RealTime Multitasking 5 1 Introduction Task Basics Task

Real-Time Multitasking 5. 1 Introduction Task Basics Task Control Error Status System Tasks ® 5 -2

What is Real-Time? l Real-time denotes the ability of a control system to keep up with the system being controlled. l A system is described as being deterministic if its response time is predictable. l The lag time between the occurrence of an event and the response to that event is called latency. l Deterministic response is the key to real-time performance. ® 5 -3

Requirements of a Real-time System l Ability to control many external components: – Independent components – Asynchronous components – Synchronous components l High speed execution: – Fast response – Low overhead l Deterministic operation: – A late answer is a wrong answer. ® 5 -4

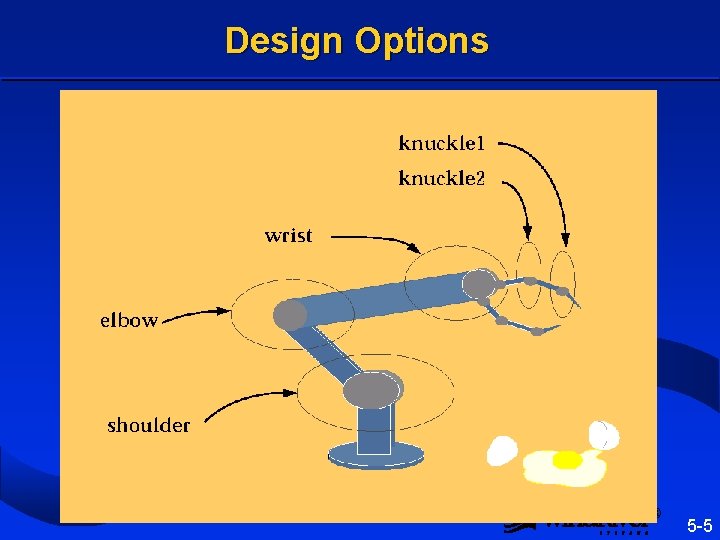

Design Options ® 5 -5

Unitasking Approach l One task controlling all the components in a loop. arm () { for (; ; ) { if (shoulder needs moving) move. Shoulder(); if (elbow needs moving) move. Elbow(); if (wrist needs moving) move. Wrist(); . . . } } ® 5 -6

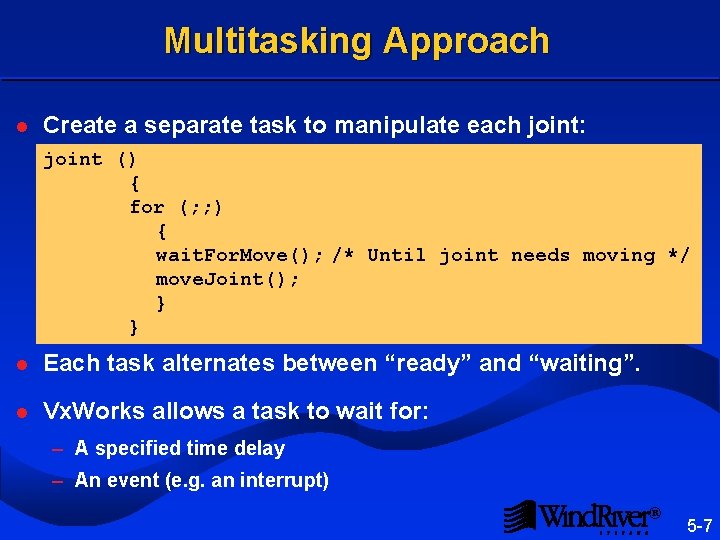

Multitasking Approach l Create a separate task to manipulate each joint: joint () { for (; ; ) { wait. For. Move(); /* Until joint needs moving */ move. Joint(); } } l Each task alternates between “ready” and “waiting”. l Vx. Works allows a task to wait for: – A specified time delay – An event (e. g. an interrupt) ® 5 -7

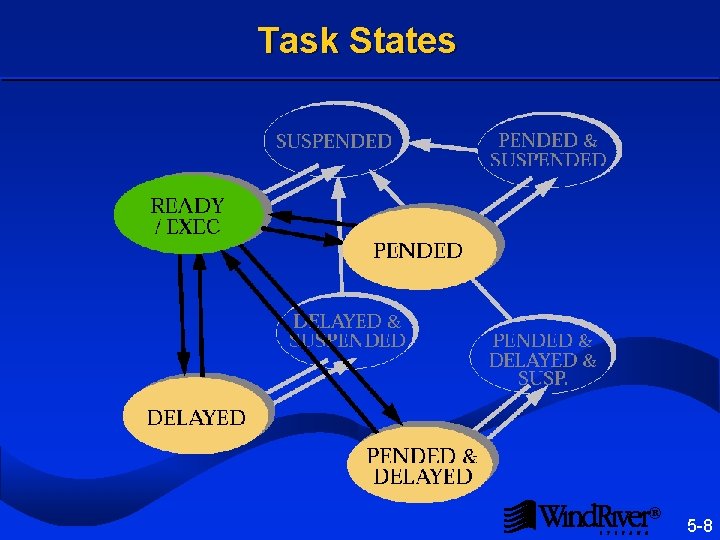

Task States ® 5 -8

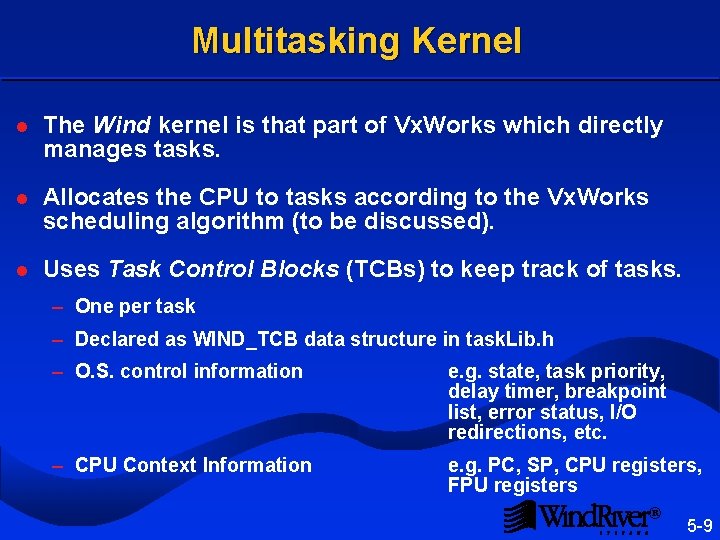

Multitasking Kernel l The Wind kernel is that part of Vx. Works which directly manages tasks. l Allocates the CPU to tasks according to the Vx. Works scheduling algorithm (to be discussed). l Uses Task Control Blocks (TCBs) to keep track of tasks. – One per task – Declared as WIND_TCB data structure in task. Lib. h – O. S. control information e. g. state, task priority, delay timer, breakpoint list, error status, I/O redirections, etc. – CPU Context Information e. g. PC, SP, CPU registers, FPU registers ® 5 -9

