RealTime Scheduling for Multiprocessor Platforms Marko Bertogna Scuola

Real-Time Scheduling for Multiprocessor Platforms Marko Bertogna Scuola Superiore S. Anna, Pisa, Italy

Outline n n n n Why do we need multiprocessor RTS? Why are multiprocessors difficult? Global vs partitioned scheduling Existing scheduling algorithms Schedulability results Evaluation of existing techniques Future research

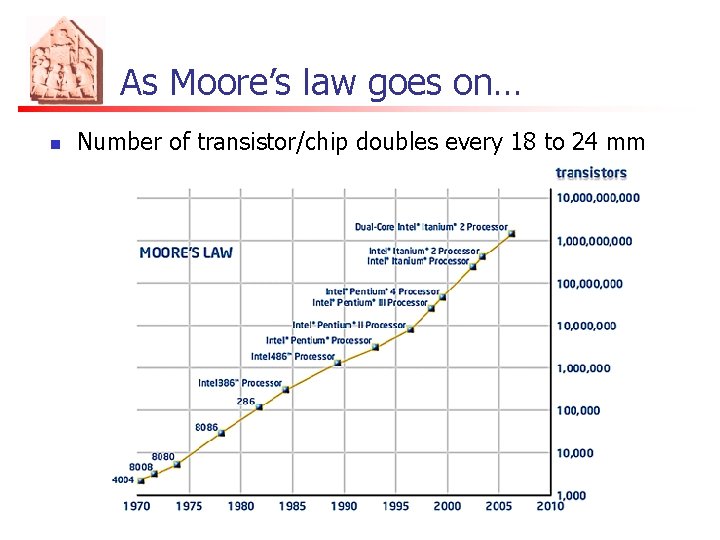

As Moore’s law goes on… n Number of transistor/chip doubles every 18 to 24 mm

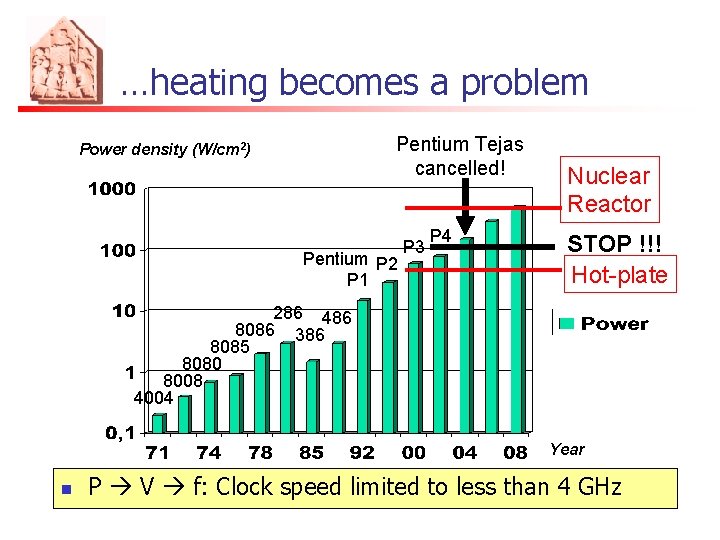

…heating becomes a problem Pentium Tejas cancelled! Power density (W/cm 2) Pentium P 2 P 1 P 3 P 4 Nuclear Reactor STOP !!! Hot-plate 286 486 8086 386 8085 8080 8008 4004 Year n P V f: Clock speed limited to less than 4 GHz

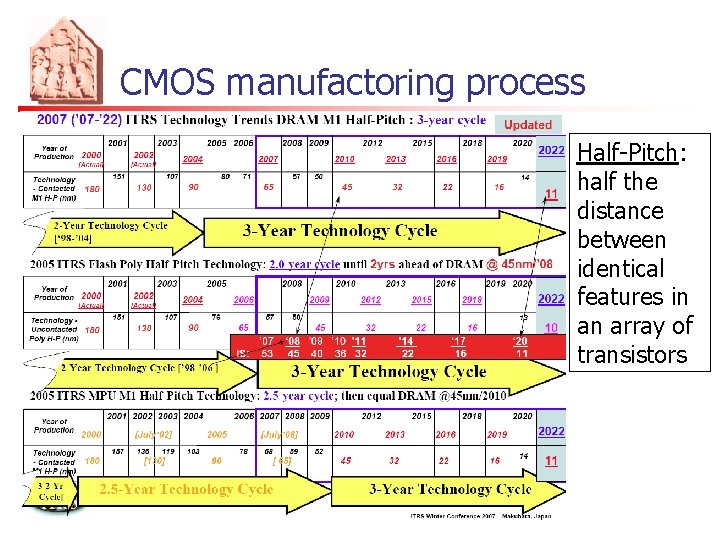

Why did it happen? Integration technology constantly improves…

CMOS manufactoring process Half-Pitch: half the distance between identical features in an array of transistors

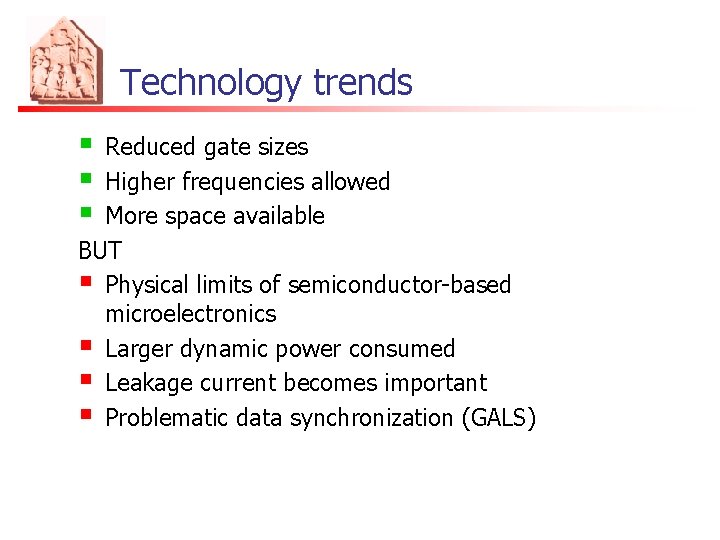

Technology trends § § § Reduced gate sizes Higher frequencies allowed More space available BUT § Physical limits of semiconductor-based microelectronics § Larger dynamic power consumed § Leakage current becomes important § Problematic data synchronization (GALS)

Frequency Lead Microprocessors frequency doubled every 2 years Frequency (Mhz) 10000 100 10 8085 1 0. 1 1970 Courtesy, Intel 8086 286 386 486 P 6 Pentium ® proc 8080 8008 4004 1980 1990 Year 2000 2010

Intel’s timeline

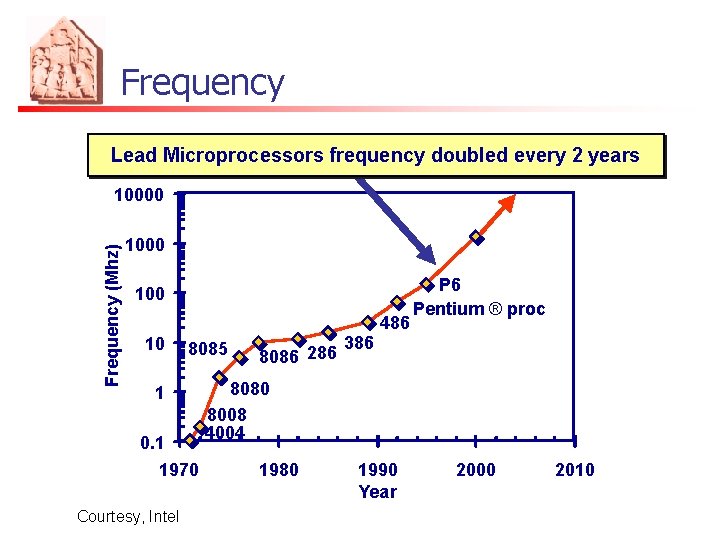

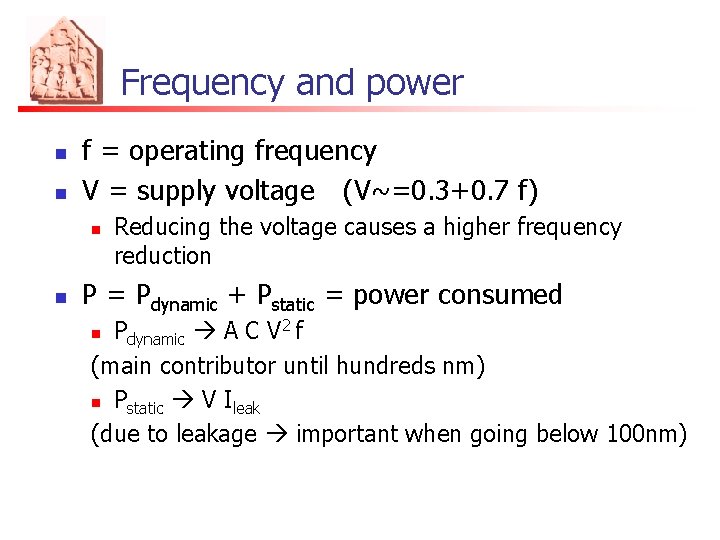

Frequency and power n n f = operating frequency V = supply voltage (V~=0. 3+0. 7 f) n n Reducing the voltage causes a higher frequency reduction P = Pdynamic + Pstatic = power consumed Pdynamic A C V 2 f (main contributor until hundreds nm) n Pstatic V Ileak (due to leakage important when going below 100 nm) n

Design considerations (I) P = A C V 2 f + V Ileak n n n Number of transistors grows A grows Die size grows C grows Reducing V would allow a quadratic reduction on dynamic power But clock frequency would decrease more than linearly since V~=0. 3+0. 7 f unless Vth as well is reduced But, again, there are problems: Ileak Isub + Igox increases when Vth is low!

Design considerations (II) P = A C V 2 f + V Ileak n n n Reducing Vth and gate dimensions leakage current becomes dominant in recent process technologies static dissipation Static power dissipation is always present unless losing device state Summarizing: There is no way out for classic frequency scaling on single cores systems!

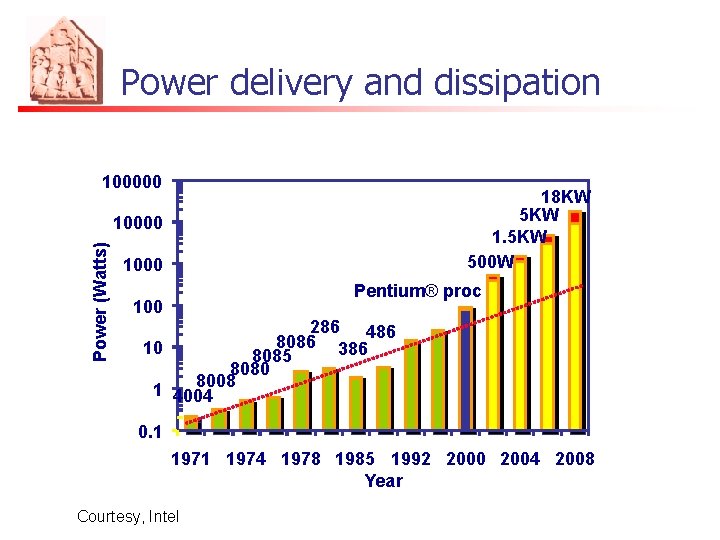

Power delivery and dissipation 100000 18 KW 5 KW 1. 5 KW 500 W Power (Watts) 10000 1000 Pentium® proc 100 286 486 8086 10 386 8085 8080 8008 1 4004 0. 1 1974 1978 1985 1992 2000 2004 2008 Year Courtesy, Intel

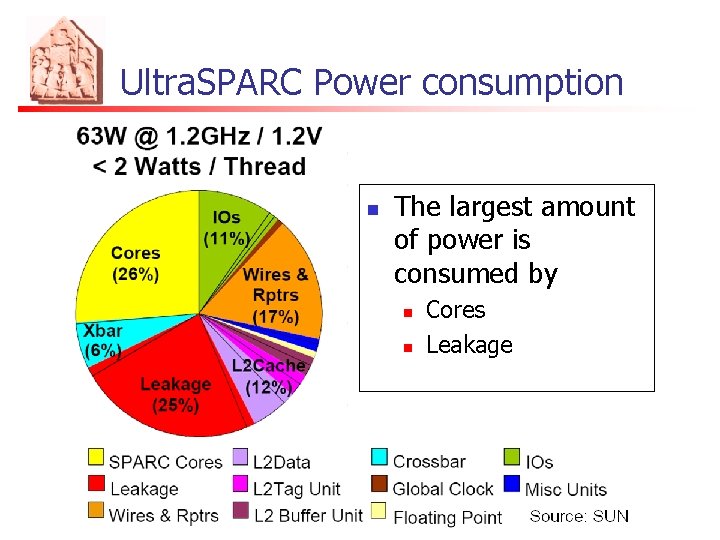

Ultra. SPARC Power consumption n The largest amount of power is consumed by n n Cores Leakage

Keeping Moore’s law alive n n Exploit the immense number of transistors in other ways Reduce gate sizes maintaining the frequency sufficiently low Use a higher number of slower logic gates In other words: Switch to Multicore Systems!

Solution Denser chips with transistors operating at lower frequencies MULTICORE SYSTEMS

What is this? n 1979 - David May’s B 0042 board - 42 Transputers

The multicore invasion (high-end) n n n n Intel’s Core 2, Itanium, Xeon: 2, 4 cores AMD’s Opteron, Athlon 64 X 2, Phenom: 2, 4 cores IBM’s POWER 7: 8 cores IBM-Toshiba-Sony Cell processor: 8 cores (PSX 3) Sun’s Niagara Ultra. SPARC: 8 cores Microsoft’s Xenon: 3 cores (Xbox 360) Tilera’s TILE 64: 64 -core Others (network processors, DSP, GPU, …)

The multicore invasion (embedded) n n ARM’s MPCore: 4 cores ALTERA’s Nios II: x Cores Network Processors are being replaced by multicore chips (Broadcom’s 8 -core processors) DSP: TI, Freescale, Atmel, Picochip (up to 300 cores, communication domain)

How many cores in the future? n n n Application dependent Typically few for high-end computing Many trade-offs n n n transistor density technology limits Amdahl’s law

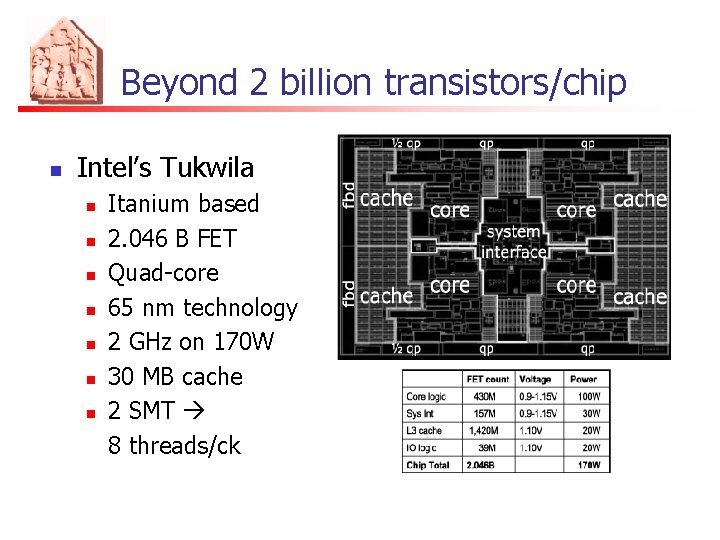

Beyond 2 billion transistors/chip n Intel’s Tukwila n n n n Itanium based 2. 046 B FET Quad-core 65 nm technology 2 GHz on 170 W 30 MB cache 2 SMT 8 threads/ck

How many cores in the future? n Intel’s 80 core prototype already available n Able to transfers a TB of data/s (while Core 2 Duo reaches 1. 66 GB data/s)

How many cores in the future? n Berkeley: weather simulation for 1. 5 km resolution, 1000 x realtime, 3 M customtailored Tensilica cores n n n Petaflop computer Power around 2. 5 MW estimated for 2011 cost around 75 M$ main obstacle will be on software

