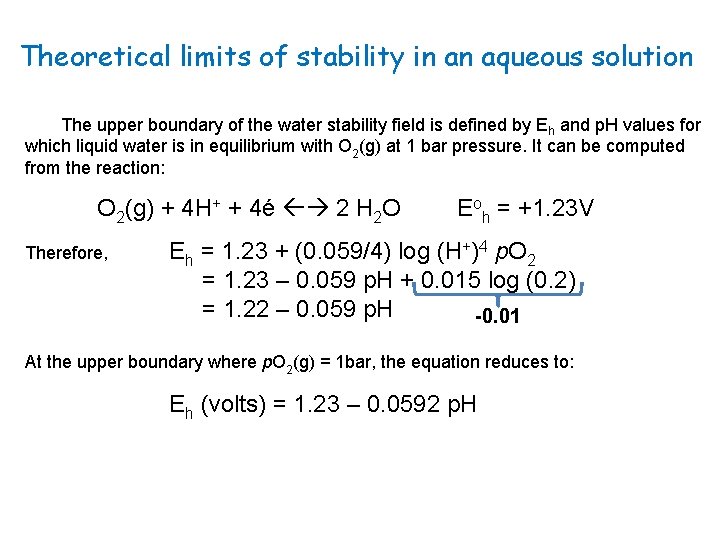

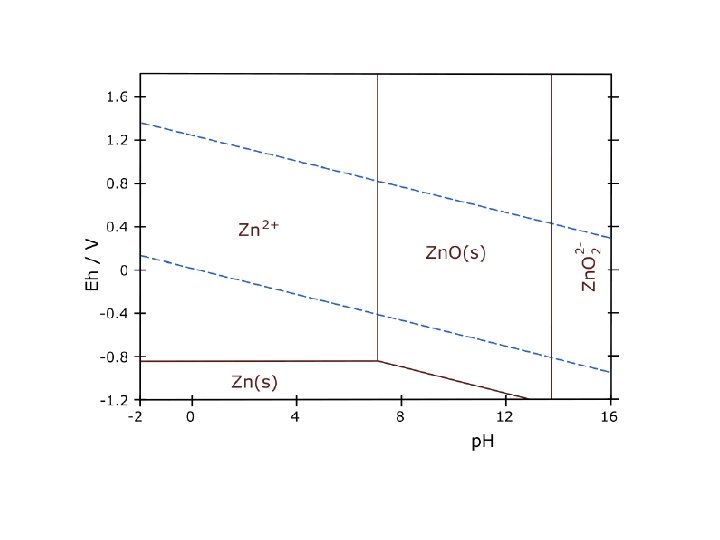

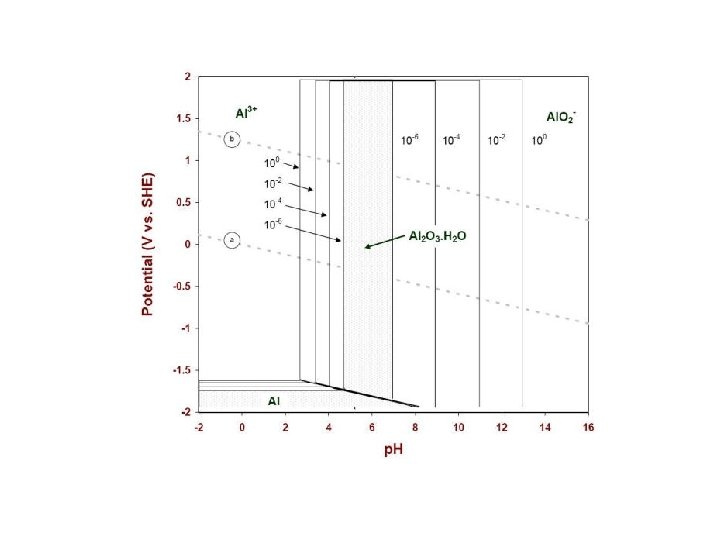

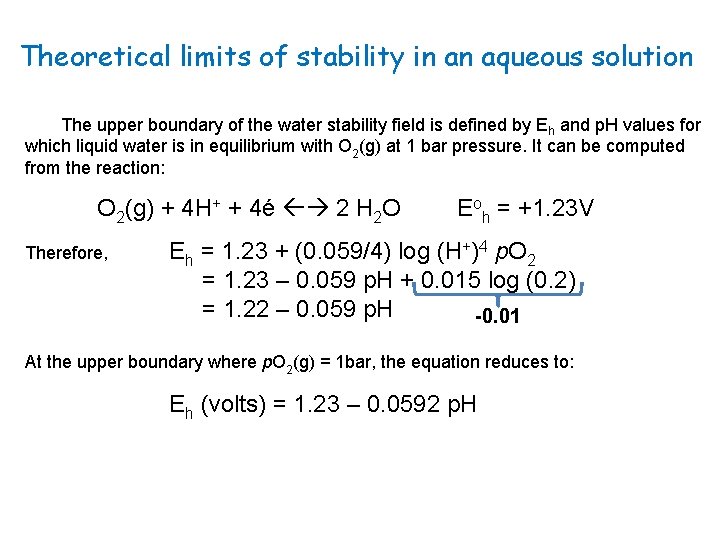

Theoretical limits of stability in an aqueous solution The upper boundary of the water stability field is defined by Eh and p. H values for which liquid water is in equilibrium with O 2(g) at 1 bar pressure. It can be computed from the reaction: O 2(g) + 4 H+ + 4é 2 H 2 O Therefore, Eoh = +1. 23 V Eh = 1. 23 + (0. 059/4) log (H+)4 p. O 2 = 1. 23 – 0. 059 p. H + 0. 015 log (0. 2) = 1. 22 – 0. 059 p. H -0. 01 At the upper boundary where p. O 2(g) = 1 bar, the equation reduces to: Eh (volts) = 1. 23 – 0. 0592 p. H

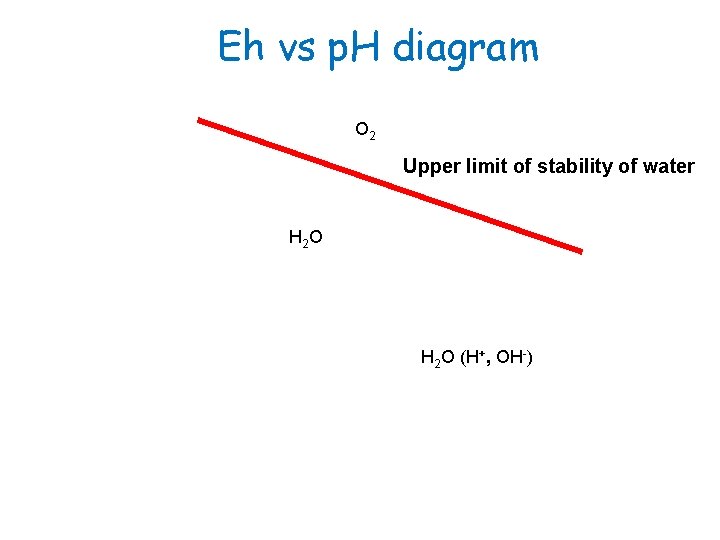

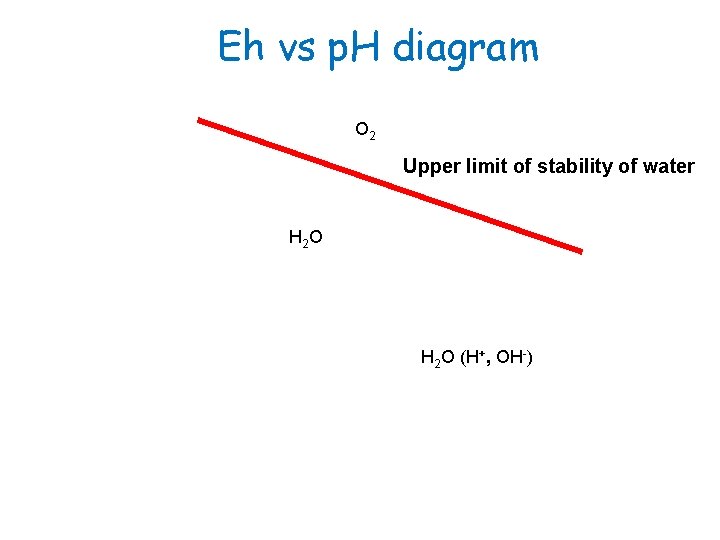

Eh vs p. H diagram O 2 Upper limit of stability of water H 2 O H 2 O (H+, OH-)

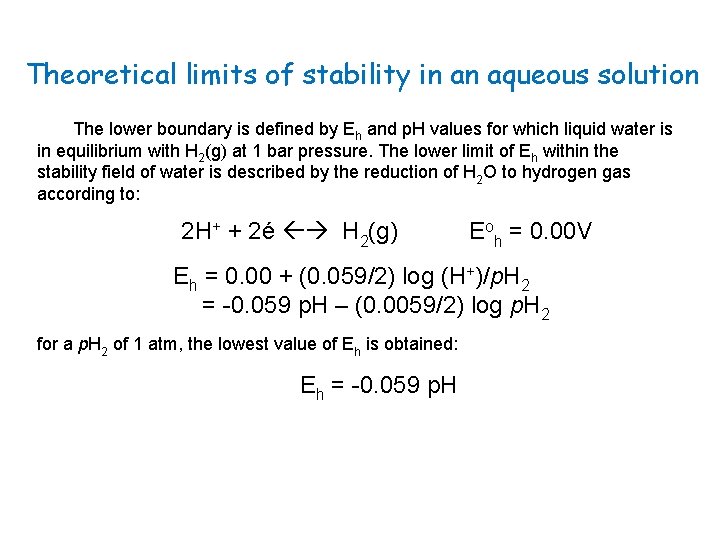

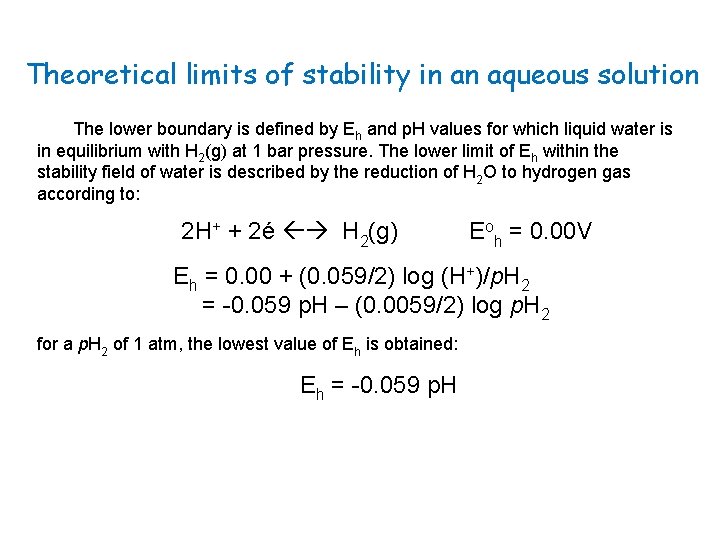

Theoretical limits of stability in an aqueous solution The lower boundary is defined by Eh and p. H values for which liquid water is in equilibrium with H 2(g) at 1 bar pressure. The lower limit of Eh within the stability field of water is described by the reduction of H 2 O to hydrogen gas according to: 2 H+ + 2é H 2(g) Eoh = 0. 00 V Eh = 0. 00 + (0. 059/2) log (H+)/p. H 2 = -0. 059 p. H – (0. 0059/2) log p. H 2 for a p. H 2 of 1 atm, the lowest value of Eh is obtained: Eh = -0. 059 p. H

