RECEPTORS Lecture 4 Topics Cell surface receptors Chemical

- Slides: 15

RECEPTORS Lecture 4

Topics � Cell surface receptors. � Chemical gated ion channels. � Enzymatic. Tyrosine kinases. � G-coupled

Receptor The role of detection of signals arriving from outside of the cell is usually fulfilled by the presence of specific receptors, either on the cell surface or inside the cell (either in the cytoplasm or in the nucleus).

Criteria for a receptor � � A receptor has to have specificity, specificity detecting only the signaling molecule (or range of molecules) that the cell wishes to perceive. The binding affinity of the receptor must be such that it can detect the signaling molecule at the concentrations at which it is likely to be found in the vicinity of the cell. The receptor must be able to transmit the message that the signaling molecule conveys to the cell, usually by the modulation of further components in a signaling cascade. Usually the receptor needs to be able to be turned off again once the “message” is received and acted on.

Cell surface receptors � � Most signal molecules are water-soluble, including neurotransmitters, peptide hormones, and the many proteins that multicellular organisms employ as “growth factors” during development. Water-soluble signals cannot diffuse through cell membranes. Therefore, to trigger responses in cells, they must bind to receptor proteins on the surface of the cell. These cell surface receptors convert the extracellular signal to an intracellular one, responding to the binding of the signal molecule by producing a change within the cell’s cytoplasm.

Cell surface receptors � Most of a cell’s receptors are cell surface receptors, and almost all of them belong to one of three receptor super families: chemically gated ion channels, enzymatic receptors, and Gprotein-linked receptors.

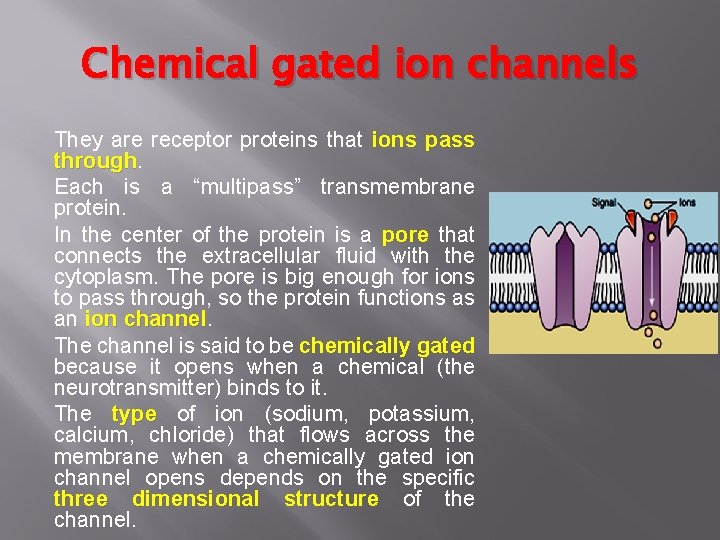

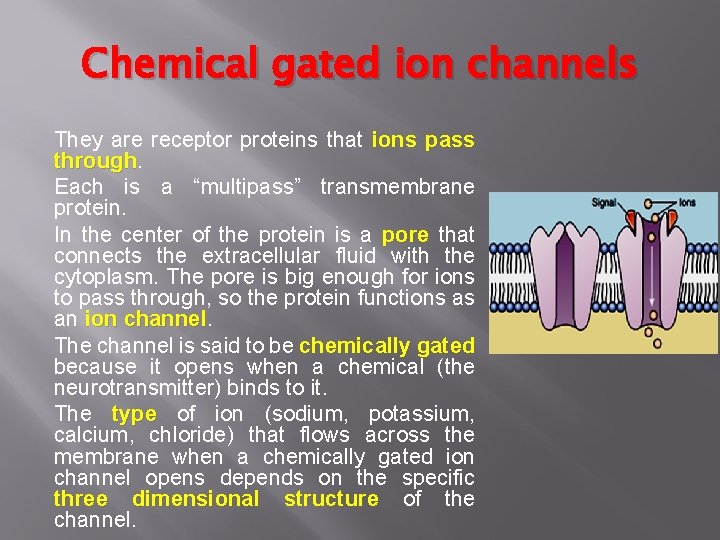

Chemical gated ion channels They are receptor proteins that ions pass through Each is a “multipass” transmembrane protein. In the center of the protein is a pore that connects the extracellular fluid with the cytoplasm. The pore is big enough for ions to pass through, so the protein functions as an ion channel The channel is said to be chemically gated because it opens when a chemical (the neurotransmitter) binds to it. The type of ion (sodium, potassium, calcium, chloride) that flows across the membrane when a chemically gated ion channel opens depends on the specific three dimensional structure of the channel.