Supercomputers n n Petaflop supercomputers (current supercomputer have Teraflop computing power) IBM’s Bluegene/P n n n 3 Pflops 884736 quad-core Power PC ready before 2010

Prediction n Patterson & Hennessy: “number of cores will double every 18 months, while power, clock frequency and costs will remain constant”

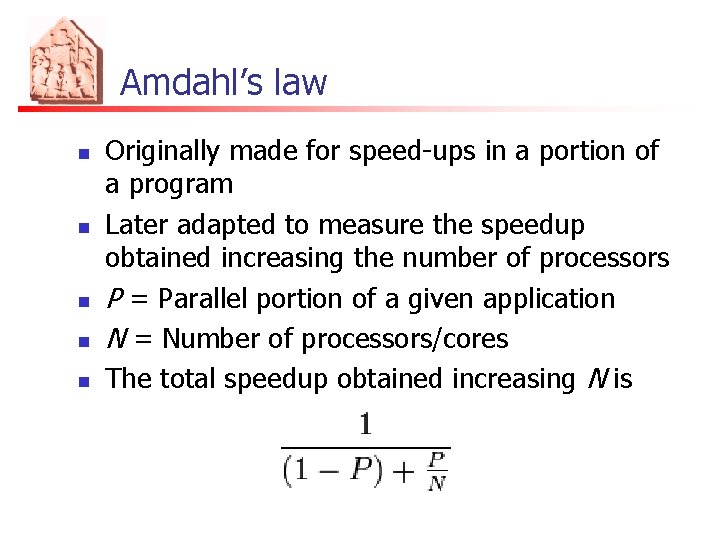

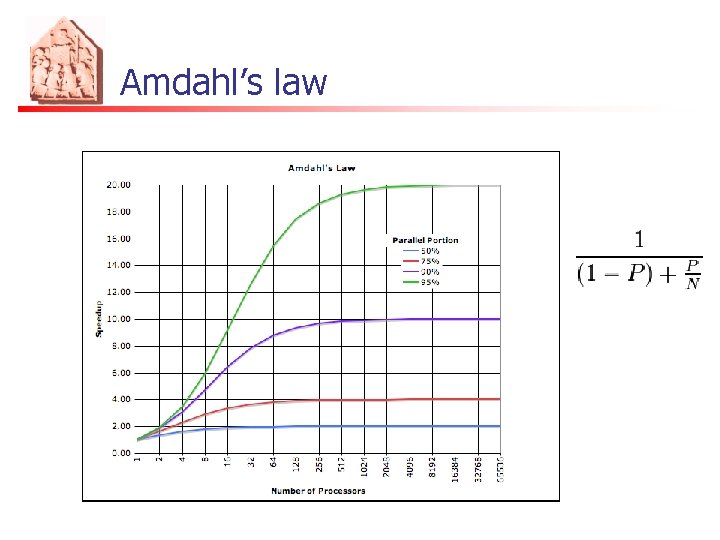

Amdahl’s law n n n Originally made for speed-ups in a portion of a program Later adapted to measure the speedup obtained increasing the number of processors P = Parallel portion of a given application N = Number of processors/cores The total speedup obtained increasing N is

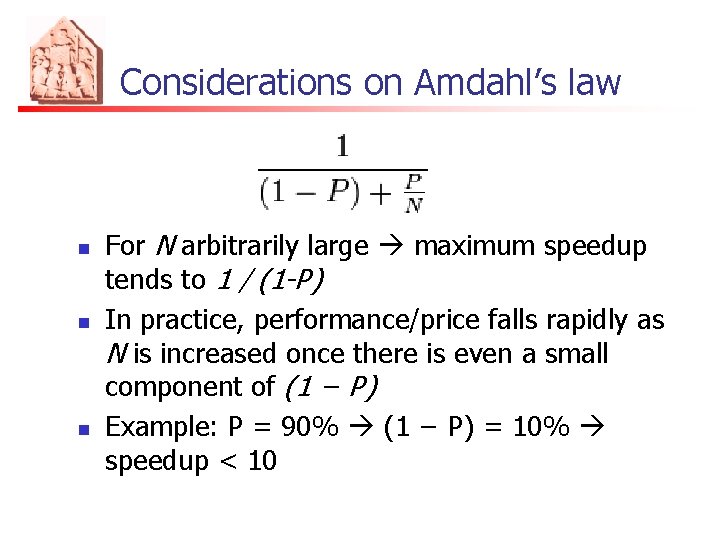

Considerations on Amdahl’s law n n n For N arbitrarily large maximum speedup tends to 1 / (1 -P) In practice, performance/price falls rapidly as N is increased once there is even a small component of (1 − P) Example: P = 90% (1 − P) = 10% speedup < 10

Amdahl’s law

Consequences of Amdahl’s law n n n “Law of diminishing returns”: picking optimal improvements, the income is each time lower so is with adding processors Considering as well the memory, bus and I/O bottlenecks, the situation gets worse Parallel computing is only useful for n n limited numbers of processors, or problems with very high values of P “embarrassingly parallel problems”

Embarassingly parallel problems n Problems for which n n no particular effort is needed to segment the problem into a very large number of parallel tasks there is no essential dependency (or communication) between those parallel tasks 1 core @ 4 GHz = 2 cores @ 2 GHz Examples: GPU handled problems, 3 D projection (independent rendering of each pixel), brute-force searching in cryptography

Performance boost with multicore n n Interrupts can be handled on an idle processor instead of preempting the running process (also for programs written for single core) Not faster execution, but smoother appearance For inherently parallel applications (graphic operations, servers, compilers, distributed computing) speedup proportional to the number of processors Limitations due to serialized RAM access and cache coherency

Less likely to benefit from multicores n n I/O bound tasks Tasks composed by a series of pipeline dependent calculations Tasks that frequently communicate with each other Tasks that contend for shared resources

Exploiting multicores n Multicore-capable OS’s n n n Windows NT 4. 0/2000/XP/2003 Server/Vista Linux and Unix-like systems Mac OS Vx. Works, QNX, etc. Multi-threaded applications n Muticore optimizations for game engines n n Half-Life 2: Episode Two, Crysis, etc. Software development tools

Parallel programming n Existing parallel programming models n n n n n Open. MP MPI IBM’s X 10 Intel’s TBB (abstraction for C++) Sun’s Fortress Cray’s Chapel Cilk (Cilk++) Codeplay’s Sieve C++ Rapidmind Development Platform

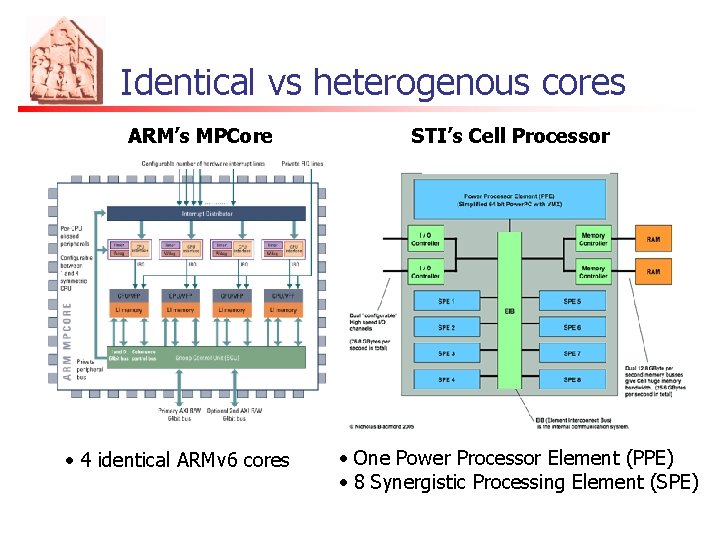

Identical vs heterogenous cores ARM’s MPCore • 4 identical ARMv 6 cores STI’s Cell Processor • One Power Processor Element (PPE) • 8 Synergistic Processing Element (SPE)

Allocating tasks to processors n Possible partitioning choices n n Partition by CPU load Partition by information-sharing requirements Partition by functionality Use the least possible number of processors or run at the lowest possible frequency n Depends on considerations like fault tolerance, power consumed, temperature, etc.

Real-time scheduling theory for multiprocessors

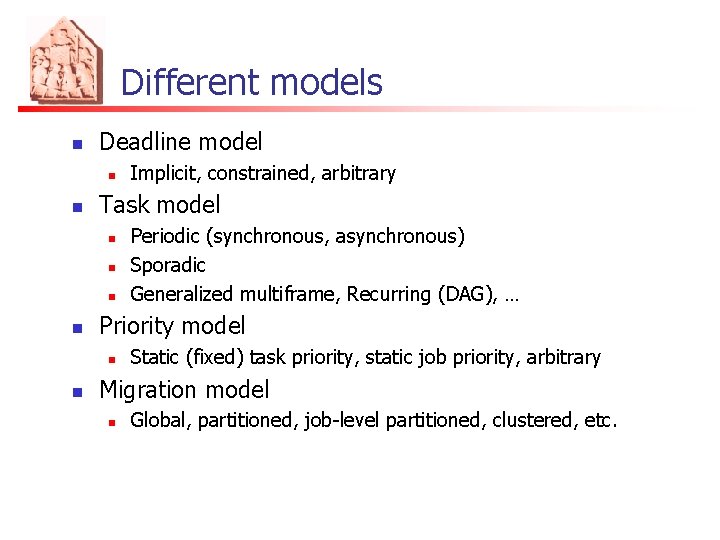

Different models n Deadline model n n Task model n n Periodic (synchronous, asynchronous) Sporadic Generalized multiframe, Recurring (DAG), … Priority model n n Implicit, constrained, arbitrary Static (fixed) task priority, static job priority, arbitrary Migration model n Global, partitioned, job-level partitioned, clustered, etc.

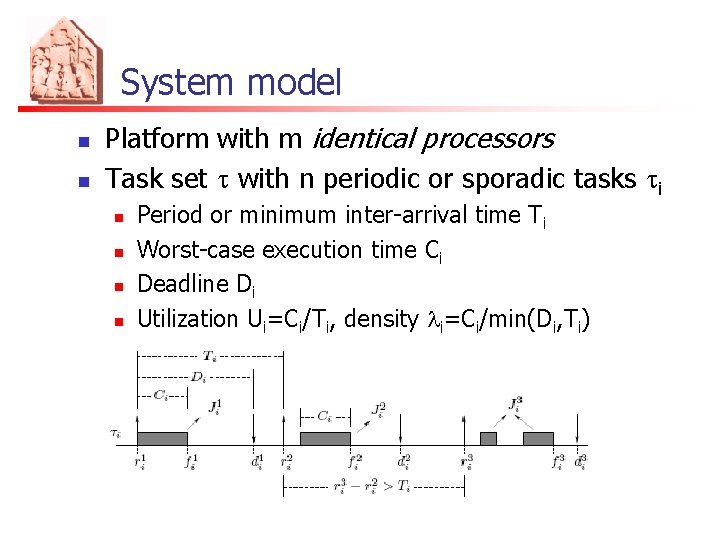

System model n n Platform with m identical processors Task set t with n periodic or sporadic tasks ti n n Period or minimum inter-arrival time Ti Worst-case execution time Ci Deadline Di Utilization Ui=Ci/Ti, density li=Ci/min(Di, Ti)

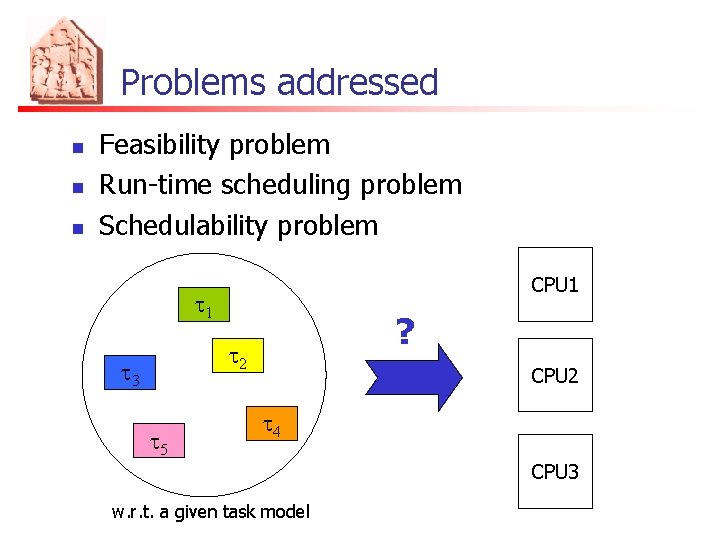

Problems addressed n n n Feasibility problem Run-time scheduling problem Schedulability problem CPU 1 t 1 ? t 2 t 3 t 5 CPU 2 t 4 CPU 3 w. r. t. a given task model

Assumptions n n Independent tasks Job-level parallelism prohibited n n Preemption and Migration support n n the same job cannot be simultaneously executed on more than one processor For global schedulers, a preempted task can resume its execution on a different processor Cost of preemption/migration integrated into task WCET

Uniprocessor RT Systems n n n n Solid theory (starting from the 70 s) Optimal schedulers Tight schedulability tests for different task models Shared resource protocols Bandwidth reservation schemes Hierarchical schedulers RTOS support

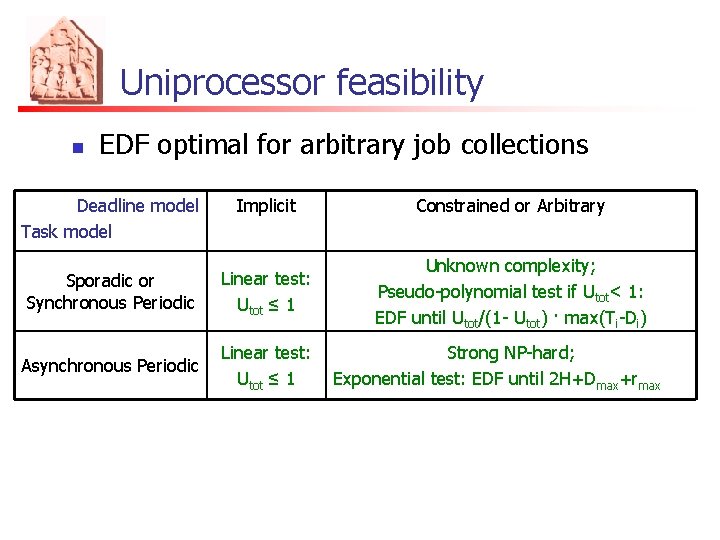

EDF for uniprocessor systems n n Optimality: if a collection of jobs can be scheduled with a given scheduling algorithm, than it is schedulable as well with EDF Bounded number of preemptions Efficient implementations Exact feasibility conditions n n linear test for implicit deadlines: Utot ≤ 1 Pseudo-polynomial test for constrained and arbitrary deadlines [Baruah et al. 90]

Uniprocessor feasibility n EDF optimal for arbitrary job collections Deadline model Task model Implicit Constrained or Arbitrary Sporadic or Synchronous Periodic Linear test: Utot ≤ 1 Unknown complexity; Pseudo-polynomial test if Utot< 1: EDF until Utot/(1 - Utot) · max(Ti-Di) Asynchronous Periodic Linear test: Utot ≤ 1 Strong NP-hard; Exponential test: EDF until 2 H+Dmax+rmax

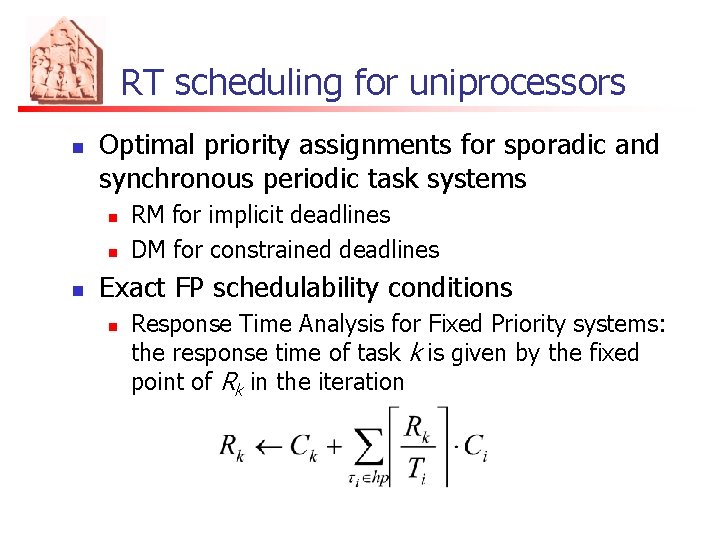

RT scheduling for uniprocessors n Optimal priority assignments for sporadic and synchronous periodic task systems n n n RM for implicit deadlines DM for constrained deadlines Exact FP schedulability conditions n Response Time Analysis for Fixed Priority systems: the response time of task k is given by the fixed point of Rk in the iteration