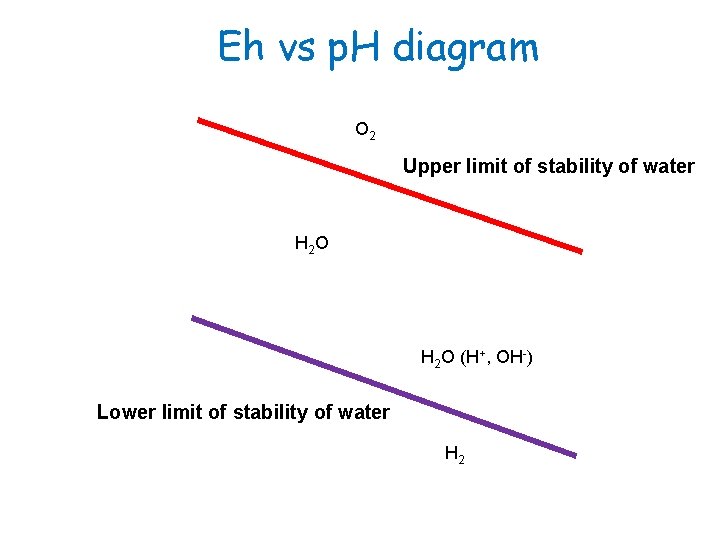

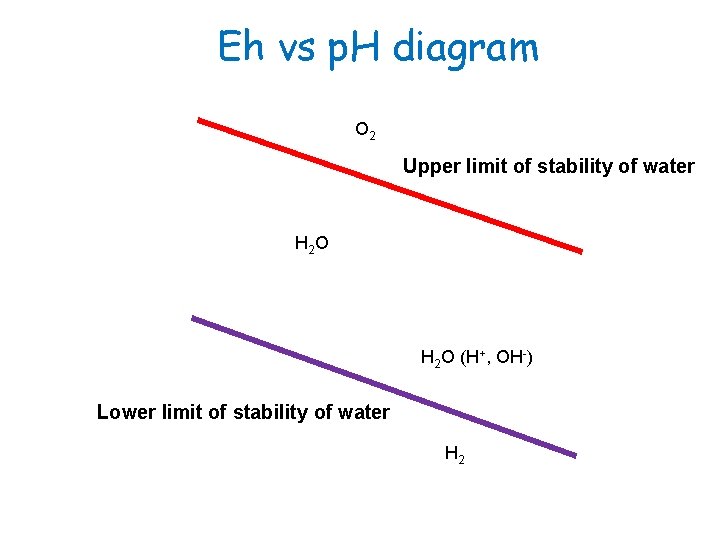

Eh vs p. H diagram O 2 Upper limit of stability of water H 2 O H 2 O (H+, OH-) Lower limit of stability of water H 2

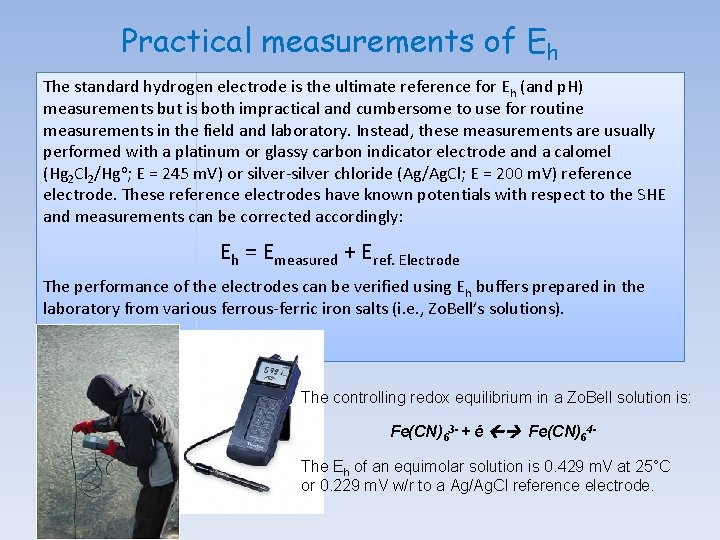

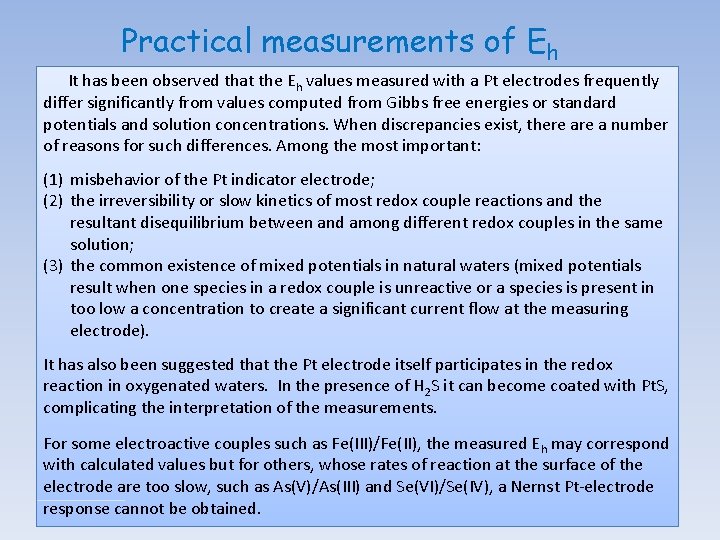

Practical measurements of Eh The standard hydrogen electrode is the ultimate reference for Eh (and p. H) measurements but is both impractical and cumbersome to use for routine measurements in the field and laboratory. Instead, these measurements are usually performed with a platinum or glassy carbon indicator electrode and a calomel (Hg 2 Cl 2/Hgo; E = 245 m. V) or silver-silver chloride (Ag/Ag. Cl; E = 200 m. V) reference electrode. These reference electrodes have known potentials with respect to the SHE and measurements can be corrected accordingly: Eh = Emeasured + Eref. Electrode The performance of the electrodes can be verified using Eh buffers prepared in the laboratory from various ferrous-ferric iron salts (i. e. , Zo. Bell’s solutions). The controlling redox equilibrium in a Zo. Bell solution is: Fe(CN)63 - + é Fe(CN)64 The Eh of an equimolar solution is 0. 429 m. V at 25°C or 0. 229 m. V w/r to a Ag/Ag. Cl reference electrode.

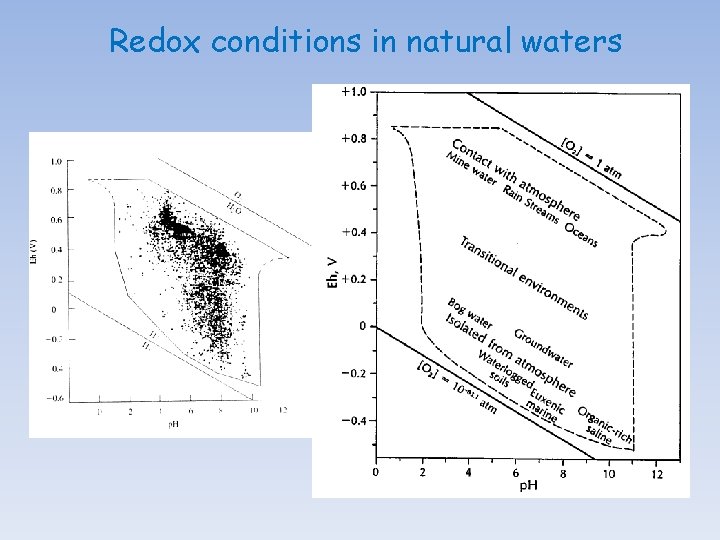

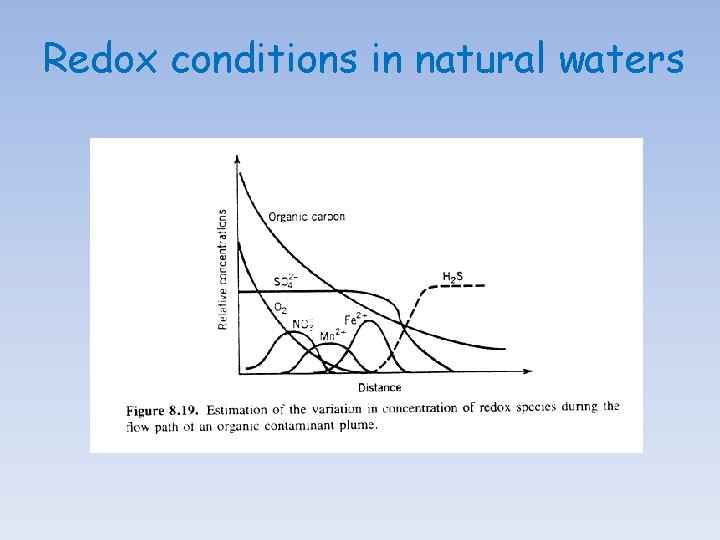

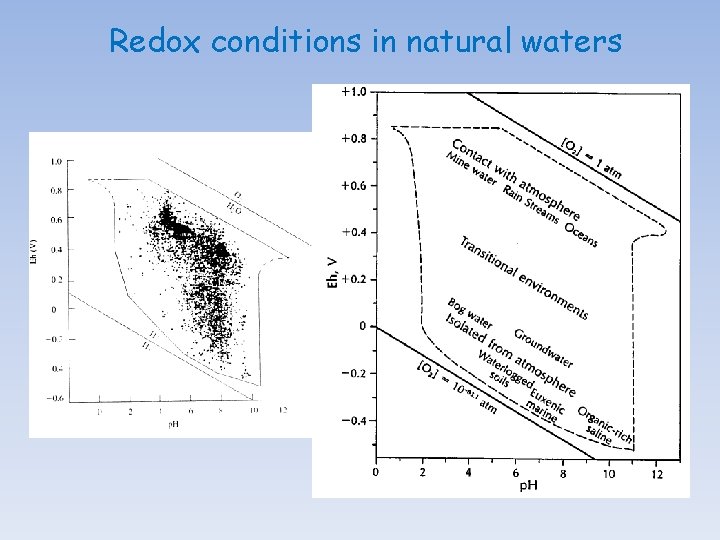

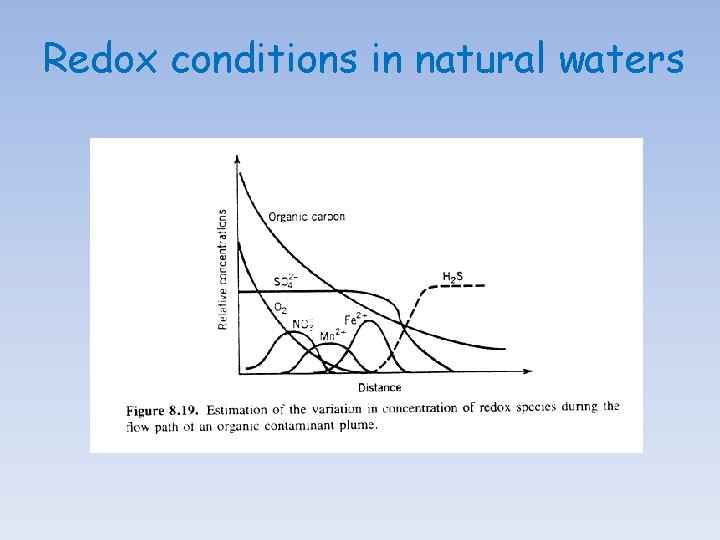

Redox conditions in natural waters

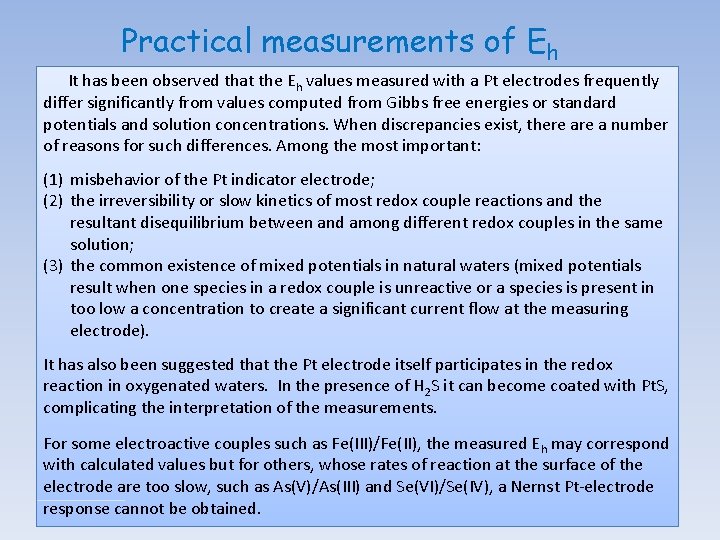

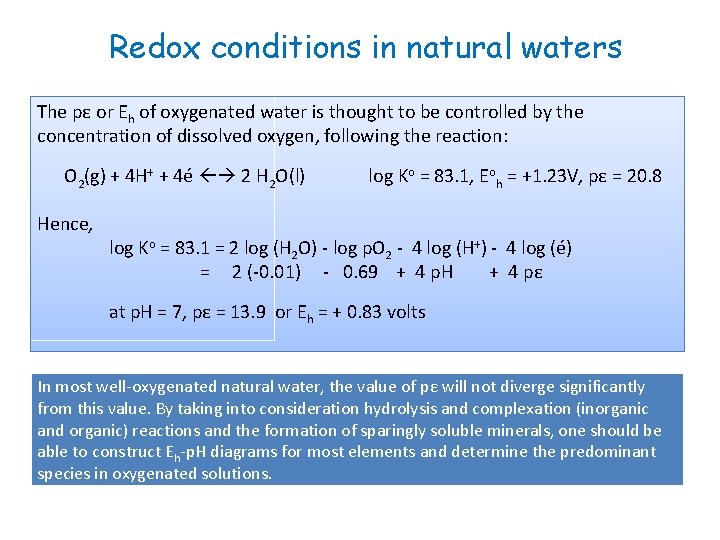

Practical measurements of Eh It has been observed that the Eh values measured with a Pt electrodes frequently differ significantly from values computed from Gibbs free energies or standard potentials and solution concentrations. When discrepancies exist, there a number of reasons for such differences. Among the most important: (1) misbehavior of the Pt indicator electrode; (2) the irreversibility or slow kinetics of most redox couple reactions and the resultant disequilibrium between and among different redox couples in the same solution; (3) the common existence of mixed potentials in natural waters (mixed potentials result when one species in a redox couple is unreactive or a species is present in too low a concentration to create a significant current flow at the measuring electrode). It has also been suggested that the Pt electrode itself participates in the redox reaction in oxygenated waters. In the presence of H 2 S it can become coated with Pt. S, complicating the interpretation of the measurements. For some electroactive couples such as Fe(III)/Fe(II), the measured E h may correspond with calculated values but for others, whose rates of reaction at the surface of the electrode are too slow, such as As(V)/As(III) and Se(VI)/Se(IV), a Nernst Pt-electrode response cannot be obtained.