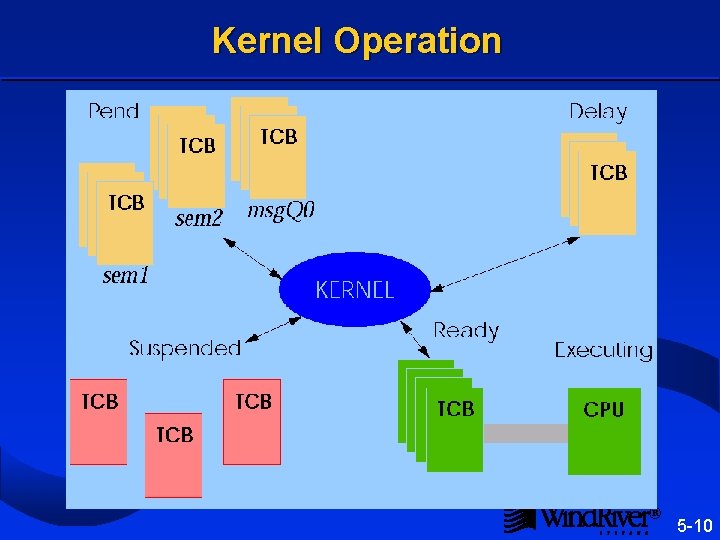

Kernel Operation ® 5 -10

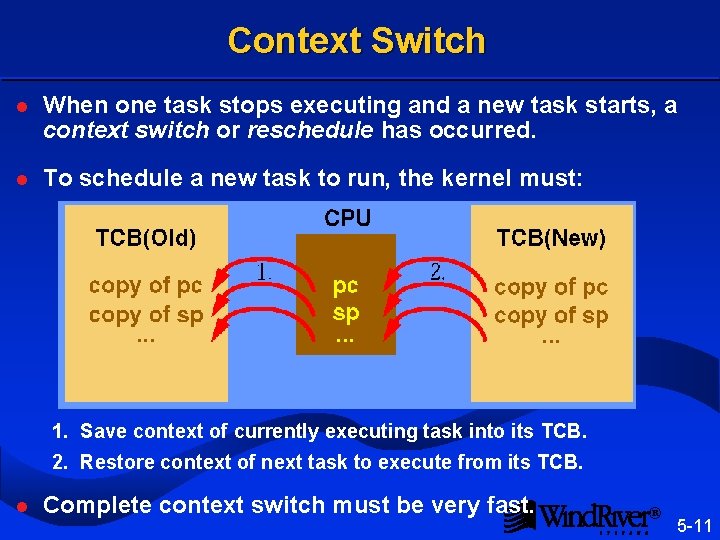

Context Switch l When one task stops executing and a new task starts, a context switch or reschedule has occurred. l To schedule a new task to run, the kernel must: 1. Save context of currently executing task into its TCB. 2. Restore context of next task to execute from its TCB. l Complete context switch must be very fast. ® 5 -11

Types of Context Switches l Synchronous context switches occur because the executing task – pends, delays, or suspends itself. – makes a higher priority task ready to run. – (less frequently) lowers its own priority, or exits. l Asynchronous context switches occur when an ISR: – makes a higher priority task ready to run. – (less frequently) suspends the current task or lowers its priority. l Synchronous context switches require saving fewer registers than asynchronous context switches, and so are faster. ® 5 -12

Priority Scheduling l Different application jobs may have different precedences, which should be observed when allocating the CPU. l Preemptive scheduling is based on task priorities chosen to reflect job precedence. l The highest priority task ready to run (not pended or delayed) is allocated the CPU. l Rescheduling can occur at any time as a result of: – Kernel calls – Interrupts (e. g. , system clock tick) l The context switch is not delayed until the next system clock tick. ® 5 -13

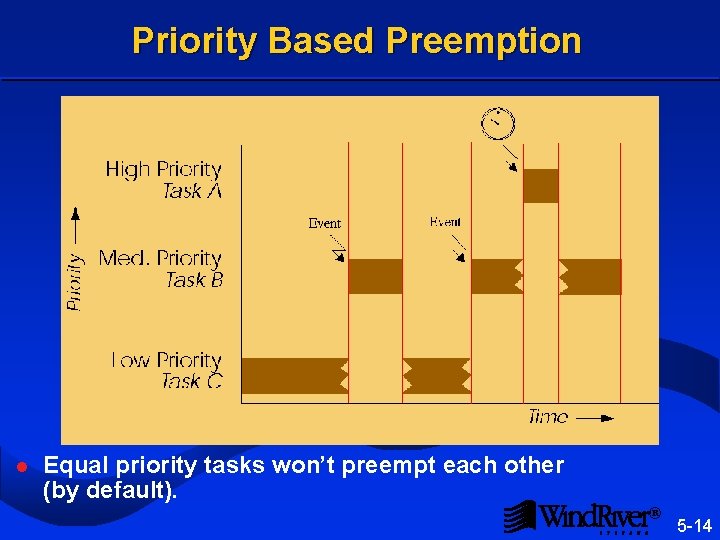

Priority Based Preemption l Equal priority tasks won’t preempt each other (by default). ® 5 -14

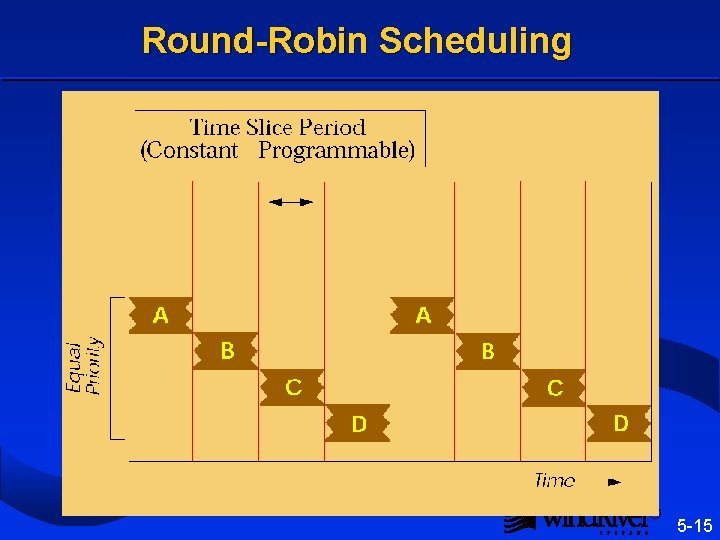

Round-Robin Scheduling ® 5 -15

Slicing Time l To allow equal priority tasks to preempt each other, time slicing must be turned on: kernel. Time. Slice(ticks) If ticks = 0, time slicing is turned off. l Priority scheduling always takes precedence. – Round-robin only applies to tasks of the same priority. l Priority-based rescheduling can happen any time. – Round-robin rescheduling can only happen every few clock ticks. ® 5 -16