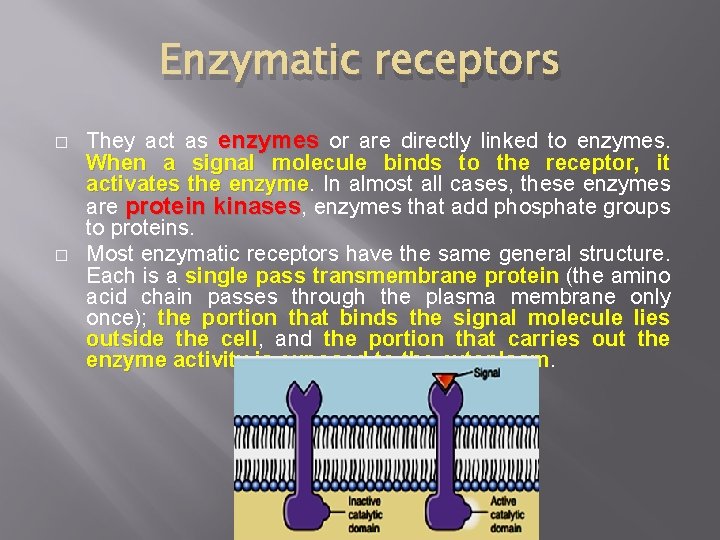

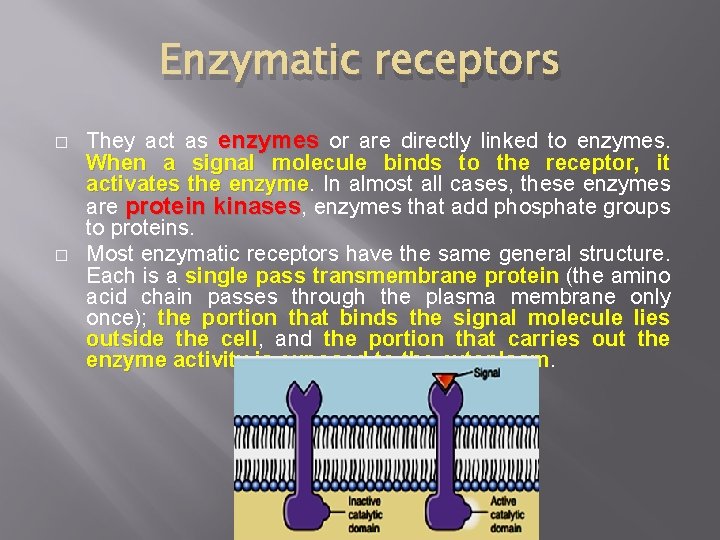

Enzymatic receptors � � They act as enzymes or are directly linked to enzymes. When a signal molecule binds to the receptor, it activates the enzyme In almost all cases, these enzymes are protein kinases, enzymes that add phosphate groups to proteins. Most enzymatic receptors have the same general structure. Each is a single pass transmembrane protein (the amino acid chain passes through the plasma membrane only once); the portion that binds the signal molecule lies outside the cell, cell and the portion that carries out the enzyme activity is exposed to the cytoplasm

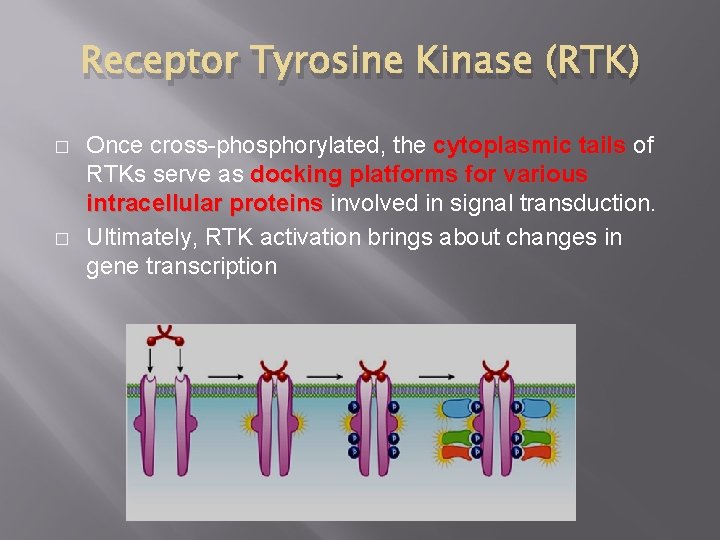

Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (RTK) � RTKs are cell surface receptors bind and respond to growth factors and other locally released proteins that are present at low concentrations RTKs play important roles in the regulation of cell growth, differentiation, and survival. � When signaling molecules bind to RTKs, they cause neighboring RTKs to associate with each other, other forming cross-linked dimers Cross-linking activates the tyrosine kinase activity in these RTKs through phosphorylation Each RTK in the dimer phosphorylates multiple tyrosines on the other RTK. This process is called crossphorylation. phosphorylation � �

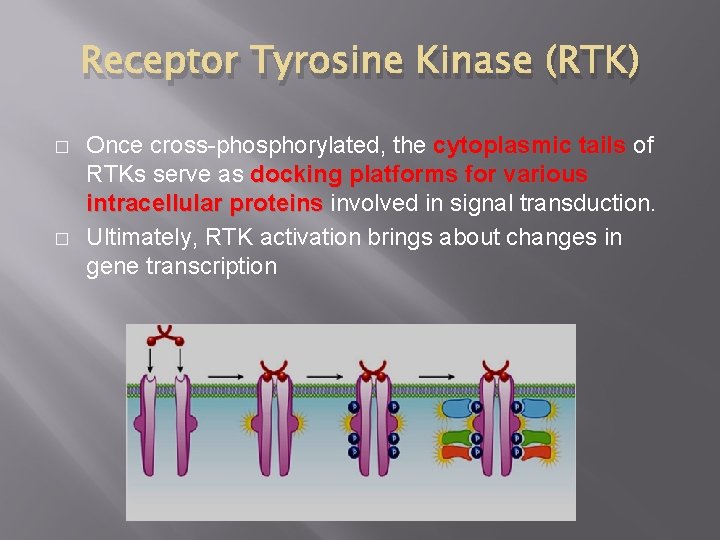

Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (RTK) � � Once cross-phosphorylated, the cytoplasmic tails of RTKs serve as docking platforms for various intracellular proteins involved in signal transduction. Ultimately, RTK activation brings about changes in gene transcription

G-Protein-Coupled Receptors � � G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are the largest and most diverse group of membrane receptors in eukaryotes. one-third to one-half of all marketed drugs act by binding to GPCRs bind a tremendous variety of signaling molecules, yet they share a common architecture that has been conserved over the course of evolution. GPCRs are involved in considerably more functions in multicellular organisms. Humans alone have nearly 1, 000 different GPCRs, and each one is highly specific to a particular signal.

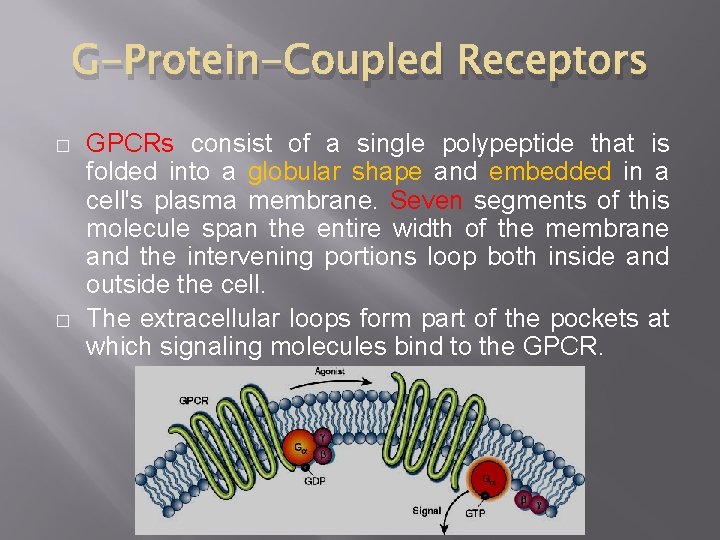

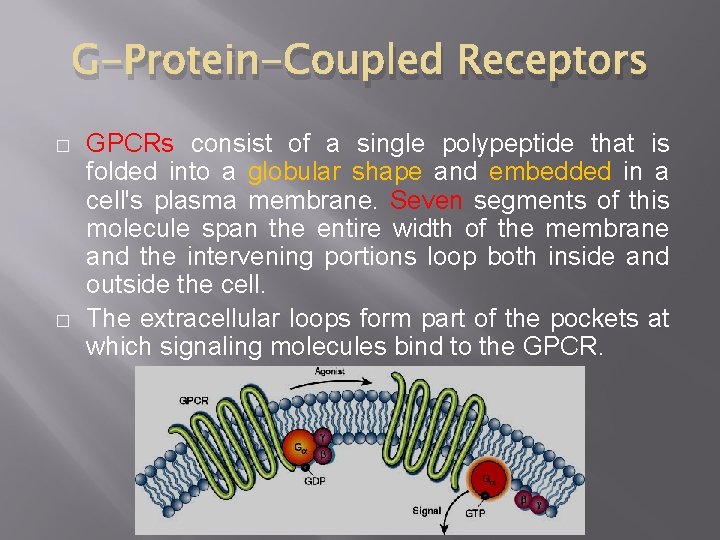

G-Protein-Coupled Receptors � � GPCRs consist of a single polypeptide that is folded into a globular shape and embedded in a cell's plasma membrane. Seven segments of this molecule span the entire width of the membrane and the intervening portions loop both inside and outside the cell. The extracellular loops form part of the pockets at which signaling molecules bind to the GPCR.