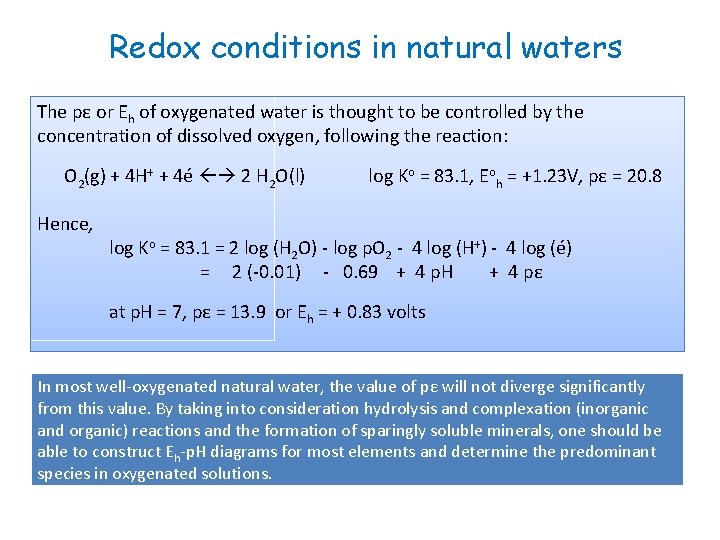

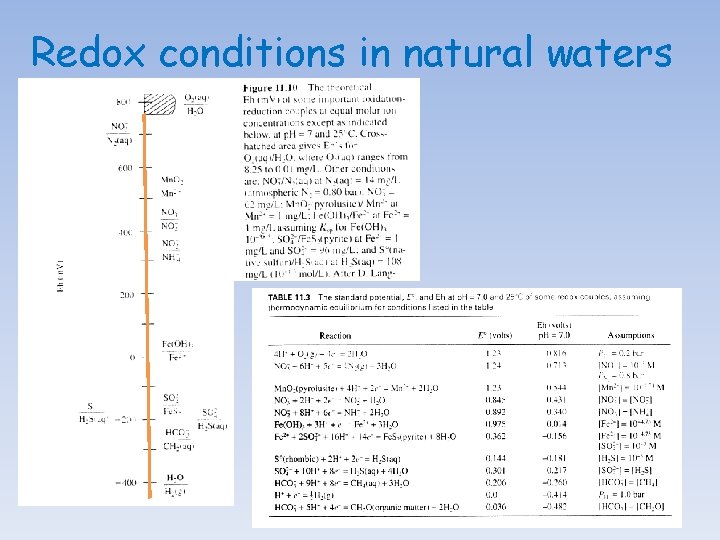

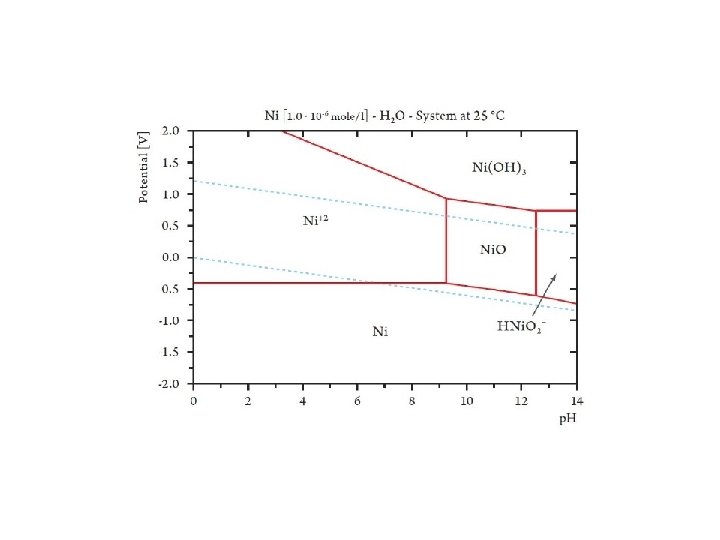

Redox conditions in natural waters The pε or Eh of oxygenated water is thought to be controlled by the concentration of dissolved oxygen, following the reaction: O 2(g) + 4 H+ + 4é 2 H 2 O(l) Hence, log Ko = 83. 1, Eoh = +1. 23 V, pε = 20. 8 log Ko = 83. 1 = 2 log (H 2 O) - log p. O 2 - 4 log (H+) - 4 log (é) = 2 (-0. 01) - 0. 69 + 4 p. H + 4 pε at p. H = 7, pε = 13. 9 or Eh = + 0. 83 volts In most well-oxygenated natural water, the value of pε will not diverge significantly from this value. By taking into consideration hydrolysis and complexation (inorganic and organic) reactions and the formation of sparingly soluble minerals, one should be able to construct Eh-p. H diagrams for most elements and determine the predominant species in oxygenated solutions.

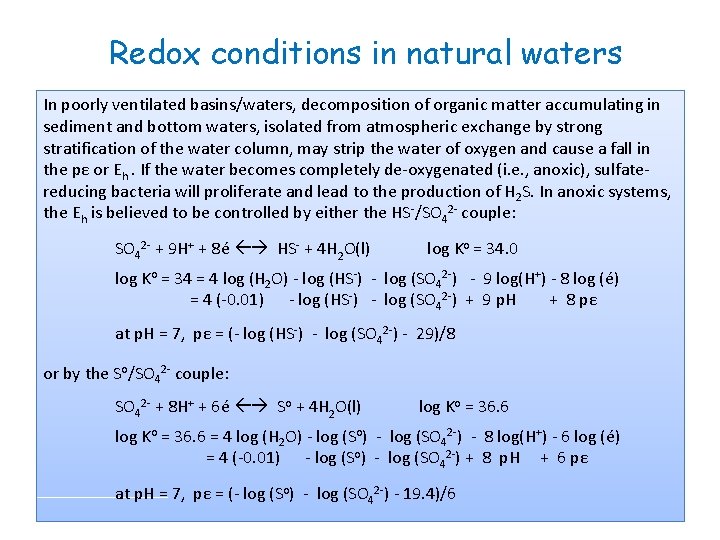

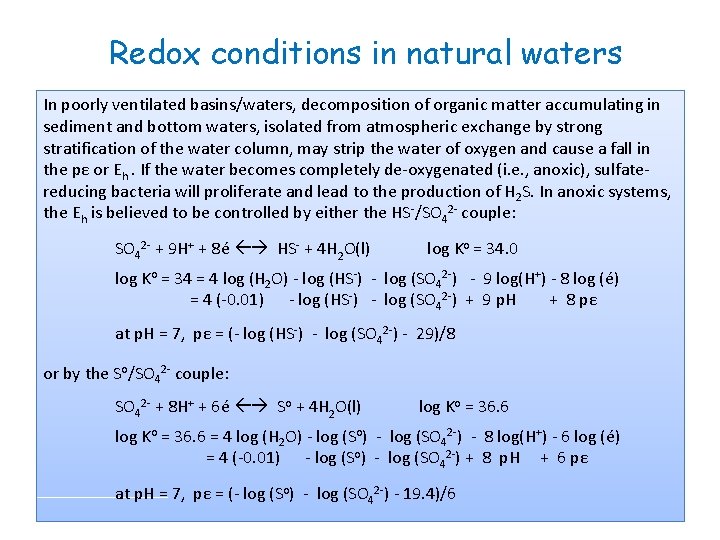

Redox conditions in natural waters In poorly ventilated basins/waters, decomposition of organic matter accumulating in sediment and bottom waters, isolated from atmospheric exchange by strong stratification of the water column, may strip the water of oxygen and cause a fall in the pε or Eh. If the water becomes completely de-oxygenated (i. e. , anoxic), sulfatereducing bacteria will proliferate and lead to the production of H 2 S. In anoxic systems, the Eh is believed to be controlled by either the HS-/SO 42 - couple: SO 42 - + 9 H+ + 8é HS- + 4 H 2 O(l) log Ko = 34. 0 log Ko = 34 = 4 log (H 2 O) - log (HS-) - log (SO 42 -) - 9 log(H+) - 8 log (é) = 4 (-0. 01) - log (HS-) - log (SO 42 -) + 9 p. H + 8 pε at p. H = 7, pε = (- log (HS-) - log (SO 42 -) - 29)/8 or by the So/SO 42 - couple: SO 42 - + 8 H+ + 6é So + 4 H 2 O(l) log Ko = 36. 6 = 4 log (H 2 O) - log (So) - log (SO 42 -) - 8 log(H+) - 6 log (é) = 4 (-0. 01) - log (So) - log (SO 42 -) + 8 p. H + 6 pε at p. H = 7, pε = (- log (So) - log (SO 42 -) - 19. 4)/6