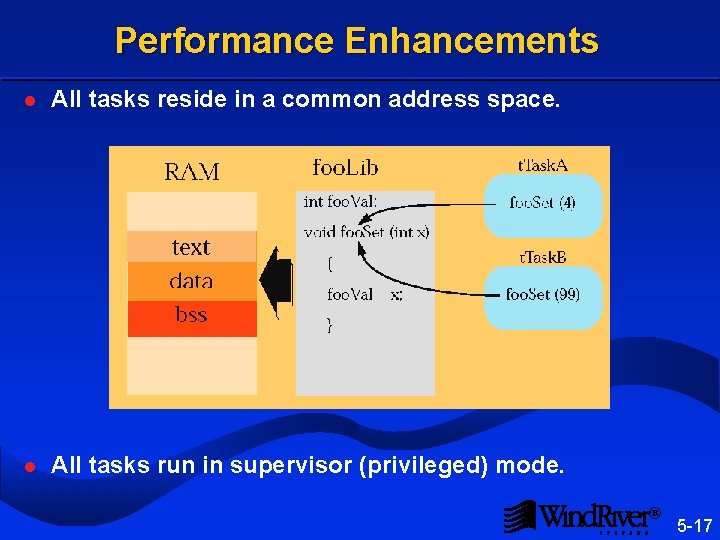

Performance Enhancements l All tasks reside in a common address space. l All tasks run in supervisor (privileged) mode. ® 5 -17

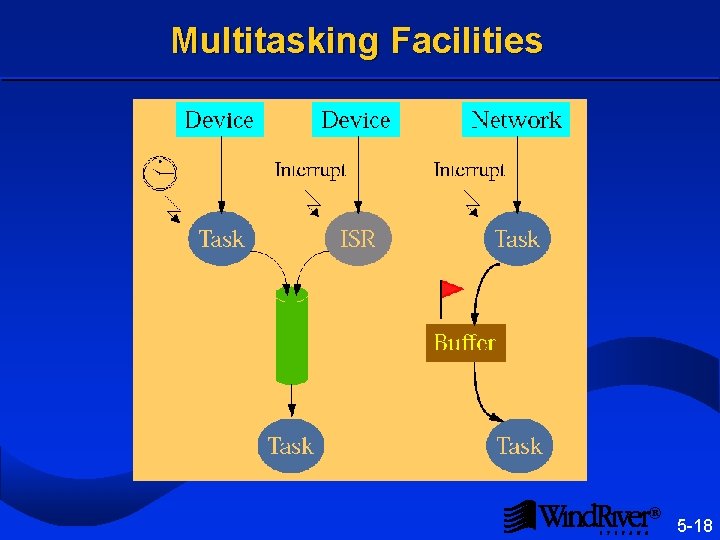

Multitasking Facilities ® 5 -18

How Vx. Works Operating System Meets Real-time Requirements l Able to control many external components – Multitasking allows solution to mirror the problem. – Independent functions are assigned to different tasks. – Intertask communication allows tasks to cooperate. l High speed execution – Tasks are light-weight, enabling fast context switch. – No “system call” overhead. l Deterministic operation – Preemptive priority scheduling assures response for high priority tasks. ® 5 -19

Real-Time Multitasking Introduction 5. 2 Task Basics Task Control Error Status System Tasks ® 5 -20

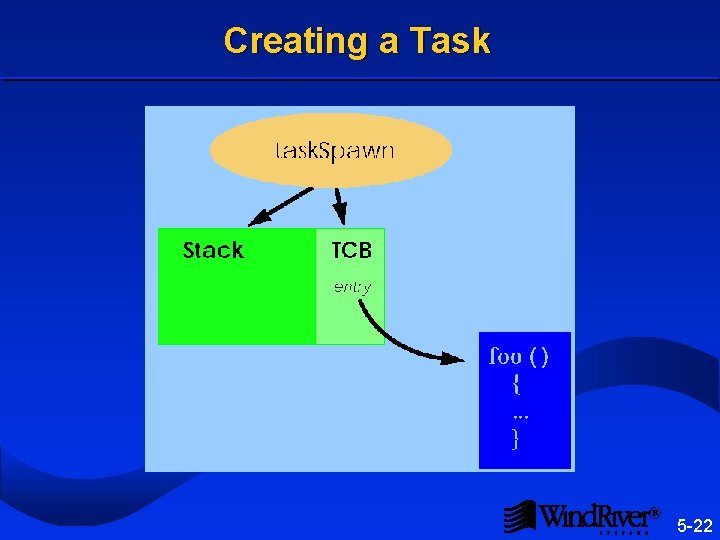

Overview l Low level routines to create and manipulate tasks are found in task. Lib. l A Vx. Works task consists of: – A stack (for local storage of automatic variables and parameters passed to routines). – A TCB (for OS control). l Do not confuse executable code with the task(s) which execute it: – Code is downloaded before tasks are spawned. – Several tasks can execute the same code (e. g. , printf( )). ® 5 -21

Creating a Task ® 5 -22

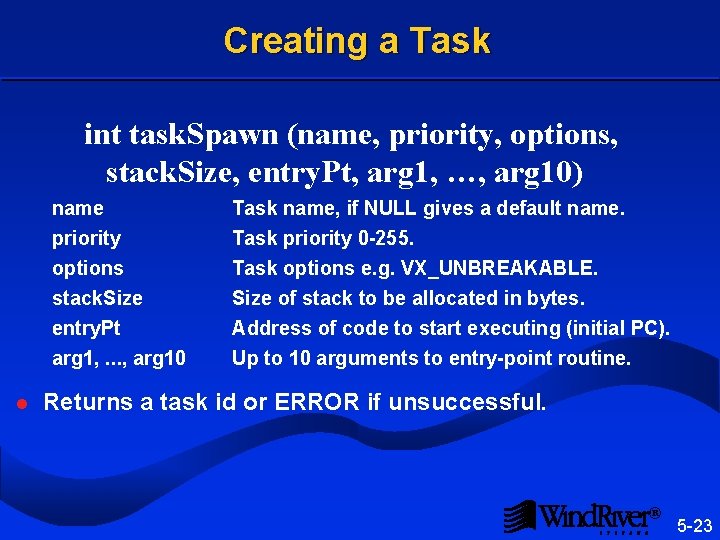

Creating a Task int task. Spawn (name, priority, options, stack. Size, entry. Pt, arg 1, …, arg 10) l name priority options Task name, if NULL gives a default name. Task priority 0 -255. Task options e. g. VX_UNBREAKABLE. stack. Size entry. Pt arg 1, . . . , arg 10 Size of stack to be allocated in bytes. Address of code to start executing (initial PC). Up to 10 arguments to entry-point routine. Returns a task id or ERROR if unsuccessful. ® 5 -23