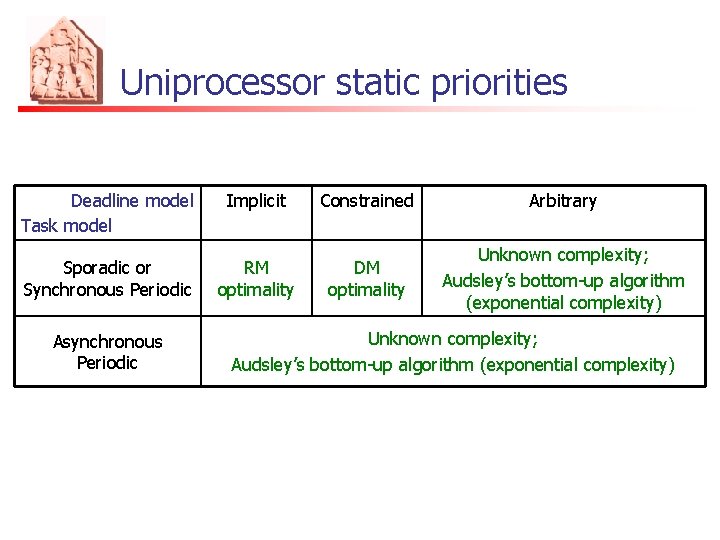

Uniprocessor static priorities Deadline model Task model Implicit Constrained Arbitrary Sporadic or Synchronous Periodic RM optimality DM optimality Unknown complexity; Audsley’s bottom-up algorithm (exponential complexity) Asynchronous Periodic Unknown complexity; Audsley’s bottom-up algorithm (exponential complexity)

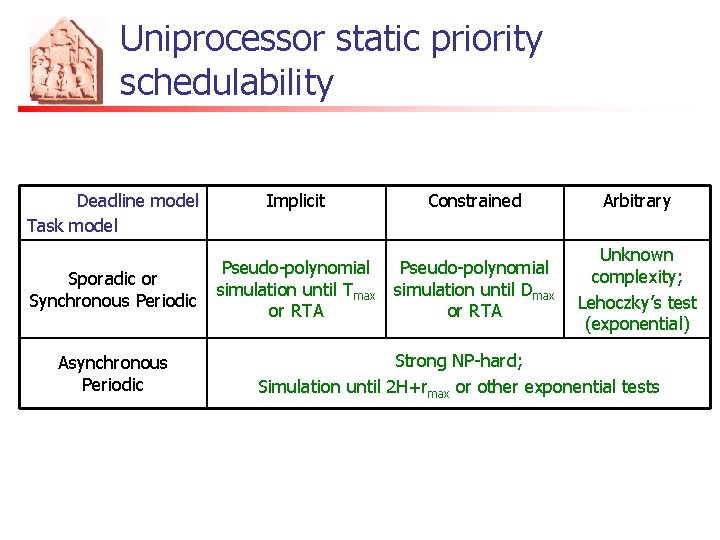

Uniprocessor static priority schedulability Deadline model Task model Sporadic or Synchronous Periodic Asynchronous Periodic Implicit Constrained Arbitrary Pseudo-polynomial simulation until Tmax or RTA Pseudo-polynomial simulation until Dmax or RTA Unknown complexity; Lehoczky’s test (exponential) Strong NP-hard; Simulation until 2 H+rmax or other exponential tests

Muliprocessors are difficult n “The simple fact that a task can use only one processor even when several processors are free at the same time adds a surprising amount of difficulty to the scheduling of multiple processors” [Liu’ 69] CPU 1 CPU 2 CPU 3

Multiprocessor RT Systems n n n n First theoretical results starting from 2000 Many NP-hard problems Few optimal results Heuristic approaches Simplified task models Only sufficient schedulability tests Limited RTOS support

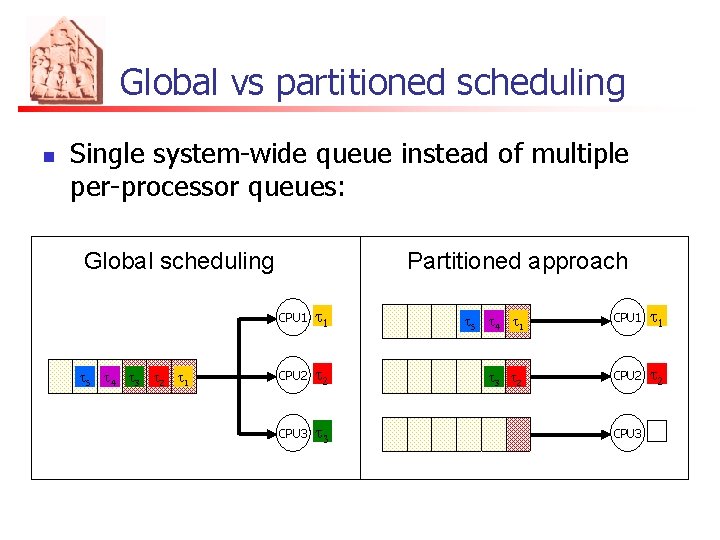

Global vs partitioned scheduling n Single system-wide queue instead of multiple per-processor queues: Global scheduling t 5 t 4 t 3 t 2 t 1 Partitioned approach CPU 1 t 5 t 4 t 1 CPU 1 t 1 CPU 2 t 3 t 2 CPU 2 t 2 CPU 3 t 3 CPU 3

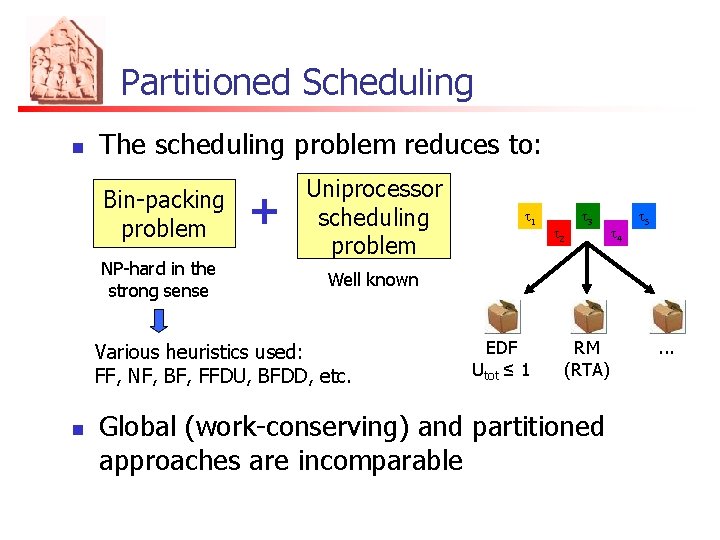

Partitioned Scheduling n The scheduling problem reduces to: Bin-packing problem NP-hard in the strong sense + Uniprocessor scheduling problem t 2 t 3 t 4 t 5 Well known Various heuristics used: FF, NF, BF, FFDU, BFDD, etc. n t 1 EDF Utot ≤ 1 RM (RTA) Global (work-conserving) and partitioned approaches are incomparable . . .

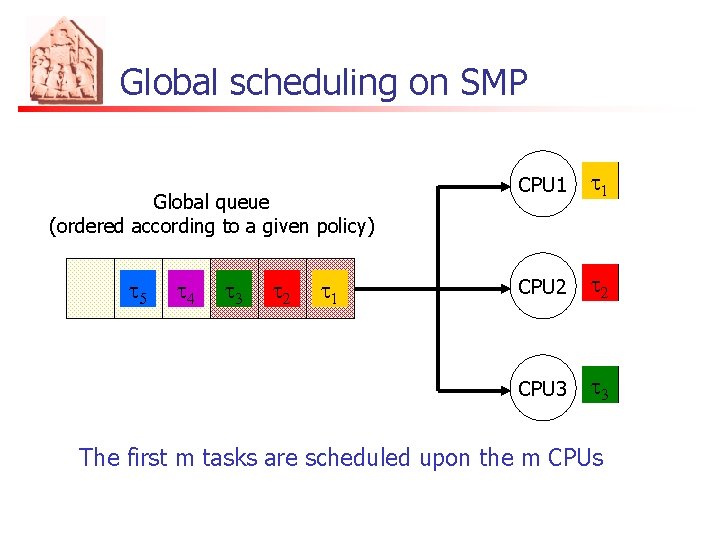

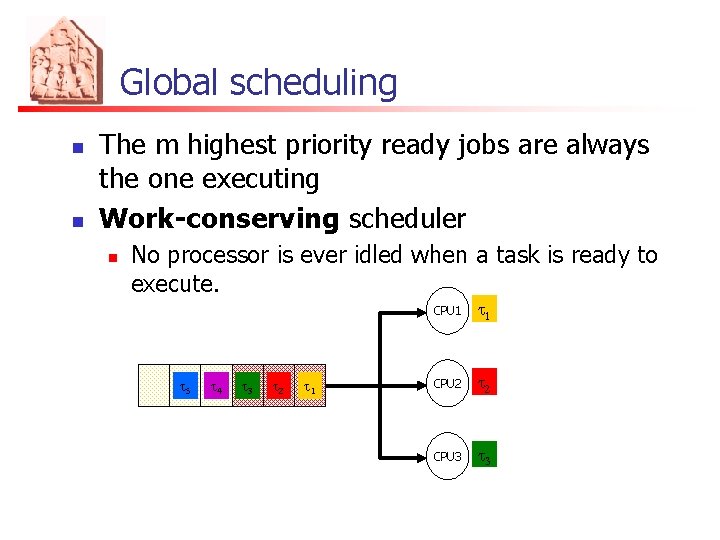

Global scheduling on SMP Global queue (ordered according to a given policy) t 5 t 4 t 3 t 2 t 1 CPU 1 t 1 CPU 2 t 2 CPU 3 t 3 The first m tasks are scheduled upon the m CPUs

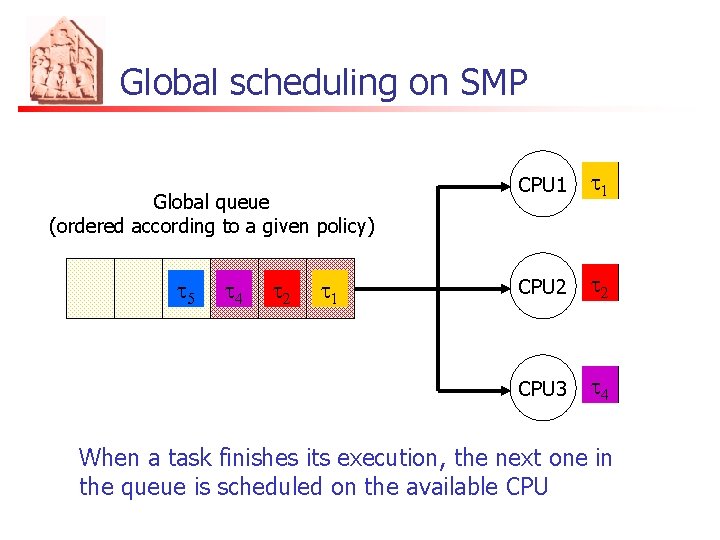

Global scheduling on SMP Global queue (ordered according to a given policy) t 54 t 43 t 2 t 1 CPU 1 t 1 CPU 2 t 2 CPU 3 t 43 When a task finishes its execution, the next one in the queue is scheduled on the available CPU

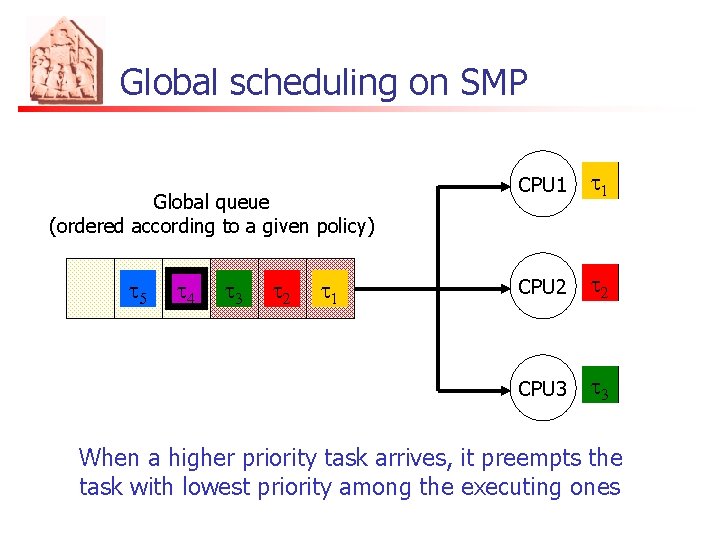

Global scheduling on SMP Global queue (ordered according to a given policy) t 5 t 45 t 34 t 2 t 1 CPU 1 t 1 CPU 2 t 2 CPU 3 t 34 t 3 When a higher priority task arrives, it preempts the task with lowest priority among the executing ones

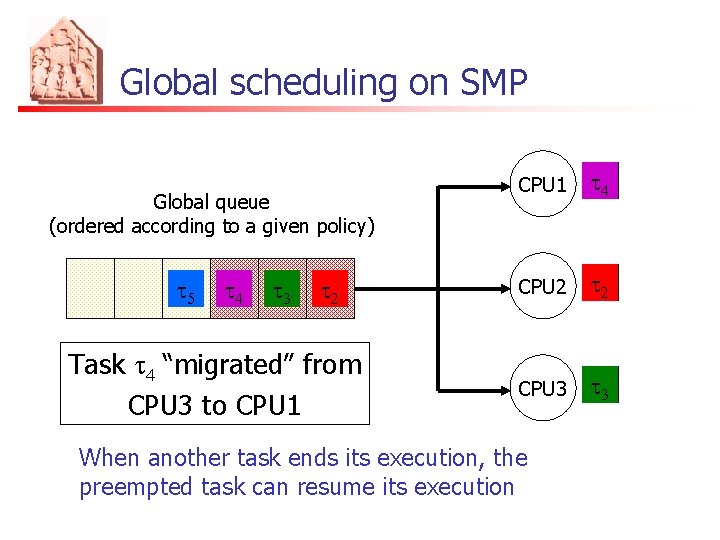

Global scheduling on SMP Global queue (ordered according to a given policy) t 54 t 43 t 32 t 21 Task t 4 “migrated” from CPU 3 to CPU 1 t 41 CPU 2 t 2 CPU 3 t 34 When another task ends its execution, the preempted task can resume its execution

Global scheduling n n The m highest priority ready jobs are always the one executing Work-conserving scheduler n No processor is ever idled when a task is ready to execute. t 5 t 4 t 3 t 2 t 1 CPU 1 t 1 CPU 2 t 2 CPU 3 t 3

Global scheduling: advantages Load automatically balanced Easier re-scheduling (dynamic loads, selective shutdown, etc. ) Lower average response time (see queueing theory) More efficient reclaiming and overload management Number of preemptions Migration cost: can be mitigated by proper HW (e. g. , MPCore’s Direct Data Intervention) Few schedulability tests Further research needed

Global Scheduling problem n Pfair optimal only for implicit deadlines: Utot ≤ m n n preemption and synchronization issues No optimal scheduler known for more general task models Classic schedulers are not optimal: Dhall’s effect Hybrid schedulers: EDF-US, RM-US, DM-DS, Adaptive. Tk. C, fp. EDF, EDF(k), EDZL, …