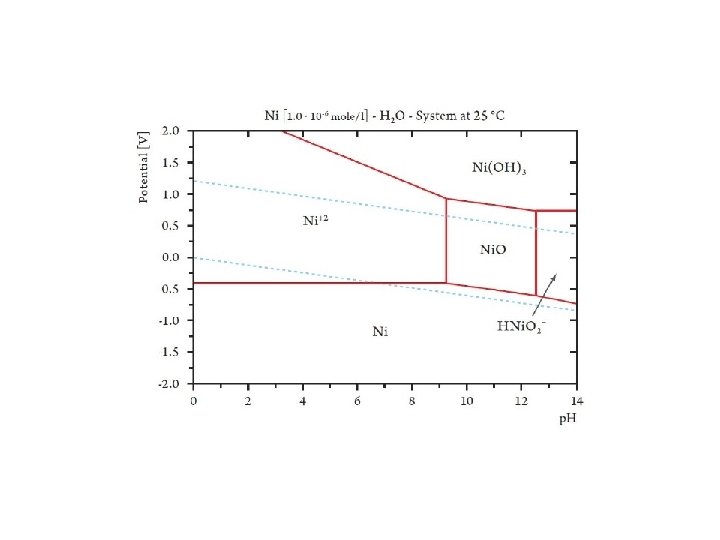

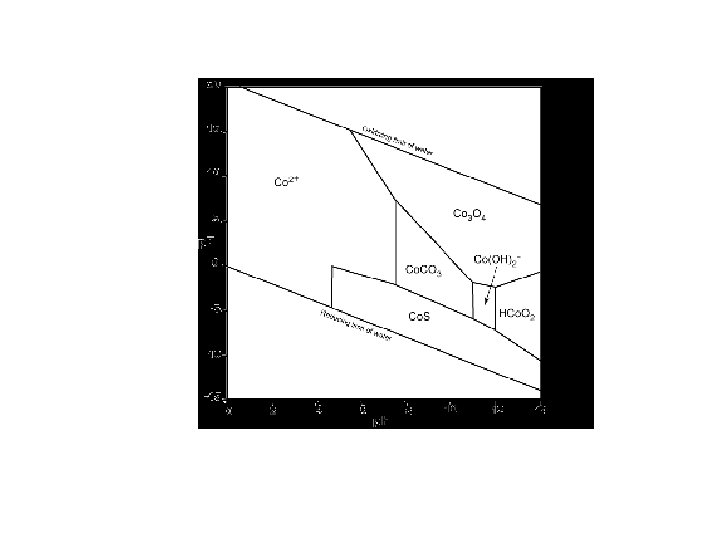

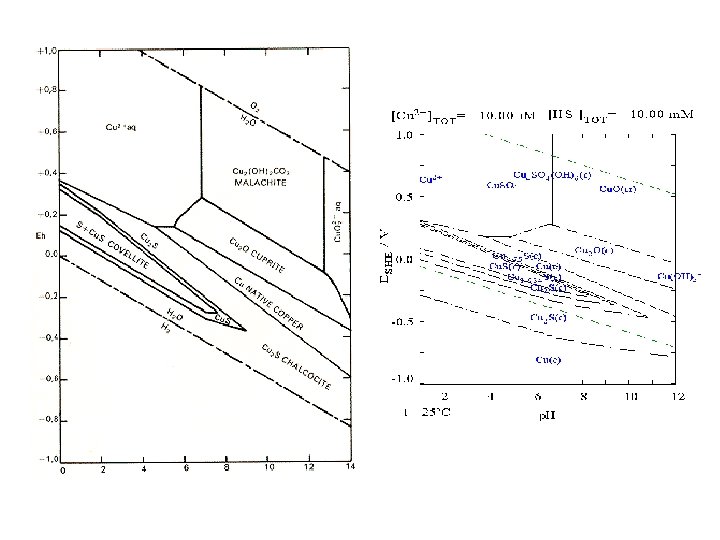

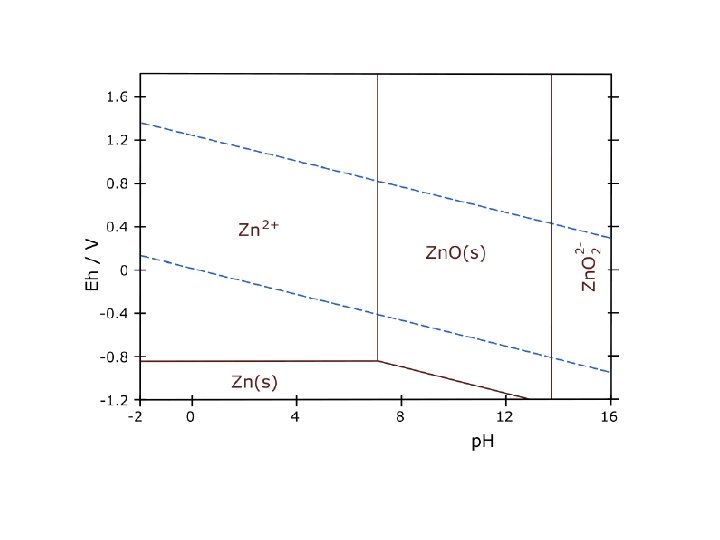

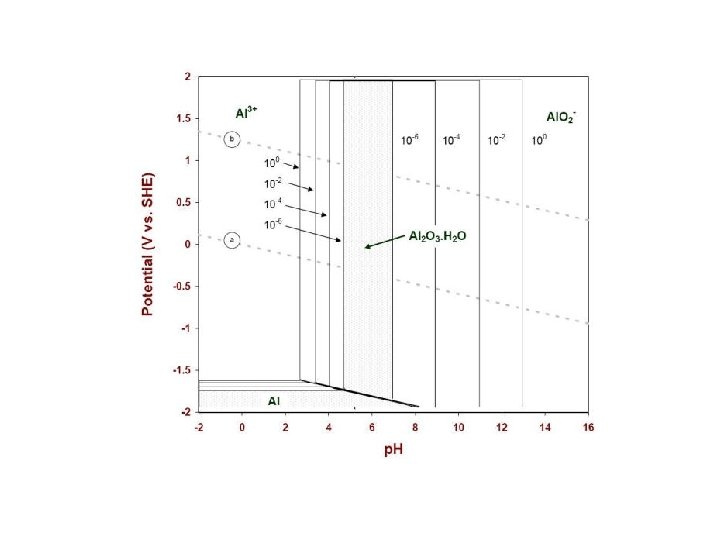

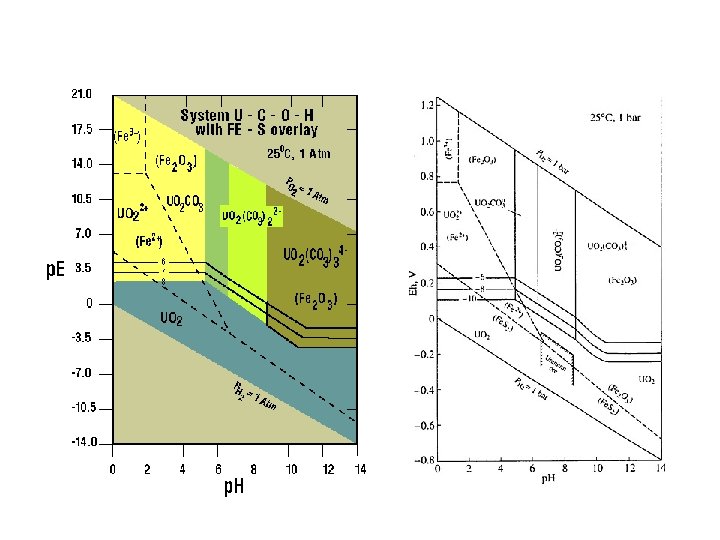

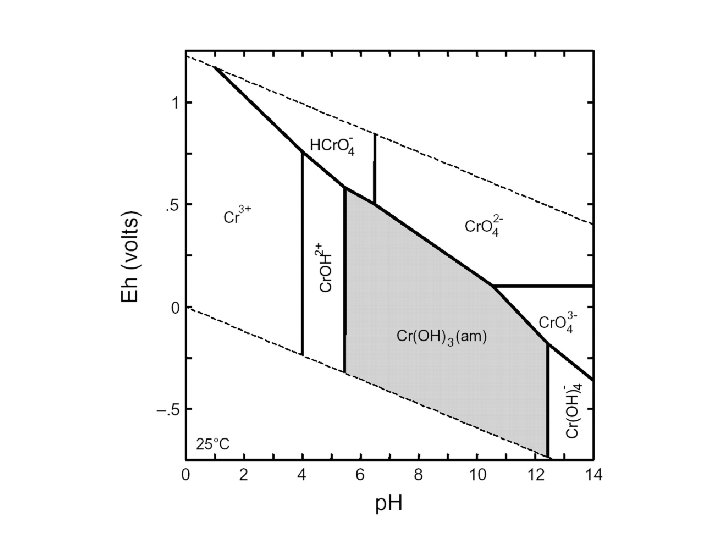

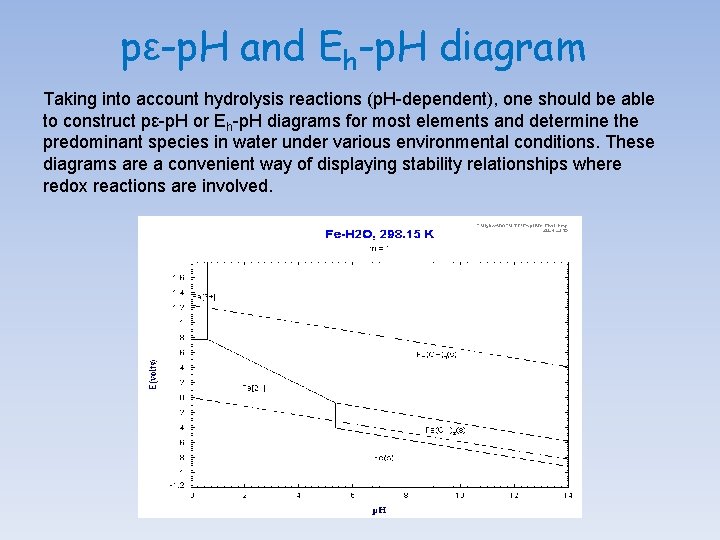

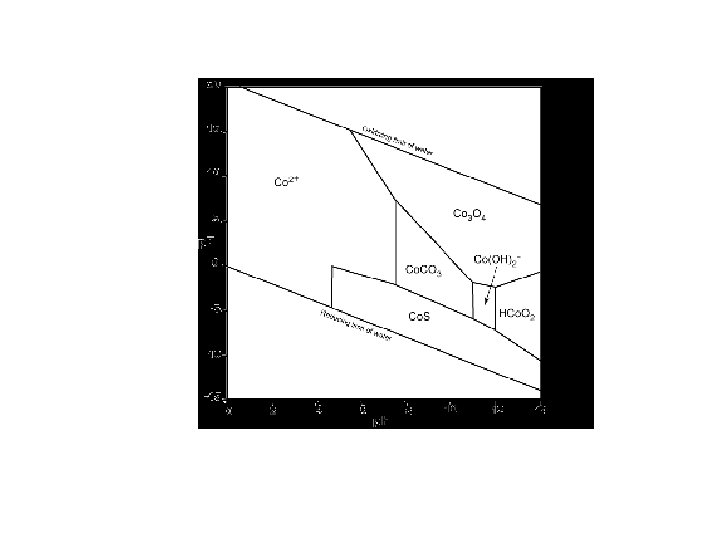

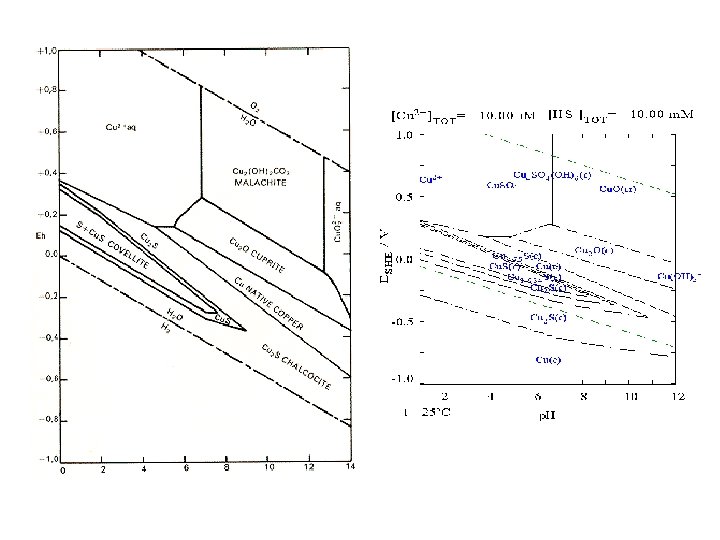

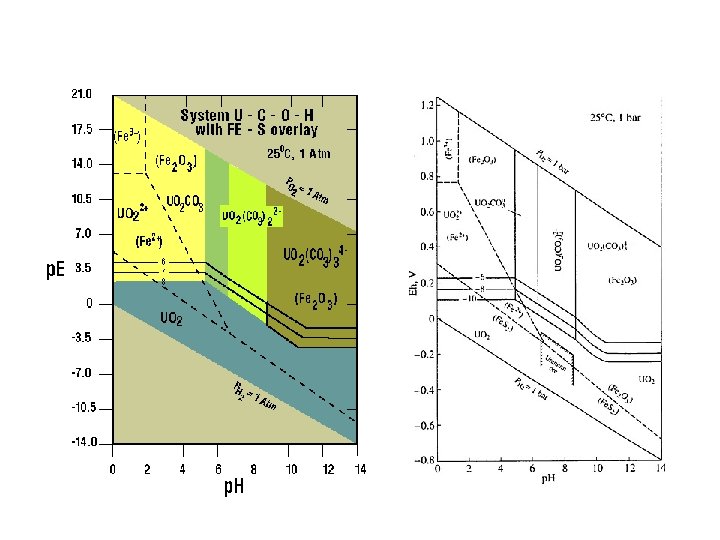

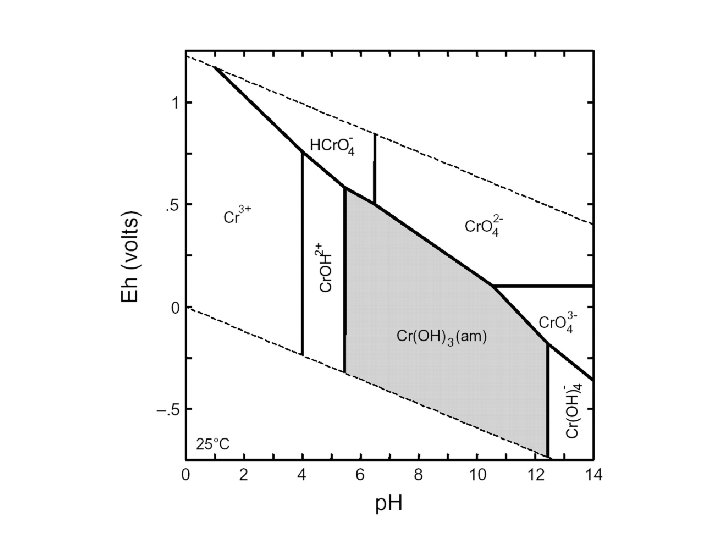

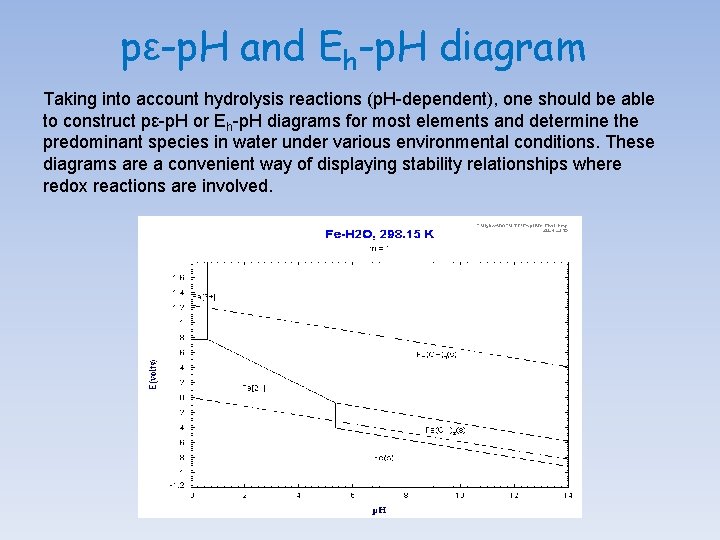

pε-p. H and Eh-p. H diagram Taking into account hydrolysis reactions (p. H-dependent), one should be able to construct pε-p. H or Eh-p. H diagrams for most elements and determine the predominant species in water under various environmental conditions. These diagrams are a convenient way of displaying stability relationships where redox reactions are involved.