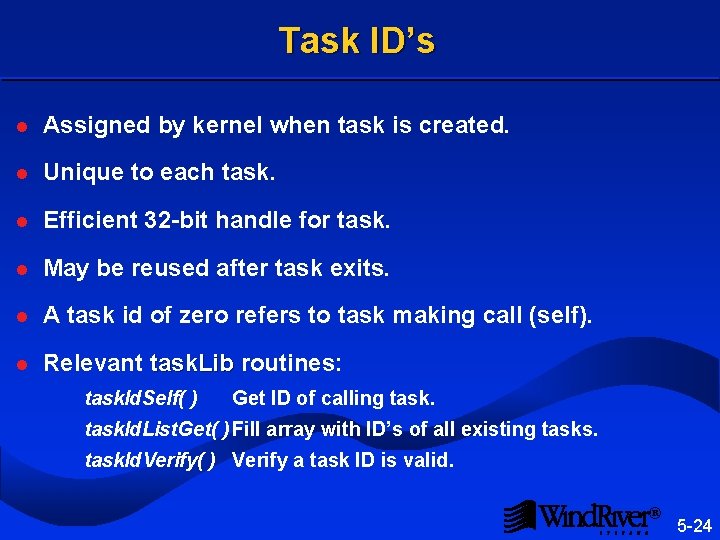

Task ID’s l Assigned by kernel when task is created. l Unique to each task. l Efficient 32 -bit handle for task. l May be reused after task exits. l A task id of zero refers to task making call (self). l Relevant task. Lib routines: task. Lib task. Id. Self( ) Get ID of calling task. Id. List. Get( ) Fill array with ID’s of all existing tasks. task. Id. Verify( ) Verify a task ID is valid. ® 5 -24

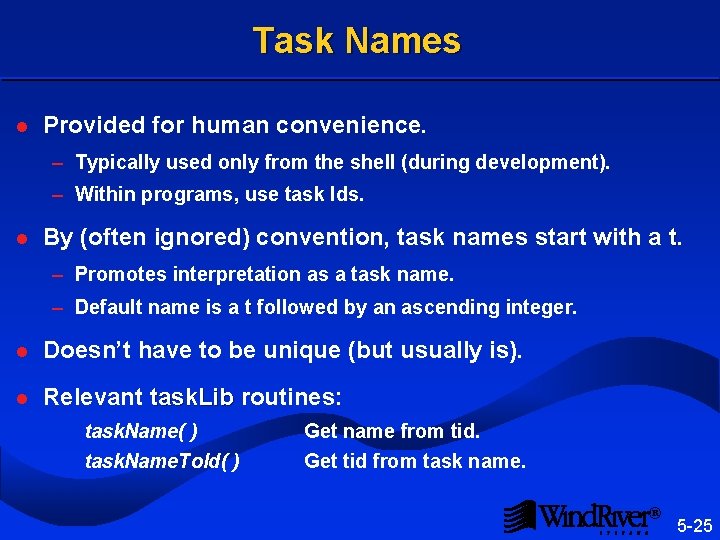

Task Names l Provided for human convenience. – Typically used only from the shell (during development). – Within programs, use task Ids. l By (often ignored) convention, task names start with a t. – Promotes interpretation as a task name. – Default name is a t followed by an ascending integer. l Doesn’t have to be unique (but usually is). l Relevant task. Lib routines: task. Lib task. Name( ) task. Name. To. Id( ) Get name from tid. Get tid from task name. ® 5 -25

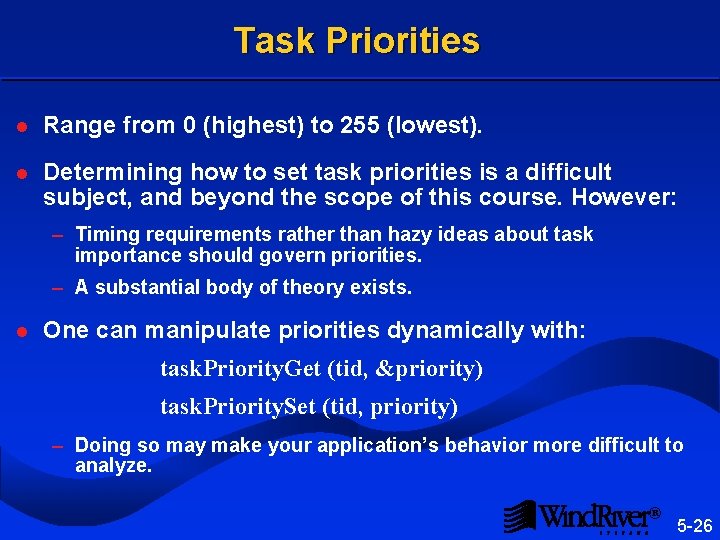

Task Priorities l Range from 0 (highest) to 255 (lowest). l Determining how to set task priorities is a difficult subject, and beyond the scope of this course. However: – Timing requirements rather than hazy ideas about task importance should govern priorities. – A substantial body of theory exists. l One can manipulate priorities dynamically with: task. Priority. Get (tid, &priority) task. Priority. Set (tid, priority) – Doing so may make your application’s behavior more difficult to analyze. ® 5 -26

Task Stacks l Allocated from system memory pool when task is created. l Fixed size after creation. l The kernel reserves some space from the stack, making the stack space actually available slightly less than the stack space requested. l Exceeding stack size (“stack crash”) causes unpredictable system behavior. ® 5 -27

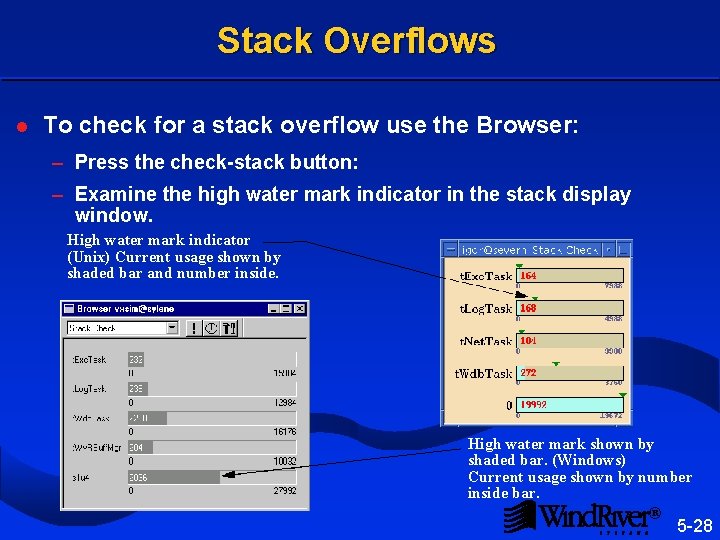

Stack Overflows l To check for a stack overflow use the Browser: – Press the check-stack button: – Examine the high water mark indicator in the stack display window. High water mark indicator (Unix) Current usage shown by shaded bar and number inside. High water mark shown by shaded bar. (Windows) Current usage shown by number inside bar. ® 5 -28