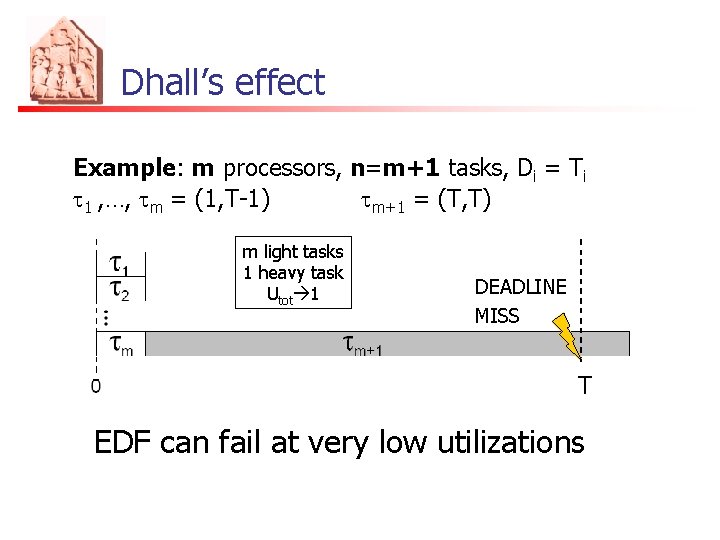

Dhall’s effect Example: m processors, n=m+1 tasks, Di = Ti t 1 , …, tm = (1, T-1) tm+1 = (T, T) m light tasks 1 heavy task Utot 1 DEADLINE MISS T EDF can fail at very low utilizations

Hybrid schedulers n EDF-US, RM-US, DM-DS, fp. EDF n n EDF(k), RM(k), DM(k) n n assign priorities according to a function (T- k C) EDZL n n give highest priority to the heaviest k tasks and schedule the remaining ones with EDF/RM/DM Adaptive. Tk. C n n give highest static priority to the heaviest tasks and schedule the remaining ones with EDF/RM/DM … Schedule tasks with EDF, raising the priority to the jobs that reach zero laxity

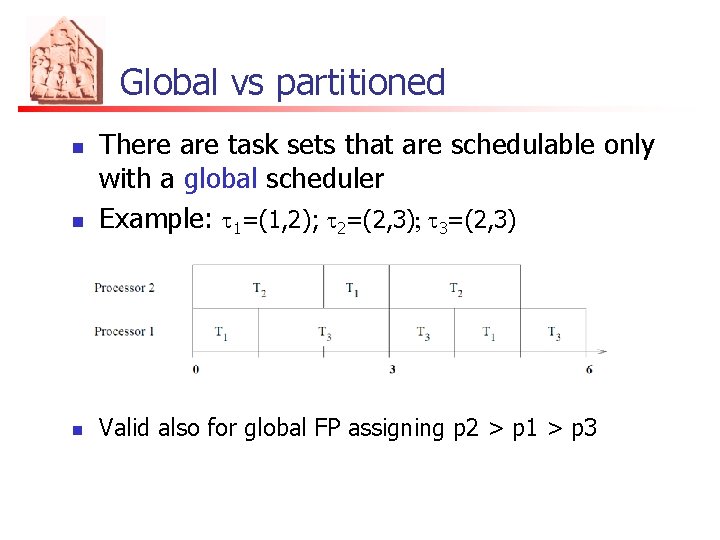

Global vs partitioned n There are task sets that are schedulable only with a global scheduler Example: t 1=(1, 2); t 2=(2, 3); t 3=(2, 3) n Valid also for global FP assigning p 2 > p 1 > p 3 n

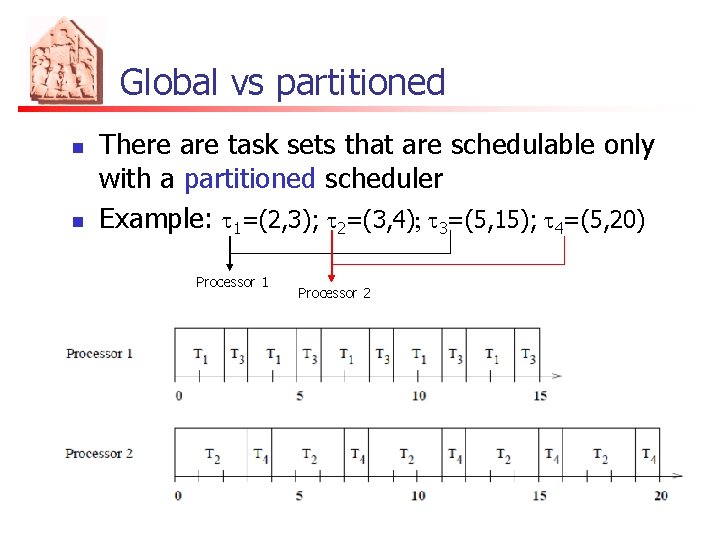

Global vs partitioned n n There are task sets that are schedulable only with a partitioned scheduler Example: t 1=(2, 3); t 2=(3, 4); t 3=(5, 15); t 4=(5, 20) Processor 1 Processor 2

Global vs partitioned t 1=(2, 3); t 2=(3, 4); t 3=(5, 15); t 4=(5, 20) n n n In interval [0, 12) there are 9 jobs 9! possible job priority assignments For all of them there is either a deadline miss or an idle slot in [0, 12) Since total utilization equals m deadline miss

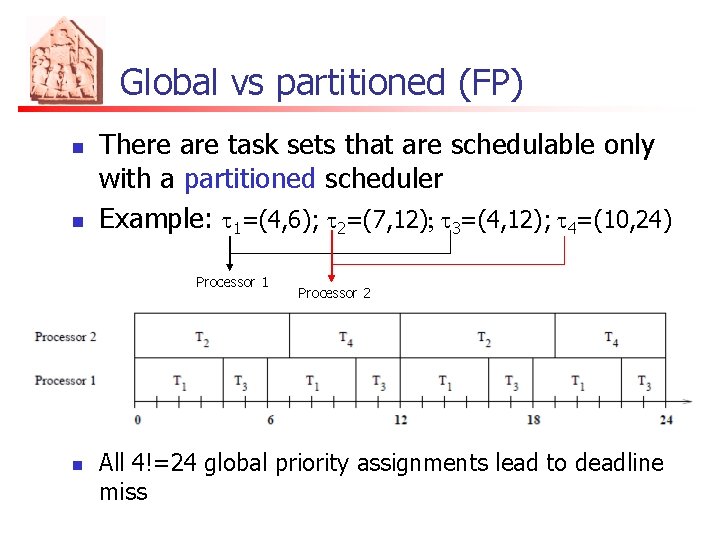

Global vs partitioned (FP) n n There are task sets that are schedulable only with a partitioned scheduler Example: t 1=(4, 6); t 2=(7, 12); t 3=(4, 12); t 4=(10, 24) Processor 1 n Processor 2 All 4!=24 global priority assignments lead to deadline miss

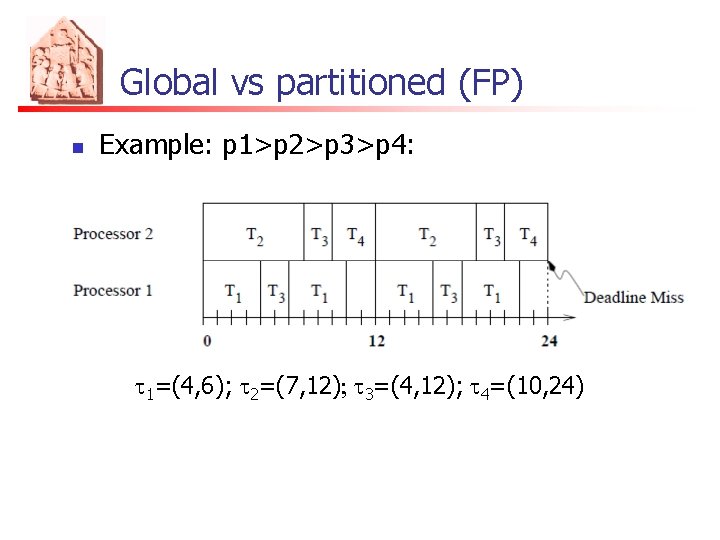

Global vs partitioned (FP) n Example: p 1>p 2>p 3>p 4: t 1=(4, 6); t 2=(7, 12); t 3=(4, 12); t 4=(10, 24)

Partitioned scheduling heuristics n n n n First Fit (FF) Best Fit (BF) Worst Fit (WF) Next Fit (NF) FFD BFD …

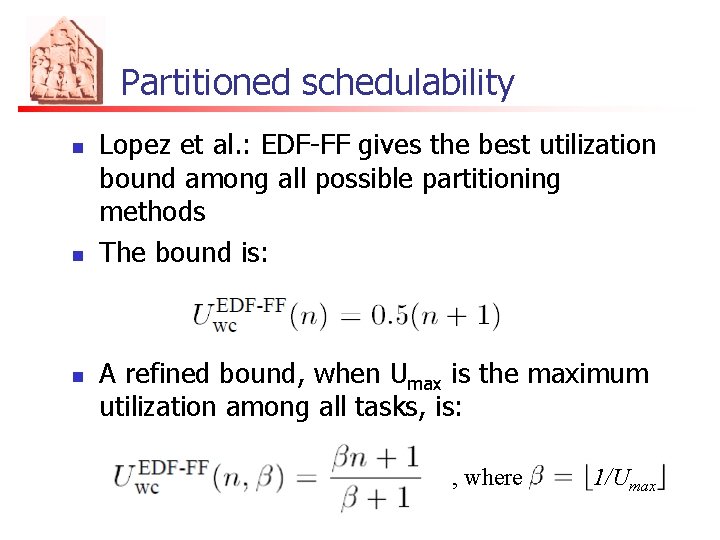

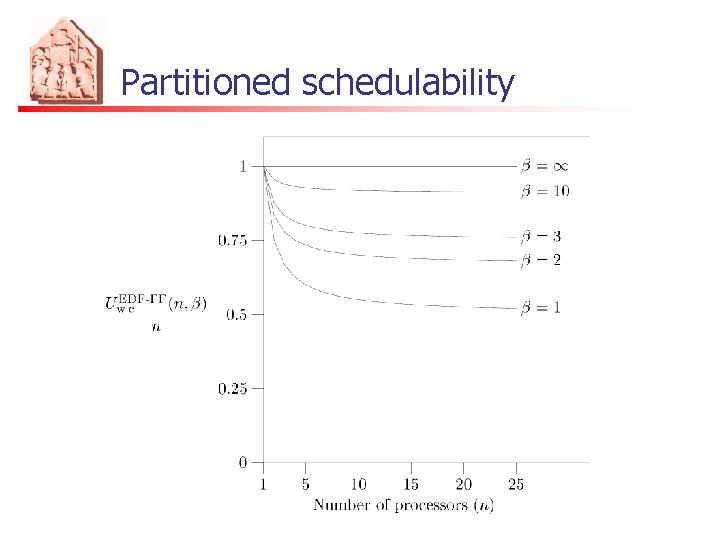

Partitioned schedulability n n n Lopez et al. : EDF-FF gives the best utilization bound among all possible partitioning methods The bound is: A refined bound, when Umax is the maximum utilization among all tasks, is: , where = 1/Umax

Partitioned schedulability

Tightness of the bound n n The bound is tight Take tasks with utilization By definition of , tasks of utilization Umax do not fit into one processor Umax > the set is well defined At least one processor should allocate or more tasks but they do not fit since deadline miss

Partitioned schedulability n n n BF, BFD, FFD also give the same utilization bound, but with a higher computational complexity Among fixed priority systems, the best utilization bound is given by FFD and BFD The bound for fixed priority is somewhat more complicated (see Lopez et al. ’ 04)

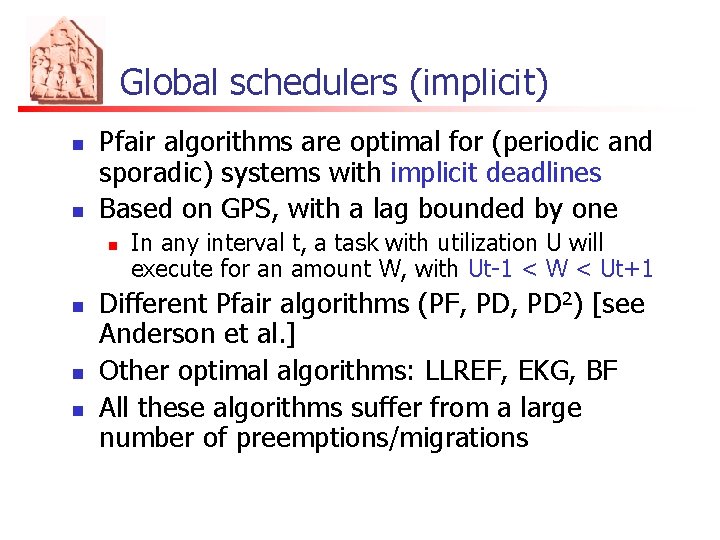

Global schedulers (implicit) n n Pfair algorithms are optimal for (periodic and sporadic) systems with implicit deadlines Based on GPS, with a lag bounded by one n n In any interval t, a task with utilization U will execute for an amount W, with Ut-1 < W < Ut+1 Different Pfair algorithms (PF, PD 2) [see Anderson et al. ] Other optimal algorithms: LLREF, EKG, BF All these algorithms suffer from a large number of preemptions/migrations

Global scheduling (constrained) n n n No optimal algorithm is known for constrained or arbitrary deadline systems No optimal on-line algorithm is possible for arbitrary collection of jobs [Leung and Whitehead] Even for sporadic task system optimality requires clairvoyance [Fisher et al’ 09]

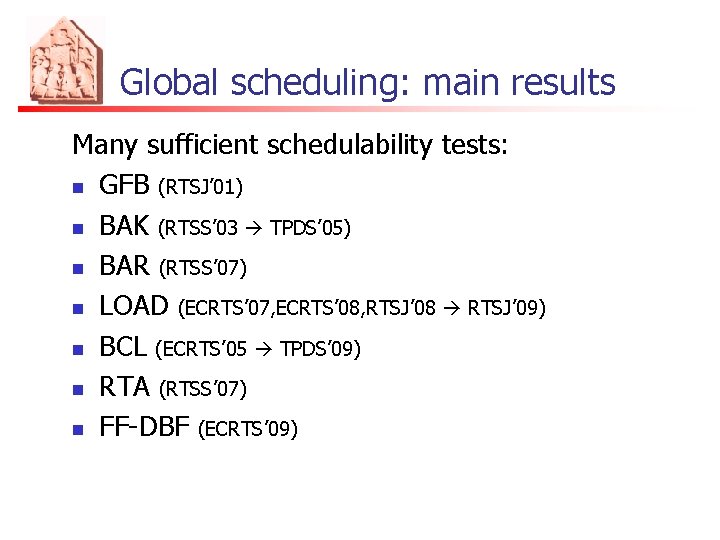

Global scheduling: main results Many sufficient schedulability tests: n GFB (RTSJ’ 01) n BAK (RTSS’ 03 TPDS’ 05) n BAR (RTSS’ 07) n LOAD (ECRTS’ 07, ECRTS’ 08, RTSJ’ 08 RTSJ’ 09) n BCL (ECRTS’ 05 TPDS’ 09) n RTA (RTSS’ 07) n FF-DBF (ECRTS’ 09)