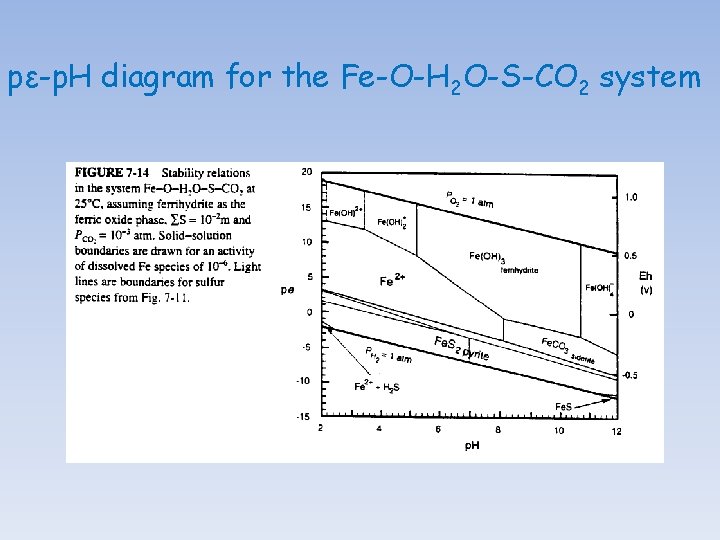

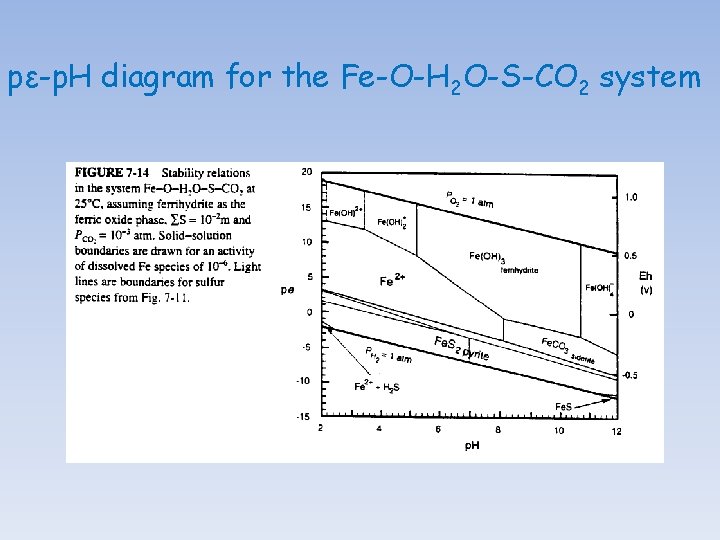

pε-p. H diagram for the Fe-O-H 2 O-S-CO 2 system

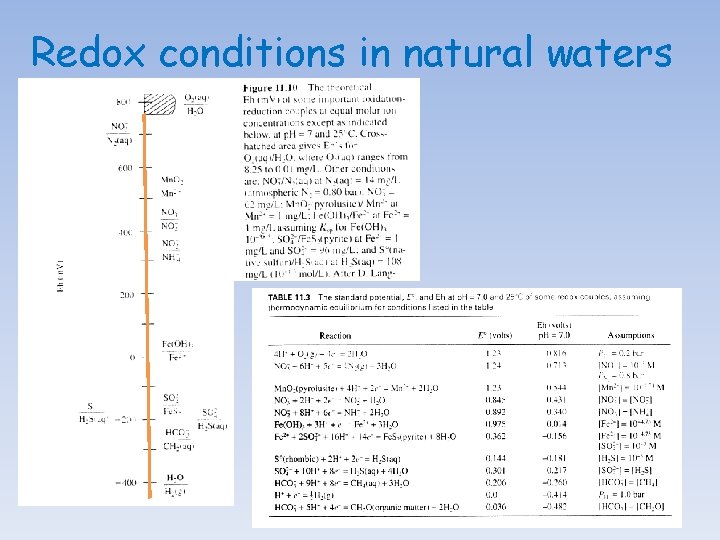

Redox conditions in natural waters

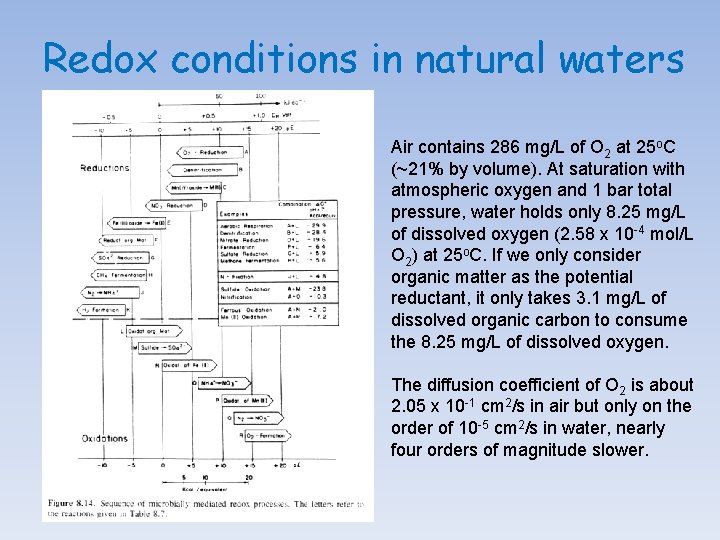

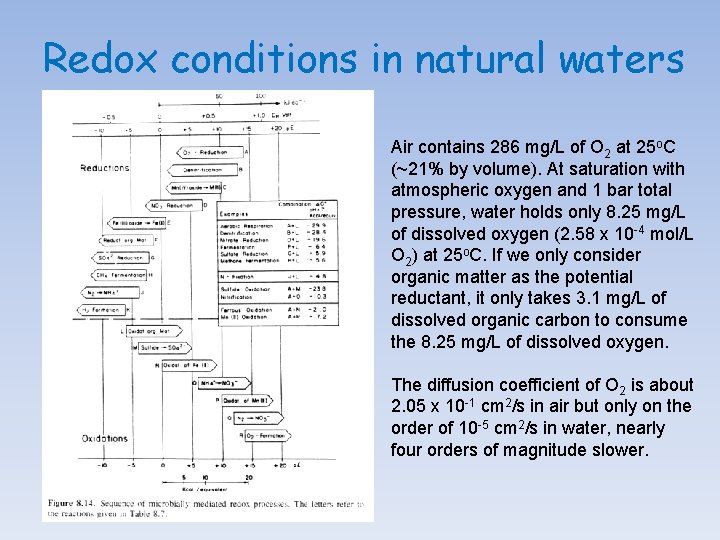

Redox conditions in natural waters Air contains 286 mg/L of O 2 at 25 o. C (~21% by volume). At saturation with atmospheric oxygen and 1 bar total pressure, water holds only 8. 25 mg/L of dissolved oxygen (2. 58 x 10 -4 mol/L O 2) at 25 o. C. If we only consider organic matter as the potential reductant, it only takes 3. 1 mg/L of dissolved organic carbon to consume the 8. 25 mg/L of dissolved oxygen. The diffusion coefficient of O 2 is about 2. 05 x 10 -1 cm 2/s in air but only on the order of 10 -5 cm 2/s in water, nearly four orders of magnitude slower.

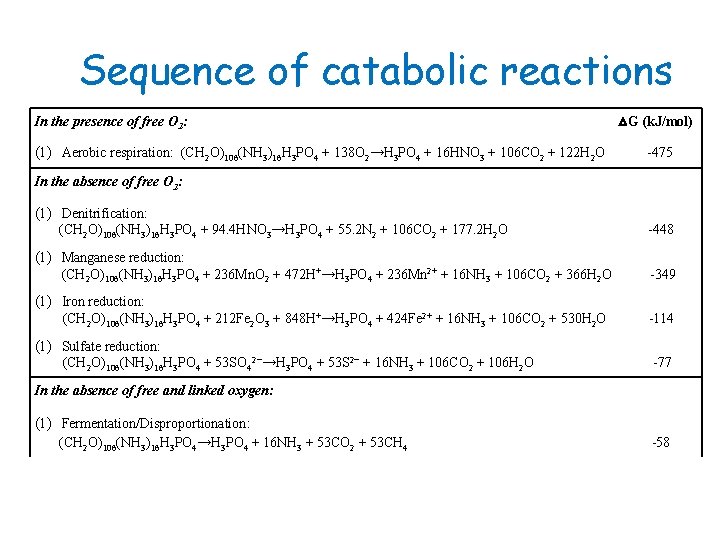

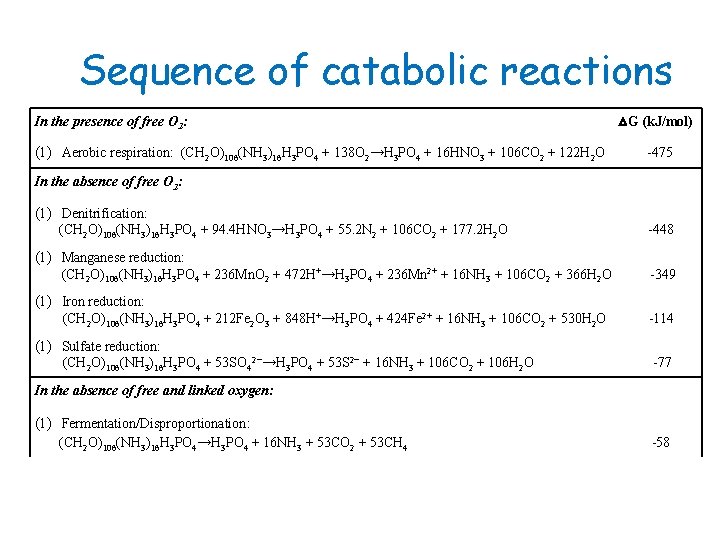

Sequence of catabolic reactions In the presence of free O 2: (1) Aerobic respiration: (CH 2 O)106(NH 3)16 H 3 PO 4 + 138 O 2→H 3 PO 4 + 16 HNO 3 + 106 CO 2 + 122 H 2 O △G (k. J/mol) -475 In the absence of free O 2: (1) Denitrification: (CH 2 O)106(NH 3)16 H 3 PO 4 + 94. 4 HNO 3→H 3 PO 4 + 55. 2 N 2 + 106 CO 2 + 177. 2 H 2 O -448 (1) Manganese reduction: (CH 2 O)106(NH 3)16 H 3 PO 4 + 236 Mn. O 2 + 472 H+→H 3 PO 4 + 236 Mn 2+ + 16 NH 3 + 106 CO 2 + 366 H 2 O -349 (1) Iron reduction: (CH 2 O)106(NH 3)16 H 3 PO 4 + 212 Fe 2 O 3 + 848 H+→H 3 PO 4 + 424 Fe 2+ + 16 NH 3 + 106 CO 2 + 530 H 2 O -114 (1) Sulfate reduction: (CH 2 O)106(NH 3)16 H 3 PO 4 + 53 SO 42−→H 3 PO 4 + 53 S 2− + 16 NH 3 + 106 CO 2 + 106 H 2 O -77 In the absence of free and linked oxygen: (1) Fermentation/Disproportionation: (CH 2 O)106(NH 3)16 H 3 PO 4→H 3 PO 4 + 16 NH 3 + 53 CO 2 + 53 CH 4 -58