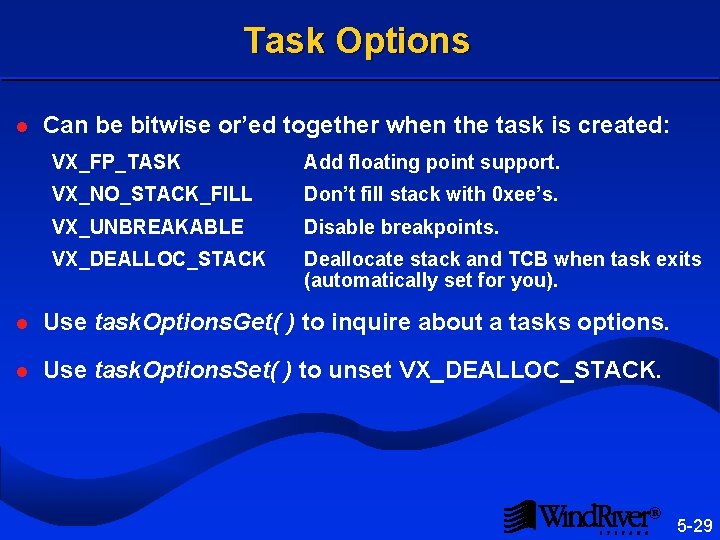

Task Options l Can be bitwise or’ed together when the task is created: VX_FP_TASK Add floating point support. VX_NO_STACK_FILL Don’t fill stack with 0 xee’s. VX_UNBREAKABLE Disable breakpoints. VX_DEALLOC_STACK Deallocate stack and TCB when task exits (automatically set for you). l Use task. Options. Get( ) to inquire about a tasks options. l Use task. Options. Set( ) to unset VX_DEALLOC_STACK. ® 5 -29

Task Creation l During time critical code, task creation can be unacceptably time consuming. l To reduce creation time, a task can be spawned with the VX_NO_STACK_FILL option bit set. l Alternatively, spawn a task at system start-up which blocks immediately, and waits to be made ready when needed. ® 5 -30

Task Deletion task. Delete (tid) l Deletes the specified task. l Deallocates the TCB and stack. exit(code) l Equivalent to a task. Delete( ) of self. l code parameter is stored in the TCB field exit. Code. l TCB may be examined for post-mortem debugging by – Unsetting the VX_DEALLOC_STACK option or, – Using a delete hook. ® 5 -31

Resource Reclamation l Contrary to the philosophy of sharing system resources among all tasks. l Can be an expensive process, which must be the application’s responsibility. l TCB and stack are the only resources automatically reclaimed. l Tasks are responsible for cleaning up after themselves. – Deallocating memory. – Releasing locks on shared resources. – Closing files which are open. – Deleting child tasks when parent task exits. ® 5 -32

Real-Time Multitasking Introduction Task Basics 5. 3 Task Control Error Status System Tasks ® 5 -33

Task Restart task. Restart (tid) l Task is terminated and respawned with original arguments and tid. l Usually used for error recovery. ® 5 -34

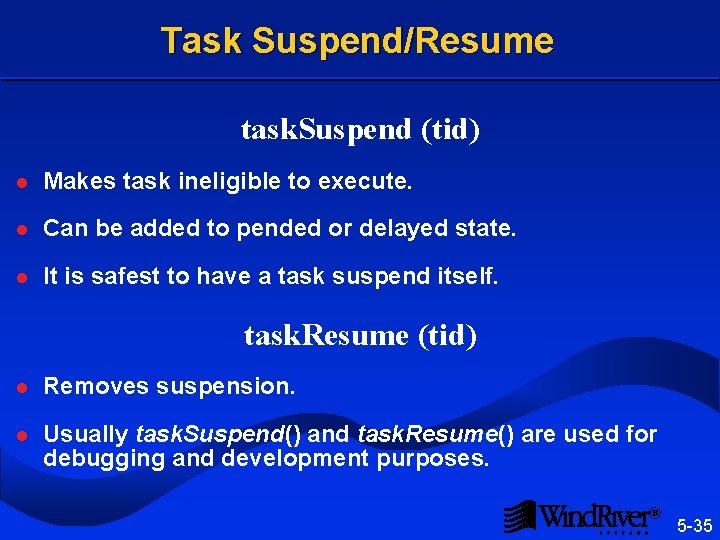

Task Suspend/Resume task. Suspend (tid) l Makes task ineligible to execute. l Can be added to pended or delayed state. l It is safest to have a task suspend itself. task. Resume (tid) l Removes suspension. l Usually task. Suspend() and task. Resume() are used for debugging and development purposes. ® 5 -35

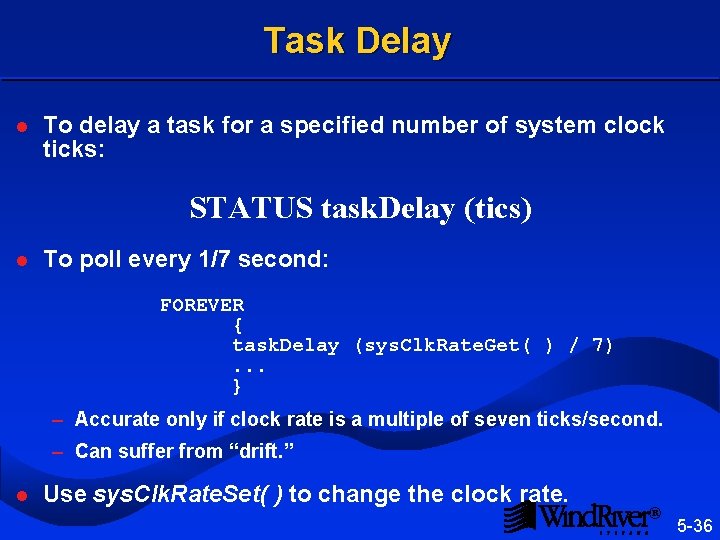

Task Delay l To delay a task for a specified number of system clock ticks: STATUS task. Delay (tics) l To poll every 1/7 second: FOREVER { task. Delay (sys. Clk. Rate. Get( ) / 7). . . } – Accurate only if clock rate is a multiple of seven ticks/second. – Can suffer from “drift. ” l Use sys. Clk. Rate. Set( ) to change the clock rate. ® 5 -36