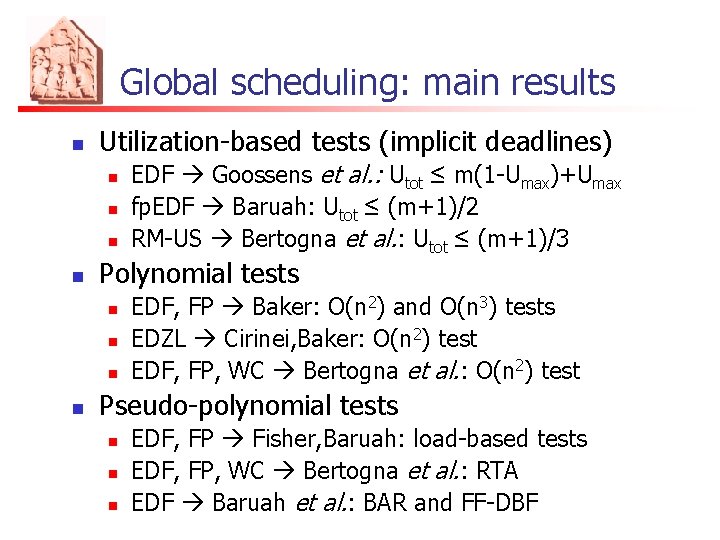

Global scheduling: main results n Utilization-based tests (implicit deadlines) n n Polynomial tests n n EDF Goossens et al. : Utot ≤ m(1 -Umax)+Umax fp. EDF Baruah: Utot ≤ (m+1)/2 RM-US Bertogna et al. : Utot ≤ (m+1)/3 EDF, FP Baker: O(n 2) and O(n 3) tests EDZL Cirinei, Baker: O(n 2) test EDF, FP, WC Bertogna et al. : O(n 2) test Pseudo-polynomial tests n n n EDF, FP Fisher, Baruah: load-based tests EDF, FP, WC Bertogna et al. : RTA EDF Baruah et al. : BAR and FF-DBF

Global schedulability tests n n n Few dominance results Most tests are incomparable Different possible metrics for evaluation

Possible metrics for evaluation n Percentage of schedulable task set detected n n n Processor speedup factor s n n n Over a randomly generated load Depends on the task generation method All feasible task sets pass the test on a platform in which all processors are s times as fast Run-time complexity Sustainability and predictability properties n Tests still succeeds if Ci , Ti , Di

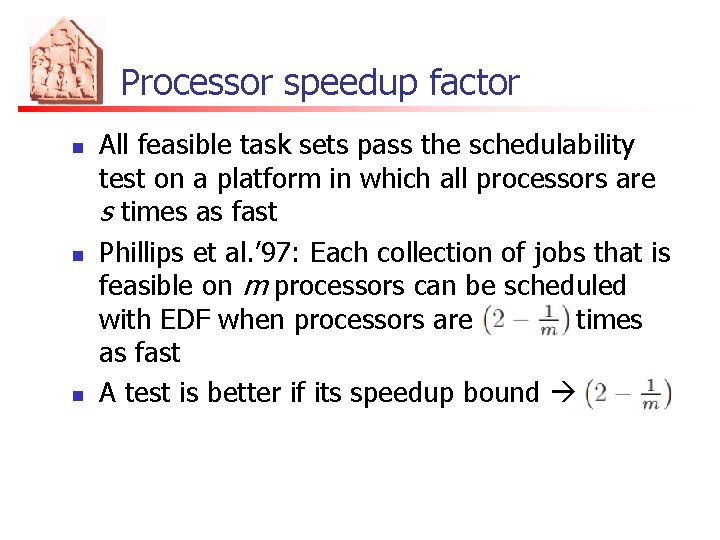

Processor speedup factor n n n All feasible task sets pass the schedulability test on a platform in which all processors are s times as fast Phillips et al. ’ 97: Each collection of jobs that is feasible on m processors can be scheduled with EDF when processors are times as fast A test is better if its speedup bound

Sustainability n A scheduling algorithm is sustainable iff schedulability of a task set is preserved when 1. 2. 3. n n decreasing execution requirements increasing periods of inter-arrival times increasing relative deadlines Baker and Baruah [ECRTS’ 09]: global EDF for sporadic task sets is sustainable w. r. t. points 1. and 2. Sustainable schedulability test

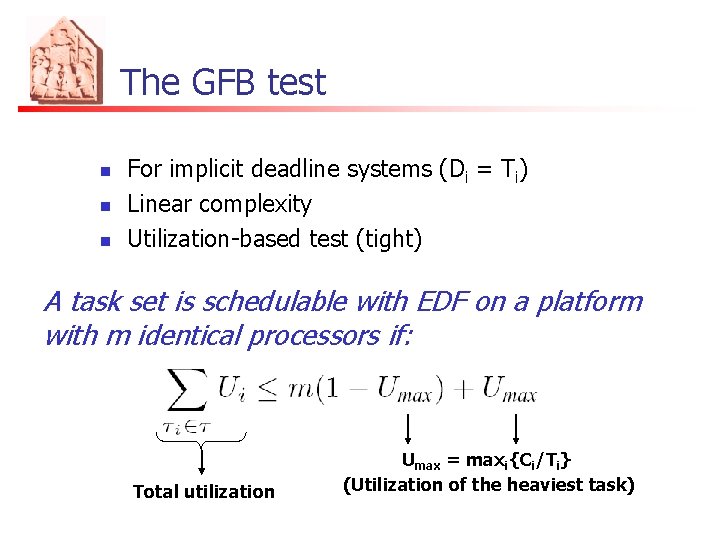

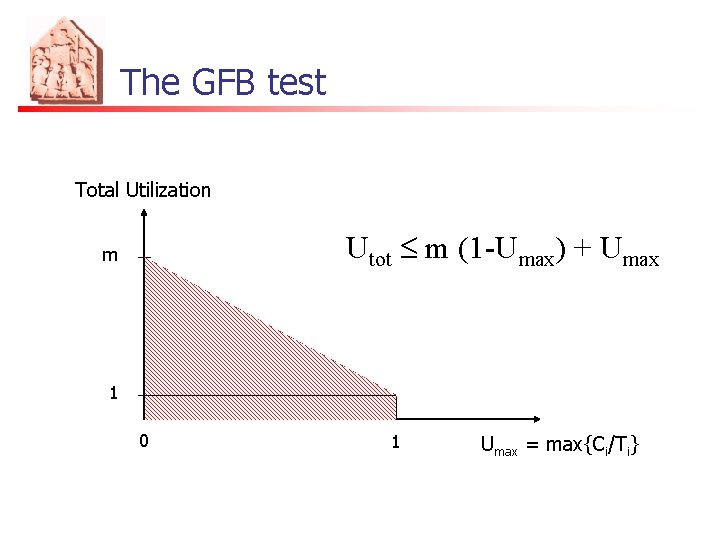

The GFB test n n n For implicit deadline systems (Di = Ti) Linear complexity Utilization-based test (tight) A task set is schedulable with EDF on a platform with m identical processors if: Total utilization Umax = maxi{Ci/Ti} (Utilization of the heaviest task)

The GFB test Total Utilization Utot £ m (1 -Umax) + Umax m 1 0 1 Umax = max{Ci/Ti}

GFB n n Density-based test linear complexity Sustainable w. r. t. all parameters

![Density-based tests n n EDF: ltot ≤ m(1 -lmax)+lmax EDF-DS[1/2]: ltot ≤ (m+1)/2 [ECRTS’ Density-based tests n n EDF: ltot ≤ m(1 -lmax)+lmax EDF-DS[1/2]: ltot ≤ (m+1)/2 [ECRTS’](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/be26f0191301bca5dca226c17ea6a11c/image-82.jpg)

Density-based tests n n EDF: ltot ≤ m(1 -lmax)+lmax EDF-DS[1/2]: ltot ≤ (m+1)/2 [ECRTS’ 05] Gives highest priority to (at most m-1) tasks having lt ≥ 1/2, and schedules the remaining ones with EDF n n DM: ltot ≤ m(1–lmax)/2+lmax DM-DS[1/3]: ltot ≤ (m+1)/3 Gives highest priority to (at most m-1) tasks having lt ≥ 1/3, and schedules the remaining ones with DM (only constrained deadlines) [OPODIS’ 05]

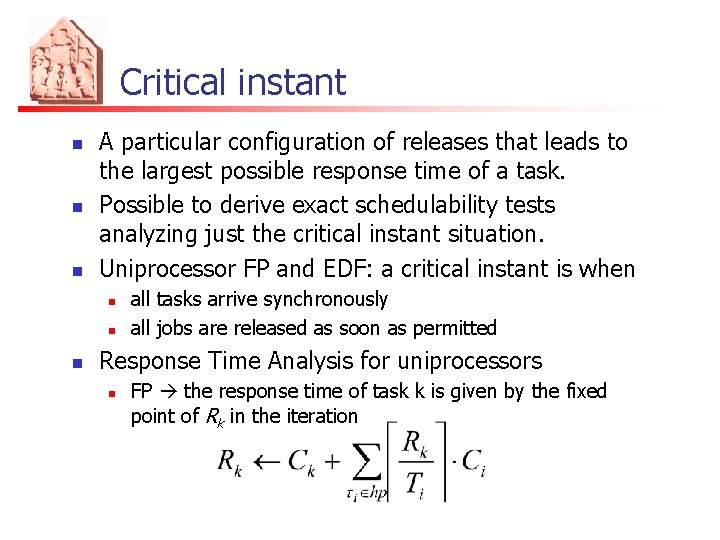

Critical instant n n n A particular configuration of releases that leads to the largest possible response time of a task. Possible to derive exact schedulability tests analyzing just the critical instant situation. Uniprocessor FP and EDF: a critical instant is when n all tasks arrive synchronously all jobs are released as soon as permitted Response Time Analysis for uniprocessors n FP the response time of task k is given by the fixed point of Rk in the iteration

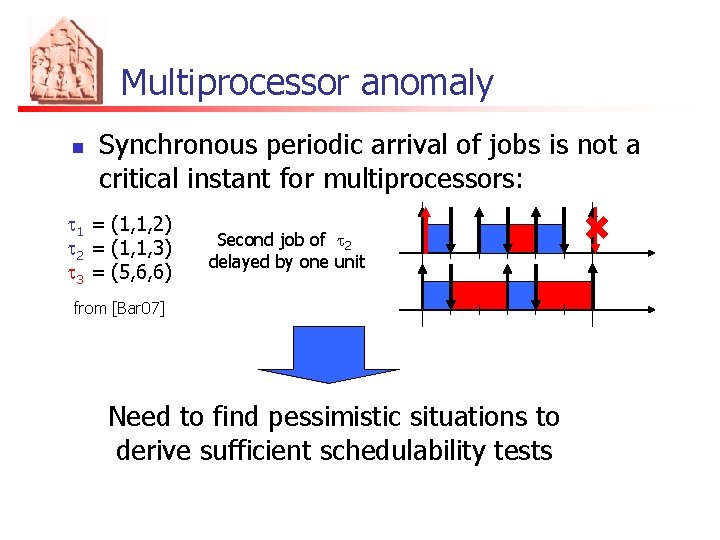

Multiprocessor anomaly n Synchronous periodic arrival of jobs is not a critical instant for multiprocessors: t 1 = (1, 1, 2) t 2 = (1, 1, 3) t 3 = (5, 6, 6) Second job periodic of t 2 Synchronous delayed situation by one unit from [Bar 07] Need to find pessimistic situations to derive sufficient schedulability tests

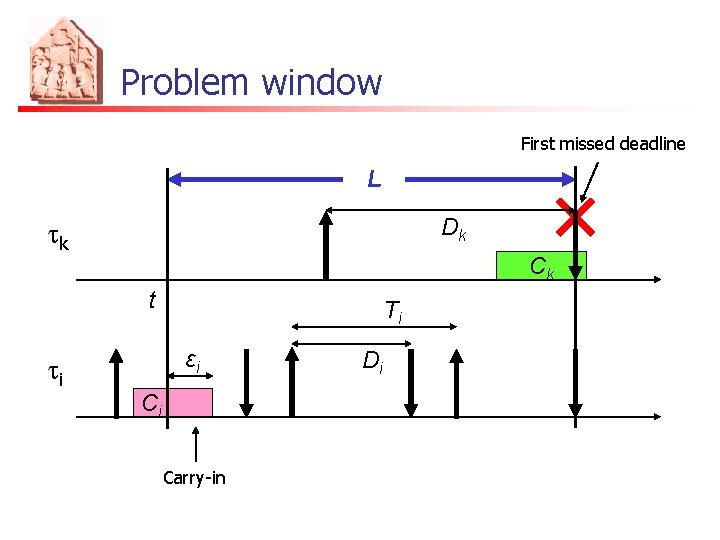

Problem window First missed deadline L Dk tk Ck t Ti εi ti Ci Carry-in Di

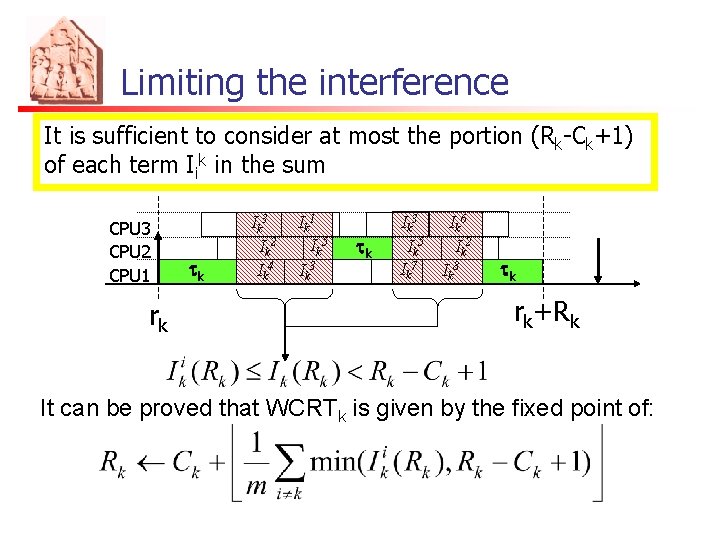

Adopted techniques n n Consider the interference on the problem job Bound the interference with the workload Use an upper bound on the workload Existing schedulability tests differ in n n Problem window selection: L Carry-in bound εi in the considered window n n n Amount of each contribution (BAK, LOAD, BCL, RTA) Number of carry-in contributions (BAR, LOAD) Total amount of all contributions (FF-DBF, GFB)

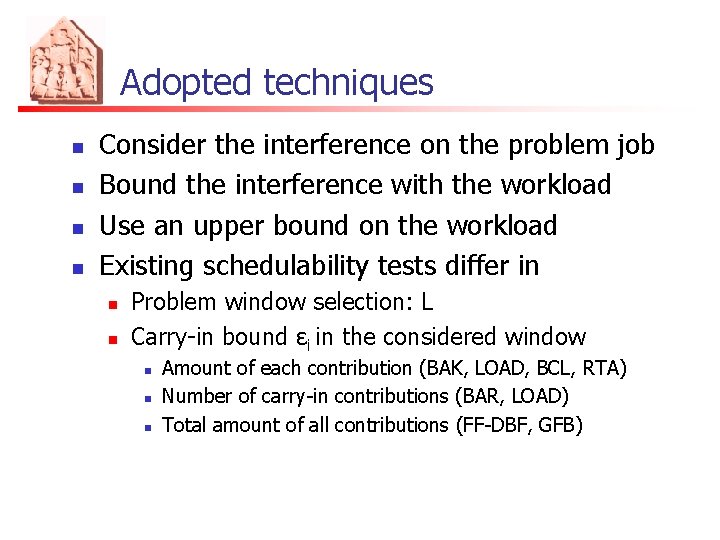

Introducing the interference Ik = Total interference suffered by task tk Iki = Interference of task ti on task tk CPU 3 CPU 2 CPU 1 rk tk Ik 3 Ik 2 Ik 4 Ik 1 Ik 5 Ik 3 tk Ik 3 Ik 6 Ik 5 Ik 2 Ik 7 Ik 8 tk rk+Rk

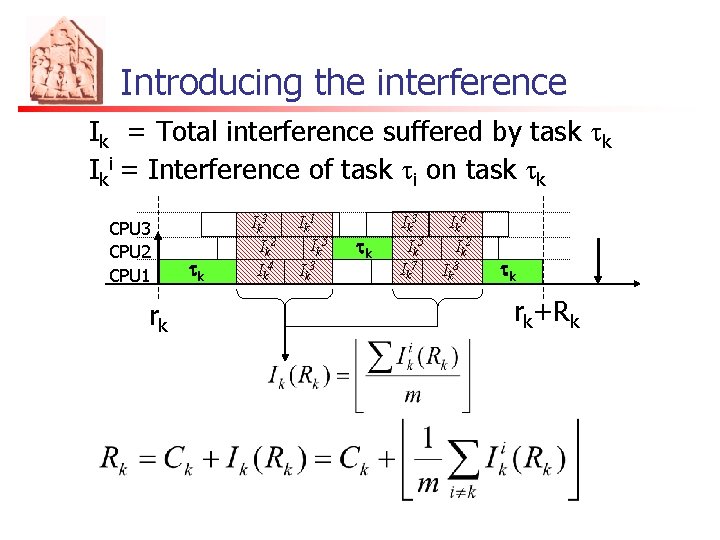

Limiting the interference It is sufficient to consider at most the portion (Rk-Ck+1) of each term Iik in the sum CPU 3 CPU 2 CPU 1 rk tk Ik 3 Ik 2 Ik 4 Ik 1 Ik 5 Ik 3 tk Ik 3 Ik 6 Ik 5 Ik 2 Ik 7 Ik 8 tk rk+Rk It can be proved that WCRTk is given by the fixed point of:

Bounding the interference Exactly computing the interference is complex 1. Pessimistic assumptions: Bound the interference of a task with the workload: 2. Use an upper bound on the workload.

