Reconceptualising balancing measures in healthcare quality improvement and

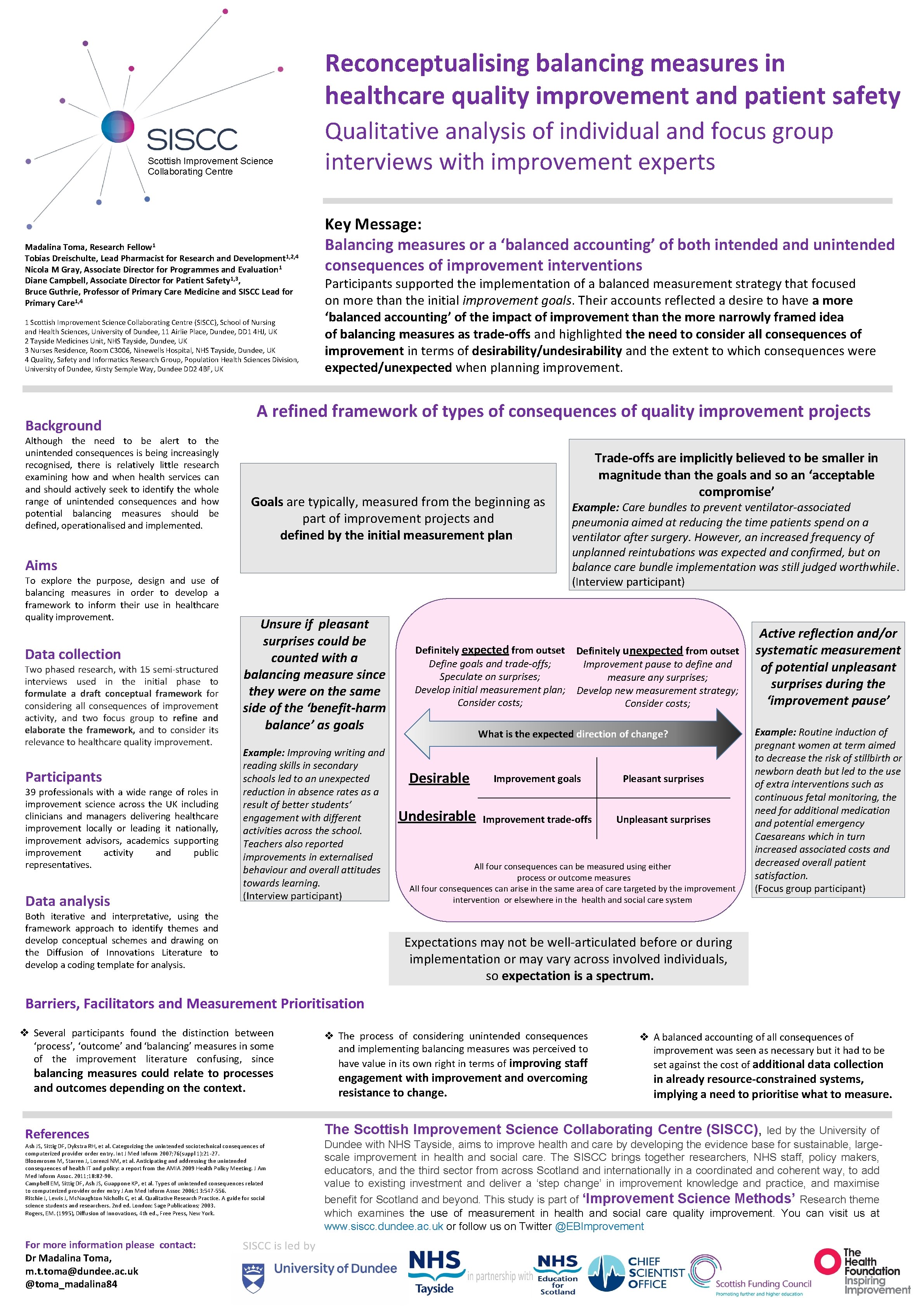

Reconceptualising balancing measures in healthcare quality improvement and patient safety Scottish Improvement Science Collaborating Centre Madalina Toma, Research Fellow 1 Tobias Dreischulte, Lead Pharmacist for Research and Development 1, 2, 4 Nicola M Gray, Associate Director for Programmes and Evaluation 1 Diane Campbell, Associate Director for Patient Safety 1, 3, Bruce Guthrie, Professor of Primary Care Medicine and SISCC Lead for Primary Care 1, 4 1 Scottish Improvement Science Collaborating Centre (SISCC), School of Nursing and Health Sciences, University of Dundee, 11 Airlie Place, Dundee, DD 1 4 HJ, UK 2 Tayside Medicines Unit, NHS Tayside, Dundee, UK 3 Nurses Residence, Room C 3006, Ninewells Hospital, NHS Tayside, Dundee, UK 4 Quality, Safety and Informatics Research Group, Population Health Sciences Division, University of Dundee, Kirsty Semple Way, Dundee DD 2 4 BF, UK Background Although the need to be alert to the unintended consequences is being increasingly recognised, there is relatively little research examining how and when health services can and should actively seek to identify the whole range of unintended consequences and how potential balancing measures should be defined, operationalised and implemented. Qualitative analysis of individual and focus group interviews with improvement experts Key Message: Balancing measures or a ‘balanced accounting’ of both intended and unintended consequences of improvement interventions Participants supported the implementation of a balanced measurement strategy that focused on more than the initial improvement goals. Their accounts reflected a desire to have a more ‘balanced accounting’ of the impact of improvement than the more narrowly framed idea of balancing measures as trade-offs and highlighted the need to consider all consequences of improvement in terms of desirability/undesirability and the extent to which consequences were expected/unexpected when planning improvement. A refined framework of types of consequences of quality improvement projects Goals are typically, measured from the beginning as part of improvement projects and defined by the initial measurement plan. Aims To explore the purpose, design and use of balancing measures in order to develop a framework to inform their use in healthcare quality improvement. Data collection Two phased research, with 15 semi-structured interviews used in the initial phase to formulate a draft conceptual framework for considering all consequences of improvement activity, and two focus group to refine and elaborate the framework, and to consider its relevance to healthcare quality improvement. Participants 39 professionals with a wide range of roles in improvement science across the UK including clinicians and managers delivering healthcare improvement locally or leading it nationally, improvement advisors, academics supporting improvement activity and public representatives. Data analysis Unsure if pleasant surprises could be counted with a balancing measure since they were on the same side of the ‘benefit-harm balance’ as goals Example: Improving writing and reading skills in secondary schools led to an unexpected reduction in absence rates as a result of better students’ engagement with different activities across the school. Teachers also reported improvements in externalised behaviour and overall attitudes towards learning. (Interview participant) Both iterative and interpretative, using the framework approach to identify themes and develop conceptual schemes and drawing on the Diffusion of Innovations Literature to develop a coding template for analysis. Trade-offs are implicitly believed to be smaller in magnitude than the goals and so an ‘acceptable compromise’ Example: Care bundles to preventilator-associated pneumonia aimed at reducing the time patients spend on a ventilator after