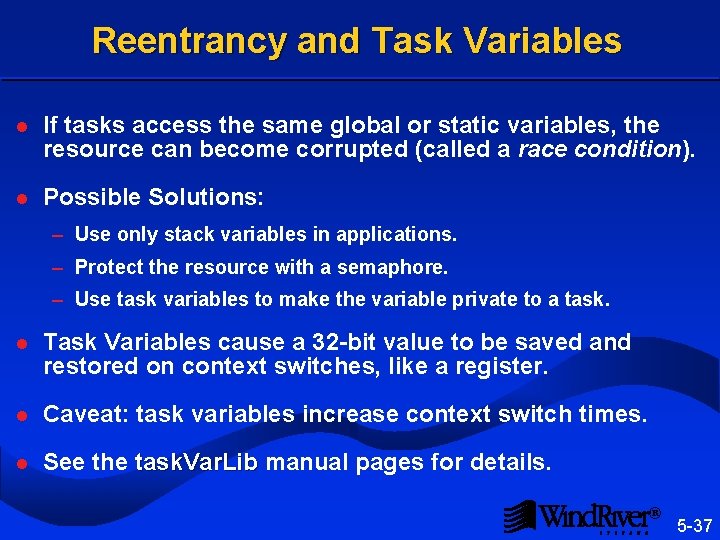

Reentrancy and Task Variables l If tasks access the same global or static variables, the resource can become corrupted (called a race condition). l Possible Solutions: – Use only stack variables in applications. – Protect the resource with a semaphore. – Use task variables to make the variable private to a task. l Task Variables cause a 32 -bit value to be saved and restored on context switches, like a register. l Caveat: task variables increase context switch times. l See the task. Var. Lib manual pages for details. task. Var. Lib ® 5 -37

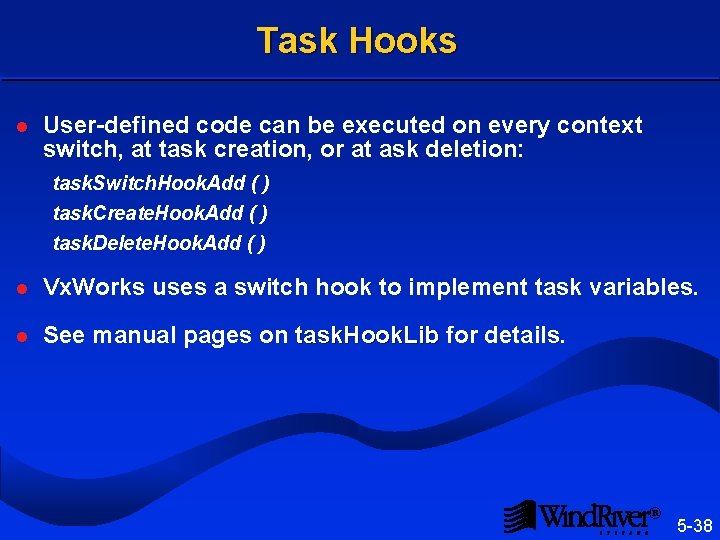

Task Hooks l User-defined code can be executed on every context switch, at task creation, or at ask deletion: task. Switch. Hook. Add ( ) task. Create. Hook. Add ( ) task. Delete. Hook. Add ( ) l Vx. Works uses a switch hook to implement task variables. l See manual pages on task. Hook. Lib for details. task. Hook. Lib ® 5 -38

Task Information ti (task. Name. Or. Id) l Like i( ), but also displays: – Stack information – Task options – CPU registers – FPU registers (if the VX_FP_TASK option bit is set). l Can also use show ( ): -> show (t. Net. Task, 1) ® 5 -39

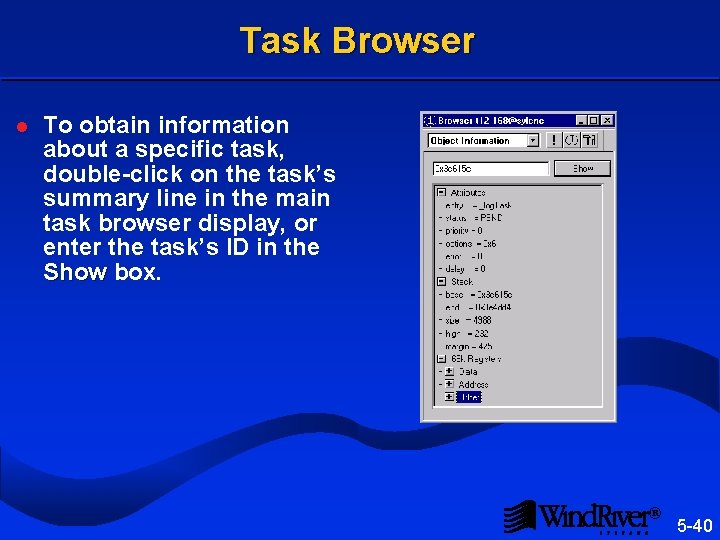

Task Browser l To obtain information about a specific task, double-click on the task’s summary line in the main task browser display, or enter the task’s ID in the Show box. Show ® 5 -40

What is POSIX? l Originally, an IEEE committee convened to create a standard interface to UNIX for: – Increased portability. – Convenience. l Vx. Works supports almost all of the 1003. 1 b POSIX Realtime Extensions. l The POSIX real-time extensions are based on implicit assumptions about the UNIX process model which do not always hold in Vx. Works. In Vx. Works, – Context switch times are very fast. – Text, data, and bss segments are stored in a common, global address space. ® 5 -41

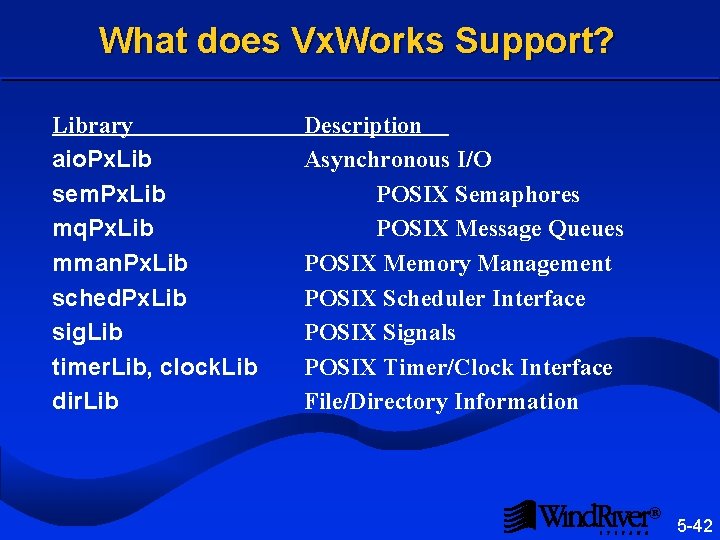

What does Vx. Works Support? Library aio. Px. Lib sem. Px. Lib mq. Px. Lib mman. Px. Lib sched. Px. Lib sig. Lib timer. Lib, clock. Lib dir. Lib Description Asynchronous I/O POSIX Semaphores POSIX Message Queues POSIX Memory Management POSIX Scheduler Interface POSIX Signals POSIX Timer/Clock Interface File/Directory Information ® 5 -42