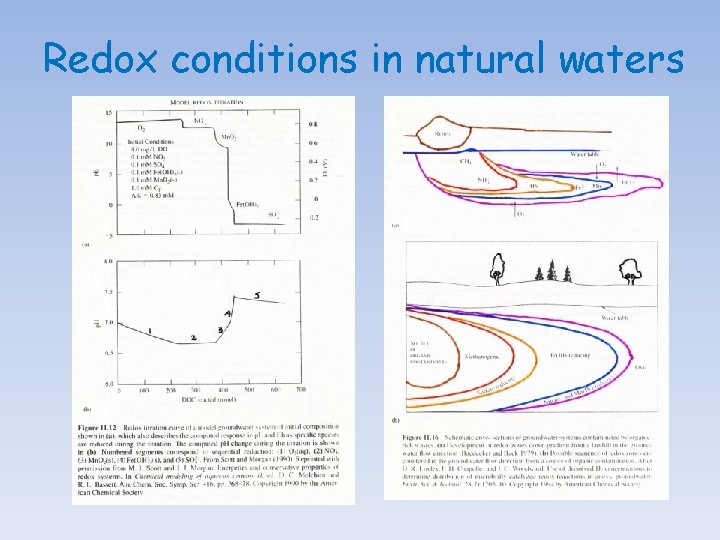

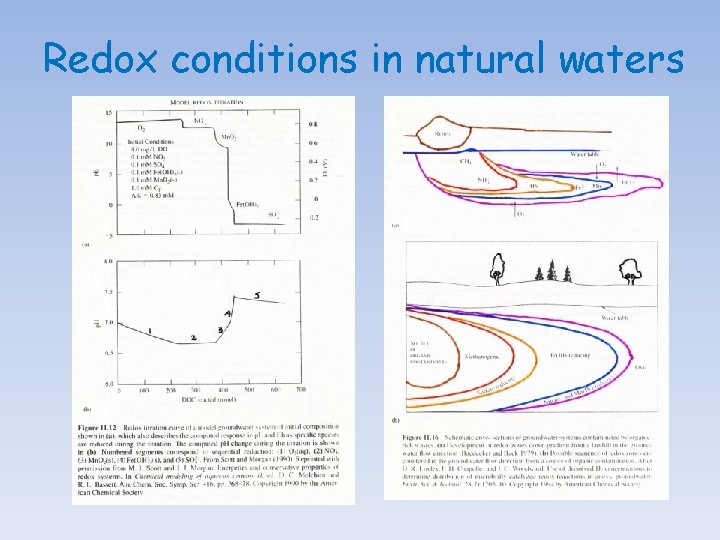

Redox conditions in natural waters

Redox conditions in natural waters

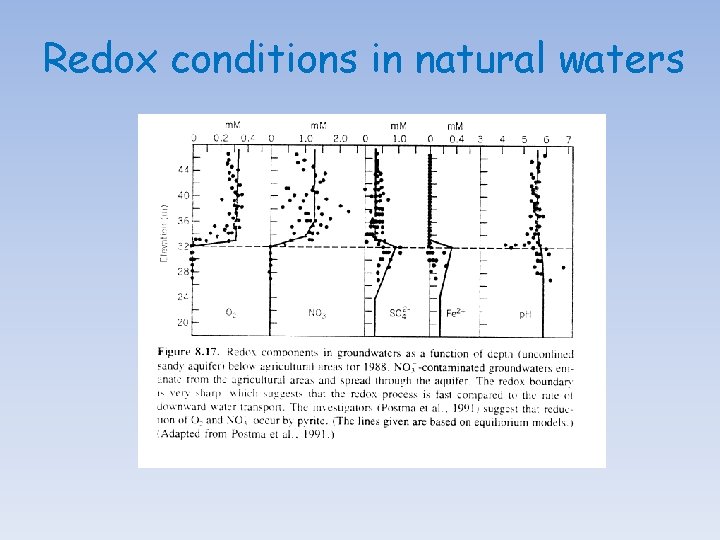

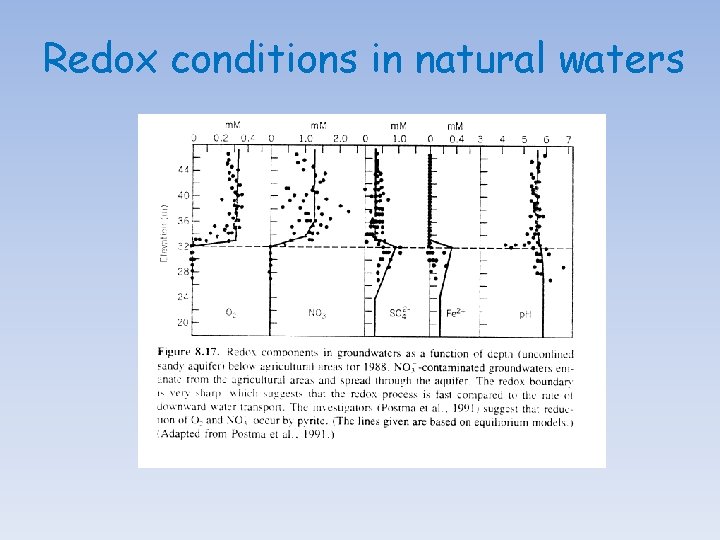

Redox conditions in natural waters

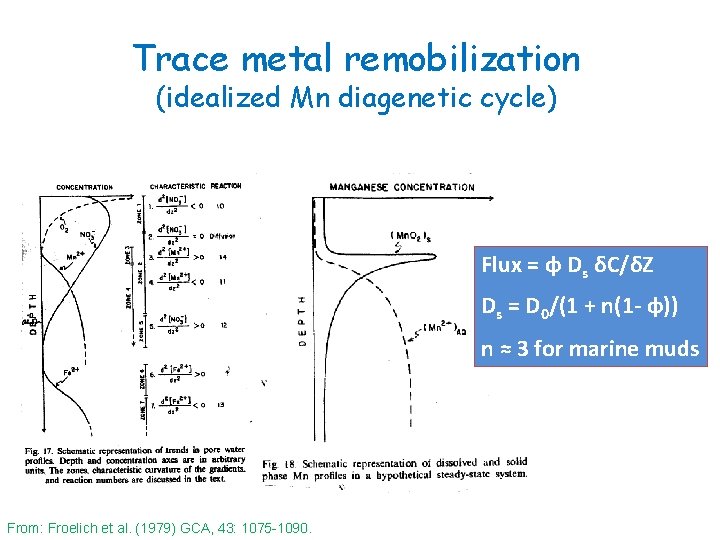

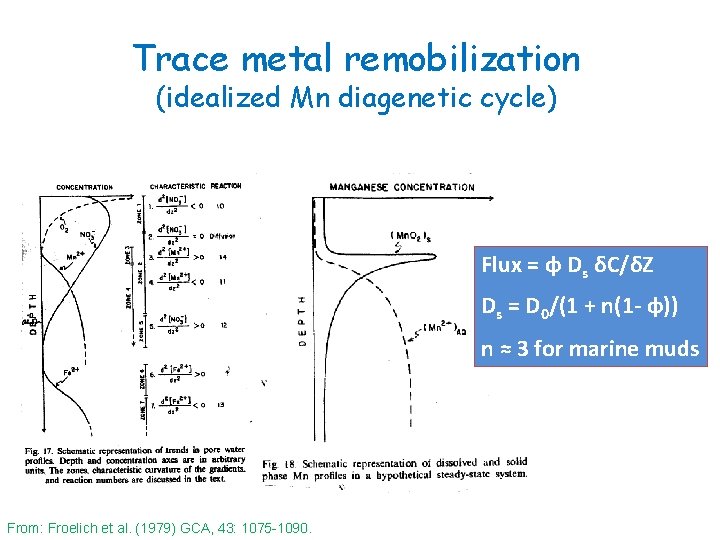

Trace metal remobilization (idealized Mn diagenetic cycle) Flux = φ Ds δC/δZ Ds = D 0/(1 + n(1 - φ)) n ≈ 3 for marine muds From: Froelich et al. (1979) GCA, 43: 1075 -1090.

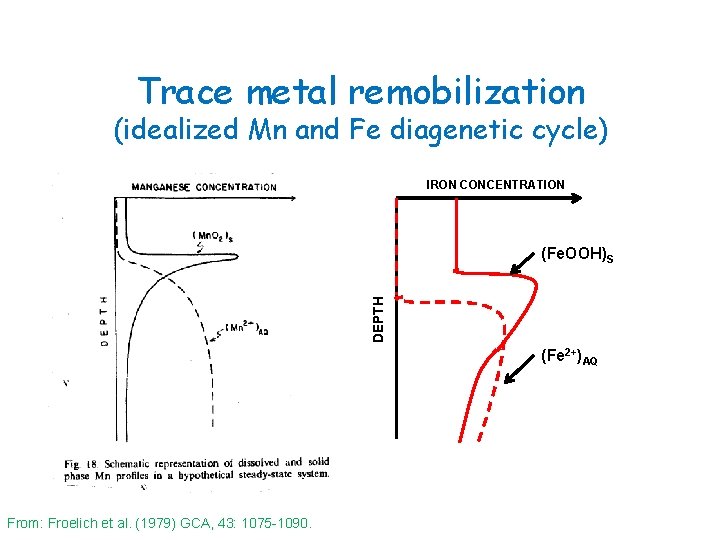

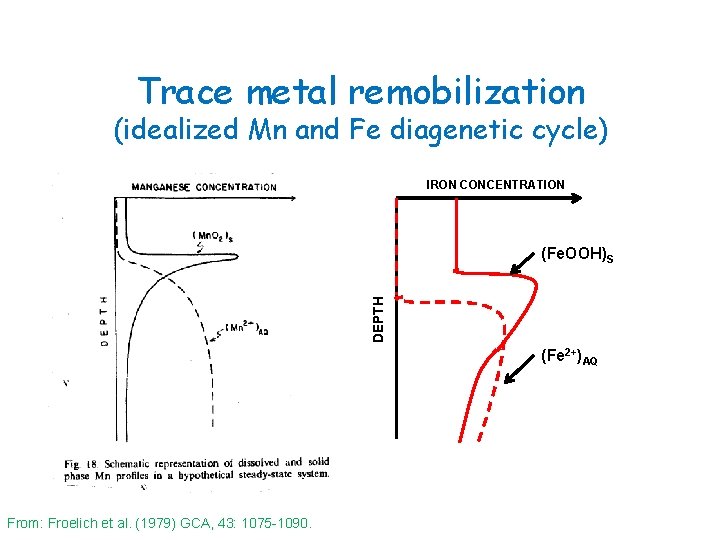

Trace metal remobilization (idealized Mn and Fe diagenetic cycle) IRON CONCENTRATION DEPTH (Fe. OOH)S (Fe 2+)AQ From: Froelich et al. (1979) GCA, 43: 1075 -1090.