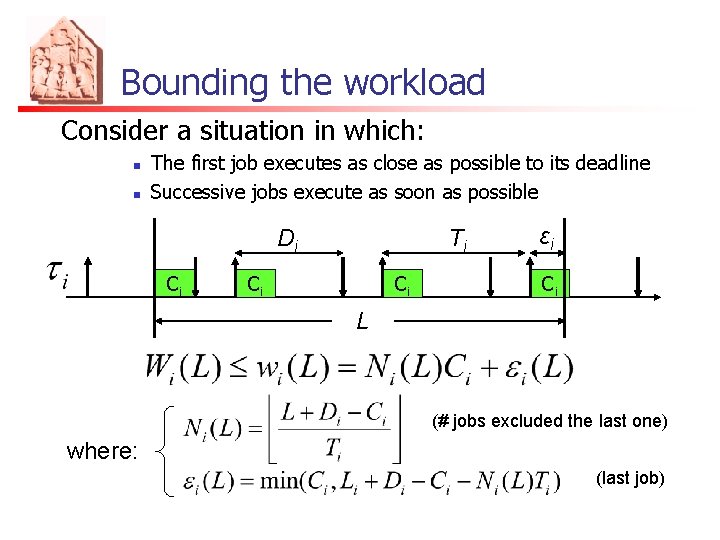

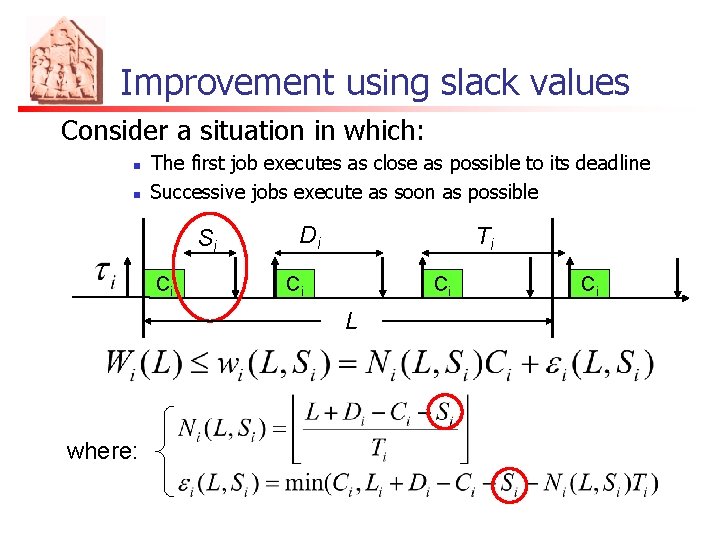

Bounding the workload Consider a situation in which: n n The first job executes as close as possible to its deadline Successive jobs execute as soon as possible Di Ci Ti Ci Ci εi Ci L (# jobs excluded the last one) where: (last job)

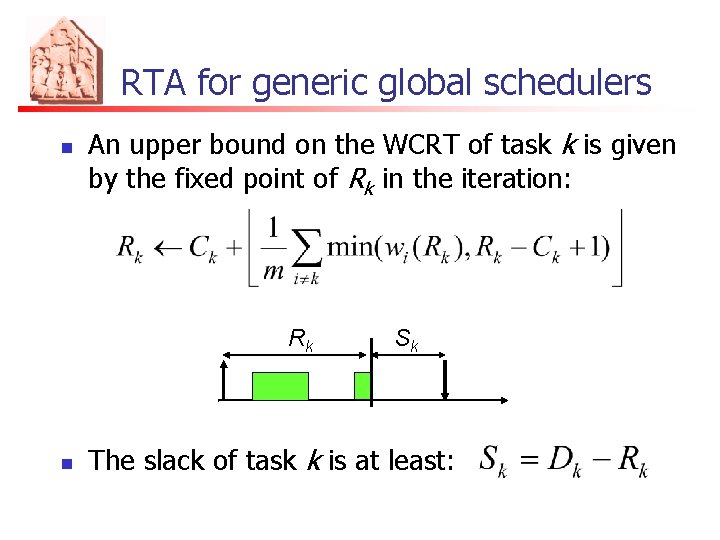

RTA for generic global schedulers n An upper bound on the WCRT of task k is given by the fixed point of Rk in the iteration: Rk n Sk The slack of task k is at least:

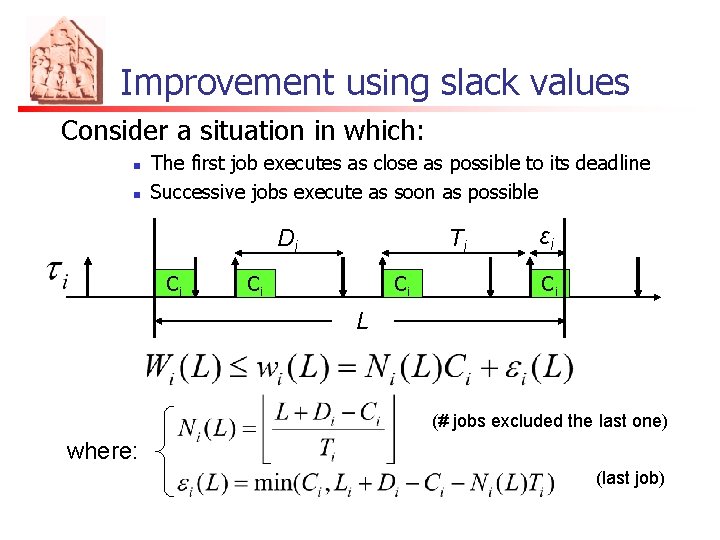

Improvement using slack values Consider a situation in which: n n The first job executes as close as possible to its deadline Successive jobs execute as soon as possible Di Ci Ti Ci Ci εi Ci L (# jobs excluded the last one) where: (last job)

Improvement using slack values Consider a situation in which: n n The first job executes as close as possible to its deadline Successive jobs execute as soon as possible Si Ci Di Ti Ci Ci L where: Ci

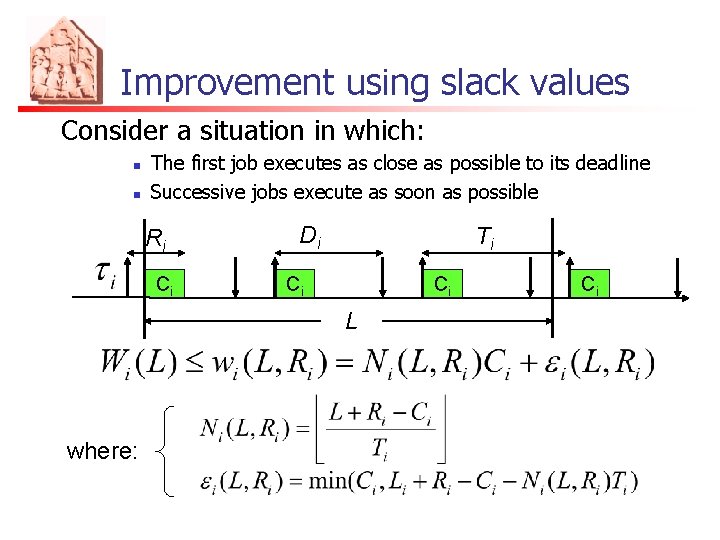

Improvement using slack values Consider a situation in which: n n The first job executes as close as possible to its deadline Successive jobs execute as soon as possible Ri Ci Di Ti Ci Ci L where: Ci

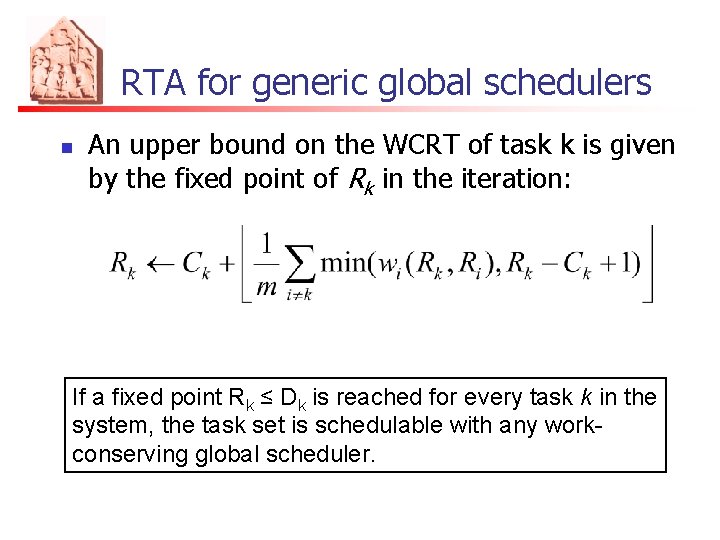

RTA for generic global schedulers n An upper bound on the WCRT of task k is given by the fixed point of Rk in the iteration: If a fixed point Rk ≤ Dk is reached for every task k in the system, the task set is schedulable with any workconserving global scheduler.

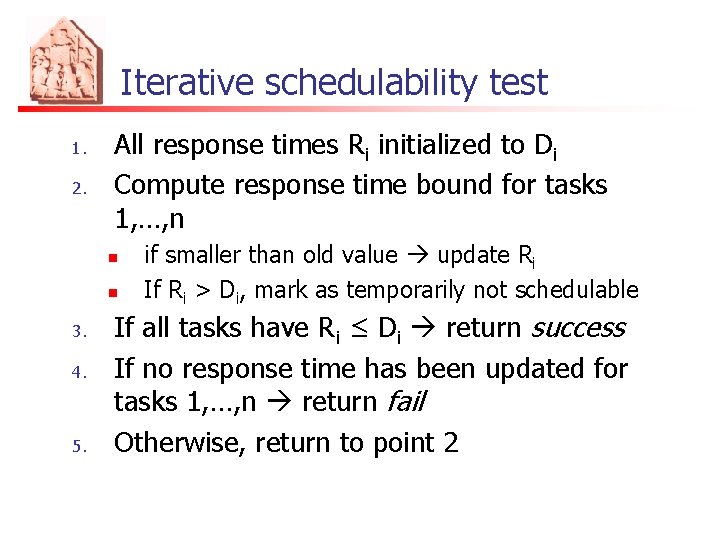

Iterative schedulability test 1. 2. All response times Ri initialized to Di Compute response time bound for tasks 1, …, n n n 3. 4. 5. if smaller than old value update Ri If Ri > Di, mark as temporarily not schedulable If all tasks have Ri ≤ Di return success If no response time has been updated for tasks 1, …, n return fail Otherwise, return to point 2

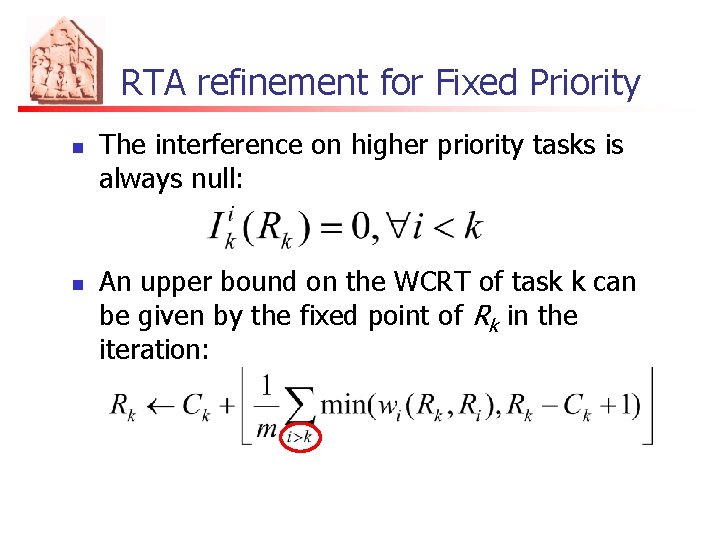

RTA refinement for Fixed Priority n n The interference on higher priority tasks is always null: An upper bound on the WCRT of task k can be given by the fixed point of Rk in the iteration:

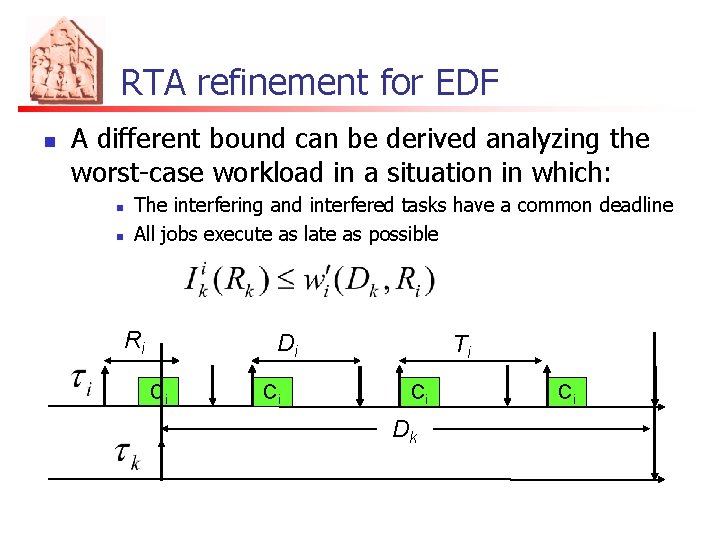

RTA refinement for EDF n A different bound can be derived analyzing the worst-case workload in a situation in which: n n The interfering and interfered tasks have a common deadline All jobs execute as late as possible Ri Di Ci Ci Ti Ci Dk Ci

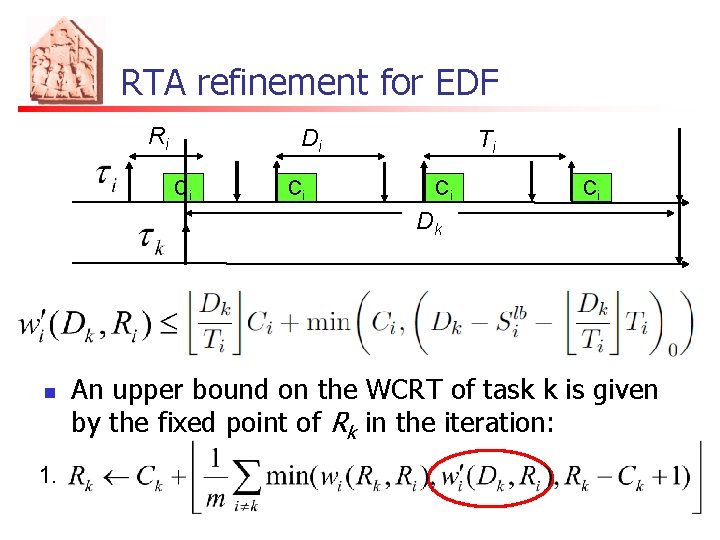

RTA refinement for EDF Ri Di Ci Ci Ti Ci Ci Dk n 1. An upper bound on the WCRT of task k is given by the fixed point of Rk in the iteration:

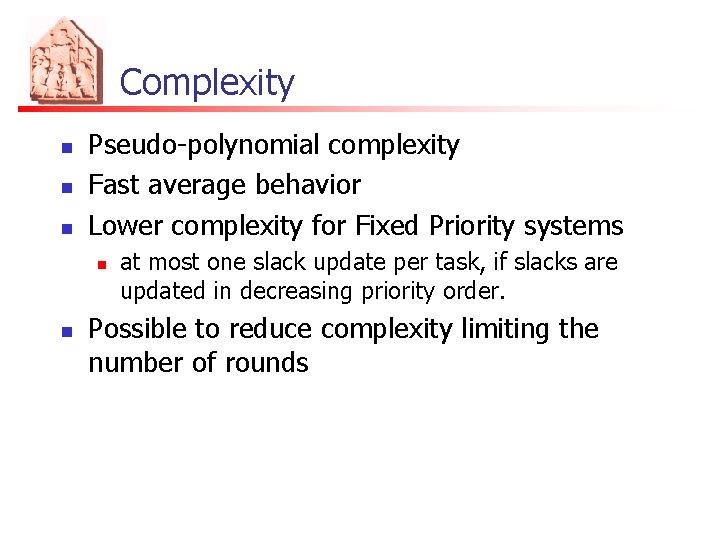

Complexity n n n Pseudo-polynomial complexity Fast average behavior Lower complexity for Fixed Priority systems n n at most one slack update per task, if slacks are updated in decreasing priority order. Possible to reduce complexity limiting the number of rounds

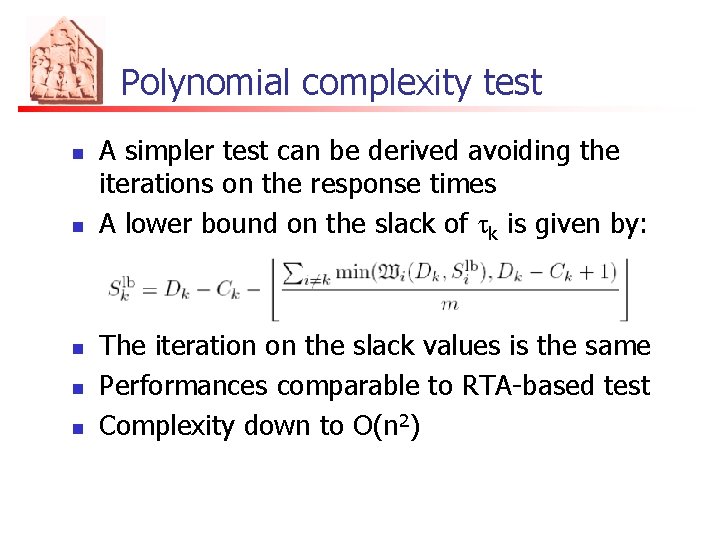

Polynomial complexity test n n n A simpler test can be derived avoiding the iterations on the response times A lower bound on the slack of tk is given by: The iteration on the slack values is the same Performances comparable to RTA-based test Complexity down to O(n 2)

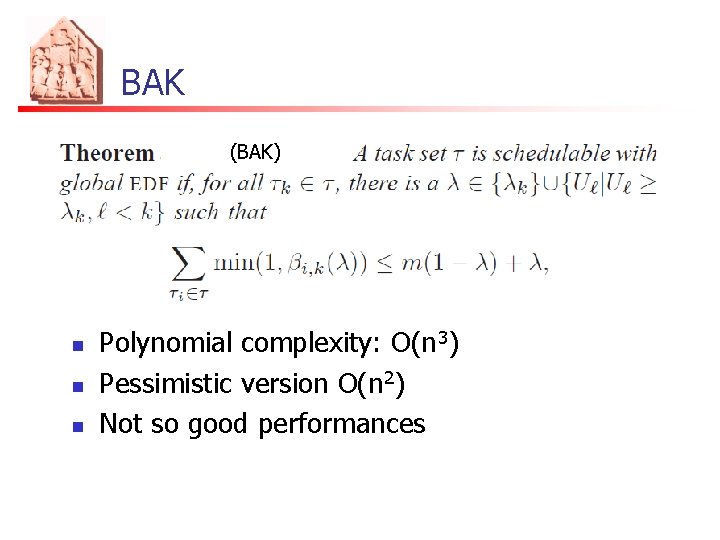

BAK (BAK) n n n Polynomial complexity: O(n 3) Pessimistic version O(n 2) Not so good performances

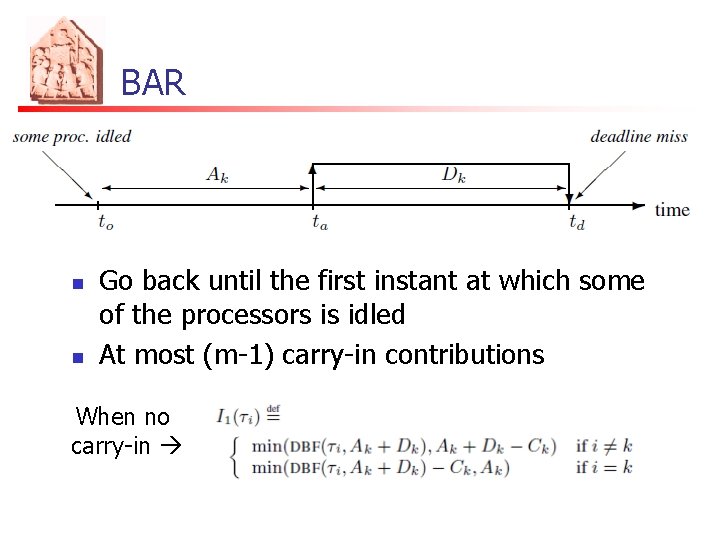

BAR n n Go back until the first instant at which some of the processors is idled At most (m-1) carry-in contributions When no carry-in

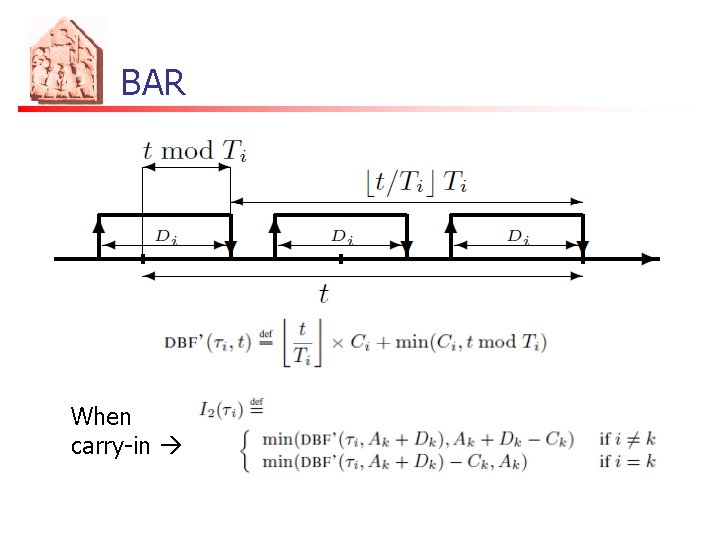

BAR When carry-in

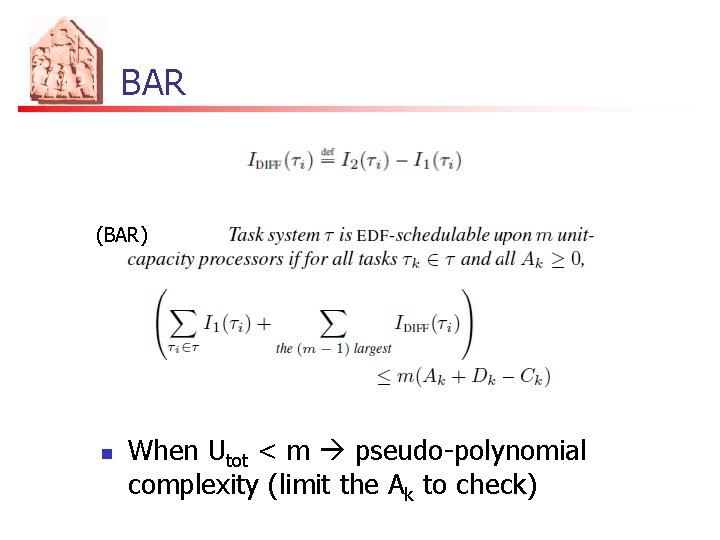

BAR (BAR) n When Utot < m pseudo-polynomial complexity (limit the Ak to check)

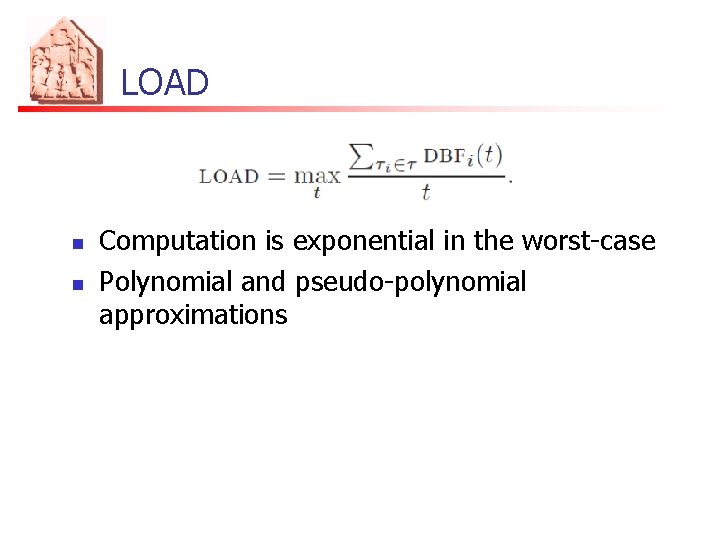

LOAD n n Computation is exponential in the worst-case Polynomial and pseudo-polynomial approximations

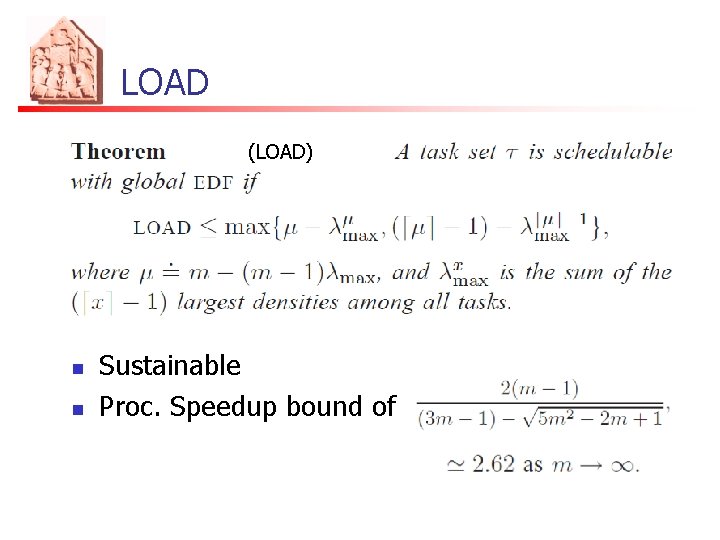

LOAD (LOAD) n n Sustainable Proc. Speedup bound of

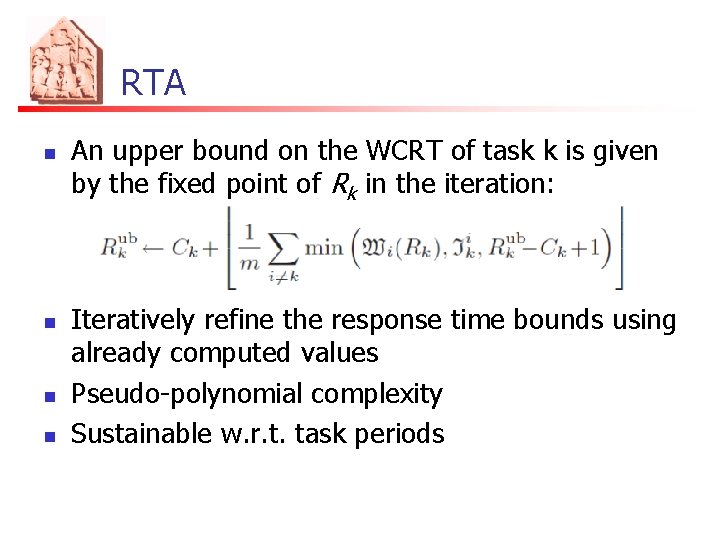

RTA n n An upper bound on the WCRT of task k is given by the fixed point of Rk in the iteration: Iteratively refine the response time bounds using already computed values Pseudo-polynomial complexity Sustainable w. r. t. task periods

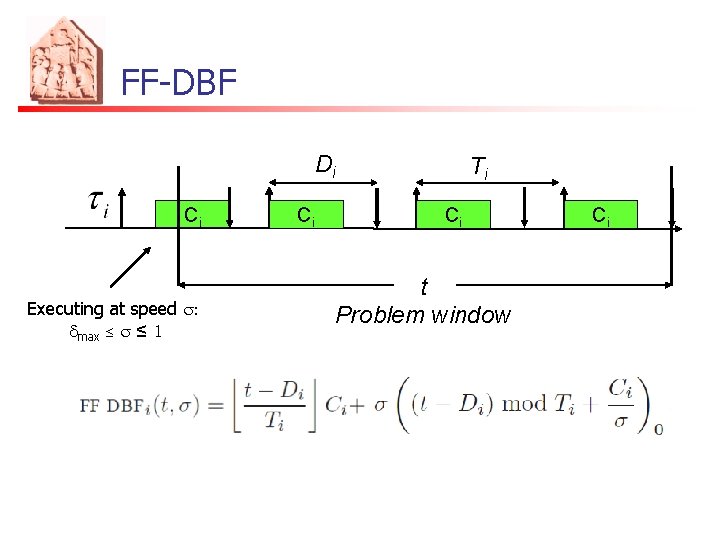

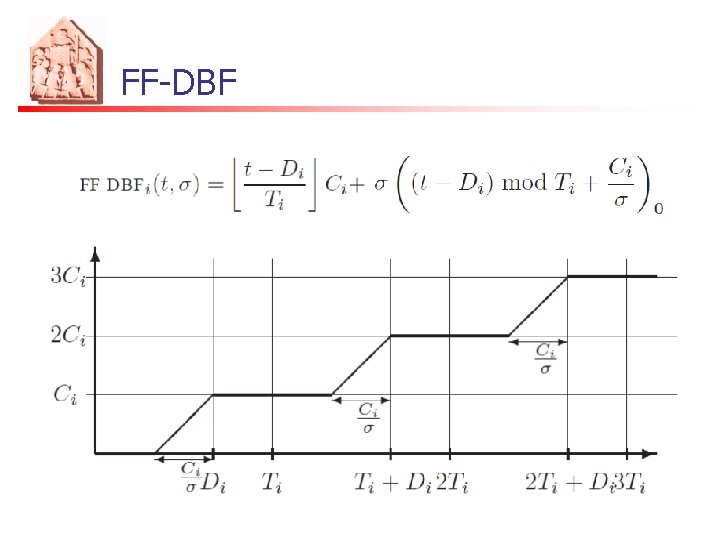

FF-DBF Di Ci Executing at speed s: dmax ≤ s ≤ 1 Ci Ti Ci t Problem window Ci

FF-DBF

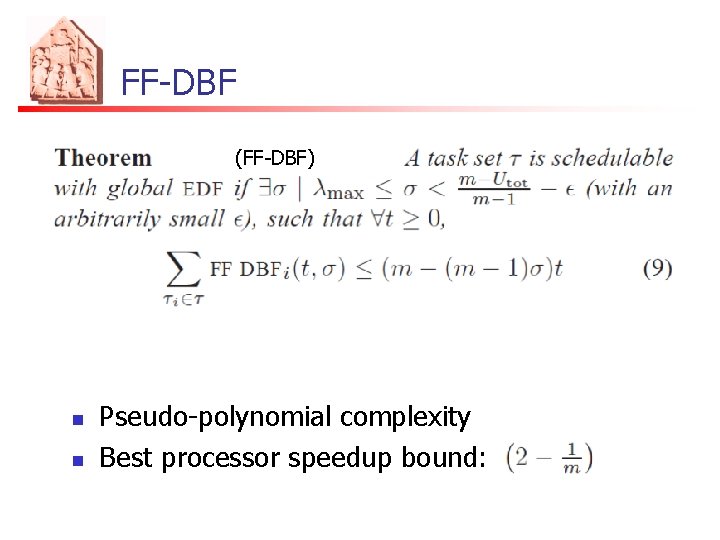

FF-DBF (FF-DBF) n n Pseudo-polynomial complexity Best processor speedup bound:

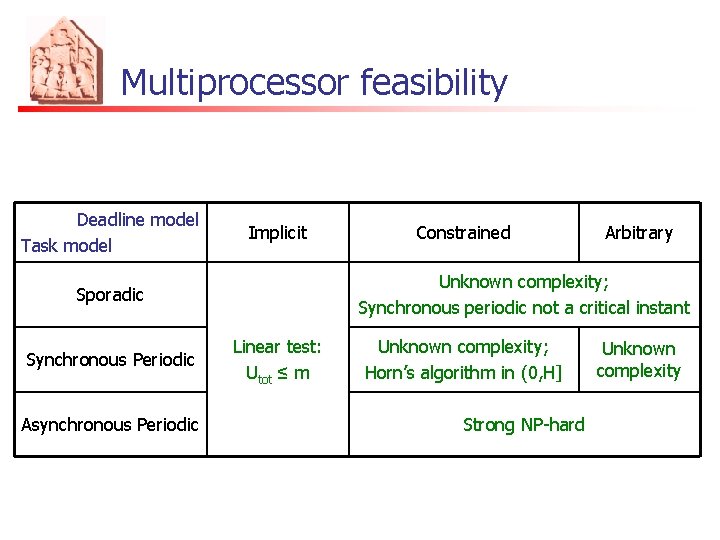

Multiprocessor feasibility Deadline model Task model Implicit Asynchronous Periodic Arbitrary Unknown complexity; Synchronous periodic not a critical instant Sporadic Synchronous Periodic Constrained Linear test: Utot ≤ m Unknown complexity; Horn’s algorithm in (0, H] Strong NP-hard Unknown complexity

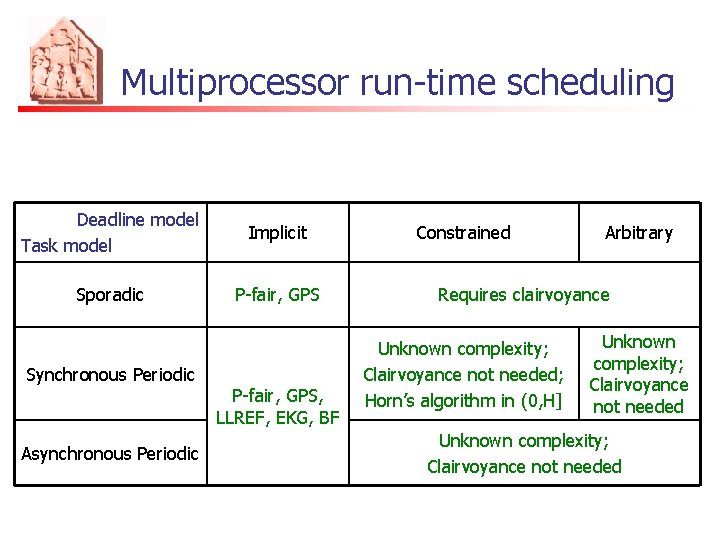

Multiprocessor run-time scheduling Deadline model Task model Implicit Sporadic P-fair, GPS Synchronous Periodic Asynchronous Periodic P-fair, GPS, LLREF, EKG, BF Constrained Arbitrary Requires clairvoyance Unknown complexity; Clairvoyance not needed; Horn’s algorithm in (0, H] Unknown complexity; Clairvoyance not needed

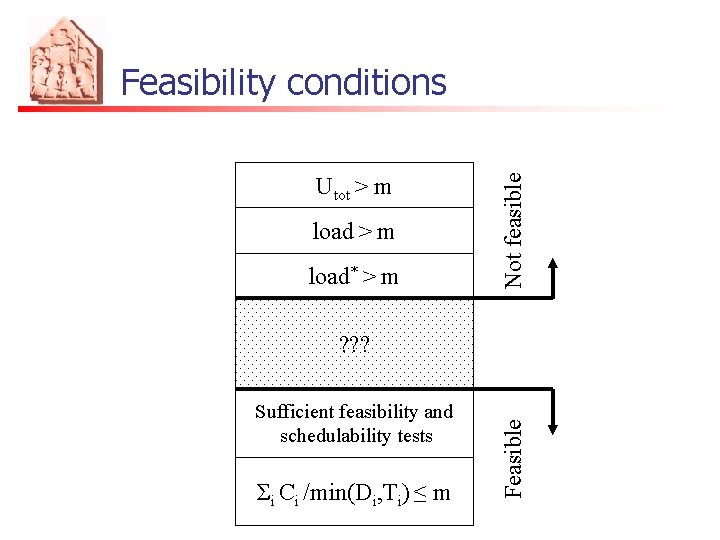

Utot > m load* > m Not feasible Feasibility conditions Sufficient feasibility and schedulability tests Σi Ci /min(Di, Ti) ≤ m Feasible ? ? ?

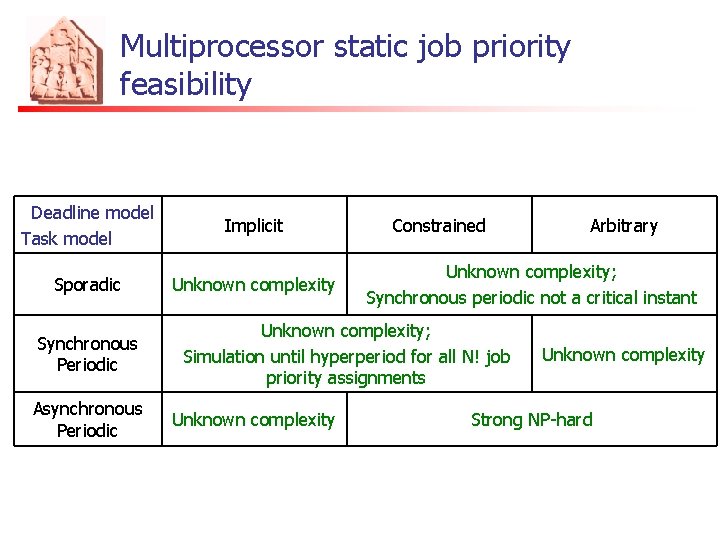

Multiprocessor static job priority feasibility Deadline model Task model Implicit Sporadic Unknown complexity Synchronous Periodic Asynchronous Periodic Constrained Unknown complexity; Synchronous periodic not a critical instant Unknown complexity; Simulation until hyperperiod for all N! job priority assignments Unknown complexity Arbitrary Unknown complexity Strong NP-hard

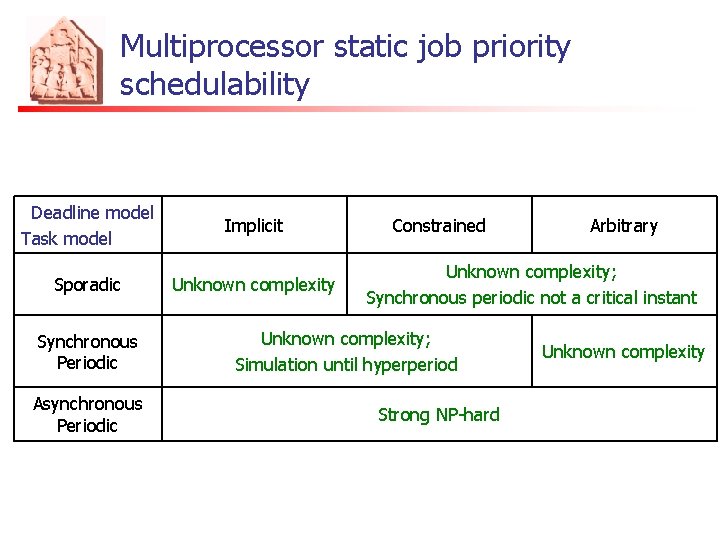

Multiprocessor static job priority schedulability Deadline model Task model Implicit Sporadic Unknown complexity Synchronous Periodic Asynchronous Periodic Constrained Arbitrary Unknown complexity; Synchronous periodic not a critical instant Unknown complexity; Simulation until hyperperiod Strong NP-hard Unknown complexity

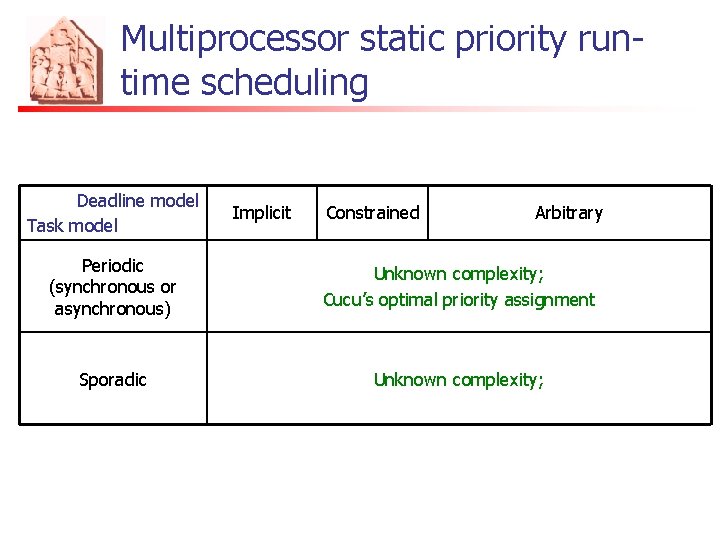

Multiprocessor static priority runtime scheduling Deadline model Task model Implicit Constrained Arbitrary Periodic (synchronous or asynchronous) Unknown complexity; Cucu’s optimal priority assignment Sporadic Unknown complexity;

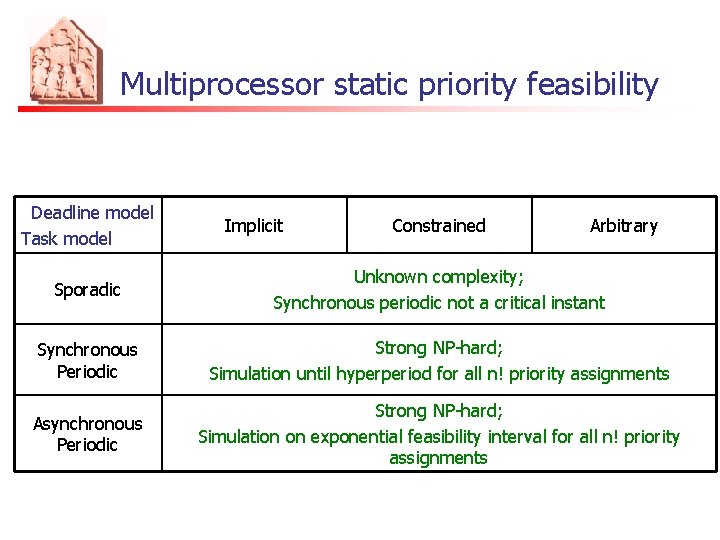

Multiprocessor static priority feasibility Deadline model Task model Implicit Constrained Arbitrary Sporadic Unknown complexity; Synchronous periodic not a critical instant Synchronous Periodic Strong NP-hard; Simulation until hyperperiod for all n! priority assignments Asynchronous Periodic Strong NP-hard; Simulation on exponential feasibility interval for all n! priority assignments

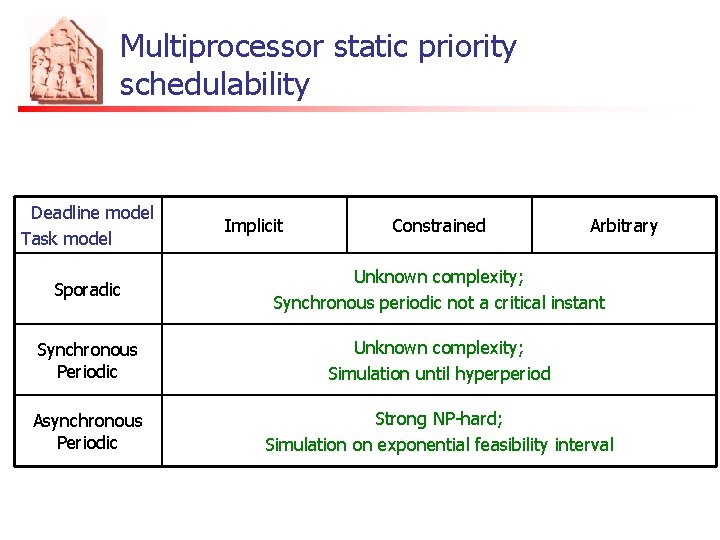

Multiprocessor static priority schedulability Deadline model Task model Implicit Constrained Arbitrary Sporadic Unknown complexity; Synchronous periodic not a critical instant Synchronous Periodic Unknown complexity; Simulation until hyperperiod Asynchronous Periodic Strong NP-hard; Simulation on exponential feasibility interval

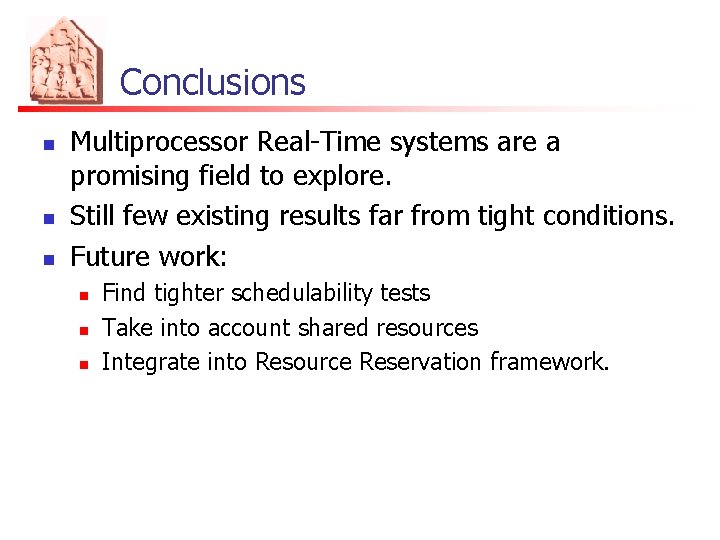

Conclusions n n n Multiprocessor Real-Time systems are a promising field to explore. Still few existing results far from tight conditions. Future work: n n n Find tighter schedulability tests Take into account shared resources Integrate into Resource Reservation framework.

Bibliography n n n n Sustainability: Sanjoy Baruah and Alan Burns. Sustainable scheduling analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE Real-time Systems Symposium, Rio de Janeiro, December 2006. Speedup: Cynthia A. Phillips, Cliff Stein, Eric Torng, and Joel Wein. Optimal timecritical scheduling via resource augmentation. In Proceedings of the Twenty. Ninth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, El Paso, Texas, 4{6 May 1997. BAR test: Sanjoy Baruah. Techniques for mutliprocessor global schedulability analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE Real-time Systems Symposium, Tucson, December 2007. FF-DBF test: Sanjoy Baruah, Vincenzo Bonifaci, Alberto Marchetti-Spaccamela, and Sebastian Stiller. Implementation of a speedup-optimal global EDF schedulability test. In Proceedings of the Euro. Micro Conference on Real-Time Systems, Dublin, Ireland, July 2009. RTA test: Marko Bertogna and Michele Cirinei. Response-time analysis for globally scheduled symmetric multiprocessor platforms. In 28 th IEEE Real-Time Systems Symposium (RTSS), Tucson, Arizona (USA), 2007. BCL: Marko Bertogna, Michele Cirinei, and Giuseppe Lipari. Schedulability analysis of global scheduling algorithms on multiprocessor platforms. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems, 20(4): 553{566, April 2009. GFB test: Joel Goossens, Shelby Funk, and Sanjoy Baruah. Priority-driven scheduling of periodic task systems on multiprocessors. Real Time Systems, 25(2{3): 187{205, 2001.

The end

- Slides: 122