Real-Time Multitasking Introduction Task Basics Task Control 5. 4 Error Status System Tasks ® 5 -43

Error Status l Global integer errno is used to propagate error information: – Low level routine detecting an error sets errno. – Calling routine can examine errno to discover why the routine failed. ® 5 -44

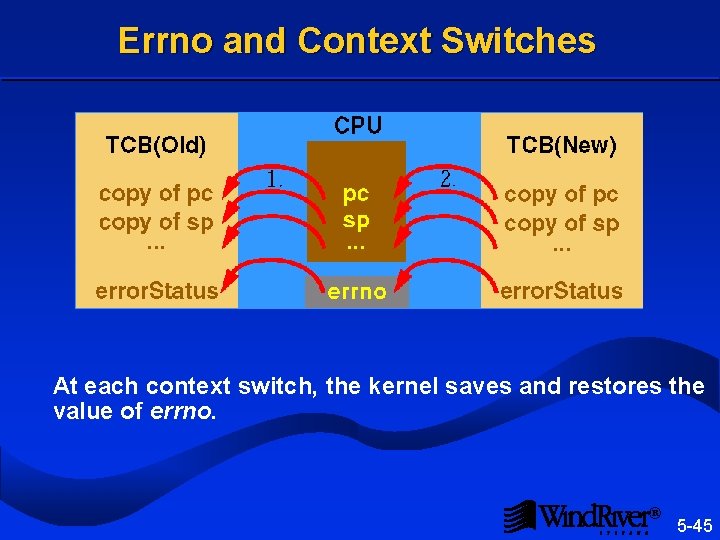

Errno and Context Switches At each context switch, the kernel saves and restores the value of errno. ® 5 -45

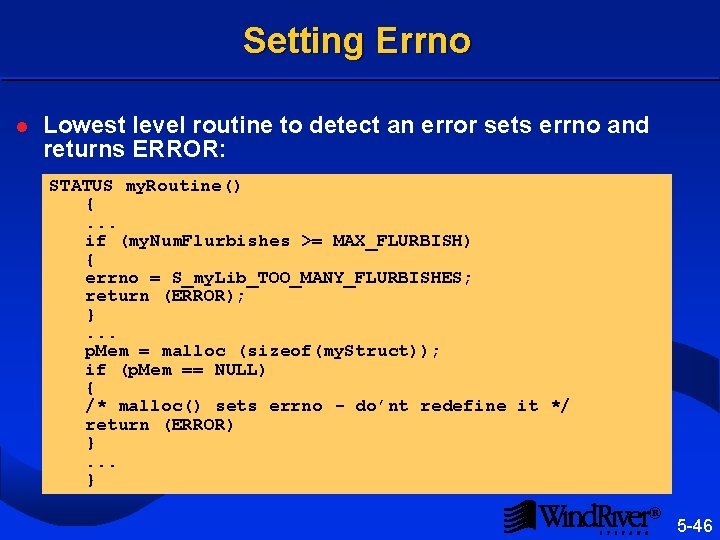

Setting Errno l Lowest level routine to detect an error sets errno and returns ERROR: STATUS my. Routine() {. . . if (my. Num. Flurbishes >= MAX_FLURBISH) { errno = S_my. Lib_TOO_MANY_FLURBISHES; return (ERROR); }. . . p. Mem = malloc (sizeof(my. Struct)); if (p. Mem == NULL) { /* malloc() sets errno - do’nt redefine it */ return (ERROR) }. . . } ® 5 -46

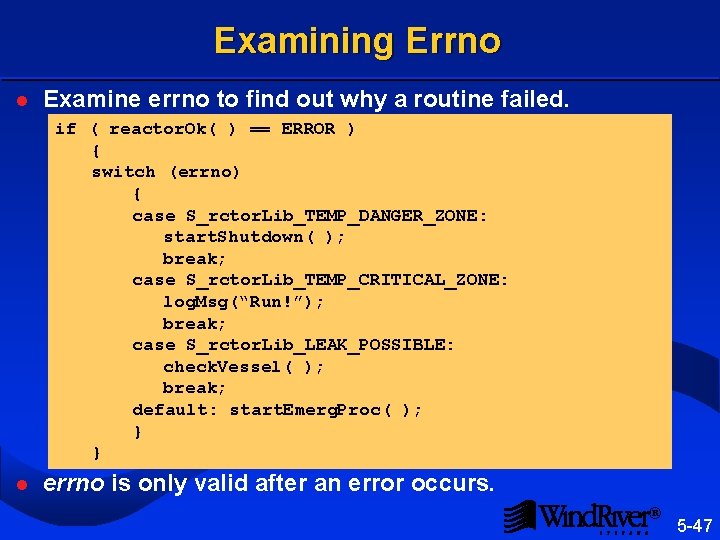

Examining Errno l Examine errno to find out why a routine failed. if ( reactor. Ok( ) == ERROR ) { switch (errno) { case S_rctor. Lib_TEMP_DANGER_ZONE: start. Shutdown( ); break; case S_rctor. Lib_TEMP_CRITICAL_ZONE: log. Msg(“Run!”); break; case S_rctor. Lib_LEAK_POSSIBLE: check. Vessel( ); break; default: start. Emerg. Proc( ); } } l errno is only valid after an error occurs. ® 5 -47

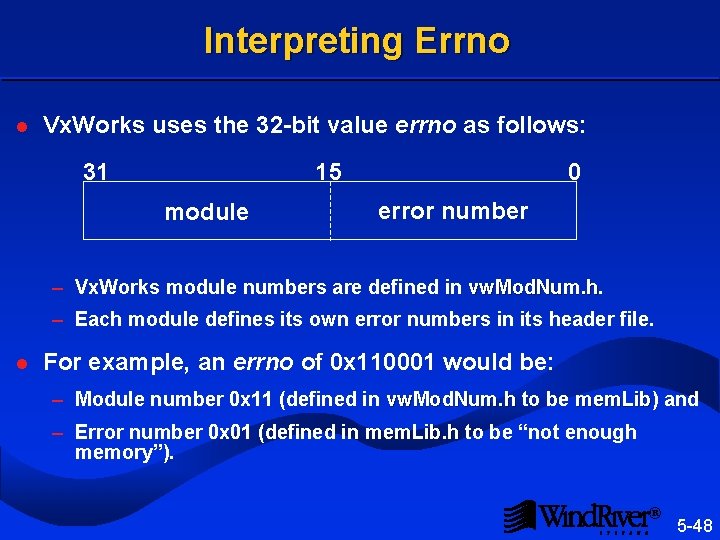

Interpreting Errno l Vx. Works uses the 32 -bit value errno as follows: 31 15 0 module error number – Vx. Works module numbers are defined in vw. Mod. Num. h. . h – Each module defines its own error numbers in its header file. l For example, an errno of 0 x 110001 would be: – Module number 0 x 11 (defined in vw. Mod. Num. h to be mem. Lib) and. h mem. Lib – Error number 0 x 01 (defined in mem. Lib. h to be “not enough . h memory”). ® 5 -48