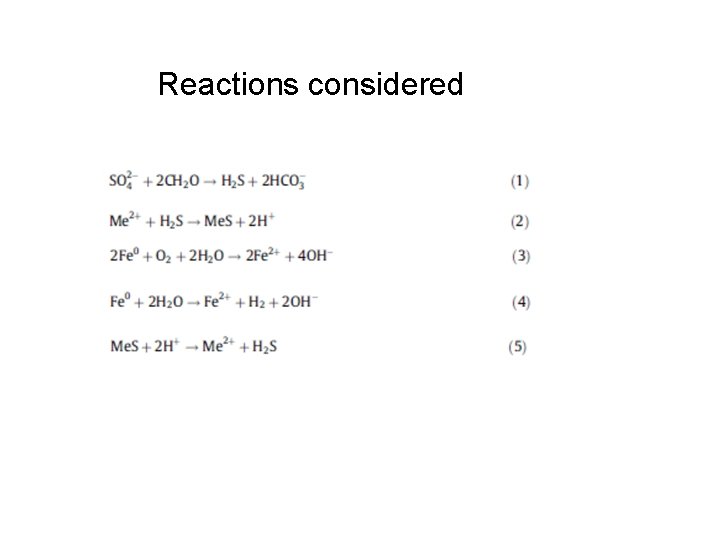

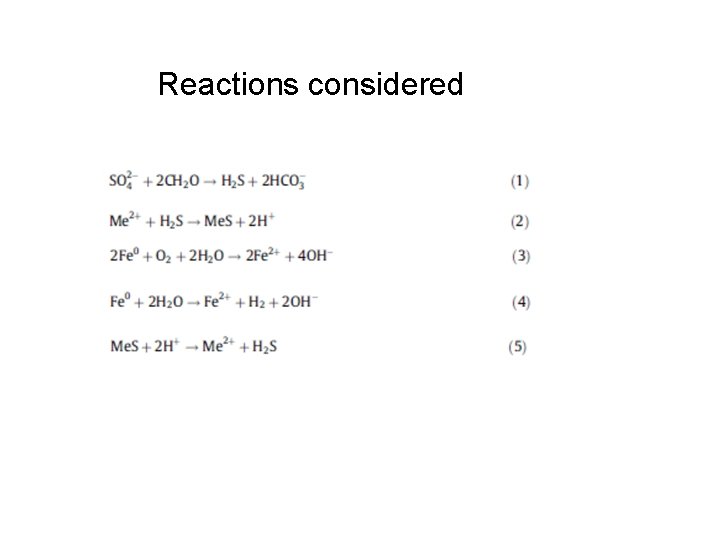

Reactions considered

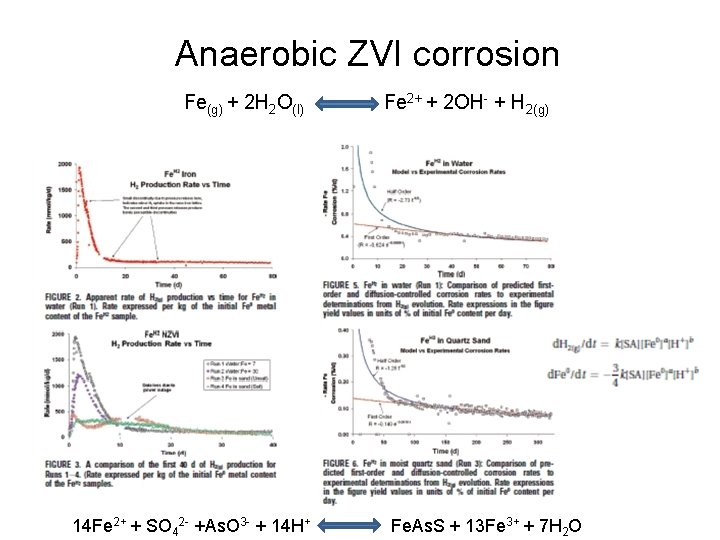

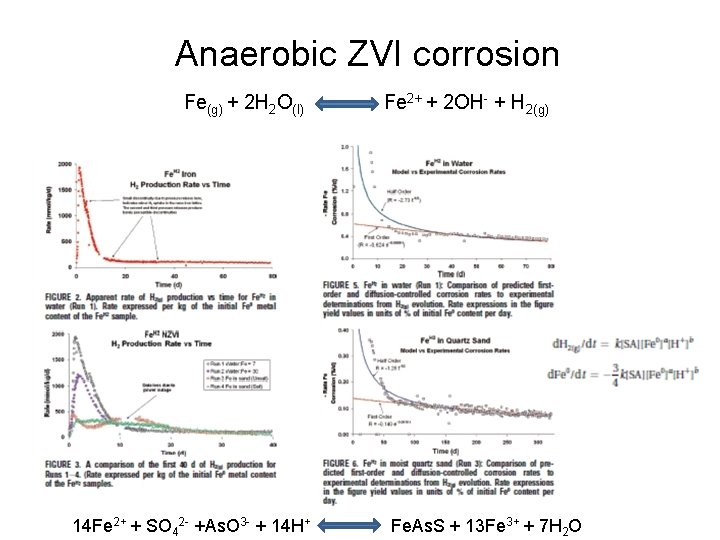

Anaerobic ZVI corrosion Fe(g) + 2 H 2 O(l) 14 Fe 2+ + SO 42 - +As. O 3 - + 14 H+ Fe 2+ + 2 OH- + H 2(g) Fe. As. S + 13 Fe 3+ + 7 H 2 O

Biochemistry • Methanogens are chemoautotrophs • Methanogens use a number of different ways to produce methane Using ethanoate (acetate) that may be derived from the decomposition of cellulose: CH 3 COO+ + H- CH 4 + CO 2 +36 k. J mol-1 Or using hydrogen and carbon dioxide produced by the decomposers: 4 H 2 + CO 2 CH 4 + 2 H 2 O +130. 4 k. J mol-1

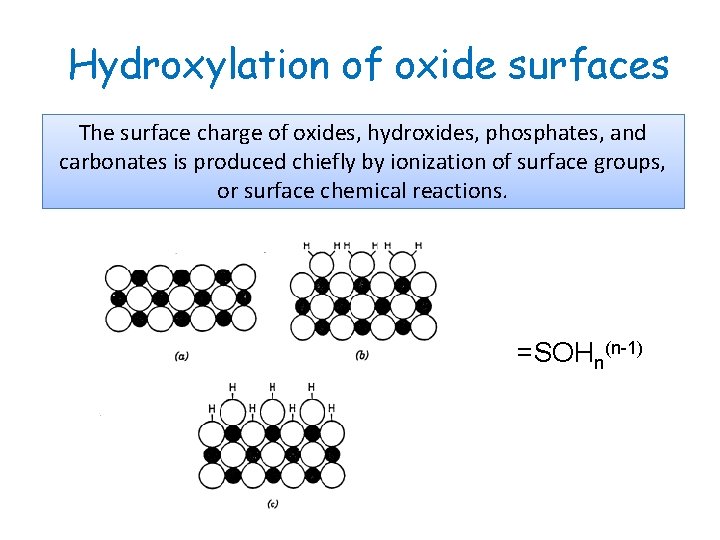

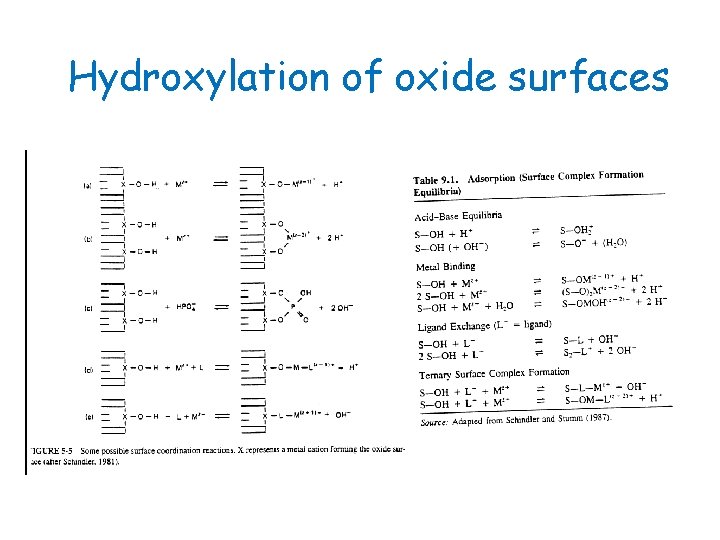

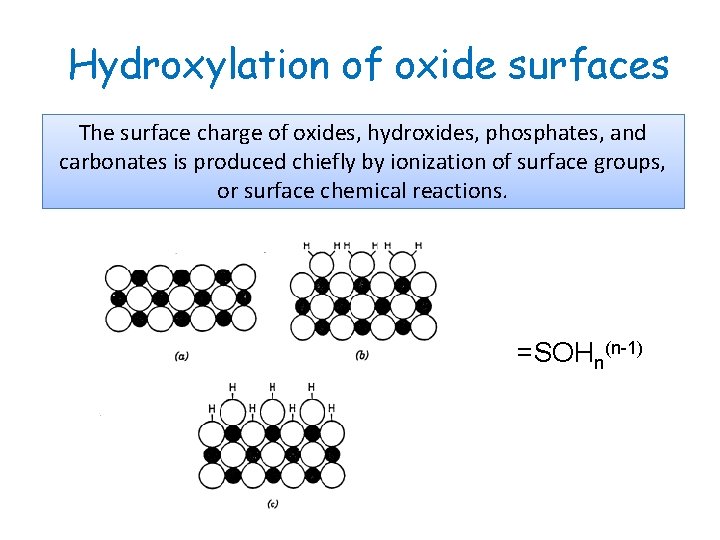

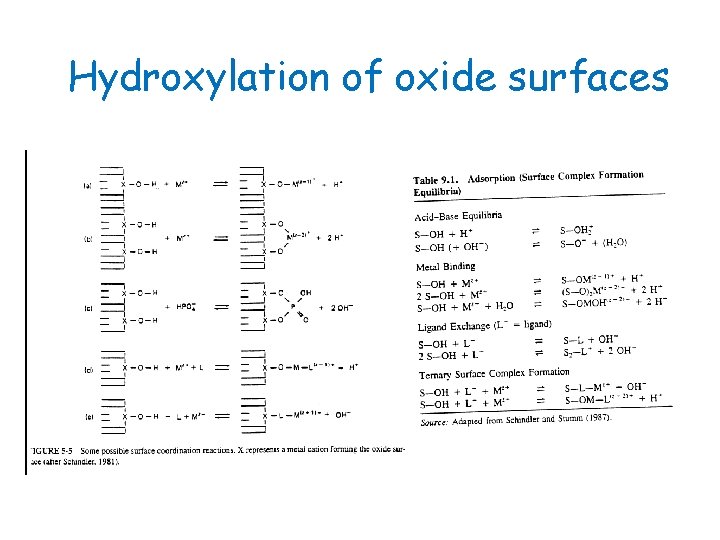

Hydroxylation of oxide surfaces The surface charge of oxides, hydroxides, phosphates, and carbonates is produced chiefly by ionization of surface groups, or surface chemical reactions. =SOHn(n-1)

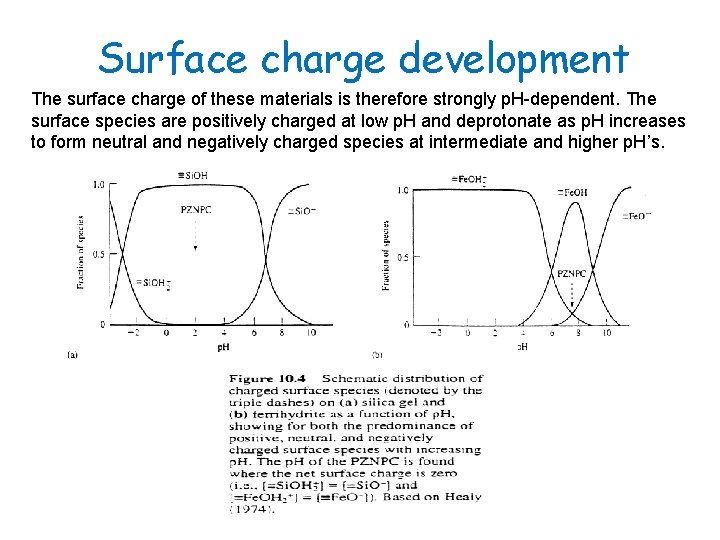

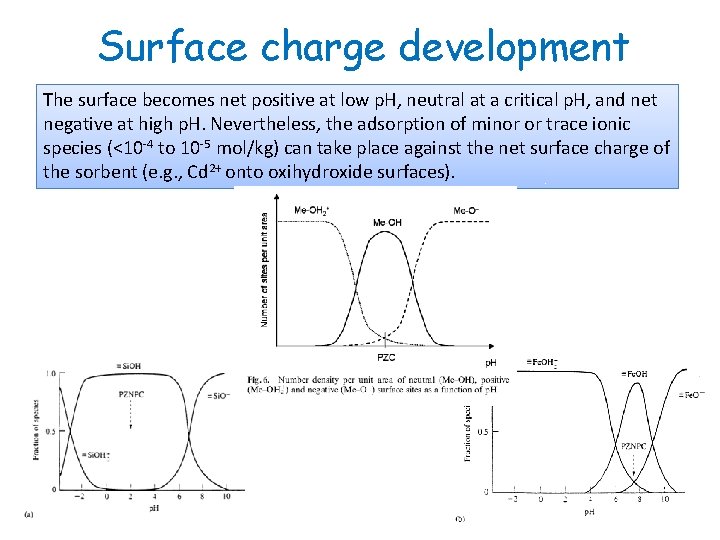

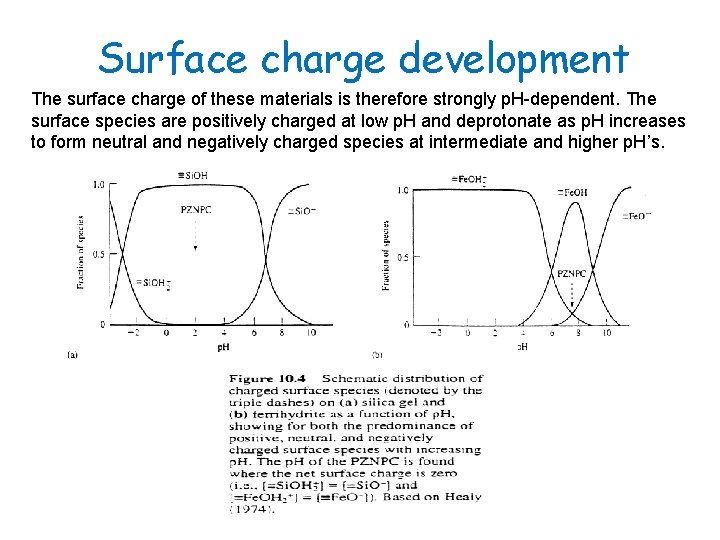

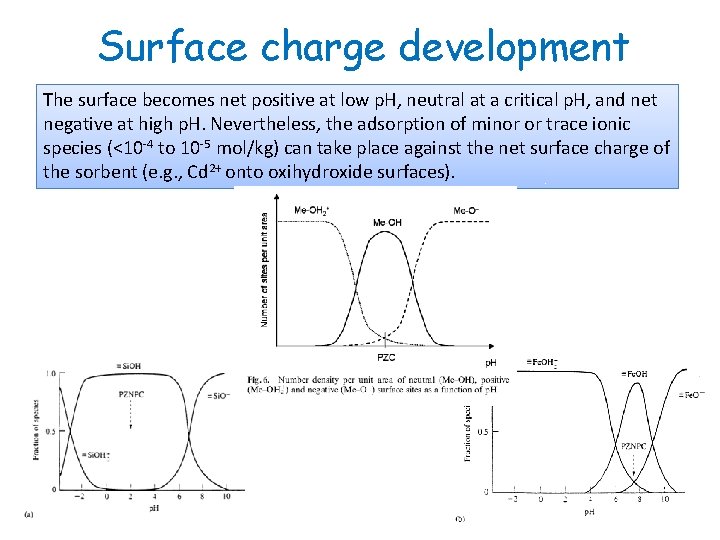

Surface charge development The surface charge of these materials is therefore strongly p. H-dependent. The surface species are positively charged at low p. H and deprotonate as p. H increases to form neutral and negatively charged species at intermediate and higher p. H’s.