surgery. However, an increased frequency of unplanned reintubations was expected and confirmed, but on balance care bundle implementation was still judged worthwhile. (Interview participant) Definitely expected from outset Definitely unexpected from outset Define goals and trade-offs; Improvement pause to define and Speculate on surprises; measure any surprises; Develop initial measurement plan; Develop new measurement strategy; Consider costs; What is the expected direction of change? Desirable Improvement goals Pleasant surprises Undesirable Improvement trade-offs Unpleasant surprises All four consequences can be measured using either process or outcome measures All four consequences can arise in the same area of care targeted by the improvement intervention or elsewhere in the health and social care system Active reflection and/or systematic measurement of potential unpleasant surprises during the ‘improvement pause’ Example: Routine induction of pregnant women at term aimed to decrease the risk of stillbirth or newborn death but led to the use of extra interventions such as continuous fetal monitoring, the need for additional medication and potential emergency Caesareans which in turn increased associated costs and decreased overall patient satisfaction. (Focus group participant) Expectations may not be well-articulated before or during implementation or may vary across involved individuals, so expectation is a spectrum. Barriers, Facilitators and Measurement Prioritisation v Several participants found the distinction between ‘process’, ‘outcome’ and ‘balancing’ measures in some of the improvement literature confusing, since balancing measures could relate to processes and outcomes depending on the context. References Ash JS, Sittig DF, Dykstra RH, et al. Categorizing the unintended sociotechnical consequences of computerized provider order entry. Int J Med Inform 2007; 76(suppl 1): 21 -27. Bloomrosen M, Starren J, Lorenzi NM, et al. Anticipating and addressing the unintended consequences of health IT and policy: a report from the AMIA 2009 Health Policy Meeting. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011; 18: 82 -90. Campbell EM, Sittig DF, Ash JS, Guappone KP, et al. Types of unintended consequences related to computerized provider order entry J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006; 13: 547 -556. Ritchie J, Lewis J, Mc. Naughton Nicholls C, et al. Qualitative Research Practice. A guide for social science students and researchers. 2 nd ed. London: Sage Publications; 2003. Rogers, EM. (1995), Diffusion of Innovations, 4 th ed. , Free Press, New York. For more information please contact: Dr Madalina Toma, m. t. toma@dundee. ac. uk @toma_madalina 84 v The process of considering unintended consequences and implementing balancing measures was perceived to have value in its own right in terms of improving staff engagement with improvement and overcoming resistance to change. v A balanced accounting of all consequences of improvement was seen as necessary but it had to be set against the cost of additional data collection in already resource-constrained systems, implying a need to prioritise what to measure. The Scottish Improvement Science Collaborating Centre (SISCC), led by the University of Dundee with NHS Tayside, aims to improve health and care by developing the evidence base for sustainable, largescale improvement in health and social care. The SISCC brings together researchers, NHS staff, policy makers, educators, and the third sector from across Scotland internationally in a coordinated and coherent way, to add value to existing investment and deliver a ‘step change’ in improvement knowledge and practice, and maximise benefit for Scotland beyond. This study is part of ‘Improvement Science Methods’ Research theme which examines the use of measurement in health and social care quality improvement. You can visit us at www. siscc. dundee. ac. uk or follow us on Twitter @EBImprovement

- Slides: 1