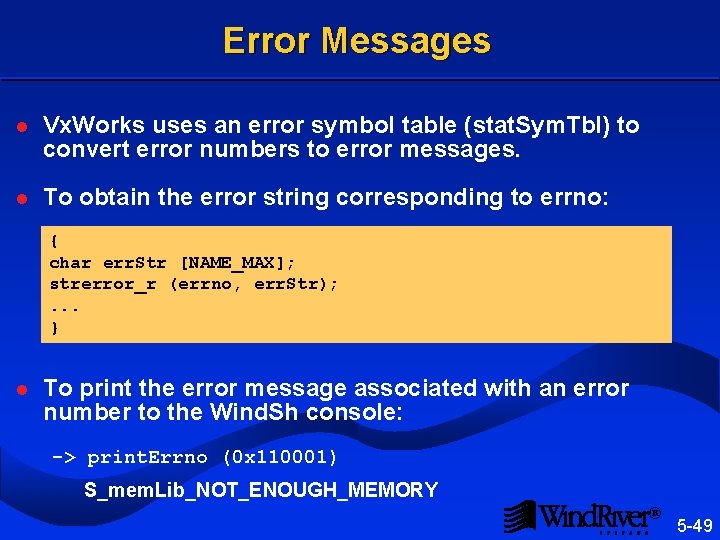

Error Messages l Vx. Works uses an error symbol table (stat. Sym. Tbl) to convert error numbers to error messages. l To obtain the error string corresponding to errno: { char err. Str [NAME_MAX]; strerror_r (errno, err. Str); . . . } l To print the error message associated with an error number to the Wind. Sh console: -> print. Errno (0 x 110001) S_mem. Lib_NOT_ENOUGH_MEMORY ® 5 -49

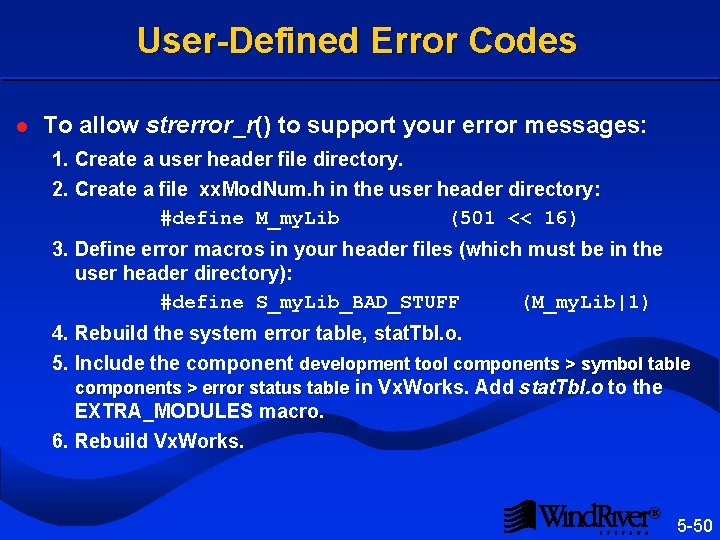

User-Defined Error Codes l To allow strerror_r() to support your error messages: 1. Create a user header file directory. 2. Create a file xx. Mod. Num. h in the user header directory: . h #define M_my. Lib (501 << 16) 3. Define error macros in your header files (which must be in the user header directory): #define S_my. Lib_BAD_STUFF (M_my. Lib|1) 4. Rebuild the system error table, stat. Tbl. o. . o 5. Include the component development tool components > symbol table components > error status table in Vx. Works. Add stat. Tbl. o to the EXTRA_MODULES macro. 6. Rebuild Vx. Works. ® 5 -50

Real-Time Multitasking Introduction Task Basics Task Control Error Status 5. 5 System Tasks ® 5 -51

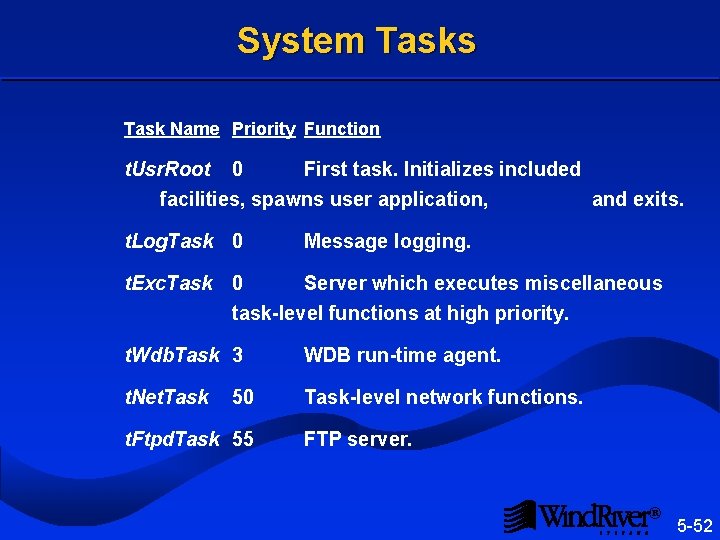

System Tasks Task Name Priority Function t. Usr. Root 0 First task. Initializes included facilities, spawns user application, and exits. t. Log. Task 0 t. Exc. Task Message logging. 0 Server which executes miscellaneous task-level functions at high priority. t. Wdb. Task 3 WDB run-time agent. t. Net. Task-level network functions. 50 t. Ftpd. Task 55 FTP server. ® 5 -52

Summary l Real-time multitasking requirements: – Preemptive priority-based scheduler – Low overhead l Task properties stored in task’s TCB. – OS control information (priority, stack size, options, state, . . . ). – Saved CPU context (PC, SP, CPU registers, . . . ). l task. Spawn( ) lets you specify intrinsic properties: – Priority – Stack size – Options ® 5 -53

Summary l Task manipulation routines in task. Lib: – task. Spawn/task. Delete – task. Delay – task. Suspend/task. Resume l Task information – ti/show – Task Browser l Additional task context: – errno – Task variables – Task hooks ® 5 -54

- Slides: 53