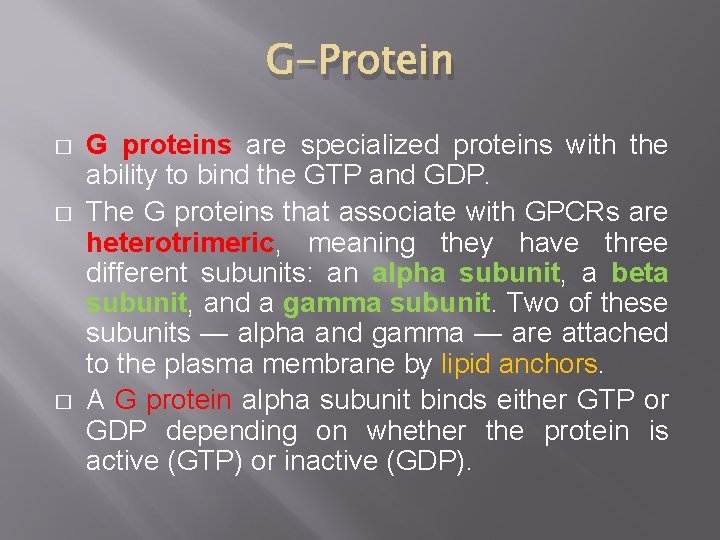

G-Protein � � � G proteins are specialized proteins with the ability to bind the GTP and GDP. The G proteins that associate with GPCRs are heterotrimeric, meaning they have three different subunits: an alpha subunit, a beta subunit, and a gamma subunit. Two of these subunits — alpha and gamma — are attached to the plasma membrane by lipid anchors. A G protein alpha subunit binds either GTP or GDP depending on whether the protein is active (GTP) or inactive (GDP).

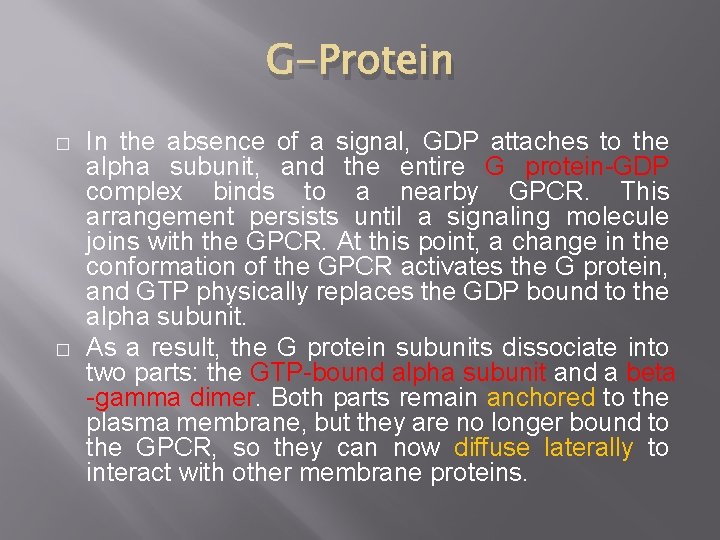

G-Protein � � In the absence of a signal, GDP attaches to the alpha subunit, and the entire G protein-GDP complex binds to a nearby GPCR. This arrangement persists until a signaling molecule joins with the GPCR. At this point, a change in the conformation of the GPCR activates the G protein, and GTP physically replaces the GDP bound to the alpha subunit. As a result, the G protein subunits dissociate into two parts: the GTP-bound alpha subunit and a beta -gamma dimer. Both parts remain anchored to the plasma membrane, but they are no longer bound to the GPCR, so they can now diffuse laterally to interact with other membrane proteins.

G-Protein � � G proteins remain active as long as their alpha subunits are joined with GTP. However, when this GTP is hydrolyzed back to GDP, the subunits once again assume the form of an inactive heterotrimeric, and the entire G protein re-associates with the now-inactive GPCR. In this way, G proteins work like a switch — turned on or off by signal-receptor interactions on the cell's surface.