Hydroxylation of oxide surfaces

Surface charge development The surface becomes net positive at low p. H, neutral at a critical p. H, and net negative at high p. H. Nevertheless, the adsorption of minor or trace ionic species (<10 -4 to 10 -5 mol/kg) can take place against the net surface charge of the sorbent (e. g. , Cd 2+ onto oxihydroxide surfaces).

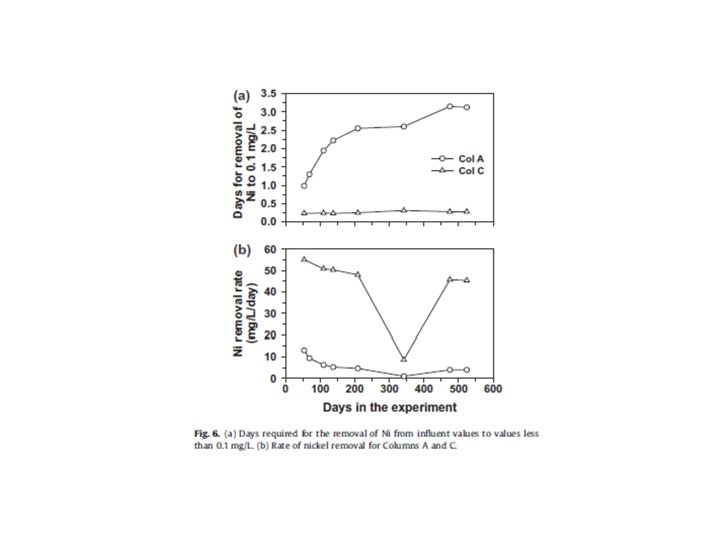

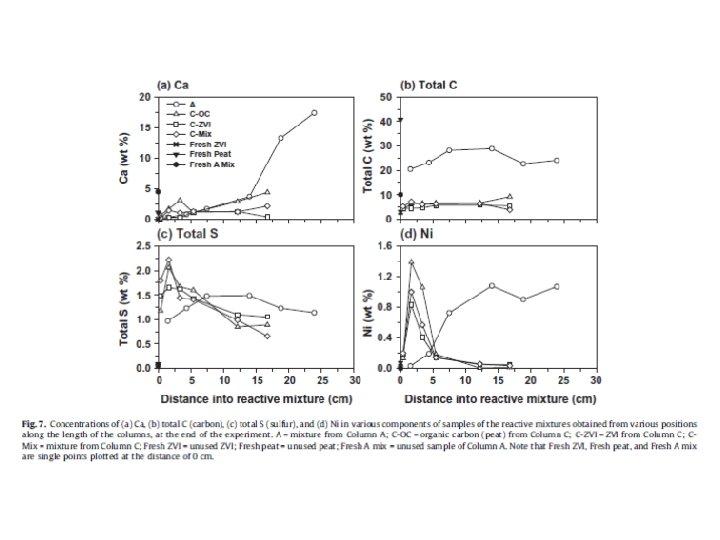

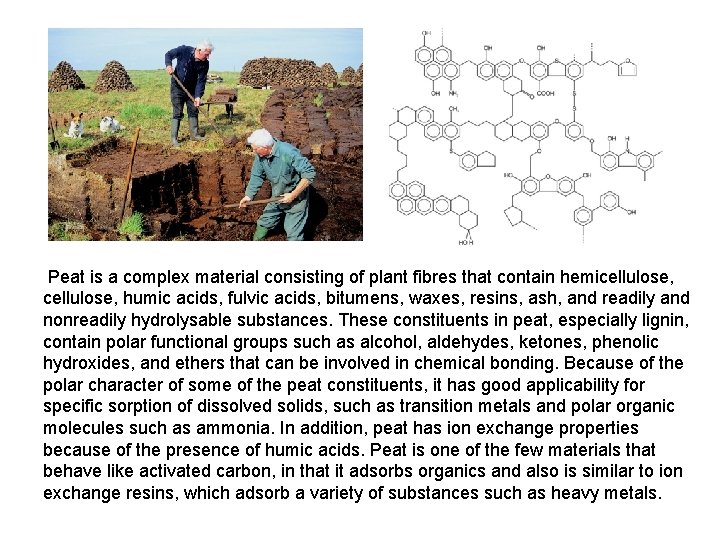

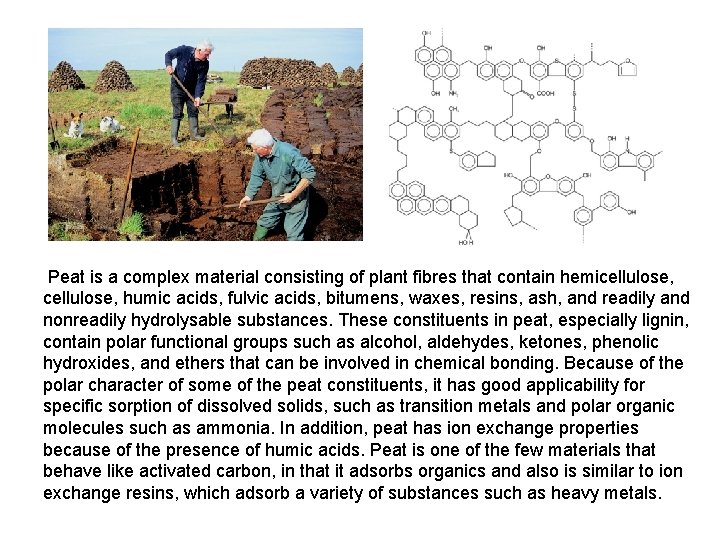

Peat is a complex material consisting of plant fibres that contain hemicellulose, humic acids, fulvic acids, bitumens, waxes, resins, ash, and readily and nonreadily hydrolysable substances. These constituents in peat, especially lignin, contain polar functional groups such as alcohol, aldehydes, ketones, phenolic hydroxides, and ethers that can be involved in chemical bonding. Because of the polar character of some of the peat constituents, it has good applicability for specific sorption of dissolved solids, such as transition metals and polar organic molecules such as ammonia. In addition, peat has ion exchange properties because of the presence of humic acids. Peat is one of the few materials that behave like activated carbon, in that it adsorbs organics and also is similar to ion exchange resins, which adsorb a variety of substances such as heavy metals.

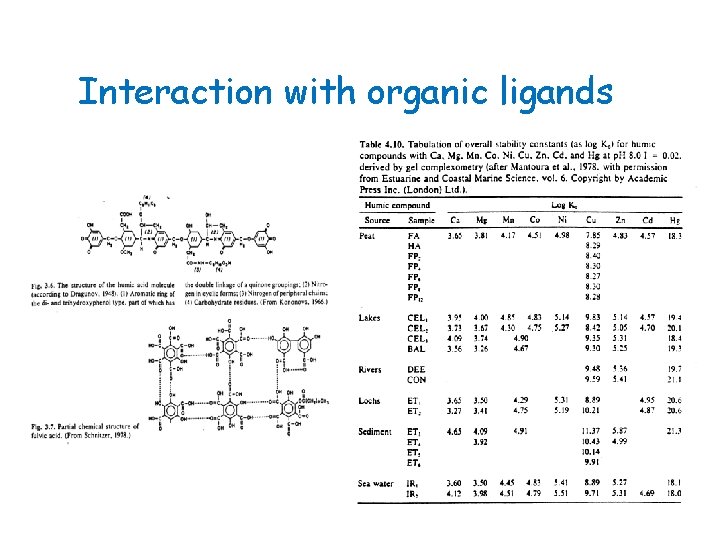

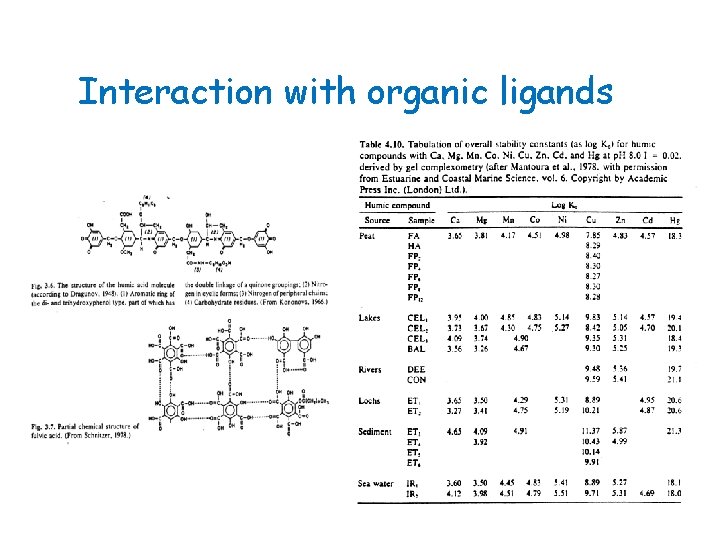

Interaction with organic ligands

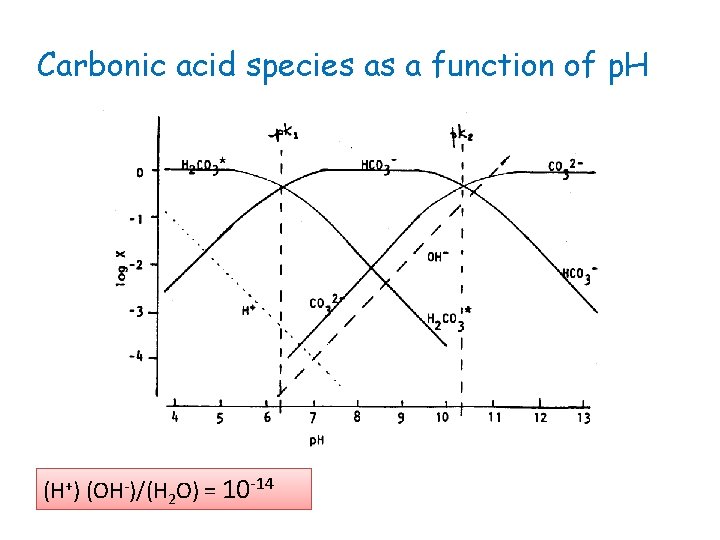

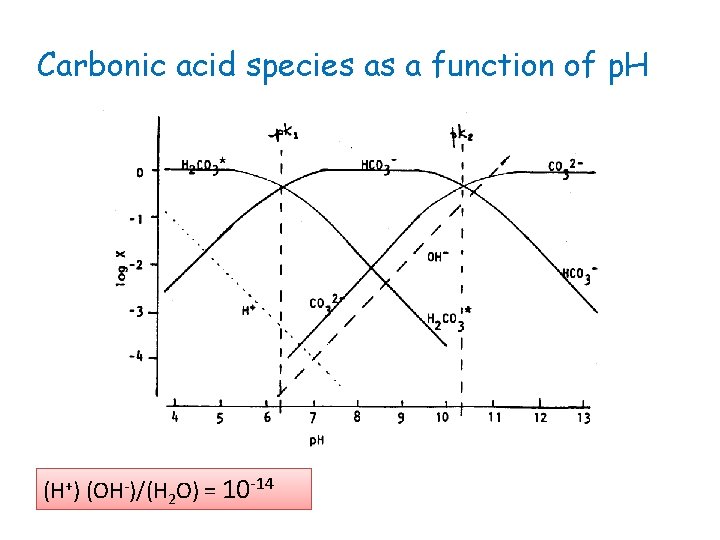

Carbonic acid species as a function of p. H (H+) (OH-)/(H 2 O) = 10 -14

![Carbonate chemistry Ksp Me 2 CO 32 CTH2K 1 K Carbonate chemistry Ksp = [Me 2+] [CO 32 - ] = CT/([H+]2/K 1 K](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5b6153e6c314585e79f3533e661cfcb9/image-40.jpg)

Carbonate chemistry Ksp = [Me 2+] [CO 32 - ] = CT/([H+]2/K 1 K 2 + [H+]/K 2 + 1) Ksp = [Me 2+] [CO 32 - ] [H 2 CO 3*] = K 0 p. CO 2 [CO 32 - ] = K 0 K 1 K 2 p. CO 2/[H+]2