RECIPROCAL SOCIAL ENGAGEMENT A MODEL FOR ENGAGING WITH

- Slides: 9

RECIPROCAL SOCIAL ENGAGEMENT A MODEL FOR ENGAGING WITH MARGINALISED YOUNG MALES

CONTEXT OF DEVELOPING THIS MODEL • 20 years accumulated experience in social work practice • 20 years in academic research • Primary focus on how male health & wellbeing develops through community engagement • Busting myths about male communication and participation

RECIPROCAL ENGAGEMENT • Term’s origins are in neurological science – how nerve endings connect and communicate • Term has been borrowed, translated and reinterpreted into a number of different settings, each with different meanings: • Pedagogical/university • Organisational psychology • Genetic counselling

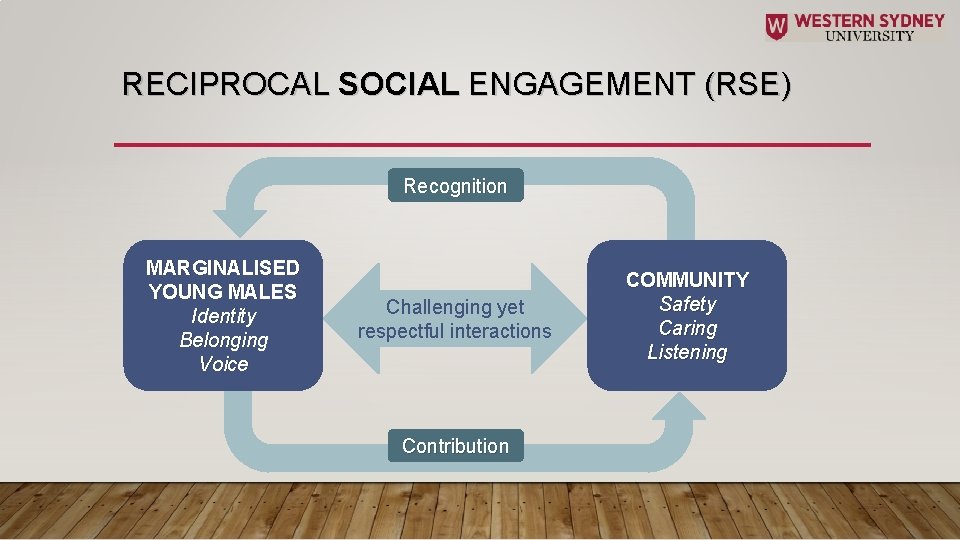

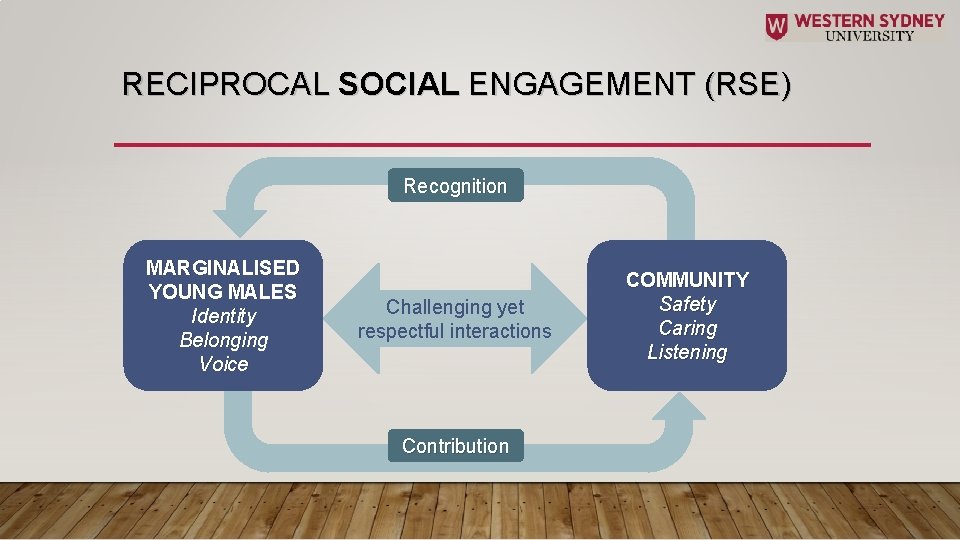

RECIPROCAL SOCIAL ENGAGEMENT (RSE) Recognition MARGINALISED YOUNG MALES Identity Belonging Voice Challenging yet respectful interactions Contribution COMMUNITY Safety Caring Listening

RECIPROCAL SOCIAL ENGAGEMENT (RSE) • Acknowledges that ‘connectedness’ with community (belonging, supportive networks) is a social determinant of health (Wilkinson & Marmot 2003), the RSE perspective broadens connectedness to recognise a process of two-way influence between people on the margins of society and the general community. • Contextualises into community the more individualised notion of the ‘social contract’ (Flanagan et al 1999) & expands on Bolzan & Gale’s (2011) articulation of ‘social resilience’. • Collaboratively working with people on the margins to be empowered, develop a voice and communicate articulately and respectfully. Simultaneously working collaboratively with general community members, human service agencies and policy makers to develop capacity for hearing their voice and responding respectfully. • The interaction between marginalised and general community members is one in which each party both provokes and influences; speaks and listens, contributes and recognises contribution to community in the other, with the potential to contribute overall to individual and whole community wellbeing through the process.

EXAMPLE 1: RUGBY YOUTH LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT PROJECT • Working class young males – disenchanted with “win at all costs” culture of local rugby league and football (soccer) clubs – turned to a rugby union club that was more about participation and enjoyment • Feeling that playing sport increased their sense of belonging to community and was also their way of contributing to community • Further enhanced by their organising of community events featuring former and emerging Wallabies • Enjoyed community recognition of that contribution – e. g. local media attention, being recognised in local shops, acknowledgement of project by NSWRU, pilot project received funding • Able to engage in informed discussion about the positives and negatives of sport

EXAMPLE 2: STREET ART WALK • Zoning permission to turn a laneway into a street art gallery • Local young males working alongside nationally and internationally known artists • Expression of artistic voice as contribution to community • Embedded QR codes enabled community members to see bios and back-stories • Website, social media, Trip Advisor, enabled feedback from community: • overwhelmingly positive but also enabled respectful disagreement • Project won a national award for local government collaboration

REFERENCES • Bolzan N & Gale F. (2011). ‘Using an interrupted space to explore social resilience with marginalized young people’. Qualitative Social Work, 11(5) 502– 516. • Flanagan C, Jonsson B, Botcheva L, Csapo B, Bowes J, Macek P, Averina I & Sheblanove E, ‘Adolescents and the “social contract”: developmental roots of citizenship in seven countries’. In Yates M and Youniss J (eds). (1999). Roots of civic identity: International perspectives on community service and activism in youth. Cambridge, U. K. : Cambridge University Press. • Wilkinson RG & Marmot MG. (2003). Social determinants of health: the solid facts, 2 nd ed. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

CONTACT Dr Neil Hall School of Social Sciences and Psychology Western Sydney University, Parramatta. Australia Ph: +612 9685 9448 Mob: +612 417 278 645 n. hall@westernsydney. edu. au